Abstract

Carotid paragangliomas are rare neuroendocrine tumors that, despite being typically benign, present significant surgical and anesthetic challenges. This manuscript outlines the anesthetic management for surgical resection, highlighting preoperative assessment, intraoperative monitoring, and postoperative care. A multidisciplinary approach is essential, particularly for functional tumors, requiring preoperative screening and pharmacologic preparation. Intraoperatively, cerebral perfusion monitoring is critical to prevent ischemic events. Postoperative vigilance is necessary to detect complications such as bleeding, cranial nerve deficits, and hemodynamic instability. A multidisciplinary team skilled in these surgical procedures is essential to improve safety in carotid paraganglioma surgery.

1. Introduction

Carotid body paragangliomas are rare hypervascularized neuroendocrine tumors, also known as carotid body tumors (CBTs). Parasympathetic paragangliomas are usually nonfunctional, unlike sympathetic paragangliomas, which are catecholamine-secreting and located along the sympathetic paravertebral ganglia. Both sympathetic and parasympathetic paragangliomas arise from neuroendocrine cells derived from the embryonic neural crest [1]. Head and neck paragangliomas usually present as a neck lump with or without symptoms, such as sore throat, dysphonia, hoarseness, stridor, dysphagia, odynophagia, jaw stiffness, and neck pain. Conductive hearing loss and pulsatile tinnitus might be present in cases of jugulo-timpanic paragangliomas, while lower cranial nerve deficits can be observed in advanced forms [2]. Rarely, there is a severe pattern, and histamine, serotonin, epinephrine, and norepinephrine can be released. In such cases, hypertension, sweating, tachycardia, and headache may be present, mimicking the presentation of pheochromocytomas. Recent literature suggests a molecular basis for the development of some paragangliomas, with six genes mainly involved: RET, VHL, NF1, and the SDH subunits SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD. SDHB and SDHD mutations are often involved in head and neck paragangliomas [3]. 30% of paragangliomas are caused by mutations in genes associated with the mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase complex (SDHB, SDHC, SDHD), with autosomal dominant inheritance, which cause deregulation of hypoxia-induced factors [4]. When feasible, radical surgical resection (with vascular reconstruction if required) remains the gold-standard approach for treatment of CBTs. However, the surgical team will encounter several clinical and technical challenges in the operating room when dealing with these tumors. Owing to their rarity, current guidelines do not provide formal recommendations on how to approach CBTs from the perspective of perioperative care. Therefore, the objective of this article is to provide an expert-based overview of anesthetic approaches for the surgical management of CBTs. This includes a comprehensive analysis of preoperative evaluation, intraoperative anesthetic monitoring and management, and postoperative care strategies to enhance patient safety, minimize perioperative complications, and improve surgical outcomes.

2. Classification and Anatomy

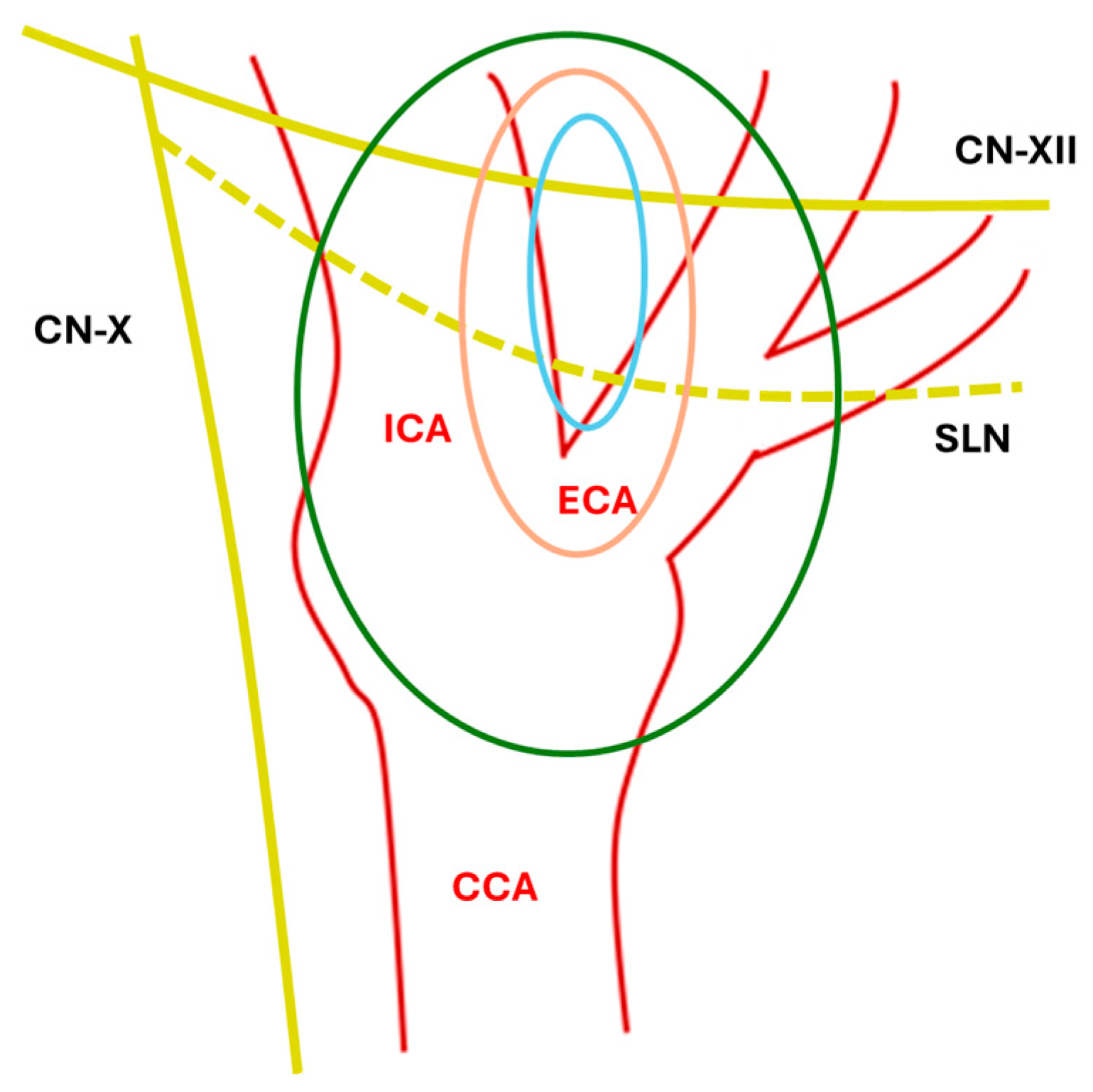

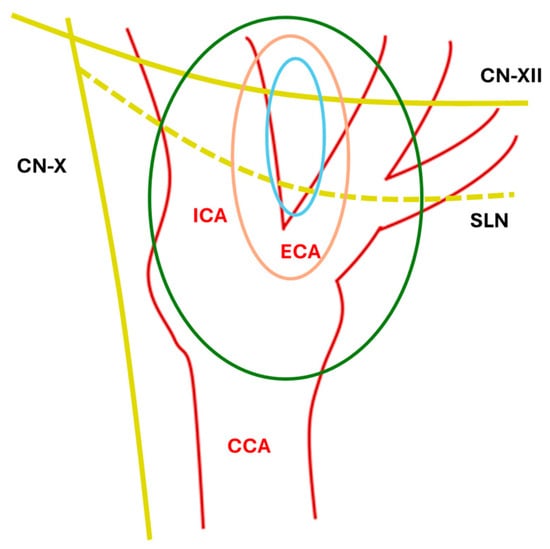

CBTs are usually classified with the Shamblin scheme [3,4], which is based on the relationship with vessels and local invasion (Table 1, Figure 1).

Table 1.

Shamblin classification.

Figure 1.

Anatomical Shamblin Scheme. ICA: internal carotid artery; ECA: External carotid artery; CCA: common carotid artery; SLN: superior laryngeal nerve; CN-XII: XII cranial nerve; CN-X: X cranial nerve; blue line: type I; orange line: type II; green line: type III.

Notably, paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas cannot be differentiated histologically and are, respectively, classified by the WHO as extradrenal and adrenal tumors [5]. Carotid body paragangliomas are present in up to 60% of cases at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery, and they have a slow-growing pattern, making them invasive but indolent tumors. There are three distinct types: sporadic, familial (involving mainly younger patients and more likely to be malignant), and hyperplastic.

3. Surgical Approach

3.1. Diagnostic and Imaging Assessment

Carotid body tumors (CBTs) are diagnosed through clinical evaluation and imaging studies. Patients typically present with a painless, slowly enlarging lateral neck mass, sometimes associated with cranial nerve deficits or symptoms related to catecholamine secretion in functional tumors. Preoperative imaging, including angiography, MRI, and CT angiography, plays a critical role in surgical planning by delineating the tumor’s vascular supply and its relationship with surrounding neurovascular structures. The Shamblin classification remains the most widely used system for estimating surgical complexity and risk of vascular or nerve involvement [6,7,8,9].

3.2. Preoperative Surgical Assessment

Surgical resection remains the cornerstone of treatment for CBTs, particularly in patients with symptomatic, rapidly growing, functional, or malignant lesions. Surgery is generally indicated for tumors classified as Shamblin II or III, which present a higher risk of vascular or cranial nerve involvement due to their size and anatomical complexity [6,7]. For younger patients with good overall health, surgical intervention is prioritized to ensure complete tumor removal and minimize the risk of recurrence or progression [8,9]. Preoperative strategies are essential to optimize outcomes and minimize intraoperative risks. Preoperative embolization is often performed to reduce the tumor’s vascularity by occluding its feeding arteries, primarily branches of the external carotid artery. This technique has been shown to significantly decrease intraoperative blood loss, particularly for larger tumors (Shamblin II–III). However, its benefit for smaller lesions remains less definitive, and the decision must be individualized based on tumor characteristics and institutional expertise [9,10].

3.3. Surgical Techniques

The surgical management of CBTs requires meticulous planning and technical expertise due to the complex anatomy and highly delicate site. For Shamblin I tumors, subadventitial dissection is typically sufficient to achieve complete resection while preserving the carotid bifurcation [6,7]. These smaller tumors, with minimal attachment to the internal or external carotid arteries, can usually be removed with relatively low risk of vascular or neurological complications. For Shamblin II and III tumors, the surgical approach becomes significantly more complex. These lesions frequently adhere to or encase the carotid arteries. When the tumor infiltrates the vessel, partial resection and vascular reconstruction using vein grafts or synthetic conduits may be necessary [6,7,10]. Temporary arterial clamping may facilitate tumor removal, but continuous monitoring of cerebral perfusion is mandatory to prevent ischemic complications. Intraoperative neuromonitoring is also recommended to reduce the risk of cranial nerve injury, particularly involving the hypoglossal, vagus, and glossopharyngeal nerves [8,9].

3.4. Potential Complications

Despite the technical challenges, surgical outcomes are generally favorable, especially for benign tumors. Nevertheless, complications such as cranial nerve deficits, stroke, and pseudoaneurysm formation may occur, particularly in larger or more invasive lesions. Postoperative cranial nerve deficits are reported in up to 20% of cases, with higher rates observed in Shamblin II and III tumors [6,7]. Stroke and vascular complications are relatively rare but can have severe consequences, emphasizing the importance of surgical expertise and careful perioperative management.

3.5. Adjuvant and Alternative Treatments

Radiotherapy represents an alternative or adjuvant option, particularly for patients with inoperable tumors, extensive Shamblin III lesions, or recurrent disease. Advances such as stereotactic radiotherapy and proton beam therapy have increased treatment precision and safety, minimizing damage to adjacent structures. Although radiotherapy is not curative for benign CBTs, it effectively stabilizes tumor growth and alleviates symptoms in selected cases, especially in patients unfit for surgery or those with malignant or metastatic disease [7,8,9,10]. In rare cases, chemotherapy may be considered as an adjunctive treatment. Its role remains limited to advanced or metastatic CBTs and is typically employed in a palliative setting to control disease progression rather than achieve cure. Current evidence is limited, and chemotherapy is often combined with radiotherapy in aggressive or inoperable cases [7,9,10].

3.6. Role of Neuroendovascular Surgeons

The presence of neuroendovascular enables the use of covered stents and endovascular vessel sacrifice to control life-threatening hemorrhage when open techniques are insufficient. Covered stents are most effective in the internal carotid artery (ICA) or common carotid artery (CCA), and their use requires careful consideration of vessel anatomy, the risk of stent exposure (especially in previously irradiated or necrotic fields), and the need for antiplatelet therapy. While covered stents can provide immediate hemostasis and maintain cerebral perfusion, long-term patency may be compromised by infection, exposure, or in-stent restenosis, and subsequent surgical revascularization may be required if complications arise [11,12].

3.7. Preoperative Endovascular Balloon Test Occlusion

There is a lack of large, prospective studies and standardized protocols for endovascular balloon test occlusion (BTO) in the context of paraganglioma surgery. The optimal duration of occlusion, degree of induced hypotension, and choice of adjunctive monitoring remain areas for further research. False negatives can occur, and delayed ischemic events have been reported even in patients who pass BTO at normotension, particularly if cerebrovascular reserve is marginal [13]. Standard BTO is performed under normotensive conditions, typically with the patient awake or under light sedation, using a compliant balloon catheter to temporarily occlude the target carotid artery. Clinical neurological assessment is performed throughout the occlusion, often supplemented by transcranial Doppler (TCD) monitoring of the ipsilateral middle cerebral artery (MCA) to detect changes in cerebral blood flow [14,15]. To further assess cerebrovascular reserve, a hypotensive challenge may be performed by pharmacologically lowering systemic blood pressure—typically using intravenous nitroprusside or labetalol—to 20–30% below baseline mean arterial pressure. Continuous clinical, hemodynamic, and imaging monitoring during this phase is recommended to maximize safety and predictive accuracy.

4. Anesthesiological Approach

Surgery of CBTs may pose several challenges also in terms of anesthesiological management: a carefully conducted preoperative evaluation to identify any possible risks and complications related to the individual patient and the type of tumor, an adequate intraoperative monitoring, aimed at preventing complications during surgery and intervening immediately to resolve any problems related to the surgical procedure, and finally adequate postoperative monitoring are all key to achieve satisfactory outcomes. Furthermore, regional variability in anesthesiological management and clinical practice has been reported, reflecting differences in expertise, resources, and institutional protocols (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of key practices and outcomes reported by major centers managing carotid body tumors.

4.1. Preoperative Assessment

In addition to standard preoperative assessment (electrocardiogram -ECG, chest X-ray, blood tests), patients with head and neck paragangliomas—especially those involving the skull base—should undergo thorough cranial nerve evaluation (VII, X, XI, XII) due to the risk of intraoperative injury. Although most head and neck paragangliomas are non-functioning, in cases with symptoms such as hypertension, tachycardia, or family history of paragangliomas, biochemical screening for catecholamine excess (24 h urinary or plasma metanephrines and normetanephrines) is recommended [22]. If catecholamine secretion is confirmed, preoperative pharmacologic preparation is essential to minimize intraoperative cardiovascular complications. First-line therapy involves non-selective alpha-blockade using phenoxybenzamine, typically initiated 10–14 days before surgery. Alternatively, selective alpha-1 blockers like doxazosin or prazosin may be used, particularly when side effects such as orthostatic hypotension need to be minimized. Once adequate alpha-blockade is achieved (evidenced by normalized blood pressure and mild orthostatic symptoms), beta-blockers such as propranolol or atenolol may be added to control tachycardia but only after alpha-blockade, to avoid hypertensive crises due to unopposed alpha-adrenergic stimulation [23]. Volume expansion with liberal fluid intake is also advised during the preoperative period to counteract vasodilation and reduce the risk of postoperative hypotension [24]. Despite optimal preparation, intraoperative blood pressure fluctuations are common; therefore, surgery should be performed in specialized centers with expertise in catecholamine-secreting tumors. In line with the surgical approach, the choice of optimal intraoperative neuromonitoring should be a key component of preoperative planning. During CBTs resection, temporary carotid clamping may be necessary, posing a risk of cerebral hypoperfusion. Therefore, all members of the multidisciplinary team should determine the most appropriate strategy for real-time cerebral monitoring. Preoperatively, all patients should be evaluated for contralateral carotid artery disease, as compromised flow may significantly increase the risk of ischemic complications. Depending on institutional protocols and available expertise, intraoperative neuromonitoring may include continuous electroencephalogram (EEG) interpretation by a neurologist, transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasonography performed by clinicians trained in cerebrovascular monitoring, or near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS). These modalities help assess cerebral perfusion in real time and guide decisions on carotid clamping duration and shunt placement, enhancing patient safety during high-risk surgical phases [22,25].

A comprehensive approach ensures that both cerebrovascular and cardiac risks are appropriately assessed and managed, optimizing perioperative safety in patients undergoing procedures with potential for carotid cross-clamping. Cardiac preoperative assessment should begin with a thorough clinical evaluation, including detailed history, assessment of functional capacity (e.g., metabolic equivalents), and risk stratification using validated tools such as the Revised Cardiac Risk Index. A preoperative 12-lead electrocardiogram is recommended to identify silent ischemia, arrhythmias, and provide a baseline for postoperative comparison [26]. Echocardiography is indicated in patients with symptoms of heart failure, known valvular disease, abnormal ECG findings, or reduced functional capacity, as it provides critical information on left ventricular function and valvular pathology [26]. Additional testing, such as stress testing or coronary angiography, should be reserved for patients with active cardiac symptoms [27]. Assessment of supraaortic arteries in patients who may undergo carotid surgery begins with duplex ultrasound as the initial diagnostic modality for evaluating the bilateral carotid and vertebral arteries, especially in those with symptoms of cerebral ischemia, history of stroke or TIA, carotid bruit, age > 65, peripheral artery disease, left main coronary artery disease, or a history of smoking [26].

4.2. Intraoperative Management

General anesthesia is the most common choice for this type of surgical procedure. Currently, there is no specific recommendation around the choice of anesthetic agents. It is usually more relevant to achieve an adequate anesthetic level that inhibits the cardiovascular response in relation to the effect of catecholamines in CBTs secernent. Continuous monitoring of the patient is necessary due to possible rapid blood pressure changes during tumor manipulation and excision. Basic monitoring should include ECG, pulse oximetry, invasive blood pressure monitoring, and an appropriate infusion line. All patients should have at least two large-bore peripheral IV lines (16–18 G) for induction, maintenance, and rapid transfusion if significant blood loss occurs [28,29]. A continuous arterial line (radial or femoral) is mandatory for beat-to-beat blood pressure monitoring and rapid blood sampling, given the risk of hemodynamic instability during carotid manipulation [28,29,30]. Central venous access is optional, recommended for large tumors (Shamblin II/III), anticipated major blood loss, poor peripheral access, or when vasoactive infusions are expected.

The main aim of this type of surgery is to maintain adequate operating conditions for the surgeon while ensuring optimal cerebral perfusion to prevent cerebral ischemia. For this reason, comprehensive cerebral monitoring is essential to assess cerebral perfusion during arterial clamping [22,31]. Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) is a safe and reliable method for quantifying cerebral blood flow, regional cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO2), and cerebral metabolism. According to the literature [25], a 15–20% decrease in rSO2 compared to baseline values indicates impaired cerebral perfusion. Additionally, transcranial Doppler can be employed to monitor cerebral blood flow (CBF) and to detect cerebral vasospasm or assess the vascular response to carotid clamping [22,31]. Other neuromonitoring strategies may include electroencephalogram (EEG) analysis, as well as the assessment of motor and sensory evoked potentials [32]. Temperature monitoring and management are also crucial components of neuroprotection, as the cerebral metabolic rate decreases by approximately 7% for each 1 °C reduction in body temperature [31]. Intraoperatively, hemodynamic instability is commonly observed due to surgical manipulation of the carotid glomus. Reflex bradycardia and hypotension may occur with carotid sinus stimulation. These episodes can be managed by local surgical infiltration around the carotid sinus or thanks to intravenous drugs, such as atropine, to prevent both bradycardic and hypotensive responses. Advanced hemodynamic monitoring can be performed using either transesophageal Doppler or pulse contour analysis methods, depending on the case. The use of a Swan–Ganz catheter is reserved for selected patients with underlying unstable heart disease, particularly those with conditions secondary to pheochromocytoma or paragangliomas. During carotid manipulation, maintaining adequate cerebral perfusion pressure across the circle of Willis is critical to minimize the risk of ischemic neurological events. The recommended target for systolic blood pressure (SBP) intraoperatively is between the patient’s baseline value and 20% above it during carotid clamping [32]. However, excessive hypertension during this phase can increase the risk of myocardial ischemia and intracranial hemorrhage. Therefore, blood pressure must be carefully titrated according to real-time cerebral monitoring data. Short-acting antihypertensive agents are preferred for intraoperative control, with drugs such as nicardipine and labetalol commonly used due to their stable hemodynamic profiles and minimal impact on cerebral autoregulation. Direct vasodilators such as nitroprusside should be used cautiously, as they may exacerbate cerebral hyperperfusion, especially in patients with impaired autoregulation. Conversely, in cases of hypotension during clamping, vasopressor agents such as ephedrine or norepinephrine may be employed [33]. The balance between preserving cerebral perfusion and minimizing cardiovascular risks should always be guided by patient monitoring.

Recommended anesthesia techniques for patients undergoing carotid body tumor surgery include general anesthesia (with volatile agents or total intravenous anesthesia), regional anesthesia (most commonly a superficial cervical plexus block), and, in select cases, local anesthesia or monitored anesthesia care. Combinations of these techniques are frequently employed, tailored to patient and procedural factors. No anesthetic technique or agent has demonstrated superiority for neuroprotection or stroke reduction in humans; the choice of agent is unlikely to influence perioperative stroke risk [28]. Nitrous oxide is not contraindicated, but its use should be considered in the context of individual patient risk factors [28]. Data specific to carotid body tumor surgery are limited, and most recommendations are extrapolated from the carotid endarterectomy literature. The choice between inhalation and intravenous anesthesia should be individualized, taking into account patient comorbidities (e.g., cardiovascular or neurologic disease), tumor size, and Shamblin grade, the use of preoperative embolization, and the experience of the anesthesia and surgical teams [28,34,35].

There is limited prospective data on optimal intraoperative anesthetic protocols and the long-term outcomes of vessel-control strategies in head and neck paraganglioma surgery. However, the current consensus emphasizes the necessity of a multidisciplinary approach, preoperative adrenergic blockade, vigilant intraoperative monitoring, and close anesthesiologist–surgeon cooperation to optimize hemodynamic stability and surgical outcomes [36,37]. Intraoperatively, the anesthesiologist maintains a deep plane of anesthesia, continuous invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring, and is prepared for rapid pharmacologic intervention. Hypertensive crises may occur during tumor manipulation, especially near the carotid bifurcation or when dissecting close to the vagus, hypoglossal, and glossopharyngeal nerves, due to catecholamine surges or direct vagal stimulation. Bradycardia or asystole can result from vagal stimulation, requiring immediate communication and coordinated response between the surgical and anesthesia teams. The anesthesiologist must be prepared to administer short-acting antihypertensives (e.g., sodium nitroprusside, phentolamine, esmolol) for hypertension, and atropine or glycopyrrolate for bradycardia, titrating agents in real time based on hemodynamic changes [16,36,38]. Extended operative times and hemodynamic instability are managed with careful titration of vasoactive agents (Table 3), judicious fluid management, and, when necessary, blood product administration.

Table 3.

A list of antihypertensive drugs. BP: blood pressure.

4.3. Practical Intraoperative Challenges and Anesthesiologist–Surgeon Collaboration

The surgical removal of carotid paragangliomas exposes the patient to sudden hemodynamic fluctuations, especially during tumor manipulation, carotid sinus stimulation, and vessel clamping. From the anesthetic standpoint, the priority is to maintain cerebral perfusion while avoiding hypertensive crises that may increase bleeding risk and complicate dissection [35]. This balance requires real-time communication with the surgical team and rapid decision-making based on multimodal monitoring. Intraoperative hypertension is typically observed during the dissection of the tumor from the carotid bifurcation. In these phases, the surgeon often requests controlled hypotension to improve visualization and reduce blood loss. Conversely, when carotid clamping is needed, the anesthesiologist must increase mean arterial pressure (MAP) by 10–20% above baseline to maintain collateral cerebral perfusion [39]. This interplay imposes a dynamic hemodynamic strategy, where vasodilators, vasopressors, and fluid management are titrated according to the surgical phase (Table 4). Bradycardia and hypotension caused by direct stimulation of the carotid sinus represent another frequent intraoperative challenge. Local infiltration with lidocaine can reduce the reflex response, but severe bradycardia/asystole may require temporary interruption of dissection and prompt pharmacologic treatment [40,41]. These events underline the necessity of coordinated action: the surgeon alerts the anesthesiologist before manipulation, while the anesthesiologist prepares atropine or glycopyrrolate and adjusts anesthetic depth. Massive bleeding and difficult vascular control represent the most critical intraoperative scenarios. In high-risk Shamblin II–III tumors, some centers anticipate these complications by planning preoperative embolization, preparing vascular shunts, or involving an endovascular surgeon capable of stenting the carotid if catastrophic hemorrhage occurs. Dedicated checklists and predefined roles facilitate fast decision-making and improve outcomes in crises [42]. Differences between centers mainly reflect experience, team composition, and available resources. High-volume teams emphasize cerebral monitoring (NIRS/TCD), aggressive preoperative alpha-blockade when functional tumors are suspected, and structured communication protocols between anesthesia and surgery. These elements allow timely recognition of dangerous trends (falling cerebral saturation, surges in blood pressure, blood loss) and rapid adaptation of the surgical strategy.

Table 4.

Management of Intraoperative Hemodynamic Fluctuations. MAP: mean arterial pressure; rSO2: regional cerebral oxygen saturation; BP: blood pressure.

4.4. Postoperative Management

Although admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) is not always required, close monitoring for at least 24 h postoperatively is recommended. Common postoperative complications include hypotension, hypertension, stroke, both permanent and transient cranial nerve palsy or paresis, profound hypotension, Horner’s syndrome, and, in some cases, respiratory depression. One of the most serious and potentially life-threatening complications in neck surgery is postoperative bleeding. The literature emphasizes the critical importance of early recognition of hematoma-related complications [43]. For this purpose, the acronym DESATS was introduced, which stands for Difficulty Swallowing/Discomfort, Early Warning Score (EWS) or National Early Warning Score (NEWS) increase, Swelling, Anxiety, Tachypnoea/difficulty breathing, and Stridor. If one or more of these signs are observed, it is essential to Oxygenate the patient, elevate the head of the bed to a 45° angle, request immediate senior surgical review, and if there is any sign of airway compromise, proceed with immediate orotracheal intubation and hematoma evacuation.

This scenario can be particularly challenging for the anesthesiology team due to the high likelihood of a difficult airway. Therefore, all necessary airway management equipment and resources should be prepared and readily available in advance. Postoperative pain management is also a cornerstone due to the extensive surgical dissection often required and the potential for nerve manipulation or sacrifice. A multimodal analgesic approach is recommended [44], incorporating acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and opioids as needed according to perioperative risks. Intraoperative regional anesthetic techniques, such as local infiltration with long-acting anesthetics, may also reduce immediate postoperative pain. Moreover, preemptive analgesia and careful intraoperative nerve preservation can mitigate the development of chronic neuropathic pain. Patients with cranial nerve deficits post-surgery should be monitored for oropharyngeal discomfort or referred pain, which may necessitate specialized pain management strategies. Given the complexity of CBT resections, individualized pain control protocols should be considered to enhance recovery and patient comfort. Lower cranial nerve palsies (IX, X, XII) are a frequent and significant complication after paraganglioma surgery, particularly in cases involving jugular, vagal, or large carotid body tumors. The risk is highest with extensive tumors or those requiring aggressive resection, and the resulting deficits can lead to profound dysphagia, aspiration, impaired airway protection, and diminished quality of life [45]. Early gastrostomy should be considered in patients with persistent severe dysphagia, recurrent aspiration, or inability to maintain adequate oral intake following lower cranial nerve injury [46,47]. This is particularly relevant when compensatory strategies fail or when aspiration risk is high, as early enteral access can prevent malnutrition and aspiration pneumonia. Tracheostomy should be considered for patients with bilateral or multiple lower cranial nerve palsies, significant aspiration risk, or airway compromise not manageable by other means [48,49].

Given the complexity and challenges of CBT management, highly specialized and multidisciplinary management is required. Table 5 summarizes potentially useful adjuncts for management.

Table 5.

Adjuncts during the management of carotid body tumors. IV: intravenous; CTA: Computed Tomography Angiography; MRA: Magnetic Resonance Angiography.

5. Conclusions

CBTs are rare, typically benign but potentially aggressive, and they require highly specialized and multidisciplinary management. Surgical resection remains the gold standard, particularly for symptomatic, enlarging, or malignant lesions, and should aim for complete removal while preserving neurovascular integrity whenever possible. The available literature underscores the feasibility of surgical excision with low morbidity when performed in experienced centers. However, complications such as cranial nerve palsy, stroke, or carotid blowout, though uncommon, can occur, highlighting the importance of meticulous intraoperative technique and perioperative vigilance. From the anesthesiological perspective, comprehensive preoperative assessment—including screening for functional tumors—and intraoperative cerebral and hemodynamic monitoring are crucial, especially in Shamblin II and III tumors where vessel encasement increases surgical difficulty. The use of cerebral perfusion monitoring tools (e.g., NIRS, TCD) and readiness for hemodynamic instability are essential. Postoperatively, close monitoring for bleeding, cranial nerve dysfunction, and respiratory compromise is vital, as illustrated by the emphasis on early recognition strategies such as the DESATS protocol. Pain management should be individualized and multimodal, particularly in cases with extensive dissection or nerve manipulation. Ultimately, favorable long-term outcomes, as evidenced by the absence of local recurrence in benign cases and manageable relapse in malignant ones, are achievable through a tailored, multidisciplinary strategy. This approach ensures not only the technical success of tumor removal but also optimizes patient safety, comfort, and quality of life throughout the perioperative journey. Given the complexity and potential hemodynamic instability associated with carotid body tumor surgery, these procedures should be performed exclusively in high-volume centers equipped with advanced hemodynamic monitoring and vascular management capabilities. Such settings ensure optimal perioperative safety, prompt management of complications, and improved neurological outcomes. Future challenges include refining minimally invasive techniques, enhancing cranial nerve preservation, and developing standardized perioperative protocols through multicenter collaboration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G., M.B.R., N.G., M.F., M.T. and M.D.; methodology, L.G., M.B.R. and N.G.; validation, G.P., A.B., L.C. and M.T.; original draft preparation, L.G., M.B.R., N.G. and M.F.; review and editing, L.G., M.B.R., N.G., M.F., G.P., A.B., L.C. and M.C.C.; supervision, G.P., A.B. and L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sajid, M.S.; Hamilton, G.; Baker, D.M. A Multicenter Review of Carotid Body Tumour Management. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2007, 34, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, D.; Kudva, Y.C.; Ebersold, M.J.; Thompson, G.B.; Grant, C.; van Heerden, J.; Young, W.F. Benign paragangliomas: Clinical pre sentation and treatment outcomes in 236 patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 52106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, G.; Lukasiewicz, A.; Grinievych, V.; Tarasow, E. Carotid Body Tumor—Radiological imaging and genetic assessment. Pol. Przegl. Chir. 2020, 92, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wieneke, J.A.; Smith, A. Paraganglioma: Carotid body tumor. Head Neck Pathol. 2009, 3, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tischler, A.S.; de Krijger, R.R.; Gill, A.J.; Kimura, N.; McNicol, A.M.; Young, W.F., Jr. Phaechromocytoma. In WHO Classification of Tumours of Endocrine Organs, 4th ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2017; pp. 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Shiga, K.; Katagiri, K.; Ikeda, A.; Saito, D.; Oikawa, S.I.; Tsuchida, K.; Miyaguchi, J.; Kusaka, T.; Tamura, A. Challenges of Surgical Resection of Carotid Body Tumors—Multiple Feeding Arteries and Preoperative Embolization. Anticancer Res. 2022, 42, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, F.S.; Muñoz, A.; de Las Heras, J.A.; González-Porras, J.R. Simple and complex carotid paragangliomas. Three decades of experience and literature review. Head Neck 2020, 42, 3538–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Urquijo, M.; Castro-Varela, A.; Barrios-Ruiz, A.; Hinojosa-Gonzalez, D.E.; Salas, A.K.G.; Morales, E.A.; González-González, M.; Fabiani, M.A. Current trends in carotid body tumors: Comprehensive review. Head Neck 2022, 44, 2316–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valero, C.; Ganly, I. Paragangliomas of the head and neck. J. Oral. Pathol. Med. 2022, 51, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napoli, G.; Tritto, R.; Moscarelli, M.; Forleo, C.; La Marca, M.G.C.; Yang, L.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Giordano, A.; Tshomba, Y.; Pepe, M. Role of pre-operative embolization in carotid body tumor surgery according to Shamblin classification: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck 2023, 45, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, N.F.; Rezaee, R.P.; Ray, A.; Wick, C.C.; Blackham, K.; Stepnick, D.; Lavertu, P.; Zender, C.A. Contemporary Management of Carotid Blowout Syndrome Utilizing Endovascular Techniques. Laryngoscope 2017, 127, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Micco, R.; Salcher, R.B.; Götz, F.; Abu Fares, O.; Lenarz, T. The Role of Internal Carotid Artery Stent in the Management of Skull Base Paragangliomas. Cancers 2024, 16, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooij, W.J.; Sluzewski, M.; Metz, N.H.; Nijssen, P.C.G.; Wijnalda, D.; Rinkel, G.J.E.M.; Tulleken, C.A.F.M. Carotid Balloon Occlusion for Large and Giant Aneurysms: Evaluation of a New Test Occlusion Protocol. Neurosurgery 2000, 47, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelblová, M.; Vaníček, J.; Gál, B.; Rottenberg, J.; Bulik, M.; Cimflová, P.; Křivka, T. Preoperative Percutaneous Onyx Embolization of Carotid Body Paragangliomas with Balloon Test Occlusion. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1132100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorteberg, A.; Bakke, S.J.; Boysen, M.; Sorteberg, W. Angiographic Balloon Test Occlusion and Therapeutic Sacrifice of Major Arteries to the Brain. Neurosurgery 2008, 63, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, L.R.; Ramamoorthy, B.; Nilubol, N. Progress in Surgical Approaches and Outcomes of Patients with Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 39, 101954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Phay, J.E.; Yen, T.W.F.; Dickson, P.V.; Wang, T.S.; Garcia, R.; Yang, A.D.; Kim, L.T.; Solórzano, C.C. Update on Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma from the SSO Endocrine and Head and Neck Disease Site Working Group, Part 2 of 2: Perioperative Management and Outcomes of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 27, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persky, M.S.; Setton, A.; Niimi, Y.; Hartman, J.; Frank, D.; Berenstein, A. Combined Endovascular and Surgical Treatment of Head and Neck Paragangliomas—A Team Approach. Head Neck 2002, 24, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taïeb, D.; Wanna, G.B.; Ahmad, M.; Lussey-Lepoutre, C.; Perrier, N.D.; Nölting, S.; Amar, L.; Timmers, H.J.L.M.; Schwam, Z.G.; Estrera, A.L.; et al. Clinical Consensus Guideline on the Management of Phaeochromocytoma and Paraganglioma in Patients Harbouring Germline SDHD Pathogenic Variants. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023, 11, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, H.P.H.; Young, W.F.; Eng, C. Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 552–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, G.; An, B.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, X. Challenges in the Surgical Treatment of Undiagnosed Functional Paragangliomas: A Case Report. Medicine 2018, 97, e12478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavakli, A.S.; Ozturk, N.K. Anesthetic approaches in carotid body tumor surgery. North. Clin. Istanb. 2016, 3, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Sivasankar, C. Anesthetic management of schwannoma mimicking carotid body tumor. Int. Med. Case Rep. J. 2012, 5, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenders, J.W.; Duh, Q.Y.; Eisenhofer, G.; Gimenez-Roqueplo, A.P.; Grebe, S.K.; Murad, M.H.; Naruse, M.; Pacak, K.; Young, W.F., Jr. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 915–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.W.; Jang, J.S. Near-Infrared Spectroscopy versus Transcranial Doppler-Based Monitoring in Carotid Endarterectomy. Korean J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2017, 50, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamperti, M.; Romero, C.S.; Guarracino, F.; Cammarota, G.; Vetrugno, L.; Tufegdzic, B.; Lozsan, F.; Frias, J.J.M.; Duma, A.; Bock, M.; et al. Preoperative Assessment of Adults Undergoing Elective Noncardiac Surgery: Updated Guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2025, 42, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilowitz, N.R.; Berger, J.S. Perioperative Cardiovascular Risk Assessment and Management for Noncardiac Surgery: A Review. JAMA 2020, 324, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohebali, J.; Edwards, H.A.; Schwartz, S.I.; Ergul, E.A.; Deschler, D.G.; LaMuraglia, G.M. Multispecialty Surgical Management of Carotid Body Tumors in the Modern Era. J. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 73, 2036–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubowitz, J.; Riedel, B.; Blaas, C.; Hiller, J.; Braat, S. On the Horns of a Dilemma: Choosing Total Intravenous Anaesthesia or Volatile Anaesthesia for Cancer Surgery, an Enduring Controversy. Br. J. Anaesth. 2024, 132, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernick, B.D.; Furlough, C.L.; Patel, U.; Samant, S.; Hoel, A.W.; Rodriguez, H.E.; Tomita, T.T.; Eskandari, M.K. Contemporary Management of Carotid Body Tumors in a Midwestern Academic Center. Surgery 2021, 169, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karigar, S.L.; Kunakeri, S.; Shetti, A.N. Anesthetic management of carotid body tumor excision: A case report and brief review. Anesth. Essays Res. 2014, 8, 259–262. [Google Scholar]

- Stoneham, M.D.; Thompson, J.P. Arterial pressure management and carotid endarterectomy. BJA Br. J. Anaesth. 2009, 102, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reslan, O.M.; McPhee, J.T.; Brener, B.J.; Row, H.T.; Eberhardt, R.T.; Raffetto, J.D. Peri-Procedural Management of Hemodynamic Instability in Patients Undergoing Carotid Revascularization. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 85, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouhin, A.; Die Loucou, J.; Malikov, S.; Gallet, P.; Anxionnat, R.; Jazayeri, A.; Steinmetz, E.; Settembre, N. Surgical Management of Carotid Body Tumors: Experience of Two Centers. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2024, 98, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benesch, C.; Glance, L.G.; Derdeyn, C.P.; Fleisher, L.A.; Holloway, R.G.; Messé, S.R.; Mijalski, C.; Nelson, M.T.; Power, M.; Welch, B.G.; et al. Perioperative Neurological Evaluation and Management to Lower the Risk of Acute Stroke in Patients Undergoing Noncardiac, Nonneurological Surgery: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e923–e946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filpo, G.; Parenti, G.; Sparano, C.; Rastrelli, G.; Rapizzi, E.; Martinelli, S.; Amore, F.; Badii, B.; Paolo, P.; Ercolino, T.; et al. Hemodynamic Parameters in Patients Undergoing Surgery for Pheochromocytoma/Paraganglioma: A Retrospective Study. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 21, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo-Castro, M.; Pascual-Corrales, E.; Nattero Chavez, L.; Lorca, A.M.; Alonso-Gordoa, T.; Molina-Cerrillo, J.; Álvaro, J.L.; Ojeda, C.M.; López, S.R.; Durbán, R.B.; et al. Protocol for Presurgical and Anesthetic Management of Pheochromocytomas and Sympathetic Paragangliomas: A Multidisciplinary Approach. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021, 44, 2545–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berends, A.M.A.; Kerstens, M.N.; Lenders, J.W.M.; Timmers, H.J.L.M. Approach to the Patient: Perioperative Management of the Patient with Pheochromocytoma or Sympathetic Paraganglioma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, dgaa441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyer, E.J.; Mergeche, J.L.; Anastasian, Z.H.; Kim, M.; Mallon, K.A.; Connolly, E.S. Arterial Blood Pressure Management During Carotid Endarterectomy and Early Cognitive Dysfunction. Neurosurgery 2014, 74, 245–251; discussion 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuRahma, A.F.; Avgerinos, E.D.; Chang, R.W.; Darling, R.C.; Duncan, A.A.; Forbes, T.L.; Malas, M.B.; Perler, B.A.; Powell, R.J.; Rockman, C.B.; et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery Implementation Document for Management of Extracranial Cerebrovascular Disease. J. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 75, 26S–98S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rawi, P.G.; Sigaudo-Roussel, D.; Gaunt, M.E. Effect of Lignocaine Injection in Carotid Sinus on Baroreceptor Sensitivity During Carotid Endarterectomy. J. Vasc. Surg. 2004, 39, 1288–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ramos, A.; Carnevale, J.A.; Majeed, K.; Kocharian, G.; Hussain, I.; Goldberg, J.L.; Schwarz, J.; Kutler, D.I.; Knopman, J.; Stieg, P. Multidisciplinary Management of Carotid Body Tumors: A Single-Institution Case Series of 22 Patients. J. Neurosurg. 2023, 138, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliff, H.A.; El-Boghdadly, K.; Ahmad, I.; Davis, J.; Harris, A.; Khan, S.; Lan-Pak-Kee, V.; O’Connor, J.; Powell, L.; Rees, G.; et al. Management of haematoma after thyroid surgery: Systematic review and multidisciplinary consensus guidelines from the Difficult Airway Society, the British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons and the British Association of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. Anaesthesia 2022, 77, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferrell, J.K.; Shindo, M.L.; Stack, B.C., Jr.; Angelos, P.; Bloom, G.; Chen, A.Y.; Davies, L.; Irish, J.C.; Kroeker, T.; McCammon, S.D.; et al. Perioperative pain management and opioid-reduction in head and neck endocrine surgery: An American Head and Neck Society Endocrine Surgery Section consensus statement. Head Neck 2021, 43, 2281–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamblin, E.; Atallah, I.; Reyt, E.; Schmerber, S.; Magne, J.-L.; Righini, C.A. Neurovascular complications following carotid body paraganglioma resection. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2016, 133, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myatra, S.N.; Julasana, D.A.; Goyal, P. Critical Care Challenges After Head and Neck Surgery. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2025, 31, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netterville, J.L.; Jackson, C.G.; Miller, F.R.; Wanamaker, J.R.; Glasscock, M.E. Vagal Paraganglioma: A Review of 46 Patients Treated During a 20-Year Period. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1998, 124, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dort, J.C.; Farwell, D.G.; Findlay, M.; Huber, G.F.; Kerr, P.; Shea-Budgell, M.A.; Simon, C.; Uppington, J.; Zygun, D.; Ljungqvist, O.; et al. Optimal Perioperative Care in Major Head and Neck Cancer Surgery with Free Flap Reconstruction: A Consensus Review and Recommendations from the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Society. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017, 143, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagrath, R.; Lionello, M.; Grassetto, A.; Bertolin, A. Timing of Tracheostomy in Major Head and Neck Surgery: Preoperative or Intraoperative. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2025, 38, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.