Abstract

Recent advances in artificial intelligence and natural language processing have been widely used in recent years, and one of the best applications of these technologies is conversational agents. These agents are computer programs that can converse with users in natural languages. Developing conversational agents using artificial intelligence techniques is an exciting prospect in natural language processing. In this study, we built an intelligent conversational agent using deep learning techniques. We used a sequence-to-sequence model with encoder–decoder architecture. This encoder–decoder uses a recurrent neural network with long–short-term memory cells. The encoder was used to understand the user’s question, and the decoder was to provide the answer.

1. Introduction

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and natural language processing (NLP) have been widely used in recent years, and one of the best uses for these technologies is conversational agents. These agents are computer programs that can converse with users in natural languages. They are frequently used to automate hotel booking, flight booking, shopping, etc. Additionally, they can be integrated into messaging platforms, mobile apps, websites, and other communication channels [1,2].

Developing conversational agents using AI techniques is an interesting prospect in NLP. Many research and development projects use machine learning algorithms, deep learning, and NLP techniques to develop conversational agents. Additionally, developers can use many frameworks and platforms to build these applications, such as Google’s Dialogflow [3], IBM’s Watson [4], Microsoft’s Bot Framework [5], and Amazon’s Lex [6]. However, they also have drawbacks, such as NLP service lock-in and a high cost.

Previously, conversational agents have been designed using manually written rule-based architecture and retrieval techniques. With the advent of deep learning, these traditional models have been replaced by neural networks. In particular, recurrent encoder–decoder models [7] have been used in neural machine translation [8] and are also used to develop agents.

In this paper, we have developed a conversational agent using deep learning techniques. We used a sequence-to-sequence (Seq2Seq) model with encoder–decoder architecture [9]. This encoder–decoder uses a recurrent neural network with LSTM cells.

2. Related Work

A conversational agent or chatbot is a computer program that can converse with a human being in using natural language (NL). It can be a simple rule-based agent or an AI-based application that leverages natural language understanding (NLU). It uses NLP algorithms and machine learning (ML) to understand and interpret users’ inputs and generates responses using NL. These applications are often used to automate tasks, such as customer service, e-commerce, flight booking, etc. They can be integrated into mobile applications, websites, or social networks to provide users with quick and personalized responses.

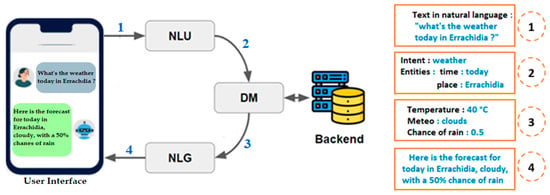

The architecture of an agent usually consists of three essential components [10,11]. The first one is the NLU component, which receives NL text from the user interface (label 1 in Figure 1) and extracts intents and entities (label 2). This representation is then handled by the Dialogue Manager (DM), which examines the context of the conversation and can perform different actions depending on the intent, such as calling an external service to retrieve data (label 3). Finally, a natural language generation (NLG) component produces a response, typically an NL sentence (label 4).

Figure 1.

A typical architecture for conversational agents (adapted from Refs. [11,12]).

Generally, we implement this type of application either by reusing services offered by some platforms and frameworks [3,4,5,6] or by developing them from scratch using existing techniques, such as NLP, machine learning algorithms, or deep learning techniques.

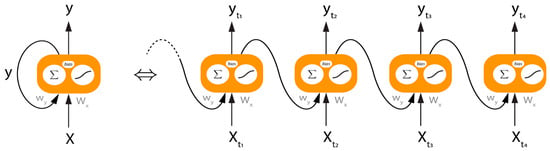

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) are artificial neural networks specifically designed to process sequential data (for instance, text and sound) used by agents. Unlike Feed-Forward Neural Networks (FFNN) that process fixed-length inputs, RNNs can handle variable-length sequences, x = (x1, …, xn), as inputs and produce a sequence of hidden states, y = (yt1, …, ytn), using a recurrent loop. This is also called unrolling the network, as shown in Figure 2. X is the input sequence, yti-1 is the output sequence, yi is hidden state sequence, Wx and Wy are the network weights.

Figure 2.

Unfolding of an RNN over 4 time steps (adapted from Ref. [9]).

For long sequences, implementations of RNNs are rarely used because the network cannot remember long-term dependencies (vanishing or exploding gradients), and thus, is challenging to train. For example, given the following sentence: “Errachidia is one of the tourist regions of Morocco; it is located in the southeast of the country”. The RNNs might not consider the connection between the words “Errachidia” and “it”. That is why LSTM [13] or Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) [14] were developed to address the problem of long-term dependencies faced by RNNs, allowing models to learn how to memorize short- and long-term information. LSTMs and GRU have been successfully used in the development of conversational agents for NLU and NLG.

Then, Seq2Seq architecture is introduced as a dialogue and machine translation system model [9]. It consists of two RNNs, an encoder and a decoder. An encoder takes a sequence as an input and processes one symbol at each time step. Its goal is to convert a sequence of characters into a context vector representing the intent of the sequence. The decoder generates another output sequence from the context.

More recently, transformer architecture has been introduced, which uses attention mechanisms to allow models to consider the full context when they are generating text. Transformer models, such as Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) [15] and Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPT) [16], have significantly improved performance in various NLP tasks, including developing conversational agents, for instance, the development of ChatGPT based on GPT3 [16].

In the next section, we present a practical approach used to develop a conversational agent using the Seq2Seq model with LSTM cells in the process of encoder decoder, in which the encoder is used to understand the question and the decoder to provide the answer.

3. Approach

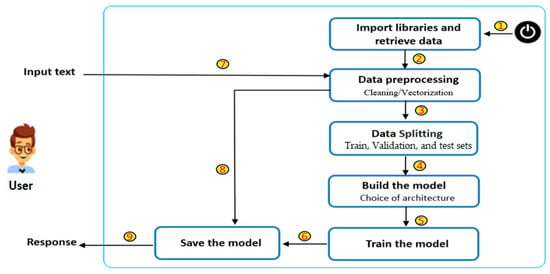

Our approach in this study consists of five steps. First, we import data we want to use (label 1 in Figure 3). In the second step, we preprocess data (label 2). In the third step, data are divided into two sets, one for training and the other for testing the model (label3). In the fourth step, a Seq2Seq model is built using encoder–decoder architecture, with LSTM cells for both components (label 4). An encoder is used to understand the user’s message, while a decoder is used to generate a response. Finally, the model is trained and saved (label 6) and used to converse with users (labels 7, 8, and 9).

Figure 3.

Overview of our approach.

4. Experiment and Results

4.1. Dataset

The dataset used for building the conversational agent called “Cornell Movie Dialogue Corpus” was extracted from the Cornell University website [17]. This corpus contains a large, metadata-rich collection of conversations. There are mainly two text files in the dataset: the first file contains the conversation id, person id, movie id, and the actual conversation, and the second file contains the mapping of conversations between different users. Generally, this corpus includes 221,616 conversation exchanges between 10,292 pairs of movie characters. It involves 83,098 dialogues between 9035 characters from 617 movies. There are 304,714 utterances in total.

4.2. Data Preprocessing

Preprocessing is a significant step in preparing data for training the Seq2Seq model, and it involves several substeps. First, we created a dictionary that associates each conversation line with its ID from the first file. We made a nested list of all conversations in the second file. Then, we separated all data into two lists that contain questions and answers. Moreover, all capital letters, punctuation marks, and some characters (-, #, $, etc.) are removed from the question-and-answer lists to obtain clean data. Our process required fixed-length questions and answers by omitting longer ones and padding for the shorter ones using a specific token. Then, we created a vocabulary list of all the words in the dataset. Finally, we converted the words in the question-answer lists to train our model into vectors. We call this process vectorization. It can be achieved either by using a localist representation, such as one-hot, or a distributed representation, such as GloVe or Word2Vec. In our case, we used GloVe to obtain vector representations for words in our corpus.

4.3. Splitting Data

Splitting data refers to dividing a dataset into three subsets: a training set, a validation set, and a testing set. The training set is a subset of data used to train the model. The validation set was used to tune the model’s hyperparameters. In contrast, the testing evaluates the model’s performance after training and tuning the hyperparameters.

In our experiment, we divided our dataset into 90% for training data, 5% for validation data, and 5% for testing data.

4.4. Building the Model

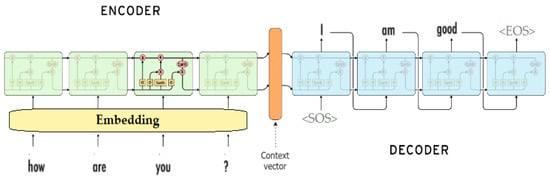

Keras [18] and TensorFlow [19] are open-source software libraries for building and training deep learning models, which are used for building Seq2Seq models using encoder–decoder architecture with LSTM cells. Keras is a high-level neural network API written in Python and runs on top of TensorFlow. It provides a set of pre-built layers, including LSTM layers. Figure 4 shows the architecture of our model that we built using these APIs. It consists of an encoder and a decoder, usually RNNs such as LSTMs, which we used in our experiment. The encoder takes an input sequence, such as an English sentence, and converts it into a context vector representing the information in the input sequence. A decoder uses this context vector to generate an output sequence, such as a response to a user’s message.

Figure 4.

Architecture of the Seq2Seq model (adapted from Ref. [9]).

4.5. Training the Model

We trained the model on the preprocessed dataset with different values for the hyperparameters: the learning rate, number of epochs, batch size, and number of LSTM cells. We took categorical cross-entropy as our loss function, the metric was accuracy, and the optimizer used was adam. Table 1 shows three configurations of these hyperparameters that we used to train the model.

Table 1.

Different values for the hyperparameters of our models.

4.6. Results

In this experience, we obtained our best results with the following values: 0.001 (learning rate), 11 epochs, a batch size of 32, and 256 LSTM cells. Upon training, the model achieved a training accuracy of around 83.80%, while the validation accuracy was approximately 83.03%. We tested our model on the test set, and we obtained an accuracy of 83.50%. The results of our experiment are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Accuracies of the models in the four configurations.

Generally, the results of our models appear to be overfitted since we observed good accuracy on the training data, but a poor performance on the validation data. Several techniques can be used to avoid overfitting, including regularization techniques such as dropout, early stop, and feeding the model more data.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents an example of a question–answer conversational agent and how it can be developed using techniques in deep learning and natural language processing. For our implementation, we used Seq2Seq architecture with LSTM cells. We have also shown the results of our training of this model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.O., L.B., I.K. and A.J.; methodology, C.O. and L.B.; software, C.O. and L.B.; validation, I.K. and A.J.; formal analysis, C.O., L.B., I.K. and A.J.; investigation, C.O. and L.B.; resources, C.O. and L.B.; data curation, C.O. and L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.O. and L.B.; writing—review and editing, I.K. and A.J.; visualization, C.O., L.B., I.K. and A.J.; supervision, I.K. and A.J.; project administration, I.K. and A.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Center for Scientific and Technical Research (CNRST) under a Moroccan project called “Al-Khawarizmi Project in AI and its Applications”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data have been presented in the main text.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brandtzaeg, P.B.; Følstad, A. Why people use chatbots. In Internet Science: 4th International Conference, INSCI 2017, Thessaloniki, Greece, November 22–24, 2017, Proceedings 4; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 377–392. [Google Scholar]

- Lebeuf, C.; Storey, M.-A.; Zagalsky, A. Software bots. IEEE Software 2017, 35, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dialogflow. Available online: https://dialogflow.com/ (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Watson Assistant. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/cloud/watson-assistant/ (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Microsoft Bot Framework. Available online: https://dev.botframework.com/ (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Amazon Lex. Available online: https://aws.amazon.com/en/lex/ (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Cho, K.; Van Merriënboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.1078. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, K.; Van Merriënboer, B.; Bahdanau, D.; Bengio, Y. On the properties of neural machine translation: Encoder-decoder approaches. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1259. [Google Scholar]

- Sojasingarayar, A. Seq2seq ai chatbot with attention mechanism. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.02767. [Google Scholar]

- Sarikaya, R. The technology behind personal digital assistants: An overview of the system architecture and key components. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2017, 34, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulou, E.; Moussiades, L. An overview of chatbot technology. In Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations: 16th IFIP WG 12.5 International Conference, AIAI 2020, Neos Marmaras, Greece, June 5–7, 2020, Proceedings, Part II 16; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 373–383. [Google Scholar]

- Kusal, S.; Patil, S.; Choudrie, J.; Kotecha, K.; Mishra, S.; Abraham, A. AI-based Conversational Agents: A Scoping Review from Technologies to Future Directions. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 92337–92356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.; Gulcehre, C.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Empirical evaluation of gated recurrent neural networks on sequence modeling. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.3555. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Amodei, D. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Dataset. Available online: https://www.cs.cornell.edu/cristian/CornellMovieDialogsCorpus.htm (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Keras. Available online: https://keras.io/api/ (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Tensorflow. Available online: https://www.tensorflow.org/guide (accessed on 2 February 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).