Abstract

Seasonality has traditionally shaped the U.S. housing market, with activity peaking in spring-summer and declining in autumn-winter. However, recent disruptions, particularly those following COVID-19, raise questions about shifts in these patterns. This study analyzes housing market data (1991–2024) to examine evolving seasonality and regional heterogeneity. Using Housing Price Index (HPI) data, inventory, and sales data from the Federal Housing Finance Agency and U.S. Census Bureau, seasonal components are extracted via the X-13-ARIMA procedure, and statistical tests assess variations across regions. The results confirm seasonal fluctuations in prices and volumes, with recent shifts toward earlier annual peak (March–April) and amplified seasonal effects. Regional variations align with differences in climate and market structure, while prices and sales volumes exhibit in-phase movement, suggesting thick-market momentum behaviour. These findings highlight key implications for policymakers, realtors and investors navigating post-pandemic market dynamics, offering insights into the timing and interpretation of housing market activities.

1. Introduction

Seasonality is a well-documented feature of housing markets. In the United States, home prices and sales volumes typically increase during the spring and summer months and decline in the fall and winter [1]. These cyclical patterns, often referred to as “hot” and “cold” seasons, have traditionally been attributed to factors such as weather conditions, the school calendar, and the timing preferences of buyers and sellers. Understanding these patterns is not merely of academic interest; it holds practical value for optimizing household real estate decisions and guiding industry practice [2]. For instance, sellers often achieve higher prices and faster transactions during the spring surge in demand, while buyers may benefit from greater bargaining power during the winter slowdown.

However, recent disruptions, particularly those stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic, have introduced new uncertainty to housing seasonality [3]. The pandemic and its associated economic shocks disrupted traditional market behaviour, leading to unseasonal surges or delays in housing activity during 2020 [4]. By 2021–2022, analysts observed that some established seasonal patterns had either weakened or shifted, with housing demand reaching historic highs and lows in atypical months. These changes raise a critical question: have the long-standing seasonal rhythms of the U.S. housing market fundamentally evolved in the post-pandemic period?

Additionally, regional disparities in housing cycles have become more pronounced. Variations in climate, regional economic conditions, and migration trends mean that one region’s “spring boom” may occur at a different time of year than another’s [5]. Despite these observations, systematic research on how seasonality has shifted across U.S. regions in the wake of the pandemic remains limited. Existing studies largely focus on pre-2020 patterns or narrow aspects, such as seasonal adjustment methods or single-city dynamics, leaving gaps in understanding the broader regional and temporal impacts of recent disruptions [6,7,8].

Against this background, this paper addresses the following research questions:

- (1)

- Has the timing and intensity of seasonal peaks and troughs in the U.S. housing market changed in the post-pandemic period?

- (2)

- How do the magnitude and timing of seasonality differ across major U.S. regions with distinct climatic and market conditions?

- (3)

- To what extent do these seasonal shifts align with broader structural changes in housing market dynamics?

This study seeks to address these gaps by providing a comprehensive analysis of U.S. housing market seasonality with a particular focus on the post-pandemic period and regional heterogeneity. Specifically, we quantify how the timing and intensity of seasonal peaks and troughs have shifted following the pandemic and assess the extent to which the magnitude of seasonality varies across regions. These findings are crucial, as uneven shifts in seasonality could have significant implications for housing affordability, inventory management, and policy effectiveness at the regional level.

In summary, this study makes three key contributions. First, it identifies a forward shift in the timing of seasonal housing market peaks after the COVID-19 shock, reflecting an earlier onset of the “hot season” in many regions. Second, it provides a detailed comparison of seasonal patterns across U.S. regions over recent decades, offering insights into the geographical heterogeneity of these changes. Third, it documents how post-pandemic seasonality interacts with market structure and climate, thereby informing forecasting practices and housing policy. Methodologically, this study leverages a large dataset of monthly housing indicators (prices, inventory, and sales) spanning 1991 to 2024. Seasonal components are extracted using the X-13ARIMA-SEATS decomposition, and formal statistical tests and panel regression analyses (including region-by-season interactions) are conducted to validate the presence and variation of seasonality. These findings enhance our understanding of evolving market dynamics and provide actionable insights for policymakers, real estate professionals, and market participants navigating the post-pandemic U.S. housing market.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature on housing market seasonality, post-pandemic shifts, and regional heterogeneity. Section 3 describes the data sources and empirical methods, including the X-13ARIMA-SEATS procedure and panel regression framework. Section 4 presents the main results on seasonal patterns, regional differences, and robustness checks. Section 5 discusses the implications of the findings for forecasting and housing policy. Section 6 concludes and outlines avenues for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Seasonal Patterns and the Thick-Market Effect

Early studies demonstrated that housing markets exhibit predictable seasonal cycles [9,10,11]. Prices and transaction volumes tend to peak in spring and summer, followed by a decline in fall and winter. These patterns have been attributed to factors such as weather, school calendars, and buyer-seller preferences [12]. A critical insight from these studies is the “thick-market effect,” which explains how heightened activity during peak seasons reinforces itself [13]. Increased buyer density improves sellers’ bargaining power and accelerates inventory turnover, creating a self-reinforcing loop of rising prices and transaction volumes during peak periods.

Empirical evidence supports this dynamic, revealing that housing markets deviate from classical supply-demand mechanisms during peak seasons. For instance, Novy-Marx [14] showed that seasonal price-volume increases reflect a shift in the entire supply-demand equilibrium, rather than a simple price adjustment. While these findings provide a strong theoretical foundation, much of this research focuses on pre-2020 patterns and assumes stable seasonal dynamics over time. Few studies have investigated whether recent disruptions, such as the pandemic, have altered these established mechanisms or whether seasonal peaks have shifted temporally [15]. This study builds on these theoretical frameworks by exploring how seasonality has evolved in both timing and magnitude in the post-pandemic era.

2.2. Post-Pandemic Changes in Seasonality

The COVID-19 pandemic introduced unprecedented disruptions to housing market seasonality, challenging traditional cyclical patterns. McNamara [16] finds that since 2020, the U.S. housing market has exhibited amplified seasonal amplitudes, with stronger price growth during high-demand months and steeper declines during low-demand periods. Such deviations have exposed limitations in standard seasonal adjustment models (e.g., X-12/X-13), which may under-correct for the intensified fluctuations observed post-2020. For example, the summer surges and winter lulls of 2020–2021 were far more pronounced than in previous years, likely reflecting pandemic-induced shifts in consumer behaviour, economic uncertainty, and policy interventions.

Moreover, recent studies suggest that the timing of seasonal peaks has shifted [17]. Traditional market activity typically reached its zenith in May or June; however, analyses of post-2020 data indicate that peak activity now occurs earlier, often in March or April. This shift may be attributed to changes in buyer urgency, greater adoption of technology facilitating year-round market participation, or lingering effects of the pandemic that reshaped housing demand patterns [18]. While these studies highlight significant changes, they often focus on national trends and lack a comprehensive analysis of how these shifts vary across regions. To address this gap, this research examines both the timing and amplitude of seasonal changes across different U.S. regions using updated data from 1991 to 2024.

2.3. Regional Heterogeneity and Drivers of Seasonality

Seasonality in housing markets is not uniform across regions, with significant geographic variation influenced by local climate, economic conditions, and demographics. Budikova et al. [19] documented that colder regions, such as the Northeast and Midwest, exhibit more pronounced seasonal swings, while warmer areas, such as the South Atlantic and Pacific Coast, experience milder fluctuations. These findings underscore the importance of region-specific seasonal adjustments to accurately capture local housing cycles.

In addition to geographic factors, transaction composition and behavioural dynamics play a critical role in shaping seasonal patterns. Hattapoglu [20] observed that during peak seasons, a higher proportion of transactions involve larger homes or those in desirable neighborhoods, driving average prices upward. Behavioural preferences also reinforce these trends; for instance, Røed Larsen [10] identified a persistent “December discount” in Norwegian housing markets, where thin winter markets lead to lower prices. Similar dynamics are evident in the U.S., where peak-season activity amplifies both prices and volumes, reflecting a self-reinforcing demand cycle.

Despite these insights, the literature remains fragmented in its treatment of regional variation, with most studies focusing on single-city or national-level analyses. Furthermore, little attention has been given to how local seasonal patterns have evolved in the wake of the pandemic. This study addresses these gaps by systematically analyzing regional differences in seasonal intensity and timing, providing new evidence on how one region’s “off-season” can coincide with another’s peak. By quantifying these interactions, this research contributes to a more nuanced understanding of housing market seasonality across geographic and temporal dimensions.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employs a quantitative approach to examine seasonal patterns in the U.S. housing market, focusing on post-pandemic shifts and regional heterogeneity. The analysis is based on monthly housing market data spanning 1991–2024, with seasonal components isolated using statistical decomposition methods. This section outlines the research design, data sources, and analytical techniques used to address the research questions.

3.1. Data Sources and Variables

The study utilizes publicly available, high-frequency housing market data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA). The dataset spans January 1991 to December 2024, covering critical economic events such as the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. Table 1 shows the data descriptions and sources.

Table 1.

Data Sources and variables.

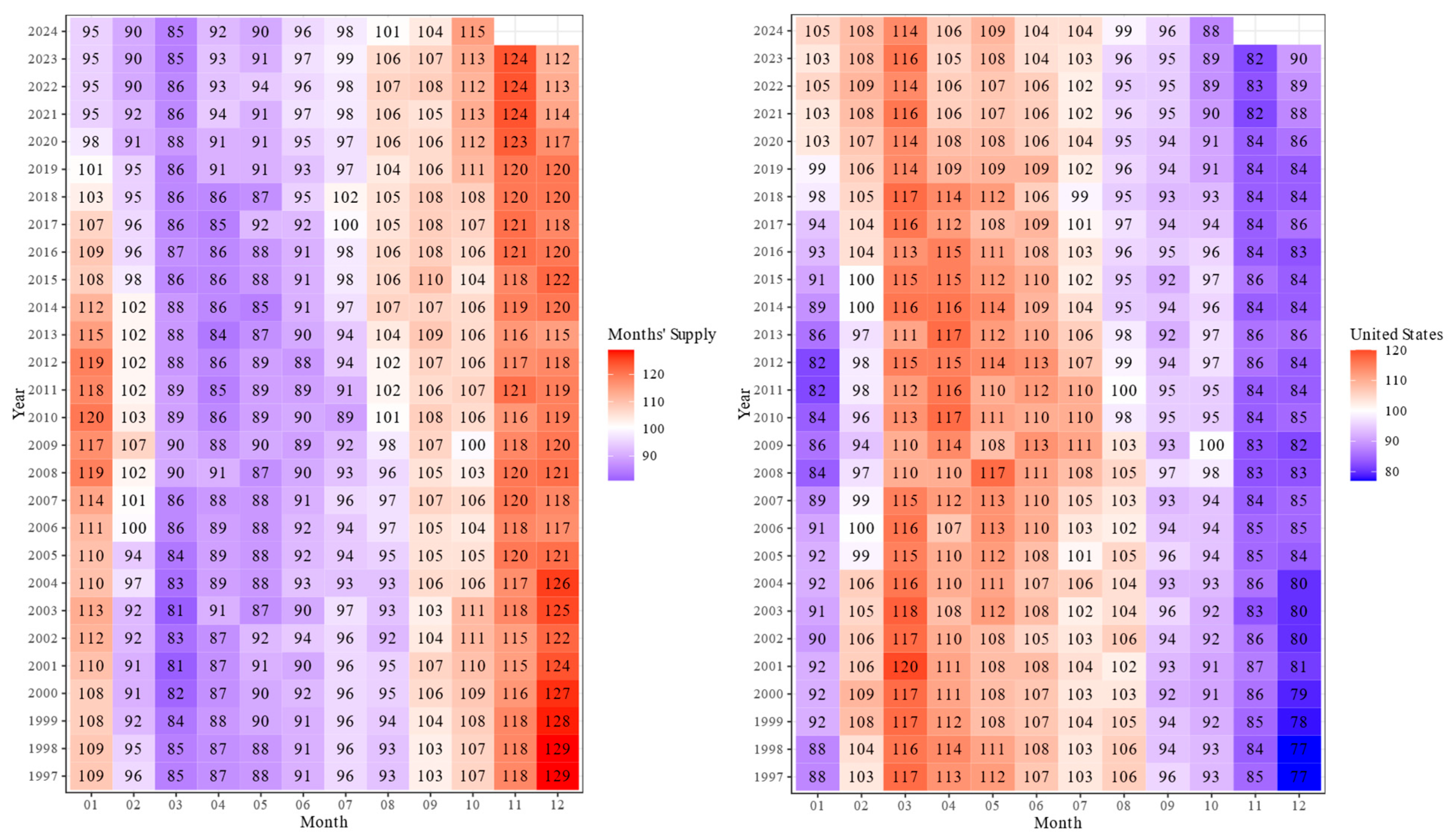

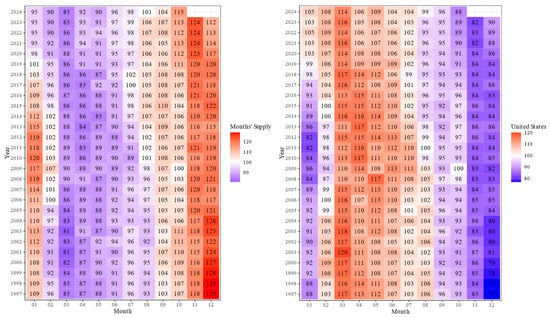

For prices, we use the FHFA House Price Index (HPI), which is available at a monthly frequency from 1991 to 2024. In addition, we draw on the U.S. Census Bureau’s “Seasonal Indexes Used to Adjust Housing Units Sold and For Sale”, which provide seasonal factors for new houses sold and for sale. These Census seasonal indexes are only published from January 1997 onwards, so analyses based on this series (Figure 1) cover the period 1997–2024, whereas the HPI-based decomposition spans 1991–2024.

Figure 1.

Seasonal indices for houses sold, houses for sale, and months’ supply in the United States, 1997–2024. Seasonal indices are normalised to 1 as the yearly mean; axis tick marks indicate index values.

3.2. Analytical Framework

3.2.1. Seasonal Decomposition Using X-13ARIMA-SEATS (U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, USA)

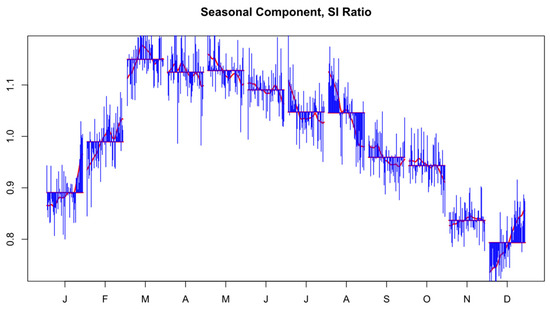

To isolate and analyze the seasonal components, the study employs the X-13ARIMA-SEATS methodology (Figure 2), a widely used time-series decomposition technique developed by the U.S. Census Bureau. This method decomposes each time series into three components:

where represents Trend-cycle, representing long-term movements; is seasonal component, capturing predictable intra-year fluctuations and represents the irregular component, accounting for random noise.

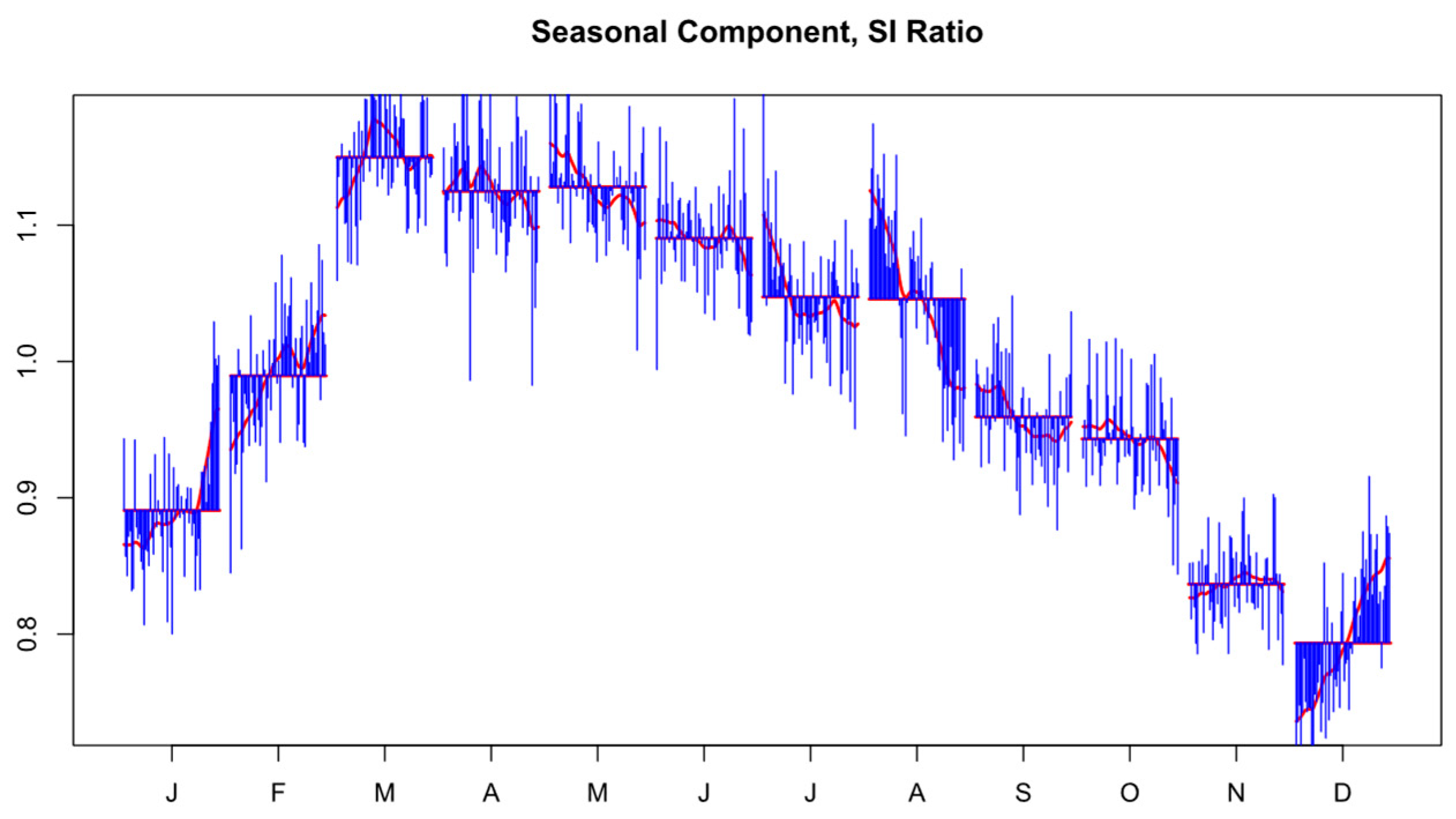

Figure 2.

Example of Seasonal Component.

By separating these components, the method ensures a structured understanding of the cyclical patterns in the housing market. The X-13ARIMA-SEATS process involves several key steps, including pre-adjustment to remove outliers and calendar effects, fitting a Seasonal Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average (SARIMA) model, and performing diagnostic checks such as the Ljung-Box Q-test to confirm the randomness of residuals [21]. This decomposition enables the study to distinguish real seasonality from random noise effectively.

For each series, X-13ARIMA-SEATS is implemented through an underlying regARIMA model. In line with standard practice, we use the built-in automatic model selection procedure of X-13ARIMA-SEATS to choose the SARIMA specification ARIMA(p, d, q)(P, D, Q)12. The procedure evaluates a set of candidate models using information criteria and residual diagnostics and selects the specification that provides an adequate fit while avoiding over-parameterisation. To enhance transparency and reproducibility, Appendix Table A1 reports the selected SARIMA orders (p, d, q, P, D, Q) for all series used in the seasonal decomposition. The regARIMA models and the X-13ARIMA-SEATS specifications are estimated using the seasonal package in R, which provides a direct interface to the official U.S. Census Bureau X-13ARIMA-SEATS program.

We rely on the X-13ARIMA-SEATS procedure for seasonal decomposition for three main reasons. First, X-13ARIMA-SEATS is the standard method used by official statistical agencies, including the U.S. Census Bureau, for seasonal adjustment of monthly and quarterly economic indicators. It combines the classical X-11 filters with ARIMA modelling and SEATS signal extraction, allowing for the joint treatment of trading-day effects, moving holidays and outliers within a regARIMA framework. This makes it particularly well suited for macroeconomic series such as house prices and inventory, where calendar effects and shocks are non-negligible. Second, the method produces additive decompositions with interpretable seasonal indices that are directly comparable to the seasonal factors published by the Census Bureau, which is important for aligning our results with existing practice and policy-oriented applications. Third, X-13ARIMA-SEATS is implemented in widely used open-source software (e.g., the seasonal package in R), which facilitates replication and transparency of our analysis.

Alternative decomposition techniques, such as STL (Seasonal-Trend decomposition using Loess) and state-space or unobserved components models, could also be applied. STL provides a highly flexible, nonparametric decomposition that is robust to certain types of outliers and allows the seasonal component to evolve smoothly over time, but it does not incorporate an explicit stochastic model for the series and is less tightly linked to standard forecasting frameworks. State-space and unobserved components models offer a unified probabilistic representation of trend, cycle and seasonality, but require stronger modelling assumptions and a more complex estimation setup, which would substantially increase the computational and expositional burden of our multi-series, multi-region analysis. In this paper we therefore prioritise the X-13ARIMA-SEATS approach, which strikes a balance between flexibility, interpretability and comparability with official housing statistics, and we view extensions based on STL or state-space models as a promising avenue for future research.

Before seasonal decomposition, all HPI series are transformed using the natural logarithm. Preliminary unit-root diagnostics on the log-level series indicate that they behave as integrated processes with seasonal components, which is consistent with the behaviour of many macroeconomic price indices. In the X-13ARIMA-SEATS framework, non-stationarity is handled by the regARIMA component through appropriate differencing. We therefore allow the automatic model-selection routine to choose SARIMA specifications of the form ARIMA(p, d, q)(P, D, Q)12, so that both non-seasonal (d) and seasonal (D) differences are estimated as needed. For all series used in this paper, the selected models include one non-seasonal and one seasonal difference, i.e., ARIMA(p, 1, q)(P, 1, Q)12; the exact specifications for each Census division and for the national series are reported in Appendix Table A1. X-13ARIMA-SEATS residual diagnostics, including Ljung–Box tests for residual autocorrelation and spectral tests for residual seasonality, do not indicate remaining non-stationarity after differencing, suggesting that the extracted seasonal components are based on well-behaved stationary errors.

3.2.2. Statistical Tests for Seasonality

To formally validate the presence and significance of seasonality, this study employs multiple statistical tests. The parametric F-test is used to assess whether monthly variations in housing prices and sales turnover are statistically significant. This test evaluates the null hypothesis that all monthly means are equal, with a significant F-statistic indicating strong seasonality. To account for potential non-normality in the data, the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test is also employed. This test ranks observations across months and evaluates whether distributions differ significantly without assuming normality. Additionally, a two-way ANOVA is conducted to examine interactions between months (seasonal effects) and years (long-term trends), providing insights into whether seasonal patterns evolve over time. The study also applies a Bai–Perron multiple structural break test (Section 3.2.4) to detect structural breaks in seasonality. This procedure generalises the classical Chow test and allows for multiple unknown break dates. This test identifies whether key economic events, such as the 2008 financial crisis or the COVID-19 pandemic, have caused significant shifts in the seasonal structure of the housing market.

3.2.3. Regression Analysis for Regional Variations

To quantify regional differences in seasonal patterns, we estimate a panel regression model using region fixed effects and interactions between the seasonal index and regional indicators. The dependent variable is the non-seasonally adjusted House Price Index (HPI) for region i in month t. The key explanatory variable is the seasonal index SI_t obtained from the X-13ARIMA-SEATS decomposition, which captures the intensity of seasonal fluctuations at each point in time. The baseline specification is given by:

where denotes the non-seasonally adjusted HPI in region at time t, is the common seasonal index, Region_ir is a set of regional dummy variables that equals 1 if region belongs to Census division r and 0 otherwise (with one division omitted as the reference category), and ε_it is the idiosyncratic error term. The coefficients capture time-invariant differences in average price levels across regions, while the interaction terms measure how the effect of on differs across regions relative to the reference division.

Regional dummies are operationalized at the level of U.S. Census divisions. Specifically, we construct a set of binary indicators for each division (e.g., New England, Middle Atlantic, East North Central, etc.), omitting one division as the reference group to avoid perfect multicollinearity. The inclusion of this full set of division dummies is equivalent to estimating a model with region fixed effects, allowing us to control for unobserved, time-invariant regional characteristics such as climate, long-run housing stock, and structural differences in price levels. For brevity, Table 2 reports only the coefficients on the interaction terms; the regional dummy coefficients are included in the estimation but omitted from the table.

Table 2.

Regression results.

Model fit is assessed using the coefficient of determination (R2) and information criteria, namely the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). For the baseline specification, the model achieves a multiple R2 of 0.190 and an adjusted R2 of 0.187, with an overall F-statistic of 49.87 on 19 and 4030 degrees of freedom (p < 0.001). The corresponding information criteria are AIC = 47181.1 and BIC = 47313.5, indicating that the regressors are jointly highly significant and that the specification provides a reasonable fit to the data. These statistics are also reported in Table 2.

Although our main regressions are specified at the level of Census divisions, which represent relatively large and heterogeneous regions, spatial dependence across neighbouring divisions could still be a concern. To assess this, we computed a global Moran’s I statistic on the region-level regression residuals using a contiguity-based row-standardised spatial weights matrix, in which adjacent Census divisions are assigned positive weights and non-adjacent divisions receive zero weight. The resulting Moran’s I statistic is I = −0.64, with an expected value of −0.125 under spatial randomness and a p-value of 0.97 for the test of positive spatial autocorrelation, indicating no evidence of residual spatial clustering at the division level. Given the small cross-sectional dimension and the absence of strong residual spatial dependence, we do not estimate more complex spatial autoregressive models and instead focus on the fixed-effects panel regression framework.

3.2.4. Structural Break Analysis

To examine whether the seasonal component of the U.S. housing market exhibits structural breaks over time, we apply a Bai–Perron multiple structural break test, which generalizes the classical Chow test. Specifically, we estimate a piecewise-constant mean model for the aggregate seasonal index obtained from the X-13ARIMA-SEATS decomposition,

where denotes the regime-specific mean in segment , is an error term, and are the unknown break dates to be estimated. We allow up to five potential breaks (m_max = 5) and select the number of breaks using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The breakpoints are estimated using the breakpoints() function from the strucchange package in R.

To formally test the null hypothesis of no structural break (m = 0) against the alternative of at least one break (m ≥ 1), we compute a sequence of Chow-type F-statistics using the Fstats() function and apply the supF test via sctest(). The resulting statistic is supF = 783.71 with p-value < 0.001, which strongly rejects the null of a stable seasonal pattern over the sample period. See Appendix Table A2 for the full set of partitions.

4. Results

4.1. Evidence of Seasonality

The analysis reveals clear and significant seasonal patterns in the U.S. housing market. Using the X-13ARIMA-SEATS methodology, distinct cyclical components were identified in key market indicators, including the Housing Price Index (HPI), the number of houses sold, and the inventory of houses for sale.

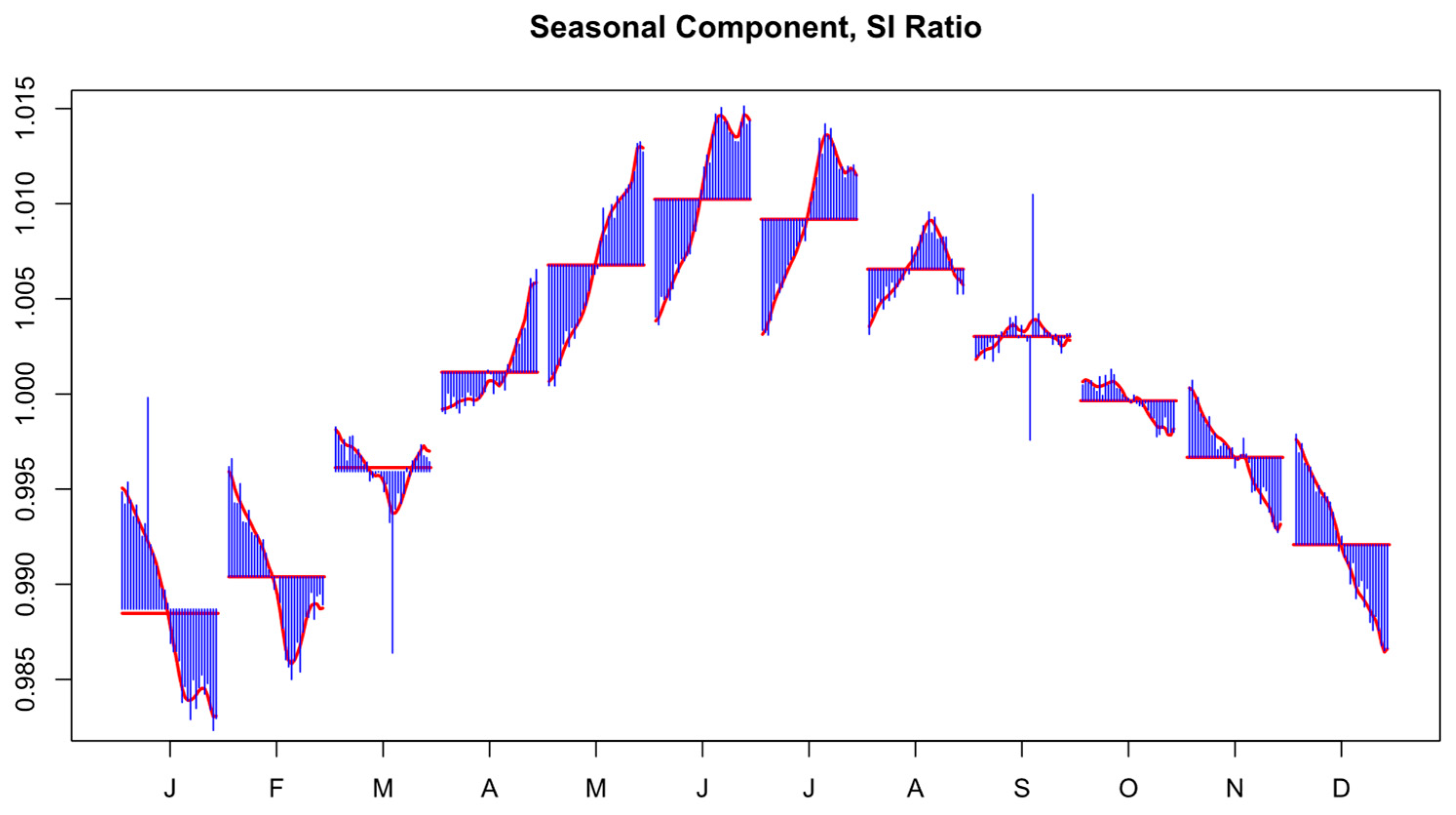

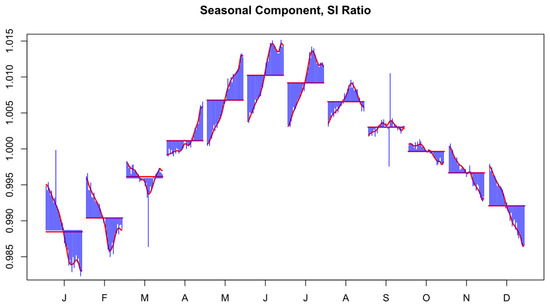

Figure 3 illustrates the seasonal component of the HPI. Prices exhibit predictable fluctuations, with peaks consistently occurring during the summer months (June–August) and troughs during the winter months (December–February). The seasonal index for the HPI remains above 1.005 from April to August, reflecting increased market activity during these months, while it falls below 0.995 in December and January, indicating a slowdown in market activity.

Figure 3.

Seasonal Component of the Housing Price Index.

Similarly, the seasonal components of “Houses Sold” and “Houses for Sale” show analogous patterns. Transaction volumes rise sharply from early spring and peak in the summer before declining steadily in the fall and reaching their lowest levels in winter. Inventory levels follow a similar seasonal trajectory, with higher availability in spring and summer and reduced supply during winter months. These findings underline the existence of strong seasonality across multiple dimensions of the housing market.

4.2. Statistical Validation of Seasonality

To formally validate the observed seasonality, several statistical tests were conducted. As reported in Table 3, the F-test results demonstrate significant monthly variations across all key variables. For instance, the F-statistic for the HPI is 61.63 (p < 0.001), indicating substantial differences in monthly means. This confirms that housing prices are not uniformly distributed throughout the year, but instead follow a systematic seasonal pattern.

Table 3.

Statistical results.

The Kruskal–Wallis test, a nonparametric alternative to the F-test, further corroborates these findings. With a test statistic of 311.91 (p < 0.001), the Kruskal–Wallis test confirms that the monthly distributions of housing prices and transaction volumes differ significantly. Importantly, this test does not assume normality in the data, making it particularly robust for variables like “Houses Sold,” which may be affected by outliers or non-normal distributions.

The results of a two-way ANOVA provide additional insights. Both the main effects of Month (p < 0.001) and Year (p < 0.001) are statistically significant, indicating that seasonal patterns persist across years but vary in magnitude. Furthermore, the significant Month × Year interaction term (p < 0.001) suggests that the intensity and timing of seasonal fluctuations have evolved over time, as detailed in the next section.

4.3. Evolution of Seasonal Patterns

The analysis indicates a notable shift in the timing and intensity of seasonal patterns in recent years. Figure 1 highlights changes in the seasonal peaks and troughs for housing sales activity. Historically, the peak in housing sales occurred in May or June. However, in the post-2020 period, this peak has shifted to earlier months, such as March and April. Similarly, inventory recovery, which traditionally began in March, now starts as early as January or February.

The variable “Months’ Supply” provides further evidence of these shifting patterns. Figure 1 shows that the peak inventory levels, which historically occurred in December, have moved to October or November in recent years. These findings suggest that the seasonal cycle of the U.S. housing market is gradually shifting forward, potentially reflecting changes in consumer behaviour, macroeconomic conditions, or market dynamics following the COVID-19 pandemic.

4.4. Regional Variations in Seasonality

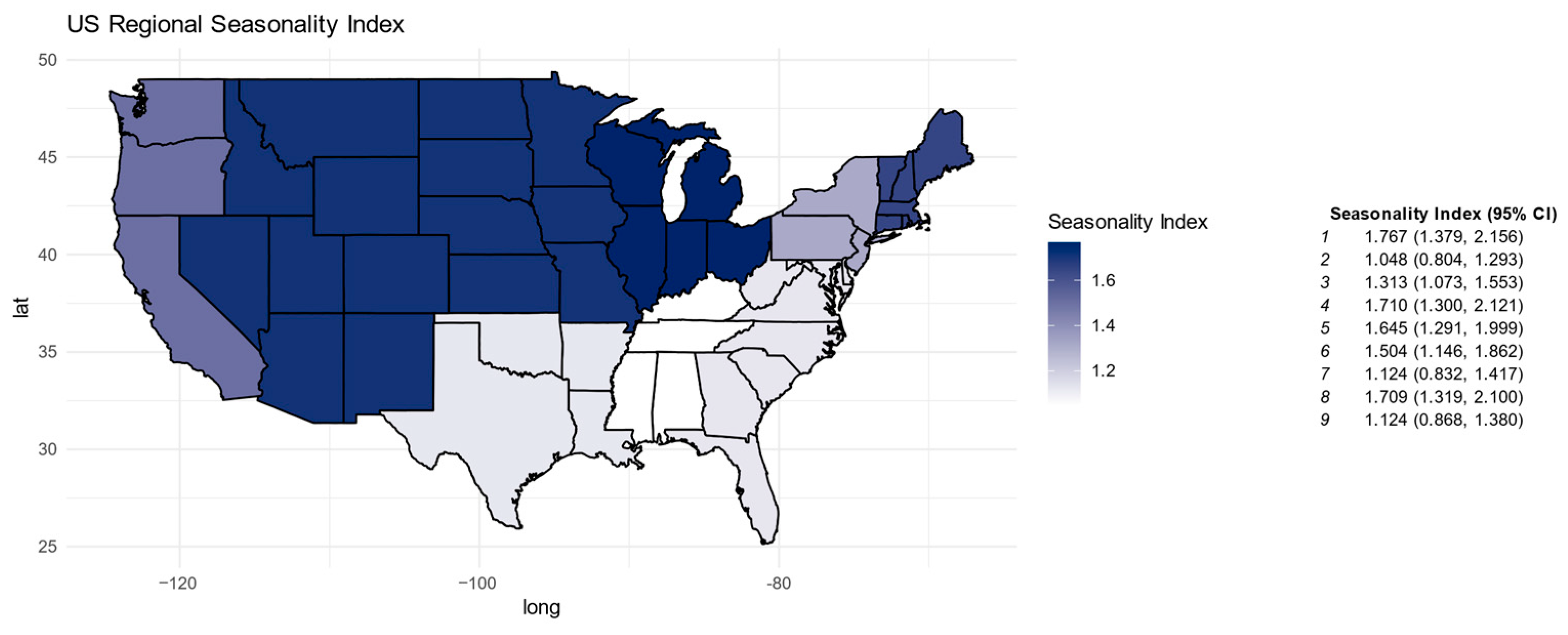

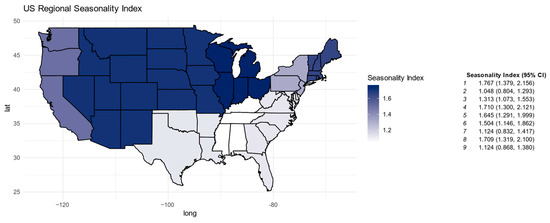

As shown in Figure 4, the 95% confidence intervals around the regional seasonality indices are relatively narrow, indicating that the ranking of regions by seasonal intensity is robust over time. The Northeast and Midwest exhibit the most pronounced seasonal fluctuations, with sharper declines in housing activity during the winter months. These regions experience harsher weather conditions, which likely discourage transactions and limit construction activity during colder months.

Figure 4.

Regional variation in the intensity of housing market seasonality in the HPI by Census division.

In contrast, the South and West regions demonstrate relatively weaker seasonality. The milder climates in these areas allow for year-round construction and market activity, reducing the amplitude of seasonal fluctuations. For example, in the South Atlantic region, housing prices and sales volumes show a smaller seasonal drop during winter compared to the Northeast or Midwest.

Regression analysis confirms these regional differences. The interaction term between Seasonality and Region is significant (p < 0.001), indicating that the impact of seasonality on housing prices varies geographically. For instance, the South Atlantic region shows a positive interaction effect, suggesting that seasonal dynamics amplify price increases more strongly in this region compared to the national average. Conversely, the West North Central region exhibits a negative interaction effect, indicating weaker seasonal impacts on housing prices.

To make these patterns more transparent, Table 4 summarises the timing and amplitude of the seasonal peak in the HPI before and after the pandemic for each Census division and for the United States as a whole. For each region and period (1991–2019 vs. 2020–2024), we identify the calendar month with the highest average seasonal index and compute its percentage deviation from the yearly mean. At the national level, the peak remains in June, but its amplitude increases from 1.6% to 2.3%, indicating a more pronounced early-summer “hot season”. Most regions also experience stronger peaks in the post-pandemic period, with increases in peak seasonal indices of around 0.6–0.9 percentage points. In several colder divisions (Mountain, Pacific, West North Central), the peak shifts from June or July to May, while in East South Central it moves from June to July. Overall, Table 4 shows both an intensification of seasonal peaks and a tendency for the hottest part of the year to occur earlier in many colder regions.

Table 4.

Timing and amplitude of seasonal peaks in the HPI by region.

4.5. Robustness of Results

The robustness of the results was evaluated using a series of sensitivity analyses and diagnostic tests to ensure the findings are reliable and not influenced by data anomalies, model misspecification, or structural changes in the housing market.

To determine whether outliers in housing price data influenced the regression results, observations in the top and bottom 1% of the Housing Price Index (HPI) distribution were excluded, and the models were re-estimated using the truncated dataset. This analysis revealed that the exclusion of extreme observations had no substantive impact on the findings. Key coefficients, such as the seasonal effect for July and January, changed only marginally. For example, the coefficient for July decreased slightly from 0.062 (p < 0.001) to 0.061 (p < 0.001), while the coefficient for January changed from −0.058 (p < 0.001) to −0.057 (p < 0.001). Similarly, regional effects, such as the premium for the Pacific region, remained stable at approximately 0.198. These results confirm that the findings are not driven by extreme observations and reflect broader trends in the housing market.

In addition, residual diagnostics were conducted to evaluate whether the regression model met the assumptions of linear regression, including homoscedasticity, normality, and the absence of autocorrelation. The Breusch-Pagan test for heteroscedasticity yielded a p-value of 0.21, indicating no evidence of heteroscedasticity. The Shapiro-Wilk test for normality returned a p-value of 0.13, suggesting that the residuals approximate a normal distribution. In addition, the Ljung-Box Q-test for autocorrelation showed no significant results (p > 0.10), confirming that residuals are uncorrelated over time. Visual diagnostic tools, including autocorrelation function (ACF) plots, histograms of residuals, and Q-Q plots, visually supported these findings by showing no significant deviations from normality or randomness. Collectively, these results affirm that the regression model satisfies the assumptions necessary for valid statistical inference.

5. Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of seasonal dynamics and regional heterogeneity in the U.S. housing market, with a particular focus on post-pandemic shifts. By leveraging data from 1991 to 2024 and employing advanced statistical techniques such as X-13ARIMA-SEATS decomposition, the findings reveal significant changes in the timing and intensity of seasonality as well as pronounced regional variations.

This study reveals that while seasonality remains a prominent feature of the U.S. housing market, its patterns have undergone significant shifts in the post-pandemic period. The findings indicate that the timing of seasonal peaks has advanced, with housing market activity now reaching its zenith as early as March or April, compared to the traditional peak in May or June. This shift aligns with observations by [22], who documented accelerated seasonal cycles and amplified fluctuations in housing prices and sales volumes since the pandemic. These changes are likely driven by a combination of altered consumer behaviour, technological adoption facilitating year-round transactions, and lingering macroeconomic adjustments. This evidence challenges the assumption of stable seasonality in traditional housing market models and highlights the need for adaptive frameworks.

Regional heterogeneity emerges as a critical dimension of housing market seasonality. Colder regions, such as the Northeast and Midwest, exhibit more pronounced seasonal variations, with sharper declines in market activity during winter months. This finding corroborates the work of Mahmud et al. [23], who attributed these pronounced fluctuations to adverse weather conditions that limit transactions and construction activity. In contrast, warmer regions, such as the South Atlantic and Pacific Coast, display milder seasonal swings, reflecting year-round market participation. These results extend prior research by providing a detailed comparative analysis of seasonal dynamics across regions, emphasizing how geographic and climatic factors shape local housing cycles.

The forward shift in seasonal peaks observed in this study also reflects structural changes in market behaviour. Historically, the “spring boom” in housing activity was closely tied to school calendars and weather-driven preferences. However, the earlier onset of peak activity suggests that these traditional drivers may now be complemented by new factors, such as heightened buyer urgency and changing migration patterns. This shift aligns with Moser et al.’s [24] findings on increased demand for larger homes in suburban areas during the pandemic, as remote work enabled greater geographic flexibility. By shifting the timing of demand, these behavioural changes may have permanently altered the seasonal rhythm of the housing market. The quantitative evidence in Table 4 reinforces this interpretation. Before the pandemic, most divisions exhibited peak seasonal effects in June or July with relatively moderate amplitudes, whereas after 2020 the peaks are stronger and, in several colder regions, occur earlier in the calendar year. This combination of earlier and more concentrated peak activity suggests that households and market participants face tighter conditions in late spring and early summer, particularly in colder regions, while warmer regions show more modest adjustments in both timing and amplitude.

Additionally, the study confirms the self-reinforcing nature of the “thick-market effect,” as described by Hattapoglu and Hoxha [20]. During peak months, higher buyer density contributes to increased bargaining power for sellers, driving both prices and transaction volumes upward. However, the findings suggest that this effect is now more pronounced in certain regions, such as the South Atlantic, where seasonal price increases significantly exceed the national average. This regional amplification of the thick-market effect underscores the importance of understanding local market dynamics, as a national-level analysis may obscure critical geographic differences.

The study also highlights the limitations of traditional seasonal adjustment models, such as X-12 and X-13ARIMA-SEATS, when applied to post-pandemic housing data. These models assume relatively stable seasonal amplitudes and timing, which may not accurately capture the amplified fluctuations and forward shifts observed in recent years. For example, Mahmud et al. [23] noted that these models often under-correct for intensified seasonal peaks, leading to overestimation of off-season activity. The present study reinforces this critique by demonstrating that unadjusted seasonal components provide a clearer picture of housing market dynamics, particularly in regions with strong climatic effects.

In comparing these results to pre-pandemic studies, it is evident that the resilience of seasonality has persisted despite external disruptions. Earlier works, such as Novy-Marx [14], emphasized the stability of seasonal cycles as a core feature of housing markets. However, the current findings suggest that while the underlying seasonal structure remains intact, its expression has evolved in both timing and intensity. This evolution highlights the adaptability of housing markets to external shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and underscores the importance of continuously monitoring these dynamics to inform both policy and practice.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that seasonality remains a defining feature of the U.S. housing market, yet its nature is evolving. Using data from 1991 to 2024, the analysis confirms the persistence of the spring/summer boom and winter slowdown, while highlighting shifts in the timing and intensity of these patterns. Notably, seasonal peaks appear to have shifted earlier, with evidence suggesting that March and April are increasingly critical months in many markets. Regional heterogeneity further underscores the dynamic nature of seasonality, as colder regions exhibit more pronounced seasonal swings compared to milder climates.

These findings carry important implications for market participants and policymakers. First, timing strategies for buyers and sellers must adapt to the shifting seasonal window. Sellers aiming to capitalize on peak demand may need to list earlier in the year, while buyers seeking competitive opportunities may benefit from entering the market before traditional peaks. For example, in colder regions, listing in May rather than July can attract significantly more traffic. Second, policymakers and analysts should recalibrate seasonal adjustment models to account for these changes. Outdated adjustment methods may misinterpret trends, understating spring price growth or overstating summer slowdowns. Recognizing regional diversity in seasonality can also improve policy targeting, such as adjusting the timing of initiatives to address housing supply shortages or managing loan demand surges during seasonal peaks.

Despite external disruptions such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the resilience of seasonality highlights its importance in housing market dynamics. However, stakeholders should be cautious about potential market instabilities. If widespread behaviour shifts occur in response to perceived seasonal changes, such as earlier buying or selling, it could amplify booms or slumps. Continuous monitoring of seasonal trends, along with research into micro-level behavioural changes, remains essential to understanding and mitigating these risks.

7. Limitations and Future Work

While this study provides valuable insights into the evolving nature of housing market seasonality, it is subject to several limitations. First, the analysis relies on regional aggregate data, which may mask finer local variations. Future research could focus on metropolitan-level or property-level data to uncover sharper idiosyncrasies, such as whether individual homes now achieve higher premiums in March compared to a decade ago.

Second, the methodological approach, based on X-13ARIMA-SEATS and classical statistical tests, assumes relatively smooth and stable seasonal patterns. This might overlook nonlinear or short-term fluctuations, particularly during periods of significant economic or policy shifts. Advanced time-varying parameter models, such as state-space approaches, could better capture gradual or abrupt changes in seasonality over time.

Third, the study primarily focuses on the for-sale housing market, without explicitly addressing seasonality in rental or commercial real estate markets. Given that sectors like apartment rentals exhibit distinct seasonal turnover patterns, future research could explore the interaction between rental and for-sale markets to provide a more comprehensive understanding of housing dynamics.

Lastly, while the study identifies shifts in seasonality and their potential drivers, it does not quantitatively model these factors. The role of school calendars, credit conditions, and demographic trends, among other factors, could be formally tested using structural models, such as equilibrium frameworks incorporating seasonally varying search intensity (e.g., Ngai & Tenreyro [25]). These extensions would enable a deeper exploration of the underlying mechanisms driving seasonal changes, enriching the understanding of housing market seasonality in a rapidly evolving environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H. (Yihan Hu); methodology, Y.H. (Yihan Hu); software, Y.H. (Yihan Hu); validation, Y.H. (Yihan Hu) and Y.H. (Yifei Huang); formal analysis, Y.H. (Yihan Hu); investigation, Y.H. (Yihan Hu); resources, Y.H. (Yihan Hu); data curation, Y.H. (Yihan Hu); writing—original draft preparation, Y.H. (Yihan Hu); writing—review and editing, Y.H. (Yihan Hu) and Y.H. (Yifei Huang); visualization, Y.H. (Yihan Hu); supervision, Y.H. (Yihan Hu); project administration, Y.H. (Yihan Hu). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/sipp/data/datasets.html, accessed on 2 December 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Selected ARIMA(p,d,q) specifications for X-13ARIMA-SEATS.

Table A1.

Selected ARIMA(p,d,q) specifications for X-13ARIMA-SEATS.

| Region (Census Division) | ARIMA Specification | Observations | Transform |

|---|---|---|---|

| East North Central (NSA) | (0 2 1)(0 1 1) | 405 | log |

| East South Central (NSA) | (3 1 1)(0 1 1) | 405 | log |

| Middle Atlantic (NSA) | (3 1 1)(0 1 0) | 405 | log |

| Mountain (NSA) | (1 1 1)(0 1 1) | 405 | log |

| New England (NSA) | (1 2 1)(0 1 1) | 405 | log |

| Pacific (NSA) | (1 2 1)(0 1 1) | 405 | log |

| South Atlantic (NSA) | (0 2 1)(0 1 1) | 405 | log |

| West North Central (NSA) | (1 2 1)(0 1 1) | 405 | log |

| West South Central (NSA) | (1 1 2)(0 1 1) | 405 | log |

| USA (NSA) | (2 1 1)(0 1 1) | 405 | log |

Note: All models are estimated using the X-13ARIMA-SEATS procedure via the seasonal package in R. Transform denotes the transformation applied prior to estimation (log).

Table A2.

Bai–Perron multiple structural break test for the seasonal index (optimal m+1 partitions).

Table A2.

Bai–Perron multiple structural break test for the seasonal index (optimal m+1 partitions).

| m | Breakdate1 | Breakdate2 | Breakdate3 | Breakdate4 | Breakdate5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2009(2) | ||||

| 2 | 2009(6) | 2017(9) | |||

| 3 | 2004(1) | 2009(1) | 2017(10) | ||

| 4 | 2004(2) | 2009(2) | 2014(9) | 2019(9) | |

| 5 | 1999(2) | 2004(2) | 2009(2) | 2014(9) | 2019(9) |

Note. HPI data, 1991–2024.

References

- Gourley, P. Curb appeal: How temporary weather patterns affect house prices. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2021, 67, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seagraves, P. Real Estate Insights: Is the AI revolution a real estate boon or bane? J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2023, 42, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpezzi, S. Housing affordability and responses during times of stress: A preliminary look during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contemp. Econ. Policy 2023, 41, 9–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Feng, M.; Qiu, J.; Gu, J.; Zhao, J. From news to forecast: Integrating event analysis in llm-based time series forecasting with reflection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 58118–58153. [Google Scholar]

- Kuepers, W.; Wasieleski, D.M.; Schumacher, G. Temporality and ethics: Timeliness of ethical perspectives on temporality in times of crisis. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 188, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. Rebuilding the economy from the Covid crisis: Time to rethink regional studies? Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2021, 8, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Prybutok, V.; Sangana, V.K.R. Environmental implications of drone-based delivery systems: A structured literature review. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton-Jones, A.; Butler, B.S.; Scott, S.V.; Xu, S.X. Examining assumptions: Provocations on the nature, impact, and implications of is theory. MIS Q. 2021, 45, 453–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, H. Integration and risk transmission across supply, demand, and prices in China’s housing market. Econ. Change Restruct. 2024, 57, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røed Larsen, E. House price seasonality, market activity, and the December discount. Real Estate Econ. 2024, 52, 110–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frącz, P.; Dąbrowski, I.; Wotzka, D.; Zmarzły, D.; Mach, Ł. Identification of differences in the seasonality of the developer and individual housing market as a basis for its sustainable development. Buildings 2023, 13, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etukudor, C.; Couraud, B.; Robu, V.; Früh, W.G.; Flynn, D.; Okereke, C. Automated negotiation for peer-to-peer electricity trading in local energy markets. Energies 2020, 13, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, T.; Reed, T. Relationships on the rocks: Contract evolution in a market for ice. Am. Econ. J. Microecon. 2022, 14, 330–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novy-Marx, R. Hot and cold markets. Real Estate Econ. 2009, 37, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, J.; Li, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, D.; Huang, Z.; Yang, K. The role of seasonality in the spread of COVID-19 pandemic. Environ. Res. 2021, 195, 110874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, D.E.; Smith, M.D.; Williams, Z.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Landry, C.E. Policy and market forces delay real estate price declines on the US coast. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, R.A.; Bianchi, M.V.; Booten, C.; Vidal, J.; Jackson, R. Modulating thermal load through lightweight residential building walls using thermal energy storage and controlled precooling strategy. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 180, 115870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P.R.; Rhodes, J.D.; Wilson, E.J.; Webber, M.E. Quantifying the impact of residential space heating electrification on the Texas electric grid. Appl. Energy 2021, 298, 117113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budikova, D.; Ford, T.W.; Wright, J.D. Characterizing winter season severity in the Midwest United States, part II: Interannual variability. Int. J. Climatol. 2022, 42, 3499–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattapoglu, M.; Hoxha, I. Hot and cold seasons in Texas housing markets. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2021, 14, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, F.; Guerrero, V.M.; López-Pérez, J. The finite sample performance of two methods for choosing a power transformation when seasonally adjusting a time series with X-13ARIMA-SEATS. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2024, 53, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duca, J.V.; Hoesli, M.; Montezuma, J. The resilience and realignment of house prices in the era of Covid-19. J. Eur. Real Estate Res. 2021, 14, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, A.T.; Ogunlana, S.O.; Hong, W.T. Key driving factors of cost overrun in highway infrastructure projects in Nigeria: A context-based perspective. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2021, 19, 1530–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, J.; Wenner, F.; Thierstein, A. Working from home and Covid-19: Where could residents move to? Urban Plan. 2022, 7, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, L.R.; Tenreyro, S. Hot and cold seasons in the housing market. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 3991–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).