Abstract

This study examines volatility transmission between major European indices (CAC 40, DAX, FTSE MIB, IBEX 35, EURO STOXX 50) and Tunisia’s TUNINDEX amid global crises (2008 financial crisis, COVID-19, Russo-Ukrainian war). Using GARCH(1,1) and BEKK models, the analysis reveals low correlation and weak volatility spillovers between the TUNINDEX and European markets, indicating relative decoupling. ARCH-LM tests confirm conditional heteroskedasticity, while GARCH models show persistent volatility. The BEKK model underscores marginal shock transmission, affirming the TUNINDEX’s independence. These findings suggest diversification benefits for investors but highlight local risk considerations. Practical recommendations are provided for stakeholders, with future research directions including asymmetric effects and high-frequency data analysis.

1. Introduction

The introduction of Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (GARCH) models by [1] revolutionized financial econometrics, extending Engle’s ARCH framework to better capture volatility clustering, a phenomenon where financial market turbulence persists before gradually stabilizing. Since then, GARCH models have evolved into a versatile family of econometric tools, each addressing distinct limitations of the original specification. For instance, Ref. [2] introduced an exponential form to model asymmetric volatility responses—EGARCH—while the GJR-GARCH [3] explicitly differentiated between market reactions to positive and negative shocks. Periodic GARCH [4] further enhanced volatility modeling by incorporating cyclical patterns, reflecting the time-dependent nature of financial markets.

Recent advancements have expanded GARCH models to accommodate increasingly complex market behaviors. Ref. [5]’s GARCH-X model, for example, incorporated realized volatility as an exogenous variable, effectively bridging high-frequency data with traditional time-series analysis. This innovation proved particularly valuable in commodity markets, where [6] demonstrated that long-memory models—such as FIGARCH, FSV, and HAR—outperformed standard GARCH in capturing volatility dynamics across 22 commodities. Their findings revealed key structural differences, such as weekly volatility patterns dominating most markets, while oil and gold exhibited stronger daily cycles. Additionally, they observed persistent antipersistence—a counterintuitive volatility decay pattern—across all commodities, offering critical insights for traders and risk managers.

Beyond single-market analysis, GARCH models have become instrumental in studying cross-market volatility transmission and financial contagion. Ref. [7] employed the BEKK-GARCH framework to analyze emerging Asian markets during the global financial crisis, confirming volatility spillovers from developed to emerging economies. Similarly, Ref. [8] used Markov-Switching GARCH (MS-GARCH) to uncover bidirectional volatility linkages between African equity and foreign exchange markets. These studies highlight how GARCH-based models can trace shock propagation across borders and asset classes, providing policymakers and investors with crucial risk assessment tools.

The applications of GARCH models continue to diversify, extending into unconventional financial domains. Ref. [9] explored the influence of social factors including Google search trends on eSports ETF performance, demonstrating that investor sentiment could be as impactful as financial indicators, while Ref. [10] developed novel option pricing models using Threshold GARCH (TGARCH), improving volatility forecasts for derivatives markets. Methodological innovations, such as Ref. [11] quantile GARCH-MIDAS, have further refined risk analysis by linking oil market volatility to economic policy uncertainty. These developments underscore the adaptability of GARCH frameworks in addressing an ever-broadening spectrum of financial research questions.

As financial markets grow more interconnected and complex, GARCH models remain indispensable for volatility forecasting, risk management, and asset pricing. Their ability to capture non-linear dynamics, time-varying volatility, and cross-market dependencies ensures their continued relevance. Looking ahead, the integration of machine learning techniques with traditional GARCH frameworks promises to enhance predictive accuracy while preserving interpretability—a critical balance for both academics and practitioners. This synergy between classical econometrics and cutting-edge computational methods is poised to unlock new insights into market microstructure, behavioral finance, and systemic risk, reinforcing GARCH models as a cornerstone of financial econometrics in the years to come.

2. The Evolution and Expanding Applications of GARCH Models in Financial Econometrics

Ref. [1]’s (1986) GARCH model revolutionized volatility modeling by extending Engle’s ARCH framework to better capture volatility clustering in financial markets. This breakthrough led to numerous extensions addressing specific market behaviors: EGARCH [2] modeled asymmetric volatility responses, GJR-GARCH [3] differentiated between positive and negative shocks, and Periodic GARCH [4] incorporated cyclical volatility patterns.

Recent innovations have enhanced GARCH’s applicability. Ref. [5]’s GARCH-X integrated high-frequency data, while Ref. [6] showed that long-memory models (FIGARCH, FSV, HAR) better capture commodity volatility dynamics, revealing distinct weekly patterns in most markets versus daily cycles in oil and gold. These insights are crucial for risk management in commodity trading.

GARCH models also excel in cross-market analysis. Studies like Ref. [7], using BEKK-GARCH, and Ref. [8], with MS-GARCH, demonstrated volatility spillovers between developed and emerging markets, as well as bidirectional linkages between African equities and FX markets. Similarly, asymmetric GARCH models have proven effective in single-market studies, such as Nasdaq-100 volatility analysis [12].

Modern applications continue to expand, from social media’s impact on eSports ETFs [9] to improved options pricing via TGARCH [10]. Methodological advances like quantile GARCH-MIDAS [11] further enhance risk assessment capabilities.

As markets grow more complex, GARCH models remain essential for volatility forecasting and risk management. Future integration with machine learning promises to strengthen predictive power while preserving interpretability, ensuring GARCH’s continued relevance in financial research and practice.

3. Sample and Stock Index Presentation

Our study analyzes volatility transmission between five major European stock indices and Tunisia’s TUNINDEX using monthly data from January 2000 to January 2025, a period encompassing several major economic shocks including the 2008 financial crisis, European debt crisis (2010–2012), political instability (2011–2012), COVID-19 pandemic (2020), and Russia–Ukraine war impacts (2022 onward). These events created significant market turbulence, influencing cross-market volatility transmission patterns with potential asymmetric shock effects. The selected benchmark indices represent key European economies and Tunisia’s emerging market: TUNINDEX (Tunisia’s main index tracking largest listed companies), CAC 40 (France’s blue-chip index of 40 major Paris-listed firms), DAX (Germany’s premier index of 40 Frankfurt-listed corporations), IBEX 35 (Spain’s benchmark of 35 Madrid-listed stocks), FTSE MIB (Italy’s primary index of 40 Milan-listed companies), and EURO STOXX 50 (pan-European index of 50 Eurozone blue chips). These indices serve as vital economic health indicators, reflecting corporate performance, macroeconomic conditions (GDP, inflation, unemployment), policy decisions, and geopolitical developments, while providing investors with critical market sentiment gauges. The TUNINDEX’s inclusion enables examination of volatility spillovers between an emerging North African market and developed European economies, particularly valuable given Tunisia’s relative financial decoupling and distinct local risk factors that may offer portfolio diversification benefits despite lower integration with European markets.

4. Econometric Methodology

Our econometric methodology is structured into four distinct phases, each designed to analyze and model stock return volatility. The approach begins with preliminary data exploration before advancing to sophisticated volatility-modeling techniques.

4.1. Preliminary Data Analysis

We first conduct a visual inspection of the time series for all stock indices through graphical analysis. This step helps identify volatility clustering—periods where market fluctuations intensify persistently—while also revealing non-linear patterns and structural breaks in the data. The visual examination provides initial insights into the volatility characteristics of each market.

Subsequently, we perform descriptive statistical analysis to examine key properties of the return series, including

- -

- Mean and standard deviation to measure central tendency and dispersion;

- -

- Skewness to assess distribution symmetry;

- -

- Kurtosis to identify fat-tailed distributions (leptokurtic when kurtosis > 3).

These metrics help detect anomalies and structural patterns. We complement this with the Jarque–Bera test to evaluate normality assumptions. The frequent presence of leptokurtic and asymmetric distributions in financial data justifies our use of robust volatility models rather than standard normal distribution approaches.

4.2. Correlation Analysis

To examine relationships between indices, we employ both

- -

- Pearson’s parametric test for linear relationships;

- -

- Spearman’s non-parametric test for monotonic non-linear relationships.

This dual approach allows us to achieve the following:

Identify non-linear dependencies between indices;

Rank indices by their degree of comovement;

Detect market contagion or decoupling phenomena.

The correlation analysis provides a comparative measure of index movements and helps classify their interrelationships.

4.3. ARCH Effects Testing

The third phase involves testing for ARCH (Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity) effects using the ARCH-LM test. Rejection of the null hypothesis (no ARCH effects) indicates the presence of conditional heteroskedasticity, validating the use of GARCH-family models for volatility modeling.

4.4. Volatility-Modeling Framework

We employ the GARCH(1,1) model (Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity) introduced by [1] to measure volatility magnitude in selected indices. This model effectively captures volatility clustering through its dual-component structure:

The mean equation is

where represents returns at time , is the mean return, and is the error term.

The variance equation is

where is conditional variance, is a constant, captures the impact of past shocks (squared residuals), and measures volatility persistence

The coefficient reflects how recent shocks affect current volatility, while indicates long-term volatility persistence.

4.5. Advanced Multivariate Analysis

For studying volatility transmission between markets, we implement the Baba–Engle–Kraft–Kroner BEKK) parameterization proposed by [13]. The BEKK model offers several advantages:

It guarantees positive definiteness of the conditional covariance matrix by construction.

It captures volatility spillovers between markets.

It allows analysis of how shocks propagate across markets over time.

where is the conditional covariance matrix, is a lower triangular matrix, and and are coefficient matrices measuring shock transmission and volatility persistence, respectively.

4.6. Model Implementation

To examine volatility transmission between European partner indices and the TUNINDEX, we specify systems where

This comprehensive methodology allows us to not only model volatility dynamics within each market, but also to quantify and analyze the transmission mechanisms between the Tunisian market and its European counterparts, providing valuable insights for both academic understanding and practical investment applications.

5. Results and Discussion

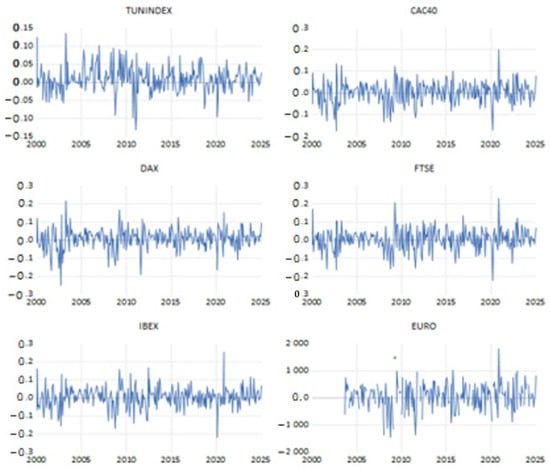

Figure 1 displays the returns of stock market indices (TUNINDEX, CAC40, DAX, FTSE, IBEX, and EURO), revealing a volatility clustering phenomenon. This pattern indicates that periods of high volatility tend to be followed by further significant fluctuations, while periods of low volatility also persist consecutively. Large price movements cluster together, as do smaller ones, reflecting the temporal persistence of market fluctuations. Markets react in this manner to external shocks and investor behavior. This phenomenon is crucial for forecasting future volatility and risk management, as it helps optimize portfolios by anticipating extreme movements.

Figure 1.

Stock index returns.

The observed volatility clustering confirms the heteroskedastic nature of financial markets, where volatility exhibits serial correlation—meaning current volatility is influenced by past volatility shocks. This occurs because markets process information gradually rather than instantaneously, responding progressively to economic news, geopolitical events, and investor sentiment (such as herding behavior or overreactions). The Tunisian market shows particularly strong volatility persistence compared to more developed European markets, suggesting differences in market efficiency and liquidity depth that affect how quickly shocks are absorbed. These findings validate the use of GARCH-family models for volatility forecasting while highlighting the need for dynamic risk management approaches tailored to different market conditions.

The descriptive statistics presented in Table 1 reveal key characteristics for volatility modeling. The DAX and IBEX 35 exhibit high volatility levels, with standard deviations of 0.051 and 0.054, respectively, while the Tunindex shows the lowest volatility at 0.033. The return distributions display significant asymmetry—negative skewness for DAX (-0.395) versus positive skewness for IBEX 35 (+0.227). The elevated kurtosis values confirm fat-tailed distributions, strongly justifying the use of GARCH models. Jarque–Bera test results conclusively reject the normality assumption for all series.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

These findings support the implementation of GARCH(1,1) modeling, though requiring index-specific adjustments in the conditional variance equations. The preliminary analysis directly informs the appropriate specification of volatility dynamics for each market. The observed cross-index variations necessitate customized modeling approaches to better predict volatility clusters. These distinct statistical properties enable optimized risk management strategies through alternative distributional assumptions. The results ultimately highlight the critical need for tailored volatility-modeling frameworksthat account for each index’s unique characteristics, particularly when developing forecasting systems or hedging strategies across these heterogeneous markets.

Table 2 reveals that both Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients between TUNINDEX and European indices (CAC 40, DAX, FTSE MIB, IBEX 35, EURO STOXX 50) are all close to zero, indicating no significant linear or monotonic relationship. For investors, this negligible correlation presents valuable portfolio diversification opportunities.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix.

The next analytical step involves testing for ARCH effects using the ARCH-LM heteroskedasticity test to determine whether GARCH models are appropriate for modeling stock return volatility.

The results in Table 3 show that four indices—TUNINDEX, CAC 40, DAX, and EURO STOXX 50—exhibit statistically significant ARCH effects, leading to rejection of the null hypothesis of homoskedasticity in favor of conditional heteroskedasticity. These indices demonstrate variance conditional on past shocks, justifying the use of GARCH models to capture their volatility dynamics. Conversely, the FTSE MIB and IBEX 35 show no significant ARCH effects (non-significant F-statistics), indicating no conditional heteroskedasticity.

Table 3.

ARCH-LM Test Results.

The GARCH(1,1) estimation results presented in Table 4 for the TUNINDEX, CAC 40, DAX, and EURO STOXX 50 indices reveal several key findings about their volatility dynamics. The mean equation shows statistically significant returns for the TUNINDEX (0.0075 at 1% significance), CAC 40 (0.0068 at 5%), and DAX (0.0100 at 1%), while the EURO STOXX 50 displays anomalous values that require verification. Regarding conditional variance, the constant term ω is significant for all indices, though the EURO STOXX 50 shows abnormally high estimates. The ARCH parameter α, representing recent shock impacts, is significant at 10% for TUNINDEX (0.1161) and 1% for CAC 40 (0.223) and DAX (0.2135). The GARCH parameter β, reflecting volatility persistence, is highly significant (1% level) across all indices, with particularly strong values for DAX (0.6637) and TUNINDEX (0.645), indicating substantial volatility memory effects.

Table 4.

GARCH(1,1) Estimation Results.

These results demonstrate that all examined indices exhibit significant volatility clustering, with the GARCH(1,1) model proving particularly effective at capturing both immediate market reactions to shocks (through α) and long-term persistence patterns (through β). The high β values, especially for DAX and TUNINDEX, suggest that volatility shocks have prolonged effects on future variance forecasts, making the GARCH framework superior to basic ARCH specifications for these markets. The differential sensitivity to recent shocks (α) and varying persistence levels (β) across indices highlight the need for market-specific volatility-modeling approaches. While the TUNINDEX shows intermediate persistence, the DAX’s stronger memory effect implies longer-lasting volatility impacts, crucial information for risk managers and portfolio strategists. The anomalous EURO STOXX 50 results, however, indicate potential data issues that warrant further investigation. Overall, Table 4’s findings validate the GARCH(1,1) model’s effectiveness for volatility forecasting in these markets, particularly during periods of market stress when both immediate reactions and persistent volatility patterns need to be accounted for in risk assessments and derivative pricing.

Finally, the focus will be on estimating the BEKK system for the four stock indices. The system is represented as follows:

Table 5 presents the estimation results of the BEKK-GARCH model analyzing interactions between TUNINDEX (Tunisian stock index) and three European indices: CAC 40 (France), DAX (Germany), and EURO STOXX 50 (Eurozone). These results highlight volatility dynamics and shock transmissions between these markets, providing important financial and economic insights.

Table 5.

Parameter estimation results of the BEKK-GARCH equation system.

Recent shock impacts (aii):

For CAC 40 (0.003) and DAX (-0.033), the coefficients are not statistically significant, indicating that recent shocks in these markets do not significantly affect their own volatility. This suggests relative short-term stability against recent disturbances.In contrast, for EURO STOXX 50 (0.230), the coefficient is significant at 1%, revealing that recent shocks strongly influence its volatility, reflecting greater sensitivity of this pan-European index to immediate economic or financial events.

Volatility persistence (bjj):

The coefficients for CAC 40 (0.964), DAX (0.974), and EURO STOXX 50 (0.867***) are all significant at 1%, showing strong volatility persistence in these markets. This means past volatility significantly impacts current volatility, typical of mature, integrated financial markets. This persistence can be explained by factors like investor expectations, economic cycles, andmonetary policies.

TUNINDEX influence:

The coefficients associated with TUNINDEX are weak and insignificant for CAC 40 (0.081) and DAX (0.006), indicating that the Tunisian market has no notable influence on these indices. This confirms the decoupling of the Tunisian market from major European markets, likely due to its limited financial integration, smaller size, and local economic specificities. For EURO STOXX 50, the coefficient (0.001***) is significant at 1%, but its minimal value suggests only marginal TUNINDEX influence, possibly reflecting indirect links through cross-border investments or regional shocks affecting both Tunisia and Europe.

These results emphasize that European markets are strongly influenced by their own past volatility but remain largely independent from the Tunisian market. This TUNINDEX independence can be explained by several factors:

Tunisia is an emerging market, less integrated into international financial flows than European markets.

Local economic and political specificities play a greater role in TUNINDEX dynamics than global events.

International investors have less exposure to the Tunisian market, limiting shock transmissions.

For investors, this low correlation offers diversification opportunities: including Tunisian assets in an international portfolio could reduce overall risk as the TUNINDEX moves independently from European markets. However, this independence also comes with specific risks, such as volatility linked to local economic and political conditions.

This analysis confirms that the TUNINDEX is relatively decoupled from major European indices, offering diversification potential while requiring particular attention to local risks. It also highlights strong volatility persistence in European markets, reflecting their maturity and financial integration.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this study carry significant implications for both financial market participants and policymakers, building on previous work by [5] and [1,5] on volatility modeling. For investors, the documented low correlation between Tunisian and European markets presents valuable diversification opportunities, consistent with portfolio theory [14] and recent emerging market studies [15]. However, this strategy requires careful implementation, including thorough assessment of Tunisia-specific risks, as highlighted in the institutional analysis of emerging markets by [16].

On the regulatory front, Tunisian authorities should prioritize strengthening domestic market infrastructure, drawing lessons from successful emerging market reforms documented by [17]. The establishment of a financial stability committee could build on the macroprudential policy frameworks proposed by [18]. European regulators should incorporate these findings into their financial integration assessments, complementing the financial spillover analysis of [19].

For the academic community, this study opens several research avenues that extend recent work on volatility transmission [20,21]. Future studies should examine decoupling patterns during extreme events using quantile methods [22], while sector-specific analyses could build on the industrial approach of [23]. The methodological combination of GARCH frameworks with machine learning techniques would advance recent hybrid modeling efforts [24]. Comparative studies could test whether Tunisia’s experience aligns with the emerging market patterns identified by [25].

These research directions would collectively advance our understanding of North–South financial market linkages, contributing to the growing literature on asymmetric market integration [26] while providing practical tools for risk management in complex financial systems [27].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M. and Y.G.; methodology, K.M.; software, K.M.; validation, K.M., and Y.G.; formal analysis, K.M.; investigation, K.M. and Y.G.; resources, K.M.; data curation, K.M. and Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.; writing—review and editing, K.M.; visualization, K.M.; supervision, K.M.; project administration, K.M.; funding acquisition, Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data was collected from investing.com. The data presented in this study is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GARCH | Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity |

| ARCH | Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity |

| EGARCH | Exponential Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity |

| GJR | Glosten–Jagannathan–Runkle (GARCH Model) |

| BEKK | Baba–Engle–Kraft–Kroner (Multivariate GARCH Model) |

| MS-GARCH | Markov-Switching Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity |

| TGARCH | Threshold Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity |

| FIGARCH | Fractionally Integrated Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity |

| FSV | Factor Stochastic Volatility |

| HAR | Heterogeneous Autoregressive (Model) |

| GARCH-MIDAS | GARCH-Mixed Data Sampling |

| ETF | Exchange-Traded Fund |

| FX | Foreign Exchange |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| ARCH-LM | ARCH–Lagrange Multiplier (Test) |

References

- Bollerslev, T. Generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity. J. Econom. 1986, 31, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.B. Conditional heteroskedasticity in asset returns: A new approach. Econometrica 1991, 59, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glosten, L.R.; Jagannathan, R.; Runkle, D.E. On the Relation between the Expected Value and the Volatility of the Nominal Excess Return on Stocks. J. Financ. 1993, 48, 1779–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollerslev, T.; Ghysels, E. Periodic autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 1996, 14, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R.F. Dynamic conditional correlation: A simple class of multivariate generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity models. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2002, 20, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarella, C.; Kang, B.; Nikitopoulos, B.; Tô, T.-D. Volatility dynamics in commodity markets. J. Futures Mark. 2015, 36, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzar, S.; Kayani, G.M.; Xiaofeng, H.; Ayub, U.; Rafique, A. Financial cointegration and spillover effectof global financial crisis: A study of emerging Asian financial markets. Econ. Res. 2019, 32, 187–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, I.; Nzotta, S.M.; Akujuobi, A.B.C.; Nwaimo, C.E. Volatility Spillover in African Stock Markets:Evidence from Nigeria, Ghana and South Africa. AFRE Account. Financ. Rev. 2022, 5, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Cabarcos, M.A.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.; Pineiro-Chousa, J. ESports ETF performance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2020, 159, 120191. [Google Scholar]

- Hongwiengjan, W.; Kumam, P.; Thongtha, D. Option pricing under TGARCH. J. Int. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2023, 18, 781–803. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, H. Quantile-based GARCH-MIDAS: Estimating value-at-risk using mixed-frequency information. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 43, 101965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyev, F.; Ajayi, R.; Gasim, N. Asymmetric volatility in Nasdaq-100. Quant. Financ. 2020, 20, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R.F.; Kroner, F. Multivariate Simultaneous Generalized ARCH. Econom. Theory 1995, 11, 122–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, H. Portfolio selection. J. Financ. 1952, 7, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloui, R.; Hammoudeh, S.; Nguyen, D. A time-varying copula approach to oil and stock market dependence. Energy Econ. 2013, 39, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekaert, G.; Harvey, C.R. Emerging equity markets. J. Empir. Financ. 2017, 44, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Claessens, S.; Yurtoglu, B.B. Corporate governance in emerging markets: A survey. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borio, C. The financial cycle and macroeconomics: What have we learnt? J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 45, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F.X.; Yilmaz, K. Better to give than to receive: Predictive directional measurement of volatility spillovers. Int. J. Forecast 2012, 28, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, D.G.; Schulze, N. Coexceedances in financial markets. Appl. Emerg. Mark. Financ. 2005, 6, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, T.C.; Jeon, B.N.; Li, H. Dynamic correlation analysis of financial contagion: Evidence from Asian markets. J. Int. Money Financ. 2007, 26, 1206–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.; Kim, T.-H.; Manganelli, S. VAR for VaR: Measuring tail dependence using multivariate regression quantiles. J. Econom. 2015, 187, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekaert, G.; Hodrick, R.J.; Zhang, X. International stock return comovements. J. Financ. 2009, 64, 2591–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjanpoller, W.; Minutolo, M.C. Volatility forecast using hybrid models. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 147, 113232. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Huo, R. Volatility transmissions. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2021, 46, 100747. [Google Scholar]

- Balli, F.; Zhang, J. Financial integration and risk sharing. J. Bank. Financ. 2012, 86, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R.F.; Ghysels, E.; Sohn, B. Stock market volatility and macroeconomic fundamentals. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2019, 101, 538–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).