Abstract

Campylobacter jejuni (CJ) is a major foodborne pathogen with chickens serving as the reservoir host. This study investigated the efficacy of linalool, a Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) phytochemical, as an in-feed intervention to reduce CJ colonization in broiler chickens. Three independent trials were conducted using 212-day-old Cornish Cross chicks per trial. Of these, 192 birds were randomly allocated to eight treatment groups (n = 24/group): negative control, linalool-only controls (1.0%, 1.5%, and 1.8%), positive control (CJ only), and CJ-challenged birds supplemented with linalool at 1.0%, 1.5%, or 1.8%. Linalool supplementation commenced on day 0, and birds were orally challenged with approximately 9 log10 CFU of CJ on day 7. Cecal CJ populations were enumerated on days 14, 24, and 34. Positive control birds harbored approximately 6–7 log CFU/g of CJ in the ceca, whereas linalool supplementation significantly reduced CJ colonization (p < 0.05) by 2–3 log on day 14 and by 3–5 log on days 24 and 34. No adverse effects of linalool were observed on body weight, feed intake, or feed conversion ratio. Additionally, RT-qPCR analysis demonstrated downregulation (p < 0.0001) of key CJ virulence and colonization-associated genes. These findings suggest that dietary linalool is a potential strategy to reduce CJ colonization in broiler chickens; however, large-scale studies under field conditions are warranted.

1. Introduction

Poultry and poultry meat are widely regarded as the primary sources of human campylobacteriosis [1,2,3]. Each year, an estimated 1.5 million people in the U.S. fall ill due to Campylobacter infection. Most of these cases are caused by Campylobacter jejuni (CJ), the primary bacterial agent responsible for diarrheal illness in the country. Campylobacter infection leads to acute gastrointestinal illness in humans and is regarded as a risk factor for developing Guillain-Barré syndrome [4].

C. jejuni primarily colonizes the ceca of poultry, from where it utilizes L-fucose, a major carbohydrate present in chicken cecal mucus [5]. This enables the bacteria to survive, multiply, and help in its selective colonization within the birds [5,6]. The poultry carcass potentially gets cross-contaminated at the processing facility due to the spillage of intestinal contents. Handling and consuming improperly cooked poultry products account for the majority of CJ infections. Colonization of the ceca of chickens by CJ generally happens between 2 and 3 weeks of age and reaches around 1 × 109 CFU/g in the ceca at market age [7,8]. Horizontal transmission within the flock occurs predominantly via shedding birds and contaminated litter. Feed, water and other sources can act as sources of transmission. CJ is also reported to have a high within-flock prevalence [9,10].

USDA-FSIS emphasizes that reducing or eliminating Campylobacter on incoming birds at slaughter establishments can significantly lower contamination of finished products and enhance the establishment’s ability to meet the FSIS performance standards for Campylobacter [11]. Quantitative microbiological risk assessment demonstrated that achieving a 3.0-log reduction in Campylobacter populations in chicken intestines at the processing stage has the potential to lower the incidence of human infection by up to 90% [12]. Therefore, interventional strategies implemented at the farms play a major role in delivering microbiologically safer products [10,11] and become a key strategic approach for decreasing disease outbreaks in consumers.

The use of phytochemicals, including essential oils, as a means to control Campylobacter in chickens represents a promising approach [13,14]. These natural substances comprise secondary components, such as terpenoids, phenolics, glycosides, alkaloids, flavonoids, and glucosinolates, known to exhibit antimicrobial properties through multiple mechanisms, such as disruption of bacterial membranes and inhibition of pathogen colonization [15,16,17]. With the poultry industry increasingly prioritizing antibiotic residue-free production and seeking alternatives to synthetic chemicals and antibiotics, there is a growing imperative to investigate and identify novel phytochemicals as effective strategies for pathogen control.

Linalool is a naturally occurring monoterpene alcohol widely distributed in aromatic plants such as lavender, basil, and coriander [18,19,20]. It is classified as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) by the U.S. FDA, supporting its use in foods, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. The broad-spectrum antibacterial activity of linalool has been demonstrated in vitro against multiple foodborne pathogens, including Salmonella spp., Staphylococcus aureus, and Listeria monocytogenes [21,22,23]. It was demonstrated that linalool could be safely added to chicken feed at concentrations up to 2% without significant negative effects on serum chemistry, gross pathology, or feed conversion [24]. The objective of this research was to determine the efficacy of linalool as a prophylactic in-feed supplement to reduce the colonization of CJ in broiler chickens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant-Derived Antimicrobial

Linalool ((±)-3,7-dimethyl-1,6-octadien-3-ol, (±)-3,7-dimethyl-3-hydroxy-1,6 octadiene, ≥97%, W263508 Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used.

2.2. Experimental Birds and Housing

Day-old commercial Cornish Cross chicks (Myers Poultry Farm, South Fork, PA, USA) were housed in the University of Connecticut’s Spring Hill Laboratory (SHL) poultry facility under standardized husbandry conditions. Birds were maintained in pens measuring 6′1″ × 8′8″ (53.68 ft2), with stocking density, sanitation, and environmental parameters following Animal Care Services SOP 6-005. Pens were bedded with pine/aspen shavings (G.M. Thompson & Sons, Mansfield, CT, USA), and standard broiler feed and water were provided ad libitum in accordance with SOP 1-006. Room temperature, humidity, and ventilation were maintained as specified in SOP 6-005, including age-appropriate brooding temperatures and a target temperature range of 67.5–73.5 °F for older birds. A 14 h light: 10 h dark lighting program was used throughout the study.

Chicks were manually randomized into pens and treatment groups by assigning birds sequentially to pens in a rotating pattern to ensure unbiased distribution. All procedures were approved by the University of Connecticut Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC Protocol A21-055).

2.3. Bacterial Strains and Dosing

Four CJ isolates (LN1, LN2, LN3 and LN4) from our laboratory culture collection were used in the study. Lawn cultures of all four isolates of CJ were prepared on CRA (Campylobacter Rapid Agar, BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA), and the plates were incubated at 42 °C for 24 h under microaerophilic conditions (85% N2, 10% CO2, 5% O2). The cultures were transferred to 30 mL of buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2), subjected to centrifugation at 3000× g for 15 min, and the pellet was washed and resuspended in 25 mL of PBS.

2.4. Experimental Design

In each of the three trials, a total of 212-day-old Cornish Cross broiler chicks (unsexed) were used. Of these, 192 birds were randomly allocated into eight experimental groups comprising 24 birds each. The remaining 20 birds were used to check CJ colonization efficiency on day 2 post-challenge. The groups included a negative control (no CJ, no linalool), compound control (no CJ, fed with 1%, 1.5%, 1.8% [vol/wt] linalool), positive control (CJ, no linalool), and linalool treatments (CJ, fed with 1%, 1.5%, 1.8% linalool). A standard commercial broiler starter–grower feed (feed composition listed in Supplementary Table S1) was provided to all treatment groups, and linalool was supplemented daily by measuring the required amount of feed and mixing the corresponding volume of linalool (vol/wt) to achieve the designated inclusion levels. Linalool supplementation started on day 0 and extended to day 34, and birds were inoculated with ~9.0 log10 CFU of a four-strain mixture of CJ on day 7. High-dose challenge model for CJ was used to ensure consistent colonization, which is within the standard range used in poultry challenge studies. Campylobacter cecal colonization was ascertained (n = 20 chicks/experiment) after 48 h. Eight birds from each treatment group were euthanized by using CO2 inhalation on days 14, 24 and 34, and Campylobacter population in the cecum was enumerated on CRA with incubation at 42 °C for 48 h under microaerophilic conditions. The weekly feed consumption, body weight, and feed conversion ratio (FCR) per bird in each group were also determined. FCR was determined on days 14, 24, and 34 using cumulative feed intake (FI) and cumulative body-weight gain (BWG) [25,26]. Cumulative FI per bird was calculated from pen-level feed disappearance adjusted for the number of live birds. Cumulative BWG was computed as the change in mean body weight from day 0.

2.5. Determination of CJ in Organs

Ceca from each bird were collected in separate sterile whirlpak bags containing 10 mL of PBS. The weighed samples were processed with a tissue homogenizer (Tissue Master, Omni International, Marietta, GA, USA) and diluted 10-fold in sterile PBS. A 0.1-mL portion of the appropriate dilutions was surface plated on duplicate CRA plates. The colonies were enumerated after incubation at 42 °C for 48 h under microaerophilic conditions [25,27]. When colonies were not detected after direct plating, samples were tested for surviving cells by enrichment for 48 h at 42 °C in 100 mL of Campylobacter enrichment broth (CEB; International Diagnostics Group plc, Lancaster, UK) followed by streaking on CRA plates.

2.6. Determination of Sub-Inhibitory Concentration (SIC) of Linalool

The SIC of linalool against CJ was determined in sterile 24-well plates containing Mueller-Hinton broth (1 mL/well) inoculated with ~6.0 log CFU of CJ using the protocol described by [28]. Linalool was added at 1–10 µL in 0.5 µL increments, and plates were incubated at 42 °C for 24 h under microaerophilic conditions. Bacterial counts were enumerated on duplicate CRA plates. The SIC was defined as the highest concentration of linalool that did not significantly reduce bacterial growth after 24 h compared with the untreated control (p > 0.05). All treatments were triplicated, and the experiment was repeated three times. The concentration–growth response data are presented in Supplementary Figures S1 and S2.

2.7. RNA Isolation and RT-q-PCR Analysis

CJ cultures were grown with or without the SIC of linalool (1.62 mM) at 42 °C for 16 h under microaerophilic conditions. Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA integrity and purity were confirmed by NanoDrop spectrophotometry (A260/280 = 1.9–2.1), and 1 µg of RNA was used for cDNA synthesis with the SuperScript IV reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). RT-qPCR was performed on an Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (StepOne Software v2.3) using SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Primers for all target genes (cadF, ciaB, flaA, cdtA, cdtB, cdtC) and the endogenous control (16S rRNA), along with their amplicon sizes, are listed in Table 1. Relative transcript abundance was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method, with 16S rRNA as the reference gene [29,30]. All samples were run in triplicate, and differences in gene expression between untreated and linalool-treated cultures were interpreted as previously described [31].

Table 1.

Genes selected for the Campylobacter jejuni (CJ) transcriptional analysis.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

For all in vivo measurements, the pen was considered the experimental unit. At each sampling time point (days 14, 24, and 34), eight birds were selected from the same treatment pen; bird-level observations were therefore treated as subsamples and were averaged to generate one pen-level value per treatment × day. The experiment was repeated across three independent trials, yielding three biological replicates for each treatment × day combination. Data from the three trials were pooled after confirming that no trial × treatment interaction was present.

Cecal Campylobacter jejuni counts, body weight, feed intake, and feed conversion ratio (FCR) were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA in GraphPad Prism 10, with treatment and sampling day specified as fixed factors. When significant main or interaction effects were detected, differences among treatment × day means were evaluated using Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Model assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were verified prior to analysis, and statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

For the RT-qPCR analysis, each assay was performed in triplicate. ΔCq values (Cq_{target} − Cq_{reference}) were used for statistical testing, and relative fold-change values were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method, with the untreated control as the calibrator and 16S rRNA as the reference gene. Differences among gene-expression means were evaluated using two-way ANOVA in GraphPad Prism 10, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05)

3. Results

3.1. Cecal Colonization

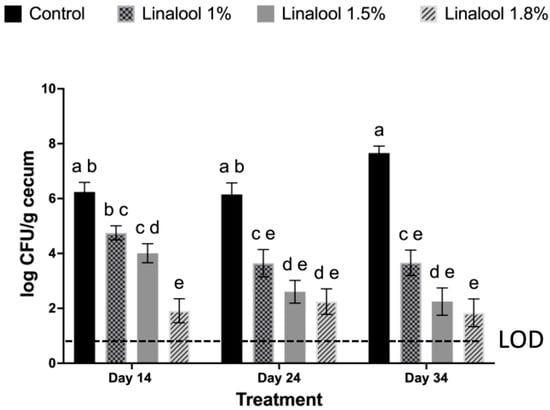

C. jejuni was not detected in the unchallenged control groups (negative control and linalool control), confirming that these birds remained free of CJ infection throughout the trial period. As illustrated in Figure 1, CJ was recovered at approximately 6.5–7.0 log CFU/g cecum from positive control birds on days 14, 24, and 34. In contrast, birds receiving dietary supplementation with linalool exhibited significantly reduced CJ counts in cecal samples at all tested concentrations (1%, 1.5%, and 1.8%) (p < 0.05). On day 14, linalool-treated birds (1%, 1.5%, and 1.8%) exhibited significantly lower CJ counts compared to the positive control (p < 0.05), with the greatest reduction observed in the 1.8% group, yielding less than 2.0 log CFU/g cecum. By day 24, CJ levels in linalool-supplemented birds remained significantly reduced across all concentrations, ranging from ~2.5 to 3.8 log CFU/g cecum, whereas the positive control birds maintained counts near 6.5 log CFU/g cecum. On day 34, the reductions were most pronounced, birds receiving 1.5% and 1.8% linalool yielded cecal CJ levels of approximately 1.0–2.0 log CFU/g cecum, representing a > 4-log reduction compared to the positive control. No adverse effect on body weight gain, weekly feed intake, or FCR were observed between linalool treated and control birds (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Effect of linalool supplementation on cecal colonization of Campylobacter jejuni (CJ) in chickens at days 14, 24, and 34. Values represent pen-level means (N = 3 pens per treatment × day), with error bars indicating the SEM. Bird-level observations (n = 8 birds per pen) were averaged to obtain each pen value. Within each sampling day, means with different letters (a, b, c, d, e) differ significantly between the treatments (p < 0.05). Enrichment negative samples for CJ were assigned a value of 0. Enrichment positive samples were assigned a value of 0.9 log CFU/g cecum. The limit of detection (LOD) is given after enrichment.

Table 2.

Body weight gain (BWG), cumulative feed intake (FI), and feed conversion ratio (FCR) of chickens fed with control and linalool diets under Campylobacter jejuni (CJ) challenge on days 14, 24 and 34.

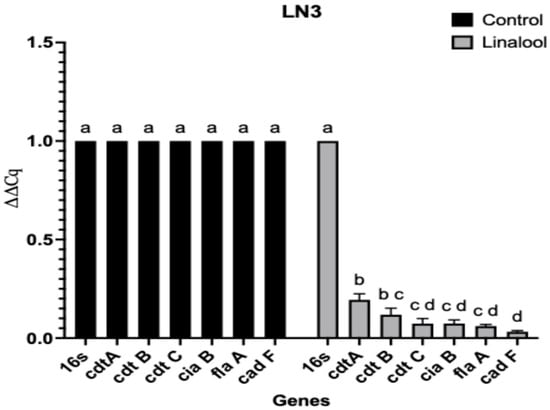

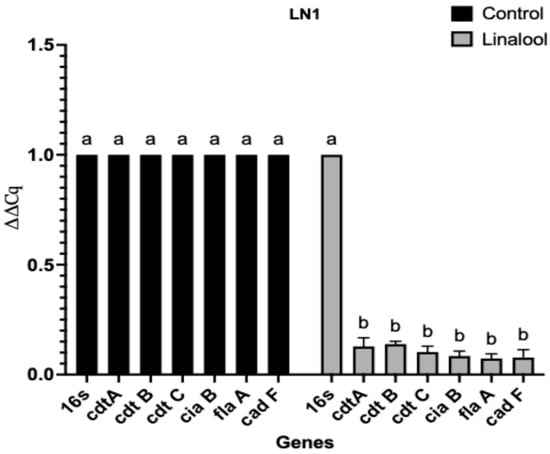

3.2. Effect of Linalool on Transcription of Colonization and Virulence Genes in CJ

The SIC of linalool against CJ was determined as 1.62 mM. Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis revealed that the SIC of linalool significantly downregulated the transcription of key virulence and colonization-associated genes (Table 1) in both CJ isolates (p < 0.0001) (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The targeted genes included those involved in bacterial adhesion, invasion, motility, and host cell dissemination and immune evasion. Among the two isolates, the LN3 isolate demonstrated a greater reduction in fold changes in the expression of genes compared to the LN1 isolate following linalool treatment.

Figure 2.

Effect of linalool on the transcription of selected CJ virulence and colonization genes. on LN3 isolate. Each experiment was performed with three biological replicates and three technical replicates per gene and repeated 3 times. Means with different letters (a, b, c, d) differ significantly between the treatments within each experiment (p < 0.0001). The differences between the means were compared at a significance level of 5%. Relative expression values were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method with 16S rRNA as the reference gene. Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 3.

Effect of linalool on the transcription of selected CJ virulence and colonization genes. on LN1 isolate. Each experiment was performed with three biological replicates and three technical replicates per gene and repeated 3 times. Means with different letters (a, b) differ significantly between the treatments within each experiment (p < 0.0001). The differences between the means were compared at a significance level of 5%. Relative expression values were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method with 16S rRNA as the reference gene. Error bars represent SEM.

4. Discussion

The current study demonstrates the significant antimicrobial efficacy of dietary linalool supplementation against CJ colonization in broiler chickens. Birds receiving 1%, 1.5%, and 1.8% linalool exhibited substantial and statistically significant reductions in cecal CJ loads across all time points when compared to the positive control group (p < 0.05). Importantly, these reductions were achieved without any adverse effects on growth performance metrics, including body weight gain, feed intake, and FCR, indicating the potential of linalool as a safe and effective feed additive.

In our study, linalool supplementation at 1.8% yielded the most profound reduction in CJ colonization, with counts falling below 2.0 log CFU/g cecum as early as day 14, compared to 6.5–7.0 log CFU/g cecum in the positive control group. This greater than 4-log reduction observed by day 34 (1.0–2.0 log CFU/g cecum) is particularly notable, as even a 2-log reduction in cecal Campylobacter has been estimated to significantly lower the public health risk associated with poultry products [32,33]. The sustained suppression of CJ in chickens throughout the trial period suggests that linalool could potentially be used as an effective feed supplement to control the bacterium in birds before slaughter.

Importantly, no adverse effects were observed in body weight gain, feed intake, or FCR between linalool-treated and control birds, underscoring the absence of detrimental effects on productivity (Table 2). This is critical for commercial application, as any antimicrobial strategy must maintain or enhance production efficiency to be economically viable. Previous studies using essential oil compounds in poultry diets have reported variable impacts on performance [34], likely due to differences in dose, compound stability, and interaction with other dietary components. In our previous work, histopathological evaluation of liver and intestinal tissues in chickens also revealed no adverse microscopic changes attributable to linalool [35].

In CJ, linalool reduced the expression of cdtA, cdtB, and cdtC, which encode the cytolethal distending toxin (CDT); the invasion gene ciaB, which is critical for host cell invasion; the adhesion and invasion gene cadF; and the motility-associated gene flaA, involved in flagella formation [31,36,37]. When integrated with the in vivo data, the suppression of cadF, ciaB, and flaA provides a plausible explanation for the decreased cecal colonization seen in treated birds. Reduced cadF and ciaB expression is expected to limit adhesion to and invasion of intestinal epithelial cells [38,39], while diminished flaA expression impairs flagellar assembly and motility [40,41], thereby restricting the ability of CJ to reach and persist in its preferred gastrointestinal niches. These results suggest that linalool exerts its inhibitory effects on CJ, at least in part, by modulating gene expression involved in bacterial colonization and virulence, thereby potentially reducing the ability of CJ to colonize in the host gastrointestinal tract. Furthermore, the SIC experiments demonstrated that linalool does not inhibit growth at 1.62 mM, confirming that the transcriptional effects occur at non-bactericidal concentrations and therefore reflect targeted physiological responses rather than generalized growth suppression.

Additionally, these findings are supported by the antibacterial mechanisms of linalool involve disruption of bacterial cell membranes, as previously proposed for monoterpenes [42,43,44]. Linalool has been shown to increase membrane permeability, cause leakage of intracellular contents, and impair energy metabolism in bacteria [21,43].

Although this study demonstrates the potential efficacy of dietary linalool in reducing CJ carriage in broiler chickens, a few limitations should be considered. First, the trials were conducted under controlled experimental conditions using a single broiler genotype and may not fully reflect commercial or field production environments, where factors such as litter management, microbiome complexity, and environmental stressors could influence outcomes. Second, the study focused primarily on cecal colonization and did not evaluate CJ carcass contamination, which is a critical endpoint for assessing food safety risk reduction. Additionally, while growth performance was unaffected, the longer-term impacts of linalool supplementation on immune responses and meat quality needed to be assessed. Finally, the economic feasibility and scalability of incorporating linalool at the tested inclusion rates in commercial poultry diets warrant further investigation. Despite these limitations, it is highlighted that this study constitutes the first report on the efficacy of linalool as a dietary strategy to reduce CJ in broiler chickens. Our future investigations will determine linalool’s efficacy in a large bird population under field conditions, in addition to assessing nutritional status and growth performance of birds, and carcass characteristics of meat from linalool supplemented birds.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings of this study support the potential application of linalool as a natural, plant-derived antimicrobial feed additive that can significantly reduce CJ colonization in broilers without compromising performance. However, large-scale follow-up studies under field conditions are needed to confirm linalool’s long-term efficacy and practicality as a sustainable intervention for broiler production.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/poultry5010007/s1, Figure S1: Growth curves of Campylobacter jejuni LN1 isolate exposed to increasing concentrations of linalool for determination of the sub-inhibitory concentration (SIC). Figure S2: Growth curves of Campylobacter jejuni LN3 isolate exposed to increasing concentrations of linalool for determination of the sub-inhibitory concentration (SIC). Table S1: Composition and guaranteed analysis of the commercial starter–grower feed used in this study (Home Fresh Multi-Flock Chick N Game Starter/Grower 22 Pellet, Blue Seal.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.V.; methodology, L.S.V. and K.V.; software, L.S.V.; validation, L.S.V., D.J. and K.V.; formal analysis, L.S.V.; investigation, L.S.V., P.G.V. and D.J.; resources, K.V.; data curation, L.S.V.; writing—original draft preparation, L.S.V.; writing—review and editing, L.S.V. and K.V.; visualization, L.S.V.; supervision, K.V.; project administration, K.V.; funding acquisition, K.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a USDA-Sustainable Agricultural Systems grant (2020-69012-31823) awarded to Kumar Venkitanarayanan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Connecticut (protocol code A21-055, approved on 6 December 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article or Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CJ | Campylobacter jejuni |

| CRA | Campylobacter Rapid Agar |

| FCR | Feed Conversion Ratio |

| IACUC | Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee |

| CEB | Campylobacter enrichment broth |

| SIC | Sub-inhibitory concentration |

| CDT | Cytolethal distending toxin |

References

- Alter, T.; Weber, R.M.; Hamedy, A.; Glünder, G. Carry-over of Thermophilic Campylobacter spp. between Sequential and Adjacent Poultry Flocks. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 147, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, I.H.; Richardson, N.J.; Bokkenheuser, V.D. Broiler Chickens as Potential Source of Campylobacter Infections in Humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1980, 11, 508–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaakoush, N.O.; Castaño-Rodríguez, N.; Mitchell, H.M.; Man, S.M. Global Epidemiology of Campylobacter Infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 687–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, M.; Koga, M.; Yokoyama, K.; Yuki, N. Epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni Isolated from Patients with Guillain-Barré and Fisher Syndromes in Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl, M.; Friis, L.M.; Nothaft, H.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Szymanski, C.M.; Stintzi, A. L-Fucose Utilization Provides Campylobacter jejuni with a Competitive Advantage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 7194–7199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraoka, W.T.; Zhang, Q. Phenotypic and Genotypic Evidence for L-Fucose Utilization by Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielsticker, C.; Glünder, G.; Rautenschlein, S. Colonization Properties of Campylobacter jejuni in Chickens. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2012, 2, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, B.L.; Guerry, P.; Poly, F. Global Distribution of Campylobacter jejuni Penner Serotypes: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hakeem, W.G.; Fathima, S.; Shanmugasundaram, R.; Selvaraj, R.K. Campylobacter jejuni in Poultry: Pathogenesis and Control Strategies. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gerwe, T.; Miflin, J.K.; Templeton, J.M.; Bouma, A.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Jacobs-Reitsma, W.F.; Stegeman, A.; Klinkenberg, D. Quantifying Transmission of Campylobacter jejuni in Commercial Broiler Flocks. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS). FSIS Guideline for Controlling Campylobacter in Raw Poultry; USDA-FSIS: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Romero-Barrios, P.; Hempen, M.; Messens, W.; Stella, P.; Hugas, M. Quantitative Microbiological Risk Assessment (QMRA) of Food-Borne Zoonoses at the European Level. Food Control 2013, 29, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Arsi, K.; Wagle, B.R.; Upadhyaya, I.; Shrestha, S.; Donoghue, A.M.; Donoghue, D.J. Trans-Cinnamaldehyde, Carvacrol, and Eugenol Reduce Campylobacter jejuni Colonization Factors and Expression of Virulence Genes In Vitro. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagle, B.R.; Donoghue, A.M.; Shrestha, S.; Upadhyaya, I.; Arsi, K.; Gupta, A.; Liyanage, R.; Rath, N.C.; Donoghue, D.J.; Upadhyay, A. Carvacrol Attenuates Campylobacter jejuni Colonization Factors and Proteome Critical for Persistence in the Chicken Gut. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 4566–4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Sanchez, S.; D’Souza, D.; Biswas, D.; Hanning, I. Botanical Alternatives to Antibiotics for Use in Organic Poultry Production1. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 1419–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Upadhyaya, I.; Kollanoor-Johny, A.; Venkitanarayanan, K. Combating Pathogenic Microorganisms Using Plant-Derived Antimicrobials: A Minireview of the Mechanistic Basis. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, e761741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mnaser, A.; Dakheel, M.; Alkandari, F.; Woodward, M. Polyphenolic Phytochemicals as Natural Feed Additives to Control Bacterial Pathogens in the Chicken Gut. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aelenei, P.; Rimbu, C.M.; Guguianu, E.; Dimitriu, G.; Aprotosoaie, A.C.; Brebu, M.; Horhogea, C.E.; Miron, A. Coriander Essential Oil and Linalool—Interactions with Antibiotics against Gram-positive and Gram-negative Bacteria. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 68, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprotosoaie, A.C.; Hăncianu, M.; Costache, I.-I.; Miron, A. Linalool: A Review on a Key Odorant Molecule with Valuable Biological Properties. Flavour Fragr. J. 2014, 29, 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Mishra, A. Linalool: Therapeutic Indication and Their Multifaceted Biomedical Applications. Drug Res. 2024, 74, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Chen, W.; Chen, H.; Zhong, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Chen, W. Antibacterial Mechanism of Linalool against L. Monocytogenes, a Metabolomic Study. Food Control 2022, 132, 108533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soković, M.; Glamočlija, J.; Marin, P.D.; Brkić, D.; Griensven, L.J.L.D. van Antibacterial Effects of the Essential Oils of Commonly Consumed Medicinal Herbs Using an In Vitro Model. Molecules 2010, 15, 7532–7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zengin, H.; Baysal, A.H. Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activity of Essential Oil Terpenes against Pathogenic and Spoilage-Forming Bacteria and Cell Structure-Activity Relationships Evaluated by SEM Microscopy. Molecules 2014, 19, 17773–17798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beier, R.C.; Byrd, J.A.; Kubena, L.F.; Hume, M.E.; McReynolds, J.L.; Anderson, R.C.; Nisbet, D.J. Evaluation of Linalool, a Natural Antimicrobial and Insecticidal Essential Oil from Basil: Effects on Poultry1. Poult. Sci. 2014, 93, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de los Santos, F.S.; Hume, M.; Venkitanarayanan, K.; Donoghue, A.M.; Hanning, I.; Slavik, M.F.; Aguiar, V.F.; Metcalf, J.H.; Reyes-Herrera, I.; Blore, P.J.; et al. Caprylic Acid Reduces Enteric Campylobacter Colonization in Market-Aged Broiler Chickens but Does Not Appear To Alter Cecal Microbial Populations. J. Food Prot. 2010, 73, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurekci, C.; Al Jassim, R.; Hassan, E.; Bishop-Hurley, S.L.; Padmanabha, J.; McSweeney, C.S. Effects of Feeding Plant-Derived Agents on the Colonization of Campylobacter jejuni in Broiler Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2014, 93, 2337–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsi, K.; Donoghue, A.M.; Venkitanarayanan, K.; Kollanoor-Johny, A.; Fanatico, A.C.; Blore, P.J.; Donoghue, D.J. The Efficacy of the Natural Plant Extracts, Thymol and Carvacrol against Campylobacter Colonization in Broiler Chickens. J. Food Saf. 2014, 34, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollanoor-Johny, A.; Mattson, T.; Baskaran, S.A.; Amalaradjou, M.A.; Babapoor, S.; March, B.; Valipe, S.; Darre, M.; Hoagland, T.; Schreiber, D.; et al. Reduction of Salmonella Enterica Serovar Enteritidis Colonization in 20-Day-Old Broiler Chickens by the Plant-Derived Compounds Trans-Cinnamaldehyde and Eugenol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 2981–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.M.; Boinett, C.J.; Chan, A.C.K.; Parkhill, J.; Murphy, M.E.P.; Gaynor, E.C. Investigating the Campylobacter jejuni Transcriptional Response to Host Intestinal Extracts Reveals the Involvement of a Widely Conserved Iron Uptake System. mBio 2018, 9, e01347-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagle, B.R.; Upadhyay, A.; Upadhyaya, I.; Shrestha, S.; Arsi, K.; Liyanage, R.; Venkitanarayanan, K.; Donoghue, D.J.; Donoghue, A.M. Trans-Cinnamaldehyde, Eugenol and Carvacrol Reduce Campylobacter jejuni Biofilms and Modulate Expression of Select Genes and Proteins. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC); European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); European Medicines Agency (EMA). Third Joint Inter-Agency Report on Integrated Analysis of Consumption of Antimicrobial Agents and Occurrence of Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria from Humans and Food-Producing Animals in the EU/EEA. EFSA J. 2021, 19, e06712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenquist, H.; Nielsen, N.L.; Sommer, H.M.; Nørrung, B.; Christensen, B.B. Quantitative Risk Assessment of Human Campylobacteriosis Associated with Thermophilic Campylobacter Species in Chickens. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 83, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windisch, W.; Schedle, K.; Plitzner, C.; Kroismayr, A. Use of Phytogenic Products as Feed Additives for Swine and Poultry1. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 86, E140–E148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viju, L.S.; Joseph, D.; Kosuri, V.V.; Balasubramanian, B.; Zhu, C.; Allen, J.; Shah, T.; Walunj, A.; Pellissery, A.J.; Mishra, N.; et al. In-Feed Supplementation of Linalool Reduces Salmonella enteritidis Colonization in Broiler Chickens. In Proceedings of the IAFP Annual Meeting, Toronto, ON, Canada, 18 July 2023. Conference Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, S.; Niwa, H.; Itoh, K. Prevalence of 11 Pathogenic Genes of Campylobacter jejuni by PCR in Strains Isolated from Humans, Poultry Meat and Broiler and Bovine Faeces. J. Med. Microbiol. 2003, 52, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, I.; Mateo, E.; Churruca, E.; Girbau, C.; Alonso, R.; Fernández-Astorga, A. Detection of cdtA, cdtB, and cdtC Genes in Campylobacter jejuni by Multiplex PCR. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 296, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Amill, V.; Konkel, M.E. Secretion of Campylobacter jejuni Cia Proteins Is Contact Dependent. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1999, 473, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konkel, M.E.; Garvis, S.G.; Tipton, S.L.; Anderson, D.E.; Cieplak, W. Identification and Molecular Cloning of a Gene Encoding a Fibronectin-Binding Protein (CadF) from Campylobacter jejuni. Mol. Microbiol. 1997, 24, 953–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassenaar, T.M.; Bleumink-Pluym, N.M.; van der Zeijst, B.A. Inactivation of Campylobacter jejuni Flagellin Genes by Homologous Recombination Demonstrates That flaA but Not flaB Is Required for Invasion. EMBO J. 1991, 10, 2055–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachamkin, I.; Yang, X.H.; Stern, N.J. Role of Campylobacter jejuni Flagella as Colonization Factors for Three-Day-Old Chicks: Analysis with Flagellar Mutants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 1269–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S. Essential Oils: Their Antibacterial Properties and Potential Applications in Foods—A Review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peana, A.T.; D’Aquila, P.S.; Panin, F.; Serra, G.; Pippia, P.; Moretti, M.D.L. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Linalool and Linalyl Acetate Constituents of Essential Oils. Phytomedicine 2002, 9, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombetta, D.; Castelli, F.; Sarpietro, M.G.; Venuti, V.; Cristani, M.; Daniele, C.; Saija, A.; Mazzanti, G.; Bisignano, G. Mechanisms of Antibacterial Action of Three Monoterpenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2474–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.