Abstract

This study investigates the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Tokyo mango market by combining transaction data from the Ota Fruit Market with Google Mobility indices. In Japan, mangoes are regarded as a luxury fruit, largely dependent on imports and associated with high domestic production costs, which positions them as premium commodities. To assess the influence of price dynamics and human mobility on mango trading volumes during the pandemic, this study employs an autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model. The long-run results indicate that mango demand was positively associated with increased residential activity: a 1% rise in time spent at home during the COVID era corresponded to an increase of 786 kg in trade volume. Similarly, a 1% increase in time spent in retail and recreation areas was associated with a 364 kg rise in trade volume. In contrast, time spent in grocery and pharmacy locations showed no statistically significant effect. In the short run, fluctuations in mobility patterns and price levels contributed to variations in demand, with sales volumes adjusting toward their long-run equilibrium. The mobility indices exhibited mixed short-term effects on trade volumes. Notably, the analysis revealed that mango trading volumes rebounded in 2022, coinciding with the easing of pandemic-related disruptions.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has exerted substantial and wide-ranging effects on national economies and societies. A growing body of scholarly research [1,2,3,4,5] has investigated its implications for economic and social systems, particularly within the food and agriculture, trade, and business sectors. In Japan, the International Monetary Fund projected a 5.8% contraction in gross domestic product (GDP) for the year 2020, primarily attributable to a pronounced decline in consumer spending [6]. Additionally, the pandemic has caused severe disruptions across virtually all enterprises engaged in international food supply chains [7].

Japan’s agricultural sector is confronted with substantial structural challenges, including an aging and declining farming population and ongoing concerns regarding food security. The country’s heavy dependence on imported food—accounting for over 60% of total caloric intake—further exacerbates these vulnerabilities [8]. A number of studies have documented the adverse impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on agricultural production and trade.

Alam and Khatun reported that restrictions on human movement hindered agricultural sales [1]. Richards and Rickard, focusing on Canada, found that labor and logistics constraints severely disrupted fruit and vegetable distribution, forcing producers to divert supplies from food service establishments to retail outlets, which was accompanied by widespread closures of hotels, restaurants, schools, and other facilities [2]. Hayakawa and Mukunoki demonstrated that COVID-19 significantly reduced global trade in both importing and exporting countries, although the effects diminished after the initial wave [4].

In the Japanese context, Aruga analyzed the impact of the state of emergency (SOE) on the Tokyo wholesale tuna market using nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) price models, finding notable fluctuations in tuna prices across four SOE periods between 2020 and 2021 [3]. In a related study, Aruga et al. [9] examined the Tokyo vegetable market and found that SOEs increased the time residents spent at home, which in turn reduced the selling prices of many vegetables; the effect weakened over time, and perishability also played a role in price changes. Similarly, Ridley and Devadoss [10] found that high infection risks among farm workers disrupted fruit and vegetable production, leading to market losses. Murmu et al. [11] further identified demand-side shocks affecting the storage of perishable goods—including fresh fruits, vegetables, meats, and packaged foods—where both price and quality influenced demand. While these studies primarily addressed products purchased for daily consumption, little attention has been given to fruits bought for gift purposes. Aruga et al. [12] noted that luxury foods not consumed on a daily basis were more severely affected by the pandemic, though this evidence is limited to seafood.

Whether luxury fruit consumption was similarly influenced remains unclear. To address this gap, the present study investigates the impact of the pandemic on the Japanese mango market. In Japan, mangoes are widely regarded as a luxury gift item, particularly the Irwin variety, which has long been considered ornamental [13]. Mangoes are seasonal, typically available from May to July at the Tokyo wholesale market, and are rarely purchased for daily consumption. Given this limited trading period, few studies have investigated the effects of the pandemic on the mango market. Accordingly, the present study represents one of the first empirical attempts to assess the impact of COVID-19 on this niche segment of Japan’s agricultural economy.

In the subsequent section, the authors review the relevant literature addressing the impacts of COVID-19 on food, agriculture, and business. Thereafter, the analysis focuses on the economic dynamics of Japan’s fruit market and the circumstances surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic. The Materials and Methods section outlines the data sources, along with the economic models and statistical tools used to accomplish the study’s objectives. The results are presented in the following sections, while the concluding section summarizes the findings, highlights the study’s limitations, and considers practical implications.

2. Literature Review

Studies have shown that the global food supply chain, including the export of agricultural products, was heavily disrupted by COVID-19 regulations and restrictions. Businesses involved in the export of agricultural goods faced substantial financial losses during the early months of the pandemic, particularly in February and March 2020 [14,15]. In these initial stages, widespread uncertainty led people to remain at home, while lockdown measures caused sharp declines in consumer demand. Disruptions in logistics and reduced demand had notable adverse effects on Japan’s mango industry [2,16]. A Google Trends analysis by the International Food Information Council indicated that the pandemic and associated restrictions significantly altered global consumption patterns [5]. Changes in eating habits, coupled with mobility restrictions, led to pronounced shifts in food demand.

Extended periods indoors during government-declared states of emergency (SOEs) also influenced demand for certain high-value products. For instance, demand for luxury seafood items such as sea urchin (uni) and bluefin tuna (honmaguro) reportedly increased during SOE periods [17]. Alam and Khatun [1] found that decreased human mobility created challenges for marketing primary agricultural products, while Richards and Rickard noted that restricted movement posed threats to logistics systems and disrupted global food supply chains [2].

Japan’s seafood sector also experienced pandemic-related demand shocks. According to Global Fishing Watch, fishing activity levels remained stable despite declining demand. Aruga and co-researchers found that both affordable and luxury seafood prices were negatively affected in the short term. Over time, prices of lower-cost species, such as sardines and horse mackerel, recovered, while luxury seafood prices remained relatively stable [12]. Similarly, one study reported a decline in restaurant demand following the spread of the virus [18], while another observed price surges for commodities such as chickpeas, mung beans, and tomatoes during lockdowns [19].

The pandemic also led to widespread closures and bankruptcies in the food service sector [20]. Consequently, reconfiguring fresh produce supply chains is expected to have significant short-term effects. As consumers increasingly relied on retail channels, distribution infrastructure—particularly in supermarkets and online retail—faced sustained pressure. These changes are likely to continue testing supply chains beyond the pandemic. Long-term consequences may include shifts in labor markets, structural changes in the industry, increased business consolidation, and the expansion of online food shopping [2].

Examining immediate price effects in Europe, Akter found that increased time spent at home did not significantly influence fruit prices [21]. However, pandemic-related lockdowns and the global decline in air cargo capacity caused sharp reductions in Japan’s imports of fruits such as bananas, mangoes, avocados, and limes. Reports also indicated stakeholder concerns over potential shortages of imported cherries and lemons from the United States, as well as South African grapefruits [16].

3. Scenario in Japan

3.1. Economy of the Fruits Market in Japan

In 2022, Japan ranked as the sixth-largest importer of fresh fruits worldwide, with imported fruits accounting for nearly one-third of the country’s total supply [22]. Fruit imports have declined in recent years due to rising production and transportation costs, as well as a weakened yen, which has made imports more challenging for businesses [23]. Total fruit imports in Japan reached 1.63 million tons in 2022, down from 1.77 million tons in 2021 and lower than the 1.66 million tons imported in 2018. The average price of imported fruit increased to JPY 172 per kilogram in 2022, up from JPY 154 per kilogram in 2021, reflecting a significant 12 percent rise. This price was the highest recorded over the past ten years [23].

In recent years, per capita mango consumption in Japan has been gradually increasing, indicating a growing demand for tropical fruits [15]. However, mango consumption still lags behind several other high-demand fruits. To meet domestic demand, Japan heavily relies on imports, primarily from Mexico, Thailand, Taiwan, and Pakistan [24]. The combined consumption of guavas, mangoes, and mangosteens totaled approximately 11,000 tons in 2022, representing a 9.4% decline from 2021. The market value of these fruits also decreased by 10.4% compared to the previous year, amounting to approximately USD 50 million in 2022 [15].

Domestically, the prefectures of Okinawa, Miyazaki, and Kagoshima contribute the most to mango production, with a particular focus on Irwin-variety mangoes, which are harvested from April to September. Miyazaki mangoes, cultivated under abundant sunlight in one of Japan’s hottest prefectures, have gained popularity in recent years due to their premium image [13]. Valued for their vibrant, gem-like red color, juiciness, and sweetness, these mangoes are not harvested until they fall from the tree organically, in contrast to many other fruits produced in Japan [25]. Although their season spans from April to August, they are primarily available in wholesale markets in May and June [26]. Due to their exquisite flavor and high prestige as homegrown tropical fruits, Miyazaki mangoes are considered luxury items and are relatively expensive.

Luxury fruits are not typically part of everyday diets due to their high prices. The labor-intensive cultivation process, exceptional flavor, and flawless appearance contribute to their premium status, and such fruits are often reserved for special occasions or given as gifts [27,28]. In Japan, premium fruits—including square watermelons, Miyazaki mangoes, musk melons, white strawberries, and Ruby Roman grapes—are frequently presented as luxurious gifts. Miyazaki mangoes, locally known as Taiyo no Tamago (“Egg of the Sun”), are highly esteemed for their exceptional quality and command premium prices [25]. Indeed, Miyazaki mangoes are considered among the most expensive mango varieties globally [29].

Japan has a highly developed and intricate gift-giving culture, with widespread participation across various occasions. Purchasing and offering gifts hold substantial social importance, particularly during the two formal gift-giving seasons: Ochugen (summer gifts) and Oseibo (winter gifts) [30]. Fruits are commonly used as gifts, in addition to being consumed as desserts. In Japan, fresh fruits compete not only with vegetables but also with high-priced gift items such as sweets, snacks, and beverages [31]. They also highlighted that fresh fruits play a significant role in the competitive structure of the gift-giving industry, serving as popular souvenir items alongside sweets, tea, coffee, and seafood. Among these, fully ripened Miyazaki-grown mangoes are recognized as prestigious luxury gifts [25].

3.2. Scenario of COVID-19 in Japan

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Japanese authorities chose not to impose strict lockdowns or severe penalties for non-compliance. Nevertheless, public adherence to government guidance was generally high, which in some cases contributed to limiting the spread of the virus.

In the context of the pandemic, a “wave” is typically defined as a peak in infection cases followed by a subsequent decline. The Tokyo metropolitan area experienced five such waves between March 2020 and October 2021, peaking in April 2020, August 2020, January 2021, May 2021, and August 2021. Four states of emergency (SOEs) were declared during this period—one for each wave except the second [3]. Under the SOEs, the government urged residents to avoid non-essential travel, encouraged remote work, and implemented restrictions on hotels and restaurants, including limiting operating hours to between 5:00 a.m. and 8:00 p.m. These measures significantly influenced human mobility, social activities, and the national economy.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Used in the Study

Mango volume and price data for this study were obtained from the Ota Market of the Metropolitan Central Wholesale Market via the Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s official website [32]. Ota Market is the largest fruit market in the region, and Tokyo, as Japan’s largest city, recorded the highest number of COVID-19 cases from 2020 to 2022. Human mobility was significantly impacted during the COVID-19 pandemic, as movement patterns were notably restricted compared to pre-pandemic levels. Google LLC published Community Mobility Reports to help researchers, policymakers, and healthcare professionals understand the pandemic’s long-term effects on daily life. These reports use a baseline period defined as the median value for the five weeks prior to the global spread of COVID-19—specifically from 3 January to 6 February, 2020 [33]. The variable description is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of variables.

Mangoes are a seasonal fruit in Japan, typically available in wholesale markets during May and June. Accordingly, the dataset covers May and June for the years 2020, 2021, and 2022—periods most significantly impacted by the pandemic. In total, 125 daily observations were recorded: 42 in 2020, 42 in 2021, and 41 in 2022.

Two year-specific dummy variables—D2021 and D2022—were included to capture changes in market conditions relative to the base year 2020. D2021 equals 1 for observations from 2021 to 0 otherwise, while D2022 equals 1 for observations from 2022 to 0 otherwise. These variables allow the model to assess whether the effects observed in 2021 and 2022 differ significantly from those in 2020.

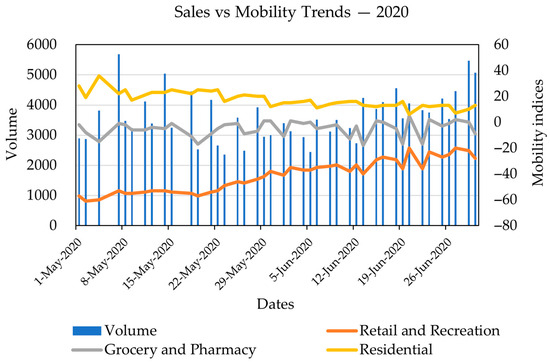

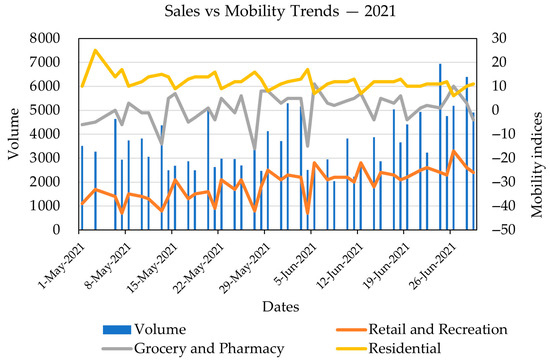

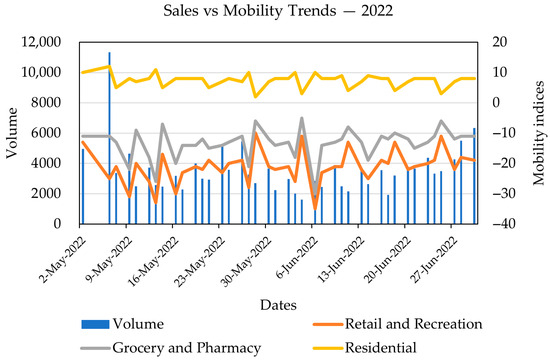

In addition to the economic theory and econometric analysis described in the following subsections, we have also employed descriptive visualization techniques to illustrate the relationship between mango sales volume and human mobility patterns. Three dual-axis line charts (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3) were used to visualize the daily mango sales volume against three community mobility trends (residential, retail and recreation, grocery and pharmacy). Mango sales took the primary axis in the graph, while mobility trends took the secondary axis. The data for each year is only available for 2 months (May and June). The dual-axis line chart was used as it allowed the comparison of trends between two different metrics (sales volume vs. mobility index) while avoiding scaling distortions. These visualizations complement the economic models and present a clear picture of how mango sales dynamics and human mobility patterns moved together over time.

Figure 1.

Sales vs. Mobility Trends in 2020.

Figure 2.

Sales vs. Mobility Trends in 2021.

Figure 3.

Sales vs. Mobility Trends in 2022.

4.2. Methodology

We developed a demand model with mango sales volume as the dependent variable to assess the influence of economic and behavioral factors. Consistent with basic economic theory, demand (mango volume) depends on price. In addition, mobility indices capture behavioral changes during the COVID-19 state-of-emergency (SOE) periods, reflecting alterations in the places and time people spent in their daily lives. Such changes may influence consumption patterns. Prolonged stays in residential areas, for example, could increase mango demand due to more time spent at home, while reduced time in retail and recreation locations could decrease purchase frequency and quantities.

Following the approach of Aruga et al. [34], who evaluated the effects of human mobility changes and SOEs on Tokyo energy prices, our model incorporates price and three Google mobility indices—residential, retail and recreation, and grocery and pharmacy—as explanatory variables. The general functional form is as follows:

where β0 is the intercept, β1, β2, β3, and β4 are the coefficients representing the marginal effects of each independent variable, and ϵ is the error term representing random disturbances or factors not explicitly included in the model.

Before estimating the model, we conducted standard unit root tests to assess the stationarity of the variables. Specifically, we applied the augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test [35], the Phillips–Perron (PP) test [36], and the Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin (KPSS) test [37]. The results (Table 2) indicate that all endogenous variables are integrated of order zero, I(0), or one, I(1), making them suitable for autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) analysis.

Table 2.

Unit root tests.

The autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model was employed in this study due to its efficiency in evaluating dynamic relationships [38,39]. A key advantage of the ARDL approach is its ability to produce reliable estimates even with small sample sizes, while mitigating issues related to omitted variables and autocorrelation [40,41]. The model is widely used in empirical research, particularly in time series analysis and applied econometrics, for purposes such as policy evaluation, forecasting, cointegration analysis, and modeling non-stationary data [41,42]. ARDL is particularly suitable for lagged data and allows for the identification of structural breaks, exploration of dynamic relationships, and estimation of both short-term and long-term effects [39,42,43]. Its flexibility and robustness make it highly relevant across fields, including macroeconomics, finance, international trade, and development economics [38,41,43].

In econometric research, it is crucial to assess variable stationarity when employing the ARDL model. This study uses the Phillips–Perron (PP), augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF), and Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin (KPSS) tests to assess stationarity [35,36,37]. The results determine whether variables require transformation to achieve stationarity. For estimating long-term relationships with the ARDL model, non-stationary variables may need transformation or may be cointegrated [44]. Seasonality and data patterns are also considered [45]. Both visual inspection and statistical tests are employed to ensure that the time series data are properly evaluated, thereby supporting the validity of the findings and the reliability of parameter estimates.

The Akaike information criterion (AIC) is applied to select optimal lag lengths for the ARDL models. The bounds test for cointegration is then conducted, followed by the use of conditional error correction models to examine short- and long-term dynamics.

The ARDL model estimation is conducted with the following unrestricted error correction model:

where p is the lag of the dependent variable, and q1, q2, q3, and q4 are that of the independent variables; is the first difference operator, and εt is the error term. The error term is assumed to be white noise, normally distributed, and identically distributed.

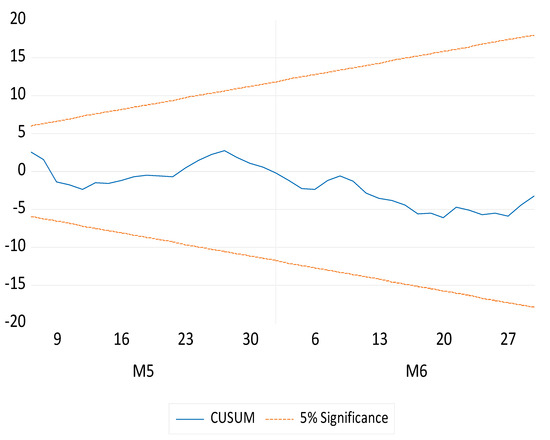

To address potential serial correlation and heteroskedasticity in the models, the Breusch–Godfrey (BG) test [46,47] for autocorrelation and the Breusch–Pagan test [48] for heteroskedasticity were conducted. In addition, the cumulative sum (CUSUM) test was applied to evaluate the stability of the parameters estimated by the ARDL model (Appendix A). The results of the BG test indicated no evidence of serial correlation at the 5% significance level, with a p-value of 0.4656, confirming that the data are not serially correlated.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Descriptive Summary

The three independent variables, in addition to price, are the residential mobility index, the retail and recreation mobility index, and the grocery and pharmacy mobility index. A positive value of the residential index indicates an increase in the amount of time spent at home. In contrast, the retail and recreation and grocery and pharmacy indices are predominantly negative, reflecting a reduction in the time spent in these locations. The following table (Table 3) presents the summary statistics of the variables used in the study.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

5.2. Visual Trends in Mango Sales and Human Mobility

To illustrate the relationship between mango sales and human mobility during the pandemic, Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 present dual-axis line charts for 2020, 2021, and 2022. Each figure displays the daily mango sales volume in May and June of each year alongside three mobility trends: residential, retail and recreation, and grocery and pharmacy.

In 2020 (Figure 1), residential mobility remained stable throughout the period, retail and recreation steadily increased with minor fluctuations, and grocery and pharmacy mobility showed small variations. In contrast, the mango sales volume experienced noticeable fluctuations but trended upward toward the end of the season, suggesting that changes in household consumption behavior could affect mango demand.

In 2021 (Figure 2), grocery and pharmacy mobility exhibited consistent fluctuations, while retail and recreation mobility gradually improved with some variation. Residential mobility remained relatively stable, although mango sales decreased compared to the previous year. In 2022 (Figure 3), both retail and recreation and grocery and pharmacy mobility experienced greater fluctuations than in the previous two years, while residential mobility remained stable alongside mango sales volume.

5.3. Linear ARDL Bounds Test for Cointegration

The linear ARDL bounds test was conducted to examine both short- and long-term relationships among the variables. Table 4 denotes the results of the bound test. As seen in the Table, the estimated F-statistic (6.7) exceeds the upper-bound critical value (4.79) at the 1% significance level, providing convincing evidence to reject the null hypothesis of no long-term relationship. This indicates the existence of a long-term cointegrating relationship among mango volume, price, the residential mobility index, the retail and recreation mobility index, and the grocery and pharmacy mobility index.

Table 4.

ARDL bound test for cointegration.

Table 5 shows the long-term coefficient estimation of the variables. The long-term coefficients from the levels equation reveal how each independent variable influences mango volume over time. Three of the four key variables—price, residential index, and retail and recreation index—have a statistically significant effect on mango volume at the 1% level.

Table 5.

Long-term coefficient estimation.

The long-term coefficients from the levels equation reveal how each independent variable affects mango volume over time. Three of the four key variables—price, residential mobility index, and retail and recreation index—have a statistically significant effect on mango volume at the 1% level. An inverse relationship exists between price and volume, indicating that higher prices for mangoes lead to lower sales. Conversely, the residential mobility index exhibits a positive and significant impact on mango volume. Residential mobility is associated with higher sales, likely because extended stays at home during the pandemic encouraged consumers to enhance their home environment and indulge in premium foods such as mangoes.

Similar trends have been seen in other luxury food markets. Aruga found that demand for luxury tuna sometimes increased during emergencies when people stayed home more, although in some cases, extended home stays led to decreased demand and lower prices [3]. White et al. [49] reported substantial declines in restaurant seafood demand during lockdowns, whereas Aruga [12] demonstrated that prolonged indoor stays exerted a negative impact on luxury seafood prices, which are predominantly driven by restaurant sales. A study in China revealed that urban consumers’ willingness to pay increased for certain luxury fruits during the pandemic [50]. Another study from Thailand predicted a significant increase in the export of durian, both in quantity and value, in 2020 compared to 2019 [51].

The retail and recreation index also shows a strong positive relationship with mango volume over the long term. Each additional unit of time spent on retail and recreation correlates with increased mango sales. In contrast, the grocery and pharmacy index has a positive coefficient but is not statistically significant, suggesting that time spent in these locations does not strongly influence mango volume. This is consistent with consumer behavior in Japan, where mangoes and other luxury products are rarely purchased from traditional grocery stores.

The following table (Table 6) presents a comprehensive summary of the variables, coefficients, standard errors, and probabilities derived from the findings of the Conditional Error Correction Regression analysis to show the short-term dynamics of the variables.

Table 6.

Short-term dynamics of the variables.

In the short term, initial changes in mango prices exhibit a significant relationship with volume, indicating that a price reduction is associated with a corresponding decline in mango sales over a brief period. Daily changes in residential mobility also positively influence mango volume. In contrast, short-term fluctuations in retail and recreation mobility, as well as the grocery and pharmacy mobility index, do not have a statistically significant impact on mango volume.

The model uses dummy variables for 2021 and 2022, with 2020 as the reference year, to account for year-specific effects on the mango market. The lack of statistical significance for 2021 suggests that market conditions did not significantly change from 2020. This stability may be attributed to consumer behavior during the peak of the pandemic, which remained largely consistent, and to government-imposed states of emergency (SOEs) in 2020 and 2021 that restricted outdoor activities, resulting in relatively stable consumer patterns. In contrast, the dummy variable for 2022 is statistically significant and positively correlated with mango volume, indicating a market recovery. This shift likely reflects both consumers’ adaptation to the ongoing pandemic and policy changes in 2022, which eased restrictions compared to previous years.

In summary, the short-term dynamics indicate a strong return of mango volume to its long-term equilibrium, with notable short-term effects driven by changes in price, residential mobility, and retail and recreation activities. Similarly, the 2022 dummy variable shows a statistically significant positive impact on mango volume, reflecting a recovery compared to the previous years.

Many studies have examined the impact of the pandemic on various luxury products. Achille and Zipser [52] noted that non-food luxury goods faced a sharp decline due to shop closures, supply chain disruptions, travel restrictions, production facility closures, and other factors. However, luxury fashion also saw an increase in sales through offline department stores during the pandemic [53]. According to Statista [54], global sales of personal luxury goods dropped significantly during the pandemic. This statistical evidence, along with findings from studies on luxury food items, supports the economics of luxury products. Unlike basic necessities, luxury goods generally show greater sensitivity to income and mobility shocks; their demand tends to grow disproportionately during periods of economic growth and fall sharply when income or mobility decreases [55].

Interestingly, for mango, a luxury food, demand and sales followed an upward trend during the COVID-19 pandemic. While pandemics typically lead to widespread economic downturns, premium foods such as mangoes are primarily purchased by consumers with higher disposable incomes. One important use of mango, gift-giving, has also been continued during the pandemic crisis, which has led to a positive sales trend of mango. Restrictions on travel, dining, and luxury experiences redirected spending toward high-end groceries and comfort foods, including mangoes. Additionally, prolonged stays at home encouraged experimentation with new recipes and ingredients, with photogenic foods like mangoes gaining popularity on social media. The boom in online shopping during the pandemic also expanded the market for premium mangoes. Furthermore, mangoes, being rich in vitamins, antioxidants, and fiber, became part of healthier dietary choices, which received particular attention during the pandemic. Collectively, these factors contributed to the expansion of the mango market and increased sales volume during COVID-19.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Tokyo mango market, focusing on sales volume and pricing at the Ota fruit market from 2020 to 2022. Using the ARDL model, we analyzed the effects of price and mobility indices—residential, retail and recreation, and grocery and pharmacy—on mango sales. The results indicate a significant long-term negative relationship between price and sales volume. However, increased time spent in residential areas and retail and recreation activities had a positive influence on mango demand. In contrast, the grocery and pharmacy index did not have a significant long-term effect.

Short-term dynamics were also evident. Mango sales volumes adjusted rapidly toward the long-term equilibrium in response to fluctuations in price and mobility patterns. Notably, the year 2022 exhibited a statistically significant positive effect on volume, reflecting both consumer adaptation and changes in government policies during the later stages of the pandemic.

These findings offer valuable insights for stakeholders in the retail and agricultural sectors as well as policymakers. For retailers and wholesalers, managing inventory and implementing dynamic pricing based on human mobility trends can help reduce demand shocks and boost sales. For policymakers, understanding the link between pricing, human mobility, and demand for luxury fruits helps them predict market disruptions, strengthen resilience, and develop strategies to maintain stable demand and supply during challenging times. The results also indicate that premium fruits like mango can be vulnerable to consumer behavior during crises such as a pandemic or other disasters. Additionally, this study highlights the importance of risk management strategies to stabilize supply, boost overall market resilience, and minimize monetary losses during disruptive events.

This study focused exclusively on the mango market during the COVID-19 pandemic. Future research could examine the pre- and post-pandemic periods in Japan’s fruit market to assess potential long-term structural changes. A key limitation of this study is its focus on Tokyo, which may not capture regional variations in consumer behavior or market dynamics. Beyond human mobility indices, future studies could incorporate additional variables, such as online sales data, consumer income levels, or other socioeconomic factors, to provide a broader perspective. While this research relied entirely on secondary data, collecting primary consumer data could help validate behavioral hypotheses and offer deeper insights.

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the pandemic’s impact on the fruit industry and related sectors, future research could also explore consumer behavior trends more extensively and expand the scope to include other premium fruits or different geographic regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.A.S. and K.A.; Methodology, M.S.A.S.; Validation, K.A.; Investigation, M.S.A.S.; Resources, K.A.; Writing—original draft, M.S.A.S.; Writing—review & editing, M.S.A.S. and K.A.; Supervision, K.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

ARDL Cumulative Sum (CUSUM) Test for Stability.

References

- Alam, G.M.M.; Khatun, M.N. Impact of COVID-19 on vegetable supply chain and food security: Empirical evidence from Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, T.J.; Rickard, B. COVID-19 impact on fruit and vegetable markets. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 68, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruga, K. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Tokyo wholesale tuna market. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2022, 36, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, K.; Mukunoki, H. COVID-19’s adverse impact on global trade. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 2021, 60, 101135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Ngoc, H.N.; Kriengsinyos, W. Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic and its lockdown on global eating behavior: A Google Trends analysis. Preprints 2020, 2020120701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). World Economic Outlook Update. June 2020. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/06/24/WEOUpdateJune2020 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Deconinck, K.; Avery, E.; Jackson, L.A. Food supply chains and COVID-19: Impacts and policy lessons. EuroChoices 2020, 19, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichten, J.; Kondo, C. Resilient Japanese local food systems thrive during COVID-19: Ten groups, ten outcomes. Asia-Pac. J. 2020, 18, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruga, K.; Islam, M.M.; Jannat, A. Effects of the state of emergency during the COVID-19 pandemic on Tokyo vegetable markets. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley, W.; Devadoss, S. The effects of COVID-19 on fruit and vegetable production. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2020, 43, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murmu, V.; Kumar, D.; Jha, A.K. Quality and selling price dependent sustainable perishable inventory policy: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Oper. Manag. Res. 2023, 16, 408–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruga, K.; Islam, M.M.; Jannat, A. The impacts of COVID-19 on seafood prices in Japan: A comparison between cheap and luxury products. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, K. Mango production in Japan. Acta Hortic. 2000, 509, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Key Statistics and Trends in International Trade 2020: Trade Trends Under the COVID-19 Pandemic; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ditctab2020d4_en.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Major Tropical Fruits: Market Review 2022; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/1834/11373 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences (JIRCAS). Global Supply Chain of Fruits and Vegetables Under Lockdown; JIRCAS: Tsukuba, Japan, 2020; Available online: https://www.jircas.go.jp/en/program/program_d/blog/20200615_1 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Takagi, S.; Wakai, T. Uni ya maguro, 20 bai ureta misemo koronaka de sakanashyohi kakudai [Fish consumption increases during the COVID-19 pandemic: Some shops increased their sales of sea urchin and tuna by 20-fold]. Asahi Shimbun, 30 June 2021. Available online: https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASP6Y5H2SP6XULFA034.html (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Yang, Y.; Liu, H.B.; Chen, X. COVID-19 and restaurant demand: Early effects of the pandemic and stay-at-home orders. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3809–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariappa, A.A.; Acharya, K.K.; Adhav, C.A.; Sendhil, R.; Ramasundaram, P. COVID-19 induced lockdown effects on agricultural commodity prices and consumer behaviour in India—Implications for food loss and waste management. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 82, 101160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA FAS. COVID-19 pandemics impact on Japan HRI industry. In GAIN Report JA2021 0098, 2021; USDA FAS: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=COVID-19%20Pandemics%20Impact%20on%20Japan%20HRI%20Industry_Tokyo%20ATO_Japan_06-25-2021 (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Akter, S. The impact of COVID-19 related ‘stay-at-home’ restrictions on food prices in Europe: Findings from a preliminary analysis. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA FAS. Food Inflation Presents Challenges and Opportunities in Japan; USDA FAS: Osaka, Japan, 2023. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Food+Inflation+Presents+Challenges+and+Opportunities_Osaka+ATO_Japan_JA2023-0131 (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- USDA FAS. Fresh Fruit Market Update 2023; GAIN Report JA2023 0090; USDA FAS: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Fresh%20Fruit%20Market%20Update%202023_Osaka%20ATO_Japan_JA2023-0090 (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- World Bank. Japan Guavas, Mangoes, and Mangosteens, Fresh or Dried Imports by Country. 2023. Available online: https://wits.worldbank.org/trade/comtrade/en/country/JPN/year/2023/tradeflow/Imports/partner/ALL/product/080450 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Government of Japan. Miyazaki-Grown Fully Ripened Mangoes. 2024. Available online: https://www.gov-online.go.jp/eng/publicity/book/hlj/html/202402/202402_05_en.html (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Miyazaki City Tourism. Rich Miyazaki mangoes. In Visit Miyazaki City Travel Guide; Miyazaki City Tourism: Miyazaki, Japan, 2024; Available online: https://www.miyazaki-city.tourism.or.jp/en/special/Rich_Miyazaki_Mangoes (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Shirai, M. Analyzing price premiums for foods in Japan: Measuring consumers’ willingness to pay for quality-related attributes. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2010, 16, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz, S.; Shim, S.; Gehrt, K. Japanese Fruit Consumers: Survey Targets Produce Choices. 1999. Available online: https://cales.arizona.edu/pubs/general/resrpt1999/marketingfruit.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Sahoo, J.P.; Panda, B.; Mishra, A.P.; Samal, K.C. Miyazaki. The Costliest Mango in the World Being Grown in the State of Madhya Pradesh, India. Just Agric. 2021, 1, 11. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353246926 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Moriuchi, E. Japanese consumer behavior. In Routledge Handbook of Japanese Business and Management; Haghirian, P., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 239–250. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrt, K.C.; Shim, S. The role of fruit in the Japanese gift market: Situationally defined markets. Agribusiness 1998, 14, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metropolitan Central Wholesale Market (MCWM). Metropolitan Central Wholesale Market Daily Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.shijou-nippo.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/index.html (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Google LLC. Google COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports. 2023. Available online: https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/ (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Aruga, K.; Islam, M.M.; Jannat, A. Does staying at home during the COVID-19 pandemic help reduce CO2 emissions? Sustainability 2021, 13, 8534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, D.A.; Fuller, W.A. Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1979, 74, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, P.C.; Perron, P. Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika 1988, 75, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, D.; Phillips, P.C.; Schmidt, P.; Shin, Y. Testing the null hypothesis of stationarity against the alternative of a unit root: How sure are we that economic time series have a unit root? J. Econom. 1992, 54, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Jannat, A.; Al Rafi, D.A.; Aruga, K. Potential economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on South Asian economies: A review. World 2020, 1, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J. Appl. Econom. 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyga-Łukaszewska, H.; Aruga, K. Energy prices, and COVID-immunity: The case of crude oil and natural gas prices in the US and Japan. Energies 2020, 13, 6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, P.K.; Smyth, R. The residential demand for electricity in Australia: An application of the bounds testing approach to cointegration. Energy Policy 2005, 33, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Pesaran, M.H. An autoregressive distributed-lag modelling approach to cointegration analysis. In Econometrics and Economic Theory in the 20th Century: The Ragnar Frisch Centennial Symposium; Strøm, S., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 371–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, I.; Nica, I.; Delcea, C.; Ciurea, C.; Chiriță, N. A cybernetics approach and autoregressive distributed lag econometric exploration of Romania’s circular economy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreshta, R.; Bhatta, B. Selecting an appropriate methodological framework for time series data analysis. J. Financ. Data Sci. 2018, 4, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uygur, S.; Bolat, F. ARDL bound testing approach for Turkish-flagged ships inspected under the Paris Memorandum of Understanding. J. Eta Marit. Sci. 2021, 9, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breusch, T.S. Testing for autocorrelation in dynamic linear models. Aust. Econ. Pap. 1978, 17, 334–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, L.G. Testing against general autoregressive and moving average error models when the regressors include lagged dependent variables. Econometrica 1978, 46, 1293–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breusch, T.S.; Pagan, A.R. A simple test for heteroscedasticity and random coefficient variation. Econometrica 1979, 47, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.R.; Koczberski, G.; Pande, S.; Workman, C.; Green, B.; Pahl, S. Early effects of COVID-19 on US fisheries and seafood consumption. Fish Fish. 2021, 22, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; He, D.; Chen, K. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Urban Residents’ Consumption Behavior of Forest Food—An Empirical Study of 6,946 Urban Residents. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1289504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueangrit, P.; Jatuporn, C.; Suvanvihok, V.; Wanaset, A. Forecasting Production and Export of Thailand’s Durian Fruit: An Empirical Study Using the Box–Jenkins Approach. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Lett. 2020, 8, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achille, A.; Zipser, D. A Perspective for the Luxury-Goods Industry During—And After—Coronavirus; McKinsey & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/a-perspective-for-the-luxury-goods-industry-during-and-after-coronavirus (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Pang, H.; Park, M.H.; Hwang, D. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic upon fashion consumerism: Focusing on online and offline channel consumption. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022, 34, 2149–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Impact of COVID-19 on Personal Luxury Goods Market; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2021; Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1257250/impact-of-covid-on-personal-goods-market/ (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Kapferer, J.N.; Bastien, V. The Luxury Strategy: Break the Rules of Marketing to Build Luxury Brands; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).