Abstract

Spinal sarcomas are rare, aggressive tumors requiring wide resection that creates large, challenging defects. Conventional reconstruction using allografts or metallic implants is prone to failure in compromised settings like irradiated or infected tissue. This narrative review synthesizes the literature on biologic reconstruction strategies, focusing on vascularized bone grafts (VBGs) and the ‘spinoplastic’ reconstruction approach, to provide a clinical framework for their application. We performed a narrative literature review using PubMed and Scopus to synthesize clinical studies describing biologic spinal reconstruction in compromised host beds. The main findings show that pedicled VBGs (e.g., rib, iliac crest) and free VBGs (e.g., fibula) function as living structural components. ‘Spinoplastic’ reconstruction leverages these grafts to promote biologic fusion, with clinical series reporting high union rates, even in irradiated or revision settings, offering a durable alternative to avascular constructs. Biologic reconstruction using VBGs is a critical strategy for achieving durable spinal stability in these challenging scenarios, and future directions point toward hybrid strategies combining 3D-printed implants with the biologic power of VBGs.

1. Introduction

Primary sarcomas of the spine are rare neoplasms, representing less than 5% of all primary bone sarcomas [1], but their clinical significance far exceeds their incidence. Their location within the spinal column presents unique challenges, as tumor biology and complex anatomy shape treatment planning. Achieving oncologic control through wide resection often requires removing key stabilizing structures, creating substantial defects that demand durable reconstruction. Unlike in the extremities, spinal sarcoma reconstruction must simultaneously restore mechanical stability, preserve neurologic function, and achieve a resilient fusion, often in hostile wound environments created by radiation or prior surgery [2,3].

Historically, conventional methods using structural allografts, non-vascularized autografts, and metallic hardware have been the primary means of restoring spinal stability [4]. While effective in many scenarios, the success of these avascular constructs depends on host revascularization and biological incorporation. In compromised settings such as irradiated tissue beds or revision cases, these approaches are vulnerable to pseudarthrosis, graft collapse, and hardware fatigue, with reported failure rates that can be significant [5,6].

In response to these challenges, biologic reconstruction using vascularized bone grafts (VBGs) has emerged as a critical alternative. By preserving their native blood supply, VBGs function as living structural components which may enhance biological incorporation and promote durable fusion [7]. ‘Spinoplastic’ reconstruction broadly refers to the use of these vascularized tissues to achieve stable arthrodesis [8]. The central premise is that these techniques have the potential to improve fusion rates and reduce long-term hardware-related complications compared to avascular constructs, a topic this review will explore in detail [9].

This narrative review examines the principles, techniques, and reported outcomes of biologic reconstruction for spinal sarcoma defects. We organize these approaches along a conceptual ‘reconstructive ladder’, progressing from conventional methods to more complex vascularized solutions (Figure 1). The aim is to provide a clinical framework for operative planning, helping surgeons select the appropriate reconstructive strategy to achieve durable, function-preserving outcomes in this challenging patient population.

Figure 1.

Enhanced bony reconstructive ladder for spinal sarcoma reconstruction. Reconstructive options are organized from simpler, purely structural solutions (e.g., non-structural autograft, structural allograft, standard cages) to more complex biologic strategies (non-vascularized bone grafts, pedicled VBGs, free VBGs and hybrid PSI–VBG constructs). Progression up the ladder reflects increasing technical complexity and resource requirements, but also greater potential for durable biologic fusion in compromised hosts.

2. Materials and Methods

A structured narrative literature review was performed in February 2024 to identify clinical studies reporting vascularized bone graft–based reconstruction in the spine after tumor resection or in other complex, compromised clinical scenarios. The PubMed and Scopus databases were searched from database inception to February 2024.

The search strategy was designed to combine two main concepts using the “AND” Boolean operator. The first concept included keywords and MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms for the clinical problem (“spinal sarcoma,” “complex spinal reconstruction,” “irradiated spine,” “Spinal Neoplasms,” “spinal infection,” and “pseudoarthrosis.” [MeSH]). The second concept included terms for the biologic solution (“vascularized bone graft,” “VBG,” “pedicled bone graft,” “pedicled rib graft,” “pedicled iliac crest graft,” “pedicled occiput graft,” “pedicled scapular graft,” “free VBG,” “pedicled VBG,” “spinoplastic reconstruction,” “spinoplastics,” and “Bone Transplantation” [MeSH]).

Inclusion criteria were: (1) clinical studies (case reports, case series, cohort studies) or review articles (systematic or narrative) describing biologic reconstruction using vascularized bone grafts; (2) studies focusing on reconstruction after tumor (primary sarcoma or metastatic), infection, or revision for pseudoarthrosis; and (3) articles published in English.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) reports not published in English; (2) reports containing patients under 18 years of age; (3) reports published before 1990; and (4) non-clinical studies (e.g., animal biomechanical, or purely technique-focused papers without included outcomes.

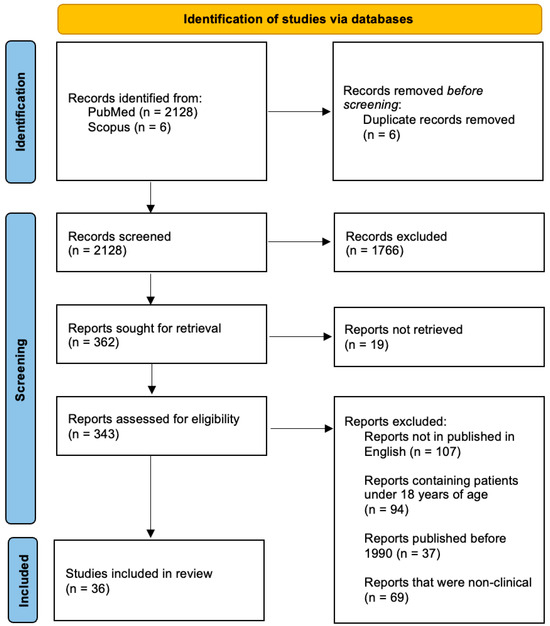

The study selection process is summarized in a PRISMA 2020–style flow diagram (Figure 2) to enhance transparency; however, this review was designed as a narrative rather than a fully systematic review. The initial search identified 2128 records from PubMed and 6 records from Scopus, for a total of 2134 records. After 6 duplicates were removed, one author (T.C.) screened the remaining 2128 titles and abstracts, excluding 1766. This left 362 reports to be sought for retrieval. 19 reports could not be retrieved (full text unavailable), leaving 343 full-text articles for eligibility assessment. Of these, 307 were excluded for specific reasons: reports not published in English (n = 107), reports containing patients under 18 years of age (n = 94), reports published before 1990 (n = 37), and reports that were non-clinical (n = 69). A final 36 studies were included in the narrative synthesis.

Figure 2.

PRISMA 2020-style flow diagram for study selection.

In addition, because oncologic safety concerns around adjunctive biologics may influence reconstructive decision-making, we performed targeted supplemental searches and manual review of reference lists to identify high-quality studies evaluating cancer risk after rhBMP-2 use in spinal fusion. These were not included in the PRISMA flow diagram, as they did not meet the inclusion criteria for VBG-based reconstruction but were used to contextualize the discussion of biologic adjuncts.

Given the narrative and descriptive nature of this review, a formal meta-analysis was not performed. Instead, data regarding study design, patient population, underlying pathology, reconstructive technique, use of radiation, fusion rates, time to fusion, and reported complications were synthesized narratively to construct a clinical framework for applying these advanced reconstructive techniques.

3. Oncologic and Reconstructive Planning

Primary spinal sarcomas are a heterogeneous group of rare tumors, most commonly including chordoma, osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma [10,11]. While their individual biology varies, they share a common clinical challenge: achieving wide, margin-negative resection often requires sacrificing critical stabilizing elements of the spinal column. The resultant defects demand complex reconstruction to prevent catastrophic mechanical failure and preserve neurologic function.

Effective surgical planning is guided by staging systems like Enneking and the Weinstein-Boriani-Biagini (WBB) framework, which map the tumor’s anatomical extent [12]. These systems define the scope of the impending reconstructive challenge and require an assessment of the biological state of the recipient bed. This is particularly critical when considering vascularized bone grafts (VBGs). For example, while preoperative embolization can reduce bleeding, it must be balanced against the need to preserve segmental vessels that supply a potential pedicled graft [13]. Furthermore, a history of radiation or prior surgery creates a compromised biologic environment where the high risk of failure for conventional avascular grafts elevates biologic reconstruction with VBGs to a primary consideration from the outset of planning [14]. This assessment of the defect and the host environment directly informs the selection of an appropriate reconstructive option.

In clinical practice, the choice between avascular constructs (e.g., structural allografts, titanium cages, patient-specific implants) and vascularized bone grafts depends on defect size, host biology, and anticipated adjuvant therapy. Avascular options are most appropriate for smaller segmental defects in well-vascularized beds without prior radiation or infection, particularly in patients with limited life expectancy in whom the time horizon for mechanical failure is shorter. VBGs are largely reserved for large, multi-column defects, revision pseudoarthrosis, irradiated or infected fields, and younger or otherwise fit patients expected to survive long enough to benefit from durable biologic fusion. In these scenarios, the added operative complexity and resource utilization of VBG-based reconstruction are justified by the potential to reduce nonunion and late hardware failure [13,14,15].

4. Conventional Reconstruction: Avascular Grafts and Prosthetics

Conventional reconstruction following spinal sarcoma resection has historically relied on structural allografts, non-vascularized autografts, and prosthetic devices. While these methods provide immediate mechanical stability, they are biologically inert, a factor that can undermine long-term durability, particularly in compromised host environments [15].

4.1. Avascular Bone Grafts (Allografts and Autografts)

Structural allografts are readily available and can be shaped to fit large defects, but their integration depends entirely on ‘creeping substitution,’ a slow process of host revascularization and remodeling that is significantly impaired by radiation [16]. This can lead to high rates of non-union, with some series reporting pseudarthrosis rates approaching 30–40% in complex spinal applications [17]. Non-vascularized autografts (e.g., iliac crest, fibula) offer superior osteogenic potential but are limited by graft size and donor site morbidity, and they remain dependent on a receptive, well-vascularized host bed for incorporation.

4.2. Prosthetic and Custom Implants

Metallic cages (titanium) and expandable prostheses are widely used for anterior column support, offering robust immediate load-bearing capacity. More recently, three-dimensional (3D)-printed patient-specific implants (PSIs) have gained traction, allowing for precise anatomical matching to complex post-resectional defects and optimized biomechanics [18]. However, all prosthetic devices share a fundamental limitation: they are not biologically active. Long-term stability still depends on achieving bony fusion between the implant and the adjacent vertebrae. In the setting of a poorly vascularized or irradiated field, this biologic integration often fails, leading to aseptic loosening, implant subsidence, and eventual hardware fatigue or fracture. While 3D-printed porous titanium surfaces may improve osseointegration compared to smooth PEEK implants, they cannot overcome a profoundly avascular environment [19].

4.3. Limitations of Conventional Approaches

In summary, conventional techniques provide essential tools for immediate mechanical stabilization. However, their reliance on a healthy, well-vascularized host bed makes them vulnerable to failure in the precise clinical scenarios often created by spinal sarcoma treatment. The high rates of pseudarthrosis and hardware failure reported in these settings underscore the need for biologic alternatives that can actively promote fusion in a hostile environment.

5. Pedicled Vascularized Bone Grafts and the ‘Spinoplastic’ Concept

5.1. Principles of Vascularized Bone Grafting

To overcome the biological limitations of conventional methods, vascularized bone grafts (VBGs) serve as living, structural tissues. By preserving their intrinsic blood supply through segmental vessels and periosteal attachments, including Sharpey’s fibers, these grafts function as active osteogenic scaffolds capable of reliable incorporation [20,21]. This biological activity enhances their potential for robust fusion, particularly in compromised host environments like irradiated or infected tissue beds.

The biological superiority of a VBG stems from the preservation of its viable cell population. Unlike an avascular graft, which is merely a scaffold awaiting slow revascularization and repopulation by host cells, a VBG transfers living osteocytes, osteoblasts, and osteoprogenitor cells. This allows the graft to undergo active, primary bone healing and remodeling immediately upon transfer, rather than relying on the much slower process of ‘creeping substitution.’ This retained vitality is also thought to confer greater resistance to infection and allows for more rapid and reliable incorporation, especially in irradiated tissue where host vascular ingrowth is severely compromised [20,21,22].

5.2. The ’Spinoplastic’ Reconstruction Approach: Definition and Technique

In this review, we use the term “spinoplastic reconstruction” to describe a conceptual framework that combines pedicled VBGs with standard spinal instrumentation to biologically augment fusion across large spinal defects. Although this nomenclature is not yet universally adopted across spine oncology, it provides a concise way to refer to this family of techniques [22].

The ‘spinoplastic’ reconstruction approach involves three key components:

- Immediate Stability: Achieved with standard spinal instrumentation.

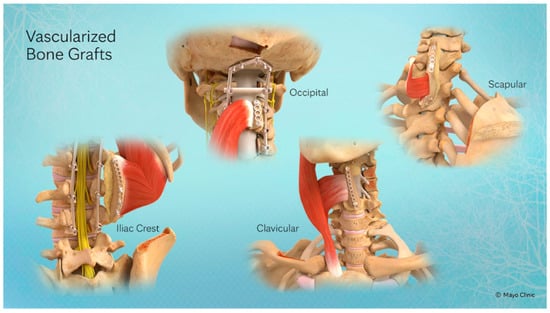

- Biologic Fusion: Promoted by contouring and fixing the pedicled VBG to bridge the osseous defect. This concept is illustrated in Figure 3, which showcases several pedicled VBG options.

Figure 3. Four currently described pedicled VBGs, each vascularized through the connection of their tendons by Sharpey’s fibers and their associated vasculature. From left to right: Iliac Crest pedicled VBG (IC-VBG), Occiput pedicled VBG (O-VBG), Clavicle pedicled VBG (C-VBG), Scapula pedicled VBG (S-VBG).

Figure 3. Four currently described pedicled VBGs, each vascularized through the connection of their tendons by Sharpey’s fibers and their associated vasculature. From left to right: Iliac Crest pedicled VBG (IC-VBG), Occiput pedicled VBG (O-VBG), Clavicle pedicled VBG (C-VBG), Scapula pedicled VBG (S-VBG). - Soft-Tissue Coverage: Often supplemented with local muscle flaps to protect the reconstruction.

5.2.1. Reported Clinical Outcomes

Although extensive longitudinal data on the effectiveness of VBGs has yet to be fully explored, published case series demonstrate successful harvest and exceptional arthrodesis rates for pedicled VBGs in clinical practice (Table 1). In a series of eight patients, Pinsolle et al. reported a 100% osseous union rate for patients undergoing repair of humeral defects with pedicled S-VBGs [23]. Another case series of 18 patients by Wilden et al. demonstrated a 100% fusion rate with the use of rib pedicled VBGs (R-VBGs) in the setting of spinal defect repair secondary to malignancy, injury, and chronic osteomyelitis [24]. The pedicled R-VBG shows promise in a variety of compromised wound beds, including complete arthrodesis in six patients with prior osseous infections and one with spinal metastases [25]. A recent case series by Reece et al. in 2021 with 14 patients confirmed the pedicled IC-VBG can be restorative of spinal form and function in prior failed fusions, further supporting the utilization of these grafts in compromised wound beds [26].

Table 1.

Consolidated summary of key clinical series on vascularized bone grafts (VBGs) for osseous reconstruction.

Although several series of pedicled and free VBGs report fusion rates approaching 100% in complex spinal reconstruction, these results must be interpreted cautiously. Most reports are small, single-center case series with carefully selected patients and limited follow-up and therefore may not capture all instances of delayed union, graft fracture, or construct failure. Despite decreased operative complexity and fewer distant donor sites, donor-site morbidity is also non-trivial. For example, iliac crest VBG harvest is commonly associated with chronic donor-site pain, while rib and fibula harvest can lead to chest wall discomfort, contour deformity, or transient weakness [25,26]. Flap-related complications, including thrombosis, graft loss, wound dehiscence, and repeated operations further contribute to overall morbidity. Acknowledging these trade-offs is important when counseling patients and selecting candidates for ‘spinoplastic’ reconstruction.

5.2.2. Key Advantages in Hostile Environments

The primary advantage of pedicled VBGs is their ability to heal reliably in compromised tissue beds. Radiation therapy severely impairs the revascularization required for avascular graft incorporation; by bringing its own blood supply, a VBG can unite even across an irradiated field. Similarly, in revision surgery for infection, a well-vascularized tissue transfer is more resistant to bacterial colonization and can support local antibiotic delivery, making it a more dependable option for achieving fusion in a contaminated environment [23,24,25,26].

6. Regional Considerations for Biologic Reconstruction

The choice of vascularized bone graft is highly dependent on the anatomical region, the size of the defect, and the availability of local vascular pedicles (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of Biologic Reconstructive Strategies by Spinal Region. This table outlines the primary vascularized bone graft options for defects in the cervical, thoracic, and lumbosacral spine and their respective ranges of motion.

6.1. Cervical Spine

Reconstruction of the cervical spine is uniquely demanding due to the region’s high mobility and proximity to critical structures [27,28]. While the free vascularized fibula graft is the workhorse for large, multilevel anterior column defects, pedicled options exist for specific scenarios. The pedicled vascularized clavicular graft, based on the sternocleidomastoid muscle’s blood supply, has been described for single- or two-level anterior fusions where a shorter graft is sufficient [29]. However, for most sarcoma resections, the robust, straight, cortical strut of the fibula is preferred. Its success hinges on a patent microvascular anastomosis, typically to the superior thyroid or transverse cervical artery [30]. A significant consideration remains donor site morbidity and increased operative time; harvesting the fibula requires meticulous dissection to protect both the donor and recipient sites’ vasculature and nerves which are critical for flap survival during microvascular anastomosis [29,30].

6.2. Thoracic Spine

The pedicled vascularized rib graft is the primary biologic option for thoracic reconstruction, a technique well-supported by clinical series [24,25]. Its long pedicle, based on the posterior intercostal vessels, provides a wide arc of rotation, allowing it to be used as an inlay strut for anterior column defects or, more commonly, as a posterior onlay graft to augment fusion across multiple levels. While inherently stable, en bloc resections in the thoracic spine create large defects requiring a combined approach [31,32]. A key limitation of the rib is its modest structural strength; therefore, it is best suited as a biologic onlay graft to supplement a primary mechanical reconstruction (e.g., a titanium cage), rather than serving as the sole load-bearing element. The key pitfall remains pedicle injury from posterior instrumentation, which must be meticulously protected [24,25].

6.3. Lumbosacral Spine

Reconstruction of the lumbopelvic junction primarily relies on two VBG options: the pedicled iliac crest and the free vascularized fibula. The pedicled iliac crest graft, based on the iliolumbar artery, is a robust source of corticocancellous bone ideal for promoting a solid fusion mass and is the most common choice for this region [26]. For very long-span defects or in cases where the iliac crest is unavailable (e.g., prior harvest, tumor involvement), a free fibula graft can be used [33]. This requires microvascular anastomosis to local recipient vessels like the iliolumbar or superior gluteal artery. Regardless of the VBG chosen, its success is entirely dependent on a mechanical strategy of stable lumbopelvic fixation using iliac or S2AI screws to neutralize the immense cantilever forces at this junction [34,35]. The VBG promotes a solid arthrodesis that allows for gradual load sharing, ultimately protecting the hardware from fatigue failure.

6.4. Perioperative Management and Complication Avoidance

The complexity of ‘spinoplastic’ reconstruction extends into the perioperative period. Meticulous management is required to prevent early complications. For free vascularized grafts, postoperative flap monitoring is essential. This typically involves a combination of clinical assessment (color, turgor, capillary refill) and frequent monitoring with an implantable or external Doppler probe for the first 48–72 h to allow for early detection of vascular thrombosis and timely return to the operating room for salvage.

While there is no universal consensus, many centers utilize a perioperative anticoagulation or antiplatelet regimen (e.g., aspirin, heparin drip) to mitigate thrombosis risk, especially for free flaps. Furthermore, Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols are increasingly being adapted for these long, complex procedures. Key elements include preoperative nutritional optimization, goal-directed fluid management to avoid volume overload, and early mobilization to reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism and deconditioning. A coordinated, multidisciplinary approach to perioperative care is critical to navigating the significant physiological stress of these operations and minimizing morbidity.

7. Future Directions: Integrating Biologics with Modern Technology

A significant recent advance is the use of 3D-printed, patient-specific implants (PSIs), typically made of porous titanium. As detailed in a recent systematic review, these devices offer unparalleled advantages in mechanical design: they can be custom-fabricated to perfectly match complex, asymmetric post-resectional defects, optimizing load distribution and restoring sagittal balance with high precision [18,19]. However, like their predecessors, PSIs are biologically inert [9]. Their long-term success still depends on osseointegration, a process that remains unreliable in the avascular, irradiated environments common in sarcoma treatment.

7.1. The Hybrid Construct: The Next Frontier

At a small number of tertiary academic centers, PSIs are beginning to be combined with intra-prosthetic VBGs to create hybrid constructs. In our practice and in early reports from other high-volume spinal oncology and deformity programs, a custom 3D-printed vertebral body or cage is uniquely designed with a central channel or window to accept a pedicled or free VBG (most commonly a fibula or iliac crest graft). This remains an exploratory strategy rather than a standard of care, with only limited single-institution experiences and no comparative data [18,29].

We therefore present PSI–VBG hybrid reconstruction as a potential future direction that may expand as the design and manufacturing of PSIs becomes more widely available. This approach leverages the best of both worlds:

- Immediate Stability: The custom PSI provides robust, immediate load-bearing capacity and precise anatomical fit.

- Long-Term Biologic Fusion: The intra-prosthetic VBG acts as a living “fusion engine,” creating a solid arthrodesis that integrates the construct and protects the hardware from long-term fatigue failure.

At present, PSI–VBG constructs should therefore be considered an emerging, exploratory strategy suited to highly selected patients in centers with microsurgical and 3D-printing expertise, rather than a broadly generalizable standard approach.

Technical and Biologic Adjuncts

Further refinements will come from other technologies. Advanced preoperative CTA/MRA vascular mapping allows for more precise planning of VBG harvest. Intraoperative navigation and robotics can improve the accuracy of both the tumor resection and the placement of complex instrumentation.

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) represent another potential biologic adjunct for augmenting fusion, but their use in oncologic spine surgery remains controversial. Basic science data demonstrating pro-proliferative and pro-angiogenic effects of BMP signaling have raised concerns regarding tumor promotion. Several retrospective analyses in degenerative lumbar fusion populations have reported small increases in new cancer diagnoses after rhBMP-2 exposure, particularly at higher doses [36]. In contrast, multiple large registry and claims-based studies and independent re-analyses of industry-sponsored trials have not shown a clear increase in malignancy risk, suggesting that any effect is likely to be modest, if present at all. Importantly, these data almost exclusively involve degenerative lumbar fusion; evidence in patients with active or recently treated spinal malignancy is extremely limited [37,38]. As a result, many oncologic spine teams avoid BMP in or near the tumor bed and favor autograft, allograft, or VBG-based biologic strategies instead [29].

Finally, a critical future direction must address the significant cost, resource intensity, and learning curve associated with these advanced reconstructions. Hybrid PSI-VBG constructs and robotic-assisted surgery require substantial institutional investment and logistical coordination between multiple surgical teams (e.g., spine and microsurgery). Establishing clear indications, demonstrating cost-effectiveness, and developing standardized training pathways will be essential for the broader and more equitable adoption of these powerful but complex techniques.

8. Conclusions

Reconstruction following the resection of spinal sarcomas remains a formidable challenge in musculoskeletal oncology. Conventional methods using avascular grafts or prosthetic implants are essential for providing immediate mechanical stability, but they are prone to failure in the compromised biologic environments often created by radiation and revision surgery.

This review highlights the critical role of vascularized bone grafts (VBGs) as a powerful tool for achieving durable biologic fusion in these hostile settings. By providing a living, structural scaffold, pedicled VBGs based on ‘spinoplastic’ reconstructive principles can overcome the limitations of an avascular recipient bed. Clinical series demonstrate that high rates of fusion can be achieved with these techniques across all spinal regions. However, these are complex, demanding procedures associated with significant morbidity, and their success is predicated on meticulous surgical planning and execution.

The future of the field may include hybrid strategies that combine the mechanical precision of PSIs with the biologic reliability of VBGs. Ultimately, the integration of sound biomechanical principles with robust biologic solutions remains the cornerstone of modern, durable reconstruction in spinal oncology.

9. Limitations

This review has several important limitations. Most of the included studies are small, single-center retrospective case series (Level IV evidence), and there are no randomized or prospective comparative data. As such, the strength of any conclusions is limited, and the findings should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating rather than definitive. Direct comparative studies of vascularized versus non-vascularized grafts in spinal oncology are scarce, making definitive claims of superiority difficult to substantiate.

Definitions of fusion, imaging modalities used to assess union, and minimum follow-up intervals varied substantially among the included series, making direct comparison of reported fusion rates and complication profiles difficult. For example, the included studies often lack a standardized timeframe or definition for “bony union,” with variable use of imaging (plain radiography vs. CT) and inconsistent follow-up timing, with some series lacking long-term (e.g., 1 year) follow-up altogether. Furthermore, the included studies often group together heterogeneous patient populations with different tumor histologies and radiation protocols which complicates the interpretation of pooled outcomes. The conclusions drawn should therefore be considered a synthesis of the best available evidence in a data-sparse field, rather than a definitive clinical guideline.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.C. and E.R.; Methodology, T.C.; Investigation (Literature Review), T.C.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, T.C.; Writing—Review and Editing, J.J., N.W.J., J.M. and E.R.; Visualization, T.C.; Supervision, E.R.; Project Administration, E.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ciftdemir, M.; Kaya, M.; Selcuk, E.; Yalniz, E. Tumors of the spine. World J. Orthop. 2016, 7, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oitment, C.; Bozzo, A.; Martin, A.R.; Rienmuller, A.; Jentzsch, T.; Aoude, A.; Thornley, P.; Ghert, M.; Rampersaud, R. Primary sarcomas of the spine: Population-based demographic and survival data in 107 spinal sarcomas over a 23-year period in Ontario, Canada. Spine J. 2021, 21, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zileli, M.; Hoscoskun, C.; Brastianos, P.; Sabah, D. Surgical treatment of primary sacral tumors: Complications associated with sacrectomy. Neurosurg. Focus. 2003, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaresan, N.; Rosen, G.; Boriani, S. Primary malignant tumors of the spine. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 2009, 40, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Chaichana, K.L.; Gokaslan, Z.L.; Aaronson, O.; Cheng, J.S.; McGirt, M.J. Survival of patients with malignant primary osseous spinal neoplasms: Results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from 1973 to 2003. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2011, 14, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brande, R.; Cornips, E.M.; Peeters, M.; Ost, P.; Billiet, C.; Van de Kelft, E. Epidemiology of spinal metastases, metastatic epidural spinal cord compression and pathologic vertebral compression fractures in patients with solid tumors: A systematic review. J. Bone Oncol. 2022, 35, 100446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, P.; Li, D.J.; Auston, D.A.; Mir, H.S.; Yoon, R.S.; Koval, K.J. Autograft, allograft, and bone graft substitutes: Clinical evidence and indications for use in the setting of orthopaedic trauma surgery. J. Orthop. Trauma. 2019, 33, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thalgott, J.S.; Chen, X.; Giuffre, J.M. Single stage anterior cervical reconstruction with titanium mesh cages, local bone graft, and anterior plating. Spine J. 2003, 3, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, T.; Zhang, M.; Yan, J.; Zhao, J.; Pan, W.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q. Comparative analysis of 3D-printed artificial vertebral body versus titanium mesh cage in repairing bone defects following single-level anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion. Med. Sci. Monit. 2021, 27, e928022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evola, F.R.; Costarella, L.; Pavone, V.; Caff, G.; Cannavò, L.; Sessa, A.; Avondo, S.; Sessa, G. Biomarkers of osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strike, S.A.; McCarthy, E.F. Chondrosarcoma of the spine: A series of 16 cases and a review of the literature. Iowa Orthop. J. 2011, 31, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sambri, A.; Gasbarrini, A.; Cialdella, S.; De Iaco, P.; Boriani, S. Pedicled omental flaps in the treatment of complex spinal wounds after en bloc resection of spine tumors. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2017, 70, 1267–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, V.M.; Shaffer, J.W.; Field, G.; Davy, D.T. Biology of vascularized bone grafts. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 1987, 18, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Marrache, M.; Harris, A.; Puvanesarajah, V.; Neuman, B.J.; Buser, Z.; Wang, J.C.; Yoon, S.T.; Meisel, H.J.; Degenerative, A.K.F. Structural allograft versus PEEK implants in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: A systematic review. Glob. Spine J. 2020, 10, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Chaichana, K.L.; Parker, S.L.; Gokaslan, Z.L.; McGirt, M.J. Association of surgical resection and survival in patients with malignant primary osseous spinal neoplasms from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Eur. Spine J. 2013, 22, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, I.R.; Springfield, D.S.; Suit, H.D.; Mankin, H.J. Operative treatment of sacrococcygeal chordoma. A review of twenty-one cases. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1993, 75, 1476–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, J.W.; Field, G.A. Rib transposition vascularized bone grafts: Hemodynamic assessment of donor rib graft and recipient vertebral body. Spine 1984, 9, 448–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirase, T.; Vemu, S.M.; Boddapati, V.; Ling, J.F.; So, M.; Saifi, C.; Marco, R.A.W.; Bird, J.E. Customized 3-dimensional-printed vertebral implants for spinal reconstruction after tumor resection: A systematic review. Clin. Spine Surg. 2024, 37, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, A.; Girdler, S.J.; Mikhail, C.M.; Ahn, A.; Cho, S.K. Biomaterials in spinal implants: A review. Neurospine 2020, 17, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reece, E.M.; Vedantam, A.; Lee, S.; Bhadkamkar, M.; Kaufman, M.; Bohl, M.A.; Chang, S.W.; Porter, R.W.; Theodore, N.; Kakarla, U.K.; et al. Pedicled, vascularized occipital bone graft to supplement atlantoaxial arthrodesis for the treatment of pseudoarthrosis. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 74, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohl, M.A.; Reece, E.M.; Farrokhi, F.; Davis, M.J.; Abu-Ghname, A.; Ropper, A.E. Vascularized bone grafts for spinal fusion—Part 3: The occiput. Oper. Neurosurg. 2021, 20, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riasa, I.N.P.; Reece, E.M.; Mahadewa, T.G.B.; Kawilarang, B.; Jeger, J.L.M.; Awyono, S.; Putra, M.B.; Putra, K.K.; Suadnyana, I.P.R. Occipital vascularized bone graft for reconstruction of a C3–C7 defect. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2024, 12, e6268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsolle, V.; Tessier, R.; Casoli, V.; Martin, D.; Baudet, J. The pedicled vascularised scapular bone flap for proximal humerus reconstruction and short humeral stump lengthening. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2007, 60, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilden, J.A.; Moran, S.L.; Dekutoski, M.B.; Bishop, A.T.; Shin, A.Y. Results of vascularized rib grafts in complex spinal reconstruction. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2006, 88, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Yamano, Y. Use of folded vascularized rib graft in anterior fusion after treatment of thoracic and upper lumbar lesions: Technical note. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2001, 94, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reece, E.M.; Davis, M.J.; Wagner, R.D.; Abu-Ghname, A.; Cruz, A.; Kaung, G.; Verla, T.; Winocour, S.; Ropper, A.E. Vascularized bone grafts for spinal fusion—Part 1: The iliac crest. Oper. Neurosurg. 2021, 20, 493–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaloostian, P.E.; Gokaslan, Z.L. Surgical management of primary tumors of the cervical spine: Surgical considerations and avoidance of complications. Neurol. Res. 2014, 36, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, J.E.; Berk, R.H.; Fuller, G.N.; Rao, J.S.; Abi-Said, D.; Wildrick, D.M.; Gokaslan, Z.L. Chondrosarcoma of the spine: 1954 to 1997. J. Neurosurg. Spine 1999, 90, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulwadood, I.; Gomez, D.A.; Martinez, C.; Bohl, M.; Ropper, A.E.; Winocour, S.; Reece, E.M. Vascularized bone grafts in spinal reconstruction: An updated comprehensive review. Orthoplastic Surg. 2024, 17, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhai, S.; Zhou, H.; Hu, P.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Wei, F. Implant materials for anterior column reconstruction of cervical spine tumor. Orthop. Surg. 2023, 15, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, K.; Ramachandran, V.; Tran, T.M.; Shah, K.P.; Fadhil, M.; Lackey, A.; Chang, N.; Wu, A.-M.; Mobbs, R.J. Systematic review of cortical bone trajectory versus pedicle screw techniques for lumbosacral spine fusion. J. Spine Surg. 2017, 3, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reece, E.M.; Raghuram, A.C.; Bartlett, E.L.; Lazaro, T.T.; North, R.Y.; Bohl, M.A.; Ropper, A.E. Vascularized iliac bone graft for complex closure during spinal deformity surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2019, 7, e2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gore, D.R. The arthrodesis rate in multilevel anterior cervical fusions using autogenous fibula. Spine 2001, 26, 1259–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalfas, F.; Severi, P.; Scudieri, C. Infection with spinal instrumentation: A 20-year, single-institution experience with review of pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, and management. Asian J. Neurosurg. 2019, 14, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebaish, K.M. Sacropelvic fixation. Spine 2010, 35, 2245–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carragee, E.J.; Chu, G.; Rohatgi, R.; Hurwitz, E.L.; Weiner, B.K.; Yoon, S.T.; Comer, G.; Kopjar, B. Cancer risk after use of recombinant bone morphogenetic protein-2 for spinal arthrodesis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2013, 95, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, R.; Selph, S.; McDonagh, M.; Peterson, K.; Tiwari, A.; Chou, R.; Helfand, M. Effectiveness and harms of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in spine fusion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur-Hart, D.J.; Yamamoto, E.A.; Yoo, J.; Orina, J.N. Bone morphogenetic protein and cancer in spinal fusion: A propensity score-matched analysis. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2023, 39, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).