First Record of Bramatherium Falconer, 1845 (Mammalia: Giraffidae) from the Late Miocene of Greece and the Helladotherium-Bramatherium Debate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

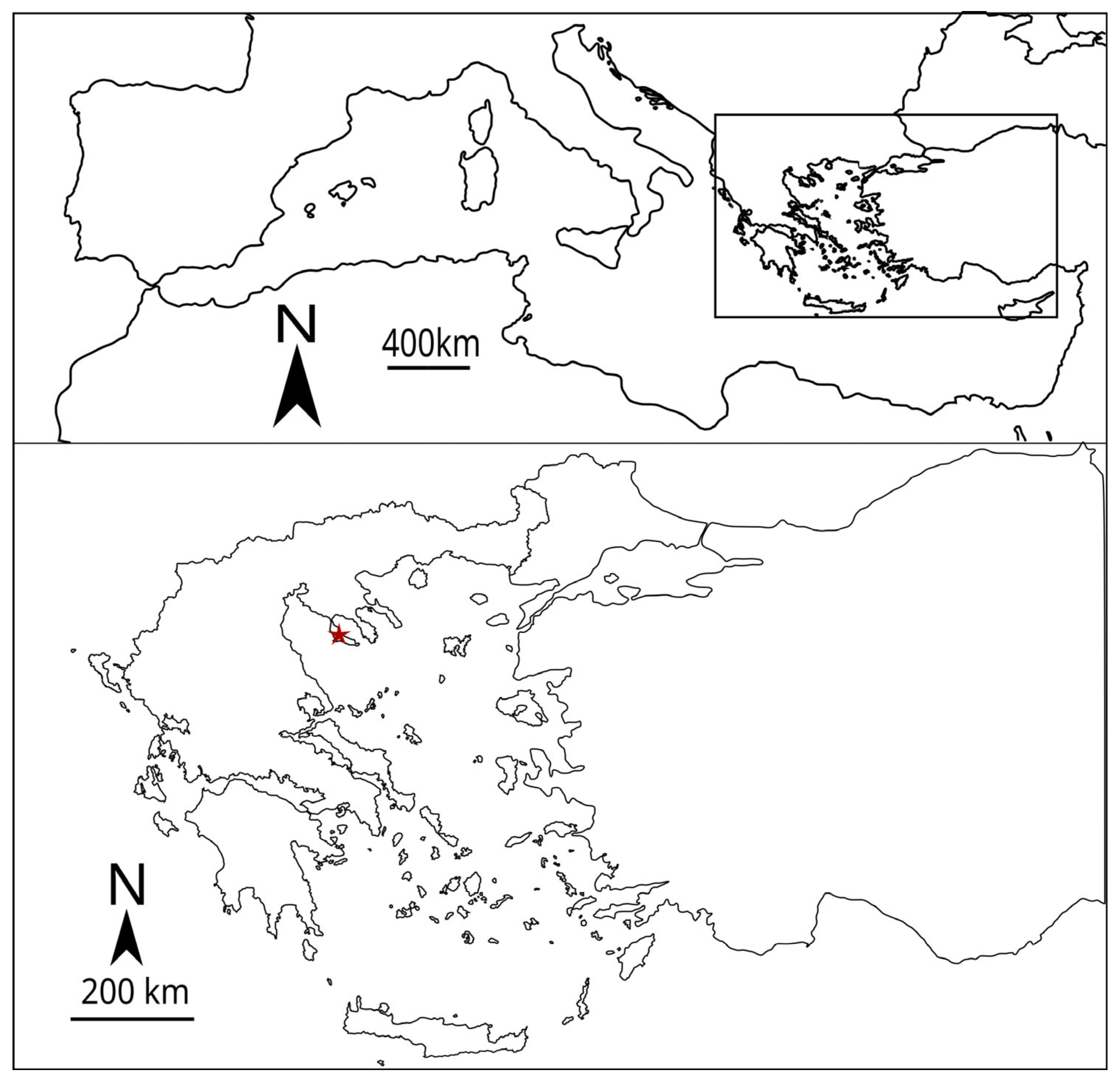

2.1. Geological and Chronological Setting

2.2. Studied Material and Phylogenetic Analysis and Comparison

2.3. Museum Abbreviations

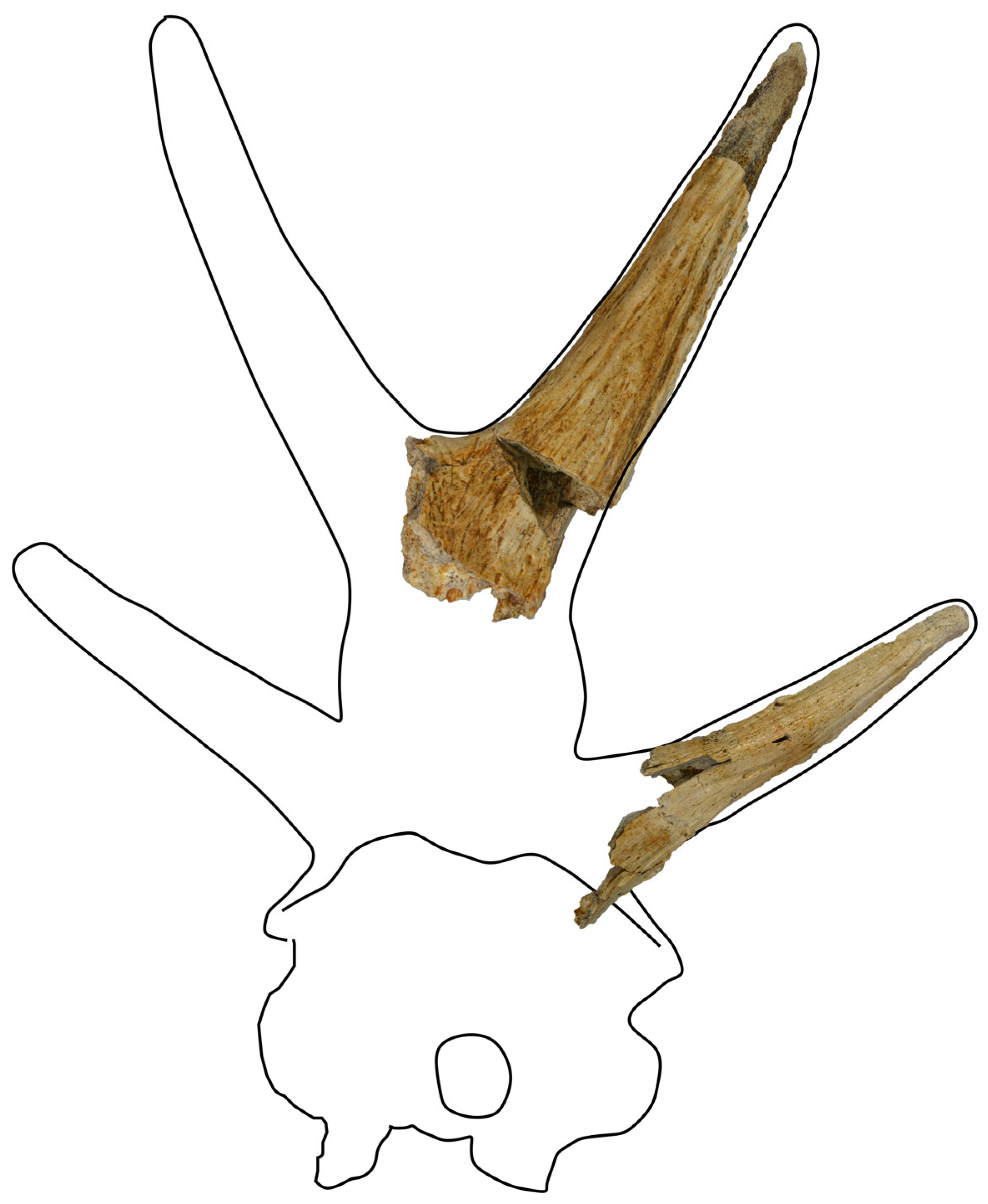

3. Results

3.1. Systematic Paleontology

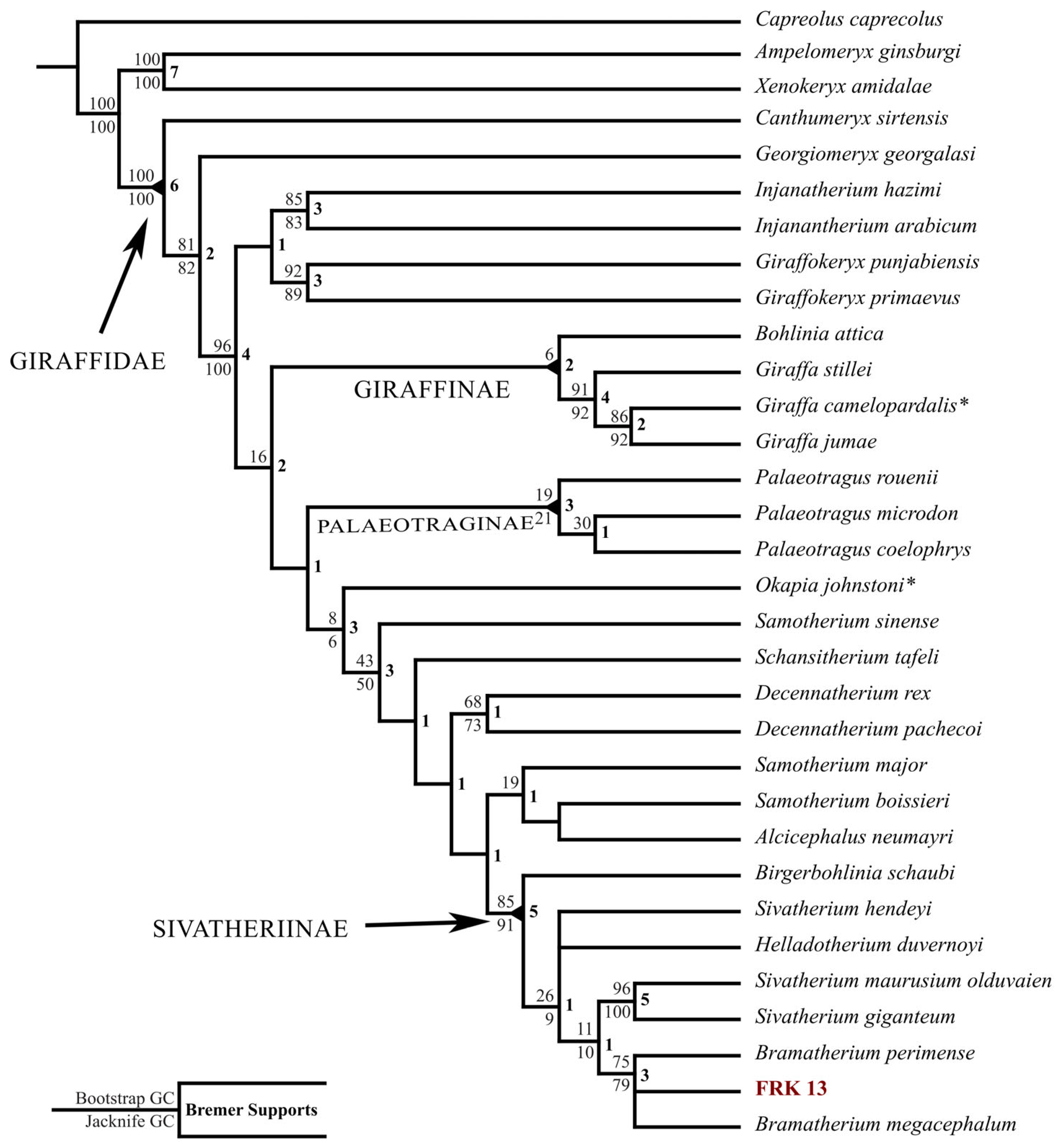

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

4. Discussion

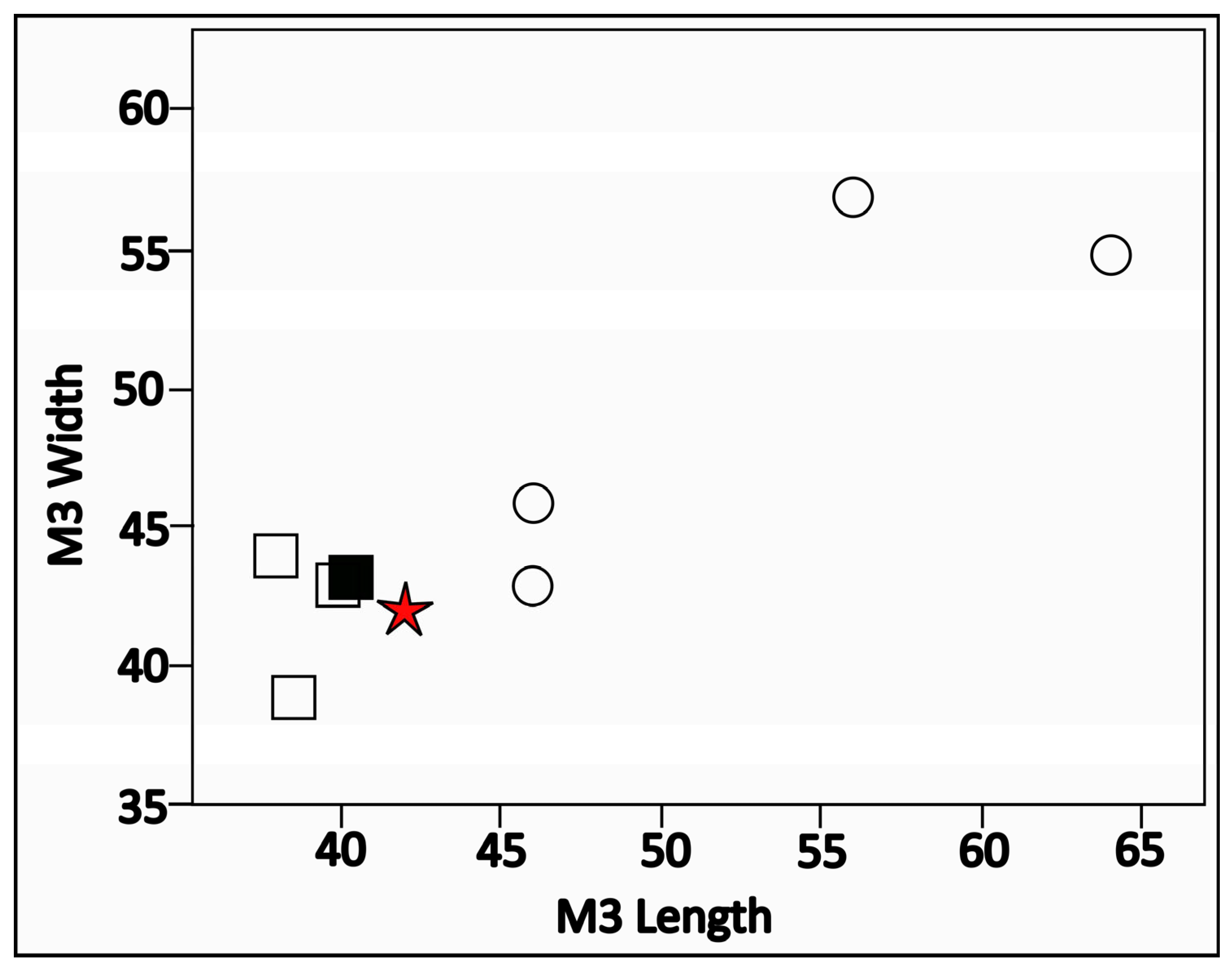

4.1. Systematics of Bramatherium and the Assignment of FRK-13

4.2. Paleobiogeography of Bramatherium

4.3. Is Helladotherium a Female Bramatherium?

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamilton, W.R. Fossils giraffes from the Miocene of Africa and a revision of the phylogeny of the Giraffoidea. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1978, B283, 165–229. [Google Scholar]

- Geraads, D. Remarques sur la systématique et la phylogénie des Giraffidae (Artiodactyla, Mammalia). Geobios 1986, 19, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, P.; Morales, J. Birgerbohlinia schaubi Crusafont, 1952 (Giraffidae, Mammalia) del Turoliense inferior de Crevillente-2 (Alicante, España). Filogenia e historia biogeográfica de la subfamilia Sivatheriinae. Bull. Mus. Natl. Hist. Nat. Paris 1991, 13, 177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Danowitz, M.; Vasilyev, A.; Kortlandt, V.; Solounias, N. Fossil evidence and stages of elongation of the Giraffa camelopardalis neck. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2015, 2, 150393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, M.; Danowitz, M.; Solounias, N. First comprehensive morphological analysis on the metapodials of Giraffidae. Palaeontol. Electron. 2016, 19.3.50A, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, M.; Sánchez, I.M.; Morales, J. A new giraffid (Mammalia, Ruminantia, Pecora) from the Late Miocene of Spain, and the evolution of the sivathere-samothere lineage. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xafis, A.; Mayda, S.; Grímsson, F.; Nagel, D.; Kaya, T. Fossil Giraffidae (Mammalia, Artiodactyla) from the early Turolian of Kavakdere (Central Anatolia, Türkiye). Comptes Rendus Palevol 2019, 18, 619–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskos, K.; Kostopoulos, D.S. A review of Palaeogiraffa (Giraffidae, Mammalia) from the Vallesian of the Eastern Mediterranean. Geobios 2024, 84, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, M.; Abbas, S.G.; Khan, M.A.; Solounias, N. Distinction of Sivatherium from Libytherium and a new species of Libytherium (Giraffidae, Ruminantia, Mammalia) from the Siwaliks of Pakistan (Miocene). Geobios 2022, 74, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, T.; Yasin, R.; López-Torres, S.; Warburton, N.M.; Samiullah, K.; Ghaffar, A.; Khan, M.N.; Ara, C.; Muzaffar, E. New sivatheriine giraffid (Ruminantia, Mammalia) craniodental material from the Siwaliks of Pakistan. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2024, 44, e2376241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crusafont, M. Los jiráfidos fósiles de España. In Memorias y Comunicaciones del Instituto Geológico VIII: Premio Extraordinario de Doctorado; Diputación Provincial de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos, M.; Sánchez, I.M.; Morales, J. Comparative anatomy, phylogeny, and systematics of the Miocene giraffid Decennatherium pachecoi Crusafont, 1952 (Mammalia, Ruminantia, Pecora): State of the art. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2016, 36, e1187624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bonis, L.; Brunet, M.; Heintz, E.; Sen, S. La province Gréco-Irano-Afghane et la répartition des faunes mammaliennes au Miocène supérieur. Paleontol. Evol. 1992, 24–25, 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- de Bonis, L.; Bouvrain, G. Nouveaux Giraffidae du Miocène supérieur de Macédoine (Grèce). Adv. Vertebr. Paleontol. Hen Panta 2003, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, A.W. Ruminantia (Artiodactyla). In Geology and Paleontology of the Miocene Sinap Formation, Türkiye; Fortelius, M., Kappelman, J., Sen, S., Bernor, R., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 332–379. [Google Scholar]

- Geraads, D. Les Giraffidés du Miocène Supérieur de la Région de Thessalonique (Grèce). Unpublished. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Paris, Paris, France, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Geraads, D. Giraffidae (Mammalia) de la fin du Néogène de la République de Macédoine (ARYM). Geodiversitas 2009, 31, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulos, G. The Giraffidae (Mammalia, Artiodactyla) and the Study of the Histology and Chemistry of Fossil Mammal Bone from the Late Miocene of Kerassia (Euboea Island, Greece). Unpublished. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kostopoulos, D.S.; Koufos, G.D. The Late Miocene vertebrate locality of Perivolaki, Thessaly, Greece. 8. Giraffidae. Palaeontogr. Abt. 2006, A 276, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostopoulos, D.S. The Late Miocene mammal faunas of the Mytilinii Basin, Samos Island, Greece: New collection: 13. Giraffidae. In The Late Miocene Mammal Faunas of Samos; Koufos, G.D., Nagel, D., Eds.; Beiträge zur Paläontologie: Vienna, Austria, 2009; pp. 299–343. [Google Scholar]

- Kostopoulos, D.S. Palaeontology of the upper Miocene vertebrate localities of Nikiti (Chalkidiki Peninsula, Macedonia, Greece): Artiodactyla. Geobios 2016, 49, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridis, G. Study of the Late Miocene vertebrate locality of Kryopigi and other localities of Kassandra Peninsula, Chalkidiki (Greece). Systematics, Taphonomy, Paleoecology, Biochronology. Unpublished. Ph.D. Thesis, Scientific Annals of the School of Geology, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece, 2015. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Solounias, N.; Danowitz, M. The Giraffidae of Maragheh and the identification of a new species of Honanotherium. Palaeobiol. Palaeoenviron. 2016, 96, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xafis, A.; Tsoukala, E.; Solounias, N.; Mandic, O.; Harzhauser, M.; Grímsson, F.; Nagel, D. Fossil Giraffidae (Mammalia, Artiodactyla) from the late Miocene of Thermopigi (Macedonia, Greece). Palaeontol. Electron. 2019, 22.3.67, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, H. Description of some fossil remains of Dinotherium, Giraffe and other Mammalia, from the Gulf of Cambay, Western Coast of India, Chiefly from the collection presented by Captain Fulljames, of the Bombay Engineers, to the Museum of the Geological Society. Q. J. Geol. Soc. 1845, 1, 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbert, E.H. Siwalik Mammals in the American Museum of Natural History. Trans. Am. Philos. Soc. 1935, XXVI, 294–377. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, G.E. A new Bramatherium Skull. Am. J. Sci. 1939, 237, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welcomme, J.L.; Antoine, P.O.; Duranthon, F.; Mein, P.; Gingsburg, L. Nouvelles découvertes de Vertébrés miocènes dans le synclinal de Dera Bugti (Balouchistan, Pakistan). C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris. 1997, 325, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Akhtar, M.; Irum, A. Bramatherium (Artiodactyla, Ruminantia, Giraffidae) from the Middle Siwaliks of Hasnot, Pakistan: Biostratigraphy and palaeoecology. Turk. J. Earth Sci. 2014, 23, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Babar, M.A.; Ríos, M. New material of Bramatherium grande from the Siwaliks of Pakistan sheds light on dental intraclade morphological variability of Late Miocene sivatheres. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2021, 41, e1898976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, Y.; Hanta, R.; Jintasakul, P. Note on giraffe remains from the Miocene of continental Southeast Asia. J. Sci. Technol. MSL 2014, 33, 365–377. [Google Scholar]

- Danowitz, M.; Hou, S.; Mihlbachler, M.C.; Hastings, V.; Solounias, N. A combined-mesowear analysis of Late Miocene giraffids from North Chinese and Greek localities of the Pikermian Biome. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2016, 449, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whybrow, P.J.; Andrew, H.P. Fossil Vertebrates of Arabia: With Emphasis on the Late Miocene faunas, Geology, and Palaeoenvironments of the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos, M.; Danowitz, M.; Solounias, N. First identification of Decennatherium Crusafont, 1952 (Mammalia, Ruminantia, Pecora) in the Siwaliks of Pakistan. Geobios 2019, 57, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudry, A. Animaux fossiles du Mont Luberon (Vaucluse). Étude sur les vertébrés. F. Savy Editions; Biodiversity Heritage Library: Paris, France, 1873. [Google Scholar]

- Godina, A.Y. Istoricheskoe razvitie zhiraf. Rod Palaeotragus [Historical Development of Girrafids. Genus Palaeotragus]. Trudy 177; Akademia Nauk USSR, Paleontologicheskii Institut: Moscow, Russia, 1979. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kaakinen, A. NOW_20200330_all_Basins_combined_AK.xls. NOW Locality Basin Data Import 2020. Available online: https://nowdatabase.luomus.fi/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Ţibuleac, P.; Laskos, K.; Rӑţoi, B.-G.; Haiduc, B.S.; Merlan, V.; Ursachi, L. A link of the Late Miocene giraffid migration pathway from the peri-Aegean lands to the northeastern Eurasian areas. Geobios 2025, 88–89, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraads, D.; Güleç, E. A Bramatherium skull (Giraffidae, Mammalia) from the Late Miocene of Kavakdere (Central Türkiye) Biogeographic and phylogenetic implications. Bull. Miner. Res. Explor. 1999, 121, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Solounias, N.; Jukar, A.M. A Reassessment of Some Giraffidae Specimens from the Late Miocene Faunas of Eurasia. In Evolution of Cenozoic Land Mammal Faunas and Ecosystems; Casanovas-Vilar, I., van den Hoek Ostende, L., Janis, C.M., Saarinen, J., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Matthew, W.D. Critical observations upon Siwaliks mammals. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1929, LVI, 437–560. [Google Scholar]

- Arambourg, C. Precisions nouvelles sur Libytherium maurusium Pomel, giraffide du Villafranchien d’Afrique. Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 1960, S7-II, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendey, Q.B. Quaternary Vertebrate Fossil Sites in the South-Western Cape Province. S. Afr. Archaeol. Bull. 1969, 24, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.M. Pliocene Giraffoidea (Mammalia, Artiodactyla) from the Cape Province. Ann. S. Afr. Mus. 1976, 69, 325–353. [Google Scholar]

- Geraads, D. Le Sivatherium (Giraffidae, Mammalia) du Pliocène final d’Ahl al Oughlam (Casablanca, Maroc) et l’evolution du genre en Afrique. Paläontologische Z. 1996, 70, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Khan, M.A.; Iqbal, M.; Akhtar, M.; Sarwar, M. Sivatherium (Artiodactyla, Ruminantia, Giraffidae) from the Upper Siwaliks, Pakistan. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2011, 21, 202–206. [Google Scholar]

- Abel, O. Über einen Fund von Sivatherium giganteum bei Adrianopel. Sitzungsberichte Der Math. Naturwissenschaftlichen Kl. Der Kais. Akad. Der Wiss. 1904, 113, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos, M.; Montoya, P.; Morales, J.; Romero, G. First occurrence of Sivatherium Falconer and Cautley, 1836 (Mammalia, Ruminantia, Giraffidae) in the Iberian Peninsula. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2021, 41, e1985507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufos, G.D.; Syrirdes, G.E. A new Early/Middle Miocene mammal locality from Macedonia, Greece. Comptes Rendus De Académie Des Sci.-Ser. IIA-Earth Planet. Sci. 1997, 325, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufos, G.D. Palaeoecology and chronology of the Vallesian (late Miocene) in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2006, 234, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufos, G.D. Carnivores from the early/middle Miocene locality of Antonios (Chalkidiki, Macedonia, Greece). Geobios 2008, 41, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrides, G.E. Lithostratigraphic, Biostratigraphic and Palaeogeographic Study of the Neogene-Quaternary Sedimentary Deposits of Chalkidiki Peninsula, Macedonia, Greece. Ph.D. Thesis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Scientific Annals of the School of Geology, Thessaloniki, Greece, 1990. Volume 11. pp. 1–243. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoukala, E.; Bartsiokas, A. New Mesopithecus pentelicus specimens from Kryopigi, Macedonia, Greece. J. Hum. Evol. 2008, 54, 448–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridis, G. Contribution to the Study of the Neogene Perissodactyls from Kryopigi (Kassandra, Chalkidiki, Greece). Master’s Thesis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lazaridis, G.; Tsoukala, E. Tetralophodon longirostris (Kaup, 1832) from Late Miocene of the Kassandra peninsula (Chalkidiki, Greece). In Proceedings of the Scientific Annals, School of Geology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece VIth International Conference on Mammoths and their Relatives, Grevena–Siatista, Thessaloniki, Greece, 5–12 May 2014; Volume 102, p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoukala, E.; Melentis, J.K. Deinotherium giganteum Kaup (Proboscidea) from Kassandra Peninsula (Chalkidiki, Macedonia, Greece). Geobios 1994, 27, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridis, G.; Kostopoulos, D.S.; Lyras, G.A.; Roussiakis, S. A new Late Miocene ovibovine-like bovid (Bovidae, Mammalia) from the Kassandra Peninsula (Chalkidiki, Northern Greece) and implications to the phylogeography of the group. Paläontologische Z. 2017, 91, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, M.; Cantero, E.; Estraviz-López, D.; Solounias, N.; Morales, J. Anterior ossicone variability in Decennatherium rex Ríos; et al. 2017 (Late Miocene, Iberian Peninsula). Earth Environ. Sci. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 2023, 114, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddison, W.P.; Maddison, D.R. Mesquite: A Modular System for Evolutionary Analysis (Version 3.61). 2019. Available online: http://www.mesquiteproject.org (accessed on 27 December 2019).

- Goloboff, P.A.; Farris, J.S.; Nixon, K.C. TNT, a free program for phylogenetic analysis. Cladistics 2008, 24, 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Danowitz, M.; Sammis, J.; Solounias, N. Dead ossicones, and other characters describing Palaeotraginae (Giraffidae; Mammalia) based on new material from Gansu, Central China. Zitteliana 2014, B32, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Laskos, K.; Kostopoulos, D.S. On the last European giraffe, Palaeotragus inexspectatus (Mammalia: Giraffidae); new remains from the Early Pleistocene of Greece and a review of the species. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2025, 203, zlae056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solounias, N. Family Giraffidae. In The Evolution of Artiodactyls; Prothero, D.R., Foss, S.E., Eds.; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2007; pp. 257–277. [Google Scholar]

- Parizad, E.; Ataabadi, M.M.; Mashkour, M.; Kostopoulos, D.S. Samotherium Major, 1888 (Giraffidae) skulls from the late Miocene Maragheh fauna (Iran) and the validity of Alcicephalus Rodler & Weithofer, 1890. Comptes Rendus Paleovol 2019, 19, 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Kargopoulos, N.; Marugán-Lobón, J.; Chinsamy, A.; Agwanda, B.R.; Brown, M.B.; Fennessy, S.; Ferguson, S.; Hoffman, R.; Lala, F.; Muneza, A.; et al. Heads up–Four Giraffa species have distinct cranial morphology. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kargopoulos, N.; Marugán-Lobón, J.; Chinsamy, A.; Brown, M.B.; Fennessy, S.; Ferguson, S.; Petzold, A.; Winter, S.; Zabeirou, A.R.M.; Fennessy, J. A Reassessment of the Cranial Diversity of the West African Giraffe. Int. J. Zool. 2025, 2025, 8816347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, R.; Boné, E. Modern giraffes and the fossil giraffids of Africa. Ann. S. Afr. Mus. 1960, 45, 375–548. [Google Scholar]

- Lydekker, B.A. Indian Tertiaty and post-Tertiary Vertebrata. Mem. Geol. Surv. India 1876, 1, 19–83. [Google Scholar]

- Lydekker, R. Notices of Siwalik Mammals. Rec. Geol. Surv. India 1878, 11, 64–104. [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim, G.E. Notices of new Mammalian genera and species from the tertiaries of India–Calcutta. Rec. Geol. Surv. India 1910, 40, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim, G.E. The Fossil Giraffidae of India. Mem. Geol. Surv. India 1911, 4, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti, Z.H.; Khan, M.A.; Akthar, M.; Khsan, A.M.; Ghaffar, A.; Iqbal, M.; Ikram, T. Giraffokeryx (Artiodactyla: Mammalia) remains from the Lower Siwaliks of Pakistan. Pak. J. Zool. 2013, 44, 1623–1631. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, J.M. Orientation and variability in the ossicones of African Sivatheriinae (Mammalia: Giraffidae). Ann. S. Afr. Mus. 1974, 65, 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos, M.; Morales, J. A new skull of Decennatherium rex Ríos, Sánchez and Morales, 2017 from Batallones-4 (upper Vallesian, MN10, Madrid, Spain). Palaeontol. Electrónica 2019, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, K.; Khan, M.A.; Babar, M.A.; Akhtar, M. Siwalik Giraffidae (Mammalia, Artiodactyla): A review. Punjab Univ. J. Zool. 2015, 30, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Draz, O.; Ni, X.; Samiullah, K.; Yasin, R.; Fazal, R.M.; Naz, S.; Akhtar, S.; Gillani, M.; Ejaz, M. New Fossil Remains of Artiodactyla from Dhok Pathan Formation, Middle Siwaliks of Punjab, Pakistan. Pak. J. Zool. 2020, 52, 1631–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, R. Diet and habitat changes among Siwalik herbivorous mammals in response to Neogene and Quaternary climate changes: An appraisal in the light of new data. Quat. Int. 2015, 371, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merceron, G.; Colyn, M.; Geraads, D. Browsing and non-browsing extant and extinct giraffids: Evidence from dental microwear textural analysis. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2018, 505, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohe, L.R.; Solounias, N. The five digits of the giraffe metatarsal. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2020, 131, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraads, D.; Spassov, N.; Hristova, L.; Markov, G.N.; Tzankov, T. Upper Miocene mammals from Strumyani, South-Western Bulgaria. Geodiversitas 2011, 33, 451–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solounias, N.; Danowitz, M. Astragalar morphology of selected Giraffidae. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, M.; Abbas, S.G.; Khan, M.A.; Solounias, N. A new giraffid Bramiscus micros nov. gen. nov. sp. (Ruminantia, Giraffidae) from the Miocene of northern Pakistan. Palaeontol. Electron. 2024, 27, a29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimberly, A.N. Predicting body mass in Ruminantia using postcranial measurements. J. Morphol. 2023, 284, e21636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laskos, K.; Lazaridis, G.; Tsoukala, E.; Vlachos, E.; Kostopoulos, D.S. First Record of Bramatherium Falconer, 1845 (Mammalia: Giraffidae) from the Late Miocene of Greece and the Helladotherium-Bramatherium Debate. Foss. Stud. 2025, 3, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/fossils3040017

Laskos K, Lazaridis G, Tsoukala E, Vlachos E, Kostopoulos DS. First Record of Bramatherium Falconer, 1845 (Mammalia: Giraffidae) from the Late Miocene of Greece and the Helladotherium-Bramatherium Debate. Fossil Studies. 2025; 3(4):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/fossils3040017

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaskos, Kostantis, Georgios Lazaridis, Evangelia Tsoukala, Evangelos Vlachos, and Dimitris S. Kostopoulos. 2025. "First Record of Bramatherium Falconer, 1845 (Mammalia: Giraffidae) from the Late Miocene of Greece and the Helladotherium-Bramatherium Debate" Fossil Studies 3, no. 4: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/fossils3040017

APA StyleLaskos, K., Lazaridis, G., Tsoukala, E., Vlachos, E., & Kostopoulos, D. S. (2025). First Record of Bramatherium Falconer, 1845 (Mammalia: Giraffidae) from the Late Miocene of Greece and the Helladotherium-Bramatherium Debate. Fossil Studies, 3(4), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/fossils3040017