Abstract

A detailed understanding of interface degradation in humid environments is essential for improving the reliability of adhesive bonding technologies. Water absorption within the adhesive layer significantly affects joint strength, a factor considered to be long-term degradation. However, even if water does not approach the interface from the inside due to absorption, it can reach the interface from the outside through the crack tip and instantaneously affect the fracture behavior of the interface, highlighting the need to investigate short-term degradation mechanisms. In this study, the effect of water at the aluminum/epoxy resin interface on crack propagation was quantitatively evaluated by measuring the mode I energy release rate through double cantilever beam (DCB) tests. By changing the surface condition of the adherend, interfacial and cohesive failures were achieved, and DCB tests were conducted in air and underwater conditions to compare the effect of water on the fracture energy. Results showed that the interfacial fracture energy decreased by more than 50% when the crack propagated in water, but no significant reduction was observed in the cohesive fracture energy. The decrease in interfacial fracture energy in the presence of water indicates the immediate disruption of chemical bonding.

1. Introduction

The durability of adhesive joints has become a critical concern as adhesive bonding technologies continue to advance [1,2,3]. As a fundamental premise, fracture at the interface between the adhesive and adherend, known as adhesive failure (AF), must be prevented through proper surface preparation of the substrate. For interfaces between aluminum alloys and epoxy adhesives, surface roughness influences the wettability of the substrate, thereby promoting cohesive failure (CF) [4]. Wet-chemical etching and laser processing can create complicated 3D structures on surfaces to increase the anchoring effect; therefore, they are widely recognized as effective surface treatment methods for aluminum alloys. However, even after appropriate surface treatment, the presence of water at the interface can, in some cases, result in AF [5]. This is because water reduces the interfacial fracture energy to a level below the cohesive fracture energy, thereby facilitating crack propagation along the interface. A decrease in fracture toughness due to moisture absorption has also been reported in laminated composites, where the fiber/epoxy interface is degraded by moisture [6]. Therefore, elucidating the effect of interfacial water on bonding performance is of great importance.

Moisture penetration into the adhesive layer is widely recognized as a major factor in the degradation of adhesive joints [7]. This process is typically described by Fickian diffusion [8,9] and has been confirmed through direct observation [10,11]. The measured diffusion coefficient was slightly larger for the adhesive layer than for the bulk [9], suggesting that moisture penetration near the interface proceeds more quickly [12]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that absorbed moisture reduces the strength and fracture toughness of adhesive joints under conditions such as immersion [13,14,15,16], open-faced exposure [5,17], and cyclic absorption–desorption [18]. In contrast, the fracture toughness of the epoxy resin itself is not significantly affected by moisture [19] and, in some cases, even increases due to enhanced ductility associated with increased epoxy chain mobility [20,21], indicating that interfacial degradation is the primary cause.

Water absorption is generally viewed as a long-term degradation process because it takes weeks or even months for water to diffuse into the adhesive layer. A very different phenomenon has also been reported: rapid crack propagation triggered by a single water drop at the crack tip [22]. This is because water molecules can immediately break chemical bonds at the interface. Compared with the internal process of moisture absorption, the external approach allows water molecules to reach the interface much more rapidly and initiate chemical bond degradation. When a bonded structure is exposed to rain, condensation, or submerged environments, water can readily reach the crack front of the adhesive layer. Short-term effects within a few seconds arising from water at the crack front, therefore, also warrant attention. However, as no direct evidence remains on the fractured surfaces, the disruption of chemical bonds cannot be identified through post-test surface analysis. Therefore, indirect evaluation, such as changes in fracture behavior, is essential.

Adhesion at the aluminum/epoxy resin interface depends on physical, mechanical, and chemical bonding [23]. Focusing on chemical bonds in particular, hydroxyl groups on the aluminum surface and hydroxyl groups on the epoxy resin form hydrogen bonds [24], and a significant linear relationship was found between the amount of hydroxyl groups on the aluminum surface and peel strength [25]. However, molecular simulations demonstrated hydrogen bond disruption under water immersion [26,27,28]. Therefore, the chemical bonding is considered highly susceptible to water; a significant impact is expected on the aluminum/epoxy resin interface by localized water exposure. However, few quantitative studies have experimentally evaluated the influence of water presence at the crack front on interfacial crack propagation.

The double cantilever beam (DCB) test has been widely employed to evaluate the fracture energy of adhesively bonded joints. The effects of test speed [29,30,31], fatigue [32,33,34], and temperature variations [35,36,37] have been extensively investigated, for example. Therefore, the DCB test is well suited for the quantitative evaluation of adhesive bonding performance under the influence of water.

In general, various additives are incorporated into base resins to enhance their overall performance. From the viewpoint of fracture behavior, such additives promote stable crack propagation and increase fracture toughness. Conversely, they complicate the analysis of fracture mechanisms and make it difficult to identify the factors that actually govern interfacial bonding. Therefore, in this study, two adhesives, a pure epoxy resin and a commercially available adhesive, were compared. The pure epoxy resin was selected to isolate the effect of the resin itself, whereas the commercially available adhesive was selected to evaluate its overall performance as a typical adhesive containing additive.

In this study, DCB tests were conducted on two epoxy resin-based adhesives under both air and underwater conditions to investigate the effect of water on the interface between aluminum alloy and epoxy adhesive. By inducing both adhesive and cohesive failures, the effects of water were examined through analysis of the mode I energy release rate and fracture surface observations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. DCB Test Specimen

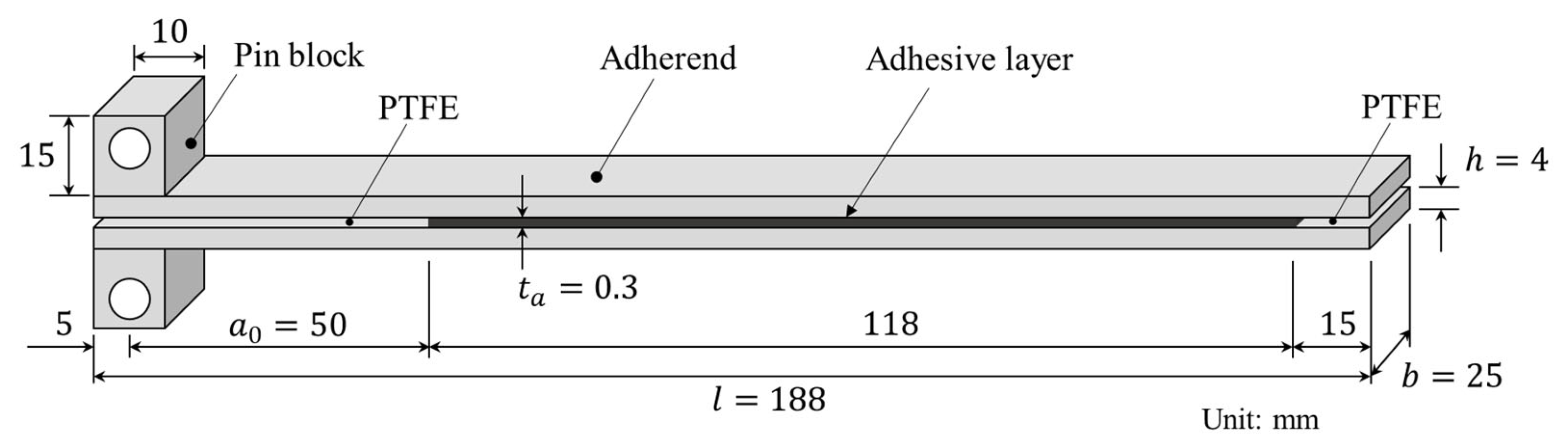

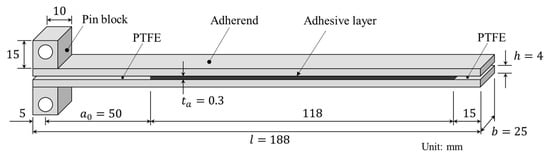

DCB test specimens were prepared by bonding two aluminum alloy plates with adhesive. An Al-Mg-Si alloy, A6061-T6, was selected as the substrate because of its high yield stress and excellent corrosion resistance. A schematic of the DCB test specimen and its dimensions are shown in Figure 1. The specimen width () was selected with reference to ASTM D3433-99. The adherend thickness () was chosen to be sufficient to prevent plastic deformation. The adherend length () and the initial crack length () were selected to enable accurate measurement of the energy release rate during crack propagation.

Figure 1.

Geometry of a DCB specimen.

2.2. Surface Preparation

Surface condition plays an important role in the fracture behavior of adhesive joints. The main objective of this study is to investigate the effect of water on the interfacial fracture behavior between aluminum and epoxy resin. To intentionally induce adhesive failure (AF), an as-received condition (acetone wiping only) was selected as the first surface condition. Conversely, a laser-treated surface was prepared as the second surface condition to promote cohesive failure (CF), enabling direct comparison between the two cases.

Laser processing was carried out using a laser marking device (LM110F, SMART DIYs, Yamanashi, Japan). The laser was applied along the longitudinal direction of the substrate, covering the full width, with a line spacing of 50 µm. Since the purpose of the laser treatment was to promote CF, the processing parameters were selected to sufficiently roughen the surface. Parameter values of laser processing is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Laser processing parameters.

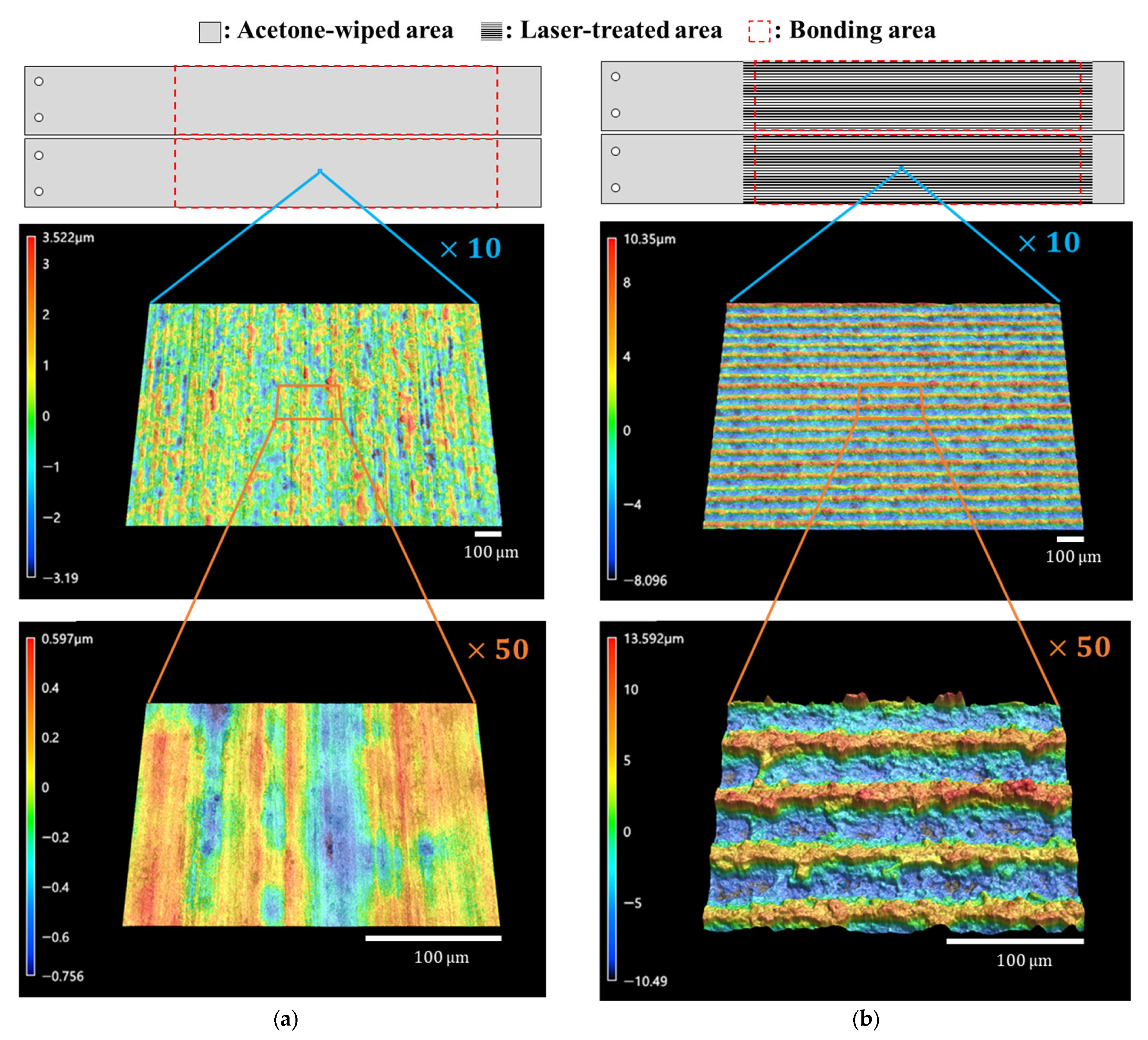

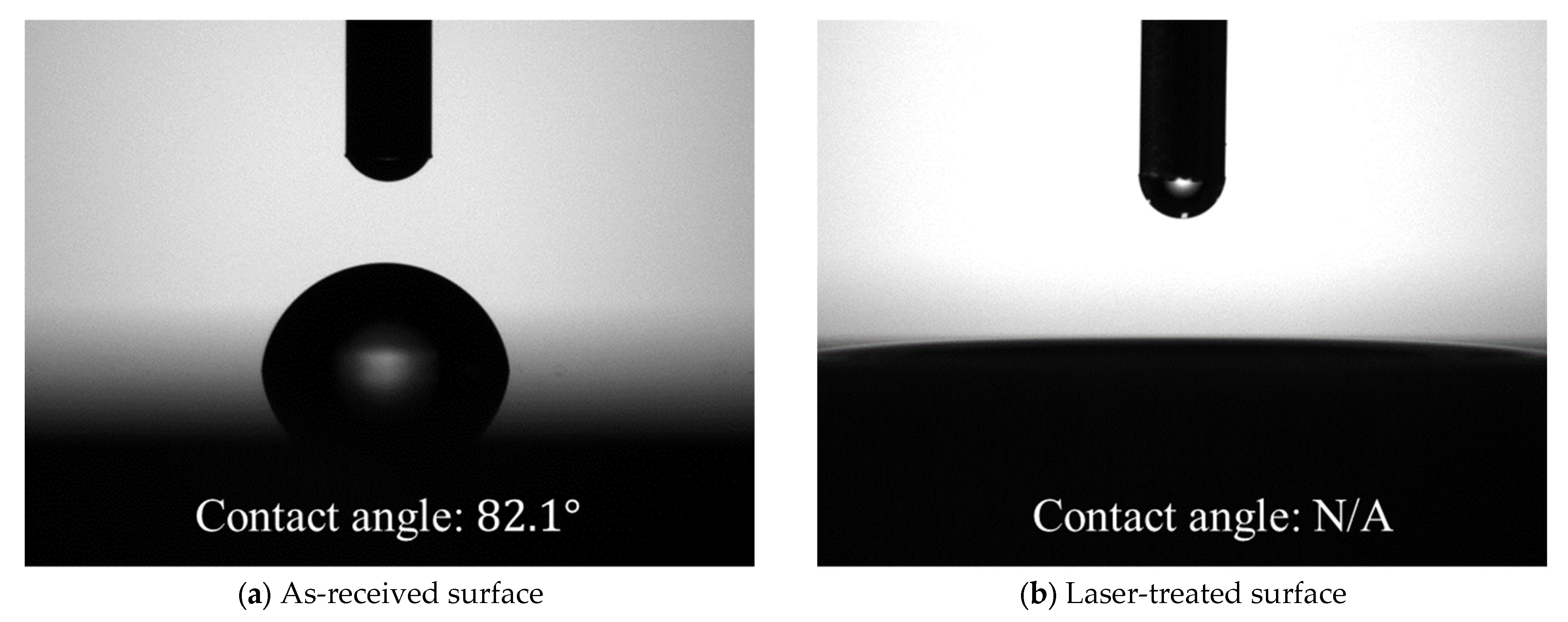

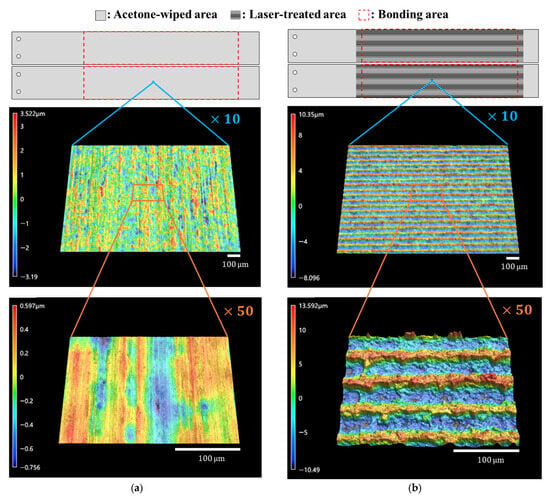

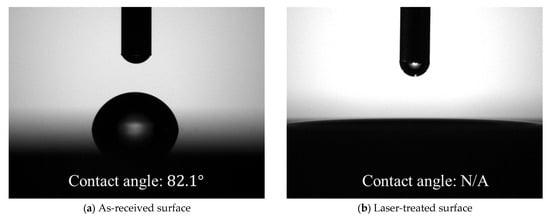

Surface analysis of substrates before bonding was carried out with a laser scanning microscope (VK-X3000, Keyence Co., Osaka, Japan) and a contact angle meter (DMo-602, Kyowa Interface Science Co., Ltd., Saitama, Japan). Surface profiles were shown in Figure 2. Surface roughness parameter values calculated using images at ×50 magnification are listed in Table 2. The as-received surface had a surface roughness of the submicron order, but after the laser treatment, the surface area increased by approximately double, and the arithmetic mean roughness also increased by one order of magnitude. The contact angle of purified water was approximately 82 degrees on the as-received surface but was too low to be detected on the laser-treated surface, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustrations and microscope images of the surfaces. (a) As-received surface; (b) laser-treated surface.

Table 2.

Surface roughness measured by laser scanning microscopy.

Figure 3.

Contact angle measurements of (a) as-received and (b) laser-treated surfaces.

2.3. Adhesives

Two types of epoxy-based adhesives were employed in this study. The first adhesive consisted of bisphenol A epoxy resin (JER-828, Mitsubishi Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan) as the base resin and poly (propylene glycol) bis (2-aminopropyl ether) with an average molecular weight of 230 g/mol (Sigma-Aldrich 406651, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) as the curing agent. The components were mixed at a weight ratio of 76:24 using a vacuum degassing and stirring device (ARV-310P, THINKY Co., Tokyo, Japan), applied to the substrates, cured at 70 °C for 12 h, and subsequently post-cured at 110 °C for 4.5 h. This adhesive is hereafter referred to as epoxy resin (ER). The mixing ratio of the base resin and hardener was determined based on their epoxy equivalent and amine values. The curing temperature and time were set to ensure complete curing, as confirmed by the disappearance of the exothermic peak in the Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) curve. The second adhesive was a commercial epoxy-based structural adhesive (SW 2214, 3M Co., St. Paul, MN, USA), which was cured at 120 °C for 40 min and post-cured at 160 °C for 1 h. This adhesive is hereafter referred to as structural adhesive (SA). Both adhesives exhibited nearly elasto-plastic stress–strain behavior, with typical material parameters obtained from tensile tests using dog-bone specimens (JIS K6251-6) [38], as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Material properties of two adhesives obtained from tensile tests.

2.4. Specimen Manufacturing

First, the lower adherend is placed in a special jig. Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) sheets are then placed on both sides of it, adhesive is applied, and another adherend is placed on top. PTFE sheets with a thickness of 0.3 mm are inserted at both the front and back of the specimen to control the adhesive layer thickness () and to introduce the initial crack. The special jig is used to control the position of the adherends. The test specimen, including the jig, is placed in an electric furnace for curing. After curing, the pin blocks are fixed with screws. The adherends have screw holes at predetermined positions, and the blocks also have counterbore holes at corresponding positions.

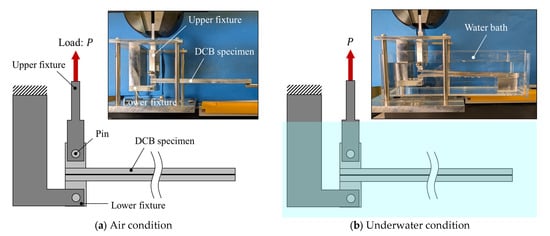

2.5. DCB Test Method

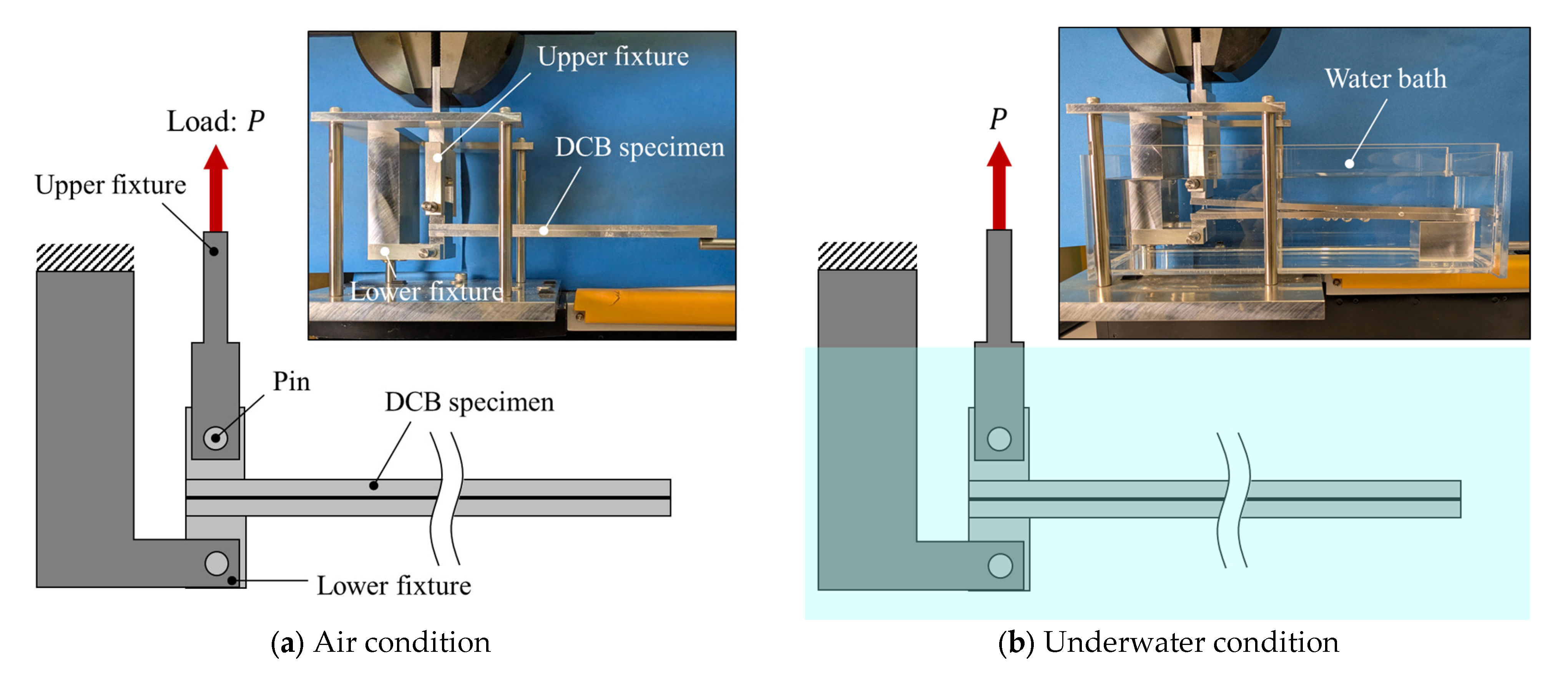

DCB tests were performed using a universal testing machine (STB-1225S, A&D Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at a crosshead speed of 5 mm/min, as shown in Figure 4. Tests were conducted under two environments: in air and underwater. For the underwater tests, a tank filled with purified water was used to ensure that the crack tip remained fully submerged throughout testing (see Figure 4b). Commercially available high-purity purified water, produced by an ultrapure water production system (RO membrane + ion exchange + UF membrane) and sterilized using a UV sterilization system, was employed. For the underwater tests, loading was initiated immediately after the specimen was placed in the loading fixture to avoid water absorption into the adhesive. All tests were carried out at room temperature (24 ± 2 °C).

Figure 4.

Schematic illustrations and photographs of the testing fixture for experiments conducted in (a) air and (b) water.

According to ISO and ASTM standards [39,40], three parameters are required to calculate the energy release rate in DCB tests: the applied load, the opening displacement, and the crack length [39,40]. However, direct optical measurement of crack length is often inaccurate; therefore, several alternative techniques for identifying the crack front have been proposed [41,42,43]. On the other hand, many studies have demonstrated that direct crack length measurement is unnecessary when using a compliance-based approach, since the crack length can be estimated from the compliance [44,45].

In the simplest form, the crack length can be expressed as:

where compliance is defined by with being Young’s modulus, the second moment of area, the applied load, the opening displacement, and the spring constant of the test system including fixture.

Although Equation (1) is derived from simple beam theory, it has been shown to yield reasonably good agreement with the effective crack length that accounts for correction factors such as the process zone and root rotation [30]. Accordingly, the mode I energy release rate was calculated as:

where is the specimen width. was measured by setting a block with holes instead of the DCB specimen and obtaining the load–displacement curves.

3. Results and Discussion

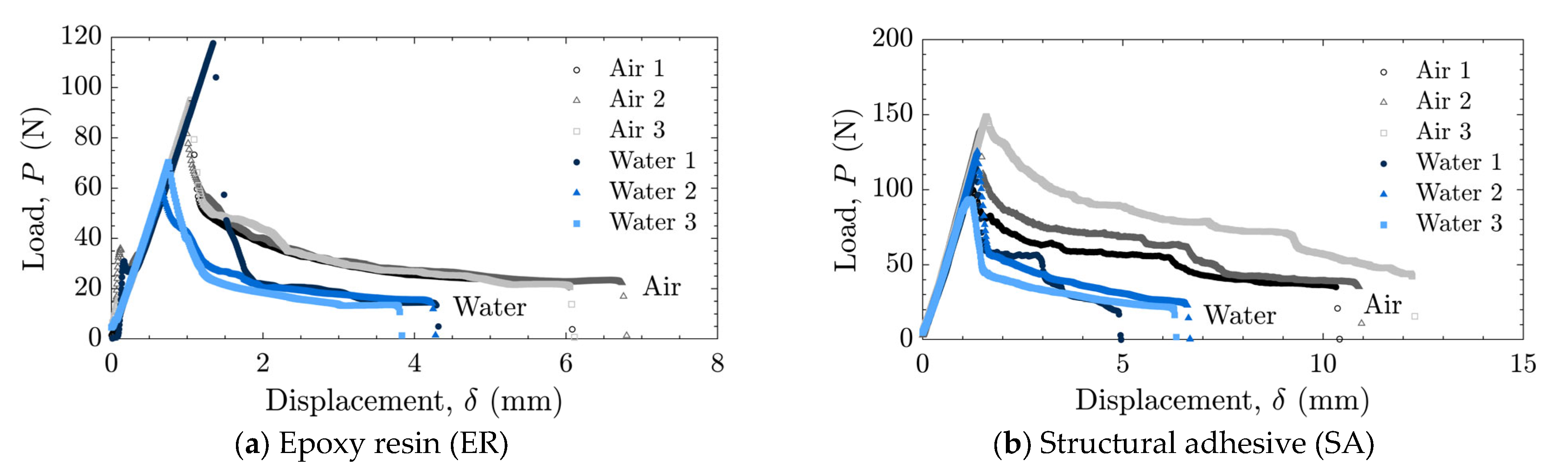

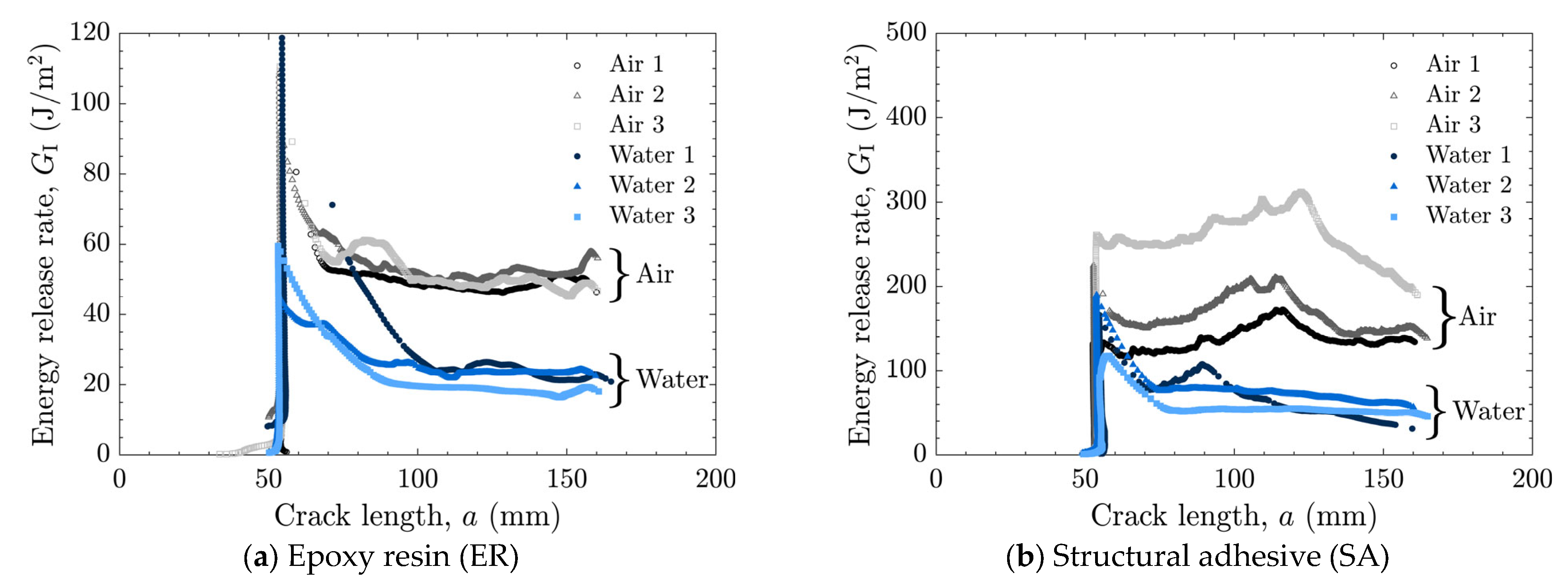

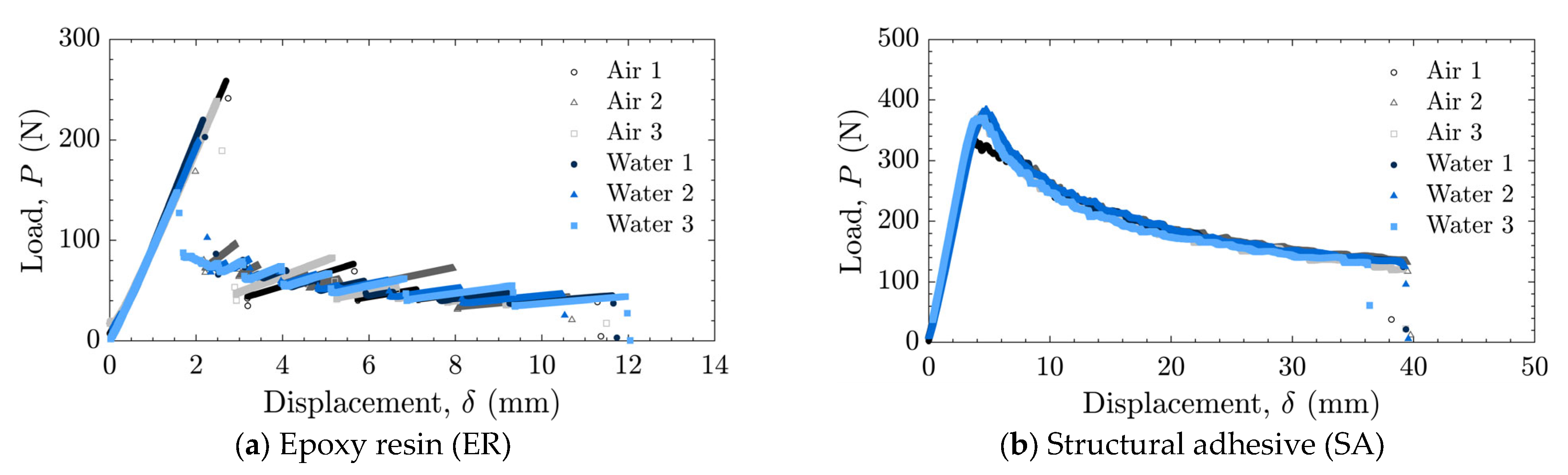

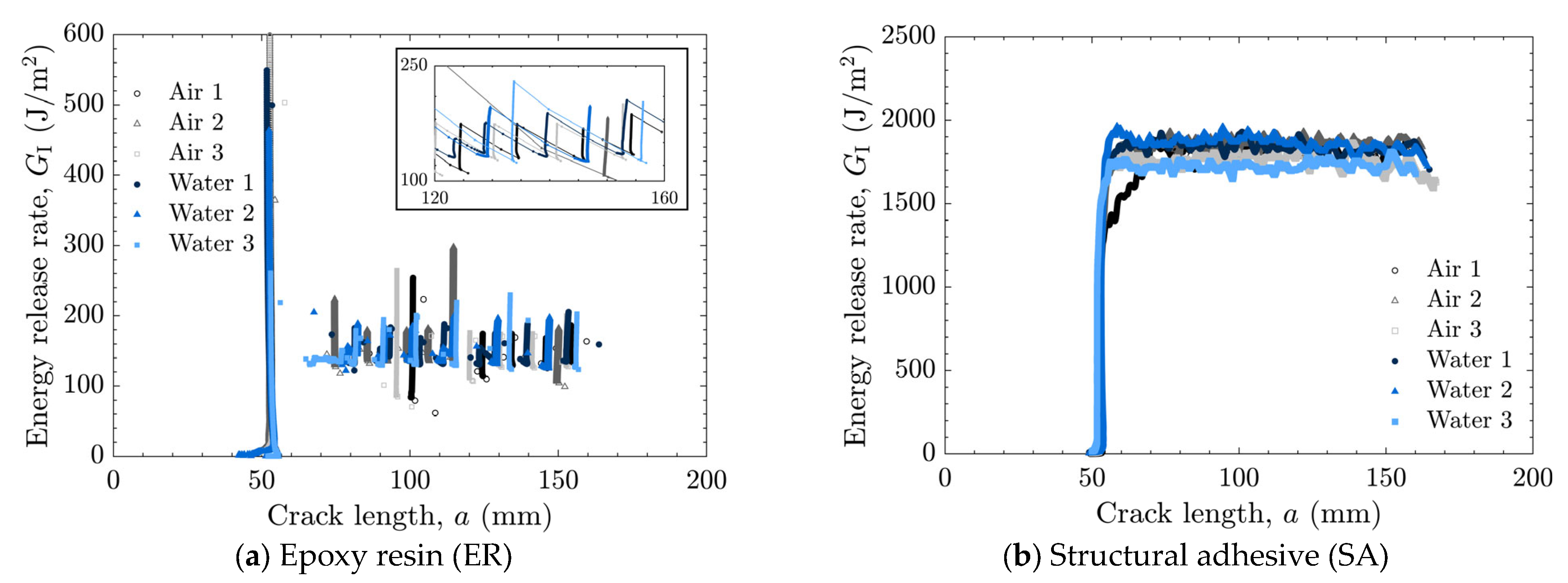

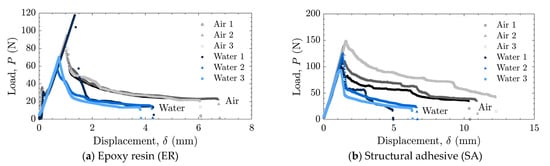

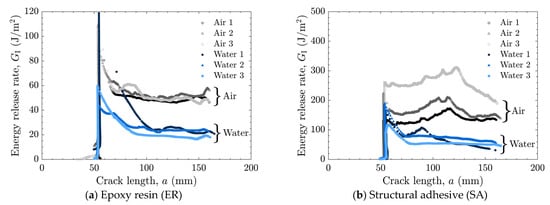

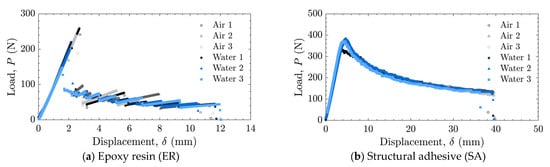

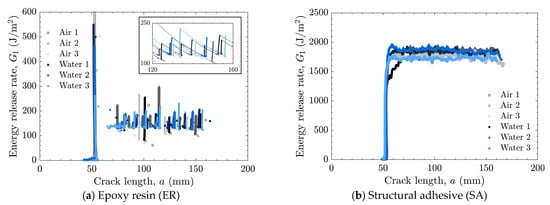

The load–displacement relationships and energy release rates obtained from the DCB tests are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6 for the as-received specimens and in Figure 7 and Figure 8 for the laser-treated specimens. For the laser-treated ER specimens, stick-slip behavior accompanied by CF was observed, as shown in Figure 7a and Figure 8a, whereas stable crack propagation was observed in the other cases.

Figure 5.

Load–displacement relationships for as-received specimens tested in air and water using (a) epoxy resin (ER) and (b) structural adhesive (SA).

Figure 6.

Energy release rate as a function of crack length for as-received specimens tested in air and water using (a) epoxy resin (ER) and (b) structural adhesive (SA).

Figure 7.

Load–displacement relationships for laser-treated specimens tested in air and water using (a) epoxy resin (ER) and (b) structural adhesive (SA).

Figure 8.

Energy release rate as a function of crack length for laser-treated specimens tested in air and water using (a) epoxy resin (ER) with enlarged view and (b) structural adhesive (SA).

In many cases, a high peak in the energy release rate was observed at the initial stage, followed by a transition to a nearly constant level as the crack length increased, as shown in Figure 6a,b and Figure 8a. This behavior can be attributed to the absence of sharp cracks formed during the manufacturing process; consequently, a relatively large amount of energy was required to propagate the initially obtuse cracks. Therefore, the initial peak values were excluded when calculating the average energy release rate.

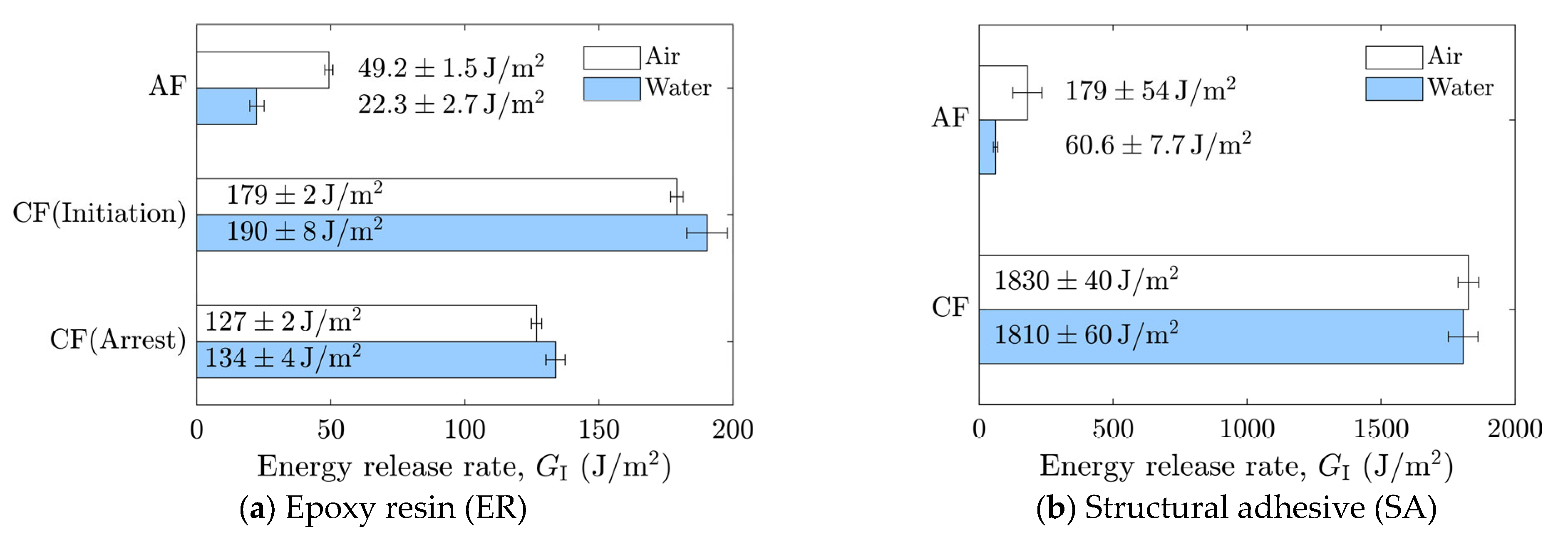

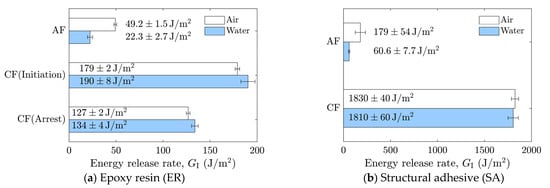

The averaged results are summarized in Figure 9. In cases where stick-slip crack propagation was observed, the mean values at the crack initiation points, i.e., the mean values of the local maxima of the energy release rate, were calculated as the critical energy release rate, and the arrest points, i.e., the local minima, as the arrest energy release rate. Overall, a decrease in the energy release rate in water was observed only in cases of AF. In the case of as-received specimens with SA, significant scatter was observed in air, which will be discussed later based on fractured surface observations.

Figure 9.

Average energy release rates corresponding to adhesion failure (AF) and cohesive failure (CF) in air and water for (a) epoxy resin (ER) and (b) structural adhesive (SA).

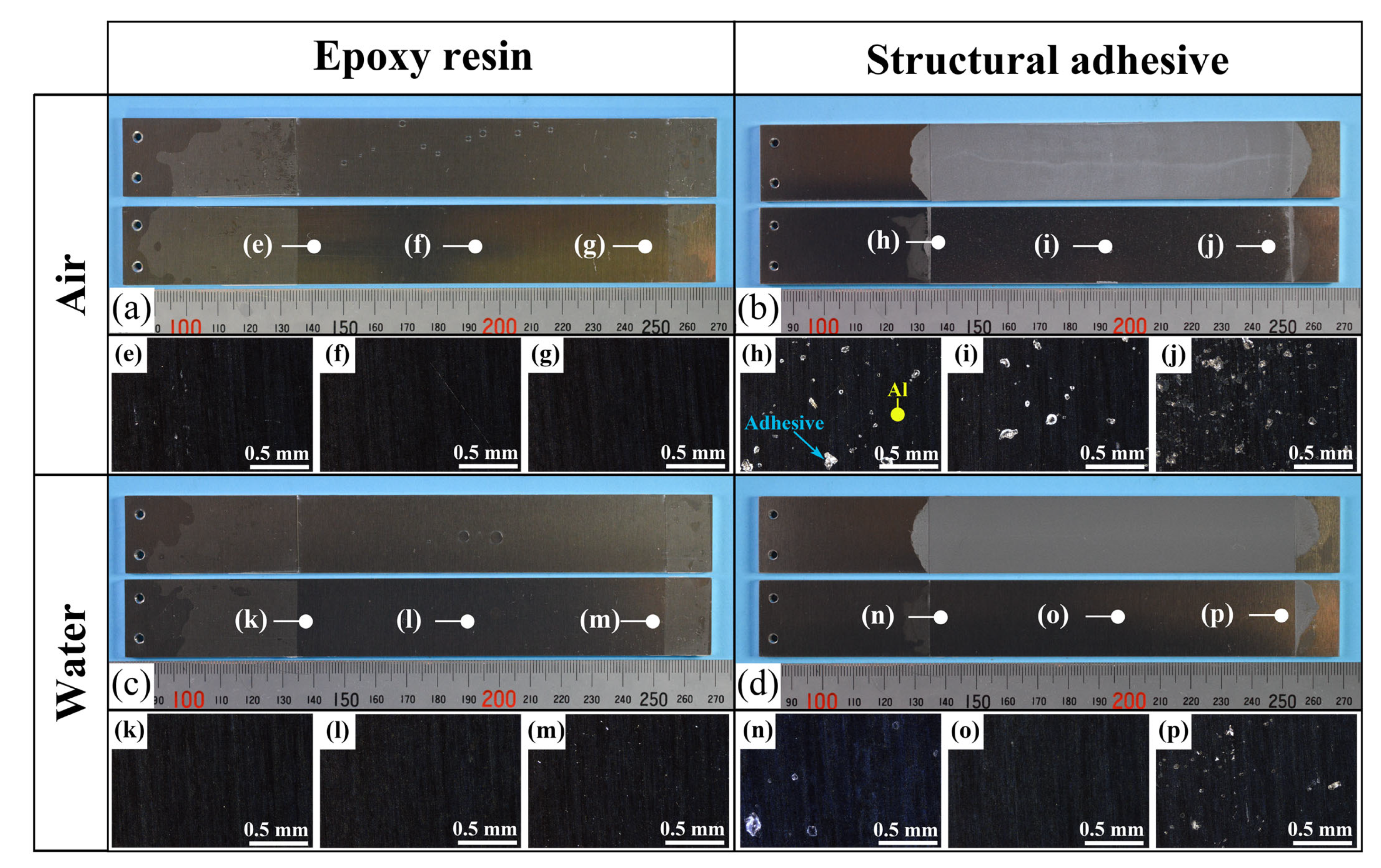

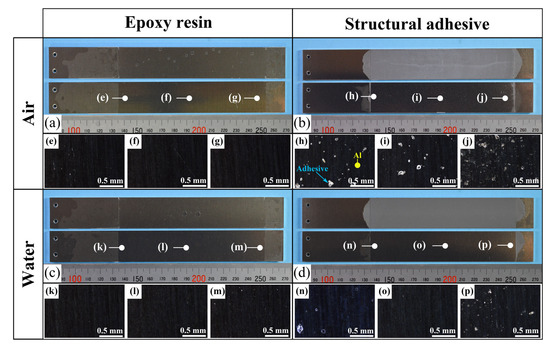

A comparison of the energy release rates of the as-received specimen with ER and SR revealed that the presence of water at the crack front reduced the energy release rate in both materials. Because the as-received specimens were designed to induce AF, detailed observations of the fractured surfaces were performed. Fractured surfaces are shown in Figure 10a–d, and detailed observations at three locations per specimen were made using a polarizing microscope (BX53P, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), as shown in Figure 10e–p. In the microscope images, dark regions correspond to the aluminum substrate surface, while bright regions correspond to the adhesive. These observations confirmed that the dominant failure mode was adhesive failure (AF), which is considered the primary reason for the reduced energy release rate in water. As shown in Figure 10h–j, partial cohesive failure (CF) was occasionally observed for SA in air, whereas almost no residue was found for the other cases. This partial CF occurs randomly, which may account for the large scatter in the case of as-received specimens with SA.

Figure 10.

(a–d) Photographs of the fracture surfaces for each combination of adhesive type and air/water condition in the as-received specimens; (e–p) polarized light microscope images corresponding to each location.

For both adhesives, the fracture energy was lower in water than in air, decreasing by approximately 25 J/m2 for ER and 120 J/m2 for SA, corresponding to reductions of 55% and 66%, respectively. The energy release rate of interfaces reflects not only the work of adhesion but also the energy dissipation around the crack front, and it is well established that the energy release rate is approximately proportional to the work of adhesion [46,47].

Similarly, when the aluminum/epoxy interface is invaded by water and the interfacial interactions are weakened, not only is the interfacial energy directly reduced, but other energy dissipation mechanisms are also affected. Therefore, the changes in fracture behavior should be discussed in terms of relative variations rather than absolute values.

The roughly 50% reduction observed under wet conditions indicates a pronounced effect of water at the crack tip during interfacial fracture. This decrease in interfacial fracture energy is attributed to the disruption of hydrogen bonds between the aluminum substrate and the adhesive [22]. Hydrogen bonds between aluminum oxide and epoxy contribute significantly to bond strength, and the presence of water at the crack front can break these bonds, thereby reducing the energy release rate. Akaike et al. [23] compared the interfacial fracture energy of the aluminum/epoxy resin interface with and without mechanical anchoring effects. On extremely flat surfaces, where only physical and chemical interactions existed, the fracture energy was 3.8 ± 1.5 J/m2, whereas it was 21.1 ± 5.8 J/m2 for as-received surfaces with additional mechanical interlocking. Although the types of hardener in the ER and aluminum alloy used in their study differed from those in the present work, the magnitude of the measured fracture energy was similar, providing valuable insight into the chemical and mechanical contributions to interfacial strength. The mechanical contribution of the as-received surface increased the fracture energy by approximately a factor of five. However, this result does not necessarily imply that chemical bonds account for only 20% of the total fracture energy, as synergistic effects between chemical and mechanical bonding may enhance the overall contribution. Indeed, the present results suggest that chemical bonding, both direct and indirect, contributes roughly half of the total fracture energy in the as-received specimens. The DCB tests conducted under water demonstrated the capability of this method to reveal the chemical contribution to interfacial fracture energy and confirmed that the loss of chemical bonds leads to a significant decrease in interfacial toughness. In addition, these results directly indicate only a decrease in the energy release rate; the influence of chemical bonding is discussed only indirectly, and should therefore be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, chemical bonding at the aluminum/epoxy interface involves not only hydrogen bonding but also other types of interactions [23]. Consequently, further investigation is required to enable a more in-depth discussion.

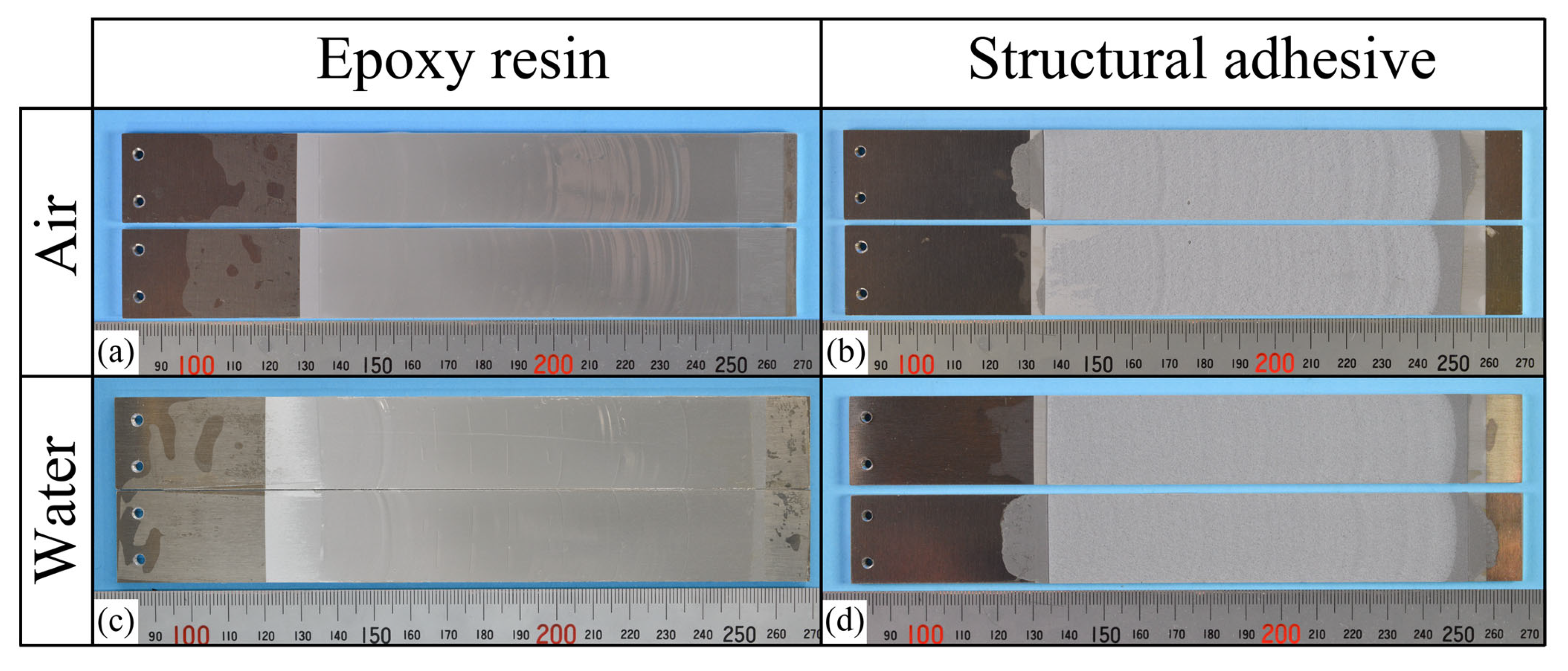

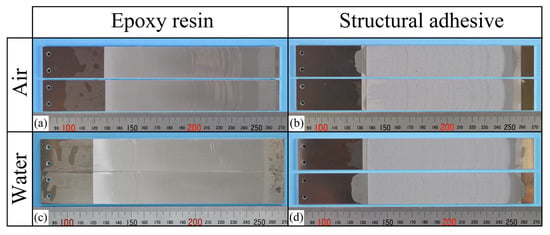

In contrast, all laser-treated specimens exhibited CF, as shown in Figure 11. The cohesive fracture energy was much higher than the interfacial fracture energy of the as-received specimens, as can be seen in Figure 9, and the presence of water at the crack tip did not reduce the fracture energy. In the case of ER, stick-slip behavior was observed; however, each step was small because the difference between the energy release rate for crack initiation and that for crack arrest was small. The absence of additives in ER may suppress the formation of microcracks and voids at the crack tip, which could contribute to unstable crack propagation.

Figure 11.

(a–d) Photographs of the fracture surfaces for each combination of adhesive type and air/water condition in the laser-treated specimens.

4. Conclusions

This study conducted double cantilever beam (DCB) tests on two epoxy resin-based adhesives under both air and underwater conditions to quantitatively evaluate the effect of water on the energy release rate. Unlike absorbed moisture, which causes long-term degradation, water reaching the crack front from the external environment can immediately influence fracture energy, particularly when crack propagation occurs along the interface. Aluminum substrates with different surface conditions were prepared to generate either interfacial or cohesive fractures.

The results showed that, in the case of adhesive failure, the interfacial energy release rate decreased by more than 50% when cracks propagated underwater compared with in air, whereas cohesive failure exhibited no significant change even in water. These findings, together with insights from previous studies, indicate that the reduction in interfacial fracture energy in the presence of water is primarily attributable to the disruption of hydrogen bonding at the aluminum/epoxy resin interface. Conversely, the degree of reduction reflects both the direct and indirect contributions of chemical bonding, making the reduction ratio a more accurate indicator of the synergistic effects than the absolute value.

In the short term, water affects the joint externally at the crack front. Over longer timescales, by contrast, as water gradually penetrates the adhesive layer, it can also attack the interface internally, although this has not yet been explicitly investigated. Therefore, understanding the role of chemical bonds in determining overall fracture energy is essential for improving the durability of adhesive joints in both the short and long term. Because the present results provide only indirect evidence of chemical bond degradation, further investigation is required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms in greater detail. However, it is highly recommended that designs do not rely solely on chemical bonding but instead enhance mechanical interlocking at the interface. A deeper understanding of water–interface interactions will support the development of more reliable and durable adhesive joints for applications in humid or submerged environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S.; methodology, A.S. and Y.S.; validation, K.S.; formal analysis, A.S. and T.T.; investigation, A.S. and T.T.; resources, Y.S.; data curation, Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, K.S., C.S. and Y.S.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, Y.S.; project administration, Y.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI, grant number JP25K07496.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DCB | Double cantilever beam |

| AF | Adhesive failure |

| CF | Cohesive failure |

| ER | Epoxy resin |

| SA | Structural adhesive |

References

- Viana, G.; Costa, M.; Banea, M.D.; da Silva, L.F.M. A review on the temperature and moisture degradation of adhesive joints. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2017, 231, 488–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualberto, H.R.; Amorim, F.C.; Costa, H.R.M. A review of the relationship between design factors and environmental agents regarding adhesive bonded joints. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2021, 43, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, C.S.P.; Marques, E.A.S.; Carbas, R.J.C.; Ueffing, C.; Weißgraeber, P.; da Silva, L.F.M. Review on the effect of moisture and contamination on the interfacial properties of adhesive joints. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2021, 235, 527–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Hu, N.; Zhang, D.; Da, Z.; Shu, L.; Li, Z.; Cang, X. Study on the interface and failure characteristics of joints between epoxy adhesive and duralumin alloy. Sci. Prog. 2025, 108, 00368504251348966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houjou, K.; Sekiguchi, Y.; Shimamoto, K.; Akiyama, H.; Sato, C. Energy release rate and crack propagation rate behaviour of moisture-deteriorated epoxy adhesives through the double cantilever beam method. J. Adhes. 2023, 99, 1016–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Khan, R.; Khan, N.; Aamir, M.; Pimenov, D.Y.; Giasin, K. Effect of seawater ageing on fracture toughness of stitched glass fiber/epoxy laminates for marine applications. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, L.F.M.; Sato, C. Design of Adhesive Joints Under Humid Conditions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, W.K.; Crocombe, A.D.; Wahab, M.M.A.; Ashcroft, I.A. Modelling anomalous moisture uptake, swelling and thermal characteristics of a rubber toughened epoxy adhesive. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2005, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.W.; Sekiguchi, Y.; Shimamoto, K.; Akiyama, H.; Sato, C. Direct measurement of the diffusion coefficient of adhesives from moisture distribution in adhesive layers using near-infrared spectroscopy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 54610–54626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wapner, K.; Grundmeier, G. Spatially resolved measurements of the diffusion of water in a model adhesive/silicon lap joint using FTIR-transmission-microscopy. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2004, 24, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.W.; Sekiguchi, Y.; Shimamoto, K.; Akiyama, H.; Sato, C. Experimental measurement of moisture distribution in the adhesive layer using near-infrared spectroscopy. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e53982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.W.; Sekiguchi, Y.; Shimamoto, K.; Akiyama, H.; Sato, C. Effect of rapid interfacial moisture penetration on moisture distribution within adhesive layers. Mater. Lett. 2025, 381, 137768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Shao, X.; Li, L.; Zheng, G. Effect of hygrothermal ageing on the mechanical performance of CFRP/AL single-lap joints. J. Adhes. 2022, 98, 2446–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsivalis, I.; Feih, S. Prediction of moisture diffusion and failure in glass/steel adhesive joints. Glass Struct. Eng. 2022, 7, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leplat, J.; Stamoulis, G.; Bidaud, P.; Thévenet, D. Investigation of the mode I fracture properties of adhesively bonded joints after water ageing. J. Adhes. 2022, 98, 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Tao, M.; Yu, J.; Zou, Y.; Jia, Z. Effect of graphene nanoplatelets on mode I fracture toughness of epoxy adhesives under water aging conditions. J. Adhes. 2024, 100, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameli, A.; Papini, M.; Spelt, J.K. Hygrothermal degradation of two rubber-toughened epoxy adhesives: Application of open-faced fracture tests. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2011, 31, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzami, M.; Ayatollahi, M.R.; Akhavan-Safar, A.; de Freitas, S.T.; Poulis, J.A.; da Silva, L.F.M. Effect of cyclic aging on mode I fracture energy of dissimilar metal/composite DCB adhesive joints. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2022, 271, 108675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houjou, K.; Akiyama, H.; Shimamoto, K. Fatigue properties and degradation of cured epoxy adhesives under water and air environments. Materials 2025, 18, 4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiman, S.; Putra, I.K.P.; Setyawan, P.D. Effects of the media and ageing condition on the tensile properties and fracture toughness of epoxy resin. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2016, 134, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, H.; Low, I.M. Effect of water absorption on the mechanical properties of nano-filler reinforced epoxy nanocomposites. Mater. Des. 2012, 42, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuoka, T.; Iwai, M.; Abiko, K. Effect of water on peel load of epoxy adhesive to heat-treated aluminum. J. Adhes. Soc. Jpn. 2025, 61, 259–265. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, K.; Shimoi, Y.; Miura, T.; Morita, H.; Akiyama, H.; Horiuchi, S. Disentangling origins of adhesive bonding at interfaces between epoxy/amine adhesive and aluminum. Langmuir 2023, 39, 10625–10637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, S.; Yamamoto, S.; Tsuji, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Yoshizawa, K. Theoretical study on the contribution of interfacial functional groups to the adhesive interaction between epoxy resins and aluminum surfaces. Langmuir 2022, 38, 6653–6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwai, M.; Mitsuoka, T.; Ikawa, T.; Abiko, K. Evaluation of aluminum surface factors affecting the adhesive strength of epoxy adhesives. J. Jpn. Inst. Light Met. 2024, 74, 271–275. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, H.; Kanamori, K.; Okada, K.; Yonezu, A. Fracture behavior of an alumina/epoxy resin interface and effect of water molecules by using molecular dynamics with reaction force field (ReaxFF). Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2022, 119, 103251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Tsuji, Y.; Kuwahara, R.; Yoshizawa, K.; Tanaka, K. Effect of condensed water at an alumina/epoxy resin interface on curing reaction. Langmuir 2024, 40, 12613–12621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; Lv, F.; Wan, H. Molecular-level understanding of the strength degradation of aluminum-adhesive bonding interface under water immersion. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 56, 105521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, B.R.K.; Kinloch, A.J.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, F.S.; Teo, W.S. The fracture behavior of adhesively-bonded composite joints: Effect of rate of test and mode of loading. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2012, 49, 1434–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiguchi, Y.; Sato, C. Experimental investigation of the effects of adhesive thickness on the fracture behavior of structural acrylic adhesive joints under various loading rates. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2021, 105, 102782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, S.A.; González, E.V.; Blanco, N.; Pernas-Sánchez, J.; Artero-Guerrero, J.A. Guided double cantilever beam test method for intermediate and high loading rates in composites. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2023, 264, 112118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.V.M.; Akhavan-Safar, A.; Carbas, R.; Marques, E.A.S.; Goyal, R.; El-Zein, M.; da Silva, L.F.M. Paris law relations for an epoxy-based adhesive. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2020, 234, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, I.; Alowayed, Y.; Albinmousa, J.; Lubineau, G.; Merah, N. Fatigue crack growth in laser-treated adhesively bonded composite joints: An experimental examination. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2021, 105, 102784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiguchi, Y.; Shimamoto, K.; Houjou, K.; Sato, C. Fatigue crack growth analysis of a ductile structural acrylic adhesive under constant-amplitude load control at various loading conditions. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2025, 140, 104049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banea, M.D.; da Silva, L.F.M.; Campilho, R.D.S.G. Mode I fracture toughness of adhesively bonded joints as a function of temperature: Experimental and numerical study. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2011, 31, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, A.; Lima, R.A.A.; Cardamone, S.; Campbell, R.B.; Slocum, A.H.; Giglio, M. Effect of temperature on cohesive modelling of 3M Scotch-Weld 7260 B/A epoxy adhesive. J. Adhes. 2020, 96, 437–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, A.; Sekiguchi, Y.; Sato, C. Effect of temperature and loading rate on the mode I fracture energy of structural acrylic adhesives. J. Adv. Join. Process. 2022, 5, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JIS K6251:2010; Rubber, Vulcanized or Thermoplastics—Determination of Tensile Stress-Strain Properties. Japanese Industrial Standards: Tokyo, Japan, 2010.

- ASTM D3433-99; Standard Test Method for Fracture Strength in Cleavage of Adhesives in Bonded Metal Joints. ASTM International: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2020. [CrossRef]

- ISO 25217:2009; Adhesives–Determination of the Mode 1 Adhesive Fracture Energy of Structural Adhesive Joints Using Double Cantilever Beam and Tapered Double Cantilever Beam Specimens. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Terasaki, N.; Fujio, Y.; Sakata, Y.; Horiuchi, S.; Akiyama, H. Visualization of crack propagation for assisting double cantilever beam test through mechanoluminescence. J. Adhes. 2018, 94, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasaki, N.; Fujio, Y.; Horiuchi, S.; Akiyama, H. Mechanoluminescent studies of failure line on double cantilever beam (DCB) and tapered-DCB (TDCB) test with similar and dissimilar material joints. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2019, 93, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Blackman, B.R.K. Using digital image correlation to automate the measurement of crack length and fracture energy in the mode I testing of structural adhesive joints. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2021, 255, 107957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moura, M.F.S.F.; Morais, J.J.L.; Dourado, N. A new data reduction scheme for mode I wood fracture characterization using the double cantilever beam test. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2008, 75, 3852–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, F.; da Silva, L.F.M.; Tita, V. Compliance methods for bonded joints: Part II investigation of the equivalent crack methodology to obtain the strain energy release rate for mode I. J. Adhes. 2023, 99, 1791–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, E.H.; Kinloch, A.J. Mechanics of adhesive failure I. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1973, 332, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, E.H. A generalized theory of fracture mechanics. J. Mater. Sci. 1974, 9, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.