Abstract

Stress, being an inherent trait, is a major driver of farm animal disease, leading to significant antimicrobial use (AMU). AMU is the recognized source of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Among other ways, AMR spread can be controlled by selective breeding. To address this, stress susceptibility among daughters (gilts) of stressed mothers (sows) is tracked using AI and computer vision techniques. A deep learning-based model is trained and validated on the ground truth labels (through behaviour testing during recording of the videos) of stress susceptibility (SS) of mothers (sows). Then, this trained model is employed as a feature extractor for clustering techniques, such as K-means, Agglomerative, etc. This leads to the conclusion that more than 90% of stress-susceptible (SS) mothers had SS daughters. This result is crucial, as it can ease the process of selective breeding, where low stress-susceptible (LS) mothers could further be used for the breeding of the new generation.

1. Introduction

As with humans, a proneness to stress seems to adversely alter the vulnerability of animals to infectious agents [1]. In the case of piglets, stress susceptible animals often suffer from an increased incidence of post-weaning diarrhoea (PWD), resulting in death or longer-term growth retardation [2]. PWD alone represents a serious threat to the pig industry worldwide [3] and usually requires treatment with antibiotics, the overuse of which presents a significant threat to human health via risk of increased antimicrobial resistance. In general terms, animals with low stress susceptibility tend to possess a stronger immune system, to be healthier, and so have a reduced need for medication [4] Furthermore, stress resilient pigs exhibit higher feed efficiency, potentially helping to lower the overall environmental impact of pig farming [5]. For these reasons there is ongoing interest in finding better ways to monitor for stress in pigs. Understanding and recognising emotion in pigs has become a developing area of interest, recently accelerated by new work utilising AI techniques [6,7]. Here we consider inherited emotional traits with a particular emphasis on susceptibility to stress, and the role of automated stress detection for exploring inheritability in the context of breeding for stress resistance in pigs. It has been known for some time that pigs with an inherited condition known as porcine stress syndrome tend to exhibit higher mortality rates and poorer meat quality [8] and maternal stress in pigs during gestation is known to impair growth, immune function and, it is thought, the behaviour and stress reactivity of offspring [9]. Bernardino et al. [10] suggest that pregnant sows subject to reduced hunger tend to produce offspring with reduced agonistic behaviour, while Braastad [11] points to evidence that prenatal stress can impair stress-coping ability in offspring in laboratory and farmed animals. Rutherford et al. found that prenatal stress can produce anxiety prone female offspring [12], and Sabei, et al. [13] have shown how boar housing conditions can affect the stress response and emotionality (anxiety, fear, and exploration) of their offspring. However, while there has been a significant body of work exploring how experiential exposure of parents may influence subsequent emotional traits in their offspring and that resistance or non-resistance to stress may persist throughout an individual animal’s life [14,15], any correlation in terms of maternal (or paternal) behaviour in female offspring used as breeding animals across multiple generations remains unclear. What is clear, is that many inherited traits play crucial roles in pig breeding programs along with economic value determination, and collectively such findings appear to indicate a possible genetic basis for transfer of stress susceptibility in pigs, carrying significant consequences for both animal welfare and the quality and economics of meat production. Less well explored is whether existing characteristic parental emotional traits per se, such as parental stress susceptibility, are passed to offspring, including over multiple generations. Understanding the role of parental stress susceptibility and any relationship with offspring behaviour and their emotionality could help in our understanding of the degree of inheritability of emotional traits and in developing valuable new tools for evaluating and managing cross-generational stress resilience. Hence, the specific question we seek to address here is in essence, do stress susceptible parents tend to have similarly stress susceptible offspring, and vice versa, do stress susceptible piglets tend to have one or more stress susceptible parents? Recognising emotion in pigs usually involves careful observation of various behavioural and/or physiological indicators that reflect differing emotional states. Established behavioural indicators include body language, such as body pose, tail and ear positions, aspects of facial expression (often encoded as facial action units) [16], vocalisations [17] and activity level or social interactions, such as in the case of aggression or play activities [18]. Physiological indicators include heart or respiration rate, level of cortisol, and body temperature [19,20]. While in the past these indicators were often manually recorded, with their roots in the discipline of ethology, more recently machine vision and learning techniques have been deployed. Prior work [7] has shown that AI recognisable phenotypes in terms of animal appearance and behavioural traits are associated with, and may be used to detect, stress susceptibility in pigs. Identifying such traits together with understanding their level of inheritability could be used as a valuable tool in breeding selection programs to help improve the welfare and productivity of future generations of farmed pigs, with associated societal benefits, including reduced use of antibiotics and environmental pollution. This work builds on the research above and proposes an AI algorithm to track stress susceptibility from mothers (sows) to daughters (gilts) in a semi-supervised manner. First, a deep learning-based model is trained on mothers. This model is employed as a feature extractor. The extracted features are reduced and clustered into distinct classes: low stress (LS) and stress susceptible (SS). This work is possible due to a year-long dataset collection, where the partnering institute records mothers on different days during and after pregnancy. The daughters were recorded during their gilt stage.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents an overview of the materials and methods. Section 3 details the experimental results, including quantitative and qualitative analyses. Finally, Section 4 concludes with a summary of the main findings and future research directions.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Dataset Recording Setup

The proposed system integrates a camera set-up within a Pig farm in the UK to capture high-quality images of pigs (mothers and daughters) as shown in Figure 1. Similarly, a few examples of the images collected are shown in the Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Dataset recording setup.

Figure 2.

A typical example of images acquired.

Imaging Technology and Specifications:

- Camera Type: High-resolution industrial cameras optimized for low-light conditions.

- Resolution: 4K resolution to capture fine details of animal face.

- Lighting Conditions: LED lighting ensures uniform illumination to mitigate shadows and enhance image clarity.

- Placement: Cameras are placed in strategic locations/angles within the dry sow house, which is where sows are housed in individual straw pens equipped with their feed stalls and dunging passages.

2.2. Data Collection and Dataset Construction

The dataset included:

- Number of Animals: 23 mothers and 97 daughters monitored over one year.

- Total Images Captured: Approximately six terabytes of data was captured as videos for analysis.

Recording Description:

The mothers and daughters were recorded while undergoing different tests (as described below), which are proven to induce stress susceptibility:

- Dominance test: Pregnant pigs (Mothers) are recorded on day 70 and day 90 of their pregnancy. This test is designed to provide a challenge during pregnancy and determines individual responses to a competitive test of dominance.

- Moving to farrowing crates (at Day 110): Approximately five days before the mothers are due to give birth they are moved from group-housing in straw bedded pens to single housing in farrowing crates. Farrowing crates are known to cause stress as they are restrictive maternity systems that prevent the pigs from turning around.

- In farrowing crate for +24 h: Images are captured after the pigs have experienced 24 h in the farrowing crate.

- Offspring handled (Day 0): Mothers are recorded after they have given birth, when their offspring are being handled. Mothers are expected to show different responses to their piglets being handled by staff during husbandry procedures performed on piglets shortly after birth.

- Offspring handled (Day 3 Iron): Mothers are recorded 3 days after they have given birth, when their offspring are being given their iron injection

- Attention Bias Test (ABT): This test is designed for the daughters after 125 days post birth. All daughters are expected to be startled by the test but respond differently when being challenged to return to the area where the startle took place in order to receive a food reward.

2.3. Dataset Preprocessing

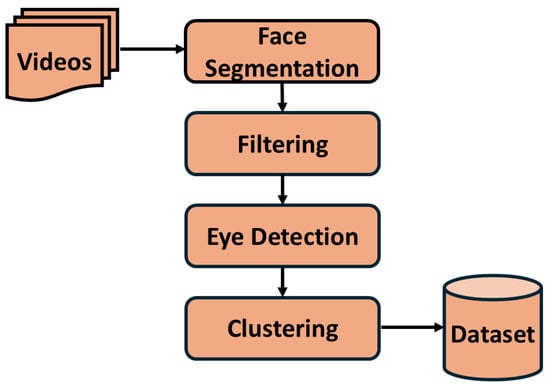

The videos recorded on mothers (sows) and their daughters (gilts) go through a rigorous preprocessing, as shown in Figure 3. The process includes segmenting faces of animals in the images using the YOLOv9 segmenter [21]. The confidence threshold is kept high, i.e., 0.9, to extract only the best-quality face segmentations. This further goes through another filtering process based on the distance of the animal from the camera. For this, we employ the aspect ratio of the segmented face to the original image size. If the aspect ratio is more than 0.4, then the segmented face is sent to the next processing step. As mentioned before, eyes are one of the important features for stress. Thus, the segmented faces go through a YOLOv5-based eye detector [21]. The images with both eyes visible are kept for the final preprocessing step. Finally, clustering is performed on the set of images to pick distinct images with different orientations. A pre-trained VGG-16 [22], without the final classification layer, is used to extract the features, which are clustered using the k-means algorithm. In this, we use a maximum of 50 clusters, which means one image per cluster would be saved in the final dataset. This preprocessing is completed for 23 mothers and 97 daughters and yields a dataset of approximately 40,000 images.

Figure 3.

Dataset Preprocessing.

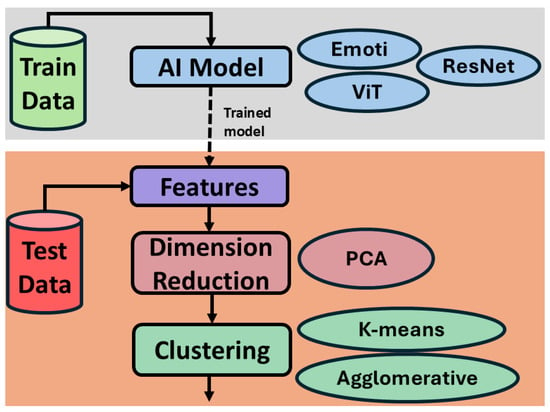

2.4. System Overview

The proposed system works in a semi-supervised manner as shown in Figure 4. First, a supervised stress susceptibility classifier is trained on the data of the mothers (sows) with labels low stress (LS) and stress susceptible (SS). The trained model is validated on the unseen mothers (sows). Here, we chose three different AI/deep learning models namely Emoti [7], Residual Network (ResNet-50) [23], and Vision Transformer (ViT) [24]. This choice helps to explore three different types such as a shallow CNN (Emoti), a deep CNN (ResNet-50), and a transformer-based (ViT) model.

Figure 4.

System Overview.

Next comes clustering based unsupervised stress suceptibility classifier. The trained models are used as feature extractor. The features are extracted from last convolutional layers of each model. Given that this feature vector is high-dimensional, a famous dimensionality reduction algorithm called Principle Component Analysis (PCA) [25] is used. The reduced vector is then used for the clustering into two distinct clusters namely LS and SS. This paper explores two different clustering techniques namely K-means [26] and Agglomerative [27] to benchmark the results.

2.5. Training Procedure

To facilitate model training and validation, the dataset was partitioned into distinct subsets, allocating 70% of mother’s data for training and reserving the remaining 30% for validation purposes. However, this 30% validation subset was unseen altogether, i.e., it belong to different mothers. The test set (daughters) is used for unsupervised clustering.

The training process was conducted with images resized to dimensions of 212 × 212 pixels. A batch size of 32 samples was employed, coupled with a learning rate of 0.0001 and the Adam optimizer. The training process spanned 500 epochs, requiring approximately 23.4 h to complete for the three models. It’s noteworthy that this experimental setup aligns closely with the recommended guidelines provided by pytorch framework 2.9.1 [22].

2.6. Hardware Configuration

The proposed algorithm was trained on a Windows 11 PC equipped with high-performance hardware components. The system comprises a Core i9 processor clocked at 3 GHz, accompanied by 32 GB of RAM, and is augmented with a potent 24 GB Nvidia RTX 4090 graphics processing unit (GPU). The implementation and training of the algorithm were executed using the PyTorch framework [22], leveraging the extensive functionalities provided by the Ultralytics codebase [21].

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

The performance of the proposed algorithm is rigorously assessed using fundamental evaluation metrics such as the precision P, recall R, and F-score F. These metrics offer invaluable insights into the algorithm’s classification capabilities, enabling a comprehensive understanding of its efficacy.

Table 1 presents the clustering performance using PCA-reduced feature representations extracted from three deep learning models: Emoti, ResNet, and ViT (Vision Transformer). Two clustering methods, K-means and Agglomerative Clustering, are applied to the reduced features, and performance is reported in terms of Precision (P), Recall (R), and F-score (F) for two classes labeled here as LS (low stressed) and SS (stress susceptible). An average across these two classes is also provided.

Table 1.

Comparison of clustering performance (Precision P, Recall R, and F-score F) using PCA-reduced features from Emoti, ResNet, and ViT models. Two clustering algorithms, K-means and Agglomerative Clustering, were applied, and results are reported per class (LS and SS) as well as averaged. LS and SS refer to low stress and stress susceptible categories.

ViT consistently outperforms the other models across both clustering algorithms. Notably, with Agglomerative Clustering, it achieves an average F-score of 0.94, the highest among all configurations. This suggests that ViT captures highly discriminative features for stress susceptibility even after dimensionality reduction. ResNet also performs strongly, especially with K-means, achieving an average F-score of 0.844, indicating robust feature separability. However, performance fluctuates when using Agglomerative Clustering possibly due to sensitivity to hierarchical structure assumptions. Emoti, a lightweight model, shows relatively weaker performance, especially in comparison to ViT. Its best configuration (PCA + Agglomerative) yields an average F-score of 0.809, still competitive, but not on par with deeper architectures.

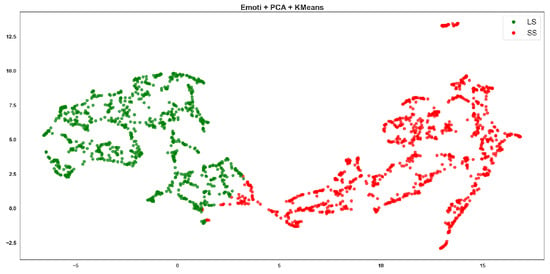

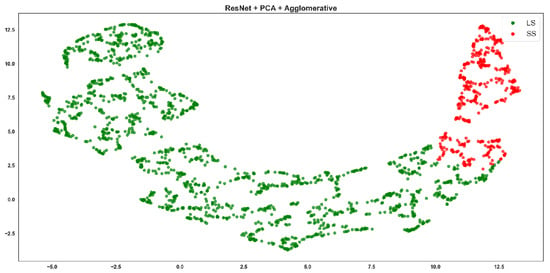

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

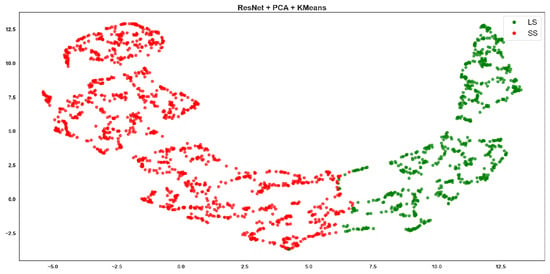

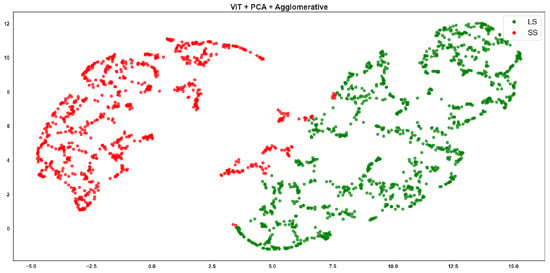

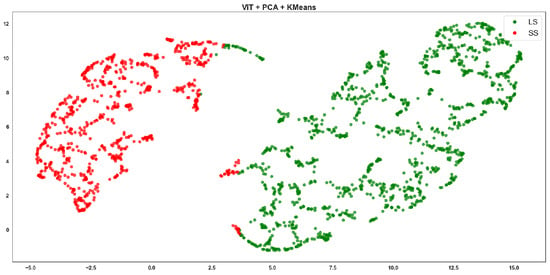

The performance metrics reported in the Table 1 could be visually justified by the Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10. The best performance (ViT + PCA + Agglomerative) in the table corresponds to the most visually distinct clusters in the Figure 9. K-means works better with ResNet than Agglomerative, as seen in both visual clarity and table metrics. Emoti generally underperforms, which is evident in both cluster mixing and lower F-scores.

Figure 5.

Emoti + PCA + Agglomerative clustering, where red points correspond to the SS class and green points to the LS class.

Figure 6.

Emoti + PCA + K-means clustering, where red points correspond to the SS class and green points to the LS class.

Figure 7.

Resnet + PCA + Agglomerative clustering, where red points correspond to the SS class and green points to the LS class.

Figure 8.

Resnet + PCA + K-means clustering, where red points correspond to the SS class and green points to the LS class.

Figure 9.

ViT + PCA + Agglomerative clustering, where red points correspond to the SS class and green points to the LS class.

Figure 10.

ViT + PCA + K-means clustering, where red points correspond to the SS class and green points to the LS class.

Emoti-based features showed moderate clustering quality, with visible overlap between the red (SS) and green (LS) clusters (Figure 5 and Figure 6). ResNet-based Agglomerative clusters (Figure 7) are quite imbalanced: the green class (LS) dominates visually with tight cohesion, while red points (SS) are scattered and poorly grouped. This reflects the Recall of 0.513 for SS in the table, meaning the method retrieves few SS instances correctly. The F-score drops to 0.752, confirming inconsistency. However, ResNet-based K-means clusters (Figure 8) are more symmetrical and better separated, with cleaner boundaries.

ViT-based Agglomerative shows excellent cluster separation (Figure 9). The green and red points form two well-separated, dense clusters with almost no mixing. This aligns perfectly with the highest F-score of 0.94 in the table. ViT’s strong feature representation and the structure-sensitive nature of Agglomerative clustering combine effectively. ViT-based K-means clustering (Figure 10) is clean with minimal overlap, although the boundaries are slightly less compact than Agglomerative. Still, ViT maintains high performance, and this reflects the F-score of 0.902, just slightly below (Figure 9).

4. Conclusions

This paper proposes a semi-supervised AI algorithm to track the susceptibility to stress in daughters (gilts) due to the inherent traits of their mothers (sows). The work is supported by quantitative and qualitative analysis. The proposed algorithm was able to track stress susceptibility in daughters with a more than 90% F-score. This is a promising prospect. In the future works, the authors would like to track stress susceptibility in the daughters while they go through pregnancy. Furthermore, the work could be further strengthened with different dimensionality reductions and clustering algorithms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.U.Y., A.S., E.M.B., M.F.H., M.L.S. and L.N.S.; Methodology, S.U.Y. and A.S.; Software, S.U.Y., A.S. and M.F.H.; Validation, S.U.Y., A.S., E.M.B. and M.F.H.; Formal analysis, S.U.Y., A.S., E.M.B. and M.F.H.; Investigation, S.U.Y. and A.S.; Resources, S.U.Y. and E.M.B.; Data curation, S.U.Y. and E.M.B.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.U.Y.; Writing—review and editing, S.U.Y., A.S., E.M.B., M.F.H., M.L.S. and L.N.S.; Visualization, S.U.Y., A.S., E.M.B. and M.F.H.; Supervision, S.U.Y., A.S. and M.F.H.; Project administration, S.U.Y., A.S., E.M.B., M.F.H. and M.L.S.; Funding acquisition, M.L.S. and L.N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Joint Programming Initiative on Antimicrobial Resistance (JPIAMR) under the FARM-CARE project, ‘FARM interventions to Control Antimicrobial ResistancE–Full Stage’ (Project ID: 7429446), and by the Medical Research Council (MRC), UK (Grant Number: MR/W031264/1).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study underwent internal ethical review by both SRUC’s and UWE Bristol’s Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Bodies (ED AE 16-2019 and R101) and was carried out under the UK Home Office license (P3850A80D).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Joint Programming Initiative on Antimicrobial Resistance (JPIAMR) and the Medical Research Council (MRC), UK. We also thank the collaborative partners of the FARM-CARE project: University of the West of England, Scotland’s Rural College, University of Copenhagen, Teagasc, University Hospital Bonn, Statens Serum Institut (SSI), and Porkcolombia Association. We are especially thankful to the farm and technical staff at SRUC’s Pig Research Centre for their invaluable support in data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Biondi, M.; Zannino, L.G. Psychological stress, neuroimmunomodulation, and susceptibility to infectious diseases in animals and man: A review. Psychother. Psychosom. 1997, 66, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Xiong, K.; Fang, R.; Li, M. Weaning stress and intestinal health of piglets: A review. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1042778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhouma, M.; Fairbrother, J.M.; Beaudry, F.; Letellier, A. Post weaning diarrhea in pigs: Risk factors and non-colistin-based control strategies. Acta Vet. Scand. 2017, 59, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghof, T.V.L.; Bovenhuis, H.; Mulder, H.A. Body weight deviations as indicator for resilience in layer chickens. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homma, C.; Hirose, K.; Ito, T.; Kamikawa, M.; Toma, S.; Nikaido, S.; Satoh, M.; Uemoto, Y. Estimation of genetic parameter for feed efficiency and resilience traits in three pig breeds. Animal 2021, 15, 100384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S. AI in sustainable pig farming: IoT insights into stress and gait. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.F.; Baxter, E.M.; Rutherford, K.M.D.; Futro, A.; Smith, M.L.; Smith, L.N. Towards facial expression recognition for on-farm welfare assessment in pigs. Agriculture 2021, 11, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabry, J.W.; Christian, L.L.; Kuhlers, D.L. Inheritance of porcine stress syndrome. J. Hered. 1981, 72, 429–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otten, W.; Kanitz, E.; Tuchscherer, M. The impact of pre-natal stress on offspring development in pigs. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 153, 907–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagoda, M.E.; O’Driscoll, K.; Galli, M.C.; Cerón, J.J.; Ortín-Bustillo, A.; Marchewka, J.; Boyle, L.A. Indicators of improved gestation housing of sows. Part II: Effects on physiological measures, reproductive performance and health of the offspring. Anim. Welf. 2023, 32, e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardino, T.; Tatemoto, P.; Morrone, B.; Rodrigues, P.H.M.; Zanella, A.J. Piglets born from sows fed high fibre diets during pregnancy are less aggressive prior to weaning. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C.E.; Jozet-Alves, C.; Mezrai, N.; Bellanger, C.; Darmaillacq, A.-S.; Dickel, L. Maternal and embryonic stress influence offspring behavior in the cuttlefish Sepia officinalis. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, K.M.D.; Piastowska-Ciesielska, A.; Donald, R.D.; Robson, S.K.; Ison, S.H.; Jarvis, S.; Brunton, P.J.; Russell, J.A.; Lawrence, A.B. Prenatal stress produces anxiety prone female offspring and impaired maternal behaviour in the domestic pig. Physiol. Behav. 2014, 129, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabei, L.; Parada Sarmiento, M.; Bernardino, T.; Çakmakçı, C.; Farias, S.d.S.; Sato, D.; Zanella, M.I.G.; Poletto, R.; Zanella, A.J. Inheriting the sins of their fathers: Boar life experiences can shape the emotional responses of their offspring. Front. Anim. Sci. 2023, 4, 1208768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, W.G.; Wiegant, V.M. Individual responses to acute and chronic stress in pigs. Acta Physiol. Scand. Suppl. 1997, 640, 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, B.; Karlen, G.M.; Morrison, R.; Gonyou, H.W.; Butler, K.L.; Kerswell, K.J.; Hemsworth, P.H. The behaviour of pigs in response to social stress. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 165, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lezama-García, K.; Orihuela, A.; Olmos-Hernández, A.; Reyes-Long, S.; Mota-Rojas, D. Facial expressions and emotions in domestic animals. CAB Rev. 2019, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.; Wondrak, M.; Huber, L.; Fitch, W.T. Honest signaling in domestic piglets (Sus scrofa domesticus): Vocal allometry and the information content of grunt calls. J. Exp. Biol. 2016, 219, 1913–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weller, J.E.; Camerlink, I.; Turner, S.P.; Farish, M.; Arnott, G. Socialisation and its effect on play behaviour and aggression in the domestic pig (Sus scrofa). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leliveld, L.M.C.; Düpjan, S.; Tuchscherer, A.; Puppe, B. Vocal correlates of emotional reactivity within and across contexts in domestic pigs (Sus scrofa). Physiol. Behav. 2017, 181, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Stoken, A.; Borovec, J.; NanoCode012; Kwon, Y.; Michael, K.; TaoXie; Fang, J.; Imyhxy; et al. ultralytics/yolov5: V7.0-YOLOv5 SOTA Realtime Instance Segmentation; Technical Report, Ultrlytics; Zonodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.01703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal Component Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, S.P. Least Squares Quantization in PCM. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1982, 28, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müllner, D. Modern hierarchical, agglomerative clustering algorithms. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1109.2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).