Abstract

Background: Postoperative delirium (POD) is commonly observed after surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) and could have serious consequences. Its prevalence varied among prior published series. With increasing patient age, a worsening of this problem can be expected. Methods: The association between POD and other adverse events, as well as its effect on 30-day mortality, long-term survival, and later dementia development, was investigated in 1500 consecutive patients (1527 operations) undergoing SAVR with a biological prosthesis, with or without concomitant procedures. An observational retrospective file analysis was performed, using chi-square, Student’s t-test, logistic regression, and Kaplan–Meyer analyses. Results: POD was recorded in 183/1527 (12.0%) of the patient files. Its independent predictors were need for reintervention, age over 80 years, male gender, peripheral artery disease, smoking, need for non-elective SAVR, atrial fibrillation, and a prior TIA. POD was associated with all other postoperative adverse events and increased need for resources. Thirty-day mortality was almost four times higher with POD: 35/182 (19.1%) vs. 59/1345 (4.4%), p < 0.001. Five-year survival was significantly reduced in patients with POD: 79.8 ± 1.2% versus 59.5 ± 4.3%, p < 0.001. The mean time to occurrence of dementia was 89 (84–95) months in patients without POD versus 60 (50–71) months in patients with POD. Five-year freedom from dementia was 69.1 ± 2.9% versus 44.4 ± 6.8%, p < 0.001. Conclusions: POD is associated with short-term complication rates, increased need for resources and hospital mortality, a reduced long-term survival rate, and an increased risk of dementia development. The limitations of this investigation include its retrospective and observational nature; in addition, it did not detect preoperative mild cognitive impairment.

1. Introduction

Surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) is one of the main treatment modalities for symptomatic aortic valve disease, with good results in patients aged between 75 and 80 years [1] and acceptable outcomes in octogenarian patients aged between 80 and 85 years [2]. Postoperative delirium (POD) is one of the most common neurologic complications after cardiac surgery. POD is an acute syndrome characterized by fluctuating changes in attention, disturbing awareness, and cognition [3]. POD can be accompanied by agitation or, conversely, diminished motor activity [4,5]. This condition is more common in elderly patients [6,7] and after combined cardiac procedures, such as valve surgery combined with a CABG [7]. The observed increase in octogenarian referrals over time, as well as the high need for a concomitant CABG, illustrates their relevance in this respect [8]. Prior series showed a varying prevalence of POD after cardiac surgery, ranging from below 10% [9,10,11] or just above 10% [12,13] to over 50% [14,15,16,17]. In series with a lower POD prevalence, usually no specific measurement instrument was used, while in series with a higher POD prevalence, an instrument was used, such as the Confusion Assessment Method (3D-CAM and CAM-ICU) [14,16] or the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) [17]. This indicates that the mode of detecting POD affects its observed incidence considerably. Remarkably, for the ICDSC scale, a comparatively lower POD prevalence of 17.4% was observed in one series [3]. The same observation was made for the delirium observation screening (DOS), with prevalences between 6% and 17% [6,7]. These observations indicate that there may be real variation in the prevalence of POD, but its diagnosis is not straightforward. POD is an important event since it is associated with increased short-term mortality [7], decreased long-term survival [18,19], and increased dementia development [18]. An estimated 5% of the world’s elderly population is affected by dementia. This number could rise because of the aging of the population [20]. POD could affect the long-term development of dementia. The current research aims to identify the main predictors of delirium after SAVR during a hospital stay. It also aims to determine the main consequences of delirium on long-term survival and dementia development during a long-term follow-up.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective file study of 1500 consecutive patients who underwent SAVR (1527 procedures) in a general hospital from 2006 to 2017. It followed the STROBE checklist for case–control studies, with a follow-up of 9465 patient-years. The preoperative and operative characteristics, as well as the postoperative outcomes, were compared between patients with and without POD and are listed within the tables. Significant coronary, peripheral, carotid, and left main stem artery diseases were defined as a stenosis of at least 50% on angiography or as a need for an invasive procedure. The type and severity of the aortic valve disease, as well as the left ventricular function, were assessed with echocardiography. Atrial fibrillation and conduction defects were diagnosed on ECG. Diabetes was defined as a fasting plasma glucose of >125 mg% or treatment with diet or antidiabetic medication. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) below 60 mL/min. “Non-elective” was defined as the need for SAVR at the index hospital stay, during which the diagnosis of aortic valve disease was established. “Emergent” was defined as the need for SAVR on the same day of admission. Obesity was defined as body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m2. Arterial hypertension was defined as repeated arterial blood pressure > 140/90 mmHg or being under chronic antihypertensive treatment. Acute myocardial infarction was documented on ECG and biochemically. Endocarditis was diagnosed according to the Duke criteria. CVA and TIA were documented before sudden neurologic deficits of >24 h resp. < 30 min. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was FEV1 < 70% of the predicted value. The need for associated procedures (CABG, mitral valve repair, procedure on the ascending aorta, and other procedures), aortic cross-clamp (ACC), and cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) time were recorded in surgical reports.

The following postoperative adverse events were recorded within 30 days: endocarditis (according to Duke criteria); thromboembolic events, such as sudden neurologic deficits or ischemia of other organs and limbs; and bleeding, defined as any abnormal event (hematuria, soft tissue hematomas, cerebral hemorrhage, and also abnormal blood loss through drains needing treatment with clotting factors or reintervention). New or progressing prior conduction defects, as well as new or recurring atrial fibrillation, were recorded on ECG. Acute kidney injury was defined as a reduced eGFR of at least 25%. Pulmonary complications were defined as clinical or radiological signs of atelectasis and pneumonia. Congestive heart failure (LCOS) was defined as an increased need for inotropic medication, pulmonary or peripheral edema, low blood pressure, and need for mechanical circulatory support. An increase in need for resources was defined as mechanical ventilation of more than 8 h, need for renal replacement therapy, need for more than 4 units of packed cells, reintervention for bleeding or tamponade, and need for postoperative permanent pacemaker implant. The following parameters were recorded during the ICU stay: lowest arterial oxygen pressure after extubation, highest plasma glucose, lowest hematocrit, an ICU stay of more than one day, and a postoperative stay of more than eight days. The outcomes were 30-day delirium, recorded by doctors and nursing staff, dementia development during long-term follow-up, and survival. POD diagnosis was based on nurse and doctor observations of disorientation in space, time, and towards people, with consequent disorganized thinking and, possibly, an altered level of consciousness. A dedicated measurement instrument, such as the CAM-ICU, was not a part of the postoperative routine. Dementia diagnoses were extracted from the patient files, including a neurologic report, repeated values of MMSE below 23/30 under non-acute conditions, and the use of donepezil prescribed by a neurologist. The statistical analysis included a univariate chi-square for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables to determine the association between POD and preoperative and operative variables, as well as postoperative adverse events. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify POD predictors, considering significant preoperative and operative factors from the univariate analysis. A Kaplan–Meier analysis with the log-rank test was used to assess the effect of POD on dementia development and survival. A Cox proportional hazard analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of survival. This study was approved by the ZNA Ethical Committee under the protocol N° 2656.

3. Results

3.1. Preoperative and Operative Variables

POD was recorded in 183/1527 (12.0%) of the patients. It occurred mostly on the first postoperative day and lasted 24–48 h. Table 1 shows the distribution of POD for the presence or absence of the factor under investigation. The main factors associated with POD were age, male gender, and several cardiovascular, cerebral, and other non-cardiac comorbid conditions, such as renal and pulmonary dysfunction. The mean age of patients with delirium was three years higher (75.4 ± 7.0 vs. 78.2 ± 6.2 years, p < 0.001). They also had a lower ejection fraction (61.2 ± 15.5% vs. 55.8 ± 17.0%, p = 0.002) and higher preoperative plasma creatinine (1.08 ± 0.59 mg% vs. 1.18 ± 0.56 mg%; p = 0.023), but no significant difference in aortic valve disease severity in terms of transvalvular gradients. The prevalence of POD also increased over time. A concomitant CABG was also associated with an increase in POD, while the use of partial sternotomy seemed to lower the rate of POD. CPB was about 15 min longer in patients with POD (119.7 ± 42.6 min vs. 133.6 ± 45.6 min, p < 0.001), while ACC was about 10 min longer (68.2 ± 23.0 min vs. 77.1 ± 33.4 min, p = 0.002).

Table 1.

Association between POD and preoperative and operative factors.

3.2. Early Postoperative Adverse Events and Need for Resources

Table 2 shows that POD is associated with virtually all adverse postoperative events (except for endocarditis, because of its low numbers) and with an increase in the need for resources. Ventilation time (12.2 ± 31.9 h vs. 46.2 ± 115.8 h, p <0.001), ICU stay (2.5 ± 5.4 days vs. 8.7 ± 14.3 days, p < 0.001), and postoperative hospital stay (9.6 ± 7.5 days vs. 16.3 ± 14.5 days, p < 0.001) were significantly longer for patients with POD. The use of packed cells (2.5 ± 3.3 vs. 4.2 ± 4.6 units, p < 0.001) was also significantly higher. Patients with POD also had a lower nadir of arterial partial oxygen pressure (86.0 ± 22.9 mm Hg vs. 77.8 ± 20.9 mm Hg <0.001) and hematocrit (25.0 ± 3.4% vs. 24.0 ± 3.7%, p = 0.001) and peak plasma glucose (170.6 ± 46.9 mg% vs. 183.5 ± 50.3 mg%, p = 0.001) and plasma creatinine (1.35 ± 0.90 mg% vs. 1.93 ± 1.27 mg%, p < 0.001). Mortality was over four times higher in patients who suffered from POD: 35/182 (19.1%) vs. 59/1345 (4.4%), p < 0.001.

Table 2.

Association with postoperative adverse events.

3.3. Independent Predictors of POD

Table 3 shows the independent predictors of POD. All predictors were of a preoperative nature, except the need for reintervention, which required a second surgical and anesthesia session. This was the most important predictor, with an odds ratio of over 5, followed by an age of over 80 years, with an odds ratio of over 2. The other factors, although significant, were clinically less prominent.

Table 3.

Identification of POD predictors using logistic regression.

3.4. Long-Term Effects of Postoperative Delirium

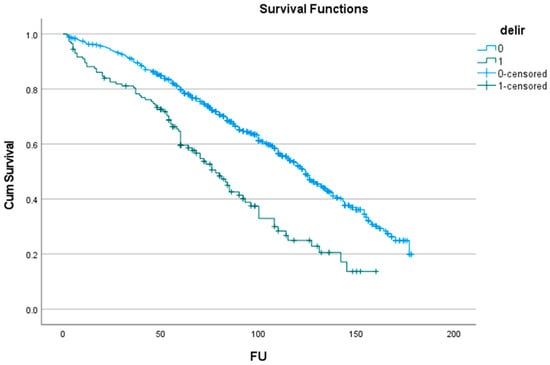

The effect of POD on long-term survival showed a significant decrease after three years, from 116 (112–120) months to 81 (73–91) months (p < 0.001). The curve showed a divergence already after 1 year, with a 5-year survival difference of about 20% and a 10-year survival difference of over 25% (Table 4 and Figure 1).

Table 4.

Effect of postoperative delirium on long-term survival.

Figure 1.

Effect of delirium (delir) on survival (FU: months of follow-up).

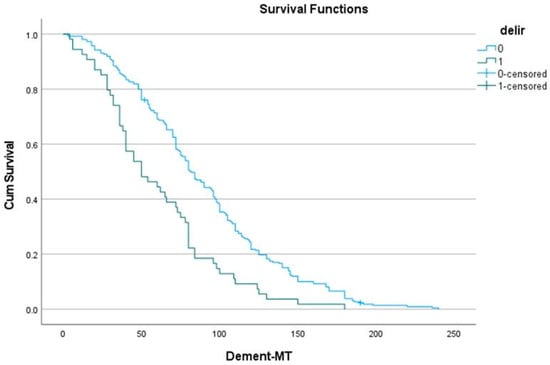

The effect of delirium on long-term dementia is shown in Table 5. Its effect was also significant (log-rank: p < 0.001), with a comparable divergence from the first postoperative year. Dementia occurred 30 months earlier in patients with POD: 60 (50–71) versus 90 (85–96) months (Figure 2). A Cox proportional hazard analysis identified POD as an independent predictor of survival (Table 6). However, age and other preoperative parameters were stronger predictors.

Table 5.

Effect of postoperative delirium on dementia development.

Figure 2.

Effect of delirium (delir) on dementia (MT: months of follow-up).

Table 6.

Predictors of long-term mortality, identified using Cox proportional hazard analysis.

4. Discussion

4.1. Observed Rates of POD and Detection Methods

POD varies in its manifestation [5,16], from drowsiness with diminished motor activity, or the so-called hypoactive type, to agitation, restlessness, and aggressive behavior. While the former type may go unnoticed, the latter is clearly evident [5]. In our population, we observed a POD with agitation in 12% of the patients, but without a specific detection instrument. This rate is within the range of POD reported in series that also did not use such an instrument [9,10,11,12,13,21,22]. These detection tools include the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM), CAM-ICU, Delirium Observation Screening (DOS), Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale (RASS), Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC), and the Organic Brain Syndrome (OBS) scale. These scales and lists differ in purpose, sensitivity, and specificity. The CAM scale was applied in most series and reflects four areas: (1) acute onset with a fluctuating course, (2) degree of inattention, (3) disorganized thinking, and (4) an altered level of consciousness. Delirium was diagnosed, with items 1 and 2 present and either item 3 or 4 displayed [14,23]. The absence of a POD screening tool may lead to underreporting, more specifically, of the hypoactive subtype. The use of these tools showed a consistently higher rate of POD, ranging between 20% and 66% [14,15,16,24,25,26]. The use of the OBS scale [15] also showed a rate of 56.1% POD, while the ICDSC showed a rate of 57%, which could be reduced to 40% with the application of the enhanced recovery protocol after cardiac surgery [17]. Remarkably, the ICDSC documented a lower rate of POD, at a level of 17.4% [3], while the daily use of the DOS scale after SAVR documented a very low prevalence of POD in octogenarian (11.0%) and younger (6.2%) patients [6].

4.2. Predictors of POD

Identifying POD predictors can help direct the screening of patients susceptible to this condition. Early detection and adequate management of POD could improve outcomes [4]. In the current series, the predictors of POD occurrence included need for revision (over five times), age above 80 years (over two times), male gender, peripheral artery disease, smoking, need for non-elective SAVR, atrial fibrillation, and TIA. The CPB and ACC times, together with concomitant CABG, were identified only in the univariate analysis. POD is associated with almost all other postoperative adverse events. Patients suffering from POD had a four times higher mortality. In the current series, the need for revision occurred mostly for bleeding and tamponade in the early postoperative phase. For this reason, we assumed this event precedes POD. No other series investigated this factor in relation to POD. A second surgery necessitates a second anesthesia and increases the likelihood of more transfusions, a prolonged ventilation time, and an ICU stay. All these factors could contribute to POD [16]. Moreover, the need for other resources, such as the need for a permanent pacemaker implantation and renal replacement therapy, was also associated with POD, which reflects associated postoperative complications [24]. Older age was identified as the second most important predictor of POD. Its effect was demonstrated in earlier analyses: with increasing age, the incidence increased from 6.6% to 17.1%. This was somehow comparable with the observed rate after SAVR in octogenarians [6], but higher compared to other series [9]. This may be an underestimation since delirium without agitation may be missed [27]. Other series also showed an association with older age [7,12,16,28,29]. Male gender was also identified as a factor in POD development in the current series, as well as in prior series [12,25,28]. Female gender may be a protective factor, which seems surprising because more female patients undergoing SAVR were in the octogenarian category [6,9,12]. In other reports, only a trend [29] or no significant effect of gender on POD was documented [7,19,24,26]. Preoperative ischemic neurologic events had an effect in some reports [26,28,29], but no major difference was documented in other reports [19,24], which may be due to low numbers. Neurological complications after cardiac surgery occurred in 43.8%; however, in most patients, this was due to a POD episode, while stroke was uncommon [16]. Stroke, which was documented using clinical and MRI assessments (6.6%), was less frequent compared to POD (28.5%), which was determined using a CAM scale [26]. Clinically overt thromboembolic events were borderline associated with POD in the current series. POD was associated with significantly increased lesion volumes in the central nervous system. “Silent” brain infarcts are common after SAVR, and POD may be a clinical sign, indicating that these ischemic phenomena are not really silent [24]. Detecting so-called silent neurologic events with MRI is not a clinical routine, which may have contributed to their underestimation. Several cardiovascular factors, such as carotid artery disease [19], atrial fibrillation [12,19], prior acute myocardial infarction [26], heart failure [16,28], and hypertension [24,26], affected the rate of POD in the current series. Some of these factors may trigger micro-emboli [19]. Previous cardiac surgery and pulmonary artery hypertension did not affect POD in the current series or in a past series [12]. Non-elective SAVR affected the current population, but it did not affect the populations in prior series [12,29]. A prolonged CPB [16,26,28], which reflects a more complex procedure [26], also affects POD.

Preoperative renal and pulmonary dysfunction were associated with POD. For chronic pulmonary dysfunction, only a trend in POD was observed [12]. Diabetes was borderline significant for POD in the current population and prior populations [12], but not in the population of another series [19,28,29]. Inflammation and infection, which were not investigated in the current series, affected POD in prior series. Increased plasma glucose and creatinine were also associated with POD in the current and prior series [16,30] and could serve as a marker for stress caused by infection or circulatory derangements. An earlier series identified alcohol use as a factor with an effect [29], but this was not considered in the current series. An increase in POD over time could be attributed to an increase in the complexity of operations [8]. Preoperative mild cognitive deficit, which was not a part of our routine preoperative assessment, was also associated with POD [16,26,28]. However, the preoperative MMSE score did not seem to affect the rate of POD in several prior series [15,25]. A prediction model for POD screened by ICDSC included an MMSE score, geriatric depression score, prior TIA or stroke, and abnormal serum albumin. After validation, the model showed only poor discriminative capacity [3]. A preoperative neurocognitive screening seems useful before cardiac surgery, but this is not a routine practice, nor is it included in STS or Euroscore [31]. The etiology of POD comprises a complex combination of predisposing factors, including advanced age, pre-existing cognitive impairment, depression, vision impairment, previous stroke, and precipitating factors, such as surgery, acute pain, malnutrition, and hospitalization [32]. Several modifiable predisposing risk factors for POD include polypharmacy, malnutrition, alcohol dependence, anemia, dehydration, depression, and sensory impairment. Non-modifiable predisposing factors include age, low level of education, history of stroke, a recent episode of delirium, and cognitive impairment. Precipitating modifiable risk factors include postoperative sedation, infection, hypoxia, metabolic derangements, sensory deprivation, physical restraints, prolonged use of catheters, and abnormal sleep–wake cycles. Non-modifiable precipitating factors include a need for an emergent surgery, major postoperative complications, and a need for ICU admission [4]. These findings indicate that POD serves as a surrogate for patient vulnerability. One remarkable nationwide survey showed that 0.27% of patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery had preoperative dementia, which remained rather constant over time. The presence of this condition increased the prevalence of POD significantly, from 4.8% to 15.5% [13]. These rates can be considered comparatively low. It seems that replacing a diseased aortic valve itself does not determine the prevalence of POD. Delirium, documented by the CAM scale, occurred significantly more often after SAVR compared to TAVI (65.8% vs. 44.4%), although these patients were older and had a higher risk score. A lower cognitive function, measured by MMSE, was also associated with delirium in patients with TAVI, but not with SAVR. The onset of POD was more unpredictable after SAVR and could occur at a later postop stage [14]. In a meta-analysis, TAVI patients had a significantly threefold lower incidence of POD measured with CAM compared to SAVR patients. Delirium could be a surrogate for comorbid conditions in patients undergoing AVR by any means [33].

4.3. Long-Term Effects of POD

In the current series, POD was associated with other complications and with an increased need for resources. Patients with POD had a prolonged hospital stay, which was also observed in earlier series [26,28,34]. POD after SAVR also has long-term consequences with respect to survival, dementia development, and other outcomes, such as a decreased quality of life and the need for admission to a skilled nursing facility. Mean survival decreased in the current population by almost 3 years. Decreased survival was also observed in prior reviews and series [18,24,26,30] and may be independent of age, gender, and comorbid conditions. This is confirmed by the current results, which identified POD as a predictor of reduced long-term survival. Most of these series involved patients with CABG. The effect of POD on survival was not documented at 6 months postoperative [18], but it was identified as a factor at about 2 years after cardiac surgery in general [34]. In one series, POD was labeled as a robust predictor after 10 years [18]. These periods were well beyond the immediate postoperative period. In the current series, the survival curves of patients with versus without POD showed a divergence from the start of the follow-up. In the current investigation, dementia developed more frequently in patients with POD and about 2.5 years sooner. Dementia in later life was also increased in patients with POD in prior series [18,26,28,30,34]. Lower preoperative cognitive function and POD were more predictive of long-term dementia after cardiac surgery compared to age and female gender, while operative parameters, the use of CPB, and postoperative cerebrovascular events had no predictive effect [15]. The role of inhalation anesthetics in the later development of dementia remains uncertain [4]. In one series [15], dementia developed after cardiac surgery in 26.3% of patients during the follow-up, which is higher compared to our observations [35]. Overall neurocognition declined at 90 days in patients who suffered from POD compared to those without POD [26]. The Cognitive Failure Total Score at mid-term was significantly lower in patients who suffered from POD, especially with respect to memory, small daily tasks, and decision-making [7]. Recovery within the first postoperative year was noticed in most patients, but if POD was prolonged, this recovery was often partial [30]. There was also an increase in dependency for mobility, a decrease in quality of life [7,18,26,30], with a higher need for admission to a skilled nursing facility [18,24], and rehospitalization at 1 year [24].

The interrelationship between POD and dementia is not fully understood. Dementia is an important risk factor for POD [13,30], but, inversely, POD is recognized as an independent predictor for the subsequent development of dementia [30]. On the one hand, POD could be a marker of a vulnerable brain or a diminished “cognitive reserve”. On the other hand, POD itself could be “toxic” to the brain and cause neurologic damage by accelerating an otherwise slowly progressing neurodegenerative disorder [20,30]. Both mechanisms could occur simultaneously [30] after cardiac surgery. Neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory markers are elevated after cardiac surgery [34]. The cardiac surgical procedure, with its associated inflammation, oxidative stress, hypoxemia, and damage to the blood–brain barrier, seemed to play a more important role compared to the choice of anesthetic products [20], but the latter is questioned [28]. Comparing the pre- and post-surgery levels of a critical biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease, i.e., amyloid-β42 (Aβ42), in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with POD could support this hypothesis. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) is another neuroinflammatory marker that could be a link between inflammation and neurodegenerative events. The role of these biomarkers, however, is not yet fully understood [20]. Beta-amyloid may play a role, especially after episodes of hypoxia, hypoglycemia, impaired circulation, and free radicals, as a marker of oxidative stress. Apoptosis and microglial cell activation could provide another mechanism. Furthermore, S100B protein, a marker of damage to astrocytes, is elevated in patients with POD. However, if POD is part of the “dementia trajectory”, the observed pathological substrates may be different from the classical mechanisms, such as Lewy body pathology [30]. Elevated serum tau levels up to three months after cardiac surgery with CPB were correlated to preoperative tau levels and hence, to an ongoing neurodegenerative condition [36,37]. This pre-existing brain vulnerability could be related to POD [36]. Under healthy conditions, tau protein, which is an axonal soluble protein, regulates microtubular assembly and maintains structural stability. In the diseased brain, tau protein becomes phosphorylated to a high degree. This causes the microtubules to disassemble. Free tau molecules aggregate into paired helical filaments and neurofibrillary tangles. These filaments and ß-amyloid peptide form amyloid plaques, which are the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s dementia. Tau protein forms insoluble filaments that accumulate as neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s dementia and related conditions [37]. The ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1) is a deubiquitinating enzyme primarily found in neurons that plays a crucial role in the cellular pathway that regulates protein degradation. This protein is implicated in neurodegenerative diseases and in brain injuries. This hydrolase is one of the proteins critical to withstanding stress, and it peaks 24 h after an operation. The postoperative pattern of tau and UCH-L1 protein levels in plasma suggests that their leakage into the circulation is a combination of their increased expression in neuronal tissues, as well as ongoing damage. Neuronal tissue inflammation and microglial cell activation could be initiated using CPB and become self-sustaining [36]. These observations support the notion of preoperative degenerative neurological conditions, worsened by the stress imposed by cardiac surgery. Inflammation, the pharmacologic effect of anesthetics, fluctuations in blood pressure, oxygen supply, and changes in pH, as well as micro-emboli, ischemia–reperfusion, and oxidative stress, could contribute to POD and neuronal injury. Oxidative stress could be mitigated by an intact blood–brain barrier unless it is disrupted by oxidative damage [28].

4.4. Treatment of POD

Perioperative management of POD includes its prevention, which could be possible in 30% to 40% of cases [30], and its timely recognition, which is facilitated by measurement scales. Reorientation of patients by providing visual and hearing aids, early mobilization, control of excessive noise, and sleep enhancement during the night [5] could ameliorate POD. Adequate sleep is important after surgery since the normal sleep pattern is often affected. However, a fragmented sleep pattern may resemble hypoactive delirium. This may be the case in elderly patients, in whom POD occurs more often [38]. Reorientation using pictures of relatives and other familiar objects could reduce the incidence of POD, but their value seems more preventive than as a treatment of established delirium [25,39,40]. An individualized patient approach with cooperation between hospital staff and family would improve contact with and recovery of patients during this difficult period. Providing families with adequate information and education on POD could also decrease stress, anxiety, embarrassment, uncertainty, and anger during contacts with patients suffering from POD. Medical support is vital in lowering the barrier between patients and their relatives [39,40,41]. Another non-pharmacologic approach to POD includes preventing or managing infection, metabolic disturbances, and hypoxia [5]. A pharmacological approach is a second-line option [4,5]. This includes non-opioid pain management. A delayed diagnosis of POD and treatment may cause additional harm. An enhanced recovery protocol after coronary and valve surgery with on-table extubation resulted in fewer cases of POD. Timely diagnosis and treatment are important because of their association with higher morbidity and mortality. Fast-track anesthesia and reduced sedatives help patients regain orientation with respect to place and time, which seems to lower the rate of POD [17]. An adequate treatment of POD increased long-term cognition [30].

This is a retrospective analysis with inherent limitations. By including many patients consecutively, the risk for bias was limited. Detecting preoperative mild cognitive deficit was not a clinical routine, but preoperative dementia in our patients could be ruled out by anamnesis, physical examination, and subsequent technical explorations. An instrument was not routinely used to detect POD, which is a major limitation. Medical files registered delirium based on the observation of disorientation with respect to time, space, and persons. The use of a chart as an additional detection tool for POD could augment the diagnostic accuracy if used in combination with a classic detection scale [42]. The currently observed rate of POD falls within the range found in prior series in which no such measurement tool was used. This makes the current findings plausible. We did not record psychotropic medication and did not use a measurement scale to detect POD without agitation. Postoperative inflammatory parameters were not included in the analysis. The development of dementia could be missed in patients admitted to skilled nursing facilities, but this was kept to a minimum by using records in electronic medical databases. Since this is a monocentric study, its results are not necessarily applicable in all its aspects. However, the size of the patient sample and the long duration of the follow-up strengthen its findings.

5. Conclusions

Several conclusions can be drawn from this large-scale series with long follow-up data. The prevalence of POD in the current series is relatively low, but it may be underestimated by the lack of screening tools. An active surveillance is recommended using validated measurement scales and charts, especially in patients with known risk factors. The interaction between POD and dementia in older people is not fully understood, but POD seems to be a marker of a vulnerable brain and could lead to further cognitive function decline. Neurodegenerative and inflammatory markers could indicate that POD itself can be harmful for a vulnerable brain. If POD is “toxic” for the brain, prevention and timely treatment may diminish later cognitive decline. Targeting oxidative stress and preserving the blood–brain barrier could diminish the prevalence of POD. The current results suggest that POD is an independent predictor of reduced survival and a risk factor for future dementia; therefore, it warrants a neurological follow-up in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.M.; methodology, W.M. and I.D.; formal analysis, W.M. and I.D.; investigation, W.M., I.D., K.D. and A.V.; data curation, W.M., I.D., K.D. and A.V.; writing—original draft preparation, W.M.; writing—review and editing, W.M., I.D., K.D. and A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the ZNA Ethical Committee under number 2656 in 2001, which was extended in 2011 and 2017.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived by the ZNA Ethical Committee.

Data Availability Statement

The results were derived from a multipurpose database, from which several more publications will be derived. These data are not yet publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Deblier, I.; Dossche, K.; Vanermen, A.; Mistiaen, W. Operation in the gray zone: Is SAVR still useful in patients aged between 75 and 80 years? Future Cardiol. 2024, 20, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistiaen, W.; Deblier, I.; Dossche, K.; Vanermen, A. Clinical Outcomes after Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in 681 Octogenarians: A Single-Center Real-World Experience Comparing the Old Patients with the Very Old Patients. Geriatrics 2024, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wueest, A.S.; Berres, M.; Bettex, D.A.; Steiner, L.A.; Monsch, A.U.; Goettel, N. Independent External Validation of a Preoperative Prediction Model for Delirium After Cardiac Surgery: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2023, 37, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogma, D.F.; Milisen, K.; Rex, S.; Al Tmimi, L. Postoperative delirium: Identifying the patient at risk and altering the course: A narrative review. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Care 2023, 2, e0022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossie, A.; Regasa, T.; Neme, D.; Awoke, Z.; Zemedkun, A.; Hailu, S. Evidence-Based Guideline on Management of Postoperative Delirium in Older People for Low Resource Setting: Systematic Review Article. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2022, 15, 4053–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen Klomp, W.W.; Nierich, A.P.; Peelen, L.M.; Brandon Bravo Bruinsma, G.J.; Dambrink, J.E.; Moons, K.G.M.; van’t Hof, A.W.J. Survival and quality of life after surgical aortic valve replacement in octogenarians. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2016, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, S.; Hensens, A.G.; Schuurmans, M.J.; van der Palen, J. Consequences of delirium after cardiac operations. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2012, 93, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deblier, I.; Dossche, K.; Vanermen, A.; Mistiaen, W. The Outcomes for Different Biological Heart Valve Prostheses in Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement before and after the Introduction of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Prosthesis 2024, 6, 708–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böning, A.; Lutter, G.; Mrowczynski, W.; Attmann, T.; Bödeker, R.; Scheibelhut, C.; Cremer, J. Octogenarians undergoing combined aortic valve replacement and myocardial revascularization: Perioperative mortality and medium-term survival. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2010, 58, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Amore, A.; Aquino, T.M.; Pagliaro, M.; Lamarra, M.; Zussa, C. Aortic valve replacement with and without combined coronary bypass grafts in very elderly patients: Early and long-term results. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2012, 41, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Habib, A.M.; Hussain, A.; Jarvis, M.; Cowen, M.E.; Chaudhry, M.A.; Loubani, M.; Cale, A.; Ngaage, D.L. Changing clinical profiles and in-hospital outcomes of octogenarians undergoing cardiac surgery over 18 years: A single-centre experience. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2019, 28, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oettinger, V.; Kaier, K.; von Zur Mühlen, C.; Zehender, M.; Bode, C.; Beyersdorf, F.; Stachon, P.; Bothe, W. Impact of Procedure Volume on the Outcomes of Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2024, 72, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.; Eitan, T.; Dewan, K.C.; Zhou, G.; Rosinski, B.F.; Koroukian, S.M.; Svensson, L.G.; Gillinov, A.M.; Soltesz, E.G. National outcomes for dementia patients undergoing cardiac surgery in a pre-structural era. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2024, 19, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eide, L.S.; Ranhoff, A.H.; Fridlund, B.; Haaverstad, R.; Hufthammer, K.O.; Kuiper, K.K.; Nordrehaug, J.E.; Norekvål, T.M.; CARDELIR Investigators. CARDELIR Investigators. Comparison of frequency, risk factors, and time course of postoperative delirium in octogenarians after transcatheter aortic valve implantation versus surgical aortic valve replacement. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015, 115, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingehall, H.C.; Smulter, N.S.; Lindahl, E.; Lindkvist, M.; Engström, K.G.; Gustafson, Y.G.; Olofsson, B. Preoperative Cognitive Performance and Postoperative Delirium Are Independently Associated with Future Dementia in Older People Who Have Undergone Cardiac Surgery: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, 1295–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teller, J.; Gabriel, M.M.; Schimmelpfennig, S.D.; Laser, H.; Lichtinghagen, R.; Schäfer, A.; Fegbeutel, C.; Weissenborn, K.; Jung, C.; Hinken, L.; et al. Stroke, Seizures, Hallucinations and Postoperative Delirium as Neurological Complications after Cardiac Surgery and Percutaneous Valve Replacement. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 9, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, A.; Conrads, H.; Rosenberger, J.; Creutzenberg, M.; Graf, B.; Foltan, M.; Blecha, S.; Stadlbauer, A.; Floerchinger, B.; Tafelmeier, M.; et al. Effects of Implementing an Enhanced Recovery After Cardiac Surgery Protocol with On-Table Extubation on Patient Outcome and Satisfaction-A Before-After Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, E.; Beggs, T.; Hassan, A.; Denault, A.; Lamarche, Y.; Bagshaw, S.; Elmi-Sarabi, M.; Hiebert, B.; Macdonald, K.; Giles-Smith, L.; et al. Long-term effects of postoperative delirium in patients undergoing cardiac operation: A systematic review. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2016, 102, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körber, M.I.; Schäfer, M.; Vimalathasan, R.; Mauri, V.; Iliadis, C.; Metze, C.; Freyhaus, H.T.; Rudolph, V.; Baldus, S.; Pfister, R. Periinterventional inflammation and blood transfusions predict postprocedural delirium after percutaneous repair of mitral and tricuspid valves. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2021, 110, 1921–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabi Raberi, V.; Solati Kooshk Qazi, M.; Zolfi Gol, A.; GhorbaniNia, R.; Kahourian, O.; Faramarz Zadeh, R. Postoperative Delirium and Dementia in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Galen Med. J. 2023, 12, e3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggebrecht, H.; Bestehorn, K.; Rassaf, T.; Bestehorn, M.; Voigtländer, T.; Fleck, E.; Schächinger, V.; Schmermund, A.; Mehta, R.H. In-hospital outcomes after transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement in younger patients less than 75 years old: A propensity-matched comparison. EuroIntervention 2018, 14, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghiyev, Z.T.; Bechtel, M.; Schlömicher, M.; Useini, D.; Taghi, H.N.; Moustafine, V.; Strauch, J.T. Early-Term Results of Rapid-Deployment Aortic Valve Replacement versus Standard Bioprosthesis Implantation Combined with Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2023, 71, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instenes, I.; Fridlund, B.; Amofah, H.A.; Ranhoff, A.H.; Eide, L.S.; Norekvål, T.M. ‘I hope you get normal again’: An explorative study on how delirious octogenarian patients experience their interactions with healthcare professionals and relatives after aortic valve therapy. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2019, 18, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browndyke, J.N.; Tomalin, L.E.; Erus, G.; Overbey, J.R.; Kuceyeski, A.; Moskowitz, A.J.; Bagiella, E.; Iribarne, A.; Acker, M.; Mack, M.; et al. Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network (CTSN) Investigators. Infarct-related structural disconnection and delirium in surgical aortic valve replacement patients. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2024, 11, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Martínez, C.; Casado-Verdejo, I.; Fernández-Fernández, J.A.; Sánchez-Valdeón, L.; Bello-Corral, L.; Méndez-Martínez, S.; Sandoval-Diez, A.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; García-Suárez, M.; Fernández-García, D. Projection ofvisual material on postoperative delirium in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: A double blind randomized clinical trial. Medicine 2024, 103, e39470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messé, S.R.; Overbey, J.R.; Thourani, V.H.; Moskowitz, A.J.; Gelijns, A.C.; Groh, M.A.; Mack, M.J.; Ailawadi, G.; Furie, K.L.; Southerland, A.M.; et al. Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network (CTSN) Investigators. The impact of perioperative stroke and delirium on outcomes after surgical aortic valve replacement. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2024, 167, 624–633.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amofah, H.A.; Broström, A.; Fridlund, B.; Bjorvatn, B.; Haaverstad, R.; Hufthammer, K.O.; Kuiper, K.K.; Ranhoff, A.H.; Norekvål, T.M.; On Behalf of the CARDELIR Investigators. Sleep in octogenarians during the postoperative phase after transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2016, 15, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, M.G.; Hughes, C.G.; DeMatteo, A.; O’Neal, J.B.; McNeil, J.B.; Shotwell, M.S.; Morse, J.; Petracek, M.R.; Shah, A.S.; Brown, N.J.; et al. Intraoperative Oxidative Damage and Delirium after Cardiac Surgery. Anesthesiology 2020, 132, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J.L.; Jones, R.N.; Levkoff, S.E.; Rockett, C.; Inouye, S.K.; Sellke, F.W.; Khuri, S.F.; Lipsitz, L.A.; Ramlawi, B.; Levitsky, S.; et al. Derivation and validation of a preoperative prediction rule for delirium after cardiac surgery. Circulation 2009, 119, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, T.G.; Davis, D.; Growdon, M.E.; Albuquerque, A.; Inouye, S.K. The interface of delirium and dementia in older persons. Lancet 2015, 14, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, E.; Thangathurai, G.; Saripella, A.; Yan, E.; Englesakis, M.; Nagappa, M.; Chung, F. Postoperative Outcomes in Elderly Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery with Preoperative Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Anesth. Analg. 2023, 136, 1016–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, C.C.; Hung, K.C.; Chang, Y.P.; Liu, C.C.; Cheng, W.J.; Wu, J.Y.; Li, Y.-Y.; Lin, T.-C.; Sun, C.-K. Association of general anesthesia exposure with risk of postoperative delirium in patients receiving transcatheter aortic valve replacement: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavridis, D.; Runkel, A.; Starvridou, A.; Fischer, J.; Fazzini, L.; Kirov, H.; Wacker, M.; Wippermann, J.; Doenst, T.; Caldonazo, T. Postoperative delirium in patients undergoing TAVI versus SAVR—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2024, 55, 101544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadlonova, M.; Vogelgsang, J.; Lange, C.; Günther, I.; Wiesent, A.; Eberhard, C.; Ehrentraut, J.; Kirsch, M.; Hansen, N.; Esselmann, H.; et al. Identification of risk factors for delirium, cognitive decline, and dementia after cardiac surgery (FINDERI-find delirium risk factors): A study protocol of a prospective observational study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2022, 22, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deblier, I.; Dossche, K.; Vanermen, A.; Mistiaen, W. Dementia Development during Long-Term Follow-Up after Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement with a Biological Prosthesis in a Geriatric Population. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 11, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMeglio, M.; Furey, W.; Hajj, J.; Lindekens, J.; Patel, S.; Acker, M.; Bavaria, J.; Szeto, W.Y.; Atluri, P.; Haber, M.; et al. Observational study of long-term persistent elevation of neurodegeneration markers after cardiac surgery. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, R.; Baglietto-Vargas, D.; LaFerla, F.M. The role of tau in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2011, 17, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amofah, H.A.; Broström, A.; Instenes, I.; Fridlund, B.; Haaverstad, R.; Kuiper, K.; Ranhoff, A.H.; Norekvål, T.M. CARDELIR Investigators. Octogenarian patients’ sleep and delirium experiences in hospital and four years after aortic valve replacement: A qualitative interview study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e039959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogma, D.F.; Venmans, E.; Al Tmimi, L.; Tournoy, J.; Verbrugghe, P.; Jacobs, S.; Fieuws, S.; Milisen, K.; Adriaenssens, T.; Dubois, C.; et al. Postoperative delirium and quality of life after transcatheter and surgical aortic valve replacement: A prospective observational study. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2023, 166, 156–166.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozga, D.; Krupa, S.; Witt, P.; Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W. Nursing Interventions to Prevent Delirium in Critically Ill Patients in the Intensive Care Unit during the COVID19 Pandemic-Narrative Overview. Healthcare 2020, 8, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, S.; Mȩdrzycka-Dabrowska, W.; Friganović, A.; Religa, D.; Krupa, S. Family experiences and attitudes toward care of ICU patients with delirium: A scoping review. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1060518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krewulak, K.D.; Hiploylee, C.; Ely, E.W.; Stelfox, H.T.; Inouye, S.K.; Fiest, K.M. Adaptation and Validation of a Chart-Based Delirium Detection Tool for the ICU (CHART-DEL-ICU). J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).