Abstract

Existing research in extended reality for education emphasizes learning outcomes rather than the process for developing their materials. Design thinking, a method in Research through Design, which often generates artefacts and systems, can help address this limitation. As such, this paper presents a process for developing 360° videos based on the six steps of the design thinking process with a new step for planning. The authors also propose a novel approach emphasizing co-creation and Indigenous Research Values throughout the process, showing respect, and minimizing misinterpretations, appropriations, and weak translations that often result from recording stories. Presented through an example titled ‘Tipi Teachings’, a digital story rooted in Indigenous Knowledge of Engineering, the authors demonstrate how design thinking and co-creation can be applied to digital storytelling, proposing a procedure which aims to provide guidance to future researchers utilizing digital storytelling, minimizing trial and error, and providing an opportunity for researchers to share and document lessons learned. While the proposed process was created within a Canadian Indigenous research context, and centers Indigenous storybasket values, these values require researchers to listen to and build relationships with the community, incorporating their core values, regardless of whether they directly align with the storybasket values, adjusting the process to their specific context. The decolonial design process aligned with design thinking also considers decolonization globally, rather than locally.

1. Introduction

When it comes to storytelling, certain stories are sacred and must not be shared publicly. Indigenous scholars Shawn Wilson (Opaskwayak Cree) and Thomas King (Cherokee) share that writing them down (or digitizing them) transforms them into something they are not, and this must be avoided as “once a story is told, it is loose in the world” [1]. Through this process, weak translations, misinterpretations, and appropriations cause stories to lose their educational value [2].

Digital storytelling for education, which may be achieved through the development of 360° videos, can allow for stories to come directly from the story holder, minimizing these concerns about translations, misinterpretations, appropriations, and misuse, by relying on the story holder to guide the process and share only those stories which can be revealed in the given context. This ensures the story holder maintains ownership or possession over their knowledge and has control over all aspects of the 360° video including what information appears in the story. When Indigenous Knowledge is involved, OCAP®, a registered trademark of the First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC) [3], is a tool to support data sovereignty which teaches the importance of Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession.

Digital storytelling applies to various immersive technologies in extended reality (XR), which includes augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), and mixed reality (MR). AR overlays virtual objects onto a view of the real world, VR is an entirely virtual environment that blocks out the real world, and MR includes a spectrum between AR and VR that includes elements of both.

Growing interest in these technologies has led to a copious amount of recent literature which studies how XR can be used for education in a wide variety of industries including education, training, aviation, healthcare, military, entertainment, and firefighting [4,5,6,7]. The use of XR for education includes XR for the “exploration of museums, cultural heritage sites, educational content, and historical landmarks” [8]. XR is beneficial in these cases as it can “simulate historical environments, digitally reconstruct artifacts, and provide immersive storytelling” [8], giving viewers a chance to experience otherwise inaccessible content in an immersive and engaging setting. There are examples of VR and AR experiences in both research and industry settings that highlight these use cases; for example, Viking VR [9], Longhouse 5.0 [10], Sweetgrass AR [11], Unceded Territories [12], Ohneganos [13], and ImmersiveLink [14].

XR also fosters high levels of immersion and presence, which prior research has shown to benefit education and learning outcomes. For example, Gao et al. (2021) found that for cultural learning about Christmas, despite there being no significant difference in knowledge learning between VR and non-VR (mobile application) learning experiences, participants positively rated VR over the non-VR learning experiences [15]. This result is consistent with that of Isiaka (2007), who found that teaching agricultural and environmental science through video was as effective as traditional in person teaching [16]. De Medio (2024), however, found that retention and comprehension of information presented in museum exhibitions in VR and AR was higher than in person teaching [17]. This result is similar to that of Ka et al. (2025) who found that VR was “superior to the conventional digital learning method for ‘engagement’, ‘immersion’, ‘motivation’, ‘cognitive benefits’, and ‘perceived learning effectiveness’”, along with higher knowledge retention for understanding 3D structures in engineering [18].

In a systematic review by Santilli et al. (2025), they found that, out of thirty-nine studies looking at immersive VR, 62% of VR experiences had a positive impact compared to traditional teaching methods, 31% had a neutral impact, and 7% had a negative impact [19]. In general, the cases in which VR methods were less successful than traditional teaching methods were when lecture-based learning methodologies made use of the immersion of VR without creating an active learning experience [19].

The high degree of immersion and presence provided by XR teaching methods has the capacity to mitigate psychological burdens on student learning. A study by Wang and Zou (2023) found that due to the lack of motivation and increased anxiety surrounding traditional online education during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is vital to reduce the amount of isolation impacting students in education [20]. The immersive benefits of XR can continually sustain a non-isolated learning environment through increased student motivation and presence, which can limit similar psychological burdens in learning, and, as a result, improve educational outcomes, in the current post-pandemic era.

In short, prior research has shown that XR may improve the learner’s motivation, with motivation being linked to educational outcomes including attention, effort, behaviour, and grades, and may enhance their overall understanding of content [21,22,23,24].

How XR improves the learner’s overall user experience, and to what extent, varies based on the features used. Features such as visual and audio quality, the type of visuals and audio used, the level of interactivity, the system resolution, and the level of system immersion, among other factors, all impact the user experience [8,23,25,26].

Research into the user experience of XR is extensive; however, articles using XR commonly exclude details on the process they used to create their media, instead focusing solely on the research questions, evaluation, and results. Without a standard process for developing the materials shown in XR, including 360° videos, researchers do not have any guidelines for how to design XR media or how the various features of XR impact the user experience. The lack of a standard process also means that there are no lessons learned which offer suggestions for future work.

For example, Gao et al. (2021) published a paper titled “Investigating the Effectiveness of Virtual Reality for Culture Learning” in which they investigated cultural knowledge, behavior, and intercultural sensitivity using a VR scene about Christmas. Gao et al. state that they “designed four different scenes connected by Santa Claus’s guide,” but do not provide details on the process used to design the VR scenes or considerations they made during the design process [15].

Similarly, Fagan et al. (2012) and Cooper et al. (2018) only briefly mention the content of the VR environment used in their studies, focusing more on the results and experience of using VR rather than the VR content itself [27,28].

There are exceptions where the authors discuss the design process in varying levels of detail.

Schofield et al. (2018) published “Viking VR: Designing a Virtual Reality Experience for a Museum” in which they discuss the use of a VR experience to allow museum visitors to “better understand and engage with a particular historical event: the winter camp of the Viking ‘Great Army’ in Torksey, Lincolnshire, UK in CE 872-3.” [9]. Schofield et al. include discussions on composing virtual scenes, linking archaeology and virtual reconstruction, and building the scenes including 3D objects, a script, and sound design. For hardware, Schofield et al. also discussed building a wooden headset that holds a phone and battery pack, making the VR experience accessible to the public with minimal support [9].

While Schofield et al. discussed the process of designing Viking VR, their process is specific to the context within which they were working, and it is not a generalizable process for educational 360° videos.

Previous researchers identified the lack of a generalizable approach and attempted to address this gap with the creation of the I2I method (Immersion and Interaction for Innovation). The I2I method “aims to guide designers of such systems to allow them to create a product that best responds to the needs of their future users, while respecting the best balance of costs, timescales, quality and innovation” [29].

The I2I method focuses on modeling the sensorimotor (physical), cognitive, and functional immersion and interaction through eleven phases.

Currently, success of the I2I method depends on the project leader in an industrial setting. Future work based on the identified limitations aims to adapt the method to co-creation, involving users throughout the process, and addressing challenges with the user experience (UX) by considering factors related to the hardware and software or 3D content, UX being “the research, design, and evaluation of user behavior during interactions with services, products, or systems” [8,29].

Indigenous scholars and authors have highlighted the need for co-creation, among other methodologies and pathways, as a vital aspect of Indigenous frameworks and paradigms needed for research conducted by and for Indigenous Peoples [30,31,32].

This is particularly evident in Jo-Ann Archibald’s four principles of co-operative research in “Indigenous Storywork”: respect, responsibility, reciprocity, and reverence [31] as well as Shawn Wilson’s “Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods,” where he discusses the need for an Indigenous research paradigm, particularly one that centers relationality and relational accountability throughout the entire research process [32].

There is need for development of a process for developing 360° videos in a way that allows for co-creators and user-centered design.

Past work by scholars conducting research with Indigenous Peoples and/or marginalized community groups commonly use participatory design, often referred to as co-design, co-operative design, co-creation, and community design, as a decolonial design process.

In past studies conducted between 2018 and 2024, the use of co-design was either specified by the research question(s) posed by the authors [33,34,35,36,37,38] or was chosen due to the focus on collaborative engagement with communities, their knowledge, practices, and value systems [39,40,41].

The idea of participatory design has also been present throughout studies focused on innovation and collaboration among students in educational institutions, particularly with the involvement of digital technologies, for the goal of fostering co-creation, digital competencies, and other learning skills and tools in educational design [42,43].

Designing educational materials that are creative, collaborative, and appropriately tailored to the field and context it is in, especially those involving emerging technology in today’s technological age, is essential to learning needs and competencies for knowledge sustainability in the future. This was the case in a study conducted by Filipek et al. (2025) who found that there were competency gaps in economics graduates joining the labour market after their education [44]; this same idea has been applied on a broader scale, highlighting the need to design more innovative and specialized educational materials [42,43].

An experimental study by Hu et al. (2024) emphasized similar deficiencies in teaching methods, specifically those used in engineering design courses, and developed an artificial intelligence technological system to help deliver course materials to engineering students [45]. This new, adaptive way of teaching led to an increase of 8.44% in teaching effectiveness when compared to a control group of students using traditional ways of learning [45].

Within existing publications, there is a lack of guidelines for developing 360° videos for digital storytelling, most work focuses on XR outcomes rather than process-oriented XR design. Where guidelines do exist, they lack an emphasis on co-creation which is essential when working with knowledge belonging to a specific community, such as Indigenous Knowledges. This paper aims to address this gap by contributing a process for creating 360° videos for digital storytelling that emphasizes co-creation and includes a focus on Indigenous Knowledges and Indigenous Research Values.

Overall, this paper asks ‘What is a process for developing materials for digital storytelling which is context-sensitive, aligning with Indigenous Research Values and principles for storytelling, and is transferable to other domains?’

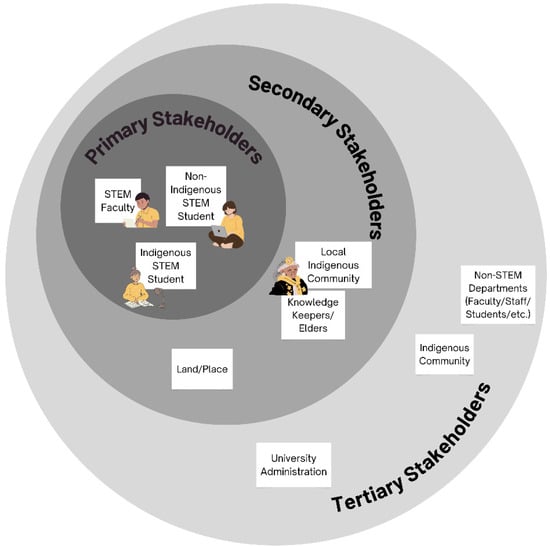

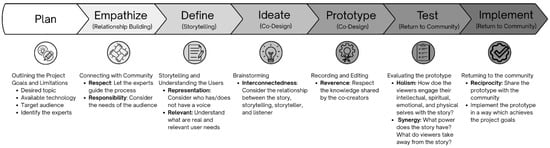

2. Materials and Methods

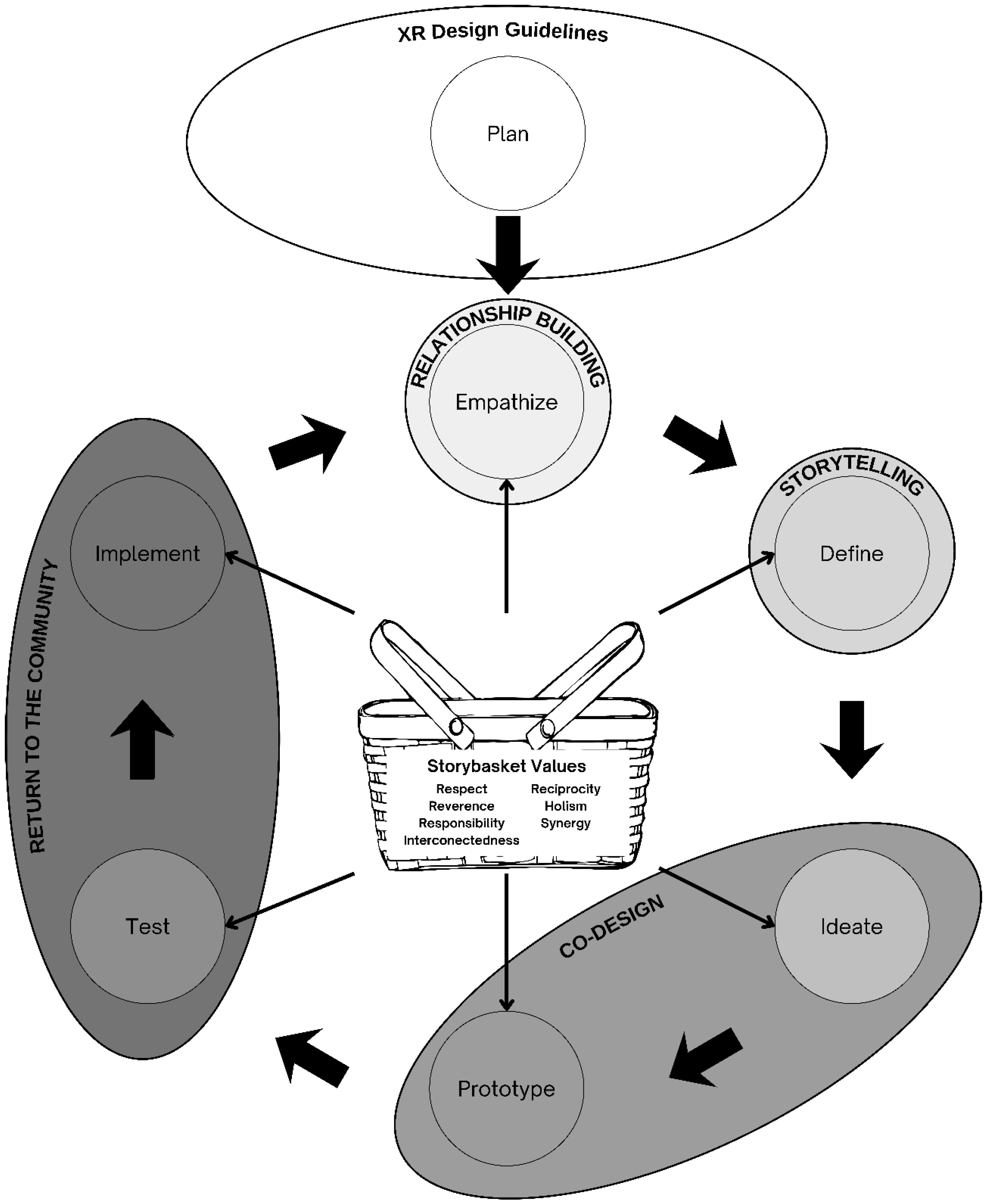

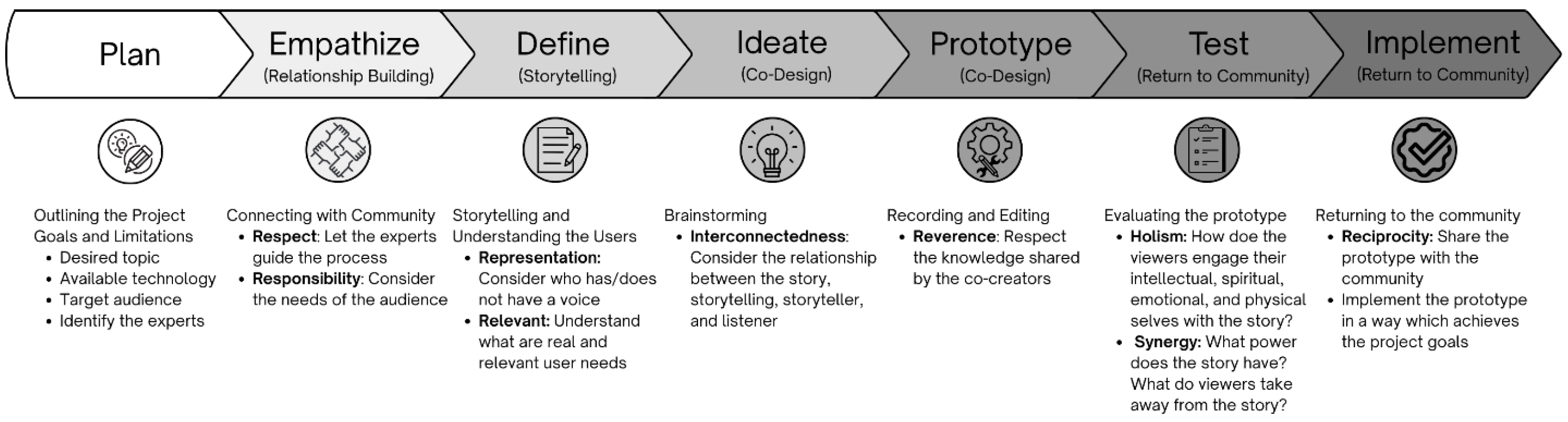

The method used in this paper follows Figure 1. At the center, there are Indigenous Research Values, specifically the storybasket values outlined by Jo-Ann Archibald, and discussed in Section 2.3. These values are central to the process rather than peripheral as they must influence all stages of the cyclical design thinking process—empathize, define, ideate, prototype, test, and implement—discussed in Section 2.1. These six stages of the design thinking process mirror in the four common stages used in past research with Indigenous Communities—relationship building, storytelling, co-design, and a return to the community—also discussed in Section 2.1. An additional stage—plan—adds limitations to the design thinking process based on XR design guidelines, as discussed in Section 2.2. Arrows included between the stages of the design thinking process indicate the iterative nature of designing.

Figure 1.

A visualization of the methodology including design thinking, XR design guidelines, and Indigenous values.

2.1. Design Thinking

“Design is the essence of engineering” [46]. This statement highlights the vital role of design within engineering. This way of knowing through design offers a unique lens through which we can see the world.

Research through Design (RtD) is a framework that builds upon design education and legitimizes design as a method of research. Zimmerman, Stolterman, and Forlizzi (2010) are key scholars in the field and define RtD as “a research approach that employs methods and processes from design practice [sic] as a legitimate method of inquiry” [47].

RtD is common in the Human–Computer Interface (HCI) community, and uses design methods to generate knowledge, often creating artefacts and systems as the output. It “focuses on creating a specific outcome rather than finding the results of a given process” [46].

As a legitimate method of inquiry that often generates artefacts and systems as the output, RtD is a fitting methodology for development of a 360° video, an artefact of the process for use in educational or other settings.

Within RtD, there are various approaches to the design process, but design thinking (also referred to as empathy-based design) is a framework which prioritizes user-centered design (UCD). This includes prioritizing the needs, abilities, priorities, and wants of those impacted by the design (often referred to as users) throughout the entire design process.

There are six stages of the design thinking process; however, it is important to note that these stages are not linear. Design thinking is a cyclical process that requires iteration [48]:

- Empathize: What are the needs, abilities, and wants of the users?

- Define: What problems exist (unmet needs) for the users?

- Ideate: What ideas could address the unmet user needs?

- Prototype: What components of the ideas work, and which do not?

- Test: What feedback do users have for the prototype?

- Implement: How can the vision be put into effect?

In past studies which have conducted research with Indigenous Peoples or marginalized communities using a decolonial design process, there are four common steps: relationship building, storytelling, co-design, and a return to the community [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,49,50]. These studies took place globally, in China, Malaysia, Namibia, Columbia, the United States, Germany, and Australia, highlighting similarities between the Canadian and global landscape when it comes to decolonial design.

Relationship building is the initial step which allows the researchers to (1) understand the protocols and/or rituals of the communities they are working alongside, (2) establish trust and collaboration, and (3) to develop reciprocal relationships which will last throughout and beyond the research project. The relationship building step aligns with the empathize stage of the design thinking process which focuses on understanding the needs, abilities, and wants of the users. Looking at empathizing as relationship building encourages the researchers to focus on involving real users and communities in a way which creates relationships that will last throughout and beyond the research project. At the end of this stage, the researchers should have a list of user needs, abilities, and wants that the community agrees with.

Storytelling is the second step which allows the researchers to continue to connect with communities to further their understanding of the communities’ needs and wishes through the sharing of lived experiences and collective narratives. The storytelling step aligns with the define stage of the design thinking process which looks at what unmet needs and problems exist. Looking at the define stage as storytelling encourages the researchers to continue to involve real users and communities, listening and learning from them directly to understand unmet needs and problems.

Co-design, which is a term often used interchangeably with co-operative design, co-creation, community design, and participatory design, may be defined as “an inclusive design approach that promotes equitable partnerships and mutual learning between multiple stakeholders within a given research context, so together, they can understand the problem space and collectively devise possible pathways for change” (Cumbo & Potts, 2024) [33]. Co-design is the process used by researchers to ideate and prototype alongside community partners, youth, local experts, and others, while emphasizing collaboration, co-creation, and empowerment. The co-design step aligns with the ideate and prototype stages of the design thinking process. The key difference between ideation and prototyping when using co-design is that community members should be core decision-makers in the process. At the end of ideation, the researchers and community should agree on an idea of what to prototype, this includes the technology that will be used and what knowledge or experience will be shared. At the end of the prototyping phase, the researchers and community members will have turned their idea into action, creating, in the case of digital storytelling, a digital medium which everyone consents to share with the target audience.

Return to the community is the last step where researchers are meant to share results of the co-design process with the local community and/or to share the results of the co-design process with the wider community or public. The return to the community aligns with the test and implement stages of the design thinking process which look at collecting feedback on the prototype and eventually putting the design into effect. What makes a return to the community different than the typical test and implement stages of the design process is that the earlier stages have allowed researchers to build strong relationships with the community that continue to be valuable. To test the prototype, researchers should continue to work alongside the community to decide how to test the prototype, such as defining what success looks like. In the implement stage, the community should continue being core decision-makers when deciding who can access the prototype and under what conditions.

While the terminology used varies, these four steps mirror the design thinking process, making design thinking an ideal framework for developing digital storytelling to share Indigenous Knowledges.

In terms of values, design thinking also aligns with Indigenous Research Values, the ‘4 R’s’: Respect, Relevant, Reciprocity, and Responsibility [51]. Other scholars have since added additional ‘R’s’: Relationship, Representation, Relationality, and Refusal [52,53]. Specifically, the design thinking is an appropriate methodological choice for an Indigenous research context as the process is user-centered, values collective expertise, and encourages innovation.

User-centered. The process begins with relationship building, understanding who the users are to address real, not imaginary, needs, and continues with responsibility in mind, ensuring there is ongoing communication with the users/community throughout the entire design process.

Collective expertise. The process is reciprocal and respectful, highlighting the involvement of all involved, including both the research team and users/community.

Encourages innovation. The process allows for creativity in the design process, while ensuring the final prototype is relevant to the desires, needs, and priorities of the users/community.

2.2. XR Design Guidelines

When designing XR, it is beneficial to consider interface design and the overall user experience. Aside from the specifications of the recording equipment and the XR headset itself, one such way XR design guidelines may influence design choices is by looking at the level of immersion and usability, which are key features impacting the user experience. If there is no predetermined technology, the desired level of immersion and usability may factor into the ideation and help determine which technologies would be best. However, if there is predetermined technology which is available, as was the case for Tipi Teachings, it is important to add a step, plan, prior to the design thinking process. Adding a planning stage allows the researchers to identify limitations that may be in place due to the available technology, including limitations on the level of immersion and usability.

At the planning stage, researchers may also define other limitations on the design thinking process such as identifying if there is a desired topic, who the target audience will be, and who the experts are in the space.

2.2.1. Immersion

There are researchers who regard immersion as a technical construct, a physical feature of XR [54,55,56] while others regard immersion as a subjective experience or psychological state overlapping with presence [57].

Following Jung, Lindeman, and Slater, the authors here define immersion as an objective characteristic of the XR system itself impacted by the displays of all sensory modalities and tracking [25,58]. For example, visual stimuli such as screen size, resolution, field-of-view, field-of-regard, stereoscopy, frame rate, refresh rate, head tracking, and realism of lighting all impact the level of immersion [25,54]. In general, “a system that provides rich virtual surroundings, along with the user’s own body movements […] provides a higher level of immersion” [25].

In contrast, presence is a variable of the user’s experience based on experienced realism, involvement, spatial presence, and a sense of being there [59]. As such, presence evaluates the user’s perception of the level of immersion in the later test stage of the design thinking process.

Understanding limitations on immersion and presence, such as the narrative paradox and restricted interactivity, ensures that the researchers can mitigate these challenges of cinematic VR during the design process. For example, for Tipi Teachings, the lack of interactivity meant that the quality of the visuals would be the primary influence on the viewers experience, thus the quality of the camera lenses and VR headset resolution had a significant role in the technology selection.

2.2.2. Usability

While visual stimuli influence the level of immersion, the usability of a system depends on the physical interactions which are possible between the viewer and the digital environment. For example, whether the headset used allows for interactions with the virtual environment through hand gestures or controller input, or whether the viewer can naturally turn their head to move the view of the virtual environment. These built-in ways in which the user has control over their learning have potential benefits on learner motivation and performance [60].

Perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are the subjective measures of the user’s experience of the usability [61]. As such, perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use evaluate the user’s perception of the usability in the later test stage of the design thinking process.

2.3. Indigenous Research Values and Methods

Guidance on storytelling and/or Indigenous Research comes from Indigenous Scholars such as Jo-Ann Archibald (Stó:lō) who wrote “Indigenous Storywork” [31], Kathy Absolon (Anishinaabe) who wrote “Kaandossiwin: How we Come to Know: Indigenous Re-search Methodologies” [30], and Shawn Wilson (Opaskwayak Cree) who wrote “Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods” [32].

Jo-Ann Archibald states that, “During the journey Coyote and I learned that these storywork principles are like strands of a cedar basket. They have distinct shape in themselves, but when they are combined to create story meaning, they are transformed into new designs and also create the background, which shows the beauty of the designs. My learning and the stories contained in this book form a ‘storybasket’ for others to use. Following Stó:lō tradition, I give back what I have learned about storywork, which effectively educates the heart, mind, body, and spirit” [31].

The storybasket she references includes seven interconnected principles that guide the storytelling process: Respect, Reverence, Responsibility, Reciprocity, Interconnectedness, Holism, and Synergy. Table 1 provides a brief explanation of each value.

Table 1.

Jo-Ann Archibald’s storybasket values.

Keeping these values in mind and working to incorporate them throughout the design process helps to create a story which educates the whole listener, their heart, mind, body, and spirit, which is the goal of storytelling.

The following sections will describe the development of the 360° video Tipi Teachings following the six stages of the design thinking process, plus the additional plan stage.

3. Plan

Prior to the first stage of the design thinking process, designing a 360° video begins with planning. During this stage of the design, the researchers must identify any limitations based on the available technology, any boundaries on the topic for the video, who the target audience will be, and potential experts on the topic or area. This will help researchers to communicate needs and limitations with the community in later stages of the design process.

3.1. Technology Available

For Tipi Teachings, the authors had access to the Insta360 Pro 2 Camera (Arashi Vision Inc., Shenzhen, China) [63], purchased second-hand in Ontario, Canada, pictured in Figure 2. This camera features six fish-eye lenses with a bitrate up to 120 Mbps capable of providing an 8 K 3D 360° video recording with a resolution up to 7680 × 7680. The Pro 2 has a battery which lasts approximately one hour of non-stop recording between charges.

Figure 2.

Insta360 Pro 2 camera with attached Zoom H3-VR microphone (Zoom Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

As an alternative, the authors considered the more affordable Insta360 x4 (Arashi Vision Inc., Shenzhen, China); purchased online directly from Insta360, however, this smaller camera, while being easier to transport, utilized only two fish-eye lenses, providing 2D video recording, which decreases the level of immersion.

As storytelling is designed to have listeners being engaged, feeling immersed in the story, and the feeling present in the place where the storytelling is taking place, the increased level of immersion achieved by the 3D video of the Pro 2 camera made it an ideal choice.

The limitations of the Pro 2 include the lack of portability of the camera as well as challenges with picture clarity and video stitching for objects closer than one meter, which is a major challenge for applications requiring these features.

In terms of audio, the Pro 2 has a built-in 4 Mono Mic to provide spatial audio. However, to increase the quality of the audio, the authors paired the Pro 2 with the Zoom X3-VR 360° audio recorder (Zoom Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), purchased online through Zoom [64]. The Zoom X3-VR includes four built-in mics arranged in an ambisonic array to record full-sphere surround sound up to 24 bit/96 kHz. The mic pairs with a wired connection to the Pro 2, aligning the audio to the orientation of the camera, while remaining out of view of the lenses.

To view the final 360° video, the authors had access to the Varjo XR-4, purchased online through Varjo [65], a mixed reality headset with a 120° × 105° field-of-view and 4 K per eye LED display designed for clarity, contrast, and depth perception. The XR-4 includes wireless controllers which allow for the viewer to interact with the virtual environment.

As an alternative, the authors considered the Meta Quest 2 headset. The Quest, a product of Meta, is more affordable, as well as portable, but the lower resolution impacts clarity of the video.

Using this technology, Tipi Teachings is classified as cinematic VR, which Tong et al. define as “a narrative-based virtual reality (VR) experience built on filmed or computer-generated 360-degree videos” [66]. That is, Tipi Teachings will allow users to view 360° videos by naturally turning their head but will not include interactive elements that require use of the controllers.

In this case, usability and the level of immersion are important characteristics of the XR to consider as cinematic VR tends to have a conflict between the viewer’s freedom of choice and the creator’s control over where to look, limiting the usability of the system, which is known as the narrative paradox [67].

The exclusion of interactive elements in the virtual environment limits the usability of the system, leaving viewers with only the ability to control their view of the 360° video by turning their head.

In contrast, the level of immersion is high due to the technical specifications of the chosen technology. The Pro 2 camera and XR-4 provide high resolution, high frame rate, and large field-of-view, combined with the X3-VR which provides high-quality stereoscopic audio.

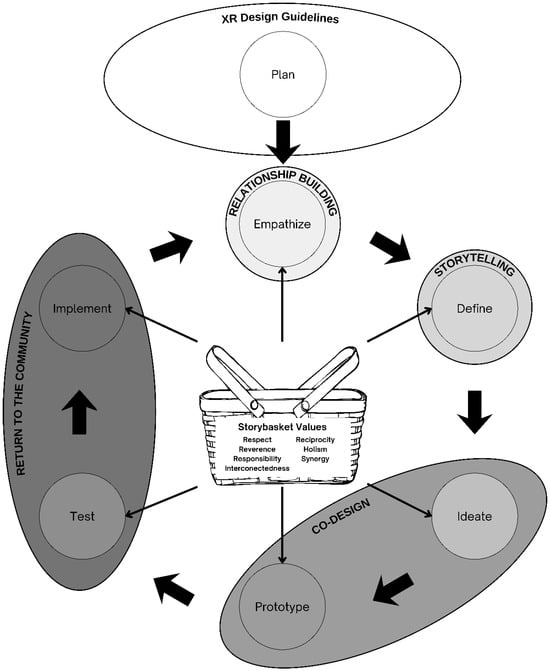

3.2. Desired Topic, Target Audience, and Identified Experts

For Tipi Teachings, prior to connecting with co-designers, the goal of the project was set to be sharing Indigenous Knowledges as they are related to engineering, to all post-secondary students in STEM fields.

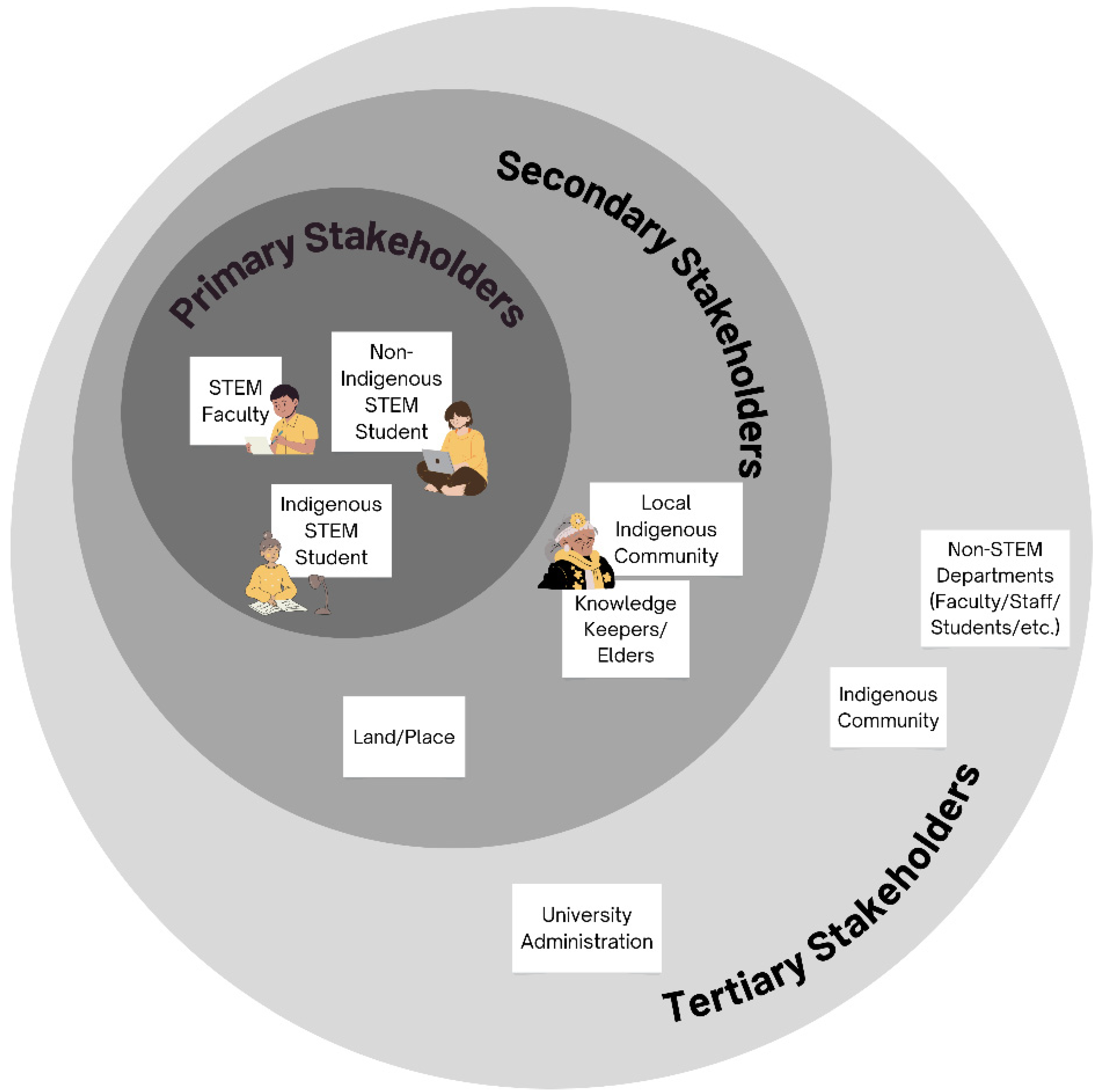

To identify users important to this goal, as shown in Figure 3, the authors developed a stakeholder map. This stakeholder map is not complete, there are missing stakeholders; however, the stakeholder map includes key users within the University and Indigenous Communities that were relevant to the previously defined area: digital storytelling for STEM education.

Figure 3.

Stakeholder map for Tipi Teachings.

The target audience, per the stakeholder map and the project goal, is post-secondary STEM students. This includes non-Indigenous students as well as Indigenous students. As such, individuals without any familiarity with Indigenous Knowledges must be able to easily understand the selected topic.

Similarly, due to this goal, the experts are Indigenous community members with cultural knowledge related to STEM fields. The term ‘expert’ in this paper aligns with conventional terminology in the field of design. In community, speaking to any Elder or Knowledge Keeper, they will state that they are not experts, that they have much left to learn. Specifically, as the authors were located at the University of Waterloo, local community members included Elder Myeengun Henry (Chippewas of the Thames), Knowledge Keeper in the Faculty of Health, Kevin George (Kettle and Stony Point), Associate Director of Indigenous Initiatives at the library, and Savannah Sloat (Haudenosaunee), Manager of Indigenous Initiatives in the Faculty of Science. The lead author had existing relationships with these three individuals.

4. Empathize

The design thinking process begins with Empathize, “conduct[ing] research in order to develop knowledge about what your users do, say, think, and feel” [48].

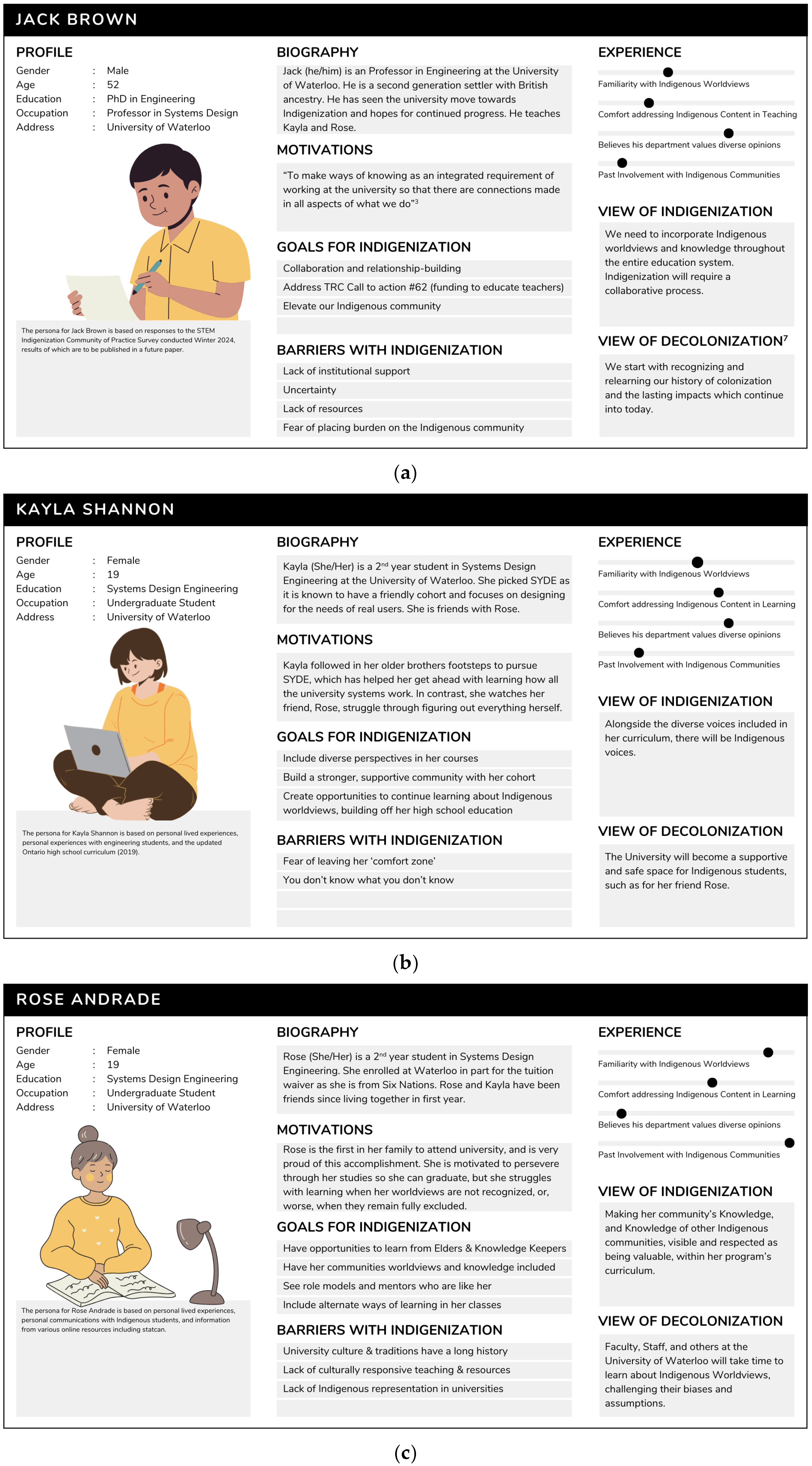

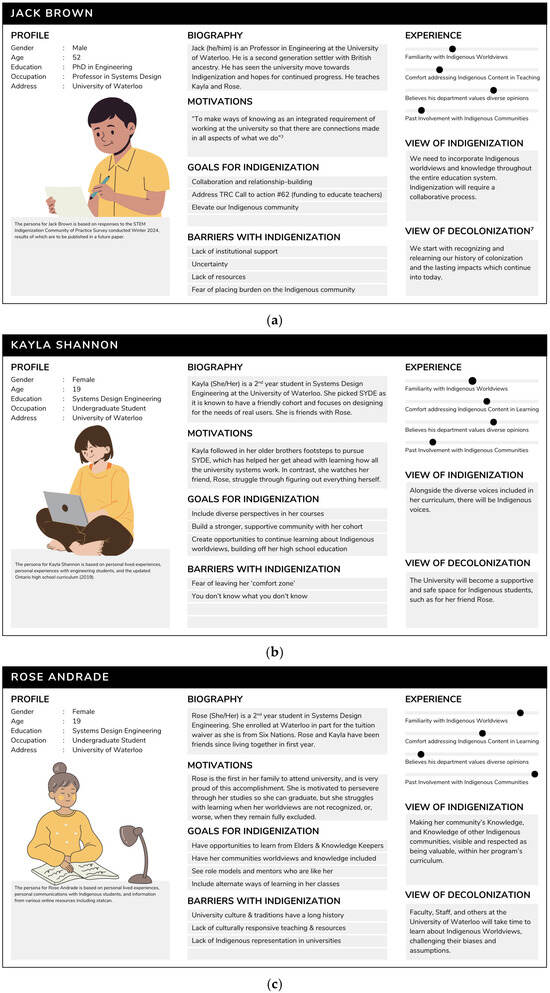

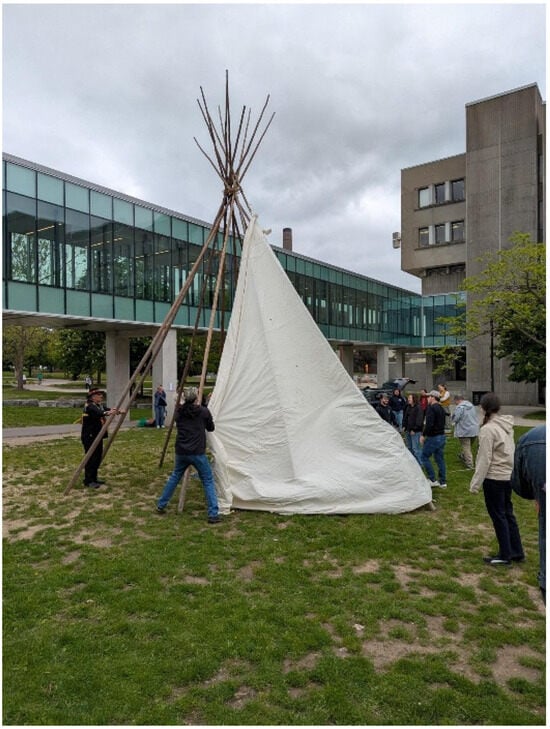

Following the stakeholder map which was developed in the planning stage, to better understand the users, their needs, wants, goals, and frustrations, personas were developed for the key users: STEM Faculty, Non-Indigenous STEM Students, Indigenous STEM Students, and Local Indigenous Knowledge Keepers/Elders, as shown in Figure 4. Relationships and lived experiences of the authors influence these personas.

Figure 4.

Personas for Tipi Teachings: (a) Persona for Jack Brown, STEM Faculty; (b) Persona for Kayla Shannon, Non-Indigenous STEM Student; (c) Persona for Rose Andrade, Indigenous STEM Student; and (d) Persona for Mollie Gibson, Elder.

Jack Brown was the persona developed for the stakeholder group STEM Faculty. Jack’s persona is based on a survey that of STEM Faculty at the University of Waterloo in the Winter of 2024. Results from the survey are the subject of a future paper. Jack, a male professor (age 52) in Systems Design Engineering aims to “incorporate Indigenous worldviews and knowledge throughout the entire education system.” Jack understands that this requires collaboration and relationship-building with the Indigenous community but feels uncertain in how to achieve this. He feels there is a lack of resources and a lack of institutional support. Jack also sees how hard the few Indigenous staff and faculty on campus are working, and fears that this work would place a burden on the Indigenous community.

Kayla Shannon was the persona developed for the stakeholder group Non-Indigenous STEM Student. Kayla is a second-year student in Systems Design Engineering and was based on personal lived experiences as well as fly-on-the-wall observations. Kayla wishes to see diverse perspectives and voices included in her courses, creating opportunities to gain experience about Indigenous worldviews; however, she is afraid to leave her comfort zone. Without experience learning about Indigenous worldviews in the past, Kayla also does not know how to ask for this knowledge from her professors.

Kayla is friends with Rose Andrade; the persona developed for the stakeholder group Indigenous STEM Student. Rose’s persona, like Kayla’s, is based on personal lived experiences as well as fly-on-the-wall observations. Rose is also a second-year student in Systems Design Engineering and comes from Six Nations. Being the first in her family to attend university, Rose is motivated, but when her worldviews are missing, she struggles with learning. She also struggles with the university culture and traditions which have a long and troubled history with Indigenous communities. Rose wants to have opportunities in her classes to learn from Elders and Knowledge Keepers, and to see role models and mentors with whom she can identify.

Mollie Gibson was the persona developed for the stakeholder group Knowledge Keepers/Elders based on personal conversations. Mollie is a Métis Elder who frequently visits the University to support Indigenous students. In her youth, Mollie wanted to attend university, but it was not possible for her. As a result, she aims to support current Indigenous students but knows that her work alone is not enough. She wants to increase educational opportunities for Indigenous youth, and to create opportunities for all students to learn about Indigenous cultures, histories, and worldviews, but knows Indigenous representation and voices are missing.

Through development of these persona’s, the authors were able to identify whose voices are necessary while developing Tipi Teachings, which align with the saying ‘nothing about us, without us.’ For teachings about the Tipi, it is necessary for Indigenous voices to guide the story.

Additionally, the authors identities intersected with those of the personas as the authors include an Indigenous STEM Student, a Non-Indigenous STEM Student, and Non-Indigenous STEM Faculty.

5. Define

The design thinking process continues with Define, “combin[ing] all your research and observ[ing] where your users’ problems exist” [48].

For Tipi Teachings, define began with understanding what user needs had opportunities for improvement within the field of research: digital storytelling for STEM education.

From the perspective of the STEM Faculty, represented by Jack Brown, there are very few Indigenous faculty and researchers who self-identify as Indigenous. There is a need for collaboration and relationship-building with Indigenous community members who can guide the process of Indigenization.

We know that in 2019, 1.9% of faculty and researchers across all fields self-identified as Indigenous [68]. Within engineering specifically, in 2021 there were less than 15 Black and/or Indigenous Engineering faculty members across Ontario [69] and in 2024 less than 1% of PENG holders self-identified as Indigenous [70].

STEM Faculty are cautious about relying on the local Indigenous community members as they fear they will be placing a burden on the Indigenous community. While we need local Indigenous community members to share Indigenous Knowledges, it is not feasible to bring Indigenous community members into the classroom year after year, we cannot rely solely on their time.

This leads to the first key user need: Indigenous Knowledge in the classroom must not place an unreasonable workload on Indigenous community members.

This user need is reflected in the perspective of the Elder, Mollie Gibson, who wants to create opportunities for students to learn about Indigenous cultures, histories, and worldviews in a way that honors Indigenous values and teachings, but who has limited time and whose work is limited by the resources available from universities. However, Mollie recognizes that the slogan ‘nothing about us, without us,’ is essential for guiding Indigenization.

This leads to the second key user need: Indigenous Knowledge in the classroom requires co-creation with Indigenous community members.

From the perspective of the Non-Indigenous STEM Student, Kayla Shannon, there is a desire for diverse perspectives, including those from the Indigenous community, in their courses. However, as identified by the Elder, it is not feasible to bring entire classrooms of students to the land for learning opportunities year after year, again due to the limited number of Indigenous community members who can do this work, but also due to budget, time, and other resource constraints.

Finally, from the perspective of the Indigenous STEM Student, Rose Andrade, their lived experiences give them an understanding that these barriers exist. They see firsthand that there is a lack of Indigenous representation in universities, but they hold onto hope that there can be opportunities to gain experience from Elders and Knowledge Keepers in their classrooms.

This leads to the third key user need: Schools must add Indigenous Knowledge to the classroom, and when doing so must present Indigenous Knowledge in a way that represents Indigenous communities accurately and respectfully.

There is an opportunity to address these user needs within the STEM curriculum through the development of 360° videos. A 360° video ensures that the workload placed on Indigenous community members is reasonable. The community members are not needed to teach the content year after year, but they are instrumental as co-creators throughout the development process, the goal of which is to develop a video that accurately and respectfully represents their voice and may be used without any misinterpretations, translations and appropriations.

6. Ideate

Moving onto Ideate, knowing that a 360° Video for Virtual Reality does have potential to address the user needs, we were then able to focus on “brainstorm[ing] a range of crazy, creative ideas that address the unmet user needs identified in the define phase” [48].

At this stage it was essential to connect with Indigenous community members who could function as co-creators and help the research team to answer three important questions:

- What knowledge do local community members have and are willing to share?

- What knowledge would be recognizable to the target audience?

- Whether the knowledge can be made public and whether the knowledge has recognizable ties into a desired STEM concept?

To answer these questions, the researchers had two separate unstructured conversations with members of the Indigenous community at the University of Waterloo: Elder Myeengun Henry, Knowledge Keeper in the Faculty of Health, and Savannah Sloat, Manager of Indigenous Initiatives in the Faculty of Science. At each meeting, the authors gifted tobacco, following the appropriate protocol when asking for knowledge.

It is important to note that these conversations only occurred with a few members of the Indigenous community at the University of Waterloo, thus, any knowledge collected belongs only to these specific individuals. This knowledge and their opinions do not represent their entire communities, nor does it represent all others who identify as First Nations, Métis, or Inuit Peoples. Pan-Indigenization, the grouping of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Peoples into one broad group of Indigenous Peoples, despite cultural differences, is an issue commonly faced within Indigenization. Despite the small number of co-creators, only two at this stage and a third co-creator added during prototyping, and an Indigenous lead-author is appropriate for RtD as necessary perspectives were included. All co-creators came from diverse backgrounds, and their jobs at the university place them in a role of sharing knowledge with students. Additionally, consensus between the co-creators validated decisions in the ideation and prototyping phases such as the topic, length of video, and teachings that could be publicly shared.

Co-creators had full freedom to decide which knowledge to include and were responsible for guiding the content the authors would record. Having an Indigenous lead-author also benefitted the project as it becomes research ‘by’ rather than research ‘with’ Indigenous Peoples [71].

The questions that guided conversations included:

- What are examples of Indigenous Engineering?

- For these examples of Indigenous Engineering, what do you feel would be educational to share in classrooms?

- What processes, principles, and/or values guide Indigenous storytelling?

Following the conversations, the authors identified which features to include in the digital story to best represent the knowledge and values discussed.

6.1. Examples of Indigenous Engineering for the Classroom

At the first meeting, the team learned from Elder Myeengun Henry that the Tipi is a tradition from our relatives on the Plains; however, it is a notable example of the brilliance of Indigenous Engineering from centuries ago. The Tipi has also become a recognizable symbol of Indigenous Peoples across Turtle Island, thus making it a good example to share in classrooms.

At the second meeting, the team learned again that the Tipi is a recognizable symbol of Indigenous Engineering. Savannah Sloat felt that a view of setting up the Tipi would be educational for non-Indigenous students in STEM classrooms.

As a result of these conversations, the ideate phase of the design thinking process settled on a story that shares Tipi Teachings as the Tipi is an outstanding example of Indigenous Engineering with ties to chemistry, architecture, fluid dynamics, and many other STEM topics which currently exclude Indigenous Knowledge. Specifically, the idea was for the story to include a recording of the Tipi being set-up accompanied by a recording of a conversation that shares teachings from the Tipi that tie in values, such as obedience, respect, and humility, which are again often missing from Western STEM classrooms.

6.2. Guidelines for Indigenous Storytelling

Savannah Sloat shared some thoughts on the storytelling process in general, guiding us towards Indigenous Scholars such as Jo-Ann Archibald who wrote “Indigenous Storywork” [31], Kathy Absolon who wrote “Kaandossiwin: How we Come to Know: Indigenous Re-search Methodologies” [30], and Shawn Wilson who wrote “Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods” [32].

As discussed in the Methods section, Jo-Ann Archibald presents an overview of the storybasket, seven interconnected principles that guide the storytelling process: Respect, Reverence, Responsibility, Reciprocity, Interconnectedness, Holism, and Synergy.

Table 2 presents an overview of the seven values in the storybasket, and a summary of how these values influenced Tipi Teachings.

Table 2.

Storybasket values for 360° videos.

6.3. Technology and Features for 360° Video Development

Following the ideation discussions, the authors returned to the Plan stage to re-evaluate and confirm that the choice of technology can successfully capture the story decided upon during ideation.

Reviewing the values and guidelines for storytelling, the authors decided to prioritize presence, the feeling of being physically present despite watching the Tipi Raising virtually. As discussed in Plan, the chosen camera was the Insta360 Pro 2 camera which can record 3D 360° videos formatted for viewing on a laptop or in VR, simultaneously making the final video more accessible to a wider audience. The 3D video from the Pro 2, compared to the 2D video of the Insta360 x3 camera (Arashi Vision Inc., Shenzhen, China) used for secondary views, offers higher fidelity and thus a higher level of immersion, leading to an increased feeling of presence. The Pro 2 also records with a higher resolution than the x3 (8 K vs. 5.7 K), which increases the visual clarity of the final video, again increasing the level of immersion.

The height of the tripod upon which the Pro 2 camera was placed was evaluated through trial and error to ensure the height of the camera lenses would align with the average viewers eye-level, ideally increasing the feeling of presence by ensuring the final video would be more realistic.

The 360° video is a still video; viewers cannot physically interact with objects in the virtual environment. This is a limitation on usability. However, this also has benefits as it minimizes the experience of simulator sickness without impacting presence; while the video does not include motion, viewers are able to naturally turn their head to change their view.

When developing the 360° video, researchers must consider trade-offs on features in the virtual environment, known as the narrative paradox.

7. Prototype

The next phase is to prototype, to “understand what components of your ideas work, and which do not,” and to “make your ideas tactile” [48].

When prototyping stories or videos, oftentimes designers and researchers rely on storyboarding to outline content. Storyboards can be a great tool, but when it comes to recording Indigenous Knowledges, the Knowledge Keepers and Elders who are co-creating alongside the researcher must guide the story. Teaching Indigenous Knowledges requires teaching from lived experiences and Indigenous voices.

For Tipi Teachings, as researchers, we remained flexible, waiting for the pieces to come together naturally, in their own time. The authors did not rush events to happen sooner, rather we practiced patience, letting the Indigenous community members who we were working alongside provide us with guidance. We also did not guide what knowledge the Indigenous community members should share; rather, we let them guide the conversation and share what they deemed to be valuable and relevant.

The only guidance the authors had prior to recording the prototype was selecting the technology (Insta360 Pro 2 and Insta360 x3) and the topic (Tipi Teachings) alongside the co-creators. Having the technology selected allowed the authors to have ample time to assess the technology and determine the proper settings to use when recording outdoors.

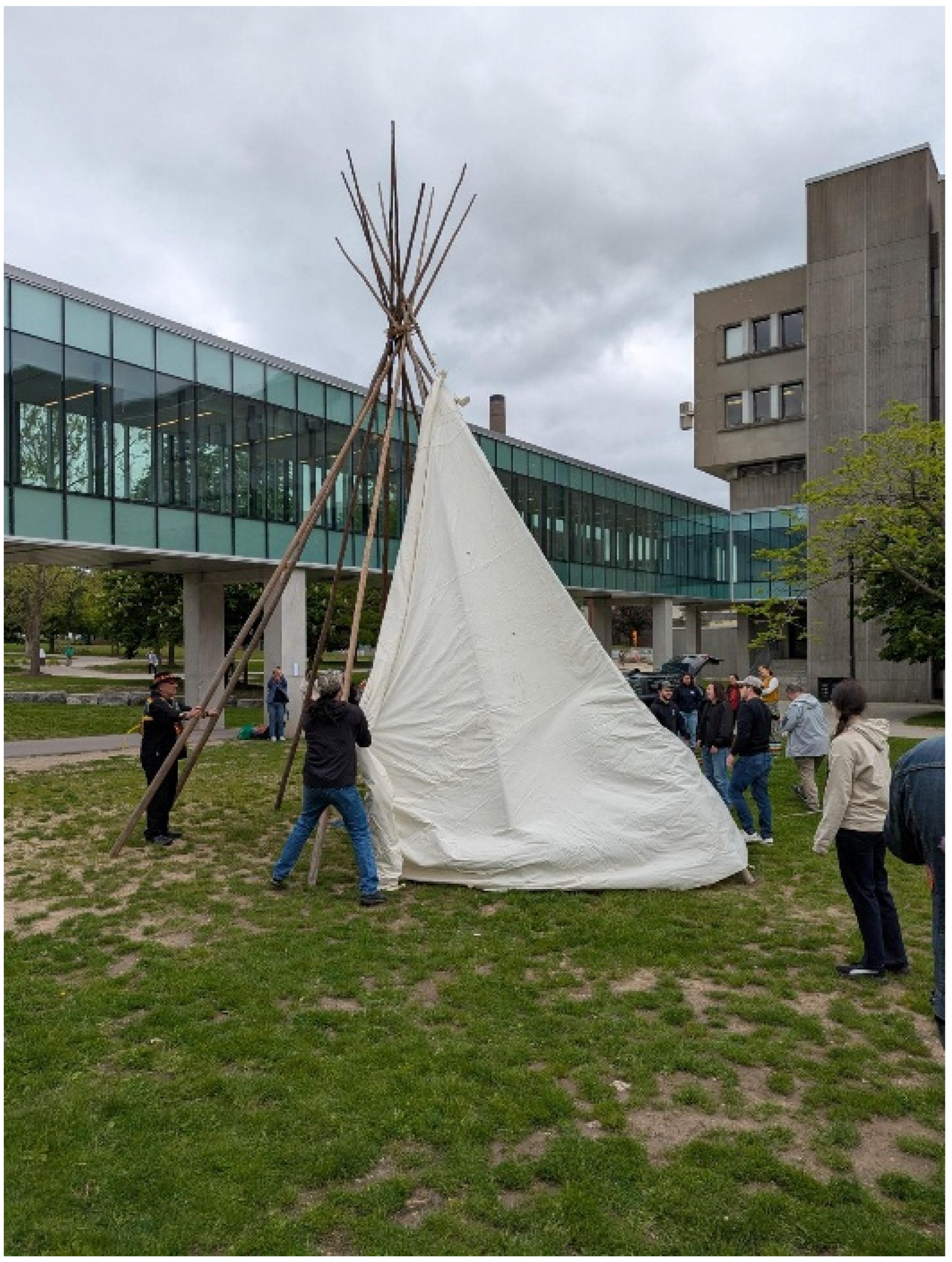

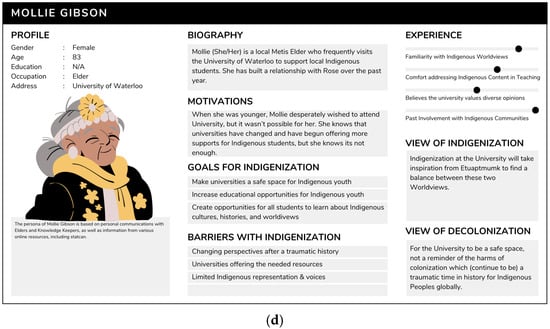

7.1. Tipi Raising

Tipi Teachings came together in the Summer of 2025, when Elder Myeengun Henry, who organized a Tipi Raising on the University of Waterloo campus, provided permission for the event to be recorded. With a week and a half notice, the research team connected with the Office of Research Ethics to confirm what was necessary for recording a public event.

The technology used for Tipi Teachings was the Insta360 Pro 2 camera to capture 3D 360° footage, with the smaller, more portable Insta360 x3 used to capture additional angles in 2D 360° video. For the Tipi Raising, the camera did not use an external mic as the audio during the Tipi Raising was not important for the final video.

On the day of the event, the Pro 2 was set up inside the Tipi, providing a 360° view of the Tipi being set up around the viewer. Figure 5 shows the setup of the camera.

Figure 5.

Recording the Tipi Raising at the University of Waterloo with the Insta360 Pro 2 (Highlighted).

At the event, the authors posted notices of filming, and those involved in the Tipi Raising signed video release forms, following guidance from the Office of Research Ethics. The researcher gave tobacco ties to those helping raise the Tipi a sign of gratitude.

Throughout the entire duration of the Tipi Raising, the authors filmed six video clips on the Pro 2 camera ranging from three minutes to fifteen minutes in length, rather than a single longer video clip. These shorter clips made the final files easier to work with as the authors combined the video clips into a larger video of a conversation on Tipi Teachings. Additional short video clips and pictures of the Tipi Raising from the x3 camera filled in gaps.

Footage from all six Pro 2 video clips were used in the final video, trimmed down to only include main areas of focus from each clip; all video clips used were muted of audio to allow the conversation on Tipi Teachings, discussed in the next section, to be the main source of audio in the final video.

During filming, there were also lessons learned about the Pro 2 camera; namely, the fan must remain running during filming, especially in the summer heat, to prevent the camera from overheating and automatically shutting off. Also, the fan can pose challenges in terms of capturing clear audio, which is a challenge addressed during the next stage of filming.

Before continuing the prototyping with recording a conversation on Tipi Teachings, the lessons learned were brought back to the plan stage to again confirm the choice of technology as being ideal for this project, as well as to the ideate stage to confirm how the story should be presented, within the boundaries presented by the technology.

7.2. Conversation on Teachings

After finishing filming of the Tipi Raising, the authors reached out to Elder Myeengun Henry again, alongside Kevin George, Associate Director of Indigenous Initiatives at the library, to see if they would be willing to share Tipi Teachings. Both Elder Myeengun Henry and Kevin George agreed to share teachings in a recorded conversation.

This conversation took place at the University of Waterloo Indigenous outdoor gathering space named “Skén:nen Tsi Nón:we Tewaya’taróroks|Where we all gather together peacefully.”

Like the Tipi Raising, the technology used was the Insta360 Pro 2 camera. To capture the audio, the authors used the Zoom H3-VR recorder, which can capture spatial audio aligned with the six cameras of the Pro 2 camera. Utilizing an external microphone also helped to address the challenges on audio clarity posed by requiring the Pro 2 fan to remain on during filming.

On the day of the conversation, the Pro 2 was set up as a member of the circle, with the camera at a seated eye-level, allowing the viewer to feel as if they were also sitting in the circle with the authors, Elder Myeengun Henry, and Kevin George. Figure 6 shows the set-up of the camera.

Figure 6.

Recording a conversation on Tipi Teachings at the University of Waterloo with the Insta360 Pro 2 (Highlighted).

Following guidance from the Office of Research Ethics, the authors posted notices of filming and those involved in the conversation on Tipi Teachings signed video release forms. To show gratitude, the authors gifted tobacco ties, as well as a small gift, to Elder Myeengun Henry and Kevin George.

At the end of the conversation, Elder Myeengun Henry gifted the authors with a tobacco tie, thanking us for working to share Indigenous Knowledges within the University; something that is much needed as we collectively work towards Reconciliation.

From the conversation, there was approximately 20 min of recorded footage discussing Tipi Teachings. The entire audio clip appears in the final video, though the video itself alternates between the conversation and the Tipi Raising.

7.3. Technology

Throughout the Tipi Raising and conversation on Tipi Teachings, both the Insta360 Pro 2 camera and the Insta360 x3 camera captured video footage. During the conversation on Tipi Teachings, the Zoom H3-VR recorder microphone captured audio during the conversation.

As all video files from the Pro 2 and x3 were large (approximately 15 GB per video), an external hard drive saved a backup after each step in the video development process in case of unexpected challenges.

During the video development, the authors used various software programs.

First, the Insta360 Stitcher software (v4.0.0) stitched together the footage captured on the Pro 2 [72]. Stitching Pro 2 footage is necessary as the camera captures six different video clips simultaneously, rather than a single 3D 360° video. Insta360 Stitcher stitched all six video clips from the Tipi Raising and the one, twenty-minute video clip of the conversation on Tipi Teachings; the twenty-minute video clip also had the spatial audio extracted as a separate audio file in Stitcher.

Following stitching of the video clips, the next stage is to edit the clips into a final video using the Insta360 Studio software (v.5.7.0) [73]. This software allowed the researchers to interweave the six videos from the Tipi Raising into the Tipi Teachings video to enhance the conversation with visuals from the topics discussed.

To guide the editing process, a storyboard created with paper and pencil served as a guideline for when and how to cut between the Tipi Teachings video and Tipi Raising video clips. It is important to note that the authors created the storyboard after finishing filming, rather than before. This ensured that Elder Myeengun Henry and Kevin George were able to lead where the story would take us.

Minimal editing of the video clips kept the real-world experience and essence of the clips. Edits made did increase the zoom on the videos to ensure the viewer felt they were a part of the circle, rather than watching from outside. Additionally, edits added fading transitions between video clips to follow best practices for VR transitions to minimize simulator sickness. Minimizing simulator sickness was also the reason videos were still; there were no edits made to automatically move or rotate the video, and instead the viewer can naturally turn their head to change their view.

For the audio, additional editing on the extracted spatial audio file enhanced the voices of Elder Myeengun Henry and Kevin George to make their conversation clearer and more audible. Audacity software serves this purpose well as it allows for sampling and removing background noise, which was useful since the camera fan ran throughout the entire filming process to prevent overheating. Additionally, amplifying the audio increased the volume without distorting the audio. Edits were minimal to not compromise the contents or sound of the speakers’ voices.

After finalizing all edits and export settings, the authors exported Tipi Teachings from Studio in a 2:35:1 aspect ratio with maximum quality settings on the H.264 coder-decoder setting. The authors then published Tipi Teachings on DeoVR, a 360° video player for VR headsets, as an ‘unlisted’ video. Tipi Teachings is also available in the Supplementary Materials.

8. Test

Following development of a prototype, the next stage is test, which requires a “return to your users for feedback” [48].

The authors shared Tipi Teachings with Savannah Sloat, Kevin George, and Elder Myeengun Henry, giving them a chance to review the video and offer any feedback/suggestions. It is worth noting that the feedback from the co-creators is informal and limited in scope. This feedback on its own does not validate the effectiveness of Tipi Teachings. There is need for a future controlled experiment to compare the learning outcomes of this digital storytelling process with traditional learning methods.

- Savannah Sloat

In her feedback, Savannah Sloat thought the video looked great. She did not have any suggestions for editing the video but suggested that a transcript to accompany the video could be beneficial. Whether or not subtitles are a possibility in VR, Savannah Sloat felt a transcript could help folks double check for correct language as needed.

While a transcript is not necessary for the purpose of testing Tipi Teachings, it would be essential for ensuring that Tipi Teachings is accessible to a wider audience.

- Kevin George

Kevin George did not provide much feedback but did share that he enjoyed watching the video. He thought it was a unique and fun way of sharing teachings.

- Elder Myeengun Henry

In an informal conversation with Elder Myeengun Henry after he had a chance to view Tipi Teachings, he offered only praise. He appreciated the perspective offered by having placed the camera inside the Tipi while it was being set-up, adding that his favourite part was when the outer canvas wraps around the poles, shown in Figure 7, giving the feeling of the mother wrapping her children in a blanket, as was discussed in the conversation on Tipi Teachings.

Figure 7.

Wrapping the outer canvas around the Tipi poles.

Elder Myeengun Henry was also enthusiastic about opportunities to develop additional videos in the future which share Indigenous Knowledges in a university setting, continuing the relationship that built while developing Tipi Teachings.

9. Implement

The last stage of the design thinking process is implement. This stage is the design doing, to “put the vision into effect” [48].

Use cases for the 360° video depend on the reasons for its creation. A 360° has potential cases in a classroom for education or training, or in the case of Tipi Teachings, it serves as a material for future research. The most important aspect is that how the creators choose to use the video must align with the purpose for its creation. Identifying appropriate use cases requires listening to community and allowing them to provide guidance.

As implementation depends significantly on the motivation for creation of the digital story, it is important to return to the empathize and define stages, reminding oneself of the goals for the project. If the story does not meet a key goal, another iteration of the design process should occur.

For videos like Tipi Teachings which share Indigenous Knowledges, the 360° video must respect the knowledge that shared and not go against the wishes of the community. In doing so, adding guidelines such as the TK (Traditional Knowledge) Labels by Local Contexts can identify the provenance, protocols, and permissions around the story [62].

Provenance labels allow creators to clearly state who ownership of the knowledge, whether it is community knowledge, knowledge belonging to a specific group or individual, and whether the knowledge has been verified by the community, meaning the material aligns with community expectations and protocols. Sharing the genealogy of knowledge is an important part of the oral tradition.

Protocol labels help creators to clearly state usage guidelines for such videos, informing viewers how to be respectful. These usage guidelines may include restrictions on who can access the knowledge or what time of year the knowledge may be shared, for example, within some Indigenous communities, winter is often seen as the time for storytelling as stories shared in the summer may distract the natural world from all the work which must take place.

Permission labels indicate what activities are appropriate for the knowledge and what use cases the community approved. For example, whether the knowledge is for community use only, is for non-commercial use, or is for commercial use.

The TK labels follow an Indigenous context and provide lessons learned for the implement stage as it is essential for researchers to:

- State copyright details and provide proper references to the knowledge and sources used.

- Clearly state usage guidelines for the materials created.

- Indicate to the viewer which activities are appropriate for the knowledge.

10. Discussion

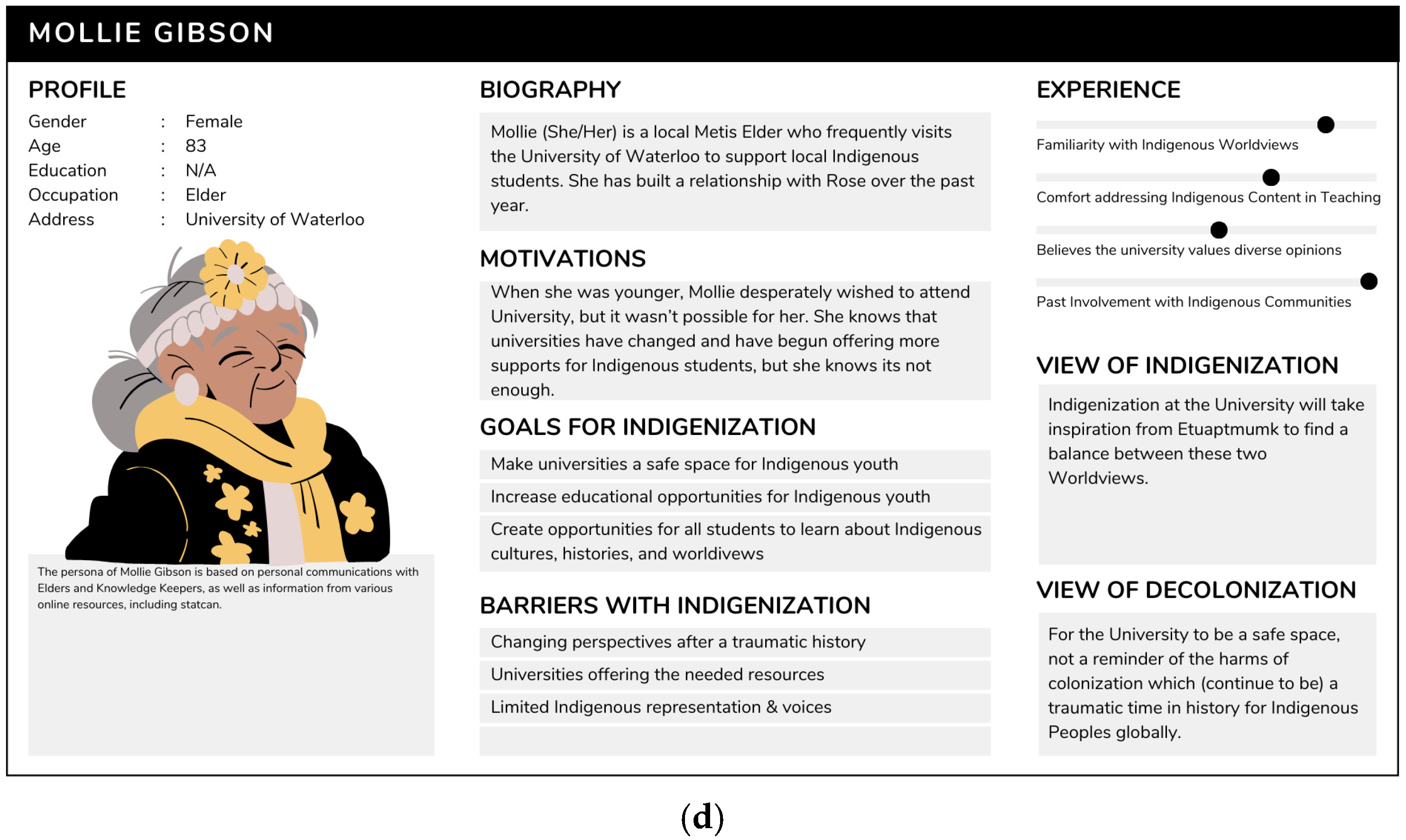

Through the example of developing Tipi Teachings, this paper presents a process for developing 360° videos for digital storytelling in XR visualized in Figure 8. This process follows the six stages of the design thinking process: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, test, and implement, plus an additional step prior to the process—plan—in a way which allows for co-creation and a consideration of user experience. These stages of design thinking align with decolonial design process globally which include four key stages—relationship building, storytelling, co-design, and community feedback—creating a generalizable framework for the proposed process. However, the presented process is context-sensitive, the storybasket values align with Indigenous research contexts across Turtle Island (North America). To transfer this process to other domains, researchers should be aware of which values are most important to the communities in which they are working, which may require modifying the storybasket values. Nonetheless, the storybasket values presented generally impose a respectful process that focuses on building relationships with community, centering community values and ideas, regardless of whether those values directly align with the seven storybasket values.

Figure 8.

A modified design thinking process for developing 360° videos for digital storytelling.

In the first stage, plan, researchers should ask themselves, “What are the goals of this project?”, “Who are the experts and target audience for this project?”, “Does the available technology pose any limitations that must be considered?”, and “Is there a desired topic or area for which the story should focus?”. This stage is important as it allows researchers to identify guiding limitations for the design thinking process.

The plan stage is a unique addition to the design thinking process which aims to help prevent the researchers from over-promising what is possible to the experts as well as from designing a 360° video that does not achieve the project goal.

For Tipi Teachings, the plan stage allowed the authors to clearly communicate to the experts who the target audience is and what type of storytelling was possible with the available technology.

In the second stage, empathize, researchers should begin to build relationships with experts in the community. At this stage, the researchers should consider the values of respect, allowing the experts in the community to guide the process, and responsibility, keeping in mind the real needs of the target audience. Key questions at this stage may include “What do the viewers need or want from a 360° video?”, “How would the viewers choose to engage with a 360° video?”, and “What knowledge does the community have which aligns with the viewer needs and is able to be shared in the given context?”.

The values of respect and responsibility are additions to the empathize stage that comes from Jo-Ann Archibald’s Storybasket.

For Tipi Teachings, the empathize stage had the authors working to understand the target audience, their wants, and needs, through the development of a stakeholder map and personas. In terms of connecting with experts, the authors had pre-existing connections with members of the Indigenous community at the University of Waterloo.

When developing 360° videos it is essential to recognize who you have access to as co-creators and to understand the limitations that may come from that. The authors recognize that they only spoke with three members of the Indigenous Community at the University of Waterloo. These co-creators were able to share their knowledge but cannot speak for the wider Indigenous Community or even the whole of their Nations. For example, as Kevin George shared in Tipi Teachings, the Tipi is a woman lodge, so it would be beneficial to speak with an Elder woman or somebody carrying that female spirit.

When building relationships, it is also necessary to follow proper protocols for ethics as well as protocols expected by the co-creators. Collaborating with the Indigenous Community, the authors ensured they gifted tobacco ties and that co-creators had full knowledge of their responsibilities and what the outcomes of the project would be. The authors also had prior connections to the co-creators, which was beneficial as there was already trust and respect.

In the third stage, define, researchers should focus on storytelling with the experts and understanding which user needs are most relevant, as related to the project goals. At this stage, researchers should consider the values of representation, considering who has been included in the project and given a voice, who has been empowered to share what is relevant and important, and relevance, understanding whether the work that is being done addresses user needs and is connected or appropriate to the project goal. Key questions may include “Who are the experts for this project? Why?”, “Are there any voices missing that should be included?”, and “Which user needs are most relevant to the project?”

The value of relevance is an addition to the define stage that comes from Jo-Ann Archibald’s Storybasket. The value of representation is an addition which comes from “The Six Rs of Indigenous Research” by Ranalda L. Tsosie et al. [53].

For Tipi Teachings, the authors used the define stage to outline three key user needs which were relevant to digital storytelling. These user needs were defined as (1) Indigenous Knowledge in the classroom must not place an unreasonable workload on Indigenous community members, (2) Indigenous Knowledge in the classroom must be co-created by Indigenous community members, and (3) Indigenous Knowledge should be added to the classroom, and when doing so, must be presented in a way that represents Indigenous communities accurately and respectfully. The authors considered the user throughout the design thinking process.

In the fourth stage, ideate, researchers should collaborate with the experts to brainstorm ideas that address the previously defined user needs and fit within the boundaries created by the identified limitations. In this stage, researchers should consider interconnectedness, which is the relationship between the story, storytelling, storyteller, and listener, asking open-ended questions to the experts, focusing more of their time on listening to what the experts have to share. Researchers should also be aware of potential power imbalances and the distribution of decision-making power between themselves and the co-creators.

Interconnectedness is a value that added to the ideate stage from Jo-Ann Archibald’s Storybasket.

For Tipi Teachings, the ideate stage gave the experts freedom to discuss examples of Indigenous Engineering which they felt would be educational to share in classrooms and would be recognizable to the target audience. These experts were able to guide the processes, principles, and values for Indigenous storytelling.

By the end of the ideate stage, it was determined that the 360° video would focus on the Tipi as a topic, including a view of a Tipi raising and a conversation on Tipi teachings.

This relationality, including the geographical and cultural context, cannot be removed from relationships with community and the centering of voices from the community is essential to an Indigenous research framework. However, the framework may easily be adapted to other Indigenous Nations or diverse cultural context by modifying the values at the center of the framework, when necessary, to better reflect the values of the community. Researchers must collaborate with the community directly to determine if the values are representative of their community’s identity. This would allow researchers in other regions to apply the process with integrity. The fifth stage, prototype, is where researchers collaborate with experts to record and edit digital stories. This is the stage where ideas turn into action. It is important to consider the limitations of the chosen technology in terms of usability and the level of immersion.

Reverence is a value which added to the prototype stage from Jo-Ann Archibald’s Storybasket and reminds the researchers that the experts should be guiding the story. Whatever they share is important and should be a piece of the final story. Researchers should have respect for their knowledge.

For Tipi Teachings, including reverence in the prototype meant giving the co-creators the freedom to guide the story, respecting all the shared knowledge. Allowing conversations with co-creators to guide the final video/prototype rather than pre-selecting topics and following a rigid structure allowed the co-creators to decide what knowledge is important to share with the given audience. This also allowed the conversation to flow to topics beyond the author’s awareness, given that the authors are not experts on the chosen topic.

For example, where Elder Myeengun Henry shared that his favourite view in the video was watching the canvas wrap around the poles of the Tipi as a mother blankets her children was something Kevin George felt it was important to bring up, not something the authors had knowledge of beforehand. Thus, if the authors were pre-selecting topics, this would not have been in the video.

This can be a challenge, however, as there is no guarantee as to what knowledge the researchers will be able to collect. If there is a specific topic which must be in the final video, it may be necessary to prepare guiding questions.

The sixth stage is test. This is where researchers can evaluate the created prototype. It is important to consider holism, “How do the viewers engage their intellectual, spiritual, emotional, and physical selves with the story?”, as well as synergy, “What power does the story have?” For Indigenous storytelling, the goal of a story is to engage the whole self—mind, body, and spirit.

Holism and synergy are values added to the test stage from Jo-Ann Archibald’s Storybasket.

For Tipi Teachings, co-creators were the first to view the final video, sharing their thoughts and comments on the digital story. This is a limitation of Tipi Teachings as the test phase currently relies on informal qualitative feedback from the co-creators. In the future, the authors plan to design a controlled experiment comparing the learning outcomes of this digital storytelling process with traditional learning methods among STEM students.

Lastly, the implement stage provides the researchers which a chance to share the digital story with a wider audience whether that is the community from which the knowledge came and/or the target audience for the 360° video. At this stage it is important to consider reciprocity. The relationships built with experts are not one-sided. The involvement of the experts should not only be for the benefit of the researcher’s project. Rather, the involvement of the experts should also benefit themselves and their community. Thus, it is important that researchers share the prototype with the wider community.

For Tipi Teachings, when sharing the prototype back with the co-creators, they expressed interest in continuing the relationship and collaborating to develop additional 360° videos. This demonstrates the importance of relationships and the trust that both parties have in each other.

For Tipi Teachings the implement stage will continue in future research which will investigate the effectiveness of teaching Indigenous Knowledge in STEM through 360° videos in VR. Co-creators will continue to be involved in this and future work which aims to follow this process to develop additional 360° videos for use in VR. This next step is beneficial as researchers must evaluate this design thinking process with a variety of topics and use-cases to ensure the design thinking process for developing 360° videos is generalizable to a wide range of use cases.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17872477, Video S1: Tipi Teachings—Supplemental Video.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.P. and S.C.; Methodology, N.P.; Investigation, N.P. and A.P.; Resources, N.P., A.P. and S.C.; Writing—original draft preparation, N.P. and A.P.; Writing—review and editing, N.P., A.P. and S.C.; Visualization, N.P.; Supervision, N.P. and S.C.; Project Administration, N.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Indigenous and Black Engineering and Technology PhD Project (IBET). This work was also partially supported by the Cornfield/CSTV Co-op Research Funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was not required for this study. There were no human participants, human data, or human tissue. Individuals appearing in the video created are not research participants, and their persons and behaviour are not subject to analysis. For the individuals appearing in the video, video release forms were signed which provided consent to the use of their appearance, image, and voice for the research project, including for use in scientific presentations and/or publications.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not include any human participants. For the individuals appearing in the video, video release forms were signed which provided consent to the use of their appearance, image, and voice for the research project, including for use in scientific presentations and/or publications.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Elder Myeengun Henry (Chippewas of the Thames), Kevin George (Kettle and Stony Point), and Savannah Sloat (Haudenosaunee) for their guidance and support as co-creators of Tipi Teachings. These three individuals assisted with determining what Indigenous Knowledge would best suit the research goal of teaching through 360° video, guiding the authors to Indigenous scholars with relevant works on storytelling, and being a part of filming the actual videos for Tipi Teachings.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OCAP | Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession |

| XR | Extended Reality |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| MR | Mixed Reality |

| I2I | Immersion & Interaction for Innovation |

| RtD | Research Through Design |

| HCI | Human–Computer Interaction |

| UCD | User-Centered Design |

| TK | Traditional Knowledge |

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

References

- Iseke, J. Indigenous Storytelling as Research. Int. Rev. Qual. Res. 2013, 6, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, J.A. Coyote Learns to Make a Storybasket: The Place of First Nations Stories in Education. Simon Fraser University. 1997. Available online: https://summit.sfu.ca/item/7275 (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- The First Nations Principles of OCAP®. The First Nations Information Governance Centre. Available online: https://fnigc.ca/ocap-training/ (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Alasim, F.; Almalki, H. Virtual Simulation-Based Training for Aviation Maintenance Technicians: Recommendations of a Panel of Experts. SAE Int. J. Adv. Curr. Pract. Mobil. 2021, 3, 1285–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]