Abstract

Despite growing attention to corporate environmental responsibility, there is limited understanding of the psychological and social mechanisms linking corporate environmental responsibility to employees’ coworker-focused pro-environmental behaviors in the workplace, such as advocacy directed at peers. This study examined the influence of corporate environmental responsibility on employees’ coworker pro-environmental advocacy in the Chinese energy sector, with a sample of 1528 employees. Focusing on the mediating roles of long-term orientation, meaningful work, and sense of community, the research integrates insights from Social Exchange Theory, Self-determination Theory, and Affective Events Theory. The data were analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the hypothesized relationships. The findings revealed that corporate environmental responsibility positively impacted employees’ advocacy for eco-friendly behaviors among coworkers through forward-thinking attitudes, intrinsic motivation, and strengthened social bonds. The study offers theoretical contributions by unpacking the interplay of individual and organizational factors and provides practical recommendations for cultivating an environmentally conscious culture through value alignment, meaningful work initiatives, and fostering a strong sense of community.

1. Introduction

In the face of escalating ecological crises, corporate environmental responsibility (CER) has emerged as a strategic priority [1], particularly in carbon-intensive sectors with large environmental footprints. CER, a dimension of corporate social responsibility (CSR), refers to “practices that benefit the environment (or mitigate the adverse impact of business on the environment) that go beyond those that companies are legally obliged to carry out” [2]. Firms are increasingly expected to adopt proactive environmental strategies—encompassing pollution prevention, resource efficiency, and the development of clean technologies—to mitigate their ecological footprint. These strategies typically include initiatives such as improving material and energy efficiency, investing in renewable energy, reducing carbon emissions, and implementing circular economy practices [3,4]. In many national contexts, government pressure, stakeholder expectations, and cultural values emphasizing harmony between humans and nature strengthen the institutional legitimacy of CER [5,6]. Organizations with substantial environmental impacts therefore face growing moral and strategic imperatives to embed CER into their corporate strategy.

While research highlights organizational-level impacts of CER, fewer studies have examined how employees internalize and extend CER through peer-driven behaviors. Existing studies—such as Afsar and Umrani [7] and Shah et al. [8]—have shown that coworker advocacy can transmit sustainability norms, but they do not explore the combined cognitive, motivational, and relational mechanisms proposed in the present study. Our work extends this literature by identifying a sequential pathway (LTO to MW to SoC) linking CER to CPEA, thereby integrating previously unconnected psychological and social processes. One such behavior is coworker pro-environmental advocacy (CPEA), defined as voluntary efforts to promote sustainability among peers through sharing knowledge and encouraging eco-conscious practices [9]. Unlike top-down directives, CPEA embeds sustainability in workplace culture and reinforces the long-term effects of CER [10,11]. Prior studies have shown that peer influence and informal communication channels often determine whether sustainability initiatives truly take root within organizations [12,13]. Thus, understanding the micro-level psychological mechanisms translating corporate sustainability policies into everyday employee advocacy remains an urgent research priority.

To explain how CER fosters CPEA, this study focuses primarily on Social Exchange Theory (SET, [14]) and Self-Determination Theory (SDT, [15]) as its core guiding frameworks, with insights from Affective Events Theory (AET) [16] used in a complementary way to illuminate the affective dynamics of workplace relationships. From a social-exchange perspective, employees reciprocate environmentally responsible practices when they perceive fairness, trust, and organizational support for sustainability [8,11]. SDT emphasizes that intrinsic motivation arises when work satisfies needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness [15], suggesting that employees will champion environmental goals when they find their work meaningful and self-congruent. AET adds an affective layer, proposing that positive organizational events such as visible environmental commitment generate emotions that encourage prosocial engagement and advocacy [17].

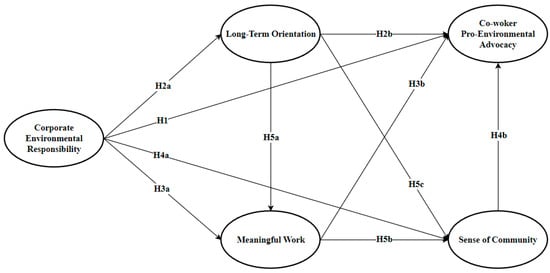

Building on these perspectives, we propose three mediators—Long-Term Orientation (LTO), Meaningful Work (MW), and Sense of Community (SoC)—representing cognitive, motivational, and social pathways through which CER translates into CPEA. LTO reflects employees’ emphasis on sustainability and persistence, often rooted in Confucian values that stress intergenerational responsibility and collective welfare [18,19]. MW captures the sense that one’s job contributes to societal and environmental good, thereby enhancing intrinsic motivation and moral fulfillment [20,21,22]. SoC denotes belonging and shared purpose among coworkers, strengthening trust and collaboration around environmental objectives [23,24,25]. Together, these mechanisms illustrate how CER shapes employees’ long-term thinking, purpose orientation, and communal ties, leading to sustained environmental advocacy within organizations.

China was responsible for 30% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2023 according to the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre. The energy sector accounts for nearly 90% of China’s greenhouse gas emissions, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). By examining these pathways in a high-impact industrial context, this study extends current understanding of how macro-level corporate responsibility translates into micro-level behavioral outcomes. It contributes to the literature by highlighting the interplay between organizational practices and individual psychology, offering theoretical integration and practical guidance for cultivating green organizational cultures in high-impact industries.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Corporate Environmental Responsibility and Coworker Pro-Environmental Advocacy

Corporate Environmental Responsibility (CER) concerns a firm’s relationship with the natural environment and its voluntary actions that go beyond legal requirements to mitigate ecological impact [2,26,27]. As a key dimension of corporate sustainability, CER encompasses strategic policies such as pollution prevention, energy efficiency, green innovation, and stakeholder collaboration aimed at achieving long-term ecological and social benefits [3,4,26]. In contemporary organizations, these initiatives are not only instrumental for meeting regulatory standards but also for enhancing corporate reputation, competitive advantage, and stakeholder trust on a global scale. As a universally recognized strategic imperative, CER has evolved into an international benchmark for sustainable business practices across both developed and emerging economies [27]. CER thereby represents both an ethical commitment and a strategic investment in organizational resilience and legitimacy, particularly in industries with visible environmental footprints such as oil, coal, and power generation.

Employees’ perceptions of CER strongly shape their attitudes and workplace behaviors. Drawing on Social Exchange Theory (SET; [11,17]), employees interpret corporate environmental initiatives as a form of organizational support and reciprocity, motivating them to respond with discretionary behaviors that align with sustainability goals [7,11]. When organizations demonstrate authentic environmental responsibility—through transparent policies, employee involvement, and resource allocation—employees are more likely to internalize these values and contribute voluntarily to eco-friendly practices. This psychological contract strengthens moral reflectiveness, trust, and identification with the company’s environmental mission, fostering a positive cycle of reciprocal engagement and advocacy [7,8].

Coworker pro-environmental advocacy (CPEA) captures one such form of employee-led environmental citizenship. In this study, we focus specifically on CPEA as a distinct interpersonal behavior that is theorized to diffuse pro-environmental norms across work groups and, in turn, to catalyze broader individual and collective environmental actions. It refers to “the extent to which work group members openly discuss environmental sustainability, share relevant knowledge, and communicate their various views in order to encourage others to engage in eco-friendly behavior” [9]. Unlike top-down managerial directives, CPEA emerges organically within social interactions and is sustained through peer influence, modeling, and emotional contagion [12,13]. These informal exchanges reinforce the salience of sustainability norms within daily routines, transforming environmental goals into shared social practices.

Referent influence—the tendency to emulate respected or knowledgeable colleagues—plays a particularly strong role in fostering behavioral diffusion [9]. When influential employees model sustainable actions such as waste reduction, recycling, or energy conservation, others are more likely to adopt and replicate them. Social norms also provide powerful behavioral cues: descriptive norms represent what is commonly practiced in the workplace, while injunctive norms convey collective approval for pro-environmental actions [8]. Together, these norms normalize sustainability, embedding it into everyday routines and making green behavior part of employees’ social identity [10]. Information sharing and collaborative problem-solving further strengthen advocacy. Through informal knowledge networks and collective learning, employees exchange practical strategies—for instance, how to improve energy efficiency in equipment use or reduce paper consumption in administrative tasks—facilitating the diffusion of sustainability innovations across departments [7]. Over time, such peer-driven mechanisms create a self-reinforcing “green culture”, where environmental engagement is both socially valued and institutionally supported.

Despite CER’s growing importance, prior research has primarily emphasized broader Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) domains such as ethics, governance, and philanthropy [28,29,30], leaving micro-level psychological and social mechanisms within CER underexplored. This omission is especially critical in the energy sector, which remains one of the largest contributors to global carbon emissions but also a key arena for low-carbon innovation and green transformation. Understanding how CER influences employee advocacy behaviors like CPEA therefore provides crucial insight into how sustainability values move from policy to practice, offering actionable pathways to strengthen corporate environmental performance through human and cultural capital.

H1.

Corporate environmental responsibility (CER) is positively related to coworker pro-environmental advocacy (CPEA).

2.2. The Mediating Role of Long-Term Orientation

Long-Term Orientation (LTO) emphasizes future benefits, perseverance, and strategic foresight, transforming CER from a formal policy into shared behavioral norms that sustain environmental engagement over time [18,31]. Within the corporate context, LTO embodies an organization’s and its employees’ collective ability to sacrifice short-term gains for long-term ecological and social stability [32]. Employees with a strong LTO regard sustainability not as a temporary trend but as a moral and strategic necessity for organizational longevity and societal well-being [19]. They internalize CER values and persist in pro-environmental actions even when immediate outcomes are not visible or economically rewarding [33].

LTO fosters environmental awareness, behavioral consistency, and emotional commitment, which are especially vital in industries characterized by delayed sustainability payoffs, such as energy, construction, and manufacturing [34,35]. For example, renewable energy transitions, emissions control, and waste reduction programs often require patience, cumulative learning, and interdepartmental collaboration. Employees with a long-term mindset approach these initiatives as investments in the organization’s enduring competitiveness and legitimacy, rather than compliance tasks. This orientation enhances persistence and resilience, ensuring that environmental commitments are maintained even amid uncertainty or performance pressure [36].

From the perspective of Social Exchange Theory (SET; [11,14]), employees with high LTO reciprocate perceived organizational environmental commitment by demonstrating sustained loyalty and proactive engagement. LTO thus converts sustainability from top-down directives into bottom-up cultural participation: employees mentor peers, initiate green projects, and model consistent behaviors that collectively reinforce CER’s presence in everyday operations [11,37]. In this way, future orientation acts as a psychological bridge connecting organizational strategy with employee advocacy.

Importantly, LTO also enhances value congruence between employees and organizations. When individuals perceive alignment between their personal ethics and the firm’s environmental mission, they experience intrinsic motivation to champion sustainability in informal yet meaningful ways [38]. This moral alignment fosters a sense of identity and purpose, prompting employees to see themselves as environmental stewards rather than passive policy implementers. Employees who integrate ecological values into their professional self-concept act as informal ambassadors, spreading green norms through social influence, mentoring, and behavioral modeling [39].

At the collective level, a strong LTO catalyzes organizational learning and innovation. Over time, shared long-term thinking encourages experimentation with new technologies, adaptive management, and resource optimization, embedding CER within the organization’s structural and cultural fabric [40,41]. Empirical studies have confirmed that firms characterized by long-term strategic thinking—such as family-owned enterprises and energy multinationals—tend to exhibit stronger environmental performance, resilience, and stakeholder trust [35,41].

In collectivist cultural contexts like China, where endurance, harmony, and intergenerational responsibility are deeply embedded in social values, LTO amplifies CER’s psychological credibility and emotional resonance [42]. Employees interpret environmental commitment as part of fulfilling their duty to future generations, transforming sustainability into a shared moral enterprise rather than a managerial requirement. Consequently, LTO operates as a linchpin linking CER and CPEA through cognitive foresight, moral alignment, and enduring behavioral loyalty.

To cultivate LTO, organizations should engage in leadership modeling, value-based education, and recognition programs that reward long-term contributions rather than short-term metrics. Integrating LTO into talent development, sustainability communication, and reward systems enables companies to translate environmental commitments into enduring, employee-led behavioral change that supports both ecological and organizational resilience.

H2a.

CER is positively related to LTO.

H2b.

LTO is positively related to CPEA.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Meaningful Work

Meaningful work (MW) refers to the perception that one’s job holds personal significance, aligns with individual values, and contributes to broader organizational or societal goals [22,43]. Within the framework of Corporate Environmental Responsibility (CER), MW serves as a critical psychological bridge that helps employees interpret everyday work as part of a collective environmental mission. This sense of purpose transforms routine tasks into expressions of moral and social responsibility, fostering psychological fulfillment, intrinsic motivation, and long-term commitment to sustainability [20,21]. Employees who perceive their roles through an ecological lens internalize environmental values, develop a moral identity aligned with sustainability goals, and are more likely to promote these values through informal peer interactions and advocacy behaviors [44].

Drawing on Self-Determination Theory (SDT; [15]), MW’s mediating function can be explained through its ability to satisfy employees’ core psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Autonomy arises when employees voluntarily engage in eco-friendly practices consistent with their values; competence is reinforced when they feel effective in contributing to environmental improvements; and relatedness is fulfilled when their efforts are recognized and shared within the organization [15]. When these needs are met, intrinsic motivation emerges—employees pursue environmental goals not because they are externally rewarded but because doing so reflects who they are and what they believe in [45]. This intrinsic motivation sustains long-term advocacy and is more durable than compliance driven by managerial pressure or material incentives.

MW also contributes to the formation of a green organizational identity, reinforcing the link between self-concept and organizational purpose [38,46]. When employees view their work as meaningful and environmentally impactful, they are more likely to see themselves as agents of positive change. In collectivist cultures such as China, where work meaning is closely connected to group harmony and social contribution, MW strengthens employees’ sense of belonging and shared moral obligation toward environmental stewardship [23,38]. As a result, individuals become informal sustainability champions who inspire and mobilize peers through emotional contagion, storytelling, and social learning.

Moreover, MW acts as a motivational amplifier that enhances resilience in the face of sustainability challenges. Employees who perceive a strong sense of purpose are more persistent when progress is slow or outcomes are uncertain, reflecting psychological ownership of organizational sustainability goals [47]. This sense of purpose bridges economic and ecological objectives in high-impact sectors like energy, reframing production, logistics, and technological innovation as opportunities for environmental stewardship and intergenerational responsibility.

As environmental values become embedded in work design, sustainability shifts from a peripheral concern to a defining organizational ethos [48]. Leadership communication, peer modeling, and environmental training further reinforce this process, showing employees that every role—whether technical, administrative, or managerial—can contribute meaningfully to environmental goals [49]. Recent evidence also suggests that employees who experience MW are more innovative in generating green solutions and exhibit higher engagement and performance across sustainability-related tasks [21,44,50].

To effectively activate MW, organizations must ensure the authentic integration of sustainability goals into job roles, performance appraisal systems, and internal communication. Recognizing employees’ environmental contributions through storytelling, feedback, and symbolic rewards strengthens perceived meaning and enhances engagement [50]. Furthermore, leadership behaviors emphasizing empathy, authenticity, and shared purpose can magnify employees’ experience of MW, aligning personal values with organizational sustainability strategies [20,45].

Ultimately, MW functions as a motivational and relational conduit linking CER and CPEA. By allowing employees to perceive their work as part of a greater environmental purpose, MW fosters intrinsic motivation, organizational citizenship, and collective advocacy. Over time, this alignment between meaning, motivation, and mission becomes self-reinforcing, embedding sustainability within the organizational culture and transforming CER from policy into lived daily practice.

H3a.

CER is positively related to MW.

H3b.

MW is positively related to CPEA.

2.4. The Mediating Role of Sense of Community

To understand how CER fosters CPEA, it is essential to consider not only employees’ temporal (LTO) and motivational (MW) orientations but also their social-relational context. Sense of Community (SoC) complements these individual pathways by cultivating collective identity, shared meaning, and mutual responsibility within the workplace [51]. Rooted in community psychology, SoC reflects employees’ perception of belonging, emotional connection, and shared purpose with colleagues [15]. Within organizational contexts, this sense of community functions as the “social glue” that transforms sustainability from individual intention into collaborative practice, linking employees through trust, interdependence, and mutual care.

SoC arises when employees feel accepted, supported, and connected to one another, fostering trust, cooperation, and commitment to common goals [25]. This emotional bond facilitates open communication, collective problem-solving, and the diffusion of pro-environmental norms across teams. When employees experience belonging and psychological safety, they are more willing to share sustainability ideas, take environmental initiatives, and support others in adopting green behaviors [23,52]. SoC thereby enhances both morale and collective efficacy, allowing organizations to leverage the strength of social relationships to advance their environmental missions.

From a theoretical perspective, SoC can be largely understood through Social Exchange Theory (SET) as a relational resource that fosters reciprocity and cooperative action. When employees perceive strong relational support and reciprocity, they respond through discretionary behaviors that benefit the collective [11]. Positive affective experiences at work, as highlighted by Affective Events Theory (AET) [16], further reinforce these exchanges by making environmental engagement emotionally rewarding. In this sense, SoC acts as the emotional and relational infrastructure through which CER translates into everyday advocacy and cooperative green behaviors.

Practically, SoC manifests through mutual support, shared accountability, and coordinated environmental action. Employees embedded in cohesive networks are more likely to initiate or join sustainability committees, organize awareness campaigns, and engage in joint problem-solving around issues such as waste reduction, resource optimization, or workplace greening. Peer encouragement amplifies the perceived importance of environmental behavior, turning isolated efforts into shared endeavors. In this way, SoC magnifies CER’s impact by transforming individual motivation into collective, peer-supported engagement, reinforcing environmental responsibility as a social norm rather than a managerial directive.

Empirical studies have shown that when organizations nurture community bonds—through participatory decision making, cross-departmental collaboration, and recognition of shared achievements—employees’ environmental participation rises significantly [25,52]. Emotional and social rewards, such as appreciation, inclusion, and recognition, reinforce ongoing involvement and embed CER within organizational culture. Over time, such practices shift sustainability from a compliance-driven function to an integral aspect of organizational identity and shared pride [23,51].

In collectivist contexts like China, SoC resonates strongly with cultural values of harmony and collective responsibility, further enhancing its mediating effect between CER and CPEA. Employees interpret their pro-environmental engagement not merely as fulfilling job duties but as contributing to the well-being of their team and community. This collective consciousness strengthens both moral commitment and behavioral consistency, fostering a resilient and cohesive green culture.

H4a.

CER is positively related to SoC.

H4b.

SoC is positively related to CPEA.

2.5. The Sequential Pathway in the Integrated Model

The integrated model illustrates how CER influences CPEA through three sequential mediators—LTO, MW, and SoC—linking organizational sustainability signals to employees’ internal values and, ultimately, to proactive environmental behaviors. This framework shows how strategic environmental policies cascade from organizational to individual and collective levels, fostering a culture of sustainability.

The pathway begins with CER signaling a long-term ecological vision that transcends short-term profit motives. Such signals encourage employees to adopt future-oriented perspectives characterized by perseverance and planning across cultures [31,41]. When employees perceive their organization as sincerely committed to environmental stewardship, they are more likely to align their professional outlook with this vision, interpreting sustainability as a long-term investment rather than a short-term initiative [32]. This cognitive reframing strengthens psychological ownership and sustained commitment to green goals, establishing LTO as the first mechanism linking CER to employee engagement.

LTO then facilitates the development of MW by helping employees reinterpret their roles as meaningful contributions to broader ecological missions [22]. Routine tasks are understood within long-term environmental goals, fostering intrinsic motivation and moral purpose. According to Self-Determination Theory [15], when work satisfies needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness, employees internalize organizational values and sustain proactive engagement. Empirical research confirms that employees perceiving high MW in sustainability contexts exhibit greater initiative, resilience, and advocacy behaviors [45,46].

MW also catalyzes SoC by promoting shared purpose and values among coworkers. Employees who find their work meaningful are more likely to form trust-based relationships, collaborate, and co-create sustainability initiatives. SoC involves feelings of belonging, mutual influence, and shared emotional connection [25]. MW reinforces these dimensions, fostering cohesive environmental subcultures where contributions are recognized and collective goals are emphasized [44].

Finally, SoC translates internalized motivation into outward, peer-directed advocacy. Employees embedded in strong communities feel supported and responsible for influencing their peers, initiating green projects, and normalizing eco-friendly practices [46,53]. Through social modeling and informal communication, sustainability norms diffuse horizontally, strengthening bottom-up environmental movements.

Together, this pathway demonstrates a dynamic chain from strategic signaling (CER) to cognitive framing (LTO), emotional engagement (MW), social bonding (SoC), and behavioral expression (CPEA). Each link reinforces the next, creating a positive feedback loop that embeds sustainability within organizational culture and employee behavior. This model bridges micro-(psychological) and macro-(organizational) levels, offering actionable insights for leadership and HR strategies.

H5a.

LTO is positively related to MW.

H5b.

MW is positively related to SoC.

H5c.

LTO is positively related to SoC.

2.6. Theoretical Background

This study is grounded in three complementary theoretical frameworks—Social Exchange Theory (SET), Self-Determination Theory (SDT), and Affective Events Theory (AET)—which together explain how employees interpret corporate environmental responsibility (CER) and translate these perceptions into coworker pro-environmental advocacy (CPEA). SET provides the overarching lens for understanding how employees reciprocate organizational efforts [14]; SDT clarifies how CER fosters internalized motivation through meaningful work and long-term orientation [15]; and AET explains how positive work experiences such as meaningful work and sense of community (SoC) translate into prosocial and pro-environmental behaviors [16].

From the perspective of Social Exchange Theory, CER constitutes a form of organizational investment that signals care, responsibility, and long-term commitment to societal well-being. Employees who perceive such investment tend to reciprocate through positive attitudes and behaviors because they view CER as a high-quality social exchange resource [54]. This framework explains why CER enhances long-term orientation (LTO), meaningful work (MW), and sense of community (SoC), and why employees may respond with higher levels of pro-environmental advocacy among coworkers.

Drawing on Self-Determination Theory, CER can satisfy employees’ psychological needs for purpose, value alignment, and internalized motivation [15]. When employees perceive that their organization engages in environmentally responsible actions, they are more likely to view their work as meaningful and aligned with their personal values. LTO and MW thus function as mechanisms through which CER promotes autonomous motivation, ultimately encouraging employees to engage in voluntary green advocacy behaviors.

Finally, Affective Events Theory suggests that positive psychological experiences at work—such as meaningful work and a strong sense of community—generate affective states that facilitate prosocial and citizenship behaviors [16]. MW and SoC represent emotionally salient aspects of the work environment that influence interpersonal relations and supportive actions. These positive affective experiences increase the likelihood that employees will engage in discretionary behaviors such as coworker pro-environmental advocacy.

Together, these three theories form an integrated explanatory framework supporting the proposed sequential pathway in which CER promotes LTO, which enhances MW, which strengthens SoC, ultimately leading to greater CPEA.

Building on the above theoretical integration, this study addresses the following overarching research question:

RQ1:

How does employees’ perception of corporate environmental responsibility relate to coworker pro-environmental advocacy through long-term orientation, meaningful work, and sense of community?

The hypotheses are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The Proposed Conceptual Model Illustrating the Mediating Roles of Long-Term Orientation, Meaningful Work, and Sense of Community in the Relationship Between Corporate Environmental Responsibility and Coworker Pro-Environmental Advocacy.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants and Procedures

The participating organization was a large energy group in China that operates multiple subsidiaries of comparable size and organizational structure. The group publishes an annual environmental performance report and maintains certification under ISO 14001, the international standard for environmental management systems [55], providing externally verified evidence of its sustained engagement in environmental responsibility initiatives. This ensured that all participating employees were exposed to a consistent level of CER practices across the organization. This study forms part of a broader research project aimed at understanding and promoting the psychological and organizational factors that drive pro-environmental behavior among employees. Given the minimal-risk nature of the study, which involved only anonymous survey responses without the collection of sensitive personal or health-related data, formal institutional ethical approval was not required. Approval for conducting the survey was obtained directly from the participating organization—a major energy group based in Shandong, China—whose senior management confirmed that the research aligned with the company’s strategic initiatives to strengthen environmental responsibility and sustainable organizational practices. The organization authorized data collection on the grounds that the study posed no psychological, physical, or social risk to employees.

The questionnaire was initially piloted with a small group of managers and frontline employees to evaluate the clarity, relevance, and neutrality of the items. Revisions were made based on their feedback to enhance comprehensibility and ensure cultural appropriateness. Participation was entirely voluntary, and employees were informed through internal communication channels that the survey was part of an academic research initiative with organizational endorsement, but that responses would remain confidential and anonymous. Informed consent was obtained digitally before proceeding with the questionnaire, and participants had the option to withdraw at any point without penalty.

Data were collected through Wenjuanxing, a widely used online survey platform in China. The survey was open for a two-week period in December 2024. A total of 1528 valid responses were obtained. Of the initial invitees, 50 individuals declined to participate. The final sample included employees from various subsidiaries across the country, primarily located in Shandong and Inner Mongolia. The demographic breakdown was as follows: 1226 males, 280 females, 5 individuals identifying as non-binary or third gender, and 17 who preferred not to disclose their gender. The mean age was 38.95 years (SD = 8.97).

All data were stored securely, accessible only to the research team, and used strictly for academic purposes. The ethical conduct of this research adheres to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and complies with all relevant national and institutional guidelines for social science research involving human participants.

3.2. Measures

All scales used in this study were originally developed in English and were translated into Chinese using the established translation and back-translation procedure [56]. The items are shown in Appendix A. This process ensures linguistic and cultural equivalence, minimizing the potential for misinterpretation and maintaining the reliability and validity of the scales in the Chinese context. All measurements appeared to have acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s α > 0.70) in our sample.

Participants first indicated to what extent they feel their organization engages in corporate environmental responsibility (CER), and the 8-item scale was developed by Sharpe et al. [37]. Participants responded on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (totally agree). Sample items from the scale are: “My organization is concerned with reducing its environmental impact.” and “My organization aims to support environmental causes.” The internal consistency reliability was excellent for the scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94).

Long-term Orientation (LTO) was measured using an 8-item scale adapted from Bearden et al. [18], Strathman et al. [57], and Fetchenhauer and Rohde [58]. Participants responded to each statement on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Not descriptive”) to 5 (“Exactly descriptive”). A sample item from the scale is: “I frequently think about the long-term implications of my decisions.” Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88.

Meaningful work (MW; one component of spirituality at work) was measured using a 6-item scale developed by Ashmos and Duchon [59]. Participants responded on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Completely disagree”) to 7 (“Totally agree”). A sample item from the scale is: “Work is connected to what I think is important in life.” The scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.96.

Sense of community (SoC; one component of workplace spirituality) was measured using a 7-item scale developed by Ashmos and Duchon [59]. Participants responded on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Completely disagree”) to 7 (“Totally agree”). A sample item from the scale is: “Working cooperatively with others is valued.” The scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.97.

Coworker pro-environmental advocacy (CPEA) was measured using a 3-item scale developed by Kim et al. [9]. This scale assesses the frequency with which employees encourage their coworkers to engage in pro-environmental behaviors. Responses were recorded on a 5-point frequency scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). A sample item includes “I try to convince my group members to reduce, reuse, and recycle office supplies in the workplace”. Cronbach’s α for the three items was 0.92.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Model Fit

The current dataset was analyzed using SPSS 26.0 and Mplus 8.3. As illustrated in Table 1, all variables are significantly correlated with each other, but the magnitudes of the correlations remain below commonly used thresholds for multicollinearity concerns. To further ensure the absence of multicollinearity issues, multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIF) and tolerance statistics. Results revealed that all predictor variables demonstrated acceptable levels, with VIF values ranging from 1.121 to 3.848 (well below the conservative threshold of 10) and tolerance statistics ranging from 0.260 to 1 (exceeding the critical value of 0.10). These results confirm the absence of substantial multicollinearity among the independent variables, thereby ensuring the reliability of subsequent regression estimates. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin values for each variable exceeded the threshold of 0.70, with the Bartlett test demonstrating significance (p < 0.001), indicating the suitability of the dataset for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). In addition, all constructs demonstrated satisfactory composite reliability (CR > 0.60), and AVE values exceeded the recommended 0.50 threshold for convergent validity, with LTO’s AVE (0.54) also falling within the acceptable range [60,61].

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations.

Given that all data were collected from the same survey instrument, common method bias (CMB) was also assessed. We employed the Unmeasured Latent Method Construct (ULMC) approach by comparing a bifactor model incorporating a latent method factor (M2) against the baseline measurement model (M1) [62]. The results showed no meaningful improvement in model fit (M2 − M1: ∆CFI = 0.008, ∆TLI = 0.004, ∆RMSEA = −0.001, ∆SRMR = 0.000), indicating the absence of substantial CMB and confirming that the observed relationships were not driven by measurement artifacts.

In addition, the structural model demonstrated acceptable fit considering methodological rigor and sample size considerations. While the χ2/df ratio (9.43) is a bit large, this metric’s well-documented sensitivity to large samples (N = 1528) warrants contextual interpretation [63,64]. Notably, supplementary robust fit indices collectively satisfy established criteria for model adequacy: The RMSEA of 0.07 falls below the 0.08 conservative cutoff for reasonable approximation error, while both CFI (0.92) and TLI (0.92) surpass the 0.90 benchmark for comparative fit [65,66]. The SRMR value (0.04) is well below 0.06. This constellation of fit statistics suggests the model effectively captures the underlying data structure, especially when considering the increased statistical stringency inherent in large-scale samples [67].

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

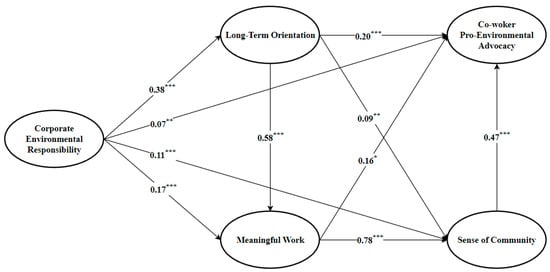

Figure 2 presents the standardized results of the path analyses after controlling for participants’ age and gender. As illustrated, CER could positively predict LTO (β = 0.38, p < 0.001; 95% CI [0.33, 0.44]), MW (β = 0.17, p < 0.001; 95% CI [0.12, 0.22]), CPEA (β = 0.07, p < 0.01; 95% CI [0.03, 0.12]), and SoC (β = 0.11, p < 0.001; 95% CI [0.07, 0.15]). Further, LTO can also positively predict MW (β = 0.58, p < 0.001; 95% CI [0.52, 0.63]), CPEA (β = 0.20, p < 0.001; 95% CI [0.14, 0.26]), and SoC (β = 0.09, p < 0.01; 95% CI [0.03, 0.15]). MW could further positively predict CPEA (β = 0.16, p < 0.05; 95% CI [0.04, 0.28]) and SoC (β = 0.78, p < 0.001; 95% CI [0.72, 0.83]). Lastly, SoC can positively predict by CPEA (β = 0.47, p < 0.001; 95% CI [0.35, 0.59]).

Figure 2.

Standardized Model Results. Note. *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

5. Discussion

5.1. General Findings

This study confirms that corporate environmental responsibility (CER) significantly increases employees’ coworker pro-environmental advocacy (CPEA), supporting prior research demonstrating that CER shapes organizational culture, enhances employee engagement, and facilitates the informal diffusion of sustainable behaviors [2,8,10]. Consistent with Sharpe et al. [37] and Afsar and Umrani [7], our findings underscore that organizational environmental responsibility does not remain confined to corporate policies but cascades into employee cognition, motivation, and peer-level advocacy. Importantly, this relationship is mediated by three interrelated mechanisms—long-term orientation (LTO), meaningful work (MW), and sense of community (SoC)—which channel top-down sustainability signals into bottom-up behavioral change. These mediators jointly reveal how CER fosters a psychologically rich and socially cohesive climate that promotes enduring pro-environmental engagement.

LTO emerged as a key predictor of sustainability advocacy. Consistent with Christie et al. [31], Wang and Bansal [41], and Dou et al. [42], employees with stronger future orientation were more likely to align their personal aspirations with organizational environmental vision, treating sustainability as a strategic, moral, and intergenerational investment. This confirms that employees’ temporal cognition acts as a cognitive filter translating corporate sustainability messages into personal long-term goals [42]. Moreover, LTO fostered MW, supporting Bukowski and Rudnicki’s [52] claim that future-oriented individuals derive stronger purpose from their work. This finding complements Self-Determination Theory (SDT; [15]), as intrinsic motivation—grounded in autonomy, competence, and relatedness—emerges when employees perceive their work as contributing to meaningful, future-oriented environmental outcomes.

MW played a central mediating role, linking job meaning to environmental goals and motivating employees to act as proactive change agents [22,44]. In line with Raub and Blunschi [44] and Bhatnagar and Aggarwal [21], meaningful work transformed sustainability from a compliance requirement into a source of personal and collective fulfillment. MW not only energized individual intrinsic motivation but also served as the cognitive–emotional bridge connecting environmental commitment with social engagement. Employees who perceived their environmental contributions as significant reported higher persistence and were more likely to mentor or inspire their peers, creating ripple effects across teams [22,50].

SoC provided the relational infrastructure necessary to sustain these behaviors. Employees embedded in cohesive, trust-based communities internalized shared environmental goals and modeled sustainability practices in their daily routines [25,53]. Consistent with D’Aprile and Talò [23] and Forsyth et al. [53], our results highlight that social belonging and shared purpose amplify employees’ sense of responsibility for collective environmental outcomes. The interaction between MW and SoC created a reinforcing loop: meaningful work fostered shared vision and emotional attachment, while strong community bonds amplified advocacy and cooperation [48,51]. This synergy illustrates that pro-environmental engagement is both psychologically rooted and socially maintained.

Overall, the findings validate the integrated sequential mediation model (Figure 1): CER promotes LTO, which enhances MW, which strengthens SoC, collectively driving CPEA. This psychological–social chain is especially crucial in high-impact industries like the energy sector, where large-scale sustainability transformations depend on collective commitment and continuous employee involvement [37]. Our results extend previous studies (e.g., [7,28,29]) by identifying distinct cognitive (LTO), motivational (MW), and relational (SoC) pathways that jointly explain how organizational initiatives translate into peer-level environmental advocacy.

In collectivist cultural contexts such as China, where long-term thinking, social harmony, and relational interdependence are deeply embedded cultural norms, these mechanisms appear particularly salient [38,42]. Employees interpret CER not merely as an institutional requirement but as a moral and relational obligation toward the organization and society. Thus, rather than viewing CER as a top-down strategy, this study positions it as a socially embedded psychological process, providing a multilevel blueprint for cultivating workplace cultures that sustain environmental responsibility from the ground up.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study advances CER research by integrating psychological, social, and organizational perspectives to explain how corporate sustainability initiatives shape employee behavior. By examining Long-Term Orientation (LTO), Meaningful Work (MW), and Sense of Community (SoC) as mediators, it conceptualizes CER not only as a strategic initiative but also as a psychological and social process. Drawing on Social Exchange Theory (SET) and Self-Determination Theory (SDT) as the primary lenses, the study offers a comprehensive framework linking organizational practices, individual motivation, and cultural factors to workplace sustainability engagement, with Affective Events Theory (AET) providing complementary insight into the emotional tone of these social exchanges.

First, it extends SET by identifying LTO as a key psychological mechanism connecting CER to pro-environmental advocacy. Consistent with SET’s principle of reciprocal obligations, future-oriented cognition aligns employees’ ethical standards and career goals with organizational sustainability commitments. Employees internalize environmental values when they perceive CER as both morally meaningful and strategically beneficial, highlighting the role of long-term thinking in sustaining workplace environmental action.

Second, the study applies SDT to explain how MW channels CER into intrinsic motivation and sustained engagement. Employees who find their work meaningful are more likely to support environmental initiatives because their psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are fulfilled. This extends SDT to sustainability contexts by showing how MW links professional tasks with broader environmental and social goals, reinforcing internal motivation for eco-advocacy.

Third, it connects with AET by emphasizing SoC as a critical social mechanism for environmental responsibility. Positive social and emotional connections enhance commitment to sustainability, illustrating how workplace experiences shape pro-environmental behavior. SoC interacts with LTO and MW to create supportive networks that encourage cooperation, shared goals, and emotional investment in sustainability, reinforcing the idea that environmental engagement is socially embedded.

Finally, by situating these mechanisms within collectivist cultural contexts such as China, the study highlights how shared values and hierarchical structures shape the effectiveness of CER. In such settings, belonging and collective purpose amplify sustainability engagement, illustrating the cultural contingency of psychological and social processes in organizational contexts.

Overall, this research enriches theoretical understandings of workplace sustainability by showing how temporal, motivational, and relational mechanisms jointly mediate the effects of CER, offering a multi-level framework that bridges corporate strategy with individual and collective action.

5.3. Practical Implications

Organizations can enhance CER effectiveness by integrating future orientation, meaningful work, and workplace community to foster employee-led sustainability. Creating forums for sharing ideas, cross-functional sustainability committees, and leadership programs emphasizing long-term environmental goals can strengthen LTO, MW, and SoC simultaneously. This multifaceted approach encourages employees not only to adopt sustainable practices but also to advocate for them among peers, creating a reinforcing loop between corporate initiatives and employee behavior.

Companies should recognize that CER influences pro-environmental advocacy both directly and through psychological and social mediators. Programs must therefore be employee-centered, aligning sustainability initiatives with personal values, professional goals, and workplace belonging. Regular assessments of employee attitudes and engagement can identify strengths, address obstacles, and refine CER strategies.

Cultivating a future-oriented mindset, shared purpose, and collaborative culture can generate a self-sustaining cycle of environmental participation across teams and departments. A comprehensive strategy that combines LTO, MW, and SoC will maximize CER’s impact on workplace sustainability and long-term organizational success. Future research should explore industry differences, leadership styles, and cultural variations to tailor these approaches to diverse contexts.

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

It is important to recognize that this study has a number of limitations, which also provide chances for further research to expand on the model’s conclusions.

The cross-sectional design of the research restricts the capacity to draw conclusions about the causative linkages among CER, the mediators (LTO, MW, and SoC), and CPEA. Future studies might examine the dynamic connections between these factors throughout time using experimental or longitudinal methodologies. These methods would provide stronger support for the model’s suggested causal pathways.

The study’s conclusions may not be as applicable to other industrial and cultural settings since it was limited to China’s energy industry. The observed associations could be different in more individualistic cultures or in businesses with lesser environmental risks because of the collectivist character of Chinese society and the energy industry’s significant environmental effect. Future studies might compare cultures or examine different businesses to get a better understanding of how cultural and industrial factors influence the mechanisms linking CER to pro-environmental action. Furthermore, the sample was heavily male-dominated (approximately 80% male), reflecting the gender composition of the participating organization but potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings to more gender-balanced workplaces; future research should aim to recruit more gender-diverse samples and examine whether gender moderates the links between CER, the mediating mechanisms, and pro-environmental advocacy.

It is possible that response biases such as social desirability or common method variance occurred in this study due to the use of self-reported measures. To get around this, researchers may use multi-source data in future studies, such as ratings from coworkers or supervisors or objective measures of behavior. By using these other data sets, we may strengthen the reliability of the findings and get a deeper understanding of the relationships inside the model.

Even with LTO, MW, and SoC included as mediators in the model, additional psychological or organizational factors may still impact the connection between CER and CPEA. Leadership styles, organizational justice, and employees’ happiness are a few more potential moderators or mediators. Future research may look at these aspects to learn more about the mechanisms behind environmentally friendly working practices. Moreover, our outcome variable focused on coworker pro-environmental advocacy rather than employees’ own objectively observed pro-environmental behaviors; future studies could incorporate behavioral indicators (e.g., energy use, waste reduction) or multi-source ratings to more fully trace how advocacy translates into concrete environmental actions.

6. Conclusions

The research used structural equation modeling (SEM) to investigate the relationship between CER and CPEA in China’s energy industry, drawing on theories such as Social Exchange Theory, Self-determination Theory, and Affective Events Theory. The results showed that CER greatly improved advocacy behaviors, with strong mediating roles played by LTO, MW, and SoC. At LTO, we strive to create a future-focused culture by aligning employee ambitions with our corporate sustainability objectives. By linking employees’ responsibilities to broader environmental objectives, MW increases their intrinsic motivation, and the strong fostering of teamwork and trust by SoC encourages collective environmental action. When used in conjunction, these mediators strengthen CER’s effect on environmentally responsible business activities. By integrating several social and psychological channels, this research helps close theoretical gaps in our understanding of CER’s function in encouraging eco-conscious behavior and offers practical guidance to companies. Longitudinal studies or future exploration of other cultural and industrial contexts can help researchers better grasp CER’s long-term effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. and M.X.; methodology, J.C.; software, J.C.; validation, J.C.; formal analysis, J.C.; investigation, J.C.; resources, J.C.; data curation, X.L. and M.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L. and M.X.; writing—review and editing, J.C. and M.B.; visualization, J.C.; supervision, M.B.; project administration, M.B.; funding acquisition, M.X. and J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China Scholarship Council (No. 202207000022) from M.X.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study received an ethical review exemption from the company responsible for distributing the questionnaires and collecting the data. The organization determined that formal ethical approval was not required because the research involved only anonymous, self-report survey data, posed no physical or psychological risk to employees, and did not involve the collection of any sensitive personal or health-related information. The study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles for minimal-risk social science research.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants were above the age of 16 and provided informed consent prior to participation. They were clearly informed about the study’s purpose, the voluntary nature of their involvement, the anonymity of responses, and their right to withdraw at any time without consequences. No incentives or coercion were used, and all data were used solely for academic research purposes. No identifying information was collected, and data confidentiality was rigorously maintained.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study were obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Corporate environmental responsibility [37].

7-point Likert scale: 1 = completely disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = slightly disagree; 4 = neither agree nor disagree; 5 = slightly agree; 6 = agree; 7 = totally agree.

Based on your experience within the organization you work for, we ask you to consider the corporate values and the concrete actions promoted or adopted by the organization. Please indicate your degree of disagreement/agreement with the following statements:

- My organization cares about reducing its environmental impact.

- My organization believes it is important to protect the environment.

- My organization is dedicated to minimizing its negative impact on the environment.

- My organization has taken action to reduce its environmental impact.

- My organization aims to support environmental causes.

- My organization is concerned with reducing its environmental impact.

- My organization is committed to implementing environmentally friendly policy and procedures.

- My organization has the mission to minimize its negative impact on the environment.

Coworker pro-environmental advocacy [9].

Respondents would rate each statement on a scale of “always,” “often,” “sometimes,” “rare,” and “never”.

Based on your work experience in the organization, we ask you to consider your collaborative relationship with your colleagues. Please indicate the extent to which you disagree or agree with the following statements:

- I try to convince my group members to reduce, reuse, and recycle office supplies in the workplace.

- I work with my group members to create a more environmentally friendly workplace.

- I share knowledge, information, and suggestions on workplace pollution prevention with other group members.

Meaningful work [59].

7-point Likert scale: 1 = completely disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = slightly disagree; 4 = neither agree nor disagree; 5 = slightly agree; 6 = agree; 7 = totally agree.

Based on your experience working in the organization you work for, we ask you to consider the work culture promoted and specific actions taken by the organization. Please indicate the extent to which you disagree/agree with the following statements:

- Experience joy in work.

- Spirit is energized by work.

- Work is connected to what I think is important in life.

- Look forward to coming to work.

- See a connection between work and social good.

- Understand what gives my work personal meaning.

Sense of community [59].

7-point Likert scale: 1 = completely disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = slightly disagree; 4 = neither agree nor disagree; 5 = slightly agree; 6 = agree; 7 = totally agree.

Based on your experience working in the organization you work for, please indicate the extent to which you disagree/agree with sense of community:

- Working cooperatively with others is valued.

- Feel part of a community.

- Believe people support each other.

- Feel free to express opinions.

- Think employees are linked with a common purpose.

- Believe employees genuinely care about each other.

- Feel there is a sense of being a part of a family.

Long-Term Orientation [18,57,58],

Respondents would rate each statement on a scale of 1 (“Not descriptive”) to 5 (“Exactly descriptive”).

These statements are designed to measure the extent to which you focus on long-term versus short-term impacts when making decisions. Please rate each statement based on your actual situation:

- I always plan ahead for the long-term.

- I frequently think about the long-term implications of my decisions.

- I consider how things might be in the future and try to influence those things with my day-to-day behavior.

- I am more concerned with what happens to me in the short run than in the long run.

- I don’t devote much thought and effort to preparing for the future.

- I think it is important to take warnings about negative outcomes seriously even if the negative outcome will not occur for many years.

- My behavior is only influenced by the immediate (i.e., a matter of days or weeks) outcomes of my actions.

References

- Jiang, Y.; Xue, X.; Xue, W. Proactive corporate environmental responsibility and financial performance: Evidence from Chinese energy enterprises. Sustainability 2018, 10, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunningham, N. Shaping corporate environmental performance: A review. Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Jian, W.; Zeng, Q.; Du, Y. Corporate environmental responsibility in polluting industries: Does religion matter? J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, S.; Silvestre, B.S. Managing stakeholder relations when developing sustainable business models: The case of the Brazilian energy sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.H.; Zeng, S.X.; Shi, J.J.; Qi, G.Y.; Zhang, Z.B. The relationship between corporate environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical study in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 145, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Lo, C.W.H.; Li, P.H.Y. Organizational visibility, stakeholder environmental pressure and corporate environmental responsiveness in China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Umrani, W.A. Corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behavior at workplace: The role of moral reflectiveness, coworker advocacy, and environmental commitment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.H.A.; Cheema, S.; Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Ali, M.; Rafiq, N. Perceived corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behaviors: The role of organizational identification and coworker pro-environmental advocacy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Kim, Y.; Han, K.; Jackson, S.E.; Ployhart, R.E. Multilevel influences on voluntary workplace green behavior: Individual differences, leader behavior, and coworker advocacy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1335–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Environmental sustainability at work: A call to action. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 5, 444–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, G.C. Social behavior as exchange. Am. J. Sociol. 1958, 63, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mount, M.K.; Li, N. The theory of purposeful work behavior: The role of personality, higher-order goals, and job characteristics. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2013, 38, 132–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, M.; Fay, D. Personal initiative: An active performance concept for work in the 21st century. Res. Organ. Behav. 2001, 23, 133–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and the “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.M.; Cropanzano, R. Affective events theory. Res. Organ. Behav. 1996, 18, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, R.; Shahzad, K.; Donia, M.B. Environmentally specific transformational leadership and employee green attitude and behavior: An affective events theory perspective. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 92, 102181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearden, W.O.; Money, R.B.; Nevins, J.L. A measure of long-term orientation: Development and validation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Vocino, A.; Grimmer, M.; Miles, M.P. The interrelationship between temporal and environmental orientation and pro-environmental consumer behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hawari, M.A.; Quratulain, S.; Melhem, S.B. How and when frontline employees’ environmental values influence their green creativity? Examining the role of perceived work meaningfulness and green HRM practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, J.; Aggarwal, P. Meaningful work as a mediator between perceived organizational support for environment and employee eco-initiatives, psychological capital and alienation. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2020, 42, 1487–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B.D.; Dekas, K.H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Res. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aprile, G.; Talò, C. How corporate social responsibility influences organizational commitment: A psychosocial process mediated by organizational sense of community. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2015, 27, 241–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, G.N.; Deline, M.B.; McComas, K.; Chambliss, L.; Hoffmann, M. Saving energy at the workplace: The salience of behavioral antecedents and sense of community. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.W.; Chavis, D.M. Sense of community: A definition and theory. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dögl, C.; Holtbrügge, D. Corporate environmental responsibility, employer reputation and employee commitment: An empirical study in developed and emerging economies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1739–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtbrügge, D.; Dögl, C. How international is corporate environmental responsibility? A literature review. J. Int. Manag. 2012, 18, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, Z.; Khan, I.U.; Islam, T.; Sheikh, Z.; Naeem, R.M.; Rehman, A.U. Corporate social responsibility and employee pro-environmental behaviors: The role of perceived organizational support and organizational pride. South. Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2019, 8, 246–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, B.; Gunarathne, N.; Gaskin, J.; Ong, T.S.; Ali, M. Environmental corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behavior: The effect of green shared vision and personal ties. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 186, 106572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Farrukh, M.; Iqbal, M.K.; Farhan, M.; Wu, Y. Corporate social responsibility and employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior: The role of organizational pride and employee engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1104–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, P.M.J.; Kwon, I.W.G.; Stoeberl, P.A.; Baumhart, R. A cross-cultural comparison of ethical attitudes of business managers: India, Korea, and the United States. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 46, 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, M.; Sircova, A. Dispositional orientation to the present and future and its role in pro-environmental behavior and sustainability. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Kim, J. Corporate social responsibility as a determinant of long-term orientation. Serv. Ind. J. 2020, 40, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durach, C.F.; Wiengarten, F. Environmental management: The impact of national and organisational long-term orientation on plants’ environmental practices and performance efficacy. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saether, E.A.; Eide, A.E.; Bjørgum, Ø. Sustainability among Norwegian maritime firms: Green strategy and innovation as mediators of long-term orientation and emission reduction. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2382–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Manzardo, A. How does CEO environmentally specific servant leadership promote corporate environmental responsibility? The roles of TMT pro-environmental values, pro-environmental passion, and long-term orientation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 9726–9742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, E.; Ruepert, A.; van der Werff, E.; Steg, L. Corporate environmental responsibility leads to more pro-environmental behavior at work by strengthening intrinsic pro-environmental motivation. One Earth 2022, 5, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.C.; Rose, G.M.; Blodgett, J.G. The effects of cultural dimensions on ethical decision making in marketing: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Ethics 1999, 18, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Breton–Miller, I.; Miller, D. Why do some family businesses out-compete? Governance, long-term orientations, and sustainable capability. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigham, K.H.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Payne, G.T.; Zachary, M.A. Researching long-term orientation: A validation study and recommendations for future research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2014, 27, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Bansal, P. Social responsibility in new ventures: Profiting from a long-term orientation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1135–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Su, E.; Wang, S. When does family ownership promote proactive environmental strategy? The role of the firm’s long-term orientation. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 158, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.L.; Green, C.R.; Marty, A. Meaningful work, job resources, and employee engagement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raub, S.; Blunschi, S. The power of meaningful work: How awareness of CSR initiatives fosters task significance and positive work outcomes in service employees. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014, 55, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Kooli, C.; Alshebami, A.S.; Zeina, M.M.A.; Fayyad, S. Environmentally specific servant leadership and brand citizenship behavior: The role of green-crafting behavior and employee-perceived meaningful work. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 1097–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S.; Edinger-Schons, L.M.; Neureiter, M. Corporate purpose and employee sustainability behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 183, 963–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelson, C. “I want your shower time!”: Drowning in work and the erosion of life. Bus. Prof. Ethics J. 2005, 24, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezapouraghdam, H.; Alipour, H.; Arasli, H. Workplace spirituality and organization sustainability: A theoretical perspective on hospitality employees’ sustainable behavior. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 1583–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Nurunnabi, M.; Kim, T.H.; Jung, S.Y. The influence of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: The sequential mediating effect of meaningfulness of work and perceived organizational support. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Han, S.H. Knowledge sharing as a cornerstone for sustainability: The dual mediating roles of job engagement and meaningful work. Eur. J. Train. Dev 2024, 49, 647–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burroughs, S.M.; Eby, L.T. Psychological sense of community at work: A measurement system and explanatory framework. J. Community Psychol. 1998, 26, 509–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, A.; Rudnicki, S. Not only individualism: The effects of long-term orientation and other cultural variables on national innovation success. Cross-Cult. Res. 2019, 53, 119–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, D.R.; van Vugt, M.; Schlein, G.; Story, P.A. Identity and sustainability: Localized sense of community increases environmental engagement. Anal. Soc. Issues Public. Policy 2015, 15, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14001:2015; Environmental Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Brislin, R.W. The wording and translation of research instruments. In Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research; Lonner, W.L., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1986; pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Strathman, A.; Gleicher, F.; Boninger, D.S.; Edwards, C.S. The consideration of future consequences: Weighing immediate and distant outcomes of behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetchenhauer, D.; Rohde, P.A. Evolutionary personality psychology and victimology: Sex differences in risk attitudes and short-term orientation and their relation to sex differences in victimizations. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2002, 23, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashmos, D.P.; Duchon, D. Spirituality at work: A conceptualization and measure. J. Manag. Inq. 2000, 9, 134–145. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Patterer, A.S.; Yanagida, T.; Kühnel, J.; Korunka, C. Staying in touch, yet expected to be? A diary study on the relationship between personal smartphone use at work and work–nonwork interaction. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 94, 735–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; McGonagle, A.K. Four research designs and a comprehensive analysis strategy for investigating common method variance with self-report measures using latent variables. J. Bus. Psychol. 2016, 31, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Lee, T.; Maydeu-Olivares, A. Understanding the model size effect on SEM fit indices. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2019, 79, 310–334. [Google Scholar]

- West, S.G.; Taylor, A.B.; Wu, W. Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 209–231. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.A.; Kaniskan, B.; McCoach, D.B. The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociol. Methods Res. 2015, 44, 486–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, D. Structural equations modeling: Fit indices, sample size, and advanced topics. J. Consum. Psychol. 2010, 20, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).