Abstract

The heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60) is a highly conserved molecular chaperonin belonging to the chaperone system, a complex network that maintains proteostasis and regulates numerous cellular processes beyond protein folding. Initially described as a mitochondrial protein essential for the folding of newly imported polypeptides, Hsp60 is now recognized as a multifunctional molecule. Its expression, localization, and post-translational modifications dynamically influence cell fate and tissue homeostasis. Alterations in Hsp60 quantity, structure, or distribution underlie a heterogeneous group of disorders known as chaperonopathies, which may occur “by defect,” “by excess,” or “by mistake” (also called “by collaborationism”). Genetic Hsp60’s chaperonopathies are associated with rare neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases, whereas acquired forms contribute to widespread conditions, including autoimmune, inflammatory, and malignant pathologies. This review provides a comprehensive overview of Hsp60 biology across human systems, emphasizing its structural plasticity, context-dependent functions, and dual role in health as both a biomarker and a therapeutic target. The emerging paradigm of chaperonotherapy, encompassing positive strategies to restore protective chaperones and negative strategies to inhibit pathogenic ones, highlights the translational potential of targeting Hsp60. Understanding the molecular mechanisms governing its activity will be essential for developing precision medicine approaches aimed at modulating the chaperone system in human disease.

1. Introduction

The Chaperone System (CS) is a complex and dynamic network of molecular chaperones, co-chaperones, cofactors, interactors, and receptors that safeguard protein homeostasis and participate in diverse non-canonical functions, including interactions with the immune system and roles in carcinogenesis [1]. Heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60), one of its major members, must be studied within this context, as neither its physiological nor pathological activities occur in isolation [2].

The CS is evolutionarily ancient, originating in early unicellular organisms and expanding in structural and functional complexity with multicellularity [3]. When components of the CS become quantitatively, structurally, or functionally abnormal, they can cause diseases, namely chaperonopathies, which may be categorized as by defect, by excess, or by mistake (the latter, also called “by collaborationism”) [4]. These discoveries have fostered the development of chaperonotherapy: positive approaches aim to restore deficient chaperones, whereas negative strategies are aimed at selectively counteracting the pathogenic activities of Hsp60 without interfering with its essential physiological functions [5].

Hsp60 exemplifies this duality, being involved in both physiological processes and multiple pathologies. Crucially, the subcellular and extracellular localization of CS components, including Hsp60, strongly influences their roles in health and disease. Therefore, mapping these distributions through immunomorphological techniques has revealed their value as biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy monitoring [6,7]. For instance, aberrant localization of Hsp60 in Hashimoto thyroiditis illustrates how altered distribution can trigger immune responses [8]. Similarly, immunohistochemical studies have shown that Hsp60, typically mitochondrial with a punctate pattern in normal tissues, increases and redistributes in pathological conditions, including inflammation, autoimmunity, and cancer [9].

Collectively, these findings highlight the necessity of considering Hsp60 as an integral component of the CS, whose mobility, ability to form functional complexes, and pathological mislocalization underlie its contributions to disease and therapeutic potential.

To this end, we conducted bibliographic research between January and September 2025 using major scientific databases, including PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. The keywords and Boolean combinations employed (“Hsp60,” “heat shock protein 60,” “chaperone system,” “chaperonopathies,” “inflammation,” “autoimmunity,” “cancer,” “neurodegeneration,” “cardiovascular,” “mitochondrial proteostasis”, etc.) were selected to cover both canonical and non-canonical roles of Hsp60 across biological systems and pathological contexts. Original research articles, reviews, and relevant preclinical and clinical studies published primarily in English were included, without restriction by geographic origin. Priority was given to peer-reviewed papers published in the last two decades, though seminal works of historical relevance were also considered. References were screened for conceptual relevance and methodological rigor, and additional articles were identified by examining the bibliographies of selected publications. Our aim was to write a narrative review providing the most comprehensive overview possible of current knowledge on the role of Hsp60 in the etiopathogenesis of human diseases, with the goal of inspiring and stimulating further research in this field and ultimately improving the diagnosis and treatment of at least some of these conditions.

2. Molecular Properties of the Chaperone Hsp60

Hsp60 is a member of the Group I chaperonins, part of the CS [10]. Group I chaperonins are ATP-dependent molecular chaperones found in bacteria and in eukaryotic organelles of endosymbiotic origin (see below), such as mitochondria and chloroplasts, where they assist protein folding through a barrel-shaped oligomeric structure. Hsp60 plays essential canonical roles in maintaining protein homeostasis under both physiological and stress conditions, and participates in non-canonical processes, including gene regulation, differentiation, inflammation, carcinogenesis, senescence, and apoptosis [11].

Although traditionally considered intracellular (particularly, intramitochondrial), numerous studies have shown that Hsp60 can also be released into the extracellular milieu, thereby influencing neighboring cells and systemic responses [12]. Structurally, human Hsp60 shares high similarity with GroEL—the bacterial homolog of mitochondrial Hsp60, i.e., the prototypical Group I chaperonin, originally characterized in Escherichia coli (E. coli)—forming heptameric rings that assemble into functional tetradecamers with the co-chaperonin Hsp10, driven by ATP-dependent allosteric transitions [13].

However, unlike GroEL, Hsp60 exhibits unique oligomeric dynamics, existing as a mixture of monomers, heptamers, and tetradecamers, with “football”-shaped complexes predominating and lacking the inter-ring negative cooperativity characteristic of GroEL [13,14,15]. Compared to GroEL, human Hsp60 displays a lower intrinsic oligomeric stability and a higher degree of structural plasticity, which is thought to underlie its broader range of context-dependent functions [7,13]. This structural diversity, revealed by crystallography and cryo-EM studies, suggests that distinct oligomeric states of Hsp60 may underlie its context-dependent physiological and pathological functions [15,16,17,18]. Importantly, aberrant oligomerization and stability differences compared to GroEL are linked to pathological conditions, including cancer and neurodegenerative diseases [19,20,21].

Additional complexity arises from post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as acetylation, nitration, nitrosylation, and phosphorylation, which modulate Hsp60 localization, stability, and interactions [22]. These modifications can either support physiological adaptations—for example, S-nitrosylation promotes mitochondrial biogenesis—or drive pathology, as in the case of hyperacetylation-induced senescence and cancer cell death or nitration-associated impairment of insulin secretion and contribution to diabetes and liver injury.

Thus, Hsp60 structural plasticity and PTM-driven regulation not only underpin its multifaceted canonical and non-canonical roles but also highlight its involvement in chaperonopathies and its potential as a target for positive or negative chaperonotherapy [6,23,24,25].

3. General Pathology

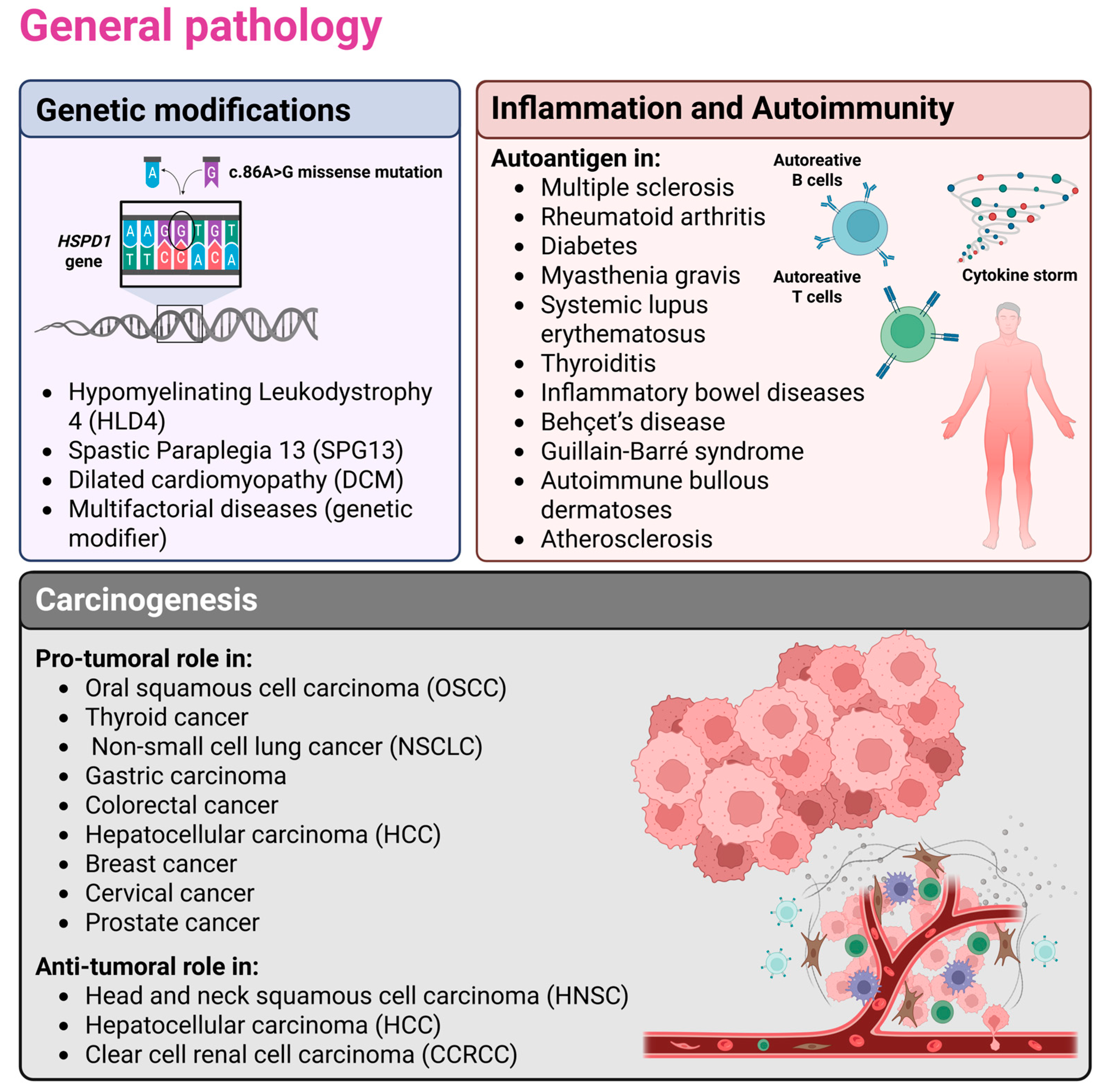

Hsp60’s dual role in tissue homeostasis and pathophysiology clearly emerges in general pathology as described below and summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The figure illustrates the involvement of Hsp60 in the etiopathogenesis of human diseases. Specifically, genetic alterations, inflammation/autoimmunity, and carcinogenesis were chosen as overarching themes under which the main aspects of general pathology—i.e., the study of disease etiopathogenesis—are organized. Selected examples that are described in greater detail in the main text are also shown. In particular, mutations in the HSPD1 gene have been linked to diseases affecting the nervous system (Hypomyelinating Leukodystrophy 4 and Spastic Paraplegia 13) and the cardiovascular system (Dilated Cardiomyopathy). In the context of autoimmune and inflammatory conditions, Hsp60 can act both as an autoantigen, promoting autoantibody production and autoreactivity, and as a chaperokine, triggering inflammation when surface-exposed or secreted. Finally, in carcinogenesis, Hsp60 may function either as a pro-tumorigenic or an anti-tumorigenic factor, depending on the cellular context. Created in BioRender (https://BioRender.com/cnq6d32; accessed on 27 November 2025).

3.1. Genetic Modifications

Human Hsp60 is one of the most ancient and conserved proteins of the CS, ubiquitously present in bacteria, mitochondria, and chloroplasts, thus supporting the endosymbiotic theory [16,26]. According to the endosymbiotic theory, mitochondria originated from ancestral free-living bacteria that established a symbiotic relationship with early eukaryotic cells, explaining the bacterial ancestry of proteins such as Hsp60 [26]. It was initially identified as GroEL, essential in bacteriophage assembly, and later recognized as a key player in protein folding mediated by ATP and GroES [26,27,28]. Its essential role is confirmed by the lethal effects of inactivating orthologous genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Drosophila melanogaster, and mice, where complete loss of the protein leads to early embryonic death, whereas haploinsufficiency is associated with late-onset progressive motor deficits [29,30,31].

The conservation between GroEL and human Hsp60 is extremely high at both sequence and three-dimensional structural levels, particularly in residues involved in nucleotide binding, co-chaperone interaction, and substrate recognition, which explains why GroEL was used as a model to investigate Hsp60 function [7,21]. Encoded by the nuclear gene HSPD1, Hsp60 performs canonical functions in maintaining mitochondrial proteostasis by assisting the folding of nearly half of the matrix proteins, including ribosomal subunits, tRNA ligases, respiratory chain components, and quality-control proteins such as HSPA9 and SOD2 (i.e., the mitochondrial superoxide dismutase 2) [32,33]. In addition, non-canonical localizations have been described in the cytosol, plasma membrane, biological fluids, and extracellular vesicles (EVs), where Hsp60 exerts “moonlighting” activities, such as activating antitumour immune responses or acting as a danger signal in cardiomyocyte-derived exosomes [34,35].

Quantitative, structural, or functional abnormalities of Hsp60 can result in chaperonopathies, a heterogeneous group of genetic or acquired diseases. The former, caused by mutations in genes encoding for CS members, are relatively rare and typically manifest early. Instead, the latter are more frequent, especially in adults, and are associated with cancer, autoimmune, inflammatory, and degenerative disorders [1,4,5,6,36]. In the case of Hsp60, acquired forms prevail, but genetic variants of HSPD1 are now recognized as more common than previously thought, including missense, frameshift, nonsense, and UTR mutations, many of which are of uncertain clinical significance according to American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics/Association for Molecular Pathology guidelines [37]. Some well-conserved missense mutations have been linked to rare neurochaperonopathies. These include the hypomyelinating leukodystrophy 4 (HLD4), an autosomal recessive condition caused by the c.86A>G (p.Asp29Gly) missense mutation, characterized by early onset with hypotonia, developmental delay, spasticity, seizures, growth arrest, severe hypomyelination on MRI, and premature death [38,39]. More recently, heterozygous de novo variants, such as p.Leu47Val, have been associated with dominant, milder forms [40,41].

Another related disease, hereditary spastic paraplegia SPG13, belonging to the pure subtype, has been linked to the Hsp60’s missense mutations p.Val98Ile and p.Gln461Glu. Clinical features include progressive lower limb spasticity and weakness, highly variable penetrance, with onset ranging from childhood to late adulthood [42,43,44]. In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that these variants cannot replace GroEL in E. coli, impairing cell survival under heat stress and compromising protein refolding activity, with reduced ATPase function, oligomer destabilization, and nucleotide-dependent dissociation into monomers, thereby severely affecting mitochondrial function and supporting the hypothesis of a dysfunctional Hsp60/Hsp10 complex [45,46,47,48]. Eukaryotic models confirmed mitochondrial morphological and functional alterations, with a decreased membrane potential and impaired biogenesis, highlighting the centrality of mitochondrial dysfunction in pathogenesis [49].

Beyond the nervous system, HSPD1 missense mutations have been associated with cardiovascular disorders, such as dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). The p.Thr320Ala variant was found in a Japanese family with arrhythmias and sudden cardiac deaths at a young age [50]. Affected individuals displayed ventricular dilation, systolic dysfunction, and a clinical course often requiring transplantation, consistent with the heterogeneous genetic basis of DCM. HEK293 cells expressing the Hsp60 carrying the p.Thr320Ala missense mutation showed elevated autophagy markers, increased Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), impaired mitochondrial dynamics, and reduced respiratory complex activity. In addition, in vivo, a zebrafish model with an analogous mutation presented dilated ventricles, thin walls, sarcomere rupture, decreased exercise tolerance, and shortened lifespan, all partially rescued by ROS and autophagy inhibition.

Recent evidence indicates that HSPD1 variants can function as genetic modifiers in multifactorial diseases, modulating the phenotypic expression of mutations in other genes. This has been observed in conditions such as multiple mitochondrial enzyme deficiency, ethylmalonic aciduria, and sudden infant death syndrome, for which HSPD1 variants are not the direct cause [51,52,53,54,55].

In summary, Hsp60 genetic chaperonopathies arise from HSPD1 mutations that disrupt protein structure and function, primarily affecting the nervous and cardiovascular systems due to their dependence on mitochondrial homeostasis. While numerous potentially pathogenic variants exist, only a small fraction has been characterized, and for those already associated with disease (e.g., SPG13, HLD4, DCM), the precise molecular mechanisms remain incompletely understood. Nevertheless, converging evidence supports mitochondrial dysfunction as the unifying pathogenic mechanism, underscoring the need for further studies to elucidate molecular interactions, refine diagnostics, and develop targeted chaperonotherapy strategies.

3.2. Inflammation and Autoimmunity

Hsp60 may play central etiopathogenic roles in inflammation, autoimmunity, and virus-induced diseases when it is quantitatively or qualitatively altered or misplaced outside its native localization, i.e., mitochondria, where it normally ensures protein homeostasis and mitochondrial function [56].

Autoimmune diseases are complex disorders affecting approximately 5% of the global population, predominantly women, and result from an interplay of genetic predisposition and environmental triggers such as infections, lifestyle, and stress [57]. One of the main mechanisms linking infections with autoimmunity is the molecular mimicry phenomenon, whereby foreign antigens share sequence or structural epitopes with host proteins, leading to cross-reactive antibodies or autoreactive T and B cells that compromise self-tolerance and perpetuate chronic inflammation [58]. Prolonged infection-driven inflammation, mediated by sustained release of cytokines such as IFN, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IL-17, and TNF-α, damages tissues and fosters autoantibody production, reinforcing the overlap between autoimmunity and chronic inflammatory diseases [56,59].

Within this context, Hsp60 emerges as a prototypical “chaperonopathy by mistake” (or “by collaborationism”), acting not only as an essential mitochondrial chaperonin but also as an autoantigen, a pro-inflammatory mediator, and a facilitator of tumourigenesis [4,36]. Extramitochondrial Hsp60 exerts immune-regulatory and inflammatory functions, linking innate and adaptive responses, with both protective and pathogenic outcomes [12,60,61,62]. Anti-Hsp60 autoantibodies have been reported in multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, myasthenia gravis, systemic lupus erythematosus, thyroiditis, inflammatory bowel disease, and Behçet’s disease [63]. These antibodies can be produced either in response to endogenous Hsp60 released upon tissue damage, or due to exposure to microbial homologs, such as those from E. coli, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), and Chlamydia trachomatis (C. trachomatis), through mechanisms of molecular mimicry [64,65,66]. Importantly, Hsp60 autoreactivity does not invariably imply pathology. In some contexts, such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Hsp60-reactive T cells produce anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10) that favor remission, whereas in others they release pro-inflammatory cytokines promoting disease [8,67,68].

The recent COVID-19 pandemic reinforced the relevance of mimicry, with overlapping antigenic epitopes between SARS-CoV-2 proteins and human Hsp60 potentially underpinning autoimmune disorders like Guillain-Barré syndrome and autoimmune bullous dermatoses [69,70,71,72].

Beyond autoimmunity, Hsp60 acts as a “chaperokine,” driving inflammation when surface-exposed or secreted. It promotes dendritic cell maturation, cytotoxic T-cell activation, macrophage-dependent cytokine release via CD14 and TLR4, nitric oxide production, and synergistic amplification of TLR signaling with bacterial LPS [6]. Chronic exposure, however, can induce tolerization and monocyte deactivation [73].

Furthermore, Hsp60 also shapes adaptive immunity. Via TLR2 signaling, it regulates T-cell transcriptional programs, downregulating pro-inflammatory mediators (e.g., NFκB, NFAT, T-bet), while upregulating SOCS3 and GATA-3, thus shifting responses toward anti-inflammatory Th2 phenotypes and promoting Treg expansion [74,75,76]. Similarly, B-cells respond through TLR4-MyD88 signaling, proliferating and secreting IL-6 and IL-10, enhancing antigen presentation, and promoting autoantibodies production [77,78]. These immune-modulatory activities link Hsp60 to the development of atherosclerosis, in which the endothelial stress induces surface Hsp60 expression, triggering autoreactive and cross-reactive T-cell responses. This is supported by evidence of Hsp60-specific T cells within atherosclerotic plaques and by the colocalization of microbial and human Hsp60 in vascular lesions [79].

Finally, viral infections further exploit Hsp60 as a pro-virulence factor. In hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, Hsp60 interacts with viral polymerase, promoting its activation and replication, while Hsp60’s antisense-mediated knockdown impairs nucleocapsid maturation [80]. Multichaperone complexes, including Hsp60, Hsp70, and Hsp90, also facilitate HBV replication [81]. On the other hand, it has been observed that Hsp60 can paradoxically exert antiviral effects by binding HBV X protein and promoting apoptosis of infected cells [82]. Elevated soluble Hsp60 in HBV patients enhances IL-10 secretion by Treg cells via TLR2 and TLR4 pathways, contributing to immunosuppression and viral persistence, a mechanism reversed by entecavir therapy [83].

From a mechanistic perspective, many of these inflammatory and autoimmune effects can be traced back to changes in Hsp60 localization and PTMs. When released into the cytosol, plasma membrane, or extracellular milieu, Hsp60 acquires chaperokine-like properties, engaging TLR2 and TLR4 signaling pathways and reshaping both innate and adaptive immune responses [77,78]. Moreover, PTMs such as nitration, acetylation, or S-nitrosylation have been shown to influence Hsp60 stability, immunogenicity, and receptor interactions, thereby modulating whether immune responses are pro-inflammatory or tolerogenic [22]. Thus, the pathogenic or protective role of Hsp60 in autoimmunity is not solely dependent on its abundance, but critically on its molecular state and cellular compartmentalization.

3.3. Carcinogenesis

Hsp60 aberrant expression, mislocalization, or PTMs have been detected in many human cancers, where the chaperonin can act either as a tumour promoter or, in certain contexts, as a tumour suppressor [22]. Hsp60 interacts with major oncogenic pathways, including phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and Wingless/β-catenin (Wnt/β-catenin), thereby promoting cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and metastasization, while also protecting malignant cells from proteotoxic and oxidative stress. This condition is referred to as a “chaperonopathy by mistake” (or “by collaborationism”) in which the chaperone erroneously supports cancer rather than organismal homeostasis [84]. Through direct interactions with p53 (the tumor suppressor protein that regulates cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, and apoptosis), survivin, and IKK, Hsp60 inhibits apoptosis, stabilizes anti-apoptotic complexes, reduces ROS, and sustains Nuclear Factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling, thus contributing to tumour cell survival and resistance to therapy, while extracellular Hsp60 engages TLR4 to promote angiogenesis, invasion, and immune evasion [85,86,87,88].

Importantly, Hsp60 also modulates the immune system during carcinogenesis. Sometimes it acts as a danger signal that triggers anti-tumour responses, while other times it facilitates immune tolerance and tumour escape, a dual role that complicates its therapeutic targeting [89,90,91,92]. Clinically, Hsp60 abnormal levels, distribution, or PTMs, both in tissues and circulating EVs, are emerging as promising diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers, and negative chaperonotherapy, based on inhibitors or gene silencing, is being developed to counteract its pro-oncogenic functions, although compensatory pathways within the CS pose challenges [24,60,93].

In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, loss of Hsp60 expression during disease progression correlates with poor survival, suggesting a tumour-suppressive role, whereas in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) Hsp60 is upregulated and cooperates with survivin to stabilize cancer cell survival, with Hsp60/survivin expression predicting poor prognosis and representing a therapeutic target for inhibitor-based therapies or even future vaccine approaches [94,95].

In thyroid cancer, Hsp60 is upregulated in multiple histotypes, including papillary, follicular, medullary, and anaplastic carcinoma, where PTMs such as acetylation, nitration, or ubiquitination alter its structure, impair mitochondrial function, and drive tumourigenesis, while its immunohistochemical detection offers valuable information for diagnosis and tumour staging [96,97,98].

In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), both Hsp10 and Hsp60 are co-overexpressed, cooperating to stabilize procaspase-3 complexes, suppress apoptosis, and correlate with poor prognosis, while also serving as candidate biomarkers detectable in tissue and plasma [99,100,101,102].

Gastric carcinoma also shows a staging-dependent progressive increase in Hsp60 levels, from dysplasia to invasive cancer, indicating its role in sustaining proliferation and metabolic stress responses, again exemplifying chaperonopathy by mistake and justifying the exploration of Hsp60 inhibitors as anticancer strategies [103,104].

In colorectal cancer, Hsp60 is upregulated in epithelial and stromal compartments, localizes in the cytosol and plasma membrane, activates immune pathways through TLR4, and is released in EVs that support metastasis, thus serving as both a therapeutic target for chaperonotherapy and a biomarker for early diagnosis and post-surgical monitoring [105,106,107,108].

In hepatocellular carcinoma, Hsp60 is increased in inflammatory and neoplastic tissues, correlating with mitochondrial biogenesis and ERK signalin. Some data indicate anti-metastatic effects of Hsp60 overexpression, while silencing experiments confirm its essential role in sustaining proliferation and survivin stability in tumour cells, highlighting its context-dependent duality [109,110,111,112].

Conversely, in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (CCRCC), Hsp60 expression is reduced, and its downregulation drives tumour-promoting metabolic reprogramming via MEK/ERK and c-Myc activation, increased glutamine metabolism, and NRF2-mediated antioxidant responses, suggesting that Hsp60 may function as a tumour suppressor in this context [113,114].

In breast cancer, Hsp60 overexpression is strongly associated with Her2-positive tumours and MAPK-mediated signaling, sustaining tumour growth, invasion, and resistance to apoptosis. Moreover, its release in EVs contributes to lung metastasis formation, making plasma EV-Hsp60 levels minimally invasive biomarkers for monitoring disease progression and therapeutic response [115,116].

In cervical cancer, Hsp60 expression is elevated across precancerous and invasive stages, where it supports tumour progression and cooperates with viral and microbial oncogenesis. In fact, human papillomavirus oncogenes E6/E7 inhibit p53 and Rb, while persistent C. trachomatis infection and immune responses against chlamydial Hsp60 (C-Hsp60) exacerbate inflammation and oncogenic signaling through NF-κB and cytokine release [117,118,119,120].

In prostate cancer, increased Hsp60 levels are evident from early stages such as prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), where the chaperonin prevents protein aggregation, supports inflammation, and interacts with anti-apoptotic molecules, facilitating progression towards invasive adenocarcinoma, highlighting its value for both diagnostic and therapeutic applications [121,122].

Taken together, these findings emphasize the multifaceted and context-dependent roles of Hsp60 in human carcinogenesis, acting as either a tumour facilitator or suppressor depending on cancer type, molecular milieu, and immune interactions. Consequently, Hsp60 serves simultaneously as a valuable biomarker, a prognostic beacon, and a therapeutic target, with the refinement of chaperonotherapy—particularly negative strategies—in combination with conventional anticancer drugs representing a promising frontier in precision oncology.

Overall, from a mechanistic point of view, the functional duality of Hsp60 in cancer can likewise be interpreted through its structural plasticity and mislocalization. Distinct oligomeric states and PTMs influence its interactions with apoptotic regulators, such as p53 and survivin, as well as its capacity to stabilize oncogenic signaling complexes [66]. Cytosolic and extracellular Hsp60, often associated with EVs, further contributes to tumor–immune crosstalk and microenvironment remodeling [108]. These observations support the concept that Hsp60-driven carcinogenesis represents a chaperonopathy “by mistake” [6], in which altered molecular states of the chaperonin, rather than its canonical folding activity, dictate pathological outcomes.

4. Systemic Pathologies

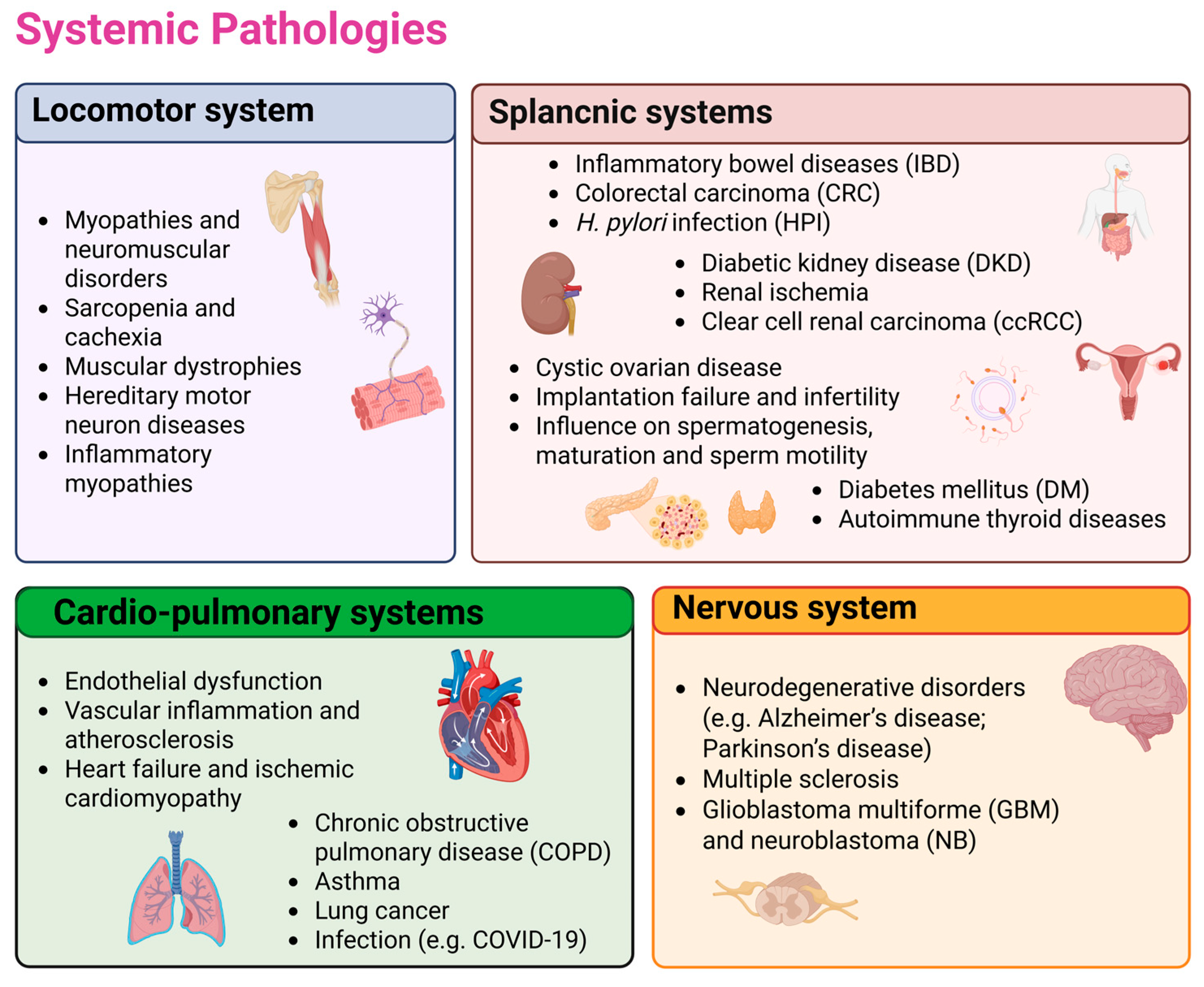

The following paragraphs will illustrate the main systemic disorders involving Hsp60, summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The figure summarizes the main systemic diseases involving Hsp60. Disorders of the musculoskeletal, cardiopulmonary, splanchnic, and nervous systems correspond to the four sections into which the so-called systematic human pathology is organized in the text, with selected literature-based examples highlighting Hsp60 involvement. These include musculoskeletal disorders such as myopathies, neuromuscular diseases, sarcopenia, and muscular dystrophies; splanchnic disorders including gastrointestinal inflammation, colorectal cancer, H. pylori infection, renal and reproductive disorders, diabetes, and thyroid autoimmunity; cardiopulmonary diseases such as endothelial dysfunction, vascular inflammation, atherosclerosis, heart failure, COPD, asthma, lung cancer, and infections; and nervous system disorders including neurodegeneration, multiple sclerosis, and cancer. Further details for each of these conditions, along with the corresponding references, are provided in the main text. Created in BioRender (https://BioRender.com/cnq6d32; accessed on 27 November 2025).

4.1. Alteration of Locomotor System

Increasing evidence has demonstrated that Hsp60, beyond its canonical mitochondrial roles in protein folding and quality control, plays a key role in the maintenance of musculoskeletal tissue homeostasis and in the pathogenesis of both cartilage and skeletal muscle diseases, acting either protectively or pathogenically depending on its expression levels, localization, and interactions with immune and stress-response pathways [123,124].

In cartilage, Hsp60 contributes to tissue integrity under physiological conditions by assisting chondrocyte survival and metabolic balance. For instance, in both osteoarthritis (OA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Hsp60 showed protective effects. Particularly, in OA, Hsp60 showed a chondroprotective effect through the regulation of SOX9 ubiquitination in affected joints [125]. In RA, Hsp60 protects against experimental arthritis [126]. This protective effect has been attributed to the ability of Hsp60-derived peptides to induce regulatory immune responses, including the expansion of IL-10–producing T cells and the modulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine production [67,68].

In skeletal muscle, where mitochondrial function is fundamental to provide energy supply and ensure contractility, Hsp60 is also critically involved in physiology and pathology. Basal Hsp60 expression ensures mitochondrial proteostasis in muscle fibers, particularly in oxidative type I fibers, supporting endurance and resistance to stress, while exercise and training upregulate Hsp60, enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis, antioxidant defenses, and metabolic efficiency, thus contributing to muscle adaptation [127]. However, imbalances in Hsp60 expression are linked to diverse myopathies and neuromuscular disorders. For instance, reduced Hsp60 levels impair mitochondrial respiration, increase ROS, and promote apoptosis, favoring degenerative conditions such as sarcopenia and cachexia, while abnormal accumulation or extracellular release can trigger inflammatory responses, exacerbating muscular dystrophies [128].

Moreover, Hsp60 mutations in the nuclear HSPD1 gene underlie hereditary motor neuron diseases such as spastic paraplegia SPG13 and hypomyelinating leukodystrophy HLD4, highlighting the dependence of muscle and neuromuscular systems on proper chaperonin function [41,43]. Inflammatory myopathies, including dermatomyositis, also show enhanced Hsp60 expression in infiltrating immune cells and damaged fibers, where it acts as a danger-associated molecular pattern (DAMP), activating TLR-mediated signaling and perpetuating autoimmune injury [129]. Nonetheless, as observed in cartilage, Hsp60 can play protective roles in muscle by promoting mitochondrial repair and counteracting stress-induced apoptosis, underscoring its ambivalent involvement in health and disease [130].

Taken together, evidence from cartilage and muscle studies depicts Hsp60 as a molecular switch at the crossroads of proteostasis, immunity, and metabolism. Its balanced activity preserves tissue homeostasis, while its dysregulation drives degenerative, inflammatory, and autoimmune processes. These properties make Hsp60 both a promising biomarker for musculoskeletal pathologies and a target for “chaperonotherapy” which may involve negative strategies to inhibit its pathogenic excesses or positive strategies to harness its cytoprotective potential, depending on the disease context.

4.2. Pathologies of the Cardio-Pulmonary Systems

Hsp60 plays pivotal roles in both the Cardiovascular System (CVS) [131] and the Respiratory System (RS) [132], where its canonical function of maintaining mitochondrial proteostasis overlaps with non-canonical activities in inflammation, immunity, and carcinogenesis.

In the CVS, Hsp60 is essential for cardiac and vascular homeostasis, but, when abnormally expressed or misplaced, it contributes to a spectrum of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Under physiological conditions, Hsp60 supports cardiomyocyte survival and mitochondrial integrity, and its controlled release into circulation serves as a signal of cellular stress [133]. However, excessive extracellular, circulating Hsp60 acts as a DAMP, binding receptors such as TLR4 and CD14, activating NF-κB signaling, and triggering cytokine release, thereby promoting vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis [90,134].

Elevated Hsp60 serum levels are associated with endothelial dysfunction, progression of atheromatous plaques, and increased risk of acute coronary syndromes, while anti-Hsp60 autoantibodies have been identified in patients with hypertension, diabetes, and atherosclerosis, further confirming it as both a biomarker and a pathogenic mediator [135,136,137]. Notably, mitochondrial dysfunction linked to altered Hsp60 expression has been described in heart failure and ischemic cardiomyopathy, conditions in which decreased mitochondrial Hsp60 impairs energy metabolism and enhances apoptosis, whereas abnormal accumulation in the cytosol or extracellular space exacerbates inflammatory cascades and tissue remodeling [35,136,138]. In this context, it is worth noting that Hsp60 has also been proposed as a candidate gene influencing cardiac performance under heat stress in experimental models, supporting a broader role for this chaperonin in cardiac stress adaptation mechanisms [139].

In parallel, the role of Hsp60 in the RS has drawn increasing attention, due to its involvement in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, lung cancer, infections, and COVID-19. In COPD, Hsp60 displays a Janus-like role: downregulated in preneoplastic bronchial lesions of smokers yet overexpressed in bronchial mucosa during inflammation, where it promotes neutrophil recruitment and survival through oxidative stress-induced NF-κB activation and extracellular release [140,141]. This dual behavior highlights its pathogenic contribution to both chronic inflammation and carcinogenesis. In asthma, anti-Hsp60 autoantibodies have been detected and linked to disease severity, while increased Hsp60 expression in alveolar macrophages suggests a regulatory role in immune responses, likely influenced by gene-environment interactions such as the asthma-associated locus GSDMB on chromosome 17q21, which upregulates Hsp60 and promotes airway remodeling [142,143]. Therapeutic interventions such as bronchial thermoplasty reduce Hsp60 levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, mitigating airway remodeling, whereas experimental peptides derived from Hsp60, such as SJMHE1, suppress airway inflammation and shift T-cell responses toward regulatory phenotypes in murine asthma models, suggesting the therapeutic potential of chaperonotherapy [144,145].

Respiratory infectious diseases further exemplify Hsp60’s multifaceted role. In Chlamydia pneumoniae infection, chlamydial Hsp60 (cHsp60) induces immune responses that exacerbate COPD and asthma, with seropositivity correlating with impaired lung function, while in viral infections such as PRRSV and influenza, Hsp60 participates in antiviral signaling or, conversely, is hijacked to facilitate viral replication [146].

The COVID-19 pandemic has further emphasized the relevance of Hsp60. Increased tissue and plasma levels correlate with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and systemic inflammation, while PTMs of Hsp60 and Hsp90 in endothelial cells of COVID-19-affected subjects point to roles in thrombogenesis and immunopathology, possibly via molecular mimicry with viral proteins [147]. Clinical studies on Hsp60-derived peptides, such as CIGB-258, in severely ill COVID-19 patients demonstrated reductions in pro-inflammatory cytokines, expansion of regulatory T cells, and clinical recovery without adverse effects, highlighting the feasibility of chaperonotherapy in viral hyperinflammation [148].

Collectively, evidence from cardiovascular and respiratory research illustrates the Janus-like nature of Hsp60: it is cytoprotective under homeostatic conditions yet pathogenic when dysregulated, acting as a molecular hub between mitochondrial dysfunction, immunity, and inflammation. This duality makes Hsp60 a promising biomarker and therapeutic target to treat CVDs, COPD, asthma, lung cancer, and viral infections, suggesting the need for precision chaperonotherapy—either negative, to inhibit its pathogenic roles, or positive, to restore its protective functions—tailored to the disease context.

4.3. Disorders of Other Splanchnic Systems

Hsp60 exerts fundamental yet ambivalent roles in the Digestive System (DS), Urogenital Apparatus (UA), and Neuroendocrine System (NES), where its canonical mitochondrial functions overlap with pathogenic activities involving inflammation, immunity, autoimmunity, and carcinogenesis.

In the DS, Hsp60 could participate in the homeostasis of the triad Microbiota–Immune System–CS. Moreover, its abnormal expression might contribute to inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), colorectal carcinoma (CRC), and H. pylori infection (HPI). In particular, in IBD, Hsp60 is overexpressed in intestinal mucosa and secreted via EVs, where it promotes pro-inflammatory cytokine release (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) and molecular mimicry with microbial GroEL proteins, thereby amplifying autoimmunity and chronic inflammation [149,150,151,152]. In CRC, Hsp60 upregulation in epithelial and stromal cells supports tumour growth, angiogenesis, and immune evasion, whereas its exosomal release correlates with metastasis and patient prognosis, suggesting its potential as a biomarker and therapeutic target [106,107,108]. In HPI, Hsp60, including that released by EVs, plays a multifaceted and indispensable role in the survival and pathogenicity of vehiculated [66].

In the UA, Hsp60 plays multifaceted roles in renal, female, and male reproductive health. In the kidney, its expression increases under oxidative, metabolic, or thermal stress, supporting mitochondrial stability and protein folding, but its dysregulation is implicated in diabetic kidney disease, renal ischemia, and CCRCC, where both under- and overexpression correlate with disease stage and prognosis [153,154,155]. In the female reproductive system, Hsp60 regulates folliculogenesis, luteal function, and uterine receptivity, while its aberrant expression is linked to cystic ovarian disease, implantation failure, and infertility [156,157,158,159]. Similarly, in the male reproductive system, Hsp60 is essential for spermatogenesis, sperm maturation, and motility, yet its misregulation induces apoptosis, germ-cell loss, or abnormal mitochondrial sheath organization, contributing to infertility. Testosterone-mediated control of Hsp60 expression further illustrates its central role in male reproductive physiology [156,160,161]. Molecular mimicry between human and chlamydial Hsp60 exacerbates autoimmunity in the genital tract, providing a mechanistic explanation for Chlamydia-induced tubal and male infertility [162,163,164,165,166,167,168]. In prostate cancer, Hsp60 overexpression correlates with Gleason score, androgen resistance, and poor survival, while its functional interactions with mitochondrial ClpP and IL-8 pathways highlight novel therapeutic avenues for negative chaperonotherapy [121,122,169,170].

Regarding the NES, in adrenal tumours associated with Cushing’s syndrome, Hsp60 accumulation correlates with apoptotic signaling, though its etiopathogenic role remains unclear [171]. In diabetes mellitus (DM), Hsp60 downregulation in hypothalamic neurons promotes insulin resistance and mitochondrial dysfunction, while Hsp60 PTMs in pancreatic β-cells under hyperglycemia trigger apoptosis and impaired insulin production, linking the chaperonin to both T1DM and T2DM pathogenesis [172]. In autoimmune thyroid diseases, including Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Hsp60 functions as an autoantigen, cross-reacting with thyroglobulin and thyroid peroxidase, activating dendritic cells via TLR2/3, and sustaining NF-κB-driven inflammation, thereby contributing to thyroid autoimmunity [8].

Collectively, evidence from these three systems highlights the pathogenic role of Hsp60 when dysregulated or mislocalized. Its involvement in a number of disorders underscores its potential as both a biomarker and a therapeutic target, but further investigations are needed.

4.4. Involvement in Diseases of the Nervous System

Hsp60 plays essential roles in the formation, maintenance, and pathology of the nervous system (NS) from embryogenesis through adulthood. Beyond its canonical chaperoning functions, Hsp60 also exhibits immunomodulatory, pro- and anti-apoptotic properties that depend on its intra- or extra-mitochondrial localization [11]. During neural development, Hsp60 contributes to neuroectodermal differentiation and neural tube formation, being expressed in gametes and embryonic tissues and indispensable for embryonic survival, as evidenced by the embryonic lethality of Hsp60-knockout mice [30,173]. Moreover, its deficiency particularly affects neuronal and glial lineages, highlighting its critical role in NS morphogenesis [174].

Alterations in Hsp60 are linked to various neurodegenerative disorders (NDDs), which are broadly characterized by impaired proteostasis, protein misfolding, and aggregation [175]. Neurons, due to their complex morphology and high metabolic demands, are particularly vulnerable to chaperone dysfunctions, resulting in cytoskeletal disorganization, synaptic impairment, and mitochondrial dysfunction [175]. Among NDDs, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has been extensively studied in relation to Hsp60. The chaperonin interacts with amyloid beta oligomers (Aβo) and Tau, modulating their aggregation and toxicity [176,177]. Hsp60 may exhibit dual roles—protective within mitochondria by maintaining respiratory chain integrity [178], yet potentially pathogenic when mislocalized to the cytosol or extracellular space, where it can sustain chronic neuroinflammation through interactions with Toll-like receptors (TLR2/4) and microglial activation [179,180]. Elevated Hsp60 levels in lymphocytes of AD patients suggest its value as a biomarker for early diagnosis [181].

Hsp60 is also implicated in other disorders. For instance, in Parkinson’s disease, Hsp60 co-localizes with α-synuclein aggregates in Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites, contributing to mitochondrial stress and inflammatory signaling [182,183]. The chaperone’s extracellular release by damaged dopaminergic neurons may activate microglia via TLR4, perpetuating neuroinflammation [183]. In prion diseases such as Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, Hsp60 forms complexes with PrPC and the 14-3-3 protein, potentially influencing prion aggregation and serving as a diagnostic marker [184,185]. In multiple sclerosis, Hsp60 acts as an autoantigen recognized by T and B lymphocytes. The presence of anti-Hsp60 antibodies and its elevated expression in demyelinated plaques suggest the chaperonin involvement in autoimmune inflammation [186,187,188].

Finally, Hsp60 contributes to tumourigenesis in the NS, being upregulated in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) and neuroblastoma (NB), where it supports proliferation, inhibits apoptosis, and enhances resistance to therapy [189,190,191]. Its extracellular signaling through TLR4 and regulation via miRNAs and vesicle secretion make it a promising biomarker and therapeutic target for “chaperonotherapy” [23,192].

In conclusion, Hsp60 is a multifunctional chaperonin essential to neural development and homeostasis, but also deeply implicated in neurodegeneration, neuroinflammation, and tumourigenesis. Understanding its compartment-specific roles and regulatory mechanisms may enable its translation into diagnostic and therapeutic applications across a spectrum of NS diseases.

5. Conclusions

Hsp60 emerges as a pivotal molecule at the crossroads of proteostasis, immunity, and cell fate regulation. Its canonical chaperoning function within mitochondria ensures protein quality control and cellular survival, while its non-canonical localizations and interactions extend its influence across virtually all biological systems. The evidence synthesized in this review illustrates that Hsp60’s dual nature—protective in physiological settings yet pathogenic when dysregulated—underpins a wide spectrum of human diseases, from neurodegenerative and cardiovascular disorders to cancer and autoimmunity.

This multifunctionality, coupled with its evolutionary conservation and complex regulation through PTMs, confers on the Hsp60 both diagnostic and therapeutic potential. Hsp60 aberrant expression, mislocalization, or mutation can trigger chaperonopathies “by defect”, “by excess”, or “by mistake,” each reflecting distinct pathophysiological mechanisms yet converging on mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired cellular homeostasis. Such versatility also explains why Hsp60 can act as a tumour promoter in certain contexts and as a tumour suppressor in others, or as both a pro-inflammatory mediator and an immunomodulatory regulator depending on its compartmental distribution.

Advances in molecular biology, immunopathology, and translational medicine have highlighted Hsp60 as a promising biomarker for early detection, prognosis, and therapy monitoring in several diseases. Furthermore, the conceptual framework of chaperonotherapy, encompassing positive and negative strategies to modulate Hsp60 activity, offers a rational basis for innovative treatments. Positive approaches aim to restore or potentiate its protective functions in degenerative or metabolic conditions, whereas negative interventions seek to inhibit its pathogenic roles in cancer, inflammation, or infection.

Future research should aim to clarify the molecular determinants that dictate Hsp60’s context-dependent behavior, its interactions within the broader CS, and the mechanisms governing its trafficking between cellular compartments. A deeper understanding of these dynamics will be essential to translate current knowledge into precision medicine strategies that harness or restrain Hsp60 activity in a disease-specific manner. Ultimately, decoding the complex biology of Hsp60 will not only enhance our grasp of protein homeostasis and cellular stress responses but may also pave the way for novel diagnostic and therapeutic frontiers across diverse human pathologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I.G. and F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D., M.I.G., G.V., A.M.V.; writing—review and editing, G.D., M.I.G., G.V., A.M.V. and F.C.; figures preparation, G.D., A.M.V.; supervision, F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| CCRCC | Clear cell renal cell carcinoma |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CRC | Colorectal carcinoma |

| CS | Chaperone System |

| CVDs | Cardiovascular diseases |

| CVS | Cardiovascular system |

| DCM | Dilated cardiomyopathy |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| DS | Digestive system |

| EVs | Extracellular Vesicles |

| GBM | Glioblastoma multiforme |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HLD4 | Hypomyelinating leukodystrophy 4 |

| HPI | Helicobacter pylori infection |

| Hsp60 | Heat shock protein 60 |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel diseases |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| NB | Neuroblastoma |

| NDDs | Neurodegenerative disorders |

| NES | Neuroendocrine system |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa B |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| OSCC | Oral squamous cell carcinoma |

| PTMs | post-translational modifications |

| RA | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RS | Respiratory system |

| UA | Urogenital apparatus |

References

- Macario, A.J.L.; Conway de Macario, E. Sick chaperones, cellular stress, and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 1489–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K.; Shin, Y.; Han, S.; Ha, J.; Tiwari, P.K.; Kim, S.S.; Kang, I.L. Molecular Chaperonin HSP60: Current Understanding and Future Prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macario, A.J.L.; Conway de Macario, E. The archaeal molecular chaperone machine: Peculiarities and paradoxes. Genetics 1999, 152, 1277–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macario, A.J.L.; Conway de Macario, E. Chaperonopathies by defect, excess, or mistake. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1113, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macario, A.J.L.; Conway de Macario, E. Chaperonopathies and chaperonotherapy. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 3681–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappello, F.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Palumbo Piccionello, A.; Campanella, C.; Pace, A.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L. Hsp60 chaperonopathies and chaperonotherapy: Targets and agents. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2014, 18, 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilasi, S.; Carrotta, R.; Mangione, M.R.; Campanella, C.; Librizzi, F.; Randazzo, L.; Martorana, V.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Ortore, M.G.; Vilasi, A.; et al. Human Hsp60 with its mitochondrial import signal occurs in solution as heptamers and tetradecamers remarkably stable over a wide range of concentrations. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino Gammazza, A.; Rizzo, M.; Citarrella, R.; Rappa, F.; Campanella, C.; Bucchieri, F.; Patti, A.; Nikolic, D.; Cabibi, D.; Amico, G.; et al. Elevated blood Hsp60, its structural similarities and cross-reactivity with thyroid molecules, and its presence on the plasma membrane of oncocytes point to the chaperonin as an immunopathogenic factor in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Cell Stress. Chaperones 2014, 19, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Cappello, F.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L.; Rappa, F. Immunohistochemistry of human Hsp60 in health and disease: Recent advances in immunomorphology and methods for assessing the chaperonin in extracellular vesicles. Methods Mol. Biol. 2023, 2693, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocchieri, L.; Karlin, S. Conservation among HSP60 sequences in relation to structure, function, and evolution. Protein Sci. 2000, 9, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macario, A.J.L.; Conway de Macario, E. Molecular chaperones: Multiple functions, pathologies, and potential applications. Front. Biosci. 2007, 12, 2588–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Guo, X.; Liu, X.M.; Liu, L.; Weng, Q.F.; Dong, S.J.; Knowlton, A.A.; Yuan, W.J.; Lin, L. Extracellular HSP60 induces inflammation through activating and up-regulating TLRs in cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 98, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Provenzano, A.; Passantino, R.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Cappello, F.; San Biagio, P.L.; Bulone, D. Oligomeric state and holding activity of Hsp60. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rye, H.S.; Burston, S.G.; Fenton, W.A.; Beechem, J.M.; Xu, Z.; Sigler, P.B.; Horwich, A.L. Distinct actions of cis and trans ATP within the double ring of the chaperonin GroEL. Nature 1997, 388, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Horwich, A.L.; Sigler, P.B. The crystal structure of the asymmetric GroEL-GroES-(ADP)7 chaperonin complex. Nature 1997, 388, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebeaud, M.E.; Mallik, S.; Goloubinoff, P.; Tawfik, D.S. On the evolution of chaperones and cochaperones and the expansion of proteomes across the Tree of Life. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2020885118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rye, H.S.; Roseman, A.M.; Chen, S.; Furtak, K.; Fenton, W.A.; Saibil, H.R.; Horwich, A.L. GroEL-GroES cycling: ATP and nonnative polypeptide direct alternation of folding-active rings. Cell 1999, 97, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilasi, S.; Bulone, D.; Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Campanella, C.; Marino Gammazza, A.; San Biagio, P.L.; Cappello, F.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L. Chaperonin of Group I: Oligomeric spectrum and biochemical and biological implications. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2018, 4, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wu, Z.; Liu, S.; Zuo, D.; Niu, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Qiao, L.; He, W.; Qiu, J.; Yuan, Y.; et al. Targeting PRMT3 impairs methylation and oligomerization of HSP60 to boost anti-tumor immunity by activating cGAS/STING signaling. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Campanella, C.; Bucchieri, F.; Cappello, F. Extracellular heat shock proteins in cancer: From early diagnosis to new therapeutic approach. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 86, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, A.M.; Conway de Macario, E.; Alessandro, R.; Cappello, F.; Macario, A.J.L.; Marino Gammazza, A. Missense Mutations of Human Hsp60: A Computational Analysis to Unveil Their Pathological Significance. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Alberti, G.; Vitale, A.M.; Paladino, L.; Campanella, C.; Rappa, F.; Gorska, M.; Conway de Macario, E.; Cappello, F.; Macario, A.J.L.; et al. Hsp60 Post-translational Modifications: Functional and Pathological Consequences. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, S.; Vitale, A.M.; Fucarino, A.; Scalia, F.; Vergilio, G.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L.; Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Pitruzzella, A. The Challenging Riddle about the Janus-Type Role of Hsp60 and Related Extracellular Vesicles and miRNAs in Carcinogenesis and the Promises of Its Solution. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Li, B.X.; Xiao, X. Toward Developing Chemical Modulators of Hsp60 as Potential Therapeutics. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2018, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.; Abdeen, S.; Salim, N.; Ray, A.M.; Washburn, A.; Chitre, S.; Sivinski, J.; Park, Y.; Hoang, Q.Q.; Chapman, E.; et al. HSP60/10 chaperonin systems are inhibited by a variety of approved drugs, natural products, and known bioactive molecules. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 1106–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlin, S.; Brocchieri, L. Heat shock protein 60 sequence comparisons: Duplications, lateral transfer, and mitochondrial evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 11348–11353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.S. Evolution of the chaperonin families (Hsp60, Hsp10 and Tcp-1) of proteins and the origin of eukaryotic cells. Mol. Microbiol. 1995, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewalt, K.L.; Hendrick, J.P.; Houry, W.A.; Hartl, F.U. In vivo observation of polypeptide flux through the bacterial chaperonin system. Cell 1997, 90, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perezgasga, L.; Segovia, L.; Zurita, M. Molecular characterization of the 5’ control region and of two lethal alleles affecting the hsp60 gene in Drosophila melanogaster. FEBS Lett. 1999, 456, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.H.; Nielsen, M.N.; Hansen, J.; Füchtbauer, A.; Füchtbauer, E.M.; West, M.; Corydon, T.J.; Gregersen, N.; Bross, P. Inactivation of the hereditary spastic paraplegia-associated Hspd1 gene encoding the Hsp60 chaperone results in early embryonic lethality in mice. Cell Stress. Chaperones 2010, 15, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnoni, R.; Palmfeldt, J.; Christensen, J.H.; Sand, M.; Maltecca, F.; Corydon, T.J.; West, M.; Casari, G.; Bross, P. Late onset motoneuron disorder caused by mitochondrial Hsp60 chaperone deficiency in mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013, 54, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostermann, J.; Horwich, A.L.; Neupert, W.; Hartl, F.U. Protein folding in mitochondria requires complex formation with hsp60 and ATP hydrolysis. Nature 1989, 341, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnoni, R.; Palmfeldt, J.; Hansen, J.; Christensen, J.H.; Corydon, T.J.; Bross, P. The Hsp60 folding machinery is crucial for manganese superoxide dismutase folding and function. Free Radic. Res. 2014, 48, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, B.; Fares, M.A.; Lund, P.A. Chaperonin 60: A paradoxical, evolutionarily conserved protein family with multiple moonlighting functions. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2013, 88, 955–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Knowlton, A.A. HSP60 trafficking in adult cardiac myocytes: Role of the exosomal pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007, 292, H3052–H3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bross, P.; Fernandez-Guerra, P. Disease-Associated Mutations in the HSPD1 Gene Encoding the Large Subunit of the Mitochondrial HSP60/HSP10 Chaperonin Complex. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2016, 3, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magen, D.; Georgopoulos, C.; Bross, P.; Ang, D.; Segev, Y.; Goldsher, D.; Nemirovski, A.; Shahar, E.; Ravid, S.; Luder, A.; et al. Mitochondrial hsp60 chaperonopathy causes an autosomal-recessive neurodegenerative disorder linked to brain hypomyelination and leukodystrophy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 83, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusk, M.S.; Damgaard, B.; Risom, L.; Hansen, B.; Ostergaard, E. Hypomyelinating Leukodystrophy due to HSPD1 Mutations: A New Patient. Neuropediatrics 2016, 47, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, T.; Yamamoto-Shimojima, K.; Ueda, Y.; Imai, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Imagawa, E.; Miyake, N.; Matsumoto, N. Independent occurrence of de novo HSPD1 and HIP1 variants in brothers with different neurological disorders—Leukodystrophy and autism. Hum. Genome Var. 2018, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cömert, C.; Brick, L.; Ang, D.; Palmfeldt, J.; Meaney, B.F.; Kozenko, M.; Georgopoulos, C.; Fernandez-Guerra, P.; Bross, P. A recurrent de novo HSPD1 variant is associated with hypomyelinating leukodystrophy. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 2020, 6, a004879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, B.; Davoine, C.S.; Dürr, A.; Paternotte, C.; Feki, I.; Weissenbach, J.; Hazan, J.; Brice, A. A new locus for autosomal dominant pure spastic paraplegia, on chromosome 2q24-q34. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000, 66, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.J.; Dürr, A.; Cournu-Rebeix, I.; Georgopoulos, C.; Ang, D.; Nielsen, M.N.; Davoine, C.S.; Brice, A.; Fontaine, B.; Gregersen, N.; et al. Hereditary spastic paraplegia SPG13 is associated with a mutation in the gene encoding the mitochondrial chaperonin Hsp60. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002, 70, 1328–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.; Svenstrup, K.; Ang, D.; Nielsen, M.N.; Christensen, J.H.; Gregersen, N.; Nielsen, J.E.; Georgopoulos, C.; Bross, P. A novel mutation in the HSPD1 gene in a patient with hereditary spastic paraplegia. J. Neurol. 2007, 254, 897–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bross, P.; Naundrup, S.; Hansen, J.; Nielsen, M.N.; Christensen, J.H.; Kruhøffer, M.; Palmfeldt, J.; Corydon, T.J.; Gregersen, N.; Ang, D.; et al. The Hsp60-(p.V98I) mutation associated with hereditary spastic paraplegia SPG13 compromises chaperonin function both in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 15694–15700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Syed, A.; Balaji, A. Hereditary spastic paraplegia SPG13 mutation increases structural stability and ATPase activity of human mitochondrial chaperonin. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parnas, A.; Nadler, M.; Nisemblat, S.; Horovitz, A.; Mandel, H.; Azem, A. The MitCHAP-60 disease is due to entropic destabilization of the human mitochondrial Hsp60 oligomer. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 28198–28203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Enriquez, A.S.; Li, J.; Rodriguez, A.; Holguin, B.; Von Salzen, D.; Bhatt, J.M.; Bernal, R. MitCHAP-60 and Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia SPG-13 Arise from an Inactive hsp60 Chaperonin that Fails to Fold the ATP Synthase β-Subunit. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Megumi, F.T.; Hasegawa, N.; Eguchi, T.; Tanoue, A.; Tamura, H.; Yamauchi, J. Data supporting mitochondrial morphological changes by SPG13-associated HSPD1 mutants. Data Brief 2016, 6, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enomoto, H.; Mittal, N.; Inomata, T.; Arimura, T.; Izumi, T.; Kimura, A.; Fukuda, K.; Makino, S. Dilated cardiomyopathy-linked heat shock protein family D member 1 mutations cause up-regulation of reactive oxygen species and autophagy through mitochondrial dysfunction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 1118–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bross, P.; Li, Z.; Hansen, J.; Hansen, J.J.; Nielsen, M.N.; Corydon, T.J.; Georgopoulos, C.; Ang, D.; Lundemose, J.B.; Niezen-Koning, K.; et al. Single-nucleotide variations in the genes encoding the mitochondrial Hsp60/Hsp10 chaperone system and their disease-causing potential. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 52, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Agsteribbe, E.; Huckriede, A.; Veenhuis, M.; Ruiters, M.H.; Niezen-Koning, K.E.; Skjeldal, O.H.; Skullerud, K.; Gupta, R.S.; Hallberg, R.; van Diggelen, O.P. A fatal, systemic mitochondrial disease with decreased mitochondrial enzyme activities, abnormal ultrastructure of the mitochondria and deficiency of heat shock protein 60. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993, 193, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckriede, A.; Agsteribbe, E. Decreased synthesis and inefficient mitochondrial import of hsp60 in a patient with a mitochondrial encephalomyopathy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1994, 1227, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huckriede, A.; Heikema, A.; Sjollema, K.; Briones, P.; Agsteribbe, E. Morphology of the mitochondria in heat shock protein 60 deficient fibroblasts from mitochondrial myopathy patients. Effects of stress conditions. Virchows Arch. 1995, 427, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones, P.; Vilaseca, M.A.; Ribes, A.; Vernet, A.; Lluch, M.; Cusi, V.; Huckriede, A.; Agsteribbe, E. A new case of multiple mitochondrial enzyme deficiencies with decreased amount of heat shock protein 60. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1997, 20, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macario, A.J.L.; Conway de Macario, E. The chaperone system in autoimmunity, inflammation, and virus-induced diseases: Role of chaperonins. In Stress: Immunology and Inflammation; Fink, G., Ed.; Handbook of Stress Series; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2023; Volume 5, pp. 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, F.W. The increasing prevalence of autoimmunity and autoimmune diseases: An urgent call to action for improved understanding, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2023, 80, 102266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohm, A.P.; Fuller, K.G.; Miller, S.D. Mimicking the way to autoimmunity: An evolving theory of sequence and structural homology. Trends Microbiol. 2003, 11, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Savill, J. Resolution of inflammation: The beginning programs the end. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, F.; Conway de Macario, E.; Marasà, L.; Zummo, G.; Macario, A.J.L. Hsp60 expression, new locations, functions and perspectives for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2008, 7, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macario, A.J.L.; Conway de Macario, E. Chaperonins in cancer: Expression, function, and migration in extracellular vesicles. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 86, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kol, A.; Lichtman, A.H.; Finberg, R.W.; Libby, P.; Kurt-Jones, E.A. Cutting edge: Heat shock protein (HSP) 60 activates the innate immune response: CD14 is an essential receptor for HSP60 activation of mononuclear cells. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantej, J.; Polasik, K.; Piotrowska, E.; Tukaj, S. Autoantibodies to heat shock proteins 60, 70, and 90 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Cell Stress. Chaperones 2019, 24, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino Gammazza, A.; Bucchieri, F.; Grimaldi, L.M.; Benigno, A.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L.; Zummo, G.; Cappello, F. The molecular anatomy of human Hsp60 and its similarity with that of bacterial orthologs and acetylcholine receptor reveal a potential pathogenetic role of anti-chaperonin immunity in myasthenia gravis. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2012, 32, 943–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carista, A.; Gratie, M.I.; Cappello, F.; Burgio, S. HSP60 and SARS-CoV-2: Les Liaisons Dangereuses. Biology 2025, 14, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manna, O.M.; Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Gratie, M.I.; Damiani, P.; Tomasello, G.; Cappello, F. The Role of Helicobacter pylori Heat Shock Proteins in Gastric Diseases’ Pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graeff-Meeder, E.R.; van Eden, W.; Rijkers, G.T.; Prakken, B.J.; Kuis, W.; Voorhorst-Ogink, M.M.; van der Zee, R.; Schuurman, H.J.; Helders, P.J.; Zegers, B.J. Juvenile chronic arthritis: T cell reactivity to human HSP60 in patients with a favorable course of arthritis. J. Clin. Investig. 1995, 95, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kleer, I.M.; Kamphuis, S.M.; Rijkers, G.T.; Scholtens, L.; Gordon, G.; De Jager, W.; Häfner, R.; van de Zee, R.; van Eden, W.; Kuis, W.; et al. The spontaneous remission of juvenile idiopathic arthritis is characterized by CD30+ T cells directed to human heat-shock protein 60 capable of producing the regulatory cytokine interleukin-10. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48, 2001–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladino, L.; Vitale, A.M.; Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Conway de Macario, E.; Cappello, F.; Macario, A.J.L.; Marino Gammazza, A. The Role of Molecular Chaperones in Virus Infection and Implications for Understanding and Treating COVID-19. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino Gammazza, A.; Légaré, S.; Lo Bosco, G.; Fucarino, A.; Angileri, F.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L.; Cappello, F. Human molecular chaperones share with SARS-CoV-2 antigenic epitopes potentially capable of eliciting autoimmunity against endothelial cells: Possible role of molecular mimicry in COVID-19. Cell Stress. Chaperones 2020, 25, 737–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchese, G.; Flöel, A. SARS-CoV-2 and Guillain-Barré syndrome: Molecular mimicry with human heat shock proteins as potential pathogenic mechanism. Cell Stress. Chaperones 2020, 25, 731–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasperkiewicz, M. COVID-19, heat shock proteins, and autoimmune bullous diseases: A potential link deserving further attention. Cell Stress. Chaperones 2021, 26, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilmartin, B.; Reen, D.J. HSP60 induces self-tolerance to repeated HSP60 stimulation and cross-tolerance to other pro-inflammatory stimuli. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004, 34, 2041–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanin- Zhorov, A.; Bruck, R.; Tal, G.; Oren, S.; Aeed, H.; Hershkoviz, R.; Cohen, I.R.; Lider, O. Heat shock protein 60 inhibits Th1-mediated hepatitis model via innate regulation of Th1/Th2 transcription factors and cytokines. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 3227–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin- Zhorov, A.; Tal, G.; Shivtiel, S.; Cohen, M.; Lapidot, T.; Nussbaum, G.; Margalit, R.; Cohen, I.R.; Lider, O. Heat shock protein 60 activates cytokine-associated negative regulator suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 in T cells: Effects on signaling, chemotaxis, and inflammation. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nussbaum, G.; Zanin-Zhorov, A.; Quintana, F.; Lider, O.; Cohen, I.R. Peptide p277 of HSP60 signals T cells: Inhibition of inflammatory chemotaxis. Int. Immunol. 2006, 18, 1413–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Sfady, M.; Nussbaum, G.; Pevsner-Fischer, M.; Mor, F.; Carmi, P.; Zanin-Zhorov, A.; Lider, O.; Cohen, I.R. Heat shock protein 60 activates B cells via the TLR4-MyD88 pathway. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 3594–3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen- Sfady, M.; Pevsner-Fischer, M.; Margalit, R.; Cohen, I.R. Heat shock protein 60, via MyD88 innate signaling, protects B cells from apoptosis, spontaneous and induced. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 890–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, G.; Knoflach, M.; Xu, Q. Autoimmune and inflammatory mechanisms in atherosclerosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 22, 361–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.G.; Lim, S.O.; Jung, G. Binding site analysis of human HBV pol for molecular chaperonin, hsp60. Virology 2002, 298, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Qian, L.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Deng, X.; Chen, X.; Sun, W.; Wei, H.; Qian, X.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Two-dimensional blue native/SDS-PAGE analysis reveals heat shock protein chaperone machinery involved in hepatitis B virus production in HepG2.2.15 cells. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2009, 8, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tanaka, Y.; Kanai, F.; Kawakami, T.; Tateishi, K.; Ijichi, H.; Kawabe, T.; Arakawa, Y.; Kawakami, T.; Nishimura, T.; Shirakata, Y.; et al. Interaction of the hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) with heat shock protein 60 enhances HBx-mediated apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 318, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, Y.; Ueno, Y.; Kobayashi, K.; Kakazu, E.; Shiina, M.; Inoue, J.; Tamai, K.; Wakui, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Ninomiya, M.; et al. Hepatitis B virus replication could enhance regulatory T cell activity by producing soluble heat shock protein 60 from hepatocytes. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 202, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, S.; Chen, L.; Xu, R.; Lv, Y.; Wu, D.; Guo, M.; et al. HSP60-regulated Mitochondrial Proteostasis and Protein Translation Promote Tumor Growth of Ovarian Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino Gammazza, A.; Campanella, C.; Barone, R.; Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Gorska, M.; Wozniak, M.; Carini, F.; Cappello, F.; D’Anneo, A.; Lauricella, M.; et al. Doxorubicin anti-tumor mechanisms include Hsp60 post-translational modifications leading to the Hsp60/p53 complex dissociation and instauration of replicative senescence. Cancer Lett. 2017, 385, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.N.; Choi, B.; Lee, K.W.; Lee, D.J.; Kang, D.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Song, I.S.; Kim, H.I.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, H.S.; et al. Cytosolic Hsp60 is involved in the NF-kappaB-dependent survival of cancer cells via IKK regulation. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Nikolic, D.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Barone, R.; Lo Cascio, F.; Mocciaro, E.; Zummo, G.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L.; Cappello, F.; et al. The dissociation of the Hsp60/pro-Caspase-3 complex by bis(pyridyl)oxadiazole copper complex (CubipyOXA) leads to cell death in NCI-H292 cancer cells. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2017, 170, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, Y.X.; Liu, T.J.; Su, H.F.; Samsamshariat, A.; Mestril, R.; Wang, P.H. Hsp10 and Hsp60 modulate Bcl-2 family and mitochondria apoptosis signaling induced by doxorubicin in cardiac muscle cells. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2003, 35, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, S.; Wen, Q. The multiple roles and therapeutic potential of HSP60 in cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 201, 115096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundtman, C.; Kreutmayer, S.B.; Almanzar, G.; Wick, M.C.; Wick, G. Heat shock protein 60 and immune inflammatory responses in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, V.; Faria, A.M. HSP60: Issues and insights on its therapeutic use as an immunoregulatory agent. Front. Immunol. 2012, 2, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Alberti, G.; Paladino, L.; Vitale, A.M.; Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Conway de Macario, E.; Campanella, C.; Macario, A.J.L.; Marino Gammazza, A. Functions and Therapeutic Potential of Extracellular Hsp60, Hsp70, and Hsp90 in Neuroinflammatory Disorders. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Li, G.; Yu, Q.; Liu, D.; Tang, X. HSP60 in cancer: A promising biomarker for diagnosis and a potentially useful target for treatment. J. Drug Target. 2022, 30, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tang, Y.; Luo, J.; Yang, Y.; Zang, H.; Ma, J.; Fan, S.; Wen, Q. High expression of HSP60 and survivin predicts poor prognosis for oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. BMC Oral. Health 2023, 23, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basset, C.A.; Rappa, F.; Lentini, V.L.; Barone, R.; Pitruzzella, A.; Unti, E.; Cappello, F.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L.; Leone, A. Hsp27 and Hsp60 in human submandibular salivary gland: Quantitative patterns in healthy and cancerous tissues with potential implications for differential diagnosis and carcinogenesis. Acta Histochem. 2021, 123, 151771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladino, L.; Vitale, A.M.; Santonocito, R.; Pitruzzella, A.; Cipolla, C.; Graceffa, G.; Bucchieri, F.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L.; Rappa, F. Molecular Chaperones and Thyroid Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paladino, L.; Santonocito, R.; Graceffa, G.; Cipolla, C.; Pitruzzella, A.; Cabibi, D.; Cappello, F.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L.; Bucchieri, F.; et al. Immunomorphological Patterns of Chaperone System Components in Rare Thyroid Tumors with Promise as Biomarkers for Differential Diagnosis and Providing Clues on Molecular Mechanisms of Carcinogenesis. Cancers 2023, 15, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Cipolla, C.; Graceffa, G.; Barone, R.; Bucchieri, F.; Bulone, D.; Cabibi, D.; Campanella, C.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Pitruzzella, A.; et al. Immunomorphological Pattern of Molecular Chaperones in Normal and Pathological Thyroid Tissues and Circulating Exosomes: Potential Use in Clinics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Luo, J.; Liu, S.; Zhan, Y.; Zang, H.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, J.; Fan, S.; et al. Overexpression of HSP10 correlates with HSP60 and Mcl-1 levels and predicts poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Biomark. 2021, 30, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ağababaoğlu, İ.; Önen, A.; Demir, A.B.; Aktaş, S.; Altun, Z.; Ersöz, H.; Şanl, A.; Özdemir, N.; Akkoçlu, A. Chaperonin (HSP60) and annexin-2 are candidate biomarkers for non-small cell lung carcinoma. Medicine 2017, 96, e5903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, F.; Di Stefano, A.; D’Anna, S.E.; Donner, C.F.; Zummo, G. Immunopositivity of heat shock protein 60 as a biomarker of bronchial carcinogenesis. Lancet Oncol. 2005, 6, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, F.; Di Stefano, A.; David, S.; Rappa, F.; Anzalone, R.; La Rocca, G.; D’Anna, S.E.; Magno, F.; Donner, C.F.; Balbi, B.; et al. Hsp60 and Hsp10 down-regulation predicts bronchial epithelial carcinogenesis in smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cancer 2006, 107, 2417–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitruzzella, A.; Burgio, S.; Lo Presti, P.; Ingrao, S.; Fucarino, A.; Bucchieri, F.; Cabibi, D.; Cappello, F.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L.; et al. Hsp60 Quantification in Human Gastric Mucosa Shows Differences between Pathologies with Various Degrees of Proliferation and Malignancy Grade. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.S.; Xu, Q.; Fu, X.Y.; Luo, W.S. Heat shock protein 60 overexpression is associated with the progression and prognosis in gastric cancer. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappello, F.; Bellafiore, M.; Palma, A.; David, S.; Marcianò, V.; Bartolotta, T.; Sciumè, C.; Modica, G.; Farina, F.; Zummo, G.; et al. 60KDa chaperonin (HSP60) is over-expressed during colorectal carcinogenesis. Eur. J. Histochem. 2003, 47, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, F.; David, S.; Rappa, F.; Bucchieri, F.; Marasà, L.; Bartolotta, T.E.; Farina, F.; Zummo, G. The expression of HSP60 and HSP10 in large bowel carcinomas with lymph node metastase. BMC Cancer 2005, 5, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappa, F.; Pitruzzella, A.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Barone, R.; Mocciaro, E.; Tomasello, G.; Carini, F.; Farina, F.; Zummo, G.; Conway de Macario, E.; et al. Quantitative patterns of Hsps in tubular adenoma compared with normal and tumor tissues reveal the value of Hsp10 and Hsp60 in early diagnosis of large bowel cancer. Cell Stress. Chaperones 2016, 21, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]