Abstract

This study investigates the fatigue strength of a motor hanger used in high-speed electric multiple units (EMUs). Finite element analysis and field measurements revealed that reduced weld penetration significantly increases stresses in welded regions. Line tests demonstrated that a 100 Hz torque ripple induces elastic vibration of the hanger, serving as the primary driver of stress propagation, with stress and acceleration levels increasing proportionally with the torque ripple amplitude. This 100 Hz excitation lies close to the hanger’s constrained modal frequency of about 109 Hz, creating a near-resonance condition that amplifies dynamic deformation at the welded joints and accelerates fatigue crack initiation. Hangers with lower in situ modal frequencies exhibited higher equivalent stresses. Joint dynamic simulation further showed that increasing motor mass reduces the longitudinal acceleration of the hanger, while enhancing the radial stiffness of rubber nodes markedly decreases both longitudinal and vertical vibration accelerations as well as stress responses. Based on these insights, a structural improvement scheme was developed. Strength analysis and on-track tests confirmed substantial reductions in overall and weld stresses after modification. Fatigue bench tests indicated that the critical welds of the improved hanger achieved a service life of 15 million km, more than twice that of the original structure (7.08 million km), thereby satisfying operational safety requirements.

1. Introduction

The High-speed railway technology in China has advanced rapidly in recent years, with total operating mileage ranking first in the world and several train types reaching 350 km/h. The motor hanger, as a critical component suspending the traction motor of a high-speed EMU, has fatigue strength directly related to operational safety. Therefore, an in-depth investigation of its fatigue performance is of great importance. The motor hanger studied in this work belongs to an EMU designed for operation above 300 km/h [1]. It connects to the bogie frame via elastic rods [2], with two motors mounted at both ends. However, field inspections have revealed the initiation of high stress in service well before the designed lifetime, posing significant risks.

1.1. Fatigue Behaviour of EMU Structural Components

Fatigue failures account for approximately 80% of mechanical part failures [3], often occurring without obvious deformation. With the increase in train speeds, fatigue research on critical components has become increasingly important. Seong-In Moon et al. [4] evaluated bracket fatigue life under random loads; other studies [5,6] analyzed the compliance of gearboxes and bogie frames with strength requirements. He et al. [7] proposed an S–N curve-based method for predicting fan blade life, confirming that reducing stress concentration can extend service life. Xi et al. [8] found that titanium alloy frames achieved twice the fatigue life of carbon steel ones. Huang [9] verified wheelset strength and analyzed the effect of wheel flats. These works highlight the widespread and growing attention to fatigue strength of mechanical structures.

1.2. Torque Ripple and Harmonic Excitation Effects

Scholars at home and abroad have also focused on the impact of harmonic torque on mechanical structures. Early studies, such as those by Japanese researchers in 1994, explored suppression of rectifier/inverter pulsations [10]. Jahns and Soong [11] argued that structural improvements should be prioritized over purely control-based techniques for eliminating harmonic torque. While LC resonant circuits can be used in intermediate DC links, this approach increases cost, weight, and maintenance demands, so high-speed trains commonly adopt software suppression methods. Xu et al. [12] found that harmonic torque reduces ride comfort and induces elastic resonance. Huang et al. [13] reported that it increases additional losses and shortens insulation life. Liu and Li [14] emphasized reducing torque ripple components and introducing “shield frequencies” to avoid resonance points. Collectively, these findings confirm that torque ripple significantly affects fatigue life and must be accounted for in structural analysis.

1.3. Integrated Modelling Approaches and Research Gap

Multibody dynamics can be divided into rigid-body and flexible-body systems [15]. Recent studies in related engineering fields further demonstrate the effectiveness of the methodologies adopted in this work. Kamat et al. [16] applied finite-element–based topology optimization and fatigue prediction to fluid-film bearing components, proving that integrated optimization–simulation methods can significantly extend service life. Venturini et al. [17] developed a tyre-rim digital twin combining biaxial loading tests with numerical simulation, illustrating how co-simulation approaches can accurately reproduce multi-axis dynamic behaviour. Wei et al. [18] carried out structural optimization and fatigue assessment of agricultural machinery frames using combined FEA and bench testing. These examples confirm that FEA, fatigue bench verification, and system-level co-simulation have become widely adopted tools for structural optimization in the transport and machinery sectors, supporting their use in EMU motor hanger analysis.

Since purely rigid models or small-deformation assumptions deviate significantly from reality, rigid–flexible coupled multibody dynamics has been developed. Chen et al. [19,20] established gear transmission models considering time-varying stiffness and crack effects. Claus et al. [21] analyzed stress and fatigue in bogie frames excited by track irregularities. Baeza et al. [22] examined high-frequency railway vehicle–track dynamics. Current studies mainly treat bogies, wheelsets, and car bodies flexibly. To accurately analyze the vibration of key subcomponents such as motor hangers, this study treats the hanger and suspension rods as flexible bodies, establishing a coupled vehicle dynamics model for simulation under torque ripple excitation.

To handle large amounts of measured current and voltage data while avoiding efficiency issues in Simpack, Matlab/Simulink was used to preprocess measured torque, which was then input into the dynamics model through co-simulation. This approach is supported by existing studies: Sonia et al. [23], based on Lagrange–Park theory and MATLAB (Simulink R2022b), validated electromechanical coupling models and showed that motor harmonics can induce mechanical vibration failures; Chen and Deng [24] developed a co-simulation interface linking Simpack vehicle dynamics with direct torque control models in Matlab/Simulink, capturing both mechanical and electrical behaviours of EMUs. These mature applications support the use of co-simulation in the present study.

This work investigates a domestic high-speed EMU motor hanger, using measured modal data, in-service acceleration and stress results as a foundation. The study integrates finite element simulations, field tests, co-simulation, structural redesign, and bench fatigue verification to identify the causes of high stress, quantify responses to torque ripple, and predict fatigue life. Although previous studies have examined harmonic torque, bogie vibration and fatigue of EMU components, no work has clarified the coupled mechanism between inverter-induced 100 Hz torque ripple and the in-service modal characteristics of the motor hanger. Existing research also lacks an integrated approach combining FE analysis, field measurements, rigid–flexible co-simulation and weld level fatigue testing. This study addresses these gaps by establishing the link between 100 Hz excitation, resonance-driven stress amplification and weld fatigue failure.

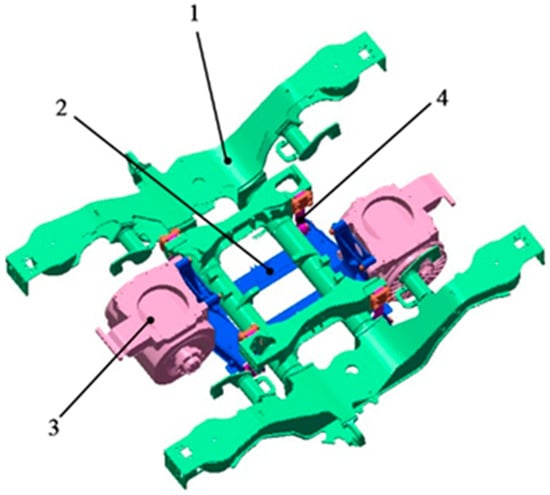

2. Finite Element Analysis of Motor Hanger

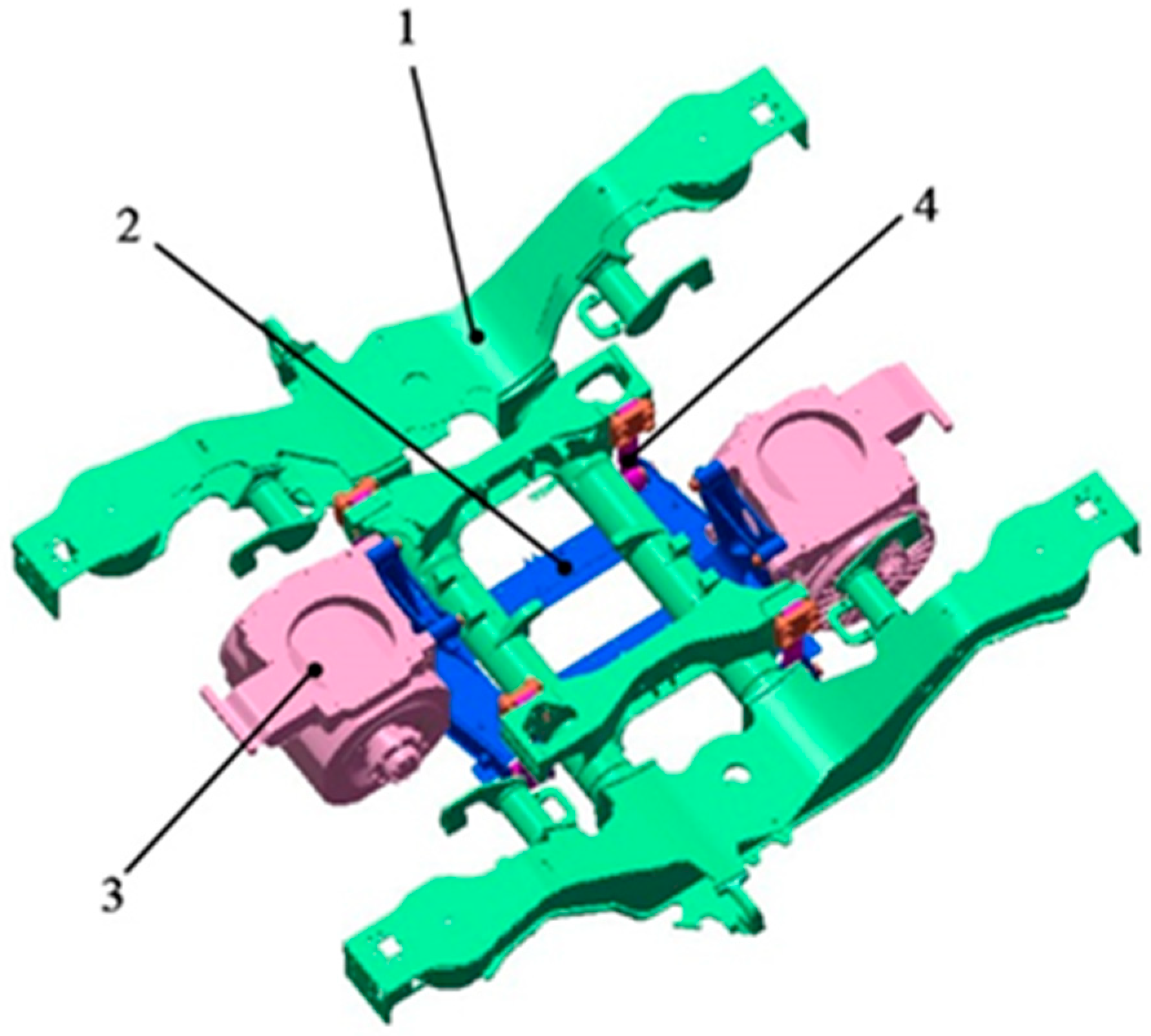

The motor hanger investigated in this study is a critical component used to suspend traction motors in high-speed EMUs. It is supported on the bogie frame by four elastic suspension rods, each equipped with a rubber bushing at the eyelet end. Two traction motors are mounted at both ends of the hanger using four M24 bolts each. The overall installation structure of the bogie frame, motor hanger, and traction motors is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Motor hanger installation structure diagram (1. Bogie frame; 2. Motor hanger; 3. Traction motor; 4. Elastic suspension rod).

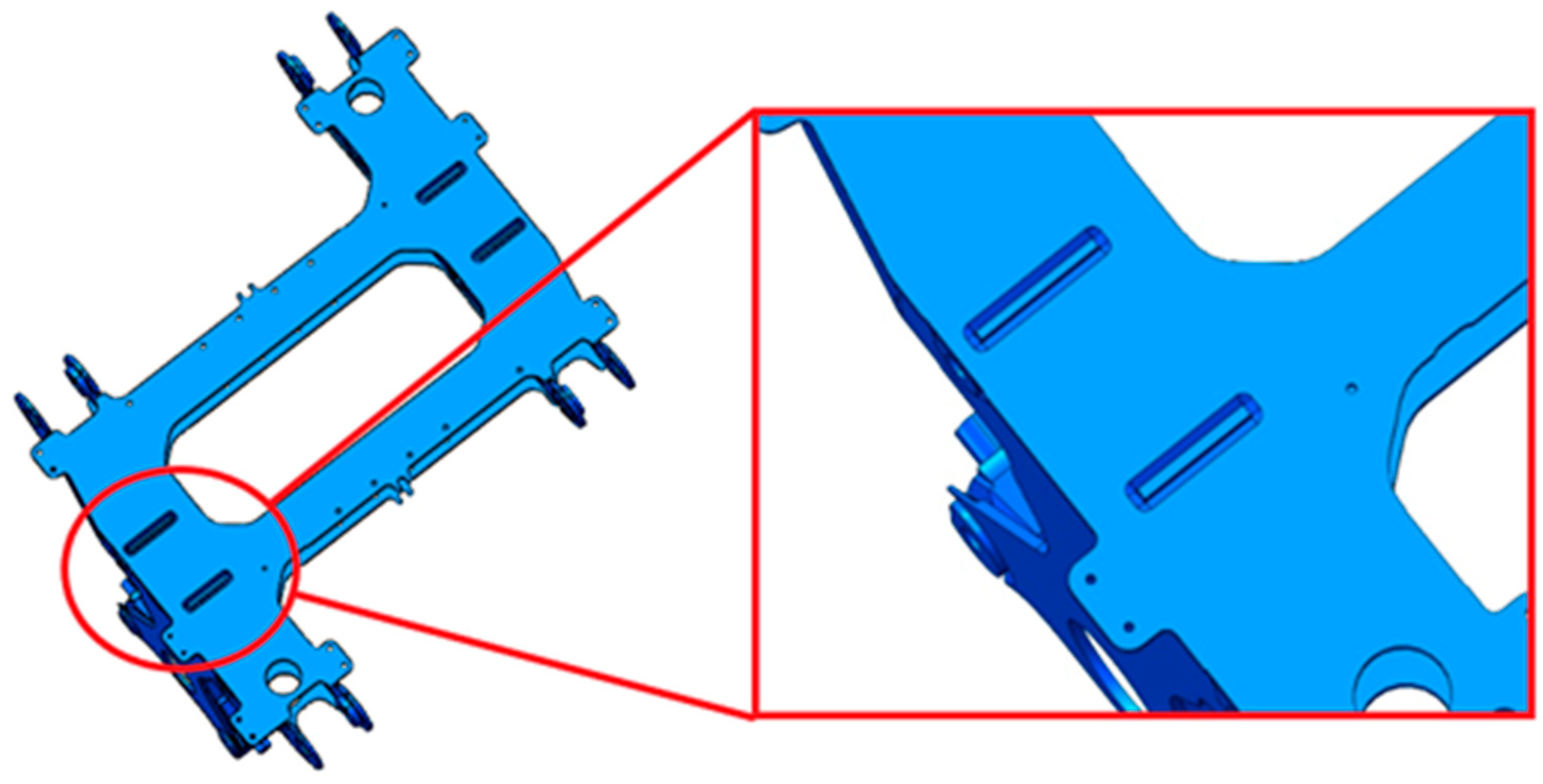

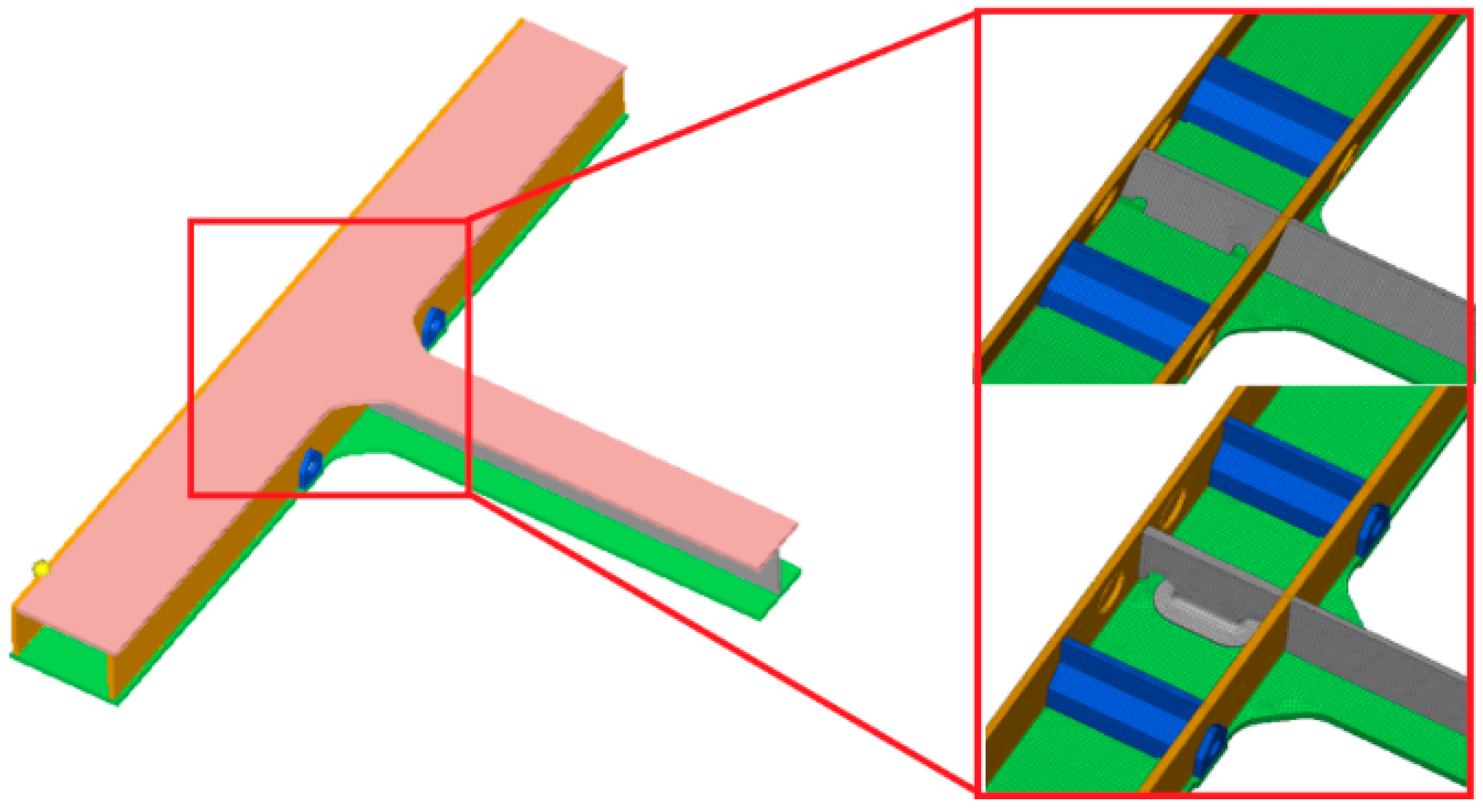

The motor hanger is a welded structural component, consisting of an upper cover plate, a lower cover plate, internal webs, inner and outer side plates, triangular stiffeners, and motor suspension mounts. The internal web passes through the lower cover plate and is welded to its underside. The groove depth at the lower cover plate weld joint is 6 mm, which is ground smooth after welding. The overall structure of the motor hanger and the weld groove configuration are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Overall structure of motor hanger and weld groove design.

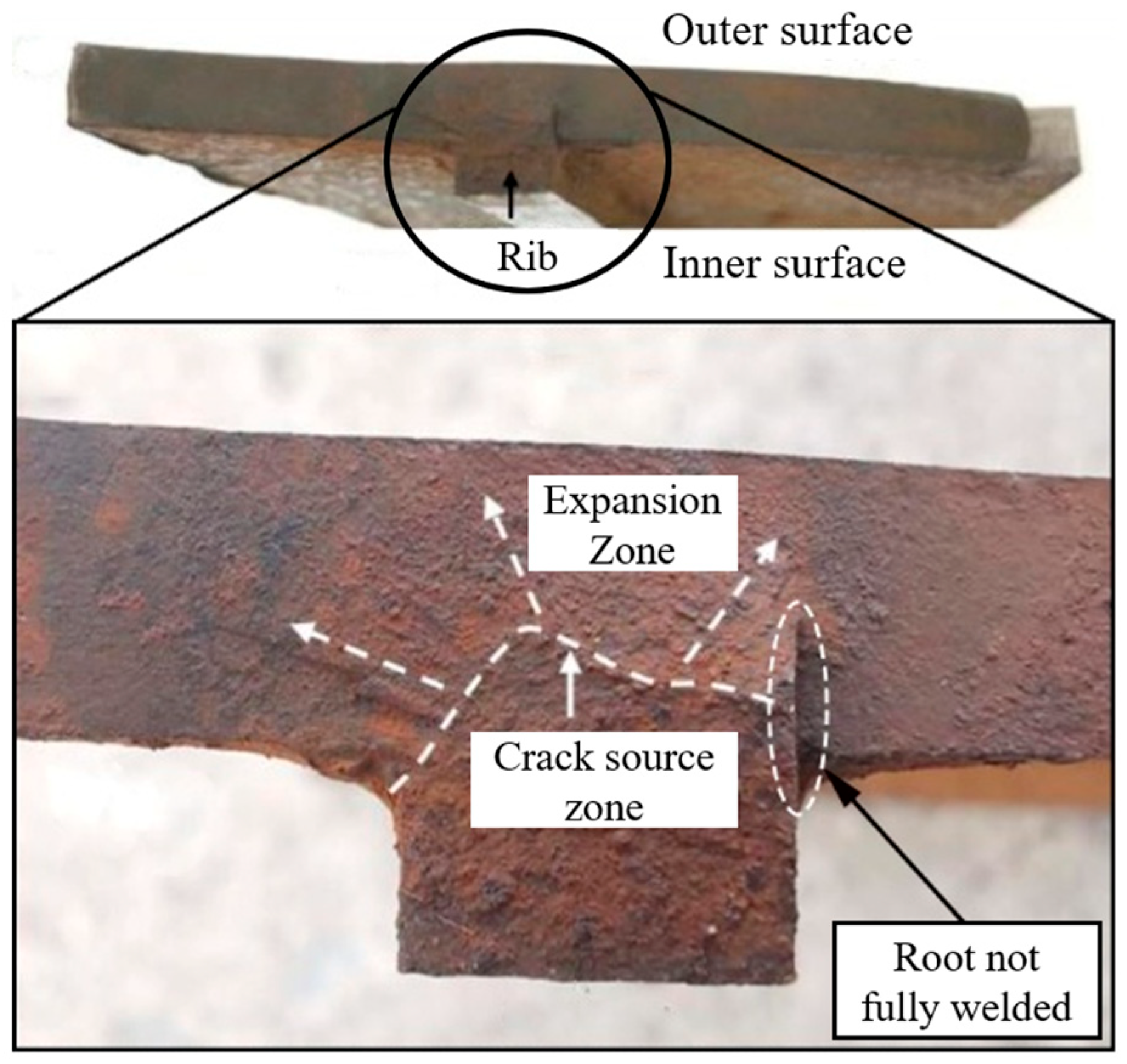

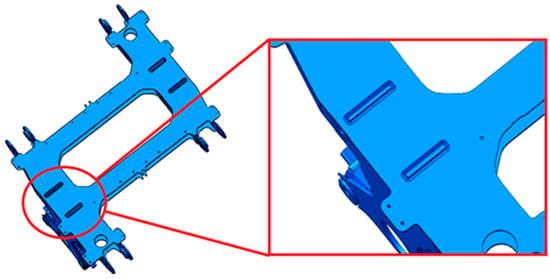

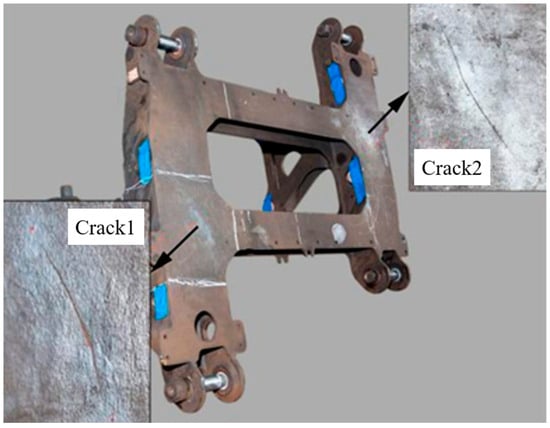

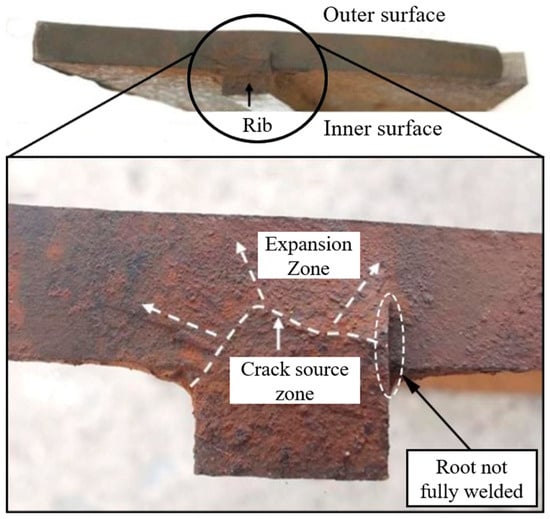

A stress analysis of the motor hanger revealed, through macroscopic fracture examination, a pair of symmetrical cracks about 100 mm long located at the weld between the lower cover plate and the reinforcing rib. The cracks were oriented at an angle of 30–50° relative to the transverse direction of the vehicle, as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. Scanning electron microscopy indicated that the crack source was located in the incomplete penetration zone at the weld root, displaying multi-origin fatigue striations with a maximum depth of 4 mm. The failure was therefore identified as a typical fatigue fracture.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of motor hanger crack location.

Figure 4.

Macroscopic fracture morphology of the crack.

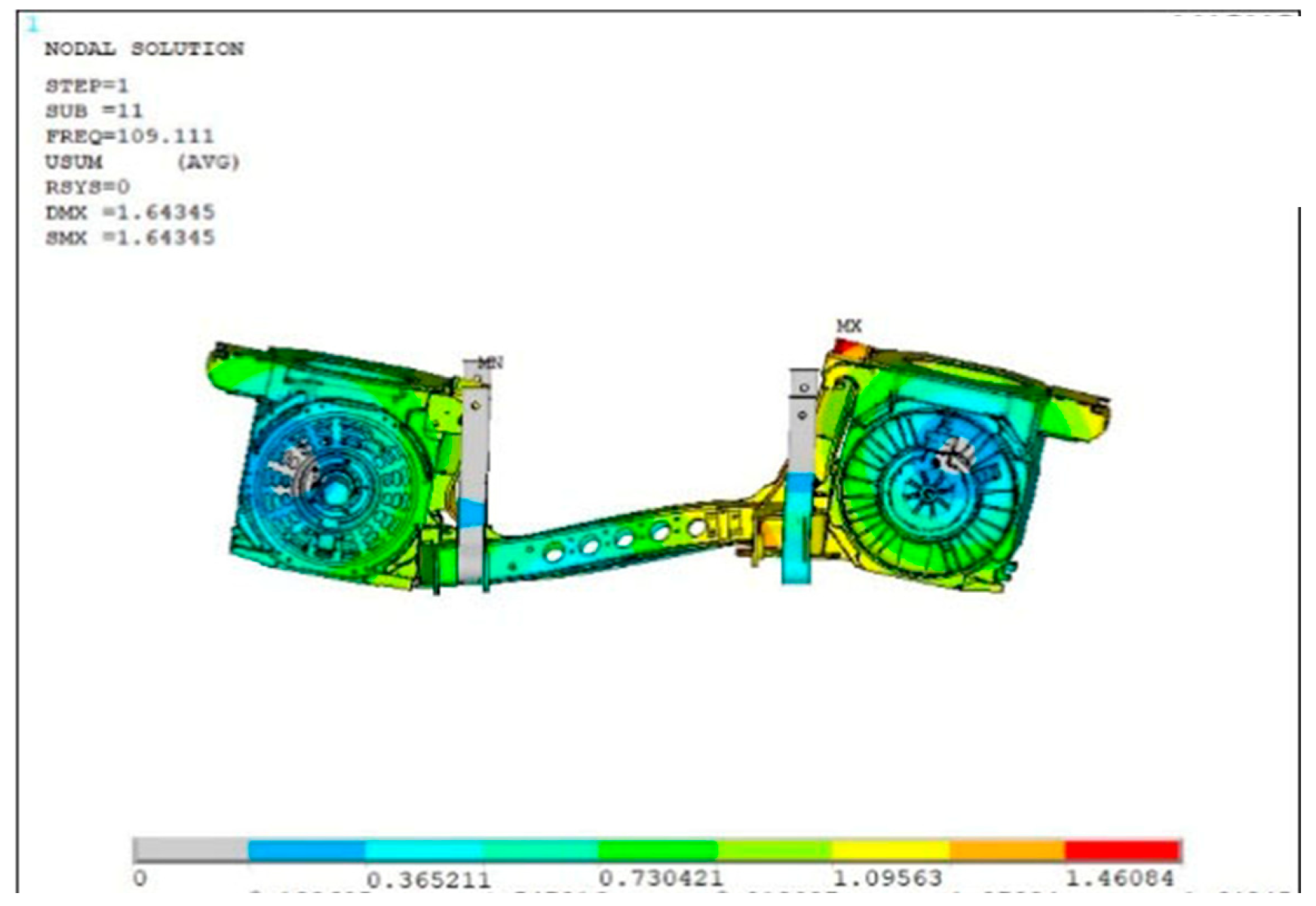

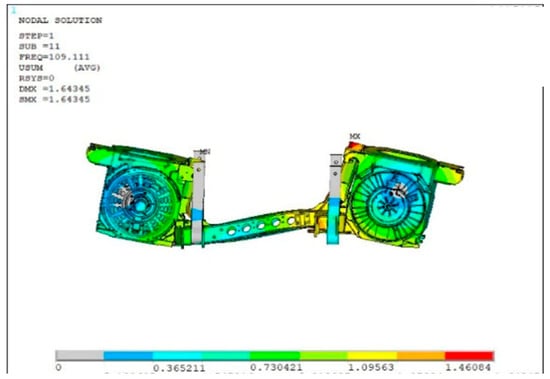

To elucidate the failure mechanism, a finite element model consisting of 799,712 elements was established, as shown in Figure 5. A free modal analysis yielded the first eight natural frequencies, as listed in Table 1. The constrained modal analysis identified a natural frequency of 109.1 Hz, corresponding to an in-phase nodding vibration of the traction motors, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Finite element model of the motor hanger.

Table 1.

Natural frequencies and vibration modes of the motor hanger (free modal analysis).

Figure 6.

Constrained modal vibration shape of the motor hanger.

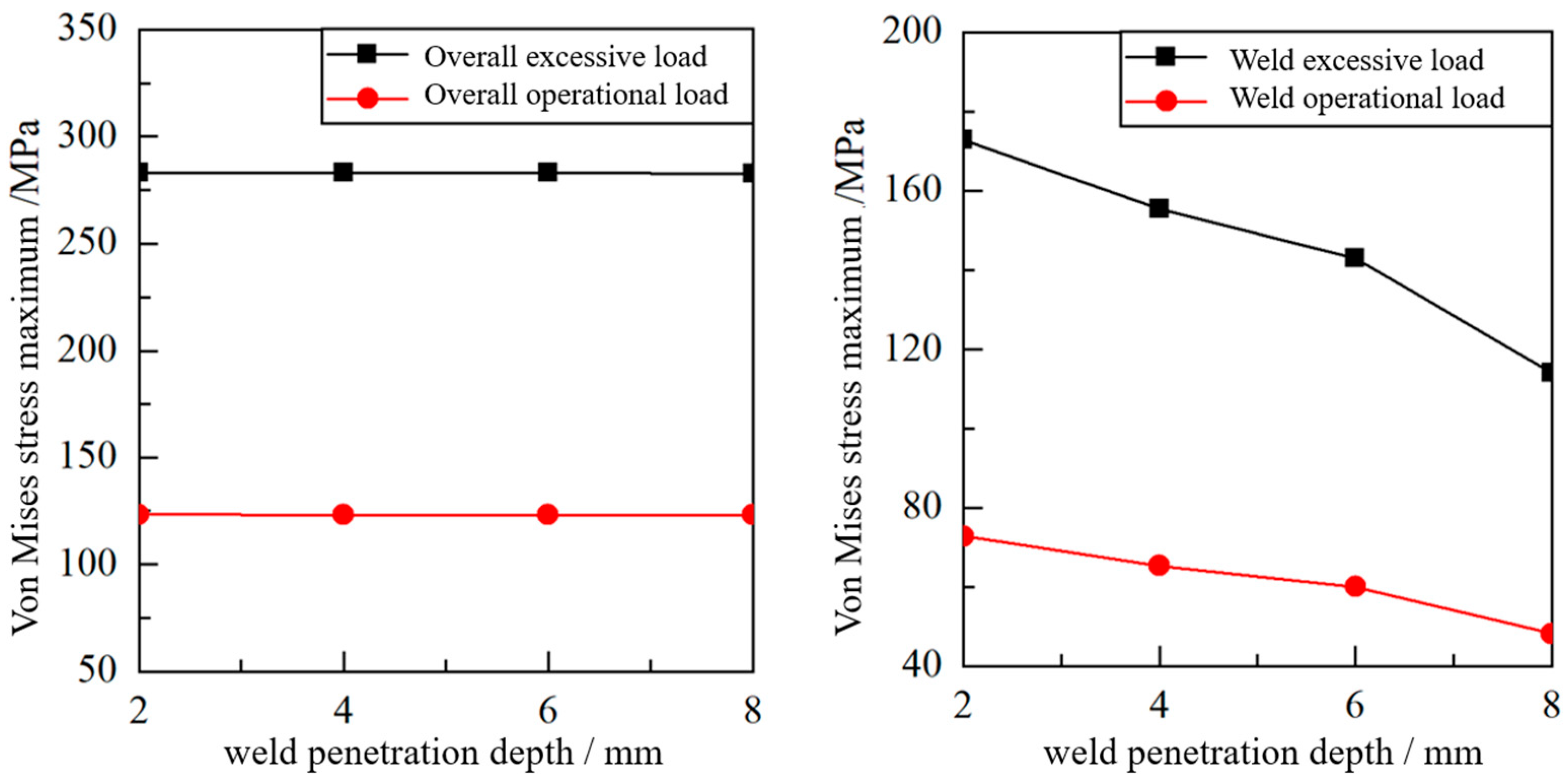

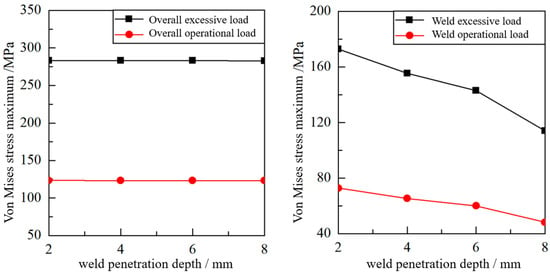

Calculations of both exceptional load cases and simulated service load cases were conducted for the motor hanger under different weld penetration depths, based on the I.S. EN 13749:2021 [25] and measured load data. The focus was on evaluating the effect of weld penetration depth (2–8 mm) on stress distribution. Under exceptional load case 3, the maximum overall stress for a penetration depth of 2 mm was 283.3 MPa, which is below the material yield strength of 355 MPa, giving a residual strength factor of 1.3. However, the stress at the weld significantly increased as the penetration depth decreased; at 2 mm penetration in load case 2, the stress reached 172.9 MPa, which is 51.8% higher than that at 8 mm penetration. A similar trend was observed under simulated service load conditions: the weld stress at 2 mm penetration in load case 2 reached 72.7 MPa, 51.1% higher than that at 8 mm penetration. The corresponding stress trend is shown in Figure 7. These results confirm that while the overall structural stress is relatively insensitive to variations in weld penetration depth, the stress at the weld region increases significantly as penetration depth decreases.

Figure 7.

Stress trend chart.

In this manuscript, the model adopts several assumptions. Material behaviour is treated as linear elastic, and weld geometry is idealized without micro-defects. The reduced-order substructure preserves modal features up to 300 Hz but excludes higher modes. In-service measurements include small uncertainties from mounting and track variation. Fatigue specimens reproduce axial stress amplitudes but do not include full bending torsion effects. While these factors may influence secondary responses, the dominant failure mechanism, near-resonant excitation of the 109 Hz constrained mode by the 100 Hz torque harmonic, remains unchanged.

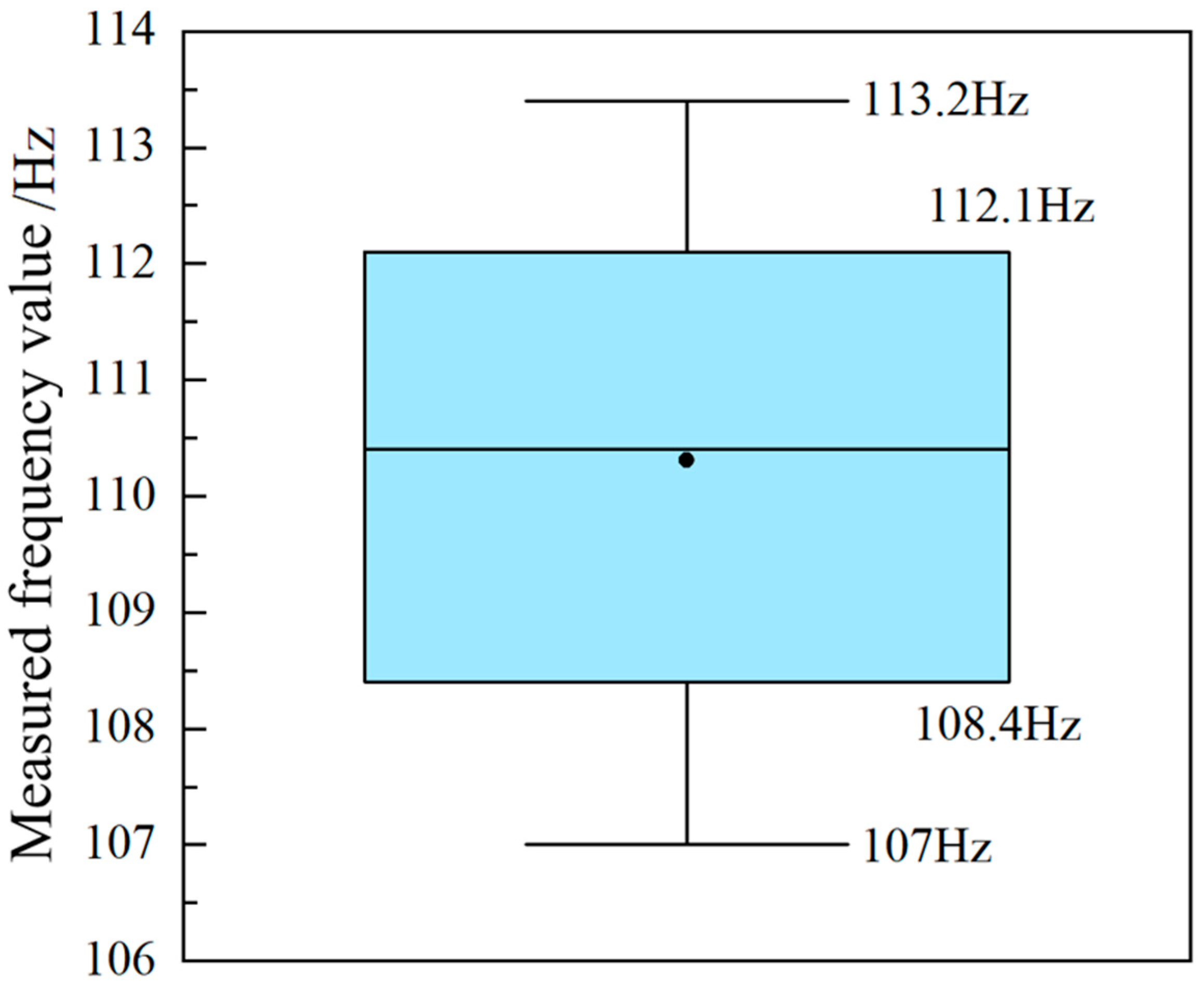

To assess the reliability of the numerical modelling, the simulation results were compared against measured modal and vibration data obtained from multiple in-service trainsets. The constrained modal frequency predicted by the FE model (109.1 Hz) differed from the measured in situ modal range (107–113.2 Hz) by less than 2.1 percent, indicating good consistency in the dominant vibration mode. Under the 100 Hz excitation, the simulated longitudinal acceleration amplitude differed from the measured values by an average of 5.8 percent, while the equivalent weld-root stress amplitude differed by approximately 6.4 percent. These deviations fall within accepted tolerances for rigid–flexible coupled vehicle-system models and demonstrate that the reduced-order FE substructure and co-simulation framework accurately represent the operational dynamic behaviour of the motor hanger.

3. Data Analysis of the Motor Hanger

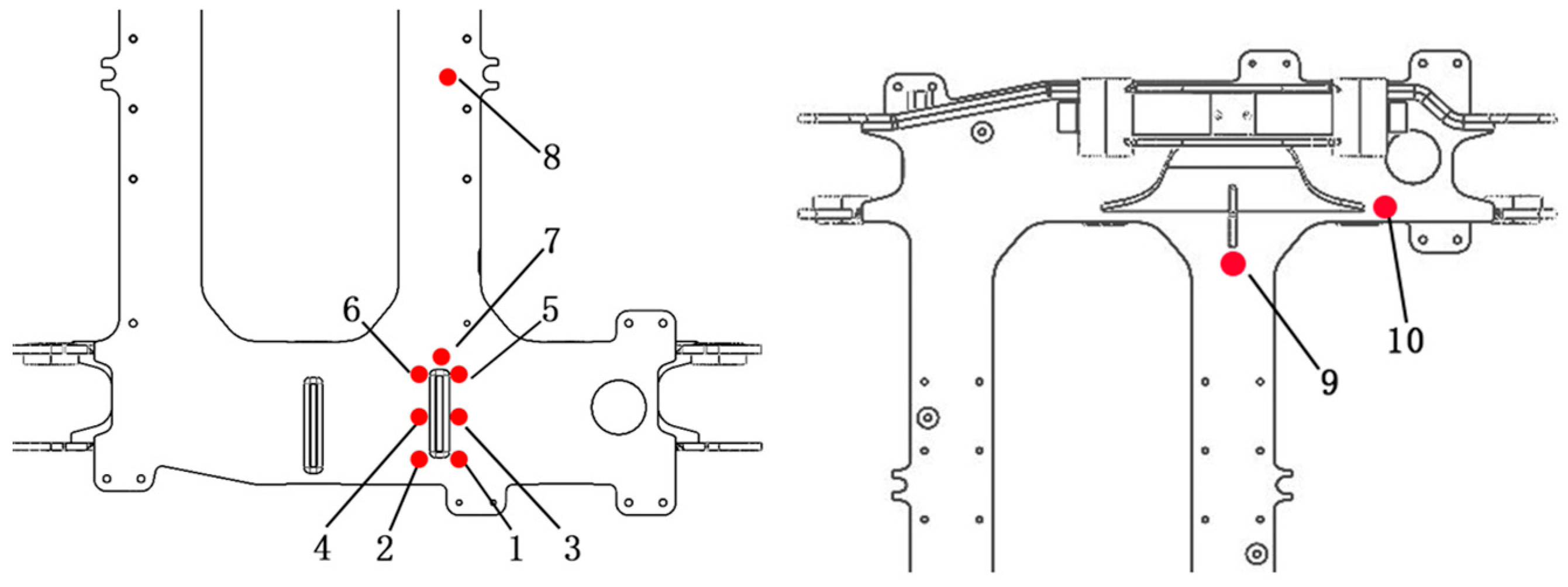

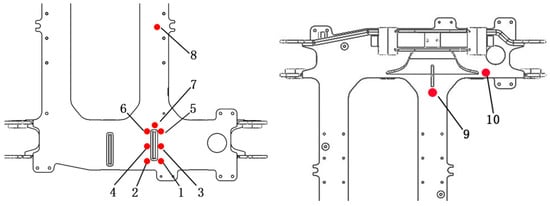

A series of on-track measurements was carried out on the motor hanger, with the measurement point layout shown in Figure 8. The collected random signals were processed using the rainflow counting method to generate a 32-level stress spectrum. Based on Miner’s linear cumulative damage rule, the stresses at each measurement point were converted into constant-amplitude equivalent stresses corresponding to the respective cycle counts. The traction system of the A-type train employed software filtering, while the B-type train used an LC hardware filter. Analysis of the dynamic stress data revealed that, although the number of failures was lower for the B-type train, some measurement points on the B-type exhibited equivalent stresses even higher than those of the A-type train, which showed a greater number of failures.

Figure 8.

Layout of motor hanger measurement points.

The collected on-track stress and acceleration signals were first pre-processed to remove low-frequency drift before being subjected to band-pass filtering to extract the 95–105 Hz component associated with the traction system. The filtered and unfiltered signals were then analyzed using the rainflow counting method to generate a 32-level stress spectrum for each measurement point. Based on the cycle counts obtained, Miner’s linear damage rule was applied to derive the corresponding constant-amplitude equivalent stresses. This workflow provides a clear basis for processing the measured time-domain signals into the stress parameters used in the subsequent analysis.

A comparative frequency-domain analysis of corresponding measurement points from the two train types was carried out using Table 2, revealing key differences. All measurement points on the A-type train exhibited a dominant 100 Hz frequency component. Band-pass filtering confirmed that this component contributed between 8.4% and 66.7% of the equivalent stress. In contrast, for the B-type train, the contribution of the 100 Hz component was only 1.5–13.7%. This indicates that the 100 Hz component plays a major role in the equivalent stress results of the A-type train, but is far less significant for the B-type train.

Table 2.

Analysis of Equivalent Stress Components at Key Measurement Points for A-type and B-type Trains.

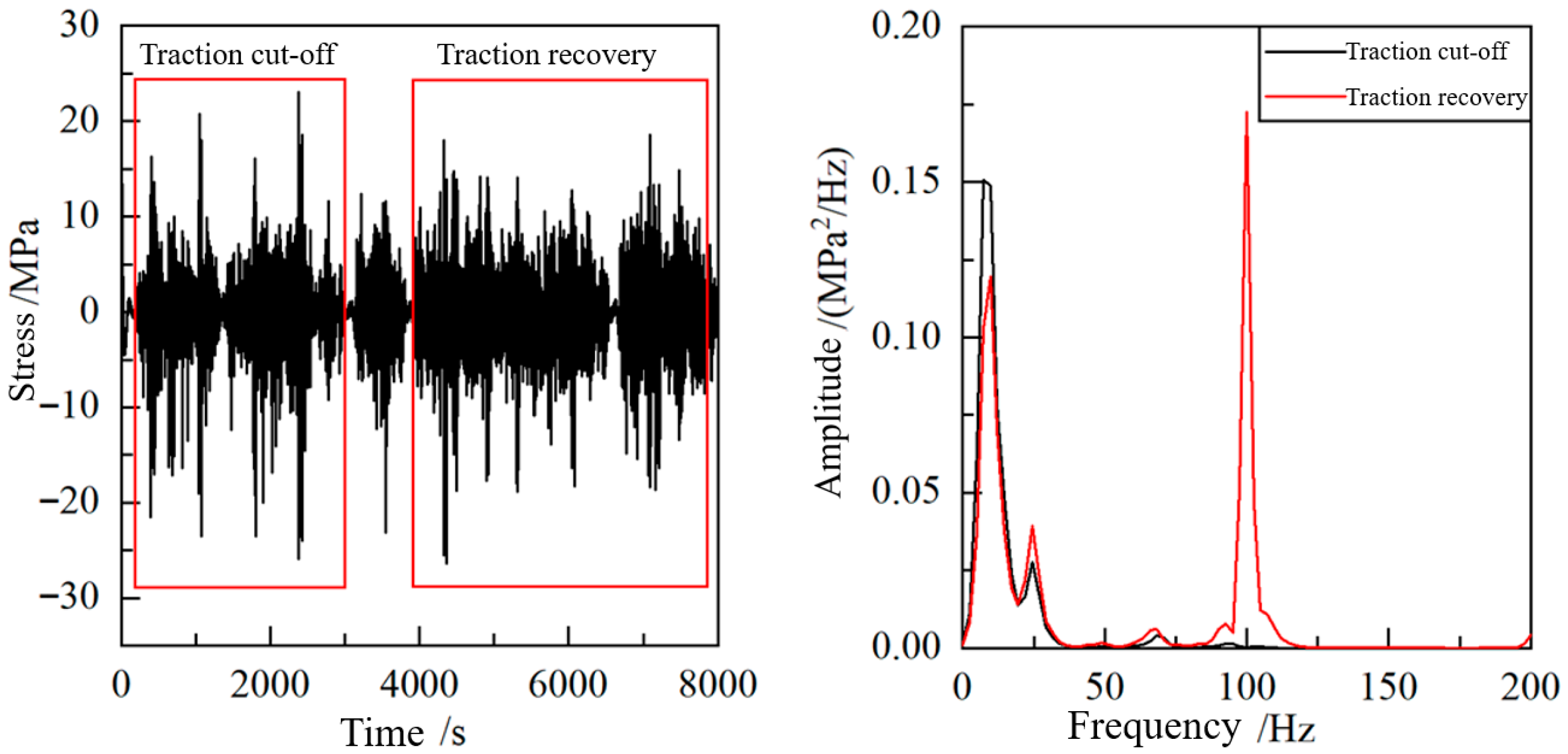

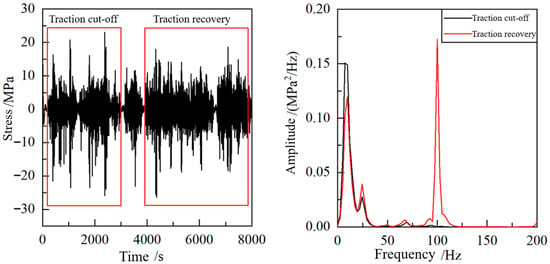

Further verification was conducted using three unloaded measurement points. The 100 Hz amplitude at Point 6 was found to be significantly higher than the power-frequency harmonics, indicating that it cannot simply be treated as a multiple of the power frequency and filtered out. Moreover, the time-domain and frequency-domain diagrams for the traction cut-off and recovery sections, shown in Figure 9, confirmed that the 100 Hz component originates from the traction system.

Figure 9.

Time-domain and frequency-domain diagrams during traction cut-off and restoration.

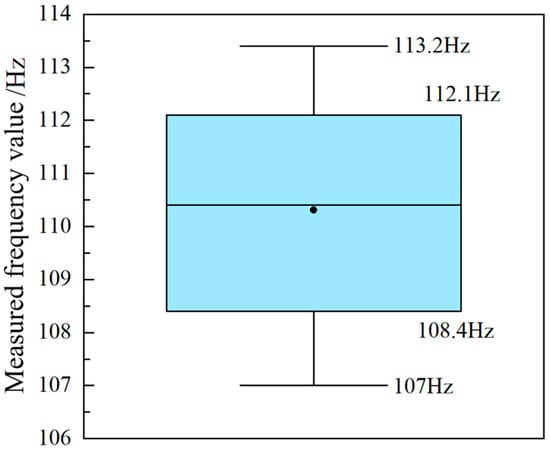

To determine the range of in situ modal values, modal tests of the motor hanger were conducted on multiple trains equipped with the component. The test results, shown in Figure 10, indicate that the natural frequency of the hanger lies between 107 Hz and 113.2 Hz, with most values concentrated in the range of 108.4–112.1 Hz.

Figure 10.

Statistical results of in situ modal testing.

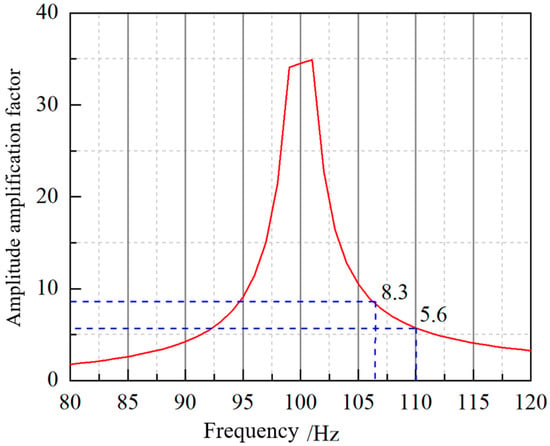

The 100 Hz torque ripple originates from the second harmonic of the traction inverter and coincides closely with the motor hanger’s constrained modal frequency of approximately 109 Hz. This near-resonant condition causes the vibration response to be significantly amplified, leading to larger cyclic deformation at the welded joints. As shown in the frequency response results, even a small difference between the excitation frequency and the modal frequency can produce a large amplification factor. This amplified cyclic loading increases the local equivalent stress at the weld root and accelerates fatigue crack initiation and propagation.

As shown in Figure 11, the amplitude–frequency response curve indicates that the amplification factor reaches 8.3 when the natural frequency is 106.5 Hz, and 5.6 when the natural frequency is 110 Hz. This demonstrates that the closer the natural frequency of the motor hanger is to 100 Hz, the greater the amplification factor becomes, resulting in higher vibration and stress levels under pulsating torque excitation.

Figure 11.

Frequency response curve of the motor hanger under 100 Hz excitation.

The 100 Hz component originates from the inverter and excites the hanger because its constrained natural frequency at 109 Hz lies within the same range. This near-resonant condition produces a large vibration amplification factor of up to 8.3, which intensifies cyclic deformation at the weld root and significantly increases equivalent stress. This explains the high fatigue sensitivity observed in field measurements.

4. Joint Simulation Analysis of the Motor Hanger

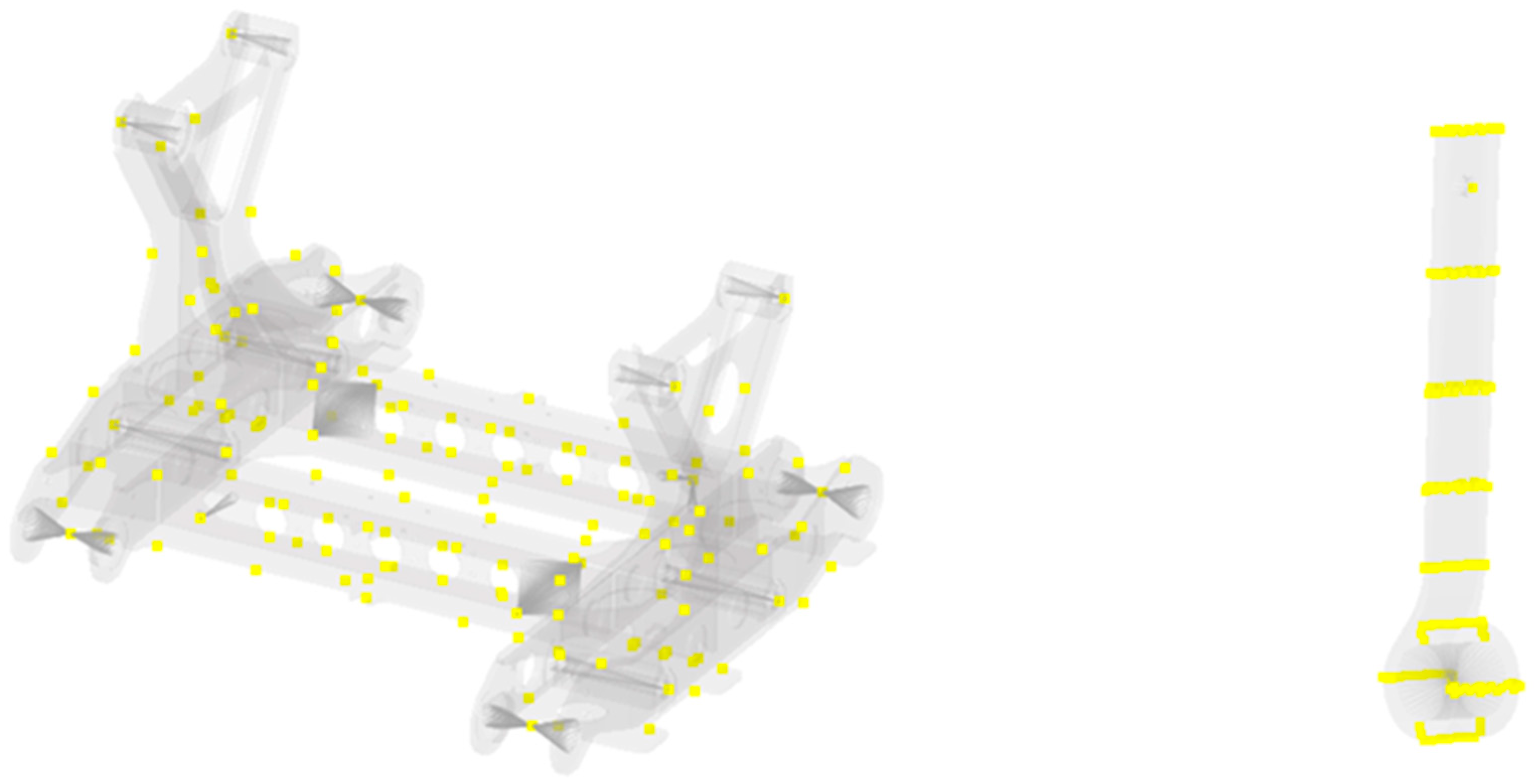

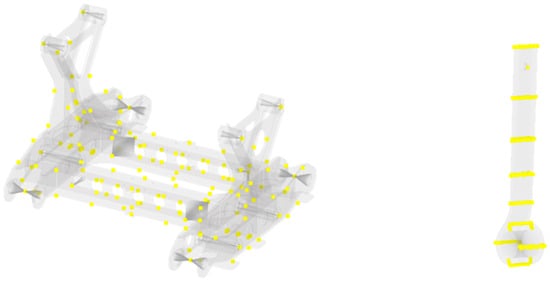

Using the dynamic parameters of a certain type of high-speed EMU as the reference, a system-level dynamic model was developed in accordance with established principles of high-speed vehicle dynamics. The primary nodes of the motor hanger and the elastic suspension rods selected for the model are shown in Figure 12. To ensure accuracy, the motor hanger was reduced into a simplified substructure while preserving its modal characteristics, and the elastic suspension rods were similarly simplified while maintaining fidelity below 700 Hz. Previous finite element and modal analyses confirmed that these reduced models retained the key structural and dynamic features required for reliable system-level simulation. This modelling framework provided the basis for subsequent joint simulations with traction system inputs, enabling evaluation of the vibration and stress response of the motor hanger under pulsating torque excitations.

Figure 12.

Selection of main nodes for motor hanger and elastic suspension rods.

The accuracy of the two reduced substructures was verified. It was found that the modal frequencies of the motor hanger after reduction remained very close to those of the unreduced model, and the elastic suspension rods also showed good agreement below 700 Hz. This confirms that the reduced models were able to faithfully represent the modal characteristics of the original structures.

A wheel–rail interaction model was then developed, with external excitations introduced to improve the accuracy of the simulation. In addition, a gear-pair mesh model was established and validated through offline simulations. The results, based on gear mesh stiffness, tooth contact number, and simulated mesh forces under no external excitation, confirmed that the adopted gear transmission model could reliably capture the characteristics of gear dynamics.

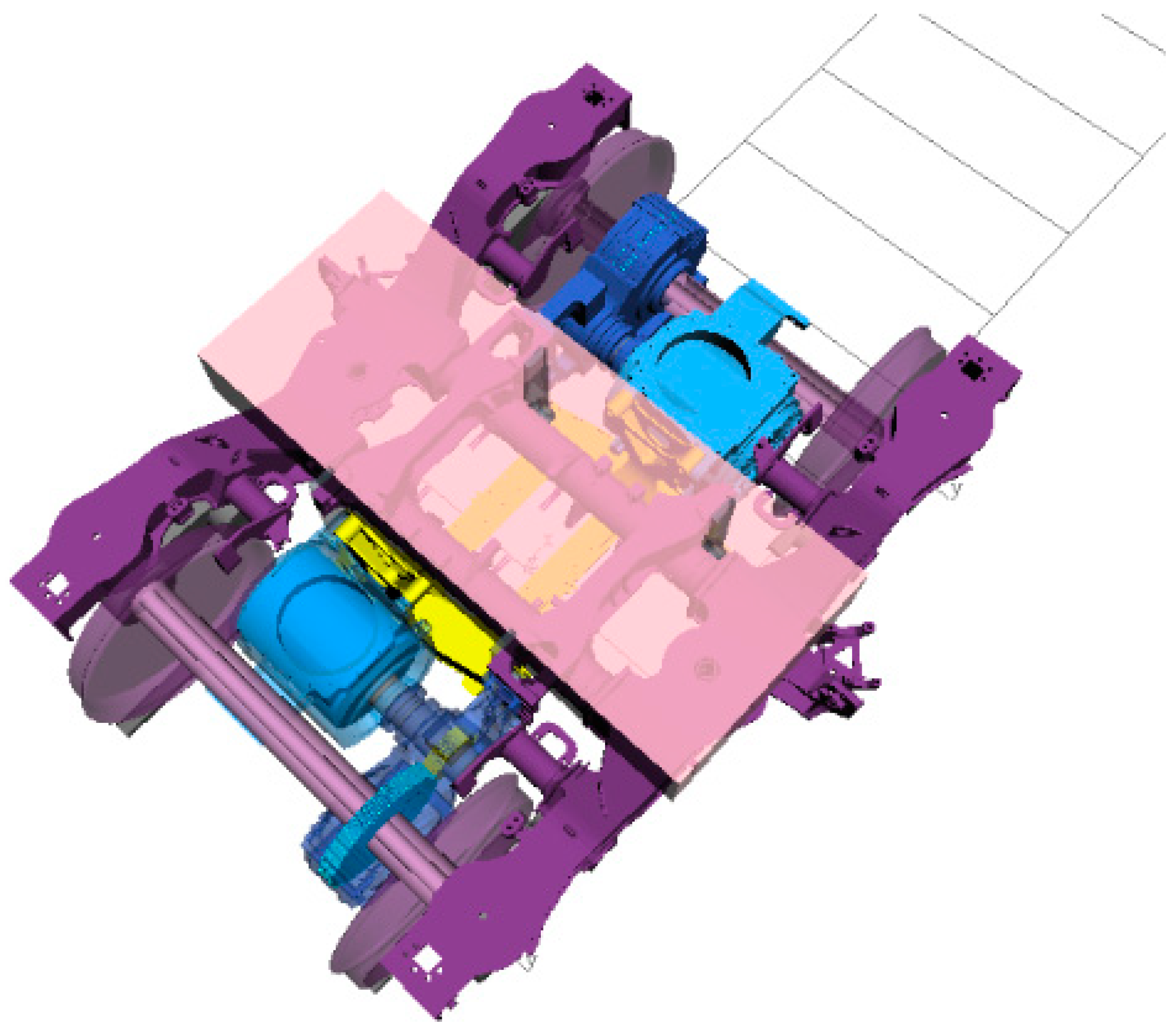

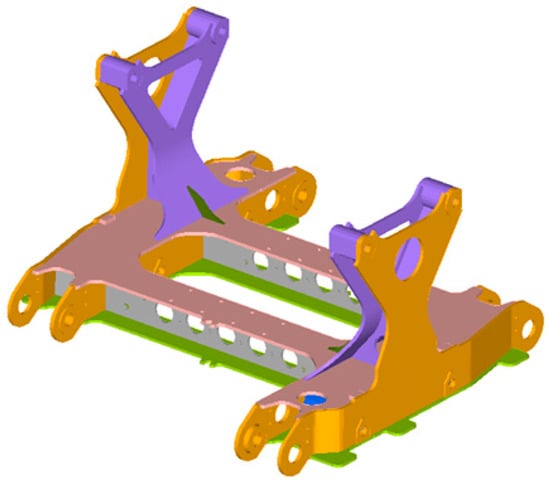

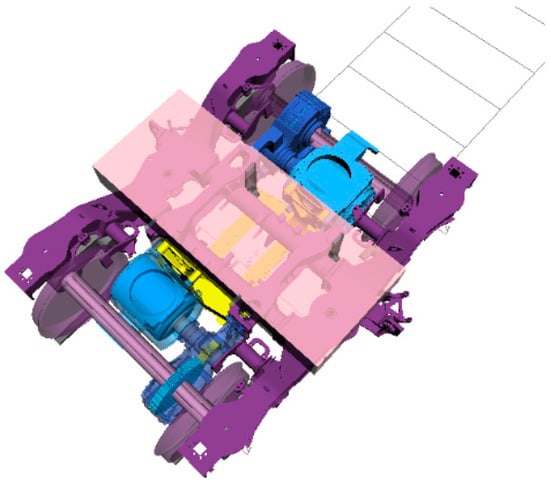

Finally, a coupled rigid–flexible dynamic model of the EMU bogie was constructed in Simpack, as shown in Figure 13, and extended to a full-vehicle model. Simulation results demonstrated that the integrated model provided an accurate and reliable representation of the system’s dynamic behaviour.

Figure 13.

Dynamic model of EMU bogie system.

A simplified torque calculation model was built in MATLAB/Simulink using the two-table power calculation method. The actual torque was obtained from measured current and voltage data, and further corrected using the measured speed curve during trial runs. The corrected torque was then applied as the rotor input in Simpack. Through this Simulink–Simpack co-simulation approach, the train operation was reproduced and the dynamic behaviour of the motor hanger was further analyzed. This co-simulation arrangement was used mainly to allow the measured torque waveform to be applied directly to the dynamic model, which ensures consistency between the recorded excitation and the simulated response. The results showed that the simulated train speed closely matched the measured speed after torque correction, confirming the suitability of the corrected torque as input data for the dynamic model.

Analysis of the motor hanger’s dynamic responses revealed that increasing the motor mass reduced the longitudinal acceleration of the hanger but was less effective in reducing the vertical acceleration, and had little effect on hanger stress. With increasing radial stiffness of the rubber nodes, both longitudinal and vertical vibration accelerations as well as the peak stress response in the 95–105 Hz frequency band, gradually decreased. In contrast, variations in the longitudinal stiffness and damping of the rubber nodes had negligible effects on either acceleration or stress.

5. Discussion: Structural Improvements and Fatigue Life Evaluation of the Motor Hanger

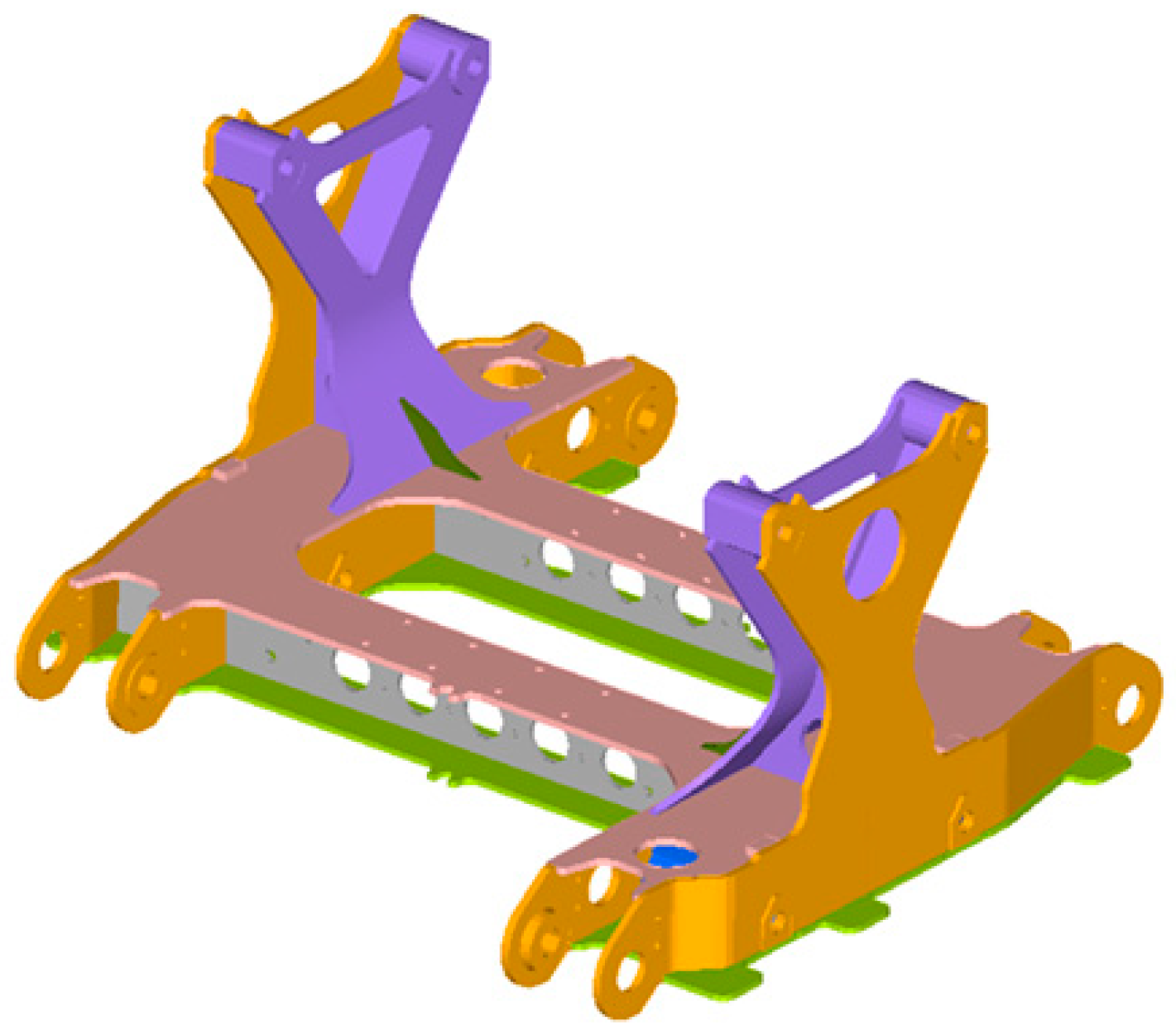

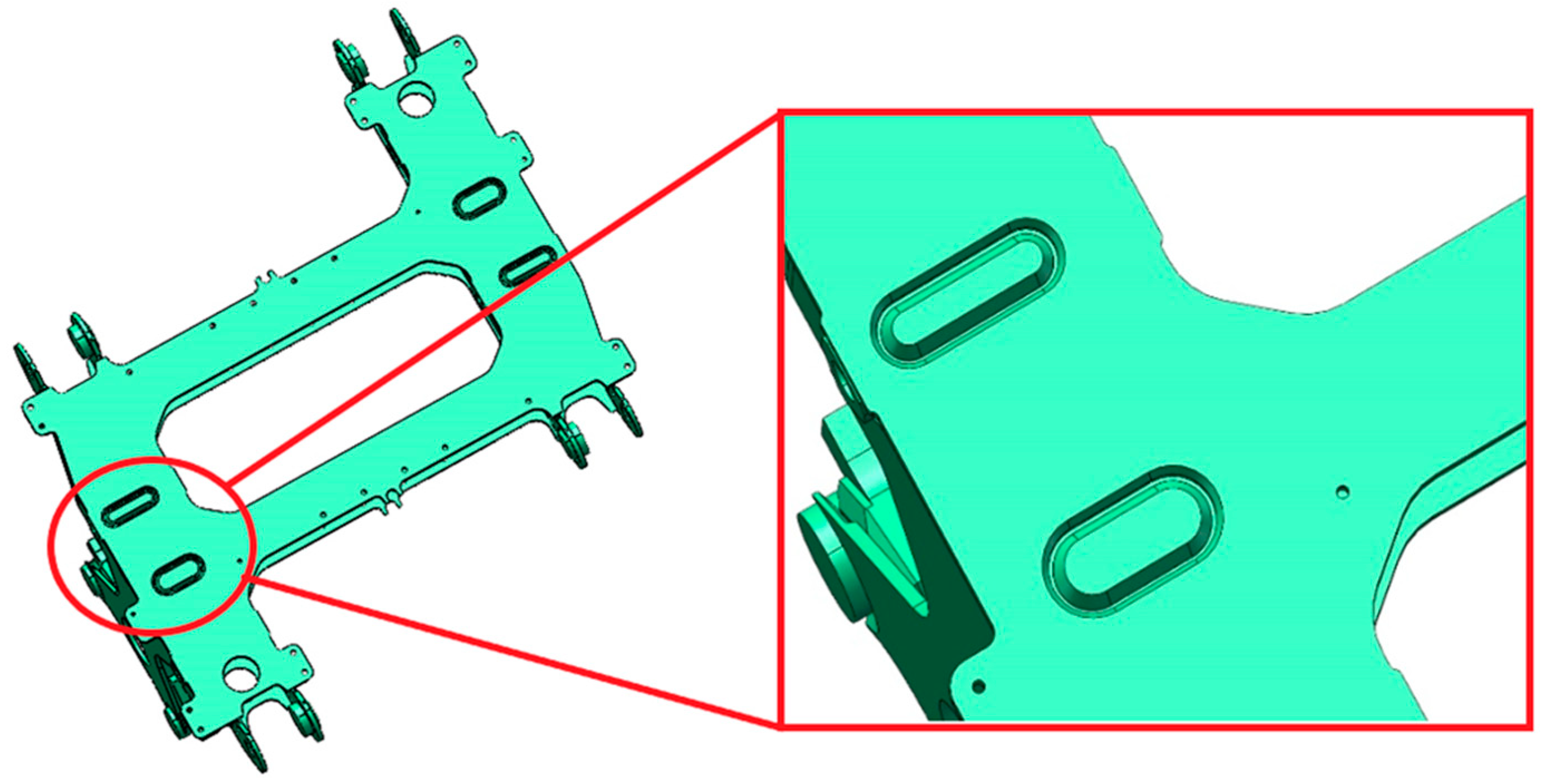

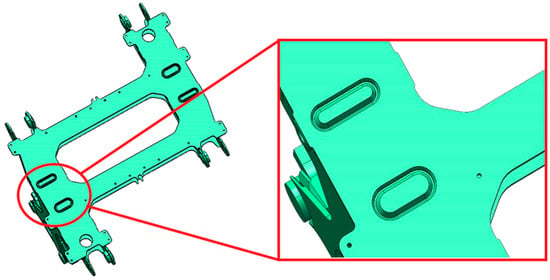

Based on the preceding analysis, a structural improvement scheme was proposed. The thickness of the lower cover plate was increased from 8 mm to 12 mm, and the underside of the stiffening plate was reshaped with a rounded profile to create a smoother load path. To improve weld quality, the weld region was redesigned with a curved transition and a V-groove preparation to facilitate welding operations and ensure sufficient post-weld penetration. The improved motor hanger geometry and the revised weld groove configuration are shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

New motor hanger geometric structure.

Finite element simulations were conducted on the improved motor hanger to extract its constrained modal frequencies. The results showed that the resonance mode occurred at 111.3 Hz, which is slightly higher than the 109.1 Hz of the original structure. Consequently, the amplification factor of the new hanger was reduced to 4.9. Static and fatigue strength analyses further confirmed the improvement: under exceptional load conditions, the maximum stress of the new hanger was 265.5 MPa, lower than the material yield strength of 355 MPa and slightly reduced compared with the original design. Examination of the weld regions showed that the maximum stress reached 103 MPa, also lower than that of the original hanger. The peak stress in the improved design appeared at the rounded corner of the internal web, while the stresses in the weld zone were comparatively low, demonstrating that the structural modifications significantly reduced weld stress. Under service load conditions, the maximum overall stress was 114.7 MPa, and the maximum stress in the weld region was 42.9 MPa, again located at the rounded corner of the internal web.

Field tests were then carried out by installing the improved motor hanger on an A-type trainset. The test route and measurement point locations were kept identical to those used for the original hanger. The results showed that the equivalent stresses at all measurement points of the improved hanger were well below the allowable stress of the welds. Compared with the original hanger, equivalent stresses at corresponding points were reduced by 33.3% to 54.0%, confirming the significant effect of the structural modifications in lowering weld stresses. Frequency-domain analysis further revealed that although the dominant frequency of the measurement points remained unchanged, the amplitude of the improved hanger was markedly reduced. Under the same pulsating torque excitation, the stress amplitude of the improved hanger was consistently lower than that of the original hanger. The field measurements and simulation results consistently showed the same dominant 100 Hz resonance-driven behaviour across different trains and runs, indicating that the main findings are robust to measurement variability. Alternative structural concepts were considered; however, the priority of this work was to provide an improvement that could be implemented rapidly on existing fleets without major redesign or changes to material systems.

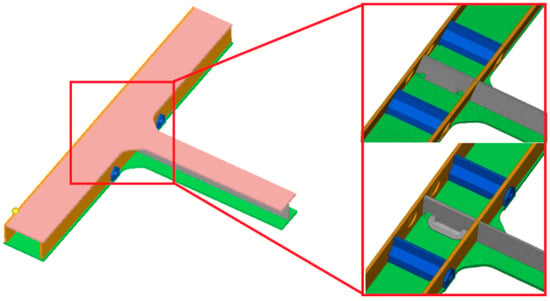

Finally, bench fatigue tests were performed. The simplified tension–compression loading was selected because it captures the dominant axial stress acting at the weld root, which is the main fatigue driving component identified in the analysis. Finite element analysis showed that the weld-root stress is dominated by axial cyclic loading under the 100 Hz excitation, so the simplified tension–compression setup was sufficient to reproduce the primary fatigue-driving stress at the weld. Finite element analysis indicated that axial cyclic stress is the dominant loading component at the weld root under the 100 Hz excitation, so a simplified tension–compression setup was sufficient to reproduce the key fatigue-driving stress in the specimens. To preserve the integrity of the target weld structure while simplifying the test, the motor hanger was reduced to representative specimens subjected to simple tension–compression loading to simulate the stresses at the welds. The simplified specimens of both the original and improved hangers are shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Simplified test specimens of motor hanger.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the fatigue strength and vibration behaviour of a high-speed EMU motor hanger using a combination of finite element analysis, line testing, joint simulation, and bench validation. The results demonstrated that the hanger’s constrained natural frequency was 109.1 Hz, corresponding to synchronous nodding vibration, and that high stress originated from incomplete weld penetration. A reduction in weld penetration was shown to significantly increase stresses in the welded regions. Field measurements revealed that a 100 Hz torque ripple, close to the natural frequency, excited elastic vibration of the hanger, resulting in elevated stress levels and fatigue failure, with both stress and acceleration increasing alongside torque ripple amplitude. Hangers with lower modal frequencies exhibited higher stresses, consistent with frequency response analysis. Joint dynamic simulation further showed that while increasing motor mass effectively reduced longitudinal acceleration, it had little effect on vertical acceleration, whereas increasing the radial stiffness of rubber nodes markedly decreased vibration and stress responses in the 95–105 Hz frequency range. Based on these insights, a series of structural improvements were implemented, including optimized weld geometry and increased plate thickness, which were validated by line tests showing substantial reductions in both weld stress and equivalent stress. Finally, bench fatigue tests confirmed that the improved design achieved a fatigue life exceeding 15 million km, more than twice that of the original structure, thereby fulfilling the service requirements. The main contribution of this work is clarifying the cause of the high-stress behaviour and confirming the effectiveness of a practical improvement strategy using combined analysis and testing. These findings provide a comprehensive understanding of the underlying failure mechanisms and confirm the effectiveness of the proposed design improvements in enhancing the safety and reliability of high-speed EMU motor hangers.

While this study does not present a clause-by-clause comparison with engineering standards such as EN13749, the improvements achieved in modal response, resonance sensitivity, and weld stress behaviour reflect the performance objectives commonly required for bogie-mounted components in international practice. These outcomes indicate that the proposed modelling approach contributes new insight to the body of knowledge on fatigue-critical suspension components and provides a foundation for future work aimed at integrating this method into formal standards-based verification processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Z., C.Y. and Y.S.; methodology, R.Z.; software, R.Z.; validation, R.Z., C.Y. and Y.S.; formal analysis, R.Z.; investigation, R.Z.; resources, R.Z.; data curation, R.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Z.; writing—review and editing, C.Y. and Y.S.; visualization, R.Z.; supervision, C.Y. and Y.S.; project administration, R.Z.; funding acquisition, R.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China Academy of Railway Sciences Group Co., Ltd. Program (2023YJ324).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to commercial confidentiality and restrictions imposed by the railway operator and manufacturers. Data may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and subject to institutional approval.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the China Academy of Railway Sciences Group Co., Ltd. Program (2023YJ324). The authors thank all contributors who assisted with the work reported in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Rui Zhang was employed by the company China Academy of Railway Sciences Corporation Limited (CARS). Authors Chi Yang and Youwei Song were employed by the company CRRC Changchun Australia Rail PTY Ltd. The authors declare that this study received funding from China Academy of Railway Sciences Co., Ltd. Program (2023YJ324). The funder had the following involvement with the study: study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EMU | Electric Multiple Unit |

| FEA | Finite Element Analysis |

| LC | Inductor–Capacitor |

| S–N curve | Stress–Number curve |

References

- Wang, H. Electrical System of CRH380CL High-Speed EMU. Mod. State-Own. Enterp. Res. 2016, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Sun, X. Simulation Study of Reinforcement Structure Welding Repair for EMU Motor Hanger. Weld. Technol. 2020, 49, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z. Fatigue Phenomenon of Metal Structures and Measures to Improve Fatigue Strength. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2010, 2, 934–955. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, S.; Cho, I.; Yoon, D. Fatigue life evaluation of mechanical components using vibration fatigue analysis technique. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2011, 25, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Wang, Y.; Song, Y. Static and fatigue strength analysis of high-speed EMU bogie frame. Mech. Eng. Autom. 2014, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, G.; Yu, H.; Ma, Y. Fatigue strength simulation analysis of EMU gearbox. J. Chongqing Univ. Technol. Nat. Sci. 2020, 34, 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- He, N.; Feng, P.; Li, Z.; Tan, L.; Pang, T.; Chen, Y.; Yang, C. Fatigue life prediction of centrifugal fan blades in the ventilation cooling system of the high-speed train. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 124, 105373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, W.; Ren, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, F.; Wu, S.; Li, Z.; Han, X. Strength and life assessment of TC4 titanium alloy welded bogie for high-speed trains. Trans. China Weld. Inst. 2022, 43, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B. Study on Fatigue Strength of High-Speed EMU Wheelsets. Ph.D. Thesis, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tonamachi, N.; Zhang, J. Method for Suppressing Ripple Phenomena in Rectifier and Inverter Systems. Electr. Tract. Bull. 1994, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jahns, T.; Soong, W. Pulsating Torque Minimization Techniques for Permanent Magnet AC Motor Drives—A Review. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 1996, 43, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Zeng, J.; Huang, C.; Qi, Y. Influence of motor hanger suspension parameters on bogie dynamic performance of high-speed EMU. J. Vib. Shock. 2018, 37, 95–100+108. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Wu, X.; Chen, Z. Analysis and calculation of harmonic torque of asynchronous traction motors for high-speed trains. J. Chongqing Univ. Technol. Nat. Sci. 2013, 27, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Li, W. Vibration characteristics simulation of traction motor drive device. J. China Railw. Soc. 2013, 35, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Yu, J.; Cao, L.; Hu, J.; Zhu, L.; Liu, J.; Wu, Q.; Li, Q.; Xu, L. Application of multibody dynamics in mechanical engineering. Hubei Agric. Mech. 2019, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Kamat, H.; Pai, A.; Vernekar, N.K.; Kini, C.R.; Shenoy, S.B. Topological optimization and fatigue life prediction of a single pad externally adjustable fluid film bearing. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, S.; Bonisoli, E.; Rosso, C.; Velardocchia, M. A tyre-rim interaction digital twin for biaxial loading conditions. Mech. Mach. Theory 2024, 191, 105491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Cen, H.-T.; Guo, W.; Li, L.; Na, R.-S. Fatigue Analysis and Structural Optimization Design of the Slot of Knotted Frame of the Square Baler. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1043, 032073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhai, W.; Shao, Y.; Wang, K.; Sun, G. Analytical model for mesh stiffness calculation of spur gear pair with non-uniformly distributed tooth root crack. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2016, 66, 502–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Shao, Y. Dynamic simulation of spur gear with tooth root crack propagating along tooth width and crack depth. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2011, 18, 2149–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claus, H.; Schiehlen, W. Modeling and Simulation of Railway Bogie Structural Vibrations. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2007, S1, 538–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, L.; Fayos, J.; Roda, A.; Insa, R. High frequency railway vehicle-track dynamics through flexible rotating wheelsets. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2008, 46, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leva, S.; Morando, A.; Colombaioni, P. Dynamic Analysis of a High-Speed Train. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2008, 57, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Deng, X. Electromechanical coupling model of high-speed EMU under direct torque control. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2015, 12, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar]

- EN 13749; Railway Applications—Wheelsets and Bogies—Method of Specifying the Structural Requirements of Bogie Frames. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.