Abstract

With growing emphasis on antibiotic-free poultry production, functional probiotics represent a promising strategy to improve gut health and reduce pathogen transmission. This study characterized three lactic acid bacteria (LAB) strains Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus NRRL-B-548 (LD), Lacticaseibacillus paracasei DUP-13076 (LP), and Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus NRRL-B-442 (LR) for their probiotic potential and evaluated their efficacy against Salmonella enterica in poultry. The LAB strains were assessed for acid and bile tolerance, lysozyme resistance, cholesterol assimilation, antimicrobial activity, surface hydrophobicity, epithelial adherence, hemolysis, and antibiotic susceptibility. Genomic analysis was performed to identify genes associated with probiotic functionality. The protective potential of LR and LP was further validated in hatchlings using a hatchery spray model challenged with Salmonella Enteritidis. All strains survived simulated gastric and intestinal conditions, exhibited strong adhesion to epithelial cells, and demonstrated high hydrophobicity, indicating robust colonization capacity. The LAB significantly inhibited Salmonella Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium, and S. Heidelberg growth in vitro and remained sensitive to clinically relevant antibiotics. In vivo application of LR and LP to hatching eggs markedly reduced S. Enteritidis colonization in the liver, spleen, and ceca of hatchlings. Further, genomic profiling of the LAB strains revealed genes for bacteriocin production, exopolysaccharide synthesis, and carbohydrate metabolism supporting probiotic function. In summary, the evaluated LAB strains exhibit multiple probiotic attributes and strong anti-Salmonella activity, confirming their potential as safe, hatchery-applied probiotics for improving gut health and biosecurity in poultry production systems.

1. Introduction

Probiotics have emerged as valuable alternatives to antibiotic growth promoters in poultry production, supporting both bird performance and food safety. Their supplementation in poultry feed or hatchery applications has been shown to improve growth rate, feed efficiency, intestinal morphology, immune response, and resistance to enteric pathogens such as Salmonella enterica and Campylobacter jejuni [1,2]. The gastrointestinal tract of poultry harbors a complex microbiota that plays a critical role in digestion, nutrient absorption, and the development of mucosal immunity [3]. Therefore, maintaining a balanced intestinal microbiome through probiotic supplementation is central to improving flock health, productivity, and disease resistance.

Early-life probiotic interventions such as in ovo delivery or spray application in hatcheries are particularly effective, as they allow beneficial bacteria to colonize the gastrointestinal tract before pathogenic organisms establish themselves [4,5]. Hatchery-based probiotic application has been demonstrated to reduce Salmonella contamination on egg surfaces, prevent trans-shell infection, and improve chick quality and hatchability [6,7]. Specifically, Salmonella enterica, a species comprising more than 2500 serotypes, including several poultry-relevant serovars such as Enteritidis, Typhimurium, and Heidelberg, remains a major target for early-life probiotic interventions due to its prevalence in initial production stages and its significance for both flock health and food safety [2]. Because the hatchery represents one of the most critical control points for microbial transmission in poultry production, such interventions have considerable potential to enhance biosecurity and minimize pathogen carryover from the hatchery to the farm [8]. While the benefits of probiotics in poultry production are well documented, the successful introduction of new strains requires rigorous scientific characterization to confirm efficacy and safety.

When identifying novel probiotic candidates, it is critical to comprehensively characterize their functionality and safety according to the guidelines established by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and World Health Organization (WHO). These criteria include (i) precise genotypic and phenotypic identification with strain deposition in a recognized culture collection, (ii) in vitro and in vivo evaluation of functional properties such as pathogen inhibition, acid and bile tolerance, and adhesion to epithelial surfaces, and (iii) safety assessment to confirm non-pathogenicity and absence of transferable antibiotic resistance [9]. In addition, the ability to produce antimicrobial compounds such as bacteriocins or hydrogen peroxide, remain stable under processing conditions, and confer measurable host benefits are important defining features of an effective probiotic [10].

Accurate classification and strain-level identification are essential, as probiotic properties are highly strain-specific and cannot be generalized even within a single species [11]. Therefore, extensive phenotypic and genotypic characterization is necessary to confirm the probiotic potential of newly isolated LAB (lactic acid bacteria) strains and determine their safety and functional value for animal applications [12]. Given these requirements, isolating and characterizing LAB strains with robust probiotic traits relevant to poultry production is essential for developing next-generation biosecurity and gut health interventions. Particular attention has recently focused on LAB capable of inhibiting Salmonella enterica, a major zoonotic pathogen responsible for significant economic losses and public health concerns in the poultry industry [6,8]. Characterizing such strains under simulated gastrointestinal conditions provides valuable insight into their survivability, adhesion capacity, and antimicrobial mechanisms, all of which are prerequisites for effective in vivo application.

Building on this context, our previous research similarly showed that Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus NRRL-B-548 (LD), Lacticaseibacillus paracasei DUP-13076 (LP), and Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus NRRL-B-442 (LR) effectively reduced the survival and virulence of Salmonella enterica serovars S. Enteritidis, multidrug-resistant S. Typhimurium DT104, and S. Heidelberg via modulation of gene expression [13]. These findings underscore the potential of LAB as poultry probiotics that not only enhance gut health but also function as natural antimicrobial agents against major foodborne pathogens. Although these earlier findings highlighted the antimicrobial efficacy of the selected LAB strains, their comprehensive probiotic characterization under simulated gastrointestinal conditions and their practical application in poultry systems remained to be elucidated. To bridge this gap, the present study focused on detailed functional and genotypic evaluation of the same strains to verify their suitability as hatchery-applied probiotics for Salmonella control.

Hence, this comprehensive evaluation was designed to connect the earlier observed antimicrobial effects of these LAB strains with their broader probiotic functionality, providing a foundation for their application in practical poultry systems. Specifically, the objective of the present study was to comprehensively characterize the probiotic attributes of LD, LP, and LR including their tolerance to gastrointestinal conditions, cell surface properties, antimicrobial activity, antibiotic susceptibility, hemolytic activity, and molecular identification and to evaluate their potential role in controlling Salmonella colonization in hatchlings. Emphasis was placed on their application within the poultry production system, particularly at the hatchery stage, as a natural biosecurity intervention to promote chick health and food safety [6,14].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

LAB strains Lactobacillus delbreuckii subsp. bulgaricus NRRL-B-548 (LD) and Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus NRRL-B-442 (LR) were obtained from the USDA NRRL culture collection. Lacticaseibacillus paracasei DUP-13076 (LP) was obtained from Dr. Bhunia, Molecular Food Microbiology Lab, Purdue University. These strains were cultured separately in de Mann, Rogosa, Sharpe broth (MRS, Difco, Sparks, MD, USA) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Salmonella Enteritidis (SE; SE-90) and multidrug resistant S. Typhimurium DT104 (ST; ST-43), and S. Heidelberg (SH; SH-V6FA) were used in the study. These strains represent common serovars associated with poultry and egg contamination and were selected to model field-relevant foodborne pathogens [15]. Salmonella cultures were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB, Difco, Sparks, MD, USA) for 24 h at 37 °C. After incubation, the cultures were centrifuged (3000× g, 12 min, 4 °C) and washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The pellet was then resuspended in PBS and used as the inoculum. LAB and pathogen counts were determined following serial dilution and plating on MRS and tryptic soy agar, respectively (TSA; Difco, Sparks, MD, USA) [13].

2.2. Tolerance to Simulated GI Transit

To assess the ability of the LAB strains to survive avian gut conditions, their tolerance to lysozyme, low pH, and bile salts was examined, reflecting the physiological barriers encountered in the poultry gastrointestinal tract.

Tolerance of LAB strains to lysozyme, low pH, and salt: Overnight LAB cultures (~9 log CFU/mL) were inoculated into MRS broth in the presence and absence 100 µg/mL lysozyme (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. To test the tolerance of LAB to acid, overnight cultures were suspended separately in MRS broth adjusted to a pH of 2 and 3 using 0.1 N HCl (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. Salt tolerance was determined by inoculating overnight LAB cultures (~9 log CFU/mL) in modified MRS broth containing 5% NaCl (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) followed by incubation at 37 °C for 24 h. The bacterial count in the culture was enumerated at the start and end of the incubation period by dilution and plating on MRS agar plates [10,16]. Survival percentage was calculated using the formula: % = [cell number (log CFU/mL) survived in modified MRS at the end of the incubation period/cell number (log CFU/mL) of initial inoculum at the start of incubation] × 100.

Tolerance of LAB strains to bile salts: Overnight LAB cultures (~9 log CFU/mL) were inoculated in MRS broth with various bile salt (sodium cholate and sodium deoxycholate, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) concentrations (0.3%, 0.5%, 1%, and 1.8%) and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. The bacterial count in the culture was enumerated following dilution and plating on to MRS agar plates. Survival percentage was calculated using the formula described above.

Simulated gut transit assay: Simulated gastric juice was prepared by adding 0.3 g (≥250 units/mg) pepsin into a sterile aqueous solution of NaCl (2.05 g/L), KH2PO4 (0.60 g/L), CaCl2 (0.11 g/L) & KCl (0.37 g/L), and adjusted to pH 2 using 1 N HCl. Intestinal juice was prepared by adding 0.1 g trypsin (1000–2000 units/mg) and 1.8 g bile salts into 100 mL of a sterile aqueous solution of 1.1 g NaHCO3 and 0.2 g NaCl at pH 8 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) [17]. The LAB strains (~8.7 log CFU/mL) were inoculated into the simulated gastric juice, incubated at 37 °C for 3 h, and the bacterial count in the gastric juice was enumerated at 0, 1, 2 and 3 h of incubation. The LAB culture from the simulated gastric juice was subsequently pelleted and suspended in simulated intestinal juice, incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and the bacterial count in the intestinal juice was enumerated at different times during the incubation period.

2.3. Adhesion and Colonization Assays

Determination of cell surface hydrophobicity of LAB strains: LAB strains at the stationary phase were centrifuged (10,000× g, 5 min). The resulting pellet was washed twice in PBS, resuspended in 0.1 mol/L KNO3 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and the absorbance at 660 nm was measured (A0). One milliliter of xylene (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the LAB suspension and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The two-phase system formed was mixed by vortexing for 2 min. Then, the water and xylene phases were separated by incubating at room temperature for 20 min. Following this, the aqueous phase was removed, and the absorbance at 660 nm was measured (A1). The percentage of the cell surface hydrophobicity was calculated using the formula (1 − A1/A0) × 100 [18].

Adherence to intestinal cells: The ability of LAB strains to adhere to intestinal epithelial cells was assayed using human colon cells [Caco-2, Human intestinal epithelial colon carcinoma cell line, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA; 17]. While derived from human cells, Caco-2 cells share conserved epithelial adhesion molecules (e.g., mucins, glycoproteins, and extracellular matrix receptors) that mediate LAB attachment in many vertebrate species, including poultry. Several studies have employed Caco-2 cells as an accepted surrogate model to predict LAB adherence to chicken intestinal tissues when direct avian models are unavailable [19,20]. Likewise, Neal-McKinney et al. [21], and Muyyarikkandy and Amalaradjou [13] validated their Caco-2 findings with chicken cecal epithelial cells, showing consistent adhesion patterns. Thus, adhesion to Caco-2 cells provides a baseline indicator of a strain’s colonization ability, which can then be confirmed in avian-specific assays.

Briefly, the monolayers were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Following three propagations, the cells (1 × 105/well) were seeded into 24-well tissue culture plates containing whole medium (DMEM + 10% FBS) and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 14–21 days for differentiation. The adhesion assay was performed according to Koo et al. [17]. Briefly, each LAB strain was inoculated on to the Caco-2 monolayer at a multiplicity of exposure (MOE) of 100 and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for an hour. At the end of the incubation period, the monolayers were washed three times with minimal media, treated with 0.1% triton × 100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and lysates were plated on to MRS agar to enumerate the adherent LAB population. The percentage of adhered LAB cells were determined using the formula: % Adherence = (CFU of adhered bacteria per mL/CFU of initially added bacteria per mL) × 100.

2.4. Functional and Health-Promoting Properties

Cholesterol assimilation ability of LAB strains: Cholesterol metabolism strongly influences lipid digestion, nutrient absorption, and carcass composition. LAB strains that assimilate cholesterol in vitro often possess bile salt hydrolase (BSH) activity. This enzyme deconjugates bile acids, which may improve lipid metabolism and enhance intestinal health [22]. In poultry, this can contribute to lower serum cholesterol and triglycerides, while also indicating probiotic survivability in bile-rich gut environments [2,23]. Hence, we characterized the ability of LR, LP and LD to assimilate cholesterol. Briefly, the LAB strains were grown in MRS broth supplemented with 0.5% (w/v) bile salts and 10 mg cholesterol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) dissolved in ethanol, the phases were separated, and the percentage of cholesterol assimilation was determined in the ethanol phase [24].

Antibacterial activity: LAB strains were screened for their anti-Salmonella effect using the co-culture assay [13]. Individual LAB strains (~8 log CFU/mL) were co-cultured with the different Salmonella serovars, S. Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium and S. Heidelberg (~6 log CFU/mL) in broth containing equal quantities of MRS and TSB and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The surviving Salmonella population in the co-culture was enumerated at different time points following serial dilution and plating on tryptic soy agar (TSA). Duplicate samples were used for each treatment and control, and the experiment was repeated three times.

Hemolytic activity: LAB strains were streaked on the surface of Columbia blood agar plates supplemented with 5% sheep blood (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). After 48 h of incubation at 30 °C, the plates were examined for hemolytic reaction. Presence of a clear zone around the bacterial growth would be indicative as β-hemolysis, while appearance of a greenish coloration would imply α-hemolysis. Lack of a clearance zone or greenish discoloration indicates no hemolysis (γ-hemolysis) [14]

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing: Susceptibility of the LAB strains to tetracycline, imipenem, minocycline, piperacillin, ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin, and ampicillin was measured as per the FEEDAP guidelines [25,26] using the ETEST (Biomerieux, St. Louis, MO, USA). The inoculum was prepared by suspending colonies from cultures grown in MRS broth to cell density corresponding to McFarland 1 standard. The suspension was spread evenly on the MRS agar plates by using a sterile cotton swab. The ETEST strips were placed on the air-dried agar surface and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. The diameters (mm) of the inhibition zone were measured at the end of the incubation period. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for each antibiotic were read as the lowest antibiotic concentration at which growth was inhibited [10].

2.5. Genome Characterization

Lactic acid bacteria were grown in de Man-Rogosa-Sharpe broth at 37 °C for 24 h prior to DNA extraction. A paired-end library was created using the MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) in the Microbial Analysis, Resources, and Services Facility at the University of Connecticut (Storrs, CT, USA) with an average insert size of 550 and an average read length of 251 bp. Quality checks were performed using FastQC v0.11.5. Adaptors, primers, and bases with a Phred score of <20 were trimmed using Trimmomatic v0.36 [27] with a headcrop of 15. The SPAdes genome assembler v.3.13.0 [28] was used for the de novo assembly of paired end reads to create 111 contigs, and any contigs with less than 200 bp were discarded. Genome annotations were carried out using the Rapid Annotations using Subsystems Technology (RAST) server and the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Automatic Annotation Pipeline (PGAAP) [29].

2.6. In Vivo Validation of Anti-Salmonella Activity of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus (LR) and Lacticaseibacillus paracasei (LP) in Layer Hatchlings

Bacterial cultures: A five-strain cocktail of Salmonella Enteritidis (SE) was formulated using isolates SE12 (chicken liver, phage type 14b), SE21 (chicken intestine, phage type 8), SE28 (chicken ovary, phage type 13a), SE31 (chicken gut, phage type 13a), and SE90 (human, phage type 8) [30]. Each isolate was adapted for nalidixic acid resistance (50 µg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) prior to use. For culture preparation, individual SE isolates were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB; Difco, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA) supplemented with nalidixic acid (TSB + NA) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Cultures were passaged three times to ensure stability, then centrifuged at 3600× g for 15 min at 4 °C to collect bacterial pellets. The pellets were washed twice and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.0). Equal volumes of the five resuspended isolates were combined to generate the SE inoculum [30]. Bacterial concentrations in the individual isolates and the final SE cocktail were confirmed by serial dilution and plating on xylose lysine deoxycholate agar containing nalidixic acid (XLD + NA; Difco, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA), followed by incubation at 37 °C for 24 h Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus (LR) and L. paracasei (LP) were cultivated as previously described. After three consecutive passages, cultures were centrifuged at 3600× g for 15 min at 4 °C, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in the same buffer. The resulting suspensions were used as probiotic spray treatments applied to the broad end of hatching eggs [6].

Hatching Eggs and SE inoculation: This study was conducted at the UConn vivarium with approval from the UConn Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol #A23-003). A total of 105 freshly laid eggs from a certified Salmonella-free Lohman Lite flock (45-week-old) were obtained from the University of Connecticut poultry farm. The day before the experiment, eggs were transported to the laboratory and tempered at 23 °C for 10–12 h [6]. On day 0, eggs were disinfected with 70% ethanol and allowed to air dry Each egg was then spot inoculated on the broad end with 100 μL of SE (~7.0 log CFU/egg). The eggs were dried for 1 h at 23 °C to facilitate bacterial attachment. This initial inoculation on day 0, along with subsequent re-inoculations on days 10 and 18 of incubation, was performed to simulate potential Salmonella contamination originating from incoming eggs, handling during incubation/candling, or the hatchery environment [6,30].

Probiotic Treatment Application: Following surface disinfection on day 0, the eggs were randomly assigned to one of three treatments groups (35 eggs/group): (i) Control—eggs sprayed with PBS, (ii) LR—eggs sprayed with PBS containing LR (@ 8.0 log CFU/egg), and (iii) LP—eggs sprayed with PBS containing LP (@ 8.0 log CFU/egg). Each egg was sprayed with its respective treatment as previously described [6]. The spray treatments were reapplied on day 10 and day 18 of incubation following SE re-inoculation simulating a potential treatment application time point that coincides with current candling practice in the industry [31]. Eggs were incubated for 21 days in table-top hovabators (1602 N hovabators, GQF Manufacturing Inc., Savannah, GA, USA) equipped with automatic turners (1611 automatic egg turner with 6 universal egg racks, GQF Manufacturing Inc., Savannah, GA, USA).

Hatchling sampling and microbial analysis: Following hatching on day 21, six chicks per group were sampled to determine Salmonella populations. Hatchlings were humanely euthanized using carbon dioxide gas. They were aseptically opened, and the liver, spleen, and ceca were collected into separate tubes containing PBS. The samples were weighed, homogenized, and serially diluted in PBS [32]. Dilutions were plated onto XLD + NA plates to enumerate surviving SE populations. For samples yielding no colonies on direct plating, the samples were enriched in selenite cysteine broth, followed by streaking on XLD + NA plates to detect SE presence/absence in the samples.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All in vitro assays were performed in duplicates and repeated three times. All experiments, except the simulated gut transit and antibacterial assays, were conducted using a completely randomized design (CRD). The simulated gut transit and antibacterial assays were set up as a CRD with repeated measures. Accordingly, the experiments were analyzed using either one-way ANOVA or repeated measures ANOVA to evaluate significant differences. The data were analyzed using Proc MIXED procedure of SAS (Version 9.4, Cary, CA, USA). A confidence interval of 95% was considered significant (p < 0.05).

3. Results and Discussion

A balanced intestinal microbiota plays a pivotal role in poultry growth, feed efficiency, nutrient absorption, and resistance to enteric pathogens. Probiotic supplementation has been recognized as an effective strategy to support gut health and biosecurity, particularly in antibiotic-free poultry production systems [1,3]. The present study characterizes lactic acid bacteria strains with potential application in poultry production, focusing on their ability to withstand gastrointestinal conditions, adhere to intestinal epithelium, assimilate cholesterol, inhibit Salmonella, and sustain desirable antimicrobial and genomic traits.

3.1. Tolerance to Simulated GI Transit

3.1.1. Tolerance of LP, LR and LD to pH, Lysozyme, and Osmotic Stress

The low pH (2–3) in the proventriculus and gizzard of birds serves as an effective barrier limiting bacterial passage into the intestine [2,12]. Since any probiotic intended for poultry application must survive this acidic environment to reach the lower gut, acid tolerance is a key functional trait [14]. In this study, the pH of MRS broth was adjusted using 0.1 N HCl to 2 and 3 to evaluate survival of LP, LR, and LD. As seen from Table 1, all the LAB strains showed a 0.5–1 log reduction following incubation at a pH of 2–3, and the survivability was ~94–97% after 3 h of incubation. Furthermore, we did not observe any significant difference in survival across the three different strains irrespective of the pH tested. This suggests these LAB would likely survive passage through the upper digestive tract of chicks, reaching the intestine in viable form where they could colonize and support digestion and pathogen exclusion [1]. These results agree with previous studies that demonstrated the survivability of LAB under these physiological conditions [33,34].

Table 1.

Survival of Lactobacillus delbreuckii subsp. bulgaricus NRRL-B-548 (LD), L. rhamnosus NRRL-B-442 (LR) and L. paracasei DUP-13076 (LP) under different simulated physiological conditions in vitro.

Lysozyme, an antimicrobial enzyme secreted along mucosal surfaces of the crop and proventriculus, hydrolyzes the β(1–4) linkages of peptidoglycan in bacterial cell walls. Because it forms part of the avian innate defense, probiotic strains must tolerate lysozyme exposure to persist after oral administration [35]. In the present study, all LAB strains exhibited high lysozyme tolerance, showing ~99% survival after 24 h in 100 µg/mL lysozyme (Table 1). No significant differences were detected among LP, LR, and LD (p > 0.05). This strong resistance mirrors previous reports for lysozyme-tolerant Lactobacillus [10,35] and indicates that these strains can survive exposure to digestive secretions encountered before intestinal colonization.

Common salt (NaCl) is routinely included in poultry diets at 0.2–0.5% to supply essential sodium and chloride [36], yet tolerance to higher concentrations reflects broader osmotic resilience. In effect, salt tolerance influences survival in low water activity environments and enzyme activity. Thus, probiotics’ ability for salt tolerance is an indicator of its survivability across diverse environments [37,38]. Further, research indicates that high amounts of salt can impact cell viability, with relevance to the degree of survival and activity of the LAB strains [39]. As seen with the lysozyme assay, exposure of the different LAB strains to 5% NaCl did not affect their growth. In fact, we did not observe any significant reduction in LAB population through the 24 h incubation period (p > 0.05). Approximately 99% of the population survived the exposure to 5% NaCl in the growth environment (Table 1). This is in line with previous findings where different LAB strains were shown to survive and grow in the presence of 4% salt [40]. Similarly, LAB (L. rhamnosus, L. delbrueckii, L. paracasei, L. gasseri) isolated from different sources including poultry gut were seen to survive in 1.0–9.0% NaCl [22,38]. Such osmotolerance implies that LP, LR, and LD could remain viable during feed mixing, storage, and administration under farm conditions, important for maintaining consistent probiotic delivery and gut colonization in birds [1,37].

3.1.2. Tolerance of LAB Strains to Bile Salts

Bile salts, secreted into the small intestine of birds during digestion, are important antimicrobial components of the host’s innate defense and strongly influence intestinal microbial composition [41]. The concentration of bile salts in the intestine can range from 0.2 to 2% (w/v), depending on feed composition, bile secretion rate and intestinal segment [42]. Because bile salts can disrupt bacterial cell membranes and inhibit growth, probiotics used in poultry must tolerate these conditions to survive and function effectively in the small intestine. In this study, all three strains were able to survive in significant numbers when exposed to different bile salt concentrations and increasing bile levels resulted in a clear dose-dependent reduction in viability for LR, LD and LP, with linear regression analysis confirming a strong negative relationship across the tested range (R2 = 0.96–0.99). Although LP populations differed slightly from initial counts at 0 h, no significant effect of bile concentration was observed at 24 h, whereas LR and LD exhibited a small but significant decrease in viability with increasing bile levels (p < 0.05; Table 1). At low bile concentration (0.3%), LR and LD survivability was reduced by ~0.3 log (>97% survivability), and as the concentration of bile increased to 1.8%, survivability reduced to ~92% (~0.8 log reduction; Table 1). This difference in bile tolerance has been previously reported to vary widely among Lactobacillus species [43,44], and such variation has been used to classify strains as bile-sensitive or bile-tolerant [10]. In the present study, all three strains (LP, LR and LD) maintained substantial populations across bile concentrations, indicating that they are bile tolerant. The observed survival rates suggest that LP, LR and LD would remain metabolically active after ingestion, facilitating their establishment in the upper intestinal tract and subsequent proliferation in the ceca, where most beneficial fermentation and pathogen exclusion occur [38].

3.1.3. Gut Transit Assay

Probiotic cultures intended for poultry applications must survive a sequence of digestive barriers including gastric acidity, lysozyme, and bile salts before reaching the intestine where they can exert beneficial effects. Because most microorganisms fail to survive passage through the upper digestive tract, particularly the strongly acidic environment of the gizzard and proventriculus, evaluating survival under simulated gut conditions provides key insight into probiotic robustness. The pH of the proventriculus typically ranges from 3.5 to 4.5, while the gizzard pH averages 2.0 to 3.0, occasionally reaching 1.5 depending on feed type and particle size [45,46]. Rapid digesta flow from these compartments to the duodenum (pH ~5.5–6.5) exposes microorganisms to abrupt pH transitions. Accordingly, tolerance to these stresses indicates a strain’s potential to remain viable long enough to colonize the intestinal tract and promote microbial balance in birds.

In the present study, the probiotic cultures (8.5–8.7 log CFU/mL) were initially exposed to simulated gastric fluid at pH of 2 for a period of 3 h. Exposure to low pH resulted in a significant (p < 0.05) reduction in LAB population by 0.5 and 1 log at 1 and 3 h, respectively (Figure 1). Overall, 87–92% of the LAB (7.4–8 log CFU/mL) were recovered at the end of the 3 h gastric phase. As previously reported, LAB strains that survived in the presence of lysozyme and simulated gastric juice were also tolerant to bile salts [12]. In our study, the high survival in gastric transit is in line with higher recovery following exposure to 0.3–1.8% bile salts (Table 1; Figure 1). Together, these findings suggest that the three strains possess the physiological resilience required to traverse the gastric compartments of poultry.

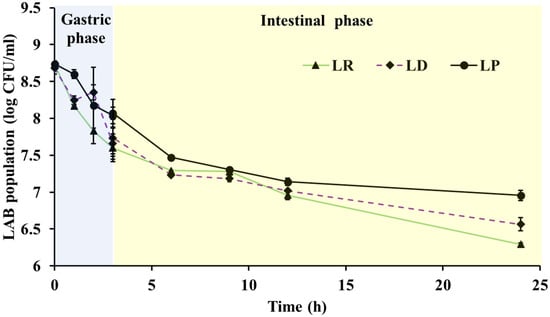

Figure 1.

Survival of Lactobacillus delbreuckii subsp. bulgaricus NRRL-B-548 (LD), Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus NRRL-B-442 (LR) and L. paracasei DUP-13076 (LP) during stimulated in vitro gut transit assay. LP, LD and LR were cultured in artificial gastric juice for 3 h, then transferred to simulated intestinal juice for a period of 24 h. Data are expressed as mean ± SE.

Following the simulated gastric phase, the LAB were transferred to intestinal fluid for 24 h to model exposure to bile and pancreatic enzymes encountered in the small intestine. At the start of this phase, viable counts averaged 7.5–8 log CFU/mL, and after 24 h populations declined by only 1.2–1.5 logs (Figure 1), corresponding to 82–86% survival (6.5–6.9 log CFU/mL). Overall, these experiments demonstrate that LP, LR, and LD can survive in significant numbers when exposed to an in vitro gut transit system. Therefore, these cultures could potentially endure transit through and take up residence in the gastrointestinal environment of the chicken. Similar survivability for related LAB was reported following in vitro gut transit assay by Tang et al. [47] and Kouadio et al. [14]. Further, compared to other LAB genera, strains of the genus Lactobacillus were seen to be more resilient to low pH, bile salts [48]. Contrariwise, Jang et al. [18] reported significant variability among Lactobacillus spp. For example, L. rhamnosus GG and L. brevis G1 demonstrated a survivability of 52.48 and 87.09% in simulated gastric conditions, respectively. Further, L. brevis KU15153 was seen to have a significantly higher viability in bile acids when compared to L. rhamnosus GG [18]. In our study, when compared to the start of the gut transit assay, ~82–86% of LAB population was still recovered following simulated gastric and intestinal transit (Figure 1).

Collectively, these results confirm that LP, LR, and LD can withstand sequential exposures mimicking the digestive tract, maintaining high viability through both gastric and intestinal phases. Such robustness is particularly important for hatchery-based probiotic applications, where probiotics applied to hatching eggs might penetrate the eggshell pores and interact with the developing embryo. Early microbial contact may allow beneficial bacteria to translocate to the embryonic gut, facilitating pre-hatch seeding of commensal microbiota and enabling these LAB to occupy ecological niches ahead of pathogens such as Salmonella Enteritidis [5]. By establishing early colonization, these strains could enhance gut maturation, improve chick resilience, and reduce the risk of pathogen transmission from hatchery to farm [4,8].

3.2. Adhesion and Colonization of the Intestinal Tract

In poultry, probiotic adhesion to the intestinal epithelium is a critical trait that supports gut health by promoting colonization, stabilizing the microbiota, and limiting pathogen attachment. Adhesion allows beneficial bacteria to form biofilms, compete for receptor sites, and modulate mucosal immunity [43,49]. In newly hatched chicks, the gastrointestinal tract is relatively sterile, and rapid colonization by beneficial microbes helps shape early immune development and intestinal barrier function [3]. Therefore, evaluating the ability of candidate strains to adhere to intestinal epithelial cells provides insight into their potential for persistence and competitive exclusion within the avian gut.

In this study, adhesion was quantified using the Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cell model, a standardized in vitro system that exhibits morphological and functional characteristics similar to avian enterocytes [21]. The LAB strains demonstrated strong adhesive capacity, with 86–89% of the cells adhering to the monolayers (Table 2). Specifically, inoculation of Caco-2 cells with 7 log CFU/mL of each LAB strain at a multiplicity of exposure (MOE) of 100 resulted in the recovery of 6–6.2 log CFU of adherent bacteria. Comparable adherence levels were observed previously with these same strains when tested against chicken cecal epithelial cells, with adhesion rates averaging 85% [13]. The high adherence observed here indicates that LP, LR, and LD possess surface properties conducive to binding intestinal epithelial receptors, a key step for colonization in both mammalian and avian hosts. In poultry, such adhesive capability can facilitate early establishment of commensal populations that occupy ecological niches otherwise available to pathogens like Salmonella and Campylobacter, thereby contributing to improved gut health and reduced pathogen load [1,21].

Table 2.

Adherence, hydrophobicity, and cholesterol assimilation properties of Lactobacillus delbreuckii subsp. bulgaricus NRRL-B-548 (LD), Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus NRRL-B-442 (LR) and L. paracasei DUP-13076 (LP).

Adhesion of bacteria to host cells is a complex process influenced by multiple surface factors, including cell-wall components, extracellular proteins, and hydrophobic interactions [12]. One such physicochemical property, cell surface hydrophobicity, is often used as an indirect predictor of bacterial adhesion potential. In this study, hydrophobicity values for LP, LR, and LD ranged from 22% to 24.5% (Table 2), consistent with earlier reports describing strain-dependent variation in Lactobacillus hydrophobicity [50,51]. Although differences among strains were not statistically significant (p > 0.05), a positive association between hydrophobicity and adhesion was observed with LP, which exhibited the highest hydrophobicity (24.5%), also showed the highest adhesion rate (89%). This relationship has been noted in other Lactobacillus species where higher hydrophobicity correlates with enhanced epithelial attachment and persistence [52,53]. Collectively, the strong adhesive capacity and hydrophobic surface characteristics of LP, LR, and LD underline their potential to establish beneficial populations within the chick intestine and contribute to sustained pathogen exclusion and intestinal integrity in poultry.

3.3. Functional and Health-Promoting Properties

3.3.1. Cholesterol Assimilation Activity

When grown in the presence of 0.5% bile, LP, LR, and LD assimilated 56%, 54%, and 52% of the cholesterol in the growth medium, respectively (Table 2). This capacity to remove cholesterol under bile conditions indicates active interaction between bile salt hydrolase enzymes and cell-surface components of the bacteria. Palaniyandi et al. [54] similarly reported that L. fermentum MJM60397 assimilated greater amounts of cholesterol when incubated in medium containing 0.3% bile, proposing that deconjugated bile acids precipitate cholesterol, thereby reducing its concentration in the culture medium [55]. L. plantarum NR74 was likewise shown to assimilate cholesterol through bile-salt hydrolase activity [56]. There are several mechanisms by which probiotics reduce cholesterol level in the host, and they are (i) assimilation of cholesterol into the cell membrane during growth, (ii) binding of cholesterol to the bacterial surface, (iii) disruption of cholesterol micelles, (iv) deconjugation of bile salts, and (v) enzymatic bile-salt hydrolase activity [57]. The ability of LAB to assimilate cholesterol in vitro suggests that similar interactions could occur in the intestine following ingestion.

In poultry, regulation of lipid metabolism is important not only for health but also for production traits such as carcass yield, meat quality, and egg composition. Probiotics capable of deconjugating bile salts or assimilating cholesterol may lower serum cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations, reduce hepatic lipid deposition, and improve feed efficiency. For example, supplementation of Lactobacillus cultures in broiler diets has been reported to decrease plasma cholesterol and abdominal fat [58], while other studies showed improvements in fatty-acid profile and overall meat quality [23]. By similar mechanisms, LAB that assimilate cholesterol in the intestine may reduce lipid absorption, thereby modulating energy partitioning toward lean tissue growth and potentially improving the nutritional value of poultry products for consumers. Given the in vitro cholesterol-assimilating ability observed for LP, LR, and LD, these strains may contribute to lipid modulation and metabolic health in birds while also providing ancillary benefits to product quality. Future in vivo studies in broilers or layers will be valuable to confirm whether these strains can influence serum and hepatic cholesterol concentrations, fat deposition, or yolk lipid content under commercial feeding conditions.

3.3.2. Antibacterial Activity

A key functional property of probiotic bacteria is their ability to inhibit pathogens through production of antimicrobial metabolites, competitive exclusion, and modulation of pathogen virulence. This trait is particularly relevant to poultry, where Salmonella enterica remains one of the most important foodborne pathogens associated with both production losses and public-health risk. In this study, LP, LR, and LD exhibited strong antagonistic activity against Salmonella serovars Enteritidis (SE-90), Typhimurium DT104 (ST-43), and Heidelberg (SH-V6FA). All three LAB strains completely inhibited Salmonella growth by 24 h compared with the control, which reached ~8 log CFU/mL (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of Lactobacillus delbreuckii subsp. bulgaricus NRRL-B-548 (LD), Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus NRRL-B-442 (LR) and L. paracasei DUP-13076 (LP) on Salmonella enterica survival in vitro.

Notably, the antimicrobial efficacy varied between LAB species and Salmonella serovars. For example, LD achieved complete inhibition (~8 log reduction) of S. Heidelberg by 10 h, while reductions in S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium were ~2 log and 4–6 log, respectively. LP and LR showed similar inhibition kinetics, with all three strains demonstrating stronger effects against S. Heidelberg and S. Typhimurium than against S. Enteritidis. Such variability supports previous observations that the antimicrobial activity of LAB is highly strain-specific [12,59]. For instance, L. casei C3 inhibited S. Typhimurium ATCC 14028 and S. Enteritidis ATCC 13098 more effectively than L. paracasei G10 [12], while L. delbrueckii OS1 exhibited superior inhibition of S. Typhimurium relative to other pathogens [59]. Beyond direct growth inhibition, our earlier work demonstrated that LP, LR, and LD attenuate Salmonella virulence by down-regulating key virulence genes involved in adhesion and invasion [13]. In chicken cecal epithelial and macrophage models, these LAB strains significantly reduced Salmonella adherence and internalization, confirming their ability to interfere with host–pathogen interactions.

The significant anti-Salmonella activity observed here has direct implications for poultry production. Probiotic strains capable of suppressing Salmonella growth and virulence can lower intestinal pathogen load, minimize systemic dissemination, and consequently reduce carcass contamination during processing. When applied at the hatchery stage, as demonstrated later in this study, these LAB may further restrict early Salmonella colonization by establishing a protective microbial barrier in chicks prior to farm exposure [6,8]. Collectively, these findings highlight the strong antimicrobial potential of LP, LR, and LD and underscore their relevance as natural, antibiotic-free interventions for improving poultry health and food safety.

3.3.3. Hemolytic Activity

The hemolytic property of bacteria is an indicator of potential pathogenicity, and absence of hemolysis is a primary safety requirement for probiotic use [60]. In this study, none of the LAB strains LP, LR, or LD showed hemolytic activity on sheep blood agar, exhibiting γ-hemolysis (no zone of clearing) after 48 h of incubation (Table 4). The lack of hemolytic ability is critical to deem the safety of any organism being characterized for its probiotic properties [60]. In effect, the absence of hemolytic activity is a prerequisite for safety and selection of a new probiotic candidate [61]. Similar findings have been reported for other bacteria characterized as probiotics including L. paracasei L2, L. delbrueckii OS1, L. casei C3, L. fermentum G9 and L. paracasei G10 [10,12,59]. Further, this trait satisfies FAO/WHO guidelines that specify non-hemolytic activity as an essential safety criterion for probiotic selection [61]. The γ-hemolytic phenotype observed for LP, LR, and LD thus reinforces their suitability for practical application in poultry without posing hemolytic or cytotoxic risk to the host.

Table 4.

Hemolytic activity and antibiotic susceptibility of Lactobacillus delbreuckii subsp. bulgaricus NRRL-B-548 (LD), Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus NRRL-B-442 (LR) and L. paracasei DUP-13076 (LP).

3.4. Antibiotic Resistance Phenotype

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) remains a global concern for both human and animal health, particularly in the poultry industry, where antibiotic use for disease prevention or growth promotion has historically contributed to the development of resistant microbial populations. Probiotic cultures intended for poultry must therefore be evaluated for antibiotic susceptibility to ensure they do not harbor or transfer resistance determinants that could compromise antimicrobial stewardship efforts [14]. In this study, the antibiotic resistance profiles of LP, LR, and LD were assessed using the E-TEST method to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), defined as the lowest concentration of an antibiotic that inhibits visible bacterial growth. Each strain was classified as resistant, intermediate, or sensitive according to the FEEDAP guidelines [25,26]. The strains were tested against seven antibiotics representing major classes: cell wall inhibitors (ampicillin, amoxicillin, imipenem, piperacillin), nucleic acid inhibitors (ciprofloxacin), and protein synthesis inhibitors (tetracycline and minocycline).

As shown in Table 4, susceptibility patterns varied among strains. LR and LD exhibited resistance to ciprofloxacin but were intermediately resistant to ampicillin, while LP showed intermediate resistance to ciprofloxacin and remained sensitive to ampicillin. All strains were sensitive to tetracycline, imipenem, minocycline, piperacillin, and amoxicillin. These findings are consistent with earlier studies demonstrating susceptibility of Lactobacillus species to β-lactams and tetracyclines [14,18]. Similar resistance to ciprofloxacin has been reported among Lactobacillus strains [47,62]. The mechanisms underlying fluoroquinolone resistance in LAB remain poorly defined but are thought to be intrinsic and chromosomally encoded rather than plasmid-borne, suggesting they are non-transmissible and pose minimal risk of horizontal gene transfer [62]. This distinction is critical for probiotic safety, as transmissible resistance genes could spread to pathogenic bacteria in the poultry gut. Importantly, none of the strains exhibited resistance to clinically important antimicrobials commonly used in poultry, supporting their suitability for feed or hatchery applications.

In the context of poultry production, probiotics with predictable and intrinsic resistance profiles can be safely co-administered in environments where residual antimicrobial exposure may occur (e.g., during veterinary treatment or from contaminated feed), without contributing to the AMR burden. The sensitivity of LP, LR, and LD to most tested antibiotics, combined with their previously demonstrated non-hemolytic nature, strengthens their candidacy as safe microbial additives for poultry production. Their use aligns with the industry’s shift toward antibiotic-free feeding strategies, helping maintain gut health and pathogen control while mitigating the risk of antimicrobial resistance proliferation [3,25].

3.5. Genomic Characterization

Whole-genome sequencing was performed to identify genetic determinants supporting the probiotic functionality of the three LAB strains. Genes associated with carbohydrate metabolism, adhesion, antimicrobial peptide synthesis, and stress tolerance were analyzed, as these traits are critical for bacterial survival, colonization, and pathogen inhibition in the avian gastrointestinal tract [3].

The Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus B-442 genome (2974,909 bp) consists of a single circular chromosome with a G + C content of 46.7%, consistent with other L. rhamnosus strains [63,64]. The chromosome contains 2989 coding sequences and 75 RNA genes (14 rRNA, 58 tRNA, and 3 ncRNA) as predicted by PGAAP. A total of 333 functional subsystems were identified, and RAST analysis assigned 1826 protein-coding genes to functional categories, with carbohydrate metabolism (27%) and protein metabolism (11%) being the most represented. Many carbohydrate-associated genes encoded disaccharide transporters and utilization enzymes, similar to those found in L. rhamnosus GG [63,65], supporting metabolic flexibility for utilizing diverse feed carbohydrates and mucosal sugars in the poultry gut. In addition, genes involved in bacteriocin and colicin synthesis were detected, indicating the potential to produce antimicrobial peptides effective against Salmonella and other enteric pathogens. Similarly to other strains of the species, L. rhamnosus NRRL B-442 was found to contain genes responsible for exopolysaccharide biosynthesis [64,65], suggesting the ability to form protective biofilms on intestinal surfaces that can enhance adhesion and gut persistence. No virulence-associated genes were detected. This whole-genome shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession number PKQF00000000 [66].

For Lacticaseibacillus paracasei DUP-13076, the draft genome consists of a circular chromosome of 3048,314 bp with a G + C content of 46.3%. The assembly produced 150 contigs with an average length of 153,320 bp, and the largest contig measured 434,880 bp. The genome contains 342 subsystems and 3066 coding sequences. Annotation by the NCBI PGAAP identified 77 RNA genes (16 rRNA, 58 tRNA, and 3 ncRNA). Subsystem analysis revealed that the majority of genes were associated with cellular metabolism (76%), followed by cell wall and capsule synthesis (7%) and membrane transport (4%). The presence of genes involved in polyamine, betaine, and glycine synthesis and uptake suggests enhanced osmotic stress tolerance, an advantageous trait for survival in bile-rich intestinal environments. Additionally, genes encoding adhesion factors and antimicrobial peptides, including colicin V and bacteriocin clusters, were detected, supporting both colonization and pathogen inhibition capacities. Similarly to L. paracasei M38, these genetic features indicate metabolic adaptability and probiotic potential relevant to poultry gastrointestinal ecology [11,67]. No virulence-associated genes were identified. The genome sequence has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession number PKQJ00000000 [68].

The genome of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus NRRL B-548 comprises 3,010,111 bp with a G + C content of 46.6%. A total of 163 contigs were identified, with an average length of 159,830 bp and a maximum of 537,789 bp. The chromosome contains 371 subsystems and 3042 coding sequences, including 79 RNA genes (16 rRNA, 57 tRNA, and 6 ncRNA). Most genes were associated with carbohydrate, protein, RNA, DNA, and nucleotide metabolism [69], reflecting strong fermentative capacity for diverse substrates in the avian diet. Eleven genes with probiotic functions were identified, including those encoding adhesion proteins and antimicrobial peptides such as bacteriocin and colicin V [69,70]. These attributes are consistent with enhanced persistence and inhibitory activity against Salmonella within the poultry gut environment. The genome has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession number PRJNA474941.

Together, the genomic profiles of LP, LR, and LD reveal a complementary suite of traits supporting their probiotic potential and potential utility in poultry. Genes conferring carbohydrate utilization, adhesion, EPS formation, stress tolerance, and bacteriocin synthesis suggest these LAB are well equipped to colonize the avian gastrointestinal tract, promote gut homeostasis, and antagonize pathogens. The absence of virulence factors and transferable resistance genes further reinforces their suitability for safe application in poultry production systems aimed at improving health and reducing antibiotic dependence.

3.6. Protective Effect of LP and LR Application to Hatching Eggs Against Salmonella Enteritidis Colonization in Hatchlings

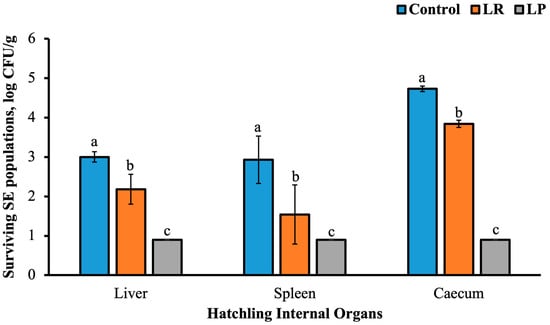

This in vivo trial served to validate the probiotic efficacy demonstrated in our in vitro assays, confirming whether the antimicrobial and colonization traits observed for LP and LR could translate to protection in hatchlings. Probiotic spray treatments to hatching eggs was effective in reducing Salmonella Enteritidis (SE) colonization across multiple organs in newly hatched chicks (Figure 2). In the liver, control hatchlings showed a substantial SE load (3.00 ± 0.13 log CFU/g), whereas LR treatment reduced this by 0.82 log (2.18 ± 0.38 log CFU/g), while SE populations were undetectable (negative by enrichment) in the LP group (p ≤ 0.05; Figure 2). Spleen colonization followed a similar trend, with 2.93 ± 0.60, 1.54 ± 0.75, and 0.90 log CFU/g SE in the control, LR, and LP groups, respectively. As expected, highest SE loads were recovered in the hatchling cecum. In the control group, cecal SE loads reached 4.73 ± 0.07 log CFU/g, whereas LR treatment reduced counts to 3.84 ± 0.09 log CFU/g. In contrast, no SE colonies were detected in the LP-treated group by direct plating, with only enrichment cultures yielding positive results (p ≤ 0.05). These results demonstrate that both probiotics significantly lowered intestinal and systemic Salmonella burdens, with LP showing the strongest protective effect.

Figure 2.

Effect of probiotic spray application to hatching eggs on Salmonella Enteritidis populations in the hatchling liver, spleen, and caecum. Different superscripts indicate statistical significance between treatment groups within each tissue type at p ≤ 0.05. The limit of detection for plate counts was 1 log CFU/sample.

These in vivo reductions are consistent with previously reported probiotic effects in poultry, where Lacticaseibacillus supplementation has been shown to suppress Salmonella colonization and systemic spread. For example, L. rhamnosus GG supplementation in broilers decreased cecal Salmonella loads by ~1.9 log CFU/g [71], while L. rhamnosus P118 inhibited intestinal Salmonella colonization and prevented pathogen translocation to peripheral organs through enhanced colonization resistance and epithelial protection [72]. Similar mechanisms likely explain the present findings, wherein the probiotics may have established early protective barriers in the intestine, reducing initial Salmonella attachment and subsequent dissemination to systemic tissues such as the liver and spleen [71,72].

Differences in probiotic performance among strains and target organs further illustrate the strain-specific nature of probiotic efficacy. While LP and LR both significantly reduced Salmonella loads, the magnitude of effect varied across organs, likely reflecting the distinct infection pathways used by Salmonella during cecal colonization and systemic invasion. Cecal colonization is primarily localized and dependent on epithelial attachment, whereas hepatic and splenic infections arise from bacterial translocation and macrophage-mediated dissemination [72]. These biological differences, along with inherent variations in adhesion and metabolite production among LAB strains, may explain the variable degree of protection observed in this study, consistent with earlier comparisons of Lactobacillus strains in poultry [73]. Moreover, timing of probiotic administration is crucial: preventive application, as used here, is far more effective than treatment after infection establishment, since simultaneous pathogen–probiotic exposure can even enhance Salmonella virulence expression under certain conditions [74].

Beyond timing, the hatchery delivery method offers a practical and biologically advantageous means of early microbial intervention. Spray application during incubation provides contact between probiotics and the developing embryo at a stage when the gastrointestinal tract is still sterile and highly receptive to microbial colonization. Beneficial LAB can migrate through the eggshell pores, colonize the embryonic intestine, and establish commensal populations that occupy ecological niches ahead of pathogens [4,5]. This early seeding effect supports competitive exclusion, strengthens the intestinal barrier, and enhances innate immune maturation. Consequently, hatchery-level probiotic use can improve chick viability, reduce horizontal pathogen transmission within flocks, and contribute to overall food safety in poultry production. Overall, the marked reduction in SE colonization in hatchlings, particularly with LP treatment, demonstrates that early application of probiotics to hatching eggs can provide effective, antibiotic-free control of early Salmonella infection. By promoting early gut colonization with beneficial bacteria, these interventions support improved chick health, biosecurity, and reduced pathogen dissemination from hatchery to farm, ultimately enhancing the microbiological safety of poultry products for consumers.

4. Conclusions

The lactic acid bacteria (LAB) strains Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus NRRL-B-548, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus NRRL-B-442, and Lacticaseibacillus paracasei DUP-13076 exhibited strong probiotic properties relevant to poultry production. All three strains survived simulated gastric and intestinal conditions, including exposure to low pH, bile salts, and lysozyme, and adhered efficiently to epithelial cells, suggesting their ability to colonize the avian intestine and competitively exclude pathogens. The strains demonstrated potent antimicrobial activity against multiple Salmonella enterica serovars while remaining sensitive to most antibiotics tested, indicating both functional efficacy and safety for poultry application. In vivo validation through a hatchery spray model confirmed these findings, as application of LR and LP to hatching eggs significantly reduced Salmonella Enteritidis colonization in the liver, spleen, and ceca of hatchlings. These results show that early probiotic exposure can promote beneficial microbiota establishment, enhance resistance to enteric infection, and improve hatchery biosecurity. Collectively, the tested LAB strains represent promising antibiotic-free interventions for strengthening gut health, reducing Salmonella transmission, and improving food safety in poultry production, warranting further evaluation under commercial field conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, all authors; writing—review and editing, M.A.A.; visualization, all authors; supervision, M.A.A.; project administration, M.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the USDA NIFA Hatch project through the Storrs Agricultural Experimentation Station (Award no: CONS00940).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted at the UConn vivarium with approval from the UConn Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC Protocol #A23-003; approval date: 2 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. The genome sequence for LP, LR and LD has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mountzouris, K.C.; Tsirtsikos, P.; Kalamara, E.; Nitsch, S.; Schatzmayr, G.; Fegeros, K. Evaluation of the efficacy of a probiotic containing Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, and Pediococcus strains in promoting broiler performance and modulating cecal microflora composition and metabolic activities. Poult. Sci. 2007, 86, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, N.; Sunder, J.; De, A.K.; Bhattacharya, D.; Joardar, S.N. Probiotics in poultry: A comprehensive review. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2024, 85, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, M.H.; Arsenault, R.J. Gut health: The new paradigm in food animal production. Front. Vet. Sci. 2016, 3, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, G.D.S.; McManus, C.; Vale, I.R.R.; Dos Santos, V.M. Obtaining microbiologically safe hatching eggs from hatcheries: Using essential oils for integrated sanitization strategies. Pathogens 2024, 13, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Ren, Y.; Lu, S.; Reddyvari, R.; Amalaradjou, M.A. Probiotic application to hatching egg surface supports microbiota development and acquisition in broiler embryos and hatchlings. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 105391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosuri, P.; Muttathukonam, S.H.; Reddyvari, R.; Gao, M.; Ren, Y.; Amalaradjou, M.A. Probiotic application reduces Salmonella Enteritidis contamination in layer hatching eggs and embryos. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 105389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Ren, Y.; Lu, S.; Reddyvari, R.; Venkitanarayanan, K.; Amalaradjou, M.A. In ovo probiotic supplementation supports hatchability and improves hatchling quality in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wales, A.; Davies, R. Review of hatchery transmission of bacteria with focus on Salmonella, chick pathogens and antimicrobial resistance. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2020, 76, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; WHO. Probiotics in Food: Health and Nutritional Properties and Guidelines for Evaluation; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- M’hamed, A.C.; Ncib, K.; Merghni, A.; Migaou, M.; Lazreg, H.; Snoussi, M.; Noumi, E.; Ben Mansour, M.; Maaroufi, R.M. Characterization of probiotic properties of Lacticaseibacillus paracasei L2 isolated from a traditional fermented food “Lben”. Life 2022, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Miranda, A.; Melis-Arcos, F.; Garrido, D. Characterization and identification of probiotic features in Lacticaseibacillus paracasei using a comparative genomic analysis approach. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2022, 14, 1211–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuben, R.; Roy, P.; Sarkar, S.; Alam, A.R.U.; Jahid, I. Characterization and evaluation of lactic acid bacteria from indigenous raw milk for potential probiotic properties. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 1223–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyyarikkandy, M.S.; Amalaradjou, M.A. Lactobacillus bulgaricus, L. rhamnosus and L. paracasei attenuate Salmonella Enteritidis, S. Heidelberg and S. Typhimurium colonization and virulence gene expression in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouadio, N.J.; Zady, A.L.O.; Kra, K.A.S.; Diguță, F.C.; Niamke, S.; Matei, F. In vitro probiotic characterization of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum strains isolated from traditional fermented Dockounou paste. Fermentation 2024, 10, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siceloff, A.T.; Waltman, D.; Gunning, C.E.; Nolan, S.P.; Rohani, P.; Shariat, N.W. Longitudinal study highlights patterns of Salmonella serovar co-occurrence and exclusion in commercial poultry production. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1570593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Khowala, S.; Biswas, S. In vitro probiotic characterization of Lactobacillus casei isolated from marine samples. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 73, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, O.K.; Amalaradjou, M.A.R.; Bhunia, A.K. Recombinant probiotic expressing Listeria adhesion protein attenuates Listeria monocytogenes virulence in vitro. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.J.; Lee, N.K.; Paik, H.D. Probiotic characterization of Lactobacillus brevis KU15153 showing antimicrobial and antioxidant effects isolated from kimchi. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 28, 1521–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willer, T.; Han, Z.; Pielsticker, C.; Rautenschlein, S. In vitro investigations on interference of selected probiotic candidates with Campylobacter jejuni adhesion and invasion of primary chicken cecal and Caco-2 cells. Gut Pathog. 2024, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghiselli, F.; Rossi, B.; Piva, A.; Grilli, E. Assessing intestinal health: In vitro and ex vivo gut barrier models of farm animals—Benefits and limitations. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 723387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal-McKinney, J.M.; Lu, X.; Duong, T.; Larson, C.L.; Call, D.R.; Shah, D.H.; Konkel, M.E. Production of organic acids by probiotic lactobacilli can be used to reduce pathogen load in poultry. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, M.G.; El Sohaimy, S.A.; El-Sahn, M.A.; Youssef, M.M. Screening of isolated potential probiotic lactic acid bacteria for cholesterol-lowering property and bile-salt hydrolase activity. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2016, 61, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, H. Effects of dietary probiotic (Bacillus subtilis) supplementation on carcass traits, meat quality, amino acid, and fatty acid profile of broiler chickens. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 767802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.A.; Chang, H.C. Cholesterol-lowering effects of a putative probiotic strain Lactobacillus plantarum EM isolated from kimchi. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed (FEEDAP). Guidance on the assessment of bacterial susceptibility to antimicrobials of human and veterinary importance. EFSA J. 2012, 10, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefańska, I.; Kwiecień, E.; Jóźwiak-Piasecka, K.; Garbowska, M.; Binek, M.; Rzewuska, M. Antimicrobial susceptibility of lactic acid bacteria strains of potential use as feed additives—The basic safety and usefulness criterion. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 687071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prjibelski, A.; Antipov, D.; Meleshko, D.; Lapidus, A.; Korobeynikov, A. Using SPAdes de novo assembler. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2020, 70, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, R.K.; Bartels, D.; Best, A.A.; De Jongh, M.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Formsma, K.; Gerdes, S.; Glass, E.M.; Kubal, M.; et al. The RAST server: Rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyaya, I.; Yin, H.; Nair, M.S.; Chen, C.; Upadhyay, A.; Darre, M.J.; Venkitanarayanan, K. Efficacy of fumigation with trans-cinnamaldehyde and eugenol in reducing Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis on embryonated egg shells. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 1685–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adame, M.M.; Ameha, N. Review on egg handling and management of incubation and hatchery environment. Asian J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 16, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollanoor Johny, A.; Upadhyay, A.; Baskaran, S.A.; Upadhyaya, I.; Mooyottu, S.; Mishra, N.; Darre, M.J.; Khan, M.I.; Donoghue, A.M.; Donoghue, D.J.; et al. Effect of therapeutic supplementation of the plant compounds trans-cinnamaldehyde and eugenol on Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis colonization in broiler chickens. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2012, 21, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, W.H.; Kouadio, N.G.R.; Camara, F.; Diguță, C.; Matei, F. Functional properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in Ivory Coast. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diguță, C.F.; Nițoi, G.D.; Matei, F.; Luță, G.; Cornea, C.P. The biotechnological potential of Pediococcus spp. isolated from Kombucha microbial consortium. Foods 2020, 9, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajoka, M.S.R.; Mehwish, H.M.; Siddiq, M.; Haobin, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yan, L.; Shao, D.; Xu, X.; Shi, J. Identification, characterization, and probiotic potential of Lactobacillus rhamnosus isolated from human milk. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 84, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. Nutrient Requirements of Poultry, 9th ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Menconi, A.; Kallapura, G.; Latorre, J.D.; Morgan, M.J.; Pumford, N.R.; Hargis, B.M.; Tellez, G. Identification and characterization of lactic acid bacteria in a commercial probiotic culture. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 2014, 33, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, F.; Muccee, F.; Shahab, A.; Safi, S.Z.; Alomar, S.Y.; Qadeer, A. Isolation and in vitro assessment of chicken gut microbes for probiotic potential. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1278439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabikhi, L.; Babu, R.; Thompkinson, D.K.; Kapila, S. Resistance of microencapsulated Lactobacillus acidophilus LA1 to processing treatments and simulated gut conditions. Food Bioproc. Technol. 2010, 3, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fguiri, I.; Ziadi, M.; Atigui, M.; Ayeb, N.; Arroum, S.; Assadi, M.; Khorchani, T. Isolation and characterisation of lactic acid bacteria strains from raw camel milk for potential use in the production of fermented Tunisian dairy products. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2016, 69, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Adams, M.B.; Burke, C.M.; Bolch, C.J.S. Screening and activity of potential gastrointestinal probiotic lactic acid bacteria against Yersinia ruckeri O1b. J. Fish Dis. 2023, 46, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristoffersen, S.M.; Ravnum, S.; Tourasse, N.J.; Økstad, O.A.; Kolstø, A.-B.; Davies, W. Low concentrations of bile salts induce stress responses and reduce motility in Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 5302–5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, L.; Pan, C.; Huang, Y. Probiotic properties of Lactobacillus strains isolated from Tibetan kefir grains. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succi, M.; Tremonte, P.; Reale, A.; Sorrentino, E.; Grazia, L.; Pacifico, S.; Coppola, R. Bile-salt and acid tolerance of Lactobacillus rhamnosus strains isolated from Parmigiano Reggiano cheese. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2005, 244, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, I.; Lessire, M.; Mallet, S.; Guillot, J.F. Microflora of the digestive tract: Critical factors and consequences for poultry. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2006, 62, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svihus, B. Function of the digestive system. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2014, 23, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Qian, B.; Xia, B.; Zhuan, Y.; Yao, Y.; Gan, R.; Zhang, J. Screening of lactic acid bacteria isolated from fermented Cornus officinalis fruits for probiotic potential. J. Food Saf. 2018, 38, e12565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Esmail, G.A.; Alzeer, A.F.; Arasu, M.V.; Vijayaraghavan, P.; Choi, K.C.; Al-Dhabi, N.A. Probiotic characteristics of Lactobacillus strains isolated from cheese and their antibacterial properties against gastrointestinal pathogens. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 3505–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirayama, K.; Rafter, J. The role of probiotic bacteria in cancer prevention. Microb. Infect. 2000, 2, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotzamanidis, C.; Kourelis, A.; Litopoulou-Tzanetaki, E.; Tzanetakis, N.; Yiangou, M. Evaluation of adhesion capacity, cell surface traits and immunomodulatory activity of presumptive probiotic Lactobacillus strains. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 140, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillinger, U.; Guigas, C.; Holzapfel, W.H. In vitro adherence and other properties of lactobacilli used in probiotic yoghurt-like products. Int. Dairy J. 2005, 15, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, S.; Furtado, D.; Saad, S.; Tome, E.; Franco, B. Potential beneficial properties of bacteriocin-producing lactic acid bacteria isolated from smoked salmon. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 110, 971–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadishkumar, V.; Jeevaratnam, K. In vitro probiotic evaluation of potential antioxidant lactic acid bacteria isolated from idli batter fermented with Piper betle leaves. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniyandi, S.A.; Damodharan, K.; Suh, J.W.; Yang, S.H. Probiotic characterization of cholesterol-lowering Lactobacillus fermentum MJM60397. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2020, 12, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, K.; Abdullah, N.; Wong, M.C.; Karuthan, C.; Ho, Y.W. Bile-salt deconjugation and cholesterol removal from media by lactobacilli used as probiotics in chickens. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Yoon, H.; Ji, Y.; Kim, H.; Park, H.; Lee, J.; Shin, H.; Holzapfel, W. Functional properties of Lactobacillus strains isolated from kimchi. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 145, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lye, H.; Rahmat-Ali, G.R.; Liong, M. Mechanisms of cholesterol removal by lactobacilli under conditions that mimic the human gastrointestinal tract. Int. Dairy J. 2010, 20, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalavathy, R.; Abdullah, N.; Jalaludin, S.; Ho, Y.W. Effects of Lactobacillus cultures on growth performance, abdominal fat deposition, serum lipids and organ weights of broiler chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2003, 44, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushboo; Karnwal, A.; Malik, T. Characterization and selection of probiotic lactic acid bacteria from different dietary sources for development of functional foods. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1170725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Arlindo, S.; Böhme, K.; Fernández-No, C.; Calo-Mata, P.; Barros-Velázquez, J. Molecular and probiotic characterization of bacteriocin-producing Enterococcus faecium strains isolated from nonfermented animal foods. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 107, 1392–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives. Evaluation of Certain Mycotoxins in Food: Fifty-Sixth Report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Charteris, W.P.; Kelly, P.M.; Morelli, L.; Collins, J.K. Quality control Lactobacillus strains for use with the API 50 CH and API ZYM systems at 37 °C. J. Basic Microbiol. 2001, 41, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, D. Assessing the safety and probiotic characteristics of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus X253 via complete genome and phenotype analysis. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcotte, H.; Andersen, K.K.; Lin, Y.; Zuo, F.; Zeng, Z.; Larsson, P.G.; Brandsborg, E.; Brønstad, G.; Hammarström, L. Characterization and complete genome sequences of Lactobacillus rhamnosus DSM 14870 and L. gasseri DSM 14869 contained in the EcoVag® probiotic vaginal capsules. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 205, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, M.I.; Macklaim, J.M.; Wuyts, S.; Verhoeven, T.; Vanderleyden, J.; Gloor, G.B.; Lebeer, S.; Reid, G. Comparative genomic and phenotypic analysis of the vaginal probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyyarikkandy, M.S.; Alqahtani, F.H.; Mandoiu, I.; Amalaradjou, M.A. Draft genome sequence of Lactobacillus rhamnosus NRRL B-442, a potential probiotic strain. Genome Announc. 2018, 6, e00046-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, R.; Torres-Miranda, A.; Orellana, G.; Garrido, D. Comparative genomic analysis of novel Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum strains reveals functional divergence in the human gut microbiota. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyyarikkandy, M.S.; Alqahtani, F.H.; Mandoiu, I.; Amalaradjou, M.A. Draft genome sequence of Lactobacillus paracasei DUP 13076, which exhibits potent antipathogenic effects against Salmonella enterica serovars Enteritidis, Typhimurium, and Heidelberg. Genome Announc. 2018, 6, e00065-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jesus, L.C.L.; Drumond, M.M.; Aburjaile, F.F.; Sousa, T.d.J.; Coelho-Rocha, N.D.; Profeta, R.; Brenig, B.; Mancha-Agresti, P.; Azevedo, V. Probiogenomics of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis CIDCA 133: In silico, in vitro, and in vivo approaches. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhl, G.C.; Mazzon, R.R.; Duarte, R.T.D.; Lindner, J.D.D. Draft genome sequence of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus LBP UFSC 2230: A tool for preliminary identification of enzymes involved in CLA metabolism. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2021, 52, 1557–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Closs, G., Jr.; Bhandari, M.; Helmy, Y.A.; Kathayat, D.; Lokesh, D.; Jung, K.; Suazo, I.D.; Srivastava, V.; Deblais, L.; Rajashekara, G. The probiotic Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG supplementation reduces Salmonella load and modulates growth, intestinal morphology, gut microbiota, and immune responses in chickens. Infect. Immun. 2025, 93, e00420-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Peng, X.; Zhou, X.; Jin, X.; Siddique, A.; Yao, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Yue, M. Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus P118 enhances heat tolerance to Salmonella infection by promoting microbe-derived indole metabolites. eLife 2025, 13, RP101198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, P.; Lee, C.H.; Cosby, D.E.; Cox, N.A.; Kim, W.K. Effect of probiotics on fecal excretion, colonization in internal organs and immune gene expression in the ileum of laying hens challenged with Salmonella Enteritidis. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.; Weimer, B.C.; Gann, R.; Desai, P.T.; Shah, J.D. The Yin and Yang of pathogens and probiotics: Interplay between Salmonella enterica sv. Typhimurium and Bifidobacterium infantis during co-infection. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1387498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.