Abstract

Background: Artificial Intelligence (AI) holds significant potential to enhance operational efficiency and quality in healthcare. However, despite substantial investment, its widespread, sustained implementation is limited, necessitating a thorough risk assessment to overcome current adoption barriers. Methods: This scoping review, guided by the Arksey and Malley framework, systematically mapped 13 articles published between 2019 and 2024, sourced from five major databases (including CINAHL, Medline, and PubMed). A rigorous, systematic process involving independent data charting and critical appraisal, using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool, was implemented, followed by thematic synthesis to address the research questions. Results: AI demonstrates a significant positive impact on both operational efficiency (e.g., optimised resource allocation, reduced waiting times) and patient outcomes (e.g., improved patient-centred, proactive care, and identification of readmission risks). Major implementation hurdles identified include high costs, critical data security and privacy concerns, the risk of algorithmic bias, and significant staff resistance stemming from limited understanding. Conclusions: Healthcare managers must address key challenges related to cost, bias, and staff acceptance to leverage the potential of AI fully. Strategic investments, the implementation of robust data governance frameworks, and comprehensive staff training are crucial steps for mitigating risks and creating a more efficient, patient-centred, and effective healthcare system.

1. Introduction

Digital technologies are fundamentally reshaping operations across numerous industries, with 85% of executives viewing digitisation as critical for organisational success [1,2,3] Artificial intelligence (AI) has become a key driver of this transformation, and its integration into healthcare has garnered significant focus [4,5,6,7,8]. The potential for AI to enhance the efficiency and quality of healthcare is increasingly evident, particularly its ability to leverage “big data” for evidence-based clinical decisions and value-based care [9,10,11]. Research affirms that AI-powered health applications are both practical and promising, attracting substantial investment from technology firms and governments alike [12,13,14].

Despite this promise, the integration of AI into healthcare management presents a distinct set of challenges that modern managers must navigate [15,16,17]. While AI has advanced remote diagnostics, optimised resource allocation, and improved supply chain management, the number of successful, long-term implementations remains surprisingly small [18,19]. High implementation costs, algorithmic bias, data security risks, and pressing ethical concerns create significant hurdles that complicate the path to adoption [20,21]. Furthermore, policy and ethical guidelines have failed to keep pace with technological advancements, creating a regulatory vacuum that could threaten patient safety and data privacy [22]. Without a clear strategy for integrating AI into existing infrastructure and providing necessary staff training, its transformative potential may go unrealised, ultimately hindering the delivery of quality care [23,24].

1.1. Rationale and Gap of the Study

The rationale for adopting AI in healthcare is compelling. The sector generates an enormous volume of data—an estimated 30% of the world’s total—and faces persistent challenges, including rising costs and workforce shortages [25,26]. AI offers a powerful means to analyse this data, creating management tools that can optimise resource allocation, automate scheduling, and improve patient flow, thereby enhancing community well-being [27,28,29]. By improving patient experiences and reducing per capita costs, AI can help achieve the quadruple aim of healthcare: better outcomes, improved patient experience, lower costs, and improved clinician experience [30,31].

However, a critical appraisal of the existing literature reveals a significant conceptual gap. Current research extensively documents the potential benefits of AI [32,33,34] and identifies the barriers to its adoption [35]. Yet, there is a lack of in-depth analysis focusing on the organisational and managerial factors that are crucial for successful, long-term implementation. While studies acknowledge the need for strategic planning and digital maturity [36,37], a comprehensive understanding of how healthcare organisations can effectively navigate the challenges mentioned above remains underdeveloped [38,39,40,41]. Therefore, this study aims to address this gap by investigating the key organisational factors that influence the effective adoption and integration of AI-driven solutions within healthcare management.

1.2. Research Questions

To address the broad scope of Artificial Intelligence (AI) integration in healthcare, this scoping review is guided by the following operationalised research questions:

- What is the scope and nature of evidence describing the impact of AI on key indicators of operational efficiency and patient outcomes within healthcare settings?

- What organisational, technical, ethical, and regulatory factors are identified in the literature as key challenges (barriers) and opportunities (enablers) for the successful implementation of AI in healthcare?

1.3. Research Aim and Objective

This study aims to conduct a scoping review to comprehensively map the existing literature on the integration of AI in healthcare management. Unlike a systematic review that seeks to answer a narrow clinical question, this scoping review aims to delineate the breadth of available evidence, identify key concepts, and highlight knowledge gaps in the field.

The specific objectives are:

- To map and categorise the evidence describing AI’s impact on specific operational efficiency metrics (e.g., workflow automation, resource management) and patient outcomes (e.g., diagnostic accuracy, patient safety).

- To identify and synthesise the key organisational, technical, and ethical factors reported in the literature as barriers and enablers to AI implementation in healthcare.

- To identify key characteristics of the existing research landscape, including standard methodologies and conceptual approaches, and to highlight knowledge gaps to inform future research and policy.

1.4. Significance of the Study

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare remains limited, even with its growing popularity [19]. Despite extensive scholarly discussion on the significance, challenges, and benefits of these strategies, a gap remains in knowledge regarding practical implementation approaches for healthcare leaders. This study seeks to inform healthcare organisations on how AI can improve service delivery and how to navigate implementation challenges. This information will help healthcare organisations develop and adopt effective implementation frameworks.

2. Materials and Methods

This chapter outlines the methodology for this scoping review, including the search strategy, inclusion criteria, data extraction, and synthesis approach used to map the existing literature on AI integration in healthcare.

2.1. Research Design

The authors did not formally pre-register the protocol for this scoping review with a dedicated registration number on a platform such as PROSPERO or the Open Science Framework (OSF). The full details of the review methodology are presented herein and are also available in the Section 2.7. The methodological framework used in this review was based on the scoping review framework by Arksey and Marley [42] and the methodological guidelines from the Joanna Briggs Institute [40]. The methodological framework followed five distinct stages: (1) defining the research question and its clear objective; (2) finding and choosing pertinent studies; (3) extracting and charting data for analysis; (4) grouping, summarising, and evaluating the results; and (5) presenting the findings. We conducted this review in accordance with the methodological framework. This framework is helpful for preliminarily mapping or assessing available evidence on the use of AI in healthcare, and for identifying key concepts and knowledge gaps without requiring an in-depth synthesis of methodological quality [43,44]. However, for this specific scoping review, the researchers conducted a quality appraisal of all chosen articles to ensure methodological rigour and thoroughness. The primary objective of this research was to review the literature on how AI technologies enhance care delivery. By highlighting the extent of coverage or the gaps in this field, the findings could inform future research and policy recommendations. Additionally, a systematised approach enables duplication of the process. The research scope was defined using the Population, Concept, and Context (PCC) framework [Table 1], as outlined by [45]. The “population” included clinical and non-clinical staff, such as healthcare workers, managers, administrators, leaders, patients, and healthcare systems, who are directly affected by the implementation of AI. The “concept” was defined as enhancing service provision through the integration of AI. The “context” was specified as healthcare settings, including hospitals and healthcare organisations globally, over the last decade, reflecting the current state and advancements in AI.

Table 1.

Population, Concept, and Context (PCC) framework.

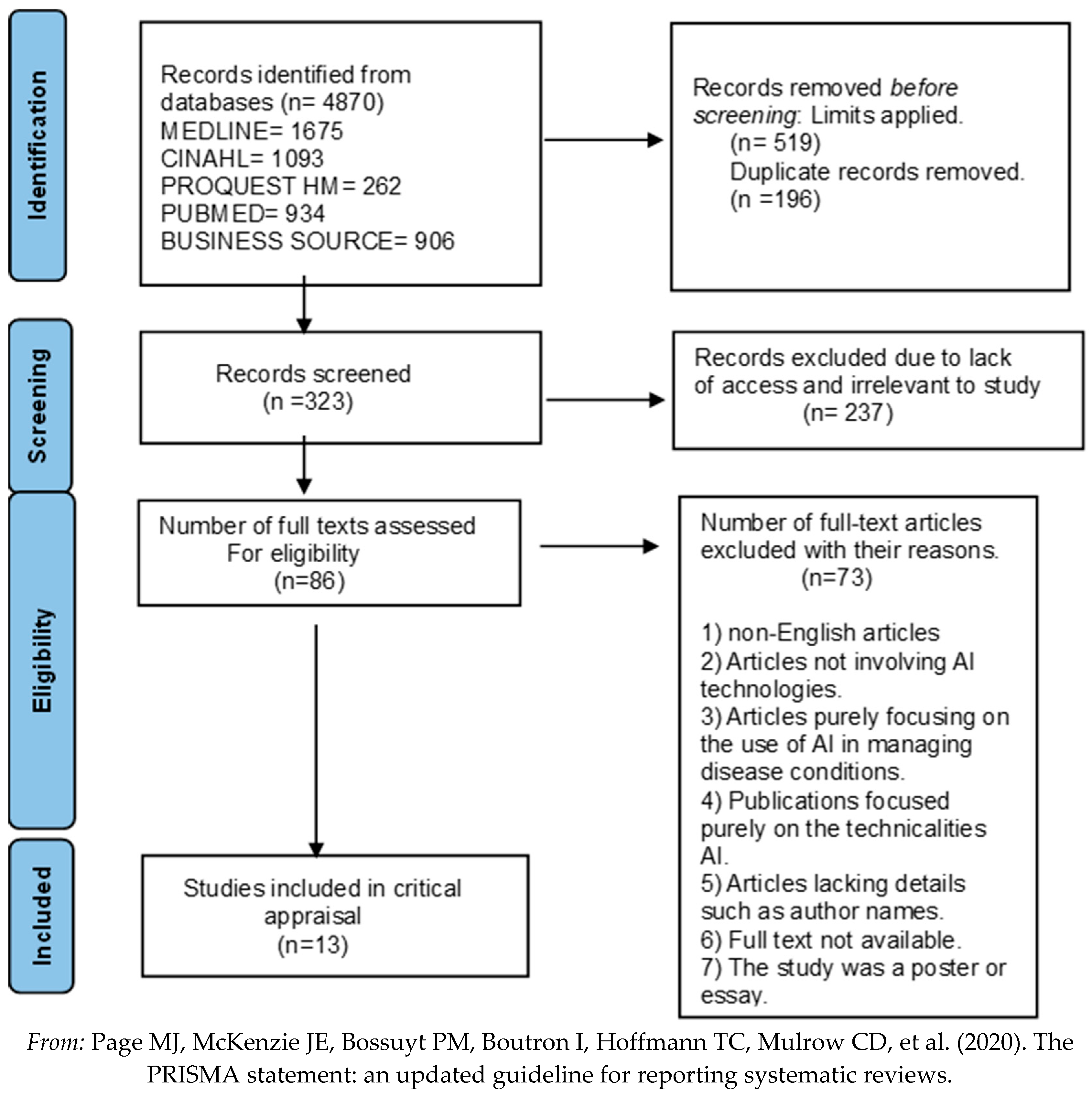

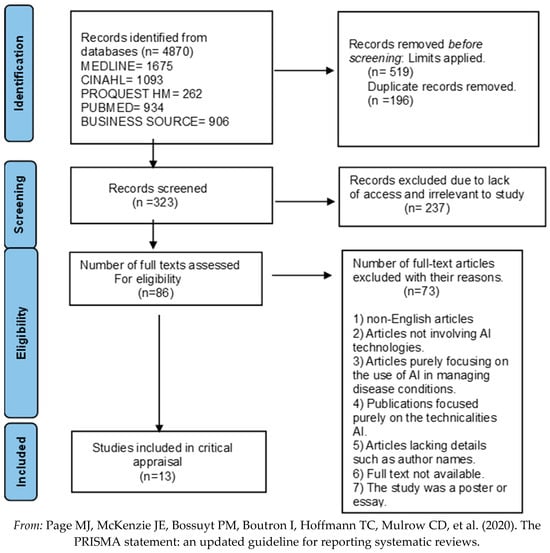

A systematised scoping review shares key characteristics with a systematic review, such as being systematic, duplicable, and transparent [46]. This approach allowed for the use of a flow chart that adheres to the guidelines of the PRISMA 2020 statement and the PRISMA-S extension for documenting the search process [47]. The researchers maintained a comprehensive and consistent review process from the initial screening of articles to the final selection of those included [48].

2.2. Search Strategy

We identified three key concepts from the research question, namely: “healthcare delivery”, “operational efficiency”, and “artificial intelligence”. Synonyms were also determined from these key concepts and fed into electronic databases using truncation and Boolean operators [49]. For example (“healthcare delivery” OR “healthcare services” AND “operational efficiency” OR “operations performance” AND “Artificial intelligence” OR “AI”). To enable an accurate search, we truncated words beginning with a standard stem, as databases contain references to articles that use both American and British spellings [49]. We conducted thorough checks to identify and correct any errors between Boolean operators that could have omitted or excluded relevant search results [49].

Additionally, some other relevant key terms were used to ensure a broader search scope and to accommodate potential spelling errors [49]. We selected these five databases because they contained high-quality, peer-reviewed literature relevant to the research question and objectives, with a focus on healthcare management. They include CINAHL Ultimate (EBSCO), Medline (EBSCO), Proquest Healthcare Management, Business Source Complete and PubMed. To ensure control of the entire process, complete search strategies, changes and hits were first documented in a notebook and then transferred to databases [49,50]. We initially tested the search strategy on Medline and then applied it to the other four databases. As this is a scoping review, the first 10 pages of Google Scholar were scanned for relevant articles using the key concepts to avoid their inadvertent exclusion. We excluded grey literature from this search process because the scope only included peer-reviewed articles. The search strategy is summarised below in Table 2. Note: “Search strategies were consistent across databases with minor syntax adjustments”

Table 2.

Search Strategies.

2.3. Selection Criteria

Papers eligible for inclusion were those related to the study’s research questions and objectives. The search focused on global healthcare environments, including hospitals and healthcare systems, that utilise AI innovations to enhance health services [51]. To ensure the information was current, we limited the search to publications from 2019 to 2024. We performed the search between 2 June 2025 and 4 June 2025; the included literature was limited to the five-year period of 2019–2024. These publications covered recent developments in healthcare AI, including its benefits, opportunities, and challenges, as well as ethical and regulatory issues. Due to time constraints regarding translation, only English-language articles were included. Both primary and secondary research studies were considered for selection because this is a scoping review; see the inclusion and exclusion criteria in Table 3. We screened the titles and abstracts to determine if they met the eligibility criteria [52].

Table 3.

Inclusion and Exclusion criteria.

2.4. Search Outcome

In this study, an initial search across five databases yielded a total of 4870 articles. Specifically, 1675 were from Medline, 1093 from CINAHL, 262 from Proquest Health Management, 934 from PUBMED, and 906 from Business Source Complete. After applying filters for full-text, a 10-year publication window, peer-reviewed status, and English language, the number of recovered publications was reduced to 519 and exported into EndNote. Of these, Medline contributed 90, CINAHL 127, Proquest Health Management 26, PUBMED 153, and Business Source Complete 123. Subsequently, we identified 196 duplicate articles and removed 205 that lacked sufficient relevance. This process resulted in 86 publications for full-text review. After a more detailed review against the eligibility criteria, we selected 13 publications for final inclusion and analysis in the review.

2.5. Data Extraction and Charting

Consistent with the scoping review’s objectives, data from the retrieved articles were charted logically, independently, and descriptively [52]. To visually display the key features of the 13 chosen articles, we developed a draft charting table [52]. The table comprised the following information: Author/Year of publication, Citation country, Setting, Aim/Objectives, Participants/Number of included publications, a summary of the methodology, and a summary of the findings.

2.6. Data Synthesis

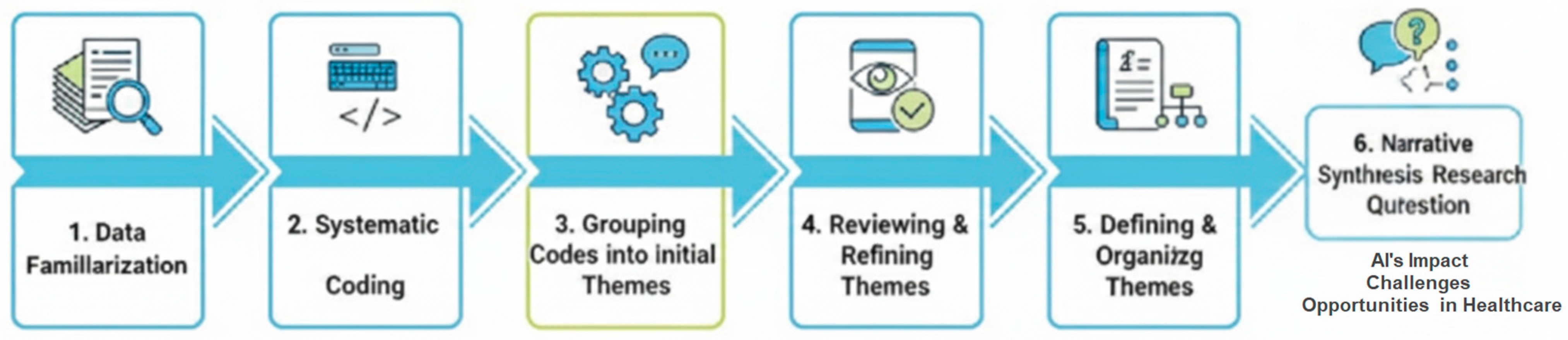

To synthesise the data, we used a thematic approach to map various aspects of the literature, aligning with the two research questions. We categorised the studies based on their design and methodology. Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, and Table 7 describe the critical appraisal framework (CASP), the Quality appraisal using the STROBE checklist, the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), and a summary of the included articles, respectively. These are then critically appraised and reviewed narratively to address the research questions. Figure 1 illustrates the systematic, multi-stage process used to synthesise the data from the 13 included articles. Adapting the process from standard thematic analysis guidelines, we mapped the evidence against the review’s research questions. The analysis began with data familiarisation from the 13 selected articles, followed by systematic coding of relevant information. We then grouped these codes to form initial themes, which we subsequently reviewed and refined against the dataset. Finally, the themes were defined and organised into a coherent narrative structure to address the research questions concerning AI’s impact, challenges, and opportunities in healthcare.

Figure 1.

Thematic Synthesis Process. A visual representation of the six-stage thematic process.

2.7. Quality Assessment

As noted earlier, a critical appraisal is often an optional component of a systematic scoping review [52]; however, it has been included here for several key reasons. Firstly, it adds rigour to the review process by enhancing the accuracy and credibility of the findings [53,54]. Secondly, it enables a more detailed examination of the conclusions of the diverse study designs in the included articles [53,55]. Ultimately, this study can inform future research in the rapidly evolving field of AI in healthcare by highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies [53].

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool was the primary instrument used to appraise most of the selected articles because it offers a wide range of assessment tools for various study designs and is user-friendly for new researchers [56]. The specific CASP checklists applied were:

- The qualitative studies checklist for seven articles, including case studies [57].

- The systematic reviews checklist for the three systematic reviews included [58].

- The cohort studies checklist for two publications identified as cohort studies [59].

Both the qualitative and systematic review checklists contain 10 questions across three main sections (A, B, and C) that cover essential aspects of research articles. The cohort studies checklist is similar but features 12 questions. Table 4a–c summarises the results of this quality assessment for qualitative, systematic review, and cohort studies, respectively. We then grouped these codes to form initial themes and subsequently reviewed and refined them against the dataset.

Table 4.

Critical appraisal framework-CASP.

Table 4.

Critical appraisal framework-CASP.

| (a) Qualitative Studies | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical appraisal criteria | Was there a clear statement of research aims | Is the methodology appropriate? | Was the research design appropriate for the objectives | Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the research aims? | Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | Has the relationship between the researcher and participant been considered? | Have ethical issues been considered | Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | Is there a clear statement of findings? | How valuable is the research? | Total score | ||||

| [60] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ||||

| [61] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 | ||||

| [62] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 | ||||

| [63] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 | ||||

| [64] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 10 | ||||

| [65] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 | ||||

| [66] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ||||

| [67] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 | ||||

| (b) Systematic Reviews | |||||||||||||||

| Critical appraisal criteria | Did the review address a clearly focused question | Did the authors look for the right papers | Were all essential relevant papers included? | Did the authors do enough to assess the quality of the included studies? | Was it reasonable to combine results | What are the overall results of the review? | How precise are the results? | Can the results be applied to the local population? | Were all important outcomes considered? | Are the benefits worth the harms and costs? | Score out of 10 | ||||

| [68] | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | Highlights the transformative potential of Healthcare 4.0 (H4.0) technologies and operational excellence tools for improving health services and operations. Furthermore, it advocates for their integration into healthcare organisations. | Although there is no statistical measurement of accuracy like confidence interval, this study appears to be quite precise as it provides a detailed comprehensive account with both bibliometric and cluster analysis. It recognises four clusters and propsoes managerial implications. | ✓ | X | ✓ | 8 | ||||

| [69] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A comprehensive evaluation of AI technologies and applications in Chinese EDs, focusing on resource optimisation, clinical decision support and patient monitoring. There is also the exploration of challenges and opportunities of integration | The results provide a detailed account of AI applications and design recommendations for Chinese EDs, thus somewhat precise. | X | ✓ | ✓ | 9 | ||||

| [70] | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | Provides an analysis of several opportunities and challenges of implementing AI technologies in healthcare | The results of this study appear to be precise, as the quality of the included studies was assessed using Kitchenham’s criteria. Results were also synthesised from empirical data which further may enhance precision. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 | ||||

| (c) Cohort Studies | |||||||||||||||

| Critical appraisal criteria | Did the study address a clearly focused issue | Was the cohort recruited acceptably? | Was the exposure accurately measured to minimise bias? | Was the outcome accurately measured to minimise bias? | Have the authors identified all important confounding factors? | Have they considered the confounding factors in the design and or analysis? | Was the follow up of the subjects complete enough? | Was the follow up of the subjects long enough? | What are the results? | How precise are the results? | Do you believe the results? | Can the results be applied to the local population? | Do the results of this study fit with other available evidence? | What are the implications for practice? | Score out of 14 |

| [71] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | The study revealed 29.02% of patients were readmitted and the best predictive model for pneumonia readmission was the regularised logistic regression(RegLR) | The study did not include a range of confidence intervals. However, it utilised cross validation, class imbalance handling, model selection and the area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) and other metrics like the positive and negative predictive values, sensitivity, specificity and F1 score to assess predictive models which could also indicate precision. | ✓ | X | ✓ | The study suggests that high risk patients can be identified with predictive models enabling targeted interventions to reduce readmission rates. This could improve hospital resource allocation and utimately health services. | 13 |

| [72] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | For predicting cardiopulmonary arrest, the pDEWS demonstrated exceptional performance surpassing conventional methods including the modified PEWS, random forest and logistic regression models with a higher AUROC of 0.923 and fewer false alarms. | The results are precise with narrow confidence intervals for AUROC and area under the precision-recall curve(AUPRC). This indicates reliability. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | The potential benefits of the integration of pDEWS into critical care could improve the early detection of critical cases, the efficiency of response teams and clinical outcomes. | 14 |

For the single publication using a quantitative methodology with correlation and structural equation modelling (SEM), the authors adapted the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) checklist for cross-sectional studies [73]. While not explicitly designed for SEM, this tool is widely accepted for reporting healthcare research that involves complex statistical methods and results.

Table 5 contains the sole quantitative study in this literature review, which showcases its high quality. The study’s design, including its variables and measurements, was explicitly detailed. Moreover, it employed suitable statistical tools and included reported validity and reliability tests. The authors transparently acknowledged the study’s limitations and generalisability. Overall, the study’s methodology is robust and its reporting is transparent, adhering to the STROBE checklist for cross-sectional observational research.

Table 5.

Quality appraisal- the STROBE checklist for observational studies (Cross-sectional studies).

Table 5.

Quality appraisal- the STROBE checklist for observational studies (Cross-sectional studies).

| Item No. | Appraisal | |

|---|---|---|

| TITLE AND ABSTRACT | 1. | (a) The title is clear and informative and indicates key variables, study population and type of analysis. (b) The abstract provides a well-balanced summary of the study. |

| INTRODUCTION | ||

| Background/rationale | 2. | The study’s background is clear and highlights the importance of healthcare information and performance in the context of Saudi Arabia. |

| Objectives | 3. | The objectives and hypotheses are specified and aim to address the impact of technology and innovation efforts on healthcare performance in Saudi Arabia. |

| METHODS | ||

| study design | 4. | The cross-sectional design is appropriate to the research question and is explicitly stated. |

| setting | 5. | The study setting, location and relevant dates (July 2021 and March 2022) are clearly described. |

| participants | 6. | The study includes senior healthcare practitioners from 241 organisations in Saudi Arabia, selected through emails and referrals. A simple random sampling technique was used to distribute questionnaires. |

| variables | 7. | The main variables (technology innovation, innovation efforts, and healthcare performance) are defined and translated into specific metrics that can be assessed through the survey instrument. |

| Data sources/measurements | 8. | A questionnaire was used as the data source and was descriptive in nature. |

| bias | 9. | Bias was not well addressed and was quite limited. |

| study size | 10. | The study provides some information on the sample size and the appropriateness of the chosen statistical method. However, there was no information on the reduced responses and power calculations. |

| quantitative variables | 11. | The quantitative variables were adequately handled. They seemed to be treated as continuous measures in the SEM analysis, which is well-suited to Likert-scale measurements. The article does not indicate any groupings made. |

| Statistical methods | 12. | (a) The study used the SEM analysis, particularly the partial least squares method (SMART PLS 3 programme), and correlation analysis. There was no mention of confounding controls. (b) There was no information on the examination of subgroups or interactions. (c) There was no explicit mention of how missing data were handled. (d) The simple random sampling technique was used to distribute questionnaires, but there was no mention of its use in the analysis. (e) There was no information on sensitivity analysis. |

| RESULTS | ||

| Participants | 13. | (a) The study did not address the number of participants at each stage. However, it does mention that 241 healthcare organisations were included. (b) The reason for non-participation was not documented. However, it did acknowledge that only 241 responses were received out of the 385 expected responses. (c) There was no flow diagram depicting the participant selection process. |

| Descriptive data | 14. | (a) The study provided demographic characteristics (age) of participants, but no details on clinical and or social characteristics. (b) There is no explicit information about the number of participants with missing data. |

| Outcome data | 15. | The summary did not report any specific summary measures like mean and median for the outcome variables. |

| Main results | 16. | (a) The study presents unadjusted estimates from the SEM but does not report confounder-adjusted estimates. (b) There was no reporting of category boundaries of the variables. (c) Not applicable. The results are not reported in terms of relative or absolute risk but as path weights and significance levels. |

| Other analysis | 17. | The study presents results from the SEM analysis and correlation analysis, but no additional analyses on subgroups. |

| DISCUSSION | ||

| Key results | 18. | (1) Technology innovation positively influenced healthcare performance (0.233 units increase) (2) Innovation efforts had a marked positive impact on technology innovation (0.739 units increase) and healthcare performance (0.338 units increase) (3) All 5 hypotheses were confirmed by the study. (4) Research and development, training, medical equipment acquisition and software acquisition were revealed to play a critical role in technology innovation, innovation efforts and healthcare service delivery. (5) Technology innovations like AI, telemedicine, mobile technology, digitalisation of health records had positive effects on healthcare performance. (6) The findings supported the resource-based view theory demonstrating that tangible and intangible resources are necessary for an organisation’s performance. These findings support the study objectives and provide empirical evidence for the positive relationship between technology innovation, innovation efforts and health services in Saudi Arabia. |

| Limitations | 19. | (1) The geographical focus of the study on Saudi Arabia may limit the generalisability of this research to other healthcare systems. (2) The sample size could potentially introduce bias, as results could be under or overestimated. The authors admit that the sample size could be larger. (3) The study’s cross-sectional design offers insights at a point in time rather than an extended period. The need for more diverse, longitudinal studies was suggested by the authors to understand trends over time. (4) Some core health technologies (e.g., surgical and drug innovations) were not included in the scope of research. |

| Interpretation | 20. | Although the results are in line with the resource-based view theory and some previous studies, applying the results of this study to practice would require caution. Additional studies, particularly longitudinal studies would strengthen the conclusions and applicability to other healthcare systems. |

| Generalisability | 21. | Within the scope and parameters of the study design, the study attempts to address external validity. However, it does not explore extensively all potential limitations to generalisability. |

| OTHER INFORMATION | ||

| Funding | 22. | The role of funders in not applicable in this study as the study explicitly states it received no external funding. |

2.8. Inter-Rater Reliability

To determine Inter-Rater Reliability [Table 6], we dual-rated 13 included articles. The second researcher applied the same CASP checklist to the selected studies. The results were statistically analysed using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) to compare the total scores made by the two raters for the selected studies.

Table 6.

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient.

Table 6.

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient.

| Intraclass Correlation b | 95% Confidence Interval | Value | F Test with | True Value 0 | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | df1 | df2 | ||||

| Single Measures | 0.947 a | 0.742 | 0.985 | 54.200 | 12 | 12 | <0.001 |

| Average Measures | 0.973 c | 0.852 | 0.993 | 54.200 | 12 | 12 | <0.001 |

Superscripts “a”, “b”, and “c” denote the ICC calculation details: ‘a’ and ‘c’ specify the statistical model (two-way mixed effects) for Single and Average Measures, respectively. ‘b’ indicates the specific type of ICC (absolute agreement) being reported in Table 6.

The ICC values are very high, suggesting excellent reliability. Single Measures (ICC = 0.947a): This value represents the estimated reliability of a single rater’s or measure’s score. A value of 0.947 is exceptionally high, indicating that the agreement among individual measurements is excellent. Average Measures (ICC = 0.973c): The average of all raters’ scores represent the estimated reliability. A value of 0.973 is even higher, indicating that the reliability of the average score from the set of measurements is outstanding. Using the average of the measurements substantially increases the overall reliability. The 95% CI provides a range within which the actual population ICC is likely to fall. Single Measures: The CI is [0.742, 0.985]. Average Measures: The CI is [0.852, 0.993]. Both intervals are well above zero and include high values, further supporting the conclusion of strong reliability. The lower bound of the Average Measures CI (0.852) is particularly high (in the “Good to Excellent” range), suggesting that even the lowest likely estimate of the true reliability is excellent. The narrowness of the intervals (especially for Average Measures) suggests a relatively precise estimate of the reliability. The ICC analysis indicates excellent inter-rater or test–retest reliability. The F-Test (Value = 54.200) checks if the reliability (ICC) is statistically different from zero (no reliability). The degrees of freedom, df1 (12) (related to subjects) and df2 (12) (related to error variance), confirm this high F-value is significant (Sig. < 0.001), meaning the observed reliability is not due to chance. Both the single-measure and average-measure ICCs are very high (0.947 and 0.973, respectively); the 95% confidence intervals are narrow and high, indicating that the reliability is statistically significant (p < 0.001), which suggests that the ratings are highly consistent and reliable.

3. Results

This chapter presents the results of the scoping review, detailing the search outcomes, characteristics of the included studies, and a synthesis of the evidence mapped across the review objectives.

3.1. Search Results and Study Selection

In this review, we analysed 13 articles. Figure 2 illustrates the inclusion process for these studies, while Table 3 offers detailed descriptions of each. Eight of the articles were empirical research studies [60,62,64,65,66,67,71,72], while the remaining five were non-empirical, comprising two narrative reviews [61,63] and three systematic reviews [68,69,70]. The majority of these studies were conducted in Asia, with five studies coming from Vietnam, Malaysia, the Philippines, South Korea, and India [62,63,68,71,72]. Europe was the second most represented region, with four publications: three from the UK [61,64,69] and one from Sweden [64]. The other studies were from various parts of the world, including two from the United States [60,66], one from Ethiopia in Africa [70], and one from Saudi Arabia in the Middle East [67]. This global spread underscores the widespread interest in utilising AI to enhance health service provision. This trend suggests a growing emphasis on utilising technology to improve patient outcomes in healthcare systems worldwide.

Figure 2.

Prisma Flow chart [47].

3.2. Study Characteristics

Following this scoping review’s objectives, a summary of the included articles is included below [Table 7]. We will discuss AI’s current impact on operational efficiency and patient outcomes, as well as the key challenges and future opportunities for its implementation in healthcare (In line with the objectives of this scoping review, the current impact of AI integration on operational efficiency and patient outcomes, alongside the key challenges and future opportunities associated with healthcare implementation, are discussed below).

Table 7.

Summary of Included Articles.

Table 7.

Summary of Included Articles.

| Author, Year | Region, Setting | Primary Objective | Methodology Type | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [60] | USA, Healthcare Industry | Trends, Potential, and Barriers of AI in Medicine. | Qualitative (Thematic Analysis of symposium) | Integration barriers include data privacy, bias, and process issues; physician experience is key. |

| [61] | UK, Public Health System | Explore AI solutions for patient inflow issues in mental health. | Narrative Literature Review & Qualitative (Interviews) | AI can enhance workflow efficiency, workforce planning, and demand prediction. |

| [62] | Vietnam, Private & Public Hospitals | Discover the advantages of big data analytics in addressing operational challenges. | Qualitative (Case Study Approach) | Big data has led to enhanced resource allocation and utilisation, as well as improved patient care. |

| [63] | Malaysia, Hospital setting | Determine the benefits and challenges of AI in care delivery. | Narrative Literature Review | The benefits of AI outweigh the negative implications, with significant opportunities existing. |

| [68] | India/Europe, Diverse Healthcare Settings | Analyse the relationship between operational efficiency and Healthcare 4.0 (AI/big data). | Systematic Literature Review (Bibliometric Analysis) | AI integration has the potential to transform patient outcomes and workflow. |

| [71] | Philippines, Public Tertiary Hospital | Evaluate the effectiveness of predictive models for pneumonia readmission. | Retrospective Observational Cohort (Quantitative) | Predictive models significantly reduced patient readmission rates (demonstrating AI insight). |

| [64] | UK, Public Health System (NHS) | Examine the barriers and factors that influence the adoption of AI in the NHS. | Qualitative (Thematic Analysis of interviews) | Identified barriers like IT infrastructure issues and unclear AI language; suggested solutions like training. |

| [65] | Sweden, Healthcare Organisations | Explore healthcare leaders’ perceptions on AI implementation. | Qualitative (CFIR-based interviews) | Leaders saw benefits (early diagnosis, decision support) but expressed concerns over data security, transparency, and high cost. |

| [69] | China, Emergency Departments (ED) | Explore integration of AI with ED facilities design (opportunities/challenges). | Systematic Literature Review | AI can optimise ED efficiency and improve patient outcomes, but challenges such as data privacy and high costs exist. |

| [70] | Ethiopia, Diverse Healthcare Settings | Synthesise empirical studies on AI adoption challenges and opportunities. | Systematic Literature Review | AI has the potential to transform healthcare, but it must address ethical and privacy issues. |

| [67] | Saudi Arabia, Healthcare Organisations | Assess the nature of technology innovation and its effects on healthcare performance. | Quantitative (Correlation/SEM, Cross-sectional) | Found a strong positive correlation between technological innovation (AI) and healthcare performance. |

| [66] | USA, Non-profit Healthcare Organisation | Showcase how AI implementation can improve patient outcomes. | Case Study Report (Qualitative & Quantitative) | Showed markedly improved patient management using AI innovations like big data analytics. |

| [72] | South Korea, Tertiary Care Hospital | Develop and evaluate a deep learning-based paediatric early warning system (pDEWS). | Retrospective Observational Cohort (Quantitative) | The pDEWS outperformed existing tools (PEWS) and improved operational efficiencies and clinical outcomes. |

3.3. Quality Appraisal Summary

This scoping review incorporated a critical appraisal to enhance the rigour, accuracy, and credibility of the findings, allowing for a detailed scrutiny of diverse study designs in the rapidly evolving field of AI in healthcare. This appraisal also helps inform future research by highlighting methodological strengths and weaknesses. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool was the primary instrument used due to its comprehensive range of checklists for various study designs and its user-friendly nature. We applied specific CASP checklists to the included articles: the qualitative studies checklist (10 questions) to seven articles, the systematic reviews checklist (10 questions) to three reviews, and the cohort studies checklist (12 questions) to two publications (Table 4a–c). To ensure consistency in the appraisal process, Inter-Rater Reliability was assessed by dual-rating 13 selected articles using the identical CASP checklists. The results were statistically analysed using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) to compare the total scores from the two raters. The ICC analysis indicated excellent reliability. The Single-Measures ICC was 0.947, indicating extremely high agreement among individual ratings. The Average Measures ICC was even higher at 0.973, confirming that using the average of raters’ scores substantially increases overall reliability. The 95% confidence intervals (e.g., [0.852, 0.993] for Average Measures) were high and tight, further supporting the conclusion of strong, statistically significant consistency (p < 0.001) in the ratings.

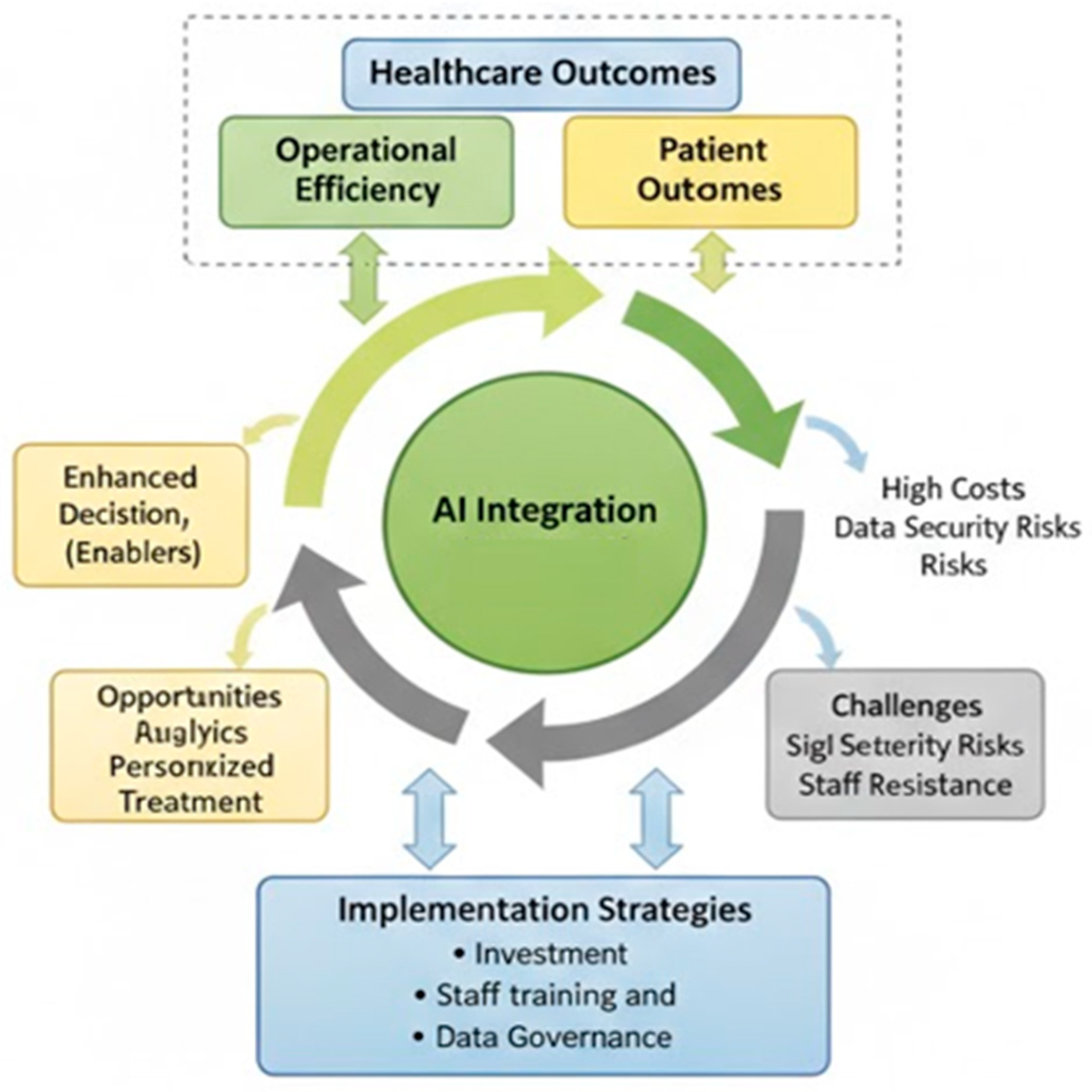

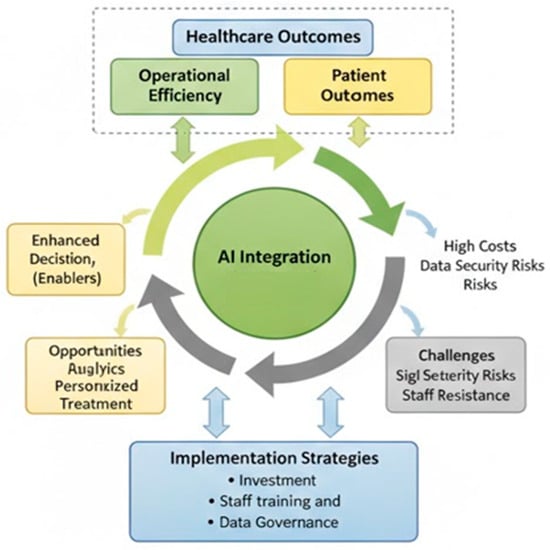

3.4. Conceptual Framework Showing Theme Relationships

This conceptual framework shows the relationship between the core themes identified in the scoping review. It positions AI Integration as the central element, which influences Healthcare Outcomes. A series of Opportunities (enablers) and Challenges (barriers) moderate this relationship; targeted Implementation Strategies can address them. Figure 3 presents a conceptual framework illustrating the dynamics of AI implementation in healthcare. The integration of AI directly impacts Operational Efficiency and Patient Outcomes. Opportunities, such as enhanced decision-making and predictive analytics, positively influence this impact, but challenges, including high costs, data security risks, and staff resistance, constrain it. The framework proposes that strategic interventions—including investment, staff training, and robust data governance can mitigate these challenges and amplify the opportunities, thereby maximising the positive outcomes of AI integration.

Figure 3.

Conceptual Framework of AI Integration in Healthcare.

3.5. AI Impact on Operational Efficiency and Patient Outcomes [RQ1]

Evidence from six studies suggests that technological innovations, such as AI, have a significant and positive impact on operational efficiency and patient outcomes in healthcare [62,63,66,67,68,71]. These studies show that healthcare organisations that adopt innovations such as AI and big data analytics become more patient-centric. They are better at predicting patient demands and can improve patient experiences and satisfaction. Additionally, these organisations can optimise resource allocation, proactively solving problems and increasing efficiency.

The Mission Control Centre, an AI-powered system used by Chi Franciscan Hospitals, leveraged real-time data from its 1300-bed network [66]. Within a year, it facilitated timely physician interventions in 142 critical cases, which reduced patient waiting times and mortality. The system also detected delays in care activities, enhancing patient safety. It improved patient management by creating the Physician on Duty (PoD) program, which brought together a diverse team of experts, ultimately improving patient outcomes. From an operational standpoint, the system’s unique algorithm was 98% accurate in predicting patient demand at tertiary sites, yielding a significant 12:1 return on investment (ROI), equivalent to a staggering 1100% increase. The system also reduced lost cases by 20% and patient onboarding time by 54%. The PoD program accounted for 74% of its total labour cost. Overall, the system enhanced patient care, capacity management, and resource allocation at Chi Franciscan Hospitals.

Similarly, three hospitals in Vietnam successfully used AI applications to improve their big data capabilities within a year [62]. FV hospitals reduced outpatient wait times by 52% using predictive modelling, Vinmec Hospital networks increased bed utilisation by 12% through data-driven bed allocation, and Da Nang Hospital cut inventory by 11% while reducing stock outputs by 60%. These examples demonstrate how complex healthcare systems can achieve a significant ROI for both patients and themselves by effectively implementing AI [62,66]. The findings suggest that AI is a core component of big data analytics, enhancing workflow operations, resource management, and patient outcomes [62].

Another study found that the regularised logistic regression (RegLR) model, a machine learning approach, was superior at predicting pneumonia readmission rates in public hospitals in the Philippines [71]. By selecting key predictors among adult and elderly patients, the model could identify those at the highest risk of illness and readmission, which enabled the hospital to improve patient care by minimising costs and effectively allocating resources using an AI subset [71].

These case studies provide concrete evidence of how AI, by utilising real-world healthcare data, positively impacts patient outcomes and operational efficiency, thereby directly linking technological innovations to enhanced care delivery [62,66,71].

Technological innovations, such as AI, are considered intangible resources that can significantly influence a healthcare organisation’s performance [67]. Their research shows a direct positive correlation between healthcare performance (HP), innovative efforts (IE), efforts indirectly enhance healthcare performance.

The integration of Healthcare 4.0 technologies, such as AI, with operational excellence methods is considered crucial for achieving operational excellence in healthcare [68]. The authors suggest that healthcare organisations that adopt AI-augmented workflow processes, combined with business operational tools such as lean Six Sigma, root cause analysis, and value stream mapping, are successful in improving health service delivery [68].

Another study revealed that AI and its subfields have improved nearly every aspect of healthcare, including clinical decision-making, patient safety, and healthcare administration [63]. The authors suggested that while AI already has a positive impact on health service provision, it also holds immense potential despite its challenges.

Conversely, some studies found no current impact of AI innovations on operational efficiency and patient outcomes [60,61,64,65,69,70,72].

3.6. Implementation Challenges and Potential Opportunities [RQ2]

The preceding case studies demonstrate AI’s current positive influence on workflow processes and patient outcomes. While future implementation offers significant benefits, healthcare organisations also face considerable challenges. Table 8 outlines the potential advantages and the issues that complicate their integration.

Table 8.

Potential Opportunities and Challenges of Implementing Healthcare AI.

4. Discussion and Recommendations

This scoping review identified 13 studies examining AI implementation in healthcare. Our analysis reveals a paradox: while case studies demonstrate clear operational benefits, the systematic implementation of these benefits remains limited. This scoping review aimed to map the existing literature on the integration of AI into healthcare, focusing on its impact on operational efficiency and patient outcomes from a managerial perspective. The findings confirm that AI presents a revolutionary opportunity for healthcare organisations striving to deliver high-quality care amidst resource constraints. However, the composition and nature of the available evidence reveal critical insights into the field’s maturity and the complex path from technological promise to widespread practical implementation.

A striking finding of this review is the imbalance in the evidence base: of the 13 included articles, only eight were empirical research, including just three detailed case studies demonstrating tangible outcomes [62,66,71]. The remaining five were non-empirical [61,63] or systematic reviews [68,69,70], focusing on potential, perceptions, and barriers. This composition strongly suggests that the field of AI in healthcare administration is in a nascent, preparatory stage. The literature was dominated by “sense-making” activities—defining challenges, mapping opportunities, and consolidating existing knowledge—rather than reporting on mature, scaled implementations. The literature aligns with the observation that, despite significant investment, successful, long-term AI implementations in healthcare remain limited.

AI implementation raises a crucial question: how can the profound successes reported in the case studies be reconciled with the broader narrative of limited adoption? The studies from Chi Franciscan Hospitals [66], Vietnamese hospitals [62], and the Philippines [71] should be viewed as “pockets of excellence.” They are proofs of concept that demonstrate what is possible when AI is applied to specific, well-defined problems, such as patient flow, bed utilisation, and readmission risk prediction. However, these successes often occur in controlled environments with significant investment and targeted expertise. The challenges identified in the literature—high costs, data fragmentation, lack of interoperability, and staff resistance (Table 8)—represent systemic barriers that prevent these isolated successes from being easily scaled or replicated across different healthcare systems. Therefore, the evidence does not present a contradiction but rather two sides of the same coin: AI’s potential is demonstrably high, but the organisational and systemic hurdles to realising that potential at scale are formidable.

Three of the included articles were themselves systematic reviews: [61,69,70]. The findings of this scoping review align closely with theirs, confirming a consensus on the primary benefits (e.g., enhanced decision-making, predictive capabilities) and challenges (e.g., data security, cost, ethical issues) of AI in healthcare (Table 8). For instance, both our review and the systematic reviews corroborate the transformative potential of AI integration to improve patient outcomes and workflow efficiency [68,69]. Furthermore, the pervasive concerns regarding ethical and privacy issues are consistently highlighted as a significant barrier, as synthesised by [70] and echoed across our included qualitative studies [60,65]. Our review adds value by providing a granular, cross-study synthesis of both the realised impact (from empirical studies) and the systemic barriers (from qualitative studies and other reviews) within a single, unified conceptual framework (Figure 3), explicitly designed to guide managerial strategy.

The unique contribution of this scoping review lies in its specific focus on the administrative and managerial lens, providing a strategic overview explicitly for healthcare leaders and decision-makers. “Healthcare 4.0” and operational excellence focus on the niche area of emergency departments, our synthesis is broader and more strategic [66,68]. We synthesise evidence from diverse global settings spanning Asia, Europe, and Africa (Section 3.1) and cover a wide range of operational impacts (e.g., bed utilisation, inventory, wait times, readmission rates) that are critical to a healthcare manager’s mandate (Section 3.5). By synthesising this evidence, this review frames the findings to answer the question: “Given the current state of evidence, how should a healthcare organisation strategically approach AI adoption?” The resultant conceptual framework (Figure 3), which identifies targeted Implementation Strategies to mitigate Challenges and amplify Opportunities, is a key differentiator that translates fragmented evidence into an actionable blueprint for leadership, a step beyond the general landscape mapping offered by the included systematic reviews.

The included literature provides an opportunity to move beyond a simplistic view of AI as merely a new tool. While the Resource-Based View (RBV), as noted by Akinwale & AboAlsamh in their study, correctly identifies technological innovations like AI as crucial intangible resources for competitive advantage, it does not fully explain the implementation difficulties. Integrating other theoretical frameworks helps us better understand the gap between AI’s potential and its current adoption reality. First, the Diffusion of Innovations theory helps explain the slow rate of adoption. The “black box” nature of some AI systems reduces their observability and increases their perceived complexity [10,46,67]. Issues with integrating AI into existing IT infrastructure highlight compatibility challenges. Morrison explored in his study that these factors are classic barriers to the diffusion of new technologies. Second—and perhaps most importantly—a sociotechnical systems perspective is essential. The success of the Chi Franciscan “Mission Control Centre” [66] was not just due to a good algorithm, but also to its integration with a diverse team of experts, specifically the Physician on Duty (PoD) program, which demonstrated a successful alignment of technology and human processes. The challenges cited are rarely purely technical. They involve a profound interplay between technology (the AI algorithm) and the social system (people, workflows, culture). Staff resistance stemming from a limited understanding of AI [70], the need for robust data governance frameworks to ensure privacy, and the necessity of new training programs are all sociotechnical issues.

Practical Implications and Recommendations

For healthcare managers and policymakers, the evidence suggests a strategic, phased, and human-centred approach to AI adoption. Healthcare managers must strategically approach AI adoption to ensure a successful and ethical implementation of this technology. Managers should start with targeted pilot projects; instead of attempting a large-scale overhaul, they must identify specific, high-impact problems where AI proves effective, such as reducing patient wait times, optimising bed allocation, or predicting readmission for conditions like pneumonia. Success in these initial areas builds institutional momentum and demonstrates a clear return on investment. Furthermore, managers must invest in people and processes, not just technology, by allocating significant resources within implementation budgets for comprehensive staff training, which demystifies AI and builds trust. Leaders should champion a data-driven culture and co-design new workflows with clinical and administrative staff to ensure AI tools support, rather than disrupt, their daily work. Finally, managers must establish robust data governance. Before implementing advanced analytics, they must create clear policies and technical infrastructure that ensure data quality, security, and privacy, which form a foundational prerequisite for any successful and ethical AI rollout.

National bodies must establish and enforce interoperability standards to enable the secure sharing of information required to train and validate effective AI models, thereby solving the significant barrier of fragmented data systems that individual hospitals cannot address alone. Furthermore, governments and professional bodies should collaborate to develop clear ethical and regulatory frameworks that define AI accountability, transparency, and bias mitigation, which is essential for overcoming the current regulatory ambiguity, ensuring patient safety, and building public trust.

It is crucial to recognise that the evidence base is heavily concentrated in high-income countries (the USA, UK, Sweden) and technologically advanced settings in Asia (South Korea, Vietnam, the Philippines). The findings from these regions, which often have more developed digital infrastructures and resources for investment, may not be directly generalisable to low- and middle-income countries or other resource-constrained settings. While studies from the Philippines and Vietnam demonstrate how AI can be tailored to address the challenges of developing nations, there is an apparent lack of empirical research from regions such as Africa and South America. Future research should explore the implementation of AI in these diverse contexts to develop strategies that are both globally relevant and equitable.

5. Conclusions

The healthcare industry is undergoing a significant transformation due to the integration of new technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI) and big data analytics. With healthcare organisations focused on delivering top-notch care despite limited resources, AI presents a revolutionary opportunity. Its influence is already apparent across all facets of healthcare, from optimising processes and improving clinical care to managing resources and stimulating new ideas. AI and healthcare are deeply linked, as the healthcare sector generates vast amounts of data, which necessitates efficient and automated methods for analysing data to control expenses and manage staff workload. Although extensive research confirms AI’s positive effects on clinical care and its broad potential, it also highlights significant obstacles that could impede its effective integration into healthcare systems.

This study examined how AI improves service provision from the viewpoint of an administrator. A thorough analysis of the included case studies provides concrete evidence of AI’s tangible impact on patient outcomes and operational efficiency. Despite a limited number of case studies, the implementation of AI and big data analytics in three different healthcare environments demonstrated remarkable improvements in patient outcomes and operational metrics through precise treatment and case management, as well as efficient resource allocation. The reviewed articles proposed that AI’s potential applications go beyond medicine to other areas of healthcare, including non-clinical decision-making, improved healthcare access, performance, innovation, and patient empowerment. These potential advantages could substantially boost the efficiency of healthcare systems.

However, it is essential to address critical challenges, such as data-related issues (including security, privacy, and quality), ethical concerns, high costs, staff resistance, fragmented healthcare systems, and the operational complexities of AI and big data. To ensure successful implementation, it is crucial to prioritise investments in training and infrastructure, promote interdisciplinary collaboration, and advocate for sensible policies and regulations. Healthcare managers must develop the necessary skills to oversee data-driven healthcare systems effectively. By embracing innovations like AI and big data analytics, managers can set an example for their staff, demonstrating how to adapt to modern healthcare while continuing to deliver high-quality care.

6. Limitations

The findings of this scoping review should be interpreted in light of several limitations that affect the generalizability and comprehensiveness of the results. These can be categorised into methodological constraints, the nature of the available evidence, and temporal factors.

6.1. Methodological Limitations

- Protocol Preregistration: The lack of a pre-registered protocol increases the potential for reporting bias and reduces transparency in the review process.

- Database Coverage: We excluded key databases relevant to technological innovation—such as Scopus, IEEE Xplore, and the ACM Digital Library—from the search, which was confined to five databases specific to healthcare and management. This decision may have resulted in the omission of pertinent technical and interdisciplinary studies.

- Publication and Language Bias: Excluding grey literature, such as government reports and unpublished dissertations, we restricted the search only to peer-reviewed, English-language articles. This strategy likely introduced publication bias by favouring the publication of studies with statistically significant or positive findings, which could overstate the benefits of AI.

6.2. Limitations of the Evidence Base

- Limited Empirical Evidence: Although the review identified several articles discussing the potential of AI, it included only three empirical case studies that provided concrete evidence of its current impact on operational efficiency and patient outcomes. This small evidence base makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions.

- Geographic Concentration: The geographic concentration of included studies, predominantly in Asia and Europe, limits the applicability of the findings to healthcare systems in regions such as North America, Africa, and Latin America, which face different contextual challenges.

- Lack of Cost-Effectiveness Data: A significant gap in the literature was the absence of detailed cost-effectiveness or cost–benefit analyses. While one study reported a high return on investment, the broader economic implications and viability of implementing and scaling AI systems in diverse healthcare settings remain largely unexamined.

- Absence of Patient Perspectives: The reviewed literature primarily focused on administrative and clinical viewpoints. There was a notable lack of studies investigating the patient perspective, including their experiences, acceptance, and concerns regarding AI-driven healthcare.

6.3. Temporal Limitations

- Rapid Evolution of AI: Artificial intelligence is a rapidly advancing field. Given that the review covers literature from the past 5 years, some of the technologies and findings discussed may already be outdated or superseded by more advanced innovations.

- Limited Longitudinal Data: Cross-sectional or short-term observational studies dominate the evidence base. Researchers rarely conduct longitudinal studies that track the long-term effects of AI integration on patient outcomes, organisational performance, and workforce dynamics over several years.

7. Future Research

This paper summarises the current research on the contribution of artificial intelligence (AI) to improving healthcare services. It highlighted the potential opportunities and challenges of introducing AI into healthcare systems and organisations; however, there was a significant absence of research on AI’s present effects on operational efficiency and patient outcomes from an administrative viewpoint. This gap is significant because healthcare administrators, managers, and leaders are the primary determinants of a healthcare organisation’s overall effectiveness and efficiency. Filling this gap could reveal potential new ways to improve patient outcomes, manage resources, and enhance service provision. Future research could focus on long-term studies examining the impact of AI innovations on patient outcomes, as well as cost–benefit analyses of implementing them in various healthcare settings.

Additionally, it could examine the potential role of AI technologies in coordinating and managing the workforce. A comprehensive investigation of this research gap will need cooperation among various disciplines, including software developers, IT staff, healthcare managers, leaders, researchers, and policymakers, to ensure that the interventions are not only innovative but also realistic and ethical. The valuable insights provided by future studies in these fields could fundamentally transform healthcare administration, leading to healthcare systems that are more efficient, cost-effective, and patient-centred.

Author Contributions

E.M.A.: Conceptualised the review framework, led design of the methodology (in line with JBI/Arksey and Malley frameworks), drafted sections of the manuscript, contributed substantially to the review and editing process, and shared in the overall project supervision. V.C.O.: Provided supporting conceptualisation, the formal methodology design, data curation and mapping activities and drafted sections of the manuscript, contributed substantially to the review and editing process, and shared in the overall project supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that they used no funding sources for this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results in the included studies are listed in Table 7.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Henfridsson, O.; Bygstad, B. The Generative Mechanisms of Digital Infrastructure Evolution. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 907–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, K.; Mathiassen, L.; Holmström, J. Representation and Mediation in Digitalized Work: Evidence from Maintenance of Mining Machinery. J. Inf. Technol. 2018, 33, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, L.; Dendere, R.; Eden, R.; Grantham, B.; Krivit, J.; Pearce, A.; McNeil, K.; Green, D.; Sullivan, C. Perceived Impact of Digital Health Maturity on Patient Experience, Population Health, Health Care Costs, and Provider Experience: Mixed Methods Case Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e45868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davenport, T.H. The AI Advantage: How to Put the Artificial Intelligence Revolution to Work; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hinings, B.; Gegenhuber, T.; Greenwood, R. Digital Innovation and Transformation: An Institutional Perspective. Inf. Organ. 2018, 28, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, C.D. On the Prospects for a (Deep) Learning Health Care System. JAMA 2018, 320, 1099–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönberger, D. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: A Critical Analysis of the Legal and Ethical Implications. Int. J. Law Inf. Technol. 2019, 27, 171–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secinaro, S.; Calandra, D.; Secinaro, A.; Muthurangu, V.; Biancone, P. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: A Structured Literature Review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Decary, M. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: An Essential Guide for Health Leaders. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2019, 33, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.; Shakyawar, S.K.; Sharma, M.; Kaushik, S. Big Data in Healthcare: Management, Analysis and Future Prospects. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, R. Emerging Health Technologies and How They Can Transform Healthcare Delivery. J. Health Manag. 2021, 23, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, H.C. Improving Healthcare Cost, Quality, and Access Through Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications. J. Healthc. Manag. 2021, 66, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekbolatova, M.; Mayer, J.; Ong, C.W.; Toma, M. Transformative Potential of AI in Healthcare: Definitions, Applications, and Navigating the Ethical Landscape and Public Perspectives. Healthcare 2024, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, S.; Fox, J.; Purohit, M.P. Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Healthcare Delivery. J. R. Soc. Med. 2018, 112, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, J.M.; Swiergosz, A.M.; Haeberle, H.S.; Karnuta, J.M.; Schaffer, J.L.; Krebs, V.E.; Spitzer, A.I.; Ramkumar, P.N. Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence: Definitions, Applications, and Future Directions. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2020, 13, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirani, R.; Noruzi, K.; Khuram, H.; Hussaini, A.S.; Aifuwa, E.I.; Ely, K.E.; Lewis, J.M.; Gabr, A.E.; Smiley, A.; Tiwari, R.K.; et al. Artificial Intelligence and Healthcare: A Journey Through History, Present Innovations, and Future Possibilities. Life 2024, 14, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpurkar, P.; Chen, E.; Banerjee, O.; Topol, E.J. AI in Health and Medicine. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzidia, S.; Makaoui, N.; Bentahar, O. The Impact of Big Data Analytics and Artificial Intelligence on Green Supply Chain Process Integration and Hospital Environmental Performance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 165, 120557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.J.; Karthikesalingam, A.; Suleyman, M.; Corrado, G.; King, D. Key Challenges for Delivering Clinical Impact with Artificial Intelligence. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluge, E.H. The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: From Hands-On Care to Policy-Making. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2024, 37, 406–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.N.; Lee, D. Artificial Intelligence and Robots in Healthcare: What Are the Success Factors for Technology-Based Service Encounters? Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2019, 12, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, M.J. Ethical Dimensions of Using Artificial Intelligence in Health Care. AMA J. Ethics 2019, 21, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Yoon, S.N. Application of Artificial Intelligence-Based Technologies in the Healthcare Industry: Opportunities and Challenges. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randell, R.; Honey, S.; Alvarado, N.; Greenhalgh, J.; Hindmarsh, J.; Pearman, A.; Jayne, D.; Gardner, P.; Gill, A.; Kotze, A.; et al. Factors Supporting and Constraining the Implementation of Robot-Assisted Surgery: A Realist Interview Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bini, S. Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, Deep Learning, and Cognitive Computing: What Do These Terms Mean and How Will They Impact Health Care? J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 2358–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicuonzo, G.; Donofrio, F.; Fusco, A.; Shini, M. Healthcare System: Moving Forward with Artificial Intelligence. Technovation 2023, 120, 102510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J.H.; Elliott, T.E.; Brown, J.S.; Raebel, M.A.; Davidson, A.; Nelson, A.F.; Chung, A.; La Chance, P.; Steiner, J.F. Clinical Research Data Warehouse Governance for Distributed Research Networks in the USA: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2014, 21, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheny, M.E.; Whicher, D.; Thadaney Israni, S. Artificial Intelligence in Health Care: A Report from the National Academy of Medicine. JAMA 2020, 323, 509–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazu, M.H.; Jahan, S.A. Big Data Analytics & Artificial Intelligence in Management of Healthcare: Impacts and Current State. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 14, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, T.M.D.; Sinsky, C.M.D. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014, 12, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topol, E.J. High-Performance Medicine: The Convergence of Human and Artificial Intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Zhi, H.; Dong, Y.; Li, H.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Q.; Shen, H.; Wang, Y. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Past, Present and Future. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 2017, 2, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.L. The Perils of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Disease Diagnosis and Treatment. J. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. Res. 2019, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, E.; Bagci, U. The Past, Current, and Future of Neonatal Intensive Care Units with Artificial Intelligence: A Systematic Review. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, X.; Wang, M.; Shen, H. What Influences Patients’ Continuance Intention to Use AI-Powered Service Robots at Hospitals? The Role of Individual Characteristics. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 101996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiwerioghene, E.M.; Lewis, J.; Rea, D. Maturity Models for Hospital Management: A Literature Review. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2024, 18, 902–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, G.W.; Tushman, M.L.; Kapadia, S.R. Operational Efficiency and Effective Management in the Catheterization Laboratory: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2507–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebcir, R.; Hill, T.; Atun, R.; Cubric, M. Stakeholders’ Views on the Organisational Factors Affecting Application of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: A Scoping Review Protocol. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panch, T.; Szolovits, P.; Atun, R. Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and Health Systems. J. Glob. Health 2018, 8, 020303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkmann, M.; Schildt, H. Open Data Partnerships Between Firms and Universities: The Role of Boundary Organizations. Res. Policy 2015, 44, 1133–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharwood, L.N. AI Use for Injury Surveillance in Emergency Departments. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2524162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, I.D. What Is a “Mapping Study?”. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2016, 104, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing Between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthew, J.P.; Joanne, E.M.; Patrick, M.B.; Isabelle, B.; Tammy, C.H.; Cynthia, D.M.; Larissa, S.; Jennifer, M.T.; Elie, A.A.; Sue, E.B.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A.P.; Moher, D.; Page, M.J.; Koffel, J.B.; Blunt, H.; Brigham, T.; Chang, S.; et al. PRISMA-S: An Extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramer, W.A.-O.; de Jonge, G.B.; Rethlefsen, M.A.-O.; Mast, F.; Kleijnen, J. A Systematic Approach to Searching: An Efficient and Complete Method to Develop Literature Searches. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2018, 106, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sara Efrat, E.; Ruth, R. Writing the Literature Review: A Practical Guide; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, J.; Rudzicz, F.; Jamieson, T.; Goldfarb, A. Artificial Intelligence and the Implementation Challenge. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2021, 19, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.; Sutton, A.; Papaioannou, D. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, D. Weight of Evidence: A Framework for the Appraisal of the Quality and Relevance of Evidence. Res. Pap. Educ. 2007, 22, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowkes, F.G.; Fulton, P.M. Critical Appraisal of Published Research: Introductory Guidelines. BMJ 1991, 302, 1136–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.A.; French, D.P.; Brooks, J.M. Optimising the Value of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Tool for Quality Appraisal in Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Res. Methods Med. Health Sci. 2020, 1, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP (Qualitative Studies) Checklist. 2018. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/qualitative-studies-checklist/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP (Systematic Reviews) Checklist. 2018. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/systematic-review-checklist/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP (Cohort Studies) Checklist. 2018. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/cohort-study-checklist/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Borgstadt, J.T.; Kalpas, E.A.; Pond, H.M. A Qualitative Thematic Analysis of Addressing the Why: An Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Healthcare Symposium. Cureus 2022, 14, e23704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawoodbhoy, F.M.; Delaney, J.; Cecula, P.; Yu, J.; Peacock, I.; Tan, J.; Cox, B. AI in Patient Flow: Applications of Artificial Intelligence to Improve Patient Flow in NHS Acute Mental Health Inpatient Units. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Aoun, M. Improving Hospital Operations and Resource Management in Vietnam Through Big Data Analytics. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Sci. 2022, 6, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, N.; Turki, A.; Aidalina, M. Implications of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare Delivery in the Hospital Settings: A Literature Review. Int. J. Public Health Clin. Sci. 2019, 6, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, K. Artificial Intelligence and the NHS: A Qualitative Exploration of the Factors Influencing Adoption. Future Healthc. J. 2021, 8, e648–e654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neher, M.; Petersson, L.; Nygren, J.M.; Svedberg, P.; Larsson, I.; Nilsen, P. Innovation in Healthcare: Leadership Perceptions about the Innovation Characteristics of Artificial Intelligence—A Qualitative Interview Study with Healthcare Leaders in Sweden. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2023, 4, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlicher, J.; Metsker, M.T.; Shah, H.; Demirkan, H. From NASA to Healthcare: Real-Time Data Analytics (Mission Control) Is Reshaping Healthcare Services. Perspect. Health Inf. Manag. 2021, 18, 1g. [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central]

- Akinwale, Y.O.; AboAlsamh, H.M. Technology Innovation and Healthcare Performance Among Healthcare Organizations in Saudi Arabia: A Structural Equation Model Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detwal, P.K.; Agrawal, R.; Samadhiya, A.; Kumar, A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. Revolutionizing Healthcare Organizations with Operational Excellence and Healthcare 4.0: A Systematic Review of the State-of-the-Art Literature. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2024, 15, 80–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Mills, G. Designing Chinese Hospital Emergency Departments to Leverage Artificial Intelligence—A Systematic Literature Review on the Challenges and Opportunities. Front. Med. Technol. 2024, 6, 1307625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wubineh, B.Z.; Deriba, F.G.; Woldeyohannis, M.M. Exploring the Opportunities and Challenges of Implementing Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: A Systematic Literature Review. Urol. Oncol. 2024, 42, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landicho, J.A. Predicting One-Year Readmission of Adult Patients with Pneumonia Using Machine Learning Approaches: A Case Study in the Philippines. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2024, 18, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]