Abstract

To support novice learners, the Java programming learning assistant system (JPLAS) has been developed with various features. Among them, code writing problem (CWP) assigns writing an answer code that passes a given test code. The correctness of an answer code is validated by running it on JUnit. In previous works, we implemented a code plagiarism checking function that calculates the similarity score for each pair of answer codes based on the Levenshtein distance. When the score is higher than a given threshold, this pair is regarded as plagiarism. However, a method for finding the proper threshold has not been studied. In addition, AI-generated codes have become threats in plagiarism, as AI has grown in popularity, which should be investigated. In this paper, we propose a threshold selection method based on Tukey’s IQR fences. It uses a custom upper threshold derived from the statistical distribution of similarity scores for each assignment. To better accommodate skewed similarity distributions, the method introduces a simple percentile-based adjustment for determining the upper threshold. We also design prompts to generate answer codes using generative AI and apply them to four AI models. For evaluation, we used a total of 745 source codes of two datasets. The first dataset consists of 420 answer codes across 12 CWP instances from 35 first-year undergraduate students in the State Polytechnic of Malang, Indonesia (POLINEMA). The second dataset includes 325 answer codes across five CWP assignments from 65 third-year undergraduate students at Okayama University, Japan. The applications of our proposals found the following: (1) any pair of student codes whose score is higher than the selected threshold has some evidence of plagiarism, (2) some student codes have a higher similarity than the threshold with AI-generated codes, indicating the use of generative AI, and (3) multiple AI models can generate code that resembles student-written code, despite adopting different implementations. The validity of our proposal is confirmed.

1. Introduction

Java programming in education is considered highly important because it bridges academic learning with professional demands. Java remains one of the dominant languages in modern software development, especially in enterprise systems, back-end infrastructures, and mobile applications, due to its scalability, portability, and security features [1,2]. From the educational perspective, learning Java provides students with strong foundations in object-oriented programming concepts and significantly enhances academic achievements regardless of their prior backgrounds, making it an effective medium to equalize learning opportunities across diverse student groups [3]. Therefore, mastering Java programming not only equips students with essential industry driven skills but also supports equitable and measurable learning outcomes in higher education.

To support these educational needs, we have developed the Java programming learning assistant system (JPLAS), a web-based platform designed to support self-learning through both code reading and code writing [4]. JPLAS provides a structured type of exercises with varying levels of difficulty, allowing students to gradually strengthen their programming skills through independent practices [5]. The answer platform is implemented on Node.js [6] and is deployed to students using Docker [7], ensuring scalability, efficient performance, and ease of access. Its instant-marking automated function enables students to receive immediate feedback, making the learning process more interactive and effective.

Among the types of exercises provided in JPLAS, the code writing problem (CWP) is designed to train students to write a source code from scratch that will pass a given test code in each assignment [4]. This test code specifies the requirements in the assignment. The correctness of any answer source code from a student is validated by running it on JUnit [8]. By solving CWPs, it is expected that students strengthen their ability to translate problem specifications into functional code, laying the foundation for more advanced programming tasks. In addition, to assist teachers, an answer code validation program has been implemented, which automatically verifies the correctness of students’ submissions for CWPs by running the test code on JUnit and reporting the results [9].

In previous studies, we have implemented a code plagiarism checking function in the answer code validation program, aiming to detect plagiarism cases among students’ answer codes for CWP assignments [10]. This function first removes the whitespace and comment lines with regular expressions from an answer code. Then, it calculates the Levenshtein distance [11] for each pair of the codes from two students and makes the code similarity score based on it. However, our previous study did not provide a systematic method for selecting a proper threshold to determine the plagiarism for each assignment.

Currently, generative AI technologies have emerged and have become popular to assist various activities among people, including programming. Hence, the threat of submitting AI-generated codes by students as their own work has become serious. Recent research has shown that the frequent use of Large Language Models (LLM) such as ChatGPT [12] or Copilot [13] for code generation correlates with lower student performances, reinforcing the concern that this AI-assisted coding can lead to academic integrity issues including plagiarism [14]. While generative AI models can support student learning, over-reliance on them can undermine the learning outcome of core programming concepts, hinder independent problem-solving [15], and raise ethical concerns, if students submit code without understanding its logic [16].

In this paper, to address the above-mentioned issues, we propose a threshold selection method in the code plagiarism checking function, using Tukey’s interquartile range (IQR) method [17]. This method dynamically adapts the threshold to the similarity score distribution for each assignment, enabling the adjustment of differences between students and assignments. In this method, the interquartile range (IQR) is considered as a statistical measure that describes the central 50% of the data between the third quartile (Q3) and the first quartile (Q1). Using Tukey’s IQR method, lower fences and upper fences are calculated to identify the outliers [18]. For plagiarism detection, we use the upper fence to select the assignment specific threshold to choose unusually high similarity scores that suggest high potential plagiarism. Furthermore, a simple percentile-based adjustment based on the 99th percentile is applied to adjust the upper threshold in skewed distributions, allowing the method to isolate only the most extreme similarity scores.

To investigate AI-generated codes, we design the prompts to generative AI for generating answer source codes for each assignment and apply them to four different AI models, namely, ChatGPT [12], Github Copilot [13], Gemini [19], and Microsoft Copilot [20]. The use of multiple AI models is intended to capture a broader spectrum of coding styles and solution strategies that different modern AI models are capable of producing. By applying the designed prompts, we systematically collect AI-generated codes and compare them to students’ submissions. This approach allows us to evaluate not only the similarity between student and AI codes but also the variation in implementation strategies across different AI models.

For evaluation, we used a total of 745 source codes of two datasets. The first dataset consists of 420 answer codes across 12 CWP instances from 35 first-year undergraduate students in the State Polytechnic of Malang, Indonesia (POLINEMA). The second dataset includes 325 answer codes across five CWP assignments from 65 third-year undergraduate students at Okayama University, Japan. The applications of our proposals found the following: (1) any pair of student codes whose score is higher than the selected threshold has some evidence of plagiarism, (2) some student codes have higher similarity than the threshold with AI-generated codes, indicating the use of generative AI, and (3) multiple AI models can generate code that resembles student-written code, despite adopting different implementations.

This paper’s structure is outlined as follows: Section 2 discusses the relevant research in the literature. Section 3 reviews our previous study of the code plagiarism checking function. Section 4 presents the implementation of the threshold selection method. Section 5 discusses the experimental results. Section 6 provides a discussion of the study’s limitations and proposes several directions for future work. Finally, Section 7 concludes this paper.

2. Literature Review

In this section, we explore previous studies related to this study, with an emphasis on research exploring threshold selections and plagiarism on AI-generated code prevention using prompts.

2.1. Threshold Selection Tools

First, we introduce studies on threshold selection.

In [21], Dhakal et al. proposed an automated literature review pipeline using a statistical thresholding method based on the interquartile range (IQR). This approach analyzes the distribution of cosine similarity scores to set adaptive cutoffs, retaining highly relevant papers while filtering out less meaningful ones. This IQR-based thresholding approach improved precision and enhanced the reliability of the retrieval process.

In [22], Swami et al. presented a method to detect and mitigate DDoS attacks in Software-Defined Networks (SDN). Using the interquartile range (IQR) of network metrics like packet rates and flow counts, this method sets thresholds to identify anomalous traffic. By calculating upper fences from normal traffic, flows that deviate significantly are flagged, improving the detection accuracy and reducing false positives through dynamic thresholding.

In [23], Cadamuro et al. investigated sentence similarity using a distribution-based threshold method. They applied a Siamese neural network to compute vector distances between sentence pairs, creating distributions for similar and dissimilar pairs. By analyzing these distributions, the method automatically sets thresholds to distinguish similar pairs from dissimilar sentences, improving semantic similarity accuracy and generalization across datasets.

In [24], Elsharkawi et al. introduced a statistical thresholding mechanism for Vision Graph Neural Networks. By modeling similarity scores with a normal distribution and applying inverse cumulative distribution function (CDF), only highly similar edges are preserved. A decreasing threshold across layers counters over-smoothing, improving the feature aggregation and accuracy on large-scale image classification while remaining efficient.

In [25], Liu et al. presented threshold selection methods for ocean environmental design parameters using the peak over threshold (POT) approach. They applied mean residual life plots and coherence spectrum-based thresholds to reduce subjectivity and reliably estimate extreme design parameters such as return levels.

In [26], Safari et al. used goodness-of-fit approaches based on empirical distribution functions, including Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Kuiper statistics, with Monte Carlo simulations to select optimal thresholds in Pareto tail modeling. Their method minimizes outlier effects, with Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Kuiper statistics performing best among empirical distribution function- (EDF) based measures.

Based on the above literature review, it can be observed that recent research on threshold selection increasingly emphasizes the importance of understanding and utilizing data distribution characteristics. Approaches such as the interquartile range (IQR) and other distribution-based models rely on statistical properties such as the spread, skewness, and variability to determine adaptive cutoff values. By analyzing the underlying distribution of data, these methods can dynamically adjust the threshold boundaries rather than depending on fixed or empirically chosen parameters.

Furthermore, thresholds derived from data distributions offer a more objective and reliable basis for decision-making, minimizing human bias and reducing false detection rates. These insights indicate that future research on threshold selection should continue to focus on leveraging statistical distribution modeling to develop adaptive, scalable, and context-aware thresholding mechanisms.

2.2. Prompt-Based AI Plagiarism Prevention

Second, we explore studies addressing plagiarism in programming education, emphasizing its potential risks to students’ learning integrity and skill development.

In [27], Liu et al. introduced an explainable detection method to identify AI-generated pseudocode in online programming courses for high school students. Instead of providing direct corrections, the system finds differences between student-written and AI-generated pseudocode using simple prompts. It analyzes basic linguistic features, such as sentence length, verb patterns, and structural characteristics, ensuring interpretability while effectively detecting AI-generated submissions.

In [28], Bashir proposed a framework to discourage student dependence on generative AI in programming education. This method involves creating and sharing pseudo-AI submissions, generated by instructors using prompt engineering, to demonstrate that AI-like outputs can be recognized. This approach helps academic integrity and motivates students to produce original code.

In [29], Roest et al. explored how Large Language Models (LLMs) can support programming education without encouraging reliance on AI-generated solutions. They developed the step assisted programming tutor (StAP-tutor), which provides next-step hints instead of full answers. Using prompt engineering with OpenAI model, prompts with only the problem description and keywords generated short context-aware feedback, helping to prevent plagiarism and promote active learning.

In [30], Heickal et al. proposed the feedback ladder system using GPT-4. Instead of direct fixes, it generates multilevel feedback guiding students to understand and correct logical errors. The ladder has five levels, from a simple correctness verdict to minimal code edit suggestions, balancing support and learning opportunities.

Based on relevant studies, the creation of proper prompts in programming education is important to prevent plagiarism with AI-generated codes. By designing prompts that can be compared with students’ code submissions, instructors with these systems are able to identify potential similarities and detect whether students rely on AI-generated solutions, to encourage them actively with programming tasks and develop their problem-solving skills.

In this study, several simple prompts were designed from different AI models to assess the possibility of AI-generated plagiarism in students’ code. Our approach intends to reduce over-reliance on AI models, which could negatively affect students’ understanding of programming concepts and their abilities to follow logical programming workflows.

3. Code Plagiarism Checking Function

In this section, we review the code plagiarism checking function in our previous study. It was designed to detect plagiarism using the Levenshtein distance between two source codes for the same assignment [10].

3.1. Levenhstein Distance

The Levenshtein distance is a metric used to quantify the similarity between two strings or sequences [31]. It is defined as the minimum number of single-character edits, insertions, deletions, or substitutions that are required to transform one string into another. The smaller the value of the distance, the more similar these strings are. Then, the similarity score in this function is computed using the following formula:

where max(length of string1,length of string2) represents the larger length between string1 and string2.

3.2. Code Plagiarism Checking Function Procedure

The code plagiarism checking function compares each pair of source different source codes from students and generates a CSV file of their similarity scores. The process is summarized as follows.

- Import the required Python libraries for calculating the Levenshtein distance, CSV output, and the use of regular expressions.

- Read the source code files of two students, and remove all the whitespace characters such as spaces, tabs, and comments, using regular expressions to make a single string for each file

- Calculate the Levenshtein distance with the editops function.

- Convert the Levenshtein distance into a similarity score.

- Repeat Steps 2–4 for all the source code files in the folder for one assignment.

- Sort all the files in descending order of similarity scores and output the results into a CSV file.

3.3. Plagiarism Examples

Several examples with highly possible plagiarism found by the proposed function and manual inspections are shown below.

3.3.1. Exact Code Copy

This refers to source codes that are identical with no or minimal modifications. These codes keep the original logic, structure, and comments of the code, showing that the code was directly copied without any change.

3.3.2. Comments Modification

This refers to source codes that are identified as having exactly the same program logic and structure, with differences only in comments. The comment modifications may include paraphrasing, adding new comments, or removing existing ones. Moreover, there is a possibility of plagiarism involving generative AI models that can generate distinctive comments.

3.3.3. Identifiers Modification

This refers to source codes, where their overall code structure remains the same, while only some names for variables, methods, or classes are changed. Its often involves copying the original code and making small changes, such as renaming variables, in an attempt to make the copied code appear different. Although the functionality is unaffected, the underlying logic remains the same, resulting in a high similarity score. Listing 1 shows the original source code, while Listing 2 shows its modified version in which variable names for the parameter array and loop index were changed. The similarity score for this pair is 72.82%.

| Listing 1. Original code. |

| 1: // This method sorts the input array in ascending order using BubbleSort 2: public int[] bubbleSort(int[] arr) { 3: for (int i = 0; i < arr.length - 1; i++) { 4: for (int j = 0; j < arr.length - 1 - i; j++) { 5: if (arr[j] > arr[j + 1]) { 6: int temp = arr[j]; 7: arr[j] = arr[j + 1]; 8: arr[j + 1] = temp; 9: } 10: } 11: } 12: return arr; // returns sorted array 13: } |

| Listing 2. Modified code. |

| 1: // This method sorts the input array in ascending order using BubbleSort 2: public int[] bubbleSort(int[] array) { 3: for (int x = 0; x < array.length - 1; x++) { 4: for (int y = 0; y < array.length - 1 - x; y++) { 5: if (array[y] > array[y + 1]) { 6: int tmp = array[y]; 7: array[y] = array[y + 1]; 8: array[y + 1] = tmp; 9: } 10: } 11: } 12: return array; 13: } |

3.3.4. Function Modifications

This modification refers to changes in existing functions such as updating the signature, rewriting the logic, or merging and adding helper functions while preserving the original code. These modifications may include adjusting loops, changing variable usage, or splitting/combining functionality to make the copied code appear different, where the fundamental logic and results outcomes remain the same, resulting in a high similarity score. Listing 3 presents the original code, which sorts an input array in ascending order using nested loops and a temporary variable for swapping. Listing 4 shows its modified version that introduces a swapped flag to optimize the sorting process. This flag allows the algorithm to terminate early if the array is already sorted during a pass, improving the efficiency in best-case scenarios. The similarity score for this pair is 72.08%.

| Listing 3. Original code. |

| 1: // This method sorts the input array in ascending order using BubbleSort 2: public int[] bubbleSort(int[] arr) { 3: for (int i = 0; i < arr.length - 1; i++) { 4: for (int j = 0; j < arr.length - 1 - i; j++) { 5: if (arr[j] > arr[j + 1]) { 6: int temp = arr[j]; 7: arr[j] = arr[j + 1]; 8: arr[j + 1] = temp; 9: } 10: } 11: } 12: return arr; // returns sorted array 13: } |

| Listing 4. Modified code. |

| 1: // This method sorts the input array in ascending order using BubbleSort 2: public int[] bubbleSort(int[] arr) { 3: for (int i = 0; i < arr.length - 1; i++) { 4: boolean swapped = false; 5: for (int j = 0; j < arr.length - 1 - i; j++) { 6: if (arr[j] > arr[j + 1]) { 7: int tmp = arr[j]; 8: arr[j] = arr[j + 1]; 9: arr[j + 1] = tmp; 10: swapped = true; 11: } 12: } 13: if (!swapped) break; // stop if no swaps 14: } 15: return arr; 16: } |

4. Threshold Selection Method

In this section, we present a threshold selection method to identify potential plagiarism cases using Tukey’s Interquartile Range (IQR) fences from the statistical distribution of similarity scores.

4.1. Interquartile Range (IQR)

The interquartile range (IQR), also called the midspread or middle 50%, is a statistical measure of data dispersion, widely used for detecting outliers [17]. The IQR is a univariate method in statistical modeling that relies on the median to identify data points deviating significantly from the overall pattern. The choice of statistical measures such as the median, mean, or mode depends on the variability of the data and the presence of outliers. In datasets with low variability and no outliers, the mean and standard deviation are typically used to describe the central tendency and dispersion.

However, when the variability is high, or outliers are present, the median and IQR are preferred, as they provide a more robust and reliable assessment of the data distribution. Compared with alternative approaches, such as the Z-score, which assumes a normal data distribution, or density- and distance-based methods, the IQR is non-parametric, straightforward to compute, and resilient to skewed data [22].

These properties make the IQR especially appropriate for educational datasets, where similarity scores may be abnormal, and extreme values often indicate meaningful anomalies rather than noise. To calculate the IQR, data are arranged in ascending order and are divided into quartiles using linear interpolation: (the lower quartile, 25th percentile), (the median, 50th percentile), and (the upper quartile, 75th percentile). The IQR is obtained by subtracting the first quartile from the third quartile:

Tukey et al. proposed the 1.5 × IQR rule to identify potential outliers in a dataset. Tukey’s IQR method is non-parametric and widely used to detect unusual values in normal or abnormal distribution [18]. Outliers are identified as values lying outside the lower and upper fence, which are determined as

In the context of code similarity analysis, outliers above the upper fence are particularly important, because they correspond to unusually high similarity scores, which may indicate potential cases of plagiarism. Therefore, the upper fence serves as a practical threshold to flag code pairs that require further inspection.

4.2. Percentile-Based Adaptive Threshold

Traditionally, the upper fence in Tukey’s method is defined with the coefficient , which is generally effective for detecting outliers in normally distributed data. However, in the case of similarity scores between student codes, the distribution is often skewed and may contain multiple extreme values [32]. Using the conventional can either flag too many pairs (high false positives) or miss genuinely high similarities (false negatives).

To support this, we introduce a percentile-based adjustment by setting the threshold at the 99th percentile () of the similarity score distribution. This approach effectively adapts the Tukey coefficient k to the characteristics of each assignment.

Anchoring k to the 99th percentile ensures that only the highest similarity cases are flagged. Since high similarity scores are common in programming assignments due to shared algorithmic patterns, lower thresholds may result in many false positives. By focusing on the top 1% of similarity scores, the proposed method effectively highlights cases with the highest potential for plagiarism, while providing a clear mathematical rationale for integrating the percentile with Tukey’s fences.

4.3. Computational Complexity of the Threshold Selection Method

The proposed threshold selection method is applied after all pairwise similarity scores have been computed. When each of n students submitted one code, the total number of pairwise scores is . The thresholding step, combining Tukey’s IQR rule with the 99th percentile operates on this one-dimensional array of p values. Computing the quartiles, IQR, and percentile values requires sorting the p similarity scores, which runs in time.

Since this cost is negligible compared to the preceding complexity of the pairwise Levenshtein computations, the thresholding step introduces only minimal additional overhead. Therefore, the proposed threshold selection process remains computationally efficient even as the number of student submissions increases, while the underlying similarity computation continues to be the primary scalability bottleneck.

In addition, we measure the CPU time for applying the threshold selection method to all the source codes for each assignment in Section 5.1. The PC environment consists of an AMD Ryzen 7 6800U CPU @2.7 GHz, running with 64-bit Microsoft Windows 11. The threshold selection method was implemented using Python 3.11.5.

4.4. Threshold Selection Method Procedure

The proposed threshold selection method is described in the following procedure:

- Import the necessary Python libraries to calculate the threshold, and visualize the distribution in a histogram using Tukey’s IQR fences.

- Read the similarity score CSV files that have been generated for each assignment.

- Compute the quartile values and , and calculate the IQR.

- Calculate the upper fence threshold using the Tukey’s IQR fences with the value of k determined using the 99th percentile.

- Save the results into a CSV file that contains the student IDs and labels indicating possible plagiarism as “High” or “Low”.

- The results are generated separately for Student and Student code pairs and Student and AI code pairs.

- Repeat Steps 2–7 for all assignments in the dataset.

5. Evaluation

In this section, we applied the threshold selection method to several code writing problem (CWP) assignments and evaluated the results.

5.1. CWP Assignments

Two different sets of CWP assignments were used in this study. The first dataset consists of 12 CWP assignments given to first-year undergraduate students in the State Polytechnic of Malang, Indonesia (POLINEMA). These assignments cover basic data structure and algorithm topics and can be categorized into four groups: sorting algorithms, searching algorithms, linear data structures, and linked data structures [33].

The second dataset consists of five CWP assignments given to third-year undergraduate students at Okayama University, Japan. These assignments focus on fundamental algorithm and object-oriented concepts and are categorized into three groups: fundamental algorithm, looping constructs, and method overriding. Table 1 summarizes the assignment type, assignment ID, topic, and CPU time for each CWP.

Table 1.

CWP assignments for evaluations.

5.2. Assignment to Students

We assigned the first dataset to 35 first-year undergraduate students in the Algorithms and Data Structures course at POLINEMA, resulting in a total of 420 student answer codes. All students had previously acquired basic Java programming skills. Before starting the assignments, students received a guidebook containing several Java example problems and all CWP assignments with the test code. The students were given one week to complete the 12 CWP instances at home. This arrangement ensured that students had adequate time to complete and practice the assignments while maintaining standardized submission conditions.

In our previous works, we introduced a test code-based approach using these 12 CWP assignments to support the automated evaluations of students’ answer source codes and to improve learning outcomes [33]. Through this approach, each submitted code was automatically assessed using the test code to ensure both correctness and adherence to the implementation specifications. The analysis of 35 student submissions across 12 CWP assignments revealed that most students achieved a perfect correct rate of 100%, while several students showed gradual declines, with the lowest average rate being 67%.

For the second dataset, the CWP assignments were given to 65 third-year undergraduate students at Okayama University, Japan, as part of a Java programming course assignment. This dataset consists a total of 325 student answer codes collected from five CWP assignments. The assignments were conducted during a supervised two-hour class session, where one class hour corresponds to 100 minutes. Within this session, students were required to complete all five CWP assignments under controlled conditions.

5.3. Three Categories in Applications

We applied the code plagiarism checking function to source code pairs in three categories; Student and Student pairs, Student and AI pairs, and AI and AI pairs to facilitate a more structured and clear examination of potential plagiarism. Student represents source codes made by students. AI represents source codes generated by generative AI models.

5.4. Results for Student and Student

First, we discuss the results of student and student.

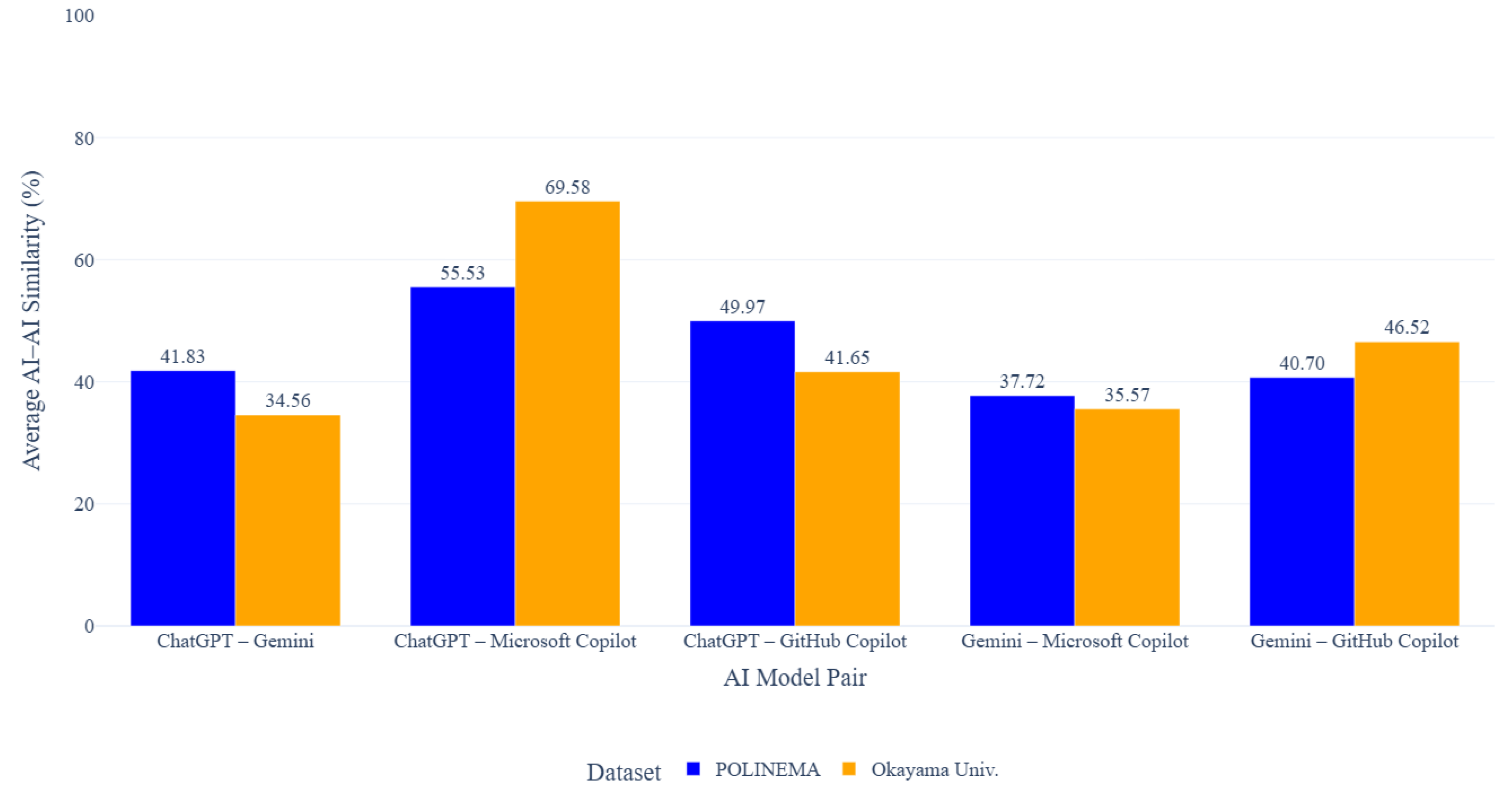

5.4.1. Similarity and Threshold Results

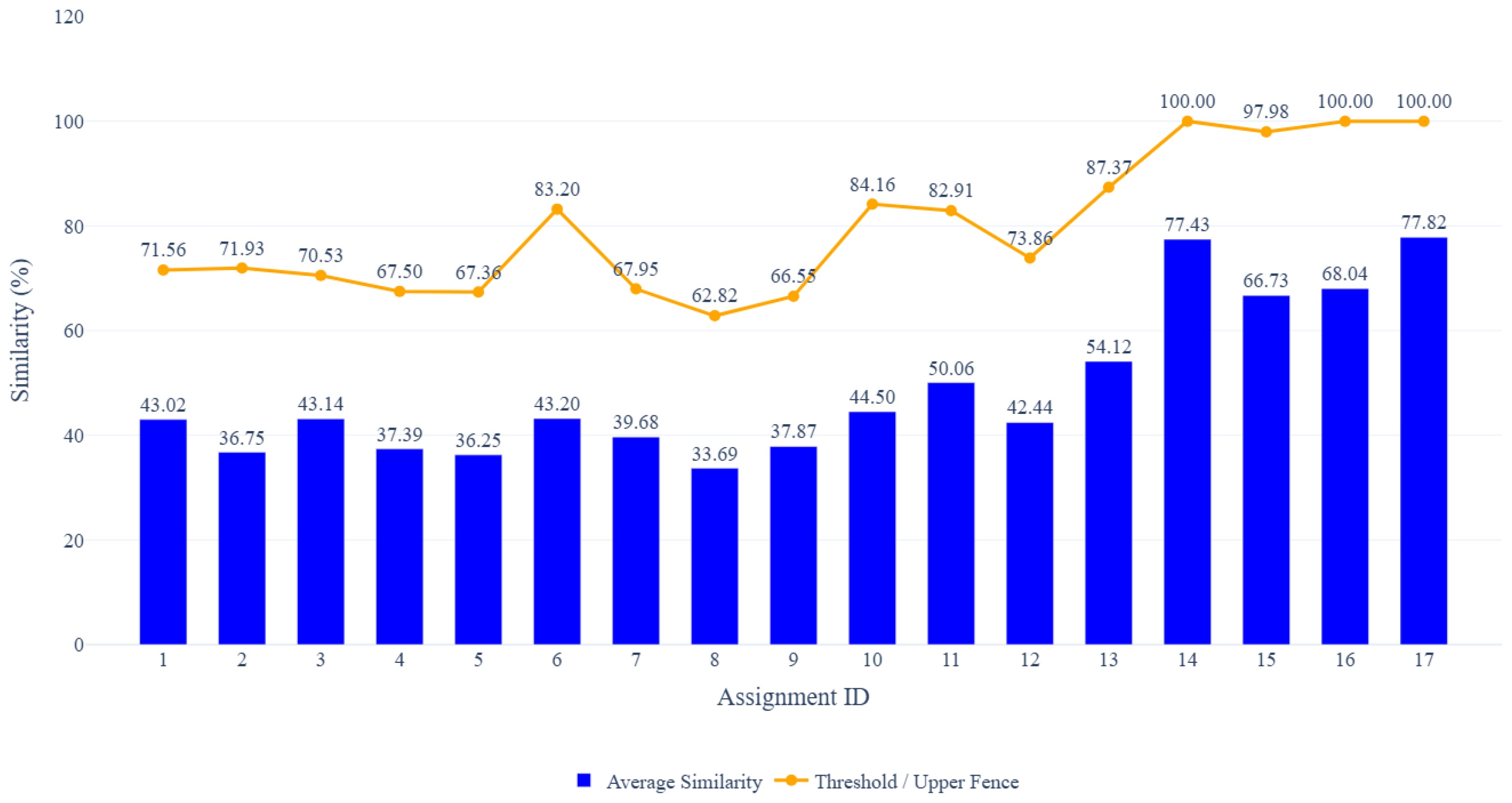

Figure 1 and Table 2 show the result of the average similarity score and the threshold of each assignment, respectively. Assignment at ID = 8 has the lowest average similarity score of 33.69%, showing variations in how students made different implementations, while the highest occurs in assignment at ID = 17 with 77.82%, followed by ID = 14 with 77.43% and ID = 16 with 68.04%.

Figure 1.

Results of Student and Student.

Table 2.

Summary of Student and Student similarity.

These results show that assignments at ID = 14, 16, and 17 from Okayama University dataset yield threshold values of 100% due to the large number of code pairs exhibiting similarity scores of 100%. Closer inspection reveals that this is primarily caused by the simplicity of the assignments and the strict constraints imposed by the provided test codes, which substantially limit implementation diversity. Moreover, these tasks focus on basic programming concepts, leading third-year undergraduate students, who have more advanced basic programming to produce straightforward solutions. Therefore, many students independently produce nearly identical code, causing the distribution to concentrate at the upper bound and leading to a Tukey-based threshold of 100% for these assignments.

Assignments involving data structures such as linked lists and searching algorithms from the POLINEMA dataset, particularly at ID = 10, 11, and 6, also tend to produce higher similarity levels. Manual inspection indicates the limited variation in implementation requirements impacts the similarity for these data structure tasks. As a result, students often follow similar coding patterns and structural designs even when working independently, which increases the observed similarity scores.

In contrast, sorting algorithms such as assignments at ID = 2, 4, and 5 produce lower similarity levels, reflecting greater variations in implementations. The threshold is selected using the Tukey’s method anchored to the 99th percentile, resulting in the same number of flagged pairs per assignment (top 1%) to focus exclusively on the most extreme similarity cases, which can signal potential plagiarism.

5.4.2. Pairs with High Similarity in Multiple Assignments

By analyzing source codes with similarity scores above the thresholds, further manual inspection was conducted on students who also exhibited high similarity in multiple assignments. Table 3 shows that the student ID pairs 25–26 and 10–13 from the POLINEMA dataset exhibit the highest average similarity above 94%, with nearly identical code structures, indicating high plagiarism. In the Okayama University dataset, student ID pairs 2–8 exhibits extremely high similarity across four assignments with an average of 100% with an identical code structure evidence, which raises strong suspicion of plagiarism.

Table 3.

Student pairs with high similarity in multiple assignments.

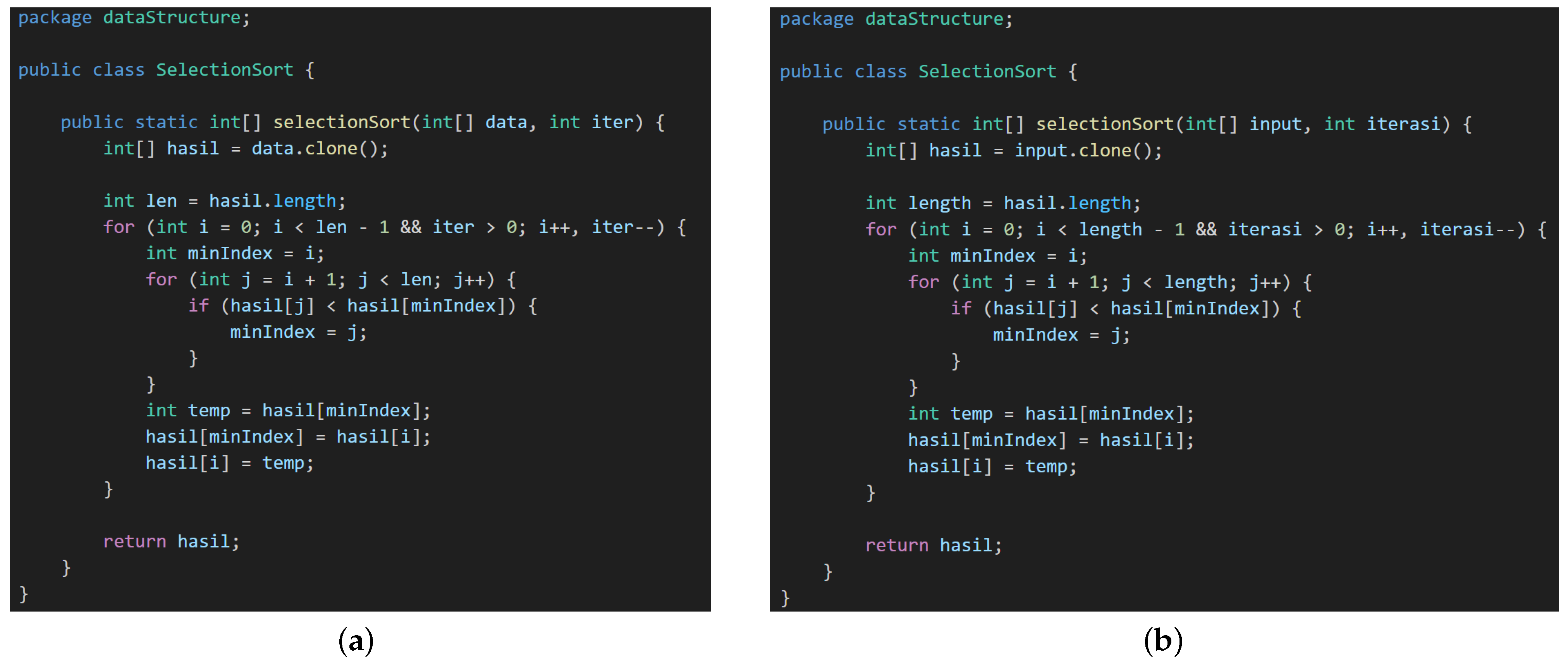

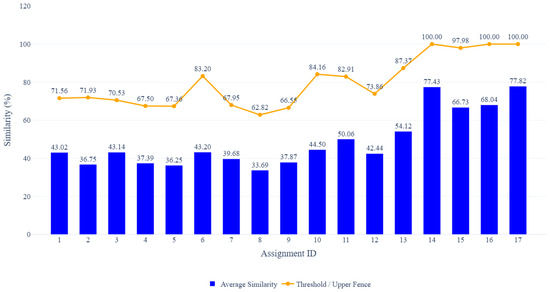

The following figures present selected case studies of student pairs with high similarity scores from the SelectionSort assignment. Figure 2a shows the execution results and code interface for Student ID 13, while Figure 2b shows the corresponding code for Student ID 4 with a similarity score of 84.87%. Both codes exhibit a pattern of potential plagiarism characterized by identifiers modification, where variable names from student ID 13 such as data is changed to → input, iter → iterasi, and len → length in the student ID 4 code while the overall code structure, logic, and algorithmic steps remain identical. This pattern highlights minimal efforts to disguise copied code while retaining functional equivalence.

Figure 2.

Comparison of two students’ code with identifiers modification plagiarism pattern. (a) Student ID 13. (b) Student ID 4.

5.5. Results for Student and AI

For the student and AI evaluation, four AI models: ChatGPT, Gemini, Microsoft Copilot, and GitHub Copilot were used to generate solutions for a total of 17 CWP assignments from both of datasets using three types of prompts. These models were selected due to their popularity and widely used for code generation, frequently utilized by students for programming tasks. This evaluation aims to examine whether similarities between student submissions and AI-generated codes can indicate potential use of AI-assisted coding during assignment completion.

Three types of prompts were used to generate the AI codes. The prompts were kept simple and clear to focus on producing functional and readable code, which reflects typical student-level submissions. The prompt simplicity ensures that differences in the similarity scores are primarily due to the AI models’ code generation behavior, rather than highly complex or ambiguous instructions, allowing for a fair comparison with student submissions. In total, 204 AI-generated codes were produced, as summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Prompts used for generating AI source codes.

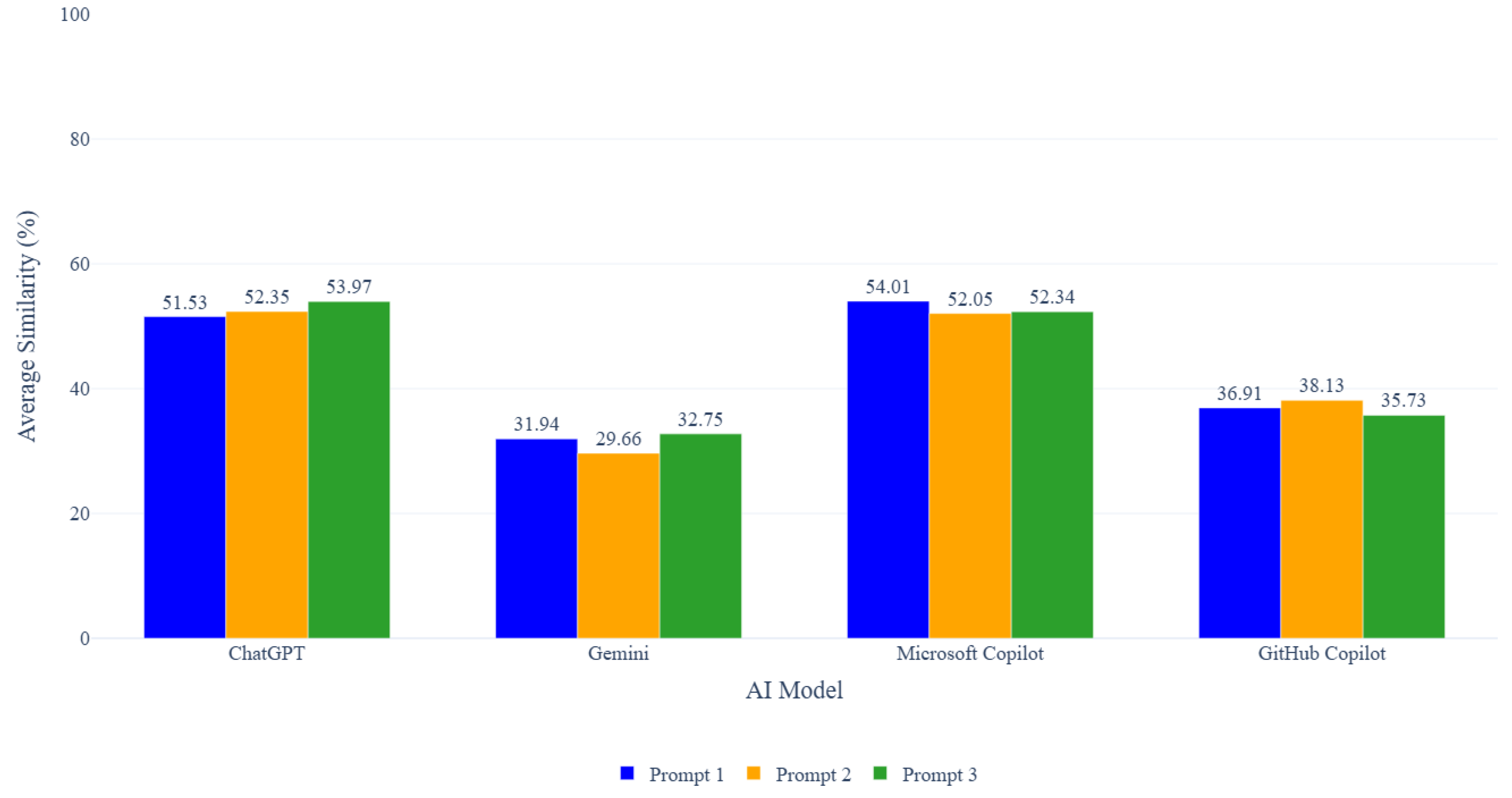

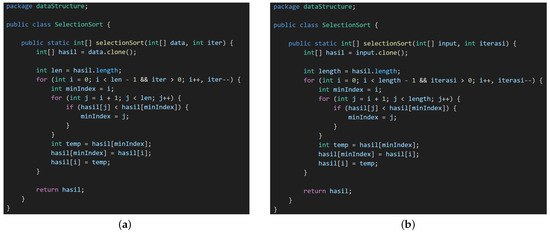

5.5.1. Similarity and Threshold Results

Figure 3 and Table 5 show similarity scores and the number of pairs of students and AI that exceed the threshold. Microsoft Copilot provides the highest overall similarity in Prompt 1 with 54.01%, where the task was to generate a source code that is easy to understand and suitable for beginners, simple and clear based on a provided test code. This prompt condition appears to align well with the Microsoft Copilot generation style, while the other prompts also gave a high similarity.

Figure 3.

Results for Student and AI.

Table 5.

Summary of Student and AI models per prompt.

This was followed by ChatGPT, which is one of the most popular AI models, achieving its highest similarity of 53.97% in Prompt 3 and showing relatively consistent performance across the three prompts. In contrast, Gemini did not produce any pairs exceeding the threshold under all prompts, indicating that its generated codes are less similar to student submissions and remain below the plagiarism detection threshold.

5.5.2. Discussion

After manual inspection, we identified a few student submissions that showed strong evidence of high potential plagiarism involving AI-generated codes, as shown in Table 6. The manual inspection results indicate that the student-written codes exhibited nearly identical program structures, control flows, and even comment styles when compared with codes generated by specific AI models. Such similarities go beyond coincidental resemblance and suggest that the AI-generated code may have been directly reused or only minimally modified before submission.

Table 6.

Student IDs with high potential plagiarism on AI-Generated codes.

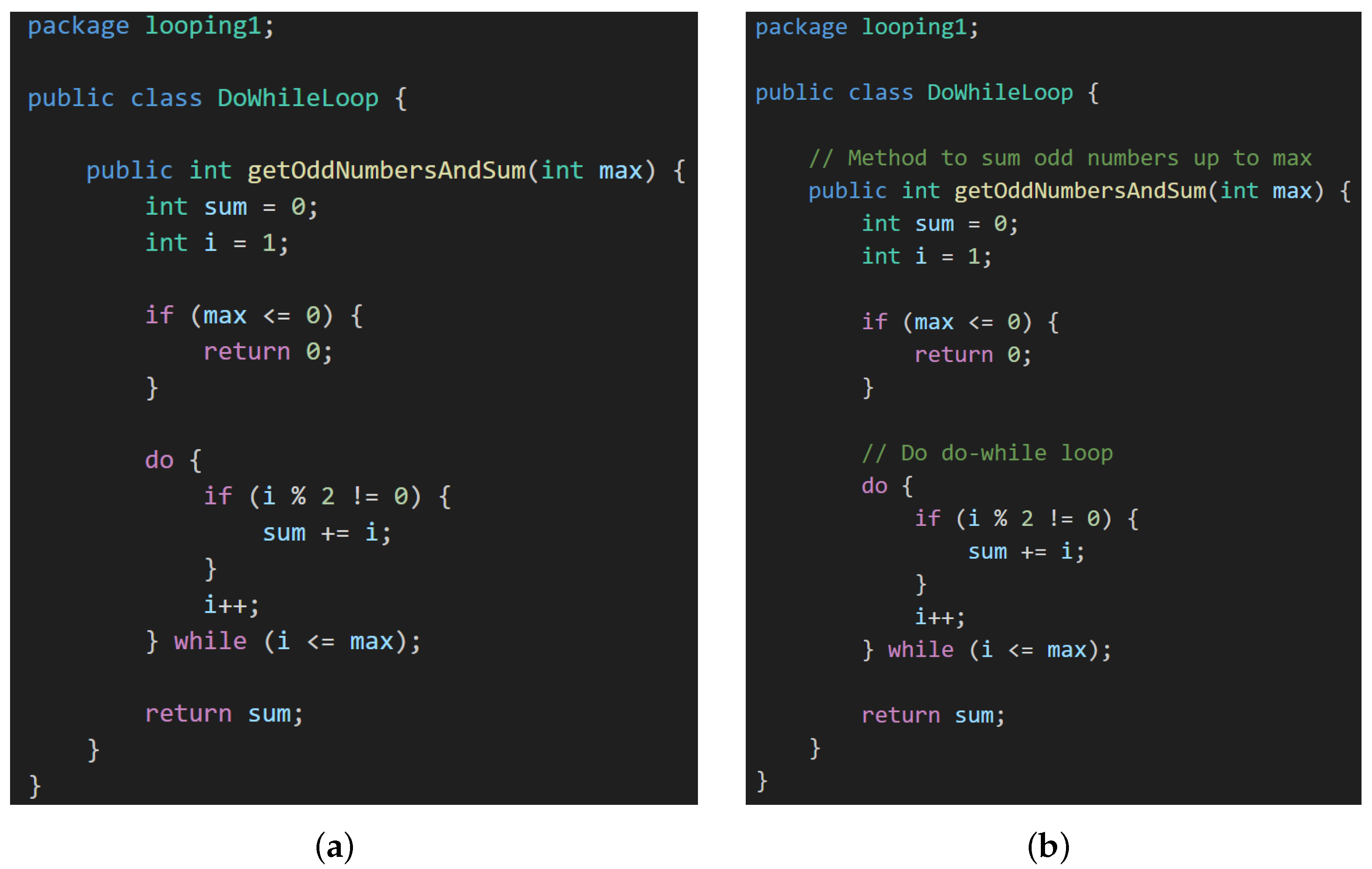

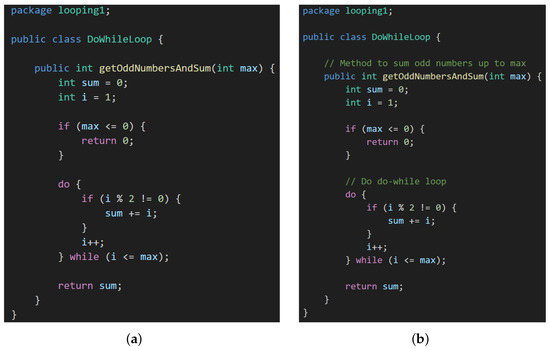

Furthermore, after examining the assignments in which these high-similarity cases occurred, we observed that assignments that were relatively simple and strongly constrained by the provided test codes, such as those involving looping topics, tended to result in AI-generated codes that were highly similar to student submissions. The following figures show an example of a student-written code and an AI-generated code with high similarity from the DoWhileLoop assignment. Figure 4a shows the student submission, while Figure 4b shows the corresponding code generated by Microsoft Copilot using Prompt 1. Due to the limited implementation space, both students and AI models tended to follow the same coding patterns to satisfy the requirements. As a result, AI-generated codes can become highly similar or even identical to student submissions, despite being produced independently.

Figure 4.

Comparison of student-written code and AI-generated code. (a) Student-written code. (b) AI-generated code.

A lot of high similarity codes also may occur in assignments that require long or repetitive code structures. Limited variations in implementations and recurring keywords can inflate the similarity metrics, as the Levenshtein distance method is sensitive to surface-level character differences. As a result, independently written correct solutions may occasionally be flagged as plagiarism, which could lead to negative academic or reputational impacts for students. These findings highlight the importance of treating automated similarity results as preliminary and then corroborating them through careful manual inspections to avoid misjudgments.

Based on this observation, certain students may have directly reused or minimally modified AI-generated code in their submissions. The discovery of AI-specific comment traces will provide valuable insight for future works, where their detection methods can be developed to identify unique characteristic patterns among different AI models. Instructors who wish to generate reference solutions for simple assignments may also effectively utilize AI tools, particularly Microsoft Copilot and ChatGPT, as they produce codes that most closely resemble typical student submissions.

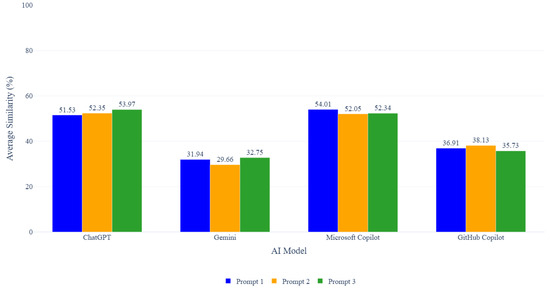

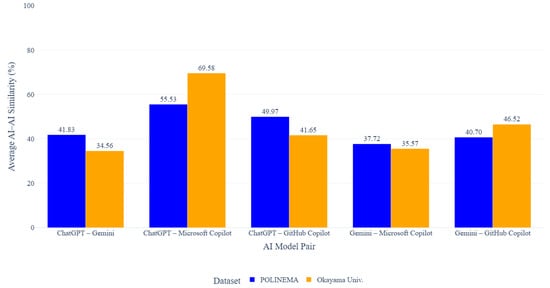

5.6. Results for AI and AI

Figure 5 shows the average similarity across different AI model pairs for the POLINEMA and Okayama University datasets. As shown in the figure, Okayama University assignments are higher than the POLINEMA dataset, particularly for pairs involving ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot, which are able to generate code with high similarity to each other. The relatively simple and highly constrained type of assignments and test codes used in the Okayama University dataset contributes to this observation. Many of the tasks focus on basic programming constructs with limited implementation variation, which reduces the solution space and encourages AI models to generate similar algorithmic structures, control flows, and keyword usage. As a result, multiple AI models tend to produce highly similar code implementations, even when generated independently.

Figure 5.

Results for AI and AI.

Although these pairs appear to have moderately high similarity scores, a closer inspection of the code reveals significant differences in implementation strategies. Table 7 shows that each AI model adapts its strategy based on the given command. There are variations in array handling, iteration control, gap sequence processing, and efficiency measures. This suggests that even when the code looks similar, each AI model actually uses a different approach and logic to solve the problem.

Table 7.

Implementation strategy differences of AI models.

6. Discussion

In this section, we discuss the key findings of our analysis and provide further interpretation of the observed similarity patterns in student and AI-generated codes. We then outline the limitations of this study and present potential directions for future research.

6.1. Interpretation of Results

Based on the experimental results, the proposed threshold selection method can identify meaningful high similarity cases, particularly in student and student code comparisons. By dynamically determining an appropriate threshold for each assignment, the method effectively filters out trivial similarities and highlights code pairs that genuinely warrant further investigation. This enables a more focused closer inspection on student pairs whose similarity scores exceed the threshold, allowing evaluators to assess whether the similarities indicate potential high plagiarism.

Through manual inspection, it was found that several students exhibited high similarity with other students across multiple assignments. This recurring pattern suggests that certain students tend to share or reuse code implementations, indicating a stronger likelihood of actual plagiarism among specific student groups rather than isolated or accidental similarities.

In contrast, although the Okayama University dataset contains a relatively large number of code pairs with high similarity scores, closer inspection revealed that many assignments in this dataset are simple and highly constrained by predefined test codes. As a result, the solution space is limited, and students tend to follow the same straightforward logic even variable naming conventions derived from the test code. Consequently, high similarity scores in this results cannot be interpreted as plagiarism, as they largely stem from the simplicity of the assignments.

Regarding student and AI comparisons, only a small number of students were found to exhibit high similarity with AI-generated codes that could reasonably suggest AI-assisted usage. This finding indicates that within the analyzed datasets, explicit student dependence on AI for code generation appears to be limited.

Further analysis of AI and AI comparisons between two datasets shows that the average similarity was generally higher in the Okayama University dataset. This difference can be explained by the ability of several AI models to generate code that closely resembles typical student submissions for simple and well-defined assignments. It can be concluded that AI-generated code especially from Microsoft Copilot and ChatGPT, can effectively produce solutions that closely resemble student submissions for simple programming assignments. This insight opens opportunities for instructors to leverage AI-generated code as reference implementations or comparison baselines in future work.

6.2. Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights, several limitations should be considered.

First, to avoid misjudgments, the analysis still requires manual inspections to accurately determine whether the detected similarities truly indicate plagiarism or not. Currently, automated similarity measures may be insufficient to capture deeper structural patterns that distinguish coincidental similarity from intentional copying.

Second, the Levenshtein distance used in this study captures only surface-level character differences in the codes, and it does not account for deeper aspects of code logic or structure. As a result, independently written codes may occasionally be flagged as plagiarism, which could lead to negative academic or reputational impacts if misinterpreted.

Third, the performance of AI models is evaluated in terms of similarity behaviors between AI-generated and student-written codes, rather than conventional predictive performance metrics. Consequently, relying on a single surface-level similarity metric will limit the comprehensiveness of AI performance evaluation and highlight the need for careful manual reviews and cautious interpretations of automated results.

Furthermore, the current findings may not fully capture students’ collaborative behaviors or natural variations in coding styles. Therefore, broader validations are needed to better distinguish genuine plagiarism from coincidental similarities in student works.

6.3. Future Work

Building upon the limitations identified in this study, several avenues for future research can be pursued to enhance the effectiveness and generalizability of code similarity and plagiarism detection methods.

First, alternative methods for analyzing code similarity should be explored to reduce reliance on manual inspections and capture deeper semantic and structural patterns. Techniques such as Abstract Syntax Tree (AST)-based comparison, tokenization, structural similarity measures, and embedding-based similarity methods have the potential to identify meaningful relationships between programs beyond surface-level textual edits. By leveraging these approaches, future work should more accurately distinguish between coincidental resemblance and actual plagiarism.

Second, the integration of more advanced Large Language Models (LLMs) as code generators should be considered. Future studies could utilize newer LLMs capable of producing codes using more sophisticated prompts, reflecting the evolving capabilities of AI-assisted programming. Incorporating such models would allow future research to examine how advancements in AI code generation influence similarity patterns and potential plagiarism risks, ensuring that analyses remain relevant as AI technologies continue to evolve.

Third, future work should extend the performance evaluation of AI-generated codes beyond surface-level similarity behaviors by incorporating multiple complementary metrics. Such a multi-metric evaluation framework has the potential to reduce false positives, improve robustness, and better capture meaningful similarities between AI-generated and student-written codes.

Overall, these planned enhancements aim to build upon the current findings and contribute to the development of more reliable, generalizable, and scalable methods for code similarity and plagiarism detection in educational settings.

7. Conclusions

This paper presented the threshold selection method in the code plagiarism checking function using Tukey’s IQR method. This approach allows a threshold to adapt to the similarity score distribution for each assignment, focusing on the upper fence of IQR and 99th percentile, enabling identifications of unusually high similarity scores that may indicate potential plagiarism. Prompts were designed for four different generative AI models to generate answer codes for comparisons with student submissions.

For evaluations, we applied the proposed function to a total of 745 source codes of two datasets. The first dataset consists of 420 answer codes across 12 CWP instances from 35 first-year undergraduate students in the State Polytechnic of Malang, Indonesia (POLINEMA). The second dataset includes 325 answer codes across five CWP assignments from 65 third-year undergraduate students at Okayama University, Japan.

Based on manual inspection, the analysis indicates that some high similarity scores may not solely reflect intentional plagiarism but could also result from collaboration or shared approaches among students. This observation highlights the importance of careful interpretation of similarity metrics and suggests that future enhancements should consider mechanisms to differentiate between collaborative work and true cases of copying.

Detections of plagiarism involving AI-generated codes remain challenging due to the limitations of the similarity methods currently used. In future work, we plan to enhance the function with more advanced techniques capable of automatically identifying plagiarism and providing evidence of the source and type of copied code.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A.D.P. and N.F.; methodology, P.A.D.P.; software, P.A.D.P., K.H.W., S.T.A., M.M., S.A.K., and H.H.S.K.; investigation, M.M.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation P.A.D.P.; writing—review and editing, P.A.D.P., N.F., and S.A.K.; supervision, N.F.; project administration, N.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Varma, S.C.G. The role of Java in modern software development: A comparative analysis with emerging programming languages. Int. J. Emerg. Res. Eng. Technol. 2020, 1, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cass, S. Top Programming Languages 2022. IEEE Spectrum. 2022. Available online: https://spectrum.ieee.org/top-programming-languages-2022 (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Zhu, X.; Yue, Y.; Chen, S. Impact of major backgrounds on student learning achievement: A case study for Java programming course. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funabiki, N.; Matsushima, Y.; Nakanishi, T.; Watanabe, K.; Amano, N. A Java programming learning assistant system using test-driven development method. IAENG Int. J. Comput. Sci. 2013, 40, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Aung, S.T.; Funabiki, N.; Aung, L.H.; Htet, H.; Kyaw, H.H.S.; Sugawara, S. An implementation of Java programming learning assistant system platform using Node.js. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information and Education Technology, Matsue, Japan, 9–11 April 2022; pp. 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Node.js. Available online: https://nodejs.org/en (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Docker. Available online: https://www.docker.com/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- JUnit. Available online: https://junit.org/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Wai, K.H.; Funabiki, N.; Aung, S.T.; Mon, K.T.; Kyaw, H.H.S.; Kao, W.-C. An implementation of answer code validation program for code writing problem in Java programming learning assistant system. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information and Education Technology, Fujisawa, Japan, 18–20 March 2023; pp. 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Htet, E.E.; Wai, K.H.; Aung, S.T.; Funabiki, N.; Lu, X.; Kyaw, H.H.S.; Kao, W.C. Code plagiarism checking function and its application for code writing problem in Java programming learning assistant system. Analytics 2024, 3, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenshtein Distance. Available online: http://www.levenshtein.net/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- OpenAI. ChatGPT. Available online: https://chatgpt.com/ (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- GitHub. GitHub Copilot. Available online: https://github.com/features/copilot (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Jošt, G.; Taneski, V.; Karakatić, S. The impact of large language models on programming education and student learning outcomes. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukiewicz, M. The future of grading programming assignments in education: The role of ChatGPT in automating the assessment and feedback process. Think. Skills Creat. 2024, 52, 101522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S. Role of ChatGPT in computer programming. Mesopotamian J. Comput. Sci. 2023, 2023, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekking, F.M. A Modern Introduction to Probability and Statistics: Understanding Why and How; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hoaglin, D.C. John W. Tukey and data analysis. Stat. Sci. 2003, 18, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google DeepMind. Gemini. Available online: https://gemini.google.com/ (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Microsoft. Microsoft Copilot. Available online: https://copilot.microsoft.com/ (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Dhakal, A.; Paudel, K.; Sigdel, S. An artificial intelligence driven semantic similarity-based pipeline for rapid literature. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.15292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, R.; Dave, M.; Ranga, V. IQR-based approach for DDoS detection and mitigation in SDN. Def. Technol. 2023, 25, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadamuro, G.; Gruppo, M. A distribution-based threshold for determining sentence similarity. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.16675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsharkawi, I.; Sharara, H.; Rafea, A. SViG: A similarity-thresholded approach for Vision Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 19379–19387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Gao, Z.; Chen, B.; Fu, H.; Jiang, S.; Wang, L.; Kou, Y. Study on threshold selection methods in calculation of ocean environmental design parameters. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 39515–39527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, M.A.M.; Masseran, N.; Ibrahim, K. Optimal threshold for Pareto tail modelling in the presence of outliers. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2018, 509, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiao, X.; Xing, W.; Zhu, W. Detecting AI-generated pseudocode in high school online programming courses using an explainable approach. In Proceedings of the 56th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education V. 1, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 26 February–1 March 2025; pp. 701–707. [Google Scholar]

- Bashir, S. Using pseudo-AI submissions for detecting AI-generated code. Front. Comput. Sci. 2025, 7, 1549761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roest, L.; Keuning, H.; Jeuring, J. Next-step hint generation for introductory programming using large language models. In Proceedings of the 26th Australasian Computing Education Conference, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 29 January–2 February 2024; pp. 144–153. [Google Scholar]

- Heickal, H.; Lan, A. Generating feedback-ladders for logical errors in programming using large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.00302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenshtein, V.I. Binary codes for correcting deletion insertion and substitution errors. Sov. Phys. Dokl. 1966, 10, 707–710. [Google Scholar]

- Hubert, M.; Vandervieren, E. An adjusted boxplot for skewed distributions. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2008, 52, 5186–5201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentari, M.; Funabiki, N.; Permatasari, P.A.D.; Kyaw, H.H.S.; Wijayaningrum, V.N.; Fatmawati, T.; Syaifudin, Y.W. An introduction of test code-based approach in algorithms and data structures course with Java programming. In Proceedings of the 2025 Eighth International Conference on Vocational Education and Electrical Engineering (ICVEE), Surabaya, Indonesia, 24–25 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.