Abstract

Reviews of the literature on leadership training in undergraduate medical education have been conducted since 2014. Previous reviews have not identified networks, defined leadership, studied the selection criteria for instructors, nor analyzed leadership as interprofessional or transprofessional education. This scoping review fills these gaps. Inclusion criteria included use of competency-based education to teach leadership in universities, and quality assessment. Indexes and grey literature in Spanish, Portuguese, and English languages were included from six databases. Hand searching and consultation were employed for selected bodies of literature. This review identified leadership interventions in nine countries which had national and international networks primarily in English-speaking and European countries. No literature was found in Spanish-speaking or Portuguese-speaking countries, nor in Africa. Teaching leadership was linked mainly with undergraduate medical education and interprofessional education. This review identified 23 leadership and leader definitions and underscored the importance of including values in leadership definitions. Instructors were selected by discipline, role, experience, and expertise. This review may be used to inform the teaching of leadership in undergraduate medical curricula by suggesting potential networks, reflecting on diverse leadership definitions and interprofessional/transprofessional education, and assisting in selection of instructors.

1. Introduction

Health professional education (HPE) includes medicine, nursing, public health, and allied health professions. Educational institutions train one million doctors, nurses, midwives, and public health professionals each year globally, mostly in medical schools (n = 2420) and public health schools (n = 467) [1]. Medical schools are the most numerous among HPE schools, thus, they consume more financial resources than other higher education establishments. The expenditure for medical education is US $47 billion annually [1] and US $100 billion to 240 billion is spent on research for health [2,3].

Time is another resource to consider. It requires an investment of time to teach and train health workers, and it takes more time—at least 10 years [4]—to translate knowledge into action out in the field. Indeed, undergraduate medical education (UME) and postgraduate medical education (PGME) can require up to seven years of study each [5,6,7], and nursing may require up to five years [6,8] (Table S1).

Historically, HPE has been beset by challenges, including professional silos that have proven difficult to break down, and the identification and application of relevant competencies for the teamwork and leadership abilities needed to transform health systems [1]. Preparing for future pandemics has been recognized as one of the 13 most urgent challenges of this decade by the World Health Organization (WHO) [9]. Thus, knowledge translation (KT) has emerged as a necessary competency to reduce the gap between what is known from research evidence, and how it is used by stakeholders with the intention of improving health care systems [10]. KT has been applied by multiple stakeholders in education, health, and governance [11,12,13,14]. When combined with leadership skills, KT supports network creation and change management [1,15].

Health professionals’ schools have approached leadership development by applying competency-based educational frameworks (CBE) [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Leadership education in UME has been described in two reviews [24,25]. Leadership education was described in Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, India, Iran, Israel, Sweden, Switzerland, the United States of America (US), and the United Kingdom (UK). Brazil was the only country identified from Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). This region is important because within it are 513 of 2420 medical schools in the world (21%). The LAC region has more medical schools than Europe (n = 446.18%), India (n = 300. 12,4%), and North America (n = 173. 7,1%) [1].

The Brazilian study was reported by Martins et al. in 2015. The authors focused on the necessary medical teaching and leadership skills to reduce social inequities [26]. In the same manner, other LAC countries desire to teach leadership competencies in their undergraduate medical students and other HPE: Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Chile, Mexico, and Peru [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Consequently, this review will gather literature from LAC and worldwide.

The previous reviews have some limitations [24,25], such as including only peer-reviewed literature written in English and excluding grey and indexed literature that has been written in Spanish and Portuguese. These languages are official in 20 countries in LAC. In addition, they did not state who supports leadership education by providing resources, which actors were involved in its provision, nor did they provide information about the professional networks involved. Furthermore, they did not explore the inter-professional and transprofessional (IPE/TPE) aspects of UME, nor did they define what they meant by the term leadership.

In fact, Bandeira et al. have called to teach leadership in medical education to face metal health challenges in Brazil in 2018 [34]. They have mentioned that leadership has multiple definitions, and leadership competencies should be taught in health system users and HPE at the same time. Moreover, networking between different Brazilian medical societies to improve and modify medical school curriculum [34]. In the same country, Martins et al. did not provide a methodology in their article about designing leadership competencies, not considering IPE and TPE, and not providing a leadership definition [26]. Fennell conducted a review to conceptualize leadership in health and human service workforce and found 11 leadership conceptualizations. However, there is no mention of leadership use in UME, and the geographical distribution of the publications was Australia, Canada, USA, and UK [35].

Additionally, the two previous reviews and Brazilian experiences did not contemplate the criteria used for the selection of instructors who teach leadership and whether they were trained to do so. Phillips et al. conducted research on reporting educational research for health and have provided a guideline for reporting educational interventions [36,37]. This guideline calls for reporting educational concepts and instructors’ characteristics. Therefore, this study examines who educates future medical doctors about concepts in leadership and how leadership is defined in CBE by academics. More specifically, we attempt to look at the actors who report on and support UME, learners’ levels of experience, qualifications of instructors, and leadership definitions used.

2. Methods

2.1. Research Model

Munn et al. have guided authors to decide between conducting a systematic or scoping review [38]. We selected a scoping review based on their indications. First, a scoping review is ideal to determine the scope or coverage of a body of literature on leadership that is written in Spanish, Portuguese, and English. Second, to identify and analyze knowledge gaps about teaching leadership in UME in LAC and worldwide. Third, to clarify key concepts and definitions in the literature, and this review aims at defining leadership in UME.

This review was informed by work by Arksey et al. [39], the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) framework [40], and work by Levac et al. [41]. The review applied the JBI framework, which depicted six stages, initially identifying the research question and identifying relevant studies. The next steps were selecting literature and charting the data. Lastly was collecting, summarizing, and reporting the results, and doing a consultation exercise.

2.2. Participants

This review was framed in four participants or learners’ levels; undergraduate medical education, medical education that included residency and fellowship, interprofessional education, and transprofessional education. Definitions of each level can be found in Table S1.

2.3. Data Collection Tools

This scoping review used six databases: two databases that contained index literature: Medline and Embase, one database about education: Education Resources Information Center, two databases from LAC: Biblioteca Virtual en Salud [Virtual Health Library-VHS-] and Health Information from Latin America and the Caribbean Countries (LILACS) and one database that collected grey literature: Google scholar (Table S2). Authors used the export mechanism of each database into Microsoft® Excel®. Tableau Public 2021.4, and Microsoft were used to create tables and figures.

2.4. Data Collection Process

The question was formulated based on the population, concept, and context (PCC). The population was undergraduate medical students with an IPE/TPE perspective. The concept was leadership, and the context was CBE.

This scoping review included published and grey literature retrieved from the previously mentioned databases. JBI recommended two steps for the search strategy. First, the search was limited to two online databases relevant to the topic. Investigators PRF and KC screened the papers by title and abstract to identify the most useful words.

Next, the authors conducted a second search using the identified keywords and index terms in each database (Table S3). The search strategy included populations terms such as “medical students”, “health students”, “health professionals”, and “public health professionals”. The concept was “leadership” as an index term, title, and abstract. The context terms were: “competency-based education”, “curriculum”, and “undergraduate medical education”. This review searched the databases between 17 March 2021, and 11 June 2021.

Duplicated papers were eliminated based on title, year of publication and population characteristics. Afterwards, the hits were excluded by title, abstract and full-text, and these steps were reviewed independently by investigators PRF, FLCH and DRS. The eligibility criteria were based on PPC (Table S4). For instance, inclusion criteria: literature that explores CBE leadership in undergraduate medical student by itself or with other HPE. If the researchers had a doubt about duplication or eligibility criteria of the documents, these challenges were resolved by discussion with investigators KC and LJHF. Levac and colleagues mentioned that assessing literature methodological quality would support the advancement, application, and significance of scoping studies in research for health [41].

Thus, the quality of each paper was assessed by using one of the following toolkits: the Effective Public Health Practice Project for Qualitative Studies [42], the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Research Checklist [43], the Authority, Accuracy, Coverage, Objectivity, Date, Significance checklist for grey literature [44], and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool Version 2018 [45]. Each tool provided three categories: (i) “strong” or “yes”, (ii) moderate, “I cannot tell” or “?”, and (iii) “weak” or “no” (Table S4). This step was completed by one author and checked by a second author.

Data were extracted according to the following categories: bibliographic information, authors’ affiliations, location of the intervention, aim, learners’ levels, instructors’ information, supporter, and leadership definitions. Investigator PRF conducted the primary data extraction which was reviewed by FLCH. The disagreements were resolved by consultation with investigators KC and LJHF. The information was extracted and placed in the chart verbatim.

The team did not contact the corresponding author if a publication was categorized as “strong” or “yes”. Team members, nonetheless, contacted a corresponding author by email if the document received “moderate”, “weak”, “I cannot tell”, “no” or “?” categories. A hand search was executed, and it included the consultation exercise as well. The hand searching was conducted from 6 January to 10 March 2022 (Table S5). This was completed by PARF.

2.5. Data Analysis

Each author participated in the data analysis. Reporting on actors who publish literature was conducted by extracting their affiliations from each document. Afterwards, these affiliations were classified by countries, and it was determined with whom the actors published. The affiliation did not consider departments or academic units of the listed organization. Likewise, supporters were identified in each manuscript, and the actors and supporters were categorized according to their names, such as universities and health care services, and others (including institutes, alliances, associations, federations, ministries etc.).

Learners’ levels were extracted for each paper, and the learners were categorized as follows: (i) UME by itself, (ii) medical education: UME, residency and fellowship (iii) interprofessional based on the WHO’s definition, and (iv) transprofessional education. The instructors’ information described their professional disciplines, teaching experience/expertise or specific training [36,37]. Leadership definitions included both a leader and the act of leadership itself. We mapped the leadership concepts used against learners’ categories. This review followed the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) which was used for reporting [46].

3. Results

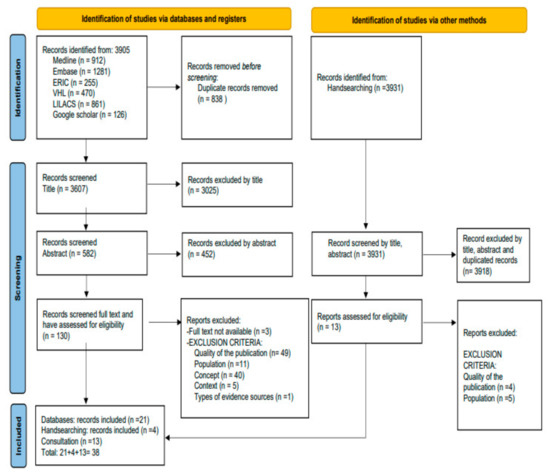

The search strategy and hand searching identified 7836 hits, and an additional 13 papers were collected when consulting authors from the retrieved hits (Figure 1). An amount of 145 hits were assessed for eligibility criteria, and 38 papers were finally included in this review. The 38 papers represented 23 studies on teaching leadership in UME [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69]. A summary is included in (Table 1 and Table S6), and the leadership landscape in UME (Figure 2). The 23 studies were centered primarily in the US (n = 12/23.52%), the UK (n = 3/23.13%), and Canada (n = 2/23.9%). Australia and New Zealand (Australasian), Germany, the Netherlands, the Republic of Korea, Saudi Arabia, and Ukraine conducted one study each.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for databases, registries, handsearching and consultation: A Scoping Review.

Table 1.

Summary of reported data items (n = 23).

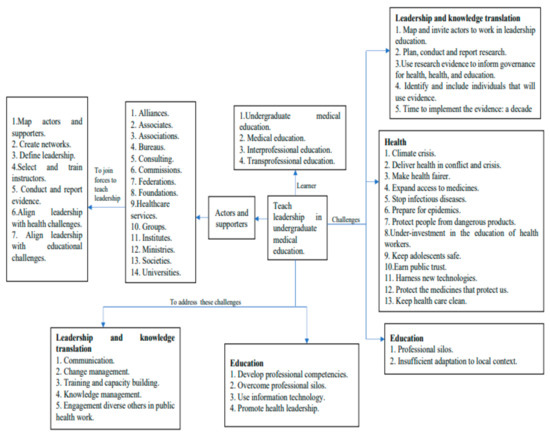

Figure 2.

Teaching leadership landscape in undergraduate medical education.

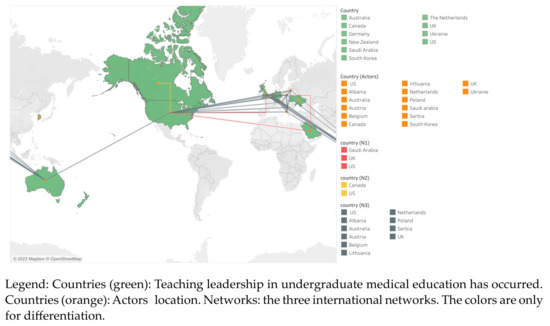

3.1. Mapping: Actors’ Networks and Their Supporters

Actors’ networking between countries occurred in three publications: one linked Saudi Arabia, the UK, and the US (network, N1) [51], and the second connected Canada and the US (network, N2) [58]. The third one related Albania, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Serbia, the US, and the UK (network, N3) [64] (Figure 3). Other networks were from the same country (n = 13/23. 57%), and the rest included one actor (n = 6/23. 26%).

Figure 3.

Actors and their networks when teaching leadership in undergraduate medical education.

An amount of 86 actors were identified in 23 studies (Table S7). The actors’ names contained such terms as hospitals, or universities. The actors were included under two categories: universities and health care services, and others. The first contained public and private universities, hospitals, and clinics (n = 75/86.87%), and the second gathered other actors, such as ministries or associations (n = 11/86.13%). Half of the studies received support (n = 12/23. 52%), and they mentioned 19 supporters in 7 countries.

3.2. Teaching Leadership: UME, IPE, and TPE

Some studies provide an overview of teaching leadership within a specific country (n = 5/23. 22%), and others designed models or frameworks to support future leadership curricula (n = 8/23.35%). Most studies report on teaching leadership to UME students (n = 10/23.43%). Other UME studies included other learners: residents (n = 2/23.9%) [57,58], fellows (n = 1/23.4%) [58], nurses (n = 3/23.13%) [52,56,58], dentists (n = 3/23.13%) [52,56,64], microbiologists (n = 1/23.4%) [64], pharmacists (n = 1/23.4%) [58], physical therapists (n = 1/23.4%) [58], social workers (n = 1/23.4%) [56]. UME and master’s degree students (n = 1/23.4%) [64], but not UME and PhD candidates (Table 2). The focus of the studies was on UME (n = 17/23.74%), Medical Education (n = 3/23.13%) [53,57,58], IPE (n = 4/23.17%) [52,56,58,64], and one study on teaching leadership in IPE and TPE (n = 1/23.4%) [64]. Dickerman et al. stated that their work might be expanded to other learners, including fellows and university staff [57].

Table 2.

Teaching leadership: undergraduate medical education (UME), medical education (ME), interprofessional education (IPE) and transprofesional education (TPE).

3.3. Defining Leadership and Learners’ Levels

Twenty-three definitions or conceptualizations of leadership were provided (n = 13/23.57%) (Table 3 and Table S8). Actors defined such concepts as: “lead”, “leader”, “leadership”, “lateral leadership”, “ethical leadership”, “leadership and change agency”, “professionalism and “ethics leadership”, “educational leadership”, “patience and leadership”, “shared leadership” and “leadership and resilience”. A definition of a leader was identified in UME and IPE. The most common cited actions were: (i) to inspire others to move on, to do the job well, to have a good practice, to become the best one can, (ii) to have, contribute, set, or create a vision, (iii) to engage or work with others to show the path ahead and create solutions, and (iv) to change and innovate.

Table 3.

Leadership and leader definitions that have been used and to whom.

Leaders should work in diverse areas, including clinicians, administrators, and academics. The most common leadership actions were: (i) to exert, perform, direct, or influence interpersonal and group dynamics for common or shared goals, (ii) to influence others by strengthening behaviours, cognitions, and motivations towards common goals, (iii) to produce or lead transformation and movement, and (iv) to contribute or achieve a vision. When the leadership definition included many concepts, the most common actions were: (i) to be responsible for each staff member, for human dignity, team performance, continuous development, and (ii) intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships to work in teams and build a partnership, respect, and change.

3.4. Instructor

The most common instructors’ selection criteria were their professional discipline, teaching experience/expertise, leadership experience/expertise, or leadership position (Table S6). Professions that were mentioned included: (i) medical doctors, (ii) actors, (iii) psychologists, and (iv) teachers. Teachers represented the following specialties: (i) medical educator, specialized in simulation-based training, (ii) trained actors for role plays, and (iii) curriculum developers, educational leaders, and educational scholars. Leadership was mentioned as a criterion: (i) to have expertise/knowledge in operational military leadership [52], (ii) anyone recognized for leadership ability [55], or (iii) to be specialized in leadership development [60]. Leadership positions, such as (i) leadership management position and team instructor [64], (ii) assistant professor, professor, or senior clinicians [64], (iii) a rank higher than the participants [57], and (iv) deans of the various professional schools were also mentioned [59] (Table S6).

Furthermore, instructors received specific training related to the educational intervention provided for teaching leadership. Instructors should attend an introduction session [56], online training [52], or they should review the teaching material [57]. The other instructors were trained in teaching by developing a model which contained ten core competencies, including but not limited to: professionalism and role modelling, program design/implementation, evaluation/scholarship, leadership, and mentorship [58]. Likewise, instructors received training in Problem Based Learning and blended educational format, and their skills were piloted. They received feedback on their performance [64].

4. Discussion

Although this review searched in six databases, and VHS and LILACS were focused on LAC literature, and countries that speak Spanish and Portuguese in Europe, no literature was found from this region, Spain, and Portugal. Additionally, this review did not identify actors, supporters, and networks to teach leadership in UME from these locations. Nonetheless, this review shed new light on leadership definitions, learners, instructors’ selection criteria and leadership training, and it has added a new dimension to the scholarship on CBE that can be used by multiple actors and supporters around the world.

Our study resonates with Webb et al. and James et al. reviews on teaching leadership in UME and adds some new insights [24,25]. First, this review maps publishing actors, their networks, and the supporters that conduct and report studies on teaching leadership in UME. The results indicated that nine countries teach leadership in UME or have started acknowledging that teaching leadership is key in their area of work.

It is crucial to develop and maintain networks for leadership, education, governance for health, and KT. Indeed, Bandeira et al. highlighted the necessity to have networks across the Brazilian medical societies to enhance leadership education in multiple learners in this country [34]. This review has found more actors and supporters than medical societies that are involved in leadership education, including universities, ministries, associations, and foundations, among others. Additionally, having national networks is important, and this review has documented them in Canada [47,50], Germany [60], Korea [53], UK [61,63,66], and US [55,57,59,68,69].

International networks are crucial to share experience and expertise, as we are facing similar health challenges such as climate change, pandemics, and health inequities. This review has detected international networks in Australia, North America, Europe, and the Middle East. As a result, Latin-American actors and supporters can establish international networks to teach leadership. For instance, Bandeira et al. have claimed leadership competencies to overcome the mental challenges in the health system [34].

Likewise, Gruner et al. and Hashmi et al. have reported their experience and expertise in leadership education that can be used to teach global health competencies for physical and mental health in UME [47,50]. Glegg et al. claims that networks provide the social context within KT, which occurs by accessing or sharing evidence and changing practice behaviors based on evidence among actors and supporters [14]. Additionally, Shearer and colleagues declare that networks influence governance for health because the primary goal of the evidence-informed health policymaking is a health system that is equitable and effective [11]. Policy networks foster KT by creating an environment where actors develop relationships, trust, and reduce conflict around research evidence [11]. Nonetheless, Glegg et al. reviewed 27 articles and they found that fewer than half of the articles presented network maps [14]. In line with Glegg et al.’s recommendation, this review maps the networks, since leadership and KT are about engaging with others [15].

Hoffman et al. define global health actors (GHA) as organizations which operate in three or more countries and are focused on health in 2018 [13]. These actors are important in the health domain, as they have networks in multiple countries, giving them more power. Thus, they are considered highly active players in the KT field.

In line with Hoffman et al. who map GHA, this review adds another GHA, the Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region (ASPHER). It has 112 actors from 43 countries, and 14 associate members from Africa, Australia, Japan, Palestine, and North America [70]. Likewise, Campbell et al. report a knowledge network for applied education research and KT [12]. The Knowledge Network for Applied Education Research (KNAER) gathers three actors in Canada, and two of them have been identified in this review.

Second, the Equator Network endorses the Guideline for Reporting evidence-based practice educational interventions and teaching (GREET) [71]. This scoping review is in line with this recommendation because it defines “leadership” as an educational concept used for teaching in UME. This review identifies 23 leadership definitions or conceptualizations.

These definitions could be considered by Martins et al., as they did not define leadership in their academic teaching program [26]. Bandeira and Mendoza cited Scherr and Jensen’s definition: “leadership can be defined as a set of verbal and nonverbal actions that may lead to results that otherwise could not be achieved” [34] (p. 170). However, this definition is fuzzy as one may ask about what stands for verbal and nonverbal actions.

This review has identified that leadership encompasses actions such as: to engage with others, to contribute to a vision, to inspire people to move on, to embrace change, to innovate, and to work collaboratively with teams to create solutions. Leadership is about actions and values that are divided into personal conscience and self-determination [15]. Personal conscience is related with who I am, and this review identified these values: to have patience which means to reflect on, examine, and endure in difficult situations, to take responsibility for delivery of patient care, and human dignity, to take responsibility for leaders’ staff through effective teamwork and the continuous development of personal leadership attributes and behaviors, and to develop humility. Self-determination is about what I am going to do, and this review has noticed these values. For instance, students’ capacity for resilience in intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships, and relationships within organizations to build partnership, respect and change capacity.

Third, this review provides leadership and leaders definitions and links them with learners in ITE or TPE, which has not been considered by others [24,25]. This means for us that leadership should be for each HPE. Bandeira and Mendoza can use definitions that targeted ITE/TPE as they have considered leadership competencies in HPE and health system users [34].

Fennell made a distinction between leadership and leader [35]. The first one refers to the process of influencing others, and the latter is an individual person. A leader and leadership approaches have been used in UME, medical education, IPE and TPE. The most common activity embedded in leadership definitions across learners includes exerting, performing, directing, or influencing interpersonal and group dynamics for common or shared goals. This activity is reflected in KT by creating and maintaining networks and communicating among actors that pursue education and governance goals for health [11,12,14,15,58]. For instance, the social network analysis has been used to study the influence of relationships and social structures in the KT process by health professionals [14] and GHA [13].

Fourth, the KT process is influenced by other factors, including professional knowledge, and practical experience [12]. Thus, leadership and KT foster training and capacity building to strengthen individual and organizational competencies [15]. While eight studies inform how to select the instructors, only two studies report on specific training for leadership instructors. These include training in blended educational format, which mixes face-to-face and online training [64,72]. Of note, online training has been recognized as an advanced communication and information technology to enhance access, compilation, and flow of information and knowledge [1].

While Phillips et al. conclude that instructors’ professional disciplines and their experiences are reported in less than 50% of the studies [36], our research finds that this information is included in more than 50% of studied documents. This difference could be explained because they did not perform a handsearch and consultation, and this review used both mechanisms to gather information from four studies [52,56,58,64].

From a societal perspective, it is crucial to teach leadership in UME as it contributes to preparing the students to address global health challenges: delivering health in conflict and crisis (C1), making healthcare fairer (C2), or preparing for epidemics (C3) [9]. These challenges are acknowledged by universities when they develop leadership frameworks in UME. For instance, one study has been teaching leadership to psychology or social sciences students in their master’s degrees [64]. In 2021, Gruner et al. created the Framework for Refugee and Migrant Health [47], which is in line with C1 and C2, and Bernard and colleagues designed the Pandemic Leadership Model to address C3 [48]. It is important to teach leadership in IPE and TPE, as all complex health challenges require leadership competencies to advance solutions.

The following recommendations are suggested to actors and supporters to foster KT in their organization to teach leadership in UME.

- To map actors and supporters that have expertise in teaching leadership in UME nationally and internationally. Mapping actors can provide a roadmap to advance leadership education in their country by sharing information and resources, and capacitating trainers and learners.

- To define or conceptualize leadership in their context. This review provided more than 20 definitions that can guide actors and supporters. We invite them to include values in their definition.

- To target the learners that will have leadership competencies. It can be in UME, medical education, IPE and TPE. Ideally, breaking silos is desirable, and teaching leadership is about having competency to work with others.

- To establish instructors’ expertise and academic background to teach leadership and consider capacitating instructors with leadership and educational competencies.

The following recommendations are suggested to editor journals, peer reviewers, and authors.

- Actors, journals, and peer reviewers should enhance the use of GREET to provide relevant information to others about education in this field.

4.1. Areas of Future Research

- The best methods and practices to create or adapt leadership definitions, to target the students, and to select and train the trainers in a specific context.

- Identification of best practices sharing, including leadership definitions, and competency models to support leadership education and training in UME.

- Teaching leadership in UME and PhD candidates simultaneously by using CBE has not been retrieved in this review.

4.2. Limitations of This Study

This review focuses on UME and its relationship with IPE/TPE, but the search strategy does not cover other professions, such as nursing or dentistry. While others have mapped networks using robust methods, this review maps networks by author’s affiliation. Likewise, this review considered actors at the organizational level without considering individual actors.

Although this review uses GREET checklist, it does not address all 17 components. Bandeira and Mendoza have called for teaching leadership to UME and health users. This review did not aim at studying leadership interventions that target these learners simultaneously. Studying leadership in UME and health users can be an area of future research. Additionally, this review found that trainers received training in blended education to teach leadership, but our review did not aim at studying the role of online teaching.

5. Conclusions

Literature about teaching leadership has been reported mainly in North America and Europe. Latin-American actors and supporters may use this review to contact individuals and organizations that have expertise in teaching leadership and develop possible networks at an international level. This review provides multiple leadership definitions and states who should acquire leadership competencies. Teaching leadership needs instructors who can be specially selected and trained.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ime2010006/s1, Table S1. Operational definitions. Table S2. The reasons to select the following databases. Table S3. Scoping review’s search strategy. Table S4. Eligibility criteria for conducting the scoping review. Table S5. Handsearching and Consultation. Table S6. Data Extraction for Studies Included (n = 23). Table S7. Actors and supporters that have reported teaching leadership in UME, IPE and TPE. Table S8. Granular description of leadership and leader by learner.

Author Contributions

P.R.-F., K.C., S.B., D.R.-S., F.L.C.H. and L.J.H.F. contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by P.R.-F., K.C., S.B., D.R.-S., F.L.C.H., and L.J.H.F. The first draft of the manuscript was written and reviewed by P.R.-F., K.C., S.B., D.R.-S., F.L.C.H., and L.J.H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Pablo Rodríguez-Feria received a Ph.D. grant from the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation from Colombia (Convocatoria 906: doctorados en el exterior 2021). The other authors did not receive funding to participate in this review. The manuscript will be paid by Maastricht University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

This scoping review did not need informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Chin-see (Wilfrid Laurier University) for providing a critical review of the manuscript and helping with language editing and proofreading as part of their internship with the World Federation of Public Health Associations. Likewise, we acknowledge the actors that replied to our emails for their time and commitment to share information with us.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Frenk, J.; Chen, L.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Cohen, J.; Crisp, N.; Evans, T.; Fineberg, H.; Garcia, P.; Ke, Y.; Kelley, P.; et al. Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 2010, 376, 1923–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalmers, I.; Glasziou, P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet 2009, 374, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macleod, M.R.; Michie, S.; Roberts, I.; Dirnagl, U.; Chalmers, I.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Salman, R.A.-S.; Chan, A.-W.; Glasziou, P. Biomedical research: Increasing value, reducing waste. Lancet 2014, 383, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visram, S.; Goodall, D.; Steven, A. Exploring conceptualizations of knowledge translation, transfer and exchange across public health in one UK region: A qualitative mapping study. Public Health 2014, 128, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeZee, K.J.; Artino, A.; Elnicki, D.M.; Hemmer, P.A.; Durning, S.J. Medical education in the United States of America. Med. Teach. 2012, 34, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrix Insight. EU Level Collaboration on Forecasting Health Workforce Needs, Workforce Planning and Health Workforce Trends—A Feasibility Study; Commission Feasibility Study on EU Level Collaboration on Forecasting Health Workforce Needs, Workforce Planning and Health Workforce Trends; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012; Available online: https://european-union.europa.eu/select-language?destination=/node/1 (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Talib, Z.; Narayan, M.L.; Harrod, M.T. Postgraduate Medical Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Scoping Review Spanning 26 Years and Lessons Learned. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2019, 11, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luengo-Martínez, C.E.; Sanhueza-Alvarado, O. Formación del licenciado en Enfermería en América Latina. Aquichan 2016, 16, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Urgent Health Challenges for the Next Decade. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/photo-story/photo-story-detail/urgent-health-challenges-for-the-next-decade (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Graham, I.D.; Logan, J.; Harrison, M.B.; Straus, S.E.; Tetroe, J.; Caswell, W.; Robinson, N. Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2006, 26, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, J.C.; Dion, M.; Lavis, J.N. Exchanging and using research evidence in health policy networks: A statistical network analysis. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Pollock, K.; Briscoe, P.; Carr-Harris, S.; Tuters, S. Developing a knowledge network for applied education research to mobilise evidence in and for educational practice. Educ. Res. 2017, 59, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, S.J.; Cole, C.B. Defining the global health system and systematically mapping its network of actors. Glob. Health 2018, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glegg, S.M.N.; Jenkins, E.; Kothari, A. How the study of networks informs knowledge translation and implementation: A scoping review. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Feria, P.; Flórez, L.J.H.; Czabanowska, K. Leadership Competencies for Knowledge Translation in Public Health: A consensus study. J. Public Health 2021, 44, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, O.J.; Carnall, R. Medical leadership: Why it’s important, what is required, and how we develop it. Med. J. 2011, 87, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz, L.J.; Stoller, J.K. A Systematic Review of Physician Leadership and Emotional Intelligence. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2014, 6, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frich, J.C.; Brewster, A.L.; Cherlin, E.J.; Bradley, E.H. Leadership Development Programs for Physicians: A Systematic Review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 656–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czabanowska, K. Public health competencies: Prioritization and leadership. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 734–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, M.; Van Oostveen, C.; Peters, J.; Vermeulen, H.; Huis, A. An integrative review of leadership competencies and attributes in advanced nursing practice. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 2378–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.J.; Gupta, T.S.; Johnson, P. Why we need to teach leadership skills to medical students: A call to action. BMJ Lead. 2019, 3, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cometto, G.; Buchan, J.; Dussault, G. Developing the health workforce for universal health coverage. Bull. World Health Organ. 2020, 98, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershuni, O.; Czabanowska, K.; Burazeri, G.; Bjegovic-Mikanovic, V.; Juszczyk, G.; Myrup, A.C.; Kurpita, V. Aligning Best Practices: A Guiding Framework as a Valuable Tool for Public Health Workforce Development with the Example of Ukraine. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, A.M.; Tsipis, N.E.; McClellan, T.R.; McNeil, M.J.; Xu, M.; Doty, J.P.; Taylor, D.C. A First Step Toward Understanding Best Practices in Leadership Training in Undergraduate Medical Education: A Systematic Review. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1563–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, E.; Evans, M.; Mi, M. Leadership Training and Undergraduate Medical Education: A Scoping Review. Med. Sci. Educ. 2021, 31, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, A.C.; Oliveira, F.R.A.; Delfino, B.M.; Pereira, T.M.; de Moraes, F.H.P.; Barbosa, G.V.; de Macedo, L.F.; Domingos, T.D.S.; Da Silva, D.P.; Menezes, C.C.R.; et al. How we enhanced medical academics skills and reduced social inequities using an academic teaching program. Med. Teach. 2015, 37, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobierno de Colombia; Ministerio de Educación y Ministerio de Salud. Documento de Recomendaciones para la Transformación de la Educación Medica en Colombia. 2017. Available online: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/VS/MET/recomendaciones-comision-para-la-transformacion.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Flores-Domínguez, C. Feminización En Medicina: Liderazgo Y Academia Feminization of Medicine: Leadership and Academics. Educ. Méd. 2012, 15, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Mendiola, M. Liderazgo en medicina: ¿debemos enseñarlo y evaluarlo? Investig. Educ. Méd. 2015, 4, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Gas. H.G.; Mazón-González, B. Calidad y liderazgo en medicina. Rev. CONAMED 2013, 18, 172–182. [Google Scholar]

- Revista Colegio Médico CL. Liderazgo en el Equipo Sanitario. 2019. Available online: http://revista.colegiomedico.cl/liderazgo-en-el-equipo-sanitario/ (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Llaque, D.W. Liderazgo-Ética Médica. Available online: http://anmperu.org.pe/anales/2011/liderazgo_etica_medica.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Abreu Cervantes, A.; Téllez Cabrera, M.Y. Líderes Universitarios Y Protagonismo Estudiantil. Caso Universidad De Ciencias Médicas De Camagüey. Humanidades Méd. 2018, 18, 504–520. [Google Scholar]

- Bandeira, I.D.; Mendoza, J. Medical education and leadership: A call to action for Brazil’s mental health system. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2018, 9, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, K.L. Conceptualisations of Leadership and Relevance to Health and Human Service Workforce Development: A Scoping Review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 3035–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.C.; Lewis, L.K.; McEvoy, M.P.; Galipeau, J.; Glasziou, P.; Hammick, M.; Moher, D.; Tilson, J.K.; Williams, M.T. A systematic review of how studies describe educational interventions for evidence-based practice: Stage 1 of the development of a reporting guideline. BMC Med. Educ. 2014, 14, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.C.; Lewis, L.K.; McEvoy, M.P.; Galipeau, J.; Glasziou, P.; Moher, D.; Tilson, J.K.; Williams, M.T. Development and validation of the guideline for reporting evidence-based practice educational interventions and teaching (GREET). BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: North Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K.; Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Health Care. The Effective Public Health Practice Project: Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. Instructions for Completion: Please Circle Appropriate Response in Each Section. Available online: https://www.ephpp.ca/ (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Checklist. CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/ (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Tyndall, J. AACODS Checklist. Flinders University. 2010. Available online: http://dspace.flinders.edu.au/dspace/ (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Registration of Copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada. Microsoft Word-MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-07-26.docx. 2018. Available online: https://www.pbworks.com/ (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruner, D.; Feinberg, Y.; Venables, M.J.; Hashmi, S.S.; Saad, A.; Archibald, D.; Pottie, K. An undergraduate medical education framework for refugee and migrant health: Curriculum development and conceptual approaches. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Ortiz, S.C.; Jones, E.; Heung, M.; Guetterman, T.C.; Kirst, N. The Pandemic Leadership Model: A Study of Medical Student Values During COVID-19. Int. J. Med. Stud. 2021, 9, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.J.; Gupta, T.S.; Johnson, P. Leadership curricula and assessment in Australian and New Zealand medical schools. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, S.S.; Saad, A.; Leps, C.; Gillies-Podgorecki, J.; Feeney, B.; Hardy, C.; Falzone, N.; Archibald, D.; Hoang, T.; Bond, A.; et al. A student-led curriculum framework for homeless and vulnerably housed populations. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeh, N.; Grant, J.; Farsi, J.; Tekian, A. Contextual Analysis of Stakeholder Opinion on Management and Leadership Competencies for Undergraduate Medical Education: Informing Course Design. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2020, 7, 2382120520948866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, E.S.; Dong, T.; Durning, S.J.; Schreiber-Gregory, D.; Torre, D.; Grunberg, N.E. Medical Student Leader Performance in an Applied Medical Field Practicum. Mil. Med. 2019, 184, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, Y.; Lee, K. Identification and evaluation of the core elements of character education for medical students in Korea. J. Educ. Evaluation Health Prof. 2019, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portney, D.S.; VonAchen, P.; Standiford, T.; Carey, M.R.; Vu, J.; Kirst, N.; Zink, B. Medical Student Consulting: Providing Students Leadership and Business Opportunities While Positively Impacting the Community. MedEdPORTAL 2019, 15, 10838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, K.; Noujaim, M.; Thorndyke, L.E.; Fischer, M.A. Preparing Medical Students to Be Physician Leaders: A Leadership Training Program for Students Designed and Led by Students. MedEdPORTAL 2019, 15, 10863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenschutz, H.; McKean, E.L.; Mangrulkar, R.; Zurales, K.; Santen, S. A first-year leadership programme for medical students. Clin. Teach. 2019, 16, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerman, J.; Sánchez, J.P.; Portela-Martinez, M.; Roldan, E. Leadership and Academic Medicine: Preparing Medical Students and Residents to Be Effective Leaders for the 21st Century. MedEdPORTAL 2018, 14, 10677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.C.; Wamsley, M.A.; Azzam, A.; Julian, K.; Irby, D.M.; O’Sullivan, P.S. The Health Professions Education Pathway: Preparing Students, Residents, and Fellows to Become Future Educators. Teach. Learn. Med. 2017, 29, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalo, J.D.; Dekhtyar, M.; Starr, S.R.; Borkan, J.; Brunett, P.; Fancher, T.; Green, J.; Grethlein, S.J.; Lai, C.; Lawson, L.; et al. Health Systems Science Curricula in Undergraduate Medical Education. Acad. Med. 2017, 92, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Huber, M.; Netzel, J.; Kiesewetter, J. On the road to becoming a responsible leader: A simulation-based training approach for final year medical students. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2017, 34, Doc34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferies, R.; Sheriff, I.H.; Matthews, J.H.; Jagger, O.; Curtis, S.; Lees, P.; Spurgeon, P.C.; Fountain, D.M.; Oldman, A.; Habib, A.; et al. Leadership and management in UK medical school curricula. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2016, 30, 1081–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydorchuk, A.; Moskaliuk, V.D.; Randiuk, Y.O.; Sorokhan, V.D.; Golyar, O.I.; Sydorchuk, L.; Humenna, A.V. Aspects of development of leader creative thinking of medical student at the undergraduate level of medical education. Wiadomości Lek. 2016, 69, 809–812. [Google Scholar]

- Stringfellow, T.D.; Rohrer, R.M.; Loewenthal, L.; Gorrard-Smith, C.; Sheriff, I.H.; Armit, K.; Lees, P.D.; Spurgeon, P.C. Defining the structure of undergraduate medical leadership and management teaching and assessment in the UK. Med. Teach. 2015, 37, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czabanowska, K.; Smith, T.; Könings, K.; Sumskas, L.; Otok, R.; Bjegovic-Mikanovic, V.; Brand, H. In search for a public health leadership competency framework to support leadership curriculum-a consensus study. Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 24, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, P.B.; Williams, J.; Malani, P.N.; Riba, M.; Haig, A.; Perry, J.; Kolars, J.C.; Mangrulkar, R.; Williams, B. Promoting medical students’ reflection on competencies to advance a global health equities curriculum. BMC Med. Educ. 2014, 14, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quince, T.; Abbas, M.; Murugesu, S.; Crawley, F.; Hyde, S.; Wood, D.; Benson, J. Leadership and management in the undergraduate medical curriculum: A qualitative study of students’ attitudes and opinions at one UK medical school. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e005353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warde, C.M.; Vermillion, M.; Uijtdehaage, S. A medical student leadership course led to teamwork, advocacy, and mindfulness. Fam. Med. 2014, 46, 459–462. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, M.M.; Blatt, B.; Greenberg, L. Preparing Students to Be Academicians: A National Student-Led Summer Program in Teaching, Leadership, Scholarship, and Academic Medical Career-Building. Acad. Med. 2012, 87, 1734–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkey, P.; Peloquin, J.; Reed, D.; Lindor, K.; Harris, I. Leadership curriculum in undergraduate medical education: A study of student and faculty perspectives. Med. Teach. 2009, 31, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, I.J. Commentary: ASPHER at age 50. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Equator Network. Development and Validation of the Guideline for Reporting Evidence-Based Practice Educational Interventions and Teaching (GREET)|The EQUATOR Network. 2021. Available online: https://www.equator-network.org/ (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Könings, K.D.; De Jong, N.; Lohrmann, C.; Šumskas, L.; Smith, T.; O’Connor, S.J.; Spanjers, I.A.E.; Van Merriënboer, J.J.G.; Czabanowska, K. Is blended learning and problem-based learning course design suited to develop future public health leaders? An explorative European study. Public Health Rev. 2018, 39, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).