Digital Credit and Debt Traps: Behavioral and Socio-Cultural Drivers of FinTech Indebtedness in Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. FinTech-Based Loan

2.2. Financial Behavior Bias

2.3. Culture

2.4. Emotions

2.5. Materialism

2.6. Financial Literacy

2.7. Job Security

2.8. Religiosity

2.9. Literature Gap

2.10. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Respondent Profile

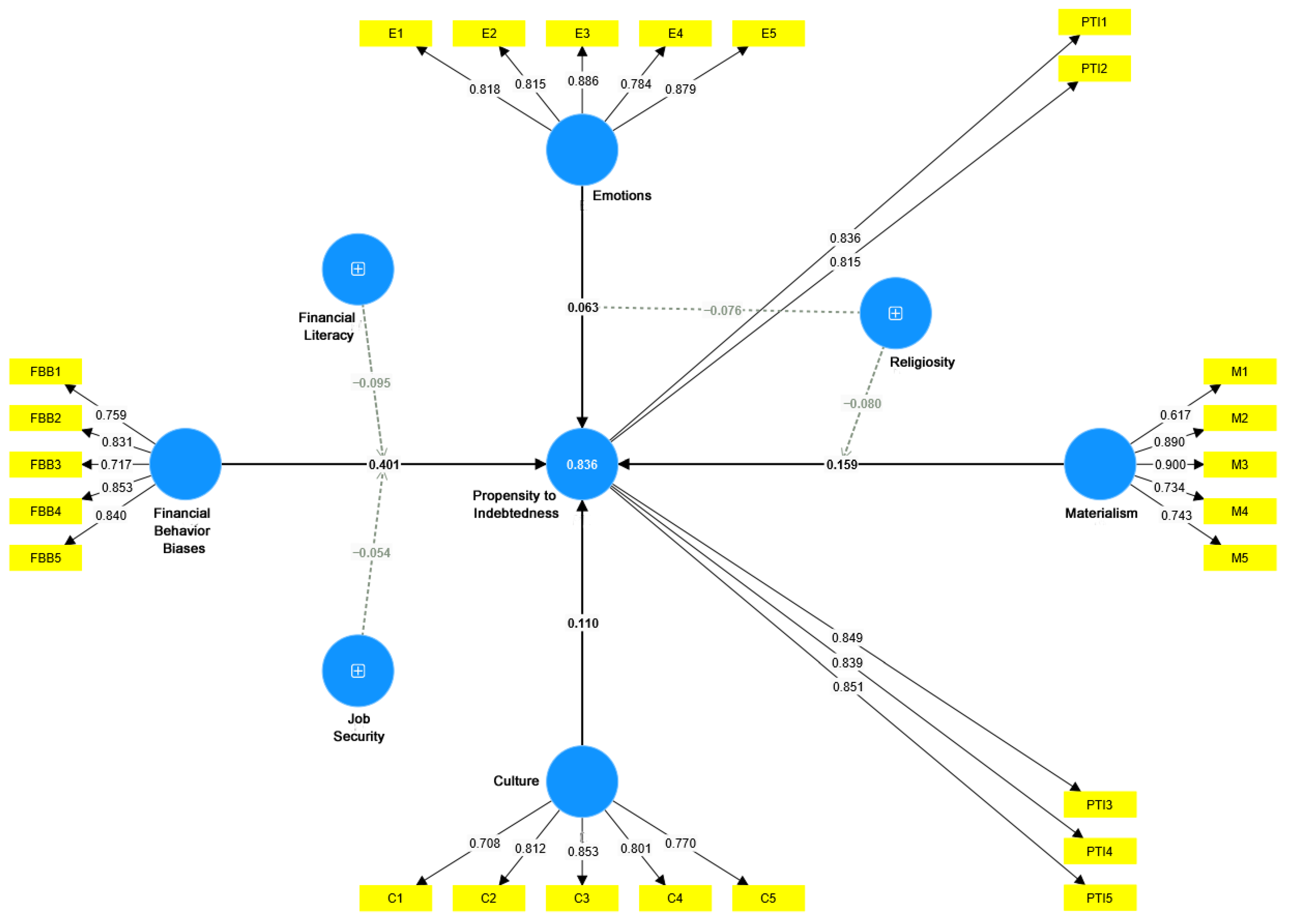

4.2. Measurement Model Evaluation

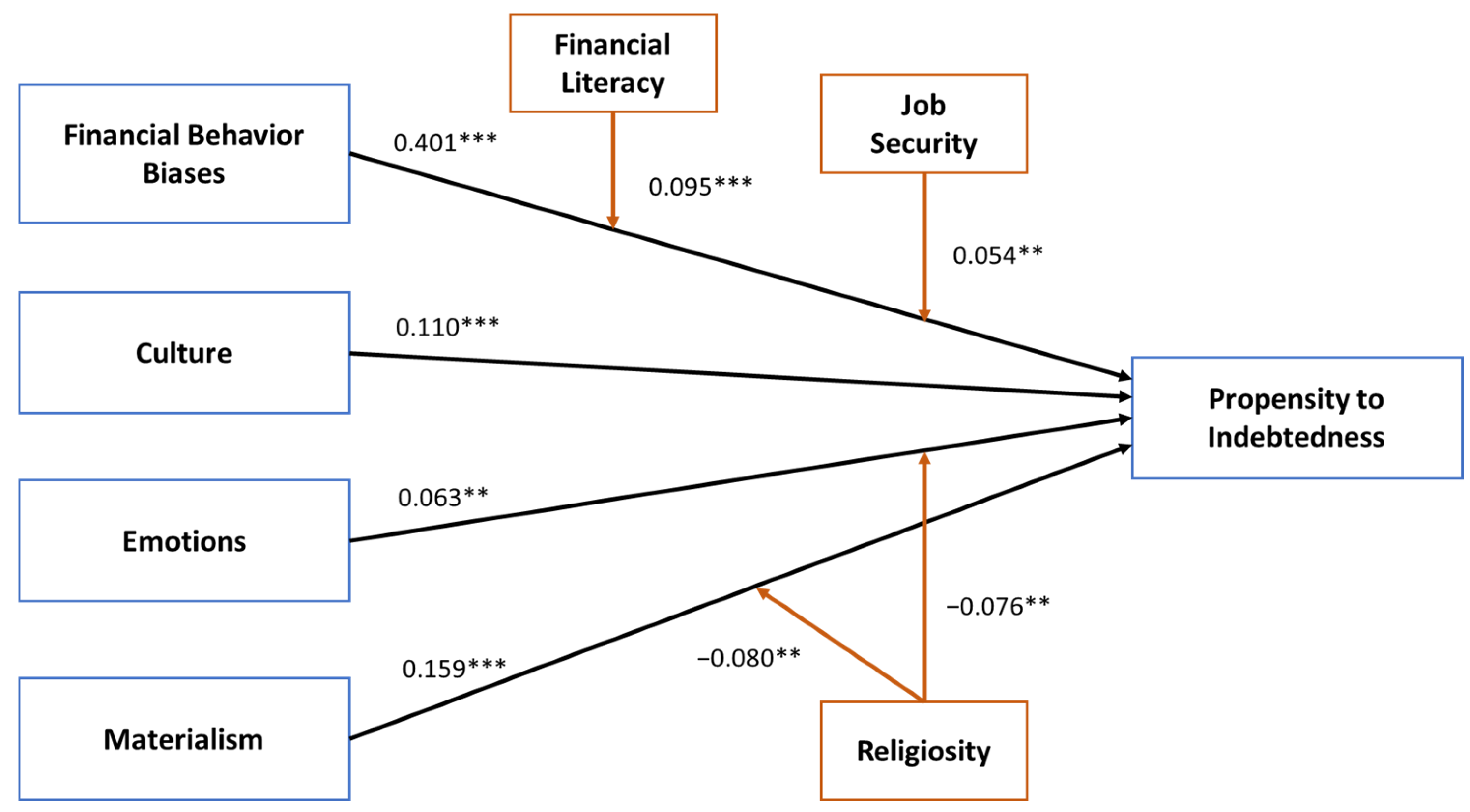

4.3. Structural Model Results

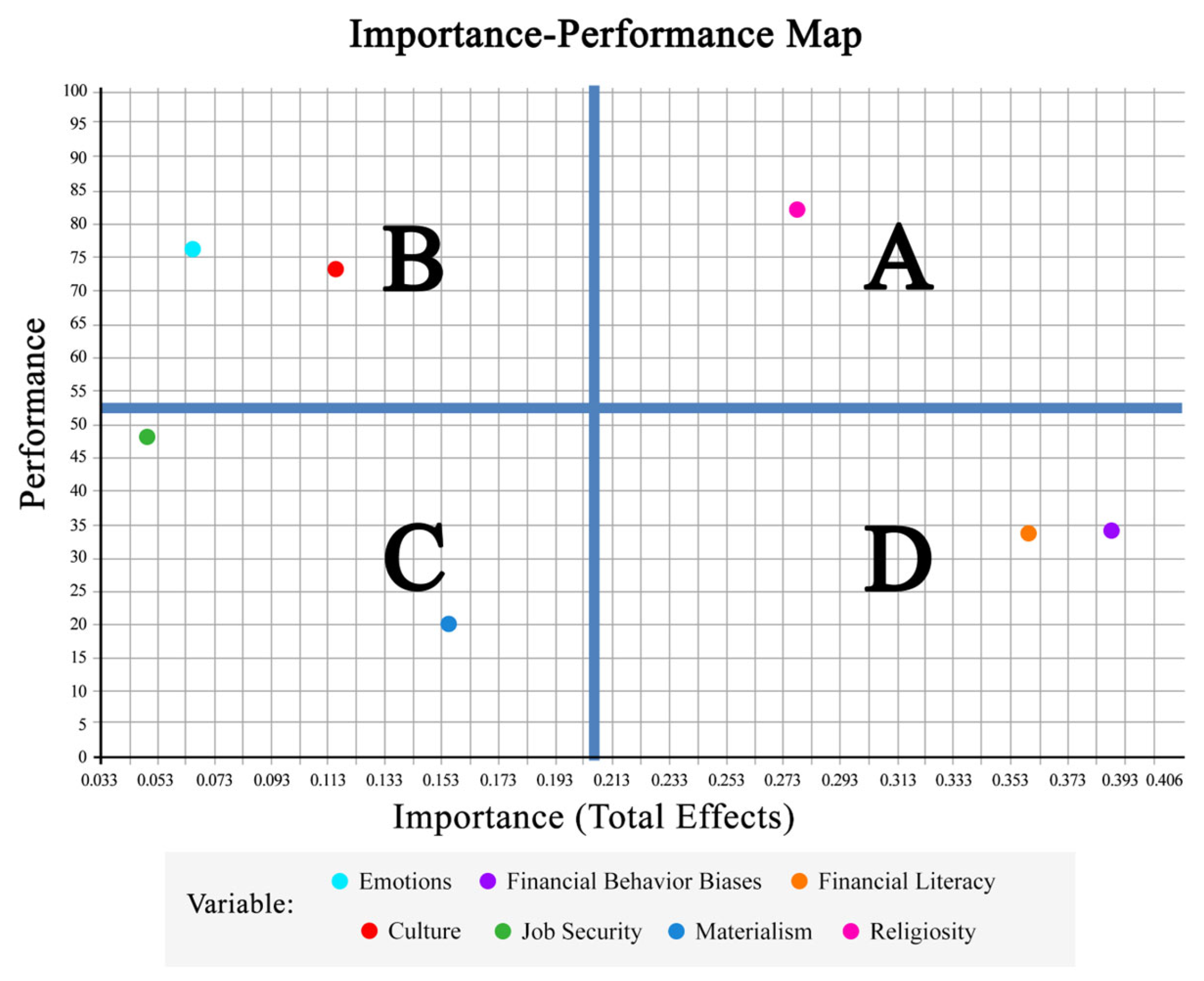

4.4. Importance–Performance Mapping Analysis (IPMA)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cumming, D.J.; Sewaid, A. FinTech Loans, Self-Employment, and Financial Performance; Center for Financial Studies (CFS), Goethe University Frankfurt: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danisewicz, P.; Elard, I. The Real Effects of Financial Technology: Marketplace Lending and Personal Bankruptcy. J. Bank. Financ. 2023, 155, 106986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croux, C.; Jagtiani, J.; Korivi, T.; Vulanovic, M. Important Factors Determining Fintech Loan Default: Evidence from a Lendingclub Consumer Platform. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2020, 173, 270–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.P.; Jagtiani, J.; Moon, C.-G. Consumer Lending Efficiency: Commercial Banks Versus a Fintech Lender. Financ. Innov. 2022, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRU-OJK. Financing Institutions, Venture Capital, Fintech P2P Lending and Micro Finance Industry Update December 2024. Available online: https://iru.ojk.go.id/iru/dataandstatistics/detaildataandstatistics/13379/financing-institutions-venture-capital-fintech-p2p-lending-and-micro-finance-industry-update-december-2024 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- IRU-OJK. Indonesia Financial Sector Development Q4 2023; IRU-OJK: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jakpat. Indonesia Fintech Trends—1st Semester of 2024; Jakpat: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, N.M.; Mendiratta, P.; Kashiramka, S. FinTech Credit: Uncovering Knowledge Base, Intellectual Structure and Research Front. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2023, 41, 1769–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, T.; Lu, X. Social Media Meets FinTech Platforms: How Do Online Emotions Support Credit Risk Decision-Making? Decis. Support Syst. 2025, 195, 114471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, D.; Hanspal, T.; Liao, Y.; Liu, Y. Cultivating Self-Control in FinTech: Evidence from a Field Experiment on Online Consumer Borrowing. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2022, 57, 2208–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, M.; Maçada, A.C.G.; de Oliveira Santini, F.; Rasul, T. Continuance Intention in Financial Technology: A Framework and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2023, 41, 749–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, D. Unraveling Youth Indebtedness in China: A Case Study Based on the “Debtors Avengers” Community on Douban. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2024, 12, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azma, N.; Rahman, M.; Adeyemi, A.A.; Rahman, M.K. Propensity Toward Indebtedness: Evidence from Malaysia. Rev. Behav. Financ. 2019, 11, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J.S.; Li, Y.; Valdesolo, P.; Kassam, K.S. Emotion and Decision Making. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 799–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M.L. Materialism, Transformation Expectations, and Spending: Implications for Credit Use. J. Public Policy Mark. 2011, 30, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliyas, M.A.; Kumar, P.K. Personalization in the FinTech Age. In Financial Innovation for Global Sustainability; Afjal, M., Birau, R., Eds.; Scrivener Publishing: Beverly, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 249–279. ISBN 9781394311682. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, L.; Yang, Q.; Yu, P.S. Data Science and AI in FinTech: An Overview. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2021, 12, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Azma, N.; Masud, M.A.; Ismail, Y. Determinants of Indebtedness: Influence of Behavioral and Demographic Factors. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2020, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarz, M.; Adamek, J. Trust and Personal Innovativeness as the Prerequisites for Using Digital Lending Services Offered by FinTech Lenders. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Skłodowska Sect. H—Oeconomia 2023, 57, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, D.; Tiwary, D. Early Warning System Model for Non-Performing Loans of Emerging Market Fintech Firms BT. In Financial Markets, Climate Risk and Renewables, Proceedings of Conference on Pathways to Sustainable Economy—A Banking and Finance Perspective (SEBF), IIT Bombay, India, 6–7 October 2023; Mohapatra, S., Padhi, P., Singh, V., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 221–240. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, T.; Yang, Y.S.; Xiao, S.; Park, B. Il What Makes Consumers Trust and Adopt Fintech? An Empirical Investigation in China. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 24, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rahim, R.; Bohari, S.A.; Aman, A.; Awang, Z. Benefit–Risk Perceptions of FinTech Adoption for Sustainability from Bank Consumers’ Perspective: The Moderating Role of Fear of COVID-19. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guan, Z.; Hou, F.; Li, B.; Zhou, W. What Determines Customers’ Continuance Intention of FinTech? Evidence from YuEbao. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2019, 119, 1625–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Ji, J.; Sun, H.; Xu, H. Legal Enforcement and Fintech Credit: International Evidence. J. Empir. Financ. 2023, 72, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelli, G.; Frost, J.; Gambacorta, L.; Jagtiani, J. The Impact of Fintech Lending on Credit Access for U.S. Small Businesses. J. Financ. Stab. 2024, 73, 101290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Leung, H.; Liu, L.; Qiu, B. Consumer Behaviour and Credit Supply: Evidence from an Australian FinTech Lender. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 57, 104205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banasaz, M.; Bose, N.; Sedaghatkish, N. Identification of Loan Effects on Personal Finance: A Case for Small U.S. Entrepreneurs. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2025, 234, 106982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Marisetty, V.B. Are FinTech Lending Apps Harmful? Evidence from User Experience in the Indian Market. Br. Account. Rev. 2023, 101269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlando, A.; Kuhn, M.A.; Prina, S. Too Fast, Too Furious? Digital Credit Delivery Speed and Repayment Rates. J. Dev. Econ. 2025, 174, 103427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodula, M. Does FinTech Credit Substitute for Traditional Credit? Evidence from 78 Countries. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 46, 102469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hou, S.; Kyaw, K.; Xue, X.; Liu, X. Exploring the Determinants of FinTech Credit: A Comprehensive Analysis. Econ. Model. 2023, 126, 106422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, S.K.; Prasad, S. Present Bias and Its Influence on Financial Behaviours Amongst Indians. IIM Ranchi J. Manag. Stud. 2025, 4, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayad, K.; Touil, A.; El Hamidi, N.; Bennani, K.D. Does Behavioral Biases Matter in SMEs’ Borrowing Decisions? Insights from Morocco. Banks Bank Syst. 2024, 19, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, F.S.; Harizan, S.H.M. Behavioral Biases and Credit Card Repayments Among Malaysians. Int. J. Bank. Financ. 2023, 18, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Hewege, C.; Perera, C. Exploring the Relationships Between Behavioural Biases and the Rational Behaviour of Australian Female Consumers. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsonziwa, K.; Fanta, A. Over-Indebtedness and Its Welfare Effect on Households. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2019, 10, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodell, J.W.; Kumar, S.; Lahmar, O.; Pandey, N. A Bibliometric Analysis of Cultural Finance. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 85, 102442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogolin, F.; Dowling, M.; Cummins, M. Individual Values and Household Finances. Appl. Econ. 2017, 49, 3560–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Tanner, E.C.; Marquart, N.A.; Zhao, D. We Are Not All the Same: The Influence of Personal Cultural Orientations on Vulnerable Consumers’ Financial Well-Being. J. Int. Mark. 2022, 30, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.; Shin, F.; Lawless, R.M. Attitudes, Behavior, and Institutional Inversion: The Case of Debt. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 120, 1117–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarreal, R.; Peterson, R.A. The Concept and Marketing Implications of Hispanicness. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2009, 17, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitokoto, H. Indebtedness in Cultural Context: The Role of Culture in the Felt Obligation to Reciprocate. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 19, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henchoz, C.; Coste, T.; Wernli, B. Culture, Money Attitudes and Economic Outcomes. Swiss J. Econ. Stat. 2019, 155, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izard, C.E. The Many Meanings/Aspects of Emotion: Definitions, Functions, Activation, and Regulation. Emot. Rev. 2010, 2, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.F. The Dark Side of Emotion: The Addiction Perspective. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 753, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, C.; Vandone, D. Impulsivity and Household Indebtedness: Evidence from Real Life. J. Econ. Psychol. 2011, 32, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, G.; Banks, M.; Zhang, J. The Role of Human Emotion in Decisions About Credit: Policy and Practice Considerations. Crit. Policy Stud. 2018, 12, 428–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, S.A.M.; Vieira, K.M. Propensity Toward Indebtedness: An Analysis Using Behavioral Factors. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2014, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Siddiqui, D.A. Does Materialism, Emotions, Risk and Financial Literacy Affects the Propensity for Indebtedness in Pakistan: The Complementary Role of Hedonism and Demographics; SSRN Working Paper; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.B.; de Almeida, F.; Soro, J.C.; Herter, M.M.; Pinto, D.C.; Silva, C.S. On the Relation Between Over-Indebtedness and Well-Being: An Analysis of the Mechanisms Influencing Health, Sleep, Life Satisfaction, and Emotional Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 591875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rendall, S.; Brooks, C.; Hillenbrand, C. The Impacts of Emotions and Personality on Borrowers’ Abilities to Manage Their Debts. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 74, 101703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maison, D.; Adamczyk, D. The Relations Between Materialism, Consumer Decisions and Advertising Perception. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 176, 2526–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.J. The Relationship of Materialism to Spending Tendencies, Saving, and Debt. J. Econ. Psychol. 2003, 24, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garðarsdóttir, R.B.; Dittmar, H. The Relationship of Materialism to Debt and Financial Well-Being: The Case of Iceland’s Perceived Prosperity. J. Econ. Psychol. 2012, 33, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, V.A.; Jasrotia, S.S.; Rai, S.S. Intensifying Materialism Through Buy-Now Pay-Later (BNPL): Examining the Dark Sides. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2024, 42, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Matos, C.A.; Vieira, V.; Bonfanti, K.; Mette, F.M.B. Antecedents of Indebtedness for low-Income Consumers: The Mediating Role of Materialism. J. Consum. Mark. 2019, 36, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD-INFE. Measuring Financial Literacy: Core Questionnaire in Measuring Financial Literacy: Questionnaire and Guidance Notes for Conducting an Internationally Comparable Survey of Financial Literacy; OECD: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gerth, F.; Lopez, K.; Reddy, K.; Ramiah, V.; Wallace, D.; Muschert, G.; Frino, A.; Jooste, L. The Behavioural Aspects of Financial Literacy. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, D.; McKillop, D. Financial Literacy and Over-Indebtedness in Low-Income Households. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2016, 48, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.; Singh, Y.; Ansari, M.S. How Financial Literacy Moderate the Association Between Behaviour Biases and Investment Decision? Asian J. Account. Res. 2022, 7, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potrich, A.C.G.; Vieira, K.M. Demystifying Financial Literacy: A Behavioral Perspective Analysis. Manag. Res. Rev. 2018, 41, 1047–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.S.; Ahmed, A.D.; Richards, D.W. Financial Literacy and Financial Well-Being of Australian Consumers: A Moderated Mediation Model of Impulsivity and Financial Capability. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2021, 39, 1377–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdzan, N.S.; Zainudin, R.; Shaari, M.S. The Influence of Religious Belief and Psychological Factors on Borrowing Behaviour Among Malaysian Public Sector Employees. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2022, 15, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebdaoui, H.; Chetioui, Y. Antecedents of Consumer Indebtedness in a Majority-Muslim Country: Assessing the Moderating Effects of Gender and Religiosity Using PLS-MGA. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2021, 29, 100443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, T.; Suresha, B.; Prakash, N.; Vazirani, K.; Krishna, T.A. Digital Financial Literacy Among Adults in India: Measurement and Validation. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2132631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaimovic, A.; Torlakovic, A.; Arnaut-Berilo, A.; Zaimovic, T.; Dedovic, L.; Nuhic Meskovic, M. Mapping Financial Literacy: A Systematic Literature Review of Determinants and Recent Trends. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, R.; Fazal, A.; Andleeb, R. Behavioral Biases and FinTech Adoption: Investigating the Role of Financial Literacy. Acta Psychol. 2025, 257, 105065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Nieto, B.; Serrano-Cinca, C.; de la CuestaߚGonzález, M. A Multivariate Study of Over-Indebtedness’ Causes and Consequences. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, G.M.Y.; Ossei Kwakye, T.; Duah, H. The Propensity Towards Indebtedness and Savings Behaviour of Undergraduate Students: The Moderating Role of Financial Literacy. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2024, 16, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, H.T.; Nguyen, L.T.H. Consumer Adoption Intention Toward FinTech Services in a Bank-Based Financial System in Vietnam. J. Financ. Regul. Compliance 2022, 32, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galariotis, E.; Monne, J. Basic Debt Literacy and Debt Behavior. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 88, 102673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetti, C.; Madia, M.; Moretti, L. Job Insecurity and Financial Distress; Quaderni—Working Paper DSE, 887; Dipartimento di Scienze Economiche (DSE), Alma Mater Studiorum—Università di Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta, M.B.; Budría, S.; Moro-Egido, A.I. Job Insecurity, Debt Burdens and Individual Health; IZA Discussion Papers, 12663; Institute of Labor Economics (IZA): Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, V.K.G.; Sng, Q.S. Does Parental Job Insecurity Matter? Money Anxiety, Money Motives, and Work Motivation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To, W.M.; Gao, J.H.; Leung, E.Y.W. The Effects of Job Insecurity on Employees’ Financial Well-Being and Work Satisfaction Among Chinese Pink-Collar Workers. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020982993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, M. Job Security Perceptions and the Saving Behavior of German Households; Ruhr Economic Paper, 380; Leibniz Institute for Economic Research: Essen, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Basyouni, S.S.; El Keshky, M.E.S. Job Insecurity, Work-Related Flow, and Financial Anxiety in the Midst of COVID-19 Pandemic and Economic Downturn. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 632265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshman, S.D.; Sussman, A.B.; Vazquez-Hernandez, C.; O’Leary, D.; Trueblood, J.S. The Effect of Job Loss on Risky Financial Decision-Making. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2412760121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamek, J.; Solarz, M. Adoption Factors in Digital Lending Services Offered by FinTech Lenders. Oeconomia Copernic. 2023, 14, 169–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainol, Z.; Daud, Z.; Nizam, A.N.H.K.; Rashid, R.A.; Alias, N. Exploring Factors that Contribute to Individual Indebtedness Among Young Muslims. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2016, 6, 320–328. [Google Scholar]

- Siyal, S.; Ahmad, R.; Ali, S. Debt Trap Dynamics: The Moderating Role of Convenience, Financial Literacy, and Religiosity in Credit Card Usage. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, T. Religion and Emotion Regulation: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies. J. Relig. Health 2025, 64, 2083–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishkin, A.; Ben-Nun Bloom, P.; Schwartz, S.H.; Solak, N.; Tamir, M. Religiosity and Emotion Regulation. J. Cross. Cult. Psychol. 2019, 50, 1050–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeniaras, V. Unpacking the Relationship Between Materialism, Status Consumption and Attitude to Debt: The Role of Islamic Religiosity. J. Islam. Mark. 2016, 7, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarofim, S.; Minton, E.; Hunting, A.; Bartholomew, D.E.; Zehra, S.; Montford, W.; Cabano, F.; Paul, P. Religion’s Influence on the Financial Well-Being of Consumers: A Conceptual Framework and Research Agenda. J. Consum. Aff. 2020, 54, 1028–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, F.S. Behavioral Biases and Over-Indebtedness in Consumer Credit: Evidence from Malaysia. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2025, 13, 2449191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, G.; Smit, E.M. Materialism and Indebtedness of Low Income Consumers: Evidence from South Africa’s Largest Credit Granting Catalogue Retailer. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 41, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Granić, A. The Technology Acceptance Model: 30 Years of TAM, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN 978-3-030-45274-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefrin, H.M.; Thaler, R.H. The Behavioral Life-Cycle Hypothesis. Econ. Inq. 1988, 26, 609–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritika; Kishor, N. Development and Validation of Behavioral Biases Scale: A SEM Approach. Rev. Behav. Financ. 2020, 14, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrawi, S.A.; Aldossry, T.M. Consumer Culture and Its Relationship to Saudi Family Financial Planning. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetioui, Y.; Butt, I.; Lebdaoui, H. Facebook Advertising, eWOM and Consumer Purchase Intention-Evidence from a Collectivistic Emerging Market. J. Glob. Mark. 2021, 34, 220–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, J.F.; de Oliveira, S. Culture and Decision Making. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2016, 136, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusardi, A.; Tufano, P. Debt Literacy, Financial Experiences and Overindebtedness; Working Paper 14808; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, A.; Tufano, P. Debt Literacy, Financial Experiences, and Overindebtedness. J. Pension Econ. Financ. 2015, 14, 332–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blotenberg, I.; Richter, A. Validation of the QJIM: A Measure of Qualitative Job Insecurity. Work Stress 2020, 34, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, T.M. Development and Validation of the Job Security Index and the Job Security Satisfaction Scale: A Classical Test Theory and IRT Approach. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2003, 76, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, K.M.; Matheis, T.K.; Maciel, A.M. Risky Indebtedness Behavior: Impacts on Financial Preparation for Retirement and Perceived Financial Well-Being. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, L.; Botelho, D. Hope, Perceived Financial Risk and Propensity for Indebtedness. Braz. Adm. Rev. 2012, 9, 454–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Gain More Insight from Your PLS-SEM Results: The Importance-Performance Map Analysis. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1865–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Item | Measurement | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial behavior bias | FBB1 | I often make financial decisions without careful consideration. | Hamid [86]; Ritika and Kishor [91]; Zainol et al. [80] |

| FBB2 | I frequently purchase goods due to the influence of others or advertisements. | ||

| FBB3 | I often regret after making impulsive (unplanned) purchases. | ||

| FBB4 | I consider it important to prepare a budget before making expenditures. | ||

| FBB5 | I often make purchases based on emotions rather than logic. | ||

| Culture | C1 | My family habits or traditions influence my financial decisions. | Bahrawi and Aldossry [92]; Chetioui et al. [93]; Yates and de Oliveira [94] |

| C2 | I often follow the shopping habits of my family or friends. | ||

| C3 | Social norms influence the way I manage money. | ||

| C4 | I feel it is important to own items similar to those around me. | ||

| C5 | I feel social pressure to purchase certain goods. | ||

| Emotions | E1 | I feel stressed when I have debt. | Azma et al. [13]; Rahman et al. [18] |

| E2 | I often purchase goods to improve my mood. | ||

| E3 | I feel happy after making large purchases. | ||

| E4 | I feel guilty after making unplanned purchases. | ||

| E5 | My emotions frequently influence my financial decisions. | ||

| Materialism | M1 | I often feel satisfied after purchasing new items. | Azma et al. [13]; Flores et al. [48] |

| M2 | Owning luxury goods is very important to me. | ||

| M3 | I believe that material wealth is a measure of success. | ||

| M4 | I frequently buy items that I do not really need. | ||

| M5 | I am willing to go into debt to purchase luxury goods. | ||

| Financial literacy | FL1 | Imagine that the interest rate on your savings account is 1% per year and inflation is 2% per year. After one year, will you be able to buy more than today, the same as today, or less than today with the money in the account? | Lusardi and Tufano [95,96] |

| FL2 | If the inflation rate is 3% per year and your savings earn an interest of 2% per year, after one year will your money buy more, the same, or less than today? | ||

| FL3 | Suppose you want to invest your money. Which of the following is the best way to reduce investment risk? | ||

| FL4 | If market interest rates rise, what will happen to the price of existing bonds in the market? | ||

| FL5 | You have a balance of IDR 1,000,000 on your credit card with an annual interest rate of 18%, and you make no payments at all. How much debt will you owe after one year? | ||

| FL6 | Suppose in 2024, your income doubles and the prices of all goods also double. In 2024, how much can you buy with your income compared to today? | ||

| Job security | JS1 | I feel that my current job provides me with stability. | Blotenberg and Richter [97]; Probst [98] |

| JS2 | I can remain in my current job for as long as I wish. | ||

| JS3 | I feel secure in my job stability as long as my performance meets expectations. | ||

| JS4 | I am not worried about my future career in this company/organization. | ||

| JS5 | I feel that there is no threat of losing my job in this company/organization. | ||

| Religiosity | R1 | If I had to choose between attending a religious event or a free concert of my favorite musician, I would choose to attend the concert. | Mahdzan [63]; Zainol [80] |

| R2 | I always pray before starting any activity. | ||

| R3 | The distribution of my time between routine activities and religious activities in a 24 h period is … | ||

| R4 | Before making any decision, I pray and seek guidance from my spiritual leader. | ||

| R5 | I believe in the individual right to change one’s religion. | ||

| Propensity toward indebtedness | PTI1 | I am likely to use a fintech loan app even if I am unsure how I will repay the loan. | Azma et al. [13]; Vieira et al. [99]; Barros and Botelho [100] |

| PT12 | I often use fintech lending platforms for small purchases that I cannot afford in cash. | ||

| PTI3 | Even when I do not urgently need money, I consider borrowing through digital loans. | ||

| PTI4 | I believe I will be able to repay fintech loans, even when I am uncertain about my income next month. | ||

| PTI5 | I have used or considered using multiple fintech loan applications simultaneously. |

| Characteristics | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 210 | 52.5% |

| Female | 190 | 47.5% | |

| Age | <25 years old | 16 | 4.0% |

| 26–30 years old | 24 | 6.0% | |

| 31–35 years old | 56 | 14.0% | |

| 36–40 years old | 92 | 23.0% | |

| 41–45 years old | 77 | 19.3% | |

| 46–50 years old | 85 | 21.3% | |

| 51–55 years old | 29 | 7.3% | |

| >55 years old | 21 | 5.3% | |

| Occupation | Civil Servant | 273 | 68.3% |

| Private Employee or Entrepreneur | 127 | 31.8% | |

| Monthly income | <IDR 5,000,000 | 103 | 25.8% |

| IDR 5,000,001–IDR 10,000,000 | 234 | 58.5% | |

| IDR 10,000,001–IDR 15,000,000 | 38 | 9.5% | |

| >IDR 15,000,000 | 25 | 6.3% |

| Variable | Item | Outer Loadings | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial behavior biases | FBB1 | 0.759 | 0.860 | 0.900 | 0.643 |

| FBB2 | 0.831 | ||||

| FBB3 | 0.717 | ||||

| FBB4 | 0.853 | ||||

| FBB5 | 0.840 | ||||

| Culture | C1 | 0.708 | 0.849 | 0.892 | 0.624 |

| C2 | 0.812 | ||||

| C3 | 0.853 | ||||

| C4 | 0.801 | ||||

| C5 | 0.770 | ||||

| Emotions | E1 | 0.818 | 0.893 | 0.921 | 0.701 |

| E2 | 0.815 | ||||

| E3 | 0.886 | ||||

| E4 | 0.784 | ||||

| E5 | 0.879 | ||||

| Materialism | M1 | 0.617 | 0.850 | 0.887 | 0.615 |

| M2 | 0.890 | ||||

| M3 | 0.900 | ||||

| M4 | 0.734 | ||||

| M5 | 0.743 | ||||

| Financial literacy | FL1 | 0.832 | 0.881 | 0.910 | 0.628 |

| FL2 | 0.788 | ||||

| FL3 | 0.747 | ||||

| FL4 | 0.844 | ||||

| FL5 | 0.801 | ||||

| FL6 | 0.735 | ||||

| Job security | JS1 | 0.762 | 0.831 | 0.880 | 0.596 |

| JS2 | 0.836 | ||||

| JS3 | 0.771 | ||||

| JS4 | 0.713 | ||||

| JS5 | 0.772 | ||||

| Religiosity | R1 | 0.878 | 0.920 | 0.940 | 0.758 |

| R2 | 0.901 | ||||

| R3 | 0.887 | ||||

| R4 | 0.834 | ||||

| R5 | 0.851 | ||||

| Propensity toward indebtedness | PTI1 | 0.836 | 0.894 | 0.922 | 0.702 |

| PTI2 | 0.815 | ||||

| PTI3 | 0.849 | ||||

| PTI4 | 0.839 | ||||

| PTI5 | 0.851 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. C | ||||||||||||

| 2. E | 0.049 | |||||||||||

| 3. FBB | 0.357 | 0.260 | ||||||||||

| 4. FL | 0.109 | 0.437 | 0.708 | |||||||||

| 5. JS | 0.892 | 0.131 | 0.385 | 0.171 | ||||||||

| 6. M | 0.678 | 0.378 | 0.209 | 0.138 | 0.899 | |||||||

| 7. PTI | 0.306 | 0.359 | 0.899 | 0.822 | 0.310 | 0.113 | ||||||

| 8. R | 0.182 | 0.270 | 0.567 | 0.517 | 0.137 | 0.077 | 0.757 | |||||

| 9. FBB × FL | 0.026 | 0.082 | 0.152 | 0.258 | 0.046 | 0.030 | 0.039 | 0.037 | ||||

| 10. FBB × JS | 0.039 | 0.033 | 0.186 | 0.046 | 0.046 | 0.046 | 0.020 | 0.017 | 0.022 | |||

| 11. E × R | 0.048 | 0.052 | 0.074 | 0.146 | 0.018 | 0.081 | 0.225 | 0.187 | 0.204 | 0.073 | ||

| 12. M × R | 0.018 | 0.063 | 0.065 | 0.061 | 0.078 | 0.037 | 0.024 | 0.034 | 0.119 | 0.462 | 0.240 |

| Metric | Construct | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient of Determination | Propensity toward indebtedness | R2 = 0.831 | Substantial explanatory power |

| Effect Size | Financial behavior biases | f2 = 0.421 | Large effect |

| Culture | f2 = 0.020 | Small effect | |

| Emotions | f2 = 0.016 | Small effect (below threshold) | |

| Materialism | f2 = 0.057 | Small-to-medium effect | |

| Financial literacy | f2 = 0.324 | Medium-to-large effect | |

| Job security | f2 = 0.005 | Negligible effect | |

| Religiosity | f2 = 0.310 | Medium-to-large effect | |

| Financial behavior biases ×financial literacy | f2 = 0.046 | Small effect | |

| Financial behavior biases × job security | f2 = 0.017 | Small effect (below threshold) | |

| Emotions × religiosity | f2 = 0.028 | Small effect | |

| Materialism × religiosity | f2 = 0.036 | Small effect | |

| Predictive Relevance | Propensity toward indebtedness | Q2 = 0.568 | Strong predictive relevance |

| Relationship | Path Coefficient | t-Value | p-Value | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Financial behavior bias → Propensity toward indebtedness | 0.401 | 8.862 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2 | Culture → Propensity toward indebtedness | 0.110 | 2.682 | 0.004 | Supported |

| H3 | Emotions → Propensity to indebtedness | 0.063 | 2.273 | 0.012 | Supported |

| H4 | Materialism → Propensity to indebtedness | 0.159 | 3.433 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5 | Financial behavior biases ×financial literacy → Propensity to indebtedness | 0.095 | 3.415 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H6 | Financial behavior biases × job security → Propensity to indebtedness | 0.054 | 2.075 | 0.019 | Supported |

| H7 | Emotions × religiosity → Propensity to indebtedness | −0.076 | 1.859 | 0.032 | Supported |

| H8 | Materialism × religiosity → Propensity to indebtedness | −0.080 | 1.690 | 0.046 | Supported |

| Variable | Construct Importance | Construct Performances |

|---|---|---|

| Financial behavior biases | 0.389 | 33.947 |

| Culture | 0.116 | 73.037 |

| Emotions | 0.065 | 76.129 |

| Materialism | 0.155 | 20.179 |

| Financial literacy | 0.360 | 33.420 |

| Job security | 0.050 | 48.064 |

| Religiosity | 0.278 | 81.915 |

| Average | 0.202 | 52.384 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Warokka, A.; Sartika, D.; Aqmar, A.Z. Digital Credit and Debt Traps: Behavioral and Socio-Cultural Drivers of FinTech Indebtedness in Indonesia. FinTech 2025, 4, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/fintech4040062

Warokka A, Sartika D, Aqmar AZ. Digital Credit and Debt Traps: Behavioral and Socio-Cultural Drivers of FinTech Indebtedness in Indonesia. FinTech. 2025; 4(4):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/fintech4040062

Chicago/Turabian StyleWarokka, Ari, Dewi Sartika, and Aina Zatil Aqmar. 2025. "Digital Credit and Debt Traps: Behavioral and Socio-Cultural Drivers of FinTech Indebtedness in Indonesia" FinTech 4, no. 4: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/fintech4040062

APA StyleWarokka, A., Sartika, D., & Aqmar, A. Z. (2025). Digital Credit and Debt Traps: Behavioral and Socio-Cultural Drivers of FinTech Indebtedness in Indonesia. FinTech, 4(4), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/fintech4040062