Abstract

The need to automate the disease identification processes is frequent because manual identification is time-consuming and needs professional skills to be performed; hence, it may improve effectiveness and precision. This paper has resolved the problem by using image classification with deep learning to detect silkworm diseases. A Kaggle-sourced dataset of work of 492 labelled samples (247 diseased and 245 healthy) was used with a stratified division into 392 training and 100 testing samples. The transfer learning method was performed on two Residual Network models, ResNet-18 and ResNet-50, in which pretrained convolutional layers were frozen and the last fully connected layer was trained to conduct binomial classification. Performance was measured by standard evaluation metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and confusion matrices.

1. Introduction

Sericulture, or the rearing of a silkworm, Bombyx mori, to yield silk, continues to be an important source of revenue and rural income, especially in developing Asian and Eastern European areas. Being a low-investment and high-labor agricultural practice, it employs millions of farmers and helps stabilize agrarian economies socio-economically [1]. In addition to economic importance, sericulture contributes to the saving of biodiversity and sustainable exploitation of natural resources [2]. Nevertheless, silkworm diseases are very susceptible to the sericulture sector with the potential of producing huge losses. One of the devastating infections is the microsporidiosis (pebrine) transmitted by Nosema bombycis that still presents a severe threat to the production of silkworm eggs, even after decades of control [3]. Over 60 percent of cocoon losses are due to viral diseases including those occurring in Bombyx mori nucleopolyhedrovirus (BmNPV), and no effective treatment has been produced to date, making the genetic breeding of resistance a high research priority [4]. The physiology, development, and immune response of silkworms are also under the influence of environmental stresses such as increase in temperatures and irregular rain patterns, which increases the risk of disease outbreak further [5]. This is most particularly vulnerable at the fifth instar stage, where the optimum conditions of temperature and humidity are very important in the formation of the cocoon [6]. These biological and ecological issues signify the necessity of scalable, accurate and real-time disease detection in order to protect the productivity, as well as the long-term sustainability of sericulture.

Silkworm and other farm diseases are manually diagnosed, which appears to be slow, imprecise, and susceptible to human error. There are a number of challenges presented by this approach that restrict its applicability and use in actual sericulture scenarios. To begin with, the disease identification that relies on the expertise of specialists is frequently unavailable in rural or low-resource areas that practice sericulture. The farmers are normally called upon to meet with the extension officers or other special personnel to delay the process of diagnosis and timely intervention [7]. These delays enhance chances of spreading the disease and loss of cocoon yield particularly in fast spreading infections such as pebrine. Also, manual inspection process is time-consuming, physically viable, and impractical in large-scale operations. To illustrate, the research works on grape and fruit disease detection have demonstrated that the use of human expertise may not be quick and accurate in field conditions [8,9]. In addition, manual procedures are not reproducible and consistent. Diagnosis may not be agreed between two experts related to subjectivity in cases of the assessment of silkworm diseases in the early stage or overlapping symptoms between the diseases. This has led to automated systems where the inconsistencies are countered by using data-driven methods of classification [10]. Finally, there is a limited incorporation of the expertise knowledge into the real-time responsive systems. This results in the lack of practical recommendations at the initial stages of infection. Disease management efficiency can be drastically improved with AI-driven solutions as already demonstrated by recent studies in smart agriculture, which reduces the amount of human involvement and allows 24 h monitoring [11,12].

2. Literature Review

Liu and Wang [13] had carried out a detailed survey on the application of deep learning in detecting plant diseases and pests. They divided the existing literature into classification, detection, and segmentation networks, in the classification, and detection networks, CNN architectures outperformed traditional methods in accuracy and efficiency. Deep belief networks and convolutional neural networks were used by Feng and Hua [14] to classify pest and disease-affected leaf images. While successful in determining some classes, their model had issues with scaling with more types of disease indicating the difficulties of generalized models. Kundur and Mallikarjuna [15] came up with faster R-CNN models with EfficientNet B4 and B7 on insect pest classification. Their model reached the accuracy of up to 99% with the IP102 dataset, indicating the effectiveness of the use of deep CNNs and large, annotated image sets to detect pests. With the help of infrared sensors and CNNs, Bick et al. [16] applied deep learning to animal health by assessing the infection of flying insects. Their system detected fungal infections in insects with an 85.6 accuracy, and this may point to the advantages of deep learning in real-time biosurveillance. Dolapatsis et al. [17] compared various CNN models to identify vine disease and MobileNet V2 was considered the most accurate and efficient model, even compared to custom field-collected datasets with 94% accuracy. This implies that mobile receptive deep learning models are suitable in actual farm environments. Uttarwar et al. [18] proposed an EfficientNetB0-based hybrid model that is lightweight and can identify both unusual and typical plant diseases. This model is intended to be deployed in low-resource settings and demonstrates the potential of efficient architectures in application in agriculture. Shoaib et al. [19] gave the future outlook of the review and highlighted how vision transformers and more sophisticated architectures were gaining prominence in the detection of pests and diseases. They emphasize classification of over 95% and segmentation/detection of over 90 percent among tasks. Wang et al. [20] comparatively examined the development of deep learning in the field of agricultural diagnostics and addressed such architecture as YOLO, U-Net, and ResNet. They stressed that deep models combined with transfer learning and high-quality datasets might considerably help to minimize the losses of agricultural products and enhance precision farming results.

A comparative study was carried out by Lokhande and Thool [21] on CNN models of plant leaf disease detection in maize and soybean. The study identified that the model accuracy, depending on crop type and preprocessing choices, varied significantly, and ResNet variants have promising generalization across diseases using transfer learning and interpretability tools. Nwaneto and Yinka-Banjo [22] compared MobileNet V2, MobileNet V3, and a standard CNN on more than 20,000 plant diseases images. The results of their study showed that the custom CNN was the most effective in the test accuracy (94.48%), which could imply its superiority over pretrained lightweight models in particular plant disease detection. Dey et al. [23] tested five CNN models on the identification of various stressors on rice plants, such as pests, fungus, and nutrient deficiencies. VGG19 was better at detecting pests whereas ResNet50 was better at detecting potassium deficiency. Their experiment points to model-specific advantages in reaction to stress type. A comparative study of CNN adaptation in the field of breast cancer detection in mammography images was conducted by Ramadhani [24]. R-CNN and SD-CNN were discovered to reach a significantly higher diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, and AUC score, indicating that architectural modifications can have a significant impact on clinical performance. El Sakka et al. [25] conducted a review of more than 115 articles about CNN application in agriculture as a smart field, where multimodal data are involved, such as RGB, multispectral, and UAV imagery. It was discovered that CNNs performed the same tasks in consistency outperforming traditional ML models whether in classification or segmentation (weed, disease, and yield related). Nasra and Gupta [26] made a maize leaf disease comparison between CNN and ResNet50. ResNet50 was more accurate (92% vs. 91%), but CNN used fewer resources (via its residual learning) thus illustrating trade-offs in deployment contexts. Xuan et al. [27] created a VAC-CNN visual analytics system that is able to compare various CNN architectures based on qualitative and quantitative information. The system facilitated a better comprehension of CNN behaviors during image classification, and thus it is a handy system in selecting models in both agricultural and biomedical tasks. Saleem et al. [28] compared different CNNs and optimizers to use at classifying plant diseases on the PlantVillage dataset. The Xception architecture that was trained on Adam optimizer demonstrated the best validation accuracy (99.81) and F1-score (0.9978) than traditional CNNs and hybrid architectures.

The recent breakthroughs in deep learning have dramatically changed the horizon in disease detection both in agriculture and biomedicine. A variety of reports have shown that convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and their derivatives are effective in identifying plant diseases, pests, and even detecting early-stage infections in animals by using image-based classification and object-detection methodologies. Residual Networks (ResNets) are also among the most commonly known CNN families due to their high feature extraction capabilities and stable training that is made possible by residual connections. This paper thus concentrates on comparative assessment of the ResNet-18 and ResNet-50 in the classification of images of silkworms as diseased and healthy. The work seeks to understand which architecture is more feasible and effective to use in sericulture applications particularly under a resource-constrained setting by analyzing their predictive performance, generalization ability, and training behavior using a limited dataset.

3. Methodology

In this study, a Kaggle-hosted silkworm disease dataset as shown in Table 1. with a total of 492 labeled images was used as experimental analysis. The dataset will be divided into two parts of the 392 images to be trained on (197 diseased, 195 healthy) and 100 to be tested (50 diseased, 50 healthy). The equal representation of the two types is such that the models are not biased against one of the classes and this makes it easy to objectively assess the classification performance. The images were placed in either the Diseased or the Undiseased category according to visual features that include discoloration, growth abnormalities, or surface abnormalities, which are reliable signs of pathogenic infection in silkworms.

Table 1.

Dataset distribution for training and testing.

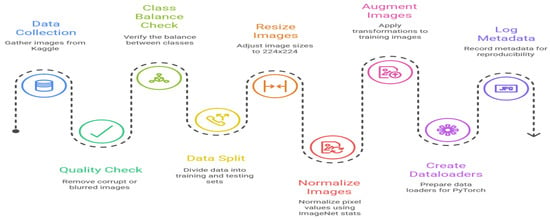

All the images were preprocessed to be uniformed so that the deep learning models can take them in. Images were denoised down to a predefined resolution that was fitable into the ResNet architectures and pixel intensity values were scaled to [0,1] to ensure better convergence in the training process. Artificially expand variability in the data by administering data augmentation methods such as horizontal flipping, random rotation, and slightly zooming the data, were used to avert overfitting. This was especially significant in the context of the relatively small dataset, which is a key drawback. Deep models can generalize only to a limited dataset due to their already small representation capacity (ex: ResNet-50), particularly when the desired architecture has a large representational capacity. Preprocessing and augmentation were thus important in maintaining the trade-off between size of dataset and the complexity of the models as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Dataset preparation and processing timeline.

Although the dataset offers a good basis on which to train and test the models, its small size limits a wider generalizability in the different environmental and rearing environments. The practical silkworm farming entails changes in light, stages of larval instar, and contact with pathogens, which are not well-modeled here. Therefore, it is concluded that this dataset may be regarded as a baseline experimental dataset, and the validation of the data on larger, multi-institutional image collections will be required to make it robust when applied to real-world sericulture practice.

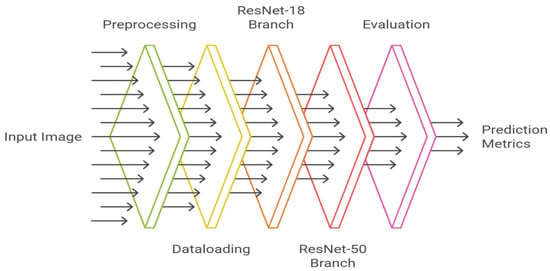

In order to compare the categories of diseased and disease-free silkworms, the current work is aimed at two popular deep convolutional neural network (CNN) models, namely ResNet-18 and ResNet-50 as shown in Figure 2. The two models are both part of the family of Residual Networks (ResNets), described as the addition of skip connections. Such residual ties permit information to skip over one or more convolutional layers and may help resolve the vanishing gradient issue with deep networks, as well as permit training of very deep networks to stabilize. Whereas ResNet-18 is relatively shallow with 18 layers, with its focus on computational efficiency and quicker training, ResNet-50 uses 50 layers, and thus, it can extract richer hierarchical features but with a higher computational cost. This is the difference that causes the two models to be a perfect couple when it comes to comparative analysis on small data like the current silkworm image gallery.

Figure 2.

Model architecture diagram for ResNet-18 vs. ResNet-50.

ResNet-18 and ResNet-50. Both are based on the concept of residual learning, where identity mappings are used to enable effective training of deeper networks.

where F(x,W) is the grouped convolutional, batch normalization, and ReLU layers, and the shortcut connection +x provides gradient flow in the deepest networks.

The models were implemented in the PyTorch deep learning framework and executed on a workstation equipped with NVIDIA GPU, 32 GB RAM. Both models were initialized with weights pretrained on the ImageNet dataset, ensuring robust feature extraction from early layers. In line with transfer learning principles, all convolutional layers of ResNet-18 and ResNet-50 were frozen, and only the final fully connected (FC) classification layer was replaced and fine-tuned to adapt the models to the binary classification task (diseased vs. undiseased). This approach not only reduced training time but also prevented overfitting, which is a known risk when using small datasets with very deep models. The final output layer of both ResNet-18 and ResNet-50 is modified to perform binary classification. The prediction logits zzz are passed through the softmax function to compute class probabilities:

where, c = 0 represents the diseased class and c = 1 denotes the healthy class.

Cross function entropy loss function is used for the training of models, which surplus the incorrect predictions

where, yi,c is the one hot encoded ground truth for sample i, and P(y = c|xi) is the predicted probability.

The Adam optimizer was used to optimize the model with a weight decay of 1 × 10−4 to offer L2 regularization and a learning rate of 0.0001. The trade-off between computational efficiency and gradient stability was to use a batch size of 32 as shown in Table 2. All models were trained using up to 30 epochs, although, in the event of no improvement in validation loss, an early stopping rule with a patience of 3 was used. In the course of training, the measures of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score were monitored as the key evaluation metrics, and confusion matrices were made where they were used to gain a better idea of the performance of the model across individual classes. This was a guarantee of a holistic evaluation of the not only general accuracy but also the capacity of the model to identify the minority cases with a proper classification without favoritism to either category.

Table 2.

Training hyperparameters for ResNet-18 and ResNet-50.

4. Result and Discussion

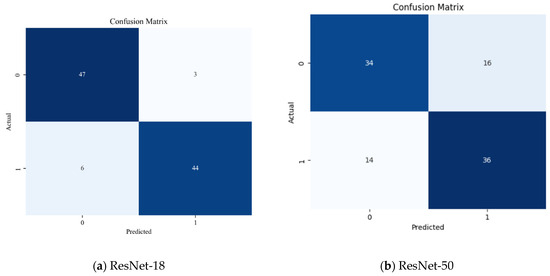

The relative performance of either ResNet-18 or ResNet-50 on silkworm disease data shows the obvious differences in the ability to predict. As shown in Table 3, ResNet-18 achieved a total accuracy of 91% with a precision of 0.886, recall at 0.94, and F1-score of 0.912. By comparison, ResNet-50 had an accuracy of only 70% with comparatively lower areas of precision (0.7083), recall (0.68), and F1-score (0.693). These findings are clear evidence that the ResNet-18 was able to generalize better on unseen samples whereas ResNet-50 suffered as a result of overfitting behaviors of deeper networks when using small datasets.

Table 3.

Comparative performance metrics of ResNet-18 and ResNet-50.

The confusion matrices (Figure 3a,b) are used to show additional information about the distribution of predictions by the various classes. In the case of ResNet-18 (Figure 3a), the model was able to accurately classify 47/50 diseased silkworms and 44/50 non-diseased samples. This illustrates a sense of balanced classification and not being biased toward either of the classes. In contrast, ResNet-50 (Figure 3b) erroneously classified a greater percentage of the samples: only 34 and 36 diseased and undiseased samples had been identified as true, respectively. The misclassification rate of the higher value suggests that ResNet-50 was unable to find enough discriminative features in the small dataset.

Figure 3.

ResNet-18 vs. ResNet-50 confusion matrix comparison.

The results obtained during the comparative analysis make it clear that ResNet-18 performed better than ResNet-50 in the case of silkworm disease classification. ResNet-18 demonstrates greater accuracy (91%) and balanced results in the confusion matrix, which explains its superior performance depending on the depth of the network, which was appropriate, regarding the size of the dataset. ResNet-18 has only a small dataset of 492 images, yet it could effectively extract key discriminative features without overfitting, and exhibited good generalization on unseen test data. Conversely, ResNet-50 produced the lowest level of accuracy of 70 percent. The more intricate design of ResNet-50, which is effective with large-scale data as in ImageNet, is a drawback when the training data are limited. The increased number of parameters in it increases the chances of memorization over generalization, resulting in overfitting and poor performance on new samples. The finding supports the established fact that model complexity must be equated with the scale of data to achieve optimal results.

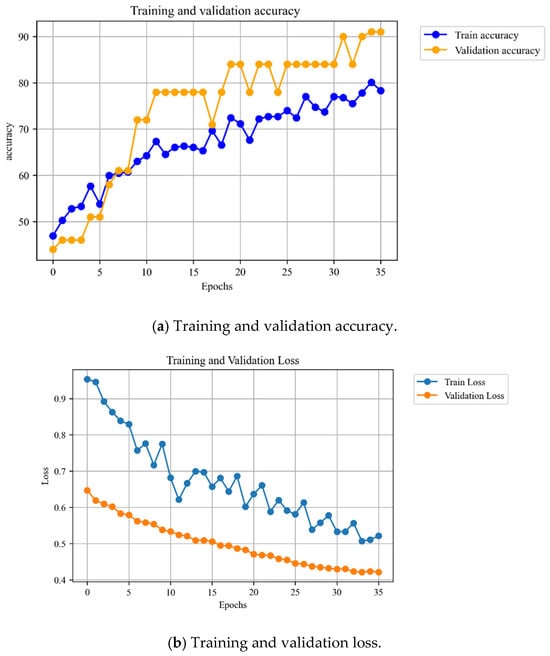

In order to further examine learning behavior of the models, training and validation curves were observed during epochs. Figure 4a shows the trends of accuracy throughout training. The accuracy of the validation could be found to rise gradually and reach the final level of the test scores of ResNet-18 (similarly, 91 percent). Notably, the validation accuracy was always better than the training accuracy, which indicates that the model generalized and it did not just memorise the training samples. This implies the strength of ResNet-18, even with a small dataset. The training and validation loss curve are depicted in Figure 4b. The curves show the clear down trend, which attests the effective learning across the epochs. Validation loss was stabilized at 0.42, but training loss kept on decreasing albeit fluctuating. The comparatively smooth convergence of validation loss with minimal steep departure of training loss also demonstrates that ResNet-18 did not overfit to a substantial degree. ResNet-50, in contrast, exhibited unsteady validation patterns in the early experiments (not shown), indicating its ineffective generalization to this dataset.

Figure 4.

Accuracy and validation plots for the ResNet 18 models.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, a comparative analysis of ResNet-18 versus ResNet-50 was conducted on a small, balanced (492 images) silkworm disease-predictive dataset. The findings show that the optimal model to use in the present dataset is ResNet-18 with the highest accuracy (91), with robust class-wise performance and low bias. Its shallowness enables easy learning without overfitting, whereas it is safer in comparison with deeper ResNet-50, which had poor results because of its complexity and the risk of overfitting on small data volumes.

To enhance generalization and robustness, first, smaller datasets (focusing on single disease types, different larval instar stages, and field-scale environmental factors) will have to be substituted by larger and more diverse datasets (representing a broader range of diseases and multiple conditions of environmental factors). Second, utilizing image segmentation methods before the classification may make the models more interpretable in that the diseased areas of the silkworm body are isolated, which reinforces the diagnostic procedure. Lastly, the introduction of lightweight deep learning models to mobile devices represents a chance to provide real-time diagnostic support to farmers directly to help them detect diseases early and treat them in time in realistic sericulture contexts.

Author Contributions

The research concept and overall study design were developed by K.M. and S.C.; The methodological framework and experimental design were formulated by K.M. and P.P.; Implementation of algorithms, model development, and software coding were carried out by K.M. and S.C.; The accuracy and reliability of the results were verified by S.C. and P.P.; Statistical evaluation and analytical interpretation of the results were performed by S.C. and P.P.; Data collection, experimentation, and execution of the research work were conducted by K.M.; Dataset preparation, organization, and preprocessing were managed by K.M. and S.C.; The initial manuscript draft was written by K.M.; The manuscript was critically reviewed, revised, and refined by K.M.; Figures, graphs, and visual representations of results were designed by K.M. and P.P.; Overall guidance, mentorship, and monitoring of the research process were provided by S.C.; Planning, coordination, and administrative management of the project were handled by K.M. and S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

I thank the farmer who provided the information about silkworm and mulberry leaves diseases and preventions from rural area Chakan, Pune. I thank my guide, Shwetambari Chiwhane, for continuous guidance and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hăbeanu, M.; Gheorghe, A.; Mihalcea, T. Silkworm Bombyx mori—Sustainability and economic opportunity, particularly for Romania. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agoston, C.P.; Dezmirean, D.S. Artificial Diet of Silkworms (Bombyx Mori) Improved With Bee Pollen-Biotechnological Approach in Global Centre of Excellence For Advanced Research. Bull. UASVM Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 77, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rahul, K.; Manjunatha, G.R.; Sivaprasad, V. Pebrine monitoring methods in sericulture. In Methods in Microbiology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 49, pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Zhu, F.; Chen, K. The mechanisms of silkworm resistance to the baculovirus and antiviral breeding. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2023, 68, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makne, H.R. Impact of global warming on sericulture and silk industry. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2025, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, A.; Choudhary, S.; Attri, K.; Afreen, S.; Bali, K.; Gupta, R.K. Response of Silkworm (Bombyx mori L.) Breeds to Temperature and BmNPV Stress. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 2332–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomathy, B.; Nirmala, V. Survey on plant diseases detection and classification techniques. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Advances in Computing and Communication Engineering (ICACCE), Sathyamangalam, India, 4–6 April 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Ding, Z.; Tian, L.; He, D.; Li, S.; Wang, H. Grape leaf disease identification using improved deep convolutional neural networks. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awate, A.; Deshmankar, D.; Amrutkar, G.; Bagul, U.; Sonavane, S. Fruit disease detection using color, texture analysis and ANN. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Green Computing and Internet of Things (ICGCIoT), Greater Noida, India, 8–10 October 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 970–975. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, M.M.; Ohi, A.Q.; Mridha, M.F. A multi-plant disease diagnosis method using convolutional neural network. In Computer Vision and Machine Learning in Agriculture; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.T.; Dipto, D.R.; Shib, S.K.; Shufian, A.; Hossain, M.S. Advanced Neural Networks for Plant Leaf Disease Diagnosis and Classification. In Proceedings of the 2025 Fourth International Symposium on Instrumentation, Control, Artificial Intelligence, and Robotics (ICA-SYMP), Bangkok, Thailand, 15–17 January 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gunawan, G.; Sya’bani, A.Z.; Anandianshka, S. Expert system for diagnosing diseases in corn plants using the navies bayes method. J. Mantik 2024, 8, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, X. Plant disease and pests detection based on deep learning: A review. Plant Methods 2021, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.K.; Hua, H.X. Research of image recognition of plant diseases and pests based on deep learning. Int. J. Cogn. Inform. Nat. Intell. 2021, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundur, N.C.; Mallikarjuna, P.B. Insect pest image detection and classification using deep learning. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2022, 13, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bick, E.; Edwards, S.; De Fine Licht, H.H. Detection of insect health with deep learning on near-infrared sensor data. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolaptsis, K.; Morellos, A.; Tziotzios, G.; Anagnostis, A.; Kateris, D.; Bochtis, D. Investigation of Deep Learning Architectures for Disease Identification of Vines in Agricultural Environments. In Proceedings of the 2023 6th Experiment@ International Conference (exp. at’23), Évora, Portugal, 5–7 June 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Uttarwar, M.; Chetty, G.; Yamin, M.; White, M. An novel deep learning model for detection of agricultural pests and plant leaf diseases. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Computer Science and Data Engineering (CSDE), Nadi, Fiji, 4–6 December 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shoaib, M.; Sadeghi-Niaraki, A.; Ali, F.; Hussain, I.; Khalid, S. Leveraging deep learning for plant disease and pest detection: A comprehensive review and future directions. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1538163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Xu, D.; Liang, H.; Bai, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Su, C.; Wei, W. Advances in deep learning applications for plant disease and pest detection: A review. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokhande, N.; Thool, V.; Vikhe, P. Comparative analysis of different plant leaf disease classification and detection using CNN. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Recent Innovation in Smart and Sustainable Technology (ICRISST), Bengaluru, India, 15–16 March 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Nwaneto, C.B.; Yinka-Banjo, C. Harnessing deep learning algorithms for early plant disease detection: A comparative study and evaluation between SSD (Mobilenet_v2 and Mobilenet_v3) and CNN model. Ife J. Sci. 2024, 26, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, B.; Haque, M.M.U.; Khatun, R.; Ahmed, R. Comparative performance of four CNN-based deep learning variants in detecting Hispa pest, two fungal diseases, and NPK deficiency symptoms of rice (Oryza sativa). Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 202, 107340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhani, S. A Review Comparative Mamography Image Analysis on Modified CNN Deep Learning Method. Indones. J. Artif. Intell. Data Min. 2021, 4, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- El Sakka, M.; Ivanovici, M.; Chaari, L.; Mothe, J. A review of CNN applications in smart agriculture using multimodal data. Sensors 2025, 25, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasra, P.; Gupta, S. CNN and ResNet50 Performance Comparison for Maize Leaf Disease Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference for Advancement in Technology (ICONAT), GOA, India, 6–8 September 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xuan, X.; Zhang, X.; Kwon, O.H.; Ma, K.L. VAC-CNN: A visual analytics system for comparative studies of deep convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2022, 28, 2326–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, M.H.; Potgieter, J.; Arif, K.M. Plant disease classification: A comparative evaluation of convolutional neural networks and deep learning optimizers. Plants 2020, 9, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).