Abstract

Modern web applications increasingly demand rendering techniques that optimize performance, responsiveness, and scalability. Progressive Server-Side Rendering (PSSR) bridges the gap between Server-Side Rendering and Client-Side Rendering by progressively streaming HTML content, improving perceived load times. Still, traditional HTML template engines often rely on blocking interfaces that hinder their use in asynchronous, non-blocking contexts required for PSSR. This paper analyzes how Java virtual threads, introduced in Java 21, enable non-blocking execution of blocking I/O operations, allowing the reuse of traditional template engines for PSSR without complex asynchronous programming models. We benchmark multiple engines across Spring WebFlux, Spring MVC, and Quarkus using reactive, suspendable, and virtual thread-based approaches. Results show that virtual threads allow blocking engines to scale comparably to those designed for non-blocking I/O, achieving high throughput and responsiveness under load. This demonstrates that virtual threads provide a compelling path to simplify the implementation of PSSR with familiar HTML templates, significantly lowering the barrier to entry while maintaining performance.

1. Introduction

Modern web applications rely on different rendering strategies to optimize performance, user experience, and scalability. The two most dominant approaches are Server-Side Rendering (SSR) and Client-Side Rendering (CSR). SSR generates HTML content on the server before sending it to the client, resulting in a faster First Contentful Paint (FCP) [1] and better Search Engine Optimization (SEO). Nevertheless, SSR can increase server load and reduce throughput (the number of requests the server can handle per second (RPS)) since each request requires additional processing before responding. In contrast, CSR shifts the rendering workload to the browser—the server initially sends a minimal HTML document with JavaScript, which dynamically loads the page content. While CSR reduces the server’s burden, it can lead to a slower FCP, as users must wait for JavaScript execution before meaningful content appears.

Progressive Server-Side Rendering (PSSR) combines benefits from both SSR and CSR by streaming HTML content progressively. This technique enhances user-perceived performance by allowing progressive rendering as data becomes available, significantly reducing the time-to-first-byte (TTFB) and improving perceived load times compared to traditional SSR approaches [2]. In this respect, PSSR is similar to CSR in that the server initially sends a minimal HTML document to the client and subsequently streams additional HTML fragments. Even so, unlike CSR, PSSR retains all rendering responsibilities on the server side, thereby reducing the load on the client. Consequently, the client does not need to execute JavaScript or make additional requests to retrieve page content. The streaming nature of PSSR allows users to see content progressively as it becomes available, rather than waiting for the complete page to be rendered server-side, thus providing a more responsive user experience with measurably lower TTFB values [2].

Low-thread servers, also known as event-driven [3], have gained prominence in contemporary web applications due to their ability to efficiently manage a large number of concurrent I/O operations with minimal resources, thus promoting better scalability. By leveraging asynchronous I/O operations, such as database queries and API calls, servers can avoid blocking threads while waiting for data, thereby maximizing throughput and responsiveness. To support this non-blocking architecture, PSSR implementations require template engines that are compatible with asynchronous data models [4]. Some modern template engines, such as HtmlFlow [5] and Thymeleaf [6], have been designed with these capabilities in mind. However, many legacy template engines—particularly those using external domain-specific languages (DSLs) [7]—still depend on blocking interfaces like Iterable for data processing. This blocking behavior forces server threads to remain idle until the entire HTML output is ready, undermining the performance benefits of non-blocking I/O and limiting scalability in high-concurrency environments.

With the introduction of virtual threads (https://openjdk.org/jeps/444, accessed on 29 May 2025) in Java 21, it is now possible to execute blocking I/O operations in a scalable, lightweight manner. This capability allows legacy template engines—often reliant on blocking interfaces—to operate efficiently in high-concurrency, non-blocking environments without requiring complex asynchronous programming models. Due to this, PSSR can now be implemented using familiar HTML templates, simplifying development and improving maintainability.

We investigate the current landscape of non-blocking PSSR, focusing on two primary paradigms: reactive programming and coroutines, both of which have been used to achieve asynchronous I/O in the Java ecosystem. As an alternative, we investigate whether Java’s virtual threads can offer comparable performance while preserving the simplicity of synchronous code. Section 2 reviews the state-of-the-art in PSSR and template engine design. Section 3 outlines the limitations of conventional engines in asynchronous settings and presents our proposed approach. Section 4 details the benchmark methodology, followed by the results and analysis in Section 5. Section 6 compares our results with those from other studies. The conclusions of this work are presented in Section 7.

2. Background and Related Work

In this section, we first present the main properties that characterize each web template technology approach, along with the advantages and drawbacks that result from these characteristics. Then, in Section 2.2, we examine the different design choices adopted by web servers in their internal architectures, and how these choices impact the behavior of the web template engines.

2.1. Web Templates

Web templates have been the most widely adopted approach for constructing dynamic HTML pages. Web templates or web views [8,9] (e.g., JSP, Handlebars, or Thymeleaf), are based on HTML documents augmented with template-specific markers (e.g., <%>, {{}}, or ${}), which represent dynamic information to be replaced at runtime with the results of corresponding computations, producing the final HTML page. The process of parsing and replacing these markers—i.e., resolution—is the primary responsibility of the template engine [10]. One key characteristic of web templates is their ability to receive a context object—equivalent to the model in the model-view design pattern [10,11]—which provides the data used to fill template placeholders at runtime. Web templates can be distinguished by several properties, namely:

- 1.

- Domain-specific language idiom

- 2.

- Supported data model APIs

- 3.

- Asynchronous support

- 4.

- Type safety and HTML safety

- 5.

- Progressive rendering

Although some of the aforementioned characteristics apply to both server-side and client-side approaches, we focus solely on web template technologies for Server-Side Rendering, as our work is centered on that approach. Before exploring each of the aforementioned characteristics, Table 1 presents a breakdown of mainstream template engines, classified according to the identified properties.

Table 1.

Comparison of web template technologies in the Java ecosystem. (1) Enforced via annotation processor that checks templates against typed interfaces at compile time. (2) Compile-time expression validation available via @CheckedTemplate and build-time metadata in Quarkus. (3) Publisher of reactive streams [12]. Limited to a single model per web template. (4) kotlin.sequences.Sequence (5) Non-safety for HTML attributes.

The first half of Table 1 lists template engines that use their own templating dialects, referred to as external DSLs. The second half lists Java libraries that provide an internal DSL, typically using a nested or chaining style to build HTML. Note that, by leveraging the host language (e.g., Clojure, Groovy, Java, Kotlin, or Scala) as the templating idiom, the latter impose no restrictions on the data model and fully support all styles of data access APIs. They also benefit from static type checking, which helps ensure type safety.

2.1.1. Domain-Specific Language Idiom

Web templates are based on a domain-specific language (DSL) [13], which defines a language tailored to a specific domain [14]—in this case, HTML for expressing web documents. The DSL constrains the template’s syntax and semantics to match the structure and purpose of HTML. DSLs can be divided in two types: external or internal [7]. External DSLs are languages created without any affiliation to a concrete programming language. An example of an external DSL is the regular expressions search pattern [15], since it defines its own syntax without any dependency of programming languages. On the other hand, an internal DSL is defined within a host programming language as a library and tends to be limited to the syntax of the host language, such as Java. JQuery [16] is one of the most well-known examples of an internal DSL in Javascript, designed to simplify HTML DOM [17] tree traversal and manipulation.

Traditionally, web template technologies use an external DSL to define control flow constructs and data binding primitives. Early web template engines such as JSP, ASP, Velocity, PHP, and others adopted this external DSL approach as their templating dialect. For example, a foreach loop can be expressed in each technology using its own DSL:

- <% for(String item : items) %> in JSP

- <% For Each item In items %> in legacy ASP with VBScript

- #foreach($item in $items) in Velocity

- <?php foreach ($items as $item):?> in PHP

On the other hand, internal DSLs for HTML allow templates to be defined directly within the host language (such as Java, Kotlin, Groovy, Scala, or other general-purpose programming languages), rather than using text-based template files [18]. In this case, a web template is not limited to templating constructs but may instead leverage any available primitive of the host language or any external API.

Using an internal DSL can have several benefits over using textual templates:

- 1.

- Type safety: Because the templates are defined with the host programming language, the compiler can check the syntax and types of the templates at compile time, which can help catch errors earlier in the development process.

- 2.

- IDE support: Many modern IDEs provide code completion, syntax highlighting, and other features, which can make it easier to write and maintain templates.

- 3.

- Flexibility: Use all the features of the host programming language to generate HTML, can make it easier to write complex templates and reuse code.

- 4.

- Integration: Because the templates are defined in Java code, for example, you can easily integrate them with other Java code in your application, such as controllers, services, repositories and models.

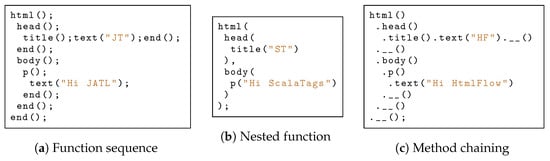

DSLs for HTML provide an API where methods or functions correspond to the names of available HTML elements. These methods, also known as builders, can be combined in a chain of calls to mimic the construction of an HTML document in a fluent manner. Martin Fowler [7] identifies three different patterns for combining functions to create a DSL: (1) function sequence; (2) nested function, and (3) method chaining, which are illustrated in the snippets of Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Utilizing DSL for HTML libraries with JATL, ScalaTags, and HtmlFlow.

From the three examples depicted in Figure 1, the nested function idiom used by ScalaTags, as shown in the snippet of Figure 1b, is the least verbose, requiring fewer statements than the other two cases. This approach of combining function calls is also utilized by Hiccup Clojure Library and j2html Java library. One reason for verbosity in function sequence and method chaining approaches is the requirement of a dedicated HTML builder to emit the closing tag, exemplified by end() in JATL (Figure 1a) and __() in HtmlFlow (Figure 1c). However, the nested function approach comes with a notable drawback: it does not support PSSR because the sequence of nested functions is evaluated backward to the order in which they are written. In other words, arguments are evaluated before the functions are invoked. Taking the example in Figure 1b, the title() function is first evaluated, and its resulting paragraph becomes the argument for the head() call, which, in turn, becomes the argument for html(), and so on. If HTML is emitted as functions are called, it will print tags in reverse order. The aforementioned DSLs must collect resulting nodes into an internal data structure, which is later traversed to produce the HTML output. Therefore, they cannot progressively emit the output as builders are called.

Two other JVM libraries, Groovy MarkupBuilder and KotlinX.html, also adopt a nested function approach, but they address the backward evaluation issue by implementing lazy evaluation of arguments [19], expressed in lambda expressions (also known as function literals). Due to the concise form of expressing lambdas with brackets (i.e., {}) in both Groovy and Kotlin, translating the template shown in Figure 1b to use Groovy MarkupBuilder or KotlinX.html only requires replacing parentheses with brackets for parent elements. HtmlFlow also adopts this approach and provides a Kotlin-idiomatic API as an alternative to its original Java API.

2.1.2. Supported Data Model APIs

Template engines with dedicated templating dialects typically rely on specific control flow constructs—such as a foreach-like statement—to iterate over elements in a data source. In the Java ecosystem, Iterable is the common supertype implemented by most data structures and serves as the standard API for iteration. Nevertheless, other standard interfaces, such as java.util.Stream, also represent sequences of elements but are not compatible with Iterable. This fragmentation becomes more evident when considering other JVM languages, such as Kotlin, which introduces additional abstractions like the Sequence interface—also incompatible with Iterable. Consequently, template engines based on external DSLs must explicitly support each of these interfaces to accommodate the various iteration protocols across languages and libraries.

For example, Thymeleaf supports both Java Iterable and Stream iteration protocols but is incompatible with Kotlin’s Sequence interface. Velocity, on the other hand, uses internal reflection-based template processing that allows it to iterate over any type defining an iterator() method returning an Iterator. This enables support for both Java Iterable and Kotlin Sequence, but it cannot handle Java Stream since Stream does not expose a compatible iterator() method. The remaining analyzed template engines that use external DSLs support only Java Iterable as their sole iteration protocol.

On the other hand, template engines that employ an internal DSL do not face such limitations, as they can leverage any available API within the host programming language. This flexibility extends beyond the standard library to include third-party APIs as well. For example, in Java, developers can iterate over data using a traditional for loop, the java.util.stream API, or external libraries such as Guava, Vavr, StreamEx, and others—depending on their specific needs or preferences.

2.1.3. Asynchronous Support

One of the reasons for legacy web templates not supporting asynchronous APIs is the absence of a unified standard calling convention for asynchronous calls. While there is a single, straightforward way to use a synchronous API with a direct style, where the result of a method call corresponds to its returned value, there is no equivalent standard in the asynchronous approach. Instead, we may encounter various asynchronous conventions depending on the programming language and runtime environment. Some of these approaches include continuation-passing style (CPS) [20], promises [21], async/await idiom [22], or suspend functions [23].

Many general-purpose languages (GPLs) have embraced the async/await feature [22] enabling non-blocking routines to mimic the structure of synchronous ones, allowing developers to reason about instruction flow sequentially. The simplicity and broad adoption of this programming model have led to its incorporation into mainstream languages like C#, JavaScript, Python, Perl, Swift, Kotlin, and others, excluding Java. However, implementing async/await requires compiler support to translate suspension points (i.e., await statements) into state machines. Most template engines operate using an external DSL with their own templating dialect (e.g., Thymeleaf, JSP, Jade, Handlebars, and others), which do not inherently leverage asynchronous capabilities from their host programming languages.

An alternative approach to asynchronous programming involves handling data as a sequence of asynchronous events, commonly known as a reactive stream. Instead of materializing all items in memory, reactive streams emit values over time, allowing clients to subscribe and consume data incrementally as it becomes available. This idea was first proposed by Meijer [24] in the .NET framework, leading to the development of Reactive Extensions (Rx). Subsequently, several alternative implementations emerged in the Java ecosystem, such as Rx Java [25], Project Reactor [26], or the Akka Streams [27] library. Later, due to the proliferation of alternative implementations, the need arose to create a common interface to ensure interoperability between different reactive stream libraries. This led to the formation of a working group that included engineers from notable companies such as Lightbend, Pivotal, and Netflix. The group began defining the reactive streams specification [12], which established a standard for asynchronous stream processing using non-blocking, backpressure-aware data pipelines. The more recent Mutiny [28], while conforming to the reactive streams standard, proposes a different approach that avoids complex optimizations, resulting in more straightforward and easier-to-maintain code.

Thymeleaf was one of the first web template engines—and remains the only one among external DSLs for HTML—to support reactive streams based on the Publisher model. Yet, it is limited to using a single Publisher within a given template.

2.1.4. HTML Safety

Another key characteristic of such DSLs is HTML safety, which refers to whether they produce only valid HTML conforming to a well-formed document. To ensure HTML safety, a DSL API should only allow combining calls to builders that result in valid HTML. Nonetheless, most HTML DSLs using the function sequence or nested function approach cannot ensure HTML safety at compile time.

The function sequence approach, as illustrated in the snippet of Figure 1a, involves combining function calls as a sequence of statements, making it challenging to restrict the order of statements. In the nested function approach shown in Figure 1b, variable-length arguments are often used to allow an undefined number of child elements, which cannot be strongly typed in every programming language.

KotlinX.html, which utilizes the nested function idiom with lazy evaluation, mitigates this issue through function types with a receiver. In this approach, the receiver (i.e., this within the lambda) is strongly typed and provides a set of methods corresponding to legal child elements. This enables KotlinX.html to enforce HTML safety by restricting the available methods during compile time.

To achieve this, KotlinX.html provides HTML builders using function literals with receiver [29]. In Kotlin, a block of code enclosed in curly braces {...} is known as a lambda, and can be used as an argument to a function that expects a function literal. When we write, for example, body { div { hr() } }, we are invoking the body function with a lambda as its argument. This lambda, in turn, calls the div function with another lambda as an argument that creates a horizontal row (i.e., hr). Each call to an HTML builder (e.g., body, div, hr) creates the child element within the element generated by the outer function call.

HtmlFlow provides two APIs: one in idiomatic Kotlin, similar to the KotlinX.html API, and another that employs the method chaining idiom, as illustrated in the snippet of Figure 1c. In this approach, the receiver object is implicitly passed as an argument to each method call, enabling subsequent methods to be invoked on the result of the preceding one. This facilitates the composition of methods, with each call building upon the other. Similar to KotlinX.html, HtmlFlow ensures HTML safety, restricting the available HTML builders and attributes after the dot (.) operator.

2.1.5. Progressive Rendering

Pursuing the optimal user experience for web users has been a consistent goal since the inception of the World Wide Web. Consequently, various approaches have been explored to deliver the initial meaningful content to the end-user as promptly as possible, while the remaining content progressively (or incrementally) loads as the server streams the HTML content.

Progressive rendering and progressive loading encompass different concepts. The former pertains to the dynamic content of a dynamic web page, encompassing elements with logic and placeholders that are fulfilled by data from an object model constructed at runtime. On the other hand, the latter is associated with render-blocking resources such as scripts, stylesheets, and HTML imports, which may hinder the browser from rendering page content to the screen [30]. The notion of progressive rendering has typically been aligned with Client-Side Rendering (CSR), where a single HTML page with static content is delivered upfront, while the dynamic content is fetched as the data becomes available to complete the web page. Nevertheless, despite being overlooked, HTTP and browsers were designed from their inception to also support this feature in the context of SSR approaches, which offers the advantage of not being dependent on render-blocking resources, such as the required JavaScript for CSR. An example of this limitation in SSR web templates was highlighted by Jeff Atwood in 2005, who criticized Microsoft ASP.NET for loading the entire web page into memory before sending any data to the browser [31]. Despite historical critiques and HTML’s inherent capabilities, most Web application frameworks, such as ASP.Net, Express.js, Spring, and others, persistently lack support for progressive rendering, leading to the appearance of alternative techniques leveraging client-side JavaScript. Since 2007, various patents have addressed the PSSR issue, with Microsoft’s patent enabling the infinite scrolling technique by displaying a single page of results [32], and Yahoo’s patent focusing on differentiating elements based on their position relative to the visible portion [33].

Former techniques all describe methods of progressively adding content to a web page depending on client-side JavaScript. Java Thymeleaf, the default SSR template engine for Spring web servers, added support for PSSR in 2018, through the use of a specific non-blocking Spring ViewResolver driver and without requiring client-side JavaScript. Carvalho [4] introduced an SSR solution that manages multiple data models and asynchronous APIs while ensuring well-formed HTML, PSSR, and non-blocking template resolution. That solution builds upon HtmlFlow, a Java DSL for HTML, with an internal processing mechanism that streams HTML in chunks as data items become available from data sources, without requiring client-side JavaScript. Like Thymeleaf, their proposal avoids the use of client-side JavaScript; yet, unlike Thymeleaf, it supports a wide range of asynchronous APIs and multiple data sources, not limited to the Publisher API. Nonetheless, the main counter-argument is the non-trivial management of the resume callback in continuations [34,35], which is used to linearize the execution flow between asynchronous calls.

2.2. Web Framework Architectures and Approaches to PSSR

In traditional thread-per-request architectures, each incoming request is handled by a dedicated thread. The web server maintains a thread pool from which a thread is assigned to handle each request. As the load increases, the number of active threads can grow rapidly, potentially exhausting the pool. This can lead to performance and scalability issues, as the system may become bogged down by context switching and thread management overhead [36]. In the Java ecosystem, Spring MVC is one of the most widely used frameworks that follow this model, according to several reports such as the Stack Overflow 2024 Developer Survey (https://survey.stackoverflow.co/2024/technology#1-web-frameworks-and-technologies, accessed on 29 May 2025).

On the other hand, in modern low-thread architectures, the server uses a small number of threads to handle a large number of requests. Low-thread servers, also known as event-driven [3], offer a significant advantage in efficiently managing a high number of concurrent I/O operations with minimal resource usage.

The non-blocking I/O model employed in low-thread servers is well-suited for handling large volumes of data asynchronously [37]. This combination of low-thread servers and asynchronous data models has facilitated the development of highly scalable, responsive, and resilient web applications capable of managing substantial data loads [38]. The prominence of this concept increased with the advent of Node.js in 2009, and subsequently, various technologies adopted this approach in the Java ecosystem, including Netty, Akka HTTP, Vert.x, and Spring WebFlux. The non-blocking I/O model in low-thread servers functions optimally only when HTTP handlers avoid blocking. Therefore, HTML templates need to be proficient in dealing with the asynchronous APIs provided by data models. While most legacy web templates struggle with asynchronous models, DSLs for HTML face no such limitations, leveraging all constructions available in the host programming language. However, the unexpected intertwining of asynchronous handlers’ completion and HTML builders’ execution may potentially lead to malformed HTML with an unexpected layout [2].

An alternative approach involves utilizing user-level threads, while maintaining a blocking I/O and a synchronous programming paradigm. On the other hand, this approach still requires a user-level I/O subsystem capable of mitigating system-level blocking, which is crucial for the performance of I/O-intensive applications. This technique offers a lightweight solution for efficiently managing a larger number of concurrent sessions by minimizing per-thread overhead. In 2020, Karsten [39] demonstrated how this strategy supports a synchronous programming style, effectively abstracting away the complexities associated with managing continuations in asynchronous programming.

Among mainstream technologies, the Kotlin programming language introduces a new abstraction for managing coroutines and provides structured concurrency, which ensures that coroutines are scoped, cancellable, and coordinated within a well-defined lifecycle [23]. Although this model embraces the async/await feature [22], enabling non-blocking routines to mimic the structure of synchronous ones, it still lacks a user-level I/O subsystem and relies on an explicit I/O dispatcher tied to a dedicated thread pool that frees worker threads for handling processing tasks. Moreover, web templates using their own templating dialects, such as JSP, Thymeleaf, or Handlebars, are unable to take advantage of such constructs, as they typically support only a limited subset of the host library’s API—most commonly just the Iterable interface.

Only Java virtual threads, introduced in JEP 444 (https://openjdk.org/jeps/444, accessed on 29 May 2025), adopt a similar approach to Karsten’s proposal, using user-mode threads to preserve a synchronous programming model while still allowing blocking I/O operations without tying up platform threads. When a virtual thread performs a blocking I/O operation, the JVM intercepts the call and transparently parks the virtual thread, freeing the underlying platform thread to perform other tasks. Once the I/O operation completes, the virtual thread is rescheduled on a platform thread and resumes execution. This mechanism is enabled by the JVM’s integration with non-blocking system calls at the OS level, allowing developers to write traditional synchronous code while benefiting from the scalability of non-blocking I/O.

The primary advantage of virtual threads lies in their ability to eliminate the need for complex asynchronous programming models. Unlike reactive or structured concurrency approaches that require developers to adopt complex paradigms, virtual threads enable non-blocking execution of existing synchronous APIs without code modification. This significantly reduces the learning curve and maintenance burden associated with asynchronous programming while maintaining comparable performance characteristics.

2.2.1. Spring MVC

Spring MVC is a synchronous web framework built on the thread-per-request model. When an HTTP request is received, it is handled by a dedicated thread from the server’s thread pool (e.g., Tomcat, Jetty, or Undertow). This thread is responsible for executing the full request lifecycle synchronously, including invoking controllers, executing business logic, and rendering the response view. Because the model is blocking, the thread remains occupied throughout the request—even during I/O operations such as database queries or external API calls—which can lead to performance bottlenecks under high concurrency.

Controllers in Spring MVC typically return Java objects or models that are processed by view resolvers in conjunction with template engines like JSP, Thymeleaf, or FreeMarker. These templates generate the full HTML response in one pass, which is then sent to the client only after all necessary data has been gathered and rendered. By default, this architecture limits the ability to perform PSSR, as traditional rendering waits for all data before sending any output. This results in higher latency for clients and less responsive page loads, particularly for data-intensive views. In any case, Spring MVC provides a mechanism for response streaming via the StreamingResponseBody (https://docs.spring.io/spring-framework/docs/current/javadoc-api/org/springframework/web/servlet/mvc/method/annotation/StreamingResponseBody.html, accessed on 29 May 2025) interface, introduced in Spring 4.2. When a controller method returns a StreamingResponseBody, Spring writes directly to the HttpServletResponse output stream, allowing the server to send parts of the response incrementally as they become available. This is particularly useful for the following applications:

- Sending large responses without buffering the entire output in memory.

- Writing dynamic HTML in fragments as data is fetched or computed.

- Reducing time-to-first-byte (TTFB) and improving perceived performance.

In the example shown in Listing 1, HTML content is written and flushed in discrete chunks, allowing the client to progressively render the response as it arrives, while the server continues processing additional data. This technique has two limitations. First, it does not eliminate the blocking nature inherent in Spring MVC, as the handling thread remains active during the streaming process. Second, it is constrained by the servlet response buffer. By default, most servlet containers (e.g., Tomcat) use a response buffer size of approximately 8 KB. Data written to the response output stream is held in this buffer until it reaches capacity. Consequently, if the total size of the initial HTML content is less than the buffer threshold, the server will not transmit any data to the client until the buffer is filled. This buffering behavior introduces a delay in sending the first chunk of content, thereby negating the benefits of progressive rendering. In scenarios where the rendered HTML template does not produce sufficient data to exceed the buffer threshold early, PSSR becomes ineffective, and the client experiences a delayed initial response.

| Listing 1. StreamingResponseBody handler in Spring MVC. |

| @GetMapping("/stream") fun handleStream(): StreamingResponseBody? { return StreamingResponseBody { outputStream -> for (i in 0..9) { val htmlFragment = "<p>Chunk " + i + "</p>\n" outputStream.write(htmlFragment.toByteArray()) outputStream.flush() // ensure partial response is sent Thread.sleep(500) // simulate delay } } } |

2.2.2. Spring WebFlux

Spring WebFlux is a reactive web framework built on a non-blocking, event-driven architecture that enables efficient handling of a large number of concurrent connections with minimal resource usage. Unlike traditional servlet-based stacks that rely on a thread-per-request model, WebFlux operates on reactive runtimes like Netty, where a small, fixed-size event loop manages all I/O events. Incoming HTTP requests are routed to handler functions or annotated controllers, which return reactive types such as Mono<T> and Flux<T>—Publisher implementations provided by the Project Reactor library [26]. These implementations adhere to the reactive streams specification [12], enabling interoperability with other compliant reactive stream libraries. A Mono represents a single asynchronous value (or none) [21], while a Flux represents a stream of zero or more values [24]. I/O-bound tasks such as database queries or external API calls do not occupy threads during execution, enabling the framework to scale gracefully under high load and maintain responsiveness even in resource-constrained environments.

PSSR is natively supported in WebFlux via Flux-based controllers. When a controller returns a Flux<String> or another stream of HTML fragments, WebFlux can begin streaming content to the client as soon as the first elements are emitted.

Listing 2 shows a method that emits one HTML chunk every 500 milliseconds. As each chunk is generated, it is immediately written to the HTTP response, allowing the client to begin rendering content even as more data is still being produced. Unlike StreamingResponseBody in Spring MVC, which is constrained by servlet buffer thresholds and blocking semantics, WebFlux ensures that each emitted item is pushed to the client as soon as the network is ready, without occupying a dedicated thread. Moreover, WebFlux integrates seamlessly with reactive data sources such as R2DBC (Reactive Relational Database Connectivity) and reactive NoSQL drivers, making it possible to build end-to-end non-blocking applications. HTML builders and DSLs used in conjunction with WebFlux must be designed to accommodate reactive streams, ensuring that view generation does not violate the non-blocking contract by performing blocking I/O or awaiting asynchronous operations imperatively.

| Listing 2. Progressive Server-Side Rendering in Spring WebFlux. |

| @GetMapping(value = "/pssr", produces = MediaType.TEXT_HTML_VALUE) public Flux<String> renderChunks() { return Flux.range(1, 10) .delayElements(Duration.ofMillis(500)) .map(i -> "<p>Chunk " + i + "</p>\n"); } |

2.2.3. Quarkus

Quarkus is a modern, cloud-native Java framework that supports both imperative and reactive programming models. It is built on top of Vert.x, which provides a non-blocking, event-driven runtime similar to Netty. Incoming HTTP requests are processed asynchronously on a small, fixed-size event loop thread pool, allowing the framework to handle many concurrent connections efficiently without blocking threads. Quarkus provides support for reactive APIs like Mutiny [28], a modern alternative to Spring Reactor [26]. Like Reactor, Mutiny complies with the Reactive Streams specification [12]. For traditional imperative-style request handling, Quarkus provides integration with JAX-RS [40], where resource methods can return synchronous types or asynchronous constructs such as CompletionStage. To enable PSSR in imperative endpoints, Quarkus leverages the JAX-RS StreamingOutput interface. By returning a StreamingOutput instance, developers can write parts of the HTTP response body incrementally as data becomes available. This approach allows the server to flush HTML fragments progressively to the client, improving the perceived responsiveness especially for long-running or large responses. Like other streaming mechanisms based on servlet buffers, the initial data flush may be delayed until internal buffers (commonly around 8KB) are filled. However, Quarkus allows configuring the buffer size to a smaller value, which can help mitigate this issue.

Listing 3 shows how StreamingOutput can be used to send partial HTML content in chunks, allowing browsers to progressively render the response while the server continues processing. Quarkus’ architecture ensures that the underlying event loop threads are not blocked by these writes, as the framework offloads blocking I/O operations to worker threads. This combination of non-blocking event-driven runtime and incremental response streaming enables efficient PSSR even within imperative programming styles.

| Listing 3. Progressive Server-Side Rendering in Quarkus using StreamingOutput. |

|

@GET @Path("/stream") @Produces(MediaType.TEXT_HTML) public StreamingOutput streamHtml() { return output -> { PrintWriter writer = new PrintWriter(output); for (int i = 1; i <= 5; i++) { writer.println("<p>Chunk " + i + "</p>"); writer.flush(); // Flush each chunk incrementally Thread.sleep(500); // Simulate processing delay } writer.flush(); }; } |

3. Problem Statement

In this section, we examine the challenges of implementing Progressive Server-Side Rendering (PSSR) in modern web applications, with a focus on the limitations of current template engine designs. Our goal is to broaden the range of options available for PSSR, particularly within JVM-based frameworks. In PSSR, the server does not wait for the entire data model to be ready before beginning to render HTML. Instead, it processes and streams each piece of data to the client as soon as it arrives.

Reactive types like Observable<T> of ReactiveX [25] or Kotlin Flow<T> [29] facilitate this by representing data as a sequence of asynchronous events. For example, a reactive stream might emit a sequence of Presentation objects, each representing a talk in a conference schedule. As each Presentation is emitted by the Observable or Flow, the internal DSL-based engine—such as HtmlFlow—can render the corresponding HTML fragment and immediately flush it to the client. This approach is demonstrated in Listing 4, where each presentation is rendered asynchronously as it is emitted by an Observable. Note that the await builder receives an additional parameter, the onCompletion callback, which is used to signal HtmlFlow that it can proceed to render the next HTML element in the web template [4]. HtmlFlow pauses the rendering process until onCompletion is called, similar to how the resume function works in continuations and coroutines [41]. In Listing 5, we show an equivalent suspend-based implementation using Kotlin’s Flow [2]. Both examples highlight how internal DSLs can natively integrate with reactive types to enable non-blocking, progressive rendering on the server side.

| Listing 4. HtmlFlow reactive presentation template in Kotlin with an Observable model. |

| await { div, model, onCompletion -> model .doOnNext { presentation -> presentationFragmentAsync .renderAsync(presentation) .thenApply { frag -> div.raw(frag) } } .doOnComplete { onCompletion.finish() } .subscribe() } |

| Listing 5. HtmlFlow suspend presentation template in Kotlin with a Flow model. |

| suspending { model -> model .toFlowable() .asFlow() .collect { presentation -> presentationFragmentAsync .renderAsync(presentation) .thenApply { frag -> raw(frag) } } } |

By contrast, template engines that use external DSLs—such as JStachio, Thymeleaf, or Handlebars—typically define templates within static HTML documents using custom markers, and rely on blocking interfaces like java.util.Iterable or java.util.stream.Stream. These interfaces require the entire data model, to be materialized in memory before rendering can begin, which blocks server threads during template expansion and significantly limits scalability under high concurrency. Some reactive libraries, such as RxJava, provide bridging mechanisms like Observable.blockingIterable(), which allows asynchronous data sources to be exposed as Iterable by blocking the thread until all items are available. While useful for compatibility with traditional APIs, this approach reintroduces blocking behavior and undermines the benefits of non-blocking I/O—especially under high concurrency. Listing 6 illustrates this model using a JStachio template, where the engine performs a blocking loop over presentationItems.

| Listing 6. Presentation HTML template using JStachio. |

| {{#presentationItems}} <div class="card mb-3 shadow-sm rounded"> <div class="card-header"> <h5 class="card-title"> {{title}} - {{speakerName}} </h5> </div> <div class="card-body"> {{summary}} </div> </div> {{/presentationItems}} |

Despite these performance limitations, external DSLs remain popular due to several advantages:

- 1.

- Separation of Concerns: HTML templates are decoupled from application logic, enabling front-end developers to contribute without modifying back-end code.

- 2.

- Cross-Language Compatibility: External DSLs are portable across languages and frameworks, easing integration in multi-language environments.

- 3.

- Familiarity: Many developers are comfortable with HTML syntax, lowering the barrier to entry and improving maintainability.

These strengths make external DSLs appealing—even when they come at the cost of blocking synchronous rendering. However, this trade-off becomes critical under high concurrency, where blocking threads severely degrades throughput [2]. Emerging features in the Java ecosystem, particularly virtual threads introduced in Java 21 as part of Project Loom [42], offer a promising solution to this challenge. Virtual threads drastically reduce the overhead of blocking operations by decoupling thread execution from OS-level threads. For this reason, engines that rely on blocking interfaces—like those used in external DSLs—can potentially achieve scalability levels that approach those of non-blocking, asynchronous engines.

4. Benchmark Implementation

This benchmark (https://github.com/xmlet/comparing-non-blocking-progressive-ssr, accessed on 29 May 2025) is designed with a modular architecture, separating the view and model layers from the controller layer [43], which allows for easy extension and integration of new template engines and frameworks. It also includes a set of tests to ensure the correctness of implementations and to validate the HTML output. It includes two different data models, defined as Presentation and Stock, as shown in Listings 7 and 8, following the proposal of the benchmarks [44,45]. The Presentation class represents a presentation with a title, speaker name, and summary, while the Stock class represents a stock with a name, URL, symbol, price, change, and ratio.

| Listing 7. Stock class. |

| data class Stock( val name: String, val name2: String, val url: String, val symbol: String, val price: Double, val change: Double, val ratio: Double ) |

| Listing 8. Presentation class. |

| data class Presentation(

val id: Long, val title: String, val speakerName: String, val summary: String ) |

The application’s repository contains a list of 10 instances of the Presentation class and 20 instances of the Stock class. Each list is used to generate a respective HTML view. Although the instances are kept in memory, the repository uses the Observable class from the RxJava library to interleave list items with a delay of 1 millisecond. This delay promotes context switching and frees up the calling thread to handle other requests in non-blocking scenarios, mimicking actual I/O operations.

By using the blockingIterable method of the Observable class, we provide a blocking interface for template engines that do not support asynchronous data models, while still simulating the asynchronous nature of the data source to enable PSSR. Template engines that do not support non-blocking I/O for PSSR include KotlinX, Rocker, JStachio, Pebble, Freemarker, Trimou, and Velocity. HtmlFlow supports non-blocking I/O through suspendable templates and asynchronous rendering, while Thymeleaf enables it using the ReactiveDataDriverContextVariable in conjunction with a non-blocking Spring ViewResolver.

The aforementioned blocking template engines are used in the context of virtual threads or alternative coroutine dispatchers, allowing the handler thread to be released and reused for other requests.

The Spring WebFlux core implementation uses Project Reactor to support a reactive programming model: each method returns a Flux<String> as the response body, which acts as a publisher that progressively streams the HTML content to the client. The implementation includes four main approaches to PSSR:

- Reactive: The template engine is used in a reactive context, where the HTML content rendered using the reactive programming model. An example of this approach is the Thymeleaf template engine when using the ReactiveDataDriverContextVariable in conjunction with a non-blocking Spring ViewResolver.

- Suspendable: The template engine is used in a suspendable context, where the HTML content is rendered within the context of a suspending function. An example of this approach is the HtmlFlow template engine, which supports suspendable templates with the use of the Flow class from the Kotlin standard library.

- Virtual: The template engine is used in a non-blocking context, where the HTML content is rendered within the context of virtual threads. This method is used for the template engines that do not traditionally support non-blocking I/O, be it either because they use external DSLs and in consequence only support the blocking Iterable interface, or because they do not support the asynchronous rendering of HTML content.

- Blocking: The template engine is used in a blocking context, where the HTML content is rendered using the blocking interface of the Observable class, within the context of an OS-thread.

The Spring MVC implementation uses handlers based solely on the blocking interface of the Observable class. To enable PSSR in this context, we utilize the StreamingResponseBody interface, which allows the application to write directly to the response OutputStream without blocking the servlet container thread. According to the Spring documentation (https://docs.spring.io/spring-framework/docs/current/javadoc-api/org/springframework/web/servlet/mvc/method/annotation/StreamingResponseBody.html, accessed on 29 May 2025), this class is a controller method return value type for asynchronous request processing where the application can write directly to the response OutputStream without holding up the Servlet container thread.

In Spring MVC, StreamingResponseBody enables asynchronous writing relative to the request-handling thread, but the underlying I/O remains blocking—specifically the writes to the OutputStream. When using virtual threads, the I/O operations are more efficient when compared to platform threads, as they are executed in the context of a lightweight thread. Most of the computation is performed in a separate thread from the one that receives each request; we use a thread pool TaskExecutor to process requests, allowing the application to scale and handle multiple clients more efficiently as opposed to the default TaskExecutor implementation, which tries to create a thread for each request.

However, the Spring MVC implementation does not effectively support PSSR for these templates, as HTML content is not streamed progressively to the client. This limitation occurs because the response is only flushed to the client once the content written to the OutputStream exceeds the configured output buffer size, as explained in Section 2.2. Consequently, the client receives the complete response only after the entire HTML content has been rendered and buffered, which negates the primary benefits of PSSR—namely, reduced time-to-first-byte and progressive content delivery. Furthermore, Spring MVC does not provide configuration options for the response buffer size, preventing developers from reducing it to smaller values that would enable more frequent flushing and achieve true progressive streaming of HTML content. This architectural constraint makes Spring MVC unsuitable for implementing effective PSSR compared to reactive frameworks like Spring WebFlux.

This implementation includes two main approaches to PSSR:

- Blocking: The template engine is used in a blocking context, where the HTML content is rendered using the blocking interface of the Observable class.

- Virtual: The template engine is used in a non-blocking context, where the HTML content is rendered within the context of virtual threads.

The Quarkus implementation also uses handlers based on the blocking interface of the Observable class. It implements the StreamingOutput interface from the JAX-RS specification to enable PSSR, allowing HTML content to be streamed to the client. While StreamingOutput also uses blocking I/O, it operates on Vert.x worker threads, which prevents blocking of the event loop. When virtual threads are used, the I/O operations are handled efficiently, as they are executed in lightweight threads.

The Quarkus implementation supports PSSR for these templates by configuring the response buffer size in the application.properties file. The default buffer size is 8 KB, but we reduced it to 512 bytes, which allows the response to be sent to the client progressively as the HTML content is rendered.

This implementation includes three main approaches to PSSR:

- Blocking: The template engine is used in a blocking context, where the HTML content is rendered using the blocking interface of the Observable class.

- Virtual: The template engine is used in a non-blocking context, where the HTML content is rendered within the context of virtual threads.

- Reactive: The template engine is used in a reactive context, where the HTML content is rendered using the reactive programming model. In this case, we use the HtmlFlow template engine, which supports asynchronous rendering through the writeAsync method.

5. Results

This section presents the evaluation results organized into four main parts: Section 5.1 details the testing environment and hardware specifications; Section 5.2 presents scalability results for the Presentations data model; Section 5.3 analyzes performance with the more complex Stocks data model; and Section 5.4 provides detailed memory consumption and resource utilization analysis.

5.1. Environment Specifications

All benchmarks were conducted on a GitHub-hosted virtual machine under GitHub Actions (GitHub, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA), running Ubuntu 24.04.2 LTS with an AMD EPYC 7763 64-Core Processor (Advanced Micro Devices, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) operating at 3.24 GHz, configured with two CPU cores and two threads per core, and 7.8 GB of available RAM. The system utilizes a 75 GB SSD with ext4 file system, achieving 1.5 GB/s write throughput in basic I/O tests. Network connectivity is provided through a 1500 MTU Ethernet interface. All tests were conducted on OpenJDK 21 (Corretto build) with the G1 garbage collector enabled by default. The JVM arguments used were: -Xms512m -Xmx16g. Each test was executed five times per configuration to ensure result reliability.

All template engines were configured to use UTF-8 encoding and disable automatic HTML escaping to ensure fair comparison and consistent output across all template engines. Caching behavior was left as the default for each engine, allowing them to optimize template loading and rendering as per their design. These configurations ensure that all engines operate under equivalent conditions, with template loading, encoding, and escaping behavior normalized across implementations.

For both the Apache Bench and JMeter tests, we simulate a 1000-request warm up period for each route with a concurrent user load of 32 users. The warm up period is followed by the actual test period, during which we simulate 256 requests per user, scaling in increments up to 128 concurrent users.

The results are presented in the form of throughput (number of requests per second) for each template engine, with the x-axis representing the number of concurrent users and the y-axis representing the throughput in requests per second.

Both Quarkus and Spring MVC implementations were configured with an 8 KB output buffer size to ensure consistency, despite Quarkus not enabling PSSR at this size and Spring MVC not supporting PSSR for the tested templates. Testing with a reduced 512 B buffer size showed only a 0.046% performance difference with Rocker, indicating negligible impact. Both frameworks use unlimited platform thread pools, enabling on-demand thread creation up to system limits for maximum throughput and scalability observation under high concurrent load.

Since the obtained results for JMeter and Apache Bench show no significant differences, only the JMeter results will be presented. Statistical analysis of test configurations revealed an average absolute percentage difference of 2.83% between the two load testing tools. While individual approach differences ranged from −16.53% to +14.66% at the extremes, the consistent directional bias and small magnitude of differences indicate that both tools provide comparable performance measurements. Given this statistical equivalence and the need for brevity, only JMeter results are presented, as they provide representative performance characteristics across all tested configurations.

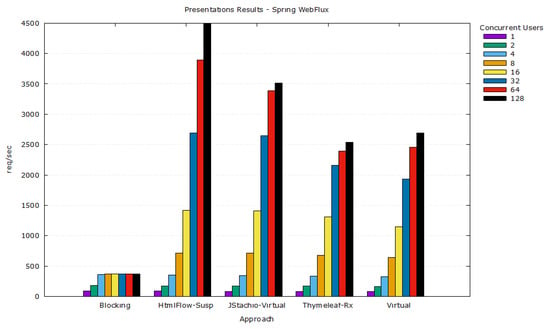

5.2. Scalability Results for the Presentations Class

The results in Figure 2 depict the throughput (number of requests per second) for each template engine, with concurrent users ranging from 1 to 128, from left to right. The benchmarks include HtmlFlow using suspendable web templates (HtmlFlow-Susp, equivalent to the approach shown in Listing 5), JStachio using virtual threads with the Iterable interface (JStachio-Virtual), and Thymeleaf using the reactive View Resolver driver (Thymeleaf-Rx). Blocking and Virtual represent the average throughput of the blocking approaches (i.e., KotlinX, Rocker, JStachio, Pebble, Freemarker, Trimou, HtmlFlow, and Thymeleaf) when run in the context of a separate coroutine dispatcher or virtual threads, respectively.

Figure 2.

Throughput in requests per second (req/sec) for Spring WebFlux using the Presentation class, showing scalability results as the number of concurrent users increases (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128) across different rendering approaches.

We show the HtmlFlow-Susp, JStachio-Virtual, and Thymeleaf-Rx engines separately to observe the performance of the non-blocking engines when using the Suspending, Virtual Thread, and Reactive approaches. The Blocking and Virtual are aggregated due to the similar performance of different engines when using those approaches.

The results in Figure 2 show that when using blocking template engines with a separate coroutine dispatcher, the engines are unable to scale effectively beyond four concurrent users. In contrast, HtmlFlow-Susp scales up to 128 concurrent users, achieving 4487 requests per second. When blocking approaches are executed in the context of virtual threads—thus enabling non-blocking I/O—the engines scale up to 64 concurrent users, with JStachio using virtual threads reaching 3514 requests per second. The Thymeleaf implementation using the reactive View Resolver driver scales up to 32 concurrent users, achieving a lower maximum throughput of 2559 requests per second.

It is important to note that the differences in scalability and throughput between the HtmlFlow-Susp, JStachio-Virtual, and Thymeleaf-Rx approaches may be influenced by the specific template engines used, rather than the approach itself. When comparing the Reactive, Suspendable, and Virtual approaches specifically with HtmlFlow, we found that all three achieve similar performance: HtmlFlow using a blocking approach with virtual threads reaches 4691 requests per second, while HtmlFlow using a reactive approach achieves 4792 requests per second.

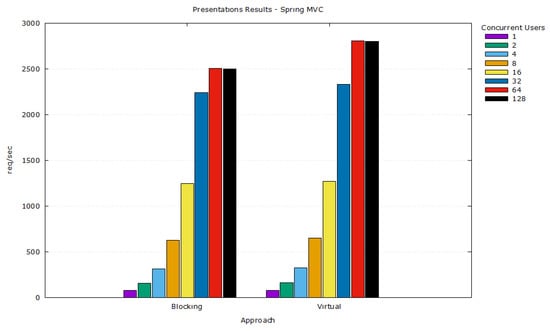

The results for the Spring MVC implementation, shown in Figure 3, compare two synchronous approaches: Blocking, which uses platform threads with StreamingResponseBody, and Virtual, which uses virtual threads. Since Spring MVC follows a thread-per-request architecture, the asynchronous approaches—Reactive and Suspendable—described in Section 4 are not applicable. Both the Blocking and Virtual strategies scale effectively up to 32 concurrent users, with the virtual threads approach achieving a slightly higher maximum throughput of 2797 requests per second, compared to 2498 requests per second for the blocking approach. These results indicate that while Spring MVC can handle a moderate level of concurrency, it does not reach the scalability of the reactive or suspendable approaches available in Spring WebFlux. Furthermore, Spring MVC does not enable Progressive Server-Side Rendering (PSSR) for the tested templates, as previously discussed in Section 4.

Figure 3.

Throughput in requests per second (req/sec) for Spring MVC using the Presentation class, showing scalability results as the number of concurrent users increases (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128) across different rendering approaches.

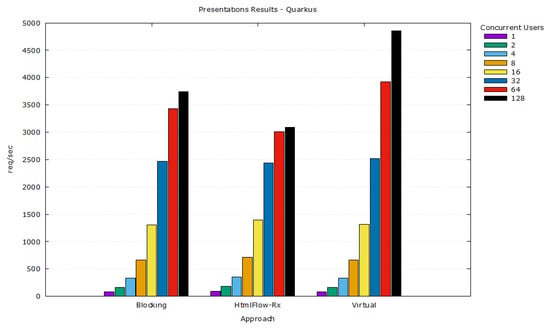

The results for the Quarkus implementation, shown in Figure 4, indicate that Quarkus handles synchronous approaches more efficiently than Spring WebFlux. The blocking engines scale up to 64 concurrent users, achieving up to 3744 requests per second. When using virtual threads, the throughput increases even further, reaching 4856 requests per second, allowing scalability up to 128 users. This demonstrates that Quarkus’s implementation of virtual threads is effective for enabling PSSR, and comparable to the Suspendable and Reactive approaches used in Spring WebFlux in terms of scalability and throughput.

Figure 4.

Throughput in requests per second (req/sec) for Quarkus using the Presentation class, showing scalability results as the number of concurrent users increases (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128) across different rendering approaches.

Additionally, HtmlFlow-Rx, a reactive implementation of the HtmlFlow template engine (equivalent to the approach shown in Listing 4) that utilizes Quarkus’s reactive programming model, achieved a lower throughput than the the Blocking and Virtual approaches—3088 requests per second. This demonstrates that Quarkus’s reactive programming model is effective for enabling PSSR, although it does not achieve the same level of performance or scalability as the same approach in Spring WebFlux, stagnating after 32 concurrent users.

5.3. Scalability Results for the Stocks Class

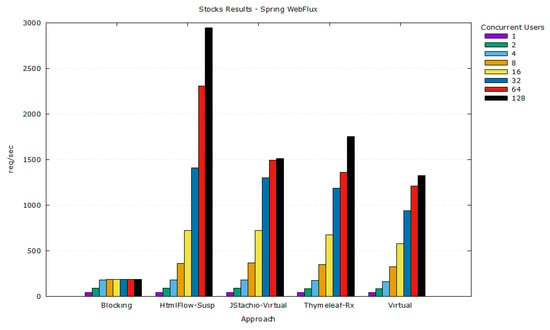

The results in Figure 5 use the same template engines and approaches as the previous benchmark, but with a more complex data model: the Stock class, which includes 20 instances and approximately two times as many data bindings. With this data model, the scalability of the engines remains largely unchanged; however, throughput is reduced across all engines. Compared to the Presentation benchmark, JStachio using virtual threads experienced a more pronounced decrease in performance relative to the Reactive and Suspending approaches, with JStachio using virtual threads now achieving 1509 requests per second, compared to 1750 requests per second achieved by the Thymeleaf implementation using the reactive View Resolver driver.

Figure 5.

Throughput in requests per second (req/sec) for Spring WebFlux using the Stock class, showing scalability results as the number of concurrent users increases (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128) across different rendering approaches.

It is again important to note that the differences in scalability and throughput between the HtmlFlow-Susp, Jstachio-Virtual, and Thymeleaf-Rx approaches may be influenced by the specific template engines used, rather than the approach itself. When comparing the Reactive, Suspendable, and Virtual approaches specifically with HtmlFlow, we found that all three achieve similar performance: HtmlFlow using a blocking approach with virtual threads reaches 3090 requests per second, while HtmlFlow using a reactive approach achieves 3026 requests per second. This indicates that the more pronounced decrease in performance for JStachio using virtual threads is likely due to the specific implementation of the template engine, rather than the use of virtual threads itself.

The overall throughput reduction across all engines is expected, as the Stock class contains more data properties than the Presentation class, adding overhead related to the data binding process of each template engine.

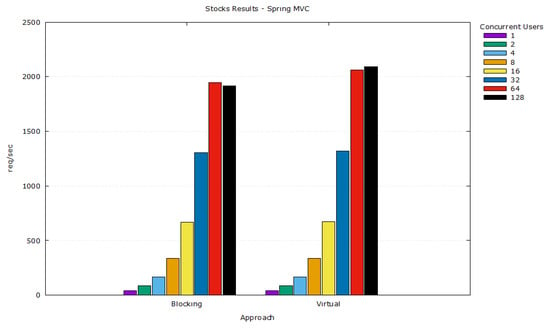

The results shown in Figure 6 indicate that the Spring MVC implementation using the blocking approach with StreamingResponseBody achieves a throughput of up to 1916 requests per second, with no significant improvement observed when using virtual threads. Both approaches scale effectively up to 64 concurrent users. Although these approaches achieve higher throughput in Spring MVC than in Spring WebFlux, their overall performance remains lower than that of the reactive and suspendable approaches.

Figure 6.

Throughput in requests per second (req/sec) for Spring MVC using the Stock class, showing scalability results as the number of concurrent users increases (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128) across different rendering approaches.

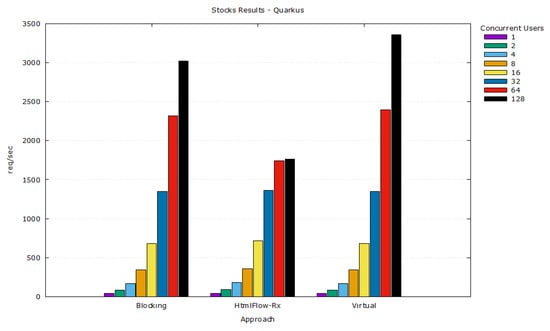

The results depicted in Figure 7 show that the Quarkus synchronous approaches scale effectively up to 128 concurrent users, achieving performance comparable to the Spring WebFlux implementation. The blocking approach reaches a throughput of 3019 requests per second, while the virtual threads approach achieves a throughput of 3357 requests per second. In addition to the synchronous engines, the HtmlFlow-Rx approach also achieves a throughput of 1760 requests per second, indicating that this approach achieves lower performance in Quarkus than in Spring WebFlux, where it reached 3026 requests per second, as previously mentioned.

Figure 7.

Throughput in requests per second (req/sec) for Quarkus using the Stock class, showing scalability results as the number of concurrent users increases (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128) across different rendering approaches.

The results of the benchmarks show that non-blocking engines—whether using reactive programming, Kotlin coroutines, or Java virtual threads—are able to scale effectively, supporting between 32 and 128 concurrent users depending on the approach and framework. Out of all the tested frameworks, Spring WebFlux showed itself the most effective at enabling PSSR, mostly due to its native support for publish–subscribe interfaces, allowing for content to be streamed as data becomes available, instead of when the response buffer is flushed. Quarkus also enabled PSSR effectively, but it required additional configuration of the OutputBuffer size to achieve the same results as Spring WebFlux. The Spring MVC implementation, on the other hand, did not enable PSSR for the tested templates.

However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of our chosen data models for generalizability. The tested templates used relatively simple data structures with limited nesting and straightforward property bindings. Real-world applications often involve deeply nested data structures, complex conditional logic, and iterative rendering over thousands of items. Under such conditions, we anticipate significantly different performance characteristics: increased memory consumption due to object traversal overhead, higher CPU utilization for complex evaluations, and altered scalability patterns where non-blocking approaches may become more advantageous. The performance degradation observed with our Stock class benchmark—which merely doubled the number of properties—suggests that higher template complexity would result in substantially higher performance degradation. Future work should investigate these scenarios with more realistic data models to better understand performance boundaries and optimization strategies for complex PSSR implementations.

5.4. Memory Consumption and Resource Utilization Analysis

This section evaluates the memory and CPU resource usage characteristics of structured concurrency approaches, specifically comparing virtual threads and suspendable coroutines.

Resource utilization data was collected using VisualVM during 30 s benchmark runs, capturing detailed CPU and memory usage patterns under sustained load conditions. Each profiling session monitored system performance during the 1 to 128 concurrent user load test, providing comprehensive insights into runtime behavior.

Virtual Threads vs. Structured Concurrency

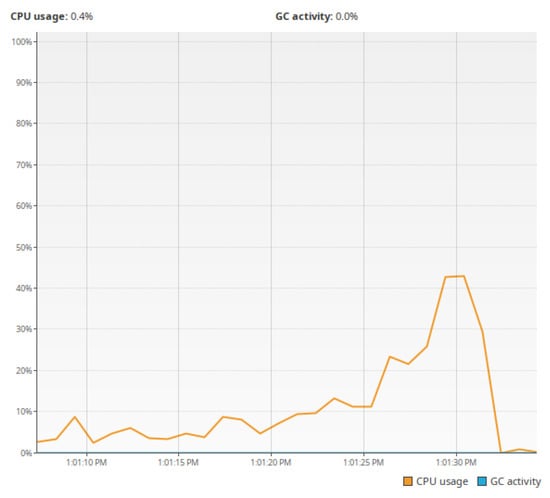

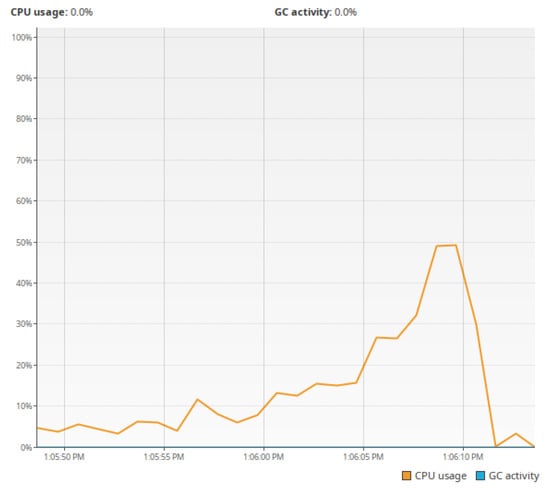

Figure 8 and Figure 9 show CPU utilization profiles for the HtmlFlow-Virtual and HtmlFlow-Susp implementations, respectively. The subsequent gradual increase in CPU utilization reflects the ramp-up of concurrent users during the benchmark. HtmlFlow-Virtual exhibits a distinctive bell-shaped curve, rapidly climbing from near-zero to peak CPU usage of around 50% during the sustained load phase, maintaining moderate utilization during the test period, and then dropping sharply back to baseline. HtmlFlow-Susp displays a similar pattern but with a slightly lower peak CPU utilization of approximately 42%, showing marginally lower intensive CPU usage during the sustained load phase. Both profiles demonstrate comparable resource consumption patterns, with the virtual thread implementation showing only slightly higher CPU demands. The GC activity indicators in both profiles remain relatively low throughout the test duration, confirming that garbage collection overhead does not significantly impact CPU utilization in either approach.

Figure 8.

CPU utilization profiling with HtmlFlow-Susp in Spring WebFlux during 30 s load test.

Figure 9.

CPU utilization profiling with HtmlFlow-Virtual in Spring WebFlux during 30 s load test.

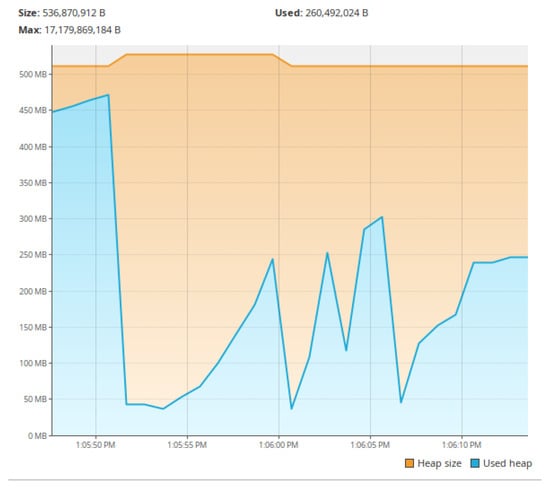

Figure 10 and Figure 11 show similar memory usage for both approaches, with peaks around 300 MB during load. The initial spike to 450 MB in both graphs corresponds to the applications’ bootstrapping phase. Overall, these results indicate that under the tested conditions, virtual threads and suspendable coroutines exhibit comparable memory consumption.

Figure 10.

Memory utilization and garbage collection behavior with HtmlFlow-Susp in Spring WebFlux during 30 s load test.

Figure 11.

Memory utilization and garbage collection behavior with HtmlFlow-Virtual in Spring WebFlux during 30 s load test.

Virtual threads allocate a full call stack per thread, which is unmounted and stored on the heap when suspended (e.g., during blocking I/O). In contrast, Kotlin coroutines compile into state machines that capture only the minimal execution state needed to resume computation. This typically allows coroutines to scale more efficiently in terms of memory usage, especially under high concurrency.

6. Discussion

Beronić et al. [46] compared different structured concurrency constructs in Java and Kotlin in the context of a multi-threaded HTTP server. Their benchmark scenario differs from ours: their server awaited incoming requests and, upon receiving one, executed a task involving object creation, writing the object’s information to a file, and returning the data as a response. Consistent with our findings, they concluded that both Kotlin’s coroutines and Java’s virtual threads offer significant performance improvements over traditional JVM-based threads in concurrent applications.

Our results diverge from theirs regarding memory usage. They reported lower heap usage for Java virtual threads (16–64 MB) compared to Kotlin coroutines (52–99 MB), which contrasts with our measurements. This discrepancy may be attributed to the different workloads: while their benchmark includes a single I/O read–write operation per request, our experiments focus exclusively on read-only I/O tasks.

The work of Navarro et al. [47] focused on the performance of Quarkus, which relies on Eclipse Vert.x [48], itself built on top of Netty [49]. This represents a similar environment to the one evaluated in our experiments with Quarkus. Their study also emphasized template rendering, using a blocking HTML template engine (Qute). The benchmark they employed is the Fortunes test (https://www.techempower.com/benchmarks, accessed on 29 May 2025), which involves rendering a simple HTML table with only two data bindings per row.

Their results show that Quarkus with virtual threads outperformed the traditional thread-per-request model under increased concurrency. Moreover, compared to the reactive model, virtual threads demonstrated competitive performance, particularly when executing blocking operations within template engines. In contrast, our experiments revealed that the reactive approach in Spring WebFlux performs better than virtual threads in the same experiment conducted with Quarkus, suggesting that WebFlux provides a more efficient infrastructure for managing reactive processing flows.

The work of Šimatović et al. [50] presents an evaluation of Java virtual threads under different garbage collectors. They explored three types of workloads, only one of which was based on a web application scenario. This scenario replicated large-scale web scraping by executing 1000 parallel tasks, each consisting of an I/O-bound operation followed by CPU-bound string processing.

In this workload, garbage collection activity remained low across all collectors, indicating reduced memory pressure. These findings suggest that virtual threads improve memory allocation efficiency and reduce the frequency of garbage collection cycles—particularly when used with concurrent garbage collectors.

Our observations suggest that the choice between virtual threads and suspendable coroutines should be guided by both runtime behavior and development constraints. Virtual threads offer the compelling advantage of preserving synchronous programming semantics while achieving competitive performance across moderate to high-load scenarios—a significant benefit for teams migrating existing codebases or working with legacy template engines. Suspendable coroutines, while requiring developers to adopt asynchronous programming paradigms, may provide greater efficiency in scenarios involving high concurrency, deeper call stacks, or highly dynamic workloads.

The framework-specific variations observed in our results—particularly the performance differences between Spring WebFlux and Quarkus implementations—suggest that the underlying reactive runtime architecture significantly influences the effectiveness of each approach. This finding underscores the importance of considering not only the concurrency model but also the specific framework ecosystem when making architectural decisions for PSSR implementations.

7. Conclusions

In recent decades, non-blocking I/O has become the standard approach for building highly responsive and scalable web servers. However, traditional synchronous programming models are not compatible with non-blocking APIs, which typically rely on callback-based conventions such as continuation-passing style (CPS) [20] or promises [21]. These approaches not only hinder sequential readability but also increase code verbosity, making them more error-prone. Alternatives like the async/await idiom [22] or suspend functions [23] simplify asynchronous programming by mimicking a sequential style without blocking threads. Recent proposals [2,4] have applied contemporary asynchronous idioms to SSR web templates, demonstrating how they can overcome the scalability bottlenecks present in traditional web template engines.

As an alternative, Java virtual threads can be applied to any blocking I/O call, leveraging the Java runtime to transparently intercept and convert it into non-blocking I/O, without requiring any changes to the calling code or exposing its internal complexities. In this work, we explored how this technique can be applied to traditional web template engines and whether it can achieve performance competitive with reactive approaches provided by frameworks such as Thymeleaf [51] and HtmlFlow [5]. Our benchmarks across Spring WebFlux, Spring MVC, and Quarkus show that synchronous non-blocking execution using virtual threads consistently delivers performance comparable to asynchronous non-blocking approaches under high concurrency. These findings highlight virtual threads as a promising alternative to complex asynchronous programming models, offering a simpler development experience without compromising scalability or responsiveness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.P. and F.M.C.; methodology, B.P. and F.M.C.; software, B.P. and F.M.C.; validation, B.P. and F.M.C.; formal analysis, B.P. and F.M.C.; investigation, B.P. and F.M.C.; resources, B.P. and F.M.C.; data curation, B.P. and F.M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, B.P. and F.M.C.; writing—review and editing, B.P. and F.M.C.; supervision, F.M.C.; project administration, F.M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not involve human subjects or personal data; therefore, Institutional Review Board approval was not required.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in Github at https://github.com/xmlet/comparing-non-blocking-progressive-ssr, accessed on 29 May 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Edgar, M. First Contentful Paint. In Speed Metrics Guide: Choosing the Right Metrics to Use When Evaluating Websites; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2024; pp. 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.M. Progressive Server-Side Rendering with Suspendable Web Templates. In Web Information Systems Engineering—WISE 2024; Barhamgi, M., Wang, H., Wang, X., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 458–473. [Google Scholar]

- Elmeleegy, K.; Chanda, A.; Cox, A.L.; Zwaenepoel, W. Lazy Asynchronous I/O for Event-Driven Servers. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on USENIX Annual Technical Conference, ATEC ’04, Boston, MA, USA, 27 June –2 July 2004; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, F.M.; Fialho, P. Enhancing SSR in Low-Thread Web Servers: A Comprehensive Approach for Progressive Server-Side Rendering with Any Asynchronous API and Multiple Data Models. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies, WEBIST ’23, Rome, Italy, 15–17 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, F.M. HtmlFlow Java DSL toWrite Typesafe HTML. Technical Report. 2017. Available online: https://htmlflow.org/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Fernández, D. Thymeleaf. Technical Report. 2011. Available online: https://www.thymeleaf.org/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Fowler, M. Domain Specific Languages; Addison-Wesley Professional: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, M. Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture; Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Alur, D.; Malks, D.; Crupi, J. Core J2EE Patterns: Best Practices and Design Strategies; Prentice Hall PTR: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Parr, T.J. Enforcing Strict Model-View Separation in Template Engines. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on World Wide Web, WWW ’04, New York, NY, USA, 17–20 May 2004; pp. 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasner, G.E.; Pope, S. A Description of the Model-View-Controller User Interface Paradigm in the Smalltalk80 System. J. Object-Oriented Program. 1988, 1, 26–49. [Google Scholar]

- Netflix; Pivotal; Red Hat; Oracle; Twitter; Lightbend. Reactive Streams Specification. Technical Report. 2015. Available online: https://www.reactive-streams.org/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Landin, P.J. The next 700 programming languages. Commun. ACM 1966, 9, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, E.; Fowler, M. Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, K. Programming Techniques: Regular Expression Search Algorithm. Commun. ACM 1968, 11, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resig, J. Pro JavaScript Techniques; Apress: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hors, A.L.; Hégaret, P.L.; Wood, L.; Nicol, G.; Robie, J.; Champion, M.; Arbortext; Byrne, S. Document Object Model (DOM) Level 3 Core Specification. Technical Report. 2004. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/2004/REC-DOM-Level-3-Core-20040407/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Carvalho, F.M.; Duarte, L.; Gouesse, J. Text Web Templates Considered Harmful. In Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 69–95. [Google Scholar]

- Landin, P.J. Correspondence Between ALGOL 60 and Church’s Lambda-notation: Part I. Commun. ACM 1965, 8, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, G.; Steele, G. Scheme: An Interpreter for Extended Lambda Calculus; AI Memo No. 349; MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman; Wise. Aspects of Applicative Programming for Parallel Processing. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1978, C-27, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syme, D.; Petricek, T.; Lomov, D. The F# Asynchronous Programming Model. In Practical Aspects of Declarative Languages; Rocha, R., Launchbury, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Elizarov, R.; Belyaev, M.; Akhin, M.; Usmanov, I. Kotlin coroutines: Design and implementation. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM SIGPLAN International Symposium on New Ideas, New Paradigms, and Reflections on Programming and Software, Chicago, IL, USA, 20–22 October 2021; pp. 68–84. [Google Scholar]