Abstract

Background/Purpose: Ophthalmic triage is challenging for non-specialists due to limited training and rising global eye disease burden. This study evaluates a multimodal framework integrating clinical text and ophthalmic imaging with large language models (LLMs). Textual consistency filtering and chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning were incorporated to improve diagnostic accuracy. Methods: A dataset of 56 ophthalmology cases from a Singapore restructured hospital was pre-processed with acronym expansion, sentence reconstruction, and textual consistency filtering. To address dataset size limitations, 100 synthetic cases were generated via one-shot GPT-4 prompting, validated by semantic checks and ophthalmologist review. Three diagnostic approaches were tested: Text-Only, Image-Assisted, and Image with CoT. Diagnostic performance was quantified using a novel SNOMED-CT-based dissimilarity score, defined as the shortest path distance between predicted and reference diagnoses in the ontology, which was used to quantify semantic alignment. Results: The synthetic dataset included anterior segment (n = 40), posterior segment (n = 35), and extraocular (n = 25) cases. The text-only approach yielded a mean dissimilarity of 6.353 (95% CI: 4.668, 8.038). Incorporation of image assistance reduced this to 5.234 (95% CI: 3.930, 6.540), while CoT prompting provided further gains when imaging cues were ambiguous. Conclusions: The multimodal pipeline showed potential in improving diagnostic alignment in ophthalmology triage. Image inputs enhanced accuracy, and CoT reasoning reduced errors from ambiguous features, supporting its feasibility as a pilot framework for ophthalmology triage.

1. Introduction

Efficient ophthalmology triage ensures timely care for high-risk patients while preventing unnecessary specialist referrals that burden ophthalmology services. In clinical practice, patients presenting with ocular complaints are often first evaluated by general or emergency physicians, whose accuracy in triage depends heavily on their training and experience. With ocular-related complaints representing a growing burden on emergency departments, proper triage of these cases is essential for proper healthcare resource allocation. A study conducted in the United States found that of 16.8 million eye-related emergency department visits occurring from 2010–2017, 44.8% of the cases were for non-emergent conditions [1]. Inaccurate or inconsistent referrals can delay urgent care, contribute to overcrowded clinics, and misallocate specialist resources [2,3]. These challenges are compounded by the rising prevalence of vision-threatening conditions such as diabetic retinopathy, cataract, and glaucoma [4].

Recent advances in large language models (LLMs) and vision-language models (VLMs) offer the potential to enhance triage decision-making. LLMs can process and interpret unstructured clinical text, while VLMs extend this capability to medical images, including anterior segment and fundus photographs [5,6]. When combined, these modalities enable a more holistic case assessment. However, LLMs typically produce single-step outputs that can oversimplify complex reasoning, leading to diagnostic inaccuracies [7]. Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting has been proposed to address this limitation by breaking down decision-making into sequential steps, improving interpretability and diagnostic reasoning in medical tasks [8].

Existing research in AI-assisted ophthalmology triage has shown mixed results. For example, AI-based decision support systems have been trialled for emergency referrals and on-call consults, showing comparable or superior accuracy to referring providers [9]. More recently, multimodal systems integrating ChatGPT-3.5 (version 3.5, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) with anterior segment images have been piloted in outpatient triage workflows [10]. Other studies evaluating GPT-4 (version 4, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) and other generalist VLMs have reported variable performance, particularly for images requiring fine spatial interpretation, such as gonioscopy or visual field charts [11]. Moreover, issues such as hallucination, bias, and difficulty processing unstructured clinical notes remain significant barriers to safe deployment [12,13,14].

This pilot study aims to explore the feasibility of a multimodal diagnostic pipeline incorporating text, imaging, textual consistency filtering and CoT-augmented reasoning. The study also proposes a novel SNOMED-CT Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) metric, which accounts for semantic similarity between related ophthalmic diagnoses. We hypothesized that integrating image data and CoT reasoning could improve diagnostic alignment compared to text-only prompts, recognizing that our small real dataset and use of synthetic augmentation make this an exploratory rather than confirmatory study.

2. Methods

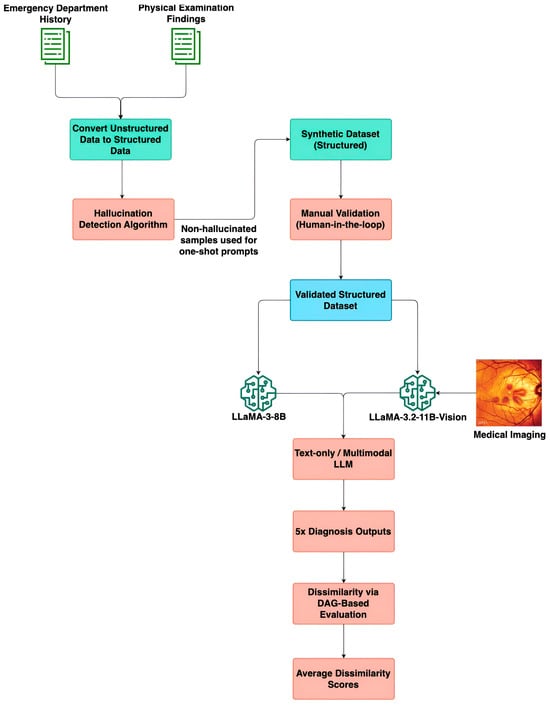

2.1. Overview of Proposed Pipeline

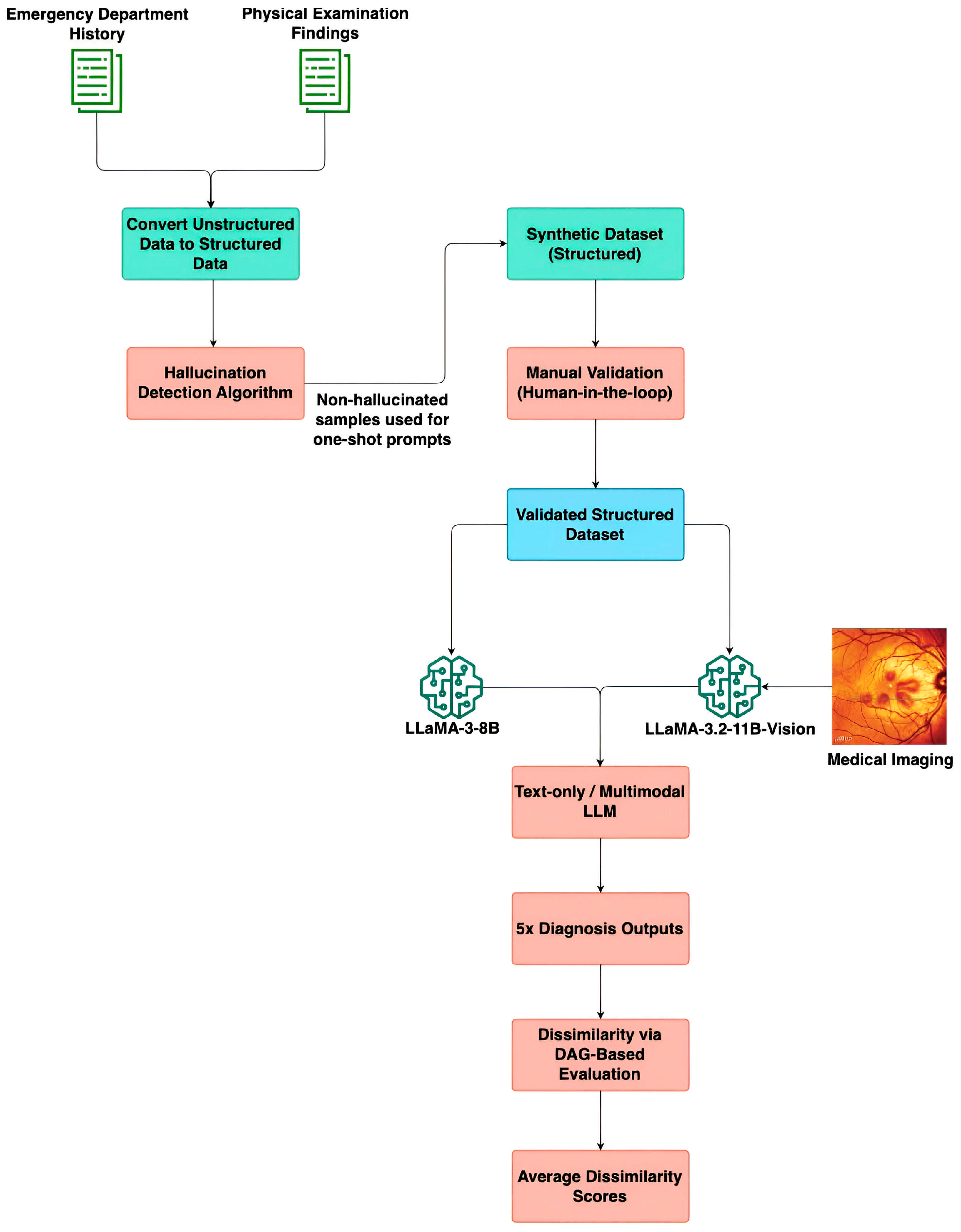

Figure 1 depicts an end-to-end overview of the proposed methodology. It illustrates the sequential steps involved in processing unstructured ED notes and physical examination findings, filtering textual consistency, generating a validated synthetic dataset, and evaluating diagnosis predictions using multimodal LLMs and a DAG-based graph evaluation framework.

Figure 1.

Proposed end-to-end processing pipeline. Includes pre-processing pipeline of clinical dataset, generation of synthetic dataset, verification of various diagnostic approaches based on the DAG-based dissimilarity metric.

2.2. Data Collection

This single-centre retrospective study involved patients who were referred to the Ophthalmology department of Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore. The patients were consecutively selected across a period from 1 November 2022 to 30 May 2023. Retrospective data collected for analysis included: the date of referral, history taken at the time of referral, the provisional diagnosis given at the time of referral, the time interval from referral to an Ophthalmology department visit, the history taken at the Ophthalmology department, and the diagnosis given at the Ophthalmology department.

This study was conducted in accordance with the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB), Singapore, which also approved this study protocol (reference number 2023/00348, approval date: 10 October 2023). Patient information was anonymized and de-identified before the analysis.

2.3. Clinical Dataset and Pre-Processing

A clinical dataset of ophthalmology triage information for 56 patients was obtained from Tan Tock Seng Hospital. The cases were collected consecutively from emergency ophthalmology presentations over the study period. All identifiable patient information was removed before analysis, and the resulting dataset was fully anonymised in accordance with the National Healthcare Group’s data governance and the Singapore Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA), ensuring that it was untraceable to any individual patient. This anonymisation process was applied prior to pre-processing, thereby ensuring that the study did not infringe on patient confidentiality or ethical standards for secondary data use.

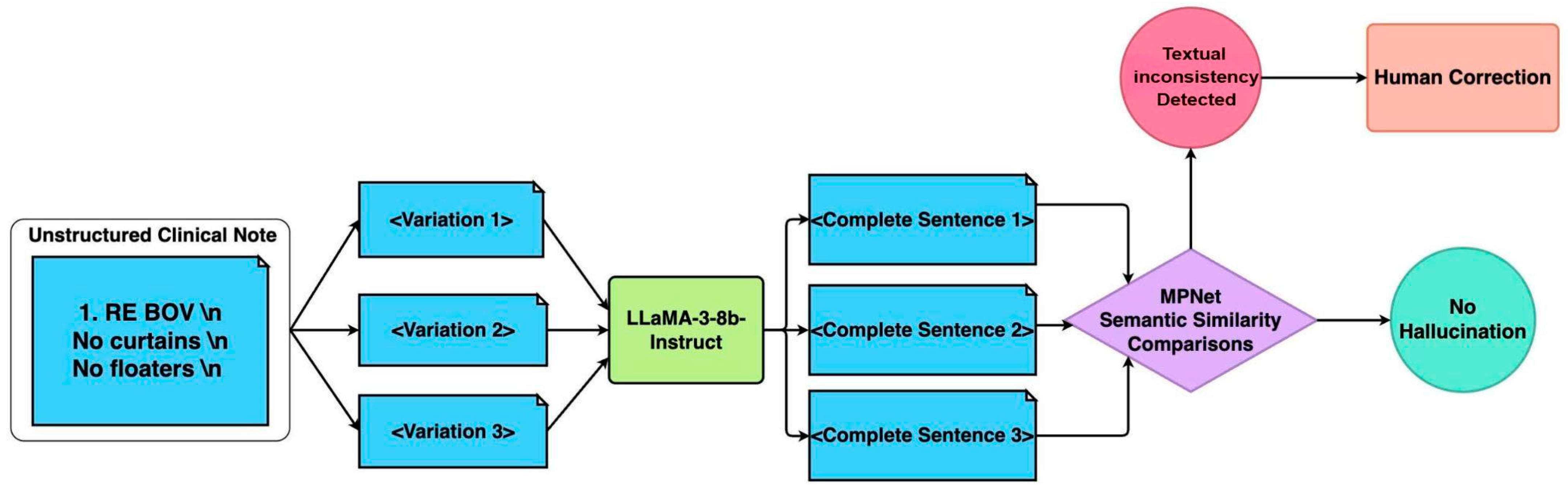

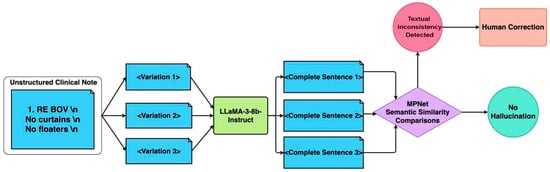

Raw medical notes may prove challenging for LLMs due to the heavy use of medical abbreviations, lack of standardised grammar, and ambiguity depending on the medical context. To ensure machine-readable LLM inputs whilst retaining the necessary medical information, a pre-processing pipeline was performed that reconstructed fragmented medical notes into grammatically coherent and structured sentences. A textual consistency filtering pipeline was designed to ensure that the original meaning of the notes was kept (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Textual Consistency Filtering Pipeline.

The first step of the pipeline was acronym expansion and text standardization. Domain-specific acronyms (e.g., “BOV” for blurring of vision) were replaced using a medical acronym dictionary (Supplemental Table S1). Following acronym expansion, multiple variations of the clinical note were generated by randomly shuffling sentence components while preserving the original meaning. The text was segmented using newline characters and re-combined. This approach introduces controlled randomness while maintaining the core clinical information.

The second step was sentence reconstruction: the LLaMA 3 8B Instruct model (version 3, Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, United States) was employed to reconstruct fragmented text into complete, grammatically coherent sentences. To ensure fidelity, multiple reconstructions were generated for each case. Text generation was regulated based on the set of hyperparameters outlined in Table 1, to influence the diversity and stability of the output. The temperature parameter was set to 0.6 to introduce a moderate level of randomness while preventing excessive deviation from the expected phrasing. The top-p (nucleus value) of 0.9 restricts token selection to the most probable subset, reducing the likelihood of generating inconsistent or overly creative responses. The max token limit was set to 2048, ensuring that the generated text remains an appropriate length.

Table 1.

LLaMA 3 8B Instruct Model Parameters.

The final step in the pipeline was semantic similarity assessment. The reconstructions were then screened using the Masked and Permutated Pre-training Network (MPNet) (version MPNet-base, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) embeddings with a cosine similarity threshold of 0.8 to filter out hallucinated or inconsistent outputs. In the case that all surpass the threshold of 0.8, the case with the highest overall similarity is selected. MPNet thus helps to prioritize consistent outputs while filtering out misleading or hallucinated responses, ensuring the processed text remains factually accurate and clinically safe for model input.

2.4. Synthetic Dataset Generation

The clinical dataset obtained from the Ophthalmology Department at Tan Tock Seng Hospital proved insufficient for evaluation of the LLM-based diagnostic and triage systems, due to a small sample size of 56 cases, as well as poor depth of clinical documentation and completeness necessary for independent diagnostic reasoning.

To overcome this, a synthetic dataset of 100 ophthalmic triage cases was generated based on the clinical dataset using one-shot prompting with GPT-4 to create a more comprehensive and clinically realistic dataset that would mimic information obtainable from real-world cases more closely. The outputs of the earlier data pre-processing and textual consistency pipeline were then fed into GPT-4 to generate this synthetic dataset. GPT-4 was selected for synthetic data generation due to its superior few-shot reasoning and clinical language capabilities. This approach produced high-quality cases that mirrored the linguistic and conceptual structure of authentic ophthalmic records. The diagnoses included in the dataset were selected to represent ophthalmological conditions commonly seen in the emergency and outpatient settings.

After selecting 100 final cases, GPT-4 was used to generate corresponding Emergency Department (ED) histories, physical examination findings, diagnostic reasoning, and urgency levels for each case. The prompt used for sentence reconstruction can be found in Supplemental Figure S1. To enhance plausibility and diversity, a one-shot prompting approach was adopted. This involved presenting GPT-4 with the curated examples from TTSH’s clinical notes which had passed through the data pre-processing and textual consistency filtering as detailed above. This strategy allowed for the synthesis of detailed and differentiated cases that reflect the complexity and nuance of actual ophthalmology presentations, while also addressing the limitations of the original dataset.

To assess the semantic alignment between the synthetic and real-world datasets, we computed sentence similarity scores using SBERT (MPNet cosine similarity). The results showed a moderate correlation, with scores ranging from 0.6 to 0.7. This evaluation confirms that the synthetic cases retained meaningful linguistic and conceptual resemblance to authentic ophthalmology records, while preserving variability and completeness necessary for robust model evaluation.

The final step in the synthetic data generation process involved expert validation by two ophthalmologists to ensure clinical accuracy, diagnostic validity, and real-world applicability. The experts conducted a comprehensive review of all generated cases, evaluating the consistency and plausibility of emergency department histories and physical examination findings. Diagnoses were revised as needed to align with expected clinical presentations, and textual descriptions were refined to enhance clarity, specificity, and realism. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved jointly before inclusion in the final dataset. Formal inter-rater agreement statistics were not computed, as validation was performed collaboratively rather than independently. This validation process also incorporated ophthalmic imaging to enable multimodal evaluation. The expert assigned appropriate image modalities—such as fundus photographs, external eye images, and Humphrey visual field tests—according to each case’s final diagnosis. This human-in-the-loop validation process enhanced the dataset’s clinical fidelity and diagnostic robustness, establishing it as a reliable benchmark for evaluating both text- based and multimodal (text and image) ophthalmology triage models.

2.5. Diagnostic Framework

We evaluated three separate diagnostic approaches:

Firstly, the direct prompting (text-only, also known as non-image) approach serves as the baseline in this study. In this approach, the LLM generated a diagnosis based solely on textual inputs—specifically, the patient’s Emergency Department (ED) History and Physical Examination findings. We utilized the LLaMA-3-8b-Instruct model from Meta, which has been fine-tuned for instruction-based reasoning tasks. The LLM received a structured prompt (Figure S2) guiding it to produce the most likely diagnosis along with justification, minimizing ambiguity and facilitating systematic evaluation.

Secondly, the multi-modal input approach incorporates both textual inputs and visual data to evaluate whether image integration enhances clinical reasoning. The model is provided with a structured prompt (Figure S3) along with three types of input:

- ED history and physical examination findings, which form the textual component of the diagnostic evaluation.

- A medical image associated with the patient’s condition, corresponding to one of the ophthalmic imaging modalities under investigation.

- A description of the image type (e.g., fundus image, anterior segment photo) to provide context for interpretation.

Textual inputs were initially processed by the LLaMA-3-8B-Instruct model to generate preliminary diagnostic predictions. Images were pre-processed using the LLaVA (version LLaVA 1.5, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI, USA) image processor, including RGB normalization, resizing, center-cropping, and tensor conversion to ensure compatibility with the vision encoder. The textual and image inputs were subsequently fed into the LLaVA-OneVision-Qwen2 model (version 0.5B, Imms-lab, Singapore, Singapore) for multimodal reasoning, producing the final diagnostic output.

Lastly, to overcome limitations observed with the direct multimodal prompting, we augmented the process with CoT reasoning. This seeks to improve LLM interpretability and diagnostic reasoning by decomposing complex tasks into sequential steps. CoT prompting was applied selectively to cases identified as visually ambiguous or diagnostically complex. These were defined as cases where initial image-assisted diagnosis showed high dissimilarity scores, in which an expert ophthalmologist identified subtle or overlapping visual features that could not clearly distinguish between differential diagnoses. This approach employed a two-step process: first, the model generates a preliminary diagnosis and justification based on the clinical text provided. Next, a subsequent prompt integrated the relevant imaging data along with modality-specific instructions (e.g., “review retinal vessels and optic disc changes” for fundus images) to refine the initial diagnosis. The CoT prompt templates are provided in Supplemental Figure S4. By decoupling text and image interpretation and requiring explicit reasoning across both, this approach fosters greater interpretability and aligns with real-world clinical workflows, where imaging is used to support or adjust an initial hypothesis.

2.6. Evaluation Metric

To assess the performance of our model, we quantified the dissimilarity between the predicted diagnosis and the actual final diagnosis. In experiments incorporating self- consistency, we computed the average dissimilarity across multiple predictions per case to account for variability in model outputs. A key challenge in this evaluation lies in the inherent difficulty of exact string matching due to variations in medical terminology (e.g., acute posterior vitreous detachment and posterior vitreous detachment would register as a mismatch despite their clinical relationship). Furthermore, conventional semantic similarity metrics may not be entirely reliable in the medical domain, as certain diagnoses with distinct lexical representations may be synonymous (e.g., “dry eyes” and “keratoconjunctivitis sicca”).

To address this, we developed a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG)-based dissimilarity metric using SNOMED-CT (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms). While SNOMED-CT provides multiple API endpoints for querying medical concepts, our methodology specifically utilized two key endpoints to facilitate an accurate and structured evaluation of diagnostic dissimilarity. The first API endpoint was used to obtain the concept ID of a diagnosis via a search query (Table S2). The second API endpoint retrieved the Concept IDs of all ancestral terms associated with the given concept ID (Table S3). This allowed us to construct a DAG reflecting the hierarchical relationships among ophthalmic concepts.

To quantitatively evaluate the semantic gap between the predicted and reference diagnoses, we defined a hierarchical dissimilarity metric grounded on the SNOMED-CT ontology. The ontology is represented as a directed acyclic graph (DAG) G = (V,E), where each node v ∈ V corresponds to a SNOMED-CT concept, and each directed edge (u,v) ∈ E encodes an “is-a” hierarchical relationship. For any two concepts id1, id2 ∈ V, the shortest path distance distG(u,v) denotes the minimal number of directed “is-a” edges connecting u and v in G(edge weight = 1; distG(uv) = +∞ if no path exists). This formulation captures the semantic proximity between diagnoses in the clinical hierarchy.

Here, Lowest Common Ancestor (LCA) (id1, id2) denotes the lowest common ancestor of the two nodes within the SNOMED-CT hierarchy, defined as the ancestor with maximal depth in G. The constant max D defines the upper bound of dissimilarity for concept pairs that are semantically disconnected. Lower dissimilarity values indicate greater semantic proximity, whereas unrelated concepts approach max D. Shortest-path distances were obtained through standard graph traversal methods on the SNOMED-CT DAG to quantify semantic deviation between predicted and reference diagnoses.

This framework allows for an accurate and structured evaluation of model performance, ensuring that clinically relevant relationships between diagnoses are effectively captured. A worked example of the DAG-based dissimilarity metric is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Worked examples of diagnostic dissimilarity scores based on the DAG-based dissimilarity metric. The total dissimilarity score calculated is the sum of the distances from reference (Ref) diagnosis to LCA term, and the predicted (Pred) diagnosis to LCA term.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean, median, variance) were computed for the dissimilarity scores across all experimental conditions. Subgroup analyses were performed to examine the effect of each imaging modality (fundus, anterior segment, external, etc.) and the additional benefit of the chain-of-thought approach in cases with ambiguous visual cues.

An ablation study was performed to demonstrate the contribution of each individual component (pre-processing, textual consistency filtering, imaging, CoT) to the overall performance gain. Accuracy was also computed at varying prediction thresholds. As the dataset represents a multi-class, multi-candidate diagnostic task rather than a binary classification problem, accuracy was assessed to be a more interpretable performance metric over conventional measures of sensitivity and specificity.

For inferential analysis, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied for paired comparisons of dissimilarity scores between configurations.

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used LLaMA 3 8B Instruct model (version 3, Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, United States) for the purpose of sentence reconstruction, and GPT-4 (version 4, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) for the purpose of synthetic dataset generation. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Dataset

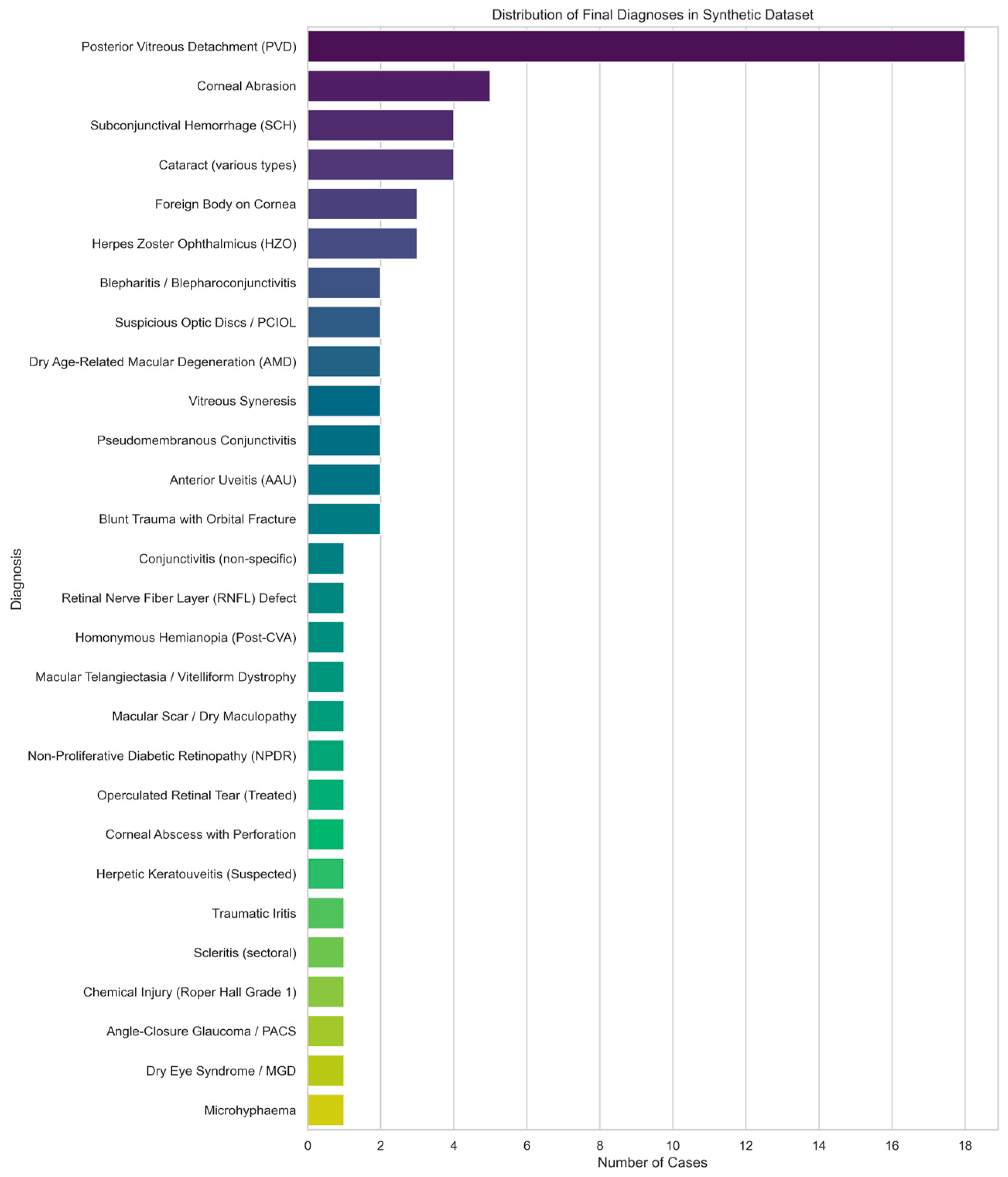

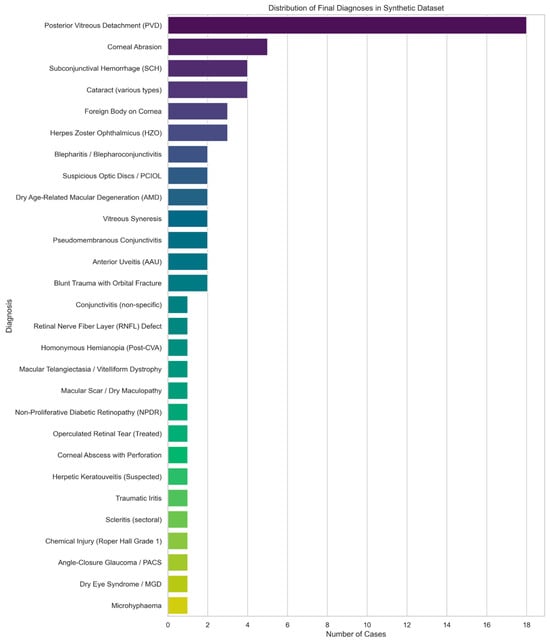

AA full list of the collected clinical data can be found in Supplemental Table S4. The distribution of diagnoses in the clinical dataset is represented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Distribution of diagnoses in Clinical dataset.

Of the 56 patient records in the clinical dataset, 40 had complete entries in 3 fields: Emergency Department (ED) History, Specialist Outpatient Clinic (SOC) history, and final diagnosis. The remaining 16 patient records had missing documentation in the ED history field.

Using the MPNet textual consistency cosine similarity threshold of 0.8, a total of 8 of the 96 reconstructions were found to have textually inconsistent outputs, resulting in a rejection rate of 8.33%.

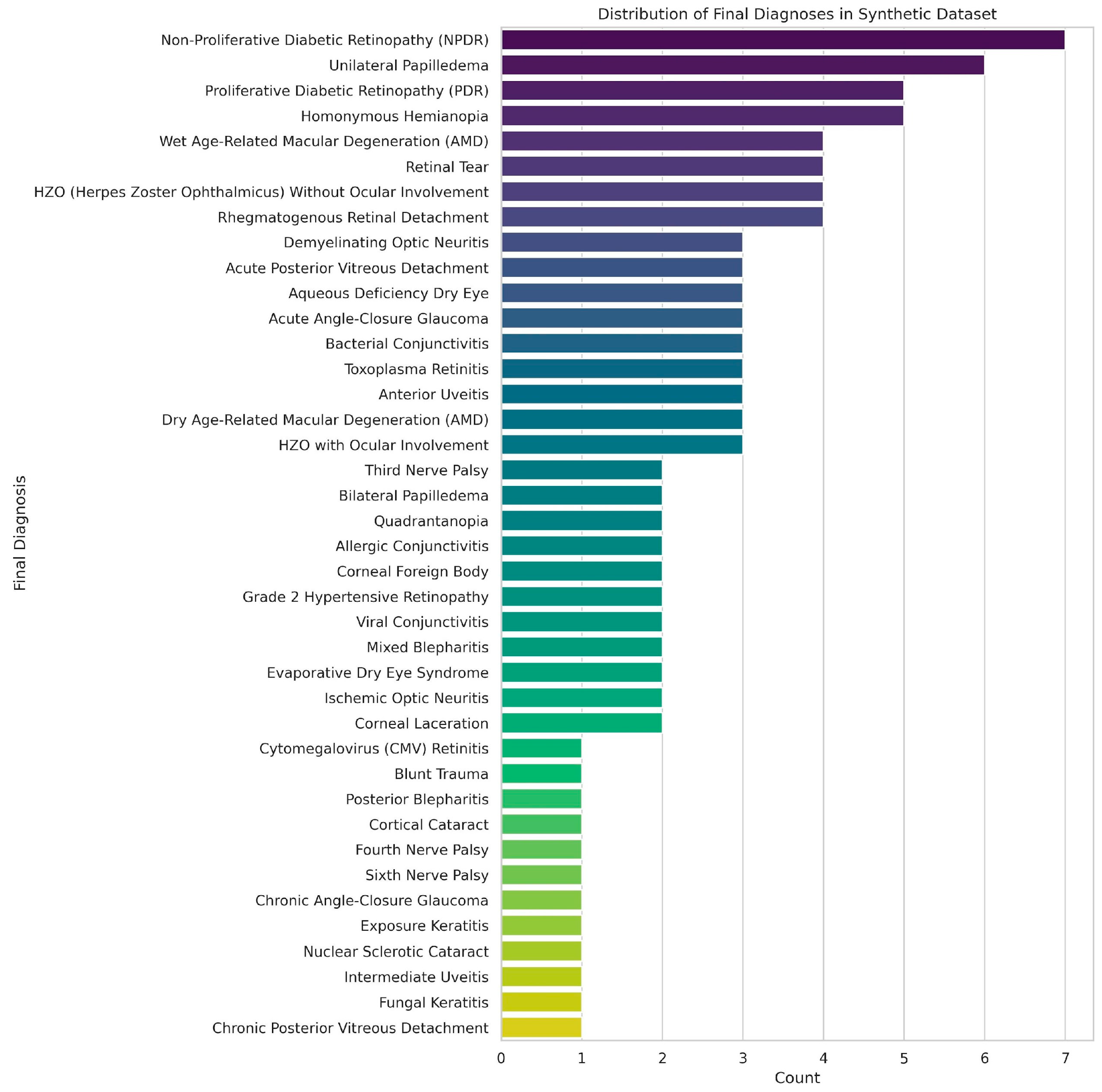

3.2. Synthetic Dataset

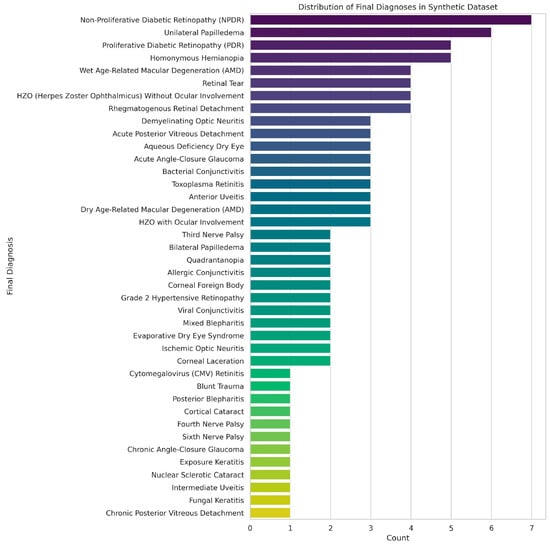

The synthetic dataset of 100 ophthalmic triage cases was designed to closely represent the variety and depth of cases encountered in the emergency and outpatient settings. The distribution of cases is represented in Figure 4, and included anterior segment (n = 40), posterior segment (n = 35) and extraocular (n = 25) diagnoses. Each case included standardised clinical history, physical examination findings, and ophthalmic imaging in one of several modalities: fundus photography, anterior segment with fluorescein staining, gonioscopy, Humphrey visual field testing, external ocular photographs, or 9-gaze photographs. This distribution enabled subgroup analyses by both diagnosis category and image modality.

Figure 4.

Distribution of diagnoses in Synthetic dataset.

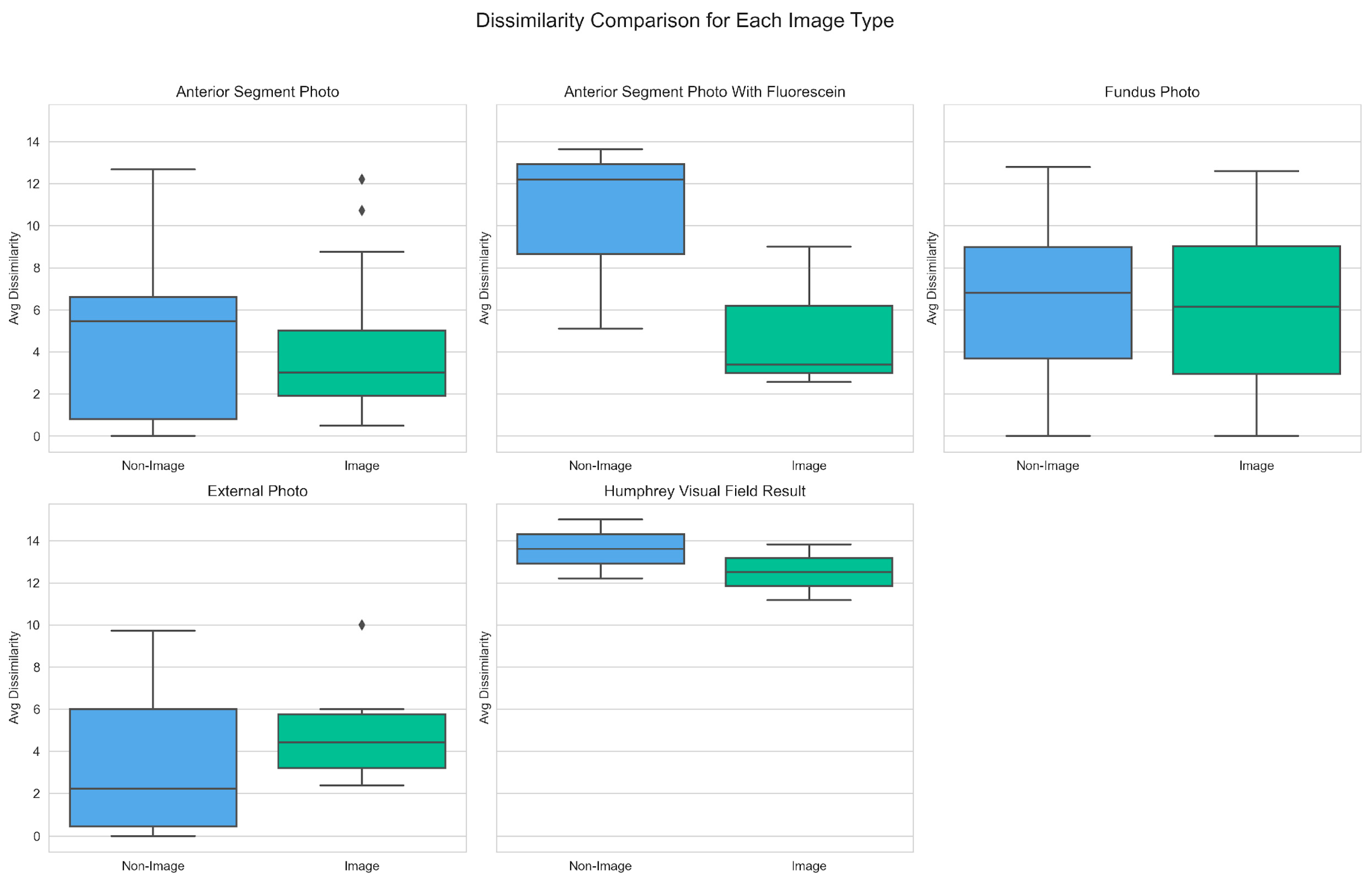

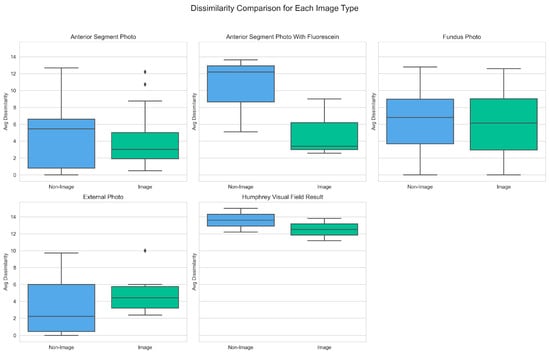

3.3. By Image Modality

Dissimilarity scores were grouped by image type and compared between image-assisted and non-image prompts to better understand how different ophthalmic image modalities influence diagnostic performance. As depicted in Figure 5, image-assisted prompts generally yielded lower median dissimilarity scores across most modalities.

Figure 5.

Box Plot of Dissimilarity Scores by Image Modality and Model Type (Non-image vs. Image). The ◆ symbols in the Anterior Segment Photo And External Photo diagrams represent outliers (occurring below the lower bound of Q1−1.5×IQR or above the upper bound of Q3+1.5×IQR).

Notably, the largest decrease in mean dissimilarity score was observed in the Anterior Segment with Fluorescein modality, from 10.31 (non-image) to 4.99 (image). A similar trend was noted for the median scores in this imaging modality, which decreased from 12.19 (non-image) to 3.39 (image). The largest mean dissimilarity scores were noted for the Humphrey Visual Field Result image modality, at 13.61 (non-image) and 12.51 (image). The only image modality where image assisted diagnoses yielded a higher mean dissimilarity score than text-only was External Photo, with a score of 3.55 (non-image) and 5.04 (image). Likewise, in this category, median scores also increased from 2.24 (non-image) to 4.43 (image).

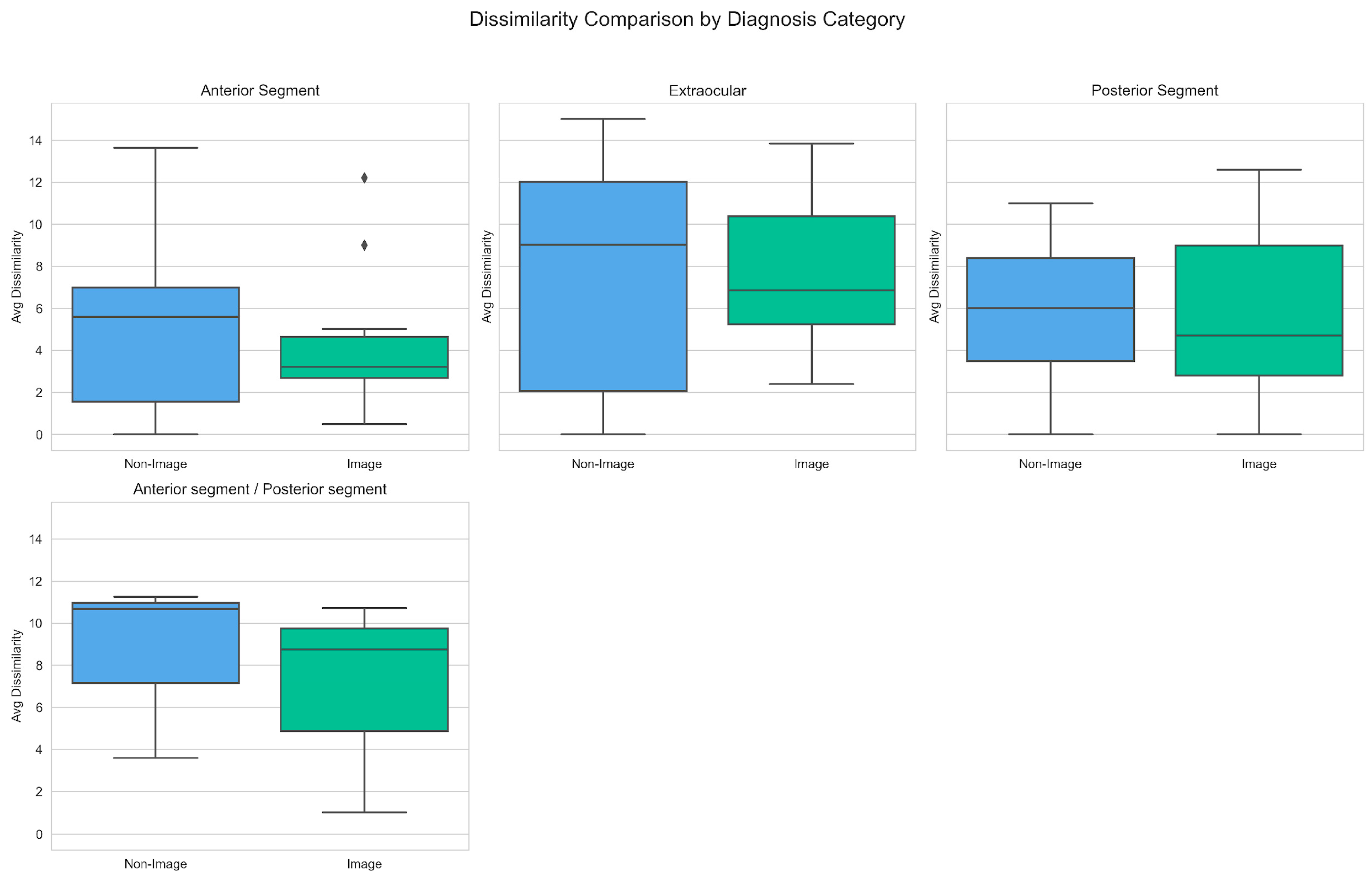

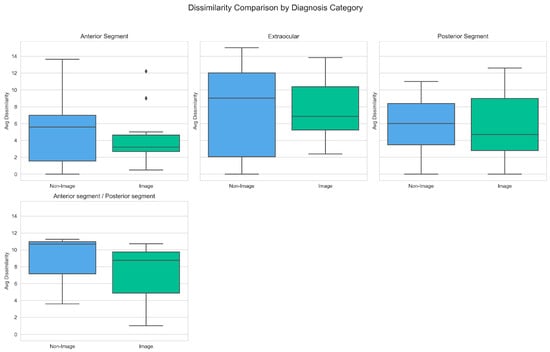

3.4. By Diagnosis Category

Dissimilarity scores were then grouped by diagnostic categories, to assess performance across different groups of ocular diagnoses. As seen in Figure 6, image-assisted prompts again produced lower dissimilarity scores across most categories.

Figure 6.

Box Plot of Dissimilarity Scores by Diagnosis Category and Model Type (Non-image vs. Image). The ◆ symbols in the Anterior Segment Photo diagram represent outliers (occurring below the lower bound of Q1−1.5×IQR or above the upper bound of Q3+1.5×IQR).

The largest decrease in mean dissimilarity score with image-assisted diagnosis was noted in the Anterior Segment (5.75 vs. 4.10) and Anterior Segment/Posterior Segment (8.51 vs. 6.82) diagnosis group. Similar trends were noted for the corresponding median scores of: Anterior Segment (5.59 vs. 3.20) and Anterior Segment/Posterior Segment (10.68 vs. 8.75). The only category where image assisted diagnosis resulted in a higher mean dissimilarity score was the Extraocular (7.39 vs. 7.56) diagnosis group. However, a converse trend was noted in the median scores of this group, with a decrease of 9.01 (non-image) vs. 6.86 (image).

In terms of specific diagnoses, visual data was noted to reduce diagnostic accuracy in specific cases. For anterior segment photos, dissimilarity scores were higher in Acute Angle Closure Glaucoma (+5.01), Cortical Cataract (+2.80) and Allergic Conjunctivitis (+2.22). For fundus photos, dissimilarity scores were notably higher in Arteritic Anterior Ischaemic Optic Neuropathy (+2.20). For gonioscopic imaging, the highest increase was noted for Chronic Angle Closure Glaucoma (+5.60). For External/Ocular Motility Photos, reduced accuracy was observed in Fourth Nerve Palsy (+8.12), Third Nerve Palsy (+5.00) and Surgical Third Nerve Palsy (+3.00).

3.5. Impact of Chain-of-Thought Reasoning

A total of 14 cases across 10 different diagnoses were identified to have ambiguous visual features. These cases underwent the additional CoT approach, which was noted to reduce dissimilarity scores. The Average Dissimilarity scores with and without CoT are depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Average Dissimilarity Scores between Image-only and Image + Chain-of Thought (CoT) Approaches for Selected Diagnoses.

Across the board, the inclusion of CoT prompts resulted in a consistent reduction in the dissimilarity scores. This was particularly notable in conditions such as Chronic Angle Closure Glaucoma (12.20 to 1.40) and Arteritic Anterior Ischaemic Optic Neuropathy (10.50 to 5.20). In addition, notable reductions in dissimilarity scores were seen for all diagnoses based on 9-gaze photographs.

3.6. Inferential Analysis of Model Comparisons

To determine whether differences in dissimilarity across prompting configurations were statistically significant, paired Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were applied. Sub-tests were applied to each diagnostic category (Anterior segment, Posterior segment, Extraocular) to provide insight on diagnostic accuracy for conditions from each of these groups. The comparison of dissimilarity scores between Direct vs. Image, and Image vs. CoT configurations, is represented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Paired Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Tests comparing Dissimilarity Scores between Direct and Image input configurations, and between Image and CoT image configurations.

The addition of image inputs was not found to have a statistically significant improvement in diagnostic accuracy compared to the Direct input configuration for the Overall, Anterior Segment and Posterior Segment categories. On the contrary, the addition of images caused a significant increase in the mean dissimilarity score for the extraocular category.

The addition of CoT inputs, however, caused a significant reduction in dissimilarity scores for both the Overall and Anterior Segment categories. This reduction was not found to be significant in the Posterior Segment and Extraocular categories.

3.7. Ablation Analysis and Top-k Diagnostic Accuracy Evaluation

An ablation analysis was conducted to evaluate the contribution of visual and reasoning components to model performance. We also evaluated diagnostic accuracy using top-k metrics, where we measure whether the correct diagnosis appears within the model’s top-k ranked predictions. Specifically, Top-1 accuracy captures the proportion of cases where the model’s first prediction matches the reference diagnosis, while Top-3 and Top-5 accuracies assess whether the correct diagnosis is present within the top three or five predictions, respectively. Table 5 summarizes the quantitative results across five configurations, displaying the Top-1, Top-3 and Top-5 accuracy readings.

Table 5.

Summary of Ablation analysis results. Lower dissimilarity and higher accuracy are indicative of better performance.

In our ablation study, the full multimodal configuration (Text + Image + CoT) achieved the highest Top-1 and Top-3 accuracies at 0.57 and 0.71, respectively, compared to 0.28 and 0.42 for the baseline text-only model. Intermediate configurations—such as Text + Image and Text + CoT—showed incremental gains, while omission of textual consistency filtering (“No Similarity Check”) resulted in degraded Top-3 accuracy (0.28).

4. Discussion

This pilot study provides three preliminary insights: firstly, that LLMs have the potential to play a supportive role in ophthalmology triage; secondly, that incorporating multimodal inputs appears to improve diagnostic accuracy; and lastly, that structured CoT prompting potentially improves diagnostic performance, particularly in visually ambiguous cases. These findings suggest solutions that are important in addressing limitations in existing LLM use in ophthalmology triage, including inconsistent clinical image interpretation, and inaccurate diagnostic reasoning processes. With recent reviews of LLMs reporting a rapidly expanding application area but noting heterogeneity in benchmark design and limited image-based input studies [15], this study offers notable findings which could significantly influence the way forward for LLMs in ophthalmology triage.

Multimodal inputs were noted to potentially improve diagnostic accuracy in LLM-assisted triage, as reflected by lower dissimilarity scores compared to text-only prompts. The average dissimilarity score dropped from 6.353 with text-only inputs to 5.235 when images were included. While this difference did not reach statistical significance, it does align with prior findings that multimodal systems can improve clinical decision-making when images are meaningfully integrated with clinical context [16,17].

However, the benefits of image-assisted diagnosis were not universal, with certain image modalities showing higher dissimilarity scores than text-only inputs. For example, the addition of external ocular photographs in image assisted diagnoses resulted in a statistically significant increase in dissimilarity scores, representing worsening diagnostic alignment. This phenomenon has been demonstrated in prior studies as well—Mikhail et al. demonstrated that GPT-4’s diagnostic accuracy was significantly lower when images were included, compared to text-only inputs [18]. A possible explanation is that LLMs trained only on general information may lack the depth of domain-specific knowledge necessary for a specialized task [19]—including the interpretation of complex ophthalmic images, such as complex or multi-panelled images. Other studies with similar findings give alternative explanations—such as the reliance of models on textual clues due to modality dominance rather than grounding in the visual evidence, leading to sidelining of the visual inputs [20].

4.1. Influence of Image Modality and Diagnosis Category on Dissimilarity

Dissimilarity scores varied across modalities, with anterior segment imaging demonstrating the greatest improvements. Specifically, fluorescein-stained images led to the most pronounced reduction in dissimilarity from 10.31 (text-only) to 4.99 (image-assisted), highlighting the utility of detailed, high-contrast imaging in surface-level pathologies. Conversely, image-assisted diagnosis of conditions requiring complex spatial interpretation, such as visual field defects, showed smaller improvements in diagnostic accuracy. This pattern is consistent with recent evaluations of VLMs, which reported that while they can leverage clear, structured imaging, they perform poorly on neuro-ophthalmic tasks such as optic disc swelling classification, even when domain-specific models or advanced prompting strategies are applied [21].

By diagnostic category, the greatest gains were observed in anterior and mixed anterior/posterior segment pathologies. On the other hand, diagnostic performance was diminished for extraocular conditions, such as cranial nerve palsies. A possible explanation is that clinical symptoms of extraocular conditions, such as diplopia or ptosis, are better conveyed through clinical history and examination findings rather than an ophthalmic image.

While our study demonstrates the value of a multimodal approach, it is important to acknowledge that the contribution of imaging may vary significantly across different ophthalmic sub-specialties. For instance, in neuro-ophthalmology, a sub-specialty with a heavy emphasis on patient history and neurological signs, a comprehensive analysis of clinical text alone can be highly effective. A study by Wang et al. found that a simple combination of patient history and chief complaint could predict a correct neuro-ophthalmology diagnosis with an accuracy of approximately 90% [22]. This suggests that for certain sub-specialties like neuro-ophthalmology, focusing on a robust text-only model may be more efficient and equally accurate, even reducing the risk of misinterpretation of ambiguous imaging prompts.

4.2. Chain of Thought Reasoning and Its Effect on Diagnostic Dissimilarity

The addition of CoT prompting consistently improved diagnostic accuracy across all tested conditions. Subgroup analysis revealed that this effect was the most pronounced in anterior segment diagnoses, while posterior segment and extraocular diagnoses did not reach statistical significance, likely due to limited sample sizes. Nonetheless, all non-zero differences favoured the CoT-enhanced approach, suggesting that structured reasoning may enhance consistency even in anatomically diverse conditions. These results corroborate earlier studies demonstrating that CoT enhances clinical reasoning by enforcing a stepwise, hypothesis-driven approach [7,23] capable of mimicking the diagnostic thought process utilized by specialists in a real-world clinical setting.

In the context of ophthalmology, CoT appears particularly effective in tasks involving complex diagnostic pathways or ambiguous visual findings, where simple visual-text alignment is insufficient. While no prior studies have assessed the use of CoT-augmented LLMs in the specific field of ophthalmology, other studies have verified the utility of CoT in improving the performance and consistency of LLMs in general diagnostic reasoning [24].

Our results further suggest that CoT may partially mitigate the limitations of VLMs in underperforming image modalities, such as external eye photographs or visual fields, by compensating for the lack of granular visual understanding with structured textual inference.

4.3. Significance of Study Findings

Our multi-modal diagnostic framework, while exploratory in nature, produces results which signal its potential utility in the future of ophthalmic triage. Firstly, the consistent improvement in diagnostic accuracy with addition of visual prompts suggests that multimodal inputs would achieve superior diagnostic alignment with real-world ophthalmic reasoning. With future validation on larger, real-world datasets, VLM-based systems may show promise as reliable front-line triage tools in the emergency departments or primary care settings.

Secondly, the study identifies certain ophthalmic diagnoses and imaging modalities in which the addition of imaging prompts degrades diagnostic accuracy. This underscores the importance of selecting appropriate modalities when deploying AI models in the real-world setting. It also reinforces that the deployment of AI-assisted triage should be tailored to align with the diagnostic utility of specific image types, while highlighting potential areas for model refinement such as in diagnosis of complex motility disorders, or interpretation of gonioscopic images.

Thirdly, the integration of CoT prompting further improved diagnostic alignment especially in cases with ambiguous visual cues or overlapping diagnoses. CoT-augmented models may thus be of utility to support decision-making in complex referrals, or during after-hour evaluations where subspecialty expertise is limited.

Lastly, the novel evaluation metric based on SNOMED-CT derived DAG accounts for semantic and clinical proximity between diagnoses. While still experimental in nature, it better reflects the realities of diagnostic uncertainty and interrelatedness in ophthalmic conditions. With the ability to capture this nuance, the model evaluation becomes more aligned with real-world triage needs where identifying the general category and disease urgency outweighs the need to diagnose a potentially rare or esoteric condition. The dissimilarity metric further serves as a quantitative indicator of diagnostic concordance between automated and clinician-assigned labels. While lower dissimilarity scores correspond to higher triage confidence, higher dissimilarity scores could indicate lower triage confidence, prompting secondary clinician review.

4.4. Limitations

While the findings of this study are promising, the following limitations must be acknowledged.

Firstly, the real-world clinical dataset only comprised only 56 cases from a single restructured hospital. Given the small sample size, the clinical cases were selected consecutively rather than via a specific randomized criterion. A small, geographically and institutionally constrained sample may not reflect broader patient populations, referral patterns, or documentation styles. External validation on independent cohorts across multiple centres is needed to assess robustness and transferability.

Secondly, the clinical dataset was also insufficient in terms of the quality of textual records, precluding its use in the experiments conducted. This prevented us from assessing the entire pipeline from pre-processing and textual consistency filtering to the performance of our model in terms of diagnostic triage.

Thirdly, our textual consistency filtering pipeline was based on textual similarity rather than factual verification and may therefore fail to identify subtle or domain-specific hallucinations. Future work incorporating fact grounding against structured ophthalmology databases may provide more rigorous hallucination detection.

Fourthly, this study’s reliance on a predominantly synthetic dataset introduces potential distributional bias. Although each synthetic case was reviewed by ophthalmologists, generative model phrasing may not fully capture the variability, noise, and incomplete documentation common in real-world triage notes. This limits the generalisability of our findings to routine clinical settings. The validation of synthetic cases was also performed through consensus review rather than independent double review, which precludes the computation of inter-rater agreement statistics. Future work could incorporate blinded dual validation to quantify reviewer concordance.

Fifthly, we did not include a clinician comparator arm or prospective assessment in actual triage workflows. Without head-to-head evaluation against human graders or assessment of real-time triage decisions, it remains unclear how the pipeline would perform under the time pressures and incomplete data of emergency care, limiting conclusions regarding its readiness for clinical application.

Lastly, while our SNOMED-CT DAG-based dissimilarity metric provides a nuanced measure of semantic proximity, it has inherent constraints. Uniform edge weighting ignores varying clinical significance across hierarchical jumps; polyhierarchical concepts may yield multiple LCAs, and our rule to select the deepest ancestor may not align with all clinical use cases. Manual mappings were required for a minority of terms not covered by the ontology, introducing potential mapping errors. A formal sensitivity analysis of the metric to synonymy, homonymy, and mapping inconsistencies remains for future work.

4.5. Clinical Perspectives and Future Developments

Given the exploratory nature of this study, several areas of future research remain before the proposed pipeline is ready for clinical deployment in ophthalmology triage. Key methodological enhancements include the development of a true hallucination detection workflow capable of identifying subtle or domain-specific factual inconsistencies, and the integration of continual learning mechanisms to enable adaptation to new disease entities and evolving diagnostic terminology, thereby maintaining long-term clinical relevance.

A proposed follow-up study would be a prospective, single-centre evaluation of the pipeline in a real-world setting. This study could be conducted in a tertiary centre over a defined period, enrolling a minimum of several hundred consecutively selected emergency eye cases. Unlike the present feasibility study, the prospective phase would rely entirely on clinician-generated free-text and fundus image data, hence assessing the model’s performance under operational conditions.

Through a silent deployment of the pipeline in which the model operates concurrently with routine clinical workflows without influencing triage decisions, comparison of automated and clinician-assigned diagnoses could be made. This provides a direct measure of real-world accuracy, interpretability and systemic reliability. Data from this phase would be useful in calibration of dissimilarity thresholds corresponding to acceptable levels of diagnostic concordance. Successful completion of this step would provide the necessary evidence to transition from pilot feasibility to a clinically ready deployment.

5. Conclusions

This pilot study demonstrates feasibility of a multimodal diagnostic framework using real and synthetic cases, with preliminary results suggesting that image integration and CoT reasoning may improve diagnostic alignment. Larger real-world datasets and benchmarking with standard metrics are needed before clinical application. The novel use of a SNOMED-CT-based DAG metric to evaluate diagnostic dissimilarity shows potential as a more nuanced and clinically relevant performance metric than conventional classification accuracy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcto3040025/s1, Figure S1: Complete Sentence Reconstruction Prompt, Figure S2: Direct Prompt for Diagnosis, Figure S3: Multi-Modality Prompt, Figure S4: CoT Prompt, Table S1: Medical Acronym dictionary used in Textual consistency pipeline, Table S2: Workflow for Concept ID Extraction from SNOMED-CT API, Table S3: Workflow for Ancestor Concept ID Extraction from SNOMED-CT API, Table S4: Ophthalmology triage clinical dataset.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.L.; investigation, C.G. and J.N.; methodology, J.N., X.F. and K.L.; resources, W.Y.A., C.S. and A.L.; software, J.N. and X.F.; supervision, K.L.; visualization: C.G. and J.N.; writing—original draft, C.G. and J.N.; writing—review and editing, W.Y.A., J.W.Z., C.S., A.L., X.F. and K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Domain Specific Review Board of the National Healthcare Group (reference number 2023/00348, approval date: 10 October 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived by the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB) due to complete anonymization and de-identification of patient information prior to analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used LLaMA 3 8B Instruct model (version 3, Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, United States) for the purpose of sentence reconstruction, and GPT-4 (version 4, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) for the purpose of synthetic dataset generation. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mir, T.A.; Mehta, S.; Qiang, K.; Adelman, R.A.; Del Priore, L.V.; Chow, J. Association of the Affordable Care Act with Eye-Related Emergency Department Utilization in the United States. Ophthalmology 2022, 129, 1412–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khou, V.; Ly, A.; Moore, L.; Markoulli, M.; Kalloniatis, M.; Yapp, M.; Hennessy, M.; Zangerl, B. Review of Referrals Reveal the Impact of Referral Content on the Triage and Management of Ophthalmology Wait Lists. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e047246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, F.F.; Zumbrunn, T.; Ciprian, S.; Stephan, F.-P.; Woy, N.; Bingisser, R.; Nickel, C.H. Undertriage in Older Emergency Department Patients—Tilting against Windmills? PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Jiang, B.; Zhao, T.; Guo, X.; Tan, Y.; Wang, Y. Trends in the Global Burden of Vision Loss among the Older Adults from 1990 to 2019. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1324141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascella, M.; Semeraro, F.; Montomoli, J.; Bellini, V.; Piazza, O.; Bignami, E. The Breakthrough of Large Language Models Release for Medical Applications: 1-Year Timeline and Perspectives. J. Med. Syst. 2024, 48, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazi, Z.A.; Peng, W. Large Language Models in Healthcare and Medical Domain: A Review. Informatics 2024, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.11903. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Du, J.; Zhou, J.T.; Liu, Z. MedCoT: Medical Chain of Thought via Hierarchical Expert. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Miami, FL, USA, 12–16 November 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics: Miami, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 17371–17389. [Google Scholar]

- Tanya, S.M.; Nguyen, A.X.; Buchanan, S.; Jackman, C.S. Development of a Cloud-Based Clinical Decision Support System for Ophthalmology Triage Using Decision Tree Artificial Intelligence. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2023, 3, 100231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Ma, R.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, M.; Lu, J.; Cheng, Q.; Liao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Development and Evaluation of Multimodal AI for Diagnosis and Triage of Ophthalmic Diseases Using ChatGPT and Anterior Segment Images: Protocol for a Two-Stage Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1323924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sittig, D.F.; Singh, H. Recommendations to Ensure Safety of AI in Real-World Clinical Care. JAMA 2025, 333, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, M.; Flanagan, M.E.; Ernst, K.; Cottingham, A.H.; Rattray, N.A.; Franks, Z.; Savoy, A.W.; Lee, J.L.; Frankel, R.M. Accuracy, Thoroughness, and Quality of Outpatient Primary Care Documentation in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, S.; Du, W. Challenges of Integrating Chatbot Use in Ophthalmology Diagnostics. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2024, 142, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihalache, A.; Huang, R.S.; Popovic, M.M.; Patil, N.S.; Pandya, B.U.; Shor, R.; Pereira, A.; Kwok, J.M.; Yan, P.; Wong, D.T.; et al. Accuracy of an Artificial Intelligence Chatbot’s Interpretation of Clinical Ophthalmic Images. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2024, 142, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- See, Y.K.C.; Lim, K.S.A.; Au, W.Y.; Chia, S.Y.C.; Fan, X.; Li, Z.K. The Use of Large Language Models in Ophthalmology: A Scoping Review on Current Use-Cases and Considerations for Future Works in This Field. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2025, 9, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Li, M.; Liu, L.; Zhong, L.; Xiao, J.; Lou, B.; Zhong, X.; Chen, Y.; Huang, W.; et al. EE-Explorer: A Multimodal Artificial Intelligence System for Eye Emergency Triage and Primary Diagnosis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 252, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, K.; Nishida, T.; Kitaguchi, Y.; Kitazawa, K.; Miyake, M. Image Recognition Performance of GPT-4V(Ision) and GPT-4o in Ophthalmology: Use of Images in Clinical Questions. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2025, 19, 1557–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhail, D.; Milad, D.; Antaki, F.; Milad, J.; Farah, A.; Khairy, T.; El-Khoury, J.; Bachour, K.; Szigiato, A.-A.; Nayman, T.; et al. Multimodal Performance of GPT-4 in Complex Ophthalmology Cases. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaskas, G.; Papadopoulos, H.; Pappa, D.; Loisel, Q.; Chastin, S. A Framework for Domain-Specific Dataset Creation and Adaptation of Large Language Models. Computers 2025, 14, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, T.; Diao, J.A.; Rajpurkar, P.; Rodman, A.; Manrai, A.K. Multimodal Foundation Models Exploit Text to Make Medical Image Predictions. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.05591. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.Z.; Nguyen, T.T.; Moss, H.E. Performance of Vision Language Models for Optic Disc Swelling Identification on Fundus Photographs. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1660887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.Y.; Asanad, S.; Asanad, K.; Karanjia, R.; Sadun, A.A. Value of Medical History in Ophthalmology: A Study of Diagnostic Accuracy. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 2018, 30, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WU, J.; Wu, X.; Yang, J. Guiding Clinical Reasoning with Large Language Models via Knowledge Seeds. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.06609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-K.; Chen, W.-L.; Chen, H.-H. Large Language Models Perform Diagnostic Reasoning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.08922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).