Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology is marked by the deposition of amyloid-β plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau neurofibrillary tangles. This pathology begins years before the first clinical symptoms emerge and progresses through several stages before clinical diagnosis. AD’s pathology alters the brain’s functional connectivity (FC) patterns and these altered FC patterns may serve as imaging markers to diagnose and assess the progression of AD. In this review, we summarize the recent literature investigating connectome alterations across the AD spectrum, spanning preclinical, prodromal, and clinical stages. We identify specific regions and functional connections that are altered across different stages of AD and discuss their relevance to cognition. We also highlight the potential of connectome-based predictive modeling as an individual-specific method in the quest for early diagnosis of AD. The default mode network (DMN) shows significant changes across stages, and its core hubs consistently exhibit reduced connectivity with the medial temporal lobe in association with disease pathology. From a dynamic FC point of view, the flexibility of different networks, especially DMN, was reduced as a result of AD onset and persisted across the stages. These disruptions were also linked to reduced cognitive performance, particularly in domains such as memory and executive function. By bringing together evidence on both disease-specific and stage-specific alterations in FC, this review aims to identify patterns that are most informative for understanding AD progression and their potential for advancing early diagnosis.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive brain disorder that leads to worsening cognitive impairment, memory deterioration, and difficulties carrying out everyday tasks [1]. This neurological condition is the most common form of neurodegenerative disorder [2], affecting approximately seven million people in the United States in 2025 [3]. With the increase in life expectancy, it is crucial to have a deep understanding of AD’s pathology and potential biomarkers at different AD stages to enable the identification of high-risk individuals, early diagnosis, and timely interventions to slow disease progression [4].

AD is defined by two neuropathological features: the accumulation of extracellular amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and the formation of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles composed of abnormally aggregated tau protein [5], both of which start decades prior to the first clinical manifestations [6]. Such asymptomatic buildup gives rise to the preclinical stage, in which individuals remain cognitively unimpaired or report only subjective cognitive decline (SCD), a self-perceived worsening of cognition despite normal pathophysiological test performance [7,8,9]. As the disease advances, it progresses into the prodromal stage, which is marked by the same pathological hallmarks together with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a condition characterized by measurable deficits in memory or other cognitive domains that do not yet substantially interfere with daily functioning [10]. With further progression, the condition enters the overt or clinical stage of AD, characterized by both pathological hallmarks along with dementia symptoms, including marked memory loss, reduced independence in daily activities, and broader cognitive decline.

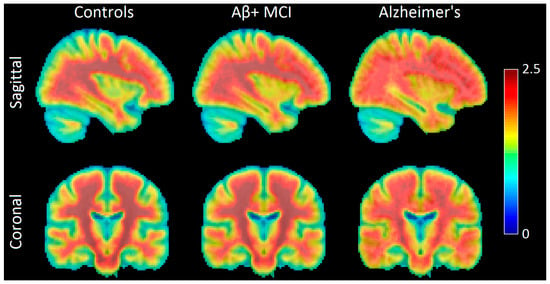

Normally, Aβ is present at relatively high levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), but as increasing amounts become sequestered into insoluble plaques in the brain in Aβ pathology, CSF Aβ levels fall, reflecting this redistribution from soluble to deposited forms [11]. Aβ accumulation in tissue can be assessed using positron emission tomography (PET) radioligands that bind to Aβ plaques, such as AV-45 (florbetapir) [12], or Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) [13]. A comparison of Aβ deposition between a control population, a prodromal AD population, and overt AD is shown in Figure 1. Despite such known patterns, Aβ accumulation alone may not serve as a reliable biomarker as it also can occur in normal aging [14]. Recent studies found that Aβ deposition is associated with changes in brain network characteristics such as functional connectivity (FC) patterns [15] and structural integrity [16], which shows the potential of such network alterations in providing additional insight into the disease’s mechanism.

Figure 1.

Sagittal and coronal PET images showing amyloid-β (Aβ) deposition in the brains of normal controls (NCs), Aβ-positive mild cognitive impairment (Aβ+ MCI) patients, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients. Aβ deposition occurs first in the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes and then spreads to the hippocampus and amygdala. Individuals with MCI and Aβ deposition are highly likely to progress to overt AD. The color bar indicates AV45 uptake (Aβ deposition), with warmer colors (red) representing higher values of AV45 uptake and cooler colors (blue) representing lower values. Image created using participants from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). The ADNI database can be found at adni.loni.usc.edu (accessed on 2 June 2025).

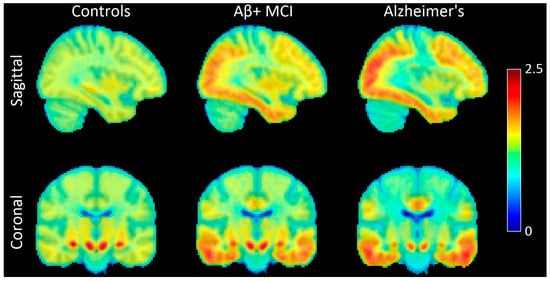

AD is also indicated by tau hyperphosphorylation and tangle formation [17], reflected by elevated CSF total tau (t-tau) and phosphorylated tau (p-tau), along with positive tau-PET cortical accumulation [18,19]. Tau-PET radiotracers (e.g., 18F-AV1451) enable in vivo visualization and quantification of these neurofibrillary tangles. An increase in tau-PET uptake has been reported in individuals with MCI or AD relative to normal controls (NCs) [11,20,21,22]. A comparison of AV-1451 uptake across the AD spectrum is shown in Figure 2. Given the decreased CSF levels of Aβ and increased p-tau in the CSF as the disease progresses, the ratio of Aβ/p-tau has recently been introduced as a biomarker to compare the effectiveness of different AD treatments [23].

Figure 2.

Sagittal and coronal images showing AV-1451 uptake patterns in the brains of normal controls (NCs), Aβ-positive mild cognitive impairment (Aβ+ MCI) patients, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients. The first sites that show accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau are in the medial temporal lobe for MCI patients. Tau then spreads to more regions and covers parts of the lateral occipital and temporal lobes at the MCI stage. At the overt AD stage, we see high accumulation of tau in areas such as the precuneus and medial prefrontal cortex. Image created using participants from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). The color bar indicates AV1451 uptake (tau deposition), with warmer colors (red) representing higher values of AV1451 uptake and cooler colors (blue) representing lower values. Image created using participants from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI database (adni.loni.usc.edu; accessed on 2 June 2025)).

SCD is associated with an elevated risk of progressing on the AD spectrum [24]. In patients with SCD, neuronal loss associated with Aβ and tau accumulation may lead to cognitive decline and the development of prodromal AD (AD biomarker positive with MCI). Patients with SCD have a conversion rate from SCD to MCI of 27% over 4 years [25]. Thus, cognitive decline associated with SCD may reflect functional or structural brain changes that precede more severe cognitive symptoms [26]. Identifying SCD-related alterations in brain architecture is critical for the development of early stage diagnostic or progression markers that can be used as enrollment criteria or outcome measures in clinical trials [27].

Preclinical individuals may progress to prodromal AD, characterized by amnestic MCI (aMCI) which is associated with memory loss [9,28]. Recognizing and characterizing MCI and its subtypes is particularly valuable for AD research, as it represents an intermediate stage where pathological changes are evident but dementia has not yet developed. Importantly, MCI has been associated with numerous markers absent in normal brains, including altered FC patterns [29], and neurodegeneration evidence [30,31], each offering potential insights into the underlying pathology.

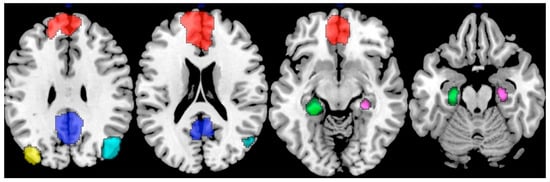

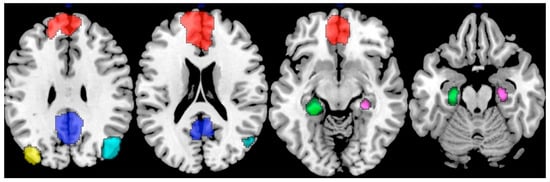

Various individual-specific factors such as age, sex, environmental experience, genetics, independent of levels of Aβ and tau, affect the pathological progression [32]. This heterogeneity of the neuropathological features encourages investigation of personalized biomarkers that provide evidence to distinguish different preclinical/clinical stages. One such promising biomarker is the whole-brain functional connectivity pattern, which can be derived from electroencephalography (EEG), magnetoencephalography (MEG), and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). In EEG/MEG studies, connectivity is typically assessed by examining signal synchrony or coherence between brain regions within specific frequency bands [33], reflecting fast neural communication. In contrast, fMRI-based connectivity is quantified using correlations between regional Blood Oxygen Level-Dependent (BOLD) signals, providing spatially detailed mapping of large-scale network organizations. Throughout this review, we use the term “connectome” to refer to the fMRI-derived whole-brain functional connectivity and examine its alterations across the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum. The connectome encompasses several major functional networks, such as the default mode network (DMN, Figure 3), which supports internally directed cognition and memory processes [34]; the salience network (SN), involved in detecting and integrating relevant internal and external stimuli [35]; and the frontoparietal network (FPN), which underlies executive control [36]. FC metrics capture such network organizations by quantifying temporal correlations between the BOLD signals of different brain regions. Large-scale networks are typically identified using data-driven approaches like independent component analysis (ICA) [37] or voxel-wise clustering [38], which group together brain regions showing highly correlated activity patterns.

The connectome and changes to its network’s FC pattern have been used to predict various behavioral measures over the past two decades [39,40,41], and since the connectome is unique to each individual, it is also called the brain fingerprint [42]. Building on this individual-specificity, connectome-based predictive modeling (CPM) has emerged as a fully data-driven framework for identifying brain–behavior relationships at the individual level, without requiring predefined disease-related regions or group comparisons (see Section 5) [40,43,44]. Due to the high variability of the functional architecture across individuals [45], understanding disease-associated networks and FC disruptions is crucial to advances in connectome-based biomarker research. In doing so, many AD studies have investigated changes to different FC patterns associated with different stages of the disease [46,47,48,49,50], as well as the pathological markers. To relate Aβ-PET and tau-PET measures to FC patterns, regions showing elevated amyloid or tau burden are identified from PET scans, selected as regions of interest, and their connectivity profiles are then analyzed to determine how pathology relates to functional disruption [51,52].

Connectomes can be derived from both resting-state and task-based conditions; resting-state connectomes reveal intrinsic network organization, while task-based paradigms highlight connectivity patterns during task performance. Once measured, FC can be analyzed using static methods, which assume that FCs are stable across the scanning period, or dynamic methods, which assume that FCs change during a scan. In dynamic FC, BOLD time series are segmented into shorter windows and connectivity within each window is computed to capture time-varying network configurations. These windowed connectivity matrices can then be clustered into recurring connectivity “states,” allowing for the quantification of temporal properties such as dwell time (how long the brain remains in a given state) and transition frequency (how often it switches between states) [53].

In this review, we summarize resting-state connectome alterations across the AD spectrum, focusing on early and individualized markers of disease progression. We first examine FC changes in the preclinical stage, including cognitively normal individuals with Aβ or tau positivity and those with SCD. We then detail connectivity disruptions in MCI patients, distinguishing early versus late MCI as well as progressive versus non-progressive subtypes of MCI. Finally, we review FC alterations in clinically diagnosed AD and discuss how recent individualized approaches, especially CPM, may enable sensitive detection and tracking of pathological progression at the level of each subject’s unique connectivity profile. This individualized perspective, along with the consideration of distinct subpopulations across the disease continuum, offers a novel view of connectivity alterations and may help advance personalized approaches to early detection and monitoring in AD.

Figure 3.

Nodes representing the default mode network (DMN). The highlighted regions include the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC; red), posterior cingulate cortex (PCC; blue), left inferior parietal lobule (yellow), right inferior parietal lobule (cyan), left hippocampus (green), and right hippocampus (purple), each serving as a node contributing to the network’s functional integration. Adapted from ref. [54] under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).

2. Preclinical AD

2.1. Aβ-Related Changes

In preclinical AD, Aβ accumulation is well-associated with alterations in FC [55]. Aβ initially accumulates in high-degree hubs of the default mode network (DMN), including the posterior cingulate/precuneus, lateral parietal, and prefrontal cortices [5]. Evidence suggests that the early appearance of Aβ pathology may trigger a phase of within-DMN hyperconnectivity, potentially reflecting a compensatory mechanism [56]. With the continuation of Aβ accumulation and further progression of the disease, within-DMN hypoconnectivity becomes evident in the preclinical population, especially with tau pathology [5,57,58]. Consistent with this finding, a longitudinal study showed greater amyloid burden in the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC, a core hub of the DMN) was linked to lowered within-DMN connectivity, which was correlated with longitudinal memory decline [59].

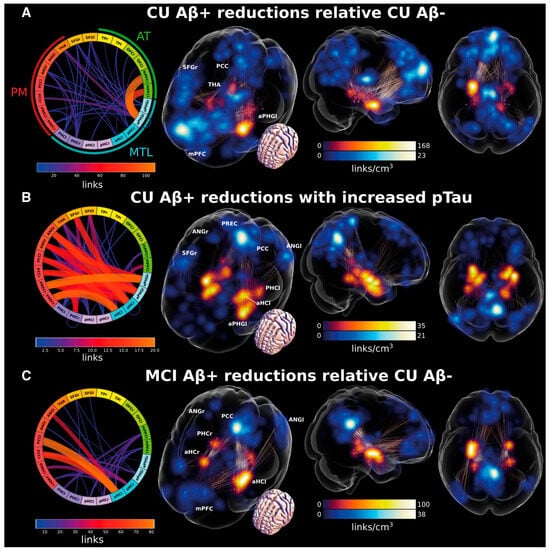

The medial temporal lobe (MTL), which contains memory-related structures like the hippocampus [60], is one of the first sites of tau deposition [61]. The MTL has been regarded as a part of the DMN [62], and it is a key focus of AD biomarker research. One study showed that for cognitively unimpaired subjects with Aβ accumulation (Aβ+), there was a decreased FC between the MTL and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC, one of the core hubs of the DMN), and this reduction was associated with lowered memory performance [63]. Specifically, they found that DMN–MTL FC, particularly between the parahippocampal gyrus and mPFC, was reduced in Aβ+ individuals compared to NCs (Figure 4A). These findings suggest that MTL FC patterns, particularly with DMN hubs, can distinguish NCs from Aβ+ individuals with normal cognition and may contain early network signatures linked to individual trajectories of disease progression.

Figure 4.

Changes in medial temporal lobe (MTL) functional connectivity (FC) with other cortical areas in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Brain glass images illustrate the density of FCs connected to the MTL (red) and to other regions of interest (blue), and the edges between blue and red regions in the glass brains show the FCs with significant changes. Connectograms (the circular diagrams) show the number of links (FCs) between each pair of regions that are significantly different across the conditions compared within each panel. Each panel shows which FCs were significantly different across the two conditions or populations compared. (A) Illustration of FCs with significantly reduced values for Aβ+ in cognitively unimpaired (CU) subjects compared to Aβ− CU controls. (B) FCs that show reduced strength in Aβ+ CU individuals when tau pathology (p-tau) increases. (C) Illustration of FCs with reduced values for Aβ+ MCI subjects compared to Aβ− CU controls. aHC = anterior hippocampus; ANG = angular gyrus; aPHG = anterior parahippocampal gyrus including entorhinal and perirhinal cortices; l = left; mPFC = medial prefrontal cortex; OFC = orbitofrontal cortex; PCC = posterior cingulate cortex; PHC = parahippocampal cortex; pHC = posterior hippocampus; PREC = precuneus; r = right; SFG = superior frontal gyrus; TP = temporal pole.; PM = posterior-medial system; AT = anterior-temporal system; MTL = medial temporal lobe. Adapted from ref. [63]. Licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

FC changes in Aβ+ cognitively unimpaired individuals are not confined to the DMN, but it spreads to other brain networks, including the SN, FPN, and the temporal cortex, reflecting a broader breakdown of large-scale functional organization [5,64]. From a whole-brain perspective, greater within-network connectivity has been associated with better cognitive performance. Conversely, network desegregation, characterized by increased connectivity between rather than within networks, was associated with poorer cognitive performance, suggesting a disruption of normal functional organization in AD [65]. In this context, the FPN may play a compensatory role, as increased within-network FPN connectivity has been associated with preserved cognitive performance despite Aβ burden [66].

Dynamic FC studies reveal AD-related reductions in network flexibility and increased rigidity in FC patterns [67]. These changes indicate that during a resting-state fMRI scan, functional networks show fewer fluctuations in their connectivity patterns, which reflects a loss of dynamic reconfiguration [68], a pattern that has been seen in preclinical AD as well. Specifically, Aβ+ individuals had lower dynamic FC variability in the DMN and dorsal visual network compared to Aβ− peers, and this reduced within-DMN flexibility was associated with poorer cognition [69].

2.2. Tau-Related Changes

In comparison to Aβ, FC associations with tau pathology are less explored, owing to the more recent development of tau-PET tracers. Tau deposition begins in the temporal lobe, specifically in the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus, in which AD-related atrophy has been observed as well [70,71]. As the disease progresses, tau spread continues and reaches brain regions like the precuneus (a core DMN hub) and mPFC in the overt stage (Figure 2). Such spread is hypothesized to be driven by the high inter-network connectivity of these hubs which facilitates the spread of tau across distinct regions [15]. Tau deposition is more strongly tied to cognitive impairment than Aβ [72], which highlights the need to better understand its role in AD pathology. In terms of the effects on FC, tau deposition impacts local FC patterns at deposition sites and causes reduced global and network efficiency [73], lowered connectivity between the core connectome hubs [74], and decreased within-network connectivity in different networks [75,76]. Tau-related effects on FC have been observed in the DMN, specifically for DMN core hubs [77] and between the precuneus and MTL [63]. In addition, reduced DMN FC was associated with increasing p-tau CSF values (Figure 4B). Investigating deeper into initial tau deposition sites, Harrison et al. observed a negative correlation between tau pathology and connectivity between the hippocampus and other MTL regions, and this was associated with worsened memory performance [78]. Such alterations impair inter- and intra-connectivity of the DMN, thereby affecting information processing in the brain [79].

As we observe in Figure 2, tau spreads across several brain networks other than the DMN as the disease progresses, including the limbic, visual, and SN, which disrupts the normal brain-wide FC pattern [76,80]. Regarding the preclinical population, higher tau burden was linked to increased connectivity in the retrosplenial cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex, a key hub of the SN [76]. As AD is defined by the presence of both Aβ and p-tau, investigating interactive effects of these hallmarks in relation to FC could provide valuable information on FC alterations in preclinical AD [5,81]. In doing so, in cognitively unimpaired older adults, one study showed that Aβ+ individuals with low tau burden showed stronger connectivity in the DMN and SN compared to Aβ-negative individuals. However, as tau accumulation increased over time, connectivity in these networks declined, suggesting that the within-network hypoconnectivity in preclinical AD is directly affected by tau burden [56]; a similar effect as shown in brain-wide studies [82]. This suggests that tau is more closely linked to network disconnection, while Aβ might bring hyperconnectivity in specific regions.

There have been few studies that worked on dynamic FC changes in response to hyperphosphorylated tau accumulation. One study used dynamic multilayer FC and was able to predict tau pathology by measures of network integration from visual, default mode, limbic, and control networks [68]. Another recent study found that higher tau burden correlates with reduced flexibility of brain network dynamics for a cohort of African Americans, which is in line with the increased rigidity of the connectome that was observed in the Aβ-related changes [83]. This was the most evident with the MTL region, whose reduced network flexibility mediated poorer cognitive performance.

Based on the analysis provided here, the hypoconnectivity associated with local tau areas, especially between the MTL and DMN hubs, could be a promising avenue to evaluate an individual’s tau pathology [84]. Simultaneously, diminishing network flexibility, particularly in the MTL, may reflect a shared response to both tau and Aβ pathology and signal an individual’s progression toward more advanced disease stages.

2.3. Connectome Changes in SCD Subjects

Regarding the SCD subpopulation of preclinical AD, some studies have reported increased FC within the DMN and FPN compared to the NC [85], which is in the opposite direction of the reduced within-DMN connectivity in response to tau accumulation. It is hypothesized that such an effect could be an initial compensatory mechanism to resist cognitive loss [86,87,88]. Interestingly, increased within-DMN connectivity was linked to poorer cognition, suggesting that early hyperconnectivity in SCD may mark the onset of decline [89]. In agreement with these results, another study reported increased FC between the lateral parietal cortex (a core DMN node) and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (an executive function central region) in SCD patients, and explained the finding as an adaptive response aimed at preserving cognition [90]. However, this increase has been seen in the MCI stage as well, so it could be a protective mechanism against cognitive decline at various stages [91].

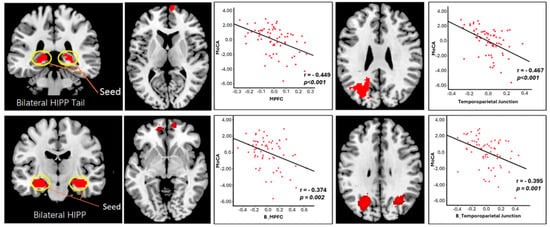

Multiple SCD studies report reduced FC between MTL regions and DMN hubs, including the mPFC and temporoparietal junction (TPJ), and these disruptions consistently correlate with poorer cognitive performance (Figure 5), underscoring MTL–DMN dysconnectivity as an early feature of self-perceived decline [92,93,94]. This trend of MTL-DMN FC decrease is not limited in the preclinical population, but it further continues to MCI and overt AD stages of the spectrum, suggesting that reviving this connection could partly resist the progression of AD [95]. Remarkably, one study used repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) targeted at the precuneus and was able to retrieve its normal FC, and this restoration was associated with improved cognition for SCD patients [96].

Figure 5.

Analysis of FC between hippocampal areas and cortical regions in relation to Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores. Scatter plots illustrate negative correlations between MoCA scores and: the bilateral hippocampal tail (top left; shown in red)—right mPFC (top middle; shown in red) FC, the bilateral hippocampal tail (top left; shown in red)—left temporoparietal junction (TPJ) (top right; shown in red) FC, the bilateral hippocampus (bottom left; shown in red)—bilateral mPFC (bottom middle; shown in red) FC, and the bilateral hippocampus (bottom left; shown in red)—bilateral TPJ (bottom right; shown in red) FC. Adapted from ref. [92]. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). Abbreviations: HIPP = hippocampus; mPFC = medial prefrontal cortex; B = bilateral.

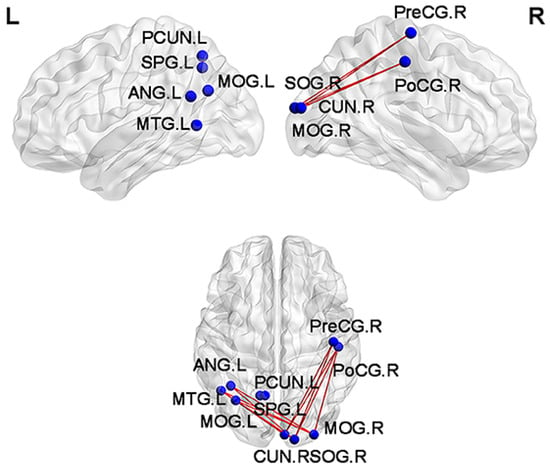

Even though DMN FCs are top classifiers between the SCD subjects and the NCs [97], there are other FCs that can distinguish these two groups. Huang et al. identified 14 FCs with significantly reduced values in SCD subjects compared to NCs [98] (Figure 6). Although some involved DMN hubs and medial temporal regions, many were outside the DMN, including visual and sensorimotor networks such as FC between the superior occipital gyrus and the precentral gyrus. Interestingly, the FC between these two regions was positively correlated with executive function, suggesting that non-DMN FCs could provide additional insight into SCD pathology. For example, the SN also consists of regions playing a major role in cognitive function, and it has been associated with an increased within-network FC that is correlated with cognitive function in SCD and aMCI patients [99]. In addition, the hyperconnectivity of the SN has been suggested to represent a compensatory mechanism in response to reduced within-DMN connectivity to protect cognition [100]. Together, these findings indicate that SCD may represent a transitional phase in which early compensatory increases in connectivity begin to fail, giving way to disrupted communication across large-scale networks as individuals progress toward symptomatic AD.

Figure 6.

Functional connections with reduced values for subjective cognitive decline (SCD) patients in comparison with normal controls (NCs). Blue spheres mark the brain nodes involved, while red edges visualize the reduced functional connections between them. SPG, superior parietal gyrus; ANG, angular gyrus; MOG, middle occipital gyrus; MTG, middle temporal gyrus; CUN, cuneus; SOG, superior occipital gyrus; PreCG, precentral gyrus; PoCG, postcentral gyrus; PCUN, precuneus; L, left hemisphere of the brain; R, right hemisphere of the brain. Adapted from ref. [98]. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Investigating dynamic FC, Wang et al. used seed-based analysis and found that the hippocampus–precuneus connection loses both magnitude (static FC) and flexibility (dynamic FC) in SCD patients [101]. Another study compared the dwell time of SCD and NC subjects in different states of connectivity, and observed that SCD subjects had a higher tendency to stay in hypoconnected brain states compared to NCs, while NC subjects’ dwell time in the hyperconnected states was higher than that of SCD patients [102]. Overall, decreased FC, particularly between the MTL and DMN hubs, together with reduced flexibility of these regions in dynamic FC, represent promising candidates for early AD biomarkers at the SCD stage.

3. Mild Cognitive Impairment

Across multiple studies, MCI has been associated with specific disruptions across large-scale functional networks [51,103]. The common findings showed reduced FC within the DMN, and in particular, between the PCC, mPFC, MTL, and hippocampus [49]. Specifically, there was a reduced FC between the anterior hippocampus and precuneus for Aβ+ subjects with MCI compared to cognitively unimpaired Aβ− individuals [63] (Figure 4C). In terms of the between-network connectivity of the DMN, there is a reduced anti-correlation between the DMN and the dorsal attention network (DAN) as well as disrupted FC between the DMN and SN, which shows a pattern of failed network segregation in MCI patients [104,105]. There are also disruptions in connectome patterns of aMCI patients between the DMN and cholinergic hubs of the brain, where the basal nucleus of Meynert’s (BNM)’s FC with the bilateral precuneus decreases for aMCI patients compared to NCs [106]. The BNM, a cluster of neurons in the basal forebrain [107], has a key role in regulating cognitive function and memory by participating in the production of acetylcholine [108]. Such disruption in the FC of two key cognition-related regions could be a potential biomarker of aMCI. In a within-group comparison of aMCI patients, one study compared the FC of aMCI patients who were biomarker+ (tau+ and Aβ+) and biomarker− (tau− and Aβ−) and found that biomarker+ individuals exhibited more severe and widespread disruptions in DMN–FPN connectivity than biomarker− aMCI patients [109].

MCI can be divided into early stage MCI (EMCI) and late-stage MCI (LMCI) [110,111], reflecting different levels of cognitive decline and disease progression [112]. LMCI is characterized by more widespread FC alterations involving the cerebellum, basal ganglia, DMN, DAN, and visual and cholinergic systems [113]. There was an increased FC between the right cerebellum and basal ganglia observed in LMCI patients compared to EMCI, highlighting the contribution of subcortical–cerebellar FCs at this stage of the disease [113]. There was also an increased between-network connectivity of a DMN hub (right superior frontal gyrus) with DAN, suggesting decreased DMN segregation in LMCI patients. On the other hand, there was decreased FC between the BNM and the lingual gyrus for LMCI patients compared to NCs [106]. These findings suggest that BNM connectivity and reduced network segregation both show promise as biomarkers that can distinguish EMCI and LMCI from normal aging, reflecting a mix of network breakdown and maladaptive reorganization in the prodromal stage of AD.

In investigations of FC patterns in MCI patients, there has been a special focus on subcortical and cerebellar regions. Abnormal long-range and short-range FC density has been reported in the cerebellum, basal ganglia, and the amygdala regions of MCI patients [114,115]. Importantly, these connections are correlated with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [116], demonstrating they are closely related to cognition [114]. In MCI, cerebellar regions such as crus II and lobule IX exhibit increased connectivity with other cerebellar areas, indicating early disruption of cerebellar network organization [117]. Previous work has shown that subcortical and cerebellar FC provides strong differentiation across individual connectomes, contributing substantially to the “brain fingerprint” uniqueness [53]. The distinctive connectivity patterns of subcortical and cerebellar regions, along with their strong contribution to differentiating MCI from healthy aging, highlight them as promising personalized biomarkers that could support early and precise detection of MCI.

Understanding the distinctions between the connectomes of SCD and MCI patients can also shed light on the transitional changes that mark the path of AD progression, especially since these stages are similar. The prefrontal cortex regions showed higher and more widespread FC in the MCI stage compared to SCD patients, meaning that the FPN is less segregated at the MCI stage [118]. In line with previous studies that found decreased DMN dynamic FC variability in the AD spectrum, both MCI and SCD patients had reductions in the DMN’s dynamic FC variability compared to NCs. These reductions were mostly concentrated in the posterior DMN for SCD patients, while they were found in the anterior DMN for MCI patients [112]. Verbal fluency is among the cognitive phenotypes that are more severely impaired in MCI patients compared to SCD patients [119]. Regarding this, one study showed that FC between DMN seeds and the supramarginal gyrus was correlated with improved performance in the Controlled Oral Word Association Test for SCD patients [90,120]. Interestingly, the SCD group had higher FC between DMN seeds and the supramarginal gyrus compared to MCI patients, suggesting that disruption in this FC could be linked to weaker verbal fluency in MCI patients. The BNM’s connectivity also shows strong differentiation between EMCI and LMCI. Compared to SCD, EMCI is marked by reduced BNM–superior frontal gyrus connectivity, whereas LMCI shows increased BNM–hippocampal connectivity [106].

Perhaps the most critical aspect of FC analysis in MCI is its ability to distinguish progressive MCI (pMCI), referring to patients who eventually convert to AD, from stable MCI (sMCI), those who remain cognitively stable over time. Regarding this, one study found an increased within-DMN FC for pMCI patients compared to sMCI, showing a potential compensatory mechanism in the DMN to preserve cognitive abilities prior to overt AD [121]. Another pattern of static FC that distinguished pMCI and sMCI was the anterior–temporal network, where its hyperconnectivity was associated with a transition from MCI to AD (indicative of pMCI) [122]. A longitudinal study showed that between-network FCs played a more significant role compared to within-network FCs in distinguishing pMCI and sMCI patients, with the DMN and SN being the most contributing networks to this differentiation [123]. In terms of dynamic FC, reduced DMN variability (switching rate) was observed in pMCI patients, highlighting the importance of this network’s hub-like role (as a flexible switching node) in resilience against AD progression [124]. Together, these alterations suggest that patterns of DMN compensation, anterior–temporal hyperconnectivity, and reduced dynamic flexibility may help identify which individuals with MCI are on a trajectory toward Alzheimer’s disease.

4. Overt Alzheimer’s Disease

With the continued accumulation of Aβ (Figure 1), hyperphosphorylation of tau (Figure 2), and neurodegeneration, the disease progresses to its clinical stage. This stage is accompanied by characteristic alterations in FC that reflect the underlying neuropathology of AD. One prominent example is the clear reduction in the AD patients’ connectome modularity (network segregation), which is associated with reduced cognitive resilience [125,126]. Such a widespread connectome-level impact shows that AD affects a broad set of distributed brain networks, as reflected by reduced system segregation [127].

As in other stages, many studies have worked on the DMN to identify its FC patterns specific to AD patients. For example, there was a reduced FC between the DMN and SN over three years in mild AD patients [64]. Moreover, the FC between the mPFC and PCC regions of the DMN with the hippocampus was lower in aMCI and AD patients compared to NCs, a similar trend as observed in the preclinical stage [128]. Again, there are alterations in FC between the MTL and core DMN areas, which shows that such pattern changes start from preclinical stages and persist into overt AD, and this is associated with cognitive decline [63]. A study looked at the effect of restoring one such FC on AD patients’ cognition, where they increased the FC between the hippocampus and a DMN core hub, the left lateral parietal cortex, using rTMS. Strikingly, this stimulation positively affected cognitive performance in AD patients, providing more insights into the importance of FC between DMN core hubs and the hippocampus [129]. Other studies have also seen high FC breakdown in hippocampus and parahippocampal areas, a disruption in the memory networks that might explain why AD is associated with such memory deficits [60]. One such alteration was observed within MTL regions, where the left anterior hippocampus showed a decreased FC with the left amygdala compared to NCs [130].

Other than the DMN, there have been alterations in the FC patterns of other networks in AD patients compared to NCs. With respect to the FPN, while there was an increased FC in the superior parietal gyrus and the left paracentral lobule regions, the left supramarginal gyrus showed reduced FC [131,132]. The executive control network is another domain where AD-specific alterations in FC have been observed. In particular, while there was a reduction in the left anterior cingulate gyrus FC of this network, its superior and middle frontal gyrus FC increased for AD patients [131,132]. Simultaneously with a reduction in within-network connectivity in the DMN, there was an increase in within-network connectivity for the SN. Specifically, the increased connectivity between the anterior cingulate gyrus and the right insula of the SN was associated with hyperactivity-related symptoms in AD [133].

Looking at dynamic connectivity, similar to the MCI and preclinical stage, the overt stage of the disease is characterized by a decreased variability in dynamic FC of different networks [68], and this was evident within the DMN, somatomotor network (SMN), FPN, and visual network [134]. At the very early stages of clinical AD (mild AD), there was a decreased within-network FC in the dynamic states of connectivity, and it seemed to persist with the disease [135]. Similarly to SCD patients, AD patients also exhibited increased dwell time in the state characterized by reduced FC [136]. Looking at within-DMN FC, one study showed that there is a decreased variability in dynamic FC of the left precuneus [137]. Interestingly, left precuneus FC variance was positively correlated with MMSE scores, demonstrating that the flexibility of this DMN hub between different brain states is required for better cognition [137]. These results suggest that the overall FC patterns at the overt stage of the disease are very similar to those already seen in preclinical and prodromal stages. This means that by the time AD reaches the overt stage, the connectome is already strongly affected by the pathology, and more attention should be directed toward the preclinical and prodromal stages, where earlier changes can be detected and interventions may be more effective. In addition, since DMN and FPN FC account for a large portion of the inter-individual variability seen between AD patients [42], their FC alterations could be potential candidates for personalized biomarkers [138]. Connections of these networks have also appeared among the edges which can explain individual differences in the MMSE scores of AD patients, showing their relevance to cognitive skills [139].

5. Brain Fingerprints in AD

The previous sections detail the general patterns of connectivity changes at different stages of AD. Even though such group-based studies are necessary to obtain an understanding of brain architecture in AD, they do not consider the inter-individual heterogeneity within groups. Thus, taking a brain fingerprint strategy and extracting individual-specific features associated with AD pathology may add value to the current findings by making the biomarkers more personalized. CPM does so by employing a leave-one-out approach to explain individual differences in various behavioral measures [40]. The CPM pipeline involves three main steps: (1) splitting the data so that one subject is left out for testing while the rest are used for training, (2) identifying FCs that significantly correlate with a behavioral measure, and (3) using these significantly correlated features to build a linear regression model that predicts the behavioral outcome. The resulting linear model not only predicts behavior but also provides direct interpretability because the regression coefficients quantify the influence of each FC on the predicted outcome. Repeating this across all subjects produces predicted values, whose correlation with the observed outcomes reflects the model’s performance. One of the main strengths of CPM is that it does not focus on group-based feature differences like many classification methods, preserving inter-individual variability within the groups. Moreover, the edge-level feature weights enable the identification of the most behaviorally relevant networks, offering mechanistic insights into how changes in specific functional pathways contribute to clinical impairment. In this way, the recognized patterns become more personalized, enhancing their value as candidate biomarkers for early detection.

Several studies have employed CPM in populations on the AD spectrum. Stampchia et al. demonstrated that the connectome is unique for individuals at the MCI or overt AD stages, making it feasible to use CPM for such cohorts [138]. In line with this, Prakash et al. developed PATH-fc [140], a CPM-based framework that identifies whole-brain FC signatures associated with the CSF p-tau/Aβ ratio, identifying FCs linked to high and low levels of AD-related pathology across its spectrum (from NCs to overt AD patients). They observed that multiple networks participated in the FCs predictive of the p-tau/Aβ ratio, with the strongest contributions coming from the FPN, DMN, and visual II network.

CPM was also used to characterize amyloid and tau pathology progression in Presenilin1 (PSEN1) E280A carriers [141], a well-known mutation of autosomal dominant AD with almost 100% of carriers eventually developing early onset dementia [142]. In developing this relationship, the temporal cortex and DMN FCs were found to be informative of tau burden in these brain regions. CPM has also been used to predict biomarker progression in preclinical populations without genetic mutations. One study used CPM to predict tau-PET accumulation in different brain regions. Interestingly, the CPM model predicted tau accumulation in DMN hubs (mPFC and PCC) better than regions of initial tau accumulation (MTL), which shows that connectome-based models can better characterize initial amyloid site pathology compared to initial tau sites [52]. While CPM has been widely used to predict behavioral phenotypes, it is traditionally restricted to modeling continuous outcomes. To overcome this limitation, Generalized CPM (GenCPM) has recently been developed as a CPM-based framework capable of handling binary and categorical classification tasks, such as distinguishing disease stages [143]. GenCPM further allows for the inclusion and statistical adjustment of confounding variables (e.g., age, sex, and motion), increasing the robustness and clinical interpretability of the model.

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

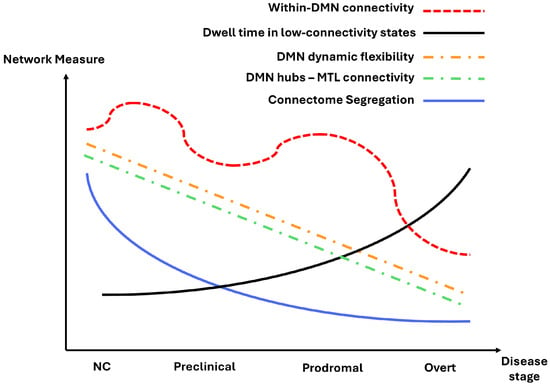

The connectome organization of the brain changes as AD progresses and these changes are linked to cognitive impairments. While some alterations are common across different AD stages, others appear to be stage-specific. Investigating large-scale network organization, particularly the balance between connectome segregation and integration, could be an avenue to pursue for biomarker development. Evidence suggests that AD progression is associated with reduced segregation of functional networks [125,126] (Figure 7). From a network-level perspective, this reflects a shift toward less specialized and more diffusely connected configurations, which may reduce network resilience and increase vulnerability to pathological processes. Thus, characterizing alterations in segregation and integration may offer a sensitive network-based indicator of disease stage and progression in AD [126].

Figure 7.

Schematic illustration of a potential evolution pattern of functional connectivity (FC) measures across the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum. Based on consistent findings from our review, we propose that within-DMN connectivity, DMN dynamic flexibility, DMN hubs–MTL connectivity, and connectome segregation gradually decline from normal cognition (NC) to overt stages, while dwell time in low-connectivity states increases. This figure provides a simplified conceptual representation rather than quantitative data, intended to summarize emerging trends observed across studies.

Among the functional networks, the DMN is particularly informative for AD biomarker research, as it consistently shows both network-level and region-level alterations throughout the course of the disease. Specifically, the DMN tends to display increased within-network connectivity with the onset of Aβ accumulation and the earliest signs of cognitive decline. However, as tau pathology emerges and the disease progresses to later stages, this hyperconnectivity gives way to widespread hypoconnectivity, reflecting a breakdown of network integrity and efficiency (Figure 7). In addition, there was a consistent reduced variability and flexibility observed in the dynamic FC pattern of this network, particularly in its core hubs (Figure 7). Together, alterations in both static and dynamic FC properties of the DMN highlight its potential as a sensitive marker for capturing the evolving functional architecture of the brain across different stages of AD.

A reduction in FC between MTL regions and hubs of the DMN is another consistent finding that may serve as a signature of AD progression (Figure 7). In particular, hippocampus FC with the PCC, precuneus, and mPFC has been shown to predict memory retrieval performance [144,145,146]. These alterations in FC patterns start from early stages and persist until overt AD. Interestingly, mind–body exercises have improved memory performance in older adults and are associated with an increase in FC between the hippocampus and mPFC [147]. These findings suggest that the core DMN hub’s FC with the hippocampus could provide valuable information about the cognitive status of an individual. The early emergence of Aβ and tau, accompanied by abnormally reduced MTL–DMN FC, may therefore indicate the risk of AD progression, highlighting this period as a critical window for applying training interventions and lifestyle practices to help retain or retrieve normal FC patterns and cognition.

Another well-established observation is reduced dynamic FC flexibility across the disease spectrum (Figure 7). Previous studies have shown that dynamic variability is essential for proper cognitive processing and loss of dynamic variability has been observed in other neurological disorders [148,149]. Moreover, there is a tendency for AD patients to dwell in states characterized by lowered connectivity, which is in correspondence with the general tendency of reduced FC in patients on the AD spectrum (Figure 7). The alterations to dynamic FC begin at early stages, and continue to evolve as the disease advances, reflecting progressive disruptions in network flexibility and temporal coordination. Together, these findings point to dynamic FC rigidity as a potential marker of AD progression, warranting further investigation into its role in early detection and disease monitoring.

Taken together, the patterns in Figure 7 show a clear network trajectory across the AD spectrum. Segregation, the DMN’s dynamic flexibility, and DMN hubs–MTL connectivity all steadily decline as the disease advances, indicating reduced specialization, weaker memory-related pathways, and less adaptive network behavior. In contrast, dwell time in low-connectivity states increases, reflecting more time spent in globally weakened configurations. Within-DMN connectivity follows a nonlinear path with early increases and later decreases. Together, these patterns offer a useful foundation for developing FC-based biomarkers of AD progression.

Other than the DMN, FC between other regions and networks also shows promise in providing information about AD progression. Networks such as the DAN, SN, and FPN have alterations in their within- and between-network FC patterns across the AD spectrum. Evidence suggests that the SN and FPN exhibit stage-specific hyperconnectivity, consistent with their function as multimodal hubs linking widespread regions and supporting global information processing [150]. Understanding these network-level alterations could be valuable, as they may offer additional markers to track disease progression and shed light on compensatory mechanisms in AD.

Most existing studies describe connectome alterations through group-level comparisons between cognitively normal individuals and those along the AD spectrum. Integrating these group-derived patterns with individual-specific approaches such as CPM could provide deeper insight into how AD’s pathology shapes personalized FC profiles. For instance, future studies could apply CPM to AD-related FCs, such as MTL–DMN connections and the DMN’s dynamic flexibility and examine whether they account for individual variability in Aβ and tau burden or cognitive decline. Researchers can utilize open-source datasets such as the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) [151], Open Access Series of Imaging Studies (OASIS) [152], and PResymptomatic EValuation of Experimental or Novel Treatments for Alzheimer’s Disease (PREVENT-AD) [153] to perform AD-related FC analyses and apply CPM to link individual FC variability with pathology and cognition for developing personalized biomarkers.

Despite extensive research on FC alterations in AD, several limitations hinder translation into reliable stage-specific diagnostic or progression biomarkers. As detailed here, consistent alterations in FC appear across multiple disease stages, making it difficult to distinguish the disease stages based on FC alone and highlighting the need for multimodal biomarkers. For example, regional uptake of tau and amyloid PET ligands in patients on the AD spectrum shows stage-specific binding patterns. Thus, composite measures incorporating FC changes, PET measures, measures from structural MRI, and cognitive measures may improve AD staging and fully capture neurodegeneration. Such composite measures could also be integrated with personalized approaches, such as CPM, to characterize disease progression at the individual level, or be combined with machine learning methods to better estimate a person’s position along the AD spectrum.

Biological factors may also hinder clinical translation. For example, cerebral vascular changes [154], neuroinflammation [155], and structural atrophy may alter the BOLD signal and confound interpretations of FC disruption [156]. Methodological differences (preprocessing pipeline, parcellation, and acquisition parameters) are another factor that can decrease reproducibility across imaging studies [157,158,159]. For instance, the choice of parcellation scheme (e.g., anatomical vs. functional atlas, or number of parcels) affects network resolution and can bias which connections appear most relevant. Thresholding and binarization decisions alter network topology—stringent thresholds may remove weaker yet biologically meaningful connections, whereas lenient ones can introduce spurious links. Similarly, the use of weighted versus unweighted graphs changes how measures like degree and efficiency are computed, while assumptions about directionality (e.g., correlation or effective connectivity models) influence interpretations of information flow. Finally, preprocessing steps (global signal regression, motion correction, and temporal filtering) can modulate apparent network strength and signs. The adoption of standardized acquisition and preprocessing pipelines, harmonization frameworks, and careful control of biological and technical confounds is essential to improve reproducibility and enable more meaningful comparisons of FC alterations across studies and disease stages. With further validation and standardization, these FC-based measures could eventually be incorporated into clinical practice to improve early detection and personalized management of AD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G., J.L. and X.H.; investigation, A.G., Y.Z., M.A. and Y.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G., Y.Z., M.A. and Y.R.; writing—review and editing, A.G., Y.Z., J.L. and X.H.; visualization, A.G.; supervision, J.L. and X.H.; project administration, A.G., J.L. and X.H.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by R01-AG072607 grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging. Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the ADNI (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). The ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie; Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research provides funds to support the ADNI’s clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. The ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Two figures were created from data collected by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| aMCI | amnestic mild cognitive impairment |

| Aβ | amyloid-beta |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| BNM | basal nucleus of Meynert |

| BOLD | blood oxygen level-dependent |

| CPM | connectome-based predictive modeling |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| DAN | dorsal attention network |

| DMN | default mode network |

| EEG | electroencephalography |

| EMCI | Early stage mild cognitive impairment |

| FC | functional connectivity |

| FPN | frontoparietal network |

| ICA | independent component analysis |

| LMCI | late-stage mild cognitive impairment |

| MEG | magnetoencephalography |

| mPFC | medial prefrontal cortex |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| MCI | mild cognitive impairment |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| MTL | medial temporal lobe |

| NCs | normal controls |

| pMCI | progressive mild cognitive impairment |

| PCC | posterior cingulate cortex |

| PET | positron emission tomography |

| PiB | Pittsburgh Compound B |

| p-tau | phosphorylated tau |

| rTMS | repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation |

| sMCI | stable mild cognitive impairment |

| SCD | subjective cognitive decline |

| SN | salience network |

| t-tau | total tau |

| TPJ | temporoparietal junction |

References

- Zhang, M.; Chen, H.; Huang, W.; Guo, T.; Ma, G.; Han, Y.; Shu, N. Relationship between topological efficiency of white matter structural connectome and plasma biomarkers across the Alzheimer’s disease continuum. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2024, 45, e26566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, T.G.; Iacob, L.; Vasilache, C.; Schreiner, O.D. Therapeutic Modalities Targeting Tau Protein in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Dement. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2025, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, K.B.; Weuve, J.; Barnes, L.L.; McAninch, E.A.; Wilson, R.S.; Evans, D.A. Population estimate of people with clinical Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in the United States (2020–2060). Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 17, 1966–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, J.; Langerman, H. Alzheimer’s disease—Why we need early diagnosis. Degener. Neurol. Neuro-Muscular Dis. 2019, 24, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Sporns, O.; Saykin, A.J. The human connectome in Alzheimer disease—Relationship to biomarkers and genetics. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 545–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milanifard, M.; Ramezani, M. Clinical and neurological problems and clinical tests in Alzheimer’s patients specializing in Alzheimer’s disease. Eurasian J. Chem. Med. Pet. Res. 2025, 4, 152–163. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Shan, P.-Y.; Jiang, W.-J.; Sheng, C.; Ma, L. Subjective cognitive decline: Preclinical manifestation of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 40, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcockson, T.D.W.; Begde, A.; Hogervorst, E. Subjective Cognitive Decline and Antisaccade Latency: Exploring Early Markers of Dementia Risk. J. Dement. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2025, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA research framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perron, J.; Scramstad, C.; Ko, J.H. Brain metabolic imaging-based model identifies cognitive stability in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, J.; Bennett, I.J.; Hu, X.P.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Examining iron-related off-target binding effects of 18F-AV1451 PET in the cortex of Aβ+ individuals. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2024, 60, 3614–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camus, V.; Payoux, P.; Barré, L.; Desgranges, B.; Voisin, T.; Tauber, C.; La Joie, R.; Tafani, M.; Hommet, C.; Chételat, G.; et al. Using PET with 18F-AV-45 (florbetapir) to quantify brain amyloid load in a clinical environment. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2012, 39, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klunk, W.E.; Engler, H.; Nordberg, A.; Wang, Y.; Blomqvist, G.; Holt, D.P.; Bergström, M.; Savitcheva, I.; Huang, G.; Estrada, S.; et al. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann. Neurol. 2004, 55, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheline, Y.I.; Raichle, M.E. Resting state functional connectivity in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 74, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojjati, S.H.; Butler, T.A.; de Leon, M.; Gupta, A.; Nayak, S.; Luchsinger, J.A.; Razlighi, Q.R.; Chiang, G.C. Inter-network functional connectivity increases by beta-amyloid and may facilitate the early stage of tau accumulation. Neurobiol. Aging 2025, 148, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciaglia, R.; Shekari, M.; Salvadó, G.; Milà-Alomà, M.; Falcon, C.; Sánchez-Benavides, G.; Minguillón, C.; Fauria, K.; Grau-Rivera, O.; Molinuevo, J.L.; et al. The CSF p-tau/β-amyloid 42 ratio correlates with brain structure and fibrillary β-amyloid deposition in cognitively unimpaired individuals at the earliest stages of pre-clinical Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Commun. 2025, 7, fcae451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnsten, A.F.; Del Tredici, K.; Barthélemy, N.R.; Gabitto, M.; van Dyck, C.H.; Lein, E.; Braak, H.; Datta, D. An integrated view of the relationships between amyloid, tau, and inflammatory pathophysiology in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2025, 21, e70404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzmeier, N.; Dewenter, A.; Frontzkowski, L.; Dichgans, M.; Rubinski, A.; Neitzel, J.; Smith, R.; Strandberg, O.; Ossenkoppele, R.; Buerger, K.; et al. Patient-centered connectivity-based prediction of tau pathology spread in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabd1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, R.; McQuillan, L.; Wang, K.K.; Robertson, C.S.; Chang, B.; Yang, Z.; Xu, H.; Williamson, J.B.; Wagner, A.K. Temporal Profiles of P-Tau, T-Tau, and P-Tau:Tau Ratios in Cerebrospinal Fluid and Blood from Moderate-Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Patients and Relationship to 6–12 Month Global Outcomes. J. Neurotrauma 2024, 41, 369–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossenkoppele, R.; Schonhaut, D.R.; Schöll, M.; Lockhart, S.N.; Ayakta, N.; Baker, S.L.; O’neil, J.P.; Janabi, M.; Lazaris, A.; Cantwell, A.; et al. Tau PET patterns mirror clinical and neuroanatomical variability in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2016, 139, 1551–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.A.; Schultz, A.; Betensky, R.A.; Becker, J.A.; Sepulcre, J.; Rentz, D.; Mormino, E.; Chhatwal, J.; Amariglio, R.; Papp, K.; et al. Tau positron emission tomographic imaging in aging and early Alzheimer disease. Ann. Neurol. 2016, 79, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passamonti, L.; Vázquez, R.P.; Hong, Y.; Allinson, K.S.; Williamson, D.; Borchert, R.J.; Sami, S.; Cope, T.; Bevan-Jones, W.; Jones, S.; et al. 18F-AV-1451 positron emission tomography in Alzheimer’s disease and progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain 2017, 140, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, M.R.; Gbadeyan, O.; Andridge, R.; Schroeder, M.W.; Pugh, E.A.; Scharre, D.W.; Prakash, R.S. p-Tau/Aβ42 ratio associates with cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, and cognitively unimpaired older adults. Neuropsychology 2025, 39, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jessen, F.; Amariglio, R.E.; Buckley, R.F.; van der Flier, W.M.; Han, Y.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Rabin, L.; Rentz, D.M.; Rodriguez-Gomez, O.; Saykin, A.J.; et al. The characterisation of subjective cognitive decline. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Beaumont, H.; Ferguson, D.; Yadegarfar, M.; Stubbs, B. Risk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older people with subjective memory complaints: Meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2014, 130, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marafioti, G.; Culicetto, L.; Latella, D.; Marra, A.; Quartarone, A.; Buono, V.L. Neural correlates of subjective cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of structural and functional brain changes for early diagnosis and intervention. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 17, 1549134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jeong, M.; Stiles, W.R.; Choi, H.S. Neuroimaging Modalities in Alzheimer’s Disease: Diagnosis and Clinical Features. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, L.; Häner, M.; Rössler, R.; Krumm, S. Comparison of Physical Activity Patterns Between Individuals with Early-Stage Alzheimer’s Disease and Cognitively Healthy Adults. J. Dement. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2025, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Sheng, X.; Luo, C.; Qin, R.; Ye, Q.; Zhao, H.; Xu, Y.; Bai, F.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. The compensatory phenomenon of the functional connectome related to pathological biomarkers in individuals with subjective cognitive decline. Transl. Neurodegener. 2020, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, R.A.; Aisen, P.S.; Beckett, L.A.; Bennett, D.A.; Craft, S.; Fagan, A.M.; Iwatsubo, T.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; Kaye, J.; Montine, T.J.; et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomou, V.P.; Georgiadis, K.; Lazarou, I.; Nikolopoulos, S.; Kompatsiaris, I.; PREDICTOM Consortium. Exploring Functional Brain Networks in Alzheimer’s Disease Using Resting State EEG Signals. J. Dement. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2025, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, S.E.; Hyman, B.T.; Betensky, R.A.; Dodge, H.H. Pathways to personalized medicine—Embracing heterogeneity for progress in clinical therapeutics research in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 7384–7394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R.; Winter, W.R.; Ding, J.; Nunez, P.L. EEG and MEG coherence: Measures of functional connectivity at distinct spatial scales of neocortical dynamics. J. Neurosci. Methods 2007, 166, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckner, R.L.; Andrews-Hanna, J.R.; Schacter, D.L. The brain’s default network: Anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1124, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeley, W.W.; Menon, V.; Schatzberg, A.F.; Keller, J.; Glover, G.H.; Kenna, H.; Reiss, A.L.; Greicius, M.D. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 2349–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.W.; Reynolds, J.R.; Power, J.D.; Repovs, G.; Anticevic, A.; Braver, T.S. Multi-task connectivity reveals flexible hubs for adaptive task control. Nat. Neurosci. 2013, 16, 1348–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, C.F.; DeLuca, M.; Devlin, J.T.; Smith, S.M. Investigations into resting-state connectivity using independent component analysis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2005, 360, 1001–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas Yeo, B.T.; Krienen, F.M.; Sepulcre, J.; Sabuncu, M.R.; Lashkari, D.; Hollinshead, M.; Roffman, J.L.; Smoller, J.W.; Zöllei, L.; Polimeni, J.R.; et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 2011, 106, 1125–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramduny, J.; Kelly, C. Connectome-based fingerprinting: Reproducibility, precision, and behavioral prediction. Neuropsychopharmacology 2025, 50, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Finn, E.S.; Scheinost, D.; Rosenberg, M.D.; Chun, M.M.; Papademetris, X.; Constable, R.T. Using connectome-based predictive modeling to predict individual behavior from brain connectivity. Nat. Protoc. 2017, 12, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, A.; Abouzaki, M.; Romero, Y.; Sun, A.; Seitz, A.; Langley, J.; Bennett, I.J.; Hu, X. Connectome-based predictive modelling predicts frailty levels in older adults. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, E.S.; Shen, X.; Scheinost, D.; Rosenberg, M.D.; Huang, J.; Chun, M.M.; Papademetris, X.; Constable, R.T. Functional connectome fingerprinting: Identifying individuals using patterns of brain connectivity. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 1664–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, M.L.; Ye, J.; Powers, A.R.; Dvornek, N.C.; Scheinost, D. Connectome-based predictive modeling of early and chronic psychosis symptoms. Neuropsychopharmacology 2025, 50, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treves, I.N.; Kucyi, A.; Park, M.; Kral, T.R.A.; Goldberg, S.B.; Davidson, R.J.; Rosenkranz, M.; Whitfield-Gabrieli, S.; Gabrieli, J.D.E. Connectome-Based Predictive Modeling of Trait Mindfulness. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2025, 46, e70123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.N.; Chappel-Farley, M.G.; Yaros, J.L.; Taylor, L.; Harris, A.L.; Mikhail, A.; McMillan, L.; Keator, D.B.; Yassa, M.A. Functional network structure supports resilience to memory deficits in cognitively normal older adults with amyloid-β pathology. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.; Wang, J.; Xue, Y.; Jiang, J.; Cao, M.; Li, S.; Chen, X.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Characterizing structure-function coupling in subjective memory complaints of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2025, 107, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stam, C.J.; van Nifterick, A.M.; de Haan, W.; Gouw, A.A. Network hyperexcitability in early Alzheimer’s disease: Is functional connectivity a potential biomarker? Brain Topogr. 2023, 36, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzmeier, N.; Rubinski, A.; Neitzel, J.; Kim, Y.; Damm, A.; Na, D.L.; Kim, H.J.; Lyoo, C.H.; Cho, H.; Finsterwalder, S.; et al. Functional connectivity associated with tau levels in ageing, Alzheimer’s, and small vessel disease. Brain 2019, 142, 1093–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Yao, L.; He, N.; Tang, Y.; Chen, L.; Long, F.; Chen, Y.; Kemp, G.J.; Lui, S.; et al. Shared and differing functional connectivity abnormalities of the default mode network in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Cereb. Cortex 2024, 34, bhae094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, C.D.; Pinto, C.B.; Mukli, P.; Gulej, R.; Velez, F.S.; Detwiler, S.; Olay, L.; Hoffmeister, J.R.; Szarvas, Z.; Muranyi, M.; et al. Neurovascular coupling, functional connectivity, and cerebrovascular endothelial extracellular vesicles as biomarkers of mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 5590–5606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer-Cassiano, S.N.; Wagner, F.; Evangelista, L.; Rauchmann, B.-S.; Dehsarvi, A.; Steward, A.; Dewenter, A.; Biel, D.; Zhu, Z.; Pescoller, J.; et al. Amyloid-associated hyperconnectivity drives tau spread across connected brain regions in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2025, 17, eadp2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuwarda, H.; Trainer, A.; Horien, C.; Shen, X.; Moret, S.; Ju, S.; Constable, R.T.; Fredericks, C. Whole-brain functional connectivity predicts regional tau PET in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Commun. 2025, 7, fcaf274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffari, A.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Langley, J.; Hu, X. Dynamic fingerprinting of the human functional connectome. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieder, M.; Wang, D.J.J.; Dierks, T.; Wahlund, L.-O.; Jann, K. Default mode network complexity and cognitive decline in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, P.R.; Ances, B.M.; Gordon, B.A.; Benzinger, T.L.; Fagan, A.M.; Morris, J.C.; Balota, D.A. Evaluating resting-state BOLD variability in relation to biomarkers of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2020, 96, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, A.P.; Chhatwal, J.P.; Hedden, T.; Mormino, E.C.; Hanseeuw, B.J.; Sepulcre, J.; Huijbers, W.; LaPoint, M.; Buckley, R.F.; Johnson, K.A.; et al. Phases of hyperconnectivity and hypoconnectivity in the default mode and salience networks track with amyloid and tau in clinically normal individuals. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 4323–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.A.; Sperling, R.A.; Sepulcre, J. Functional connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease: Measurement and meaning. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 74, 318–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, L.; Adams, J.N.; Molloy, E.N.; Vockert, N.; Tremblay-Mercier, J.; Remz, J.; Binette, A.P.; Villeneuve, S.; Maass, A.; PREVENT-AD Research Group. Differential effects of aging, Alzheimer’s pathology, and APOE4 on longitudinal functional connectivity and episodic memory in older adults. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2025, 17, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingala, S.; Tomassen, J.; Collij, L.E.; Prent, N.; van ‘t Ent, D.; Kate, M.T.; Konijnenberg, E.; Yaqub, M.; Scheltens, P.; de Geus, E.J.C.; et al. Amyloid-driven disruption of default mode network connectivity in cognitively healthy individuals. Brain Commun. 2021, 3, fcab201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Liu, H.; Hu, H.; He, H.; Zhao, X. Primary disruption of the memory-related subsystems of the default mode network in Alzheimer’s disease: Resting-state functional connectivity MRI study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirsoy, I. Tau Pathology in the Medial Temporal Lobe and Neocortex: Implications for Cognitive Unimpaired in Cognitively Unimpaired Older Adults. Balk. Med. J. 2025, 42, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboodvand, N.; Bäckman, L.; Nyberg, L.; Salami, A. The retrosplenial cortex: A memory gateway between the cortical default mode network and the medial temporal lobe. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2018, 39, 2020–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berron, D.; van Westen, D.; Ossenkoppele, R.; Strandberg, O.; Hansson, O. Medial temporal lobe connectivity and its associations with cognition in early Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2020, 143, 1233–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, A.P.; Buckley, R.F.; Hampton, O.L.; Scott, M.R.; Properzi, M.J.; Peña-Gómez, C.; Pruzin, J.J.; Yang, H.-S.; Johnson, A.K.; Sperling, A.R.; et al. Longitudinal degradation of the default/salience network axis in symptomatic individuals with elevated amyloid burden. NeuroImage Clin. 2020, 26, 102052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fountain-Zaragoza, S.; Liu, H.; Benitez, A. Functional network alterations associated with cognition in pre-clinical Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Connect. 2023, 13, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, R.; Klinger, H.M.; Shirzadi, Z.; Coughlan, G.T.; Seto, M.; Properzi, M.J.; Townsend, D.L.; Yuan, Z.; Scanlon, C.; Jutten, R.J.; et al. Left frontoparietal control network connectivity moderates the effect of amyloid on cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: The A4 study. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2024, 11, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, F.; Liu, X.; Fan, D.; He, C.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, C.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; Alzheimer’s Disease Metabolomics Consortium. Dynamic functional network connectivity and its association with lipid metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e70029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canal-Garcia, A.; Veréb, D.; Mijalkov, M.; Westman, E.; Volpe, G.; Pereira, J.B.; Initiative, F.T.A.D.N. Dynamic multilayer functional connectivity detects preclinical and clinical Alzheimer’s disease. Cereb. Cortex 2024, 34, bhad542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzini, L.; Ingala, S.; Collij, E.L.; Wottschel, V.; Haller, S.; Blennow, K.; Frisoni, G.; Chételat, G.; Payoux, P.; Lage-Martinez, P.; et al. Eigenvector centrality dynamics are related to Alzheimer’s disease pathological changes in non-demented individuals. Brain Commun. 2023, 5, fcad088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossenkoppele, R.; Hansson, O. Towards clinical application of tau PET tracers for diagnosing dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 17, 1998–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berron, D.; Vogel, J.W.; Insel, P.S.; Pereira, J.B.; Xie, L.; Wisse, L.E.M.; Yushkevich, A.P.; Palmqvist, S.; Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; Stomrud, E.; et al. Early stages of tau pathology and its associations with functional connectivity, atrophy and memory. Brain 2021, 144, 2771–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wales, R.M.; Leung, H.-C. The effects of amyloid and tau on functional network connectivity in older populations. Brain Connect. 2021, 11, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintini, I.; Graff-Radford, J.; Jones, D.T.; Botha, H.; Martin, P.R.; Machulda, M.M.; Schwarz, C.G.; Senjem, M.L.; Gunter, J.L.; Jack, C.R.; et al. Tau and amyloid relationships with resting-state functional connectivity in atypical Alzheimer’s disease. Cereb. Cortex 2021, 31, 1693–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, T.E.; Rittman, T.; Borchert, R.J.; Jones, P.S.; Vatansever, D.; Allinson, K.; Passamonti, L.; Vazquez Rodriguez, P.; Bevan-Jones, W.R.; O’Brien, J.T.; et al. Tau burden and the functional connectome in Alzheimer’s disease and progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain 2018, 141, 550–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisch, J.K.; Roe, C.M.; Babulal, G.M.; Schindler, S.E.; Fagan, A.M.; Benzinger, T.L.; Morris, J.C.; Ances, B.M. Resting state functional connectivity signature differentiates cognitively normal from individuals who convert to symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 74, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán-Vélez, E.; Diez, I.; Schoemaker, D.; Pardilla-Delgado, E.; Vila-Castelar, C.; Fox-Fuller, J.T.; Baena, A.; Sperling, R.A.; Johnson, K.A.; Lopera, F.; et al. Amyloid-β and tau pathologies relate to distinctive brain dysconnectomics in preclinical autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2113641119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, M.; Azargoonjahromi, A.; Nasiri, H.; Yaghoobi, A.; Sadeghi, M.; Chavoshi, S.S.; Baghaeikia, S.; Mahzari, N.; Valipour, A.; Oskouei, R.R.; et al. Altered brain connectivity in mild cognitive impairment is linked to elevated tau and phosphorylated tau, but not to GAP-43 and amyloid-β measurements: A resting-state fMRI study. Mol. Brain 2024, 17, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, T.M.; Maass, A.; Adams, J.N.; Du, R.; Baker, S.L.; Jagust, W.J. Tau deposition is associated with functional isolation of the hippocampus in aging. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatansever, D.; Menon, D.; Stamatakis, E. Default mode contributions to automated information processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 12821–12826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottoy, J.; Kang, M.S.; Tan, J.X.M.; Boone, L.; de Wael, R.V.; Park, B.-Y.; Bezgin, G.; Lussier, F.Z.; Pascoal, T.A.; Rahmouni, N.; et al. Tau follows principal axes of functional and structural brain organization in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbers, W.; Schultz, A.P.; Papp, K.V.; LaPoint, M.R.; Hanseeuw, B.; Chhatwal, J.P.; Hedden, T.; Johnson, K.A.; Sperling, R.A. Tau accumulation in clinically normal older adults is associated with hippocampal hyperactivity. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepulcre, J.; Sabuncu, M.R.; Li, Q.; El Fakhri, G.; Sperling, R.; Johnson, K.A. Tau and amyloid β proteins distinctively associate to functional network changes in the aging brain. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2017, 13, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budak, M.; Fausto, B.A.; Osiecka, Z.; Sheikh, M.; Perna, R.; Ashton, N.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Fitzgerald-Bocarsly, P.; Gluck, M.A. Elevated plasma p-tau231 is associated with reduced generalization and medial temporal lobe dynamic network flexibility among healthy older African Americans. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2024, 16, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, J.; Mohanty, R.; Westman, E.; Middleton, L. Lower Network Functional Connectivity Is Associated With Higher Regional Tau Burden Among Those At-Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease but Cognitively Unimpaired: Specific Patterns Based on Amyloid Status. Res. Sq. 2025, rs.3.rs-5820051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]