Abstract

Simulation-based learning experiences (SBLE) are widely used in health professions education to enhance clinical skills, confidence, and decision-making in a safe environment. In Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) programs, peer simulation offers a cost-effective alternative to high-fidelity simulation and standardized patients, though its effectiveness across different instructional formats remains underexplored. This study examined the differences in student confidence in outpatient physical therapy between cohorts of students from three educational delivery methods, which included face-to-face (F2F), virtual instruction (VI), and F2F combined with integrated clinical experiences (F2F + ICE), prior to their first clinical experience. Using a three-group comparative design, 107 students across three academic years (2019, 2020, and 2022) completed pre- and post-course surveys assessing confidence in four domains and interest in outpatient care. A two-way ANCOVA, controlling baseline interest, revealed significant differences in confidence across all cohorts between pre- and post-course assessment time periods (p < 0.001), with no significant differences between cohorts under the various delivery formats at post-course assessment. While the F2F + ICE group demonstrated higher baseline confidence, this difference was not found post-course. Findings suggest that peer simulation effectively improves perceived confidence in outpatient physical therapy regardless of delivery mode. These results support the integration of SBLE in DPT curricula to prepare students for clinical practice and highlight the need for further research across multiple programs.

1. Introduction

Simulation-based learning is a well-established teaching method and a cornerstone of health professions education that provides a safe and controlled environment for developing clinical skills, professional behavior, clinical decision-making, self-confidence, and self-efficacy [1,2,3,4,5]. In physical therapist education, simulation provides students with opportunities to develop psychomotor skills, practice clinical decision-making, and improve communication skills in a low-risk environment, preparing them for entry-level and real-world clinical practice settings such as acute care and outpatient rehabilitation [6,7,8]. Creating a realistic clinical environment enables students to enhance these skills before progressing to clinical education.

Healthcare simulation encompasses several methods, including high-fidelity simulation, standardized patients, and peer role-playing. These approaches have been shown to enhance students’ confidence in clinical skills and decision-making. High-fidelity simulation is an innovative teaching method that involves a high level of realism in the environment, accurate portrayal of the scenario, and elicitation of an emotional response from the learner [9]. High-fidelity simulation, which often utilizes advanced computerized manikins, is widely recognized as an efficacious educational approach to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and clinical practice in the preparation of healthcare professionals.

Standardized patients are well-trained individuals who depict a patient’s role in the healthcare environment [5]. Standardized patients can vary their behaviors based on educational needs to facilitate the development of knowledge, clinical reasoning, professionalism, and communication skills [5].

The cost of high-fidelity simulation and standardized patients can limit their implementation in many programs. Peer simulation, where students assume the roles of patients and clinicians, is a cost-effective alternative that has been shown to enhance student confidence in physical therapy clinical skills [2,10,11]. While peer simulation can lack realism, it has been shown to effectively increase confidence, communication, and clinical reasoning [3].

The emergence of hybrid Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) programs, coupled with the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, has transformed instructional delivery within the profession [12]. Traditional face-to-face (F2F) instruction, once the predominant approach, has been supplemented with virtual delivery of content.

Previous studies on modes of instruction in DPT education have shown mixed findings regarding the validation of efficacy for F2F and virtual instruction. Research supports that virtual delivery of DPT education yields outcomes comparable to those achieved through F2F instruction, with both modalities contributing to improvements in metacognitive awareness, diagnostic accuracy, and psychomotor skill assessment [13]. Similarly, Scott et al. [14] reported no statistically significant differences in student self-efficacy scores across F2F, virtual instruction, and hybrid formats within a pediatric physical therapy curriculum, suggesting that instructional design and mode of delivery may not substantially influence perceived self-efficacy. Virtual education has been shown to improve technical and behavioral skills. A systematic review by Rezayi et al. [15] showed that computerized simulation education had positive effects in improving skills, knowledge, and confidence in physiotherapy students.

Simulation-based learning in physical therapy education has been shown to have mixed results regarding its effects on clinical skills, decision-making, and confidence in clinical settings. A study by Ross and Washmuth [16] showed a decrease in clinical skills confidence scores in DPT students after a simulation and debriefing in four different healthcare settings. However, Ohtake and colleagues [17] showed improvement in DPT student confidence in their technical and behavioral skills after participation in a critical care simulation-based learning experience (SBLE). Delivering SBLE in a virtual format presents challenges, and current literature on this topic remains limited.

Neely et al. [18] found that DPT students exhibited higher levels of confidence in acute care settings following F2F delivery of an acute care peer-simulation course compared to virtual delivery of the same course. Supporting this trend, Veneri and Gannotti [19] observed that mean quiz scores were significantly higher in a traditional F2F course relative to a hybrid format incorporating computer-assisted learning.

In integrated clinical experience (ICE), students participate and engage in supervised patient care that typically occurs as part of a didactic course. In a study by Willis and associates [20], ICE was associated with improved self-assessed clinical reasoning and reflection in third-year DPT students. Furthermore, hybrid and virtual modalities limit the ability of students to participate in ICE that occur outside of the classroom, which have been shown to enhance students’ knowledge, motivation for learning, and preparedness for clinical practice [21,22].

Given the evolving landscape of DPT education and the growing body of evidence supporting the use of SBLE and integrated clinical experiences alongside traditional approaches, it remains essential to further investigate how the delivery method influences students’ perceptions of confidence and readiness for clinical practice. The purpose of this study is to examine differences in student confidence in outpatient physical therapy after a peer simulation course delivered F2F, virtually (VI), and F2F combined with ICEs (F2F + ICE) prior to the DPT students’ first clinical experience. This study examines the confidence of these students with additional consideration of their baseline interest in outpatient physical therapy. Since self-confidence is linked to self-efficacy and student readiness for clinical practice, understanding whether the mode of delivery impacts confidence can inform curriculum design and resource allocation in physical therapy education.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study is non-experimental research using a three-group comparative design examining student cohort perceived confidence and interest in the outpatient physical therapy clinical setting following a peer simulation course delivered in 3 different formats: F2F, VI, and F2F + ICE.

2.2. Methodology

Students from three consecutive cohorts in the second year of a DPT program completed a pre- and post-course survey to self-assess (1) confidence and (2) interest in outpatient physical therapy. All students enrolled in the course were required to complete surveys prior to the course and after the course as part of the course procedures.

2.3. Instrumentation

The survey was adapted from an instrument piloted and used by Bednarek et al. [10] and previously used by Neely et al. [18] in measuring confidence and interest in acute care physical therapy (Table 1). The 5-item self-assessment included one item for overall interest and four items for confidence, which included the following domains: (1) performing safe patient evaluation and treatment, (2) utilizing medical equipment, (3) interpreting physiological data and formulating clinical decisions, and (4) responding to changes in patient status. Questions were scored using a standard 5-point Likert scale with the following description: 1 = not confident, 3 = somewhat confident, 5 = confident.

Table 1.

Survey questions.

The first four items in the survey evaluated students’ perceived confidence, as collected via Likert scale responses. This data was treated as continuous data for interpretation in this study, in alignment with acceptance as stated by previous literature [23,24]. Internal consistency of the survey was found to be excellent (0.914), with a Cronbach’s alpha indicating a high inter-item correlation, suggesting that the items measured a similar construct. Therefore, in consideration of this and as previously performed by Neely et al. [18], a composite score was also calculated for confidence by averaging these four scores to examine this single construct for confidence. These scores were analyzed on two occasions: one before each of the courses was implemented and one after the course was implemented.

2.4. Study Population

A total of 107 DPT students in their second year of an accredited physical therapy curriculum participated in the peer simulation course in 2019, 2020, and 2022. The course preceded the students’ first clinical education experience. At this point in the curriculum, students had not undergone any formal training in the clinical setting; however, students completed observation hours in various settings as part of admission requirements to enter the professional program. Therefore, most students had basic exposure to the outpatient clinical setting prior to entering the program. This course was offered in three different formats in three consecutive years: F2F delivery in 2019 (n = 37), VI in 2020 (n = 35), and F2F + ICE in 2022 (n = 35).

2.5. Intervention

The intervention for this study was a 12-week peer simulation course. During each week, students participated in various peer simulation experiences to prepare them for clinical practice in both the outpatient and inpatient settings (Appendix A). The same core faculty and clinical education faculty members were involved in weekly instruction within the course, and learning objectives were unchanged. This course transpired during the second year (4th semester) of the three-year, nine-semester professional doctoral degree program and immediately preceded the students’ first full-time clinical education experiences. Course objectives and faculty remained the same despite the mode of delivery changing over the three years. The course was delivered in three different modes in 2019, 2020, and 2022, as described in the following sections.

2.6. F2F Peer Simulation Course Design

Prior to completing their first clinical education experience, students at this institution participate in a 12-week peer simulation course. This course is designed to provide a safe and controlled learning environment that allows students the opportunity to practice evaluating and treating simulated patients with diverse medical conditions. The course meets once a week for four hours in the physical therapy clinical skills lab.

Students are assigned patient cases specific to practice settings (Appendix A) and are required to research the condition and be prepared to role-play that “patient” in class. Students are divided into two groups: one portraying the “patient” and the other portraying a “physical therapist.” The “patient” is required to accurately portray the assigned medical condition while the “physical therapist” performs an initial examination, evaluation, and intervention. To enhance realism, students have access to high–low treatment tables and medical equipment.

During each simulation, faculty members rotate among teams to provide real-time feedback and clinical guidance. A formal debrief occurs at the end of each class. Following each scenario, students complete documentation in an electronic medical record system, and the faculty provides feedback and review for accuracy.

2.7. VI Peer Simulation Course Design

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the course was forced to be delivered virtually in 2020. Despite the transition to VI, the faculty in the course remained the same, and the only change to the curriculum was the delivery method. The cohort continued to be divided into “patient” and “physical therapist” groups, with preassigned medical conditions distributed weekly. During designated class time, students would log into Zoom to conduct their patient interviews in 30 min windows. As with the F2F course, students were required to research the assigned medical condition to accurately portray their “patient.” Students were placed in breakout rooms, allowing faculty to rotate to each room for facilitation. Faculty-led debriefs occurred after the completion of the virtual interviews.

Following the interview, students created an outline of the tests and measures deemed appropriate for their “patient.” Students were instructed to video-record themselves performing the procedures on a family member, peer, or friend. Prior to the course, all students confirmed access to an individual who could serve as a simulated “patient.” Students were encouraged to use household items to replicate clinical equipment, such as treatment tables and assistive devices. Videos were then uploaded to the university’s learning management system for faculty review and feedback. Due to the asynchronous nature of the video submissions, a standardized debrief was not feasible. Consistent with the F2F format, students completed electronic documentation for each patient encounter.

2.8. F2F + ICE Peer Simulation Course Design

The course was able to transition back to F2F in 2021. However, faculty noted that because students had limited opportunities for pre-admission observation hours in various settings, students lacked basic knowledge of the physical therapy profession. Students are required to complete 50 observation hours with a licensed physical therapist as part of the admissions process. This requirement was waived during the pandemic (2020–2023) because many healthcare facilities were limiting access to non-essential individuals. Therefore, in 2022, two peer-simulation days were replaced with ICE, one in the acute care hospital setting and the other in an outpatient setting.

During the ICE, students were paired and assigned a specific clinic time with a licensed physical therapist. While in the clinic, students were able to observe and perform pieces of an examination and interventions under the direct supervision of a licensed practitioner. Upon completion of the ICE, students completed an online facilitated discussion post on the university’s learning management system.

2.9. Analysis

For the purposes of this study, only outcomes related to outpatient physical therapy were analyzed. To evaluate the mean score differences in confidence levels in outpatient physical therapy based on the mode of delivery of course content and evaluate the influence of time in the course (beginning of course vs. end of course), as well as the influence of student interest, a factorial, two-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted. Thus, time and instructional delivery mode were both independent variables, with student-perceived confidence being the dependent variable. In addition, examination of the response data found a positive correlation between baseline interest prior to the course and composite confidence score (R = 0.198; p = 0.003). Therefore, student interest level was utilized as a covariate in the ANCOVA. Utilization of a two-way, factorial analysis was necessary due to the inability of investigators to match student pre-course and post-course scores, eliminating the ability to conduct a repeated measures analysis at the student level.

3. Results

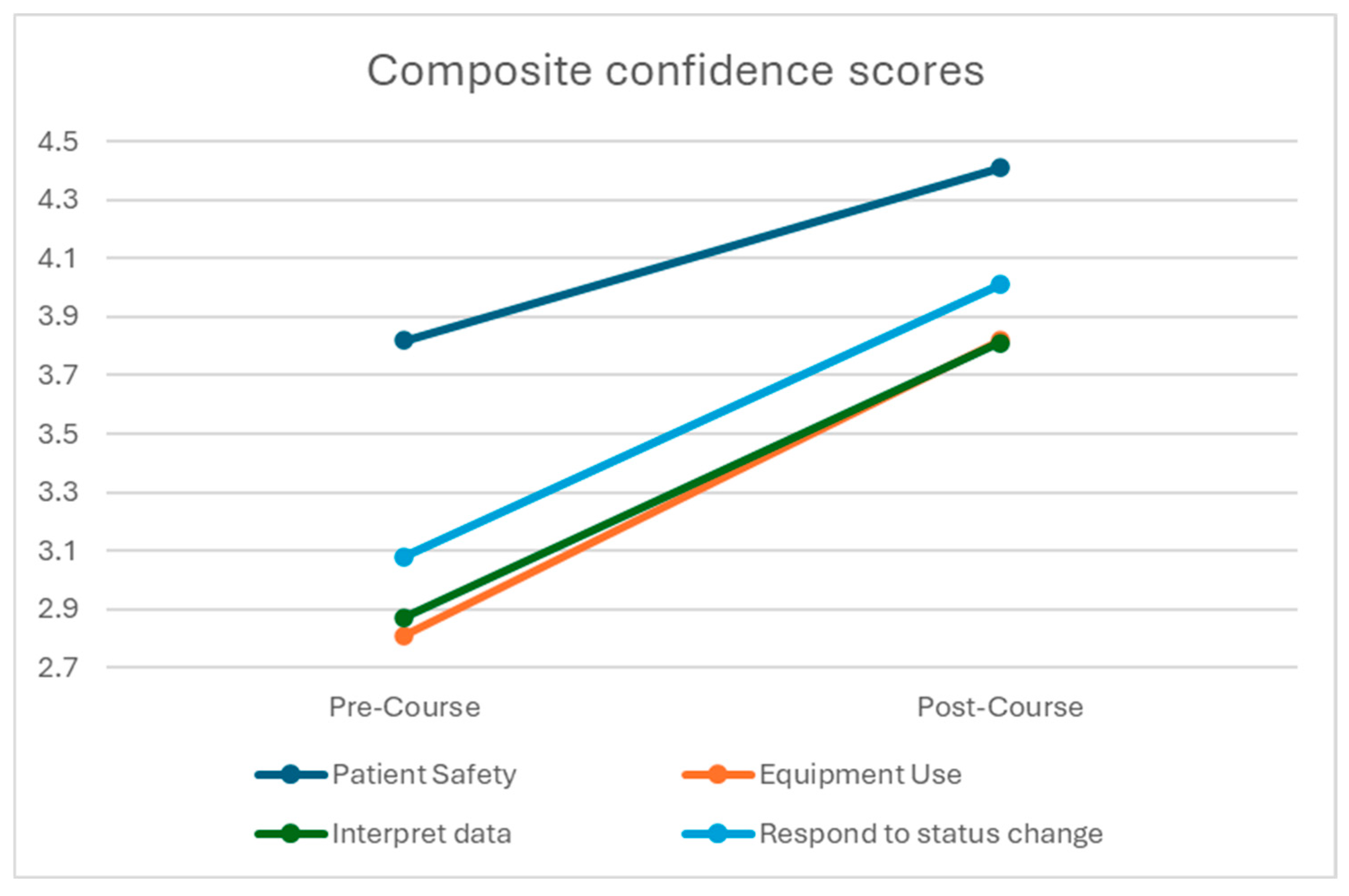

Pre- and post-course assessments were completed by 37 students in the F2F cohort, 35 students in the VI cohort, and 35 students in the F2F + ICE cohort. These data represented a 100% response rate, as survey completion was required per course procedures, which in turn reduced responder bias. Confidence scores across all groups of students from both the pre-course and post-course time periods are identified in Table 2 and Figure 1. All student cohort confidence scores at post-course were statistically significantly greater than at post-course as compared to pre-course. Further, at both pre-course and post-course time periods, student cohort confidence in safety was greater than in all other areas (p < 0.001) with effect sizes of 0.172 at pre-course and 0.107 at post-course, demonstrating a strong effect.

Table 2.

Confidence scores of all students (n = 107).

Figure 1.

Confidence scores of all students (n = 107) in domains.

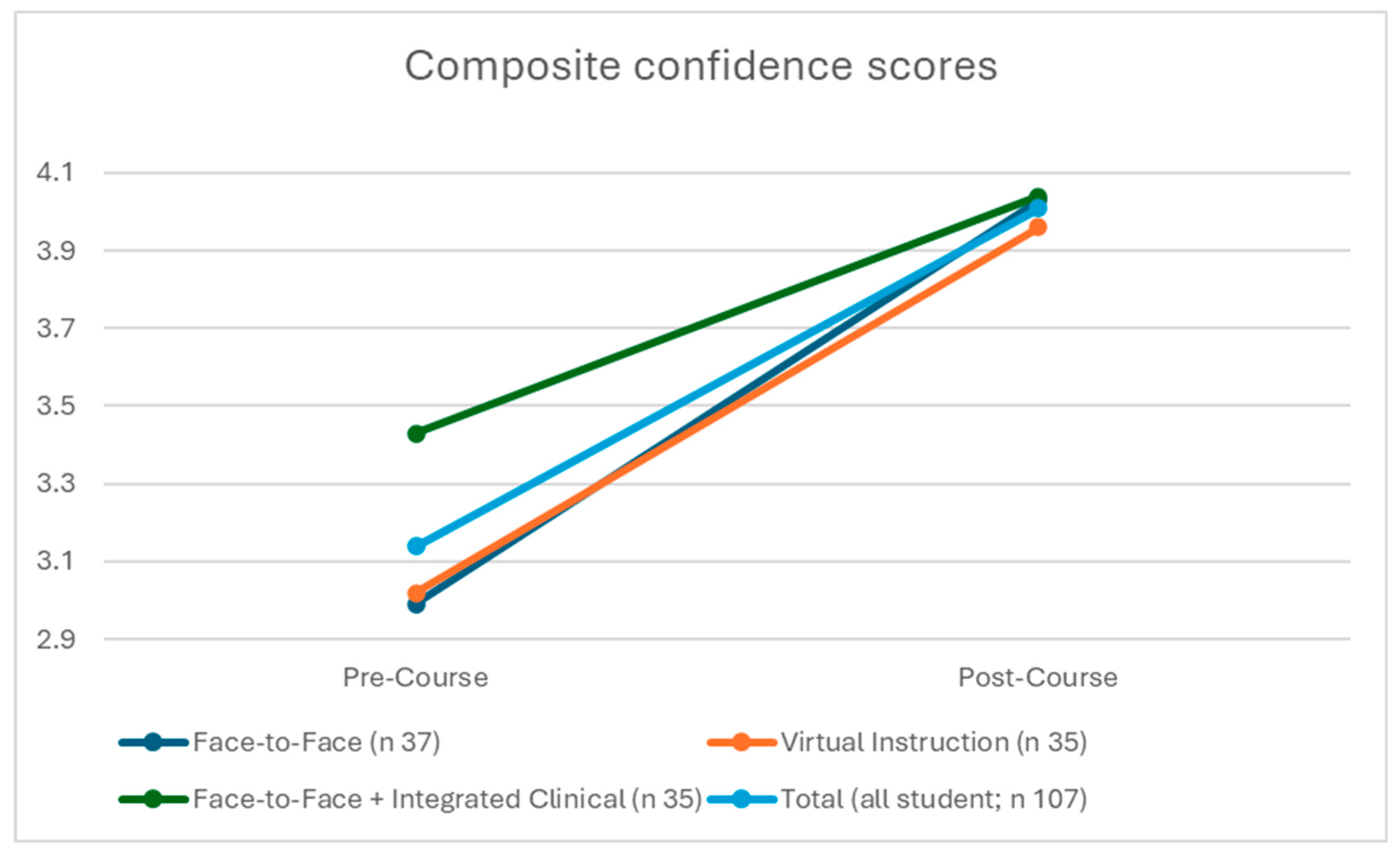

The composite confidence score was then utilized to compare differences in overall student cohort confidence between time periods and between the groups of students based on modes of instruction. The two-way factorial ANCOVA identified a statistically significant covariate effect of interest variable (F = 3.94; p = 0.003; partial η2 = 0.039) and also found statistically significant differences in pre-course to post-course composite confidence scores in all student groups (F = 91.93; p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.298). Confidence at post-course (4.01; 95% CI 3.88–4.13) was significantly greater than at pre-course (3.15; 95% CI 3.02–3.27) assessment across all cohorts from different educational models. Pairwise follow-up assessment revealed that each group’s mean composite confidence scores (F2F; VI; F2F + ICE) were statistically significantly greater (p < 0.05; η2 = 0.071) at post-course assessment as compared to pre-course assessment (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Instructional mode confidence scores.

Upon examination of cohorts (F2F; VI; F2F + ICE), the two-way factorial ANCOVA did not find statistically significant differences between groups (F = 2.98; p = 0.53). While pairwise assessment of these groups revealed statistically significant differences at baseline (F = 4.21; p = 0.017), as indicated in Table 3, pre-course assessment of confidence between the F2F + ICE cohort and each of the other two modes of delivery showed that there were no differences at post-course assessment. Further, there was no statistically significant interaction effect between cohort and test session (pre-course and post-course). The mean confidence change for F2F was 1.03; for VI, it was 0.93; and for F2F + ICE, it was 0.61.

Table 3.

Composite confidence.

The ANCOVA did not find an interaction effect of cohort, which may be due to the higher baseline confidence of the F2F + ICE group (Figure 2). At baseline, the F2F + ICE cohort had a significantly greater composite confidence score (F = 4.21; p = 0.017) than the F2F and VI groups. These statistically significant differences were also identified in the specific domains of the composite score, which include (1) using outpatient medical equipment, (2) interpreting physiological information and making decisions, and (3) responding to a patient’s status. At post-course assessment, however, there were no longer any statistically significant differences in the cohorts’ composite confidence scores or any of their sub-domains.

4. Discussion

All three delivery methods (F2F, F2F + ICE, and VI) across three academic years (2019, 2020, and 2022) found that students in the post-course group held significantly greater confidence than the pre-course group. Students across all three groups reported higher confidence in assessing and treating patients safely, using medical equipment, interpreting physiological information, making clinical decisions, and responding to changes in patient status. These findings suggest that peer simulation showed no detected difference in student-perceived confidence in the outpatient physical therapy setting, regardless of mode of instruction under the given conditions of the specific year (COVID-19 restrictions in 2020). The improvements in the student confidence in this simulation-based learning course are similar to the findings in other studies, such as Neely et al. [18] or Johnson and Kojich [25], where the results show that simulation-based courses are effective in improving the confidence of the students, especially in the acute care clinical setting. Additionally, Neely et al. [18] found improvements in student confidence with a transition to virtual instruction forced by the COVID-19 pandemic, as seen in this study. Peer simulation is a low-cost and effective way of exposing students to different types of clinical scenarios. The improvements in the post-confidence survey in this study are similar to the findings in the study by Miale et al. [26], showing that low-cost simulation-based learning significantly improves students’ self-efficacy.

While visual inspection of the data suggested a potential interaction effect with F2F and VI and confidence gains, statistical analysis did not confirm a significant interaction. These notes indicate that the three different modes of instruction are comparable, despite the observable pattern differences noted in Figure 2. The results of this study coincide with the results of the study from Hartstein et al. [13], showing there are similar improvements in student skills in the classroom with F2F and VI formats, in particular in parts of the DPT professional education curriculum that include primarily orthopedic skills practiced in outpatient clinical settings. The findings of this study are similar to the results of a study of nursing and medicine students by Liaw et al. [27], where the authors found that there was no difference in confidence and performance of the students in VI and those who attended F2F. The findings in this study are in contrast with the results from Neely et al. [18], which showed perceived confidence improvements in the acute care setting were higher in F2F versus VI following a peer simulation course. This may be due to the difference in the acuity and criticality of the patient’s condition in the acute care hospital setting versus the more stable patient conditions seen in an outpatient clinical setting. Additionally, this may be related to students’ limited exposure to the acute care setting prior to entering a DPT program, especially following the pandemic. The findings of this study also reinforce the results of the study from Weddle & Sellheim [22] that including ICE in the curriculum may be beneficial as it improves students’ knowledge and preparation prior to practicing in the actual clinical setting. The F2F + ICE group exhibited significantly higher confidence at baseline compared to the F2F and VI groups; however, this difference was no longer statistically significant at the post-course assessment. It may be possible that the students’ confidence was impacted by having exposure to the clinical setting during ICEs that occurred during the course. Exposure to the clinical setting may have provided students with a more realistic understanding of their abilities, resulting in a recalibration of perceived confidence and a smaller relative increase compared to the other cohorts.

The findings of the study support the move of some DPT programs into a hybrid approach of instruction versus staying in the traditional F2F approach, where a combination of VI, F2F, and ICE is integrated throughout the curriculum. Gagnon et al. [28] found that hybrid programs have good ultimate pass rates and employment rates that are similar to traditional F2F DPT programs with comparable outcomes and costs.

The limitations of the study included a non-random assignment of subjects, and each annual cohort of DPT students was assigned a specific delivery mode of instruction in response to the changing needs during the pandemic. Another limitation of the study is that the student population studied included one physical therapy program in one university in the southeastern region of the United States, limiting the applicability of the study. The sample size of each cohort group may have been too small to determine interaction effects between students. Students in the cohort of 2022 had two hours of small-group ICE, in which they worked in a team supervised by a board-certified therapist to conduct an evaluation and follow-up treatment session. These two additional clinical hours were built into their peer simulation course prior to their first clinical experience and may have impacted their baseline scores.

Future research should include a larger sample size with multiple DPT programs and random assignment of participants to delivery modes. The use of questionnaires with established validity and reliability for assessing student confidence in DPT or other healthcare professions for graduate students would strengthen future studies. Replicating this study across multiple DPT programs or other healthcare programs from various universities and regional locations would increase the generalizability and applicability of the results.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that a peer simulation-based course in outpatient physical therapy may increase student cohort confidence regardless of the mode of delivery, whether it is F2F, VI, or F2F + ICE. A peer simulation course in a DPT curriculum was associated with higher perceived confidence in assessing and treating patients safely, using medical equipment, interpreting physiological information, making clinical decisions, and responding to changes in patient status between the pre-course and post-course time periods. The improvements in student cohort confidence showed no difference across all three years under the different instructional models. While the F2F + ICE cohort had significantly greater baseline confidence compared to the other cohorts, there were no longer any statistically significant differences in confidence after the course. The study showed that each mode of delivery of simulation education was comparable in improving student confidence in an outpatient clinical setting. While each delivery mode showed improvements in confidence levels, it is important to note that the course occurred in the summer of 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. Despite the course being forced to transition to virtual instruction, students continued to report an increase in confidence.

These findings suggest that DPT programs can implement peer SBLE across F2F, virtual, and hybrid instructional formats to positively impact student confidence in outpatient clinical skills. The use of low-cost peer simulation may provide a flexible and scalable curricular strategy to support student confidence and instructional adaptability to adjust teaching strategies to meet the needs of the students and profession. These findings support the integration of SBLE throughout the curriculum in DPT education to foster improved perceived confidence in the outpatient physical therapy clinical setting and provide programs with flexibility to align instructional delivery with evolving educational and clinical practice demands.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C.N., P.P. and M.C.B.; methodology, P.P., R.R. and M.C.B.; software, P.P., M.C.B. and R.R.; validation, P.P.; formal analysis, P.P.; investigation, LL, P.P., M.C.B. and R.R.; resources, L.C.N., P.P., R.R., C.A., L.B. and M.C.B.; data curation, M.C.B., L.C.N., P.P. and R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.B.; writing—review and editing, L.C.N., P.P., R.R., C.A. and M.C.B.; visualization, L.C.N.; supervision, L.C.N.; project administration, L.C.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The University of Central Florida’s IRB determined this study to be exempt (00000536, 5/15/19) because it involves no more than minimal risk and because it was conducted in an established educational setting that specifically involves normal educational practices that are not likely to adversely impact students’ opportunity to learn required educational content.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DPT | Doctor of Physical Therapy |

| F2F | Face-to-face |

| SBLE | Simulation-based learning experiences |

| ICE | Integrated clinical experiences |

| VI | Virtual instruction |

| ANCOVA | Analysis of covariance |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sample Peer Simulation Course Layout.

Table A1.

Sample Peer Simulation Course Layout.

| F2F Instruction | Virtual Instruction | F2F + Virtual + ICE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Introduction to Course Clinical Reasoning | Introduction to Course Clinical Reasoning | Introduction to Course (F2F delivery) Clinical Reasoning, Clinical Practice Guidelines, Integrating Outcome Measures, Discharge Planning, Coding, and Billing (Virtual Delivery) |

| Week 2 | Clinical Practice Guidelines Coding and Billing | Clinical Practice Guidelines Case Presentation: COVID-19 | Case—Outpatient UE |

| Week 3 | Integrating Outcome Measures Discharge Planning | Integrating Outcome Measures | Integrated Clinical Experience—Outpatient |

| Week 4 | Case—Outpatient UE | Coding and Billing Discharge Planning | Case—Outpatient LE |

| Week 5 | Case—Outpatient LE | Case—Outpatient UE | Case—Outpatient Neurologic |

| Week 6 | Case—Outpatient Spine | Case—Outpatient LE | Midterm |

| Week 7 | Case—Outpatient Neuro | Case—Outpatient Spine | Case—Acute Care Ortho |

| Week 8 | Case—Acute Care Ortho | OFF—Holiday | Integrated Clinical Experience—Acute Care |

| Week 9 | Case—Acute Care Ortho | Case—Acute Care Ortho | Case—Acute Care General Medicine |

| Week 10 | Case—Acute Care Neuro | Case—Acute Care Neuro | Case—Acute Care Neurologic |

| Week 11 | Grand Rounds | Grand Rounds | Final Exam |

| Week 12 | Final Exam | Final Exam/White Coat Ceremony | White Coat Ceremony |

F2F = face to face; UE = upper extremity; LE = lower extremity; ICE = integrated clinical experience.

References

- Al-Elq, A. Simulation-based medical teaching and learning. J. Fam. Community Med. 2010, 17, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silberman, N.J.; Litwin, B.; Panzarella, K.J.; Fernandez-Fernandez, A. High Fidelity Human Simulation Improves Physical Therapist Student Self-Efficacy for Acute Care Clinical Practice. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2016, 30, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalwood, N.; Maloney, S.; Cox, N.; Morgan, P. Preparing Physiotherapy Students for Clinical Placement: Student Perceptions of Low-Cost Peer Simulation. A Mixed-Methods Study. Simul. Healthc. J. Soc. Med. Simul. 2018, 13, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macauley, K.; Brudvig, T.J.; Kadakia, M.; Bonneville, M. Systematic Review of Assessments That Evaluate Clinical Decision Making, Clinical Reasoning, and Critical Thinking Changes After Simulation Participation. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2017, 31, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, S.A.; Blackstock, F.C.; Nestel, D.; Keating, J.L. Simulated Patients in Physical Therapy Education: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Phys. Ther. 2016, 96, 1342–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, B.; Carnahan, H.; Herold, J. Use of Simulation Learning Experiences in Physical Therapy Entry-to-Practice Curricula: A Systematic Review. Physiother. Can. 2015, 67, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, M.; Frantz, J.; Bozalek, V. Beyond knowledge and skills: The use of a Delphi study to develop a technology-mediated teaching strategy. BMC Med. Educ. 2013, 13, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockert, B.; Silberman, N.; Rucker, J.; Bradford, J.; Gorman, S.L.; Greenwood, K.C.; Macauley, K.; Nordon-Craft, A.; Quiben, M. Simulation-Based Education in Physical Therapist Professional Education: A Scoping Review. Phys. Ther. 2022, 102, pzac133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, J.; Rossler, K.L. The How When Why of High Fidelity Simulation. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020; Available online: https://europepmc.org/article/MED/32644739 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Bednarek, M.; Downey, P.; Williamson, A.; Ennulat, C. The Use of Human Simulation to Teach Acute Care Skills in a Cardiopulmonary Course: A Case Report. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2014, 28, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, B.; Fethney, J.; Alison, J.; Waters, D.; Gordon, C. Performance in Simulation Is Associated with Clinical Practice Performance in Physical Therapist Students. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2018, 32, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, K.; Young, B.; Bachman, T.; Longbottom, T.; Severin, R.; Walker, M.J. Doctor of Physical Therapy Education in a Hybrid Learning Environment: Reimagining the Possibilities and Navigating a “New Normal”. Phys. Ther. 2020, 100, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartstein, A.J.; Zimney, K.; Verkuyl, M.; Yockey, J.; Berg-Poppe, P. Virtual Reality Instructional Design in Orthopedic Physical Therapy Education: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2022, 36, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K.; Wissinger, J.; Maus, E.; Heathcock, J. Comparing Domain-Specific Self-Efficacy in Pediatric Physical Therapy Education Across Classroom-Based, Online, and Hybrid Curriculum Designs. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2022, 34, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezayi, S.; Shahmoradi, L.; Ghotbi, N.; Choobsaz, H.; Yousefi, M.H.; Pourazadi, S.; Raisi Arda, Z. Computerized Simulation Education on Physiotherapy Students’ Skills and Knowledge: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Washmuth, N. Impact of a Multi-Patient Simulation Event on Physical Therapy Student Confidence: A Quasi-Experimental Study. J. Clin. Educ. Phys. Ther. 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtake, P.J.; Lazarus, M.; Schillo, R.; Rosen, M. Simulation Experience Enhances Physical Therapist Student Confidence in Managing a Patient in the Critical Care Environment. Phys. Ther. 2013, 93, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, L.C.; Beato, M.; Viana, S.; Ayala, S.; Brari, N.; Pabian, P. Student Confidence and Interest in Acute Care Physical Therapy Through Peer Simulation: Does Delivery Mode Matter? A Research Report. J. Acute Care Phys. Ther. 2023, 14, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneri, D.A.; Gannotti, M. A Comparison of Student Outcomes in a Physical Therapy Neurologic Rehabilitation Course Based on Delivery Mode: Hybrid vs Traditional. J. Allied Health 2014, 43, 75E–81E. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, B.W.; Campbell, A.S.; Sayers, S.P.; Gibson, K. Integrated Clinical Experience with Concurrent Problem-Based Learning Is Associated with Increased Clinical Reasoning of Physical Therapy Students in the United States. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2018, 15, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, M.; Birkmeier, M.; Booth, M.; Hack, L.M.; Hartmann, J.; Ingram, D.A.; Jackson-Coty, J.M.; LaFay, V.L.; Wheeler, E.; Soper, S. Recommendations from the Common Terminology Panel of the American Council of Academic Physical Therapy. Phys. Ther. 2018, 98, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weddle, M.L.; Sellheim, D.O. Linking the Classroom and the Clinic: A Model of Integrated Clinical Education for First-Year Physical Therapist Students. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2011, 25, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, I.; Gim, J. Exploration of Likert Scale in Terms of Continuous Variable with Parametric Statistical Methods. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2025, 25, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Artino, A.R., Jr. Analyzing and Interpreting Data from Likert-Type Scales. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2013, 5, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.P.; Kojich, L. Simulation-Based Acute Care Elective Enhances DPT Student Confidence and Interest in Acute Care Without Improving Clinical Decision-Making. J. Acute Care Phys. Ther. 2025, 16, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miale, S.; Silberman, N.; Kupczynski, L. Classroom-Based Simulation: Participants and Observers Perceive High Psychological Fidelity and Improved Clinical Preparedness. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2021, 35, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, S.Y.; Sutini, W.L.; Tan, J.Z.; Levett-Jones, T.; Ashokka, B.; Te Pan, T.L.; Lau, S.T.; Ignacio, J. Desktop Virtual Reality Versus Face-to-Face Simulation for Team-Training on Stress Levels and Performance in Clinical Deterioration: A Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2023, 1, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagnon, K.; Bachman, T.; Garrigues, A. Characteristics, Trends, and Implications of Hybrid Doctor of Physical Therapy Programs in the United States. Phys. Ther. 2025, 105, pzaf043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Academic Society for International Medical Education. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.