Abstract

We survey the recent developments on quantum invariants of 3-manifolds and links: and . They are q-series invariants originated from mathematical physics, inspired by the categorification of a numerical quantum invariant—the Witten–Reshetikhin–Turaev (WRT) invariant—of 3-manifolds. They exhibit rich features, for example, quantum modularity, infinite-dimensional Verma module structures, and knot–quiver correspondence. Furthermore, they have connections to the 3d-3d correspondence and other topological invariants. We also provide a review of an extension of the above series invariants to Lie superalgebras.

1. Introduction

Topological quantum field theories (TQFTs) have been a fruitful source of interaction between physics and topology. From one to four dimensions, TQFTs have provided physical realizations of topological invariants or predicted new ones. Examples include the colored Jones polynomials and HOMFLY-PT polynomials of links [1,2], as well as the Donaldson and Seiberg–Witten invariants of smooth four-manifolds [3,4]. In three dimensions, Chern–Simons TQFT predicted the Witten–Reshetikhin–Turaev (WRT) invariant of 3-manifolds [2]. The introduction of this invariant motivated a rigorous construction via the quantum group and its representations [5,6] (see [7] for a review). This established a gateway into quantum topology from the mathematics side.

On the mathematics side, TQFT was axiomatized in [8,9] (see [10] for a review), and its breadth and depth have since been greatly enriched. Axiomatic TQFT synthesizes topology, quantum algebra, representation theory, and category theory. One direction of advancement in TQFTs has been the construction of extended TQFTs, which introduced higher categories into the scene [11,12,13]. There has also been progress in the classification of such TQFTs [14]. Another line of development involves the construction of non-semisimple TQFTs associated with various quantum groups. Non-semisimple invariants of manifolds first appeared through the ADO polynomials of links [15] and their quantum group formulation in [16]. In three dimensions, this type of TQFT utilizes non-semisimple categories [17] and the modified quantum dimension [18,19]. A non-semisimple TQFT has led to a new quantum invariant of links and 3-manifolds, called the CGP invariant [20]. One of the advantages of non-semisimple invariants is that they can distinguish manifolds that semisimple invariants cannot, and they yield nonzero results in cases where semisimple invariants vanish. Furthermore, the underlying quantum groups of these TQFTs have been generalized to quantum supergroups [21,22,23].

Another rich source of interaction between physics and topology is the categorification program [24] (see [25,26,27,28] for reviews). Not only has it deepened the understanding of quantum invariants of manifolds, but it has also provided powerful new tools. In the case of link polynomials, many have been shown to be graded Euler characteristics of homology theories. For example, the Alexander polynomial, Jones polynomial, and HOMFLY-PT polynomial are the Euler characteristics of knot (or link) Floer homology [29,30,31], Khovanov (co)homology [32,33], and Khovanov–Rozansky homology [34], respectively. Furthermore, the quantum group itself has been categorified. This, combined with the quantum Weyl group, has led to a different approach to computing link polynomials [35,36].

From the physics perspective on categorification, string theory has played a vital role. Beginning with knot polynomials [37], the first physical realization of knot homology was achieved in [38]. It provided physical interpretations of Khovanov homology, Khovanov–Rozansky homology [39], and knot Floer homology. Furthermore, it predicted the existence of a categorification of the HOMFLY-PT polynomial—an unexpected development from the mathematics side [40]. In the case of colored HOMFLY homology, a detailed investigation for torus links revealed structural properties and differentials [41]. Additionally, an application of a spectral sequence to a four-dimensional supersymmetric quantum field theory (QFT) was accomplished. Subsequently, a gauge-theoretic realization of Khovanov homology using a brane system in string/M-theory was introduced in [42] (see [43,44] for reviews).

A major challenge of the categorification program has been categorifying the WRT invariant of closed 3-manifolds Y. The invariant is defined at roots of unity and does not exhibit a manifest integrality property that would allow it to be interpreted as the Euler characteristic of a homology theory. A strategy for its categorification was proposed in [45,46]. On the physics side, a three-dimensional supersymmetric quantum field theory (QFT) arising from six dimensions predicted the existence of a power series with integral coefficients associated with the WRT invariant [47,48]. This q-series, denoted by , is labeled by structures b on Y, representing a vast generalization of [49]. Notably, the appearance of structures is novel, as the original definition of the WRT invariant does not involve such structures. Moreover, itself is a topological invariant of Y, implying that there are multiple invariants associated with Y distinguished by the choice of b. It was conjectured that the WRT invariant of Y can be expressed as a linear combination of the invariants. This decomposition was proven for a particular class of 3-manifolds in [50].

Importantly, it was also conjectured that is the graded Euler characteristic of a homology theory that would provide the desired categorification of the WRT invariant. From the physics point of view, is the nonperturbative partition function for complex Chern–Simons theory on Y.

A generalization to 3-manifolds with torus boundary—particularly plumbed knot complements—was achieved in [51]. This led to the definition of a two-variable series invariant, , for the complement of a knot K. The series provided access to for closed manifolds beyond plumbed manifolds via Dehn surgery formulas. Following the introduction of the q-series and , there has been extensive development. For example, there are extensions to higher-rank Lie groups [52]; the discovery of a quantum modularity property [53,54]; connections to other (geometric) topological invariants [55,56]; an R-matrix formulation and generalizations to links, denoted by [57,58,59]; and a quiver formulation [60].

Motivated by , a variety of extensions of and have been introduced. For example, a two -variable refinement for negative definite plumbed 3-manifolds was defined in [61]. This invariant originates from lattice cohomology theory and reduces to when . The quantum modularity aspects of were explored in [62]. A generalization of to knot complements was presented in [63]. Another extension was introduced in [64], where a set of formal series denoted by is associated with higher-rank Lie groups and generalized structures. It was shown that among series, the one invariant under the Weyl group action coincides with , thereby demonstrating the uniqueness of .

An algebraic extension, namely, a q-series invariant associated with Lie superalgebras, was introduced in [65]. In the case of , the series was denoted by and carries two labels . For a class of 3-manifolds called plumbed manifolds , it was shown that decomposes a quantum invariant of constructed in [23]. From the physics viewpoint, string/M-theory predicted the existence of the topological invariant . Furthermore, the super was generalized to plumbed knot complements in [66], leading to a three-variable series that exhibits distinctive features compared with .

In this review article, we provide an overview of the developments on q-series invariants and , and the latter’s link generalization in terms of various aspects of these invariants. Moreover, we also survey their extensions to supergroups.

- Organization of this paper.

In Section 2 we describe the series invariant for closed 3-manifolds and its underlying physics, properties, effects of line operator insertions, and relations to other invariants.

In Section 3 we describe the series invariant for complement of links, its R-matrix formulation, surgery formulas, and its connections to the ADO polynomials and quiver theory.

In Section 4 we review the series invariant super associated with a Lie superalgebra for closed 3-manifolds and its underlying physics.

Finally, in Section 5 we summarize a three-variable series for complements of plumbed knots and its relation to the super . We list open problems for future directions.

2. Series Invariant for Closed 3-Manifolds

As mentioned in the Introduction, a major challenge in the categorification program has been categorifying the WRT invariant of 3-manifolds. The goal is to define homology groups for closed, oriented 3-manifolds whose graded Euler characteristic equals the WRT invariant or an invariant closely related to it. This homology theory can be regarded as a 3-manifold analogue of Khovanov homology. A physics approach to the problem was introduced in [47,48]. Specifically, generalizing the result of [49], the existence of a q-series invariant for closed oriented 3-manifolds Y denoted by exhibiting integrality properties was conjectured in [47,48]. For Y with (i.e., ) and every structure b,

It is a convergent q-series in the interior of the complex unit disc. It is conjectured that the WRT invariant of Y decomposes in terms of .

Conjecture 1.

([48]). Let Y be a closed 3-manifold with . Let be the set of structures on Y, with the action of by conjugation. Set

The radial limit exists, and in this limit, the WRT invariant of Y decomposes as a linear combination of :

where is if and is 1 otherwise; is the linking pairing.

Furthermore, is supposed to admit a categorification

These homology groups are claimed to be the desired homology groups categorifying the WRT invariant.

2.1. Plumbed Manifolds

We first review a class of 3-manifolds called plumbed manifolds. A closed oriented plumbed three-manifold is described by a weighted graph . It consists of vertices and edges. The former carry integer weights , whereas the latter carry weight 1. These plumbing graph data are summarized by an adjacency matrix B, which is symmetric and, its size is set by the number of vertices s of :

We assume that plumbing graphs are trees. An interpretation of is that each vertex represents an -bundle over whose Euler number is . The edge between two vertices represents gluing two -bundles by cutting out a from each base space and attaching two . Another useful interpretation is a surgery link obtained by replacing a vertex by a -framed unknot and an edge by a Hopf link between two unknots. Hence, is always a tree link. Applying Dehn surgery (see Section 3.5 for a review) on results in the same Y. The first homology of is

In case B is nondegenerate, is a rational homology sphere. When B is negative definite, we call a negative definite plumbed 3-manifold.

A plumbed 3-manifold can be presented by different plumbing graphs that are related by a set of Kirby–Neumann moves in Figure 1. In [67,68,69], it was shown that two plumbing graphs and represent the same 3-manifolds if and only if they are related by a sequence of these moves.

Figure 1.

Kirby–Neumann moves on plumbing trees. Move 1: blow up/down (top); move 2: absorption/desorption (middle); move 3: fusion/fission (bottom).

A well-known class of plumbed 3-manifold is Seifert fibered manifolds. Their graphs are star-shaped; they consist of one central vertex of degree (the degree of a vertex is the number of legs emanating from it; the degree two case is a Lens space (a special Seifert fibered manifold)) and a finite number of legs attached to the central vertex. The degree of the vertices on the legs is one or two. These legs are singular fibers of the manifold. The graph data can be summarized in the following way.

where e is the Euler number, b is the weight of the central vertex, n is the number of singular fibers, and are called Seifert invariants. Their continued fraction expansions yield the weights of the vertices on the legs.

where s depends on the singular fibers. A vertex attached to the central vertex has weight , and the last vertex on the same leg has weight .

For negative definite plumbed 3-manifolds, , and . It was shown in [70] that the sign of e determines the positive or negative definiteness of the manifolds (the converse also holds). In the case where (1) is trivial, i.e., , is an integral homology three-sphere . In terms of Seifert data, the condition is

This subclass of manifolds is denoted by .

- structures

We next describe structures on plumbed manifolds [51]. A structure on an oriented 3-dimensional manifold Y is a lift of the structure group of its tangent bundle to

They always exist for low-dimensional manifolds (dimension ). And they form an affine space over ; in other words, difference between two structures corresponds to a 2-cocycle. To characterize structures of in terms of , we first look at a closed 4-manifold X bounded by ().

structures on X can be canonically identified with characteristic vectors :

And , where the Poincare duality was used, s is the number of vertices of , and Vert is a set of its vertices. We have

where is a vector whose components are weights for Vert. From above, we have a natural identification

In order to pass to , we analyze the long exact sequence of cohomology groups for and X,

This entails that . Moreover,

From (2), we get a canonical identification (a proof that the identification is natural can be found in Section 4.2 in [51]):

This is in turn identified with

where is the degree of Vert.

2.2. The Series Invariant

Let be a (weakly) negative definite plumbed manifold with (i.e., ) and B be its adjacency matrix, equivalently a linking matrix of (the definition of weakly in the parenthesis is in Section 4.3 of [51]; we primarily deal with negative definite plumbed manifolds in this review). The colored Jones polynomial of is given by [48]

where E denotes a set of edges of and . The WRT invariant of is

where are one-vertex plumbing graphs whose framings are and is the number of positive/negative eigenvalues of B.

Remark 1.

The invariant in (3) is its Dehn surgery formulation.

From (3), the q-series of can be obtained as follows [48] (see Appendix A of [48] for the derivation).

where

where is the number of components of and is the principal value prescription for the complex contour integral. From the perspective of the surgery link , (4) can be viewed as a surgery formula on a tree link (a tree link is a link consisting of unknots, and their linkings are all Hopf links).

Remark 2.

Negative definite refers to B being negative definite (i.e., all its eigenvalues are negative).

Proposition 1

([51]). in (4) is invariant under the Kirby–Neumann moves in Figure 1.

Theorem 1

([50]). Conjecture 1.1 holds for negative definite plumbed 3-manifolds.

Remark 3.

For plumbed manifolds having (i.e., a graph containing a loop), (4) needs a modification [71].

Remark 4.

A closely related graphs to plumbing graphs are splice diagrams. They can be converted into each other. The splice diagrams are useful for revealing the connection of to algebraic geometry. The series for splice diagrams was analyzed in [72].

We next describe the physics underlying (4).

- Physics Story

The physical prediction for originates from a brane system in M-theory given by the following setup [48]:

where Y is a compact Riemannian manifold and exists if Y is a Seifert fibered manifold. The appearance of Calabi–Yau 3-fold is required by supersymmetry preservation for any choice of metric on Y due to McLean’s theorem. Furthermore, Taub-NUT space is necessary to preserve supersymmetry along world-volume directions and the rotational symmetries . is in the shape of a cigar whose circle part is the M-theory circle. The world-volume theory on the stack of M5 branes is theory. Dimensional reduction on Y gives rise to SCFT on , denoted by . The symmetries give rise to the homological and quantum gradings on the BPS Hilbert space of . The boundary conditions b on provide the torsion grading. Therefore, we arrive at the existence of the triply graded homology group theory:

| 11D Spacetime | × | × | Taub-NUT | ||

| N M5 | × | Y | × | ||

| Symmetries | × |

The homological grading is denoted by j, and the shift factor in the quantum grading i is related to the d-invariant (the correction term) of the Heegaard–Floer homology [56]. In the case where Y is a Seifert manifold, there is an additional grading.

Gluing two copies of the solid torus along their common boundary , we can create . An important quantity that represents theory on is the superconformal index of ; equivalently, its supersymmetric partition function [48] is

is the BPS sector of the Hilbert space, equivalently the Q-cohomology of all physical operators, i.e.,F: the fermion number; R: the generator of symmetry; : the Cartan generator of the isometry of .

Furthermore, we let

where b is the supersymmetric boundary condition on ; the subscript q means that as one traverses , rotates around its symmetry axis by .

By the correspondence [73,74],

is the nonperturbative partition function of the complex Chern–Simons theory on Y.

It was conjectured that and its orientation-reversed version can be combined to form .

Conjecture 2

([48]). The superconformal index of admits the following factorization:

where is an analytic continuation of outside of a complex unit disc .

This conjecture has a generalization by introducing an additional parameter t; hence, , which is called the topologically twisted index (the above conjecture can be recovered by setting ). This generalized conjecture was verified for in [48].

- Examples (see [53] for additional examples)

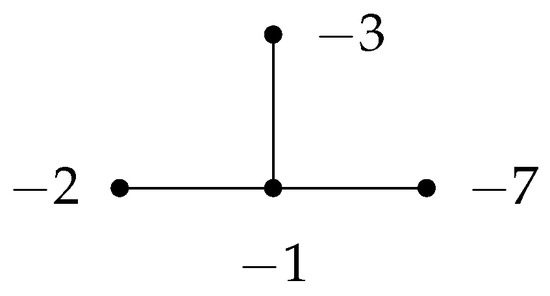

. Using the method described in Section 2.1, its plumbing graph (Figure 2) is given by

Figure 2.

A plumbing graph of Y.

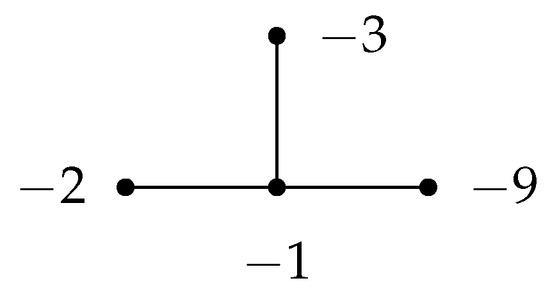

. Using the method described in Section 2.1, its plumbing graph (Figure 3) is given by

Figure 3.

A plumbing graph of Y.

Remark 5.

The number of structures of is .

2.3. Quantum Modularity

An important feature of is the quantum modularity property. It strengthens the connections between seemingly disparate fields—topology and number theory. Furthermore, the quantum modularity property reveals how false theta functions and mock theta functions are related from a topological perspective. Another significant aspect is the appearance of higher-depth quantum modular forms [75]. It has been shown that these forms appear in invariants of plumbed manifolds whose graphs contain multiple high-valence (degree ) vertices. This result highlights the role that multiple high-valence vertices play in modularity.

The quantum modularity feature of is not manifest from (4). In [53], it was shown that can be expressed in terms of quantum modular forms for Seifert fibered manifolds. This connection is realized by a certain representation of a covering group of the modular group , which is called the metaplectic group . (It is an universal double-covering group of . It consists of elements of a pair , where is a holomorphic function satisfying a condition. The group multiplication is .) We begin with a review of a (sub)representation of .

Relevant subrepresentations for are the Weil representations. They are subrepresentations of the -dimensional representation spanned by the vector , whose components are .

From (6), weight unary theta functions in the upper half-plane H can be defined by

We next consider the group of exact divisors of m denoted by . (A divisor n of m is exact if ). Its group operation is . For a subgroup , a subrepresentation of can be defined as follows. Consider a matrix

Using (8), projection operators can be defined as

For subgroups K not containing m (non-Fricke case) (for the Fricke case, see Section 8 in [53]) and m being a non-divisible square number, we can define additional projection operators as

where denotes the pair for . Using (9), we define

From above, we define a set consisting of unequal (up to a sign) vectors . This set provides a basis for . We have a few remarks in order.

Remark 6.

In case m is square-free and Exm, then is irreducible.

Remark 7.

In case m is not square-free ( for some prime p and square-free r), (9) is modified (see Section 3.3 for details [53]).

Remark 8.

For Seifert fibered manifolds with three singular fibers, the Fricke case is relevant.

We next introduce the false theta functions and describe their relevance to .

Let be a cusp form of integral or half-integral weight w. Its Eichler integral is defined by

Applying (10) to (7) leads to the false theta function, which is the Eichler integral (10) of the vector modular form:

A crucial observation in [53] was that for Seifert fibered manifolds with three singular fibers can be expressed as a linear combination of (11). The appropriate linear combination is given by

where

And . Furthermore, other data of Y are

When is the Brieskorn sphere , where positive integers are pairwise relatively prime, there is one . (Brieskorn spheres are ; hence, .) The modular data and the Weil representation (we use and notations interchangeably) are fixed by the above parameters:

where d is the dimension of the Weil representation. From the viewpoint of the Chern–Simons theory on , it is the number of flat connections.

Remark 9.

A proof of (13) can be found in [51] (cf. Proposition 4.8).

The above false theta function (11) is an example of quantum modular form defined in [76]. Specifically, (11) is a quantum modular form of weight (There is a weight change for quantum modular forms (see Section 7.3 in [53] for details)). The quantum modular form is defined through a particular a difference between the quantum modular form and its transform.

Definition 1

([76]). A quantum modular form of weight k and multiplier χ on is a function Q on such that for every , the function , defined by

has some property of continuity or analyticity for every .

Another example of quantum modular form is the Mock theta function. It plays an important role for of orientation-reversed 3-manifolds . We will discuss it in Section 2.7. Next, we move onto examples.

Examples (see [53] for additional examples)

. Its plumbing graph is depicted in Section 2.2. We compute the Chern–Simons values.

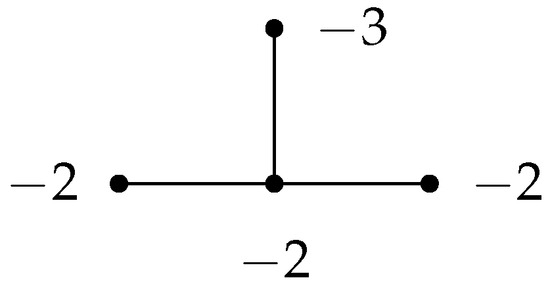

. Using the method described in Section 2.1, its plumbing graph (Figure 4) is

Figure 4.

A plumbing graph of Y.

We find that . Then , where .

Remark 10.

The calculations of of Seifert fibered manifolds from the physics approach were conducted in [77].

2.4. Line Operators

Line operators in QFTs play an important role. They carry the phase structure of the theories. Well-known examples of line operators are Wilson and ’t Hooft lines. The former informs whether a QFT is in, for example, confining or deconfining phase. In TQFTs, expectation values of line operators yield topological invariants by wrapping knot or links with the operators. In the context of , an insertion of line operators into was first analyzed in [48]. This is natural from the perspective of quantum field theories. Specifically, gauge theory contains -BPS line operators. A knot K in colored by a finite dimensional (irreducible) representation R of G gives rise to a line operator .

where is a category of BPS line operators. From the M-theory viewpoint, the line operators originate from M2-branes wrapping cotangent bundles of K and located at the origin O of the cigar, . We denote the Hilbert space of with by

It is bigraded carrying homological (R-charge) grading j and q-grading i. Thus (14) can be decomposed via the gradings.

And the graded Euler characteristics yields the partition function on :

From the viewpoint of , adding corresponds to inserting the character of R into the integrand of (4),

In case is a Len space , calculations have been carried out in Section 4.3.1 of [48].

Remark 11.

The calculations of of Seifert fibered manifolds containing a knot from the physics approach were conducted in [78].

The above situation was generalized to a weakly negative definite plumbed manifold with multiple Wilson line operators inserted in [54,79]. Specifically, for the gauge group, let be the fundamental weight of , and insert the line operators at vertices of . Then is given as follows.

Definition 2

([54]). Consider a weakly negative plumbed manifold and defects associated to a collection of nodes in Γ, with the highest-weight representation with the highest-weight . Define the defect by

where is the character (15).

We observe that an effect of inserting the line operators is shifting the structures in .

Proposition 2

([54]). The defect (19) is invariant under the Kirby–Neumann moves in Figure 1 preserving the nodes with . Hence it is a topological invariant of .

From the viewpoint of quantum modularity, the insertions of line operators (16) was predicted to realize all components of (11) for a class of plumbed manifolds. This is stated in the following conjecture.

Conjecture 3

([54] The modularity conjecture). Two infinite q-series are equivalent, , if , where and . Consider a Seifert manifold with three singular fibers . Define

And extend the equivalence between infinite q-series to their spans. There exists a Weil representation

for some positive integer m and a subgroup such that the following is true:

- 1.

- When is negative definite, is equivalent to .

- 2.

- When is positive definite, there is an vector-valued (mixed) mock modular form transforming in the dual representation of such that is equivalent to .

This conjecture was proved for the Brieskorn spheres.

Theorem 2

([54]). Conjecture 2.18 is true for Brieskorn spheres . More precisely, we have

where is a (possibly vanishing) polynomial and .

Remark 12.

The modularity data of are stated in (13).

We illustrate the above conjecture via examples [54].

Example : The modular data m and K are

And .

In the absence of a line operator, we only have one element in . The other two can be realized via a line operator insertion.

. Its .

And .

They span all the components. In this case, the line defect insertions result in

2.5. Effective Central Charge

The integrality of coefficients of is a core feature of its topological invariance and its clue to existence of the deeper algebraic structure. From the physics perspective, coefficients of a (supersymmetric) partition function or (superconformal) index of a (supersymmetric) QFT reflect the dimensions of sectors of BPS Hilbert spaces of the theory. This is in turn tied to the central charge of the theory via the counting of dynamical degrees of freedom. In [80], the coefficients of (5) were analyzed in the context of strongly coupled superconformal field theories (SCFTs). Specifically, it was shown that has a particular growth behavior as a function of n and the specifics of the behavior were encoded via an analogue of central charge of the theories, which was called effective central charge . We begin with the following prediction about the BPS states of SCFTs.

Conjecture 4

([80]). In every SCFT, the spectrum of supersymmetric (BPS) states obeys

In other words, coefficients of the superconformal index or, equivalently, partition function,

has the property in (17).

Definition 3

([80]). Assuming Conjecture 2.21, to any SCFT we associate a quantity defined via the asymptotic behavior of superconformal index (18):

It is expected that (19) measures the number of degrees of freedom of SCFTs.

Evidence for the above conjectures was provided for non-negative definite Brieskorn spheres in [80]. The coefficients in (18) grow as

From numerical analysis, it was concluded that for . And values of m are estimated, which are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Values of m for various Brieskorn spheres [80].

Hence, the formula of for is given by

Remark 13.

We will describe for orientation-reversed manifolds in Section 2.7.

Remark 14.

Further investigations on were carried out recently in [81,82].

2.6. Relations to Other Invariants

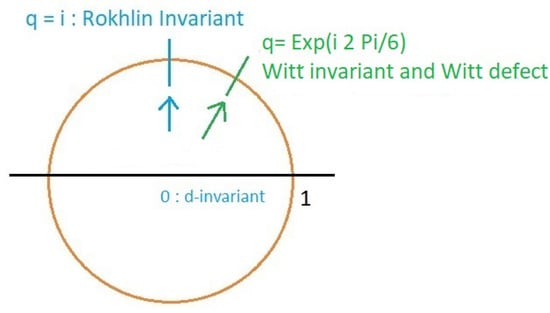

A connection between the quantum invariant and topological invariants was first found in [56]. The authors investigated the spin-refined version of the WRT invariant at the fourth root of unity and elucidated that the corresponding are related to the Rokhlin invariant and the d-invariant (or the correction term) of a certain version of the Heegaard–Floer homology for several classes of 3-manifolds (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Topological invariants at the fourth and sixth roots of unity from the limits of .

Among a variety of topological invariants, an interesting one is the cobordism invariant. It establishes a relation between n-dimensional manifolds via cobordism: -dimensional manifold ). This includes whether can bound . This feature is informed by the cobordism groups . If , then this implies that can bound . If is equipped with a spin structure, then the relevant cobordism groups are spin cobordism groups . When , it vanishes. Hence, spin bounds a (topological or smooth) spin four-manifold . The spin structure of the latter originates from the former by an extension. Rokhlin proved that an invariant depending on its spin structure s is related to the signature of up to mod 16 [83]:

An implication is that if is smooth, then .

A precise relation between and was shown in [56]:

Furthermore, the overall exponent in is related to the d-invariant as

In case of ,

In case of (i.e., ),

In general, for Y whose first Betti number , is given by

where is the linking form.

The invariant was further analyzed for negative definite plumbed manifolds in [84]. It was found that is related to a topological invariant , where s is the number of vertices of the plumbing graph and k is the characteristic vector. The latter is an element in , where W is a four-manifold bounded by Y. In case of negative definite plumbed manifolds, can be expressed in terms of data of plumbing graphs.

Proposition 3

([85]). Let be a negative definite plumbed manifold which is a rational homology sphere. Then

where and is the degree vector (V is the set of vertices of ).

We state the relation between and .

Theorem 3

([84]). Let be a Seifert fibered manifold with n singular fibers associated to a negative definite plumbing graph. Let can be the canonical structure of Y. Then satisfies

If Y is not a lens space, then is minimal among all .

In the Introduction, the CGP invariants were mentioned as an example of non-semisimple invariants from a non-semisimple TQFT. An interesting connection between the CGP invariants and the quantum invariant was conjectured in [86]. The structure of this relation is similar to that of and . It is given by

Conjecture 5

([86]). Let Y be a rational homology sphere equipped with a Kirby color . Then the CGP invariants at roots of unity r and are related by

where the following applies:

- is an appropriate version of the Reidemeister torsion;

- is the linking form on and the summations over ;

- σ is the canonical map ;

- is the Rokhlin invariant of Y equipped with a spin structure .

Remark 15.

It was shown in [86] that the above conjecture holds if certain assumptions are imposed (cf. Theorem 4.18).

Remark 16.

A generalization of the above conjecture to three manifolds with was stated in [86] (cf. Conjecture 3).

Another connection between and topological invariants were found in [55]. Specifically, a new relation between the Witt invariant , Witt defect , and of Y from a certain refinement of the WRT invariant at the sixth root of unity was established. In [87], the WRT invariant at the sixth root of unity for a closed oriented 3-manifold was investigated. It was shown that the WRT invariant is a sum of the invariants of the manifold equipped with a one-dimensional mod 2 cohomology class :

Furthermore, can be expressed in terms of and :

Let us first review the Witt invariant and defect of 3-manifolds defined in [87]. Their formulation takes place in four dimensions. Let Y be a closed oriented 3-manifold. By the vanishing of its oriented cobordism group , Y bounds a compact oriented 4-manifold X whose intersection form is denoted by . Its signature is denoted by . We next diagonalize in a -coefficient ring, obtaining as its diagonal entries. We denote it by . Then we let be its trace Tr . The mod 3 Witt invariant of Y is defined as

is independent of X. Since we deal with a compact 4-manifold with a boundary, we would like to detect an effect of the boundary. This leads to the notion of the Witt defect. Specifically, we consider a cyclic n-fold cover manifold . By the result of [88], this covering manifold extends to a cyclic branched cover branched along a closed surface F in X. We let be an intersection form of in the coefficient. The mod 3 Witt defect of is defined as

where n divides . The specific Witt defect that is relevant in our context is a double-cover 3-manifold equipped with a cohomological class :

We abbreviate the above defect as . Due to the presence of the boundary, the difference between the first two terms in (20) is not necessarily zero. Note that and taking value in follows from the fact that the Witt ring of is [89].

The Witt invariant and Witt defect are geometrically defined on the level of 4-manifolds; thus they also possess the cobordism characteristic [55].

For rational homology spheres Y (), there are two different cases. The first case is when odd,

where . When even,

where and (we used the fact that is affinely isomorphic to ). This new relation not only enriches the conceptual aspects of the invariants; it also provides a new method of computing the Witt invariant and Witt defect directly in three dimensions.

Table 2.

A summary of Witt invariants for Lens spaces [55].

Table 3.

A summary of Witt invariants for Lens spaces [55].

2.7. Orientation Reversal

Under orientation reversal of a closed oriented 3-manifold , the WRT invariants of at level k is

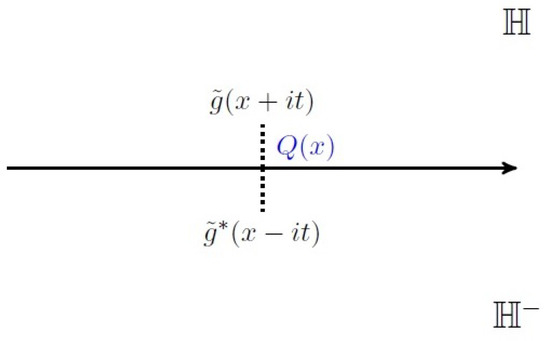

Since the WRT invariant is a complex number, the orientation reversal amounts to applying the complex conjugation, or equivalently, sending . The latter implies that . In the case where a topological invariant is a series, for instance, , orientation reversal of Y translates into a nontrivial operation. Naively sending does not lead to a correct series for . As a consequence, a major challenge in the development of is finding a formula for positive definite plumbed manifolds (for lens spaces , their are monomial. Hence, can be obtained by ). In case of , it is a q-power series defined on the outside of the unit disk in the complex plane . From the viewpoint of quantum modularity in Section 2.3, of certain manifolds can be expressed in terms of a linear combinations of the false theta functions. In [53], it was shown that can be expressed in terms of the mock theta functions. And there exists a false-mock pair for between and . The pair is defined on the complex plane. Specifically, the false theta function is defined on the upper half, and the mock theta function is defined on the lower half, as shown in Figure 6. The definition of the mock theta function was established by Zwegers [90].

Figure 6.

A pair of quantum modular forms, false and mock theta functions [53].

Roughly speaking, it is the holomorphic part of a harmonic Maass forms. The formal definition is given as follows.

Definition 4

([53]). A holomorphic function f on is a mock modular form of weight k and multiplier χ, if and only if there exists a weight cusp form g on Γ such that the non-holomorphic completion of f defined by

satisfies for every and

Remark 17.

In the above or , the congruence subgroup of .

In the physics context, let us recall that appeared in Section 2.2 and Section 2.5. It is a necessary for testing the superconformal index of SCFTs and the effective central charge. It is clear that orientation reversal is necessary for a complete understanding of for all types of plumbed manifolds.

Although there are available approaches to find , they have limited applicability or difficulty to implement in practice. We summarize the approaches:

- q-Hypergeometric series: It was shown in [53] that of particular Seifert fibered manifolds with three singular fibers, for example, and , can be expressed in terms of q-hypergeometric series. It is a rational function, which allows us to apply to obtain straightforwardly. A caveat of this method is the a q-series can be expressed in multiple ways in terms the q-hypergeometric series; thus, there is non-uniqueness. Each expression leads to a different q-series after , and one of them is the desired .

- Rademacher sums: This method is systematic and sophisticated [53]. Obtaining involves finding a certain function in the lower half of the complex plane, which is an image of mock modular form.

- Resurgence method: This method utilizes the quantum modular property of [91] (the resurgence method is a technique that enables one to analyze strongly coupled QFTs. It was applied to the complex Chern–Simons theory in [92]). The method aims to find a dual of a false theta function :A starting point for obtaining is the Borel–Mordell integral and its unique decomposition,where is a q-series and is a -series. Using (21) and the numerical analysis, and are determined (an analytic continuation of (28) into the regime is given in Section 4.6 of [91]), and they include the desired mock theta functions .

Remark 18.

In the above, , and from Section 2.3.

- 4.

- Indefinite theta functions: Instead of using the negative definite lattice for the theta function in (4), an application of indefinite lattice theta functions was introduced in [93]. Specifically, it used an indefinite lattice theta function together with a regulator. In this approach, there is a choice of a one-sided cone when summing over lattice vectors. This idea was further pursued and refined in [59], which used a double cone.

An example in which q-hypergeometric series method can be applied is [53]. Using (13), we have

We next invert q to jump to the region and use the identity

Then we arrive at

Compared with the result in Section 2.2, the coefficients are no longer .

3. Series Invariant for Link Complements

3.1. A Two-Variable Series for Knots

Motivated by (4), a multi-variable series for complements of plumbed knots was defined in [51]. We begin by reviewing plumbed knots.

Plumbed knot complements, more generally plumbed 3-manifolds with a torus boundary, are represented by a weighted graph with one distinguished vertex [51]. This vertex represent the torus boundary. We are interested in the case when the degree of is one. From the viewpoint of the surgery link described above, an unknot corresponding to acts as a spectator during the surgery operation. Furthermore, removing and the edge connecting it to represents an ambient plumbed 3-manifold .

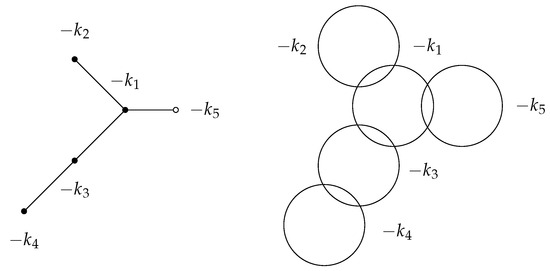

An additional data describing a knot is a framing that takes values in . Roughly speaking, this value characterizes the twisting of a longitude of the knot around the knot. This information is captured by weight of . This is called graph framing. Therefore, complement of a plumbed knot in is specified by . A simple example is shown in Figure 7. The Neumann moves in Figure 1 also apply to plumbing graphs of knots, except the blow-up/-down move on .

Figure 7.

A plumbing graph of a knot (left) and corresponding surgery link (right). The linking between two link components is the Hopf link. This link diagram can be transformed into a knot diagram through the Kirby moves.

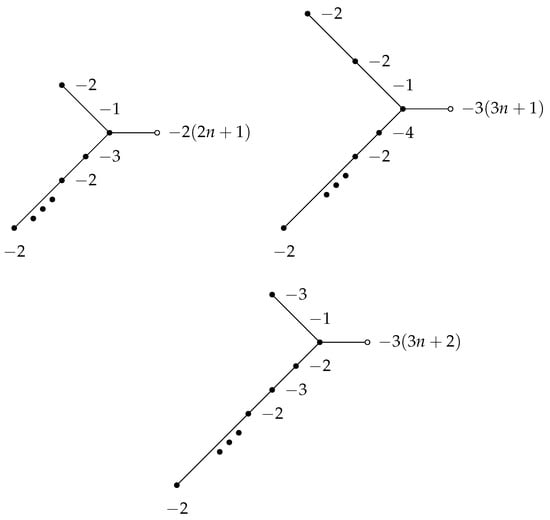

We review the method for obtaining plumbing graphs of torus knots in [51]. We consider torus knots , where . Torus knots are examples of algebraic knots. Hence, they and more precisely their complements admit plumbing graph presentations. The graphs consist of one multivalency vertex having degree 3, weight , and three legs attached to the vertex. One of the legs has an open vertex of degree 1 called distinguished vertex, representing a torus boundary of the knot complement. To find vertices and weights on the other legs, we solve

for unique integers and satisfying

Then we expand and in continued fractions in Section 3.1. Each of them forms a leg with weights attached to the central vertex. The weight of the distinguished vertex is given by (this value corresponds to 0-framed torus knots). Example of plumbing graphs are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Plumbing graphs of (left), (right), and (bottom). The ellipsis indicates intermediate vertices with weight along the legs. The total number of vertices in succession on the leg is for , and .

For complements of plumbed knots that are (weakly) negative definite , a three-variable series was defined [51]:

where denotes a set of vertices of and B is the linking matrix of . We note that there is no integration over in (22).

Using the properties of the plumbed knot complements, it was shown that (22) reduces to an independent two-variable series denoted by . It turns out that has the following general form for all knots in :

where and .

Remark 19.

The variable x in (23) counts with the relative structures of the knot complement.

Remark 20.

Generally, the coefficient functions are a Laurent power series ; knots whose Alexander polynomials are non-monic have this property. In case of fibered knots, they are Laurent polynomials.

3.2. Large Color R-Matrix

Inspired by the quantum R-matrix formulation of the colored Jones polynomials, R-matrix formulation for was constructed in [58]. This approach revealed the infinite-dimensional Verma module structure of quantum group at generic q underlying . From a computational viewpoint, the R-matrix formulation vastly extended the classes of knots for which can be computed. For example, positive braid knots and positive double-twist knots were computed explicitly in [58]; both of them are infinite families of knots. As in the case of colored Jones polynomials, the R-matrix approach utilizes a braid presentation of K in Figure 9, and the R-matrix acts on the infinite-dimensional Verma modules of over . There are two such modules. One of them is the highest-weight Verma module with the highest- weight :

where the top and the bottom maps are e and f generators of , respectively. There is a basis with for which the actions of are given by

where . The second one is the lowest-weight Verma module with lowest-weight :

where the top and bottom maps are e and f generators, respectively. There is a basis with for which the action of is given by

Figure 9.

Braid , more precisely -tangle setup.

Remark 21.

The color does not need to be an integer.

Remark 22.

The effects of e and f on the bases are interchanged for highest- and lowest-weight Verma modules.

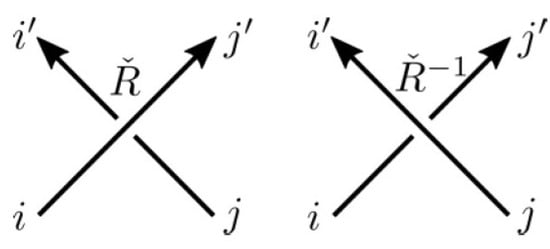

The quantum R-matrix on the Verma modules for for positive and negative crossings (see Figure 10) are given in [58] as

respectively. These large color R-matrices satisfy the quantum Yang–Baxter equation

Figure 10.

and matrices for positive and negative crossings, respectively, are shown.

Compactly, the definition of in terms of a braid closure and hence the R-matrices is given by

where the superscript ± denotes positive or negative x-expansions of (27) and is the reduced quantum trace (Reduced refers to opening up a braid as in Figure 9. It is related to the usual quantum trace (see Section 4 of [58] for details)).

Remark 23.

An important aspect of the state sum formulation ( Tr) is (absolute) convergence of power series in and q. This restricts to classes of knots in which (25) is applicable. For example, positive braid knots, fibered strongly quasi-positive braid knots, and positive double-twist knots have been computed.

For the above classes of knots , we have

In case of mirror knot of , is replaced by and becomes . The other half can be obtained using Weyl symmetry.

Remark 24.

If two crossing strands are colored by different representations, (24) become functions of x and y variables (see Section 3.2 in [58] for details).

The above large color R-matrix was generalized to representations of in [57]. In the higher-rank case, infinite Verma modules form high-dimensional lattice, whose dimension depends on the value of N. For example, when , the dimension of the lattice is two. This is because -Verma modules are labeled by . Examples of positive braid knots and homogeneous braid knots have been computed in [57].

We move onto the link generalization of .

3.3. Inverted State Sums

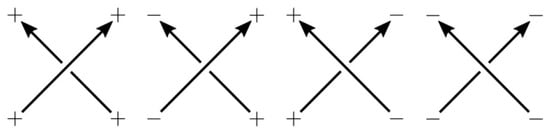

A generalization of (23) to links was achieved in [59]. The main features of the generalizations are domain extensions of (24) and (25) and the introduction of four building blocks of braids, as shown in Figure 11. Specifically, the domains of and are extended to the set of all integers. In the case where two strands of a braid are the same, the R-matrices are given by

Figure 11.

Crossing for the inverted state sum.

In the case where two strands of a braid are different, we need multicolored R-matrices. The strand associated with is assigned an x variable, whereas the strand associated with is assigned a y variable. The extended multicolored R-matrices are given by

Over- and under-crossings carry signs, which result in four kinds of crossings, as shown in Figure 11. The signs are tied to the highest- and lowest-weight Verma modules. There are rules for assigning signs to crossings in a braid diagram, more precisely (1,1)-tangle (see Section 1.3 of [59] for details).

Remark 25.

The two-variable extended R-matrices in (28) and (29) can be obtained from the two-variable R-matrices in Section 3.2 of [58].

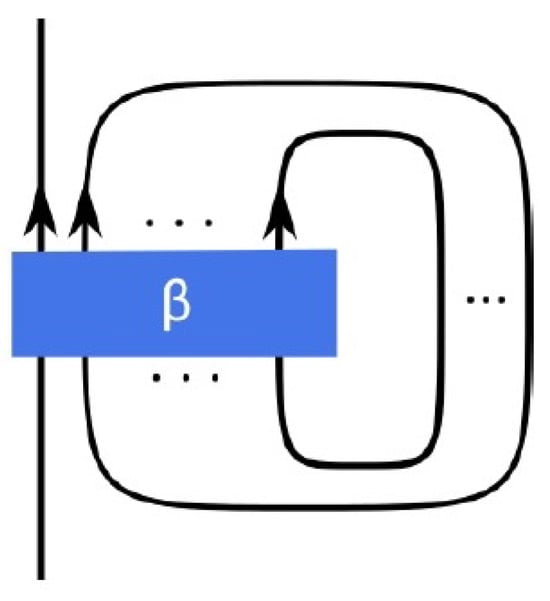

Using these building blocks, for any homogenous links (the definition of homogenous links is that each generator of their braid group appears with either positive or negative powers in a braid word) can be computed. We state the definition of the inverted state sum.

Definition 5

([59]). Given a homogeneous braid diagram β, the inverted state sum is

where

Theorem 4

([59]). For any homogeneous braid link L with a homogeneous braid diagram , let

where x is the parameter associated to the open strand. Then is an invariant of L. That is, it is independent of the choice of the homogeneous braid representative.

The above series is a function of , where l is the number of components of L.

Remark 26.

There are more statements in the above theorem. They are written in Section 3.7.

3.4. Inverted Cyclotomic Series

Among several representations of the colored Jones polynomials of a knot K, there is a particular expression that separates topological and algebraic information of the polynomials and takes values in a completion of the Laurent polynomial ring over the integers [94]. This is often called cyclotomic expansion of the colored Jones polynomials (the cyclotomic expansion is also valid for links). Specifically, for a knot colored by n-dimensional irreducible representation of , its cyclotomic expansion of is given by (this formula is for 0-framed K)

where and . The knot information is completely captured by , and are basis elements of . The cyclotomic expansion manifests the integrality property of . Some examples of are

Motivated by (30), an inverted cyclotomic expansion for was introduced in [59]. Two modifications are as follows: the domain of m of was extended to the set of all integers, and was inverted. Specifically, we have the following conjectural formula.

Conjecture 6

([59]). For any knot K with , it has an inverted Habiro series, and it agrees with the in the sense that

where the right-hand side is expanded into a power series in x.

The extensions of (31) are

Remark 27.

In case of links, inverted for each i-th link component appears in the denominator of (32).

The two expressions of , namely, (23) and (32) are related as follows.

Proposition 4

([59]). If we write

then

We will see in the next section that (39) is useful for predicting a surgery formula for positive integer slopes.

Remark 28.

An analysis of residues of was investigated in [95].

3.5. Dehn Surgery Formulas

Surgery is an indispensable tool in topology. It consists of cutting and gluing manifolds. It provides different perspectives on manifolds and relates them appropriately, thereby revealing multiple presentations of a manifold. This in turn allows for the analysis of manifolds having sophisticated topology. In three dimensions, Dehn surgery plays an important role. We first review Dehn surgery.

Let be a closed oriented manifold and K be a knot in Y. We carve out a tubular neighborhood of K, which is diffeomorphic to . This yields a compact oriented manifold with a torus boundary. Then we glue a solid torus into along a slope via a diffeomorphism. When gluing, a meridian of the solid torus is mapped to on , where is a meridian and is a longitude of . This results in a closed oriented manifold .

Remark 29.

In the case of links in Y, the above operation is be applied to each component of links with its surgery slope .

There is a classical result regarding closed oriented 3-manifolds and Dehn surgery.

Theorem 5

([96,97]). Any closed connected oriented 3-manifold can be obtained from Dehn surgery on (framed) links in .

In our setting, Dehn surgery establishes a relation between and . There are multiple (conjectured) surgery formulas covering different regimes of surgery slopes for a knot. The surgery formulas allow one to access of closed oriented 3-manifolds that are beyond plumbed manifolds.

Theorem 6

([51] Plumbed knot surgery). Let Y be the complement of a knot K in , and let be the result of Dehn surgery along K with coefficient . Suppose that both and are negative definite plumbed 3-manifolds. Then the surgery on K yields

where

for some and .

The above result was conjectured for all knots.

Conjecture 7

([51]). Let be a knot, and let be the result of Dehn surgery along K with coefficient . Then there exist and such that

Provided that the right-hand side of this equation is well defined.

The well-defined condition is tied to the sign of the surgery slope and the behavior of in (23). In the case when the right-hand side of (34) yields an ill-defined result due to the positivity of the slope , an idea of regularization was proposed to obtain a convergent q-series in the complex unit disc [59]. Specifically, the regularized surgery formulas for positive surgery slopes and are the following.

Conjecture 8

([59] Regularized surgery). When surgery formula (41) converges, we need to use (41). When it does not converge, we can regularize it in the following way, as long as the regularization converges:

where

is the Ramanujan theta function.

The term in the second parenthesis is the regulator.

Conjecture 9

([59] Regularized surgery). When surgery formula (41) converges, we need to use (41). When it does not converge, we can regularize it in the following way:

provided that the regularization converges. The polynomials .

The above polynomials arise from the following rational function:

A list of is available in [54].

Up to this point, we have been focusing on knot surgeries. In the case of links, a formula for Dehn surgery on links along integer surgery slopes has been conjectured.

Conjecture 10

([58] Integral link surgery). Let be the 3-manifold obtained by surgery on , and let B be the linking matrix defined by

Let

Then

for some sign and , whenever the right-hand side makes sense.

Remark 30.

A surgery formula for the infinite surgery slope was found in [98].

The above Dehn surgery formulas were generalized in the case of the presence of the line operators in Section 2.4.

Definition 6

([54]). Consider the series associated to the plumbed knot K with a defect operator along K in the highest-weight representation of with the highest-weight . We define the corresponding defect invariant for the closed manifold as

where the sl(2) character is the same as in (15) and are the same as in (34).

3.6. Perturbative Expansion

A perturbation series in physics reflects the contributions of quantum effects in the spirit of quantum mechanics—that is, how quantum perturbations affect an original system. In the case of quantum invariants of knots, the same idea can be applied. For instance, a connection between colored Jones polynomials and Alexander polynomials of a knot K (the knot is 0-framed) was discovered in [99,100,101] and proven in [102]. This relation appears in the perturbative expansion of the former.

where are Laurent polynomials. This expansion is natural from viewpoint of the Chern–Simons (CS) gauge theory. It is a weak coupling (i.e., large-CS-level ) regime of the theory. Motivated by the above perturbative expansion, a similar property was conjectured for .

Conjecture 11

([51]). For a knot , the asymptotic expansion of the knot invariant about coincides with the Melvin–Morton–Rozansky (MMR) expansion of the colored Jones polynomial in the large color limit:

where is fixed, n is the color of K, , , and is the (symmetrized) Alexander polynomial of K.

A generalization of the above conjecture to links was stated and proved.

Conjecture 12

([58]). There are a link invariant , a series in , and q with integer coefficients, where l is the number of components of link L, such that

where the right-hand side is the large color expansion of the colored Jones polynomials expanded around while keeping fixed for each and is the Alexander–Conway function of L.

Theorem 7

([59] Theorem 1 (2)). Let L and be as described in Theorem 4. By setting , the ℏ-expansion of agrees with the MMR expansion of the colored Jones polynomials.

The perturbative analysis has been extended to associated with a Lie algebra for positive braid knots colored by any irreducible representations of (only symmetric representations were considered in [57]) at generic q in [103]. The perturbation series takes the following form.

Theorem 8

([103] for ). Let be a positive braid knot. Then the reduced quantum trace converges in , and

is a well-defined knot invariant that satisfies

where and .

3.7. Recursion Method

Another well-known property of the colored Jones polynomials of a knot K in is that they are q-holonomic [104,105] (this property is also valid for links as well). Specifically, they satisfy the recursion relation

where is the color of K and is called quantum (noncommutative) A-polynomial of K and is a q-difference operator of the form

The operators and act as

The above recursion relation enables to find for any color. It was conjectured that also satisfies a recursion relation given by the same [51].

Conjecture 13

([51]). For any knot , the normalized series satisfies a linear recursion relation generated by the quantum A-polynomial of K :

where .

The actions of and are

Conjecture 14

([58]). The link series defined in Theorem 4 is annihilated by the quantum A-ideal annihilating of the colored Jones polynomials of L.

Theorem 9

([59] Theorem 1 (3)). Conjecture 13 holds.

3.8. ADO Polynomials

We saw that at roots of unity are related to other topological invariants of 3-manifolds, as described in Section 2.6. Similarly, evidence for a connection between at roots of unity and ADO polynomials of K was discovered in [106]. The latter are non-semisimple quantum invariants [15]. The precise form of the relation is given by the following conjecture.

Conjecture 15

([106]). For any knot K in ,

This conjecture was verified for some values of p for the right-handed trefoil and the figure eight knots [106]. Further evidence for the conjectures, including formulas for and an algorithm for of a family of torus knots, was given in [107]. We record explicit formulas of for . They are divided into three types depending on their coefficient pattern:

- For

- For

- For

All the explicit x terms are polynomials, and the power of x decreases by two after one cycle of a coefficient combination. Another advancement was the introduction of a refinement of [108]. It was shown that admits two parameter deformations through the superpolynomial [109,110]. This led to a generalization of the above conjecture.

Conjecture 16

([108]). For any knot K in , there exists a t-deformation of the symmetric -polynomial of K for ,

And the specialization reduces to the original (up to the rescaling of x).

From Conjecture 16, a refined polynomial for , is

where the terms are determined by the t-deformed Weyl symmetry of the invariant,

The suppressed polynomial terms follow the same power and coefficient patterns of the previous terms. The three formulas for the original coalesce into one formula by the t-deformation.

3.9. Knot–Quiver Correspondence

The connection between knots and quivers was discovered through the identification of a certain knot invariant (the LMOV invariant) with a (motivic) Donaldson–Thomas invariant [111,112]. The significance of this relationship is that it established the integrality of the knot invariant. Additionally, it provided a quiver-theoretic perspective on the structure of colored HOMFLY-PT polynomials and superpolynomials. Furthermore, another consequence of this connection was the generalization of knot invariants from symmetric representations to arbitrary representations.

Another interesting connection between the deformed series (this series is a series analogue of the colored HOMFLYPT polynomial) and quiver theory [111,112] was discovered in [60]. It was described that can be obtained from the so-called motivic generating seriesthat characterizes a quiver. We begin by reviewing the quiver side.

A quiver Q is an oriented graph consisting of a finite set of vertices and a finite set of arrows between them (i.e., ()). An adjacency matrix C of Q is the matrix with entries equal to the number of arrows from i and j, where . If , then Q is called a symmetric quiver. A quiver representation is an assignment of a finite dimensional , which is complex vector space, to the vertex and a linear map to each arrow from vertex i to j. A goal in quiver representation theory is to investigate modulus spaces of quiver representations. In the case of symmetric quivers, information about the modulus space of representation is encoded in motivic generating series defined as

where

In [113], it was shown that the knot–quiver correspondence can be generalized to knot complements of torus knots . Specifically, this involves data of a symmetric Q, integers , and half-integers to a knot complement . Then the deformed can be obtain from (37) as

where .

Remark 31.

We note that the deformed is associated with an abelian branch of A-polynomial of K. For associated with other branches, see Section 3 of [60].

The general quiver form of is given by [108]

where denote constant vectors of appropriate size, is the identity matrix, and for .

The converse direction, namely, extracting a quiver structure from , was shown in [60]. For example, we start from , the left-handed trefoil, in the following form:

We next apply the following identity to (it is Lemma 4.5 in [112]):

Then we get

After using the identity

we arrive at a quiver form

An alternative identity that can be applied to (39) is

An application of this identity yields

Remark 32.

The final forms (41) and (43) are connected by operations on the vertex of quivers (see [114] for details).

A closely related result in [60] is that colored HOMFLYPT polynomials of knots K colored by symmetric representation in a quiver form (where the subscript r in refers to ; there is a conjecture regarding expressing the generating function of the colored HOMFLYPT polynomials in a quiver form in [112]) can be used to obtain . This requires a framing K in a particular way. Let Q be a quiver corresponding to K and and be the vectors. Suppose that

where . Next, permute rows and columns of C such that and . We express in a quiver form as

To convert (44) into , we framed K by , which amounts to multiplying by and setting .

The last step is applying (40) or (42) to (45).

Remark 33.

It was shown that in terms of R-matrices and inverted cyclotomic series in the previous sections can also be transformed into the quiver form [60].

3.10. TQFT Property

By the axioms of n-dimensional TQFTs [8,9], to an -dimensional manifold, a vector space over a ground field is assigned (it is finite dimensional by consequences of the ingredients of TQFTs):

To a n-dimensional manifold (bordism), a linear map between tensor products of vector spaces is assigned:

where i and r run over incoming and outgoing boundaries of , respectively (in the case of , is a closed n-manifold, which is a bordism from an empty manifold to , and an element of is assigned).

In our 3-dimensional setting, a vector space is attached to the torus boundary of the knot complement equipped with relative structures, and is the Novikov field. Its elements are

such that set is bounded below and its projection to is finite.

The relative invariants are vectors:

Specifically,

where m is associated with the meridian of and n corresponds to the longitude.

For a closed (oriented) 3-manifold Y equipped with structures, we have

Furthermore, there is a bilinear pairing (inner product) on :

This reflects the gluing in the TQFT framework,

where R is the orientation reversal map for the meridian

So far, we have cobordisms with one boundary component of genus one. In order to arrive at the complete structure of a decorated TQFT, we have to consider cobordisms with multiple number of boundary components of genus one and higher genus as well.

3.11. Examples

A variety of examples of have been computed. We summarize a subset of them.

Theorem 10

([51]). Let with gcd. For the positive torus knot , the series is given by

where

In the above example, is monomial in q. It is the only knot of that feature to the best of the author’s knowledge.

In the case of mirror torus knots ,

- Figure eight

This was the first hyperbolic knot computed via the recursion method in Section 3.7 [51]. A closed-form formula was obtained using the R-matrix in Section 3.2 in [59]. Some of are

We observe that , reflecting the amphichirality property of the knot.

- Positive double-twist knots [58]

full twists,

where and are sign functions.

Remark 34.

The above family of knots includes left-handed trefoil () and ). The series of the latter has as Laurent power series .

Remark 35.

There is also a formula for family (see Section 4.4.1 in [58] for details).

- Cable knots [115,116]

Combining the torus knots and the figure eight knot from the above examples, infinite families of cable knots (a class of satellite knots) were analyzed using the recursion method in Section 3.7. Specifically, the of

were computed. Their coefficient functions are linear combinations of coefficient functions of (a cabling formula for was found in [98]).

4. An Extension to Lie Superalgebras

4.1. The Super Series

We review the q-power series invariant of closed oriented 3-manifolds associated with a Lie superalgebra introduced in [65].

A non-semisimple quantum invariant of closed oriented 3-manifolds Y associated with at a root of unity of odd order was constructed in [23]. Core ingredients of the construction are a non-semisimple ribbon category of simple finite dimensional representations of from [20] and the modified quantum dimension. The data for the quantum invariant of Y are the root of unity of odd order , odd , and a 1-cocycle:

Then the non-semisimple quantum invariant is denoted by

In case of a particular class of 3-manifolds called plumbed manifolds , it was shown in [65] that (46) decomposes into q-power series:

where and denotes structures on Y (its definition is a lift of the structure group of the tangent bundle of Y to the group). This q-series is an analytic continuation of (46) into the complex unit disk. The decomposition of (46) is given by

where , and . Furthermore,

where V is the vertex set of , is the number of positive eigenvalues of B, and indicates a choice of chamber. And is an integration contour. Moreover, the variables are and and are coordinates on the maximal torus, where and are roots. In contrast to associated with the classical Lie algebras [48,52], super (49) carries two labels .

Remark 36.

The above integrations are equivalent to picking constant terms in the variables.

- Generic plumbing graphs

A notion of genericity of plumbing graphs was introduced in [65]. The definition states that for a plumbing graph containing at least one vertex whose degree is larger than two, the graph does not admit splitting such that if and , then , where is the set of vertices whose degrees are not two.

- Good Chambers

The integration contour in (49) is equivalent to a choice of an expansion chamber . In order for (49) to yield a well-defined power series, a (generic) plumbing graph containing at least one vertex of degree larger than two must admit good chambers. The existence condition of good chambers is given in [65]: If there exists a vector

such that

is copositive and

matrix X is copositive if for any vector v such that , with at least one , and we have .

If a good chamber exists for a generic plumbing graph, then there are two of them, and the domains of and corresponding to a vertex are given by

This translates into the following allowed expansions: For vertices of degree , the expansions are

For vertices of degree , the expansions are

Several remarks are in order.

Remark 37.

Other domains of expansions are and . However, they are ruled out by the generic property of plumbing graphs.

Remark 38.

In (47), constant comes from regularizing a diverging constant. We will see this in the origin of the diverging constant in Section 5.

For general closed oriented 3-manifolds Y, we have the following conjecture.

Conjecture 17.

The quantum invariant (46) of closed oriented 3-manifolds that are rational homology spheres () admits a decomposition in terms of the super .

where T is the Reidemeister torsion of the flat connection .

Remark 39.

The above ± reflects the sign ambiguity in the definition of the torsion.

Proposition 5

([66]). The super (49) is invariant under the Kirby–Neumann moves in Figure 1.

- Examples

We list a few examples [65].

where is the number of divisors of m.

where , and is the Hurwitz zeta function.

Using (50) to (52), good chambers can be found:

They in turn determine the domains of . Then the super of Y from (49) is

Either choice of via (53) and (54) yields

where ≅ denotes up to the regularized constant and the constant terms in are picked from the integrations.

For general , we write the formula that manifests the algebraic structure of the superalgebra. Specifically, its super for a plumbed manifold with its adjacency/linking matrix B is [65]

where for even/odd roots ( appears in the Weyl super character formula), is the normalized measure on a maximal torus of , is the root lattice, is the Killing form, is the set of positive roots, is the Weyl vector, and is the number of positive eigenvalues of B.

4.2. Supergroup Chern–Simons Theory

We realize Chern–Simons theory on Y associated with a Lie supergroup as a world-volume theory in string/M-theory [65,117] (see also [118]). This allows us to predict an explicit formula of the super of Y.

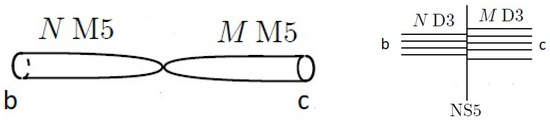

We begin with a brane system in a 11-dimensional spacetime (ST) in M-theory. We take the 10D spatial geometry to be a cotangent bundle of a 3-manifold and the 6-dimensional Taub-NUT (TN) space. The former is assumed to be a rational homology sphere. The latter looks like two cigars whose tips are joined at an origin. Away from the tip, the geometry looks like , where the circle is taken to be the M-theory circle. Near the tip, the geometry looks like .

where is a time circle. The two stacks of M5 branes wrap the indicated parts of the spacetime, as shown in Figure 12. The copies of are part of the TN space. This spacetime geometry has symmetries from the TN space, (If has a circle fiber, for example, a Seifert fibered manifold, then an extra symmetry group exists). We next shrink to reduce to 10-dimensional spacetime. This process lands us in type IIA string theory, and the brane system becomes

| 11D ST | × | × | Taub | − | NUT | ||

| M M5 branes | × | × | × | ||||

| N M5 branes | × | × | × |

| Type IIA 10D ST | × | × | |||

| 1 D6 brane | × | × | |||

| M D4 branes | × | × | |||

| N D4 branes | × | × |

Figure 12.

The cigars of the Taub-NUT space of 11-dimensional spacetime that are wrapped by the branes (left). The brane system of the Type IIB theory (right). The labels b and c are the asymptotic boundary conditions taking values in for .

The M5 branes are transformed into D4 branes. The D6 brane appears as a consequence of the Taub-NUT space. We apply T-duality along to pass to type IIB. And then we apply S-duality. We arrive at the following final brane system shown in Figure 12:

| Type IIB 10D ST | × | × | |||

| 1 NS5 brane | pt | × | × | ||

| M D3 branes | pt | × | × | ||

| N D3 branes | pt | × | × |

The S-duality maps the D5 brane to NS5 brane. The former was obtained from the above D6 brane. On the stack of the D3 branes, its world-volume theory is super Yang–Mills with gauge groups , whereas the theory on the other brane stack has gauge group .

We next apply the (GL) topological twist along of to the above super Yang–Mills theories [119]. This results in a cohomological quantum field theory that is a coupled 4d-3d system across the NS5 brane. The cohomological sector of the theory is the Chern–Simons theory based on (up to Q-exact terms). Its action functional is the supergroup Chern–Simons theory (up to certain exact terms). Furthermore, analogous to the Chern–Simons level parameter in case of a Lie group , Chern–Simons theory carries a parameter K, which comes from the complexified gauge coupling constant of the super Yang–Mills theory, which in turn comes from the complexified string coupling constant.

where is the vacuum angle and the upper half of the complex plane (). Chern–Simons theory is supported on in the NS5 brane. Its action functional at level K is

where is a fermion field, and is the complexified gauge connection of A:

The + sign provides the -part of whereas the − sign provides the -part of (Recall that the bosonic (Grassman even) part of is ).

The existence of super can be predicted from 11 dimensions. Specifically, the presence of the cigars in Figure 12, in particular their geometry away from the tips, requires imposing (asymptotic) boundary conditions . The partition function over the BPS sector of the Hilbert space of the brane system is

where F is the fermion number operator and is the generator of .

5. Super Series for Knot Complements

Motivated by the idea of partial surgery (29), a generalization of (56) to complements of plumbed knots was analyzed in [66]. We found that a series invariant of plumbed knot complement associated with is a three-variable series. Specifically, it is sum of contributions from good chambers .

The general form of super is

It carries the Weyl symmetry and . In comparison with (23), the summation of (23) is over odd integers, whereas (55) is over a pair of nonzero integers.

5.1. Torus Knots

We use the plumbing graph descriptions of torus knots in Section 3.1 to find good chambers for infinite families of torus knots.

Proposition 6

([66]). Let v be the number of vertices of plumbing graphs of and , and and be the good chambers for torus knots, where corresponds to degree-three vertex and the other two are associated with degree-one vertices of their plumbing graphs. Their good chambers, given by

yield a well-defined (Laurent) power series .

The general structure of the super of torus knots splits into q-independent and -dependent parts. The former is a new feature in super , which is absent in (23). And it can be expressed in terms of the unknot. The latter has the following form:

where and is a sign function (see [66] for its algorithm).

We list a few examples of torus knots (additional examples are recorded in [66]).

5.2. The Dehn Surgery Formula

We provide the Dehn surgery formula relating super to super .

Theorem 11

([66]). Let be the complement of a knot K in the 3-sphere , and let be a result of Dehn surgery along K with slope . Assume that and are represented by negative definite plumbings. Then the invariants of are given by

where the Laplace transform for the chamber is

And the Laplace transform for the chamber is

where , and .

We observe a qualitative difference between the above surgery formula and surgery formula (33) in Section 3.5. For applications of Theorem 11, and for some values of , and were considered in [66].

6. Future Directions

We list open problems:

- Obtaining an analytic formula of defined on for positive definite plumbed manifolds has been a major challenge. Several approaches for computing are listed in Section 2.7. However, they are applicable to specific examples of .

- There are multiple Dehn surgery formulas (cf. Section 3.5). Each has restricted applicability. We believe that a unifying surgery formula exists and would be important.

- Extending the definition of beyond homogeneous links would be valuable conceptually and computationally.

- A construction of in Section 2.2 for categorification of the WRT invariant is highly desirable.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Sergei Gukov for valuable comments on a draft of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nawata, S.; Ramadevi, P. Zodinmawia, Colored HOMFLY polynomials from Chern-Simons theory. J. Knot Theory Ramif. 2013, 22, 1350078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. Quantum field theory and the Jones polynomial. Comm. Math. Phys. 1989, 121, 351–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. Topological quantum field theory. Comm. Math. Phys. 1988, 117, 353–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. Monopoles and Four-Manifolds. Math. Res. Lett. 1994, 1, 769–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshetikhin, N.; Turaev, V. Invariants of 3-manifolds via link polynomials and quantum groups. Invent. Math. 1991, 103, 547–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshetikhin, N.; Turaev, V. Ribbon graphs and their invariants derived from quantum groups. Comm. Math. Phys. 1990, 127, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, R.; Melvin, P. The 3-manifold invariants of Witten and Reshetikhin-Turaev for sl(2,C). Invent. Math. 1991, 105, 473–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiyah, M. Topological quantum field theory. Publ. Math. l’I.H.É.S. 1988, 68, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, G. The Definition of Conformal Field Theory. In Differential Geometrical Methods in Theoretical Physics; NATO ASI Series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Freed, D. Lectures on Field Theory and Topology; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2019; p. 133. [Google Scholar]

- Baez, J.; Dolan, J. Higher dimensional algebra and topological quantum field theory. J. Math. Phys. 1995, 36, 6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, D. Remarks on Fully Extended 3-Dimensional Topological Field Theories. Available online: https://www2.math.upenn.edu/StringMath2011/notes/Freed_StringMath2011_talk.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Schommer-Pries, C. The Classification of Two-Dimensional Extended Topological Field Theories. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1112.1000. [Google Scholar]

- Lurie, J. On the classification of topological field theories. Curr. Dev. Math. 2009, 2009, 129–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akutsu, Y.; Deguchi, T.; Ohtsuki, T. Invariants of colored links. J. Knot Theory Ramif. 1992, 1, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, J. Colored alexander invariants and cone-manifolds. Osaka J. Math. 2008, 45, 541–564. [Google Scholar]

- Geer, N.; Kujawa, J.; Patureau-Mirand, B. Ambidextrous objects and trace functions for nonsemisimple categories. Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 2013, 141, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geer, N.; Kujawa, J.; Patureau-Mirand, B. Generalized trace and modified dimension functions on ribbon categories. Sel. Math. 2011, 17, 453–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geer, N.; Patureau-Mirand, B.; Turaev, V. Modified quantum dimensions and re-normalized link invariants. Compos. Math. 2009, 145, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, F.; Geer, N.; Patureau-Mirand, B. Quantum invariants of 3-manifolds via link surgery presentations and non-semi-simple categories. J. Topol. 2014, 7, 1005–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]