1. Introduction

Bordetellosis, caused by the Gram-negative

Bordetella avium (previously called

Alcaligenes faecalis) that colonizes the upper respiratory tract of turkey poults and occasionally chickens, is among the many diseases affecting commercial turkey production [

1].

Bordetella avium-infected turkeys experience numerous physiological dysfunctions that are indicative of a stress response such as elevated plasma corticosterone [

2] and compromised immunity such as inhibition of cell-mediated immunity [

3], body temperature extremes [

4], thyroid hormone depression [

5], altered tryptophan metabolism [

6], decreased tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase activity [

7], altered catecholamine metabolism in various body tissues [

8], trachea collapse due to a specific type II collagen lesion [

9], ciliostasis and deciliation [

3,

10]; increased susceptibility to numerous respiratory and enteric bacterial pathogens [

3,

9], diarrhea [

11] and finally decreased growth and weight gain [

2,

3,

4]. Biochemical characterization of these severe dysfunctions associated with bordetellosis has received considerable attention in our laboratory over the past 40 years. Currently, we are interested in determining the involvement of heat shock proteins (HSPs) in the pathogenesis of bordetellosis. Research has shown that 28-day-old turkey poults can develop a robust humoral immune response to

B. avium infection [

12], but when challenged at 3 d of age, the host immune response is not apparent until after maternal antibody levels are diminished, which was followed at 28 d of age with maximum anti-

B. avium antibody titers [

12]. More recent research, using 21 d old poults, showed that the poults’ host immune response to

B. avium challenge was slow to develop, reaching maximum anti-

B. avium antibody titers at 21 d to 28 d post challenge [

13], similar to the observations by Arp [

12]. Vaccination of 1 d to 21 d old

B. avium-challenged poults did not result in anti-

B. avium antibodies until at least 28 days post challenge, and maximum anti-

B. avium antibody titers were not observed until poults were 49 d old. These reports suggest that turkey poult recognition of

B. avium antigens was impaired, requiring at least a 14 d incubation period before host humoral immunity is stimulated. At 7 d post hatch, poults, treated in ovo with vitamin E and challenged intravenously with sheep red blood cells (SRBCs), developed maximum anti-SRBC antibody titers at 7 d post challenge [

14].

The HSP families are separated on the basis of their molecular mass, falling roughly into 10, 20, 40, 60, 70, 90, and 110 kDa molecular-weight families [

15,

16,

17], and these HSPs have been characterized in turkeys and chickens [

18]. Eukaryotic HSP70 genes encode for constitutive and inducible HSP70, the glucose-responsive GRP78/BIP, and the mitochondrial p75 proteins [

19]. The various HSP families are induced by heat exposure, viral and bacterial infections, amino acid analogs, transition heavy metals, hypoxia, glucose deprivation, and by biologically active molecules such as hemin, tumor necrosis factor, and eicosanoids [

19,

20].

The HSP70s (constitutive and inducible) have been studied intensively and are involved in the regulation of protein folding, assembly, intracellular translocation, cytoprotection from damaging heat exposure, refolding of partially denatured proteins, ATP-dependent catalysis of protein assembly and disassembly reactions, and assembly and binding of immunoglobulin heavy chains [

16,

17].

Prokaryotic cells also have the capacity to express HSP60 and HSP70 families of proteins [

21]. In prokaryotes, there are special HSPs called GroEL and GroES (bacterial HSP60 and HSP10 family proteins), as well as DnaK (HSP70 equivalent) and DnaJ (HSP40 equivalent), which serve the same kinds of functions as do the HSP60 and HSP70 and HSP40 families, respectively, in eukaryotes. The GroEL and DnaK proteins in prokaryotes are highly conserved constitutive proteins [

22,

23] and have been found in

B. avium [

24]. Usually, the bacterial HSPs are highly conserved in prokaryotic cells and are found in the cytoplasm, but GroEL can also be expressed on the surface of cells [

20,

25,

26,

27,

28]. The GroEL in bacteria is expressed at the time of host invasion or exposure to environmental stressors [

20]. In mammals, strong cellular and humoral immune responses are mounted against bacterial HSPs, likely due to the presence of GroEL/GroES (HSP60/65/10) complexes and DnaK (HSP70), which are recognized as highly expressed dominant bacterial antigens in some bacterial infections [

29,

30,

31]. It has been reported that GroEL is produced by all ESKAPE pathogens (

Enterococcus faecium,

Staphylococcus aureus,

Klebsiella pneumoniae,

Acinetobacter baumannii,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and

Enterobacter spp.) and is highly conserved across these species [

32,

33]. Similarly,

B. pertussis GroEL is similar to the human chaperonin protein HSP60, having 53.15% homology [

34], which was not an unexpected observation. Thus, in birds, an involvement of HSP60/65/10 (GroEL/GroES) in tracheal epithelial cells during

B. avium infection may play a role in pathogenesis, but there is no information in any database dealing specifically with host/bacterial HSP60/65/10 and pathogenesis in poultry species. Yet, it is apparent that the bacterial 60/65/10 kDa (GroEL/GroES) common antigens, first characterized in

Mycobacterium spp., are vitally important in the development of bacterial pathogenesis in turkeys and other poultry species [

35].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Ethical Statement

This study was conducted at North Carolina State University at the North Carolina Agricultural Research Service Dearstyne Avian Disease Research Center. The study was approved and monitored by the University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol #21-0204-A and approved on 24 September 2021).

3.2. Poults

Female British United Turkey poults, without hatchery services such as vaccinations, snood, or beak or claw trimming, were used in two separate trials with six replicate pens of 10 poults per pen for each control and infected group of poults in each trial in this experiment. A total of 240 poults (60 control and 60 infected in each trial) were involved in each of the two trials. The parent flock of hens had not been given vaccines against Bordetella avium. The poults were purchased from a commercial hatchery (Select Genetics Hatchery, Goldsboro, NC, USA) within 6 h post hatch and were transported to North Carolina State University’s Agricultural Research Service (NCARS) Dearstyne Avian Research Center in the Prestage Department of Poultry Science.

3.3. Husbandry

The turkey poults were placed in heated battery brooders in which the environmental temperatures were controlled at 34 °C for 7 d, 30 °C for 14 d, and 26 °C for 21 d. The poults were subjected to continuous light for the 21 d duration of the experiment. NCARS turkey starter feed (

Table 1) with 1.899% fat, 28.13% crude protein, and 2915 kcal/kg metabolizable energy in stainless steel feeders and water in open stainless steel waterers were available on an ad libitum basis.

3.4. Infection

One-day-old poults from a commercial hatchery were challenged via the intranasal route with a 50 μL volume of 105 colony-forming units (CFU) of the Wampler (“W”) strain Bordetella avium, the standard test strain used in this laboratory. The inoculum was placed on the nares of the poults, and this was followed by closed-mouth breathing. The inoculum was a 24 h brain–heart infusion broth culture grown at 37 °C.

3.5. Humoral Antibody Response to B. avium Infection

Testing for humoral immune responsiveness was accomplished by an intramuscular (im) sheep red blood cell (SRBC) challenge of control and

B. avium-infected poults. When the poults were 3 d old, an im challenge into the pectoralis major breast muscle with 1% suspension of SRBC [

36]. At 4 d after SRBC challenge (7 d old poults), 10 birds from control and

B. avium-infected pens were bled via their ulnaris vein, and 1 mL of blood was collected for serum expression from each representative randomly caught poult at days 4, 8, 11, and 18 after SRBC challenge. The eluted serum from each blood sample was used to determine anti-SRBC antibody titers using a microhemagglutination plate method incorporating a 1% SRBC suspension. The recorded antibody titer was the reciprocal of the highest dilution where agglutination of the SRBCs occurred and was expressed then as a log

2 value for the antibody titers [

36].

3.6. Reisolation of Bordetella avium

At 7, 14, and 21 d of age/post challenge, 7 randomly caught poults from control and infected groups were euthanized via carbon dioxide asphyxiation. Then, 2 euthanized poults from each group were subjected to

B. avium reisolation via tracheal swab with sterile cotton-tip applicators. These swabs were exposed to a brain–heart infusion broth to grow the

B. avium for 24 h. The cultures were plated on MacConkey agar to determine colony morphology following incubation at 37 °C and 70% relative humidity for 24 h [

37].

B. avium colonies were found to have two morphologies—smooth and rough—which were consistent with the characterization of the North Carolina isolate, the “W” strain [

37].

3.7. Immunohistochemistry

At 7 d, 11 d, 14 d, and 21 d post challenge with B. avium, 5 poults from each treatment were killed; trachea rings were collected for immunohistochemical demonstration of HSP60 and HSP70. The tracheal rings, approximately 5 mm long, were dissected from the trachea approximately 2 cm below the larynx, which is a region of the trachea that is always colonized by B. avium as it is the cause of the upper respiratory tract infection. The trachea rings were snap frozen, cut at 5µm, placed on a slide, and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C, 10 min. The slides were drenched with 1% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for 10 min at room temperature (RT) to quench endogenous peroxidase and were rinsed in tap water, then phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). A 3% H2O2 solution was used normally to quench endogenous peroxidase, but in many instances, the epithelial cells from trachea sections from chickens and turkeys simply “boiled off” the slides. Thus, 1% H2O2 was adapted to the procedure and used for a longer time for quenching.

The sections were then blocked at RT with goat serum for 20 min, followed by a rinse with PBS. Next, the sections were exposed at RT to a 1:400 dilution of HSP60 MAB, and the sections for HSP70 were exposed to a 1:1000 dilution of a HSP70 MAB (StressGen Biotechnologies Corp., Victoria, BC, Canada V8Z 4B9) for 40 min. The sections on slides were then rinsed with PBS. The HSP60 and HSP70 MABs were linked with biotinylated goat α mouse IgG for 20 min at RT, then rinsed again with PBS. The sections with HSP60 and HSP70 MABs were labeled at RT for 20 min with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin and were rinsed with PBS. The sections were then exposed at RT to AEC chromagen for 3 min, and finally, they were counter-stained at RT with Mayer’s hematoxylin for 1 min and rinsed in tap water before being cover-slipped with glycerin jelly.

Quantification of trachea epithelial cell staining intensity of the HSP60 and HSP70 MABs labeled with the horseradish peroxidase was accomplished by blind observation by three technicians. Subjective scores ranging from 0 to 4 were assigned to the reactive staining intensity. A score of 0 = no staining, 1 = faint staining, 2 = light to moderate, 3 = moderate, and 4 = heavy for the staining intensities. Trained technicians subjectively evaluated the staining intensity of cytoplasm and brush borders of tracheal epithelial cells from both control and infected poults. Each technician would score a minimum of 50 cells in 5 different sites for the tracheal epithelial cells on each section of the slide. Slides were scanned with a Leitz Orthoplan research microscope using a 100× bright field oil immersion objective (Ernst Leitz GMBH, Wetzlar, Germany).

3.8. Scanning Electron Microscopy

The trachea sections (2 to 4 mm3) were collected immediately after the trachea had been dissected and placed in ice-cold 3% glutaraldehyde and 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4, and then held at 4 °C for two hours. The samples were washed 3 × 15 min each in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer at 4 °C, then post-fixed for 2 h in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer at 4 °C for 2 h. The tissue samples were washed again 3 × 15 min each in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer at 4 °C, trimmed to 1 mm cubes, and dehydrated in 10% graded series of ethanol solutions (30 to 70% for storage at 4 °C). Samples were then dehydrated in 3 × 95% ice cold ethanol for 15 min each, and finally the tissues were dehydrated in 3 × 100% ethanol for 15 min each with gradual return to RT (25 °C). After critical point drying with carbon dioxide, the samples were sputter coated with 25 ηm Au/Pd and then examined at 15–25 kV in the Philips 505T scanning electron microscope (Philips Healthcare, Bothell, WA 98021-8431, USA).

3.9. Statistical Analyses

Body weight, anti-SRBC antibody titers, and HSP60 and HSP70 staining intensity data were subjected to analysis of variance using the general linear models procedure of the Statistical Analysis System [

38]. Very little variation was noted among the subjective observations of the three technicians who scored the immunohistochemically stained tracheal sections. Thus, the subjective observations of staining intensity by the three technicians were pooled for statistical analysis. The completely randomized statistical model included treatments (two) and sampling time (four) as main effects. Time x treatment interactions were calculated where appropriate. Statements of significance were based on

p ≤ 0.05 or less.

4. Results

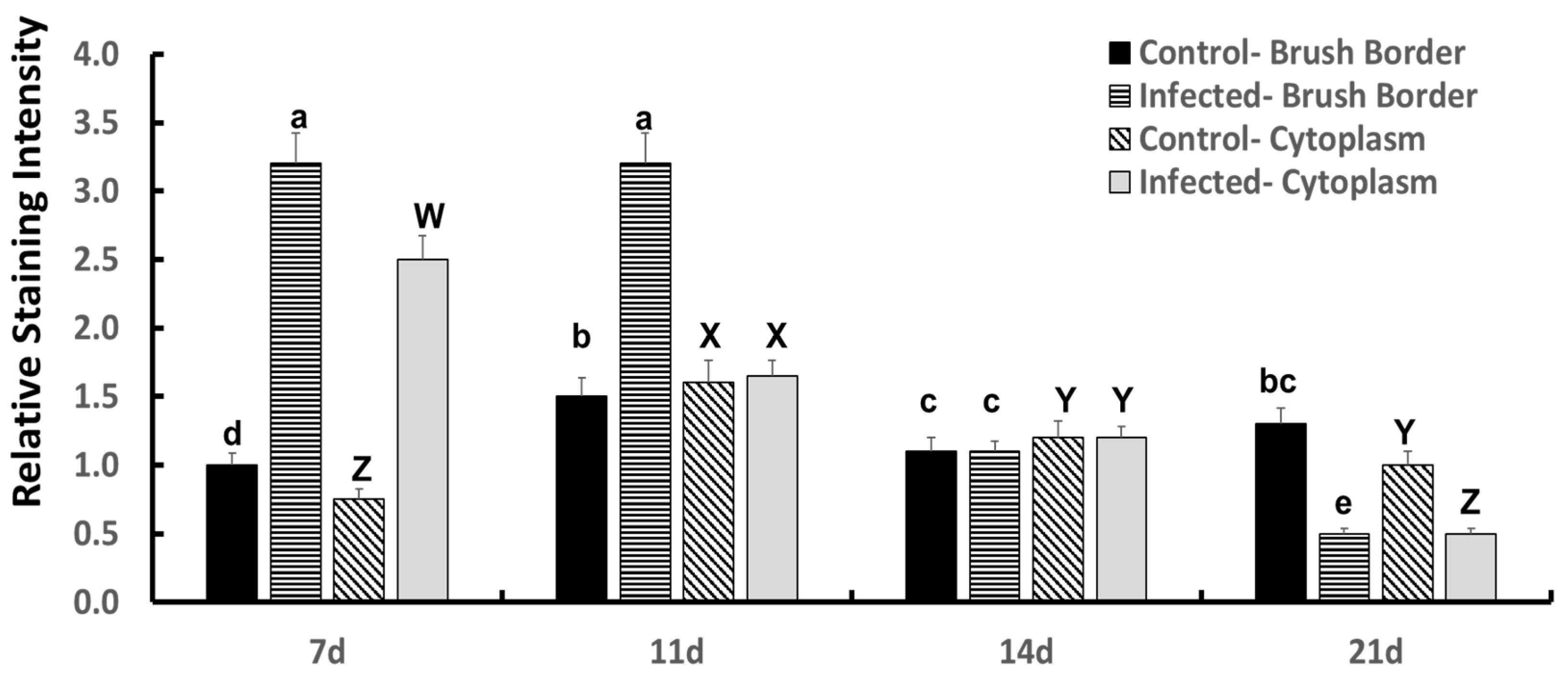

A light microscopic examination of the HSP60 immunohistochemistry with HSP60 MAB conjugation to epithelial cells in tracheal sections from 7 d, 11 d, 14 d, and 21 d old control and

Bordetella avium-infected turkey poults was performed by three experienced technicians. The compiled results of this procedure examining HSP60 MAB staining in control and

B. avium-infected turkey poults are shown in

Figure 1. The luminal surface of the epithelium of the avian trachea is composed of four cell types—a single layer of pseudostratified columnar ciliated epithelial cells, with interspersion of mucous-secreting goblet cells contained in alveolar glands, non-ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelial cells often with attached microvilli, and basal cells that form the basement membrane—which supports the ciliated epithelial cells. The arrangement of the ciliated epithelial cells appears to be in multiple layers, but this is due to the irregular location of the nuclei of the ciliated epithelial cells.

Shown in

Figure 1 are the results from specific immunohistochemical staining against HSP60 MAB of tracheal epithelial cells of turkey poults suffering from bordetellosis. HSP60 MAB staining indicated the presence of HSP60 in the cytoplasm of the ciliated epithelial cells on the luminal surface of the turkey poults’ trachea, but there were dynamic changes in HSP60 MAB staining of the ciliated epithelium cytoplasm and brush border in the

B. avium-infected poults. The significant HSP60 MAB staining intensity was detected in 7 d old infected poults but not in control poults. In control poults, there were age-influenced changes that were significantly less than in infected poults.

In the 7 d control tracheal sections, the HSP60 was, in association with the cytoplasm, but less in the brush border representing the apical portion of the ciliated epithelial cells. The intensity of the control HSP60 staining appeared slightly elevated in poults as they aged from 7 d to 21 d of age. In the

B. avium-infected tracheae, HSP60 staining was significantly elevated (

p ≤ 0.05) in its staining intensity at 7 d and 11 d of age compared to very light staining of assumed constitutive HSP60 in the cytoplasm of control poults. Additionally, by 7 d and 14 d after

B. avium challenge, the staining (deep violet) of the conjugated HSP60 MAB was found to have been induced/ deposited in the brush border of the ciliated epithelium, surrounding the cilia and colonized

B. avium cells attached near the base of the cilia on the apical surface of the ciliated epithelial cells (

p ≤ 0.05). At 11 d after

B. avium infection, HSP60 MAB staining on the brush border remained elevated, but the HSP60 MAB staining intensity in the cytoplasm had decreased significantly from 7 d results. Control 11 d old poults had an increase in cytoplasmic staining intensity compared to 7 d results (

p ≤ 0.05), which was not different from the HSP60 MAB staining intensity in the infected tracheae (

Figure 1). Even though there was a slight but significant increase in control brush border HSP60 MAB staining in controls at 11 d (

p ≤ 0.05), the infected tracheas had a highly significant greater staining intensity (

p ≤ 0.05) than found in controls (

Figure 1). At 14 d, both control and infected poult tracheal epithelial HSP60 MAB staining in both the cytoplasm and brush border had decreased from the 11 d staining intensities (

Figure 1). Finally, at 21 d, HSP60 MAB staining in control cytoplasm and brush border of ciliated epithelial cells did not differ from the staining intensity found at 14 d. However, cytoplasmic and brush border HSP60 MAB staining intensity had decreased significantly (

p ≤ 0.05) from that found at 14 d infected poults. The HSP60 MAB staining decreased significantly in

B. avium-infected tracheal sections, which was attributed to necrosis and sloughing of dead epithelial cells.

The age-related (post challenge) changes found in the HSP60 MAB staining intensity on the brush borders and cytoplasm of the tracheal ciliated epithelial cells (

Figure 1) resulted in a significant time x treatment interaction. The decrease in HSP60 staining intensity in the

B. avium-infected treatment at 14 d and 21 d post challenge was attributed to both cell death and to frank loss of cells from the luminal surface of the tracheae from infected poults.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed to visualize the development of tracheal epithelial lesions indicative of bordetellosis in the young turkeys in this investigation. Control ciliated epithelial cells maintained their apical surface ciliated epithelial cell morphology with complete coverage of the basement membrane at 7 d, 14 d, and 21 d of age. The control tracheal cilia, as typically described, were hair-like in structure with an appearance of being erect and flexible, capable of active “fluid-like” movement as if waving wheat in a field. This appearance was found in controls from 7 d through 21 d of age in this study. Occasionally, a non-ciliate columnar epithelial cell was observed, showing in many instances, with its apical surface bearing numerous microvilli. At no time, during this 21 d long study, bacteria were observed as being colonized in the control tracheal cilia. Occasionally, a small globule of mucous could be visualized among the tracheal cilia of control poults.

At 7 d after infection, tracheal cilia were visually malformed, having mucous accumulation across a large proportion of the luminal surface of the infected tracheae. The SEMs of the cilia revealed that the cilia were no longer standing erect and appeared to have fallen, showing no active movement as seen in control trachea cilia. Additionally, even after only 7 d post B. avium challenge, it was apparent that the integrity of the ciliated epithelial cells had been compromised as visible fissures among groups of the cells had appeared. In addition to the mucous covering the surface of the cilia, large globules of mucous were found among the flattened cilia on the epithelial cells. A major aspect of the physical damage, assessed at 7 d post B. avium challenge, was the presence of large numbers of bacteria among the fallen cilia, which appeared to be attached to the cilia and to the apical surface of the epithelial cells on the luminal surface of the trachea.

At 11 d after B. avium challenge, extensive physical damage to the epithelial cells was observed in all SEMs. In every trachea of the infected poults, cells bearing cilia were difficult to visualize, but numerous nonciliated cells could be seen. There was excessive mucous accumulation on the luminal surface of the tracheae, along with long columns of extruded mucous towering into the lumen of the trachea, which was evident in nearly all of the SEMs. There were still colonies of bacteria adhering to the few remaining ciliated epithelial cells. An assessment of the physical damage that had occurred among the epithelial cells of the trachea indicated folds of cells that were raised as if the cells were detached from their moorings to their basement membrane attachment sites. Fissures noted at 7 d post challenge had increased in size, signaling that physical cellular loss was occurring.

At 14 d post B. avium challenge, massive sloughing of necrotic cells was apparent. Strikingly, individual dead columnar cells could be identified easily, and these were essentially found in loose arrangements as if in piles of debris. None of these damaged cells were attached to their basement membrane sites in the B. avium-infected poults. By 21 d after B. avium challenge, the luminal tracheal epithelial cells of the upper one-third of the tracheae of infected poults were completely removed following the B. avium-induced inflammation and sloughing off of the necrotic cells. The tracheae of the infected poults at 21 d revealed no ciliated epithelial cells, but the surface of the tracheal lumen showed the outlines of the apical surface of cuboidal basal cells that give rise to the normal basement membrane that supports the ciliated epithelial cells. Additionally, it was not uncommon to visualize pores from alveolar mucous-secreting glands, which continued to secrete copious quantities of mucous. There was no evidence of remaining bacterial colonies, presumably B. avium cells.

The reduction in HSP60 staining intensity in

B. avium-infected tracheae was associated with tracheal epithelial cell necrotic death (most intensely stained ciliated epithelial cells) and sloughing in association with the development of the tracheal lesions due to

B. avium infection. This can be visualized in

Figure 2, showing representative scanning electron micrographs of the tracheal epithelium in control versus

B. avium-infected poults at 7 d, 11 d, 14 d, and 21 d of age following

B. avium intranasal challenge at 1 d of age. At 7 d, the cilia on the epithelial cells of control poults were still numerous and apparently functional even though there was an indication that the ciliated epithelial cells in the trachea of infected poults may be losing their functionality since there are many cilia that appeared to be collapsing perhaps due to biochemical changes in the cytoplasm or to organelle changes that may be associated with bordetellosis. In control poults, the trachea appeared mature and functional with complete cell coverage with cilia. By 11 d in the infected poults, large fields of ciliated epithelial cells appear to be degenerating. Nevertheless, by 14 d the process of epithelial cell sloughing in the infected poults is advanced, and large sheets of epithelial cells appear to be sloughing from the basement membrane. At 21 d post challenge, 100% of the trachea had been denuded, but a few apparently damaged epithelial cells remained.

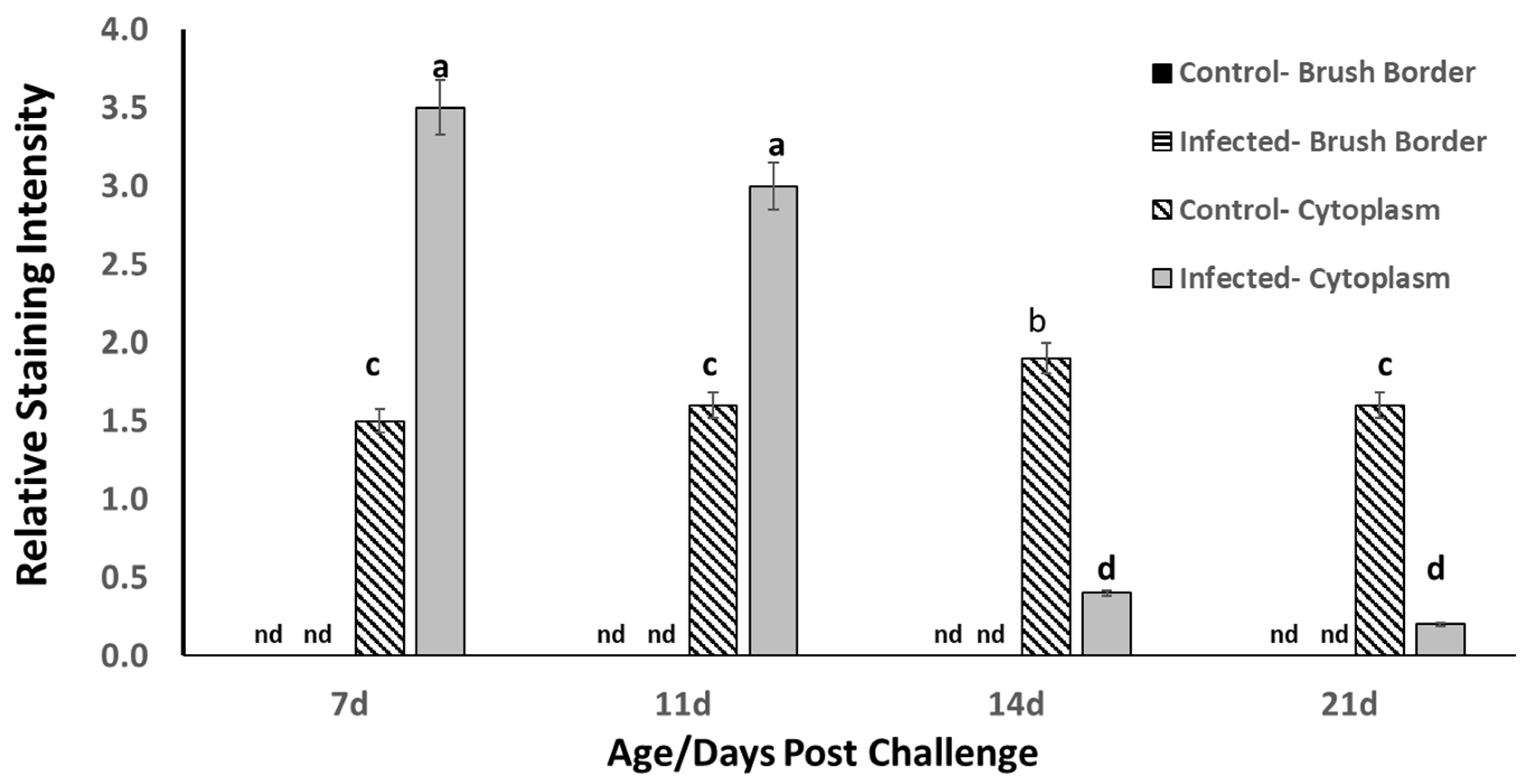

The results of the tracheal ciliated epithelial cell HSP70 analyses are presented in

Figure 2. The subjectively scored staining intensity of HSP70 on the brush border of the epithelial cells was negative, showing no surface HSP70 accumulation on either control or

B. avium-infected poults from 7 d to 21 d of age/post challenge, respectively. Staining intensity was considered as an indicator of increased HSP70 (constitutive + inducible forms), and as staining intensity increased (low staining intensity = pale violet; high staining intensity = deep violet), it was noted clearly to be exacerbated in tracheae from infected poults.

Cytoplasmic staining intensity of HSP70 was increased slightly but significantly in control poults from 7 d to 14 d of age (

p ≤ 0.05), but by 21 d of age, the control cytoplasmic HSP70 had decreased to an intensity that was not different from 7 d and 11 d intensity. However, at 7 d post

B. avium challenge, cytoplasmic HSP70 was elevated significantly compared to control at 7 d and remained elevated at 11 d post challenge. At 14 d post challenge, the cytoplasmic HSP70 in the infected poults had decreased to an intensity that was barely detected and even decreased more at 21 d post challenge (

Figure 2), but this staining intensity decreased significantly from the 7 d and 11 d level to the barely detected levels at 14 d and 21 d of age/post challenge. This response also resulted in a significant time x treatment interaction (

p ≤ 0.01). The increased HSP70 staining intensity in

B. avium-challenged tracheal ciliated epithelial cells was attributed to the developing inflammatory reaction to the infective agent and to the fact that damaged cells were beginning to undergo the dying process, leading to necrosis similar to the process described above. The decrease in HSP70 staining intensity in the

B. avium-infected treatment at 14 d and 21 d post challenge was attributable to both cell death and to frank loss of ciliated epithelial cells, ostensibly due to dermonecrotic toxin and tracheal cytotoxins produced by the

B. avium cells.

The body weight of

B. avium-infected poults was decreased significantly (

Table 2). This observation was consistent with other observations that

B. avium infection will decrease the body weight of turkeys and will be evident in parallel with the development of overt clinical signs of bordetellosis between 7 d and 14 d post challenge. Mucous secretion and its accumulation on the external nares and on the head of the poults reached their peak between 7 d and 14 d post challenge. Between these times, HSP60 staining intensity on the brush borders and in the cytoplasm increased and then decreased significantly in trachea ciliated epithelial cells in the

B. avium-infected poults. Furthermore, staining intensity of the HSP70 increased and then decreased in the same pattern as that for HSP60 in the tracheal ciliated epithelium of the infected poults. The pattern of rise and then fall of the HSPs suggests a cellular response to some stimulus, likely the various toxins produced by

B. avium. The staining intensity decline after the significant increase at 7 d and 11 d after challenge may indicate an immune response against the HSPs or a frank loss of cell viability due to bacterial toxins.

Humoral immune response to SRBC by control and

B. avium-infected poults is shown in

Table 3. There was no significant difference between the control and

B. avium-infected poults at 4 d and 8 d post challenge. At 11 d and 18 d post challenge,

B. avium-infected poults had significantly lower anti-SRBC antibody titers than the control poults. Generally,

B. avium-infected poults had slightly lower anti-SRBC antibody titers than did controls from 7 d to 21 d of age.

5. Discussion

In this investigation, the objective was to explore the possibility that

B. avium is able to escape recognition by the host immune system, but the data collected were not unequivocally supportive of this hypothesis. Nevertheless, one must consider that, apparently, the turkey poult has delayed acquired immune capabilities before they are at least 14 d of age based on their response to a SRBC challenge [

12,

13]. The antibody-forming cell assay, or plaque-forming cell assay, is one of the most often used to test the T-cell-dependent (TDAR) SRBC antigen and is considered the gold standard for TDAR experimental studies to test humoral immunity in poultry [

39]. In this investigation, the poults responded to an

im SRBC challenge, but their humoral anti-SRBC titers were very low and continued showing anti-SRBC antibody titers even through 18 d post challenge. This observation, while unexpected, was consistent with earlier studies [

12,

13,

14,

40], which reported delayed induction of a humoral response to SRBC. It has been demonstrated that even in poults 28 d old, challenged with

B. avium via different routes of exposure, there was a 7 d to 14 d delay before turkeys mounted a measurable humoral immune response to

B. avium challenge [

13,

14]. Furthermore, when lacrimal fluids and tracheal washings were examined for IgA, the tissue presence of IgA was also delayed by 7 d to 14 d after

B. avium challenge. Thus, the young turkey does have the immunological capability to respond humoral to T-cell-dependent antigens presented by

B. avium challenge, albeit somewhat delayed until maternal antibodies have been exhausted.

However, it is interesting that humoral immune responsiveness to

B. avium challenge requires 7 d to 14 d to respond to

B. avium, but in that timeframe, damage to the tracheal ciliated epithelial cells has been exacerbated by bacterial toxins capable of killing tracheal ciliated epithelial cells [

41,

42]. Thus, the question about the relationship between the host humoral immune system and

B. avium colonization in the trachea remains obscured. Yet, based on observations of this study, it was noted that during the 7 d to 14 d post

B. avium challenge, the challenged poults were responding with an intense HSP60 induction in both the cytoplasm and on the tracheal ciliated epithelial cell apical surface among the cilia and among colonizing

B. avium cells.

It has been recognized that bacterial common antigens, represented by the presence of GroEL/GroES (HSP60/65/10) and DnaK (HSP70), are associated with many disease-causing bacteria and can modulate host immune responses in association with the induction of inflammation and autoimmunity [

43]. The nucleotide sequence of rat HSP60 (chaperonin, GroEL homolog) cDNA reveals that it contains major antigens of pathogenic bacteria associated with a number of autoimmune diseases [

44]. Even though there are differences in small segments of the rat HSP60 sequence when compared to other animal HSP60 sequences, much of the sequence is highly conserved [

44]. Eukaryotic HSP60 in swine liver has roughly 53% homology with prokaryotic GroEL (equivalent to HSP60) in bacteria [

45]. It has been observed that the sequence homology among numerous bacterial pathogens for GroEL (HSP60) is very great, with many having more than 98% homology [

46]. It is known that

B. pertussis infection in humans is associated with the induction of HSP60 [

47], and in this report,

B. avium can induce an intense expression of HSP60 both intracellularly and extracellularly. Furthermore, when

B. avium cells were exposed to a stressor, they also showed an immediate HSP60/HSP65 response [

24].

Eukaryotic and prokaryotic HSP60s are highly conserved across species [

48], and these proteins have multiple functions, including modulation of the host’s immunity, which implies that when similar but distinct proteins interact in a living vertebrate system, an immune response is highly probable [

49]. At this level of interaction, both host and invading proteins become targets of the host’s innate immune system, which then promotes inflammatory and autoimmune responses [

43]. When this type of immune reaction occurs, host tissues and their innate immune system components act to destabilize the cellular homeostatic processes. Based on numerous observations of the signs of bordetellosis in young turkey poults, one can hypothesize that loss of tracheal ciliated epithelial cells might simply reflect the outcome of an autoimmune reaction in which similar host antigenic HSP60 and

B. avium antigenic HSP60/65/10 have become antigenic targets of the host’s innate immune system.

The cellular homeostasis of tracheal ciliated epithelial cells certainly is disrupted under the influence of

B. avium-associated dermonecrotic toxin and tracheal cytotoxins [

41,

42], which would provide the conditions suitable for extrusion of cytoplasmic HSP60 and possibly HSP70 as well. Given that damaged/dying cells will produce HSPs and secrete them to extracellular sites [

50], the potential for interaction of the host with

B. avium-secreted HSP60/65/10 epitopes can be elevated significantly. The prokaryotic bacteria HSP60/65/10 (GroEL chaperonin) are recognized as an important antigen in many vertebrate animals, which promotes an intense humoral antibody response [

51]. However, in turkey poults, a similar robust humoral immune response was not evident under similar conditions. Furthermore, host HSP60 has been reported to have properties that act as a self-antigen capable of inducing innate immune responses, potentially exacerbating intense inflammation [

49].

In turkey poults experiencing bordetellosis, there appears to be a complicated immunological development in which epitopes of the host HSP60 might be similar to

B. avium HSP60/65/10 (GroEL/GroES) epitopes, and the host innate immune system begins to function to promote an autoimmune reaction targeting the infected tracheal ciliated epithelial cells, which are killed and sloughed off the basement membrane. In this hypothesized scenario, host HSP60 epitopes, bearing similarity to

B. avium HSP60/65/10 epitopes, would function to promote cellular death rather than functioning to promote cellular recovery from a stressor [

52].

Although no statistical analysis of the phenomenon of cellular loss in the tracheal epithelium and the dynamic changes in the cellular concentrations of HSP70 and HSP60 was performed, it was phenomenal that the loss of the tracheal ciliated epithelial cells’ ability to express HSP60 and HSP70 at the level of the basement membrane and in the cytoplasm corresponded to the timing of the tracheal epithelial cellular loss. One of the pathological consequences of

B. avium infection in the trachea is the universal ability of

Bordetella species to produce tracheal cytotoxins and the ability to produce dermonecrotic toxin [

41,

42]. When both HSP60 and HSP70 were no longer detected by histochemistry, all of the cells in the tracheal epithelium had died and were sloughed off. Therefore, one has to conclude that the roles of HSP60 and HSP70 in the assembly and folding of newly synthesized proteins were unsustainable, and cellular death was the result of loss of function.

However, HSP60 has a functional role separate from HSP70 in the maintenance of cilia proteins based upon its high intensity staining at this cellular structure. With the loss of cytoplasmic HSP60, there was a lag time of about 3 days before brush border HSP60 began to be lost. With this loss in brush border HSP60, the killing influence of the B. avium could be seen clearly, and correspondingly, this marked the time for the most severe epithelial cellular lesions during bordetellosis.

The mechanism whereby HSP60 and HSP70 synthesis were repressed or expressed in

B. avium as it colonizes the tracheal epithelium is not known at this time, but the cell-killing influence of the dermonecrotic and tracheal cytotoxins from

B. avium undoubtedly act as lethal stressors that affect tracheal cellular pro-life functions [

41,

53,

54]. The

B. avium dermonecrotic toxin is mediated via the bordetella virulence gene (bvg), similar to

B. pertussis, but many pertussis toxins are not produced by

B. avium [

54]. It was acknowledged that many bordetella proteins involved in

B. avium pathogenesis remain to be identified. However, the heat shock proteins, ubiquitous across archaebacteria, eubacteria, yeasts, plants, invertebrates, and all vertebrates, might play a more important role in the pathogenesis of disease-causing bacteria in turkey poults than currently recognized. The HSPs, which have multiple functional roles, might be involved in simple actions that set the stage for larger events to develop.

Although HSP60 and HSP70 are involved in the maintenance of cellular protein stability in all animals, overexpression has negative effects as structural protein synthesis diminishes in preference for HSP synthesis [

18]. All of these observations suggest that there is a possibility that the turkey’s immune system may exert a delayed influence on the development of the pathogenesis of

B. avium infection. However, in this research, it must be noted that the humoral side of the turkey immune system was suppressed by

B. avium infection, and additionally, the cell-mediated immunological capabilities of the

B. avium-infected turkey poult are suppressed significantly by

B. avium infection [

3]. Additional research is required to develop a better understanding of the interactions among the host immune system, heat shock proteins, and the development of

B. avium-associated pathogenesis.

To return to the hypothesis that

B. avium might evade detection by the host’s immune system, it was concluded that evasion was not the issue. The young uninfected turkey can respond to T-cell-dependent antigens, but their humoral immune response can be delayed until maternal antibody levels diminish. In the event that the turkey is experiencing bordetellosis, both humoral and cell-mediated immunity will likely be suppressed. Yet, from a physiological viewpoint, the presence of

B. avium in the ciliated epithelial cells in the poult’s trachea is recognized as a stressor due to the bacterial production of dermonecrotic and tracheal cytotoxins, which are likely evident very readily after the poult receives the bacterial challenge. In response to the stressor, the ciliated epithelial cells produce at least two heat shock proteins as a means to stabilize the cellular homeostatic processes associated with cytoplasmic and cell membrane protein damage caused by the toxins, but the cellular processes become overwhelmed, leading to greater production of the heat shock proteins—HSP60 and HSP70. It has been recognized in the scientific literature that there is expression of HSPs in dying cells and that these HSPs can be extruded to the exterior of the affected cells [

55,

56]. In post-exposure

B. avium, over a 7 d to 14 d period, tracheal ciliated epithelial cell lesions will increase, and loss of epithelial cells will progress at an increasing rate associated with decreased detection of HSP60 and HSP70. At this point, an intensive inflammatory reaction has been induced in association with the clearance of dead and damaged cells via autoimmune processes [

57]. The extruded HSPs become self-antigenic, capable of stimulating macrophages with subsequent secretion of cytokines in response to cellular death, stimulating certain aspects of the host’s autoimmune functions in an attempt to rid the trachea of dead cells and tissue [

55]. However, self-antigens from HSP60 epitopes similar to

B. avium HSP60/65/10 epitopes, with an assumed significant homology with host HSP60, might be targeted by both qualitative and quantitative anti-

B. avium antibody differences to the two HSP60 families of stress proteins. This, in view of apparent delayed capabilities to mount the host’s humoral and cell-mediated immune responses to

B. avium and the two HSP60 sources acting as foreign and self-antigens, contributes to the perception that

B. avium has the ability to evade the host’s immune surveillance and reactivity capabilities. Thus, the ability of turkeys to recognize

B. avium is very complex, and to a limited extent, its delayed humoral and cell-mediated responsiveness does contribute to a limited evasion of

B. avium by the host’s immune surveillance systems. Perhaps the perceived autoimmune response would be directed preferentially to the necrotic cells, and the

B. avium cells, due to delayed acquired immune processes, would not be subject to the host’s fully primed acquired immune system against

B. avium in the trachea and other tissues.