Abstract

(1) Background: Physicians and medical students face unique barriers balancing career progression and their mental health. Some medical schools and residency programs have described interventions in which senior clinicians, residents, or medical students disclose their experiences with mental health diagnosis and treatment to peers, students, and those junior in training status. (2) Methods: The authors conducted a scoping review to describe how medical training environments incorporate the self-disclosure of mental health diagnosis and treatment by senior clinicians to junior trainees. They searched six databases and hand-searched references from relevant publications. Following Arksey and O’Malley’s steps for scoping reviews, at least two reviewers independently screened all publications for eligibility and extracted data from included publications. (3) Results: A total of 2326 unique publications were identified; eight were included. Psychiatry was the medical specialty most represented by physician–authors. One publication described an intervention that impacted learner’s behaviors, while the remainder (n = 7) focused on participant satisfaction. (4) Conclusions: Research aims often sought to describe behavior changes. However, most (n = 7) of the literature included in this study did not present the behavioral outcomes of implementing these interventions. This study aims to direct future research into the role of mental health history self-disclosure in medical training environments.

1. Introduction

Studies from around the world have demonstrated that students entering medical school do not report higher rates of suicide and other mental health conditions than matched peers [1,2,3]. However, by the time they begin practicing independently, their rates of suicide, depression, and other mental health concerns exceed those of the general population [2,3,4]. Moreover, they are less likely to seek mental health services when in need for a variety of reasons, including public stigma, difficulty taking time away from training, and concerns about future licensing issues [5,6,7,8]. This trend has serious implications for the health and well-being of medical trainees and poses significant challenges to the sustainability of our healthcare workforce. In response to this pervasive issue, some medical schools and residency programs have begun promoting trainee engagement with mental healthcare and addressing stigma.

Stigma related to mental health has been described as “baked into the system of medicine and medical education [9]”, contributing to treatment avoidance, minimization of the seriousness of a mental health condition, and suicidality [10,11]. To combat this, one approach used by medical schools has been to offer educational interventions in which physicians self-disclose to trainees about their experiences with mental healthcare [12,13,14]. Disclosure by more experienced physicians is believed to help trainees understand that seeking and receiving mental health treatment while remaining a respected and functional clinician is possible [15]. An example of such training includes that at the Pritzker School of Medicine, in which first-year students participated in an all-school event where faculty and peers shared their mental health stories [16]. Another example involves a panel discussion with physicians openly sharing their mental health diagnoses and treatment journeys with medical students [17,18]. Through these interventions, the instructors’ self-disclosures can help bring mental health stigma in medical education to light, normalize help-seeking behaviors, and counteract stereotypes about mental healthcare [19].

While these initiatives are valuable in helping to destigmatize mental healthcare within training programs, they are primarily individual-level interventions and lack objective outcome data. This inconsistency leaves medical educators without clear, actionable guidance on effective implementation strategies or expected outcomes. At present, no comprehensive review has been published to synthesize how these interventions are implemented, the contexts in which they occur, and the measurable outcomes achieved. This gap in the literature increases the risk of medical educators adopting or replicating suboptimal interventions.

To address this gap, we conducted a scoping review to map the existing literature that describes these educational interventions. We aimed to provide a synthesized understanding of the interventions and their implementation, identifying where the field currently stands and offering insights that will help medical educators make informed decisions about the implementation of self-disclosure training.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a scoping review to map the literature describing the self-disclosure of mental health history by senior clinicians to junior clinicians in academic medical training environments, where senior clinicians can represent any role from supervisory staff to more advanced medical students. We used Arksey and O’Malley’s [20] five-step framework to guide our review. We conducted a scoping review because it offers the best opportunity to characterize the existing interventions, and identify existing gaps in the literature.

2.1. Step 1: Identifying the Research Question

Our review was guided by the following research question: What is the state of the literature that describes how medical training environments incorporate the self-disclosure of mental health diagnosis and treatment by senior clinicians or trainees to junior clinicians or trainees? We formulated the research question based on the first author’s (MQ) participation in an education program that uses mental health self-disclosure to medical students as a vehicle for self-reflection about the profession of medicine at large and our awareness of the increase in physicians sharing narrative disclosures of their mental health experiences alongside a growing discussion of ways to improve physician wellness and decrease mental health stigma [21,22,23,24].

2.2. Step 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

On 28 October 2023, an information scientist searched Web of Science (London, UK), Embase (Amsterdam, NED), PubMed (Maryland, USA), PsycInfo (Washington, DC, USA), and EBSCO Open Dissertations (Massachusetts, USA) using a combination of keywords and controlled vocabulary terms optimized for each database. Search terms included, but were not limited to trainee, student, medical student, intern, resident, chief resident, staff, professor, residency, medical school, physician, mental illness, self-disclosure, lived experience, experiential knowledge, wounded healer, expert by experience, and self-report (see Appendix A for complete search strategies). Searches were limited to publications available in the English language due to a lack of translation services. No limit was placed on the publication date to discern possible trends in the frequency of publications. We reviewed the references of all included publications for additional relevant publications. All references were uploaded into Covidence (Melbourne, AUS), a knowledge synthesis management tool [25]. The librarian repeated this process on 6 August 2024 to ensure no relevant publications from the intervening period were missed.

2.3. Step 3: Selecting Studies

We included all publications that described experiences in which senior physicians or senior physician trainees disclosed their lived experience with mental health to more junior physicians or physician trainees in medical training environments. We excluded publications that addressed the disclosure of other medical histories (e.g., disclosure of a knee injury) or disclosure to other audiences and communities. We also excluded personal narratives and publications not focused on disclosure in educational contexts.

All authors participated in the citation screening. MQ screened all titles and abstracts and either LM, DB, or LA served as a second independent reviewer for each article. In cases of disagreement, an author who did not conduct an initial review of the article served as a third reviewer and tie-breaker. In the next phase, we repeated the process, reviewing the full text of the remaining publications to determine if they met the inclusion criteria. Reviewer disagreements were resolved through discussion amongst the full author team until consensus was reached.

2.4. Step 4: Charting the Data

We created a data extraction tool based on a review of the literature and conducted knowledge syntheses. The tool was piloted on four publications and refined based on the team’s discussion. Two authors independently extracted data from each included publication. Extracted data included but were not limited to the publication type, medical specialty of authors, number of participants, stage of training or practice, study aims, Kirkpatrick Level achieved, and outcome measures. We also attempted to identify if any author self-disclosed their experience with mental healthcare in their publication, regardless of whether they disclosed their mental health experience with learners in the described educational activity. Once data extraction was complete, we compared the data and resolved discrepancies via discussion. If author affiliation data (e.g., academic rank) was not included in the publication, we searched for this information on academic or professional websites, which enabled us to find information for all authors.

2.5. Step 5: Collate, Summarize, and Report Results

We discussed the data at regularly scheduled team meetings. We identified themes we observed across the publications, including an analysis of the study objectives, through conceptual content analysis. Our reading of the literature and our educational backgrounds informed our analysis.

3. Results

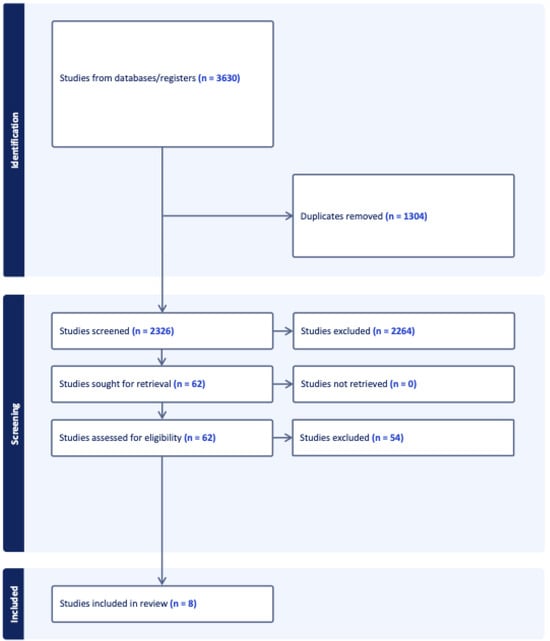

Database searches retrieved 3630 publications. After duplicates were removed, 2326 unique publications were screened. The majority of articles that were excluded did not discuss mental health, did not include self-disclosure, did not involve physicians talking to other physicians of physician trainees, or did not involve training settings. Eight [13,14,15,16,17,18,26,27] met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review (see Figure 1 and Table 1). These eight were published in five journals, with Academic Medicine [15,16], Academic Psychiatry [13,14], and the Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development [17,18] being represented the most frequently (n = 2 each). All of the journals were peer-reviewed and indexed in Clarivate’s Web of Knowledge. Most were published after 2019 (n = 6, 75%), with publication dates ranging from 2013 to 2023. The publications included five empirical studies [14,15,16,17,18], two conference abstracts [26,27], and one case report [13].

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram.

Table 1.

Publication interventions and reported aims.

Author teams ranged from two to nine members. There were 43 total authors, including medical students (n = 17), physicians (n = 15), resident physicians (n = 5), academic professionals who have appointments at medical schools and teaching hospitals (n = 4), a healthcare consultant (n = 1), and other clinicians (n = 1). Nine physicians or residents were identified as psychiatrists, and five as internal medicine physicians. Other represented fields included obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, neurology, family medicine, and anesthesia. Three authors were each listed on two different publications [17,18] and each authorship was considered independently for these calculations.

The publications described seven interventions. Two described the same intervention at different time points, with variation in the methods and components [17,18]. Most interventions targeted only medical students (n = 4; 50%) [14,17,18,26] or residents (n = 1; 12.5%) [15]. One multi-component intervention offered specific components to medical students (e.g., the panel discussion), while offering different components to the entire academic health center (e.g., the story slam and social media campaign) [16]. Another intervention could be accessed by all community members [13]. One abstract did not clearly identify the intervention’s target population; it was offered multiple times in a variety of settings, but the abstract included limited information about the intervention itself [27].

The publications were predominantly based in the United States (US, n = 5), with two at a US medical school’s campus in Israel (i.e., Sackler School of Medicine New York State/American Program of Tel Aviv University) [17,18]. Three publications (37.5%) referenced medical licensing in the US in relation to the role of stigma when physicians seek mental health treatment [15,17,18]. Of the three that mentioned licensing, one described an intervention targeting residents [15] and two described different iterations of the same intervention for medical students [17,18].

Four interventions [14,16,17,18] (50%) used multi-component strategies, three (37.5%) offered a single component [13,15,27], and one abstract did not provide enough detail to fully characterize the intervention [26]. In four interventions (50%), medical students disclosed their mental health history to peers or junior medical students [13,14,16,26]. In four interventions (50%), physicians no longer in training disclosed their mental health history to residents or medical students [15,16,17,18]. Only Brenner’s research involved physician residents sharing their mental health history [16]. In Pillai’s research, we were unable to determine if non-trainee physicians disclosed their mental health history [13]; and Hankir did not characterize those who disclosed [27].

Three interventions were mandatory for medical students and included in a psychiatry or brain/behavior academic block [16,17,18]. Aggarwal’s intervention was optional and incorporated into a neuroscience module [14]. Kumra’s intervention was tied to mandatory orientation activities [26]. Pillai’s intervention appeared entirely optional and was offered after hours [13], Vaa Stelling’s intervention replaced the internal medicine residency’s noon conference for the day [15], and Hankir’s intervention was delivered multiple times in multiple nonspecific settings without providing enough information for further clarification [27].

The senior physicians who disclosed to residents were core faculty members [15], while nearly all physicians who disclosed to medical students in both articles by Martin et al. had recently been involved in delivering lectures and other educational content to the class [17,18]. Aggarwal’s research involved peer disclosure in addition to senior physician disclosure; in this case, medical students disclosed to other members of their class [14]. Pre-existing relationships were assumed to exist in all of these situations. Hankir’s research [27] assumed there was no pre-existing relationship between the audience and those making the disclosure, while other research involved peer disclosures [14,16,26]. In several cases, the physicians who disclosed were already known to the learners [15,17,18]. Two interventions involved anonymous disclosure or the option to share anonymously [13,16].

The publications included 11 aims. A conceptual content analysis identified two primary themes: stigma reduction and behavior change. All of the reported interventions sought to decrease mental health stigma (e.g., “decrease stigma around mental health treatment and of individuals with mental illnesses” [17]). Stigma reduction was the sole focus of three interventions [14,26,27]. Four interventions sought to create behavior changes related to help-seeking behaviors [15,16,17,18]. For example, behavior change was an aim of the intervention and was measured by analyzing the change in the utilization of campus mental health resources following the program’s implementation [16].

The reported interventions mostly described reaction-based outcomes, which corresponds with the Level 1 evaluation of the Kirkpatrick Model. One publication reported a Level 3 outcome (i.e., behavior change) in which medical students’ utilization of student counseling services increased by 25% over a 6-year window, compared with a 3% increase among non-medical students not exposed to the intervention [16]. Seven publications evaluated only learner satisfaction with the educational experience (i.e., Kirkpatrick level 1 evidence) [13,14,15,17,18,26,27]. These publications used non-validated, self-designed surveys to determine learner satisfaction.

4. Discussion

This study maps the literature on educational interventions featuring mental health self-disclosure in the context of medical training. The literature is limited, with six of the eight identified publications appearing in the last five years. We posit that this interest will grow as increased attention and resources are focused on medical students’ mental health. Thus, in this discussion, we highlight several critical topics for discussion and further analysis, which include the placement of interventions in curricula, the existing relationships between disclosers and their audiences, author self-disclosure, data quality, and the alignment of the study aims and reported results.

4.1. Curricular Placement

Most of the mandatory interventions took place in an educational setting focused on psychiatry or neuroscience. Martin et al. questioned whether discussions about accessing mental healthcare should primarily reside in psychiatry or if they should be generalized to other specialties [18]. Restricting disclosure interventions to psychiatric educational settings may lead participants in other specialties to ignore the information or view it as irrelevant. Thus, educators are encouraged to implement self-disclosure interventions in a variety of settings to demonstrate that mental health conversations are not limited to psychiatry [18]. Moreover, including disclosure interventions in the curricula and making them mandatory for students emphasizes the importance of the content. However, some argue that because students tend to resent extra mandatory work that they view as unnecessary, they may be more resistant to engaging with the material [28,29]. Including self-disclosure interventions in wellness curricula may help highlight their importance, focusing on mental health and wellness without making the intervention seem like an added requirement.

4.2. Pre-Existing Relationships as a Context for Disclosure

This study raises questions about the nature of self-disclosure and the influence of pre-existing relationships when self-disclosure occurs. This study highlights a range of pre-existing relationships between those making the disclosures and their audiences (e.g., core residency faculty, faculty actively teaching medical school courses, or professional speakers). The research demonstrates that disclosures are more salient when delivered during individual conversations or small groups and by individuals with whom students have a pre-existing relationship [30]. This study found that the most salient disclosures occurred among disclosing physicians, residents, and medical students, but that self-disclosure in any format or venue can still have benefits [30]. Further, the literature also suggests that trainees in other healthcare fields are more likely to be transparent about their mental health when a supervisor initiates self-disclosure about their own mental health [31]. However, the research examining supervisor or senior peer self-disclosure to residents or medical students with whom these individuals have pre-existing relationships is limited. Similarly, the available literature does not examine the differences between disclosure to a near-peer (e.g., a senior medical student to a junior medical student, or a resident to an intern) and disclosure where a more significant power differential is present (e.g., a medical school dean to junior medical students, or a residency program director to incoming interns). Large-scale interventions are often the easiest to deliver. These interventions may include disclosures to individuals with pre-existing relationships but focus largely on disclosures to groups with whom there may not be a pre-existing relationship. Thus, it is important to assess the outcome data to determine the impact of these interventions. Future research should evaluate the impact that pre-existing relationships have on the decision to disclose, as well as on the impact that such disclosures may have.

4.3. Author Self-Disclosure

Fear of career repercussions is frequently cited as a limiting factor in the literature on physician mental health; specifically, publications note the high number of physicians whose mental health conditions remain untreated [2,5,7]. Medical students and residents eventually become licensed, practicing physicians who will need to address questions about their mental health history from state licensing boards. However, only three publications discussed the possible impact of mental health treatment on medical licensing [15,16,17].

Possibly due to that fear, none of the authors disclosed their own mental health history in the articles, whether in the described intervention or as a factor informing decisions about the development of the interventions. If medical education wants to advocate for self-disclosure on a challenging topic, then it seems reasonable for leading physician researchers to model the behavior they encourage. The first author of this publication (MQ) has self-disclosed her mental health experiences as a physician in written and live educational formats, both anonymously and with attribution, and encourages her colleagues to also consider such disclosure in educational settings.

4.4. Quality of Data

The field lacks robust empirical support for the practice of self-disclosure in medicine. We need more research that assesses best practices and the implications of such interventions; the ways in which disclosure changes trainee–faculty relationships; and the ethical considerations when self-disclosing in educational contexts and in physician–trainee relationships. In particular, publications need to move beyond the research outcomes at Kirkpatrick level 1, which largely describes participant reactions, to Kirkpatrick levels 3 and 4, which measure the impact of an intervention on participant behavior and long-term institutional goals [32].

4.5. Alignment of Aims and Results

The authors of the included studies aimed to assess behavior or belief system changes resulting from participation in the described intervention. However, in most cases, the results reported participant satisfaction and knowledge acquisition, with only one example of a behavior change. Some authors described larger research aims than their study designs were able to support. The exception was Brenner et al., who measured changes to the utilization of mental health resources by medical students for the 6 years following the implementation of an ongoing intervention [16]. The consistent misalignment of the research goals and the reported outcomes highlights the sensitivity of the research topic and the difficulty of assessing stigmatized or otherwise charged behavior, particularly when available objective measures are limited. Future research should emphasize outcomes at Kirkpatrick levels 3 and 4 (i.e., behavior change and patient outcomes) to establish the impact of self-disclosure on help-seeking behavior and other outcomes related to mental health, and may need to include a more robust discussion of the outcome measures when studies are developed.

4.6. Limitations

Like any study, this scoping review has several limitations. First, despite the best efforts to conduct comprehensive searches, we might have inadvertently missed relevant publications. Secondly, we did not validate our results by discussing them with experts currently working in the field, as Levac et al. recommend as a revision to Arksey and O’Malley’s approach to scoping reviews [33]. Finally, the available literature represents a narrow geographic focus. The research has demonstrated similar rates of depression and other mental health concerns in medical students in additional countries that are not represented by the studies in this review [34]. Many aspects of mental health are culturally bound, but in an increasingly globalized world it will be important to determine which mental health interventions can be more broadly applied with positive outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that physicians’, residents’, and medical students’ self-disclosure of their mental health history has been employed to help educate about the available resources, reduce stigma, and encourage engagement with mental health treatment throughout medical education and training. This area of inquiry is only recently being seen as a potential area of growth, and the development of future interventions that provide information about the availability of resources and how they may be accessed, as well as substantive changes in the way psychiatric treatment is viewed by medical licensing and credentialing agencies and employers, may have a significant impact on the mental health of physicians, residents, and medical students around the world. The role of self-disclosure and the intersection with licensing concerns merit more attention as this area develops. An ongoing assessment of these interventions is needed to determine the extent to which they can meaningfully impact behavior changes and determine the best practices for employing these interventions in medical training environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E.Q., L.A.M., D.R.B. and L.N.A.; methodology, M.E.Q., L.A.M., D.R.B. and L.N.A.; validation, M.E.Q., L.A.M., D.R.B. and L.N.A.; formal analysis, M.E.Q., L.A.M., D.R.B. and L.N.A.; investigation, M.E.Q., L.A.M., D.R.B. and L.N.A.; resources, M.E.Q., L.A.M., D.R.B. and L.N.A.; data curation, M.E.Q., L.A.M., D.R.B. and L.N.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.E.Q.; writing—review and editing, L.A.M., D.R.B. and L.N.A.; visualization, M.E.Q., L.A.M., D.R.B. and L.N.A.; supervision, M.E.Q., L.A.M., D.R.B. and L.N.A.; project administration, M.E.Q., L.A.M., D.R.B. and L.N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Joe Costello and Rhonda Allard for their assistance in performing the literature search that formed the basis of this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Database search strategy.

Table A1.

Database search strategy.

| Database | Search Parameters |

|---|---|

| PubMed |

|

| Embase |

|

| Web of Science |

|

| PsycINFO (n = 334) |

|

| Ebsco Open Dissertations |

|

References

- Bacchi, S.; Licinio, J. Qualitative literature review of the prevalence of depression in medical students compared to students in non-medical degrees. Acad. Psychiatry 2015, 39, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Thomas, M.R.; Shanafelt, T.D. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad. Med. 2006, 81, 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthran, R.; Zhang, M.W.; Tam, W.W.; Ho, R.C. Prevalence of depression amongst medical students: A meta-analysis. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Kranzler, H.R.; Krystal, J.H.; Speller, H.; Chan, G.; Gelernter, J.; Guille, C. A prospective cohort study investigating factors associated with depression during medical internship. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, K.J.; Andrew, L.B.; Goldman, E.B.; Schwenk, T.L. “I would never want to have a mental health diagnosis on my record”: A survey of female physicians on mental health diagnosis, treatment, and reporting. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2016, 43, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.; Grice, T.; Walker, B.; Kaiser, J. Barriers to help-seeking in medical students with anxiety at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, D.; Winstanley, S.J.; Greene, G. Understanding doctors’ attitudes towards self-disclosure of mental ill health. Occup. Med. 2016, 66, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamminga, M.A.; Tomescu, O. Medical student knowledge and concern regarding mental health disclosure requirements in medical licensing. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2021, 72, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bynum, W.E.; Sukhera, J. Perfectionism, power, and process: What we must address to dismantle mental health stigma in medical education. Acad. Med. 2021, 96, 621–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P. The Role of Disclosure in Beating Stigma. Psychology Today, 2 July 2019. Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-stigma-effect/201907/the-role-disclosure-in-beating-stigma (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Dyrbye, L.N.; West, C.P.; Sinsky, C.A.; Goeders, L.E.; Satele, D.V.; Shanafelt, T.D. Medical licensure questions and physician reluctance to seek care for mental health conditions. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhauer, J. A General Fights to Destigmatize Mental Health Issues: “There’s a Shame If You Show Weakness”. The New York Times, 19 March 2022. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/19/us/politics/military-mental-health.html (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Pillai, R.L.I.; Butchart, L.; Hill, K.R.; Lazarus, Z.; Patel, R.; Yan, L.E.; Kenyon, L.J.; Post, S.G. You’re not alone: Sharing of anonymous narratives to destigmatize mental illness in medical students and faculty. Acad. Psychiatry 2020, 44, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, A.K.; Thompson, M.; Falik, R.; Shaw, A.; O’Sullivan, P.; Lowenstein, D.H. Mental illness among us: A new curriculum to reduce mental illness stigma among medical students. Acad. Psychiatry 2013, 37, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaa Stelling, B.E.; West, C.P. Faculty disclosure of personal mental health history and resident physician perceptions of stigma surrounding mental illness. Acad. Med. 2021, 96, 682–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, L.D.; Wei, H.; Sakthivel, M.; Farley, B.; Blythe, K.; Woodruff, J.N.; Lee, W.W. Breaking the silence: A mental health initiative to reduce stigma among medical students. Acad. Med. 2023, 98, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.; Chilton, J.; Gothelf, D.; Amsalem, D. Physician self-disclosure of lived experience improves mental health attitudes among medical students: A randomized study. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2020, 7, 2382120519889352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Chilton, J.; Paasche, C.; Nabatkhorian, N.; Gortler, H.; Cohenmehr, E.; Weller, I.; Amsalem, D.; Neary, S. Shared living experiences by physicians have a positive impact on mental health attitudes and stigma among medical students: A mixed-methods study. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2020, 7, 2382120520968072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, A.; Glozier, N.; Leese, M.; Loughran, J.; Thornicroft, G. A controlled trial of mental illness related stigma training for medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2011, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coverdale, J.; West, C.P.; Roberts, L.W. Courage and mental health: Physicians and physicians-in-training sharing their personal narratives. Acad. Med. 2021, 96, 611–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R. Disclosing mental illness: A doctor’s dilemma. BJPsych Bull. 2020, 44, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirch, D.G. Physician mental health: My personal journey and professional plea. Acad. Med. 2021, 96, 618–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hankir, A.K.; Northall, A.; Zaman, R. Stigma and mental health challenges in medical students. Case Rep. 2014, 2014, bcr2014205226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software; Veritas Health Innovation: Melbourne, Australia, 2023; Available online: https://www.covidence.org (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Kumra, R.J.D.; Ronkon, C.; Attridge, B. Tackling stigma against depression amongst medical students. J. Investig. Med. 2020, 68, A209. [Google Scholar]

- Hankir, A.; Carrick, F.; Zaman, R. “The Wounded Healer”: An anti-stigma program targeted at healthcare professionals and students. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 41, S735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, K.; Edmonds, V.S.; Girardo, M.E.; Vickers, K.S.; Hathaway, J.C.; Stonnington, C.M. Medical students describe their wellness and how to preserve it. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velez, C.; Gendreau, P.; Saad, N. Medical students’ perspectives on a longitudinal wellness curriculum: A qualitative investigation. Can. Med. Educ. J. 2024, 15, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ene, I.; Kocaqi, E.; Acai, A. Learner experiences of preceptor self-disclosure of personal illness in medical education. Acad. Med. 2024, 99, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehr, K.E.; Daltry, R.M. Supervisor self-disclosure, the supervisory alliance, and trainee willingness to disclose. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2022, 53, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.N.; Merkebu, J. The kirkpatrick model: A tool for evaluating educational research. Fam. Med. 2024, 56, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bert, F.; Lo Moro, G.; Corradi, A.; Acampora, A.; Agodi, A.; Brunelli, L.; Chironna, M.; Cocchio, S.; Cofini, V.; D’Errico, M.M.; et al. Collaborating Group. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among Italian medical students: The multicentre cross-sectional “PRIMES” study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Academic Society for International Medical Education. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).