Abstract

In coal mine production processes, conveyor belts are essential components. They play a crucial role in minimizing the risk of belt failure, enabling unmanned operations in hazardous environments, digitally monitoring production metrics, and facilitating timely information feedback, all of which are vital. This paper provides a systematic review of the fundamental concepts, operational principles, and prevalent algorithms associated with conveyor belt detection technology. It summarizes recent research advancements and current applications in key areas while outlining future trends. The paper addresses the challenges of real-time detection during highspeed operations and the identification of defects in various internal filling materials. It evaluates the feasibility of employing methods such as X-ray detection, magnetic flux leakage detection, ultrasonic detection, radio frequency detection, and terahertz wave detection for high-speed conveyor belt inspection and defect identification in filling materials. Based on a comprehensive analysis, terahertz wave detection technology demonstrates significant potential for advancement in non-destructive testing of conveyor belts, owing to its broad applicability and ability to directly identify the location and size of damage. This review aims to provide technical support for selecting testing methods for steel cord conveyor belts.

1. Introduction

Conveyor belts are widely utilized in mines, factories, ports, and analogous environments. They operate under complex conditions and endure prolonged high loads, making them susceptible to internal damage, including joint slippage and core deterioration, which can precipitate catastrophic failures [1]. A breakage in a conveyor belt can disrupt transportation, damage tunnel equipment, compromise the conveyor frame, incur substantial economic losses, extend production downtime, and even result in casualties, leading to severe repercussions. Consequently, real-time diagnosis and monitoring of conveyor belts are crucial for the timely detection of faults, thereby reducing the likelihood of breakage incidents and enhancing safety in coal mining operations.

Four primary technical methods are employed internationally for detecting conveyor belt damage. The first method involves stereo vision and 3D imaging technology, which is predominantly utilized in European and American countries, including the UK. An example of this is the ZLDS202 line laser scanner, which utilizes stereo vision technology in conjunction with line laser and 3D imaging solutions to facilitate contactless installation and achieve high-precision detection. It allows for real-time monitoring of longitudinal and transverse tears, as well as other forms of belt damage, while adapting to various conveyor types and environmental conditions. The second approach is infrared thermal imaging technology, which has been pioneered by Japanese companies. This technique integrates infrared thermal imaging with visible light imaging and employs AI algorithm models to accurately differentiate between tear and wear conditions. Additionally, Germany’s Becker Mining GmbH has developed a second-generation belt tear detection system that incorporates sensing circuits within the belt to monitor loop status in real time [2]. When belt tears compromise the circuit, the system promptly activates an alarm and facilitates temporary repairs of individual loops to ensure detection continuity. The third technology is ultrasonic detection. Australia’s Belt Systems has developed the BG5K and BG10K detectors, which employ ultrasonic waves to assess belt width or changes in signal transmission to identify damage [3]. However, this technology is significantly hindered by dust, dirt, and belt degradation, necessitating further enhancements in detection accuracy. The fourth technology is X-ray detection. A non-destructive testing system, collaboratively designed by the University of Alberta, Canada, and Tianjin University of Technology, China, utilizes Xilinx Virtex-4 FPGA chips to achieve a scanning speed of 4.3 m/s and a resolution of 1.5 mm2, enabling the detection of minute cracks and corrosion on steel-cord conveyor belts [4].

As the world’s largest industrial and coal producer, China possesses the highest number of conveyor belts globally, creating an urgent need for effective conveyor belt damage detection. In addition to the previously mentioned detection methods, Chinese researchers have developed several innovative approaches. This section is represented by Luoyang Weier Ruopu Testing Technology Co., Ltd., (Luoyang,China) (abbrev. TCK.W). Their “TCK.W System,” which employs high-sensitivity weak magnetic sensors, facilitates non-contact online monitoring of internal defects, including broken strands and corrosion in conveyor belts. This technology achieves a positioning accuracy of 1 mm in coal mining environments and exhibits high detection rates for joints and broken strands, having been successfully implemented in practical applications [5]. The second method is acoustic visual fusion technology, exemplified by Anhui Zhizhi. Their patented multimodal detection system (CN119038096B, China) integrates data from visual and acoustic sensors to conduct a comprehensive analysis of cracks and wear, effectively reducing false negatives to below 1%. This technology is particularly well-suited for high-dust environments, such as mines and logistics facilities [6]. Tong Minming’s team applied electromagnetic induction technology to the inspection of coal mine belts. By embedding conductive circuits within the belt, they facilitated real-time monitoring of magnetic field changes, thereby reducing tear detection response time to milliseconds [7]. Additionally, a team from Anhui University of Science and Technology integrated multispectral imaging (MSI) with deep learning to develop a framework for detecting conveyor belt damage. They employed a lightweight, high-precision detection model, YOLOv8-LDH, which decreased the parameter count by 21.93% while achieving an average accuracy of 96.7% [8].

Additionally, technologies such as radio frequency identification (RFID) and terahertz wave detection have also been applied to conveyor belt damage detection, which are introduced sequentially below.

2. Challenges in Conveyor Belts

This article discusses the multifaceted challenges and opportunities associated with the non-destructive testing and evaluation of conveyor belts utilized in various industrial sectors. The complexity of conveyor belts arises from their distinct manufacturing and processing methods, which can lead to a range of defects. These defects may manifest during the initial manufacturing phase or may only become evident after the belts have been put into operation, depending on the stage of development. Through a comprehensive literature review, this study identifies four primary findings:

- At the material and manufacturing level, inherent hidden risks, arise when the quality of raw materials fails to meet established standards, potentially resulting in premature wear and breakage. Defects in the production process, such as uneven thickness of the rubber layer that causes local stress concentration, along with unreasonable structural design, can lead to inadequate core material arrangement density and insufficient edge protection. These issues ultimately hinder the ability to satisfy the demands of heavy-load or high-speed operations.

- Installation and maintenance dimensions (human and management factors): Foreign objects, including metal shavings and sharp debris, were not removed from the surface of the conveyor belt as scheduled, resulting in scratches. Minor wear and fine cracks were not addressed promptly, allowing them to develop into significant defects. The idler rollers were not replaced after becoming stuck, which intensified local friction damage. Additionally, issues such as overloaded transportation and uneven stacking of materials caused the conveyor belt to endure excessive localized loads, leading to deformation or tearing.

- Operating Condition Level (Post-Installation Losses): Prolonged operation under high load conditions leads to fatigue aging of the rubber layer and fatigue fracture of the steel wire rope core. The instantaneous impact forces generated by frequent start-stop operations can readily result in local loosening or tearing of the joints. Additionally, the impact and friction between materials can damage the rubber layer, thereby exposing the core material. Deviations in the conveyor belt and tension imbalances can create excessive friction at the edges, which may manifest as burrs or tears. Excessive tension can easily fracture the core material, while insufficient tension can lead to slippage and wear issues.

- External environmental aspect (environmental erosion): The elevated dust levels and humidity in underground coal mines accelerate the aging of rubber and the corrosion of steel cores. Additionally, corrosive gases present underground, such as combustion products from gas, can impair the performance of both rubber and metal cores. Significant temperature fluctuations, whether in open air or underground, lead to the expansion and contraction of rubber, which diminishes its bonding strength and increases its susceptibility to delamination and cracking.

In summary, concerning the aforementioned issues, while numerous technologies are currently undergoing active research and development, the non-destructive testing of conveyor belts and its associated methodologies remain in their early stages and necessitate further investigation and enhancement. Accordingly, the following topics have been identified as central coordination points. If these areas are continuously advanced, they are anticipated to yield technical solutions to address practical challenges:

Material and Manufacturing Layer: it is essential to ensure that the selected materials are appropriate for the working conditions of the industry. For instance, in the coal industry, material selection for core components must be targeted, prioritizing “coal-specific grade” materials. Specifically, steel core conveyor belts should consist of corrosion-resistant alloy materials to withstand the erosion caused by the humid underground environment and corrosive gases. The rubber layer should utilize a formulation with a wear resistance grade of at least NR70 to endure the friction from coal and the impact of ore. Additionally, the vulcanized joint rubber compound must comply with underground flame-retardant standards, and its bonding strength should be no less than 90% of the strength of the conveyor belt body. The idlers must be of a sealed and waterproof type, meeting IP67 protection standards. Bearings should be lubricated with high-temperature, wear-resistant grease, and the surfaces of the rollers need treatment for anti-slip and wear resistance, such as rubber coating. Furthermore, a dual acceptance mechanism should be established for production quality control. Prior to the departure of products from the factory, essential indicators must undergo spot checks. For instance, the deviation in the spacing of the steel wire rope core should be maintained within ±2 mm, the uniformity error of the rubber layer thickness must be less than 5%, and the vulcanization strength of the joint should adhere to established standards, with tensile tests performed through sampling. Upon receipt of the products, additional inspection is necessary to verify the quality of the conveyor belt.

Installation and Maintenance Dimension: During the installation phase of the conveyor belt, it is essential to implement standardized procedures in conjunction with tailored environmental adaptation plans. The installation process must adhere strictly to industry standards and requirements while employing specific adaptation measures suited to various usage scenarios. For example, in coal industry applications, anti-corrosion treatment of the frame foundation is necessary. This involves applying anti-rust paint followed by an asphalt coating. Additionally, waterproof sealing sleeves should be installed on electrical junction boxes, and dust covers must be added to sensors, including anti-deviation sensors and speed sensors.

Operational condition level: it is essential to prevent overloading and off-center loading of the conveyor belt while ensuring smooth starting, stopping, and speed regulation. The specific measures to achieve these objectives are as follows: First, install belt scales to monitor the load in real time and strictly prohibit exceeding the designed carrying capacity; for coal transportation, it is advisable to maintain the load within 85% of the rated value. Second, implement buffer devices, such as buffer idlers and rubber baffles, at material landing points to mitigate the impact of large ore pieces. Third, install monitoring equipment to facilitate real-time detection of relevant data.

Maintenance level: It is necessary to establish a hierarchical maintenance system that incorporates sensors on vulnerable components, including joints, roller rubber coating areas, convex arc sections, and conveyor belts. These sensors will facilitate real-time monitoring of crack propagation and bonding failures. Additionally, this will enhance the emergency response procedures for addressing defects.

External Environment Dimension: There is a need to establish a hierarchical maintenance system that integrates sensors on critical components, such as joints, roller rubber coating areas, convex arc sections, and conveyor belts. These sensors will enable real-time monitoring of crack propagation and bonding failures. Furthermore, this will improve the emergency response procedures for managing defects.

In addition to emphasizing the direction, the main point is to explore suitable real-time monitoring equipment for conveyor belts.

3. Overview of Non-Destructive Testing Technology

Non-destructive testing (NDT) is a technology used to inspect and evaluate surface or internal defects, performance parameters, and structural conditions of objects without compromising their physical, chemical properties, or functional integrity. The fundamental principle of NDT is to inspect the existing condition of a structure without worsening its properties to ensure safety, reliability, and integrity.

The fundamental principle of non-destructive testing involves the use of the physical properties of materials or workpieces, including acoustics, electromagnetism, optics, and radiation penetrability. By discerning the variations in physical properties—such as density, magnetic permeability, electrical conductivity, and acoustic impedance—between defective and normal regions, and by capturing these differential signals through specialized techniques, it becomes possible to detect and evaluate defects. In Table 1, the fundamental principles, primary advantages, and typical applications of current major non-destructive testing (NDT) technologies are outlined. Additionally, these include phased array ultrasonics, industrial computed tomography (CT), infrared thermal imaging, machine vision, and digital radiography (DR).

Table 1.

Mainstream Non-Destructive Testing Technologies.

4. Current Research Status of Non-Destructive Testing for Conveyor Belts

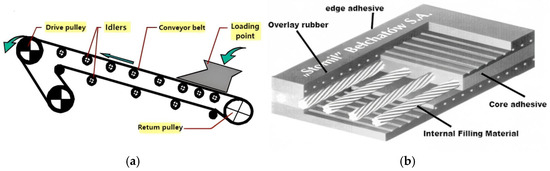

As shown in Figure 1a, the conveyor belt primarily consists of a drive pulley, idlers, the conveyor belt itself, a return pulley, and a loading point. Among these components, the conveyor belt experiences the highest frequency of damage, yet no effective safety detection method exists. As illustrated in Figure 1b, the conveyor belt mainly comprises an internal filler (steel cord or aramid fiber), core rubber, cover rubber, and edge rubber. As conveyor belts accumulate operational time, they may exhibit various defects, such as rubber surface wear, wire breakage, and other forms of damage [9]. To maintain continuous industrial production and ensure worker safety, regular inspection and maintenance of conveyor belts are essential. Presently, several NDT methods are available for detecting defects in conveyor belts, each possessing unique advantages and limitations.

Figure 1.

(a) Simplified diagram of a belt conveyor; (b) Internal structure of a steel cord belt [10].

4.1. Electromagnetic Inspection

Given the widespread use of steel-cord conveyor belts, numerous detection methods have been developed for their assessment. A comparison and analysis of the electromagnetic detection methods currently employed for steel-cord rubber belts is presented in Table 2. As indicated in Table 2, magnetic flux leakage detection is consistent with both research findings and practical applications in the non-destructive testing of conveyor belts. Consequently, the following section will introduce magnetic flux leakage detection technology.

Table 2.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Electromagnetic Detection Methods.

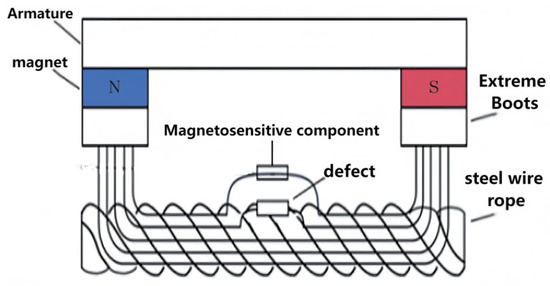

As depicted in Figure 2 and Figure 3, magnetic leakage detection entails the partial magnetization of the steel wire rope core within the steel cord conveyor belt. In the absence of defects, magnetic flux lines converge uniformly within the rope. Conversely, the presence of defects, such as breaks, leads to an increase in magnetic resistance in the vicinity of the defect. This alteration causes a shift in the magnetic flux lines, resulting in the emergence of a magnetic leakage field. Magnetic leakage fields are identified using magnetic-sensitive components, and the signals from these leakage fields are analyzed to facilitate damage detection in steel-cord conveyor belts.

Figure 2.

Principle Diagram of Leakage Magnetic Field Detection for Steel Cord Conveyor Belts [9].

Figure 3.

Schematic Diagram of Leakage Magnetic Field Detection Process.

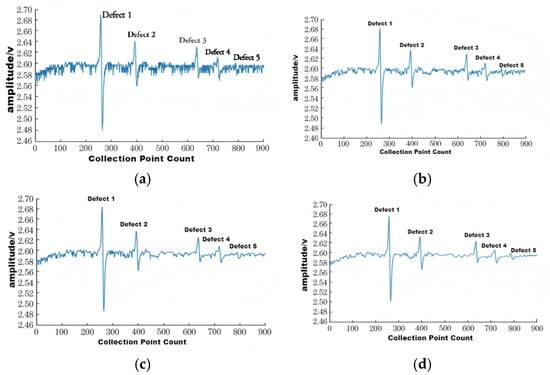

Yang [9] introduced a quantitative method for detecting section losses, simulating broken strand defects in steel cables within conveyor belts. Spherical defects were utilized to represent wear defects in the cables, as depicted in Figure 4. In the realm of signal feature extraction, a combined approach of wavelet denoising and sliding average denoising was implemented, effectively removing signal “spikes” while largely preserving the original signal characteristics. Ryszard Blazej et al. [10] proposed a signal processing algorithm that integrates “magnetic marker differential + multi-channel accumulation” to facilitate damage feature extraction in complex industrial environments. This method, when combined with statistical analysis and 2D visualization, allows for a multidimensional assessment of damage in terms of “location-severity-quantity,” thus addressing the limitations of traditional single-indicator detection. The EyeQ system is illustrated in Figure 5. Wang et al. [11] introduced an excitation device structure that combines radial and axial excitation. Through finite element analysis and theoretical modeling, they optimized the key parameters of this new excitation structure. Su et al. [12] proposed a method that primarily employs permanent magnets to generate a magnetic field, supplemented by an external magnetic field to enhance the accuracy of leakage magnetic signal extraction. Additionally, Hall elements were utilized to improve the device’s detection capability and reduce its size, rendering it more suitable for large-scale multi-channel belt detection. Ren [13] performed high-precision measurements of the joints using high-precision Hall sensors and digital CH-360 gaussmeters. A quantitative analysis was conducted on the pull-out phenomena of both first-order and second-order experimental joints, leading to the formulation of a quantitative evaluation method for the magnetic flux leakage associated with joint pull-out. The errors primarily stemmed from inaccuracies in human measurement readings during the detection process, as well as random errors. Consequently, the results obtained exhibit a defined range of error. Qin et al. [14] integrated leakage magnetic field detection with X-ray inspection. The leakage magnetic field detection identified fault locations, which were subsequently examined through targeted X-ray inspection for non-destructive testing.

Figure 4.

Signal extraction feature diagram: (a) Original signal waveform; (b) Signal waveform after sliding average noise reduction applied to the original signal waveform; (c) Signal waveform after wavelet denoising of the original signal waveform; (d) Noise-reduced signal waveform combining wavelet denoising of the original signal waveform with moving average denoising [9].

Figure 5.

Belt’s steel core condition measurements using modernized EyeQ system installed on two overburden conveyors in one of lignite mines [10].

Magnetic flux leakage detection has progressed from “passively measuring magnetic field amplitude” to “actively optimizing magnetic flux propagation.” By utilizing dual-sensor noise suppression technology (FCR), implementing multi-gap coverage for cross-scale (spatial broadband) detection, and employing high-permeability structures to enhance deep defect signals, this approach effectively mitigates three major challenges associated with traditional magnetic flux leakage detection (MFL): substantial noise interference, limited detection range, and constrained detection depth. Consequently, this advancement significantly expands its applicability [15,16,17,18,19].

4.2. X-Ray Imaging Inspection

X-ray imaging, also known as X-ray Non-Destructive Testing (X-ray NDT), is a method that employs X-rays to penetrate materials and generate images on digital detectors, thereby identifying internal defects within workpieces. X-rays are high-energy electromagnetic waves produced by X-ray tubes or accelerators. According to the Lambert-Beer law, X-rays attenuate in specific patterns as they traverse matter, with relatively lower attenuation observed in regions containing defects. A flat panel detector (FPD) converts the intensity of X-rays into electrical signals, which are subsequently processed digitally to create grayscale images displayed on a screen. Since defect areas exhibit increased X-ray intensity, they manifest as brighter regions within the image. For conveyor belt inspection, practical products are already available, such as the JDB-3 portable flaw detector from Beijing Jitai Instrument, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Beijing Jitai Instrument’s JDB-3 Portable Flaw Detector.

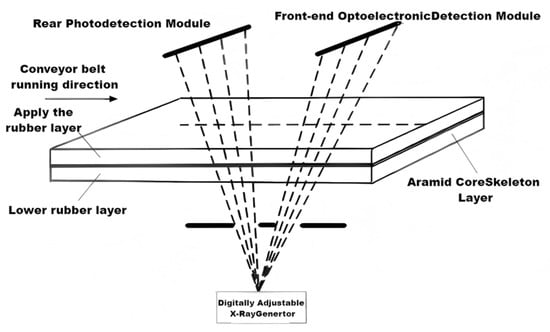

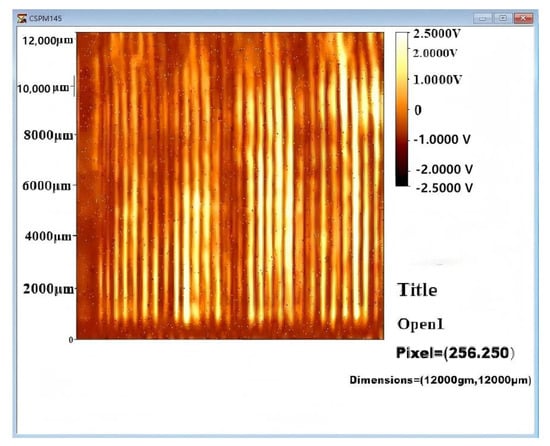

In conveyor belt X-ray imaging non-destructive testing systems, a critical step is the precise texture analysis of real-time video images, which requires highly efficient texture analysis algorithms [20]. Liu et al. [20] employed linear X-ray array technology to capture image sequences of steel-cord conveyor belts during operation. Based on image texture features, they proposed a line-shaped local binary pattern (LBP) texture encoding operator to detect defects in steel-cord conveyor belt images, achieving an average accuracy rate of 90%. Liu et al. [21] generated salient maps by employing the phase spectrum of Fourier transforms, which suppressed low-frequency repetitive components while enhancing high-frequency defect features to highlight rare defect regions in the images. Guo et al. [22] introduced a stereo linear X-ray detection technique for identifying defects in aramid conveyor belts. As illustrated in Figure 7, this method employs stereo X-ray layered imaging to produce a layered three-dimensional display of aramid core conveyor belts, with imaging results shown in Figure 8. For damage detection, the Shufflenet-YOLOv8 model significantly improves the efficiency and accuracy of defect detection in aramid fiber core conveyor belts. Chen [23] utilizes the Sauvola algorithm to determine segmentation thresholds for central pixels, facilitating binary processing within 7 × 7 windows. Noise removal is accomplished through mathematical morphology. This method, when applied under smaller window conditions, exerts minimal effects on segmentation quality while significantly enhancing binary processing efficiency. For training samples, an improved support vector machine (SVM) classification approach was implemented. By refining feature vector selection—through row and column mean compression to reduce dimensions—and simplifying the decision function via iterative learning to decrease the number of support vectors, detection speed increased nearly eightfold with negligible accuracy loss, thereby largely fulfilling real-time detection requirements. Wang [24] successfully developed an FPGA + ARM-based X-ray non-destructive testing system, which enables real-time acquisition, processing, and transmission of conveyor belt images with high detection speed and reliability. In addressing challenges such as high radiation doses in dynamic detection and limitations in static detection associated with traditional X-ray computed tomography imaging, Xu et al. [25] achieved low-dose, high-resolution detection of dynamic objects by optimizing structured sequence illumination, which includes the X-ray source exposure sequence and coded mask patterns, thus overcoming the reliance of existing technologies on static objects.

Figure 7.

Principle of Binocular X-ray Layered Display [22].

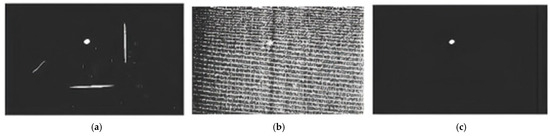

Figure 8.

Layered stereoscopic imaging of an aramid conveyor belt: (a) Upper rubber layer; (b) Aramid core skeleton layer; (c) Lower rubber layer [22].

In recent years, NDT has introduced image restoration; it typically occurs during post-processing and integrated with cumulative NDT inspection process to enrich presentation rather than within the NDT procedure itself. Techniques based on dictionary learning have emerged, utilizing sparse representations to refine image details and address blurring issues. Additionally, methods for correcting projection data have been developed to alleviate clipping artifacts. An X-ray Talbot-Lau interferometer system featuring a scalable rotating grating has been engineered, facilitating dual-mode switching between phase contrast imaging (XPCI) and micro-computed tomography (μCT). This advancement effectively addresses the challenges associated with the detailed inspection of composite materials [26,27,28,29,30,31].

This approach provides several advantages, including non-contact inspection, intuitive defect visualization, a broad detection range, high efficiency and standardization, as well as strong penetration capability. However, it also poses radiation safety risks. In summary, X-ray imaging inspection technology effectively addresses the challenge of visualizing damage in steel cord conveyor belts during non-destructive testing, while simultaneously presenting the issue of ionizing radiation associated with X-rays.

4.3. Ultrasonic Testing

Ultrasonic testing utilizes a probe to emit high-frequency sound waves (greater than 20 kHz) into the material being examined. These waves reflect when they encounter defects, such as cracks, voids, or delaminations, as well as interfaces. A receiving probe captures the echo signals and converts them into electrical signals. By analyzing the characteristics of the echoes, including time, amplitude, and phase, researchers can ascertain the location, size, and nature of the defects.

Ultrasonic pulses of specific energy are generated by exciting the transmission probe and are transmitted through the test object. Defects within the material induce discontinuities along the path of sound wave propagation. Variations in impedance resulting from these defects lead to the production of distinct characteristic signals for different defect types. The echo signals, which contain information about the defects, are then captured by the receiving transducer. Through the analysis and processing of these received echo signals, the damage condition of the conveyor belt can ultimately be assessed [32]. As shown in Table 3, ultrasonic waves produce different phenomena when applied to different types of defects, necessitating corresponding methods for different damage types. As shown in Table 3, different types of defects interact with ultrasonic waves to produce distinct phenomena. In non-destructive testing of conveyor belts, reflection, attenuation, and scattering effects are primarily utilized, with reflection serving as the core mechanism for precisely locating defects and assessing their severity. Additionally, diffraction effects are employed to detect cracks at belt edges or joints.

Table 3.

Interaction Between Ultrasound and Defects.

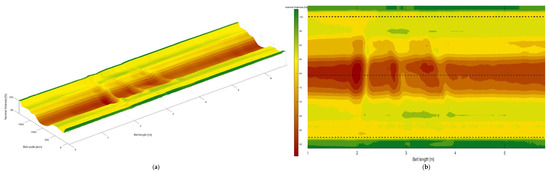

Wang [32] adopted penetrant testing technology to perform non-destructive testing on conveyor belts. Given the material properties of the belts, it is necessary to apply wavelet denoising to the echo signals to reduce noise. Alla Gennadyevna Zakharova et al. [33] introduced a dual-detection mechanism utilizing two sets of ultrasonic sensors: one set of non-contact monitors the conveyor belt edge to identify abnormal width expansion or contraction, which is a typical indicator of longitudinal tears, while the other set emits ultrasonic waves toward the conveyor belt control point to detect drops in signal intensity, indicative of discontinuities in the medium caused by tears. An emergency stop signal is activated when both sensor sets concurrently identify anomalies. Di [34] utilized the Cyclone II FPGA development board to generate pseudo-random sequence (Gold code) excitation signals, perform echo signal cross-correlation operations, and manage timing control. The Gold code modulation of the excitation signal mitigates crosstalk effects, while a 60th-order Chebyshev window FIR filter effectively suppresses noise. Kirjanów-Błażej Agata et al. [35] developed the BeltSonic ultrasonic continuous thickness measurement system, illustrated in Figure 9. This system operates within a measurement range of 20–150 mm, achieving an accuracy of ±0.15 mm and a repeatability of ±0.05 mm. It can accurately detect thickness variations of 0.5 mm or greater, thereby fulfilling the requirements for conveyor belt health monitoring. The detection results are presented in Figure 10. This system represents a reliable technical solution for monitoring conveyor belt thickness, assisting mines in reducing operational costs and enhancing safety. Additionally, it serves as a reference for the application of non-destructive testing (NDT) in conveying equipment.

Figure 9.

Installation of the measuring system on the belt conveyor in the Belt Transport Laboratory [35].

Figure 10.

Test results: (a) 3D image of the test belt fragment; (b) Contour map of the tested belt fragment [35].

Ultrasonic testing offers significant advantages in conveyor belt non-destructive inspection, including high penetration and detection depth, high sensitivity and resolution, non-destructive and real-time capabilities, portable equipment and cost-effectiveness, as well as versatility. However, it also faces limitations, such as its reliance on surface conditions and coupling agents for effective detection, the requirement for operator expertise to accurately interpret results, limited adaptability to various materials and shapes, and the inherent trade-off between low-frequency resolution and high-frequency penetration depth. Despite these challenges, ultrasonic testing has advanced significantly in evaluating overall corrosion conditions and detecting damage in non-metallic components. Nevertheless, the technology still lacks adequate sensitivity for identifying critical defects, such as transverse fractures. To address the impedance mismatch issue inherent in traditional air-coupled ultrasound (ACU), we propose a novel transducer utilizing a bistable fluid switch. To improve the resolution of laser ultrasonic imaging, which can result in misjudgment of defects, we introduce a super-resolution model that integrates up-sampling and down-sampling layers, a multi-layer residual network, and Charbonnier loss. To mitigate significant attenuation in high-frequency ultrasound, we present a pulse compression technique based on frequency-shift keying (FSK) modulation. Additionally, to overcome the challenges posed by detector costs and the limitations of closed-source algorithms, we have developed an open-source, low-cost system based on Arduino [36,37,38,39,40].

4.4. Terahertz Wave Detection

Terahertz (THz) wave detection, an emerging non-contact detection technology, operates by analyzing the dielectric interactions and spectral characteristics of electromagnetic waves with frequencies between 1 and 10 THz and wavelengths ranging from 3 mm to 30 μm. This technology facilitates defect identification through the examination of changes in transmitted or reflected signals. THz imaging utilizes two primary techniques: transmission imaging and reflection imaging.

Terahertz transmission imaging technology employs terahertz sources, including quantum cascade lasers, photoconductive antennas, and free-electron lasers, to generate terahertz waves at specific frequencies or across a broadband spectrum. By utilizing continuous single-frequency terahertz waves as signal carriers, this technology capitalizes on their differential interactions with various materials. When combined with the signal patterns produced by Fabry-Pérot interference, it enables the acquisition of essential transmission intensity data through scanning [41]. Subsequently, algorithms such as back-projection and Fourier transform are utilized to accurately process the recorded information, transforming signal variations into grayscale or color images, as illustrated in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Transparent Steel Cord Core Conveyor Belt Imaging.

Terahertz wave reflection imaging employs focused terahertz waves incident at specific angles, typically perpendicular or 45°, to effectively detect reflected signals from target surfaces. When multiple interfaces are present within an object, a series of temporally separated reflection pulses, akin to echo effects, are generated and can be distinctly identified by terahertz time-domain systems. During the reception of reflected signals, detectors primarily capture parameters such as signal intensity, time delay, and phase. These parameters facilitate surface imaging of the object, while Terahertz Time-Domain Spectroscopy (THz-TDS) technology enables the realization of three-dimensional layered imaging.

The variety of terahertz imaging techniques provides several methods for the non-destructive inspection of conveyor belt damage. Recent advancements in terahertz frequency-modulated continuous-wave (THz FMCW) occlusion removal technology enable deep-layer image recovery, making ultra-fast, high-bandwidth coherent continuous-wave (CW) terahertz spectrometers particularly suitable for online real-time detection applications. Artificial subwavelength structures, including open-loop resonators and metasurfaces, enhance the interaction between terahertz waves and samples, thereby addressing the resolution and sensitivity limitations associated with the longer terahertz wavelength. As a result, terahertz wave detection technology holds considerable promise for progress in the domain of conveyor belt non-destructive testing [42,43,44,45,46].

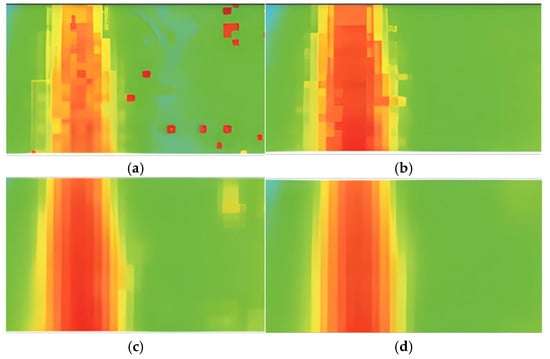

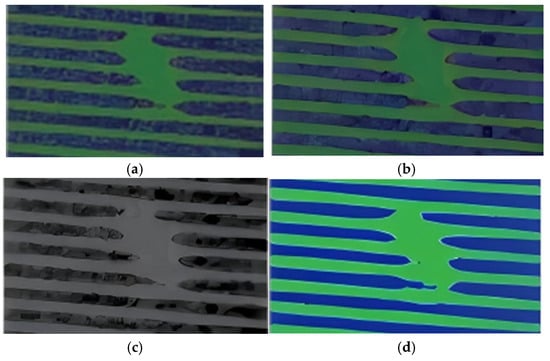

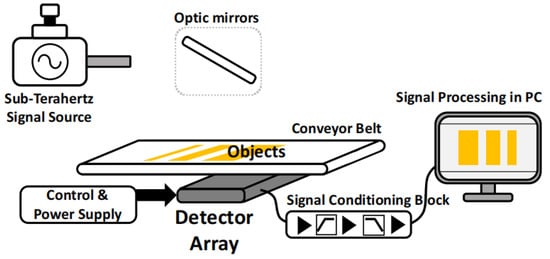

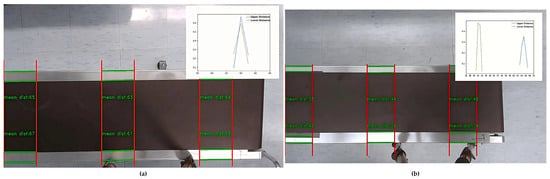

Jiang et al. [47] utilized continuous-wave reflection imaging. To mitigate noise from the imaging system and environment, median filtering was applied for noise removal. The denoised results are presented in Figure 12. Subsequently, the ReliefF algorithm was employed to eliminate redundant features while preserving valid ones. An SVM machine learning model, which integrated grayscale histogram and geometric features, achieved automatic classification of three tear types with an accuracy of 91.6%. Jin et al. [48] implemented terahertz transmissive imaging, as depicted in Figure 13. They employed image processing techniques, including median filtering for noise reduction, histogram equalization, and gamma correction, to enhance contrast. This approach addressed edge blurring and noise interference in terahertz images, thereby improving fracture feature recognition. By enhancing YOLOv7 through multi-module collaboration, their method effectively managed varying fracture scales and dense object detection, achieving an accuracy of 93.1% while satisfying industrial real-time requirements. Moon-Jeong Lee et al. [49] proposed an interleaved array module based on complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) detectors, as illustrated in Figure 14, to improve the resolution of sub-terahertz imaging in conveyor belt systems. By optimizing the detector arrangement and signal processing workflow, they significantly enhanced detection accuracy and system robustness.

Figure 12.

Terahertz images after different filtering operations: (a) Original image; (b) Image after median filtering; (c) Image after mean filtering; (d) Image after bilateral filtering [47].

Figure 13.

Image enhancement effect: (a) Original image; (b) Image after (a) filtering; (c) Image converted via (b) grayscale conversion; (d) Image enhanced by (c) color enhancement [48].

Figure 14.

Sub-terahertz full-wave imaging system for the target objects on a conveyor belt [49].

In industrial NDT, particularly in conveyor belt inspection, this approach presents several advantages: non-contact operation, enhanced safety, strong penetration capabilities, suitability for inspecting multi-layer structures, superior spectral and imaging characteristics, real-time performance, and the ability for online monitoring. Nevertheless, certain limitations persist, including high equipment costs, significant deployment barriers, poor environmental adaptability, trade-offs between penetration depth and resolution, and insufficient technical maturity and industrial validation. Terahertz wave inspection mitigates the drawbacks of ionizing radiation associated with X-rays while preserving the benefits of defect visualization. However, the high cost of terahertz inspection equipment continues to pose a challenge.

4.5. Radio Frequency Detection

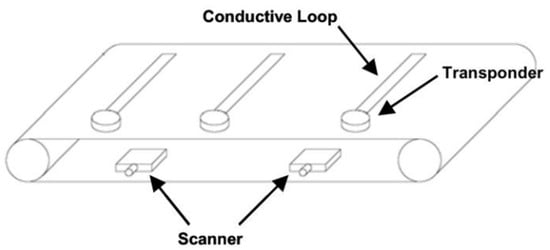

RFID is a technology that leverages the interaction between radio frequency signals and target objects for detection purposes. As depicted in Figure 15, an RFID system generally consists of a transmitter, passive RFID inductive coils, coupling elements, a communication control unit, and a receiver [50]. This technology utilizes passive radio frequency identification based on inductive coupling principles, facilitating the exchange of data, timing information, and energy through high-frequency electromagnetic fields to detect conveyor belt tears without contact. The tear detector host continuously transmits RF signals to query passive RFID tags affixed to the inner side of the conveyor belt or passive RFID electromagnetic induction coil electronic tags embedded within the conveyor system, as illustrated in Figure 16. The electromagnetic induction coil captures RF signals emitted by the receiving coupling probe to generate operating voltage and responds to query commands from the tear detector host. When the conveyor belt remains intact, the tear detection system’s main unit periodically queries the UID information of the electromagnetic induction coil embedded within the belt or the passive RFID tag affixed to its inner side, based on the belt’s operating speed. If a tear occurs in the conveyor belt, disrupting the closed induction loop of the electronic tag, the tag within the electromagnetic induction coil fails to respond to the query command from the tear detection system’s main unit. At this juncture, the main unit assesses the tear condition using timing logic, activates the alarm mechanism, and issues a shutdown control signal, thereby ensuring effective detection and protection against conveyor belt tears.

Figure 15.

Fixed-Mount Inductive Belt Tear Detection System [50].

Figure 16.

Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) Belt Tear Detection System [50].

Thomas Nicolay et al. [50] first proposed the use of radio frequency identification (RFID) technology for non-destructive testing of conveyor belts, providing relevant schematic diagrams of the device. Fang et al. [51] embedded passive RFID electromagnetic induction coils at specific intervals within the conveyor belt to detect tears. When a tear occurs, the detection host fails to sense the signal transmitted by the coils via the coupling probe, which triggers alerts for both the tear and shutdown. Due to the high cost associated with embedding five-element RFID tags in conveyor belts, Shijie Liu et al. [52] opted to attach electronic tags to the back of the conveyor belt. This method protects the tags from damage during operation and reduces costs. Fatema Tuz Zohra et al. [53] pioneered the integration of Ultra-High Frequency Radio Frequency Identification (UHF RFID) with a Machine Learning (ML) monitoring system. This approach facilitates both static and dynamic (up to 5 m/s) detection of conveyor belt cracks. The study utilized a dual-resolution adaptive neural network (BRANN) as the classification model, achieving an accuracy of 99.4% in identifying cracks during motion.

RFID detection provides several advantages, including non-contact operation, enhanced safety, rapid inspection speed, real-time capabilities, broad adaptability, multi-parameter detection, robust anti-interference performance, and ease of integration for intelligent applications. However, it is not without limitations, as detection accuracy can be influenced by various factors. RF detection technology presents a cost-effective solution for wireless monitoring of surface microcracks and their orientation, showcasing considerable strengths in dynamic detection. Nonetheless, this technology also faces challenges, including its inability to effectively detect internal wire damage and limitations in localized monitoring coverage. Current self-interference cancellation (SIC) technology utilizing lossless radio frequency (RF) networks has effectively mitigated self-interference issues arising from antenna mutual coupling. The introduction of the 2.4 GHz dual-probe RF sensor (RFlect) has led to significant cost reductions and performance improvements. Additionally, an RF signal compression algorithm based on Linear Predictive Coding (LPC) has been proposed and integrated into the FAPEC compressor, achieving both “lossless efficiency and lossy adaptability” [54,55,56].

4.6. Machine Vision Inspection

Machine vision inspection technology has been extensively studied for applications involving conveyor belts, with a primary emphasis on detecting surface defects, longitudinal tears, and foreign objects. This study provides an overview of longitudinal tear detection in conveyor belts.

Machine vision inspection employs structured light, polarized light, and other techniques to enhance detection features, such as crack contours. Line-scan cameras are utilized for high-speed continuous scanning of conveyor belts. The acquired images undergo optimization through preprocessing techniques, including noise reduction and contrast enhancement. Defect features are extracted using methods such as edge detection, morphological analysis, or deep learning approaches, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Traditional algorithms typically rely on thresholding or template matching, whereas deep learning models, such as YOLO detection and U-Net segmentation, trained on annotated datasets, facilitate the identification of longitudinal tears in conveyor belts.

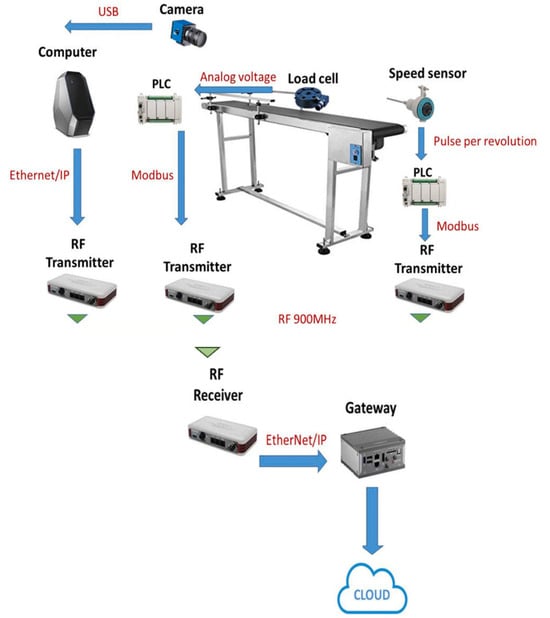

Standalone machine vision systems are vulnerable to complex environmental interferences during practical inspections, leading many studies to integrate linear laser technology with machine vision techniques. Zhang et al. [57] utilized a highly interference-resistant red linear laser device (ZLM25AL650-12GD) and employed adaptive median filtering for noise reduction, alongside OTSU curve fitting to segment laser line regions. They proposed the Hybrid ZS Method—Centroid Approach, which integrates skeleton refinement with weighted centroids to improve the accuracy of laser line center extraction. Additionally, they introduced an ensemble learning voting mechanism to mitigate false detection rates from individual algorithms and enhance classification reliability. Sun [58] applied a linear laser technique to capture features of conveyor belt surfaces. During model training, a multi-dimensional collaborative attention module was incorporated to replace CIoU. Concurrently, angle loss, distance loss, and shape loss were introduced to optimize bounding boxes. Phantom feature maps were generated through linear operations, effectively reducing parameter complexity. Furthermore, L1-regularized sparse training was combined to further refine the YOLOv5s model. Xu et al. [59] employed multi-beam laser and data fusion techniques to improve detection accuracy and anti-interference capabilities. They utilized a grouped center point method to extract centerlines, adapting to the complexities of the underground coal mine environment. Shi et al. [60] enhanced detection reliability in complex environments through triple-line laser redundancy detection and stereo image stitching. For image processing, the authors employed an enhancement algorithm that combines piecewise linear transformation with CLAHE and incorporates improved Otsu threshold segmentation. This approach specifically addresses issues related to uneven illumination and dust or fog interference in underground environments. By concentrating on variations in connected component counts as the primary feature, they mitigated the noise sensitivity commonly associated with traditional edge detection methods. Xiong et al. [61] utilized grid lasers to extract multidimensional features, which facilitated superior recognition of complex tear patterns compared to single-line lasers. Adaptive binarization and corner correction further enhanced robustness under low-light and dusty conditions. Qiao et al. [62] employed multiple light sources, including lasers and area lights, to improve feature contrast while refining algorithms such as Harris corners and K3M + Hough lines to enhance recognition accuracy. Their system achieves an overall feature recognition rate exceeding 90% and an early warning accuracy rate also above 90%, with a single-frame processing time of 1.6 ms, thereby meeting industrial application requirements. Yang et al. [63] developed a machine-vision-based online detection system aimed at identifying common faults in coal mine conveyor belts, including longitudinal tears and misalignment. This system utilizes high-brightness line light sources and line-scan CCD cameras to capture high-quality images. By integrating edge detection, column threshold segmentation, and fault feature extraction algorithms, it effectively balances processing speed with accuracy, achieving a single-frame processing time of ≤50 ms to reliably identify longitudinal tearing and deviation faults. Zhang et al. [64] integrated high-speed FPGA processing with non-contact machine vision inspection, thereby overcoming the reliability limitations of traditional contact-based detection and enhancing interference resistance in complex environments. Zhang [65] employed a genetic algorithm-optimized Lee filter model to effectively eliminate Gaussian and salt-and-pepper mixed noise while preserving edge details and enhancing image quality. He proposed the ICS-SA (Iterative Clone Selection) fusion algorithm, which is based on a non-complete Beta function model and automatically optimizes parameters to improve image contrast, emphasize wear area details, and adapt to varying lighting conditions. Jose Chamorro et al. [66] developed a conveyor belt health monitoring solution using machine vision techniques (Canny edge detection and Hough line transform) integrated with real-time sensor data, as shown in Figure 17. This research successfully established a conveyor belt health monitoring system capable of real-time monitoring and remote early warning for three parameters. The system demonstrated reliable communication and monitoring performance, with detection results illustrated in Figure 18. Guo et al. [67] proposed a method for detecting conveyor belt damage that integrates CenterNet with Fusion Knowledge Distillation (FKD). This method allows the lightweight ResNet18 model to achieve a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 92.53% while enhancing processing speed to 65.8 frames per second (FPS), thereby satisfying the requirements for deployment on edge devices. Furthermore, the image acquisition module employs a line-scan industrial camera, which contributes to cost reduction.

Figure 17.

Architecture of the conveyor belt monitoring system [66].

Figure 18.

Test results: (a) Image of video analytics for an aligned case; (b) Image of video analytics for a misalignment case [66].

Machine vision technology provides several advantages for the detection of longitudinal conveyor belt tears, including real-time and continuous monitoring, high-precision defect identification with quantifiable capabilities, non-contact inspection that incurs low maintenance costs, and multidimensional data fusion with early warning functionalities. Nonetheless, it also encounters challenges such as detection in complex environments, technical difficulties stemming from the surface characteristics of conveyor belts (including texture complexity, environmental interference, motion speed, and synchronization of image acquisition), limitations in algorithm generalization due to the scarcity of defect samples, and substantial initial investment along with ongoing maintenance costs.

4.7. Alternative Detection Methods

4.7.1. Combining Multispectral Imaging with Deep Learning

Chen et al. [17] introduced the first application of multispectral technology for conveyor belt damage detection by developing a multispectral imaging system that spans the 675–975 nm wavelength range. They implemented a band selection strategy based on the Optimal Index Factor (OIF), selecting a combination of information-rich and low-correlation bands (1, 13, 25) to create pseudo-RGB images, which enhanced feature expression capabilities. Concurrently, they optimized the YOLOv8 detector head architecture. By incorporating parameter-sharing convolutional layers (ShareConv), independent Batch Normalization (BN) layers, and scale adjustment modules, they achieved a 21.93% reduction in detector head parameters while maintaining multi-task decoupling properties, thus facilitating model lightweighting. Nonetheless, this technology encounters challenges, including an inability to detect internal damage, reliance on surface cleanliness, a complex system structure, and high costs, which currently limit its adoption.

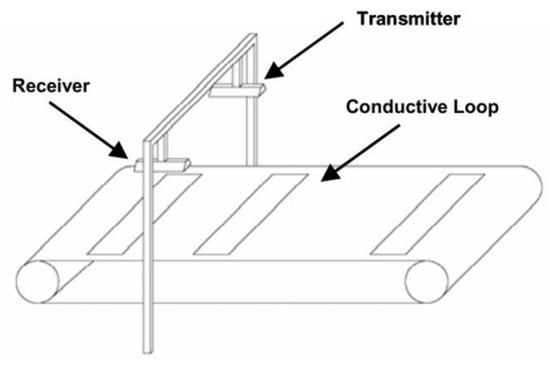

4.7.2. Embedded Inductive Loop

Tong et al. [8] incorporated double-loop-shaped conductive circuits at regular intervals (approximately every ten meters) within the rubber layer during conveyor belt production. An electromagnetic field excitation device and a detection device are positioned beneath the conveyor belt. The excitation device, situated on one side of the belt’s centerline, comprises multiple units that produce a rectangular electromagnetic field using alternating current. Conversely, the detection device, on the opposite side of the centerline, may have slightly fewer units than the excitation device. To account for the lag effect in electromagnetic field propagation, the detection device must be placed at a specific distance behind the excitation device along the belt’s direction of movement. In the event of a longitudinal tear in the conveyor belt, the wire loop is severed, disrupting the induced current generation and causing the detection device to fail in sensing the electromagnetic field induced by the double-loop wire, indicating a longitudinal tear fault. This technology necessitates extensive retrofitting of current conveyor belts, entails high engineering complexity, poses risks of loop damage, and presents significant challenges for subsequent maintenance. Furthermore, this technology has limited functionality, as it cannot detect non-disconnecting damage and can only provide alarms post-incident.

Table 4 presents the previously discussed non-destructive testing technologies for conveyor belts along with their evaluation criteria. It highlights the application stages of each technology based on practical requirements, as well as their respective advantages and limitations. Non-destructive testing and evaluation technologies for conveyor belts have fundamentally progressed through several developmental phases. Emerging methods, including terahertz wave inspection, machine vision inspection, and radio frequency inspection, remain in the early stages of application. In contrast, more established technologies, such as X-ray and ultrasonic inspection, have advanced to field testing. Nonetheless, X-ray inspection raises concerns related to ionizing radiation, while ultrasonic inspection encounters challenges such as difficulties in signal interpretation, high operator training requirements, and limitations in accurately assessing defects within conveyor belt fillers and their sizes. Given the complex non-destructive testing environment of conveyor belts and the practical challenge of high operating speeds, the integration of multimodal sensor fusion with artificial intelligence facilitates more precise detection of belt defects. However, collaborative approaches that utilize multiple technologies face significant implementation challenges and high costs. This underscores the advantages of terahertz wave detection, which, despite being relatively expensive, offers excellent penetration of non-metallic materials and immunity to environmental interference.

Table 4.

Summary and Overview of NDT Techniques for Conveyor Belts [68].

5. Summary and Outlook

As a critical component in industrial settings such as mines and ports, the operational safety of conveyor belts is intrinsically linked to both production efficiency and personnel safety. However, the multifaceted nature of defect issues under complex working conditions presents a significant challenge in the realm of non-destructive testing. From a causal perspective, defects may arise from several sources: raw material imperfections during the manufacturing stage, irrational structural design, non-standard operational practices, and overlooked hazards during installation and maintenance. Additionally, the fatigue aging resulting from prolonged high-load operation, along with corrosion and wear due to harsh environmental conditions, contributes to various defects in conveyor belts, including internal wire breakage, joint slippage, and longitudinal tearing. Furthermore, the task of conducting real-time detection and identifying internal filler defects during high-speed operation has emerged as a notable technical challenge.

Currently, mainstream non-destructive testing technologies for conveyor belts each possess distinct advantages and limitations. Magnetic particle leakage detection, ultrasonic testing, and X-ray imaging technologies have reached a level of maturity, offering technical support for metal core defect detection, internal damage identification, and penetrating imaging, respectively. However, these methods face challenges such as limited material applicability, dependence on professionals for signal interpretation, and the potential exposure to ionizing radiation. Machine vision is proficient in the dynamic monitoring of surface defects and non-contact detection; however, it is susceptible to environmental interference and struggles with identifying internal damage. Although radio frequency detection technology can inspect the interior, it is limited to detecting the core of steel wire ropes and often necessitates modifications in conveyor belt manufacturing processes. Terahertz wave detection technology, characterized by its lack of ionizing radiation, strong penetration, and high resolution, can accurately locate the position and size of damage and is compatible with various types of fillers, making it a highly promising avenue for technological advancement. Nonetheless, challenges such as high equipment costs and inadequate environmental adaptability remain unresolved. The current landscape of these technologies suggests that no single detection method can effectively balance detection accuracy, real-time performance, and safety. Therefore, the integration of multiple technologies and targeted technological innovations are essential for addressing these challenges.

In the future, the advancement of non-destructive testing technology for conveyor belts will concentrate on three primary areas: “overcoming core bottlenecks, enhancing technological integration, and increasing practical value.” In the realm of core technological breakthroughs, terahertz wave detection technology is anticipated to emerge as a pivotal development focus. As device manufacturing processes continue to improve and market demand expands, the costs associated with this technology are expected to decline gradually. By optimizing anti-interference algorithms and designing for environmental adaptability, current challenges—such as achieving a balance between penetration and resolution, as well as ensuring applicability in high-humidity and dusty conditions—can be effectively resolved. This progress will facilitate the transition from laboratory settings to widespread industrial applications.

Author Contributions

L.S.: manuscript—original draft preparation. W.Z.: manuscript—review and editing. J.Z.: technical principles and writing—review and editing. C.P.: analysis, interpretation of data, and manuscript—review and editing. Z.Y.: manuscript—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Major Cultivation Project of Institute of Energy, Hefei Comprehensive National Science Center (Anhui Energy Laboratory)—Development of a Multimodal Terahertz Near-Field “Electron Microscope” System (No. 25KZS212). The APC was funded by the same project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed in this review are derived from publicly available sources or previously published studies. Specific references to these data, including the corresponding literature DOI, public database names (e.g., PubMed Central, TCGA), and data accession numbers (where applicable), are provided in the References section of this article. No new raw data were generated in the course of this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Peng, C.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, F.; Yu, Z.; Song, L.; Li, X. A Novel Conveyor Belt Internal Defect Detection Device. China Patent CN118641561A, 13 September 2024. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, N.; Wen, F.; Li, Q.; Chen, L.; Zhou, R. Review on detection technology of conveyor belt rip. Coal Eng. 2022, 54, 79–85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zakharov, A.; Geike, B.; Grigoryev, A.; Zakharova, A. Analysis of Devices to Detect Longitudinal Tear on Conveyor Belts. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 174, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Miao, C.; Cui, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhou, L. Research of X-ray Nondestructive Detection System for High-speed running Conveyor Belt with Steel Wire Ropes. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2009, 1, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dou, B. An Automatic Monitoring System and Monitoring Method for Steel Cord Conveyor Belts. China Patent CN108082886B, 15 March 2024. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Zhai, R.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, S.; Lu, F.; Shu, Z. A Multimodal Conveyor Belt Crack Detection Method and System. China Patent CN119038096A, 29 November 2024. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, M.; Hu, F.; Gao, L.; Wang, K. YOLOv8-LDH: A lightweight model for detection of conveyor belt damage based on multispectral imaging. Measurement 2025, 245, 116675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.; Wang, B.; Jiang, C.; Tong, Z.; Tang, S. New Detection Method for Longitudinal Tear of Conveyor Belt in Coal Mine. Coal Mine Mach. 2013, 34, 191–193. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Meng, C.; Zhao, Y. Magnetic leakage detection for damage of wire rope core conveyor belts. Non-Destr. Test. 2024, 46, 18–23. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Blazej, R.; Jurdziak, L.; Zimroz, R. Novel Approaches for Processing of Multi-Channels NDT Signals for Damage Detection in Conveyor Belts with Steel Cords. Key Eng. Mater. 2013, 2579, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shen, Z.; Ji, Z.; Wang, S.; He, H. Design and Optimization of Excitation Structure of Steel Rope Core Conveyor Belt Based on Leakage Magnetism. Instrum. Technol. Sens. 2024, 10, 39–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Su, Q.; Luo, H.; Xu, Z.; Chen, H. Research on Electromagnetic Testing Method and Experiment of Wire Ropes Conveyer Belt. Dev. Innov. Mech. Electr. Prod. 2010, 23, 119–121. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ren, K. The Leakage Magnetic Field Distribution Analysis and Twitch Quantitative Evaluation of Coal Mine Steel Wire Rope Core Conveyer Belt Joint. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Science and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Qin, W.; Shen, H. Application Study of Integrated Nondestructive Test for Steel Cord Conveyer Belt. Coal Mine Mach. 2018, 39, 138–140. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Su, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z. A Novel Non-destructive Testing Method by Measuring the Change Rate of Magnetic Flux Leakage. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 2017, 36, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Li, E.; Chen, X.; Wu, J.; Zhu, J.; Kang, Y. A Spatial Broadband Magnetic Flux Leakage Method for Trans-scale Defect Detection. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 2022, 41, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, W.; Li, E.; Kang, Y. Magnetic Flux Leakage Course of Inner Defects and Its Detectable Depth. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2021, 34, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Wu, J.; Tu, H.; Tang, J.; Kang, Y. A Review of Magnetic Flux Leakage Nondestructive Testing. Materials 2022, 15, 7362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.W.; Park, S. Magnetic flux leakage–based local damage detection and quantification for steel wire rope non-destructive evaluation. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2017, 29, 3396–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Guo, D.; Shen, H.; Qin, W. Defect Detection Algorithm Based on X-Rays Steel-Core-Belt Images. J. Test. Technol. 2016, 30, 45–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Miao, C.; Li, X. An Algorithm Based on PFT for Defect Recognition of X-Ray Steel Rope Cord Conveyer Belt Image. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 2467, 572–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Liu, X.; Tang, J.; Zhang, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y. Nondestructive Testing Method of X-ray for Mining Aramid Conveyor Belt. Coal Mine Mach. 2025, 46, 192–194. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Defect Detection Based on X-ray Image of Conveyor Belt. Master’s Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2015. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Study on Mechanical Automation with X-Ray Power Conveyor Belt Nondestructive Detection System Design. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 2489, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, D.; Cuadros, A.; Mao, T.; Zhao, Q.; Arce, G.R.; Xu, T. Conveyor X-Ray Tomosynthesis Imaging With Optimized Structured Sequential Illumination. IEEE Photonics J. 2020, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzer, H.; Komjak, N.I.; Pelix, E.A.; Mitterfellner, K. Röntgenblitzgeräte und Röntgenimpulstechnik in der zerstörungsfreien Prüfung / X-ray flash instruments and X-ray pulse technique in non-destructive testing / Appareils et technique de rayons X pulsés dans essais non destructifs. Mater. Test. 2021, 20, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Yim, D.; Lee, S. Development of a truncation artifact reduction method in stationary inverse-geometry X-ray laminography for non-destructive testing. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2020, 53, 1626–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.A.; Kim, K.S.; Park, C.K.; Lee, D.Y.; Cho, H.S.; Seo, C.W.; Kang, S.Y.; Lim, H.W.; Lee, H.W.; Park, S.Y.; et al. Dictionary-learning-based image deblurring for improving image performance in x-ray nondestructive testing. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2018, 924, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Kang, S.Y.; Kim, W.S.; Cho, H.S.; Park, C.K.; Lee, D.Y.; Kim, G.A.; Park, S.Y.; Lim, H.W.; Lee, H.W.; et al. Improvement of radiographic visibility using an image restoration method based on a simple radiographic scattering model for x-ray nondestructive testing. NDT E Int. 2018, 98, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, N.; Kimura, K.; Shirai, T.; Doki, T.; Sano, S.; Horiba, A.; Kitamura, K. Talbot–Lau interferometry-based x-ray imaging system with retractable and rotatable gratings for nondestructive testing. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2020, 91, 023706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wajid, A.M.; Abdelnour, M.R.; Naz, A.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J. X-ray backscattering: Design, applications, and prospects in non-destructive evaluation. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2025, 334, 3033–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. The Design of Coal Converyor Belt with Ultrasonic Intact Detection System. Master’s Thesis, North China University of Technology, Taiyuan, China, 2016. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zakharova, A.G.; Zakharov, A.Y.; Lobur, I.A.; Shauleva, N.M. Ultrasonic based device to detect longitudinal tears on conveyor belts. Min. Equip. Electromechanics 2022, 162, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, S. Ultrasonic Inspection System Development of Conveyer Belt Surface Based on FPGA. Master’s Thesis, East China University of Science and Technology, Shanghai, China, 2014. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Agata, K.B.; Leszek, J.; Ryszard, B.; Aleksandra, R. Calibration procedure for ultrasonic sensors for precise thickness measurement. Measurement 2023, 214, 112744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiñeira-Ibáñez, S.; Tarrazó-Serrano, D.; Rubio, C. Acoustic and Ultrasonic Sensing Technology in Non-Destructive Testing. Sensors 2025, 25, 3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulgonul, S. Development and testing of a low-cost ultrasonic leak detector. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2025, 107, 103075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühling, B.; Maack, S.; Strangfeld, C. Fluidic Ultrasound Generation for Non-Destructive Testing. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2311724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuta, H.; Sakai, K. High sensitivity detection of ultrasonic signal for nondestructive inspection using pulse compression method. Microelectron. Reliab. 2019, 92, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, G.; Luo, K.; Zhang, X. Ultrasonic Nondestructive Testing Image Enhancement Model Based on Super-Resolution Imaging. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.B.; Machado, M.A.; Bonfait, G.J.; Vieira, P.; Santos, T.G. Continuous wave terahertz imaging for NDT: Fundamentals and experimental validation. Measurement 2021, 172, 108904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofani, E.; Friederich, F.; Wohnsiedler, S.; Matheis, C.; Jonuscheit, J.; Vandewal, M.; Beigang, R. Nondestructive testing potential evaluation of a terahertz frequency-modulated continuous-wave imager for composite materials inspection. Opt. Eng. 2014, 53, 031211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Wang, T.; Shen, S.; Hao, C.; Liu, D.; Liu, J.; Wang, K.; Yang, Z. Occlusion Removal in Terahertz Frequency-Modulated Continuous Wave Non-Destructive Testing Based on Inpainting. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S. Progress in terahertz nondestructive testing: A review. Front. Mech. Eng. 2018, 14, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsengiyumva, W.; Zhong, S.; Zheng, L.; Liang, W.; Wang, B.; Huang, Y.; Chen, X.; Shen, Y. Sensing and Nondestructive Testing Applications of Terahertz Spectroscopy and Imaging Systems: State-of-the-Art and State-of-the-Practice. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebermeister, L.; Nellen, S.; Kohlhaas, R.; Breuer, S.; Schell, M.; Globisch, B. Ultra-fast, High-Bandwidth Coherent cw THz Spectrometer for Non-destructive Testing. J. Infrared Millim. Terahertz Waves 2019, 40, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ling, P.; Xu, W. Research on Conveyor Belt Tear Detection and Classification Based on Terahertz Imaging. J. Test Technol. 2024, 38, 100–108. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.; Li, J.; Liu, Z. Study on Conveyor Belt Wire Rope Core Breakage Detection Based on Improved YOLOv7. J. Lanzhou Inst. Technol. 2025, 32, 26–31. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.-J.; Lee, H.-N.; Lee, G.-E.; Han, S.-T.; Kang, D.-W.; Yang, J.-R. CMOS Detector Staggered Array Module for Sub-Terahertz Imaging on Conveyor Belt System. Sensors 2023, 23, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolay, T.; Treib, A.; Blum, A. RF identification in the use of belt rip detection [mining product belt haulage]. Sensors 2004, 1, 333–336. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, C. Design and Application of Conveyor Belt Tear Detection System Based on Passive RFID Technology. Coal Mine Mach. 2019, 40, 115–117. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Liu, G.; Zhu, Y. Research on Application of Strong Belt Transporter Vertical Tear Protection Based on Radio Frequency Identification Technology. Coal Mine Mach. 2019, 40, 40–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zohra, F.T.; Salim, O.; Dey, S.; Masoumi, H.; Karmakar, N.C. Machine Learning Approach to RFID Enabled Health Monitoring of Coal Mine Conveyor Belt. IEEE J. Radio Freq. Identif. 2023, 7, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, A.; Portell, J.; Riba, J.; Mas, O. Context-Aware Lossless and Lossy Compression of Radio Frequency Signals. Sensors 2023, 23, 3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askar, R.; Keusgen, W. Lossless Decoupling Networks for RF Self-Interference Cancellation in MIMO Full-Duplex Transceivers. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2023, 41, 2765–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samolej, K.; Ślot, M.; Busiakiewicz, A.; Ślot, M.J.; Zasada, I. Radio-frequency sensor for non-destructive evaluation of composite materials. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Qi, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D. A method for distinguishing the tear of mine conveyor belt based on the hybrid ZS method and the centroid method. Coal Process. Compr. Util. 2023, 7, 8–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y. Research on Conveyor Belt Tear Detection Technology Based on Machine Vision Master’s. Master’s Thesis, Qilu Institute of Technology, Jinan, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Liu, L.; Shen, K.; Zou, S. Longitudinal tear detection of belt conveyor based on multi linear lasers. Ind. Min. Autom. 2021, 47, 37–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Shi, H.; Wang, Y.; He, J.; Ni, D. Research on longitudinal tear detection of mining conveyor belt based on machine vision. China Min. 2024, 33, 141–151. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, H.; Zhou, R.; Chen, L. On-line detection of conveyor belt tearing based on machine vision. Coal Eng. 2022, 54, 182–186. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, T.; Li, X.; Pang, Y.; Lü, Y.; Wang, F.; Jin, B. Research on conditional characteristics vision real-time detection system for conveyor belt longitudinal tear. IET Sci. Meas. Technol. 2017, 11, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Miao, C.; Li, X.; Mei, X. On-line conveyor belts inspection based on machine vision. Optik 2014, 125, 5803–5807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Huang, H.; Jin, B. Research on Anti Longitudinal Tearing System of Belt Conveyor Based on Machine Vision. Coal Technol. 2023, 42, 149–151. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Research on Intelligent Identification and Repair Technology of Mine Conveyor Belt Fault. Ph.D. Thesis, Liaoning Technical University, Fuxin, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro, J.; Vallejo, L.; Maynard, C.; Guevara, S.; Solorio, J.A.; Soto, N.; Singh, K.V.; Bhate, U.; G.V.V., R.K.; Garcia, J.; et al. Health monitoring of a conveyor belt system using machine vision and real-time sensor data. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2022, 38, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Liu, X.; Gardoni, P.; Glowacz, A.; Królczyk, G.; Incecik, A.; Li, Z. Machine vision based damage detection for conveyor belt safety using Fusion knowledge distillation. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 71, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqar, M.; Memon, A.M.; Sabih, M.; Alhems, L.M. Composite pipelines: Analyzing defects and advancements in non-destructive testing techniques. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 157, 107914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).