Abstract

Three years after its emergence, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) continues to be a leading cause of worldwide morbidity and mortality. This systematic review comprises relevant case reports that discuss non-multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (non-MIS-C) and postacute sequalae of COVID-19 (PASC) in the paediatric population, also known as long COVID syndrome. The study aims to highlight the prevalent time interval between COVID-19 and the development of non-MIS-C post-infectious sequalae (PIS). Databases were searched for studies that met our inclusion and exclusion criteria. The final screening revealed an equal sex distribution where the commonest age intervals were school-age and adolescence, with 38% of the patients being older than six years. Interestingly, hospital admission during the course of COVID-19 was not a predictor of the subsequent PASC; forty-nine patients (44.9%) were hospitalized while sixty patients (55.1%) were not hospitalized. Moreover, the most predominant time interval between COVID-19 and the developing PASC was within 14 days from the start of COVID-19 infection (61%). These findings suggest a crucial link between COVID-19 and immune PIS in the paediatric population, especially those older than six years. Accordingly, follow-up and management are encouraged in case of unusual symptoms and signs following COVID-19 infection, regardless of the COVID-19 infection severity.

1. Introduction

Acute infections are typically defined as self-limiting infections usually lasting less than six months and that usually lead to either complete resolution or death. While many studies cover the typical short-lived course and prognosis of acute infectious diseases, the link between acute infections and chronic disability remains understudied. Consequently, many patients suffering from the long-lasting sequelae of acute infections can easily be wrongly diagnosed or wrongly treated. Furthermore, there is insufficient data relating to postacute infection sequelae (PAIS) since many cases—especially those that are sporadic—remain unrecognized. Postacute sequelae (PAS) are symptoms that occur during the postacute phase of an illness. While the exact definition of the postacute phase is largely debatable and differs from one virus species to another, it is generally known as the phase after the virus becomes no longer detectable by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [1,2,3,4].

It is not unusual for acute infections to cause fleeting autoimmune symptoms due to disturbances in the innate and adaptive immune signalling pathways. Rarely, however, acute infections can progress to established autoimmune diseases. The main pathogenesis behind this progression is the molecular mimicry of pathogens or the structural similarity between pathogenic proteins and self-proteins, which causes the autoactivation of self-reactive immune cells in some susceptible individuals. Furthermore, viral attacks lead to the release of intracellular components, which, in turn, cause the activation of the innate immune system, the formation of autoantibodies, the stimulation of antigen-presenting cells, and the migration of immune cells to the site of damage [5,6,7,8].

In general, postinfectious sequelae (PIS) can be divided into three broad subtypes based on the time interval between the infection and the sequelae and the duration of the PIS. PIS can be rapidly developing, such as in the case of reactive arthritis, which normally occurs 1–2 weeks after an infection in susceptible individuals. PIS can also take the form of chronic inflammation following nonpersistent viruses, such as in the case of the reovirus, rotavirus A, which causes coeliac disease, an autoimmune disease triggered by gluten. However, the usual pattern is short-lived autoimmunity developing 4 weeks after the infection and does not persist for more than 6 months. Guillain–Barré Syndrome (GBS), idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), and poststreptococcal immune complications are common examples of this pattern [9,10,11].

Ever since the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus has quickly become an important focus of research. Due to the atypical cytokine release and immune system dysfunction following a COVID-19 infection, postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) have appeared in several cases, and such conditions have become known as ‘long COVID’. Previous inflammatory conditions, advanced age, and obesity are all known risk factors. Just like its predecessors, severe acute respiratory syndrome 1 (SARS-CoV-1) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), the COVID-19 virus can cause symptoms such as fatigue, and dermatological and gastroenterological symptoms. In a recent study, 30% of COVID-19 patients suffered from the persistence of these symptoms, even after the virus became undetectable by PCR [12].

One of the commonest immune sequelae of COVID-19 is a multi-inflammatory syndrome of children, which mimics Kawasaki disease with a more fulminant, yet more reversible course. It usually presents with myocarditis and/or coronary dilatation and responds to treatment with intravenous immunoglobulins. It has gained most of the attention in retrospective, cross-sectional studies as well as in systematic reviews [13].

We choose, in this review, to study immune sequelae developing outside the frame of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), hence the term non-MIS-C postacute sequelae of COVID-19. This systematic review aimed to demonstrate all case reports of non-MIS-C PIS of COVID-19 and to determine the prevalent time interval between acute infection and the development of PIS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Databases Used

A literature search was performed in PubMed, Google Scholar, Google Search, and Scopus.

2.2. Search Terms Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- 1.

- Diagnoses

The following terms and inclusion criteria were included in the search: “COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2” (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) AND “Autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis”, “Diabetes” OR “type 1 diabetes”, “Systemic Lupus Erythematosus” OR “Lupus Erythematosus Disseminatus” OR “Lupus Erythematosus, Systemic”, “Haemolytic–uremic syndrome”, “Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis”, “Familial Mediterranean Fever”, “Autoimmune thyroid disease” OR “subacute thyroiditis”, “Autoimmune hepatitis”, “ANCA vasculitis” (anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody), “Tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome”, “ITP”, “HLH” (haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis), “Psoriasis”, “Guillain–Barré”, “Multiple Sclerosis” OR “ADEM” (acute disseminated encephalomyelitis) AND “Paediatrics” OR “Children”.

- 2.

- Age: 0–18 Years

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- −

- Any case with a multi-inflammatory syndrome of children (MIS-C) or Kawasaki disease was excluded, and any flare-up of a pre-existing autoinflammatory condition was excluded.

- −

- Any case not addressing the outcome parameters was excluded.

2.2.3. Outcome Parameters

The main outcome parameters were the age, sex of the included cases, the interval between COVID-19 and the subsequent autoimmune sequelae, and the need for hospitalization during COVID-19 infection that preceded the resultant autoimmune sequelae.

3. Statistical Analyses

For statistical purposes, age was classified into four ranges: 0–2 years (infants), 3–5 years (preschool children), 6–12 years (school-aged children), and 13–18 years (adolescents).

Furthermore, the interval between COVID-19 and subsequent autoimmune sequelae was classified into three intervals: 0–14 days (immediate), 15–28 days (classic), and >28 days (delayed).

Patients were categorized according to the aforementioned age ranges and time intervals as well as the need for hospital admission during COVID-19 and sex. The number and percentage of patients in each category of each outcome parameter were determined, and a comparison between different categories of each outcome parameter was implemented using a chi-square test and illustrated as a pie chart.

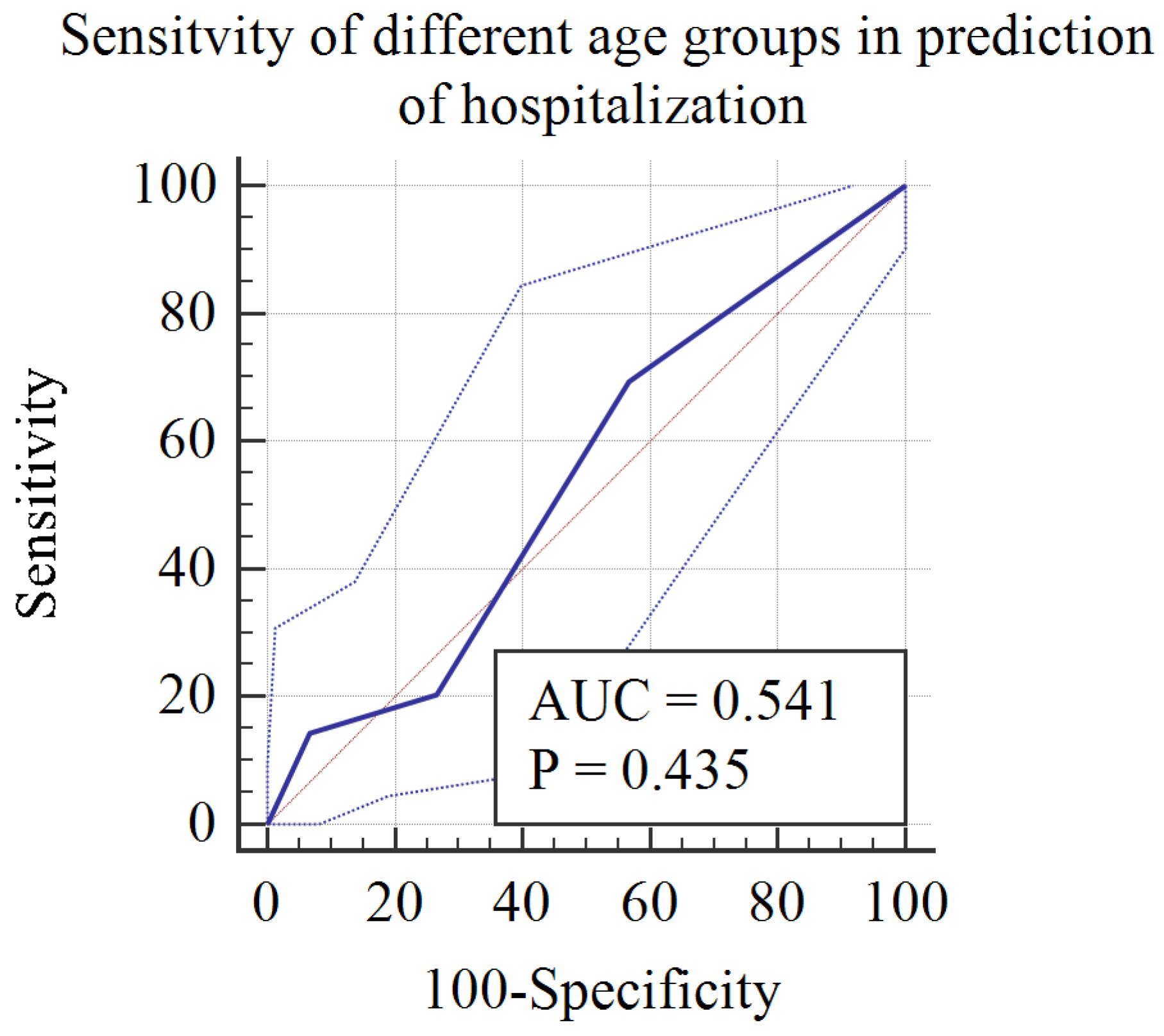

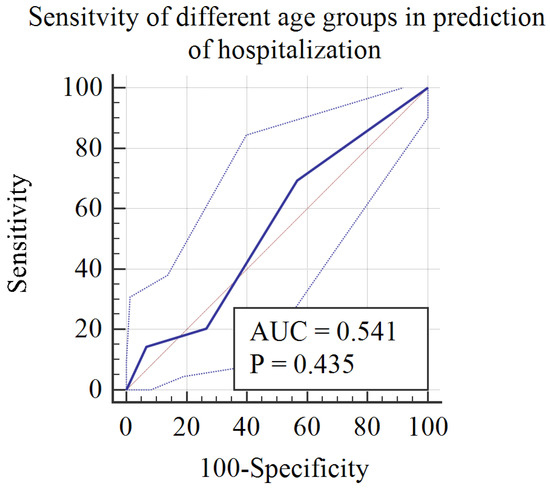

Age categories were numbered as follows: Category 1: infancy (<2 y), Category 2: preschool children (3–5 y), Category 3: school children (6–12 y), Category 4: adolescents (13–18 y). A receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was performed where hospitalization was the classification variable, to measure the age categories predicting hospitalization in the context of non-MIS-C postacute sequelae.

4. Results

We gathered a total of 78 reports of autoimmune sequelae following COVID-19, comprising a collective total of 109 patients. (References included in individual results).

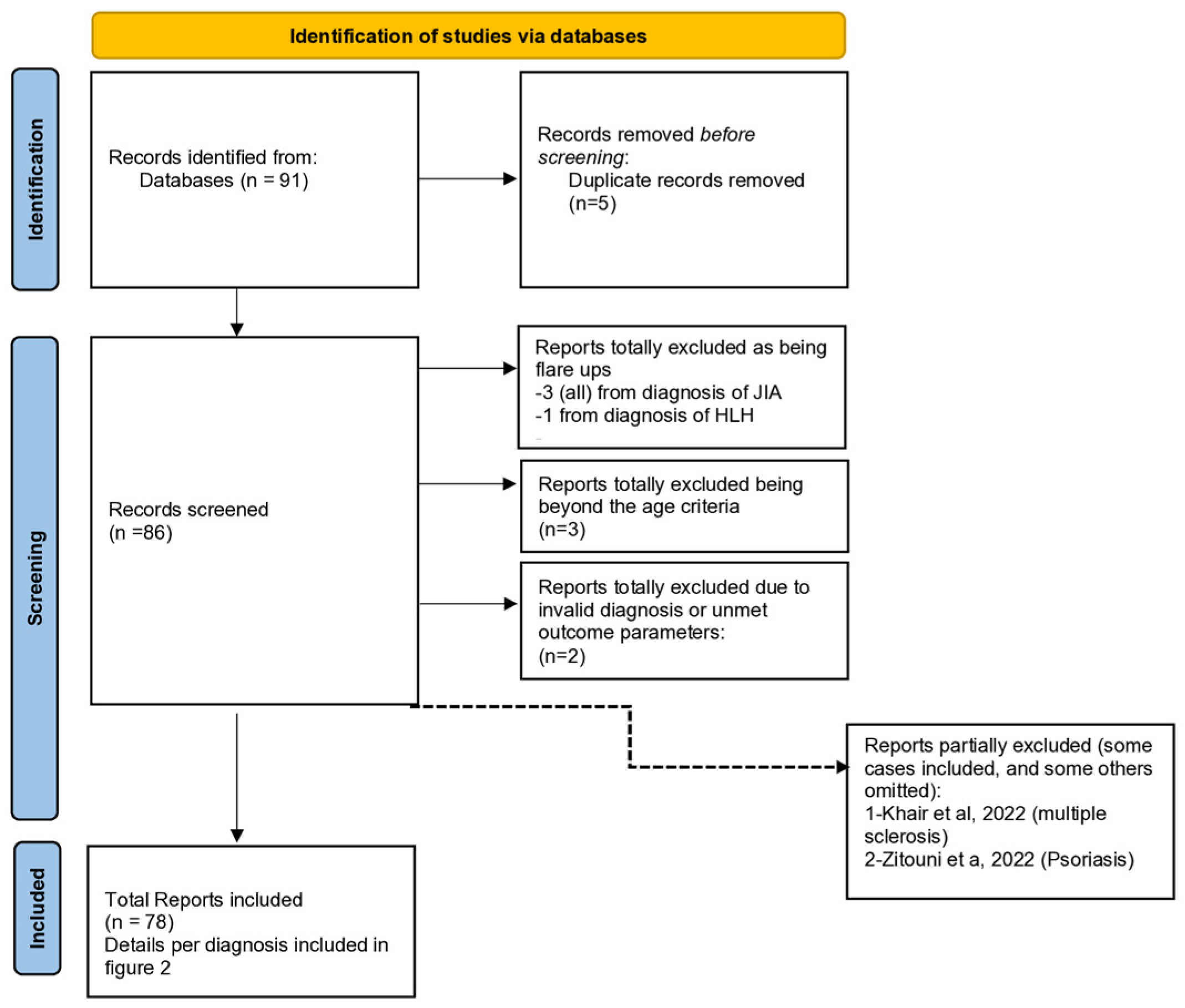

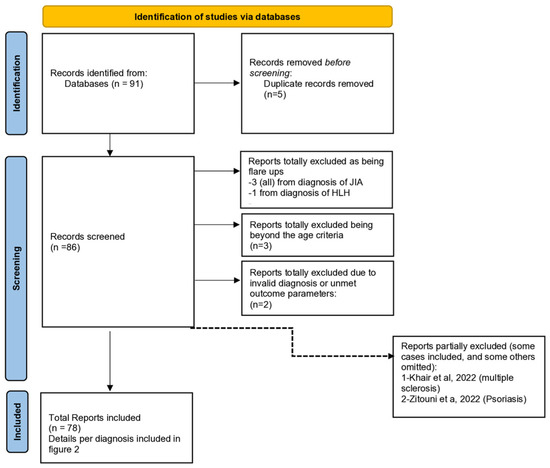

Figure 1 is a preferred reporting item for systemic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) flow charts.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for our systematic review to show the study selection process.

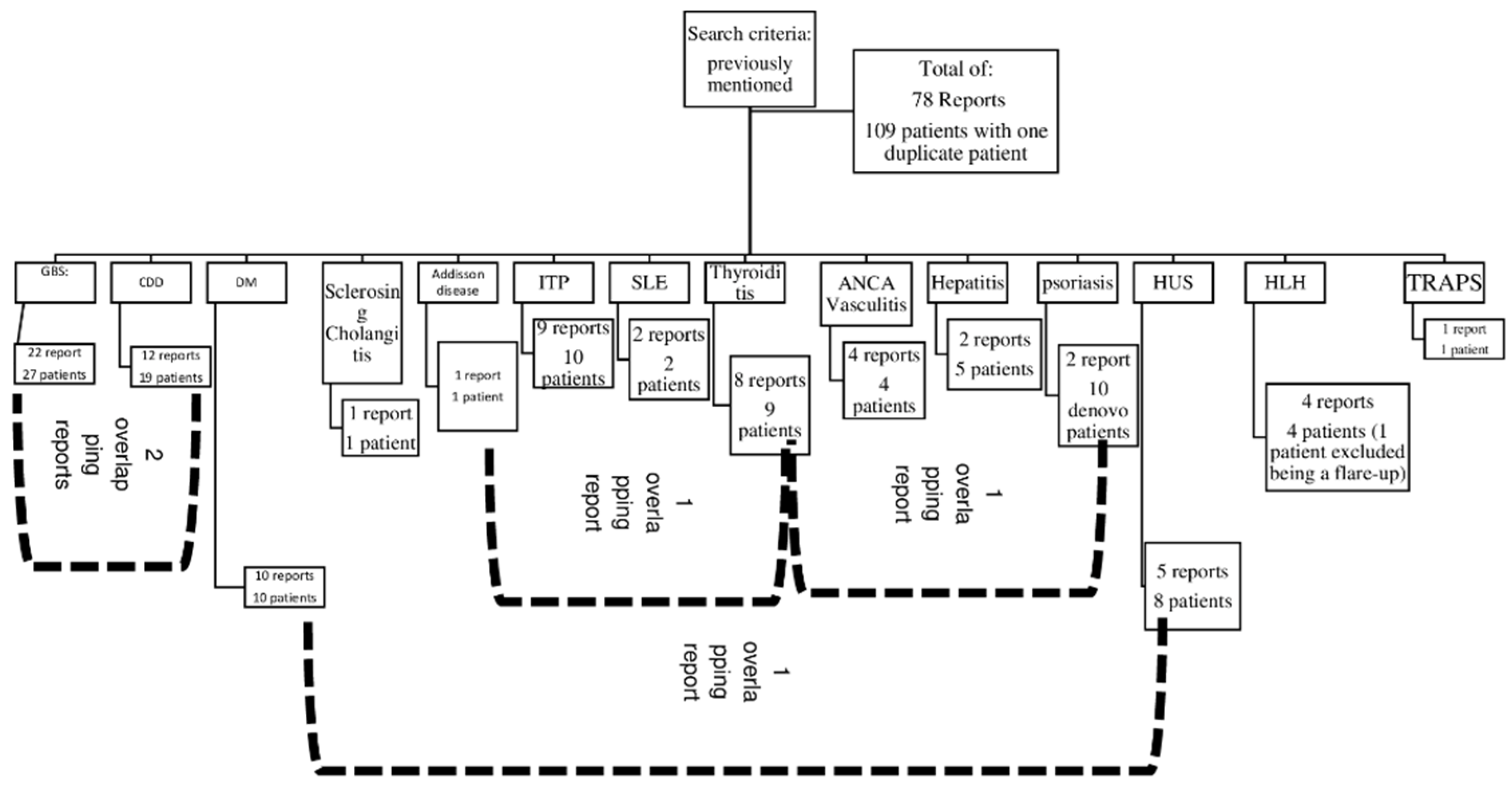

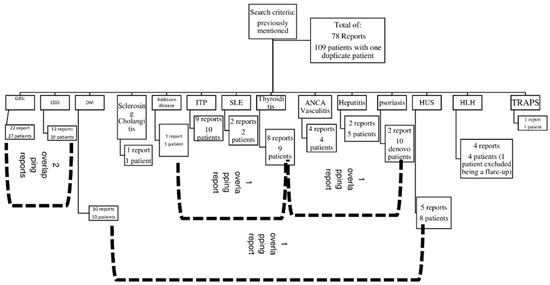

Figure 2 is a detailed algorithm for the distribution and overlap of reports and the number of patients per diagnosis.

Figure 2.

A detailed number of case series and reports per diagnosis. Abbreviations: CDD: central demyelinating disorder, GBS: Guillain–Barré syndrome, DM: Type 1 diabetes mellitus, HLH: haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, HUS: haemolytic–uremic syndrome, SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus, TRAPS: tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome.

Both of them, indicate that we included a total of 78 reports, comprising 109 patients.

4.1. Overall Results

The sex distribution in retrieved cases was equal between the two genders. Regarding age, the commonest two age intervals involved were school-aged children and adolescents, with each accounting for 38% of the overall cases. Hospital admission during COVID-19 did not seem to be a good predictor of subsequent autoimmune sequelae as there was no statistically significant difference between the number of cases with hospital admission and those who were not admitted, i.e., 49 and 60, respectively. Finally, yet importantly, most of the observed PIS were observed within 14 days of the COVID-19 infection, accounting for 61% of the total cases. (Table 1 and Table 2) illustrate the details of the overall results described in this paragraph.

Table 1.

Age, sex distribution, hospital admission, and interval to immune sequelae of patients with postacute COVID-19 sequelae.

Table 2.

Addison’s disease as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

Figure 3 is a receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) demonstrating the sensitivity of age categories in predicting hospitalization in the context of non-MIS-C sequelae of COVID-19. It clearly shows that younger age groups, categories 1 and 2 (infants [0–2 years]) and preschool [3–5 years]), were more likely to require hospitalization, with a sensitivity of 69%.

Figure 3.

ROC curve for the diagnostic accuracy of age groups in predicting hospitalization during postacute sequelae of COVID-19.

4.2. Individual Results (by Alphabetical Order of the Respective Autoimmune Disorder)

4.2.1. Addison’s Disease (Table 2)

The relationship between COVID-19 and Addison’s disease has been reported in the literature. One case of a 14-year-old female was associated with primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison) as part of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 2, which required intensive care unit (ICU) admission, as mentioned by Floras et al.

SARS-CoV-2 releases amino acid sequences similar to ACTH, which should rather cause secondary adrenal insufficiency; however, the presence of anti-21-hydroxylase antibodies was not documented, as in other infectious causes of Addison’s disease [15].

4.2.2. Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody (Table 3)

Acute ANCA-associated vasculitis is a rare but documented condition following SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults and is even rarer in the paediatric population. Here we present to you four case reports of paediatric ANCA-associated vasculitis following an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. The male-to-female ratio in the reported cases was 1:1, and the mean age among the four patients was approximately 16 years old. All of the patients (100%) acquired acute ANCA-associated vasculitis as an immediate sequela (within 0–4 weeks after COVID-19 infection), and none had delayed nor persistent sequelae. Two patients developed perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (P-ANCA) vasculitis, as seen in Firenzen et al. and Weston et al., while the other two patients developed cytoplasmic anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (C-ANCA) vasculitis. Two of the patients had pre-existing asthma, as seen in Firenzen et al. and Bryant et al. The general prognosis for post-COVID ANCA vasculitis in the previous patients was good with mild to moderate COVID-19 courses. However, the patient reported by Weston et al. was admitted to ICU due to a worsening respiratory status. All patients recovered and were discharged after proper treatment.

Molecular mimicry is not the first suggested mechanism for ANCA disorders after COVID-19; T-lymphocyte activation with the subsequent uncontrolled secretion of beta-interferon is regarded as the principal theory underlying ANCA disorders following COVID-19 [16].

Table 3.

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody vasculitis as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

Table 3.

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody vasculitis as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

| Ref. | Age (Years) | Sex | Interval between COVID-19 Infection and Autoimmune Disorder | Course of COVID-19 Infection and Hospitalization Data | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [17] | 17 | Male | 7 days | Presented with fever, drenching night sweats, cough, nasal congestion, haemoptysis, and chest tightness. | Recovered |

|

| [18] | 16 | Female | 7 days | Mild upper respiratory symptoms with anosmia. | Recovered |

|

| [19] | 17 | Male | 60 days |

| Recovered after treatment and resolution of AKI and diffuse alveolar haemorrhage (DAH). |

|

| [20] | 12 | Female | 14 to 28 days | Asymptomatic |

|

|

Abbreviations: SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; ANCA antibodies: anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; C-ANCA antibodies: cytoplasmic anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; P-ANCA antibodies: perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; PR3 antibodies: anti-protease 3 antibodies; ANA antibodies: anti-nuclear antibodies; MPO antibodies: myeloperoxidase antibodies; CT: computed tomography; HFNC: high-flow nasal cannula; LPM: litres per minute; FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; AKI: acute kidney injury; BUN/Cr: blood urea nitrogen/creatinine; HB/Hct: haemoglobin/haematocrit; FFB: flexible fibreoptic bronchoscopy; and BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage.

4.2.3. Central Demyelinating Disorders (Table 4)

Concerning the data gathered on post-COVID-19 patients suffering from demyelinating disorders other than Gullain–Barré Syndrome (GBS), we noticed an almost equal ratio of males and females (8 males to 11 females) in the reported cases. The youngest case reported was of a 3-year-old and the oldest was 16 years old. The average age was found to be 11 years.

The course of the preceding COVID infection was mostly mild. Five cases were asymptomatic, and the most reported symptom was fever. The time frame between infection and the neurological presentation ranged from a week to months, with three cases presenting with neurological manifestation during the course of COVID-19 infection.

Of the 19 reported cases, 7 cases were diagnosed as new-onset acute disseminated encephalomyelitis* (ADEM), 1 case was diagnosed as anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate (anti-NMDA)-receptor encephalitis and one case was that of unspecified encephalitis.

Two cases of optic neuritis were reported, as well as two cases of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Three of the reported cases were of post-COVID multiple sclerosis and one case exhibited an anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (anti-MOG) demyelinating disorder. One case developed longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis (LETM).

A complete recovery was observed in five cases; meanwhile, the rest of the cases suffered from mild remnants, including increased blind spot, persistent gait, residual diffuse weakness, and unilateral papilledema. Furthermore, one patient experienced relapse post-treatment and was placed on rituximab.

It is suggested that direct CNS infection by SARS-CoV-2 through the olfactory pathway weakens the blood–brain barrier via gliosis, the latter mechanism combined with a dysregulated immune response and a cytokine storm can explain the resulting CNS damage seen with COVID-19 [21].

Table 4.

Central demyelinating disorders as postacute sequelae of COVID-19.

Table 4.

Central demyelinating disorders as postacute sequelae of COVID-19.

| Ref. | Age (Years) | Sex | Interval between Infection and Autoimmune Disorder | Course of COVID-19 Infection and Hospitalization Data | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [22] | 8 | Male | One month | Mild respiratory symptoms. | Complete recovery. |

|

| 13 | Female | 2 months | Fatigue and loss of sense of smell and taste. | Moderate improvement with residual diffuse weakness. |

| |

| 14 | Female | 5 to 6 weeks | Asymptomatic. | Unreported. |

| |

| [23] | 16 | Female | 4 months | Unreported | Patient was placed on Rituximab. Follow-up information unreported. |

|

| [24] | 14 | Male | Positive PCR | Complete strength recovery, persistent hyperreflexia in the left lower limb, right eye papilledema, and increased blind spot. |

| |

| [25] | 14 | Female | 8 weeks | No respiratory involvement | No complications |

|

| 4 | Male | 8 weeks | No respiratory involvement | No complications |

| |

| 3 | Male | 6 weeks | No respiratory involvement | No complications |

| |

| [26] | 16 | Male | At the time of presentation | Asymptomatic | Full recovery |

|

| [27] | 9 | Male | 3 days | Fever, headache, and vomiting | Tracheotomized. Discharged after 60 months of hospital stay with incomplete recovery. |

|

| 9 | Female | 5 days | Fever, vomiting, and diarrhoea | Complete recovery |

| |

| [28] | 10 | Male | During disease course | fever, headache, and myalgia | Incomplete recovery |

|

| [29] | 7 | Female | 1 week | Asymptomatic | Incomplete recovery with resolution of sensory deficits but little improvement in lower limb strength. |

|

| [30] | 12 | Female | 5 days | Skin rash, headache, and fever | Incomplete recovery |

|

| [31] | 6 | Male | 10 days | Asymptomatic | Full recovery |

|

| [32] | 5 | Female | 2 days | Mild cough and fever | Patient received IVIG, showed clinical improvement, and was discharged after two weeks of hospitalization. |

|

| [33] | 15 | Female | During the course of the disease | Fever, headache, and vomiting | Needed hospitalization.Visual acuity fully recovered after treatment. |

|

| 14 | Female | During the course of the disease | Headache, myalgia, and arthralgia | Needed hospitalization. Visual acuity fully recovered after treatment. |

| |

| 14 | Male | During the course of the disease | Asymptomatic | Rankin Score: 0 and absolute control of epilepsy. Presence of psychiatric symptoms post discharge. |

|

Abbreviations: Anti-MOG: anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein; MS: multiple sclerosis; LETM: longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis; NMSOD: neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; ADEM: acute disseminated encephalomyelitis; PICU: paediatric intensive care unit; IVIG: intravenous immune globulin; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; anti-NMDA-R: anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor encephalitis; and CSF: cerebrospinal fluid.

4.2.4. Guillain–Barré Syndrome (Table 5)

Although the number of adult COVID-19 infections diagnosed with GBS is increasing, the occurrence of cases in the paediatric population remains limited or perhaps underreported.

The research entails that reported paediatric cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection associated with GBS had an average age of 16 years. In general, the age group varied drastically, with the youngest reported case being a 2-month-old male infant 15 days after the course of COVID infection, and the oldest reported patient being a 17-year-old female with a short course of COVID infection 8 days prior to the neurological complications. We assume that the severity of the infection is not directly linked to the Guillain–Barré manifestations since seven of the reported cases were asymptomatic, and the rest of the cases demonstrated variable degrees of severity. Sixteen cases showed a mild course, and eight cases were severe and required paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) admission and mechanical ventilation.

All cases showed immediate post-COVID neurological complications ranging from 0 to 4 weeks after acquiring the infection. To elaborate, the time interval between the disease and the sequelae was around 1 week in 7 cases, 2 weeks in 10 cases, 3 weeks in 2 cases, and 1 month in 11 cases. The shortest interval reported was 2 days.

A full recovery was observed in most cases with the use of IVIG and physiotherapy. However, weakness in neck and limb muscles persisted in 8 of the cases (out of 43), regardless of therapy. One case showed complete recovery after intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) except for general hyporeflexia, diminished fine touch sensation in limbs, persistent lower limb weakness, and required home ventilation. Four cases even acquired new deficits and two patients died of respiratory muscle paralysis.

The occurrence of GBS within two weeks rather than 2–4 weeks after the infectious agent mimics the picture seen with the Zika virus. This suggests a proinflammatory state leading to direct nerve damage rather than the presence of autoantibodies [34].

Table 5.

Guillain–Barré Syndrome (GBS) as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

Table 5.

Guillain–Barré Syndrome (GBS) as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

| Ref. | Age (Years) | Sex | Interval between COVID-19 Infection and Autoimmune Disorder | Course of COVID-19 Infection and Hospitalization Data | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [35] | 3 | Female | 2 weeks | Not specified |

|

|

| [36] | 3 | Female | 1 week | Mild (Flu-like) |

|

|

| [37] | 8 | Male | During the course of COVID-19 infection | Asymptomatic |

|

|

| [38] | 13 | Female | 1 month | Fever |

|

|

| [39] | 11 | Female | Not specified | Fever |

|

|

| [40] | 7 | Male | Not specified | Asymptomatic |

|

|

| [41] | 15 | Male | During the course of COVID-19 infection | Mild (no respiratory symptoms) |

|

|

| [42] | 14 | Female | 3 weeks | Upper respiratory tract infection 3 weeks Earlier. |

|

|

| [43] | 11 | Male | 3 weeks | Vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, and headache for 3 weeks. |

|

|

| [33] | 9 | Male | Not specified | Asymptomatic |

|

|

| 14 | Male | Not specified | Fever and rhinorrhoea |

|

| |

| 12 | Female | Not specified | Not specified |

|

| |

| [44] | 16 | Female | During the course of COVID-19 infection | Mild |

|

|

| 15 | Male | 15 days | Mild (no respiratory involvement) |

|

| |

| 5 | Female | During the course of the disease | Mild (No respiratory involvement) |

|

| |

| 0.2 | Male | 15 days | Dry cough, fever, and diarrhoea. 15 days later, symptoms developed into dyspnoea and hypoxemia requiring mechanical ventilation. |

|

| |

| [45] | Adolescent (age is not specified) | Male | 2 weeks | Mild; fever |

|

|

| [46] | 4 | Female | 2 weeks | Mild; fever |

|

|

| [47] | 9 | Female | Not specified | Not specified |

|

|

| [48] | 16 | Female | During the course of COVID-19 infection | Asymptomatic |

|

|

| [49] | 9 | Male | During the course of COVID-19 infection | Asymptomatic |

|

|

| [50] | 6 | Male | 1 week | Two days of fever followed by severe respiratory muscle weakness requiring mechanical ventilation. |

|

|

| [51] | 12 | Male | 1 week | Mild and treated symptomatically at home. |

|

|

| [52] | 11 | Male | 20 days | An acute upper respiratory tract infection with low-grade fever treated at home with acetaminophen and azithromycin. Chest CT showed patchy subsegmental faint opacifications with atelectasis in the lingula. |

|

|

| [53] | 6 | Female | 1 month | Asymptomatic |

|

|

| [54] | 17 | Female | 8 days | Fever, nausea, severe vomiting, and diarrhoea. |

|

|

| [24] | 8 | Male | During the course of COVID-19 | Asymptomatic |

|

|

Abbreviations: GBS: Guillain–Barré syndrome; PICU: paediatric intensive care unit; IVIG: intravenous immune globulin; and EMG/NCS: electromyography/nerve conduction studies.

4.2.5. Hepatitis (Table 6)

Hepatic involvement has been widely described as part of the acute setting of SARS-CoV-2 infection, manifesting as a mild increase in liver enzymes without hepatic dysfunction, which eventually subsides as the clinical course of COVID-19 improves. Severe COVID-19 infection in the paediatric population can result in MIS-C and multiorgan failure including hepatic failure. With that being said, here we present five case reports of isolated hepatitis with or without hepatic failure as the main presentation of COVID-19 infection in children. The female-to-male ratio was found to be 3:2 with 150% of females being more susceptible to acquiring the reported complications. The mean age among patients was approximately 6 years old. All of the patients (100%) developed an immediate (within 0–4 months from the start of COVID-19 infection) post-COVID-19 sequelae and none suffered from delayed or persistent sequelae.

The course of COVID-19 infection was mild in three patients and moderate to severe in two infant patients, as seen in Antala et al., at the ages of 6 months and 4 months. Three of the five patients acquired complications, such as acute liver failure with resistant coagulopathy, which is seen in Osborn et al. and the two infants in Antala et al. The 4-month-old infant in Antala et al. also acquired acute kidney injury as well as seizures. Two patients developed hepatic encephalopathy, as seen in Osborn et al. and the 16-year-old male patient in Antala et al. It should be noted that four out of the five patients were admitted to the PICU with an average length of stay of approximately 5 days.

Ultimately, all patients received all of the needed treatment and were discharged accordingly.

Molecular mimicry with the activation of autoreactive T cells and the secretion of proinflammatory mediators has been proposed as a potential mechanism for the occurrence of hepatitis following COVID-19 [55].

Table 6.

Hepatitis as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

Table 6.

Hepatitis as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

| Ref. | Age (years) | Sex | Interval between COVID-19 Infection and Autoimmune Disorder | Course of COVID-19 Infection and Hospitalization Data | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [56] | 3 | Female | 21 days |

| Recovered and discharged after 18 days of hospitalization on azathioprine as steroid-sparing maintenance therapy. |

|

| [57] | 0.5 | Female | During the course of COVID-19 infection |

|

|

|

| 0.33 | Male | During the course of COVID-19 infection | Presented to ER with feeding difficulties, vomiting, hypotonia, diaphoresis, and progressive lethargy over 12 h. |

|

| |

| 16 | Female | 3 days | Presented with cough, congestion, and fever. |

|

| |

| 11 | Male | 2 days | Afebrile without other symptoms. |

| Presented with non-bloody, non-bilious emesis and abdominal pain. |

Abbreviations: Yrs: years; ER: emergency room; INR: international normalized ratio; GCS: Glasgow coma scale; PICU: paediatric intensive care unit; EEG: electroencephalography; ICU: intensive care unit; IV: intravenous; and CD3: cluster of differentiation 3.

4.2.6. Haemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (Table 7)

Four cases of de novo HLH were reported following COVID-19 infections. It was found that the age of the patients varied from neonates to school age in both diseases, with a predominance of preschool age (mean age = 3). HLH appeared equally in both males and females (1:1). Three cases presented with symptoms of HLH several weeks after COVID, but one had symptoms during the course of COVID. The severity of the preceding COVID infection ranged from unremarkable to severe, with two of the cases having required ICU admission during their COVID infection.

It is worth noting that one case presented with concomitant post-COVID viral encephalitis with cerebral atrophy, and another case was diagnosed as Chédiak–Higashi syndrome.

A triggered immune response could be the mechanism of HLH development in COVID-19 patients. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) could activate the NLR family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, a potent activator of macrophages, with a significant release of interleukin 1 beta (IL-1b) subsequently leading to the release of interleukin-6 (IL-6) [58].

Table 7.

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

Table 7.

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

| Ref. | Age (years) | Sex | Interval between Infection and Autoimmune Disorder | Course of COVID-19 Infection and Hospitalization Data | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [59] | 5 years | Female | 4.5 weeks | Presented with fever and papular rash for three days. | 8 months in remission. | Condition caused:

|

| [60] | 7 years | Male | 2 weeks | Mild attack. | Recovery after 3 days of steroid therapy. | |

| [61] | 2 years | Male | 2 weeks | The disease course showed feeding intolerance, fever (39.6 °C), diarrhoea, and vomiting for two days. | Monitored in PICU at the time of publishing. |

|

| [62] | 6 weeks | female | During the course | Fever of up to 40 °C and poor feeding. | Recovery. |

|

Abbreviations: Yrs: years; HUS: haemolytic–uremic syndrome; HLH: haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; and TRAP: TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome.

4.2.7. Haemolytic–Uremic Syndrome (Table 8)

Eight cases were documented with HUS following COVID-19 in the paediatric age groups. The mean age of the patients was 7 years. All HUS cases were males, with only one case report of COVID related to HUS in a female. Only two cases required ICU admission during the course of the preceding COVID.

It is worth noting that all HUS cases were atypical HUS, except for one case of concomitant COVID-19 and Shiga-toxin-associated HUS. In all cases, treatment was given with zero mortality.

Direct endothelial damage by SARS-CoV-2 may be the trigger for the activation of complementary and subsequent HUS in COVID-19 cases [63].

Table 8.

Haemolytic–uremic syndrome as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

Table 8.

Haemolytic–uremic syndrome as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

| Ref. | Age | Sex | Interval between Infection and HUS | Course of COVID-19 Infection and Hospitalization Data | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [64] | 4 months | Male | 4 weeks | Fever and mild respiratory symptoms. |

|

|

| 4.5 months | Male | During the course of COVID-19 infection | Presented with pyrexia, diarrhoea, and reduced drinking. |

| ||

| [65] | 16 months | Male | During the course of COVID-19 infection | Fever, emesis, and respiratory distress. |

|

|

| [66] | 3 years | Male | During the course of COVID-19 infection | The patient presented with fever, coryza, cough, decreased urine output lasting for 3 days, and a history of non-bloody diarrhoea 1 week prior to admission. |

| |

| [67] 3 patients were excluded as they are flare-ups of pre-existing conditions | 10 years | Female | 10 | Fever without respiratory manifestations. |

| |

| 4 years | Male | 21 |

| |||

| [68] | 6 years | Male | During the course of the disease |

| ||

| 10 years | Male | During the course of the disease | Bloody diarrhoea, oliguria, and thrombocytopenia. |

Abbreviations: Yrs: years; HUS: haemolytic–uremic syndrome; DKA: diabetic ketoacidosis; and CKD: chronic kidney disease.

4.2.8. Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura (Table 9)

The literature investigated 10 paediatric case reports discussing post-COVID-19 ITP. It was found that ITP in children can be triggered by various viruses, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B, hepatitis C, cytomegalovirus (CMV), varicella zoster virus (VZV), and, recently, SARS-CoV-2. Despite ITP being more common in males, the female-to-male ratio among the cases collected from the literature is 3:2. The mean age was 8 years. Results found that only three patients developed ITP during the course of COVID, while the remaining seven developed symptoms an average of 3.7 weeks after being infected with COVID-19. Seven out of ten cases had a mild course of COVID-19 infection prior to ITP, while only one case required ICU admission for 14 days after the infection progressed to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

All patients recovered successfully after receiving the proper steroid and IVIG treatment.

Several mechanisms have been postulated to induce thrombocytopenia in the context of COVID-19, but not all of them are mediated by autoantibodies. Viral infection and inflammation result in lung damage. Damaged lung tissues and pulmonary endothelial cells may activate platelets in the lungs, resulting in aggregation and the formation of microthrombi, which increases platelet consumption. Most patients with COVID-19 who have thrombocytopenia have elevated D-dimer levels and impaired coagulation time, which further proves the above hypothesis that there is low intravascular coagulation [69].

Table 9.

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) as postacute sequela of COVID-19.

Table 9.

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) as postacute sequela of COVID-19.

| Ref. | Age (Yrs) | Sex | Interval between Infection and Autoimmune Disorder | Course of COVID-19 Infection and Hospitalization Data | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [70] | 0.75 | Male | During the course of COVID-19 infection | Yes | Recovery after megadose methylprednisolone. | |

| [71] | 8 | Female | During the course of COVID-19 infection | Yes | Recovery after IV methylprednisolone, platelet concentrate, and two doses of IVIG. |

|

| [72] | 5.5 | Female | 22 days | Yes | Hospitalized for 4 weeks. Recovery after prednisolone (tapering dose) and eltrombopag. |

|

| [73] | 11 | Male | 4 weeks | Yes | Recovery after 2 doses of IVIG. |

|

| [74] | 15 | Male | 5 weeks | No | Recovered after IVIG. |

|

| 3 | Female | 3 weeks | No | Recovered after IVIG. |

| |

| [75] (One patient excluded only AIHA) | 16 | Male | 3–4 weeks | No | Recovery after corticosteroid therapy. |

|

| [76] | 1.5 | Female | 5 weeks | No | Recovery after a single dose of IVIG. |

|

| [77] | 10 | Female | 3 weeks | No | Clinical improvement after acetaminophen, diphenhydramine, and IVIG. |

|

| [78] | 12 | Female | During the course of COVID-19 infection | Yes | Recovery after IVIG and corticosteroids. ARDS improved with tocilizumab and remdesivir. |

|

Abbreviations: Yrs: years; ITP: immune thrombocytopenic purpura; COVID: coronavirus disease; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; IV: intravenous; IVIG: intravenous immunoglobulin; ALL: acute lymphocytic leukaemia. AIHA: acute haemolytic anaemia; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; and ICU: intensive care unit.

4.2.9. Psoriasis (Table 10)

Most of the published cases in the literature reported exacerbations of pre-existing psoriasis following an attack of COVID. However, two papers reported de novo cases. The first reported nine cases of de novo appearance, consisting of six males and three females. The mean age was 10 years.

Eight of the nine cases had a mild course of the preceding COVID infection, and only one patient needed hospital admission. The patients developed various variants of psoriasis, with guttate psoriasis being the most common. Six of the patients had a previous family history of psoriasis. The second paper reported a 13-year-old male with a previously mild course of COVID-19 infection that developed psoriasis vulgaris, which responded fully to topical steroids.

Psoriasis is a sustained inflammation led by a T-cell-driven autoimmune response with elevated levels of interleukin (IL)-23, IL-17, and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a). Psoriasis has also been associated with higher levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme type 2 (ACE2) than the general population. COVID-19 spike protein has been noted to have a high affinity for ACE2 receptors. This could be a possible causal mechanism of reactivity in the association between psoriasis and COVID-19 infection and vaccination [79].

Table 10.

Psoriasis as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

Table 10.

Psoriasis as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

| Ref. | Age | Sex | Interval between Infection and Autoimmune Disorder | Course of COVID-19 Infection and Hospitalization Data | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [80] | 2.5 yrs | Male | Mean interval of 28 days | Only one of the nine patients needed hospital admission. | Unreported. |

|

| 15 yrs | Male | |||||

| 9 yrs | Male | |||||

| 9 yrs | Female | |||||

| 7 yrs | Male | |||||

| 16 yrs | Female | |||||

| 8 yrs | Male | |||||

| 10 yrs | Male | |||||

| 16 yrs | Female | |||||

| [81] | 13 yrs | Male | 8 weeks | No | Full recovery after receiving topical steroids. |

|

Abbreviations: Yrs: years.

4.2.10. Sclerosing Cholangitis (Table 11)

Only one case of post-COVID development of autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis (AISC) had been reported in the paediatric age groups at the time of data collection. It manifested as a delayed post-COVID autoimmune sequelae 2 months after the setting of a SARS-CoV-2 infection in a 14-year-old male patient. The presence of advanced fibrosis observed in the patient’s liver biopsy suggests that the autoimmune process may have started before COVID-19, and the infection itself accelerated the progression of the disease. However, the lack of other reported cases makes this theory hard to prove.

The patient had a mild course of the preceding COVID-19 infection. All symptoms of AISC subsided after receiving a two-month course of prednisone as well as azathioprine.

Cholangiopathy following COVID-19 might not only be the result of autoinflammation or autoimmune; a possible confounder is a hypoxic injury. Hypoxia leads to biliary necrosis, and previous reports of influenza cases have demonstrated sclerosing cholangitis as a result of severe hypoxia [82].

Table 11.

Autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

Table 11.

Autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

| Ref. | Age | Sex | Interval between Infection and Autoimmune Disorder | Course of COVID-19 Infection and Hospitalization Data | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [83] | 14 yrs | Male | 8 weeks | Yes |

|

|

Abbreviations: ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase; UDCA: ursodeoxycholic acid; and AIH/PSC: autoimmune hepatitis/primary sclerosing cholangitis.

4.2.11. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (Table 12)

As for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) triggered by COVID-19, two cases were reported at the time of this paper. Both cases were female patients. The first case was a 13-year-old patient who was hospitalized after developing severe pneumonia during the course of COVID-19 infection. The interval between COVID-19 infection and the development of SLE was 2 months. The patient required plasma exchange to show improvement.

The second patient was an 18-year-old female who had a simultaneous onset of SLE with COVID-19 infection. She was hospitalized and needed mechanical ventilation. She also developed severe attacks of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) with positive antiphospholipid antibodies and lupus anticoagulant, and, unfortunately, went into cardiac arrest after developing cardiac tamponade and could not be resuscitated.

Genome-wide association studies show that there is a genetic component shared between SLE and COVID-19. The locus with the most evidence of shared association is TYK2, a gene critical to the type I interferon pathway, where the local genetic correlation is negative. Another shared locus is CLEC1A [84].

Table 12.

Systemic lupus erythematosus as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

Table 12.

Systemic lupus erythematosus as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

| Ref. | Age | Sex | Interval between Infection and Autoimmune Disorder | Course of COVID-19 Infection and Hospitalization Data | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [85] | 13 yrs | Female | 2 months | Yes | Improvement only after receiving six sessions of plasma exchange. |

|

| [86] | 18 yrs | Female | During COVID | Yes | Death. |

|

Abbreviations: yrs: years; and DVT: deep venous thrombosis.

4.2.12. Thyroiditis (Table 13)

Much like other endocrine post-COVID-19 sequelae, paediatric thyroid complications are not uncommon. Some would even hypothesize that COVID-19 is an endocrine disorder given the number of sites it affects besides the respiratory system. Many papers have attributed this to the fact that the COVID-19 virus utilizes an entry receptor, the ACE-2 receptor. The ACE-2 receptor is expressed in many endocrine tissues, one of which is the thyroid follicular cell, rendering it more susceptible to the relentless virus.

Table 13 contains the relevant papers found against our search criteria, describing the most prominent paediatric thyroid complications among the post-intensive care syndrome (PICS), age, sex, course of the COVID-19 infection, and whether or not it was a de novo complication. Accordingly, the female-to-male ratio was found to be 5:4, with the female sex being the most predominant and the mean age being approximately 14 years.

While four patients acquired an immediate post-COVID-19 sequelae ranging between 2–4 weeks after COVID-19 infection and five other patients acquired delayed post-COVID19 sequelae ranging between 4 weeks up to 6 months, no patients were reported with persistent paediatric post-COVID19 thyroid complications lasting for more than 6 months.

Seven out of nine of the patients were previously healthy, while two out of the nine had pre-existing hyperthyroid states at the time of COVID-19 infection. Seven out of nine patients had a rather mild self-limiting course of COVID-19, while two required ICU admission, as seen in Victoria et al. However, all patients recovered and were discharged eventually after adequate treatment.

Three of the nine patients were found to have acquired autoimmune hypothyroidism, one case of which was associated with primary adrenal insufficiency as part of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 2 in Flokas et al. (mentioned in Addison’s Table). Two patients developed a thyrotoxic storm on top of a pre-existing state of hyperthyroidism, while two others developed de novo Grave’s disease, one of which was also associated with a thyrotoxic storm, as seen in Qureshi et al. and Rocket et al.

Unlike thyroid complications in adults, subacute thyroiditis was much less commonly reported, with one case in Brancatella et al. Lastly, a post-COVID-19 thyroid abscess was reported by Maithani et al., despite the absence of any relevant congenital anomalies.

Table 13.

Thyroiditis as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

Table 13.

Thyroiditis as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

| Ref. | Age | Sex | Interval between COVID-19 Infection and Disorder | Course of COVID-19 Infection and Hospitalization Data | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [81] | 13 | Male | 56 days | Mild course with low-grade fever, congestion, cough, and body aches that resolved in a few days. |

|

|

| [87] | 16 | Male | 56 days | Presented with a diminished sense of smell, cough, chills, nausea, and fatigue. | Patients improved after methimazole and propranolol. |

|

| [88] | 16 | Female | 3 days |

|

|

|

| [89] | 16 | Male | During the course of the disease |

|

|

|

| [14] | 14 | Female | 21 days |

|

|

|

| [90] | 14 | Female and male twins | 56 days |

|

|

|

| [91] | 18 | Female | 14 days |

|

|

|

| [92] | 3 | Female | 42 days |

|

|

|

Abbreviations: Hb: haemoglobin; APS2: autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 2; TSH: thyroid-stimulating hormone; TPO: thyroid peroxidase; TSI: thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins; Tg: thyroglobulin; FT3: free triiodothyronine; FT4: free thyroxine; URI: upper respiratory infection; ICU: intensive care unit; and APS 2: autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 2.

4.2.13. Tumour Necrosis Factor Receptor-Associated Periodic Syndrome (Table 14)

Regarding TRAPS, only a single case report of post-COVID TRAPS was found in a 6-year-old female of delayed onset, 4 months after a COVID infection of unspecified severity.

The patient suffered from three attacks of macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) as a presentation of TRAPS for which she was hospitalized and treated.

She recovered after being admitted to the PICU for 22 days and received methylprednisolone and anakinra.

Table 14.

Tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

Table 14.

Tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

| Ref. | Age (Yrs) | Sex | Interval between Infection and Autoimmune Disorder | Course of COVID-19 Infection and Hospitalization Data | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [93] | 6 | Female | 4 months | Asymptomatic |

|

|

Abbreviations: Yrs: years; TRAPS: tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome; and MAS: macrophage activation syndrome.

4.2.14. Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (Table 15)

Similarly, SARS-CoV-2 has proven to manifest itself through catalyzing diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and unmasking autoimmune type 1 diabetes mellitus, particularly in children. The mechanism for that is hypothesized to be similar to that of thyroid-related sequelae: through ACE-2 receptors found in the endocrine part of the pancreas. Furthermore, a recent study by Govender et al. reported that COVID-19 can precipitate insulin resistance in some patients causing chronic metabolic disorders that would not have existed otherwise. All in all, the exact relationship between SARS-CoV-2 and type 1 diabetes mellitus remains uncertain and requires further research.

According to the 10 case reports collected, we have concluded a male predominance with a male: female ratio of 7:3, where females are 43% less likely to acquire post-COVID-19 type 1 diabetes mellitus. The mean age for said complication is approximately 9 years old. Moreover, 100% of the patients developed de novo type 1 diabetes mellitus with none having a pre-existing disease.

In nine patients out of ten, post-COVID-19 type 1 diabetes mellitus was immediate (manifesting anytime between the start of COVID-19 infection and 4 weeks after) with only one case being delayed, as reported by Naguib et al. (manifesting 1–6 months after the start of COVID-19 infection), and none reporting persistent (lasting more than 6 months) post-COVID19 complications. Only one patient exhibited mild COVID-19 symptoms, as seen in Lanca et al., while the rest of the patients exhibited high severity.

Eight patients were admitted to the PICU with a median length of stay of approximately 3 days. However, seven of them were eventually discharged after clinical improvement.

Out of the 10 patients, one death was reported in Brothers et al. due to multisystem failure, metabolic acidosis, and fungal urosepsis from Candida glabrata resistance to azoles, despite DKA resolution.

Table 15.

Type 1 diabetes mellitus as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

Table 15.

Type 1 diabetes mellitus as a postacute sequela of COVID-19.

| Ref. | Age (Years) | Sex | Interval between Infection and Autoimmune Disorder | Course of COVID-19 Infection and Hospitalization Data | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [94] | 10 | Male | 0 | Presented with respiratory distress and drowsiness. |

|

|

| [95] | 13 | Male | During the course of COVID | Afebrile, tachycardic, tachypneic. |

|

|

| 8 | Male | During the course of COVID-19 infection | Afebrile and mildly dehydrated. |

|

| |

| [96] | 12 | Female | 4 days | Presented with rhinorrhea progressing to dry cough, post-tussive non-bilious emesis, shortness of breath, mottled skin, and altered mental status. |

|

|

| [97] | 7 | Male | During the course of COVID-19 infection | Asymptomatic |

|

|

| [98] | 3 | Male | During the course of COVID-19 infection |

|

|

|

| [99] | 16 | Male | During the course of COVID-19 infection. | Mild dyspnoea and productive cough. |

|

|

| [100] | 0.7 | Male | During the course of COVID-19 infection | Tachycardia, tachypnoea, and fever. |

|

|

| [101] | 8 | Female | 8 weeks | Cough, rhinorrhoea, anorexia, and weight loss. |

|

|

| [102] | 15 | Female | During the course of COVID-19 infection | Fever, abdominal pain, and vomiting. |

|

|

| [65] | 16 months | Male | During the course of COVID-19 infection | Fever, emesis, and respiratory distress. |

|

|

Abbreviations: SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; ICU: intensive care unit; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; DM: diabetes mellitus; PICU: paediatric intensive care unit; DKA: diabetic ketoacidosis; and aHUS: atypical haemolytic–uremic syndrome.

5. Discussion

Throughout this systematic review of all non-MIS-C postinfectious immune sequelae of COVID-19, the two key findings uncovered were the rapid development of those immune sequelae in less than 14 days from the onset of COVID-19 and the high prevalence of these complications in children older than 6 years old.

It also seems that no age is spared—postacute sequelae have affected the whole spectrum from infancy to adolescence.

The interval between infectious disease and its postacute sequelae is important as it might be suggestive of the underlying mechanism.

Different pathogeneses underlie different types of similar postinfectious disorders, and mechanisms can be predictable from the time interval until the development of such sequelae. For instance, reactive arthritis is known to develop immediately following the related infection, and despite the incomplete understanding of the pathogenesis of reactive arthritis, it is hypothesized that T lymphocytes are induced by bacterial fragments such as lipopolysaccharide and nucleic acids when invasive bacteria reach the systemic circulation. These activated cytotoxic T cells then attack the synovium. It is still unclear whether reactive arthritis involves the production of autoantibodies or not, but the rapid development of this postinfectious complication within days of the initial infection suggests a T-cell-mediated autoinflammatory process rather than a classic autoimmune disorder [103,104].

Another extreme example of postinfectious sequelae is the celiac disease process, which is rarely observed after a rotavirus infection. It differs from reactive arthritis in being a delayed postacute sequelae, which necessitates weeks, up to months, to develop after infection. Surprisingly, it shares similarities to reactive arthritis, a T-cell-mediated mechanism with hypercytokinemia. This occurs because rotaviruses disrupt intestinal immune homeostasis, eventually facilitating T-cell-mediated immunity against dietary antigens. Type I interferon (IFN) and interferon regulatory factor 1 signalling play a central role by blocking regulatory T-cell conversion and promoting helper T-cell immunity.

Rheumatic fever is another classic example of postinfectious sequelae. Rheumatic fever develops within a 2–4 weeks interval after the initial infection. Autoantibodies to myosin, tropomyosin, and collagens have been identified [105].

According to our study, in the case of post-COVID-19 infections, 61% of the PIS occurred within 14 days of the infections, with many occurring during the course of the disease. This rapid onset of PIS to SARS-CoV-2 suggests a rather similar autoinflammatory process to the postinfectious diseases previously mentioned, notably reactive arthritis, with dysregulated immunity leading to widespread activation of T cells and hypercytokinemia.

In COVID-19, next-generation sequencing has revealed activated CD8+, T-helper type 1, Th17, natural killer (NK), and natural killer T (NKT) cells together with other innate immune cells that secrete additional cytokines to target virus-infected cells, and their overstimulation, together with effector innate immune cells, may lead to tissue damage [106].

Moreover, CD8+ T cells expressing high levels of PD-1, CTLA-4, TIGIT, granzyme B, and perforin were increased in the severe group compared with the mild group. This data suggests that SARS-CoV-2 infection may lead to functional impairment in CD4+ T cells and uphold excessive activation of CD8+ T cells [106].

Another interesting finding in our study was the high prevalence of postinfectious sequelae in children and adolescents older than six years. This is thought to be due to a distinct group of lymphocytes known as regulatory T cells (Tregs), which are key inflammatory response regulators and play a pivotal role in immune tolerance and homeostasis. Treg-mediated robust immunosuppression provides self-tolerance and protection against autoimmune diseases. However, once this system fails to operate or poorly operates, it leads to an extreme situation where the immune system reacts against self-antigens and destroys host organs and, consequently, causes autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases. There is established evidence that Tregs decline with age. An interesting study focused on T-cell differentiation from infancy to childhood, and it was noted that the proinflammatory Th17 cell increases after the age of three years of age. Moreover, the functionality of CD4 cells increased with age; secretion of IL-17 and TNF was positively correlated with increasing age after the age of three years. These findings might explain why postacute sequelae were more prominent after the age of six years [107,108].

6. Limitations

The biggest challenge and limitation we faced in the construction of this systematic review was the diversity of outcome parameters in the collected reports. The available reports did not always include the same information about the discussed patients. This led to a significant limitation in the retrieved outcome parameters.

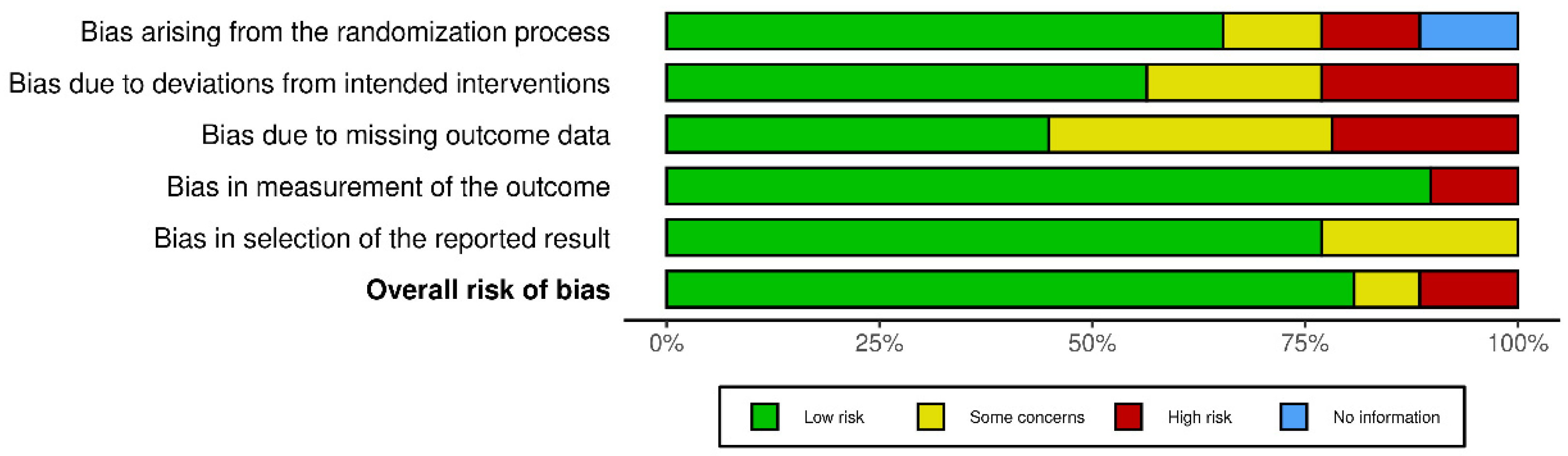

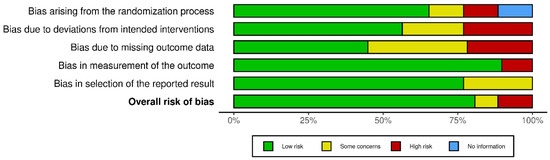

Any risk of bias has been illustrated in Figure 4 [109].

Figure 4.

Risk-of-bias assessment.

A PRISMA chart has been designed using the updated guidelines for reporting for systematic reviews [110].

7. Conclusions and Clinical Implications

This is the largest systematic review to date of all non-MIS-C post-infectious immune sequelae (PIS) of COVID-19. The results suggest that PIS commonly occur immediately (within 14 days) after infection with COVID-19, which prompts the conclusion of an autoinflammatory process rather than a classic autoimmune pathology. On that account, more evidence is needed to focus on the underlying mechanisms, as this can contribute to enhancing the management of patients by giving a variety of immune modulators immediately after COVID-19 infection. In addition, equal care should be given to hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients after infection because the severity of COVID-19 did not prove to be a predictor of the occurrence of post-infectious immune sequelae. Close attention should be given to patients above 6 years of age as our data suggest a high predilection for complications in this age group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F.A., N.G., M.H.H. and Y.O.; methodology, N.D., R.H., A.D., A.M. (Aalaa Mady), A.Y., A.R.A., A.M. (Aya Mohyeldin), A.S.S., A.A., E.A., F.E., H.A., K.M., L.F., M.H., M.A.R., M.A., R.A., R.S. and S.E.; software, A.F.A., S.K. and N.D.; formal analysis, A.F.A., M.H.H., M.E., S.K., N.D., R.H., A.D., A.M. (Aalaa Mady), A.Y., A.R.A., A.M. (Aya Mohyeldin), A.S.S., A.A., E.A., F.E., H.A., K.M., L.F., M.H., M.A.R., M.A., R.A., R.S., S.E., S.E.A., N.G. and Y.O.; investigation, A.F.A., M.H.H., M.E., S.K., N.D., R.H., A.D., A.M. (Aalaa Mady), A.Y., A.R.A., A.M. (Aya Mohyeldin), A.S.S., A.M. (Aya Mohyeldin), E.A., F.E., H.A., K.M., L.F., M.H., M.A.R., M.A., R.A., R.S., S.E., S.E.A., N.G. and Y.O.; resources, A.F.A., M.H.H., M.E., S.K., N.D., R.H., A.D., A.M. (Aalaa Mady), A.Y., A.R.A., A.M. (Aya Mohyeldin), A.S.S., A.A., E.A., F.E., H.A., K.M., L.F., M.H., M.A.R., M.A., R.A., R.S., S.E., S.E.A., N.G. and Y.O.; data curation, A.F.A., M.H.H., M.E., S.K., N.D., R.H., A.D., A.M. (Aalaa Mady), A.Y., A.R.A., A.M. (Aya Mohyeldin), A.S.S., A.A., E.A., F.E., H.A., K.M., L.F., M.H., M.A.R., M.A., R.A., R.S., S.E., S.E.A., N.G. and Y.O.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F.A., M.H.H., M.E., S.K., N.D., R.H., A.D., A.M. (Aalaa Mady), A.Y., A.R.A., A.M. (Aya Mohyeldin), A.S.S., A.A., E.A., F.E., H.A., K.M., L.F., M.H., M.A.R., M.A., R.A., R.S., S.E., S.E.A., N.G. and Y.O.; writing—review and editing, A.F.A., M.H.H., M.E., S.K., N.D., R.H., A.D., A.M. (Aalaa Mady), A.Y., A.R.A., A.M. (Aya Mohyeldin), A.S.S., A.A., E.A., F.E., H.A., K.M., L.F., M.H., M.A.R., M.A., R.A., R.S., S.E., S.E.A., N.G. and Y.O.; visualization, N.D., R.H., A.D., A.M. (Aalaa Mady), A.Y., A.R.A., A.M. (Aya Mohyeldin), A.S.S., A.A., E.A., F.E., H.A., K.M., L.F., M.H., M.A.R., M.A., R.A., R.S. and S.E.; supervision, A.F.A., N.G., M.H.H. and Y.O.; project administration, A.F.A., N.G., M.H.H. and Y.O.; funding acquisition, (none). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable as this study is a systematic review of reported cases.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable as this study is a systematic review of reported cases.

Data Availability Statement

Data is made available upon request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

As a first author, I wanted to thank the students, interns and residents who are co-authoring this work with me. I wanted also to thank everyone who is struggling to be him or herself, to succeed without support; one day, you will realize the worth of this struggle.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

List of Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| A-ANCA | acute anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody |

| ACE-2 | angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 |

| ACTH | adrenocorticotropic hormone |

| ADEM | acute disseminated encephalomyelitis |

| AHA | acute haemolytic anaemia |

| AIH | autoimmune hepatitis |

| AIHA | autoimmune haemolytic anaemia |

| AKI | acute kidney injury |

| ALL | acute lymphocytic leukaemia |

| ALT | alanine aminotransferase |

| ANA antibodies | anti-nuclear antibodies |

| ANCA | anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody |

| Anti-MOG | anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein |

| Anti-NMDA-R | anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA)-receptor encephalitis |

| APS2 | autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 2 |

| ARDS | acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| AST | aspartate aminotransferase |

| BAL | bronchoalveolar lavage |

| BUN | blood urea nitrogen |

| C-ANCA | cytoplasmic anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody |

| CD | celiac disease |

| CD4+ | cluster of differentiation 4 (a co-receptor for t-helper receptor) |

| CD8+ | cluster of differentiation 8 |

| CDD | central demyelinating disorders |

| CMV | cytomegalovirus |

| COVID | coronavirus disease |

| COVID 19: | coronavirus disease of 2019 |

| Cr | creatinine |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| CT | computed tomography |

| CTLA-4 | cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 |

| DAMPs | damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DKA | diabetic ketoacidosis |

| DVT | deep venous thrombosis |

| EEG | electroencephalography |

| ER | emergency room |

| FFB | flexible fibreoptic bronchoscopy |

| FiO2 | fraction of inspired oxygen |

| FT3 | free triiodothyronine |

| FT4 | free thyroxine |

| GBS | Guillain–Barré syndrome |

| GCS | Glasgow Coma Scale |

| GGT | bamma-glutamyl transferase |

| Hb | haemoglobin |

| Hct | haematocrit |

| HFNC | high-flow nasal cannula |

| HIV | human immunodeficiency virus |

| HLH | haemophagocytic lymphocytic histiocytosis |

| HUS | haemolytic–uremic syndrome |

| ICU | intensive care unit |

| IFN | interferon |

| INR | international normalized ratio |

| ITP | idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura |

| ITP | immune thrombocytopenic purpura |

| IV | intravenous |

| IVIG | intravenous immune globulin |

| LETM | longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis |

| MAS | macrophage activation syndrome |

| MERS-CoV | Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus |

| MIS-C | multi-inflammatory syndrome of children |

| MPO antibodies | myeloperoxidase antibodies |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| MS | multiple sclerosis |

| NK | natural killer cell |

| NKT | natural killer T cell |

| NMSOD | neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder |

| PAIS | postacute infection sequelae |

| P-ANCA | perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody |

| PAS | postacute sequelae |

| PASC | postacute sequelae of COVID-19 |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| PD-1 | programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PICS | post-intensive care syndrome |

| PICU | paediatric intensive care unit |

| PIS | post-infectious sequelae |

| PR3 antibodies | anti-protease 3 antibodies |

| PSC | primary sclerosing cholangitis |

| SARS-CoV-2 | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| SLE | systemic lupus erythematosus |

| T1DM | type 1 diabetes mellitus |

| Tg | thyroglobulin |

| Th1 | T-helper type 1 |

| Th17 | T-helper type 17 |

| TIGIT | T-cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains |

| TPO | thyroid peroxidase |

| TRAPS | tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome |

| Tregs | regulatory T cells |

| TSH | thyroid-stimulating hormone |

| TSI | thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins |

| UDCA | ursodeoxycholic acid |

| URI | upper respiratory infection |

| VZV | varicella zoster virus |

| Yrs | years |

References

- Bozzola, E.; Spina, G.; Valeriani, M.; Papetti, L.; Ursitti, F.; Agostiniani, R.; Mascolo, C.; Ruggiero, M.; Di Camillo, C.; Quondamcarlo, A.; et al. Management of pediatric post-infectious neurological syndromes. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.; Rogal, S.; Alam, A.; Levinthal, D.J. Rapid improvement in post-infectious gastroparesis symptoms with mirtazapine. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 6671–6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, N.; Kapoor, P.; Dhole, T.N. Antibody and inflammatory response-mediated severity of pandemic 2009 (pH1N1) influenza virus. J. Med. Virol. 2014, 86, 1034–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.-N.; Liu, L.; Qiao, H.-M.; Cheng, H.; Cheng, H.-J. Post-infectious bronchiolitis obliterans in children: A review of 42 cases. BMC Pediatr. 2014, 14, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plesca, D.A.; Luminos, M.; Spatariu, L.; Stefanescu, M.; Cinteza, E.; Balgradean, M. Postinfectious arthritis in pediatric practice. Maedica 2013, 8, 164–169. [Google Scholar]

- Lilleberg, H.S.; Eide, I.A.; Geitung, J.T.; Svensson, M.H.S. Akutt glomerulonefritt utløst av parvovirus B19. Tidsskr. Den Nor. Legeforen. 2018. Available online: https://tidsskriftet.no/2018/10/kort-kasuistikk/akutt-glomerulonefritt-utlost-av-parvovirus-b19 (accessed on 30 October 2018). [CrossRef]

- Mancera-Páez, O.; Román, G.C.; Pardo-Turriago, R.; Rodríguez, Y.; Anaya, J.-M. Concurrent Guillain-Barré syndrome, transverse myelitis and encephalitis post-Zika: A case report and review of the pathogenic role of multiple arboviral immunity. J. Neurol. Sci. 2018, 395, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blitz, J.; Riddle, M.S.; Porter, C.K. The Risk of Chronic Gastrointestinal Disorders Following Acute Infection with Intestinal Parasites. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubber, A.; Moorthy, A. Reactive arthritis: A clinical review. J. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb. 2021, 51, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, E. T cells in reactive arthritis. APMIS 1993, 101, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, K.; Rostami-Nejad, M.; Al Dulaimi, D. Post gastroenteritis gluten intolerance. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2015, 8, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Joli, J.; Buck, P.; Zipfel, S.; Stengel, A. Post-COVID-19 fatigue: A systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 947973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messiah, S.E.; Xie, L.; Mathew, M.S.; Shaikh, S.; Veeraswamy, A.; Rabi, A.; Francis, J.; Lozano, A.; Ronquillo, C.; Sanchez, V.; et al. Comparison of Long-Term Complications of COVID-19 Illness among a Diverse Sample of Children by MIS-C Status. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flokas, M.E.; Bustamante, V.H.; Kanakatti Shankar, R. New-Onset Primary Adrenal Insufficiency and Autoimmune Hypothyroidism in a Pediatric Patient Presenting with MIS-C. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2022, 95, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, J.; Cohen, M.; Zapater, J.L.; Eisenberg, Y. Primary Adrenal Insufficiency After COVID-19 Infection. AACE Clin. Case Rep. 2022, 8, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, M.; Iatridi, F.; Chalkidis, G.; Lioulios, G.; Nikolaidou, C.; Badis, K.; Fylaktou, A.; Papagianni, A.; Stangou, M. ANCA-Associated Vasculitis May Result as a Complication to Both SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Vaccination. Life 2022, 12, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiff, D.D.; Meyer, C.G.; Marlin, B.; Mannion, M.L. New onset ANCA-associated vasculitis in an adolescent during an acute COVID-19 infection: A case report. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, M.C.; Spencer, L.T.; Yalcindag, A. A case of ANCA-associated vasculitis in a 16-year-old female following SARS-CoV-2 infection and a systematic review of the literature. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 2022, 20, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fireizen, Y.; Shahriary, C.; Imperial, M.E.; Randhawa, I.; Nianiaris, N.; Ovunc, B. Pediatric P-ANCA vasculitis following COVID-19. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2021, 56, 3422–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, W.T.; Campbell, J.A.; Ross, F.; Peña Jiménez, P.; Rudzinski, E.R.; Dickerson, J.A. Acute ANCA Vasculitis and Asymptomatic COVID-19. Pediatrics 2021, 147, e2020033092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDougall, M.; El-Hajj Sleiman, J.; Beauchemin, P.; Rangachari, M. SARS-CoV-2 and Multiple Sclerosis: Potential for Disease Exacerbation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 871276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khair, A.M.; Nikam, R.; Husain, S.; Ortiz, M.; Kaur, G. Para and Post-COVID-19 CNS Acute Demyelinating Disorders in Children: A Case Series on Expanding the Spectrum of Clinical and Radiological Characteristics. Cureus 2022, 14, e23405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, D.; Bhattacharjee, H.; Rehman, O.; Deori, N.; Magdalene, D.; Bharali, G.; Mishra, S.; Godani, K. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder post-COVID-19 infection: A rare case report from Northeast India. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 70, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, F.; Julio, K.; Méndez, G.; Valderas, C.; Echeverría, A.C.; Perinetti, M.J.; Suarez, N.M.; Barraza, G.; Piñera, C.; Alarcón, M.; et al. Neurologic Features Associated With SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Children: A Case Series Report. J. Child Neurol. 2021, 36, 853–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, L.; Krishna, D.; Tiwari, S.; Goyal, J.P.; Kumar, P.; Khera, D.; Choudhary, B.; Didel, S.; Gadepalli, R.; Singh, K. Post-COVID-19 Immune-Mediated Neurological Complications in Children: An Ambispective Study. Pediatr. Neurol. 2022, 136, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carta, A.; Bellucci, C.; Tagliavini, V.; Turco, E.C.; Farci, R.; Cerasti, D.; Bozzetti, F.; Mora, P. Atypical presentation of juvenile multiple sclerosis in a patient with COVID-19. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçay, N.; Bektaş, G.; Menentoğlu, M.E.; Oğur, M.; Sofuoğlu, A.İ.; Palabiyik, F.B.; Şevketoğlu, E. COVID-19–associated Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis–like Disease in 2 Children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021, 40, e445–e450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyrazoğlu, H.G.; Kırık, S.; Sarı, M.Y.; Esen, İ.; Toraman, Z.A.; Eroğlu, Y. Acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis and transverse myelitis in a child with COVID-19. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2022, 64, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cay-Martínez, K.C.; Shen, M.Y.; Silver, W.G.; Vargas, W.S. Postinfectious Encephalomyelitis Associated With Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody in a Pediatric Patient with COVID-19. Pediatr. Neurol. 2021, 124, 40–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Miranda Henriques-Souza, A.M.; de Melo, A.C.M.G.; de Aguiar Coelho Silva Madeiro, B.; Freitas, L.F.; Sampaio Rocha-Filho, P.A.; Gonçalves, F.G. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in a COVID-19 pediatric patient. Neuroradiology 2021, 63, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, M.L.; Galati, C.; Gallo, C.; Santangelo, G.; Marino, A.; Guccione, F.; Pitino, R.; Raieli, V. ADEM post-SARS-CoV-2 infection in a pediatric patient with Fisher-Evans syndrome. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 42, 4293–4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urso, L.; Distefano, M.G.; Cambula, G.; Colomba, A.I.; Nuzzo, D.; Picone, P.; Giacomazza, D.; Sicurella, L. The case of encephalitis in a COVID-19 pediatric patient. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 43, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Morales, A.E.; Urrutia-Osorio, M.; Camacho-Mendoza, E.; Rosales-Pedraza, G.; Dávila-Maldonado, L.; González-Duarte, A.; Herrera-Mora, P.; Ruiz-García, M. Neurological manifestations temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in pediatric patients in Mexico. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2021, 37, 2305–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivan, A.P.; Odajiu, I.; Popescu, B.O.; Davidescu, E.I. COVID-19 Associated Guillain–Barré Syndrome: A Report of Nine New Cases and a Review of the Literature. Medicina 2022, 58, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mezzeoui, S.; Aftiss, F.z.; Aabdi, M.; Bkiyar, H.; Housni, B. Guillan barre syndrome in post COVID-19 infection in children. Ann. Med. Surg. 2021, 67, 102524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, H.S.C.; de Castro, P.N.P.; Ventura, N.; Leite, L.C.; Rego, C.T.O.; Santos, R.Q.D.; Machado, D.C.; Zaeyen, E.J.B. COVID-19-related Guillain-Barré Syndrome variant with multiple cranial neuropathies in a child. EuroRad 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, M.; Bhumbra, S.; Felker, M.V.; Jordan, B.L.; Kim, J.; Weber, M.; Friedman, M.L. Guillain-Barré syndrome in a child with COVID-19 infection. Pediatrics 2021, 147, e2020015115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, B.; Aggarwal, V.; Kumar, P.; Kundal, M.; Gupta, D.; Kumar, A.; Dugaya, S.K. COVID-19 associated severe multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children with encephalopathy and neuropathy in an adolescent girl with the successful outcome: An unusual presentation. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 24, 1276–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khera, D.; Didel, S.; Panda, S.; Tiwari, S.; Singh, K. Concurrent Longitudinally Extensive Transverse Myelitis and Guillain-Barré Syndrome in a Child Secondary to COVID-19 Infection. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021, 40, e236–e239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.Y.; Midhun Raj, K.T.; Samprathi, M.; Sridhar, M.; Adiga, R.; Vemgal, P. Guillain–Barré Syndrome Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Indian J. Pediatr. 2021, 88, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, C.H.M.; Almeida, T.V.R.; Marques, E.A.; de Sousa Monteiro, Q.; Feitoza, P.V.S.; Borba, M.G.S.; Vasconcelos, H.L.; de Souza Bastos, M.; Lacerda, M.V.G. Guillain–Barré Syndrome Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection in a Pediatric Patient. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2021, 67, fmaa044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paybast, S.; Gorji, R.; Mavandadi, S. Guillain-Barré Syndrome as a Neurological Complication of Novel COVID-19 Infection. Neurologist 2020, 25, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Haboob, A.A. Miller Fischer and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndromes post COVID-19 infection. Neurosciences 2021, 26, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, M.B.; Montenegro, R.C.; de Araújo Coimbra, P.P.; de Queiroz Lemos, L.; Fiorenza, R.M.; da Silva Fernandes, C.J.; Pessoa, M.S.L.; Rodrigues, C.L.; da Cruz, C.G.; de Araújo Verdiano, V.; et al. A wide spectrum of neurological manifestations in pediatrics patients with the COVID-19 infection: A case series. J. Neurovirol. 2021, 27, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnakumar, A.; Kewalramani, D.; Mahalingam, H.; Manokaran, R.K. Guillain–Barré Syndrome with Preserved Reflexes in a Child after COVID-19 Infection. Indian J. Pediatr. 2021, 88, 831–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, S.N.; Madaan, P.; Shekhar, M. An Unusual Descending Presentation of Pediatric Guillain-Barre Syndrome Following COVID-19: Expanding the Spectrum. Pediatr. Neurol. 2021, 124, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussinatto, I.; Benevenuta, C.; Caci, A.; Calvo, M.; Impastato, M.; Barra, M.; Genovese, E.; Timeus, F. Possible association between Guillain-Barré syndrome and SARS-CoV-2 infection in children: A case report and literature review. Exp. Ther. Med. 2022, 24, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terencio, B.B.; Patiño, R.F.; Jamora, R.D.G. Guillain-Barré Syndrome in a Pediatric Patient with COVID-19: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Acta Med. Philipp. 2021, 56, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanou, S.; Wardeh, L.; Govindarajan, S.; Macnay, K. Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) associated with COVID-19 infection that resolved without treatment in a child. BMJ Case Rep. 2022, 15, e245455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçay, N.; Menentoğlu, M.E.; Bektaş, G.; Şevketoğlu, E. Axonal Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a child. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 5599–5602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manji, H.K.; George, U.; Mkopi, N.P.; Manji, K.P. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with COVID-19 infection. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 35, 118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khalifa, M.; Zakaria, F.; Ragab, Y.; Saad, A.; Bamaga, A.; Emad, Y.; Rasker, J.J. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 detection and coronavirus disease 2019 in a child. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2020, 9, 510–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qamar, T.; Kumar, S.; Gupta, S.; Awasthi, S. Guillain–Barré Syndrome with Normal Nerve Conduction Study Associated with COVID-19 Infection in a Child. Indian J. Pediatr. 2022, 89, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, N.M.; Ferreira, L.C.; Dantas, D.P.; Silva, D.S.; dos Santos, C.A.; Cipolotti, R.; Martins-Filho, P.R. First Report of SARS-CoV-2 Detection in Cerebrospinal Fluid in a Child with Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021, 40, e274–e276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinazo-Bandera, J.M.; Hernández-Albújar, A.; García-Salguero, A.I.; Arranz-Salas, I.; Andrade, R.J.; Robles-Díaz, M. Acute hepatitis with autoimmune features after COVID-19 vaccine: Coincidence or vaccine-induced phenomenon? Gastroenterol. Rep. 2022, 10, goac014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborn, J.; Szabo, S.; Peters, A.L. Pediatric Acute Liver Failure Due to Type 2 Autoimmune Hepatitis Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Case Report. JPGN Rep. 2022, 3, e204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antala, S.; Diamond, T.; Kociolek, L.K.; Shah, A.A.; Chapin, C.A. Severe Hepatitis in Pediatric Coronavirus Disease 2019. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2022, 74, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamozo, S.; Brito-Zerón, P.; Sisó-Almirall, A.; Flores-Chávez, A.; Soto-Cárdenas, M.-J.; Ramos-Casals, M. Haemophagocytic syndrome and COVID-19. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 40, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenmyer, J.R.; Wyatt, K.D.; Milanovich, S.; Kohorst, M.A.; Ferdjallah, A. COVID-19-associated secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis requiring hematopoietic cell transplant. eJHaem 2022, 3, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rjoop, A.; Barukba, M.; Rusan, O.A. A rare case of post COVID-19 hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a pediatric patient. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2021, 156, S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]