Abstract

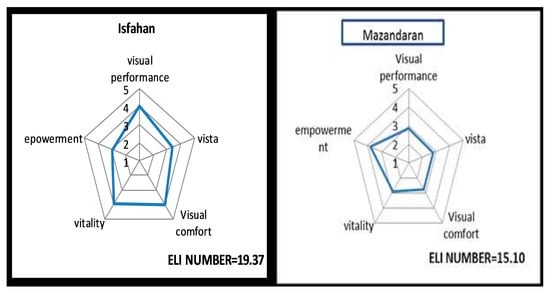

Background: Light is essential to many facets of human endeavors and is not only required for vision. The prevailing climate in the areas where workplaces are situated might moderate good lighting conditions, which are described as those that balance human needs. This study aimed to clarify how the Ergonomic Lighting Indicator should be used in workplaces while considering two distinct climates. Methods: Utilizing the Ergonomic Lighting Indicator questionnaire, the current investigation was conducted. A total of 140 volunteers who worked in indoor environments (70 in each climate condition) took part. Spider charts and descriptive analysis were employed. Results: In Isfahan City, practically every employee expressed complete satisfaction with the natural lighting’s quality. There was more visual comfort, according to workers in the province of Isfahan (p = 0.03). Except for the empowerment rating (p = 0.03; Mazandaran > Isfahan), Isfahan had greater scores on the Ergonomic Lighting Indicator than Mazandaran (visual performance: p = 0.02; vista: p = 0.01; vitality: p = 0.04). Conclusions: Based on this study, the use of Ergonomic Lighting Indicators to evaluate light quality is acceptable. In addition, this instrument can be applied in a variety of nations with diverse climates.

1. Introduction

Light is characterized as a part of the electromagnetic spectrum [1,2,3] and has numerous design, economic, and environmental applications [4]. In many of these applications, light plays a crucial role in various aspects of human activity [5]. Therefore, it can be concluded that, while light is essential for vision, its significance goes beyond just enabling sight [6]. Due to its important role, lighting has recently gained attention from both health specialists and designers [5,7].

The use of artificial lighting will continue to grow globally in the absence of natural light [8]. The visual and non-visual effects of artificial lighting have been supported by various studies [9,10]. Light has measurable physiological and psychological consequences for people, ranging from productivity to the wake–sleep cycle [11].

Recent investigations have indicated that, when people are exposed to light, this has non-visual impacts [12,13]. These non-visual effects can arise from the quality of the light source and can be categorized into high- and low-quality types [14]. Good lighting conditions are evaluated from both technical and emotional perspectives and are defined as those that balance human needs with energy efficiency, financial and environmental considerations, and architectural design requirements [4].

Along with individual differences, user groups may have different perceptions of the same light source [14,15]. So, quality can be discussed as a “human-centered” and “subjective” issue since it depends on self-report, where individuals express their own opinions [14,16]. Additionally, the perceived attributes include visual comfort and safety [17,18]. The quality of workplace lighting is one of the key factors among the significant features determining workers’ health and productivity [19,20,21]. The Ergonomic Lighting Indicator, along with other subjective indices, can specify some important aspects of light quality that could be perceived by employees [22]. This tool considers lighting requirements, as mentioned in the EN 12464 standard, “Lighting of workplaces” [23]. This measure presents five main criteria regarding the most important facets in lighting to illustrate the overall quality of a lighting system: visual performance, vista (view of a scene), visual comfort, vitality, and empowerment (to influence the lighting) [24].

Exposure to indoor workplaces’ lighting can be moderated by the prevailing climate, which impacts non-visual effects. Thus, it is crucial to consider the climate situation in which the indoor lighting is tested [11]. By selecting two cities with two different climate conditions (mostly sunny vs. mostly cloudy), in short, this study aimed to shed light on the application of the Ergonomic Lighting Indicator in workplaces by considering two different climate conditions. The ELI is selected because it is an important tool which integrates multiple ergonomically relevant dimensions of lighting into a validated framework that is referenced in international lighting standards, enabling comprehensive and reliable assessment of indoor environments.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Light and Human Body Response

In 2022, an article [1] reviewed the response of the human body to light and its different characteristics. They see light as the primary cue for the phase-shifting of the human circadian system, acting through intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) that project onto the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN), the brain’s master clock. This photic input regulates not only circadian timing but also acute physiological functions such as melatonin suppression, alertness, and neuroendocrine activity. They mentioned that the biological response to light is influenced by several physical characteristics of light: intensity, spectral composition, timing, and duration. Short-wavelength light (around 480 nm), to which melanopsin is most sensitive, is particularly potent in eliciting circadian and neuroendocrine responses. For example, lower levels of short-wavelength light can produce comparable effects to higher levels of other wavelengths in suppressing melatonin and shifting circadian rhythms. The magnitude and direction of these effects depend on the timing of exposure, with early-night light delaying the circadian phase and late-night light advancing it. The authors endorse the use of the melanopic Equivalent Daylight Illuminance (ED65v,mel), a metric standardized by the CIE (S 026/E:2018), as the preferred measure of the biological potency of light. This measure accounts for spectral sensitivity specific to melanopsin and offers a more accurate means to evaluate and design lighting for health outcomes than traditional photopic lux. The paper concludes that integrative lighting strategies—employing high melanopic potency light during the day and low potency light at night—represent a promising and immediately actionable approach to support human health and well-being.

In another review article [25], Peter Robert Boyce believes that light can impact human health via the visual and non-visual systems. He declared that light can influence health positively or negatively by impacting the visual system (e.g., eyestrain, headaches, falls) and the circadian system (via, ipRGCs, responsive to ~480 nm light). Disruption of the circadian rhythm by exposure to light at biologically inappropriate times can adversely affect sleep, alertness, and hormonal balance, and even risk chronic disease. The magnitude of these effects varies depending on light intensity, spectral composition, timing, and individual factors such as age or medical status.

Kevin Houser et al. discussed the “Human-centric lighting” concept in a recent article [26]. Human-centric lighting entails a dual focus on both visual and non-visual responses to light, as emphasized by the concept of “phase integrative lighting” introduced by the CIE. While some commercial claims may exaggerate its potential, and despite gaps in scientific understanding, it is feasible to design lighting systems that harmonize visual comfort with biological and psychological needs. They declared that a key principle is the importance of timing in light exposure: high-biological-potency light primarily determined by intensity, spectrum, and gaze direction is beneficial in the morning or during the day to stabilize the circadian rhythm. Conversely, exposure to biologically potent light in the evening or at night should be minimized to prevent circadian disruption, especially in individuals with typical day–night schedules (e.g., shift workers). They declared that, although no universal metric exists to quantify biological potency, models based on photoreceptor responses and melanopsin suppression are emerging. The authors advocated for simple, actionable design principles despite the complexity of the science, summarized effectively as “bright days and dark nights”. It means that daylight-oriented architectural design must be encouraged to support health outcomes.

2.2. Ergonomic Lighting and Subjective Tools for Assessing Light Quality

Typically, when discussing the ergonomic assessment of lighting, concepts such as visual fatigue and visual ergonomics are inadvertently brought into the conversation. A review of previous studies has introduced a variety of tools developed for these concepts, among which only the ELI is studied in the present study. However, the other tools, although more commonly used, still remain noteworthy.

The Office Lighting Survey (OLS) is a questionnaire-based tool developed by Eklund and Boyce in 1996 to assess occupant satisfaction with office lighting [27]. It consists of 10 items presented in an agree–disagree format. The survey addresses various aspects of lighting quality, including visual comfort, glare, brightness, reflections, light distribution, flicker, color characteristics, and overall satisfaction. A modified version of the OLS has also been employed in other studies [28].

The Lighting Conditions Survey (LCS), developed in 1999, is a 37-item questionnaire designed to assess long-term satisfaction with lighting conditions and lighting quality in real-world workplace settings [29]. In addition to lighting-specific factors, the survey also captures user perceptions of broader environmental features such as office layout and spatial orientation. The LCS includes items related to both artificial and natural lighting, window access, brightness, reflections, light distribution, task lighting, color characteristics, external view, and overall satisfaction. However, a small number of specific lighting features—such as flicker—are not explicitly addressed, which may limit the survey’s comprehensiveness in certain ergonomic evaluations.

The NRC Canada Lighting Quality Scale [30], developed by Veitch and Newsham in 2000, is a 10-item questionnaire that evaluates office lighting through two distinct subscales—lighting quality and glare—each comprising multiple items. Participants rate statements on Likert-type agree–disagree scales, reflecting their perceptions of various aspects of ambient and task illumination. In addition to these subcomponents, the instrument includes items assessing overall satisfaction with the lighting environment and its perceived impact on work performance.

The Perceived Outdoor Lighting Quality (POLQ) scale, developed by M. Johansson and colleagues in 2014, is an observer-based assessment tool designed to evaluate pedestrians’ perceptions of outdoor lighting environments [14]. The scale identifies two key dimensions: perceived strength quality (PSQ) and perceived comfort quality (PCQ), both of which effectively differentiate between light sources based on characteristics such as illuminance level, color temperature, and color rendering. By capturing the subjective evaluations of lighting, the POLQ provides valuable insights into how outdoor lighting is experienced by pedestrians. It is proposed as a complementary tool for informing the design of sustainable and user-centered urban lighting systems.

2.3. How ELI Can Support the Occupants

Integrative lighting (IL) research emphasizes its influence on both visual and non-visual processes, yet methods for assessing IL in real-world settings remain limited. A Delphi study with 32 experts identified key descriptors from the ELI, including visual performance, vista, visual comfort, vitality, and control, and reached a consensus when at least 75% rated them as important. Indicators were defined as simple, valid, reliable, and non-intrusive, grouped into visual/photometric and temporal/human factor categories. Using a multi-criteria decision-making approach, the study also proposed context-specific weightings, offering a structured basis for the comprehensive evaluation and certification of indoor environments [31].

Balocco et al. [32] investigated daylight optimization in an existing primary school through human-centered design and simulation-based retrofitting strategies. Two alternative lighting proposals, integrating natural daylight with LED systems, were developed and assessed under precautionary climatic conditions. To evaluate their effectiveness, the study applied both technical and ergonomic indicators, including the Lighting Energy Numeric Indicator (LENI) and the Ergonomic Lighting Indicator [1]. The results showed that, while both solutions improved luminous comfort compared to the existing state, the LED1 system achieved a higher ELI score (18 vs. 12), particularly enhancing the vitality and visual performance dimensions. This application demonstrates the operational use of ELI as a comparative tool for assessing the ergonomic quality of alternative lighting designs.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Areas

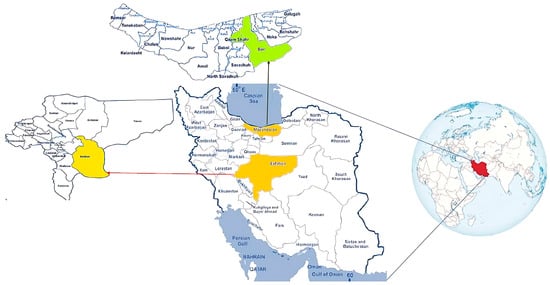

The present study was conducted to assess the lighting quality of indoor workplaces in one city of Mazandaran Province and one city in Isfahan Province, both located in the of Islamic Republic of Iran. Mazandaran is a northern province of Iran, located at approximately 36.2262° N latitude and 52.5319° E longitude. The city of Isfahan is in the heart of Iran, between the northern latitude of 32.6546° and the eastern longitude of 51.6680°. Figure 1 demonstrates the location of these provinces in Iran. The first province has a predominantly cloudy climate throughout the year, whereas the second province is characterized by mostly sunny conditions.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of Mazandaran and Isfahan provinces in Iran.

One place in each province was selected (two workplaces in total). Therefore, we can conclude that the effect of spatial change within each province has been eliminated. Both workplaces were comparatively comparable in terms of window location and light receiving direction.

Both workplaces had similar conditions in terms of window design. Sunlight entered the workspaces from the corners and near the ceiling, reaching the workstations from above. However, as previously mentioned, Isfahan Province receives significantly more natural light than the second province due to differences in their climates. In Mazandaran, because of the cloudy weather, artificial lights were on above the workstations during most of the day, while in Isfahan Province, artificial light was not used much because of the abundance of sunlight. In Mazandaran, all artificial lights used had similar characteristics in terms of light intensity, color temperature, and installation relative to the workstations.

3.2. Participants

One hundred and forty volunteer workers participated—including 70 workers in each province—who spent all their working hours at indoor workplaces. All of them were literate but did not have a university degree. All attendees were male as well due to the nature of the occupation. Their average age was 29 years. Differences in the amounts of daily natural light received were considered an indicator of the climate effect in this study.

3.3. Ergonomic Lighting INDICATOR Questionnaire

Before using the ELI questionnaire, its English version was translated into Persian, the participants’ native language (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.81). The questionnaire contains five subscales, named A to E, each of which includes some questions. Part A includes seven questions about visual performance while part B asks six questions about the quality of vista. Parts C and D, each with six questions, evaluate visual comfort and vitality at the indoor workplace, respectively. Part E, with six questions, focuses on the workers’ empowerment. Each question has a 5-point Likert, ranging from “absolutely right” to “not at all”. SPSS software (Version 19) was utilized to report descriptive statistical analysis. Summing up the mean value of the five parts, the total values were transferred to the corresponding points in the spider chart to obtain the ELI value for each participant. To gather subjective opinions from employees regarding the usage of artificial light or daylight or visual comfort, we employed Likert scales that were specifically designed for this study (ranging from 1 to 10).

4. Results

Natural sunlight levels varied between the two areas because of the humid environment of Mazandaran Province and the close proximity of Isfahan Province to Iran’s central desert. Field observations performed by health experts during the study period indicated that Isfahan City experienced mostly sunny weather, while Mazandaran City had predominantly cloudy to partly cloudy conditions. Table 1 compares employees’ preferences in the two provinces regarding the use of natural versus artificial lighting in their workplaces. Nearly all workers in Isfahan City expressed full satisfaction with the quality of the natural light available at their workstations.

Table 1.

Preference of the employees in two provinces for the use of natural or artificial sources of light.

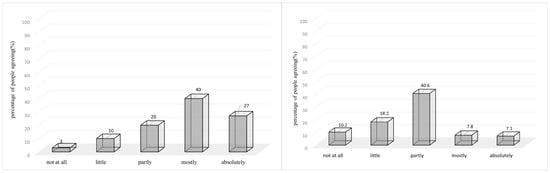

Figure 2 illustrates the satisfaction of the participants from Mazandaran and Isfahan Provinces with the visual comfort of their workplaces.

Figure 2.

Satisfaction of the participants from Mazandaran and Isfahan Provinces with visual comfort of their workplaces.

Table 2 indicated the mean, minimum, and maximum score given by the workers in Isfahan and Mazandaran Cities to the components of the ELI questionnaire.

Table 2.

Mean, minimum, and maximum values given by the workers to the components of the ELI questionnaire.

By summing up the mean values of each sub-criterion—including visual performance, vista, empowerment, visual comfort, and vitality—the ELI value was obtained. Based on this, the spider chart of each province was plotted, as shown in Figure 3. As the results show, the ELI score is higher in Isfahan, which means that employees in this city reported a better ergonomic status of their workplace lighting.

Figure 3.

ELI values for the lighting of workplaces in Mazandaran and Isfahan Provinces.

5. Discussion

The aim of this study was to apply the Ergonomic Lighting Indicator [1] in two different workplaces with varying climate conditions. According to the findings, workers in Isfahan City (as a representative of a sunny climate) preferred to use natural daylight over artificial lighting in their workplace. However, workers in Mazandaran Province (as a representative of a cloudy climate) expressed a different preference. One likely explanation for this difference could be the longer daylight hours in Isfahan.

According to the findings, employees in Isfahan thought that the adequate indoor illumination was provided by the extended daytime hours and enough sunshine that penetrated deeply into the interior spaces through numerous windows. Therefore, they felt no need for additional artificial lighting, while the opposite condition was observed in Mazandaran Province. The predominantly cloudy or partly cloudy weather throughout the year often fails to deliver enough daylight to illuminate interior spaces, leading workers to prefer electric lighting. A study by Despenic et al. [33] also demonstrated that the amount of available daylight can significantly influence the choice of artificial lighting. This suggests that, because Mazandaran City lacks adequate daylight on most days of the year, its employees choose artificial light. Some other studies have also reported workers’ preference for daylight-based workplaces [34,35].

Other results indicated that, in Isfahan, with almost sunny days in a year, workers declared more visual comfort than Mazandaran workers. This means the climate can play a mediating role in this way [36]. The importance of daylight in terms of visual comfort is of particular concern [37]. Another study found that the visual comfort of artificial and natural light differed significantly [35]. In line with the results, Shen et al. showed that the daylight system outperforms all other strategies in terms of visual comfort [38]. Although, despite our results, AbdulFasi et al. concluded that, in hot climates, increasing daylight provision cannot increase office users’ visual comfort [39]. So, providing an artificial light with similar quality to natural daylight is a good choice for light designers and employers.

The visual performance of workers is another parameter which was assessed in the Ergonomic Lighting Indicator. As the results stated, workers in Isfahan had a greater visual performance than those in Mazandaran. It can be concluded that daylight is much more likely to maximize visual performance than most types of electric lighting; thus, it is due to the characteristics of natural light that tend to be delivered by a broad spectrum and ensures good color rendering. Shishegar et al. stated that natural light can enhance the visual performance of workers and students [40]. Aries et al. and Knoop et al. affirmed the results of the current study and claimed that sunshine generally improves human vision more than electric lighting, allowing for higher visual performance [41,42]. So, in the case that workers need to perform a task/job which needs visual acuity, providing a good amount of natural light and then completing it with the required amount of artificial light is suggested.

Vista, or view of scene, is the next parameter that was assessed in the Ergonomic Lighting Indicator. This scale consists of architectural conception, user’s expectation, orientation, perception hierarchy, exterior perception, material, and environment. Our results showed that this parameter is also better in Isfahan Province because of there being more sunny days. A study by Hourani et al. has proved that daylight quality is an effective design element for enhancing the aesthetical and psychological aspects of architectural spaces, enriching the experience of pleasure [43]. In workplaces where employees spend extended periods, considerations beyond job performance, such as the overall pleasantness of the work environment, become important. In such settings, access to natural light should be ensured to enhance the vista parameter, or work shifts should be organized so that individuals have adequate exposure to daylight. Concepts such as biophilic design, commonly applied in buildings, can also be included in this context [44]. Today, biophilic interventions are gaining attention not only in architectural design but also in human–technology interactions [45].

Another subjective parameter which was assessed by the Ergonomic Lighting Indicator is vitality. It means one’s conscious experience as possessing energy and aliveness. In other definition, vitality was introduced as having positive energy available to or within the regulatory control of oneself. In this study, Isfahan, with more sunny days, conveyed that feeling to workers. The impact of daylight exposure on the overall health and vitality of office workers was the subject of a recent study. The results were in line with this study and proved the impact of daylight on the vitality of workers [46]. This statement has also been endorsed in systematic reviews [47]. Similarly,, to the previously mentioned subscales, this parameter also affects employees’ overall work-life quality.

The next variable was empowerment, which was asked of workers. It means that workers have an individual influence on lighting systems. It consists of individual control of the lighting scene, presence detection, daylight-responsive dynamic control, general dynamic control, flexibility, and privacy. Only this parameter was higher in Mazandaran than Isfahan. It can be claimed that workers in Mazandaran have a greater control over their received light than their peers in Isfahan. Therefore, it may be declared that, due to the lower availability of natural light on the one hand, and the greater use of artificial light on the other, workers have greater control over the amount of light they receive. Newsham et al. studied the effect of dimming control on office worker satisfaction. Their results showed that, after lighting control was made available to the workers, there were significant improvements in their lighting satisfaction. This difference may be attributed to the workers’ inability to adjust natural light in Isfahan [48].

According to the total score of the ELI, a closer look at the results indicated that the participants of Isfahan with a sunny climate are more satisfied with their lighting conditions than those in Mazandaran with a cloudy climate. This may be attributed to the adequate sunlight in their province and the use of natural light in their workplace. In line with the results of this study, a recent study has confirmed that access to natural light affects one’s perceived satisfaction [49]. Administering the Ergonomic Lighting Indicator before and after the initiation of lighting enhancement for workers could provide measurable information to evaluate the improvement of individual vision for work in the environment [50]. The absence of accurate artificial light management in these regions is one of the study’s limitations. However, the researchers attempted to match the types of bulbs and light intensity across the two sites. Participants in the study were asked to respond to questions based on how much light they typically received. However, it is possible that they did not notice this accurately.

The ELI provides a multi-criteria evaluation of lighting quality that extends beyond the basic safety-driven requirements reflected in the ILO ergonomic checkpoints (numbers 64–72) [51,52]. While the ILO checklist primarily focuses on minimum illumination, uniformity, glare prevention, task lighting, and maintenance, the visual performance dimension of the ELI corresponds most directly to these checkpoints by assessing illuminance levels, color rendering, uniformity and avoidance of glare, and disturbing shadows. The visual comfort dimension of the ELI partially aligns with the ILO recommendations on even lighting and the visibility of work areas, but goes further by incorporating criteria such as flicker-free operation, color temperature, and integration with daylight—elements not addressed in the ILO guidelines. In contrast, the vista, vitality, and empowerment dimensions of the ELI—concerned, respectively, with environmental identity, emotional stimulation through dynamic and adaptive lighting, and user control via dimming, scene selection, and sensor-based automation—have no equivalent in the ILO lighting checkpoints, which do not consider the experiential, aesthetic, brand, psychological, or adaptive control aspects of lighting. Thus, while both frameworks aim to support safe and effective visual conditions, the ILO provides a foundational compliance-oriented baseline, whereas the ELI incorporates a broader human-centered and experience-oriented perspective that reflects contemporary ergonomic thinking in workplace lighting design.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, the ELI, by considering multiple influential parameters, provides a practical and efficient screening tool for evaluating lighting quality across diverse indoor environments. It is user-friendly and can be applied by non-experts, such as employees, supporting ergonomics-based decision-making. Also, it is in line with the recommendations of the ILO about improving the lighting condition of the workplaces (ILO checkpoint).

Additionally, the findings highlight that natural daylight generally improves perceived lighting quality, but the impact varies across geographic and climatic conditions. Workplaces in sunny regions may receive higher levels of natural light, whereas those in cloudier climates may require adjusted lighting parameters to achieve comparable visual comfort and satisfaction, emphasizing the need to tailor lighting design to local environmental conditions.

Author Contributions

S.A.Z. and A.M. designed the study. M.R.A.S. and E.A. gathered data. S.M., in collaboration with the first and corresponding authors, wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. The last version of the manuscript has been read and verified by all of the authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.SPH.REC.1396.3177).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (protocol code IR.TUMS.SPH.REC.1396.3177).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be provided by an email to the corresponding author on a reasonable request due to legal and/or official procedures.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to gratefully thank the participants of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vetter, C.; Pattison, P.M.; Houser, K.; Herf, M.; Phillips, A.J.; Wright, K.P.; Skene, D.J.; Brainard, G.C.; Boivin, D.B.; Glickman, G. A review of human physiological responses to light: Implications for the development of integrative lighting solutions. Leukos 2022, 18, 387–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, A.R. Considerations for lighting in the built environment: Non-visual effects of light. Energy Build 2006, 38, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Z.; Gou, B.; Liao, W.; Bao, Y.; Deng, Y. Integrated lighting ergonomics: A review on the association between non-visual effects of light and ergonomics in the enclosed cabins. Build. Environ. 2023, 243, 110616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlazzo, F.; Piccardi, L.; Burattini, C.; Barbalace, M.; Giannini, A.M.; Bisegna, F. Effects of new light sources on task switching and mental rotation performance. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 39, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, A.R.; Bell, R.I. The CSP index: A practical measure of office lighting quality as perceived by the office worker. Light. Res. Technol. 1992, 24, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandewalle, G.; Maquet, P.; Dijk, D.-J. Light as a modulator of cognitive brain function. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2009, 13, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsham, G.R.; Veitch, J.A. Determinants of Lighting Quality I: State of the Science AU. J. Illum. Eng. Soc. 1998, 27, 92–106. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, M.; Jeninga, L.; Ouyang, J.Q.; van Oers, K.; Spoelstra, K.; Visser, M.E. Dose-dependent responses of avian daily rhythms to artificial light at night. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 155, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hye Oh, J.; Ji Yang, S.; Rag Do, Y. Healthy, natural, efficient and tunable lighting: Four-package white LEDs for optimizing the circadian effect, color quality and vision performance. Light Sci. Appl. 2014, 3, e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, A. A physiological basis for visual discomfort: Application in lighting design. Light. Res. Technol. 2016, 48, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardaljevic, J.; Andersen, M.; Roy, N.; Christoffersen, J. A framework for predicting the non-visual effects of daylight—Part II: The simulation model. Light. Res. Technol. 2014, 46, 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellia, L.; Bisegna, F.; Spada, G. Lighting in indoor environments: Visual and non-visual effects of light sources with different spectral power distributions. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 1984–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Uchiyama, Y.; Lee, S.; Shimomura, Y.; Katsuura, T. Effect of quantity and intensity of pulsed light on human non-visual physiological responses. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2017, 36, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.; Pedersen, E.; Maleetipwan-Mattsson, P.; Kuhn, L.; Laike, T. Perceived outdoor lighting quality (POLQ): A lighting assessment tool. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 39, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, P.R.; Eklund, N.H.; Hamilton, B.J.; Bruno, L.D. Perceptions of safety at night in different lighting conditions. Int. J. Light. Res. Technol. 2000, 32, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, F.; Bonaiuto, M.; Bonnes, M. Cross-Validation of Abbreviated Perceived Residential Environment Quality (PREQ) and Neighborhood Attachment (NA) Indicators. Environ. Behav. 2010, 42, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śwituła, M.; Wolska, A. Luminance of the Surround and Visual Fatigue of VDT Operators AU. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 1999, 5, 553–580. [Google Scholar]

- Wolska, A. Visual Strain and Lighting Preferences of VDT Users Under Different Lighting Systems AU. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2003, 9, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.A.; Rea, M.S.; Daniels, S.G. Effects of indoor lighting (illuminance and spectral distribution) on the performance of cognitive tasks and interpersonal behaviors: The potential mediating role of positive affect. Motiv. Emot. 1992, 16, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laike, T.; Kuller, R. The impact of flicker from fluorescent lighting on well-being, performance and physiological arousal AU. Ergonomics 1998, 41, 433–447. [Google Scholar]

- Dupláková, D.; Sloboda, P. The Maintenance Factor as a Necessary Parameter for Sustainable Artificial Lighting in Engineering Production—A Software Approach. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faranda, R.; Guzzetti, S.; Leva, S. Design and Technology for Efficient Lighting. In Paths to Sustainable Energy; Nathwani, J., Ng, A., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Benediktsson, G. Lighting Control: Possibilities in Cost and Energy-Efficient Lighting Control Techniques. Master’s Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, R.G.; Monteoliva, J.M.; Pattini, A.E. A comparative field usability study of two lighting measurement protocols. Int. J. Hum. Factors Ergon. 2018, 5, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, P.R. Light, lighting and human health. Light. Res. Technol. 2022, 54, 101–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houser, K.; Boyce, P.; Zeitzer, J.; Herf, M. Human-centric lighting: Myth, magic or metaphor? Light. Res. Technol. 2021, 53, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, N.H.; Boyce, P.R. The development of a reliable, valid, and simple office lighting survey. J. Illum. Eng. Soc. 1996, 25, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaji, A.; Shopian, S.; Nor, Z.M.; Chuan, N.-K.; Bahri, S. Lighting does matter: Preliminary assessment on office workers. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 97, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hygge, S.; Löfberg, H.A. POE Post Occupancy Evaluation of Daylight in Buildings: A Report of IEA SHC TASK 21/ECBCS ANNEX 29; Högskolan i Gävle: Gävle, Sweden, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Veitch, J.A.; Newsham, G.R. Exercised control, lighting choices, and energy use: An office simulation experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2000, 20, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, V.; Rodriguez, R.; Pattini, A. Expert consensus on integrative lighting descriptors and indicators for green building rating systems: A Delphi study. Light. Res. Technol. 2025, 57, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balocco, C.; Ancillotti, I.; Trombadore, A. Natural light optimization in an existing primary school: Human centred design and daylight retrofitting solutions for students wellbeing. Sustain. Build. 2023, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despenic, M.; Chraibi, S.; Lashina, T.; Rosemann, A. Lighting preference profiles of users in an open office environment. Build. Environ. 2017, 116, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begemann, S.H.A.; van den Beld, G.J.; Tenner, A.D. Daylight, artificial light and people in an office environment, overview of visual and biological responses. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 1997, 20, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisuit, A.; Linhart, F.; Scartezzini, J.-L.; Münch, M. Effects of realistic office daylighting and electric lighting conditions on visual comfort, alertness and mood. Light. Res. Technol. 2015, 47, 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, A.; Heracleous, C. Assessment of natural lighting performance and visual comfort of educational architecture in Southern Europe: The case of typical educational school premises in Cyprus. Energy Build. 2017, 140, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carli, M.; De Giuli, V.; Zecchin, R. Review on visual comfort in office buildings and influence of daylight in productivity. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference Indoor Air, Copenhagen, Denmark, 17–22 August 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, E.; Hu, J.; Patel, M. Energy and visual comfort analysis of lighting and daylight control strategies. Build. Environ. 2014, 78, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasi, M.A.; Budaiwi, I.M. Energy performance of windows in office buildings considering daylight integration and visual comfort in hot climates. Energy Build. 2015, 108, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishegar, N.; Boubekri, M. Natural light and productivity: Analyzing the impacts of daylighting on students’ and workers’ health and alertness. In Proceedings of the International Conference on “Health, Biological and Life Science” (HBLS-16), Istanbul, Turkey, 18–19 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aries, M.; Aarts, M.; van Hoof, J. Daylight and health: A review of the evidence and consequences for the built environment. Light. Res. Technol. 2015, 47, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoop, M.; Stefani, O.; Bueno, B.; Matusiak, B.; Hobday, R.; Wirz-Justice, A.; Martiny, K.; Kantermann, T.; Aarts, M.P.J.; Zemmouri, N.; et al. Daylight: What makes the difference? Light. Res. Technol. 2019, 52, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourani, M.M.; Hammad, R.N. Impact of daylight quality on architectural space dynamics: Case study: City Mall—Amman, Jordan. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 3579–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madias, E.-N.D.; Christodoulou, K.; Androvitsaneas, V.P.; Skalkou, A.; Sotiropoulou, S.; Zervas, E.; Doulos, L.T. The effect of artificial lighting on both biophilic and human-centric design. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedeh Mosaferchi, M.I.; Vitiello, G.; Mortezapour, A.; Naddeo, A. Towards More Trustworthy Automated Driving: Comparing Anthropomorphic and Biophilic Interfaces. In Proceedings of the CHITALY 2025, Salerno, Italy, 6–10 October 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Boubekri, M.; Cheung, I.N.; Reid, K.J.; Wang, C.-H.; Zee, P.C. Impact of windows and daylight exposure on overall health and sleep quality of office workers: A case-control pilot study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2014, 10, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beute, F.; de Kort, Y.A.W. Salutogenic Effects of the Environment: Review of Health Protective Effects of Nature and Daylight. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2014, 6, 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newsham, G.; Veitch, J.; Arsenault, C.; Duval, C. Effect of dimming control on office worker satisfaction and performance. In Proceedings of the IESNA Annual Conference, Tampa, FL, USA, 25–28 July 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Day, J.K.; Futrell, B.; Cox, R.; Ruiz, S.N.; Amirazar, A.; Zarrabi, A.H.; Azarbayjani, M. Blinded by the light: Occupant perceptions and visual comfort assessments of three dynamic daylight control systems and shading strategies. Build. Environ. 2019, 154, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, S.; Bowen, P.G.; Hallman, M.G.; Heaton, K. Visual Performance and Occupational Safety Among Aging Workers. Workplace Health Saf. 2019, 67, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, M.; Zakerian, S.A.; Salmanzadeh, H. Prioritizing the ILO/IEA Ergonomic Checkpoints’ measures; a study in an assembly and packaging industry. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2017, 59, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. Ergonomic Checkpoints: Practical and Easy-to-Implement Solutions for Improving Safety, Health and Working Conditions, 2nd ed.; International Labour Office, Ed.; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).