Abstract

Simplified and scalable models of physical systems are extremely valuable in a variety of different engineering fields to test and diagnose particular modes of failure and optimize build conditions. In this work, we develop a practical method to prepare and analyze giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) for detailed biophysical interrogations. The method is rapid, scalable, and versatile, where characterization of lipid membrane conformational changes can be performed on multiplexed samples using tissue culture plates and a convenient, high-throughput fluorescence microscopy setup. The simplicity of the setup is enabled by an AI image recognition model that, when trained on the appearance of GUVs in the images, outperforms other image segmentation methods such as the watershed algorithm or the Hough transform. The method allows for the rapid quantification of entire 96-well plates containing in total O (1,000,000) GUVs and provides a potential testbed for the development of drugs. We highlight the power of our system by including large-scale data on the screening of lipophilic analogs of the small molecule antimetabolite carmofur.

1. Introduction

Giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) are simple membrane compartments composed of a single lipid bilayer wrapped typically in the shape of a bubble with sizes ranging from 1 to 100 µm in diameter [1,2,3]. Their large macromolecular lipid structures make them easily observable through conventional fluorescence microscopy techniques and, given their compositional similarities to the cell plasma membrane, are of particular interest as model systems for probing fundamental biophysical phenomena [1,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Notable examples of elucidative biophysical interrogations include studies on phase behavior of multicomponent lipid mixtures [10,11,12,13], integral membrane protein transport studies [14,15], mechanical and tension properties [16,17,18], and protein docking systems [19,20] akin to the recently discovered hemifusome organelle, to name a few [21]. GUVs have also been investigated for applications in drug delivery due to their ability to carry drugs with higher payloads than their nanometer-sized lipid counterparts [22,23,24].

First developed by Bangham and coworkers, ref. [25], the gentle hydration method of GUV preparation is performed by layering a lipid solution held in an organic solvent onto a glass surface, allowing for the lipid to dry, and rehydrating the consequent lipid-coated glass with an aqueous solution [22,26]. After allowing ample time for the lipid to bud off of the film, the resulting GUVs are harvested and sedimented before imaging. Various conditions, such as the surface the lipid is initially spread over [27], the salt conditions of the hydration solution [28,29], the internal and external sugar concentrations [30,31,32], and the lipid concentration [23] and charge [33], have significant impact on the resulting biophysical properties and characteristic distributions of the GUVs.

Correlating relationships between solution composition and GUV architecture and distribution is foundational to establishing fundamental physicochemical parameters that drive membrane assembly in bulk systems and has been directly used as a proxy for understanding how biological membranes behave in cellular environments [5,6,7,9]. Recently, we reported the application of GUVs for studying membrane-disrupting behavior of amphiphilic small molecules in a cell-free system [34]. In this study, we further evaluated the membrane-disruptive properties of the antimetabolite carmofur and its lipid analogs using this assay. Carmofur, originally developed as a lipophilic, orally available prodrug of 5-fluorouracil, is approved in Japan for the treatment of colorectal cancer [35,36]. Previously, our laboratory has identified that certain analogs of carmofur consistently induced membrane rupture due to their amphiphilic structure. These findings suggest potential for further investigation into their use as surfactant-like agents [34].

Currently, GUVs are often analyzed through manual selection using image analysis software such as Fiji [37,38], or the automated methods are limited to GUVs with large sizes or high-resolution imaging methods such as confocal microscopy [39,40,41,42,43]. However, this process is both time-consuming and prone to subjective measurement errors that arise from manual image selection, and can be cost-, time-, and hardware-prohibitive for high-throughput screening on confocal fluorescence microscopes. Furthermore, characterization typically relies on extrapolation from a small subset of vesicles.

To address this, we created an automated method to quantify GUVs in images using image analysis routines based on a convolutional neural network (CNN) previously reported as Ultralytics’ unified “You Only Look Once” (YOLO) method of object detection [44] that obviates the need for manual data extraction from large datasets of multi-layered GUV images. While existing AI-guided methods are limited to analyzing images where the GUVs are sparsely distributed or require high-resolution confocal imaging [38,43,45], in this work we validate the novel implementation of the YOLOv11 AI-guided method for the analysis of large field view and densely packed GUV images that are collected with a high-throughput and an economical microscopy setup.

Furthermore, we first utilize these microscopy and AI-guided image analysis methods to aid us in the optimization of GUV preparation conditions, where we evaluate the quantitative impact of solution conditions and electrokinetically relevant lipid compositions on GUV sizes and yields. We then ultimately show the utility of the method in large-scale biophysical interrogations that compare the membrane rupture potential of two carmofur analogs, a dodecyl C12 urethane and octadecyl C18 urethane analog, against a known positive control, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of the GUV Lipid Solution

Our standard lipid solution was prepared by dissolving 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(Lissamine Rhodamine B Sulfonyl) in chloroform at a final concentration of 1 mg/mL with a molar ratio of 99.5:0.5 mol % DOPC: RhodaminePE. Alternative mixtures used in this work included 1-palmitoyl-2-(dipyrrometheneboron difluoride)undecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (TopFluor™ PC) at 0.5 mol %, and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) (DOPG) at varying molar percentages. All of the lipids and dyes were purchased at Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL, USA).

2.2. Preparation of the 96-Well Plate of GUVs

Each lipid solution was applied to a 9.5 mm cutout circle of tracing paper using a 10 µL Hamilton syringe and placed in a 48-well, tissue-culture Eppendorf clear plastic plate with 300 µL of a 100 mM sucrose solution for overnight incubation. GUVs were harvested using a 1000 µL pipette with 7 cycles of aspiration and expulsion. To prepare for imaging, 85 µL of 100 mM glucose was added to a Whatman 96-well glass bottom plate, along with 2 µL of the harvested GUVs. In between uses, the glass plate was rinsed in sequential order of water, isopropyl alcohol, and water.

2.3. Fluorescence Microscopy

All fluorescence images in this work were collected using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 Fluorescence Microscope and a Zeiss ebq 100 power (Zeiss; Oberkochen, Germany) supply along with a Sony Nex-6 digital camera (Sony Electronics; Tokyo, Japan). Images that were used for the training of the AI-guided code or for the large-scale GUV biophysical assays were taken using a Zeiss Fluar 5×/0.25 objective lens and a Rhodamine B filterset (Zeiss; Göttingen, Germany; 545 nm excitation and 566 nm emission).

2.4. AI Image Analysis

The training and validation dataset was prepared by splitting several 5× fluorescence microscopy images into 256 slices each and iterating through every 20th slice, upon which the bounding box position of each GUV was manually annotated. The annotated bounding box positions were then transcribed in YOLO’s normalized label format to text files corresponding to the image slices. The model was then trained on the written bounding box data files, starting with the YOLOv11 pretrained weights (from the YOLOv11 Github) and training over 100 epochs. Evaluation with the algorithm followed a similar procedure, where the image was read in grayscale and was split into 256 equal slices. Each individual slice was run through the trained model, returning the bounding box and class data per slice from which GUV statistics were assessed in MATLAB (version R2025a).

2.5. Analyzing GUV Growth Under Varying Conditions

In this experiment, we evaluated multiple parameters including sucrose-to-glucose concentration gradient and lipid composition to optimize GUV yield and lipid usage. To evaluate the effect of osmotic conditions, we tested three sucrose-to-glucose gradients including 0 mOsmol/L difference, −20 mOsmol/L difference, and +10 mOsmol/L. Lipid composition was varied by adjusting the molar ratios of DOPC, DOPG, and Rhodamine, while maintaining a total lipid concentration of 1 mg/mL. The tested compositions included 0 mol % DOPG, 20 mol % DOPG, and 40 mol % DOPG.

2.6. GUV Rupture Fluorescence Imaging Assay

GUVs were prepared with 15 µL of a 1 mg/mL DOPC solution. Carmofur was obtained from AK Scientific (Union City, CA, USA), and the dodecyl and octadecyl urethane analogs of carmofur were prepared as previously described [34,46]. 2 μL of the carmofur analogs, diluted to the appropriate concentration in DMSO, were added to the GUV samples. A negative control was prepared using 2.07% v/v DMSO, while a positive control of SDS, diluted to the appropriate concentration in water, was added at 2 μL. Following a 60 min incubation period, one representative 5× magnification image of the GUVs in each well was captured to assess membrane disruption. The resulting images acquired were processed through the previously described YOLOv11-based method for analysis of resulting GUV characteristics.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Development of an AI-Guided Image Detection Method for GUVs

3.1.1. High-Throughput Construction and Characterization of GUVs

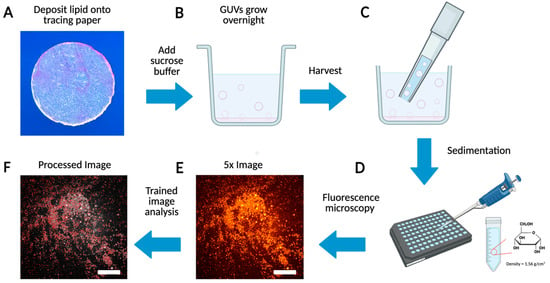

Among the various surface-assisted methods typically used to construct GUVs [47,48,49], we chose to utilize the PAPYRUS method (Paper-Abetted amPhiphile hYdRation in aqUeous Solutions) [50], due to the ease and cost-effectiveness with which commercial artist-grade tracing paper could be manipulated for multiplexed samples as well as the remarkably high yields of GUVs that were obtainable with our experimental conditions. Figure 1 shows the complete workflow for the construction and characterization of the GUVs we used for experiments in this work.

Figure 1.

Schematic of GUV preparation, imaging, and processing. (A) Deposit lipid solution onto a cutout circle of tracing paper. (B) Growth and budding of GUVs from the tracing paper in a sucrose solution. (C) Harvest the GUVs using a 1000 μL tip. (D) Sediment GUVs in glucose for 3 h. (E) Obtain a large field of view image of the GUVs using a fluorescent microscope. (F) Processed image using custom AI code.

Firstly, we coat a 9.5 mm diameter hole-punched area of a piece of tracing paper with 15 μL lipid and remove any residual solvent under vacuum (Figure 1A). The lipid-coated paper is placed face up into a single well of a 48-well plate where it is then hydrated to begin the GUV swelling process (Figure 1B). After growth overnight, the GUVs are harvested through mechanical shear created by pipetting up and down (Figure 1C) and are moved as an aliquot of the total solution into a single well of a 96-well plate (Figure 1D). The GUVs are allowed to settle for up to 3 h and are imaged on a fluorescence microscope (Figure 1E).

The microscope components used for the training and large-scale analysis in this work included a refurbished Zeiss Axiovert 200 fluorescence microscope, a Zeiss Fluar 5×/0.25 objective lens, a Zeiss ebq 100 power supply, and a Sony Nex-6 digital camera. Notably, with this setup a single shot covers a large 7.5 mm2 area at the bottom of the 96-well plate where GUVs with diameters of 5 µm and greater are in focus throughout the image. GUVs between 1 and 4 µm in diameter appear in the image as well, but their lamellarity, which can be visualized as a single ring, is less clear. However, using a 32× magnification objective lens, we find the smallest GUVs we obtain from our methods [50] correlate to the circular, 1-to-4 µm-in-diameter objects in the 5× images that also have mean fluorescence intensities between 50 and 100. Finally, the images are processed using our trained AI-guided image analysis method which can detect thousands of GUVs in a single image with typical runtimes of less than 10 s per image (Figure 1F).

3.1.2. Training and Validation of an AI-Guided Detection of GUVs

Due to the low magnification imaging enabled by the code, we can detect and measure the diameters of approximately 1000–7000 vesicles per image, depending on the yield and quality of the sample. Additionally, when conducting a GUV assay, we have previously been interested in demonstrating the surfactant-like behavior of several lipidated drug compounds. An experiment such as this may require conditions at multiple concentrations in triplicate or quadruplicate and may require data on parameters such as the number of GUVs present (perhaps total counts or only counts of GUVs with particular sizes), and the number of GUVs present at several time points before and after the addition of a drug. Thus, the amount of data can scale quite quickly with an entire 96-well plate potentially containing more than a million GUVs to be analyzed for a single experiment.

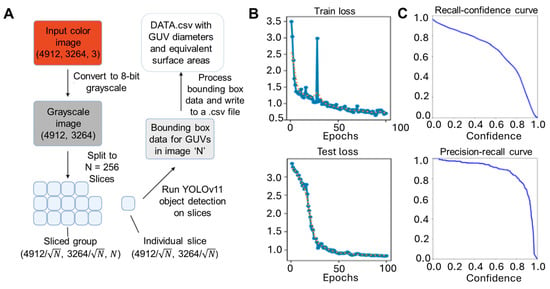

To open an avenue that allows for these sorts of large-scale biophysical interrogations, we tested several different automated image analysis methods. For this, we wanted to especially compare more traditional analytical or mathematical algorithms with newer statistical, AI/ML approaches. Given then that human observers have a natural aptitude at identifying these objects and innately use statistical processing, we speculated that the former may have a substantial improvement on image parsing. For this purpose, we trained the image-centric convolutional neural network algorithm YOLOv11 across image sets spanning different GUV densities and spatial distributions to ensure a more robust identification (Figure 2A). Despite being trained on a relatively small dataset of 135 training frames, 138 validation frames, 651 training vesicles, and 707 validation vesicles, the YOLOv11 model was able to achieve effective object detection for GUVs, as evidenced by the steadily decreasing training and test loss (Figure 2B). To assess detection performance, we analyzed the model’s recall and precision across varying confidence thresholds (Figure 2C). The resulting precision-recall (PR) curve (Figure 2C) exhibited high classification accuracy, with a PR area-under-curve (AUC) value of 0.873. Similarly, a recall-confidence curve area of 0.686 plotted for the resulting model performance suggests reasonable tradeoff of positive recall values with increasing confidence level stringency.

Figure 2.

YOLO training methodology and optimization for AI GUV image analysis. (A) Overall workflow of training and test procedure on GUV microscopy datasets. Sample performance metrics depict the (B) convergence of the training and test losses (orange dots are simple moving average of every 3 blue dots) and (C) a sharp knee on the recall-confidence and precision-recall curves.

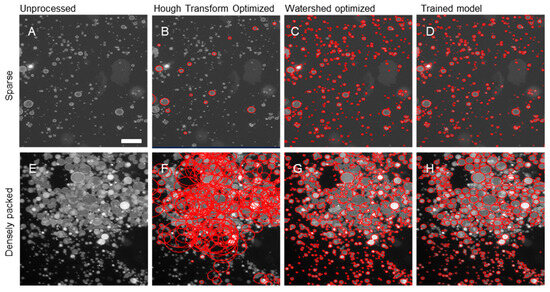

3.1.3. Survey of Various Automated Image Analysis Methods

We then compared the performance of the trained YOLO model to more analytical approaches for object recognition, namely Hough Transform and watershed segmentation algorithms as representative analytical approaches (Figure 3A–H). We observed that in the large field of view and, in particular, the images with crowded GUVs, the analytical detection methods either oversegment or undersegment the objects and fail to characterize the GUVs with admissible accuracy. Yet with relatively minimal training of an AI-model, we observe an impressive improvement in segmentation of these extremely challenging and dense images.

Figure 3.

Comparison of segmentation algorithms on sparse and densely packed fluorescence microscopy images (red circles indicate regions selected as GUVs by the code). (A) Unprocessed image of sparse GUV distribution. Corresponding (B) optimized Hough transform circles, (C) optimized watershed segmentation outlines, (D) trained AI (YOLOv11) model bounding ellipses. (E) Unprocessed image of dense GUV distribution. Corresponding (F) optimized Hough transform circles, (G) optimized watershed segmentation outlines, (H) trained AI (YOLOv11) model bounding ellipses. Scale bars are 25 μm.

Additionally, in Table 1 we show microscopy conditions, including the objective lens, microscope, and detector, used in other existing studies that demonstrate an automated image analysis program for GUV quantification. Notably, in all of the other existing studies either a confocal microscope or a microscope with a 100× objective lens attachment is used to collect the GUV images. In the rightmost two columns of Table 1, we show the results of run time and GUV detection accuracy on the implementation of the various image analysis methods on our typical images. To determine accuracy, we manually counted the number of GUVs in 10 of our 5× images that contained between 4000 and 6000 GUVs per image. We then ran the optimized code for each method to determine the automated GUV counts, and we determined the accuracy by dividing the correct predictions (correctly classified GUVs by automation) by the total predictions (total GUVs by manual counting). We find a substantial improvement in the object recognition accuracy with our YOLOv11 method in comparison to the alternatives.

Table 1.

Comparison of the described YOLOv11-based GUV detection method to other previously reported automated GUV detection algorithms demonstrates that YOLOv11 achieves higher accuracy on data generated on a non-confocal fluorescence microscope setup. An analysis of variance test (ANOVA) confirms the p-values are statistically significant between the YOLOv11, DisGUVery, and watershed method: p = 1.262 × 10−5, YOLOv11; DisGUVery, p = 7.583 × 10−4; and YOLOv11 and watershed, p = 1.009 × 10−5.

3.2. AI-Guided Optimization and Analysis of GUVs

3.2.1. Optimization of Conditions to Prepare Physiological GUVs

To construct GUVs that better mimic typical physiological conditions of the cell plasma membrane, we investigated our capabilities to produce GUVs with a slightly higher membrane tension and a slightly negative charge, and employed the use of our large-scale GUV production and automated image analysis routine as a rapid development method.

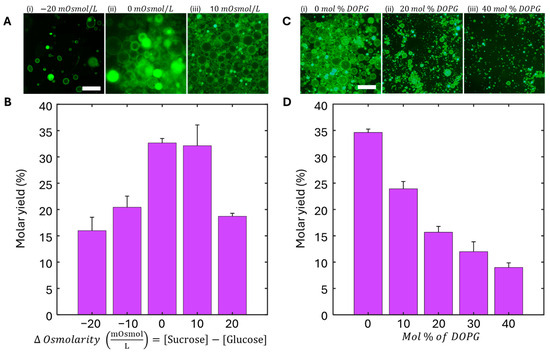

Figure 4A shows representative images of the effect of osmotic gradients on GUV morphology and yields. When the GUV is in a hypertonic state with a lower concentration of an osmolyte inside compared to the outside environment, we expect the water to diffuse across the lipid bilayer into the external solution, resulting in irregular and deformed GUVs, which we categorize as “floppy” GUVs. Consequently, if the GUV is in a hypotonic state with a higher concentration of osmolyte inside compared to the outside environment, we expect that GUVs begin to swell, become perfectly round, and potentially burst. Interestingly, for the yields obtained using the AI detection method going from the most hypertonic to most hypotonic at −20, −10, 0, 10, and 20 mOsmol/L, the GUV molar yields range from 15.9 ± 2.5, 32.1 ± 3.9, 32.7 ± 0.9, 20.4 ± 2.1, and 18.7 ± 0.6%, respectively (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Effects of osmolarity gradient and lipid composition (DOPG percent) on GUV formation yield. (A) 32× fluorescent microscopy images of GUV yield under various osmolarity gradients (ΔOsmolarity = [sucrose] − [glucose]). (i) −20 mOsmol/L (ii) 0 mOsmol/L (iii) 10 mOsmol/L. (B) Normalized GUV yields as a function of ΔOsmolarity, showing the greatest yield around 0 to +10 mOsmol/L. (C) 32× fluorescent microscopy images of GUV prepared under varying mole fractions of DOPG. (i) 0 mol % DOPG (ii) 20 mol % DOPG (iii) 40 mol % DOPG. (D) Normalized GUV yields as a function of mole fraction of DOPG, representing a negative decrease in GUV yield as DOPG mole fraction increases. Scale bars for (A,C) are 25 μm.

To evaluate the effect of lipid composition on GUV yield, we also tested mixtures containing varying ratios of the neutral phospholipid DOPC and the negatively charged lipid DOPG (Figure 4C,D). As the proportion of DOPG increased, the GUV yield decreased with 0, 10, 20, 30, and 40 mol % DOPC resulting in 34.6 ± 1.0, 23.9 ± 2.5, 15.7 ± 1.3, 12.0 ± 2.2, and 8.9 ± 0.8% molar yields, respectively. Considering the results from both the osmolarity molar yield experiment as well as the anionic molar yield experiment, we determined that the conditions that would have high enough yields of GUVs to use in an assay format could range between osmotic gradients with −10 mOsmol/L to 20 mOsmol/L as well as anionic dopants between 0 and 20 mol %. The standard condition we employ to prepare physiological GUVs for the experiments in this work was with an osmotic gradient of +10 mOsmol/L and a DOPG mole fraction of 10%.

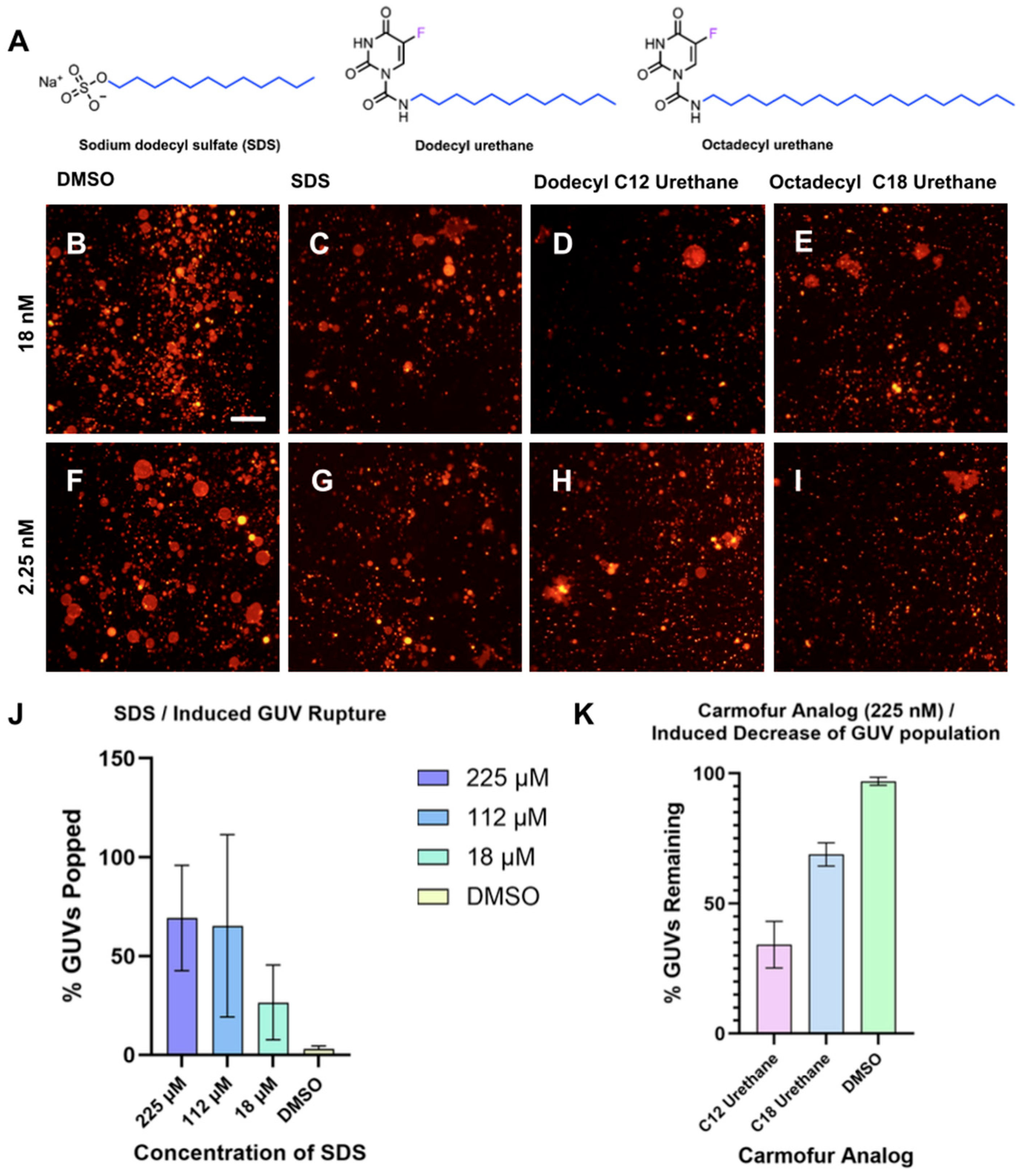

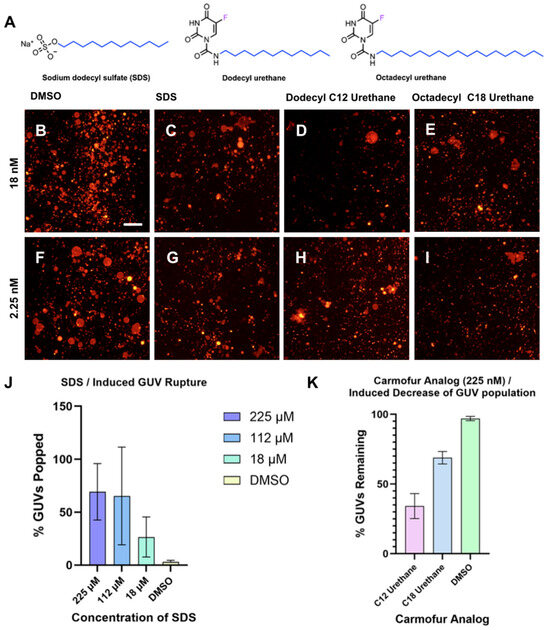

3.2.2. High-Throughput GUV Rupture Assay

Previously, we identified two analogs of the lipophilic antineoplastic drug carmofur bearing C12 and C18 lipid tails as having potent membrane-rupture activities in GUVs [34] (Figure 5A). We designed a cell-free membrane disruption assay to evaluate and quantify the surfactant-like behavior of the octadecyl and dodecyl urethane analogs of carmofur by measuring the number of intact GUVs with diameters greater than 10 µm before and after compound treatment. (Figure 5B–I).

Figure 5.

Effect of compound and concentration on GUV rupture. (A) Depicted are structures of carmofur analog test compounds dodecyl urethane and octadecyl urethane as well as the positive control compound SDS. Representative images of GUVs 60 min after addition of (B) 2.07% v/v DMSO, (C) 18 nM SDS, (D) 18 nΜ dodecyl urethane, (E) 18 nM octadecyl urethane, (F) 2.07% v/v DMSO, (G) 2.25 nM SDS, (H) 2.25 nM dodecyl urethane, (I) 2.25 nM octadecyl urethane. (J) Quantified percentage of GUV popped when GUVs are treated with a series of dilutions of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) using the YOLOv11 CNN method. (K) Normalized, quantified percentage of identified GUVs remaining when GUVs are treated with 225 nM of dodecyl urethane and octadecyl urethane analogs of carmofur.

While this was previously performed in our laboratory using manual counting of GUVs [34], we found with our AI-guided method that quantification of GUVs before and after treatment with various concentrations of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) could be completed in a fraction of the time required when compared to the manual method of counting the GUVs (Figure 5J). For rupture quantification of compounds with surfactant-like properties, each condition typically involved approximately 1500 vesicles prior to treatment and around 600 vesicles remaining afterward. Exact counts varied depending on the specific compound and concentration. For analysis of the effect of amphiphilic carmofur analogs on GUV populations, we utilized the median concentration (225 nM) of two of the carmofur analogs we previously reported—dodecyl urethane and octadecyl urethane—along with SDS, included as a positive control for surfactant-induced rupture (Figure 5A). Consistent with our previous report, both test compounds substantially reduced the number of large GUVs detected by the algorithm (Figure 5K). DMSO was further applied as a negative control with no measurable effect. While the YOLOv11-based algorithm employed in this assay was only trained on GUV-containing images without a specific class for destabilized GUV patches whose conformational state is similar to unaffected GUVs, we anticipate training the model on specifically identifying GUV patches may improve its identification ability to quantify GUVs in the presence of exceedingly large populations of destabilized GUV patches induced by high concentrations of carmofur.

4. Conclusions

Giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) are incredibly versatile model systems for the study of fundamental and applied biophysical features of lipid membranes. Accordingly, the accurate characterization of the size and population distributions of GUVs by image analysis is critical to precise quantification of the role of small molecules, such as sugars or surfactants, on GUV size, yield, and stability. Existing methods of automated GUV quantification by direct image analysis are generally dependent on high resolution confocal microscopy, thereby drawing limited applicability to laboratories without access to confocal imaging.

Here, we presented the use of a YOLOv11-based AI automated image analysis, which we found enables rapid and accurate quantification of GUV populations, allowing calculation of vesicle count, size distribution, membrane shape, and overall surface area. Importantly, we demonstrate that this platform is not dependent on image datasets acquired from confocal microscopy systems, access to which can be prohibitive in many R&D settings. Particular to lower-resolution fluorescence microscopy data, we demonstrate that the described YOLOv11 method exhibits comparable or superior accuracy in GUV detection using standard fluorescence microscopy data, in comparison to existing algorithms developed for this purpose. Further, we demonstrate that a trained AI-guided image detection algorithm retains robust GUV quantification in both sparse and densely populated GUV populations. Analysis of the recall-confidence curve shows a steep drop in recall as the confidence threshold increases, suggesting the model could further improve on detection of less-certain objects by increasing the size and diversity of the training data, which constrains the model’s ability to generalize. With a larger and more representative dataset, we expect the model to achieve higher recall across a broader confidence range, thereby improving overall detection robustness.

To demonstrate the applicability of the YOLOv11-based algorithm for high-throughput process optimization in GUV preparation, we performed a systematic screen of the impact of glucose- and sucrose-induced osmotic gradients and lipid compositions on GUV yield and integrity and deployed our YOLOv11-based platform to obtain precise yields and size distributions across dozens of samples. From this, we found that a mild osmotic gradient (<10 mOsmol/L difference) and the exclusion of DOPG (0 mol fraction) resulted in the highest yield of non-floppy GUVs.

Additionally, to further demonstrate the platform’s utility in drug screening, we used a GUV popping assay to assess membrane-disruptive behavior of sodium dodecyl sulfate and similar surfactants, including two amphiphilic lipid-based analogs of the investigational antineoplastic agent carmofur, bearing C12 and C18 lipid tails, which our laboratory has previously studied for potent membrane disruption activities. The YOLOv11 algorithm retained robust performance in identifying decreases in GUV population upon treatment with different surfactants.

Collectively, we demonstrate that an AI image recognition algorithm is an effective platform for accurate and rapid characterization of GUV populations that is easily scalable for diverse high-throughput screening applications, and which can be deployed in labs with a standard fluorescence microscopy setup, and which do not require images acquired on confocal microscopy. We further demonstrate the utility of this platform in the high-throughput optimization of glucose and sucrose additives in GUV formation dynamics and further employ this methodology to rapidly quantify GUV-rupturing activities of membrane surfactants. More broadly, these results demonstrate that YOLOv11 can be deployed for high throughput image parsing of GUV populations in comparable or superior accuracy compared to existing automated GUV detection algorithms. We envision that the platform described here is directly applicable to a diverse array of applications involving the manipulation of large membrane dynamics.

Author Contributions

D.D., L.C., A.Y. and J.P. performed microscopy experiments and developed the methodology for preparation of GUVs. J.P. and J.G. developed the scripts to perform GUV analysis. J.G., T.J.S., T.G., A.G. and J.P. performed analysis on the dataset using the YOLOv11-based algorithm. T.G. and E.N. prepared synthetic analogs of carmofur. All authors wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was jointly funded by reThink64 Bionetworks PBC and ASDRP.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Akira Yamamoto, Tapash Jay Sarkar and Joseph Pazzi are employed by reThink64 Bionetworks PBC and are co-inventors on a pro-visional patent filed in connection to a portion of the work de-scribed here. The authors declare that this study received funding from reThink64 Bionetworks PBC. The funder had the following involvement with the study: Methods described, including the data used to train the AI model and the corresponding scripts used to run the AI model and per-form subsequent analysis.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript

| GUV | Giant unilamellar vesicles |

| YOLO | “You Only Look Once” method |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| SDS | Sodium dodecyl sulfate |

References

- Nair, K.S.; Bajaj, H. Advances in Giant Unilamellar Vesicle Preparation Techniques and Applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 318, 102935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matosevic, S. Synthesizing Artificial Cells from Giant Unilamellar Vesicles: State-of-the Art in the Development of Microfluidic Technology. BioEssays 2012, 34, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pazzi, J.; Subramaniam, A.B. Dynamics of Giant Vesicle Assembly from Thin Lipid Films. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 661, 1033–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimova, R. Giant Vesicles and Their Use in Assays for Assessing Membrane Phase State, Curvature, Mechanics, and Electrical Properties. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2019, 48, 93–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wu, Z.; Gao, Z.; Wan, M.; Zhou, M.; Mao, C.; Shen, J. Artificial Cells: Past, Present and Future. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 15705–15733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.; Lu, Y. Compartmentalizing Cell-Free Systems: Toward Creating Life-Like Artificial Cells and Beyond. ACS Synth. Biol. 2020, 9, 2881–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddingh’, B.C.; van Hest, J.C.M. Artificial Cells: Synthetic Compartments with Life-like Functionality and Adaptivity. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y.; Xie, R.; Xiong, J.; Liang, Q. Microfluidics for Biosynthesizing: From Droplets and Vesicles to Artificial Cells. Small 2020, 16, 1903940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.H.; Zeng, J. Application of Polymersomes in Membrane Protein Study and Drug Discovery: Progress, Strategies, and Perspectives. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2023, 8, e10350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigenson, G.W. Phase Behavior of Lipid Mixtures. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006, 2, 560–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigenson, G.W. Phase Diagrams and Lipid Domains in Multicomponent Lipid Bilayer Mixtures. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2009, 1788, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, S.; Kuldinow, D.; Haataja, M.P.; Košmrlj, A. Phase Behavior and Morphology of Multicomponent Liquid Mixtures. Soft Matter 2019, 15, 1297–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagatolli, L.; Sunil Kumar, P.B. Phase Behavior of Multicomponent Membranes: Experimental and Computational Techniques. Soft Matter 2009, 5, 3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahya, N.; Pécheur, E.-I.; de Boeij, W.P.; Wiersma, D.A.; Hoekstra, D. Reconstitution of Membrane Proteins into Giant Unilamellar Vesicles via Peptide-Induced Fusion. Biophys. J. 2001, 81, 1464–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girard, P.; Pécréaux, J.; Lenoir, G.; Falson, P.; Rigaud, J.-L.; Bassereau, P. A New Method for the Reconstitution of Membrane Proteins into Giant Unilamellar Vesicles. Biophys. J. 2004, 87, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balleza, D. Mechanical Properties of Lipid Bilayers and Regulation of Mechanosensitive Function. Channels 2012, 6, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mangala Prasad, V.; Blijleven, J.S.; Smit, J.M.; Lee, K.K. Visualization of Conformational Changes and Membrane Remodeling Leading to Genome Delivery by Viral Class-II Fusion Machinery. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shendrik, P.; Golani, G.; Dharan, R.; Schwarz, U.S.; Sorkin, R. Membrane Tension Inhibits Lipid Mixing by Increasing the Hemifusion Stalk Energy. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 18942–18951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowska, A.; Heinz, L.P.; Grubmüller, H.; Jahn, R. Tight Docking of Membranes Before Fusion Represents a Metastable State with Unique Properties. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, P.; Park, J.-B.; Shin, Y.-K.; Kweon, D.-H. Visualization of SNARE-Mediated Hemifusion Between Giant Unilamellar Vesicles Arrested by Myricetin. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, A.; Hu, S.; Ebrahim, S.; Kachar, B. Hemifusomes and Interacting Proteolipid Nanodroplets Mediate Multi-Vesicular Body Formation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pazzi, J.E. A Comprehensive Characterization of Surface-Assembled Populations of Giant Liposomes Using Novel Confocal Microscopy-Based Methods. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Merced, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, A.; Subramaniam, A.B. Ultrahigh Yields of Giant Vesicles Obtained Through Mesophase Evolution and Breakup. Soft Matter 2024, 20, 9547–9561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messager, L.; Gaitzsch, J.; Chierico, L.; Battaglia, G. Novel Aspects of Encapsulation and Delivery Using Polymersomes. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2014, 18, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bangham, A.D.; Standish, M.M.; Watkins, J.C. Diffusion of Univalent Ions Across the Lamellae of Swollen Phospholipids. J. Mol. Biol. 1965, 13, 238-IN27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shohda, K.; Takahashi, K.; Suyama, A. A Method of Gentle Hydration to Prepare Oil-Free Giant Unilamellar Vesicles That Can Confine Enzymatic Reactions. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2015, 3, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngassam, V.N.; Su, W.-C.; Gettel, D.L.; Deng, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang-Tomic, N.; Sharma, V.P.; Purushothaman, S.; Parikh, A.N. Recurrent Dynamics of Rupture Transitions of Giant Lipid Vesicles at Solid Surfaces. Biophys. J. 2021, 120, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.; Girish, V.; Subramaniam, A.B. Osmotic Pressure Enables High-Yield Assembly of Giant Vesicles in Solutions of Physiological Ionic Strengths. Langmuir 2023, 39, 5579–5590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, H.; Spindler, S.; Bonakdar, N.; Wang, C.; Sandoghdar, V. Production of Isolated Giant Unilamellar Vesicles Under High Salt Concentrations. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajii, K.; Shimomura, A.; Higashide, M.T.; Oki, M.; Tsuji, G. Effects of Sugars on Giant Unilamellar Vesicle Preparation, Fusion, PCR in Liposomes, and Pore Formation. Langmuir 2022, 38, 8871–8880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oglęcka, K.; Rangamani, P.; Liedberg, B.; Kraut, R.S.; Parikh, A.N. Oscillatory Phase Separation in Giant Lipid Vesicles Induced by Transmembrane Osmotic Differentials. Elife 2014, 3, e03695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.; Karal, M.A.S.; Akter, S.; Ahmed, M.; Ahamed, M.K.; Ahammed, S. Influence of Sugar Concentration on the Vesicle Compactness, Deformation and Membrane Poration Induced by Anionic Nanoparticles. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinkühler, J.; De Tillieux, P.; Knorr, R.L.; Lipowsky, R.; Dimova, R. Charged Giant Unilamellar Vesicles Prepared by Electroformation Exhibit Nanotubes and Transbilayer Lipid Asymmetry. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, T.; Lu, A.; Wang, X.; Brahan, N.; Xu, L.; Zhang, L.; Su, K.; Seow, K.; Vu, J.; Luk, C.; et al. Synthesis and Evaluation of Carmofur Analogs as Antiproliferative Agents, Inhibitors to the Main Protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2, and Membrane Rupture-Inducing Agents. Discov. Chem. 2025, 2, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, M.; Takagami, S.; Kim, R.; Kirihara, Y.; Saeki, T.; Jinushi, K.; Niimoto, M.; Hattori, T. Inhibition of Thymidylate Synthetase and Antiproliferative Effect by 1-Hexylcarbamoyl-5-Fluorouracil. Gan Kagaku Ryoho Cancer Chemother. 1988, 15, 3109–3113. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.M.; Mirza, S.P. Versatile Use of Carmofur: A Comprehensive Review of Its Chemistry and Pharmacology. Drug Dev. Res. 2022, 83, 1505–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sych, T.; Schubert, T.; Vauchelles, R.; Madl, J.; Omidvar, R.; Thuenauer, R.; Richert, L.; Mély, Y.; Römer, W. GUV-AP: Multifunctional FIJI-Based Tool for Quantitative Image Analysis of Giant Unilamellar Vesicles. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 2340–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.-H.; Passaro, S.; Ozturk, S.; Ureña, J.; Wang, W. Intelligent Fluorescence Image Analysis of Giant Unilamellar Vesicles Using Convolutional Neural Network. BMC Bioinform. 2022, 23, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husen, P.; Arriaga, L.R.; Monroy, F.; Ipsen, J.H.; Bagatolli, L.A. Morphometric Image Analysis of Giant Vesicles: A New Tool for Quantitative Thermodynamics Studies of Phase Separation in Lipid Membranes. Biophys. J. 2012, 103, 2304–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, E.; Bleicken, S.; Subburaj, Y.; García-Sáez, A.J. Automated Analysis of Giant Unilamellar Vesicles Using Circular Hough Transformation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1747–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leomil, F.S.C.; Zoccoler, M.; Dimova, R.; Riske, K.A. PoET: Automated Approach for Measuring Pore Edge Tension in Giant Unilamellar Vesicles. Bioinform. Adv. 2021, 1, vbab037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Buren, L.; Koenderink, G.H.; Martinez-Torres, C. DisGUVery: A Versatile Open-Source Software for High-Throughput Image Analysis of Giant Unilamellar Vesicles. ACS Synth. Biol. 2023, 12, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Dreher, Y.; Niessner, J.; Fink, A.; Göpfrich, K. GeoV: An Open-Source Software Package for Quantitative Image Analysis of 3D Vesicle Morphologies. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2023, 5, 2300170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Vu, J.; Luk, C.; Njoo, E. Benchtop 19F Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Enabled Kinetic Studies and Optimization of the Synthesis of Carmofur. Can. J. Chem. 2023, 101, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, M.I.; Dimitrov, D.S. Liposome Electroformation. Faraday Discuss. Chem. Soc. 1986, 81, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, A.; Tsai, F.-C.; Koenderink, G.H.; Schmidt, T.F.; Itri, R.; Meier, W.; Schmatko, T.; Schröder, A.; Marques, C. Gel-Assisted Formation of Giant Unilamellar Vesicles. Biophys. J. 2013, 105, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, J.P.; Dowben, R.M. Formation and Properties of Thin-Walled Phospholipid Vesicles. J. Cell Physiol. 1969, 73, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazzi, J.; Subramaniam, A.B. Nanoscale Curvature Promotes High Yield Spontaneous Formation of Cell-Mimetic Giant Vesicles on Nanocellulose Paper. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 56549–56561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).