Abstract

Background/Objectives: In this study, we aimed to examine the changes in players’ interest/enjoyment, perceived competence, and value/usefulness through an 11-week soccer training program, using a randomized experimental study. Methods: Overall, 175 children aged 9–12 years applied to join the soccer training program at a free soccer school. Of the 175 applicants, 100 were randomly chosen to participate in the soccer training program in the intervention group (IG), whereas the other 75 children were in the control group (CG). Both groups completed a questionnaire with validated items related to interest/enjoyment, perceived competence, and value/usefulness before (pre-test) and after (post-test) the soccer training program. Results: The main finding was that participation in the 11-session soccer training program did not affect the children’s perceived competence, interest/enjoyment, or value/usefulness in a positive or negative direction compared to the CG. Another main finding was a significant decrease in interest/enjoyment from pre-test to post-test in both the control group and the intervention group. Also, the control group had higher values of perceived competence than the intervention group at both pre-test and post-test. However, the effect sizes are very small in both groups, and the practical relevance is small. Conclusions: This study demonstrated that participation at the 11-session soccer training program did not affect the children’s perceived competence, interest/enjoyment, and value/usefulness in a positive or negative direction compared to the CG. Future studies should include longer intervention periods with more weekly and overall training sessions.

1. Introduction

Numerous children and youth in Norway participate in sports, with the majority participating during their upbringing (Bakken, 2019). Adolescents’ participation in sports can contribute positively to their physical, mental, and social health (Eime et al., 2013; Cheng et al., 2018; Lagestad & Mehus, 2018; Lagestad et al., 2019). It can also predict activity levels in adulthood (Belanger et al., 2015; Kjønniksen et al., 2009). Despite the high participation rates among children and youth, there is a noticeable dropout trend during adolescence, with data indicating that approximately 60% of those who have participated in youth sports in Norway quit before the age of 18 (Ungdata, 2020).

This finding is also supported by international research. A meta-analysis (review article) by Møllerløkken et al. (2015) showed that the annual average dropout rate in youth soccer (across age cohorts) was 23.9%. This annual dropout rate was stable in the age group of 10–18 years (or throughout adolescence). Temple and Crane (2018) reported that the proportion of children and adolescents who quit organized soccer from one season to another varied from 18 to 36% and highlighted lower perceived competence, unmet basic needs, and lack of enjoyment as important factors relating to dropout.

Across the world, traditional soccer training programs for children are often organized and arranged by professional soccer companies, and many children attend such programs. These programs typically run over a set period, with dedicated coaches and a certain number of training sessions scheduled throughout. Such programs may contribute positively to children’s physical, mental, and social health (Eime et al., 2013; Cheng et al., 2018; Lagestad & Mehus, 2018; Lagestad et al., 2019). However, little research has been conducted related to how such programs affect children’s motivation and perceived competence. The aim of our study is to examine whether participation in a soccer training program changes young players’ motivation to play soccer.

1.1. Interest/Enjoyment, Perceived Competence and Value/Usefulness

To examine different aspects of young players’ motivation, the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is very relevant. Self-Determination Theory consists of six mini-theories, each developed to explain different aspects of human motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2017). This theory is widely used to study motivation in children and youth sports because it describes how to maintain joy and motivation in sports participation over time. The outcome variables in this study, namely interest/enjoyment, perceived competence, and value/usefulness, are seen through the lens of SDT. There is particular emphasis on three of the six mini-theories: Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET), Basic Psychological Needs Theory (BPNT), and Organismic Integration Theory (OIT). CET addresses the effects of social contexts on intrinsic motivation and highlights the critical roles of competence and autonomy support in fostering intrinsic motivation. External events affect intrinsic motivation for an activity by influencing the perceived competence at that activity (Ryan & Deci, 2017). BPNT is based on the argument that well-being and optimal functioning is predicted from autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Therefore, contexts that supports these needs are important. The satisfaction of all three needs is needed to change from controlled to more autonomous forms of motivation and for experiencing intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2017). OIT is about the social contexts that enhance or forestall internalization. More integrated forms of internalization lead to higher quality of behavior, and more effective performance. Positive experiences come from the behavior being regulated through more integrated or autonomous forms of motivation. Autonomous motivation consists of intrinsic motivation and the two types of extrinsic motivation (identified and integrated regulation) where the individual has identified with the value of the activity (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

Interest/enjoyment is conceptualized as a measure of intrinsic motivation as described in the method section. Vallerand et al. (1987) highlighted that intrinsic motivation is particularly significant because it is associated with long-term enjoyment, interest and participation in sports. Intrinsically motivated behavior is characterized by engaging in an activity for sheer enjoyment (Ryan & Deci, 2017). The eagerness to actively develop new skills and challenge oneself, even in the absence of external rewards, is an intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2007). Back et al. (2022) studied 738 soccer players (boys and girls) aged 11–17 years and demonstrated that lower intrinsic motivation was the most significant factor associated with dropout among young soccer players (aged ≤ 13.5 years). Even a slight reduction in intrinsic motivation was identified as a risk factor for dropout among younger soccer players.

Perceived competence is theorized to be a positive predictor of intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Within the SDT and the micro-theory BPNT, perceived competence is associated with the fundamental need for competence (Ryan & Deci, 2017). This need pertains to the intrinsic human desire to achieve and develop knowledge and personal skills (Strandkleiv, 2006). In the SDT, competence is one of the three basic psychological needs. Satisfying these three fundamental needs leads to a higher degree of intrinsic motivation (Strandkleiv, 2006). Perceived competence involves the feeling of proficiency in the activities one engages in. The more competent a player feels, the more intrinsic motivation is generated (Sun & Chen, 2010). Developing perceived competence is crucial to reduce dropout rates in youth sports (Balish et al., 2014). A review article by Temple and Crane (2018) showed that low perceived competence is a significant factor causing youth to drop out of soccer.

The value/usefulness variable in this study indicates the extent to which adolescents find their soccer activities meaningful and beneficial. This means that, as stated within the SDT micro-theory OIT, an internalization and self-regulation of the activities they perceive as useful or valuable will happen (McAuley et al., 1989). The value/usefulness variable is linked to an internalization process associated with changes in motivational quality among those who score high on this variable. This involves more prominent autonomous forms of motivation, such as identified and integrated regulations. In identified regulations, individuals accept the value of the activity and consider it important (Ulstad, 2021). In integrated regulation, the activity is internalized and viewed as part of oneself (Ulstad, 2021). The activity is closely tied to athletes’ values and is considered a part of their identity (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Recognizing the value and usefulness of an activity one engages in influences an internalization process that enhances the quality of adolescents’ motivation. In an intervention comparing two different training approaches in soccer—a traditional approach and a game-based approach—no change was found in the value/usefulness variable in either approach (Haneishi et al., 2009).

1.2. Soccer Training

A traditional training approach in competitive sports and soccer training typically begins with a warm-up, followed by the coach demonstrating and instructing basic or advanced techniques, and then repeated practice of the skill through various drills. The coach teaches different tactics by showing and instructing the players on how and when to perform the newly acquired skill. Finally, a “game” is organized where players apply the technical and tactical skills practiced during drills (Martens, 2004).

An alternative to this traditional soccer training is a more game-based approach. Training starts with game sequences to understand how different tactics depend on acquiring specific techniques (Thorpe et al., 1984). The training structure in this game-based approach begins with a modified game. The coach then helps the player identify the key technical and tactical skills in the game, which the players practice to acquire these skills. This is followed by game sequences where these technical and tactical skills are applied (Haneishi et al., 2009). Game-based activities can be linked to situated learning/contextual learning and Nonlinear Pedagogy (Schmidt, 1975; Schmidt et al., 2018). This approach gives young players more control over their learning, minimizes interruptions from adult “experts,” and can increase their intrinsic motivation for soccer (Moy et al., 2016).

The SDT describes how a player can maintain motivation over time and how more intrinsic forms of motivation can be promoted. CET is a mini theory within the SDT that specifically addresses how social contexts, such as coaching style, influence motivation. An autonomy-supportive coaching style can maintain and enhance intrinsic motivation and perceived competence and teach adolescents to see the value of the activities they engage in. Back et al. (2022) indicated that for adolescents (aged 13.5–17 years) who experienced lower levels of autonomy support from their coach, this was the most significant risk factor for soccer dropout.

The autonomy-supportive coaching style involves interpersonal sentiments and behaviors trainers provide to identify, nurture, and develop players’ inner motivation (Reeve & Jang, 2006). Manninen and Yli-Piipari’s (2021) “Ten Practical Strategies to Motivate Students in Physical Education” are referenced to concretize the autonomy-supportive coach.

One important motivational strategy is the provision of meaningful rationales by the coach. The coach can reinforce and clarify the value of a planned learning exercise by giving meaningful explanations to the player. Reeve and Jang (2006) suggested that giving players the opportunities to make meaningful choices is crucial for promoting self-determination. This can be achieved through activities in which the player has opportunities for decision-making. Another important strategy is for the coach to encourage players to be supportive of each other, provide positive feedback, and collaborate toward a goal through a relatedness building practice. An autonomy-supportive coach will, with competence supportive design, also strive to provide each player with optimal learning challenges. Tailoring the challenges to each player increases their engagement and higher-level learning (Manninen & Yli-Piipari, 2021).

Feedback is a process of conveying information to the player about their performance, learning, and understanding (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). Feedback should also be constructive and provide instructions on how to improve.

There is a knowledge gap according to the knowledge of how traditional soccer schools affect very young players’ motivational factors such as interest/enjoyment, perceived competence and value/usefulness. In this study, we aimed to examine the changes in players’ interest/enjoyment, perceived competence, and value/usefulness through an 11-week soccer training program. We hypothesized that an 11-week soccer training program would enhance players’ interest/enjoyment, perceived competence, and value/usefulness related to soccer in the intervention group compared to a control group.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Based on power calculations using parameters from an earlier study (Berntzen & Lagestad, 2025) with expected differences between groups = 0.81, significance level α = 0.05, desired power = 0.80, and standard deviation SD = 1.70, we estimated that at least 38 participants per group were required (Cohen, 1988). A total of 175 children aged 9–12 years (M = 10.30, SD = 1.23) applied to join the soccer training program at a free soccer school.

Participants were recruited through announcements distributed to 12 local primary schools and community channels promoting a free soccer school program. The inclusion criteria were children aged 9–12 years that were eligible to participate, were physically able to engage in soccer training, and had parental consent. The exclusion criteria were medical conditions or injuries preventing participation in more than three soccer training sessions, lack of parental consent and absence at pre-test and/or post-test. For descriptive data of the participant’s gender, see Table 1, and for descriptive data of the participant’s age, see Table 2. According to the randomization procedure, all 175 applicants were assigned a unique ID number from 1 to 175. These numbers were placed in a black box, and an independent person (not involved in recruitment or data collection) randomly drew 100 numbers to form the intervention group (IG). The remaining 75 participants constituted the control group (CG). After the draw, participants were informed of their group assignment because the IG needed to attend weekly soccer school sessions during the intervention period, while the CG was scheduled to receive the same amount of training after the 11-week intervention was completed (on weekends). This procedure ensured that the allocation process was unbiased and concealed until the draw was finalized. Outcome assessors were not blinded to group allocation or timepoint because the intervention schedule was known to participants and organizers. This was unavoidable due to the nature of the intervention. With such a strategy, a representative and random sample was included in both groups according to age and gender. This is supported by the fact that independent t-tests showed that there were no significant differences between the intervention group and the control group according to both self-reported activity level at both pre-test (t = −0.4, p = 0.697) and post-test (t = −0.5, p = 0.627), but also according to gender (t = −0.8, p = 0.429) and age (t = −0.7, p = 0.690) there were no significant differences between the intervention group and the control group. Of the participants, 111 (71 from the IG and 40 from the CG) completed both the pre-test and post-test questionnaires, resulting in a response rate of 63%. Injuries, sickness, scheduling conflicts (the data collection took place on Saturdays), and other circumstances prevented some participants from taking part in data collection during both pre-test and post-test. Table 1 and Table 2 provide descriptive data for all participants. Both groups’ participation rate was recorded and analyzed. This study received approval from the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (SIKT) on 24 October 2023, under reference number 449551. The investigation adhered strictly to local legislation and institutional requirements to ensure ethical research conduct, and fulfilling the ethical standards for empirical research and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to the study’s commencement (when the children arrived at the soccer hall with their parents for the pre-test), the parents were given written informed consent for themselves and their children’s participation, which they signed. This consent process ensured that all participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits.

Table 1.

Descriptive data of the participants’ gender.

Table 2.

Descriptive data of the participants’ age.

The children were drawn from 12 different primary schools in a municipality with scattered settlements, and the majority had no prior acquaintance. The coaches at the soccer school and the other adults who contributed to the data collection were also unfamiliar with the children.

2.2. Training Procedures for the Intervention Group

According to the research question (to examine whether participation in a “traditional” soccer training program changed young players’ motivation for soccer), the program was not based upon Self-Determination Theory. The soccer program can be described as a traditional program designed to increase soccer skill levels among youth soccer players, consisting of practices related to individual skill exercises and small-sided games (Sørensen et al., 2024). The program was conducted by the organizer, who maintained control over the content and structure of the 11-week soccer training program. This study investigates whether such a soccer training program influenced motivational variables of players aged 9 to 12. In another article, we investigated the effect of the same program on players’ technical skills (Sørensen et al., 2024).

The intervention comprised 11 soccer training sessions in a three-month period during winter outside the players’ competitive season, from November 2023 to February 2024. Each session lasted 75 min. The intervention period of 11 weekly sessions over a four-month period could be argued to be short, but several comparable studies with similar or even shorter durations among children have documented significant psychosocial effects (Aelterman et al., 2014; Tessier et al., 2010; Aune et al., 2025; Belz et al., 2020; Ng-Knight et al., 2022; Gabana et al., 2022). Aelterman et al. (2014) found an effect of a three-month intervention grounded in SDT, and a study of Tessier et al. (2010) found effects on students’ psychological needs (relatedness) after an intervention of only 6 lessons of 1 h.

The exercise plan for these sessions was meticulously designed to ensure progressive skill development among the players. The primary objective of the soccer school was to enhance each player’s skill level, with a particular focus on ball mastery and decision-making abilities. Each training session was centered on a specific technical or tactical goal. Each of the 11 sessions started up with players engaging in basic skill-based activities as a warm-up. In sessions 1 to 5, the learning objective focused on managing 1 vs. 1 situations in soccer, with particular emphasis on how the defender’s positioning and spatial awareness on the field influence the attacker’s decision-making. Sessions 6 to 11 included exercises aimed at improving performance in 2 vs. 2 situations, as well as enhancing players’ ability to create and exploit 2 vs. 1 scenarios. The instructional focus during sessions 6 to 11 was on the attacking principle of overlap, aiming to enhance players’ tactical understanding and execution of coordinated offensive movements.

Each session was divided into three parts. In the first part, players engaged in individual skill exercises, either alone or with a teammate or opponent. The second part involved a progression of the initial skill, incorporating increased defensive pressure. The final part comprised various small-sided games, organized in different group sizes ranging from 4 vs. 4 to 7 vs. 7.

The training sessions were structured such that boys aged 9–10 years practiced together while boys aged 11–12 formed another group. A similar organizational structure was applied to the girls. The training sessions were conducted by three qualified soccer coaches, occasionally assisted by one or two additional coaches. To ensure intervention fidelity, all coaches participated in preparatory meetings before the program started, where they were briefed on the objectives, session structure, and instructional approach. Coaches received written guidelines detailing the content and progression of the 11 sessions. Throughout the intervention, adherence was monitored through direct observations by the authors in randomly selected sessions. Observations confirmed that coaches followed the planned structure (warm-up, skill progression, small-sided games) and employed non-controlling language, as intended.

Each session was designed to accommodate 50 players. Attendance was recorded at each session, and overall adherence was high, with most participants attending at least 8 of the 11 sessions. Deviations from the protocol were minimal and primarily related to occasional absences due to illness or other commitments. However, attendance often fell short by 10–20 players due to various reasons such as illness or commitment to other training activities. The coaches demonstrated personal interest in the players and employed a non-controlling language. Throughout the sessions, the coaches provided relevant individual feedback to the players regarding the learning objectives. The instructional approach involved the coaches explaining and often demonstrating the tasks at the beginning of each session or segment and allowing the players to apply the skills in practical soccer scenarios.

2.3. Questionnaire

The IMI (McAuley et al., 1989) was used to measure interest/enjoyment, perceived competence, and value/usefulness. The questionnaire measures seven aspects (subscales) of intrinsic motivation. We selected questions related to the subscale’s interest/enjoyment, perceived competence, and value/usefulness. The interest/enjoyment subscale is the primary self-report measure of intrinsic motivation. Perceived competence is theorized to positively predict both self-report and behavioral indicators of intrinsic motivation. The value/usefulness subscale is mostly used in internalization research, reflecting the idea that people internalize and self-regulate activities they perceive as useful or personally valuable.

The questionnaire consisted of 20 items: 7 items related to interest/enjoyment, 6 items related to perceived competence, and 7 items related to value/usefulness. Two example questions related to interest/enjoyment are “Playing soccer has been fun” and “While I was playing soccer, I was thinking how much I liked playing soccer”. Two example questions related to perceived competence are “I think I am quite good at playing soccer” and “I am satisfied with my performance in soccer” Two example questions related to value/usefulness are “I believe soccer is important to me” and “ I think that playing soccer is an important activity for me”. Participants responded to the questions on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). All subscales have acceptable reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.68 to 0.87 (McAuley et al., 1989).

The IMI has previously been used in various studies to assess different aspects of intrinsic motivation among children in soccer aged 9 to 15 years (Cresswell et al., 2003; Gjesdal et al., 2019a; Gjesdal et al., 2019b) and pupils in physical education aged 11 to 15 years (Williams & Gill, 1995). The items addressing value/usefulness and perceived competence were initially translated from English into Norwegian and subsequently back into English. This back-translation procedure, as recommended by Beaton et al. (2000), was employed to ensure that the items retained their original meaning and semantic equivalence. For interest/enjoyment, a Norwegian version of the scale developed by Waaler et al. (2022) was used in this study. Showing acceptable reliability, alpha 0.84.

2.4. Data Collection and Data Procedures

The pre-test and post-test were conducted on 5 November 2023, and 10 February 2024, respectively. All tests were conducted at the same place, in the same room, with the same leaders, and on the same day of the week. An 11-week training program was conducted for the intervention group between the pre-and post-tests. The six questions related to perceived competence were computed into a new variable after re-coding the question with the negative question form, dividing it with six. The same procedure was completed with the seven questions related to interest/enjoyment after re-coding the two questions with the negative question form and dividing it by seven. Also, the seven questions related to value/usefulness were computed into a new variable, dividing it by seven. Finally, three new variables that measured the change from pre-test to post-test within each of the three variables were constructed by carrying out pre-test minus post-test. We chose not to replace missing data with mean values or other imputation techniques based on the concern that such methods could introduce bias, especially in cases where post-test data were missing. Inputting such responses could distort the findings, because we have no empirical basis for estimating what participants would have answered. Given the nature of our data and study design, this strategy was the most conservative and transparent.

2.5. Data Analysis

The dependent variables did not meet the assumption of normality according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (p < 0.001). However, as noted by Vincent and Weir (2012), the F test in ANOVA is robust to violations of normality and heterogeneity of variance when sample sizes are adequate. Independent t-tests were used to examine baseline differences between the intervention group and control group according to self-reported activity level at both pre-test and post-test. To assess intervention effects, a 2 × 2 repeated measures ANOVA (2 × 2) with time (pre-test, post-test) as the within-subject factor and group (intervention, control) as the between-subject factor. When significant main or interaction effects were detected, pairwise comparisons were performed for pre-test vs. post-test within each group, and for intervention vs. control at each timepoint. For each comparison, we report mean difference, 95% confidence interval (CI), adjusted p-value (Holm–Bonferroni correction), and Cohen’s d as an effect size measure. Partial eta squared was used to interpret ANOVA effect sizes, where 0.01–0.06 indicates a small effect, 0.06–0.14 indicates a medium effect, and >0.14 indicates a large effect (Cohen, 1988). Furthermore, reliability analyses were conducted to measure Cronbach’s alpha and the internal consistency of the questions included in the variables: perceived competence, interest/enjoyment and value/usefulness. The analyses did not account for potential clustering effects by school, as randomization was performed at the individual level and the sample size within schools was small. This may introduce a minor risk of inflated Type I error if responses within schools were correlated. All analyses were performed using JASP (Version 0.095.4.0; JASP Team, 2024). Results are presented with descriptive statistics (mean, SD) and 95% CIs for all primary outcomes. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, with adjustments for multiple comparisons using Holm–Bonferroni.

3. Results

Table 3 presents the means, standard deviations, and reliability estimates for perceived competence, interest/enjoyment, and value/usefulness at T1 and T2 for the IG and CG. All variables showed good reliability estimates, with values > 0.70, except for the value for interest/enjoyment for the IG at pre-test, which showed 0.69.

Table 3.

Descriptive data of the participants scores at pre- and post, with reliability estimates.

Interest/enjoyment had the highest mean at T1 in the IG and CG, with a small decrease from T1 to T2 in both groups. Value/usefulness showed a small increase in the CG from pre-test to post-test, and a small decrease in the IG. Regarding perceived competence, the variable with the lowest mean, we observed a small decrease in the IG and a small increase in the CG. None of these changes were significant.

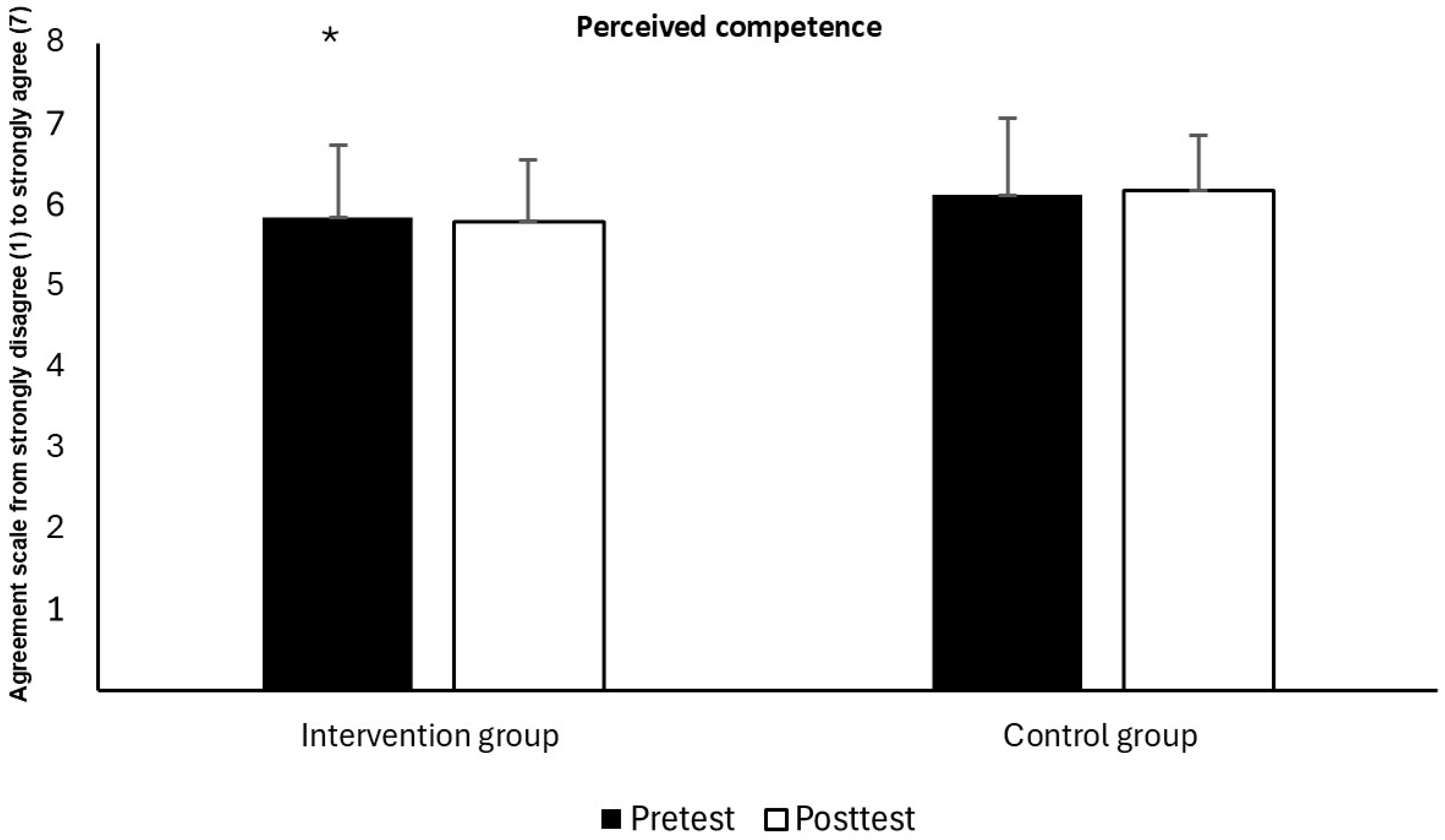

A Repeated measures ANOVA test showed no significant difference from pre-test to post-test in perceived competence (F = 0.0, p = 0.992, ηp2 < 0.01) (Figure 1). No significant interaction was observed for this parameter (F = 0.5, p = 0.503, ηp2 < 0.01), but a group effect was observed for this parameter (F = 5.2, p = 0.024, ηp2 = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.64, −0.05]). Pairwise comparisons (Holm-Bonferroni adjusted) showed no significant within-group changes (IG: Mean diff = 0.003, 95% CI [−0.277, 0.283], p = 0.983, d = 0.00; CG: Mean diff = 0.039, 95% CI [−0.233, 0.311], p = 0.778, d = 0.06). Between-group comparisons revealed small to moderate differences favoring the control group at pre-test (Mean diff = −0.295, 95% CI [−0.554, −0.037], p = 0.027, d = −0.36) and post-test (Mean diff = −0.331, 95% CI [−0.624, −0.039], p = 0.028, d = −0.39), although these did not remain significant after Holm-Bonferroni correction (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Perceived competence in the intervention and control groups at pre-test and post-test. * Significantly lower experience of perceived competence in the intervention group than the control at both pre-test and post-test.

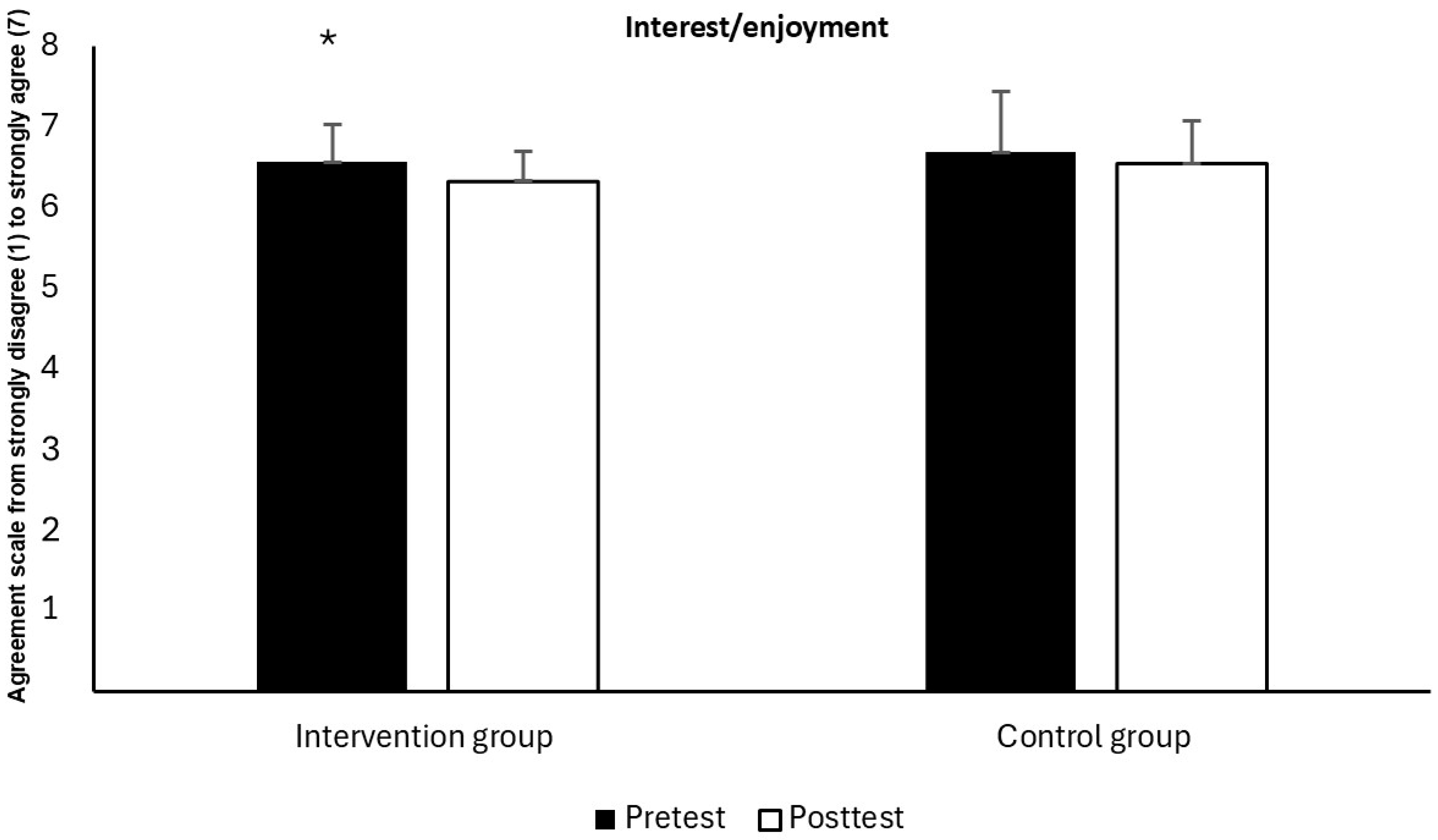

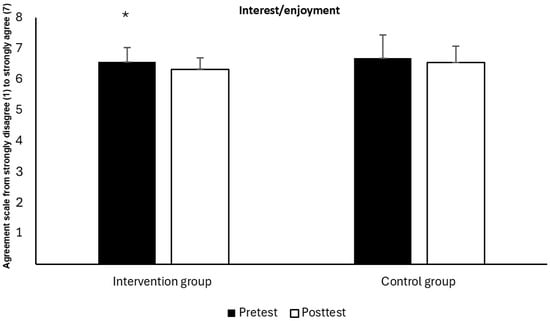

A Repeated measures ANOVA test showed a significant difference from pre-test to post-test in interest/enjoyment (F = 5.8, p = 0.018, ηp2 = 0.05) (Figure 2). No significant interaction (F = 0.1, p = 0.708, ηp2 < 0.01) and group (F = 3.8, p = 0.053, ηp2 = 0.04) effects were observed for this parameter. Pairwise comparisons showed small, non-significant decreases within both groups (IG: Mean diff = −0.151, 95% CI [−0.337, 0.034], p = 0.112, d = −0.26; CG: Mean diff = −0.070, 95% CI [−0.249, 0.109], p = 0.444, d = −0.16). Between-group differences were also non-significant (Pre-test: Mean diff = −0.103, 95% CI [−0.247, 0.041], p = 0.163, d = −0.22; Post-test: Mean diff = −0.184, 95% CI [−0.398, 0.029], p = 0.093, d = −0.30). Although the ANOVA indicated a main effect of time, post hoc tests did not confirm significant pairwise differences after adjustment (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interest/enjoyment in the intervention and control groups at pre-test and post-test. * Significantly lower experience of interest/enjoyment decrease in interest/enjoyment pre-test than at post-test in both the control group and the intervention group pre-test (p < 0.05).

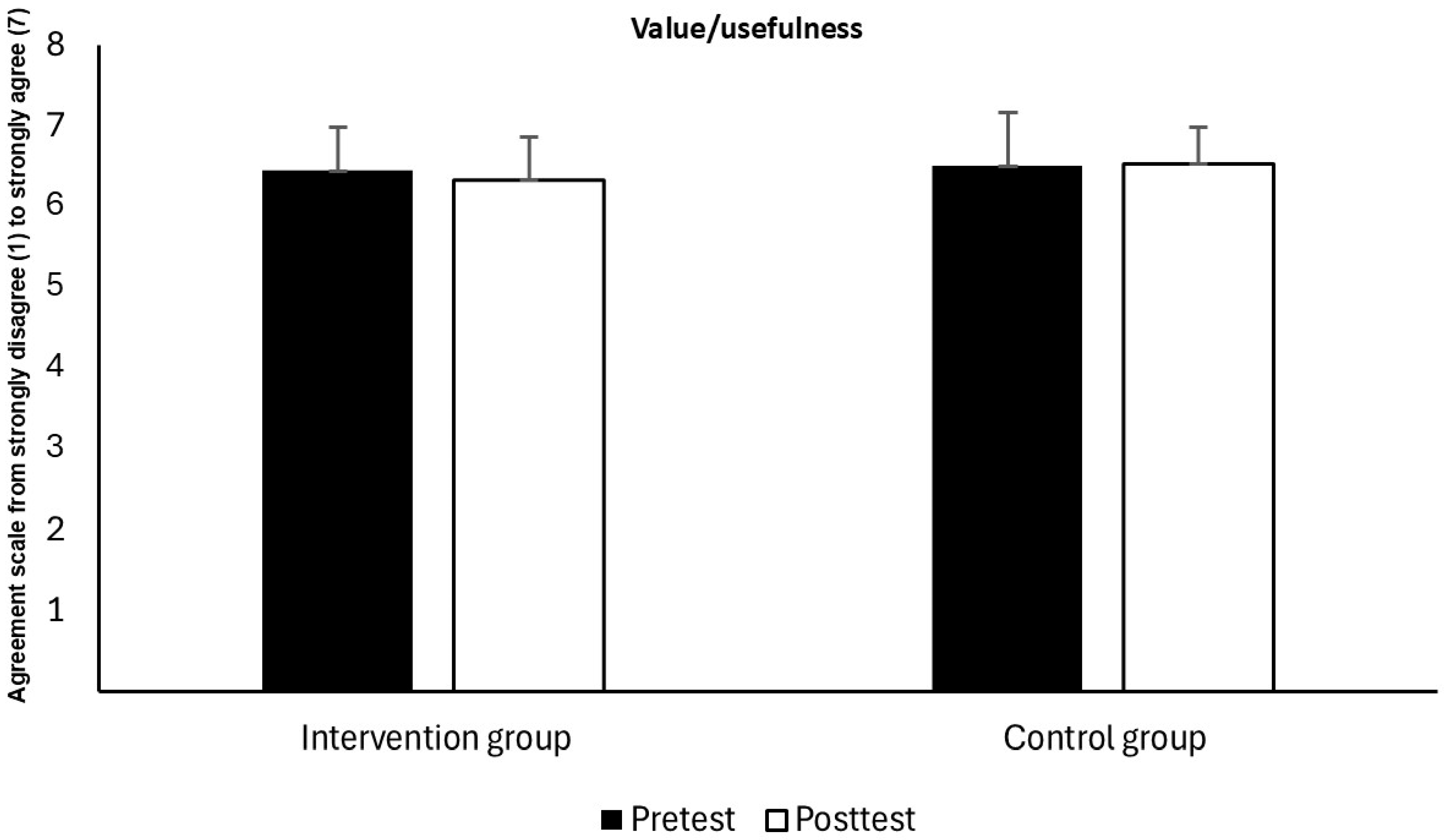

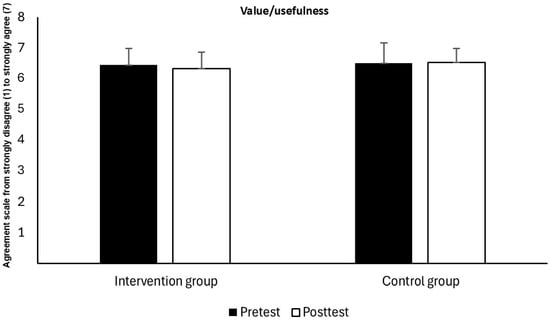

A Repeated measures ANOVA test showed no significant difference from pre-test to post-test in value/usefulness (F = 0.4, p = 0.494, ηp2 < 0.01) (Figure 3). No significant interaction (F = 1.0, p = 0.307, ηp2 < 0.01) and group (F = 1.7, p = 0.199, ηp2 = 0.02) effects were observed for this parameter. Pairwise comparisons confirmed no significant changes within groups (IG: Mean diff = −0.075, 95% CI [−0.263, 0.113], p = 0.436, d = −0.12; CG: Mean diff = 0.104, 95% CI [−0.096, 0.303], p = 0.311, d = 0.20) and no significant between-group differences at pre-test (Mean diff = 0.011, 95% CI [−0.171, 0.193], p = 0.904, d = 0.02) or post-test (Mean diff = −0.167, 95% CI [−0.372, 0.038], p = 0.113, d = −0.28). According to the question about the number of training sessions during a normal week with “physical activity where you are alone or with others for more than 30 min, and become out of breath or sweaty”, the two groups did not report significantly different activity levels (p > 0.05). The intervention group reported a Mean of 3.5 (SD = 1.6) in the pre-test and 4.2 (SD = 1.7) in the post-test, and the control group reported a Mean of 3.7 (SD = 2.1) at pre-test and 4 (SD = 1.7) at post-test.

Figure 3.

Value/usefulness in the intervention group and control group at pre-test and post-test.

4. Discussion

The findings of the study are related to the effect of participation in a soccer training program on players’ interest/enjoyment, perceived competence, and value/usefulness in soccer. The discussion interprets these findings through the lens of Self-Determination Theory (SDT), which posits that motivation is fostered when the basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are supported. In the present study, the IMI subscales of interest/enjoyment and perceived competence directly reflect intrinsic motivation and competence need satisfaction, while value/usefulness is consistent with internalization processes relevant to autonomous motivation (Aelterman et al., 2014; Tessier et al., 2010; Ntoumanis, 2001; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013; Stoa & Chu, 2023).

The first main (and primary) finding of the study is that participation in the 11-session soccer training program did not affect the children’s perceived competence, interest/enjoyment, or value/usefulness in a positive or negative direction compared to the CG. Interpreted within SDT, these null effects are consistent with an intervention that did not explicitly target autonomy-supportive coaching, competence-supportive task design, or relatedness-building structures. Another explanation is that the aim of this study was to examine whether participation in a “traditional” soccer training program changed young players’ motivation for soccer, and that the program was not explicitly designed according to SDT principles. Previous studies have shown that intervention programs based upon SDT have increased children’s motivation when coaching behaviors and learning climates are intentionally autonomy and competence supportive. Studies indicate that such effects emerge when SDT strategies are embedded Manninen and Yli-Piipari’s (2021), but not when programs are “traditional”, and helps to explain our null results despite a comparable duration. Considering the organization and implementation of the soccer training program, it appears that 11 weeks with only one training session per week were insufficient to influence the selected motivational factors among the players. This contrasted with Aelterman et al. (2014), who found effects after a similar duration when autonomy-supportive practices were central, and Tessier et al. (2010), who reported effects on students’ psychological needs after an even shorter intervention with targeted SDT-consistent pedagogy. Collectively, these studies emphasize that “dose” alone is not determinative, but that the quality of motivational climate—particularly autonomy-support—appears pivotal (Aelterman et al., 2014; Tessier et al., 2010; Belz et al., 2020; Ng-Knight et al., 2022; Gabana et al., 2022). However, the same program did not have a significant effect upon technical skills within the same period and with players (Sørensen et al., 2024), suggesting that both skill acquisition and motivational change may require either greater intensity or more intentional design than provided here.

The children’s pre-test scores on interest/enjoyment and value/usefulness were extremely high, and perceived competence was also high. These ceiling levels likely reflect that participants were highly motivated to join an extra soccer program, which limits the potential for further increases Previous studies on young soccer players using the IMI subscales of perceived competence (Cresswell et al., 2003; Gjesdal et al., 2019a) and interest/enjoyment (Cresswell et al., 2003; Gjesdal et al., 2019b) indicated relatively high scores, but lower than those obtained in the present study. Gjesdal used a 5-point Likert scale, which we converted to a 7-point Likert scale to enable us to compare their findings with ours. Regarding competence, Cresswell et al. (2003) obtained a score of 5.32, and Gjesdal et al. (2019a) obtained a score of 5.38. Regarding interest/enjoyment, Gjesdal et al. (2019b) obtained a score of 6.09, and Cresswell et al. (2003) reported a score of 6.01. In this study, the IG had a pre-test score of 5.85 on perceived competence and 6.55 on interest/enjoyment (Table 3), confirming a ceiling context that would render further increases unlikely and small declines detectable.

The fact that participation in the soccer program did not affect children’s perceived competence may also be explained by the Dunning–Kruger effect (Burson et al., 2006; Kruger & Dunning, 1999)—an argumentation supported by another study (Aune et al., 2025). A study by Aune et al. (2025) argues that their findings related to little effect in the intervention group according to self-reported efficacy and competence may reflect the Dunning–Kruger effect. This is when the participants in an intervention group have gained new skills and self-awareness and thereby become more critical and accurate in their self-assessments, resulting in lower self-reported competence. Aune et al. (2025) conclude that structured football interventions may inadvertently heighten children’s self-awareness of their limitations, leading to more modest self-evaluation of competence, which aligns with our pattern of findings.

Finally, while most between-group comparisons did not reach statistical significance, these findings should be interpreted with caution due to Type II error risk. Sample size and the presence of ceiling effects likely reduced statistical power to detect small or moderate changes, particularly when the intervention was not explicitly structurally aligned with SDT. The second main finding was a significant decrease in interest/enjoyment from pre-test to post-test in both the control group and the intervention group. However, the effect sizes are very small (Cohen, 1988), so the practical relevance is small. Within SDT, a small cross-group decline is coherent with both ceiling constraints, waning novelty in the absence of deliberate novelty-supportive design, and slow development of relatedness in newly formed groups. We will argue that an extremely high level of interest/enjoyment (6.55 on a 7-point scale) may be difficult to increase to an even higher level. The fact that the children were from 12 different primary schools and had no prior knowledge of each other or their coach, may also have affected the results. Starting an intervention with children who do not know each other and with coaches who do not know the children may be a challenge. The need for belonging pertains to the feeling of being connected to others, being accepted by others, and thereby feeling secure in social contexts, individually and in larger groups (Ntoumanis, 2001; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). Satisfying this need means that the individual feels a sense of familiarity and a genuine connection with others. Interpersonal relationships among players may foster mutual support, facilitate the provision of positive feedback, and promote collaboration toward shared goals. The coach also needs to build a relationship with the players. Showing interest in and curiosity in a player’s thoughts, background and interest is crucial.

Finally, in relation to the significant decrease in interest/enjoyment from pre-test to post-test, we will argue that the initial excitement might have been due to novelty, which naturally declines over time. Stoa and Chu (2023) argue that novelty is a potential basic psychological need within Self-determination theory. They highlight that novelty initially increases motivation, but becomes familiar over time, requiring strategies to maintain engagement. In conclusion, they argue that the largest drawback to novelty is its ability to become familiar, and this requires strategies to sustain engagement. If children expected more fun or different activities, unmet expectations could reduce enjoyment, which is consistent with novelty’s transient effect unless instructors deliberately curate continued subjective novelty. Taken together, the results indicate that duration alone (11 sessions) is insufficient to change motivation meaningfully without an SDT aligned climate. If the aim is to improve motivational factors related to SDT, organizers and coaches should receive training in autonomy-supportive behaviors (e.g., offering meaningful choice, acknowledging perspectives), competence-supportive design (optimal challenge with informational feedback), and relatedness-building practices (structured peer collaboration, coach–player rapport). Future interventions should extend relational onboarding to accelerate relatedness, embed novelty-supportive strategies throughout, avoid ceiling constraints by sampling across baseline motivation or tailoring content, and include direct measures of perceived need support to verify implementation fidelity.

The third main finding was a small group effect for perceived competence, with the control group scoring slightly higher than the intervention group both at pre-test and post-test. However, the effect sizes are also very small (Cohen, 1988), indicating limited practical relevance. This pattern reflects that both groups started with high perceived competence, creating a ceiling effect that makes further increases difficult. Furthermore, the intervention group’s inability to close this gap may be related to the Dunning–Kruger effect (Aune et al., 2025; Burson et al., 2006; Kruger & Dunning, 1999), pointing out that new skills and self-awareness lead to more critical and accurate self-assessments despite actual improvement. This can also be explained by the fact that the children in the intervention group were collected from 12 different primary schools and had no prior knowledge of each other or their coach. Within SDT, relatedness refers to feeling connected, accepted, and secure in social contexts (Strandkleiv, 2006). Starting with unfamiliar peers and coaches may affect relatedness negatively, limiting opportunities for mutual support, positive feedback, and collaborative goal pursuit. Within SDT, competence is a fundamental psychological need, but its development is influenced by relatedness and autonomy (Strandkleiv, 2006). The intervention group was composed of children from 12 different schools who did not know each other or their coach, which may have delayed the development of relatedness. Limited social connection can reduce opportunities for mutual support and positive feedback, both of which reinforce competence perceptions. Additionally, observing peers with superior skills during training may have negatively influenced self-assessment. These dynamics highlight that competence support cannot be isolated from relational and autonomy-supportive processes.

The SDT and the mini theories (Basic Psychological Needs Theory; Organismic Integration Theory) can explain why perceived competence, value/usefulness, and interest/enjoyment are critical for sustained motivation. Competence fosters intrinsic motivation, while value/usefulness supports internalization, and interest/enjoyment reflects intrinsic motivation. High levels of these variables are positive predictors of long-term participation (Vallerand et al., 1987).

Encouragingly, our findings show that value/usefulness and perceived competence remained high across the intervention, which is not guaranteed in new training contexts. Maintaining these levels likely reflects coaching behaviors that were at least moderately supportive. Although the intervention followed a structured, instruction-based approach with limited autonomy in exercise selection, two-thirds of the sessions included play activities requiring player decision-making. Future interventions could adopt game-based approaches grounded in Nonlinear Pedagogy (Haneishi et al., 2009; Moy et al., 2016), which enhance autonomy, decision-making, and technical performance (Práxedes et al., 2019).

Coaches should also apply SDT-informed strategies—providing meaningful rationales, fostering peer support, offering positive feedback, and encouraging collaboration (Manninen & Yli-Piipari, 2021). Observations indicated that coaches demonstrated personal interest, used non-controlling language, and provided relevant feedback during the intervention, which likely helped maintain high motivation. However, more systematic autonomy-supportive practices could further strengthen competence and enjoyment.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

One strength of this study is that it was based on an experiment with a randomized IG and a CG. Statistical analyses showed that there were no significant differences between the intervention group and the control group according to both self-reported activity level, gender and age. Furthermore, the sample size is sufficient for an intervention study for 11 weeks, using the same test procedures and place, and the same test leaders with very low dropout rate. However, the study has some limitations. The sensitivity of the chosen skill test could be a limitation. The young age of the participants (9–12 years) may have affected the reliability of the results. One may question whether children at that age are able to interpret the questions and response options well, and whether they interpret them the same way. Furthermore, making children “perform” in groups with other children they did not know could also affect the results. Several comparable studies with similar or even shorter durations have documented significant psychosocial effects (Aelterman et al., 2014; Tessier et al., 2010; Aune et al., 2025; Belz et al., 2020; Ng-Knight et al., 2022; Gabana et al., 2022). However, sustained change may require longer intervention periods, and future studies should include a longer intervention period with more training sessions a week and in total—as indicated by Manninen et al. (2022). Even if power calculations indicated that there are enough participants per group, the small control group reduces the ability to identify true differences and increases the possibility for potential risk of Type II errors. Consequently, non-significant results do not necessarily imply the absence of an effect, and future studies with larger and more balanced samples that control for novelty effects are recommended to confirm these findings. Another limitation of this study is that outcome assessors were not blinded to group allocation or timepoint. This could introduce a risk of bias. However, the potential impact is considered minimal because all outcomes were self-reported using standardized questionnaires, reducing the influence of assessor expectations. Additionally, potential clustering effects were not accounted for in the analysis. Participants were recruited from multiple schools, and although randomization was performed at the individual level, responses within schools may have been correlated. This could slightly increase the risk of Type I errors. Future studies should consider multilevel modeling to address clustering. The study also lacked follow-up measurements beyond the immediate post-test, limiting conclusions about the sustainability of the intervention effects. Future research should include long-term follow-up assessments to evaluate whether observed changes persist over time and address ceiling effects. Furthermore, even if statistical analyses showed that the intervention group and the control group did not report significantly different activity levels in the period before the intervention, it is a limitation that we have no control over what those two groups did regarding soccer training or physical activity within the intervention period. Future studies should include such measures.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study found that participation in an 11-session soccer training program did not significantly affect the children’s perceived competence, interest/enjoyment, and value/usefulness in a positive or negative direction compared to a control group. Both groups maintained very high levels on these variables from pre-test to post-test, suggesting a ceiling effect and an autonomy-supportive context that helped sustain motivation. These findings indicate that motivational change requires more than additional training sessions; it depends on creating environments that support autonomy, competence, and relatedness, as outlined in Self-Determination Theory. For practice, coaches should integrate SDT principles—such as providing meaningful choices, fostering social connection, and offering informational feedback—to enhance intrinsic motivation and promote long-term participation in soccer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.L., K.S. and A.S.; methodology, P.L. and S.O.U.; software, P.L. and S.O.U.; validation, K.S., P.L., A.S. and S.O.U.; formal analysis, P.L. and S.O.U.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S. and P.L.; writing—review and editing, K.S., P.L., A.S. and S.O.U.; visualization, P.L. and S.O.U.; project administration, P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (protocol code 649454 and date of approval is 10 November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

List of Abbreviations

CG, control group; IG, Intervention group; IMI, Intrinsic Motivation Inventory; SDT, self-determination theory; SPSS, Statistical Package for Social Sciences.

References

- Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Van den Berghe, L., De Meyer, J., & Haerens, L. (2014). Fostering a need-supportive teaching style: Intervention effects on physical education teachers’ beliefs and teaching behaviors. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 36, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, T., Knutsen, J. M., Douglass, B., Pedersen, P. H., & Lagestad, P. (2025). The paradox of progress: Structured football, self-efficacy, and the Dunning–Kruger effect—A randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1674900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Back, J., Stenling, A., Solstad, B. E., Svedberg, P., Johnson, U., Ntoumanis, N., Gustafsson, H., & Ivarsson, A. (2022). Psychosocial predictors of drop-out from organised sport: A prospective study in adolescent soccer. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 16585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakken, A. (2019). Idrettens posisjon i ungdomstida: Hvem deltar og hvem slutter i ungdomsidretten? [The role of sports in adolescence: Who participates and who quits youth sports?]. NOVA Rapport 2/2019. Oslo Metropolitan University. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12199/1298 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Balish, S. M., McLaren, C., Rainham, D., & Blanchard, C. (2014). Correlates of youth sport attrition: A review and future directions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 15, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanger, M., Sabiston, C. M., Barnett, T. A., O’Loughlin, E., Ward, S., Contreras, G., & O’Loughlin, J. (2015). Number of years and participation in some, but not all, types of physical activity during adolescence predicts levels of physical activity in adulthood: Results from a 13-year study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, J., Kleinert, J., & Anderten, M. (2020). One shot—No hit? Evaluation of a stress-prevention workshop for adolescent soccer players in a randomized controlled trial. The Sport Psychologist, 34(2), 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntzen, I., & Lagestad, P. (2025). Effects of coaches’ feedback on psychological outcomes in youth football: An intervention study. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 7, 1527543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burson, K. A., Larrick, R. P., & Klayman, J. (2006). Skilled or unskilled, but still unaware of it: How perceptions of difficulty drive miscalibration in relative comparisons. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(1), 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W., Zhang, Z. M., Cheng, W., Yang, C., Diao, L., & Liu, W. (2018). Associations of leisure-time physical activity with cardiovascular mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 44 prospective cohort studies. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 25, 1864–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, S., Hodge, K., & Kidman, L. (2003). Intrinsic motivation in youth sport: Goal orientation and motivational climate. New Zealand Physical Education, 36, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R. M., Young, J. A., Harvey, J. T., Charity, M. J., & Payne, W. R. (2013). A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabana, N. T., Wong, Y. J., D’Addario, A., & Chow, G. M. (2022). The Athlete Gratitude Group (TAGG): Effects of coach participation in a positive psychology intervention with youth athletes. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 34(2), 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjesdal, S., Haug, E. M., & Ommundsen, Y. (2019a). A conditional process analysis of the coach-created mastery climate, task goal orientation, and competence satisfaction in youth soccer: The moderating role of controlling coach behavior. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjesdal, S., Stenling, A., Solstad, B. E., & Ommundsen, Y. (2019b). A study of coach–team perceptual distance concerning the coach-created motivational climate in youth sport. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 29, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneishi, K., Griffin, L., Seigel, D., & Shelton, C. (2009). Effects of games approach on female soccer players. In TGfU… simply good pedagogy: Understanding a complex challenge. PHE Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjønniksen, L., Anderssen, N., & Wold, B. (2009). Organized youth sport as a predictor of physical activity in adulthood. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 19, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagestad, P., & Mehus, I. (2018). The importance of adolescents’ participation in organized sport according to VO2 peak: A longitudinal study. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 89, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagestad, P., Mikalsen, H., Ingulfsvann, L. S., Lyngstad, I., & Sandvik, C. (2019). Associations of participation in organized sport and self-organized physical activity in relation to physical activity level among adolescents. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manninen, M., Dishman, R., Hwang, Y., Magrum, E., Deng, Y., & Yli-Piipari, S. (2022). Self-determination theory-based instructional interventions and motivational regulations in organized physical activity: A systematic review and multivariate meta-analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 62, 102248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manninen, M., & Yli-Piipari, S. (2021). Ten practical strategies to motivate students in physical education: Psychological need-support approach. Strategies, 34(2), 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, R. J. (2004). Successful coaching (5th ed.). Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- McAuley, E., Duncan, T., & Tammen, V. V. (1989). Psychometric properties of the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory in a competitive sport setting: A confirmatory factor analysis. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 60, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moy, B., Renshaw, I., & Davids, K. (2016). The impact of nonlinear pedagogy on physical education teacher education students’ intrinsic motivation. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 21, 517–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møllerløkken, N. E., Lorås, H., & Pedersen, A. V. (2015). A systematic review and meta-analysis of dropout rates in youth soccer. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 121, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng-Knight, T., Gilligan-Lee, K. A., Massonnié, J., Gaspard, H., Gooch, D., Querstret, D., & Johnstone, N. (2022). Does taekwondo improve children’s self-regulation? If so, how? A randomized field experiment. Developmental Psychology, 58(3), 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N. (2001). A self-determination approach to the understanding of motivation in physical education. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 71, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Práxedes, A., Del Villar Álvarez, F., Moreno, A., Gil-Arias, A., & Davids, K. (2019). Effects of a nonlinear pedagogy intervention programme on the emergent tactical behaviours of youth footballers. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J., & Jang, H. (2006). What teachers say and do to support students’ autonomy during a learning activity. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2007). Active human nature: Self-determination theory and the promotion and the maintenance of sport, exercise, and health. In M. S. Hagger, & N. L. D. Chatzisarantis (Eds.), Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in exercise and sport (pp. 1–19). Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in development, and wellness. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R. A. (1975). A schema theory of discrete motor skill learning. Psychological Review, 82, 225–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R. A., Lee, T. D., Winstein, C., Wulf, G., & Zelaznik, H. N. (2018). Motor control and learning: A behavioral emphasis. Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, A., Dalen, T., & Lagestad, P. (2024). Effects of a short-term soccer training intervention on skill course performance in youth players: A randomized study. Sports, 12, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoa, R., & Chu, T. L. (2023). An argument for implementing and testing novelty in the classroom. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 9(1), 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandkleiv, O. I. (2006). Motivasjon i praksis: Håndbok for lærere [Motivation in practice: Handbook for teachers]. Elevsiden DA. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H., & Chen, A. (2010). A pedagogical understanding of the self-determination theory in physical education. Quest, 62, 364–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, V. A., & Crane, J. R. (2018). A systematic review of drop-out from organized soccer among children and adolescents. In J. O’Gorman (Ed.), Junior and youth grassroots football culture (pp. 64–89). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier, D., Sarrazin, P., & Ntoumanis, N. (2010). The effect of an intervention to improve newly qualified teachers’ interpersonal style, students’ motivation and psychological need satisfaction in sport-based physical education. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 35(4), 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, R., Bunker, D., & Almond, L. (1984). A change in focus for the teaching of games. In Sport pedagogy: Olympic scientific congress proceedings (pp. 163–169). Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- Ulstad, S. O. (2021). Kroppsøving sett i lys av selvbestemmelsesteorien [Physical education in schools viewed through the lens of self-determination theory]. In K. Skjesol, & I. Lyngstad (Eds.), Kroppsøving, læreren og eleven (pp. 117–132). Fagbokforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Ungdata. (2020). Ungdom og idrett i Norge [Youth and sports in Norway]. Nova. Available online: https://www.ungdata.no/ungdom-og-idrett/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Vallerand, R. J., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). Intrinsic motivation in sport. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 15, 389–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 23, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, W., & Weir, J. P. (2012). Statistics in kinesiology (4th ed.). Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- Waaler, R., Halvari, H., Skjesol, K., & Ulstad, S. O. (2022). Students’ personal desire for excitement and teachers’ autonomy support in outdoor activity: Links to passion, intrinsic motivation, and effort. Journal for Research in Arts and Sports Education, 6(2), 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L., & Gill, D. L. (1995). The role of perceived competence in the motivation of physical activity. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).