Trends in Alzheimer’s Disease Mortality in the Mississippi Delta, 2016–2022

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Overall Trends

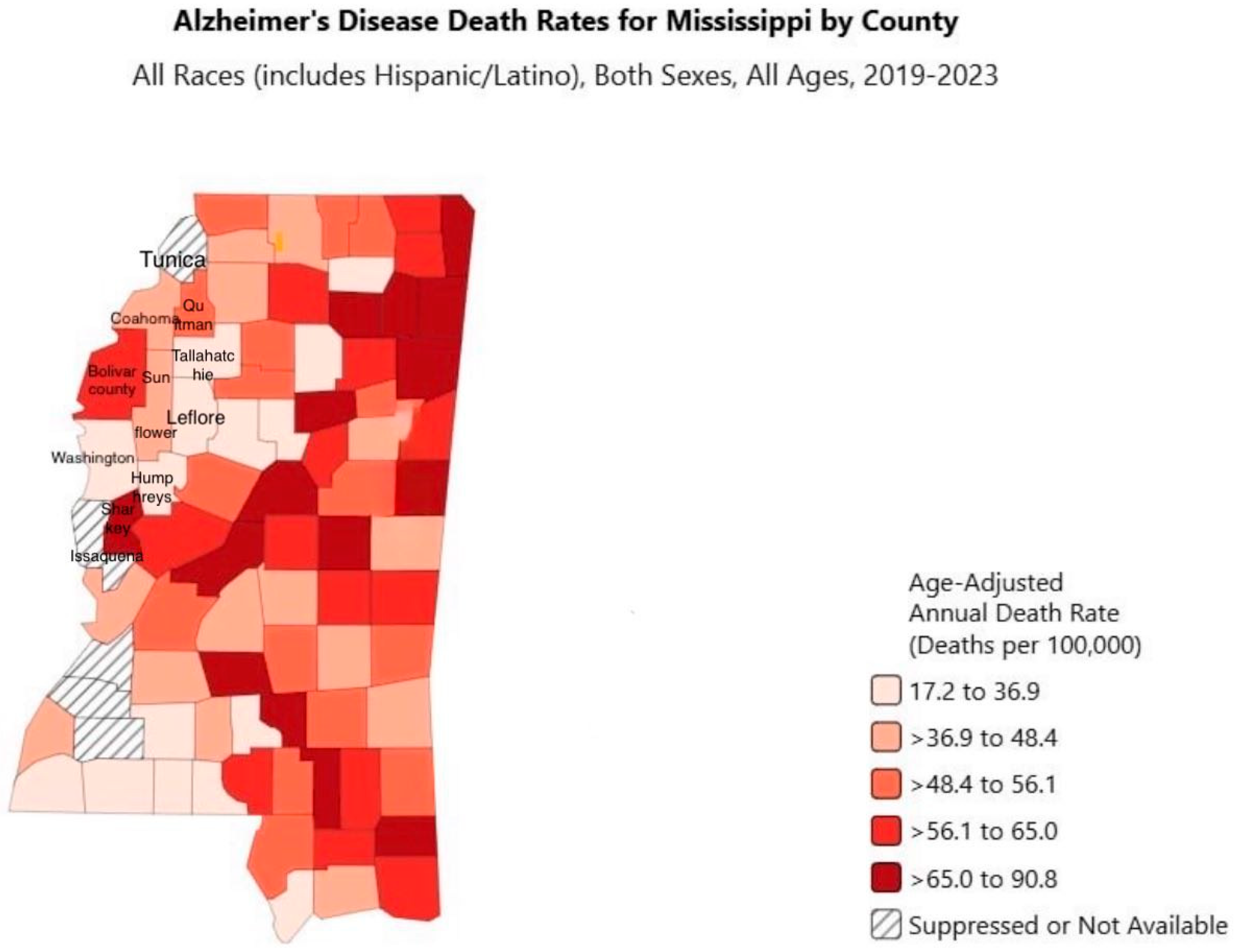

3.2. Alzheimer’s Disease by County, Race, and Gender in the Mississippi Delta

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 2024 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 3708–3821. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.A.; Jenkins, B.; Addison, C. Mortality Trends in Alzheimer’s Disease in Mississippi, 2011–2021. Diseases 2023, 11, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- About Alzheimer’s. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/alzheimers-dementia/about/alzheimers.html (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Matthews, K.A.; Xu, W.; Gaglioti, A.H.; Holt, J.B.; Croft, J.B.; Mack, D.; McGuire, L.C. Racial and Ethnic Estimates of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias in the United States (2015–2060) in Adults Aged ≥65 Years. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018, 15, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhole, R.P.; Chikhale, R.V.; Rathi, K.M. Current Biomarkers and Treatment Strategies in Alzheimer Disease: An Overview and Future Perspectives. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2024, 16, 8–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2025 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2025, 21, e70235. [CrossRef]

- Skaria, A. The Economic and Societal Burden of Alzheimer Disease: Managed Care Considerations. Available online: https://www.ajmc.com/view/the-economic-and-societal-burden-of-alzheimer-disease-managed-care-considerations (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Mortality from Alzheimer’s Disease in the United States: Data for 2000 and 2010. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db116.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Campbell-Taylor, I. Contribution of Alzheimer Disease to Mortality in the United States. Neurology 2014, 83, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health Action in Mississippi. Available online: https://www.alz.org/professionals/public-health/state-overview/mississippi (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Healthy Aging Data Report Highlights from Mississippi 2023. Available online: https://msdh.ms.gov/page/resources/19858.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Alzheimer’s Disease Mortality by State. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/state-stats/deaths/alzheimers.html (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Ho, J.Y.; Franco, Y. The Rising Burden of Alzheimer’s Disease Mortality in Rural America. SSM-Popul. Health 2022, 17, 101052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elo, I.T.; Hendi, A.S.; Ho, J.Y.; Vierboom, Y.C.; Preston, S.H. Trends in Non-hispanic White Mortality in the United States by Metropolitan-Nonmetropolitan Status and Region, 1990–2016. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2019, 45, 549–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healthy People 2030. Available online: https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/dementias (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Langa, K.M.; Larson, E.; Crimmins, E.M.; Faul, J.; Levine, D.; Kabeto, M.; Weir, D. A Comparison of the Prevalence of Dementia in the United States in 2000 and 2012. Innov. Aging 2017, 1 (Suppl. 1), 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glymour, M.M.; Manly, J.J. Lifecourse Social Conditions and Racial and Ethnic Patterns of Cognitive Aging. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2008, 18, 223–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mississippi Statisically Automated Health Resource System. Available online: https://mstahrs.msdh.ms.gov/ (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Joinpoint Regression Program. Available online: https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/ (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- NIMHD HDPulse Data Portal: Mortality Map. Available online: https://hdpulse.nimhd.nih.gov/data-portal/mortality/map (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- 2022 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35289055/ (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Alzheimer’s Disease and Healthy Aging Data Portal. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthy-aging-data/data-portal/index.html (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Ebersole, R.C. Third World Mississippi Shows Failure of Conservative Policies. Available online: https://www.peoplesworld.org/article/third-world-mississippi-shows-failure-of-conservative-policies (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Zahodne, L.B.; Sol, K.; Scambray, K.; Lee, J.H.; Palms, J.D.; Morris, E.P.; Taylor, L.; Ku, V.; Lesniak, M.; Melendez, R.; et al. Neighborhood Racial Income Inequality and Cognitive Health. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 5338–5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzra. Ways to Slow the Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. Available online: https://www.alzra.org/blog/ways-to-slow-the-progression-of-alzheimers-disease/ (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Butler, K.R.; Lafferty, D.; Naylor, S.B.; Tarver, K.C. Social Determinants of Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia: The Mississippi Landscape. J. Public Health Deep South 2024, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Women and Alzheimer’s. Available online: https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers/women-and-alzheimer-s (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Mielke, M.M. Sex and Gender Differences in Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia. Psychiatr. Times 2018, 35, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C.; et al. Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care: 2020 Report of The Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Charpignon, M.-L.; Raquib, R.V.; Wang, J.; Meza, E.; Aschmann, H.E.; DeVost, M.A.; Mooney, A.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Riley, A.R.; et al. Excess Mortality with Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementias as an Underlying or Contributing Cause during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the U.S. JAMA Neurol. 2023, 80, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestre, G.; Hill, C.; Griffin, P.; Hall, S.; Hu, W.; Flatt, J.; Babulal, G.; Thorpe, R.; Henderson, J.N.; Buchwald, D.; et al. Promoting Diverse Perspectives: Addressing Health Disparities Related to Alzheimer’s and All Dementias. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 3099–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akindahunsi, T.; Fadojutimi, B.L.; Olasunkanmi, F.D.; Tundealao, S. Public Health Policies and Programs for Alzheimer’s and Dementia: A Data-Driven Evaluation of Effectiveness and Areas for Improvement in the United States. Int. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. J. 2024, 21, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Rucker, T.D. Understanding and Addressing Racial Disparities in Health Care. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4194634/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

| Characteristic | No. of Cases (Age-Adjusted Rates) | No. of Cases (Age-Adjusted Rates) | AAPC (95% CI) | Trend Segment 1 (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2022 | 2016–2022 | Years | APC | ||

| Counties | Bolivar | 17 (50.8) | 19 (55) | 7.4 (−5.3 to 29.1) | 2016–2022 | 7.4 (−5.3 to 29.1) |

| Coahoma | 7 (24.1) | 10 (41.9) | 1.5 (−16.7 to 25.1) | 2016–2022 | 1.5 (−16.7 to 25.1) | |

| Humphreys | 8 (89.2) | 5 (46.4) | −10.3 (−27.6 to −1.6) † | Segment 1: 2016–2020 Segment 2: 2020–2022 | −25 (−54.9 to −8.1) 28.3 (−29.6 to 111.1) | |

| Leflore | 14 (41.9) | 10 (37.1) | −9.3 (−26.4 to 3.4) | 2016–2022 | −9.3 (−26.4 to 3.4) | |

| Quitman | * (46.4) | * (64) | 5 (−16.7 to 39.7) | 2016–2022 | 5 (−16.7 to 39.7) | |

| Sharkey | * (53.4) | * (53.3) | 13.4 (1.4 to 31.4) † | 2016–2022 | 13.4 (1.4 to 31.4) | |

| Sunflower | 12 (49.6) | 14 (54.7) | 1.6 (−7.9 to 12.6) | 2016–2022 | 1.6 (−7.9 to 12.6) | |

| Tallahatchie | 7 (43.7) | * (29.1) | −1.3 (−18.6 to 24.5) | 2016–2022 | −1.3 (−18.6 to 24.5) | |

| Washington | 8 (15.3) | 11 (24.2) | −1.5 (−10.2 to 7.8) | 2016–2022 | −1.5 (−10.2 to 7.8) | |

| Characteristic | No. of Cases (Age-Adjusted Rates) | No. of Cases (Age-Adjusted Rates) | AAPC (95% CI) | Trend Segment 1 (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2022 | 2016–2022 | Years | APC | ||

| Race | White | 61 (56.6) | 37 (39.7) | −2.9 (−12.3 to 7.6) | 2016–2022 | −2.9 (−12.3 to 7.6) |

| Black | 19 (17.4) | 45 (42.1) | 8.3 (2.6 to 16) | 2016–2022 | 8.3 (2.6 to 16) | |

| Characteristic | No. of Cases (Age-Adjusted Rates) | No. of Cases (Age-Adjusted Rates) | AAPC (95% CI) | Trend Segment 1 (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2022 | 2016–2022 | Years | APC | ||

| Gender | Male | 24 (32.4) | 21 (28.5) | 2.5 (−8.9 to 15.7) | 2016–2022 | 2.5 (−8.9 to 15.7) |

| Female | 56 (39.1) | 61 (46.4) | 1.6 (−6.7 to 10.9) | 2016–2022 | 1.6 (−6.7 to 10.9) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gavari, N.; Adjei, J.; Barner, Y.; Mitra, A.K.; Moore, S.; Jones, E. Trends in Alzheimer’s Disease Mortality in the Mississippi Delta, 2016–2022. J. Dement. Alzheimer's Dis. 2025, 2, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdad2040044

Gavari N, Adjei J, Barner Y, Mitra AK, Moore S, Jones E. Trends in Alzheimer’s Disease Mortality in the Mississippi Delta, 2016–2022. Journal of Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease. 2025; 2(4):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdad2040044

Chicago/Turabian StyleGavari, Nafiseh, Jazmin Adjei, Yalanda Barner, Amal K. Mitra, Sheila Moore, and Elizabeth Jones. 2025. "Trends in Alzheimer’s Disease Mortality in the Mississippi Delta, 2016–2022" Journal of Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease 2, no. 4: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdad2040044

APA StyleGavari, N., Adjei, J., Barner, Y., Mitra, A. K., Moore, S., & Jones, E. (2025). Trends in Alzheimer’s Disease Mortality in the Mississippi Delta, 2016–2022. Journal of Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease, 2(4), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdad2040044