Abstract

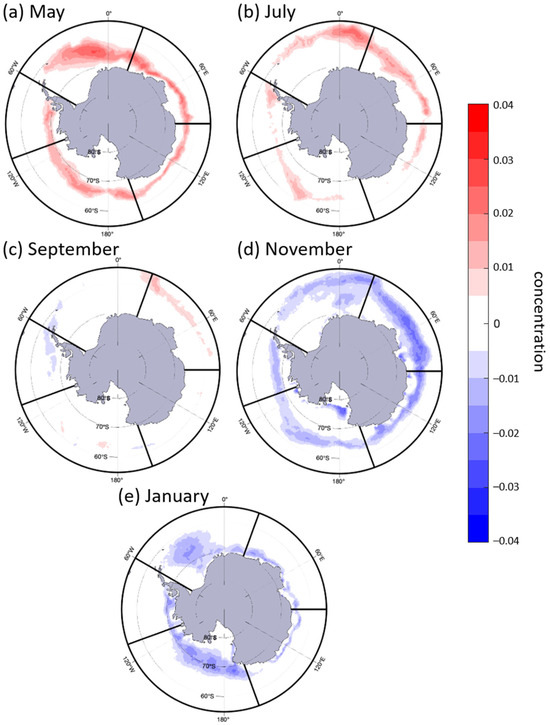

Convection associated with the leading mode of subseasonal variability of the tropical atmosphere, the Madden–Julian Oscillation (MJO), can excite Rossby wave trains that extend well into the extratropics and allow the MJO to modulate many components of the Earth system. To improve our understanding of teleconnections between the MJO and Antarctic sea ice, composite anomalies of daily change in sea ice concentration (ΔSIC) from 1989 to 2019 were binned by phase 0–20 days after an active MJO and compared to anomalies of surface air temperature, the meridional component of surface wind, and sea-level pressure. In May, ΔSIC anomalies were strongest in the Indian Ocean (IO) sector, 16 days after phase 8. There, a wavenumber-three pattern in sea-level pressure anomalies associated with the MJO resulted in anomalously poleward winds and warmer temperatures over the central and eastern IO that were collocated with anomalously negative ΔSIC. Furthermore, anomalously equatorward winds and colder temperatures in the western IO were collocated with anomalously positive ΔSIC. In July, ΔSIC anomalies were strongest in the Weddell Sea (WS) sector nine days after an active MJO in phase 2. There, a wavenumber-three pattern in sea-level pressure anomalies resulted in anomalously poleward winds and warmer temperatures over the western and central WS that were collocated with negative ΔSIC anomalies; anomalously equatorward winds and colder temperatures over the eastern WS were collocated with positive ΔSIC anomalies. In September, the largest ΔSIC anomalies were observed in the IO and WS sectors six days after an active MJO in phase 8. No meaningful modulation of sea ice anomalies was found after an active MJO in November or January. These results extend our understanding of teleconnections between the MJO and Antarctic sea ice on the subseasonal time scale.

1. Introduction

Antarctic sea ice responds to forces from multiple sources, including wind stress and surface air temperature (SAT) [1,2,3,4,5,6], precipitation [7,8,9,10], ocean temperature [11,12,13,14], ocean circulation [15,16], surface ocean waves [17,18], and air–sea feedbacks [19,20]. Of these, wind and SAT are thought to be among the most important drivers of sea ice variability [4,21,22,23,24]. Antarctic sea ice growth and decay are most focused in the marginal ice zone around the continent [25,26]. In this circumpolar zone, which can be many hundreds of kilometers wide, sea ice concentration (SIC) can range from 15 to 80% [27]. Here, the meridional component of surface winds can drive either ice formation or decline [28,29], often via heat transfer [30]. When surface winds are equatorward, they typically advect colder, drier air from the continent that tends to promote sea ice formation, and when they are poleward, they typically advect relatively warmer, moist air from lower latitudes that tends to promote sea ice decline [31]. These winds and temperatures are known to vary across wide time scales, from hours to centuries [6,32,33,34,35,36], but comparatively less is known about their variability on the subseasonal (30–60 day) time scale or how they affect sea ice on that scale.

The leading mode of tropical atmospheric variability on the subseasonal time scale is the Madden–Julian Oscillation (MJO) [37,38]. The MJO is an approximately wavenumber-one equatorial oscillation characterized by a broad zone of enhanced convective activity and ascent that progresses eastward, flanked on either side by suppressed convective activity and descent [39,40,41]. MJO convection tends to be strongest in the Eastern Hemisphere [42], while the anomalous ascent and descent tend to circumnavigate the equator on subseasonal time scales [43,44]. One of the consequential features of the oscillation is its generation of Rossby waves that propagate poleward in both hemispheres [45,46], allowing the MJO to interact significantly with almost every component of the Earth system [34,47,48]. This teleconnection process can be complicated by wave breaking and nonlinear extratropical responses [34,49,50], yet in the Northern Hemisphere, sea ice has been observed to respond to both wind and temperature anomalies driven by the MJO [51,52]. Less is known about possible MJO modulation of Antarctic sea ice, partly because less is known about MJO teleconnections, in general, in the Southern Hemisphere [53].

Much of the work to date on the variability of Antarctic sea ice has focused on the monthly, seasonal, and interannual time scales [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61], which is perhaps not surprising given that the most pronounced variability of Antarctic sea ice occurs as it completes its annual cycle [62]. On that time scale, at its September maximum, Antarctic sea ice covers approximately 18–19 million km2, but it reduces to one-sixth of that area in February [63] in an uneven cycle of formation and decline in the marginal ice zone [28,64] driven by seasonal variability in temperature and wind.

Despite evidence that Antarctic temperatures and winds are modulated subseasonally by the MJO [65,66,67,68,69], our understanding of the MJO’s modulation of Antarctic sea ice is incomplete. One of the first to investigate the MJO–Antarctic sea ice relationship [70] found links between sea ice concentration and subseasonal variability of 500 hPa geopotential height during two periods: when sea ice was growing (May–June) and when it was near its maximum extent (August–October). They found that anomalies in 500 hPa height tend to lead the sea ice by approximately five days, but concluded that changes in sea ice were largely the result of internal Antarctic variability and not forcing from the tropical MJO. More recently, subseasonal variability of Antarctic sea ice extent (SIE) was found to be most coherent with variability of atmospheric geopotential height in the 20–40-day time frame [71], but that relationship was thought to be more associated with the Pacific–South American pattern than the tropical MJO. Only recently has stronger evidence of a link between the MJO and Antarctic sea ice begun to emerge. For example, ref. [72] partially connected the record low SIE in December 2016 to the MJO, noting that MJO convection over the tropical Indian and western Pacific Oceans weakened a wavenumber-three circulation over Antarctica that reduced SIE in the Indian Ocean, Ross Sea, and Bellingshausen and Amundsen (B&A) Seas sectors (see Figure 1 for sector definitions). Ref. [73] found that when MJO convection is over the Indian Ocean (phase 2), SIE increases over the Mawson-Dumont d’Urville Seas and decreases over the Ross Sea, while when MJO convection is over the Maritime Continent (phase 4), SIE increases in the Ross and Weddell Seas and decreases in the Antarctic Peninsula. They attributed these changes in SIE to temperature advection due to anomalous meridional winds driven by a response to Rossby wave propagation into the Southern Hemisphere during the Austral winter.

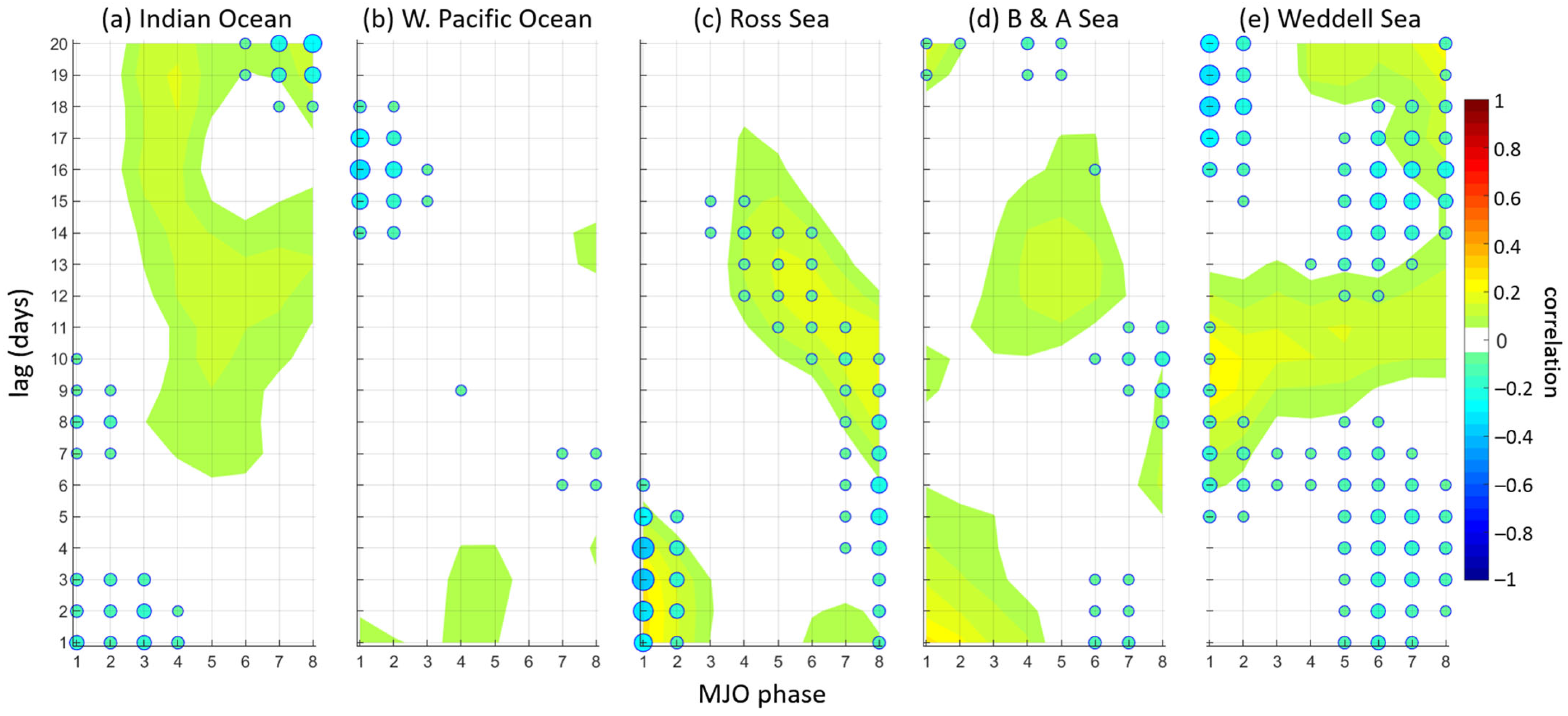

Figure 1.

Sea ice sectors in the Southern Hemisphere, following [74].

Even with these findings, there remain gaps in our understanding of subseasonal modulation of Antarctic sea ice by the MJO, particularly regarding possible regionality and temporal variability. This uncertainty was highlighted by [29], who found—somewhat in contrast with earlier results—that the greatest MJO-linked variability in sea ice was in the spring ice-melt season, mostly in the Weddell Sea. In our study, we build upon and extend previous work on subseasonal modulation of Antarctic sea ice by the MJO in two key ways. First, we consider anomalous daily change in gridded SIC (instead of basin-averaged SIE) over a range of daily time lags, from 0 to 20 days after an active MJO; and second, we consider daily changes in SIC and the corresponding atmospheric wind and temperature forces separated in the five Antarctic sectors defined by [74] (the Indian Ocean sector (20–90° E), the western Pacific Ocean sector (90–160° E), the Ross Sea sector (160° E–130° W), the Bellingshausen and Amundsen Seas (B&A) sector (130–60° W), and the Weddell Sea sector (60° W–20° E) [54,74,75]; see Figure 1). The remainder of this article is as follows: data and methods are presented in the next section, followed by results in Section 3, discussion in Section 4, and Conclusions in Section 5.

2. Data and Methods

The analyses in this study are based on three publicly available datasets. First, the daily change in Antarctic SIC was calculated using the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) sea ice index version 3 [76]. These data are derived from passive microwave measurements taken by polar-orbiting satellites and represent the fraction (from 0.0 to 1.0) of a pixel covered in ice [77]; they are available on a 25 km × 25 km grid at daily temporal resolution. SIC was analyzed over the years 1989–2019, starting in 1989 due to missing data in the record from 1979 to 1988 and ending in 2019 to avoid inhomogeneities associated with the recent rapid decline in Antarctic sea ice starting in 2020 [13,78]. Daily change in SIC (∆SIC) was calculated at each grid point using the following:

where SIC(dayn) is the daily SIC for day n and SIC(dayn−1) is the concentration for the previous day. Anomalous ∆SIC for each grid point was calculated by subtracting the 30-day running mean. Extreme changes in ∆SIC were defined as values at least two standard deviations from the mean SIC for the respective month. To test the statistical significance of extreme changes in ∆SIC, a two-tailed, unequal variance, independent two-sample t-test (a Welch’s t-test) was performed at every grid point for every MJO phase, following [51]. Anomalies statistically significant at the 95th percentile (with a p-value < 0.05) were retained.

∆SIC = SIC(dayn) − SIC(dayn−1)

Second, MJO phase and amplitude were defined using the daily real-time multivariate MJO (RMM) index [79]. The RMM index categorizes the MJO in one of eight phases, each corresponding to the broad location of an MJO-enhanced equatorial convective signal. The index is created by projecting anomalies of outgoing longwave radiation and zonal 850 and 200 hPa winds between 15° N and 15° S onto the two leading principal components (RMM1 and RMM2) from an empirical orthogonal analysis [80]. It describes up to 30% of the subseasonal variability of the tropical atmosphere [79,81] while capturing the quasi-cyclic MJO eastward progression, from phase 1 to 8 and back to phase 1 again [44,82]. Daily ∆SIC anomalies were binned by phase of the active MJO, and an active MJO was defined as one with an amplitude ([RMM12 + RMM22]½) greater than 1.0. Anomalies of ∆SIC were examined 0–20 days after an active MJO to allow for time lags associated with the variability of Rossby wave forcing from the tropical source region [83].

Third, the relationship between the atmospheric environment and Antarctic sea ice was examined via daily anomalies of the 10 m meridional wind component (v-wind), 2 m surface air temperature (SAT), and mean sea-level pressure (MSLP) from the ERA5 reanalysis [84] from 1989 to 2019. Daily anomalies of the v-wind, SAT, and MSLP at grid spacing of 0.25° × 0.25° at 0000 UTC were calculated using the method described above for sea ice, and those anomalies were then binned by phase at 0–20-day time lags after an active MJO. The anomalies were tested for statistical significance using a Welch’s t-test similar to the ΔSIC anomalies. The strength of the agreement between the anomalies of v-wind, SAT, and ∆SIC by MJO phase, sector, and time lag was quantified in Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients. Correlation coefficients (r) were calculated between ∆SIC and v-wind and SAT anomalies at every grid point in each sector for each MJO phase and month after projecting the v-wind and SAT reanalysis data from the ERA5 grid onto the ∆SIC grid. The correlations were used to determine in which phase, sector, and time lag the MJO modulation was strongest. In this study, we define correlation strength as follows: strong |r| > 0.6, moderate 0.3 > |r| > 0.6, and weak |r| < 0.3, following [85]. It is important to note that due to the large number of paired gridded observations (n > 500) used to calculate the correlations in each sector, correlation coefficients larger than 0.146 are statistically significant beyond 99.9% (p < 0.001).

3. Results

3.1. Annual Cycle of Antarctic Sea Ice

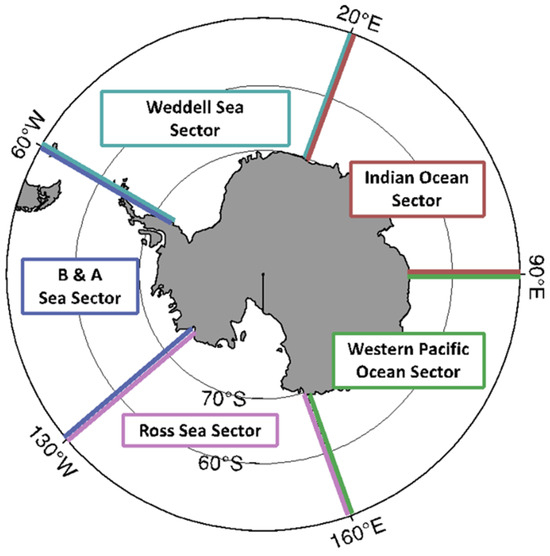

There is a pronounced annual cycle in the extent of total Antarctic sea ice [59], with a maximum in total SIE in September and a minimum in total SIE in February. The tendency is for sea ice growth in May and July, while November and January are dominated by ice decline. In September, both ice growth and decline are present, and sea ice extent is at a minimum in February–March. In this study, potential MJO modulation of sea ice was investigated in all months of the year. Results from five months (May, July, September, November, and January) are presented here because they represent the annual cycle and feature a marginal ice zone sufficiently broad to respond to force from the MJO on the synoptic and larger scales [86,87]. The marginal ice zone is located close to the continent in May (Figure 2a), extends equatorward into the Southern Ocean in July, September, and November (Figure 2b–d), and then retreats again to a position close to the continent in January (Figure 2e). The magnitude of average daily ∆SIC is larger in May and November and smaller in September, and in September, on average, sea ice concentrations decline in the B&A Sea and western Weddell Sea sectors and increase in the eastern Weddell Sea and Indian Ocean sectors (Figure 2c). As will be shown below, the Indian Ocean and Weddell Sea sectors particularly stand out as having the most frequent and largest correlations between sea ice and wind and temperature. This is perhaps because the marginal ice zone is widest over the Indian Ocean and Weddell Sea sectors from May and November (Figure 2a–c), and also because the mean daily ∆SIC is largest in those two sectors during the year. From February to March, the mean ∆SIC is close to zero, and the marginal ice zone is confined to areas adjacent to the continent (not shown).

Figure 2.

Average daily ∆SIC (in units of concentration) from 1989 to 2019, for (a) May, (b) July, (c) September, (d) November, and (e) January. The SIC is derived from the NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center sea ice index version 3 [76]. Sector names are given in Figure 1.

3.2. The MJO and Antarctic Sea Ice

3.2.1. Identifying MJO Phases and Time Lags with the Strongest Relationship

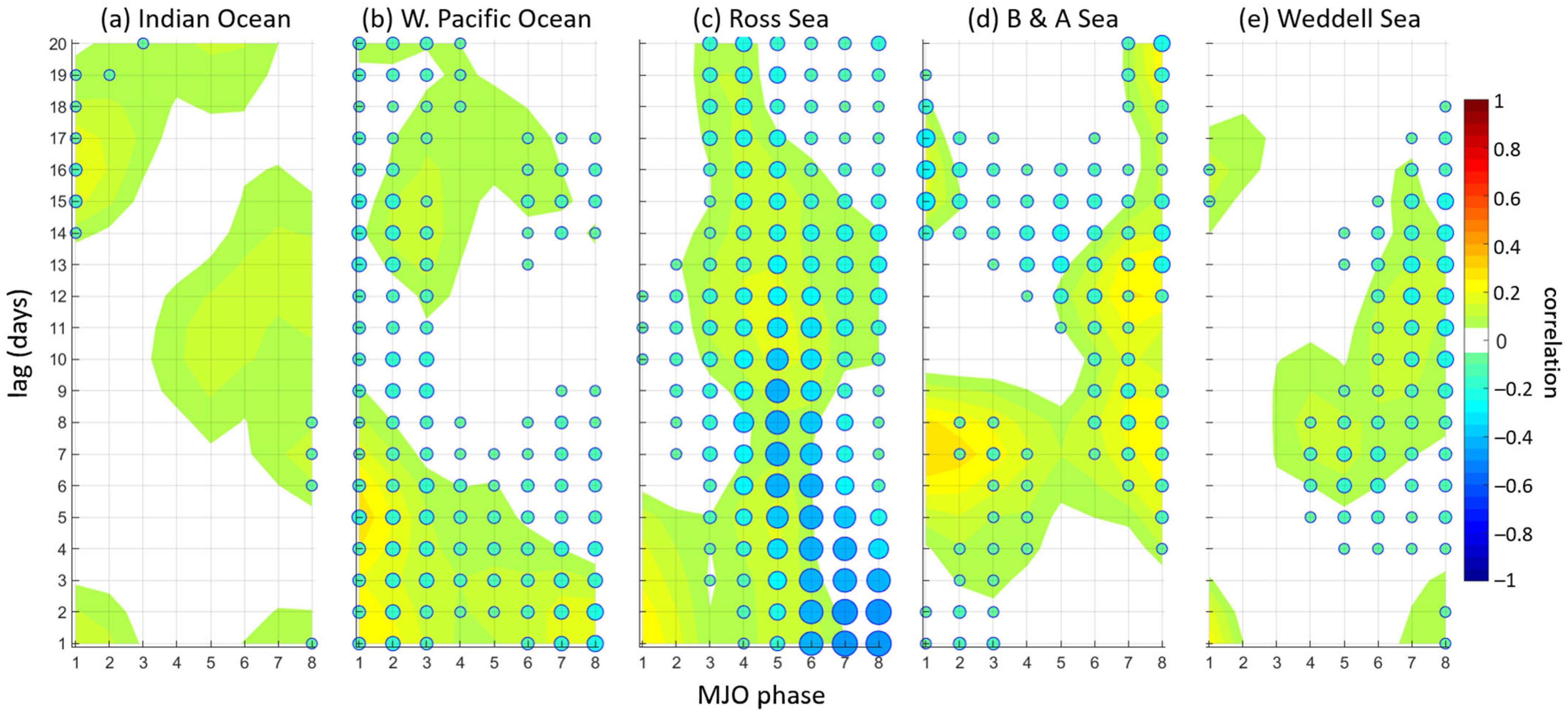

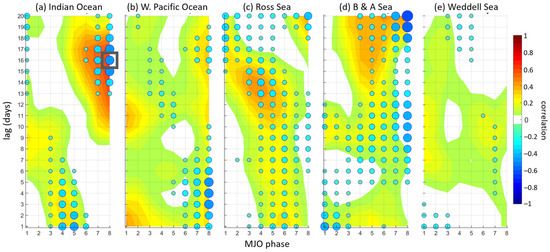

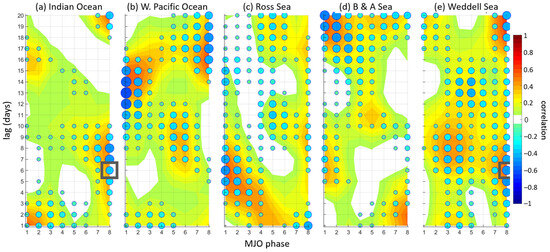

Correlation coefficients between ∆SIC and two atmospheric variables, the meridional component of the 10 m wind (v-wind) and 2 m temperature (SAT), were calculated for all months. As discussed earlier, results for five months (May, July, September, November, and January) are presented here as representative of the period April–January. Positive correlations between ∆SIC and v-wind anomalies indicate a relationship where either anomalous equatorward surface wind is co-located with positive ∆SIC anomalies or anomalous poleward surface wind is co-located with negative ∆SIC anomalies. Negative correlations between ∆SIC and surface temperature anomalies indicate either anomalously cold air co-located with positive ∆SIC anomalies or anomalously warm air co-located with negative ∆SIC anomalies. Note that in those Figures, both the size and shading of the circles indicate the magnitude of the field correlations between anomalous temperature and ∆SIC. For clarity, only positive correlations between ∆SIC and v-wind and negative correlations between ∆SIC and surface temperature are displayed. It is important to note that for some phases and time lags, one—but not both—of either temperature or wind is moderately or strongly correlated with SIC. However, here we constrain our analysis to highlight the sector, phase, and time lag with the strongest correlation between ∆SIC and both v-wind and SAT in each month.

3.2.2. MJO Modulation of Sea Ice in May

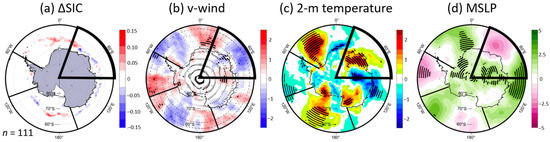

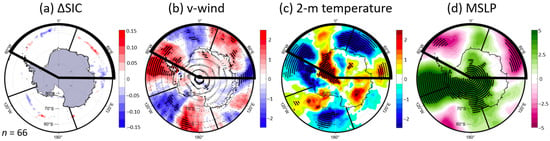

In May, the strongest relationships between anomalous daily change in Antarctic sea ice and anomalies of both meridional wind and surface air temperatures are in the Indian Ocean sector 16 days after an active MJO in phase 8. There, correlation coefficients between ∆SIC and meridional wind and surface air temperature were +0.62 (p < 0.001) and −0.50 (p < 0.001), respectively, (Figure 3a). Negative daily ∆SIC anomalies (as low as −0.10) are found between 30° and 90° E in the marginal ice zone in the Indian Ocean sector (Figure 4a), 16 days after active MJO phase 8. These statistically significant (beyond 95%; p < 0.05) sea ice anomalies are collocated with negative anomalies of surface wind (as low as −1.5 standard anomalies; Figure 4b) and positive anomalies of temperature (as high as +1.0 standard anomalies). Moreover, the strongest anomalously negative meridional winds (Figure 4b) and anomalously positive surface temperatures (Figure 4c) are located in the transition region between the positive MSLP anomaly center at 90° E and the negative anomaly center at 30° E (Figure 4d), both of which are statistically significant beyond 97.5% (p < 0.025). Physically, this result means that 16 days after an active MJO in phase 8, anomalous sea ice decline in the central and eastern Indian ocean sectors between 30° and 90° E is co-located with (and supported by) regions of anomalously poleward winds (Figure 4b) and above-normal temperatures (Figure 4c). In addition, in the western portion of the Indian Ocean sector, between 20° and 30° E, positive ∆SIC anomalies (up to +0.08; Figure 4a) are collocated with colder temperatures and equatorward-directed winds (Figure 4b,c). At day 16, MSLP anomalies form a wavenumber-three pattern around the continent (Figure 4d), with two areas of anomalous high pressure centered around 20° W and 90° E and an area of anomalous low pressure centered between them at 30° E. This MSLP wave pattern appears similar to the response in Antarctic circulation to MJO convection in the tropical Western Hemisphere (phase 8) found by [68]. Because the anomalous surface winds and resulting anomalous surface temperatures are likely a gradient response to these MJO-driven pressure anomalies, e.g., ref. [88], the collocation of sea ice anomalies with anomalies of meridional wind and temperature suggests MJO modulation of sea ice in the Indian Ocean sector in May, approximately two weeks after active phase 8.

Figure 3.

Time-lagged correlations between anomalous daily ∆SIC and anomalous 10 m meridional wind (shading) and 2 m air temperature (filled circles) by sector and MJO phase for the month of May. The color scheme applies to both temperature and wind. Furthermore, the size of the circles qualitatively indicates the magnitude of correlation between sea ice and temperature. The gray box indicates the phase and time lag selected for further analysis in Figure 4, in this case over the Indian Ocean sector, 16 days after MJO phase 8.

Figure 4.

(a) Anomalous daily ∆SIC (in concentration); (b) average 10 m wind (vector) and anomalous meridional component (shading) (both in m s−1); (c) anomalous 2 m temperature (in °C); and (d) anomalous mean sea-level pressure (in hPa), in May, 16 days after an active MJO phase 8. The Indian Ocean sector is highlighted and corresponds to the gray box in Figure 3. All ∆SIC anomalies are statistically significant at the 95th percentile or above. Stippling in panels (b–d) indicates the significance of wind, temperature, and pressure, respectively, at the 95th percentile. The number of active MJO days in the composite is given by n.

It is important to note that while the strongest correlations between anomalies in sea ice and both v-wind and SAT during the month of May occur 16 days after active MJO phase 8, these maxima in correlations do not appear instantaneously but rather build slowly from day +9, reaching their peak on day +16 and then decaying slowly to day +20 (Figure 3a). Similar, although weaker, correlations are also observed in adjacent phases (5–7). This anomaly pattern, where the signal is present over multiple time lags and in adjacent phases, is typical of the quasi-cyclic modulation of the extratropics by the MJO [34,89]. Finally, it is important to note that in May, sea ice anomalies in other sectors are moderately correlated with anomalies of one, but not both, of the two surface variables (e.g., with v-wind but not temperature). For example, in the Western Pacific Ocean sector, 10–12 days after active MJO phases 1 and 2, ∆SIC is moderately correlated with meridional wind (correlation coefficients as high as +0.50; p < 0.001) but only weakly correlated with SAT (correlation coefficients around −0.10; p = 0.025) (Figure 3b). Similarly, 8–12 days after an active MJO phase 8, ∆SIC in the B&A Seas is moderately correlated with SAT (−0.40; p < 0.001) but not with v-wind (r near zero) (Figure 3d). Other regional agreement between SIC and the v-wind (but not SAT) is seen in the western Ross Sea 13–15 days after active MJO phases 3–5 (Figure 3c).

3.2.3. MJO Modulation of Sea Ice in July

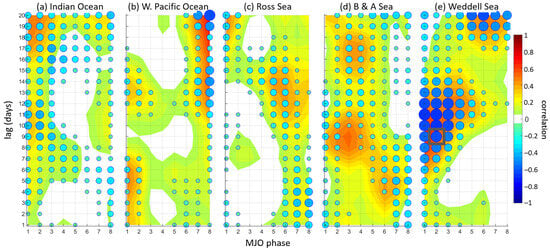

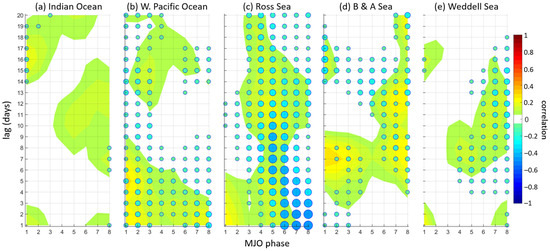

In July, the strongest relationships between anomalous daily change in Antarctic sea ice and anomalies of both meridional wind and surface air temperatures are in the Weddell Sea sector nine days after an active MJO in phase 2 (Figure 5e). There, correlation coefficients between ∆SIC and meridional wind and surface air temperature were +0.59 and −0.63, respectively (p < 0.001 for both). Statistically significant positive and negative ∆SIC anomalies are observed in the Weddell Sea, with negative ∆SIC anomalies as large as −0.05 in the western part of the sector (60° W–5° W) and positive ∆SIC anomalies as large as +0.15 in the eastern part of the sector (5° W–20° E) (Figure 6a). The negative sea ice anomalies in the western Weddell Sea are collocated with statistically significant negative anomalies of meridional surface wind (as low as −1.5 standard anomalies in the western part of the sector; Figure 6b) and statistically significant positive anomalies of surface air temperature (as high as +2.5 standard anomalies near 50° W; Figure 6c). The positive sea ice anomalies in the eastern Weddell Sea are collocated with statistically significant positive anomalies of meridional surface wind (as high as +2.5 standard anomalies; Figure 6b) and statistically significant negative anomalies of surface air temperature (as low as −3.0 standard anomalies; Figure 6c). The strongest anomalies in v-winds and SAT are located between statistically significant centers of anomalous sea-level pressure (Figure 6d): warm temperatures and poleward (northerly) surface winds in the positive-to-negative MSLP transition between 130° W and 30° W and cold temperatures and equatorward (southerly) surface winds in the negative-to-positive MSLP transition between 30° W and 60° E.

Physically, this result means that nine days after an active MJO in phase 2, anomalous sea ice decline in the marginal ice zone in the western and central Weddell Sea is co-located with (and supported by) anomalously poleward surface winds and above-normal temperatures, and anomalous sea ice growth in the eastern Weddell Sea is collocated with anonymously equatorward surface winds and below-normal temperatures. Moreover, nine days after MJO phase 2, a wavenumber-three pattern in MSLP anomalies is observed around Antarctica (Figure 6d), similar to what was seen in May after an active MJO phase 8 (Figure 4d) but with the anomalous pressure centers shifted about 30° counterclockwise (compare Figure 4d and Figure 6d). This anomalous sea-level pressure pattern likely drives a gradient response in the anomalous surface flow and temperatures that support the observed anomalous changes in sea ice concentration in July.

Finally, it is important to note that in July, just as in May, correlations between sea ice and atmospheric circulation and temperature anomalies in the Weddell Sea build from days +6 to +9 and decay from days +10 to +14 after phase 2, indicative of the quasi-cyclic MJO. Moreover, sea ice anomalies in other sectors are moderately correlated with anomalies of one, but not both, of the two atmospheric surface variables. For example, in the B&A Seas sector 8–10 days after an active MJO phase 3, ΔSIC is moderately correlated with the v-wind but has near-zero correlations with SAT (Figure 5d). Similarly, in the Indian Ocean sector 15–17 days after an active MJO in phases 4–6 (Figure 5a), sea ice change is moderately correlated with surface air temperature but has near-zero correlation with meridional wind.

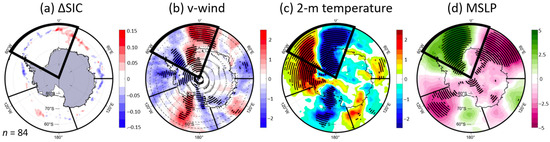

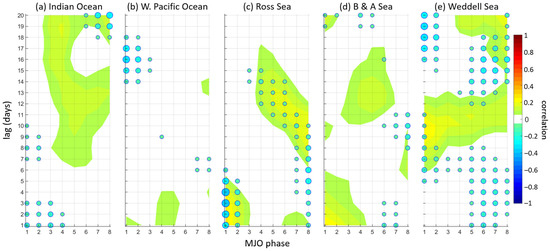

3.2.4. MJO Modulation of Sea Ice in September

In September, the strongest relationships between anomalous daily change in Antarctic sea ice and anomalies of both meridional wind and surface air temperatures are in the (adjoining) Indian Ocean and Weddell Sea sectors six days after an active MJO in phase 8 (Figure 7a,e). There, correlation coefficients between ∆SIC and meridional wind and surface air temperature were +0.43 and −0.38, respectively (p < 0.001 for both), in the Indian Ocean sector and +0.55 and −0.49, respectively (p < 0.001 for both), in the Weddell Sea sector. Both positive and negative ∆SIC anomalies—statistically significant beyond the 95th percentile (p < 0.05)—are observed in both sectors (Figure 8a). Negative sea ice anomalies in the eastern Indian Ocean sector (70–90° E) are as large as −0.07, and in the central Weddell Sea sector (30° W–0°), they are as large as −0.15. Both of these areas of anomalous sea ice decline are collocated with statistically significant negative anomalies of meridional wind (standard anomalies as low as −1.5; Figure 8b) and statistically significant positive anomalies of surface air temperature (standard anomalies as high as +1.2; Figure 8c). Positive anomalies in sea ice concentration are as large as +0.05 in the western Indian Ocean sector (55–40° W) and as large as +0.15 in the western and central Weddell Sea sector (20–60° E) (Figure 8a). These areas of anomalous sea ice growth are collocated with statistically significant positive anomalies of meridional wind (standard anomalies as high as +2.0 in the western Indian Ocean sector; Figure 8b) and statistically significant negative anomalies of surface air temperature (standard anomalies as low as −2.5 in the western Indian Ocean and central Weddell Sea sectors; Figure 8c).

As in May and July, the strongest anomalies in v-winds and SAT in September are situated between statistically significant centers of anomalous sea-level pressure arrayed in a wavenumber-three pattern (Figure 8d): the two regions of anomalously warm temperatures and poleward (northerly) surface winds are located between the anomalous high pressure centered near 110° W and anomalous low pressure near 40° W and between the anomalous high near 10° E and the low near 60° E. Similarly, the two regions of anomalously cold temperatures and equatorward (southerly) surface winds are located between the anomalous low near 40° W and the high near 10° E, and between the anomalous low near 60° E and a high near 90° E. Physically, this result means that sea-level pressure anomalies six days after an active MJO in phase 8 drive meridional wind and surface temperature anomalies in the Indian Ocean and Weddell Sea sectors that lead to anomalous sea ice growth in the western Weddell Sea and western and central Indian Ocean sectors and anomalous sea ice declines in the central and eastern Weddell Sea and eastern Indian Ocean sectors.

It is important to note that while the strongest correlations in September between sea ice anomalies and meridional wind and surface air temperature occur in the Indian Ocean and Weddell Sea sectors six days after an active MJO phase 8, other moderate correlations between ∆SIC and both meridional wind and surface air temperature are found in the Ross Sea sectors two to eight days after phases 1–4, in the Western Pacific sector they are 10–16 days after phases 1–3, and in the B&A Sea sector they are 16–20 days after phases 1–3 (Figure 7). Those two correlations, however, are not as large as the correlations in the Indian Ocean and Weddell Sea sectors six days after phase 8.

3.2.5. MJO Modulation of Sea Ice in November and January

While moderate-to-strong relationships between anomalous concentrations of Antarctic sea ice and anomalies of both meridional wind and surface air temperature were found by MJO phase during May, July, and September, no such relationships were found in November (Figure 9) or January (Figure 10). For example, in November, while anomalies of ∆SIC are moderately correlated with SAT in the Ross Sea sector 1–3 days after an active MJO in phases 6–8 (Figure 9c), anomalies of ∆SIC are only weakly correlated with meridional wind during those phases at those time lags. Moreover, as noted by [34], time lags of 1–3 days are not typically indicative of an extratropical response to the MJO, as the Rossby wave trains extending from the tropical MJO convection do not tend to modulate the extratropical circulation immediately after the active MJO. Similarly, only weak correlations between ∆SIC and both meridional winds and surface air temperatures are found in November in other sectors, phases, and time lags (Figure 9). In January, correlations between ∆SIC and meridional wind and surface temperatures are even smaller than in November (Figure 10), revealing that in no sector was there at least a moderate correlation between sea ice and the atmosphere in the 20 days after an active MJO. This finding of only weak correlations between sea ice anomalies and anomalies of meridional wind and surface air temperature in both November and January agrees with previous work noting that MJO modulation of Antarctic sea ice tends to be strongest in the months of sea ice growth (May–August) and maximum coverage (September) [29,72,73].

Figure 9.

As in Figure 3, but for November.

Figure 10.

As in Figure 3, but for January.

4. Discussion

The variability of Antarctic sea ice in response to the Madden–Julian Oscillation appears to follow the following physical pathway: (1) tropical MJO convection acts as a Rossby wave source into the extratropics; (2) Rossby waves extending into the extratropics modulate sea-level pressures around Antarctica; (3) a gradient response to those sea-level pressure anomalies adjusts surface wind and air temperatures; and (4) surface wind and air temperature anomalies, in turn, modulate sea ice in the marginal ice zone around Antarctica. Of this physical pathway by which the MJO can modulate Antarctic sea ice, steps (1)–(3) were confirmed in earlier studies, and step (4) was explored here.

Our results suggest that the strongest modulation of Antarctic sea ice by the MJO occurs over the Indian Ocean and Weddell Sea sectors from May to September, when sea ice coverage in the marginal ice zone in those sectors around Antarctica is the largest. The most important time lags vary by month, phase, and sector, with MJO modulation of sea ice appearing strongest in May in the Indian Ocean sector 16 days after an active MJO in phase 8, strongest in July in the Weddell Sea sector nine days after an active MJO in phase 2, and strongest in September in the Indian Ocean and Weddell Sea sectors six days after an active MJO in phase 8. No strong signal for MJO modulation of Antarctic sea ice was found in November or January, perhaps because of lower sea ice concentrations in those months (Figure 2d,e).

This study builds on and extends previous work on subseasonal modulation of Antarctic sea ice by the MJO in several key ways. For example, ref. [72] noted that MJO convection over the tropical Indian and Western Pacific Oceans (phases 2–7) excites a wavenumber-three circulation pattern around Antarctica that reduces sea ice in the Indian Ocean, Ross Sea, and B&A Seas sectors. We found a similar wavenumber-three pattern in sea-level pressure anomalies with the strongest modulation of sea ice by the MJO in the Indian Ocean sector after phase 2. Ref. [73] noted that MJO convection over the tropical Indian Ocean (phase 2) promotes cyclonic and anticyclonic circulations at 500 hPa that drive sea ice growth in the Western Pacific Ocean sector and sea ice decline in the B&A Seas sector. Ref. [73] also found that MJO convection over the Maritime Continent (phase 4) promotes 500 hPa circulations that drive ice growth in the Ross and B&A Seas sectors and ice decline in the Weddell Sea sector. Our results agree with those two studies in part, as we found sea ice modulation after MJO phase 2 in the Weddell Sea sector but not in either the Ross or B&A sectors or after MJO phase 4. Furthermore, our results showing MJO modulation of sea ice in September are similar to [29], who found subseasonal modulation of sea ice by the MJO in the spring and in the Weddell Sea. Our results showing MJO modulation of sea ice in May agree with [90], who found subseasonal variability of sea ice in the fall. Finally, we considered time lags for up to 20 days after the active MJO, building on [73], who examined them up to day +15, and [72], who did not explicitly examine time-lagged sea ice anomalies.

Our methodology of evaluating the MJO modulation of Antarctic sea ice by comparing anomalies of daily change in sea ice concentration with anomalies of surface winds and temperatures via field correlations seems to be most successful in detecting modulation in months when the marginal ice zone is spatially expansive. Thus, in the late summer and early fall months of February–March, the overall limited extent of the marginal ice zone resulted in near-zero correlations between anomalous change in sea ice and both meridional wind and SAT in all sectors and at days 0–20 after all eight MJO phases. However, it is unclear if the low correlations are indicative of the absence of MJO modulation of sea ice in those months or a consequence of the methodology. The lack of a clear signal in November and January may be due as much to the spatial confinement of the marginal ice zone as to a lack of MJO signal.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we examined the variability of Antarctic sea ice by phase of the Madden–Julian Oscillation over five sectors surrounding Antarctica. We compared anomalous daily change in sea ice concentration (∆SIC) and anomalies of two atmospheric variables known to be related to sea ice variability and sensitive to the MJO: meridional surface wind and surface air temperature [4,21,22,23]. Time-lagged correlations between daily anomalies of ∆SIC, v-winds, and SAT highlighted the sectors and phases with the strongest relationships with the MJO. Sea ice in the Indian Ocean and Weddell Sea sectors was found to have the variability most strongly linked to the MJO, and phases 2 and 8 were found to be the most important phases. In May, relationships between anomalous daily change in sea ice concentration and anomalies in SAT and v-wind were strongest over the Indian Ocean sector 16 days after MJO phase 8. In response to the MJO, a wavenumber-three pattern in MSLP anomalies developed over Antarctica, resulting in anomalously northerly surface winds and warmer temperatures over the central and eastern portions of the Indian Ocean sector and anomalous southerly winds and colder temperatures over the western portion of the sector. These atmospheric anomalies support anomalous sea ice decline in the central and eastern Indian Ocean sector and anomalous sea ice growth in the western Indian Ocean sector. In July, the strongest relationships between the atmosphere and Antarctic sea ice were found in the Weddell Sea sector nine days after MJO phase 2, with anomalous sea ice decline in the western and central portions of the sector and anomalous sea ice growth in the eastern portion of the sector. In September, the strongest relationships between the atmosphere and Antarctic sea ice were observed in the Indian Ocean and Weddell Sea sectors six days after MJO phase 8, with anomalous sea ice decline in the central and eastern Weddell Sea and eastern Indian Ocean sector, and anomalous sea ice growth in the western Weddell Sea and western and central Indian Ocean sector. No moderate or strong correlations were found in November or January between anomalies of sea ice and MJO-driven anomalies of both SAT and meridional wind, in agreement with earlier studies.

Our results suggest connections between Antarctic sea ice, the atmosphere, and the MJO on the subseasonal time scale from fall through winter. Additional work could further clarify the relationship. For example, future studies may explore the connections between the MJO modulation of Antarctic sea ice and other large-scale features of the Antarctic climate system, including atmospheric blocking [91], atmospheric rivers [92,93], and the Antarctic Oscillation [69]. Since the MJO has been found to produce blocking-like patterns in Antarctic circulation [67,68] and modulate the Southern Annular Mode [66], future work is needed to better understand these complex relationships, including the potential for constructive or destructive interference with internal variability of Antarctic sea ice (e.g., [70]) or longer-period oscillations, such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation [94], as those were not explicitly considered here. Indeed, the anomalies here represent the composite MJO signal superimposed on this background variability, including the Southern Annular Mode [95]. Ref. [72] suggested that the sudden loss of sea ice in 2016, potentially associated with the MJO, could have weakened the polar stratospheric vortex, potentially resulting in feedback from the stratosphere to the Antarctic cryosphere and sea ice. That feedback was beyond the scope of this work, and future work could consider these interactions. The results here are based on the widely used RMM index of [79], but other MJO indices—including those with different filters and based on velocity potential or outgoing longwave radiation—could capture additional signal beyond the RMM. Additionally, an ice budget analysis could identify the relative contributions of temperature and wind to sea ice change. Finally, our analysis focused on 1989–2019 to avoid the abrupt decline in annual sea ice extent over Antarctica beginning in 2020 [60,96,97], and future work could examine the MJO modulation of sea ice in the context of those abrupt changes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S.B. and G.R.H.; methodology, B.S.B., D.M.L., and G.R.H.; software: B.S.B. and D.M.L.; formal analysis: B.S.B. and D.M.L.; writing—original draft: B.S.B., D.M.L., and G.R.H.; visualization, G.R.H., funding acquisition: B.S.B. and G.R.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the US National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs (OPP), award number 1821915.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Sea ice concentration data analyzed in this study are openly available from the NOAA/NSIDC Climate Data Record of Passive Microwave Sea Ice Concentration at the NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center at https://doi.org/10.7265/N59P2ZTG, as cited in [98]. The Real-time Madden–Julian Oscillation index used in this study is openly available from the Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology at http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/mjo/ (accessed on 10 July 2025) as cited in [79], https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(2004)132%3C1917:AARMMI%3E2.0.CO;2. Atmospheric datasets analyzed in this study are from the ERA5 global reanalysis as cited in [84], https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments to improve the manuscript. The authors also thank N. Mahmud for assisting with manuscript formatting.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, J.; Curry, J.A.; Martinson, D.G. Interpretation of Recent Antarctic Sea Ice Variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, L02205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, W.; Goosse, H. Influence of the Southern Annular Mode on the Sea Ice-Ocean System: The Role of the Thermal and Mechanical Forcing. Ocean Sci. 2005, 1, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.; Comiso, J.C.; Marshall, G.J.; Lachlan-Cope, T.A.; Bracegirdle, T.; Maksym, T.; Meredith, M.P.; Wang, Z.; Orr, A. Non-Annular Atmospheric Circulation Change Induced by Stratospheric Ozone Depletion and Its Role in the Recent Increase of Antarctic Sea Ice Extent. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36, L08502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, P.R.; Kwok, R. Wind-Driven Trends in Antarctic Sea-Ice Drift. Nat. Geosci. 2012, 5, 872–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matear, R.J.; O’Kane, T.J.; Risbey, J.S.; Chamberlain, M. Sources of Heterogeneous Variability and Trends in Antarctic Sea-Ice. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, E.; Roach, L.A.; Donohoe, A.; Ding, Q. Impact of Winds and Southern Ocean SSTs on Antarctic Sea Ice Trends and Variability. J. Clim. 2021, 34, 949–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabe, S.; Spelman, M.J.; Stouffer, R.J. Transient Responses of a Coupled Ocean-Atmosphere Model to Gradual Changes of Atmospheric CO2. Part II: Seasonal Response. J. Clim. 1992, 5, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eicken, H.; Fischer, H.; Lemke, P. Effects of the Snow Cover on Antarctic Sea Ice and Potential Modulation of Its Response to Climate Change. Ann. Glaciol. 1995, 21, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Powell, D.C.; Markus, T.; Stössel, A. Effects of Snow Depth Forcing on Southern Ocean Sea Ice Simulations. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2005, 110, C06001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Curry, J.A. Accelerated Warming of the Southern Ocean and Its Impacts on the Hydrological Cycle and Sea Ice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14987–14992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.S.; Comiso, J.C. Climate Variability in the Amundsen and Bellingshausen Seas. J. Clim. 1997, 10, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohout, A.L.; Williams, M.J.M.; Dean, S.M.; Meylan, M.H. Storm-Induced Sea-Ice Breakup and the Implications for Ice Extent. Nature 2014, 509, 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eayrs, C.; Li, X.; Raphael, M.N.; Holland, D.M. Rapid Decline in Antarctic Sea Ice in Recent Years Hints at Future Change. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purich, A.; Doddridge, E.W. Record Low Antarctic Sea Ice Coverage Indicates a New Sea Ice State. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goosse, H.; Fichefet, T. Importance of Ice-Ocean Interactions for the Global Ocean Circulation: A Model Study. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 1999, 104, 23337–23355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rintoul, S.R. The Global Influence of Localized Dynamics in the Southern Ocean. Nature 2018, 558, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langhorne, P.J.; Squire, V.A.; Fox, C.; Haskell, T.G. Break-up of Sea Ice by Ocean Waves. Ann. Glaciol. 1998, 27, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squire, V.A. Ocean Wave Interactions with Sea Ice: A Reappraisal. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2020, 52, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Increasing Antarctic Sea Ice under Warming Atmospheric and Oceanic Conditions. J. Clim. 2007, 20, 2515–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stammerjohn, S.; Massom, R.; Rind, D.; Martinson, D. Regions of Rapid Sea Ice Change: An Inter-Hemispheric Seasonal Comparison. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, L06501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heil, P.; Fowler, C.W.; Lake, S.E. Antarctic Sea-Ice Velocity as Derived from SSM/I Imagery. Ann. Glaciol. 2006, 44, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, M.N. The Influence of Atmospheric Zonal Wave Three on Antarctic Sea Ice Variability. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2007, 112, D12112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, M.N.; Hobbs, W. The Influence of the Large-Scale Atmospheric Circulation on Antarctic Sea Ice during Ice Advance and Retreat Seasons. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 5037–5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Wang, J.; Luo, H.; Yang, Q. The Role of Atmospheric Rivers in Antarctic Sea Ice Variations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2022GL102588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichi, M. A Statistical Definition of the Antarctic Marginal Ice Zone. Cryosphere Discuss. 2021, 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichi, M. An Indicator of Sea Ice Variability for the Antarctic Marginal Ice Zone. Cryosphere 2022, 16, 4087–4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmich, K.; Vancoppenolle, M.; Madec, G.; Sallée, J.B.; Holland, P.R.; Lebrun, M. Drivers of Antarctic Sea Ice Advance. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, W.R.; Massom, R.; Stammerjohn, S.; Reid, P.; Williams, G.; Meier, W. A Review of Recent Changes in Southern Ocean Sea Ice, Their Drivers and Forcings. Glob. Planet. Change 2016, 143, 228–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Massonnet, F.; Goosse, H.; Luo, H.; Barthélemy, A.; Yang, Q. Synergistic Atmosphere-Ocean-Ice Influences Have Driven the 2023 All-Time Antarctic Sea-Ice Record Low. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, K.; Minobe, S.; Kimura, N.; Wakatsuchi, M. Intraseasonal Variability of Sea-ice Concentration in the Antarctic with Particular Emphasis on Wind Effect. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2006, 111, C12023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, S. Causes of the Record-Low Antarctic Sea-Ice in Austral Summer 2022. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett. 2023, 16, 100353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, I. Modes of Atmospheric Variability over the Southern Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2003, 108, SOV 5-1–SOV 5-30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, A.M.C.; Blundell, J.R. Interdecadal Variability of the Southern Ocean. J. Phys. Ocean. 2006, 36, 1626–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Brunet, G. Extratropical Response to the MJO: Nonlinearity and Sensitivity to the Initial State. J. Atmos. Sci. 2018, 75, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppler, L.; Landschützer, P. Regional Wind Variability Modulates the Southern Ocean Carbon Sink. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.; Marshall, G.J.; Clem, K.; Colwell, S.; Phillips, T.; Lu, H. Antarctic Temperature Variability and Change from Station Data. Int. J. Climatol. 2020, 40, 2986–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, R.A.; Julian, P.R. Detection of a 40–50 Day Oscillation in the Zonal Wind in the Tropical Pacific. J. Atmos. Sci. 1971, 28, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, R.A.; Julian, P.R. Description of Global-Scale Circulation Cells in the Tropics with a 40–50 Day Period. J. Atmos. Sci. 1972, 29, 1109–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendon, H.H.; Salby, M.L. The Life Cycle of the Madden–Julian Oscillation. J. Atmos. Sci. 1994, 51, 2225–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, R.A.; Julian, P.R. Observations of the 40–50-Day Tropical Oscillation—A Review. Mon. Weather Rev. 1994, 122, 814–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. Madden-Julian Oscillation. Rev. Geophys. 2005, 43, 2004RG000158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. The Madden-Julian Oscillation. Atmos. Ocean 2022, 60, 338–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, A.; Maloney, E. Moisture Modes and the Eastward Propagation of the MJO. J. Atmos. Sci. 2013, 70, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafleur, D.M.; Barrett, B.S.; Henderson, G.R. Some Climatological Aspects of the Madden–Julian Oscillation (MJO). J. Clim. 2015, 28, 6039–6053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, B.J.; Karoly, D.J. The Steady Linear Response of a Spherical Atmosphere to Thermal and Orographic Forcing. J. Atmos. Sci. 1981, 38, 1179–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundy, P.E. Tropical–extratropical interactions. In Intraseasonal Variability in the Atmosphere-Ocean Climate System; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 497–512. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Lindsay, R.; Schweiger, A.; Steele, M. The Impact of an Intense Summer Cyclone on 2012 Arctic Sea Ice Retreat. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Kaplan, M.R.; Cane, M.A. The Interconnected Global Climate System—A Review of Tropical–Polar Teleconnections. J. Clim. 2018, 31, 5765–5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Chang, E.K.M. The Role of MJO Propagation, Lifetime, and Intensity on Modulating the Temporal Evolution of the MJO Extratropical Response. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124, 5352–5378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Chang, E.K.M. The Role of Extratropical Background Flow in Modulating the MJO Extratropical Response. J. Clim. 2020, 33, 4513–4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, G.R.; Barrett, B.S.; Lafleur, D.M. Arctic Sea Ice and the Madden–Julian Oscillation (MJO). Clim. Dyn. 2014, 43, 2185–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-S.; Lee, S.; Son, S.-W.; Feldstein, S.B.; Kosaka, Y. The Impact of Poleward Moisture and Sensible Heat Flux on Arctic Winter Sea Ice Variability. J. Clim. 2015, 28, 5030–5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Arblaster, J.M.; Wheeler, M.C.; Lim, E.P. Understanding MJO Teleconnections to the Southern Hemisphere Extratropics During El Niño, La Niña, and Neutral Years. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, C.L.; Cavalieri, D.J. Antarctic Sea Ice Variability and Trends, 1979–2010. Cryosphere 2012, 6, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpkins, G.R.; Ciasto, L.M.; England, M.H. Observed Variations in Multidecadal Antarctic Sea Ice Trends during 1979–2012. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 3643–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, P.R. The Seasonality of Antarctic Sea Ice Trends. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 4230–4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.; Hosking, J.S.; Bracegirdle, T.J.; Marshall, G.J.; Phillips, T. Recent Changes in Antarctic Sea Ice. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2015, 373, 20140163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, M.M.; Landrum, L.; Raphael, M.; Stammerjohn, S. Springtime Winds Drive Ross Sea Ice Variability and Change in the Following Autumn. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handcock, M.S.; Raphael, M.N. Modeling the Annual Cycle of Daily Antarctic Sea Ice Extent. Cryosphere 2020, 14, 2159–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonan, D.B.; Dörr, J.; Wills, R.C.; Thompson, A.F.; Årthun, M. Sources of Low-Frequency Variability in Observed Antarctic Sea Ice. Cryosphere 2024, 18, 2141–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionita, M. Large-Scale Drivers of the Exceptionally Low Winter Antarctic Sea Ice Extent in 2023. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1333706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, A.; Fricker, H.A.; Farrell, S.L. Trends and Connections across the Antarctic Cryosphere. Nature 2018, 558, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwally, H.J.; Parkinson, C.L.; Comiso, J.C. Variability of Antarctic Sea Ice: And Changes in Carbon Dioxide. Science 1983, 220, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worby, A.P.; Geiger, C.A.; Paget, M.J.; Van Woert, M.L.; Ackley, S.F.; DeLiberty, T.L. Thickness Distribution of Antarctic Sea Ice. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2008, 113, C05S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, B.; Fauchereau, N.; Reason, C.J.C.; Rouault, M. Relationships between the Antarctic Oscillation, the Madden–Julian Oscillation, and ENSO, and Consequences for Rainfall Analysis. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatau, M.; Kim, Y.J. Interaction between the MJO and Polar Circulations. J. Clim. 2013, 26, 3562–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauchereau, N.; Pohl, B.; Lorrey, A. Extratropical Impacts of the Madden–Julian Oscillation over New Zealand from a Weather Regime Perspective. J. Clim. 2016, 29, 2161–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, G.R.; Barrett, B.S.; Lois, A.; Elsaawy, H. Time-Lagged Response of the Antarctic and High-Latitude Atmosphere to Tropical MJO Convection. Mon. Weather Rev. 2018, 146, 1219–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatau, M.K.; Henderson, G.R.; McLay, J.G. Tropics–extratropics interactions: The influence of Madden–Julian oscillation on annular modes. In Atmospheric Oscillations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 321–333. [Google Scholar]

- Renwick, J.A.; Kohout, A.; Dean, S. Atmospheric Forcing of Antarctic Sea Ice on Intraseasonal Time Scales. J. Clim. 2012, 25, 5962–5975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohyama, T.; Hartmann, D.L. Antarctic Sea Ice Response to Weather and Climate Modes of Variability. J. Clim. 2016, 29, 721–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Hendon, H.H.; Arblaster, J.M.; Lim, E.-P.; Abhik, S.; van Rensch, P. Compounding Tropical and Stratospheric Forcing of the Record Low Antarctic Sea-Ice in 2016. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Seo, K.H. Impact of the Madden-Julian Oscillation on Antarctic Sea Ice and Its Dynamical Mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwally, H.J.; Comiso, J.C.; Parkinson, C.L.; Campbell, W.J.; Carsey, F.D.; Gloersen, P. Antarctic Sea Ice, 1973–1976: Satellite Passive-Microwave Observations; Scientific and Technical Information Branch, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA): Washington, DC, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, C.L.; Cavalieri, D.J. Arctic Sea Ice Variability and Trends, 1979–2006. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2008, 113, C07003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetterer, F.; Knowles, K.; Meier, W.N.; Savoie, M.; Windnagel, A.K. Sea Ice Index, Version 3; NSIDC Special Report; National Snow and Ice Data Center: Boulder, CO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalieri, D.; Parkinson, C.; Gloersen, P.; Zwally, H.J. Sea Ice Concentrations from Nimbus-7 SMMR and DMSP SSM/I-SSMIS Passive Microwave Data, Version 1; NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center: Boulder, CO, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Luo, H.; Yang, Q.; Liu, J.; Yu, L.; Shi, Q.; Han, B. An Unprecedented Record Low Antarctic Sea-Ice Extent during Austral Summer 2022. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2022, 39, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M.C.; Hendon, H.H. An All-Season Real-Time Multivariate MJO Index: Development of an Index for Monitoring and Prediction. Mon. Weather Rev. 2004, 132, 1917–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschalck, J.; Wheeler, M.; Weickmann, K.; Vitart, F.; Savage, N.; Lin, H.; Hendon, H.; Waliser, D.; Sperber, K.; Nakagawa, M.; et al. A Framework for Assessing Operational Madden–Julian Oscillation Forecasts: A CLIVAR MJO Working Group Project. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2010, 91, 1247–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Zhu, J.; Wang, W. Assessing Predictive Potential Associated with the MJO during the Boreal Winter. Mon. Weather Rev. 2020, 148, 4957–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Adames, Á.F.; Kim, D.; Maloney, E.D.; Lin, H.; Kim, H.; Zhang, C.; DeMott, C.A.; Klingaman, N.P. Fifty Years of Research on the Madden-Julian Oscillation: Recent Progress, Challenges, and Perspectives. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2020, 125, e2019JD030911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, K.C.; Maloney, E.; Barnes, E. The Consistency of MJO Teleconnection Patterns: An Explanation Using Linear Rossby Wave Theory. J. Clim. 2019, 32, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 Global Reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, D.S. Statistical Methods in the Atmospheric Sciences; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; Volume 100. [Google Scholar]

- Vichi, M.; Eayrs, C.; Alberello, A.; Bekker, A.; Bennetts, L.; Holland, D.; de Jong, E.; Joubert, W.; MacHutchon, K.; Messori, G.; et al. Effects of an Explosive Polar Cyclone Crossing the Antarctic Marginal Ice Zone. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 5948–5958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachter, P.; Reiser, F.; Friedl, P.; Jacobeit, J. A New Approach to Classification of 40 Years of Antarctic Sea Ice Concentration Data. Int. J. Climatol. 2020, 41, E2683–E2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukens, K.E.; Feldstein, S.B.; Yoo, C.; Lee, S. The Dynamics of the Extratropical Response to Madden–Julian Oscillation Convection. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2017, 143, 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, A.J. Primary and Successive Events in the Madden–Julian Oscillation. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2008, 134, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, L.; Goessling, H.F.; Jung, T. Predictability of Antarctic Sea Ice Edge on Subseasonal Time Scales. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 9719–9727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, J.C.; Bozkurt, D.; Barrett, B.S. Atmospheric Blocking Trends and Seasonality around the Antarctic Peninsula. J. Clim. 2022, 35, 3803–3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, D.; Marín, J.C.; Verdugo, C.; Barrett, B.S. Atmospheric Blocking and Temperatures in the Antarctic Peninsula. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 931, 172852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, D.; Rondanelli, R.; Marín, J.C.; Garreaud, R. Foehn Event Triggered by an Atmospheric River Underlies Record-Setting Temperature Along Continental Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018, 123, 3871–3892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Duan, A.; Yao, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Q. Role of the Subtropical Southern Indian Ocean in the Interannual Variability of Antarctic Summer Sea Ice. Atmos. Res. 2024, 311, 107723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, K.; Renwick, J. Aspects of intraseasonal variability of Antarctic sea ice in austral winter related to ENSO and SAM events. J. Glaciol. 2017, 63, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, M.N.; Handcock, M.S. A New Record Minimum for Antarctic Sea Ice. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 215–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xiao, C.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Qin, D. Variability of Antarctic Sea Ice Extent over the Past 200 Years. Sci. Bull. 2021, 66, 2394–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Meier, W.N.; Scott, D.J.; Savoie, M.H. A Long-Term and Reproducible Passive Microwave Sea Ice Concentration Data Record for Climate Studies and Monitoring. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2013, 5, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).