Abstract

Employee satisfaction is a crucial factor affecting organizational performance, productivity, and overall workplace efficiency. This study investigates employment satisfaction within the Greek technology sector through sentiment analysis, focusing on employees’ responses through the Employee Experience-Satisfaction (EmEx-Sa) questionnaire. The study employs natural language processing (NLP) and, in particular, the lexicon-based sentiment analysis methodology to analyze data from 208 employees across the entirety of Greece, obtained from open and semi-open questions, multiple-choice alternatives, and demographic questions. The objective is to utilize data from sources such as the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire (MOAQ), Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) and Job Descriptive Index (JDI) to determine the primary elements that impact job satisfaction and, by applying principles of organizational ergonomics, gain insight into the attitudes and emotions of employees. Results reveal that the working environment (total sentiment score: 21.50) is the primary driver of positive sentiment, while salary (total sentiment score: −18.72) is the main source of dissatisfaction. Sentiment regarding superiors is more balanced, leaning slightly positive (total sentiment score: 0.02), but the analysis indicates opinions lack significant polarization. The findings delineate critical factors influencing job satisfaction, encompassing the work environment, leadership quality, salary, and opportunities for professional advancement. The research underscores the significance of internal marketing tactics in fostering engagement, trust, and transparency between management and employees and provides actionable suggestions for boosting working conditions, fostering employee well-being, and improving organizational performance, underscoring the strategic imperative of prioritizing job satisfaction.

1. Introduction

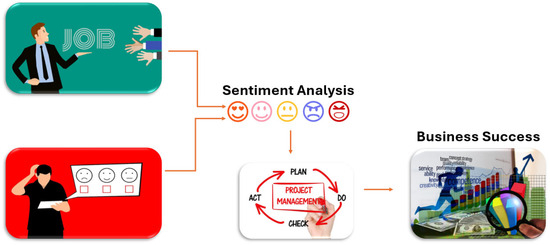

Job happiness is a constituent of one’s total life satisfaction. Job satisfaction is a subjective emotional response to one’s employment, which is a widely recognized and thoroughly examined topic within organizational psychology [1]. Success within the organization is based on employee satisfaction, which has a major impact on productivity and the overall performance of the company. A thorough investigation revealed that the correlation between job satisfaction and organizational performance was more robust than the correlation between organizational performance and job satisfaction. One could argue that job satisfaction has a greater influence on organizational effectiveness than the other way around [2]. The goal is to gain a thorough understanding of the factors that contribute to employee satisfaction by examining the attitudes and sentiments expressed by employees about their jobs, salaries, communication with colleagues and superiors and work environment. Sentiment analysis employing lexicon-based techniques while considering their particular advantages and limitations is necessary to investigate employee job satisfaction. The open/semi-open questions “How do you think about your job as a whole?” and “What are the three to five words that come to your mind when you think about your job?” that are inspired by MOAQ, MSQ and JDI can be used as a reliable and accurate implement to evaluate and authenticate employees’ satisfaction [3]. Organizational psychology roots these surveys, which use the Likert scale for closed questions. Nonetheless, this paper necessitates a modification to incorporate open and semi-open questions, leading to the creation of a questionnaire named EmEx-Sa. The study aims to foster a culture of transparency, trust, and mutual respect within organizations by recognizing the essential role of employee satisfaction in enhancing communication between management and staff. Sentiment analysis methods will assess negative, neutral, and positive sentiments to ascertain the level of satisfaction [4]. Figure 1 presents the comprehensive methodology employed in this research.

Figure 1.

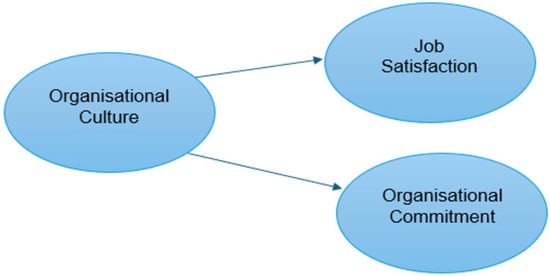

Correlation between the organizational culture, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment.

Directors will benefit from this article in their decision-making processes and utilize the EmEx-Sa questionnaire inside their enterprises to evaluate the outcomes derived from employee responses. Numerous aspects can affect an individual’s job happiness, such as remuneration and benefits, perceived equity in the promotion process, quality of the work environment, leadership efficacy and interpersonal interactions, and the intrinsic character of the job itself [5]. In the final analysis, employee satisfaction is not only a corporate privilege but also a strategic necessity that has a substantial impact on business performance and competition.

Employee satisfaction is a strategic necessity that has a strong impact on organizational performance. To guide this investment, providing a clear goal, this case study seeks to answer the following research questions:

- How can lexicon-based sentiment analysis of employees’ responses be used to identify the main factors that influence job satisfaction?

- What are the primary sentiments (positive, negative or neural) among employees in relation to major workplace factors such as working environment, salary and superiors?

- What evidence-based decisions can employers implement based on sentiment analysis results to enhance employee happiness and cultivate a more positive work culture?

Research Context

In recent years, various scientific studies have examined employee job satisfaction. The study in [6] defines job satisfaction in organizational psychology, with Locke [7] characterizing it as “a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences.” Further definitions were subsequently introduced, occupying the aforementioned space. The assessment of job satisfaction is conducted with psychology-based questionnaires. Numerous hypotheses about the antecedents of job happiness have been articulated in the organizational literature, with the Job Characteristics Model (JCM) positing that positions endowed with intrinsically compelling attributes will result in elevated levels of job satisfaction. In [8], elucidate the distinctiveness of an organization, as manifested via the common principles and ideals instituted by the founders and conveyed through various means. Organizational culture, job dedication, performance, and loyalty are frequently examined in conjunction with job satisfaction, which is relevant to an employee’s emotional state regarding their workplace. The study finds that an organization’s loyal and committed personnel may indicate job satisfaction, which is crucial for attaining its objectives. In [2], this study aims to investigate the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational performance. Despite the relatively low degree of intensity, the results of this study demonstrate that there is a distinct link between the job satisfaction of employees and the performance of the organization. The analysis indicated that the correlation between job satisfaction and organizational performance was more robust than the association between organizational performance and job satisfaction. The study [9] aims to examine the benefits of healthy workplaces for both individuals and organizations, specifically in relation to employee happiness, labor productivity, and facility costs. The review lends credence to the notion that proper building characteristics have advantageous effects on productivity, satisfaction, and health. The results improve comprehension of the intricate links between tangible characteristics of the environment and health, satisfaction, productivity, and costs. In [10], the authors demonstrated the usefulness of Computer-Aided Text Analysis (CATA) approaches in developing text-based job satisfaction ratings using replies from both completely open and semi-open questions. Three sentiment analysis techniques were used to enhance text analysis: Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count SentimentR, and SentiStrength, and they quantified the forms of measurement error they introduced: specific factor error, algorithm error, and transient error. The study utilized three sentiment analysis methodologies: Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count, SentimentR, and SentiStrength. It also measured the types of measurement error introduced by these techniques, namely specific factor error, algorithm error, and transitory error. The study by [11] investigates the application of semi-open satisfaction questions that may be effectively and conveniently transformed into a textual metric utilizing two forms of computer-assisted sentiment analysis: SentimentR, Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC). Ultimately, depicting the responses to the semi-open inquiry can refine the computer-aided sentiment analysis lexicons and elucidate the determinants of job happiness. Bonda [12] emphasizes the necessity of gathering and analyzing online opinions. This article employs NLTK, TextBlob, and the VADER sentiment analysis tool to classify movie reviews obtained from the website www.rottentomatoes.com, provided by Cornell University. This analysis evaluates different strategies to identify the most effective method for sentiment classification. The experimental findings of this study demonstrate that VADER surpasses TextBlob in performance. The work in [13] delineates an approach for analyzing Greek textual data and extracting significant insights into the author’s perspective. A supervised approach is presented, which classifies user-generated comments into the appropriate polarity category. A comprehensive experimental study was undertaken to examine consumers’ attitudes and opinions regarding the e-lectures they attended. The results were highly encouraging, validating the precision and usefulness of the approach in appropriately categorizing opinions. Gelbard [14] present a theoretical framework for evaluating human characteristics by modeling key performance indicators and delineating the explanatory elements, manifestations, and various accompanying digital footprints of these indicators. The authors employ sentiment analysis to provide a method for assessing various elements of the suggested human factors ontology. The Enron email corpus served as a case study to illustrate how digital traces might forecast such situations.

In all the aforementioned studies, the researchers focus on job satisfaction using closed-ended questionnaires or a sentiment analysis of organizations’ comments on online platforms. Therefore, a key novel point of this work is the sentiment analysis on an open-ended questionnaire based on organizational psychology based on a lexicon-based algorithm. This study collected responses over a two-month period from employees in Greece’s technology sector, employing a dual methodology of public recruiting via social media and targeted dissemination by HR departments within the participating firms. The results of natural language processing will provide useful insights for managers of organizations seeking to understand job satisfaction parameters that affect employees and measures that should be taken to improve their overall workplace and business success.

2. Job Satisfaction

The examination of job satisfaction captivates both employees and researchers [5]. In the discipline of industrial and organizational psychology, this job attitude has been the subject of extensive examination and significant research. Moreover, in the domain of organizational sciences, job satisfaction is crucial to several theories and models about human behaviors and attitudes [15]. Examining job satisfaction has significant practical implications for enhancing individual well-being and maximizing organizational efficacy.

Hulin and Judge observed that job satisfaction encompasses several psychological responses to employment, including cognitive (evaluative), affective (emotional), and behavioral elements [16]. Job satisfaction refers to an employee’s evaluation, disposition, or emotional state concerning their employment. The factors include the nature of the job, the work environment, interpersonal interactions with colleagues, salary, and social dynamics inside the working environment [17].

The predominant phrase used in organizational studies to define job satisfaction is “a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the evaluation of one’s job or job experiences” (p. 1304) [7]. Individuals’ job satisfaction is significantly influenced by their values, as per Locke. Only unsatisfied job values that are meaningful to the individual can result in dissatisfaction [18]. Locke’s value-percept model posits that job satisfaction can be quantified using a mathematical equation:

- S denotes satisfaction.

- Vc represents the value content, indicating the desired amount.

- P represents the perceived value derived from the job.

- Vi is the importance of value to the individual.

The value-percept theory asserts that dissatisfaction occurs when there is a discrepancy between expected and actual outcomes, contingent upon the significance of the specific job element to the individual. Individuals engage in a cognitive evaluation of various facets of their job satisfaction, a process that is reiterated for each distinct aspect of their employment. Overall job satisfaction is assessed by consolidating all aspects of the occupation, taking into account their relative importance to the individual [19]. According to Eid [15], the value-percept model evaluates job satisfaction by examining the outcomes of employees’ jobs and their values. Job satisfaction and subjective well-being are consistently and robustly correlated, according to empirical data. Every evaluated study has identified substantial correlations between life satisfaction and work satisfaction.

2.1. The Link Between Job Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction

What is the relationship between job satisfaction and life satisfaction? The definition and understanding of happiness can be approached from both hedonic and eudaimonic perspectives. The hedonic approach characterizes satisfaction as the attainment of pleasure and the evasion of pain. Subjective well-being, which encompasses cognitive elements such as life satisfaction and affective components that include both positive and negative emotions, is frequently used to define happiness [20]. Life satisfaction denotes an individual’s evaluation of their existence across various domains and serves as the primary metric for assessing subjective well-being [1]. A significant correlation exists between elevated life satisfaction and positive organizational outcomes, including increased career satisfaction, commitment to the organization, and particularly, work satisfaction [5]. Most definitions of job satisfaction focus on the emotional and mental dimensions of employees’ perceptions and attitudes regarding their work. Similarly to life satisfaction, these criteria comprise cognitive evaluations of employment, affective responses, feelings, and emotional states [20].

Two distinct models can comprehend the correlation between job satisfaction and life contentment:

- The top-down model.

- The bottom-up model.

“Basic differences in personality and affectivity predispose people to be differentially satisfied with various aspects of their lives, including their jobs” [21] is the dispositional explanation offered by the top-down approach. Consequently, individuals’ emotional states affect their evaluations of their work [20]. A comprehensive study has shown a robust association between elevated life satisfaction and numerous favorable results for companies. These results encompass enhanced career happiness, organizational commitment, and, particularly pertinent in this case, job satisfaction [8]. Job satisfaction is a vital indicator of employees’ overall well-being and can consequently influence their entire life’s happiness. Consequently, the bottom-up approach advocates for a contextual explanation. That is, “because the job is an important part of adult daily life, people who enjoy their jobs will report greater overall satisfaction with their lives” [21]. Research consistently shows a positive correlation between job happiness and overall life contentment [20]. The causal influence of job satisfaction on life satisfaction underscores the importance of work in persons’ lives and is the most frequently posited direction of the relationship.

2.2. Relationship Between Organizational Culture, Employee Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment

An organization consists of individuals who share common objectives and function within a flexible framework that adapts to changing external conditions. Regardless of a firm’s size or industry, three fundamental components are adopted: goals, people, and systems [8]. Individuals engage within a system, facilitating the achievement of an organization’s objectives. Each institution establishes a unique culture that includes its goals, principles, and engagement with the outside world. The culture of an organization is determined by the emotions, convictions, principles, traditions, and regulations that underpin its foundation. Establishing a strong and positive company culture enhances employee dedication and accountability. It consolidates employee aspirations, allowing for a concentrated effort towards goal achievement. Employees who are dedicated and loyal demonstrate job satisfaction, which is indispensable for accomplishing an organization’s objectives.

Schein develops the definition that is frequently considered the most well-liked and concise [22]. Schein defines organizational culture as the basic beliefs created by a group to handle outside challenges and work well together inside, which have been successful enough to be accepted as true and taught to new members as the right way to think and feel about those challenges [23]. He posits that culture is a dynamic phenomenon emerging from individual interactions and shaped by leadership behaviors. The framework comprises a set of structures, routines, rules, and standards that offer guidance and impose limitations on conduct. Organizational culture has been studied in relation to multiple elements, such as leadership and employee performance, along with its impact on leadership style, organizational commitment, and its relationship with job satisfaction [8].

2.3. Six Crucial Factors of Organizational Culture

Heskett [23] posits that organizational culture contributes to 20–30% of the disparity in company performance relative to competitors without a substantial culture. Coleman highlighted six crucial elements that contribute to the success of corporate cultures [24]:

- Vision: A clearly articulated objective or purpose furnishes an organization with a distinct trajectory, shaping staff decision-making and fortifying ties with consumers and suppliers.

- Values: The values of an organization are the essential principles that underpin its culture. The staff formulates standards to enhance communication, maintain professional integrity, and fulfill the institution’s goals.

- Practices: An organization must adhere to specific values by executing corresponding practices. To facilitate the incorporation of these practices into the organization’s daily operations, it is essential to highlight them in evaluation criteria and promotion protocols. It is imperative to foster and facilitate the active engagement of junior team members in discussions within an organization characterized by both egalitarian and hierarchical cultures, ensuring they feel secure and unencumbered by adverse repercussions.

- Individuals: Both current and prospective employees must wholeheartedly adopt an organization’s beliefs. Individuals who are not only talented but also compatible with the organization’s unique cultural attributes should be prioritized in recruitment practices.

- Narrative: It is essential to acknowledge, shape, and articulate an organization’s unique history as a fundamental aspect of its ongoing culture.

- Location: An essential element of corporate culture is its physical positioning and working environment, which are evaluated according to geography, architecture, and esthetic design.

These factors are highly likely to influence the values and behaviors of employees, thereby improving the performance and effectiveness of the organization [1].

2.4. Organizational Commitment

Organizational commitment refers to an individual’s propensity to either continue their work with an organization or to resign from it. Employees are generally attracted to companies that cultivate a culture, valuing their contributions and emphasizing the organization’s overall well-being [8]. Organizational commitment refers to the manner in which individuals demonstrate their devotion and dedication to the organization. Demonstrating this dedication are employees who are committed to the organization and actively contribute to its objectives. These individuals exhibit loyalty and endeavor to preserve their connection with the organization [17]. Employees’ job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and organizational culture are positively correlated [18]. This is apparent in the compliance of organizational members with the established regulations of the organization. When an organization is well-structured under a leader who exhibits strong authority and accountability, its members will undoubtedly show a high degree of commitment to the company. Organizational commitment is more likely to be demonstrated in organizations that prioritize collaboration, camaraderie, active participation, consensus-building, constructive behavior, and support. Figure 1 represents a conceptual framework demonstrating the impact of organizational culture on job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Person-organization fit denotes the extent of alignment between an individual’s values, objectives, and requirements and those of the organization [25]. Compatibility between the organizational environment and the individual’s traits is also included. If the firm meets the standards of its people, it can achieve compliance. As the degree of person-organization alignment escalates, it exerts a greater influence on the company’s targeted objectives. This encompasses improving job happiness, cultivating organizational commitment, and decreasing employee turnover.

Turnover intentions denote the propensity to leave an organization without having yet executed the actual shift to another workplace. Should the urge arise, it will be reflected in employee behavior characterized by heightened absenteeism, an increase in violations of workplace norms, the audacity to challenge or protest against superiors, and a diminished sense of accountability regarding task completion.

2.5. Motivation of Employees

Organizational characteristics, such as boosting motivation, commitment, and engagement levels, are essential in the current day. The design of compensation systems is crucial in inspiring individuals to achieve exceptional performance, exert discretionary effort, and make significant contributions. The process of motivation often commences when an individual identifies an unfulfilled need. A specific objective is set to fulfill the criteria. Individuals may be motivated to achieve a specific objective through the use of rewards and incentives. The degree of motivation may also be influenced by the social situation [19]. This context encompasses the core values and beliefs of an organization, its operational methodologies, the leadership, management practices, and the impact of the team with which an individual collaborates.

Motivation can be classified into two categories: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic motivation refers to the condition in which individuals are propelled by the inherent satisfaction and joy derived from participating in an activity that aligns with their personal requirements. Various factors influence intrinsic motivation, including autonomy, the desire for skill enhancement, challenging undertakings, and opportunities for promotion. Extrinsic motivation refers to the degree to which external variables are employed by others to inspire and incentivize individuals. Extrinsic motivation pertains to external incentives offered by management, such as enhanced salaries, recognition, or prospects for advancement [18].

Wages constitute a portion of the compensation provided to an employee in return for their work and function as a primary source of motivation and inspiration. The efficient management of the company’s compensation system can enhance employee motivation, productivity, and happiness. The organization’s employees exhibit significant dissatisfaction with their current remuneration. This indicates that the workers’ remuneration is falling short of their expectations, prompting them to pursue higher compensation. As it possesses the capacity to substantially enhance employee motivation and productivity, managers should contemplate this matter.

Due to the substantial influence of incentives on employee productivity, the concept of incentives receives enormous focus, particularly in the realm of attracting highly trained individuals capable of successfully achieving the organization’s goals. The significance of incentives is derived from the recognition and compensation of employees for their contributions. Providing incentives to recognize and fulfill an individual’s intrinsic desires is a vital component of reality [18]. Consequently, researchers have meticulously endeavored to develop a thorough elucidation on improving employee professionalism and the administration’s strategy for selecting proactive employees. Furthermore, they have investigated strategies to synchronize institutional aims with individual aspirations, ultimately improving performance. Successful organizations generally establish a proactive rewards system that can enhance employee productivity, encouraging them to increase their efforts and achieve the organization’s objectives [5].

2.5.1. Impact of Working Environment on Employee’s Motivation and Satisfaction

The two primary dimensions of the working environment are work and context. Work encompasses various job-related components, including the methods of execution and completion. This includes the intrinsic worth of a task, task diversity, autonomy over job-related activities, a feeling of achievement, as well as activities and training [26]. A multitude of studies have concentrated on the intrinsic elements of job happiness. According to research findings, internal factors, such as the work environment, are directly correlated with job satisfaction [9]. Furthermore, they indicated that the second dimension of job satisfaction, referred to as context, includes both the material and interpersonal working conditions. Multiple factors in the workplace, including compensation, work hours, individual autonomy, organizational structure, and communication between staff and management, can influence job satisfaction. Arnetz (1999) asserts that within organizations, employees frequently have challenges with supervisors who do not accord them the requisite level of respect they deserve [27]. Authoritarian conduct from superiors fosters an uncomfortable atmosphere for employees, impeding their willingness to share constructive and innovative ideas with their superiors. Furthermore, higher management confines individuals to their designated responsibilities rather than promoting accountability through team collaboration to attain outstanding outcomes [26].

2.5.2. Factors That Impact Employee Job Satisfaction

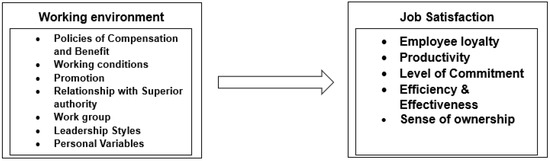

Diverse elements of the workplace, including wage and benefits regulations, leadership styles, and individual factors, can profoundly impact job satisfaction, as illustrated in Figure 2. Effective management of these environmental characteristics yields beneficial consequences, including enhanced employee loyalty, increased productivity, strengthened commitment, improved efficiency and effectiveness, and an elevated sense of ownership inside the firm.

Figure 2.

Working environment and Job Satisfaction.

Compensation and Benefits Policies: This characteristic is crucial in assessing employee satisfaction. Compensation denotes the expected remuneration that an employee expects from their job [5]. Employees should be satisfied with competitive compensation packages and derive pleasure from comparing their earnings to that of external individuals employed in the same industry. Achieving just and equitable rewards engenders a sense of contentment. The following points can be categorized as follows:

- Remuneration for the completed work.

- A supplementary advantage or incentive.

- Benefits including medical allowance, educational allowance, and home rent allowance (HRA) are offered.

Working conditions: Advantageous working conditions that provide a feeling of security, comfort, and motivation substantially inspire employees. Conversely, employees experiencing adverse working conditions may experience anxiety regarding their physical health [5]. Employee productivity escalates in direct correlation to the comfort level of the working environment. The elements included in this category are as follows:

- Experiencing a sense of security and comfort in the employment.

- Implements and equipment.

- On-site security personnel and parking amenities are provided.

- Operational methodologies.

- The room is sufficiently aired and equipped with ample lighting, fans, and air conditioning. The office space, lounge area, and restrooms are meticulously maintained and impeccably clean.

Promotion and Professional Growth: A promotion is a notable accomplishment in an individual’s life. It provides and satisfies enhanced remuneration, responsibility, authority, autonomy, and status [5]. Happiness among employees is contingent upon their prospects for advancement. The subsequent points belong to this category:

- Prospect of career progression.

- Gender equality concerning possibilities for advancement irrespective of gender.

- A training initiative.

- Opportunity to employ skills and competencies.

Relationship with Superior Authority: A positive working relationship with a supervisor is crucial, as their professional knowledge, constructive comments, and comprehensive understanding are necessary at every level [5]. The following points can be classified under this category:

- Engagement with the immediate supervisor.

- Interactions between staff and upper management.

- Employee treatment.

Work group: Humans possess an intrinsic tendency to participate in social interactions [14]. Consequently, the existence of groups within an organization is a recognized phenomenon. This attribute facilitates the formation of work groups in the workplace. Isolated workers have a pronounced aversion to their employment. Workgroups significantly influence employee satisfaction. This category encompasses the following points:

- Interpersonal engagements with fellow group members.

- Group interactions.

- The strength of the intra-group link is crucial.

- Yearning for social interaction.

Leadership Styles: The leadership approach directly influences job satisfaction levels. The democratic leadership style markedly enhances employee satisfaction [14]. Democratic leaders foster collaboration, respect, and amicable relationships among employees. Conversely, personnel subjected to authoritarian and dictatorial leadership generally demonstrate reduced job satisfaction. The subsequent points belong to this category:

- A leadership style that is inherently democratic.

- Relationships and friendships defined by respect and warmth.

Personal Variables: The individual variables substantially influence the sustenance of employee motivation and personal attributes, facilitating their operation with heightened effectiveness and efficiency. Employee satisfaction can be influenced by psychological factors [14]. Consequently, numerous individual factors influence employee pleasure. This category has five variables:

- Personality traits shaping behavior and motivation.

- Expectation refers to the hopes and beliefs about job outcomes.

- Age influences the life stage’s work preferences.

- Educational skills and knowledge affect engagement.

- Gender differences and variations in workplace experiences.

2.5.3. Impact of Healthy Workplaces on Employee’s Motivation and Satisfaction

A healthy workplace fosters the physical, mental, and social welfare of its inhabitants. The complex interaction of individuals’ physiological, psychological, emotional, and organizational resources, as well as the stress derived from their physical and social settings at work and home, influences their health. The influence of the physical environment on health and well-being has become increasingly evident in recent decades [9]. This improvement may be ascribed to the shift from a singular focus on cost reduction to a holistic and integrated value-based approach, alongside attaining an optimal balance between the costs and benefits of interventions in buildings, facilities, and services. The detrimental impact of an inadequate indoor environment, noise, and distractions on employees’ health and well-being is apparent. Conversely, a healthy workplace can be cultivated by facilitating opportunities for communication, focus, and interaction with nature. According to a poll of 2000 office workers, they prefer a bright workspace with access to outdoor spaces, peaceful locations for introspection, and coworker assistance [9]. They also wanted to find a good balance between private and collaborative spaces. However, the primary causes of frustration included noise in open-plan areas, inadequate natural light, absence of color and greenery, lack of artwork, inadequate ventilation, limited personal control over temperature, lack of privacy, clutter, and inflexible space.

3. EmEx-Sa Questionnaire

Surveys infrequently incorporate open and semi-open items regarding work happiness, despite their capacity to mitigate biases and enhance information collection [28]. Manual coding’s exorbitant costs and the difficulties that arise during text measure verification are the primary reasons for this [11]. Recently, computer-assisted text analysis methods, like lexicon-based algorithms, machine learning models, and contextual analysis, have reduced the need for scholars to use manual coding when creating text measurements. However, there is still a lack of understanding about how accurate the text metrics produced by computer-aided text analysis techniques are, and only a few studies have tried to show their added value [10]. Consequently, this research includes a questionnaire that encompasses demographic and general workplace information, in addition to open-ended and semi-open-ended questions, coupled with a single multiple question. The methodology predominantly utilizes open and semi-open questions to collect pertinent information through lexicon-based techniques [28]. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is strictly enforced by the questionnaire, which guarantees that all responses are submitted anonymously. The primary objective of this questionnaire is to investigate employees’ experiences within the workplace and identify the variables that contribute to their satisfaction.

3.1. Questionnaire and GDPR

A substantial regulatory development in the realm of information policy, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), has had a profound influence on numerous facets of data protection and privacy. The GDPR creates a comprehensive legal framework for the management of personal data, which will influence global practices on personal data usage [29]. A thorough understanding of the GDPR encourages organizations to implement information governance frameworks, internalize data utilization, and engage individuals in decision-making processes. The GDPR puts strict rules in place to achieve these goals, including systems that help spot violations but offer few rewards. The implementation of the GDPR will introduce complexity and impose constraints on specific business models that significantly depend on data gathering and processing. Nonetheless, the GDPR will permit solutions that were previously unfeasible under less stringent regulations.

This questionnaire collects data from employees to perform sentiment analysis regarding their level of job satisfaction. This research collects personal data, including demographic information; this indicates that the questionnaire must protect this data, utilize it exclusively for this purpose, and avoid sharing it with external parties. The questionnaire commences with a concise text that emphasizes the voluntary nature of participation, the anonymity of the participants, and the ability to exit the page at any time. Moreover, those seeking to withdraw their responses from the data collection may contact the creator of the questionnaire. Consequently, answering a binary question indicates my consent to the collection and use of my data in accordance with the privacy statement.

3.2. Comparison of Closed and Open—Semi-Open Questions

It is unfortunate that semi-open or open-ended job satisfaction questions are infrequent, despite their considerable potential to augment closed questions in surveys. A semi-open or open question can be used to more precisely assess job happiness, as the constraints of individual methods are likely mitigated by employing many procedures [11]. Using both closed and open-ended questions in one survey to measure job satisfaction can help reduce common mistakes by prompting respondents to think in different ways. Employing semi-open or open-ended questions can enhance the evaluation of job satisfaction, resulting in a more thorough and nuanced comprehension of a certain topic [30]. Textual responses can elucidate the context and clarify the causes and origins of job satisfaction or discontent when addressing closed questions.

Enhancing closed questions with open questions can provide multiple benefits. A strategy for reducing the common method biases in questionnaires that primarily contain closed questions is to incorporate open questions as a countermeasure [28]. For instance, respondents who reply without thorough contemplation may adversely impact closed-question survey scales. The inclusion of open-ended questions is thought to encourage respondents to offer more reflective answers [10]. When responding to open-ended questions, respondents are required to adopt a unique and potentially more rigorous cognitive processing style. Using open questions alongside closed ones enhances the ability to apply triangulation techniques. Researchers utilize open questions to assess the construct validity of closed questions and also employ the replies from open questions to enhance their comprehension of the examined construct [28]. Researchers can utilize the responses to evaluate the timing, rationale, and techniques employed to demonstrate a subject. Furthermore, they can examine the psychological mechanisms influencing self-reported responses to closed survey questions, whereas open-ended questions typically generate more spontaneous and comprehensive replies.

Text-based measures, infrequently employed, have examined job satisfaction through responses to open-ended questions. Such an outcome indicates a lost opportunity, as evidence demonstrates that assessing job satisfaction is intricate and that closed-ended measures often encounter issues with inattentive or negligent responses [10]. Employing sentiment analysis appears to be a suitable approach for developing a metric derived from text. Numerous empirical studies demonstrate that the emotional tone expressed in texts distinctly reflects employees’ positive and negative emotions, attitudes, and thoughts, all of which substantially influence their overall job satisfaction.

3.3. Questions’ Analysis

The EmEx-Sa questionnaire comprises multiple-choice, semi-open, and closed questions for analysis, yielding important insights into employee work satisfaction. Additionally, demographic questions will be incorporated alongside statistical data to facilitate analysis. The questionnaire is analyzed in Appendix A.

Question 1 will ascertain whether the participant consents to the collection and processing of their data in compliance with the GDPR. The participants’ responses were submitted anonymously. The gathered data will exclusively be utilized for this research and will not be shared with anyone else.

Questions 2–6 collect demographic information regarding the respondent’s gender identity, age, highest educational attainment, duration of employment at the current organization, and job position or hierarchical level within the organization. The main objective of demographic data is to categorize and compare various demographic groups through quantitative results presented in summarized visualizations.

Questions 7 and 8 in this questionnaire comprise open and semi-open questions, which constitute the primary emphasis of the EmEx-Sa’s survey. “How do you think about your job as a whole?” The second question is, “What three to five adjectives come to mind when you think about your job?”; both function as alternatives to closed survey questions and evaluate overall job satisfaction [10]. In instances of open questions with many interpretations and when absolute clarity is frequently elusive, a proposed or provisional response is not only permissible but also advantageous [31]. To facilitate their understanding of the purpose of the query, the participants are provided with an example for each of the questions. The responses to these questions will be analyzed through sentiment analysis to yield significant insights into employee work satisfaction in Greek companies and organizations.

Question 9 is a multiple-choice question designed to collect statistical data regarding the demands of employees in Greek organizations, with the objective of identifying the principal aspects that contribute to elevated job satisfaction.

4. Data Analysis

Following a five-week duration of diligently compiling information through the questionnaire, it is now time to analyze the gathered data. Reviewing the privacy statement in compliance with GDPR is crucial before processing any data. Before conducting sentiment analysis, it is necessary to clean and preprocess the text to improve its accuracy and simplicity.

The importance of open and semi-open questions resides in their incorporation of free-text responses, necessitating participants to regulate any incorrect language employed. These words will be incorporated into sentiment analysis and preprocessing due to their importance, which lends gravitas to the terms they describe.

4.1. Demographic Overview—Descriptive Statistics and Job Improvement Preferences

Textual data limits the scope of descriptive analysis. Nonetheless, it is beneficial to analyze demographic statistics for a more thorough grasp of the data.

- The participants are distributed as follows: 54.7% are male, 44.8% are female, and 0.5% are classified as “other.”

- The age distribution among males and females is as follows: 54.2% are aged 25–34, 14.9% are aged 35–44, 13.9% are aged 18–24, 10.9% are aged 45–55, and 6.0% are over 55 years old.

- Of the individuals surveyed, 47.3% hold a university or college degree, 22.9% possess a master’s degree, 17.4% have completed high school or an equivalent education, 10.4% have had vocational training or an apprenticeship, and 2.0% have achieved a doctoral degree.

- The allocation of positions is as follows: 52.7% are senior managers, 28.9% are middle managers, 9% are junior managers, 5.5% are technical staff, and 4% are external personnel.

- 38.8% of employees have been with the company for 1 to 4 years, 27.4% for 5 to 10 years, 13.9% for less than 1 year, 12.9% for more than 15 years, and 7% for 11 to 15 years.

The summary of the demographic overview provided by Appendix A is as follows:

The multiple-choice question, “Which of the following is missing from your job and would improve your satisfaction?” provides an opportunity to identify aspects of an employee’s employment that could be improved. Table 1 illustrates the aggregate quantity for each option shorted and the percentage per choice.

Table 1.

Multiple-choice questions’ results.

Table 1 shows the total amount for each option for the multiple-choice question (participants could select more than one answer) shorted; the percentage of responses (n = 411) reflects each option’s share of all answer selections, while the percentage of respondents (n = 202) reflects the proportion of participants who chose that option. It appears that a limited number of employees are convinced that all operations at their job are running optimally Each organization’s management must certainly consider this factor. Employee feedback suggests the necessity to enhance factors such as compensation, communication with coworkers and upper management, and the workplace environment.

4.2. Preprocessing of the Textual Data

The complicated grammatical and syntactic rules of Greek make it a typical high inflection language. It is an especially difficult language for neuro-linguistic programming and specifically for sentiment analysis [32]. For example, in English, the regular verb “ask” has only four forms (ask, asks, asked, asking), whereas the regular Greek verb “ρωτώ” has 93 distinct forms [33].

Pre-processing denotes the process of eliminating noise and enhancing the data to render it appropriate for categorization [32]. The categorization process is expedited by preprocessing, which assists in the real-time implementation of sentiment analysis. The application of a specialized pre-processing technique for the Greek language can markedly enhance the development of domain lexicons. The preprocessing techniques are outlined as follows:

- Eliminate responses for which participants did not provide consent, in compliance with the privacy statement.

- Eliminate non-Greek vocabulary, URLs, @mentions, hashtags, punctuation, and extraneous spaces.

- Eliminate punctuation and convert the words to uppercase to avert complications with accentuation.

- Eliminate superfluous letters from words. A list of suffixes was generated to remove superfluous word endings.

Of the 208 responses, 6 indicated “No” regarding consent for the collection and use of data as outlined in the privacy statement, as presented in Appendix A. Contemplate the subsequent two scenarios:

- The participants perused the privacy statement and voiced their objections.

- The participants ignore the question and offer a disorganized, negligent reply.

The participants who provided a negative response have previously addressed the subsequent primary, open, and semi-open questions. Ultimately, their response seems haphazard and negligent. Conversely, any participant who selects a negative response in the privacy statement permission will have their comments expunged in accordance with the GDPR and its rigorous regulations [29]. The total number of sample data, after eliminating the replies from this questionnaire, is 202. Furthermore, the dataset was devoid of null or missing values, as the questionnaire exclusively comprised obligatory questions. This technique obviates the necessity for preprocessing to ascertain the existence of null and missing data.

5. Lexicon Development and Preprocessing

Sentiment words, which are typically referred to as opinion terms, are the primary indicators of sentiments. People commonly use these phrases to express either positive or negative sentiments. For example, nice, fantastic, and spectacular express a positive sentiment, while poor, awful, and terrible denote a negative disposition. Sentiment lexicons and expressions are essential to sentiment analysis for evident reasons [34]. Words and phrases of this nature are collectively referred to as a sentiment lexicon (or opinion lexicon).

The questionnaire responses reveal the following four dictionaries:

- 1

- The overall significance of work.

- 2

- The working environment.

- 3

- The salary.

- 4

- The superiors.

The overall relevance of work arises from the semi-open question that prompts employees to enumerate three to five adjectives they identify with their employment. The work environment, salary, and superiors derive from the open-ended question that prompts employees to reflect on their overall job perception. The dictionaries include adjectives that may be absent from the questionnaire responses; however, they will prove beneficial for future research. The formation of each lexicon will be examined as follows:

- (1)

- The initial dictionary DoW characterizes work/job as a comprehensive entity. This dictionary was constructed in response to the inquiry, “What three to five adjectives come to mind when you think of your job”?” It is unnecessary to compose a list of nouns from the dictionary, as this semi-open question just pertains to adjectives directly associated with the occupation or job within its overall context. The sentiment analysis and score will be derived directly from the preprocessed list of adjectives. The preprocessing of the semi-question prior to the formation of this dictionary encompasses the regulations pertaining to the preprocessing approach outlined in Section 4.2. The assignment required manual intervention due to the algorithm’s inability to effectively eliminate many types of words, including nouns and verbs. This list, encompassing all responses for the semi-question, originally comprised 640 adjectives; however, following the previously indicated process, it currently has 536 adjectives. 102 adjectives that exhibit both positive and negative polarity are included in the DoW dictionary after the preprocessing.

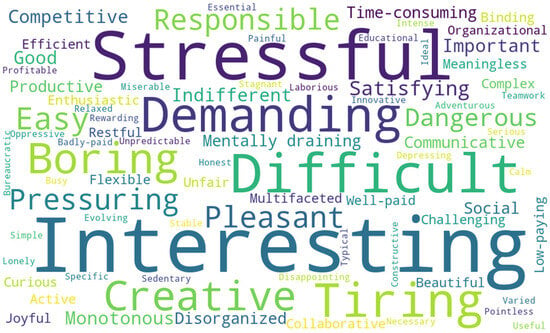

A word cloud depicting the most commonly utilized adjectives from participants’ responses in Figure 3 will yield significant insights into the significance and impact of each term [35]. A variety of terms were employed by participants to express their thoughts on their occupation. The existence of both positive and negative responses suggests that individuals possess differing perspectives, possibly attributable to their diverse work environments. The size of each word corresponds to its frequency of usage. A higher font size of a word indicates its heightened frequency of usage.

Figure 3.

A word cloud of the most frequently used adjectives from participants.

Table 2 presents the 10 most utilized words inside the DoW, including the respective frequency of each word and its sentiment score.

Table 2.

The 10 most utilized words and their respective frequencies (with and without suffixes).

The next step for the lexicon entails allocating sentimental values of positivity or negativity, spanning from +1.00 as the maximum to −1.00 as the minimum. There are two ways to execute this technique:

- Python encompasses libraries like VADER and TextBlob, which are dedicated to sentiment analysis and provide sentiment ratings for social texts, comments, and informal writings, albeit exclusively in the English language [36]. The Greek terms must be translated into English to execute this method in the Greek language. Thereafter, the program will yield sentiment scores.

- Manually, by inputting sentiment scores for each word in the dictionary, line by line.

The sentiment score for each adjective was assigned based on its meaning to evaluate the work/job as a whole entity. In this study, the sentiment scores were manually assigned to each dictionary.

- (2)

- The second dictionary, DoWE, pertains to the working environment. This dictionary was constructed in response to the inquiry, “How do you perceive your job in its entirety?” Adjectives that are relevant to the working environment, such as colleagues, work climate, and working facilities, are included in this dictionary. The preprocessing begins by consolidating all answers into a singular text, thereby improving efficiency in following procedures. The subsequent phase in preprocessing the open question involves following the guidelines of the preprocessing approach outlined in Section 4.2. The aforementioned preprocess is achieved by both tones and suffixes through the use of a manually generated list. The failure to remove the Greek stop words resulted in the compilation of a list of superfluous stop words. Upon eliminating these stop words from the text, 76 adjectives pertinent to the working environment were manually picked. The last phase was the manual computation of the sentiment score for each adjective, as illustrated in Table 3.

Table 3. A sample of DoWE dictionary.

Table 3. A sample of DoWE dictionary.

- (3)

- The third dictionary DoS pertains to salary. The foundation of this dictionary lies in the open question surrounding the development of the DoWE dictionary. In a manner similar to the aforementioned dictionary, the preprocess is implemented to derive 76 adjectives that are pertinent to salary. Following the establishment of the lexicon, each adjective was awarded an emotion score manually, as illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4. A sample of DoS dictionary.

Table 4. A sample of DoS dictionary.

- (4)

- The fourth dictionary, DoSP, denotes the superiors of each organization. 59 adjectives were manually identified to determine superiors, and a sentiment score was calculated following the preprocessing of the open question, which employed the aforementioned procedure, as illustrated in Table 5.

Table 5. A sample of DoSP dictionary.

Table 5. A sample of DoSP dictionary.

Subsequent to the compilation of the dictionaries, three noun lists derived from the DoWE, DoS, and DoSP will be amalgamated prior to conducting sentiment analysis. It is unnecessary to build a list associated with the DoW vocabulary, because the semi-question related to this dictionary only includes adjectives after preprocessing. Consequently, the generated lists are as follows and as represented in Table 6:

Table 6.

A sample of nouns from the three lists.

- The LoWE list comprises nouns that act as alternatives to the workplace.

- The LoS list contains nouns that serve as substitutes for remuneration.

- The LoSP list comprises nouns that function as substitutes for the superiors of each organization.

5.1. Sentiment Analysis

After looking at the demographic data, making sure the questionnaire follows GDPR rules, and preparing the necessary dictionaries and lists, the next step is to perform a sentiment analysis. This analysis has two phases:

- The initial phase entails evaluating the sentiments conveyed in the semi-question.

- The next phase examines the attitudes pertaining to the open question.

Following the sentiment analysis of the open and semi-open questions, there are anticipations for deriving valuable insights concerning employees’ feedback on their job happiness.

5.1.1. Sentiment Analysis of the Semi-Question

The initial step of sentiment analysis commences with the semi-question, which gives rise to the DoW dictionary. The semi-question necessitates specialized handling for preprocessing and sentiment analysis, given its status as a semi-question and its exclusive focus on adjectives. Consequently, the DoW vocabulary that developed includes adjectives generated from the semi-question. The sole distinction between the DoW4 list and the DoW dictionary is that the list encompasses the preprocessing detailed in the development and preprocessing sections, while the dictionary eliminates duplicate adjectives and insignificant non-adjective words, organizes them alphabetically, and incorporates sentiment scores for each entry. The dictionary contains 102 distinct adjectives, whereas the list comprises 536 adjectives.

The process begins with the computation of the aggregate quantity of positive, negative, and neutral adjectives used by employees to express their feelings about their work. Table 7 presents the total count of adjectives per sentiment category and each percentage.

where

- positive_count represents the sentiment value greater than zero,

- negative_count represents a sentiment value less than zero,

- neutral_count denotes the sentiment value as zero.

Table 7.

Total count of adjectives per sentiment category and each percentage.

Table 7.

Total count of adjectives per sentiment category and each percentage.

| Count | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Adjectives | 239 | 44.59 |

| Negative Adjectives | 297 | 55.41 |

| Neural Adjectives | 0 | 0 |

| Total Adjectives | 536 | 100 |

Table 7 delineates the list comprising 239 positive, 298 negative, and 0 neutral adjectives, culminating in a total of 537 words. The proportion of negative adjectives is 55.41%, but the proportion of positive adjectives is significantly lower at 44.59%, with no neutral adjectives present. The percentages suggest that employees have a negative attitude towards their work, although it is impossible to draw a definitive conclusion about the overall sentiment score and polarity across the entire list.

The subsequent step involves computing the average polarity and the cumulative sentiment score for the complete list. The application utilizes the DoW dictionary as a lexicon with polarity to identify an adjective from the DoW4 list by comparing it with the adjectives contained in the dictionary. If the list includes the adjective, the sentiment value adds to a score variable as per the calculation stated below.

where

- The sentiment_value represents the score assigned to each adjective within the DoW dictionary.

The score is divided by the number of sentiment-bearing words, which is 536, to determine the average polarity.

A minor dominance of negative adjectives over positive adjectives is indicated by the average polarity of −0.04. The difference between the number of positive and negative phrases is low (239 positive, 297 negative, and 0 neutral); nonetheless, the impact of negative words on sentiment is more pronounced, leading to a marginally negative average polarity. The value, being near zero (−0.04), indicates a predominantly neutral to slightly negative tone with a minor inclination toward negativity. This measurement elucidates the reason for the predominantly negative feeling.

The total sentiment score signifies the aggregate of all individual sentiment values for each adjective in the list. The outcome indicates a value of −19.53, showing an unbalanced overall sentiment toward the negative aspect of the text. The negative score indicates that negative adjectives surpass positive ones in their overall influence on sentiment. Despite the significant presence of positive words, the modest prevalence of negative words results in a negative total emotion score and a marginally negative average polarity. The absence of neutral terms signifies a heavy emphasis on polarized language.

5.1.2. Sentiment Analysis of the Open-Question

A preprocess for an open question is included in this analysis phase, which encompasses the working environment, salary, and superiors. This is based on the question that prompts employees to reflect on their overall perception of their job. In Section 4.2, ‘Preprocessing of the Textual Data’, the primary preprocessing methods addressed and implemented on this open question are discussed. Consequently, the preliminary phase of preprocessing entails purging the responses to open-ended questions. Tokenization, normalization, stemming, lemmatization, stopword removal, and noise removal are all components of text pre-processing techniques [37]. The process begins with removing tones, suffixes, stop words, and superfluous terms. These elements are systematically listed to facilitate cleansing the response.

A widely acknowledged method for assessing the significance of a word within a document is the term frequency-inverse document frequency, commonly referred to as TF-IDF [38]. The term frequency of a certain term (t) is determined by multiplying the frequency of the term’s occurrence in a document by the total word count of the document. IDF is utilized to evaluate the significance of a term:

where

(t) = log(N/DF)

- N represents the quantity of documents.

- DF represents the quantity of documents that include the term t.

The TfidfVectorizer and CountVectorizer automatically tokenize the cleaned text into individual words during processing. Consequently, tokenization is implemented during the preprocessing phase; however, the vectorizers execute it manually [39]. The TfidfVectorizer in scikit-learn defaults to converting all text to lowercase. This behavior guarantees that words are regarded uniformly irrespective of their casing, preventing the model from treating variations such as “Kλιμα” and “κλιμα” as distinct tokens.

The TF-IDF method is capable of capturing the overall importance of words across all responses by compacting these responses into a single text string, although they contain a limited number of words. Concise answers may lack sufficient context for TF-IDF to function effectively [40]. This method facilitates the derivation of more significant insights from phrase frequencies. The TF-IDF method was applied to the cleansed text both before and after the suffixes were removed. Variations exist in the TF-IDF scores and word counts before and after the elimination of suffixes, as shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

TF-IDF scores before and after removal of suffixes and removal of negations.

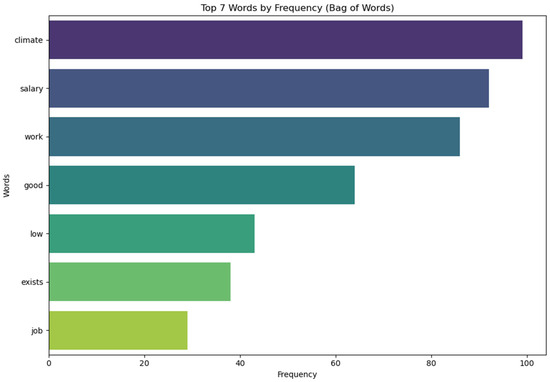

Terms such as not, but, and no are classified as negation words; they frequently appear in employee responses but do not enhance the semantic meaning of the text and diminish the significance of more substantive terms like climate, salary, and work, which convey the primary meaning of the text. Consequently, a list of negative terms was manually compiled and exclusively excluded for the TF-IDF approach, which was subsequently reapplied. Table 8 illustrates the results before and after the removal of suffixes and removal of negations. Moreover, the suffixes removal and the elimination of negation terms (substituting the word “ΔΕΝ”-“NOT” with “ΧAΜHΛOΣ”-“LOW”) altered the TF-IDF scores as anticipated. Figure 4 presents the seven most commonly occurring words in the text, without the negation words.

Figure 4.

Top seven words by frequency without negation words.

Following the TF-IDF approach, the sentiment analysis of employee replies commences. The open question encompasses three essential elements that enhance the total importance of employment: the work environment, salary, and leadership. The primary objective is to perform sentiment analysis for each of these three critical aspects individually.

The work environment substantially influences job satisfaction and is crucial for employees [26]. This phase constitutes the preliminary stage of the sentiment analysis procedure. Initially, as open question sentiment analysis excludes suffixes in responses, it is imperative to eliminate them, analogous to the procedures applied to the DoWE dictionary and the LoWE list. The analysis of sentiments in the workplace environment includes the following process:

- A function examines the words located two positions before and after the aspect under evaluation.

- If the term is an adjective that belongs to DoWE’s lexicon, it regains its polarity. Based on polarity, the system categorizes the value into one of three lists: positive_terms, negative_terms, or neutral_terms.

- When a negation term, such as “not,” is positioned two places before the aspect, the polarity of the following word is reversed and incorporated into the list of negative terms.

- The function also assesses the terms that are located up to two positions after the aspect, thereby repeating the polarity detection and list updating process.

- The final evaluation computes and presents the average of the polarities, resulting in the ultimate assessment of positive, negative, and neutral terms.

Table 9 displays the comprehensive outcomes of sentiment analysis within the workplace.

Table 9.

Results from sentiment analysis of the Working Environment.

The comprehensive assessment of the work environment is determined by dividing the aggregate score by the quantity of valid reviews.

where

- Valid Reviews is all non-invalid working-environment reviews.

The overall working environment evaluation score is 0.20, indicating a marginally positive sentiment, however nearly neutral. The evaluations are generally favorable toward the working environment; however, they are not predominantly positive.

As illustrated in the equation above, the total sentiment score is simply the sum of the evaluations. Across all evaluations, a score of 21.50 suggests a positive trend in the general perception of the work environment.

The aggregate of positive, negative, and neutral words constituted the overall word count. Sixty-five words (84%) are positive, suggesting that most reviewers employed positive sentiment to describe the employment environment. Despite comprising just eleven negative terms (14%), they nonetheless contribute to a nuanced or balanced perspective. Only one neutral word (0.01%) was discovered, suggesting that the preponderance of reviews displayed clear positive or negative tendencies. The notable proportion disparities between positive and negative words indicate that individuals employ positive terminology more often than negative language to critique the workplace, although negative words appear to possess a more unfavorable score.

Table 10 displays a selection of terms utilized to convey thoughts regarding the work environment and the associated categories.

Table 10.

Sample of words that were used and the categories that were included.

Individuals generally view the working environment favorably, but the presence of specific negative terms suggests that there may be areas that require refinement. The sentiment is predominantly neutral, with a slight inclination towards mild positivity.

The salary is the subsequent critical aspect for which sentiment analysis will offer valuable information. Performance-based compensation was identified as the foremost factor for employment motivation [5]. The salary aspect’s sentiment analysis preprocess entailed the development of a dictionary named DoS, which comprises adjectives with polarities, and a list named LoS, which contains aspects that substitute for the term “salary.” The preprocessing for the open question follows the same methodology for all aspects of sentiment analysis. The subsequent methods were employed for sentiment analysis:

- The first approach comprises a pristine text, free from suffixes, punctuation, and uppercase letters.

- The second approach consists of a clean text without suffixes and uppercase letters, although containing commas and periods.

The initial approach employed was identical to the previously utilized working environment element. Table 11 presents the comprehensive findings of the salary’ s sentiment analysis.

Table 11.

Results from sentiment analysis of the Salary.

The evaluation score of −0.15 signifies a predominantly unfavorable feeling concerning salary; however, it approaches neutrality, implying ambivalent views. A score of −18.72 highlights the dominant negative sentiment in all evaluations, with negative language exceeding positive terms.

Fifty-eight positive words (47%) indicate favorable references for compensation. A marginally elevated count of sixty-five negative terms (53%) indicates that unhappiness with compensation is somewhat more common. The text lacks neutral terminology, suggesting that most descriptive phrases distinctly express either a positive or negative polarity. Although certain individuals offer favorable comments, the prevailing opinion about compensation is predominantly negative. The marginally elevated count of negative terminology and the overall negative mood score indicate that apprehensions or discontent over compensation are widespread in the reviews.

An example of the words employed to convey sentiments regarding salaries and the percentages associated with each category is presented in Table 12.

Table 12.

A sample of words used to express sentiments about salary.

Individuals generally perceive the compensation aspect unfavorably, exhibiting a predominance of negative remarks over positive ones. Despite significant dissatisfaction regarding compensation, the overall mood score approaches neutrality, indicating that the attitude is not overtly negative. Affirmative language suggests optimistic perspectives [41]; nevertheless, concerns about compensation often surpass these sentiments. Notwithstanding the existence of negative emotions, the remarks predominantly reflect moderate dissatisfaction.

The second approach allows for the observation of how computer science manages punctuation and the identification of potential hurdles that may occur. A hurdle faced in the initial efforts of sentiment analysis was the recurrent concatenation of commas and periods with the word, leading in instances such as: Word, or Word. The algorithm failed to recognize the word due to the program’s inability to comprehend a familiar term; instead, it identified an unfamiliar phrase of the aforementioned sort. The technique entailed isolating the word from the punctuation prior to performing a sentiment analysis of the complete text.

To analyze the text and manage the commas and periods, a more intricate method employs two distinct functions:

- The initial function verifies the presence of a comma or period two positions prior to the designated facet, specifically salary, and modifies the evaluation procedure accordingly. It examines the words preceding the comma to determine their association with lists pertinent to the work environment (LoWE) or working conditions (LoSP). The function returns false if it identifies terms from these lists prior to a comma, suggesting that it should refrain from calculating polarization for the salary aspect. If the LoWE or LoSP lists produce no results, the function consults the DoS emotion dictionary for adjectives and integrates the corresponding polarity into the assessment list.

- The primary function evaluates salary polarization utilizing the supplied data. The function initiates by assessing the presence of a comma or period in either of the two positions preceding the fold. After identifying a party and leaving out any terms that could complicate the evaluation, like those about the workplace or management structure, the function goes on to check the words that come after the aspect. The function examines up to two words after the aspect for negations and subsequently assesses whether the subsequent word exists in the DoS dictionary. If the term exists in the DoS lexicon, its polarity is inverted. If the term is present in the DoS dictionary without negation, the primary function obtains its standard polarity value. Ultimately, upon identifying assessed terms, the system computes the mean polarization values from the primary function and presents the outcomes.

The obtained results roughly correspond with the preliminary sentiment analysis method, exhibiting a slight divergence in the overall wage evaluation, with a value of −0.13, in contrast to the first method’s −0.15 outcome.

Supervisors are the final critical aspect for which sentiment analysis will provide valuable insights. Employees’ job satisfaction can be substantially predicted by their regard for their superiors and the relationship between them [1]. To prepare for sentiment analysis, a dictionary called DoSP with polarity-containing adjectives and a list called LoSP with characteristics that substitute the word superior were created. The sentiment analysis procedure parallels that of the prior aspect, salary. Table 13 displays the overall results of the superior’s sentiment analysis.

Table 13.

Results from sentiment analysis of the Superiors.

The findings suggest that the text insufficiently emphasizes criticism of superiors, which is attributable to the restricted use of adjectives for this purpose. Moreover, an often articulated statement claims that, although the superiors comprehend the issues, their actions are repressive. The script’s failure to facilitate a sentiment analysis of this text arises from the adjective’s considerable distance from the aspect. Despite supervisors seemingly comprehending the employees’ issues, they persist in oppressive behavior, leading to a mixture of positive and negative attitudes.

Exhibiting a marginal positive inclination, the evaluation score of 0.000099 suggests an essentially neutral sentiment towards the subject matter. The total sentiment score of 0.02 reinforces the lack of significant emotional bias, suggesting that the reviews exhibit a balanced array of opinions. Eight positive words (61%) suggesting a somewhat positive tone. In contrast, five negative terms (39%) indicate a degree of unhappiness. The limited number of positive and negative terms indicates that the conveyed opinions lack considerable polarization. Furthermore, the lack of neutral wording suggests that the descriptions often carry distinct positive or negative meanings. The rating is predominantly positive, although the attitude is practically neutral, indicating that the reviews do not express any significant sentiment, whether positive or negative. The outcome indicates a general equilibrium in perspectives, with a slight predisposition towards optimism. A sample of terms that are used to express views about superiors, as well as the corresponding percentages for each category, is provided in Table 14.

Table 14.

Sample of adjectives regarding superiors.

6. Discussion and Decision-Making

Employees’ responses to the questionnaire provide useful information regarding their salary, work environment and relationships with their superiors. Success in job satisfaction and the enhancement of employee emotions are facilitated by these three components. The semi-open question delivers a comprehensive overview of the work, whereas the open question yields critical insights into the three most salient aspects. The multiple-choice question offers the chance to pinpoint areas of employees’ employment that could be enhanced, depending on deficiencies in their role, so increasing their satisfaction. Begin by delving into each component and conclude with a comprehensive review of the job with the goal of achieving business success as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

From job satisfaction to Business success.

6.1. Working Environment

Attaining organizational objectives necessitates that corporate systems foster a stable and transparent work environment [42]. The organizational environment and workplace social relationships are important determinants of employee contentment or dissatisfaction. Due to heightened rivalry and a dynamic, tough business environment, businesses must ensure that their employees operate in a supportive and amicable environment to reach their full potential [26]. Managers aim to foster satisfied employees who feel at ease in their workplace; they like to collaborate with individuals who maintain a positive outlook on their responsibilities. Employees with elevated job satisfaction typically exhibit a profound appreciation for their work; they perceive fairness within their workplaces and recognize that their roles offer advantageous attributes such as diversity, challenge, competitive compensation, stability, autonomy, and amiable colleagues, among others [2]. The term “κλίμα”—“climate” was the most frequently used word in the sentiment analysis of employees, with 92 occurrences in employee responses, resulting in a TF-IDF score of 0.496. Subsequent to the removal of suffixes, the TF-IDF score decreased to 0.425, with the term appearing 99 times, diminished to the second position after the word “μισθός”—“salary”. Both above situations illustrate that employees regard the work climate, indicative of the working environment, as the paramount factor—or second only to compensation in the instance of suffix removal—in assessing their job happiness. Furthermore, the answer in the multiple-choice question for a better working environment accounts for 22.6% of total responses, indicating a substantial proportion of employees that require a more conducive work setting than their current one.

The results of the sentiment analysis indicate that employees predominantly have a favorable impression of their working conditions. The small amount of negative feedback indicates that certain aspects require focus to improve employee satisfaction further. Preserving and improving the work environment is essential since it fosters a constructive culture for employees. Employees are significantly motivated by a workplace that fosters a sense of security, comfort, and encouragement. Conversely, detrimental working conditions induce worry regarding employees’ physical health [5]. The degree of comfort in the work environment is directly proportional to the increase in employee productivity. The decision-making department should focus on the minor percentage of negative remarks and examine the underlying causes of employees’ adverse remarks regarding their work environment. Factors influencing employees’ loyalty, productivity, and efficiency include working hours, employment safety and security, connections with colleagues, and esteem requirements [26].

6.2. Salary