Abstract

Objectives: We performed this systematic review of epidemiological studies to clarify the association between incense and mosquito-coil burning and the risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). Methods: A search of studies published through October 2024 in the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases was performed, supplemented by searches of reference lists, recent reviews, and Chinese databases. The quality of the included studies was assessed, with special attention paid to exposure assessment. Random-effects meta-analysis estimated the pooled odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) whenever applicable. Results: One cohort and twelve case–control studies were identified. Meta-analysis of one cohort study and four case–control studies with reasonable quality found an increased risk associated with incense burning during adulthood (pooled OR = 1.46; 95% CI 1.24–1.72). Five case–control studies assessed the association between exposure to incense smoke during childhood and NPC risk, and the pooled OR was 1.22 (95% CI 0.76–1.96) associated with incense burning at birth and was 1.37 (95% CI 1.10–1.71) for exposure at the age of 10 years. The pooled OR for mosquito-coil burning during adulthood was 1.31 (95% CI 0.99–1.74). None of the four previous case–control studies found an increased risk of NPC associated with mosquito-coil burning during childhood. Conclusions: Our findings suggest an increased NPC risk associated with burning incense and mosquito coils. More high-quality epidemiological studies with refined exposure assessments are warranted.

1. Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a malignancy which has fascinated generations of epidemiologists for its distinctive geographical and racial variations in incidence. NPC is rare in most parts of the world, with age-adjusted incidence rates less being than 1 per 100,000 persons per year irrespective of sex, but high incidence rates of NPC are noted in certain areas, including Southern China and Southeast Asia [1,2,3,4,5].

Although the etiology of NPC has not been completely understood, it has become increasingly clear that NPC is a multi-factorial disease resulting from the joint effects of virus infection, environmental exposures, and genetic susceptibility [1,6]. The unique spatial and ethnic clustering and a decrease in incidence since the 1970s–1980s in Chinese populations in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore [1,7,8,9,10] strongly suggest that some environmental exposures related to traditional lifestyles in these high-risk populations could have played a role in the development of NPC.

Incense burning, a traditional daily practice in Chinese households, is a powerful producer of carcinogens such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), benzene, and formaldehyde [11,12]. Incense burning has been reported to be the major contributor to PAHs in Hong Kong homes [13]. Toxicological studies have also shown mutagenic and genotoxic activities of incense smoke condensates in mammalian cells [14,15]. Burning of mosquito coils is a common practice at least several months per year in many households, especially in tropical and sub-tropical countries. Smoke from mosquito-coil burning contain considerably high levels of suspected carcinogens, including PAHs and formaldehyde [16,17]. Thus, domestic burning of incense and mosquito coils may be risk factor for respiratory tract carcinomas, including those in the upper respiratory tract, such as NPC.

Previous epidemiological studies have examined the associations between domestic burning of incense and mosquito coils and the risk of NPC, although the results remain inconsistent [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. To clarify such associations and explore the reasons underlying such inconsistency, we conducted this systematic review of available epidemiological evidence with a comprehensive literature search, quality assessment, and statistical synthesis of the available evidence. The need for future research in light of the methodological issues in previous studies is also discussed hereby.

2. Methods

This study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and is registered in the PROSPERO registry (CRD420251179504). A PRISMA checklist is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

2.1. Search Strategy

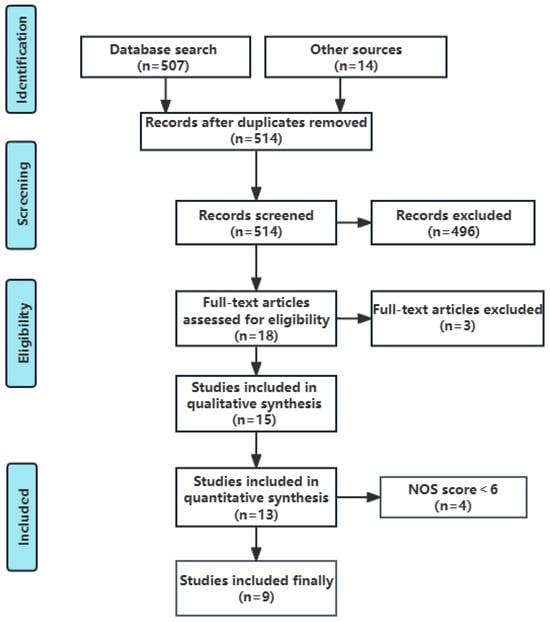

A comprehensive search of studies published through October 2024 in the MEDLINE and Embase databases was performed using the interface provided by Ovid with no language restriction. These two databases were selected because they are the most widely used major biomedical literature databases and are considered the core sources for epidemiological and clinical research, providing broad and complementary global coverage of the biomedical literature. Briefly, a combination of key words for the exposures (incense or mosquito coils) and the outcome (NPC) were used to identify relevant publications. The full electronic search strategy is presented in Supplementary Table S2. The reference lists of the identified articles and four comprehensive reviews on the epidemiology of NPC [1,5,6,28] were also reviewed to identify additional studies. A flow chart of the study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of identification and selection of studies.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Studies meeting the following criteria were included in this review: (1) case–control or cohort epidemiological studies published as original articles; (2) the studied outcome being NPC incidence rather than mortality; and (3) the association of incense or mosquito-coil burning with NPC risk being examined. In the case of multiple reports on the same population, only the most recent or informative ones were included. We only included studies which contained the minimum information necessary to estimate the odds ratio (OR) or relative risk (RR) with the reference group of non-users of incense or mosquito coils and a corresponding measure of statistical uncertainty (confidence interval [CI], standard error, variance, chi square and degree of freedom, or p value, etc.) into the meta-analysis. No additional exclusion criteria were applied.

2.3. Assessment of Study Quality

The quality of the included studies was assessed in terms of the major sources of selection bias, information bias, and confounding, with the help of checklists for appraising studies on risk factors developed by Yu and Tse [29,30,31]. The essential information regarding selection retrieved from case–control studies mainly included type (whether incident/newly diagnosed) and histological confirmation of cases, source and definition of controls, and response rate; the risk of selection bias in cohort studies was mainly assessed in terms of representativeness of the cohort and the completeness and duration of the follow-up. The retrieved information regarding exposure assessment included that on the exposure period, frequency, duration, intensity, and cumulative exposures. For cohort studies, risk of information bias on the outcome was assessed on the method of ascertainment (independent blind assessment, record linkage, or self-reported) and whether the follow-up was long enough for NPC to occur. The comparability of cases and controls (risk of confounding) was assessed by examining what potential confounding factors were considered and controlled for in the statistical analyses.

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies in meta-analyses was also used to evaluate the quality of the selected studies [32]. The NOS contains eight items which are categorized into three domains, including selection of participants, comparability between groups, and assessment of exposure (case–control studies) or outcome (cohort studies). The NOS allocates stars, ranging from zero to nine, for the quality of non-randomized studies, such that studies with a higher quality are scored with more stars.

2.4. Meta-Analysis

The software Review Manager 5.4 was used for meta-analysis. Random-effects models were used to obtain pooled estimates of effect size and 95% CIs, combining data from studies of reasonable quality with NOS scores of at least 6. Heterogeneity across studies was assessed based on chi square tests and the I2 index statistic. A low level of heterogeneity was defined as I2 ≤ 25%, accompanied by p > 0.10 in the chi square test. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of funnel plots. Given the small number of studies available on mosquito coil burning during adulthood, we did not perform subgroup analysis or meta-regression to investigate heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by removing one study at a time to examine fluctuations in the pooled effect size. A two-sided p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 507 articles were identified in MEDLINE and Embase, and 14 additional studies were identified from reference lists of reviews and articles of interest. After a careful review of titles and abstracts, and full texts if needed, 508 articles were excluded for duplication (n = 7), irrelevance (n = 496), or for not being a cohort or case–control study (n = 5). Finally, this systematic review included 13 individual studies, among which there were 12 case–control studies [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,27,33,34,35] and 1 cohort study [26]. Three case–control studies were not included in the further meta-analysis for associations between incense burning and NPC risk because two of them did not provide enough data to estimate the effect size and uncertainty [23,24], and the other one reported estimates of the effect size using participants in all of the other exposure groups instead of non-users of incense as a reference [34].

3.1. Cohort Study

Only one previous cohort study investigated the effect of incense burning on the risk of NPC [26]. This cohort study included 61,320 Singapore Chinese aged 45–74 years, including 6144 non-users, 7997 former users, and 47,179 current users of incense, who were recruited between 1993 and 1998 and followed up through 2005. Among current users, 92.7% were daily users and 83.9% had used incense for over 40 years. The study quality of this study was reasonably good, with an NOS quality score of 8, given the methodological strengths, including the representativeness of the original cohort (population-based including 85% of eligible individuals), complete follow-up (99.7%), comprehensive and prospective exposure assessment, objective assessment of outcome (91.3% histologically confirmed), and efforts to control for potential confounders (adjusting for age, gender, dialect group, education, body mass index, smoking, drinking, dietary items, and parity for women).

3.2. Case–Control Studies

The 12 identified case–control studies were published between 1966 and 2021, among which 11 were conducted in Chinese populations of different geographic areas, including Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore, and the remaining one was conducted in a Filipino population. The number of cases ranged from 47 to 2533 across individual studies. Only four studies adjusted a set of various potential confounders in multivariate analyses. The majority of these studies obtained NOS quality scores ranging from 5 to 8, except for the earliest study published in 1966, which had a score of 2 (Supplementary Table S3). More detailed characteristics of the 12 case–control studies are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of identified case–control studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics related to validity of identified case–control studies.

Eleven out of the twelve studies assessed exposure to incense or mosquito-coil smoke during adulthood based on usual or recent practice (four for incense burning only, one for mosquito-coil burning only, and six for both). Three of the twelve studies, all by research group of Yu et al., also assessed exposures at the age of 10 years and at birth [18,19,20]. One recent study assessed exposures at the ages of 10, 18, and 30 years [27]. One study assessed exposures to incense smoke during childhood, but did not further clarify the specific period [34]. Seven studies reported frequency data, but only one out of the twelve case–control studies considered other aspects of exposure, such as intensity and duration (Table 3) [21].

Table 3.

Exposure assessment in the included studies.

3.2.1. Incense Burning During Adulthood

In the only cohort study, a total of 175 NPC cases were diagnosed during the follow-up; however, in the follow-up period (12 years at most), the association between incense burning and NPC risk were examined based on multiple exposure indicators, and no statistically significant associations were found. The adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for NPC were 0.7 (95% CI: 0.4–1.4) in former users and 0.8 (95% CI 0.5–1.3) for current uses of incense, using never-users as the reference group. No exposure-response relations were observed. The HRs were 0.7 (95% CI: 0.3–1.5) for less than daily current use, 1.0 (95% CI: 0.6–1.7) for daily use for 40 years or less, and 1.0 (95% CI: 0.7–1.4) for daily use for over 40 years.

Ten previous case–control studies evaluated the associations between incense burning during adulthood and NPC risk. Among these, three studies simply reported the results as negative or not statistically significant [20,23,24], and one study reported estimates of RRs without using non-users of incense as a reference [34].

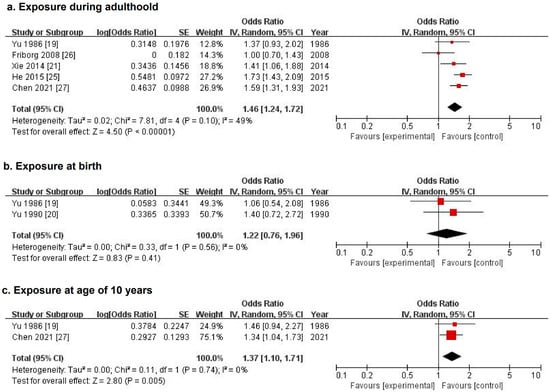

Meta-analysis combining five studies with NOS scores of at least 6 generated a pooled OR of 1.46 (95% CI: 1.24, 1.72) in random-effects model (Figure 2a). The heterogeneity tests suggest moderate heterogeneity across studies (p = 0.10, I2 = 49%). The funnel plot with a limited number of studies suggests no substantial publication bias (Supplementary Figure S1), and the pooled OR did not substantially change in the sensitivity analysis excluding one study at a time (Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Forest plots of pooled odds ratios for nasopharyngeal carcinoma associated with incense burning during adulthood (a), at birth (b), and at the age of 10 years (c) in previous case–control studies.

3.2.2. Incense Burning During Childhood

Five previous case–control studies, including three studies from the research group of Yu et al., examined the association between incense burning at early ages and NPC risk in Chinese populations in different areas. None of them found statistically significant associations. For exposure at birth, one of these three studies only reported the results as non-significant (p = 0.14). The pooled OR for NPC risk associated with incense burning at birth combining two studies was 1.22 (95% CI 0.76–1.96) (Figure 2b). For exposure at the age of 10 years, two studies described the results as non-significant (p = 0.34 and p = 0.23). The pooled OR for NPC associated with incense burning at the age of 10 years combining the other two studies was 1.37 (95% CI 1.10–1.71) (Figure 2c).

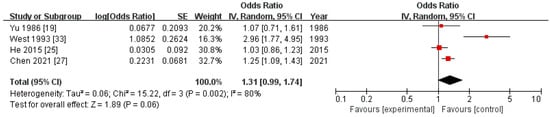

3.2.3. Mosquito-Coil Burning During Adulthood

Six previous case–control studies reported associations between mosquito-coil burning during adulthood and NPC risk. A meta-analysis of the four studies with NOS scores of at least 6 generated a pooled OR of 1.31 (95% CI 0.99–1.74) in a random-effects model, with high heterogeneity across studies (p = 0.002, I2 = 80%) (Figure 3). The pooled OR did not substantially change in the sensitivity analysis removing one study at each time (Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 3.

Forest plots of pooled odds ratios for nasopharyngeal carcinoma associated with mosquito-coil burning during adulthood in previous case–control studies.

3.2.4. Mosquito-Coil Burning During Childhood

The three case–control studies from the research group of Yu et al. examined the associations between mosquito-coil burning at early ages and NPC risk, and none of them reported statistically significant findings. Another recent study reported an OR of 0.84 (95% CI 0.75-0.95) for NPC risk associated with mosquito-coil burning in summer at the age of 10 years [27].

4. Discussion

This updated systematic review of existing epidemiological studies investigates the associations of incense and mosquito-coil burning with NPC risk. The results reveal an increased risk of NPC associated with incense burning during both adulthood and childhood periods and mosquito-coil burning during adulthood, but evidence regarding mosquito-coil burning during childhood remains limited.

The carcinogenic potentials of emissions from incense and mosquito-coil burning have been intensively documented in the previous literature on environmental chemistry and toxicology. Incense smoke is an important source of residential indoor PMs, including those less than 2.5 μm in the diameter (PM2.5), which pose the largest health risks in all types of PMs [11,36,37,38,39,40]. It has been reported that incense burning produced PM over 45 mg/g burned, which was dramatically higher than that burned for cigarettes (10 mg/g) [41]. Incense burning also generates various types of VOCs, including benzene, PAHs, and formaldehyde, which are confirmed or probable carcinogens to humans [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. Burning of mosquito coils is also a powerful producer of carcinogenic agents, such as PAHs and formaldehyde [16,17]. The emission of PM2.5 mass from burning one mosquito coil was as high as that from burning 75–137 cigarettes. Burning one mosquito coil would release the same amount of formaldehyde as from burning 51 cigarettes [16]. Toxicological studies have shown that PM extracts from incense smoke is mutagenic in the Ames Salmonella test with TA98 and activation, and the genotoxicity of certain incense smoke condensates in mammalian cells may be even higher than that of tobacco smoke condensates [11,14,15]. Given the fact that inhalation is the primary route of exposure to smokes from incense and mosquito-coil burning, burning incense and mosquito coils may be an important risk factor for malignancies in the respiratory tract, including NPC.

The pooled results of meta-analysis in the present study showed an increased risk of NPC associated with incense burning. The inconsistency between findings from previous studies and the pooled estimates may be explained by differences in study design, population characteristics, exposure assessment, control of potential confounding, and chance. Notably, the findings should be interpreted with caution, given the considerable methodological limitations in previous studies. However, restricting our meta-analysis to studies with NOS scores of at least 6 diminished this influence to some extent. No associations between mosquito-coil burning during childhood and NPC risk were indicated in previous studies. It is possible to explained this by non-differential exposure misclassification regarding exposure in early life, which would have biased the results towards null, as well as the fact that burning mosquito coils is only an occasional practice in selective seasons, unlike incense burning, which is often a long-term daily practice.

Epidemiological studies on the health effects of environmental pollutants need accurate exposure assessments. An inaccurate exposure assessment can cause exposure misclassification, which may result in biased results and/or loss of study power, in addition to a failure in documenting a clear exposure–response relationship. Because incense and mosquito-coil burning was not the primary risk factor of interest in previous case–control studies, the exposure assessment methods concerning burning incense and mosquito coils were quite crude, e.g., only dichotomized to ever/never-exposed categories or just the frequency of burning. Only one of previous case–control studies considered other important aspects of exposure [21]. In addition, these studies only used the usual (recent) burning practice for exposure assessment, although several studies also assessed exposure at early ages. Changes of behavior over time or cumulative exposures were not considered. Even in the cohort study of reasonable study quality, the exposure assessment was based on incense burning practice at baseline only and did not adequately reflect lifetime exposure. Lack of accurate exposure assessment, particularly if non-differential, in previous studies may have diluted the observed associations between domestic incense and mosquito-coil burning and NPC risk.

Since NPC is a relatively rare disease, the cohort study design does not seem to be an efficient method of investigation for the risk factors of NPC. The reasonably large cohort study among a Singapore Chinese population only observed 175 NPC cases during follow-up and might not have adequate statistical power. Particularly, the limited length of follow-up might not have allowed for all NPC cases to occur. Case–control, especially in high-risk regions, may continue to be the major study design for investigating the etiology of NPC due to its feasibility and efficiency. The potential risk of selection bias in this systematic review needs to be discussed. A comprehensive searching strategy has been adopted to identify all of the published studies reporting the associations of interest. Because only a limited number of studies were specifically designed to investigate the associations between incense burning and NPC risk, and because the majority of these studies were published in earlier periods, several included studies were not identified using electronic searching, suggesting that electronic databases may not be sufficient for identifying studies dating very far back. Although the original authors were also contacted for detailed information when the published results were not sufficient for meta-analysis, no additional information was obtained, mainly because the data records were destroyed after the completion of their studies. The results of the meta-analysis are probably prone to publication bias because many studies with lower NOS scores but that found no associations were not included in the meta-analysis.

The validity of the results of the meta-analysis could be affected by those from primary studies. Although nine of the included case–control studies reported considerably high response rates, the remaining three did not report response rates, posing a certain risk of selection bias. Three studies did not mention whether recruited cases were incident or prevalent. If incense or mosquito-coil burning is associated with poor survival in NPC patients, recruiting prevalent cases might have resulted in underestimating the effects of incense or mosquito-coil burning because those with poor survival who were more likely to burn incense or mosquito coils might have been missed. Seven studies used hospital-based controls, among which, one even used cancer patients as controls [22]. If control participants were diagnosed with diseases associated with incense or mosquito-coil burning, the results might have been biased, for which the direction away from the true estimates depends on the specific diseases which the control participants were diagnosed with. If incense or mosquito-coil burning is associated with an increased risk for the diseases which control participants had, the effects of incense or mosquito-coil burning might have been underestimated. However, if control participants were affected by some specific diseases (e.g., asthma), they were likely to avoid exposures to smoke, which might have resulted in overestimating the effects of incense or mosquito-coil burning on NPC risk. Community-based controls were used in six of the included studies. Two studies also used friend or neighborhood controls, and it was possible that this caused overmatching and moved the estimates towards the null. In addition, even when community-based controls were used, the risk of misclassification of outcomes would be minor, given that NPC is rare in the general population. Although the same methods of exposure assessment were used for cases and controls in previous studies, there remains certain risk of misclassification in previous case–control studies because of the retrospective nature of such designs. However, it was probably non-differential, since incense burning and mosquito-coil burning are not well-established risk factors for NPC; hence, the resulting bias, if any, would have been towards the null. It is notable that limited efforts have been made to control for potential confounders in most of previous studies. Since incense burning is a traditional practice in some Asian populations, it is probably correlated with some other types of traditional lifestyle. Failure to control for potential confounding effects from other risk factors associated with traditional lifestyle may have compromised the validity of the results, leading to over- or under-estimated effects. Overall, the results of the meta-analysis in this systematic review were possibly subject to bias as a result of the inaccurate magnitude of associations reported in the original studies that could have arisen from various sources of bias in those studies. Notably, the limited number of eligible studies, most of which were conducted several decades ago, reflects the current scarcity of epidemiological research on this topic. In addition, the evidence included in this systematic review and meta-analysis was primarily derived from studies conducted in East Asian and Southeast Asian populations, which may not be generalized to other populations. These facts highlight a substantial research gap and the need for updated large-scale studies using contemporary study designs and exposure assessment methods.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, although the synthesized results of previous studies suggest an increased risk of NPC associated with burning incense and mosquito coils, existing evidence from epidemiological studies remains far from enough to accurately assess such associations. We highlight the need for refined exposure assessment methods, increased efforts to control for confounders, and increased sample sizes for adequate study power in future investigations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/greenhealth1030023/s1. Table S1: PRISMA checklikst; Table S2: Literature searching in Ovid system; Table S3: Newcastle–Ottawa quality scores of the included case–control studies; Figure S1: Funnel plot showing the log odds ratios versus the standard errors of log odds ratios for the association between incense burning during adulthood and the risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma; Figure S2: Sensitivity analysis by removing one study at each time for the association between incense burning during adulthood and the risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma; Figure S3: Sensitivity analysis by removing one study at each time for the association between mosquito-coil burning during adulthood and the risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-H.X. and I.T.-S.Y.; methodology, S.-H.X., L.A.T. and I.T.-S.Y.; software, J.-X.X. and S.-H.X.; validation, J.-X.X. and S.-H.X.; formal analysis, J.-X.X. and S.-H.X.; investigation, J.-X.X. and S.-H.X.; resources, S.-H.X. and I.T.-S.Y.; data curation, J.-X.X. and S.-H.X.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-X.X. and S.-H.X.; writing—review and editing, L.A.T. and I.T.-S.Y.; visualization, J.-X.X. and S.-H.X.; supervision, S.-H.X.; project administration, S.-H.X.; funding acquisition, S.-H.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Startup Fund for Scientific Research of Fujian Medical University (grant number XRCZX2021024) and the Swedish Cancer Society (grant number 22-2038).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All of the included studies were retrieved from the online databases MEDLINE and Embase. Template data collection forms and data extracted from the included studies are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chang, E.T.; Adami, H.-O. The Enigmatic Epidemiology of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2006, 15, 1765–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busson, P.; Keryer, C.; Ooka, T.; Corbex, M. EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinomas: From epidemiology to virus-targeting strategies. Trends Microbiol. 2004, 12, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Rumgay, H.; Li, M.; Cao, S.; Chen, W. Nasopharyngeal Cancer Incidence and Mortality in 185 Countries in 2020 and the Projected Burden in 2040: Population-Based Global Epidemiological Profiling. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2023, 9, e49968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Cheng, W.; Li, H.; Liu, X. The global, regional, national burden of nasopharyngeal cancer and its attributable risk factors (1990–2019) and predictions to 2035. Cancer Med. 2022, 11, 4310–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.T.; Ye, W.; Zeng, Y.-X.; Adami, H.-O. The Evolving Epidemiology of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2021, 30, 1035–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.-H.; Qin, H.-D. Non-viral environmental risk factors for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A systematic review. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2012, 22, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, L.A.; Yu, I.T.S.; Mang, O.W.K.; Wong, S.L. Incidence rate trends of histological subtypes of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Hong Kong. Brit. J. Cancer 2006, 95, 1269–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Chia, K.S.; Chia, S.E.; Reilly, M.; Tan, C.S.; Ye, W. Secular trends of nasopharyngeal carcinoma incidence in Singapore, Hong Kong and Los Angeles Chinese populations, 1973–1997. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 22, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.W.M.; Foo, W.; Mang, O.; Sze, W.M.; Chappell, R.; Lau, W.H.; Ko, W.M. Changing epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Hong Kong over a 20-year period (1980–99): An encouraging reduction in both incidence and mortality. Int. J. Cancer 2003, 103, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.; Shen, Y.-C.; Cheng, C.-C.; Hong, R.-L.; Chang, C.-J.; Cheng, A.-L. Difference in the Incidence Trend of Nasopharyngeal and Oropharyngeal Carcinomas in Taiwan: Implication from Age-Period-Cohort Analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2006, 15, 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfroth, G.; Stensman, C.; Brandhorst-Satzkorn, M. Indoor sources of mutagenic aerosol particulate matter: Smoking, cooking and incense burning. Mutat. Res. Toxicol. 1991, 261, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.M.; Tang, C.S. Characterization and aliphatic aldehyde content of particulates in Chinese incense smoke. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1994, 53, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, L.C.; Matsushita, H.; Ho, J.H.C.; Wong, M.C.; Shimizu, H.; Mori, T.; Matsuki, H.; Tominaga, S. Carcinogens in the indoor air of Hong Kong homes: Levels, sources, and ventilation effects on 7 polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons. Environ. Technol. 1994, 15, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, R.E. Mutagenic activity of incense smoke inSalmonella typhimurium. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1987, 38, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Lee, H. Genotoxicity and DNA adduct formation of incense smoke condensates: Comparison with environmental tobacco smoke condensates. Mutat. Res. Toxicol. 1996, 367, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Hashim, J.H.; Jalaludin, J.; Hashim, Z.; Goldstein, B.D. Mosquito coil emissions and health implications. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003, 111, 1454–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.-Y.; Lin, J.-M. Aliphatic aldehydes and allethrin in mosquito-coil smoke. Chemosphere 1998, 36, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.C.; Mo, C.C.; Chong, W.X.; Yeh, F.S.; Henderson, B.E. Preserved foods and nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case-control study in Guangxi, China. Cancer Res. 1988, 48, 1954–1959. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.C.; Ho, J.H.; Lai, S.H.; Henderson, B.E. Cantonese-style salted fish as a cause of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Report of a case-control study in Hong Kong. Cancer Res. 1986, 46, 956–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.C.; Garabrant, D.H.; Huang, T.B.; Henderson, B.E. Occupational and other non-dietary risk factors for nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Guangzhou, China. Int. J. Cancer 1990, 45, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.-H.; Yu, I.T.-S.; Tse, L.-A.; Mang, O.W.-k.; Yue, L. Sex difference in the incidence of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Hong Kong 1983–2008: Suggestion of a potential protective role of oestrogen. Eur. J. Cancer 2013, 49, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturton, S.D.; Wen, H.L.; Sturton, O.G. Etiology of cancer of the nasopharynx. Cancer 1966, 19, 1666–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.M.; Chen, K.P.; Lin, C.C.; Hsu, M.M.; Tu, S.M.; Chiang, T.C.; Jung, P.F.; Hirayama, T. Retrospective Study on Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma2. JNCI-J. Natl. Cance R. Inst. 1973, 51, 1403–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.P.; Gourley, L.; Duffy, S.W.; Esteve, J.; Lee, J.; Day, N.E. Preserved foods and nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case-control study among singapore chinese. Int. J. Cancer 1994, 59, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.-Q.; Xue, W.-Q.; Shen, G.-P.; Tang, L.-L.; Zeng, Y.-X.; Jia, W.-H. Household inhalants exposure and nasopharyngeal carcinoma risk: A large-scale case-control study in Guangdong, China. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friborg, J.T.; Yuan, J.M.; Wang, R.; Koh, W.P.; Lee, H.P.; Yu, M.C. Incense use and respiratory tract carcinomas: A prospective cohort study. Cancer 2008, 113, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chang, E.T.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, G.; Huang, Q.-H.; Xie, S.-H.; Cao, S.-M.; et al. Residence characteristics and risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in southern China: A population-based case-control study. Environ. Int. 2021, 151, 106455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.C.; Yuan, J.-M. Epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2002, 12, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, I.T.; Tse, S.L. Workshop 10-appraising a study on risk factors or aetiology. Hong Kong Med. J. 2013, 19, 50–51. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, I.T.; Tse, S.L. Workshop 5-Sources of bias in cohort studies. Hong Kong Med. J. 2012, 18, 137–138. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, I.T.; Tse, S.L. Workshop 4-Sources of bias in case-referent studies. Hong Kong Med. J. 2012, 18, 46–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.; Hildesheim, A.; Dosemeci, M. Non-viral risk factors for nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the philippines: Results from a case-control study. Int. J. Cancer 1993, 55, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugaratnam, K.; Tye, C.Y.; Goh, E.H.; Chia, K.B. Etiological factors in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A hospital-based, retrospective, case-control, questionnaire study. IARC Sci. Publ. 1978, 20, 199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Geser, A.; Charnay, N.; Day, N.E.; Ho, H.C. Environmental factors in the etiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Report on a case-control study in Hong Kong. IARC Sci. Publ. 1978, 20, 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Jetter, J.J.; Guo, Z.; McBrian, J.A.; Flynn, M.R. Characterization of emissions from burning incense. Sci. Total Environ. 2002, 295, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.-C.; Chu, C.-C.; Wu, Y.-S.; Fu, P.P.-C. Emission characters of particulate concentrations and dry deposition studies for incense burning at a Taiwanese temple. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2002, 18, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.-C.; Chang, C.-N.; Wu, Y.-S.; Yang, C.-J.; Chang, S.-C.; Yang, I.L. Suspended particulate variations and mass size distributions of incense burning at Tzu Yun Yen temple in Taiwan, Taichung. Sci. Total Environ. 2002, 299, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.-C.; Chang, C.-N.; Chu, C.-C.; Wu, Y.-S.; Pi-Cheng Fu, P.; Chang, S.-C.; Yang, I.L. Fine (PM 2.5), coarse (PM 2.5–10), and metallic elements of suspended particulates for incense burning at Tzu Yun Yen temple in central Taiwan. Chemosphere 2003, 51, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brauer, M.; Hirtle, R.; Lang, B.; Ott, W. Assessment of indoor fine aerosol contributions from environmental tobacco smoke and cooking with a portable nephelometer. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2000, 10, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannix, R.C.; Nguyen, K.P.; Tan, E.W.; Ho, E.E.; Phalen, R.F. Physical characterization of incense aerosols. Sci. Total Environ. 1996, 193, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.-T.; Lin, S.-T.; Lin, T.-S.; Hong, W.-L. Characterization of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emissions in the particulate phase from burning incenses with various atomic hydrogen/carbon ratios. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 414, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Lee, S.; Ho, K.; Kang, Y. Characteristics of emissions of air pollutants from burning of incense in temples, Hong Kong. Sci. Total Environ. 2007, 377, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoental, R.; GlBbard, S. Carcinogens in Chinese Incense Smoke. Nature 1967, 216, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoukian, A.; Quivet, E.; Temime-Roussel, B.; Nicolas, M.; Maupetit, F.; Wortham, H. Emission characteristics of air pollutants from incense and candle burning in indoor atmospheres. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 4659–4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-C.; Chang, F.-H.; Hsieh, J.-H.; Chao, H.-R.; Chao, M.-R. Characteristics of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and total suspended particulate in indoor and outdoor atmosphere of a Taiwanese temple. J. Hazard. Mater. 2002, 95, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.M.; Wang, L.H. Gaseous aliphatic aldehydes in Chinese incense smoke. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1994, 53, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.S.; Lin, J.M. Gaseous Aliphatic Aldehydes in Smoke from Burning Raw Materials of Chinese Joss Sticks. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1996, 57, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, S.S.H.; Yu, J.Z. Concentrations of formaldehyde and other carbonyls in environments affected by incense burning. J. Environ. Monit. 2002, 4, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Jetter, J.J.; McBrian, J.A. Rates of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Emissions from Incense. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2004, 72, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).