Abstract

The nonlinear Schrödinger equation is a classical nonlinear evolution equation with wide applications. This paper explores the asymptotic behavior of solutions to the nonlinear Schrödinger equation with non-zero boundary conditions in the presence of a pair of second-order discrete spectra. We analyze the Riemann–Hilbert problem in the inverse scattering transform by the Deift–Zhou nonlinear steepest descent method. Then we propose a proper deformation to deal with the growing time term and give the conditions for the series in the process of deformation by the Laurent expansion. Finally, we provide the characterization of the interactions between the solitary waves corresponding to second-order discrete spectra and the coherent oscillations produced by the perturbation. Numerical verifications are also performed.

1. Introduction

1.1. Introduction to Nonlinear Schrödinger Equation

We consider the Schrödinger equation

where . For simplicity, we substitute into (1) and get a convenient form

The nonlinear Schrödinger Equation (2) can be reformulated in form of the compatibility condition of the Lax pair

where is a 2 × 2 matrix-valued function, and

In the above, I is the identity matrix, is the spectral parameter and denotes the complex conjugate of q.

In fact, when (3) holds, the compatibility condition leads to the nonlinear Schrödinger Equation (2) for , regardless of the value of k. Such treatment stems from the inverse scattering transform invented by Gardner et al. in 1967 for the Korteweg–de Vries equation [1]. Lax generalized it to integrable equations, and Zakharov and Shabat proved the integrability of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation [2], thus introducing the inverse scattering transform method into the study of this equation. The original inverse scattering transform method requires solving the Gelfand–Levitan–Marchenko integral equation [3,4]. Zakharov simplified the solution of the inverse scattering problem based on the Riemann–Hilbert problem [5].

The spectra of the inverse scattering transform refer to the set of all parameter values for which the eigenfunctions of the Lax pair are bounded. The spectra of the inverse scattering transform are defined in the complex plane and are divided into two types: discrete ones and continuous ones. The continuous spectrum corresponds to perturbations, while the discrete ones give rise to solitary waves. When both spectra coexist, the study of the asymptotic behavior of the equation solutions can help understand the properties of solutions to the nonlinear Schrödinger equation. In the zero background field, study of such asymptotic behavior was first conducted by Zakharov et al. [3,6]. After this, Ablowitz et al. demonstrated that the solution decays at a rate of in the presence of continuous spectrum [7]. Deift and Zhou introduced the Deift–Zhou nonlinear steepest descent method to analyze the asymptotic behavior of Riemann–Hilbert problems with oscillatory terms to study the modified KdV equation [8]. Subsequently, this method has been extended to the study of KdV equations [9], Toda lattices [10], and the nonlinear Schrödinger equation with a zero background [11,12,13]. In recent years, the steepest descent method was further developed for studying the nonlinear Schrödinger equation [14,15].

For the nonlinear Schrödinger equation with a non-zero background, Biondini and Mantzavinos [16] used the Deift–Zhou nonlinear steepest descent method to study the asymptotic behavior of the perturbation corresponding to continuous spectra in the absence of a discrete spectrum. They found that such perturbation exhibits consistent asymptotic behavior, propagating at a fixed velocity to both sides and forming modulated elliptic waves in the central wedge-shaped region. Biondini et al. [17,18] also investigated the case with both continuous spectrum and a pair of first-order discrete spectra with the latter corresponding to solitary waves. They discovered that the perturbation again propagates asymptotically at a fixed velocity to both sides. Depending on the position of the first-order discrete spectra, the solitary waves either pass through the region of perturbation or interact with it. Biondini transformed the Riemann–Hilbert problem near the first-order discrete spectra into the form of a piecewise analytic function with jumps and then studied the asymptotic behavior of the solutions obtained from the piecewise analytic function Riemann–Hilbert problem. However, this transformation cannot be extended to higher-order discrete spectra.

In this paper, we directly study the Riemann–Hilbert problem for piecewise meromorphic functions with series conditions, using the Deift–Zhou method to give the asymptotic behavior of the solutions to the nonlinear Schrödinger equation in the presence of a continuous spectrum and a pair of second-order discrete spectra. First, we formulate the specific Riemann–Hilbert problem. Then we use the Deift–Zhou nonlinear steepest descent method to deform the Riemann–Hilbert problem, providing the series conditions in the deformation process via the Laurent series. We also propose the deformations which can address the temporal terms approaching infinity in the series conditions. Finally, we give the asymptotic behavior of the nonlinear Schrödinger equations.

1.2. Results and Discussion

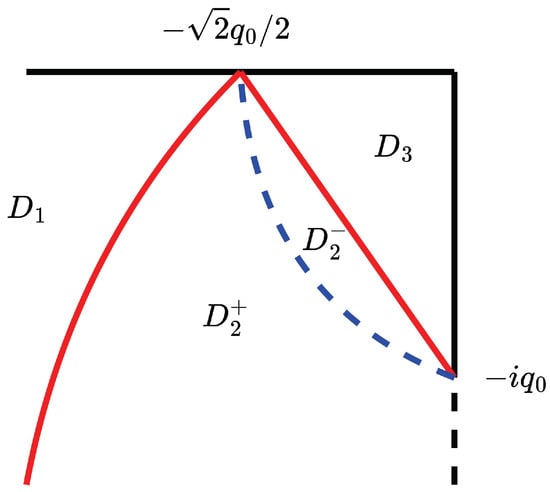

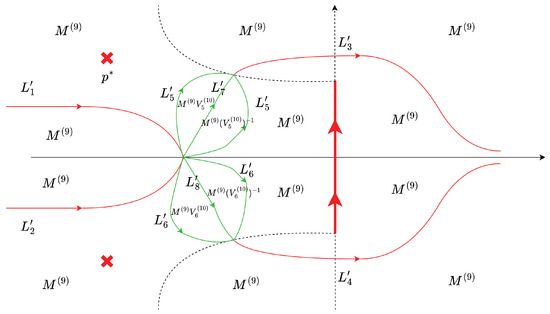

In this paper, we only consider the case of the second-order discrete spectrum parameter k in the left half of the complex plane. The situation for the right half plane is similar. Since discrete spectra always appear in pairs, we assume that the second-order discrete spectrum lies in the third quadrant of the k-complex plane, with its conjugate also a discrete spectrum. As shown in Figure 1, the third quadrant is divided into four regions. The boundaries of and are composed of the coordinate axes and the two solid red curves , with a single branch of . The boundaries of and is the dashed blue curve , with determined by (131) later. If special singularities exist near the origin, complexities arise, and we do not discuss such case. We focus on the asymptotic behavior when and . The main results are as follows.

Figure 1.

Four regions in k-complex plane.

Define , and .

Theorem 1.

When there is a continuous spectrum and a second-order discrete spectrum , there exists a

The asymptotic behavior is as follows.

- 1.

- When , where is a real number defined by (85).

- 2.

- When , where , arg denotes the phase angle.

- 3.

- 4.

- When ,

- 5.

- When , .

It is noted that when there is no continuous spectrum, represents the propagation speed of the solitary wave corresponding to the second-order discrete spectrum in an asymptotic sense. In Theorem 1, describes the asymptotic behavior of the solution to the left of the solitary wave and describes that to the right of the solitary wave.

Theorem 2.

When there is a continuous spectrum and a second-order discrete spectrum , there exists defined by . Here is defined by (132). The asymptotic behavior is as follows.

- 1.

- When ,

- 2.

- When ,

- 3.

- When ,

- 4.

- When ,

- 5.

- When , .

Theorem 2 uses as the dividing line to characterize the asymptotic behavior rather than in Theorem 1. That is, the solitary wave is influenced by the perturbation and changes the propagation speed . Notice that it slows down, as .

Now we explain Theorems 1 and 2 from the perspective of perturbations. To begin with, we briefly review the asymptotic behavior presented in [16] where only a perturbation corresponding to the continuous spectrum presents.

- 1.

- When ,

- 2.

- When ,

- 3.

- When ,

- 4.

- When , .

By comparison, it is evident that the presence of the second-order discrete spectrum has altered the perturbation in Theorems 1 and 2. We discuss the additional terms and . On the one hand, causes a fixed phase shift in the perturbation. In contrast to this conclusion, the first-order soliton only induces a phase shift of [16]. On the other hand, affects the asymptotic behavior of the amplitude of . For the perturbation corresponding to the continuous spectrum, we have the following observation:

- 1.

- When ,

- 2.

- When ,

- 3.

- When ,

From Theorem 1, as for , the modulus of is as follows.

- 1.

- When , it holds that

- 2.

- When , it holds thatwhere sn is the elliptic sine function.

- 3.

- When ,

Comparing (13) and (14), we observe that causes a change in the phase of the elliptic sine function. The presence of the second-order discrete spectrum leads to a spatial translation in the amplitude of the disturbance, but the overall shape remains unchanged.

From Theorem 2, when , the modulus of is as follows.

- 1.

- When ,

- 2.

- When ,

- 3.

- When ,

- 4.

- When ,

In this situation, for , the amplitude of the disturbance remains unaffected. For , the amplitude of the perturbation undergoes spatial translation.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

- Section 2: Introduction to the Riemann–Hilbert problem in the context of inverse scattering transform.

- Section 3: Analysis of the asymptotic behavior of the time terms in the jump conditions to determine the matrix factorization method used in the Deift–Zhou nonlinear steepest descent method.

- Section 4: Deformation of the Riemann–Hilbert problem and analysis of the main component of the solution to the deformed problem. These lead to the asymptotic behavior of the solution to the nonlinear Schrödinger equation, hence proves Theorems 1 and 2.

- Section 5: Numerical simulations to validate the results.

2. Riemann–Hilbert Problem

Consider the asymptotic scattering problem at infinity

where The eigenvalues of are , where

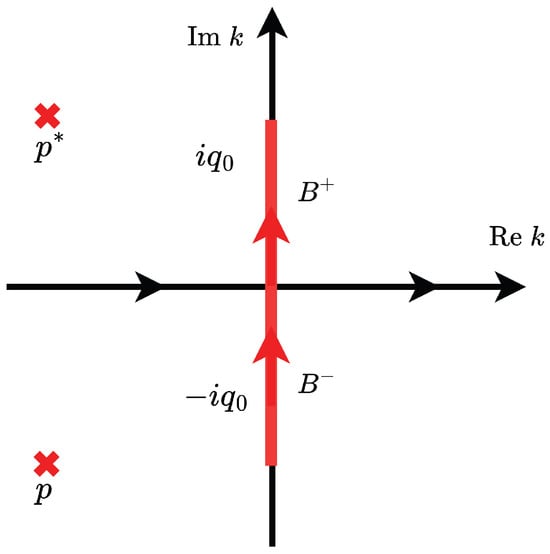

The multi-valued function in the k-complex plane takes as branch points. We map the Riemann surface onto the first sheet of the complex plane and take one single-valued branch . As shown in Figure 2, we introduce a branch cut which is oriented from to . Denote , where and . Then is a single-valued holomorphic function on , with a discontinuity on B.

Figure 2.

The branch cut and the pair of second-order discrete spectra p and . The orientation of the limit is characterized by the arrow’s direction. The left limit of the function is defined as the limit acquired when the function approaches the oriented curve from its left orientation, while the right limit corresponds to its right orientation.

Thus, defining as its right limit on B, we get

This gives , where denotes the left limit of on B. Thus, the eigenvector matrix corresponding to the eigenvalues is

We denote

Because , the solution of (17) is

where C is a second order column vector. For , define the Jost solutions , namely, the simultaneous solutions as :

where . Next, modify the Jost solutions (23) by

where are column vectors. Substituting the modified Jost solutions into (3) gives the Volterra integral equation satisfied by the Jost solutions:

The existence and analyticity of the modified Jost solutions can be proved by Neumann series [19]: for , , the modified Jost solutions exist and are unique. For , where , , and can be analytically extended to from . For , where , , and can be analytically extended to from .

If and only if , both exist. So is the continuous spectrum of the inverse scattering transform.

Both are solutions of (3), so there exists a scattering matrix ,

Here

We denote and then

In this way, is analytically extended to .

In the following discussions, with a little abuse of notation, we denote the right limit of on B still as . Biondini [16] proposed the jump condition of the modified Jost solutions

The jump condition of the scatteing matrix coefficient a is

Up to this point, the jump conditions required for the Riemann–Hilbert problem are given. Thus, we introduce a piecewise meromorphic function

Similar analysis applied to the case shows . Define the reflection coefficient , the jump condition of is given as

Meanwhile, the jump condition for is given by the jump conditions of the modified Jost solutions (29) and that of the scattering matrix coefficient (30), namely,

In addition, we need to precise the asymptotic condition and series condition to analyze the Riemann–Hilbert problem. It is shown in [19] that the asymptotic condition of the Riemann–Hilbert problem is

The expansion of at infinity shows that the solution of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation is obtained from

In , are analytic and has a second-order zero at the discrete spectrum p, namely . Performing Laurent expansion around as follows. In the following discussions, ′ denotes derivative with respect to k.

Therefore the conditions of Laurent series are

where denotes the coefficient of the second term in the Laurent series. Consider , according to (28a), we have

so there exists a constant , making

Substituting into (28a), we have

So, there exists a constant , making

Thus, the series conditions of at can be written as

where

The series conditions of at then read

where

3. The Asymptotic Behavior of the Time Terms

In this section, we study the asymptotic behavior of the time terms for the Riemann–Hilbert problem. The exponential terms appear in the jump conditions (33), (34) and the series conditions (48)–(52). We investigate the asymptotic behavior on the line with a fixed slope in plane. In this case,

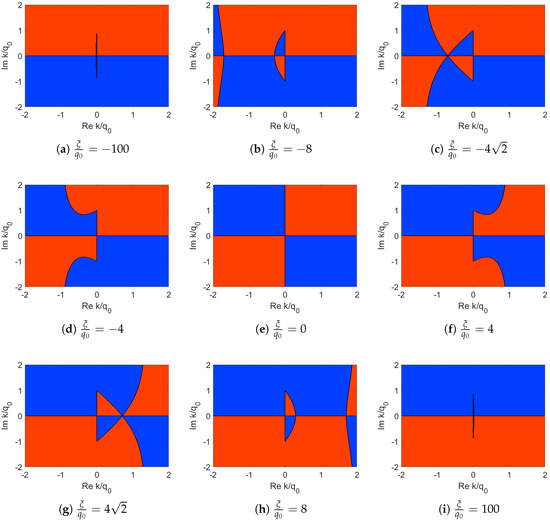

We write as without making confusion. To use the Deift–Zhou steepest descent method for analyzing the asymptotic behavior, we consider the sign structure of

which is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Sign of as increases from to . Red: , Blue: .

Considering the symmetry of , we only need to study the sign structure of for . Denote and . When , the curve intersects at two points

where is to the left of . When , the curve intersects at one point . When , the curve has no intersection with , and is directly connected to B.

4. Proof of Theorem 1

Consider . As Figure 1 shows, the right boundary of is the curve . So, there exists a value of , such that the curve goes right through the discrete spectrum, namely . Substituting it into (54), we have

Here is the asymptotic propagation speed of the solitary wave solution corresponding to the second-order discrete spectrum. Next, following [18], we divide into three intervals , and , and analyze the asymptotic behavior under these three conditions separately.

4.1.

When , p is to the right of . The two intersection points and , as (55) shows, are between and the real axis. Although there is a sign change near , as shown in Figure 3, it only occurs in the small region from to B. Therefore, we only decompose the jump matrix differently near and ensure that the jump curve crosses this small region in subsequent transformations, which does not affect the decomposition terms of the time component on the curve.

The jump matrix in the jump condition on is decomposed as

where

The jump matrices in the jump condition on B are decomposed as

where is the left and right limit of , and are those of . Moreover, is a constant matrix

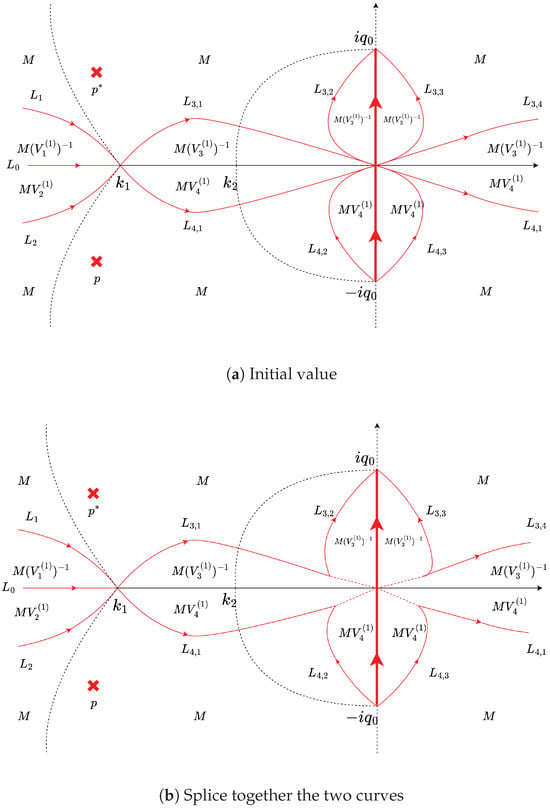

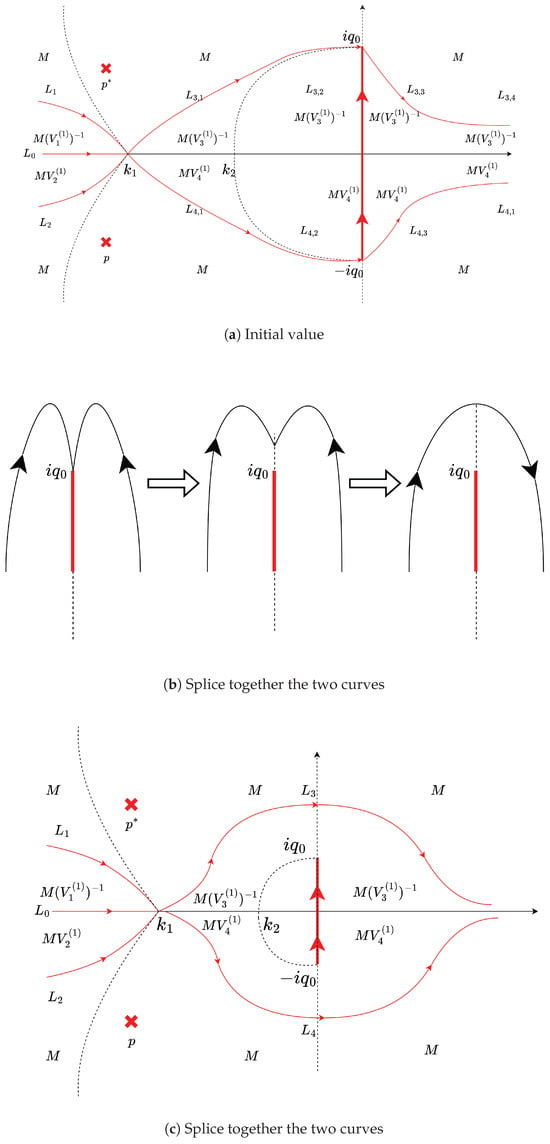

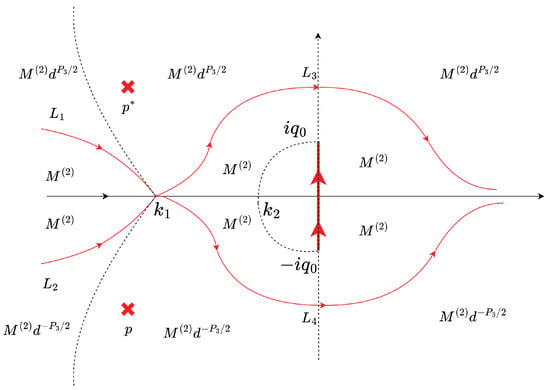

First Deformation. Define the function matrix as shown in Figure 4a. The dashed line represents . Since the jump matrices of and are the same, if two curves extend a small portion very close to the origin, the jump changes of the two curves cancel in this small segment, making the function still continuous. This is equivalent to splicing the two curves together. Next, we adjust the values in each region. The adjustment enables the curves formed by and to continue extending outward until they no longer include the region where the sign change occurs from to B. Similarly, we splice and as shown in Figure 4b and Figure 5a. As depicted in Figure 5b, continue using curves with the same jump matrices at both endpoints of B to cancel jumps and move the curve upward, combining and . Eventually, we obtain a curve that starts from , bypasses B, and goes to infinity on the right. Similarly is obtained in the lower half-plane. The values of the region after the first deformation are shown in Figure 5c.

Figure 4.

Diagram of the first deformation 1, substep 1. redHere the dashed lines denote the curve .

Figure 5.

Diagram of the first deformation, substep 2.

The jump conditions are

where

The function value at p and remains unchanged, so the series conditions for the nth deformation are written formally as

The asymptotic condition is

Second Deformation. The jump along can be removed by the transformation

where is analytic in , and satisfies the Riemann–Hilbert problem

The exact solution of (66) can be obtained by the Plemelj formula

The jump conditions turn to

where

Because is analytic at and , the derivatives of exist at these two points.

We denote

Now, the matrices in the series conditions (63) are

The asymptotic condition is

Third Deformation. The function can be eliminated from the jump matrices by defining as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Diagram of the third deformation.

At this time, the jump conditions are

where

Denote

Then, the coefficient matrices in the series conditions are

The asymptotic condition is

Fourth Deformation. can be turned to a constant matrix by a transform

where is analytic in and satisfies the Riemann–Hilbert problem

The exact solution of (79) obtained by the Plemelj formula is

At this time, the jump conditions are

where

Denote

Then, the coefficient matrices in the series conditions are

Define

Because , the symmetry holds , namely, .

At this time, the asymptotic condition is

Substituting the progress of the deformation into (36), we have

Now the jump matrices of (74) except for tend to zero as and the coefficient matrices in (84) tend to zero as . So when , the dominant component of , denoted as , satisfies the following Riemann–Hilbert problem

The solution can be obtained by the Plemelj formula after diagonalizing the matrix function

Because is a real number for , we have . This resembles the asymptotic result when there is only a continuous spectrum without a discrete spectrum [16]. In this case, only the time terms in the elimination of the jump conditions are considered in the deformation, while the coefficients of the series conditions automatically vanish when . The addition of the series conditions has no impact on the result. However, the situation is different for , because then the adjustment of the time terms in the series conditions must be considered.

4.2.

Fifth Deformation. When , p is to the right of . As , the time terms in the series conditions tend to infinity. They can be adjusted by the transformation

where . The jump conditions become

where

The asymptotic condition is

We still need to analyze the series conditions.

The Laurent expansion of at is

where

Thus, the Laurent expansion of at is

We use subscript j to represent the columns of the matrix, i.e., . According to the series conditions (84), expansion of goes down to the second-order. We perform a Laurent expansion of around and substitute it into the series conditions. For the sake of notation simplicity, x and t are omitted in the following expressions.

Therefore, we have the following series conditions

and

Similarly, we perform the Laurent expansion of around ,

Therefore, we have the series conditions

Similarly, we may show that

Then the corresponding coefficient matrices are

Sixth Deformation. Similar to the fourth deformation, can be turned to a constant matrix by the transformation

where is analytic in , and satisfies the Riemann–Hilbert problem

The exact solution of (108) can be obtained by the Plemelj formula

At this time, the jump conditions are

where

Let

the coefficient matrices in the series conditions are

Define

The asymptotic condition is

The solution of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation is

4.3.

The curve does not intersect the real axis. Following Biondini’s approach to study the asymptotic behavior with continuous spectra [18], we assume that represents an undetermined point on the negative real axis, with as the independent variable. We shall replace the position of in the first deformation with for the subsequent transformations.

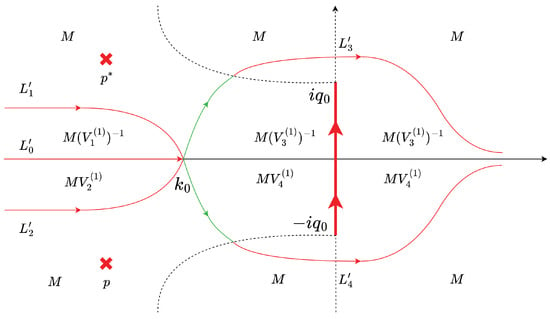

Seventh Deformation. Similar to the first deformation, the values of different regions after the seventh deformation are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Diagram of the seventh deformation.

The jump conditions are

where the jump matrices are the same as (62). The value of the function at p and remains unchanged, so the series coefficients are the same as (48) and (50), namely, .

The asymptotic condition is

Eighth Deformation. Similar to the second deformation, the jump along can be removed by the transformation

The jump conditions become

where the step matrices are similar to those in the second deformation (69), except is replaced by . The coefficient matrices in the series conditions are similar to (71), except that in is replaced by , giving .

The asymptotic condition is

Ninth Deformation. Similar to the third deformation, the function can be eliminated by defining as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Diagram of the ninth deformation.

The jump conditions are

where the step matrices are similar to those in the third deformation (74), except that is replaced by . The coefficient matrices in the series conditions are similar to (76), except that in is replaced by , giving .

The asymptotic condition is

Tenth Deformation. In Figure 8, the dashed line represents the equation . Therefore, in the green segment of and from to the dashed line, the time terms in the step matrices tend to infinity as . Decompose the jump matrices to deal with the time terms as follows

where

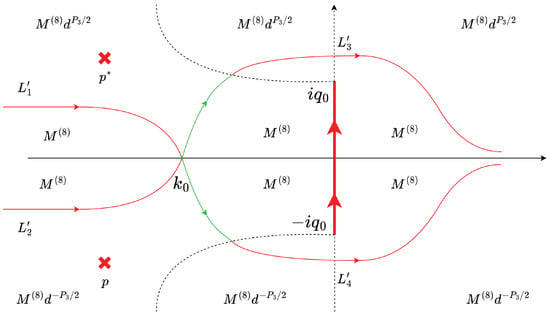

The values of are defined as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Diagram of the tenth deformation.

The jump conditions are

where , and other jump matrices are defined as (126). The coefficient matrices in the series conditions are the same as those in the ninth deformation.

Denote the intersection point of and as , and the intersection point of and above in . Let . Then the curve starts from , passes and reaches .

Eleventh Deformation. To eliminate the time terms growing to infinity in and , we assume that there exists a discontinuous function on B and . The transformation is

The jump conditions are

where

Here must satisfy the following conditions.

- 1.

- .

- 2.

- .

- 3.

- . This guarantees that uniformly tends to identity at the infinity point of k-plane.

- 4.

- The sign of is the same as that of around the origin, and .

In the proof of the asymptotic behavior with the continuous spectrum [18], Biondini pointed out that the existence of such requires certain conditions on and . More precisely, denote and , and their values are uniquely determined by the following system of equations

Here m is an auxiliary variable. These conditions actually determine the appropriate values of and . We note that determines the boundary between and in Figure 1, the parametric curve . We have

where

It is proven that takes the following jump conditions [18]

where real-valued

This tames the time terms in and to become oscillatory instead of diverging towards infinity. Define a real

Now the asymptotic condition is

The coefficient matrices in the series conditions are

It is noted that when , , . So the time terms of the series conditions tend to infinity as . Thus, they must be adjusted similar to the case with .

Twelfth Deformation. The dependence of k on B and can be eliminated in a similar way as the fourth deformation, namely,

where satisfies the following conditions

Here

The solution can be calculated using the Plemelj formula

The jump conditions are

where

Denote

Then the coefficient matrices in the series conditions are

Define

The asymptotic condition is

Thus, all time terms approaching infinity in the step condition have been eliminated, leaving only time terms approaching zero and oscillatory terms in .

Thirteenth Deformation. Similar to the fifth deformation, we take

The jump conditions are

where

Similarly, we define and get the series conditions of in the same way as the fifth deformation, but replacing by and replacing by .

In this way, the time terms in the series conditions have been adjusted, but and now depend on k. Therefore, the fourteenth deformation is carried out in a way similar to the sixth deformation to eliminate the dependence on k.

Fourteenth Deformation. The fourteenth deformation is

where satisfies the following conditions

where

The solution can be calculated by the Plemelj formula

The jump conditions are

where

For the sake of simplicity, denote

Then, the coefficient matrices in the series conditions are

Define

By transforming the integral onto the Riemann surface , we may evaluate the integral expression. The calculation yields .

Thus, the asymptotic condition is

So far, the jump matrices tend to zero uniformly as , and the coefficient matrices in (159) tend to the identity matrix as . So for , the dominant component of , denoted as , satisfies the following Riemann–Hilbert condition

When solving the asymptotic problem with continuous spectra, Biondini provided the solution to the Riemann–Hilbert problem (162) when [18]. Similarly, we can find the solution. For the sake of clarity, we introduce the following functions. Define

where is the third kind Jacobi theta function and , in which m is given by (131).

Let D represent the area enclosed by and the line from to . Define

where is a curve surrounding B, and the area enclosed by does not include .

Further define

Finally, the solution of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation is

We recall that is defined by (163), and m are defined by (131). Furthermore, , and are functions of , defined by (165), (154), (147), (141) and (136), respectively. Moreover, is defined by

So far, Theorem 1 has been proved when . When , after dealing with the time terms of the jump conditions, the time terms of the series conditions tend to infinity uniformly. When , the situation is the same as that when , and the asymptotic result is . When , the situation is the same as the case . Considering that the solution should be continuous when , the asymptotic result is given by (168). This finishes the proof for Theorem 1. In addition, we summarize the transformations and their purposes in Appendix A.

5. Proof of Theorem 2

The main difference between the situations and is that for , the curve does not go through the discrete spectrum, whereas for , there exists that satisfies . So we discuss as follows.

- 1.

- When , because there is no that can change the growth behavior of the time terms, the series conditions remain the same as the case . The series conditions do not introduce additional time terms tending to infinity, so the asymptotic solution of the equation is .

- 2.

- When , following the methods used in the seventh to twelfth deformations of the jump conditions, in the Riemann–Hilbert problem after the twelfth deformation, the time term replaces the previous time term . Since all the time terms in the series conditions at this point asymptotically approach zero, there is no need for additional processing of the series conditions. Therefore, there is no need for the thirteenth and fourteenth deformations, which are equivalent to the case where in the context of (168). As a result, the asymptotic solution of the equation is

- 3.

- When , the situation is the same as that for and . So the asymptotic behavior is the same as (168), leading to

- 4.

- When , the situation is the same as the case . We need to deal with the time terms of the series conditions and the jump conditions. Considering the solution should be continuous when , the asymptotic behavior of the solution is given by

- 5.

- When , the situation is the same as the case , so the asymptotic behavior is .

6. Numerical Verification

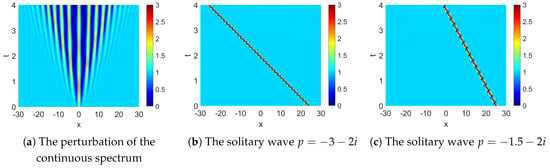

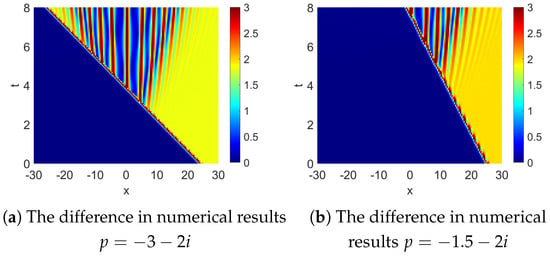

In this section, we validate Theorems 1 and 2 by numerical simulations for solitary waves corresponding to the second-order discrete spectra with perturbation corresponding to the continuous spectrum.

Numerical simulations are conducted using the pseudospectral method and a fourth-order Runge-Kutta exponential time differencing scheme [20,21]. The computational domain is , with spatial step size and time step size . The periodic boundary conditions are adopted. For numerical results within the subinterval , the above computational domain is sufficiently wide to eliminate numerical artifacts due to boundary reflection.

According to the conclusions presented in Section 1.2, when there is a second-order discrete spectrum, the perturbation corresponding to the continuous spectrum results in amplitude changes. In this section, we choose near the origin as the initial value for the perturbation corresponding to the continuous spectrum [16,22]. Local perturbations corresponding to the continuous spectrum have a uniform asymptotic behavior, and the specific form chosen does not affect the conclusions of the numerical simulation.

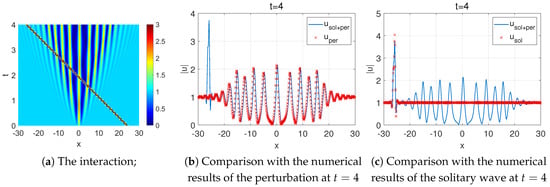

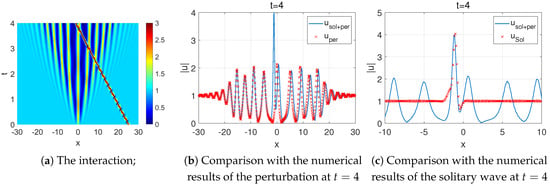

We take the solitary wave solutions corresponding to and at for the initial condition and verify Theorems 1 and 2. Denote the numerical results of the perturbation as , the numerical results of the solitary wave as and the numerical simulation results of the interaction between disturbances and solitary waves as .

In Figure 10, the subplot Figure 10a shows, the perturbation corresponding to the continuous spectrum propagates towards both sides at a fixed speed and create a modulated elliptic wave in the intermediate region. This is consistent with the asymptotic behavior (13). Subplots Figure 10b,c shows the solitary waves corresponding to and . In Figure 11a, the solitary wave propagates faster than the perturbation. Moreover, after the solitary wave enters the region the perturbation changes the amplitude of the perturbation. Figure 11b shows a comparison with the numerical simulation results of the disturbance at . As stated in Theorem 1, the amplitude on the right side of the solitary wave is roughly the same as the shape of the perturbation, albeit with some minor translations. Figure 11c shows a comparison between the numerical simulation results of the interaction and that of the solitary wave. The speed of the solitary wave remains unaffected.

Figure 10.

The numerical simulations of the perturbations and solitary waves.

Figure 11.

The numerical results for .

In contrast for , Figure 12a shows the case where the solitary wave propagates slower than the perturbation. After the solitary wave enters the region, the perturbation changes amplitude. Figure 12b shows a comparison with that of the disturbance at . As stated in Theorem 2, the amplitude on the left side of the solitary wave reproduces that of the perturbation without any interaction. However, the amplitude profile on the right side of the solitary wave only roughly reproduces the shape of the perturbation. Both have undergone some minor translations. Figure 12c shows a comparison between the numerical simulation results of the interaction and those of the solitary wave. The speed of the solitary wave becomes slower because the asymptotic behavior is divided by when , indicating that the velocity of the solitary wave is converted to after entering the perturbation.

Figure 12.

The numerical results for .

Figure 13 shows the difference between the numerical results of the interaction and those of the perturbation. In these two situations, there is no difference between the part of the perturbation which is faster than the solitary wave and the solitary wave. As Theorems 1 and 2 describe, this part of perturbation is not affected. It has neither phase offset nor amplitude offset in space.

Figure 13.

The difference in numerical results .

7. Discussions

This paper sheds light on the asymptotic behavior of solutions to the nonlinear Schrödinger equation in the presence of both the continuous spectrum and the second-order discrete spectra. By employing the Deift–Zhou nonlinear steepest descent method, we analyze the Riemann–Hilbert problem in the context of inverse scattering transform and examine the asymptotic behavior of the time terms in different regions of the complex plane. The paper presents a series of deformations to eliminate the time terms that tend to infinity along the curves in the Riemann–Hilbert problem. Through Laurent series expansions, the conditions during the deformation process are divided, and an appropriate deformation method is proposed to mitigate the divergent time terms.

In the end, the asymptotic behavior of the Riemann–Hilbert problem is characterized, indicating that when those appear both the perturbation corresponding to the continuous spectrum and solitary wave solutions corresponding to the second-order discrete spectra, the speed of the solitary wave remains unaffected if it is faster than the propagation speed of the perturbation. In this case, the phase of the perturbation undergoes a fixed offset, and its amplitude experiences spatial translation. On the other hand, if the speed of the solitary wave is slower than that of the perturbation, its velocity slightly decreases. Disturbances propagating faster than the solitary wave remain unchanged, while those propagating slower than the solitary wave undergo a fixed phase shift and spatial amplitude translation.

Finally, numerical experiments validate the conclusions presented in Theorems 1 and 2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, All authors; methodology, All authors; software, C.Z.; validation, C.Z.; formal analysis, C.Z.; investigation, B.W. and C.Z; resources, All authors; data curation, B.W. and C.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Z.; writing—review and editing, B.W. and S.T.; visualization, B.W. and C.Z.; supervision, S.T.; project administration, S.T.; funding acquisition, S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by NSFC the Excellence Research Group Program for multiscale problems in nonlinear mechanics (Grant No. 12588201).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Summary of deformation steps and their purposes.

Table A1.

Summary of deformation steps and their purposes.

| Transformation | Purpose |

|---|---|

| 1st deformation | Construct the jump region through merging and shifting. |

| 2nd deformation | Remove the jump on via a scalar function . |

| 3rd deformation | Eliminate the factor from the jump matrices. |

| 4th deformation | Introduce to turn the jump on B into a constant matrix. |

| 5th deformation | Reorganize the Laurent expansion at the second-order discrete spectra to eliminate the exponential time terms. |

| 6th deformation | Introduce to turn the jump on B into a constant matrix. |

| 7th deformation (for ) | Rearrange the contour for so the jump region follows the sign of . |

| 8th deformation | Remove the jump on via a scalar function . |

| 9th deformation | Eliminate the factor from the jump matrices. |

| 10th deformation | Add arcs along and split jumps into growing and decaying parts. |

| 11th deformation | Introduce to replace exploding factors in and . |

| 12th deformation | Use a scalar transform to remove the dependence of k on B and . |

| 13th deformation | Use a scalar function to reorganize the series at the second-order discrete spectra to eliminate the exponential time terms. |

| 14th deformation | Introduce to remove the dependence of k on B and . |

References

- Gardner, C.S.; Greene, J.M.; Kruskal, M.D.; Miura, R.M. Method for solving the Korteweg-de Vries equation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1967, 19, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabat, A.; Zakharov, V. Exact theory of two-dimensional self-focusing and one-dimensional self-modulation of waves in nonlinear media. Sov. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 1972, 34, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Ablowitz, M.J.; Segur, H. Solitons and the Inverse Scattering Transform; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. Nonlinear Waves in Integrable and Non-integrable Systems; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Novikov, S.; Manakov, S.V.; Pitaevskii, L.P.; Zakharov, V.E. Theory of Solitions: The Inverse Scattering Method; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Segur, H.; Ablowitz, M.J. Asymptotic solutions and conservation laws for the nonlinear Schrödinger equation II. J. Math. Phys. 1976, 17, 710–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, V.; Manakov, S. Asymptotic behavior of non-linear wave systems integrated by the inverse scattering method. Sov. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 1976, 44, 106. [Google Scholar]

- Deift, P.; Zhou, X. A steepest descent method for oscillatory Riemann-Hilbert problems. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 1992, 26, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deift, P.; Venakides, S.; Zhou, X. The collisionless shock region for the long-time behavior of solutions of the KdV equation. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 1994, 47, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamvissis, S. On the long time behavior of the doubly infinite Toda lattice under initial data decaying at infinity. Commun. Math. Phys. 1993, 153, 479–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deift, P.; Zhou, X. Long-time behavior of the non-focusing nonlinear Schrödinger equation, a case study. New Ser. Lect. Math. Sci. 1994, 5, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham, R.; Venakides, S. Long-time asymptotics of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation shock problem. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 2007, 60, 1349–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DE Monvel, A.B.; Kotlyarov, V.P.; Shepelsky, D. Focusing NLS equation: Long-time dynamics of step-like initial data. Int. Math. Res. Not. 2011, 2011, 1613–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, R.; Liu, J.; Perry, P.; Sulem, C. Soliton resolution for the derivative nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Commun. Math. Phys. 2018, 363, 1003–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Fan, E. Soliton resolution for the short-pulse equation. J. Differ. Equ. 2021, 280, 644–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondini, G.; Mantzavinos, D. Long-time asymptotics for the focusing nonlinear Schrödinger equation with nonzero boundary conditions at infinity and asymptotic stage of modulational instability. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 2017, 70, 2300–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, M.; Biondini, G. On the focusing non-linear Schrödinger equation with non-zero boundary conditions and double poles. IMA J. Appl. Math. 2017, 82, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondini, G.; Li, S.; Mantzavinos, D. Long-time asymptotics for the focusing nonlinear Schrödinger equation with nonzero boundary conditions in the presence of a discrete spectrum. Commun. Math. Phys. 2021, 382, 1495–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondini, G.; Kovačič, G. Inverse scattering transform for the focusing nonlinear Schrödinger equation with nonzero boundary conditions. J. Math. Phys. 2014, 55, 031506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.M.; Matthews, P.C. Exponential time differencing for stiff systems. J. Comput. Phys. 2002, 176, 430–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Tang, S. Transparent boundary condition for simulating rogue wave solutions in the nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Phys. Rev. E 2022, 106, 055302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biondini, G.; Mantzavinos, D. Universal nature of the nonlinear stage of modulational instability. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 043902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).