Abstract

Research Question and Objective: While the number of pharmacoepidemiological studies on stimulant-based ADHD medications has expanded rapidly in recent years, likely due to the stimulant shortage, few studies have analyzed non-stimulant ADHD medications from a pharmacoepidemiological perspective. Such research is important because a significant number of individuals with ADHD have medical or psychiatric conditions that preclude stimulant use. Furthermore, no studies, to our knowledge, have analyzed atomoxetine exchanges on the black market. In this report, we seek to fill both these gaps in the research by analyzing black market diversions of atomoxetine, a non-stimulant medication for ADHD. As ADHD medication diversion is a growing issue, we also hypothesize the pharmacoepidemiologic contributors to and implications of such diversion. Method: This study analyzed black market atomoxetine purchases entered on the web-based platform StreetRx between January 2015 and July 2019. Data included the generic drug name, dosage, purchase price, date, and location in the United States. The mean price per milligram was determined and a heatmap was generated. Results: The average price per milligram of 113 diverted atomoxetine submissions was USD 1.35 (±USD 2.76 SD) (Median = USD 0.05, Min = USD 0.01, Max = USD 20.00). The states with the most submissions included Michigan (11), Pennsylvania (9), Indiana (8), and Ohio (8). Conclusion: The cost per milligram of atomoxetine on the black market is over 50 times the cost per milligram of the generic prescribed form. Future qualitative studies should investigate reasons why individuals are motivated to purchase atomoxetine, a non-stimulant medication, on the black market (recreational vs. nootropic vs. other clinical uses).

1. Introduction

Atomoxetine became the first non-stimulant medication to receive US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in 2002. It is typically used as a second-line medication for adults and, less commonly, children with contraindications to first-line medications such as stimulants including methylphenidate and amphetamines [1,2,3]. As atomoxetine is unscheduled, indicating a low abuse potential, it may be particularly useful for pediatric patients and their families who prefer to avoid a controlled substance [4]. When administered at approved dosages, atomoxetine may require several weeks of treatment before therapeutic effects are attained, in comparison to methylphenidate and amphetamines, which reach peak effects either immediately or in hours for extended-release formulations [5,6]. Atomoxetine carries an FDA warning of potential suicidal ideation (irritability, agitation, thoughts of suicide/self-harm) in children and adolescents and instructs the cessation of use if any of these rare effects occur. Therefore, children and adolescents taking the medication should be monitored for behavioral changes, suicidal thinking/behavior, and/or clinical worsening [7,8]. Rarely, atomoxetine has also been associated with seizures and cardiac effects; however, these side effects are often more pronounced with stimulant medications. Based on the decreased efficacy reported in some studies and the aforementioned black box warning, atomoxetine is generally considered second line to stimulant medications [9]. Nonetheless, atomoxetine may be preferred for the treatment of certain populations who have contraindications to stimulant use, such as patients with comorbid anxiety and those with a drug misuse history [4]. It may also be preferred in patients that experience unwanted side effects to stimulant use, such as mood instability or tic disorders [8,10].

Contrary to the first-line stimulants classified as Schedule II drugs in the US, atomoxetine is unscheduled [11,12]. The classification is primarily due to its mechanism of action as a selective inhibitor of the presynaptic norepinephrine transporter, which has no notable affinity for central receptors (dopamine transporters, GABAA receptors, and opioid μ receptors) [12]. Increasing dopamine produces the “high” associated with methylphenidate and lisdexamfetamine, which is not seen with atomoxetine use [5,12]. However, rat studies have found that atomoxetine increases dopamine in the prefrontal cortex and may also exert its effect through non-dopaminergic mechanisms involving prefrontal histamine release [13].

The purpose of this report was to analyze black market diversions of atomoxetine, a non-stimulant medication for ADHD, and hypothesize the pharmacoepidemiologic contributors to and implications of such diversion. This study analyzed black market atomoxetine purchases entered on the web-based platform StreetRx between January 2015 and July 2019.

2. Results

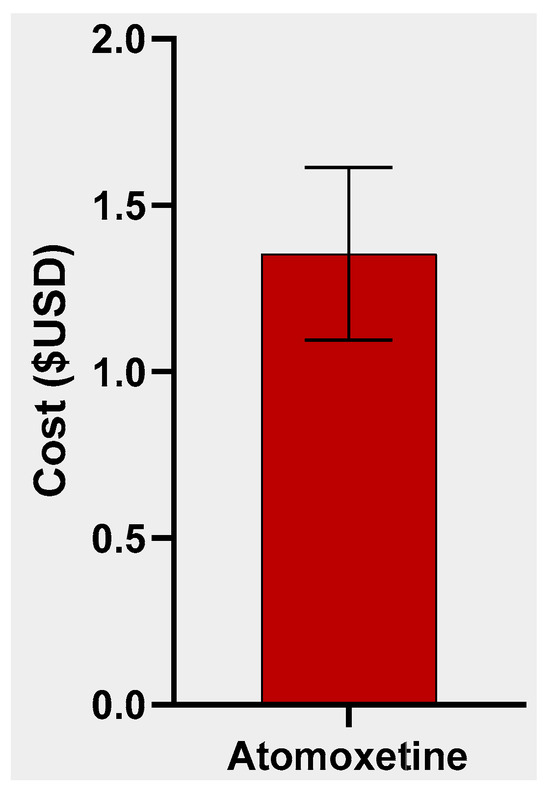

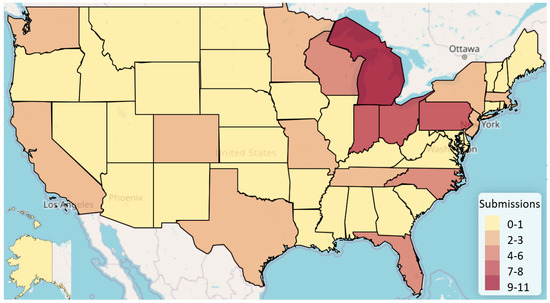

A total of 113 atomoxetine submissions were entered on StreetRx from 2015 to 2019. The average price per milligram of diverted atomoxetine (including generic and brand name) was USD 1.35 with a standard deviation of USD 2.76 (Figure 1, Supplemental Figure S1). Generic atomoxetine averaged a modest price per milligram of USD 0.08 (N = 8; SD = USD 0.03) and brand name atomoxetine (Strattera) averaged a price per milligram of USD 1.45 (N = 105; SD = USD 2.84). Before FDA approval of the generic form of atomoxetine, the average price per milligram was USD 1.38 (N = 65; SD = USD 2.86), whereas after approval of a generic form of atomoxetine, the average price per milligram was USD 1.31 (N = 48; SD = USD 2.68). Ninety-seven of the entries were in a 10 mg dose, four entries in an 18 mg dose, two entries in a 25 mg dose, nine entries in a 40 mg dose, and one entry in a 60 mg dose. The most submissions occurred in Michigan (11), followed by Pennsylvania (9), Indiana (8), and Ohio (8). Thirteen states (AK, AR, DE, HI, IA, LA, MS, MT, NM, ND, RI, VT, WI) did not have any submissions (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Average (±SEM) cost per mg of diverted atomoxetine.

Figure 2.

Heat map displaying diverted atomoxetine submissions per state.

3. Discussion

This novel report analyzed 113 black market atomoxetine exchanges, which primarily took place in midwestern states (Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Pennsylvania). Our findings indicate that atomoxetine was diverted at non-nominal rates and at a higher price than centrally acting agents during the study period. It is notable that individuals choose to purchase atomoxetine at an average price of USD 1.35/mg rather than the centrally acting stimulant drugs amphetamine or lisdexamfetamine, which averaged USD 0.53 and USD 0.28 per mg per exchange entered on StreetRx, respectively [14]. According to GoodRx, the lowest prescribed price per milligram (ppm) cost of atomoxetine is USD 0.024/mg, which is much lower than its black market price of USD 1.35/mg [15]. Also noteworthy was the thirteen-fold more submissions for the brand name atomoxetine compared to the generic form and that the price per mg of generic atomoxetine was one-eighteenth that of the brand name. This could be at least partially attributed to a generic form of atomoxetine not becoming available on the market until mid-2017, with the average price of black market sales dropping USD 0.08 per milligram after it did. Taken together, these data suggest that individuals who have a prescription and subsequently sell atomoxetine on the black market could be making a substantial profit.

Given that atomoxetine has not been shown to act through the striatal dopaminergic pathways through which drugs of abuse typically act, it is interesting that StreetRx users would choose to purchase it at a higher price than its more addictive counterparts (e.g., amphetamines). The next logical question becomes: what are the characteristics of black-market atomoxetine purchasers?

There are several possible reasons for the demand for diverted atomoxetine. First, non-ADHD populations or diagnosed individuals who lack medication access may desire cognitive enhancement but prefer not to experience certain effects of stimulants [16]. Moreover, FDA approval of the first generic atomoxetine in 2017 likely increased public awareness and willingness to trust the drug. However, it is possible that it was not available in all pharmacies from 2017 to 2019, or that some individuals with ADHD simply lacked prescriptions due to the recency of its approval. It is also possible that some individuals experience desirable neuropsychotropic effects even though atomoxetine is not a stimulant. There is an Erowid report of a teenager taking more than the recommended dose and becoming hyperverbal, an experience he rated favorably [17]. Additional anonymous reports describe the synergistic effects of atomoxetine with caffeine or mirtazapine [15,18]. Second, atomoxetine could be used as a party drug for its noradrenergic effects with the intention of offsetting the depressant effects of alcohol. Additionally, several studies have reported that the CYP2D6 genotype can affect atomoxetine’s efficacy. Atomoxetine is metabolized by the P450 2D6 enzyme, and poor CYP2D6 metabolizers have been found to experience superior treatment outcomes as measured by a reduction in ADHD symptoms. However, poor metabolizers also experience an increase in medication-related side effects relative to extensive CYP2D6 metabolizers [19,20]. It is possible that certain purchasers captured in this study had the CYP2D6 genotype and were motivated by their superior response to atomoxetine. As for possible drug interactions, any other medications (e.g., paroxetine or fluoxetine) that inhibit this enzyme can raise the serum atomoxetine levels by three- or four-fold [21]. It is possible that some StreetRx atomoxetine entries were by individuals who combined it with any of these drugs in order to produce an unusual or enhanced effect.

It is also possible that a subset of black market atomoxetine purchasers were well-versed in its “off-label” uses and purchased it to self-treat a number of conditions. For example, a number of studies have documented atomoxetine’s effectiveness for treating obesity and eating disorders (binge eating disorder and anorexia nervosa binge/purge type), as well as concurrent substance use disorders and ADHD [22,23,24]. In the past, it was used to aid tobacco cessation and treat the symptoms of nicotine withdrawal [25]. It is also possible that purchasers were using atomoxetine to decreases cravings associated with substance use, produce sexual effects such as spontaneous ejaculation, or limit body weight, given existing research documenting all of these effects [26,27,28]. Finally, it is possible that some purchasers are simply unaware of atomoxetine’s nonstimulant status and believe they are purchasing something no different from amphetamines.

The next logical question is: to what extent should self-treatment with atomoxetine via black market purchasing be of concern from a public safety perspective? While some atomoxetine purchases documented in this study may represent patients attempting to self-treat a condition, data on atomoxetine exposure reports from the National Poison Database System (NPDS) suggest that some who purchased diverted atomoxetine had the intention of misuse. In a study of 20,032 atomoxetine exposures reported to the NPDS between 2002 and 2010, 10,608 (85.8%) cases were unintentional, 1079 (8.7%) were reported as suicide attempts, and 629 (5.1%) cases were reported as abuse [29]. Of the 12,370 single-agent exposures, 21 major adverse medical events were reported, including 8 tachycardic episodes, 9 seizures, 6 comas, and 1 ventricular dysrhythmia. The authors concluded that atomoxetine is generally safe and while seizures and cardiac events can occur, seizures are exceedingly rare and cardiac events are most often limited to tachycardia and hypertension.

Additional studies have corroborated these findings. During a 2-year period when 2.233 million adult and pediatric patients were exposed to atomoxetine, 8 out of 100,000 patients reported seizures [27]. Moreover, despite case reports of pediatric seizure associated with atomoxetine use, large studies have proven that the risk of atomoxetine-induced seizure is exceedingly low [30]. A review of clinical trial data reported an increased seizure rate of only 0.1–0.2% among children with ADHD who took atomoxetine compared to the placebo group [31]. Regarding cardiac effects, a regional poison control center study of 40 pediatric atomoxetine overdoses found that no arrythmias occurred [32]. Furthermore, the researchers concluded that activated charcoal and observation was adequate for management of tachycardia, hypertension, vomiting, and drowsiness following overdose.

Thus, while seizures and cardiac events are understood to be extremely rare side effects, the US label and the European Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) warns atomoxetine users of two more common side effects: an increase in heart rate and blood pressure. A study of 8417 pediatric patients found that most experienced modest increases in heart rate and blood pressure (<20 bpm and <15 to 20 mmHg) and 8–12% experienced large increases (≥20 bpm and ≥15 to 20 mmHg); however, blood pressures normalized within 2 years for both groups [33]. To what extent should these increases be of concern? One study concluded that off-label use of atomoxetine was generally safe, provided that it is not given to patients with serious cardiac conditions, Tourette’s syndrome, a history of urinary outflow obstruction, an increased risk of seizure or narrow-angle glaucoma, or those who are pregnant or lactating [31].

Other studies have recommended that patients’ heart rate and blood pressure be monitored and a cardiovascular risk assessment performed before prescribing [34,35,36]. Further research is needed to determine baseline cardiac function necessary for the prescribing of atomoxetine and other ADHD medications.

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted all aspects of healthcare, including drug market trends, and ADHD medications were no exception. Total psychostimulant prescriptions increased by 10% among American adolescents and adults in 2020–2021 compared with a mere 1.4% increase from 2016 to 2020 [37,38]. This sharp increase in stimulant demand unmet by an increase in supply has resulted in a shortage of first-line ADHD medications, both brand name and generic amphetamines. Other factors, such as the paucity of pediatric mental health providers, may have also contributed to the shortage, which persists into the present. This has forced some with ADHD to discontinue treatment or resort to second-line alternatives, including atomoxetine [39]. While advocates and researchers have called for government intervention to address the Adderall crisis, an additional proposition has been the use of precision psychiatry in ADHD prescribing. This would involve clinicians using prediction models to prescribe currently available ADHD medications based on the specific characteristics of the patient [40]. Precision psychiatry could potentially allow for patients better suited to atomoxetine treatment to be identified and treated. It is unclear how a potential spike in legitimate prescribing of atomoxetine could affect black market sales. However, as the stimulant shortage continues, further research into its impact on atomoxetine diversion is warranted.

4. Methods

4.1. Data Source

Since 2010, StreetRx has served as a crowdsourced data platform through which buyers and/or sellers submit information on black market drug exchanges [41]. Specifically, StreetRx gathers information on the price, quantity, and location of a given diverted drug exchange directly from purchasers in the United States, Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. StreetRx partners with the Researched Abuse, Diversion, and Addiction-Related Surveillance System (RADARS), which also collects data on prescription drugs that are abused, misused, and diverted [41]. A previous validation study of the platform found a strong correlation with law enforcement reports of street prices [42]. Data included the generic drug name, drug dosage, purchase price, and date and location of submission in the United States from 2015 to 2019 for atomoxetine. The objective of this study was to characterize the pattern of atomoxetine reports to StreetRx.

4.2. Procedures

Access to StreetRx data reports was granted via a data use agreement between Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine and Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Safety Department of the Denver Health and Hospital Authority. Data included the generic drug name, drug dosage, purchase price, and date and location of submission in the United States from 2015 to 2019 for atomoxetine. Procedures were approved by the University of New England IRB 19.06.07-007 on 7 June 2019.This study was conducted in 2021 and manuscript creation took place 2021–2022.

4.3. Analysis

The mean price per milligram was computed using GraphPad Prism v. 9.4.0 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA). Figures were constructed using GraphPad Prism v. 9.4.0. Heatmapper was used to represent the location of submissions [43].

5. Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of this study is that the data source allowed for comparison of the per-unit price of atomoxetine to both the price of other ADHD medications and the price of Strattera, the brand name of atomoxetine. The findings in this study should be interpreted with caution due to several factors. First, the relatively low number of atomoxetine submissions to StreetRx, particularly for the generic formulation, limits reliability. An additional limitation is that the majority of submissions were from individuals located in Michigan and Pennsylvania, while thirteen states, primarily in the Midwest, had zero submissions.

One notable strength of the data source, StreetRx, from a data collection standpoint, is that it provides continuous data capable of capturing rapid shifts in market dynamics [42,44]. Given the clandestine nature of black-market drug exchanges, such data would likely otherwise go unrecognized by the pharmacoepidemiology community. However, StreetRx also has several weaknesses as a data source, namely that data entered does not go through a verification process; thus, falsification of data and misclassification (e.g., entering data pertaining to a brand name drug as generic) is possible. However, our data analysis partially corrected for potential falsification and misclassification by excluding outliers. Additionally, StreetRx does not allow entries on certain factors that may influence price, such as potency and bulk purchasing [44]. While StreetRx is validated as representative of black-market trends, some extent of purchaser nonsubmission is inevitable. Therefore, data captured in this study likely underestimates the number of black-market atomoxetine exchanges. Lastly, ideally we would have been able to analyze StreetRx atomoxetine submissions from 2015 to 2023, but unfortunately, our data source contained data only through 2019. Therefore, our ability to contextualize the black market data within the current context of the Adderall shortage is limited.

6. Conclusions

This analysis identified 113 atomoxetine submissions with a street price of USD 1.35/mg. Additional pharmacodynamic studies on atomoxetine’s mechanism of action could help to explain its effects and thus elucidate why it might be desirable for cognitive enhancement or recreational use. Future qualitative studies should investigate the reasons why individuals are purchasing diverted atomoxetine on the black market (i.e., for recreational vs. nootropic vs. other clinical uses). If it is for therapeutic use (e.g., purchasing the drug on the black market to self-treat ADHD) or recreational use is identified, public health strategies could respond by either expanding legitimate atomoxetine access or limiting diversion.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pharma2040027/s1, Figure S1: Atomoxetine average price per milligram superimposed on a violin plot (Median = USD 0.05, Min = USD 0.01, Max = USD 20.00).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.J.P. and S.A.R.; methodology, all authors; software, all authors; validation, B.J.P.; formal analysis, S.A.R. and D.S.D.; investigation, S.A.R. and D.S.D.; resources, B.J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.R. and D.S.D.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, all authors; supervision, B.J.P.; project administration, B.J.P.; funding acquisition, B.J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This project was determined to be not human subjects research by the University of New England IRB (19.06.07-007) on 7 June 2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data may be made available upon contacting StreetRx.

Acknowledgments

The technical assistance of Kenneth ‘Mac’ McCall is greatly appreciated. StreetRx is recognized for making drug diversion information available.

Conflicts of Interest

BJP was (2019–2021) part of an osteoarthritis research team supported by Eli Lilly and Pfizer. The other authors had no disclosures.

References

- Cortese, S.; Adamo, N.; Giovane, C.; Mohr-Jensen, C.; Hayes, A.; Carucci, S.; Atkinson, L.; Tessari, L.; Banaschewski, T.; Coghill, D.; et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2018, 5, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraone, S.V.; Banaschewski, T.; Coghill, D.; Zheng, Y.; Biederman, J.; Bellgrove, M.A.; Newcorn, J.H.; Gignac, M.; Al Saud, N.M.; Manor, I.; et al. The World Federation of ADHD International Consensus Statement: 208 Evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 128, 789–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, D.; Zhang, M.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Jiao, J.; Huang, Y. Noradrenergic genes polymorphisms and response to methylphenidate in children with ADHD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2021, 100, e27858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnock-Jones, K.; Keating, G. Atomoxetine. Pediatr.-Drugs 2009, 11, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedder, D.; Patel, H.; Saadabadi, A. Atomoxetine; StatPearls: St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493234/ (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Jaeschke, R.; Sujkowska, E.; Sowa-Kućma, M. Methylphenidate for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: A narrative review. Psychopharmacology 2021, 238, 2667–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.; Samuel, S.; Patel, D. Pharmacologic management of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: A review for practitioners. Transl. Pediatr. 2018, 7, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliszka, S. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2007, 46, 894–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Wu, D.D.; Guo, H.L.; Hu, Y.H.; Xia, Y.; Ji, X.; Fang, W.R.; Li, Y.M.; Xu, J.; Chen, F.; et al. The mechanism, clinical efficacy, safety, and dosage regimen of atomoxetine for ADHD therapy in children: A narrative review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 780921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biederman, J.; Monuteaux, M.C.; Doyle, A.E.; Seidman, L.J.; Wilens, T.E.; Ferrero, F.; Morgan, C.L.; Faraone, S.V. Impact of executive function deficits and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on academic outcomes in children. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 72, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bymaster, F.P.; Katner, J.S.; Nelson, D.L.; Hemrick-Luecke, S.K.; Threlkeld, P.G.; Heiligenstein, J.H.; Morin, S.M.; Gehlert, D.R.; Perry, K.W. Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rat: A potential mechanism for efficacy in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002, 27, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyaya, H.; Desaiah, D.; Schuh, K.; Bymaster, F.; Kallman, M.; Clarke, D.; Durell, T.; Trzepacz, P.; Calligaro, D.; Nisenbaum, E.; et al. A review of the abuse potential assessment of atomoxetine: A nonstimulant medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychopharmacology 2013, 226, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, W.; Johnson, D.; Schmidt, A.; Rollema, H. Methylphenidate and atomoxetine increase histamine release in rat prefrontal cortex. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 8, 96–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasch, K.; Smith, L.; Roe, S.; Groff, E.; DeSalve, D.; McCall, K.; Nichols, S.; Piper, B. Examination of diversion of ADHD pharmacotherapies with StreetRx. Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine, Scranton, PA, USA. 2023; manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Doctor Faust. Effective Alternative: Atomoxetine (Strattera) & Mirtazapine (Remeron). Erowid. 6 November 2009. Available online: https://erowid.org/experiences/exp.php?ID=72740 (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Babicki, S.; Arndt, D.; Marcu, A.; Liang, Y.; Grant, J.; Maciejewski, A.; Wishart, D. Heatmapper: Web-enabled heat mapping for all. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 44, W147–W153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBVsoldier. Not What I Expected: Atomoxetine (Strattera). Erowid. 3 September 2008. Available online: https://erowid.org/experiences/exp.php?ID=61063 (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Terra. Avid Caffeiner Switches to Atomoxetine: Strattera (Atomoxetine). Erowid. 1 April 2014. Available online: https://erowid.org/experiences/exp.php?ID=103020 (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Brown, J.T.; Bishop, J.R.; Sangkuhl, K.; Nurmi, E.L.; Mueller, D.J.; Dinh, J.; Gaedigk, A.; Klein, T.E.; Caudle, K.E.; McCracken, J.T.; et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guideline for cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 genotype and atomoxetine therapy. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 106, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelson, D.; Read, H.; Ruff, D.; Witcher, J.; Zhang, S.; McCracken, J. CYP2D6 and clinical response to atomoxetine in children and adolescents with ADHD. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2007, 46, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawant, S.; Daviss, S. Seizures and prolonged QTc with atomoxetine overdose. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollins, S.H. A qualitative review of issues arising in the use of psycho-stimulant medications in patients with ADHD and co-morbid substance use disorders. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2008, 24, 1345–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunill, R.; Castells, X.; González-Pinto, A.; Arrojo, M.; Bernardo, M.; Sáiz, P.A.; Flórez, G.; Torrens, M.; Tirado-Muñoz, J.; Fonseca, F.; et al. Clinical practice guideline on pharmacological and psychological management of adult patients with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder and comorbid substance use. Adicciones 2022, 34, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilfahrt, R.P.; Wilfahrt, L.G.; Matthews Hamburg, A. Atomoxetine reduced binge/purge symptoms in a case of anorexia nervosa binge/purge type. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2021, 44, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, R.; Rukstalis, M.; Jepson, C.; Strasser, A.; Patterson, F.; Lynch, K.; Lerman, C. Effects of atomoxetine on subjective and neurocognitive symptoms of nicotine abstinence. J. Psychopharmacol. 2009, 23, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadde, K.; Yonish, G.; Wagner, H.; Foust, M.; Allison, D. Atomoxetine for weight reduction in obese women: A preliminary randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, 1138–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Rizvi, A.; Srinivas, S.; Jain, S. Spontaneous ejaculation associated with atomoxetine. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2022, 24, 21cr03136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monte, A.A.; Ceschi, A.; Bodmer, M. Safety of non-therapeutic atomoxetine exposures—A national poison data system study. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 28, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovecchio, F.; Kashani, J. Isolated atomoxetine (Strattera) ingestions commonly result in toxicity. J. Emerg. Med. 2006, 31, 267–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashani, J.; Ruha, A. Isolated atomoxetine overdose resulting in seizure. J. Emerg. Med. 2007, 32, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wernicke, J.; Holdridge, K.; Jin, L.; Edison, T.; Zhang, S.; Bangs, M.; Allen, A.; Ball, S.; Dunn, D. Seizure risk in patients with attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder treated with atomoxetine. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2007, 49, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, M. Pediatric atomoxetine ingestions reported to Texas poison control centers, 2003–2005. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 2007, 70, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, V.A.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Anand, E.; Ann Day, K.; Treuer, T.; Upadhyaya, H.P.; Coghill, D.R.; Kryzhanovskaya, L.A.; Savill, N.C. The safety of atomoxetine for the treatment of children and adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A comprehensive review of over a decade of research. CNS Drugs 2016, 30, 603–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennissen, L.; Bakker, M.J.; Banaschewski, T.; Carucci, S.; Coghill, D.; Danckaerts, M.; Dittmann, R.W.; Hollis, C.; Kovshoff, H.; McCarthy, S.; et al. Cardiovascular effects of stimulant and non-stimulant medication for children and adolescents with ADHD: A systematic review and meta-analysis of trials of methylphenidate, amphetamines and atomoxetine. CNS Drugs 2017, 31, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Li, G.F.; Markowitz, J.S. Atomoxetine: A review of its pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenomics relative to drug disposition. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 26, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashova, R.; Silverstone, P.H. Off-label use of atomoxetine in adults: Is it safe? Ment. Illn. J. 2012, 4, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, E.F.; Lim, S.Z.; Tam, W.W.; Ho, C.S.; Zhang, M.W.; McIntyre, R.S.; Ho, R.C. The effect of methylphenidate and atomoxetine on heart rate and systolic blood pressure in young people and adults with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- B.M.C. Medicine. Balancing access to ADHD medication. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, K. Drug Shortage Leads Some to Alternative Therapies. EVMS Pulse. 2022. Available online: https://www.evms.edu/pulse/archive/drugshortageleadssometoalternativetherapies.php (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Cortese, S.; Newcorn, J.H.; Coghill, D. A Practical, Evidence-informed approach to managing stimulant-refractory Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). CNS Drugs 2021, 35, 1035–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StreetRx. About StreetRx—Latest Street Prices for Illicit and Prescription Drugs. Available online: https://streetrx.com/about.php (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Dasgupta, N.; Freifeld, C.; Brownstein, J.S.; Menone, C.M.; Surratt, H.L.; Poppish, L.; Green, J.L.; Lavonas, E.J.; Dart, R.C. Crowdsourcing black market prices for prescription opioids. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hswen, Y.; Zhang, A.; Brownstein, J.S. Leveraging black-market street buprenorphine pricing to increase capacity to treat opioid addiction, 2010–2018. Prev. Med. 2020, 137, 106105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebin, J.A.; Murphy, D.L.; Severtson, S.G.; Bau, G.E.; Dasgupta, N.; Dart, R.C. Scoring the best deal: Quantity discounts and street price variation of diverted oxycodone and oxymorphone. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2018, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).