Abstract

This study evaluated the effects of ammonium sulfate [(NH4)2SO4] addition and land-use history on greenhouse gas emissions (CH4, CO2, N2O) and inorganic nitrogen dynamics (NH4+ and NO3−) in Brazilian Cerrado soils. The objective was to determine how fertilization interacts with native and agricultural soils to regulate key biogeochemical processes. Soil samples from native and agricultural areas were collected in four regions (Araras, Sorocaba, Itirapina, and Brasília), representing contrasting pedoclimatic conditions and soil textures under different cropping systems. Samples were incubated under controlled conditions, with greenhouse gas fluxes analyzed by gas chromatography and inorganic nitrogen concentrations determined by colorimetric methods. Nitrogen fertilization inhibited CH4 consumption in native and agricultural soils and reversed fluxes to emissions in sandy soils. CO2 emissions increased in native soils but decreased in agricultural soils, suggesting effects of soil fertility and carbon stocks. N2O emissions increased mainly in native soils, reflecting intensified nitrification and denitrification, whereas agricultural soils responded heterogeneously. Nitrogen addition altered NH4+ and NO3− consumption, indicating enhanced oxidation and microbial assimilation. These results demonstrate that land-use history influences soil biogeochemical responses to nitrogen, underscoring the importance of site-specific fertilization in mitigating emissions and promoting sustainability in the Cerrado.

1. Introduction

The Brazilian Cerrado’s soils are typically characterized by low fertility, high acidity, and limited organic matter content, posing significant challenges to agricultural productivity [1]. These constraints necessitate intensive management practices, such as fertilization, to enable crop production [1,2].

Nitrogen fertilizers are key to boosting crop yields in Cerrado agriculture but pose risks by affecting soil biogeochemical processes [1,3]. Nitrogen inputs stimulate microbial activities such as nitrification and denitrification, which can increase emissions of nitrous oxide (N2O), a potent GHG with a global warming potential approximately 300 times greater than that of carbon dioxide (CO2) [4,5]. Moreover, different land uses, such as agriculture, may contribute to methane (CH4) emissions under anaerobic conditions, such as those caused by soil compaction, and increase CO2 fluxes due to enhanced microbial respiration [6]. Poorly managed fertilization can lead to nutrient leaching, soil acidification, and increased GHG emissions, compromising the sustainability of this biome [3,7].

The Brazilian Cerrado occupies approximately 2 million km2, representing about 23% of Brazil’s territory, and is considered one of the country’s main agricultural frontiers due to its strategic role in food production, biodiversity conservation, and the provision of ecosystem services [8]. Over the past five decades, the Cerrado has undergone rapid agricultural expansion, with large-scale cultivation of crops such as soybean, maize, and sugarcane, driven by the application of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers to address natural nutrient deficiencies [2]. While these practices have transformed the region into a global agricultural powerhouse, they have also raised concerns about environmental impacts, including GHG emissions, soil degradation, and alterations in nutrient cycling dynamics [7]. Additionally, GHG emissions in Brazil are significantly driven by the conversion of native vegetation, primarily forests, into agricultural land, contributing to approximately 70% of total emissions, according to estimates from the most recent National Inventory of Emissions and Removals of Greenhouse Gases and detailed in the Methodological Note of the MCTI 2025 [9].

Although the effects of N addition on gaseous N losses are well-known in acidic or high-organic-matter soils, this study is necessary to provide region-specific data for the Cerrado, where soils are highly weathered and sensitive to management changes. The selected regions—Araras, Sorocaba, Itirapina, and Brasília—are representative of contrasting pedoclimatic conditions, soil textures (sandy Cerrado soils, clay-rich Oxisols), and cropping systems, allowing for broader applicability. Unlike previous field studies, this controlled incubation assay isolates the effects of N addition and land-use history, revealing interactions not apparent in field conditions. The historical use of fertilizers, or fertilization history, also shapes soil organic matter stocks, potentially amplifying or mitigating these effects over time [10]. However, this study does not directly analyze microbial-mediated processes but infers their role through flux measurements.

Effective fertilizer management in the Cerrado is essential not only to optimize agricultural productivity but also to minimize ecological impacts. The development and adoption of appropriate soil management technologies, such as site-specific nitrogen fertilization strategies that consider soil nitrogen transformations and local soil properties, can enhance nitrogen use efficiency, reduce environmental impacts, and promote sustainable intensification [1,3]. Given the Cerrado’s role in global carbon and nitrogen cycles, understanding how nitrogen management affects soil processes across different locations is critical for guiding agricultural policies and climate change mitigation strategies.

This study investigates the effects of nitrogen addition and fertilization history on greenhouse gas emissions (CH4, CO2, and N2O) and nutrient consumption (NH4+ and NO3−) in four Cerrado sites: Araras, Brasília, Sorocaba, and Itirapina. Using a double factorial experimental design, the objective is to elucidate the main effects of nitrogen addition and fertilization history, as well as their interaction, providing insights into the biogeochemical responses of Cerrado soils to agricultural management. The results contribute to the development of sustainable fertilization management strategies, balancing productivity and environmental conservation in this strategic biome.

2. Results

The fluxes of methane (CH4), carbon dioxide (CO2), and nitrous oxide (N2O), as well as the consumption of nitrate (NO3−) and ammonium (NH4+), were evaluated under different combinations of land use (native and agricultural) and nitrogen application (with and without ammonium sulfate). Data were collected from four Cerrado sites—Araras, Sorocaba, Itirapina, and Brasília. Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations of gas emissions, soil pH, and NH4+ and NO3− concentrations for each site and land use.

Table 1.

Mean greenhouse gas fluxes (CH4, CO2, and N2O), pH, and inorganic nitrogen concentrations (NH4+ and NO3−) in soils under native vegetation and adjacent cultivated land at each study site.

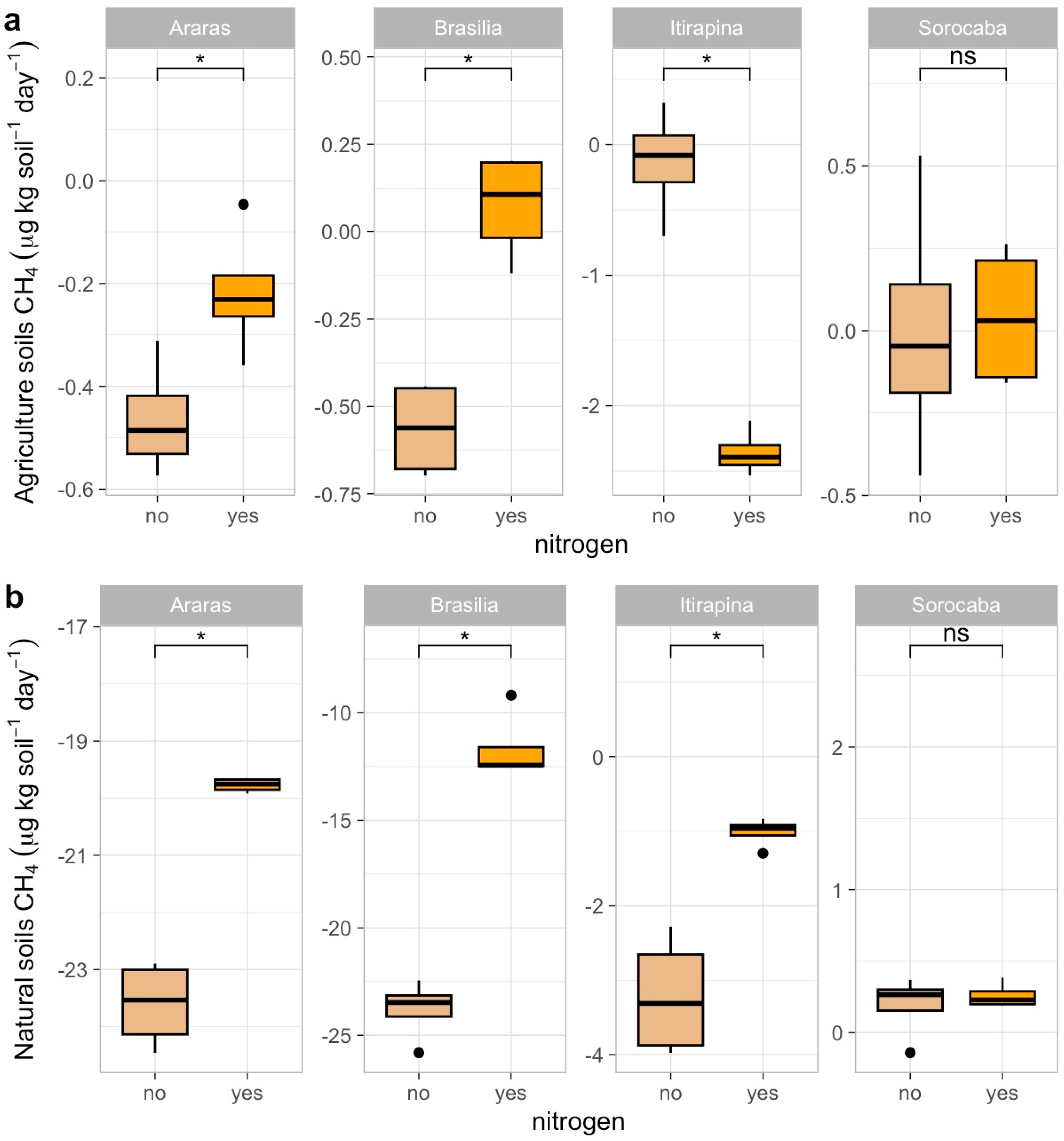

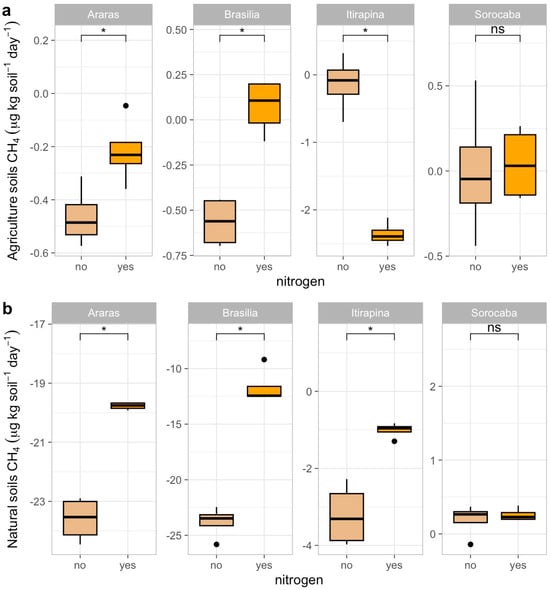

2.1. Effect of Ammonium Sulfate Addition on Methane (CH4) Fluxes

In agricultural soils, CH4 consumption decreased after ammonium sulfate addition in Araras (from −0.4 ± 0.2 to near 0 µg kg soil−1 day−1), Brasília (from −0.7 ± 0.1 to near 0 µg kg soil−1 day−1), and Itirapina, where consumption shifted to net emissions (from −0.2 ± 0.3 to +0.5 ± 0.2 µg kg soil−1 day−1) (Figure 1a). In Sorocaba, CH4 fluxes remained close to neutral (0.3 ± 0.1 µg kg soil−1 day−1), with no significant response to fertilization.

Figure 1.

Methane (CH4) fluxes in agricultural (a) and natural (b) soils from four Cerrado sites (Araras, Brasília, Itirapina, Sorocaba) in response to ammonium sulfate [(NH4)2SO4] addition. Boxplots represent mean values (box) and confidence intervals (lines), with points indicating outliers. “No” indicates the absence of nitrogen, and “yes” indicates nitrogen addition. Values are expressed in µg CH4 m−2 h−1, with scales adjusted for agricultural (a) and natural (b) soils. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments are indicated by asterisks (*), while “ns” denotes no significant difference.

In native soils, ammonium sulfate addition also reduced CH4 consumption in Araras (from −23.7 ± 0.5 to −5.2 ± 0.3 µg kg soil−1 day−1), Brasília (from −24.0 ± 0.8 to −6.0 ± 0.4 µg kg soil−1 day−1), and Itirapina (from −3.4 ± 0.6 to near 0 µg kg soil−1 day−1) (Figure 1b). Native soils from Sorocaba showed no significant variation, maintaining fluxes near 0.2 ± 0.1 µg kg soil−1 day−1.

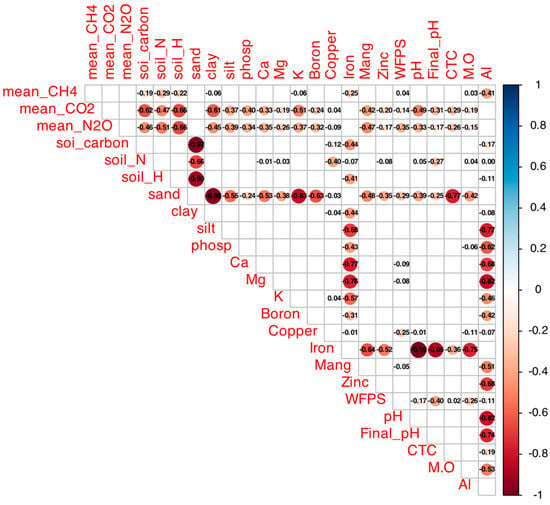

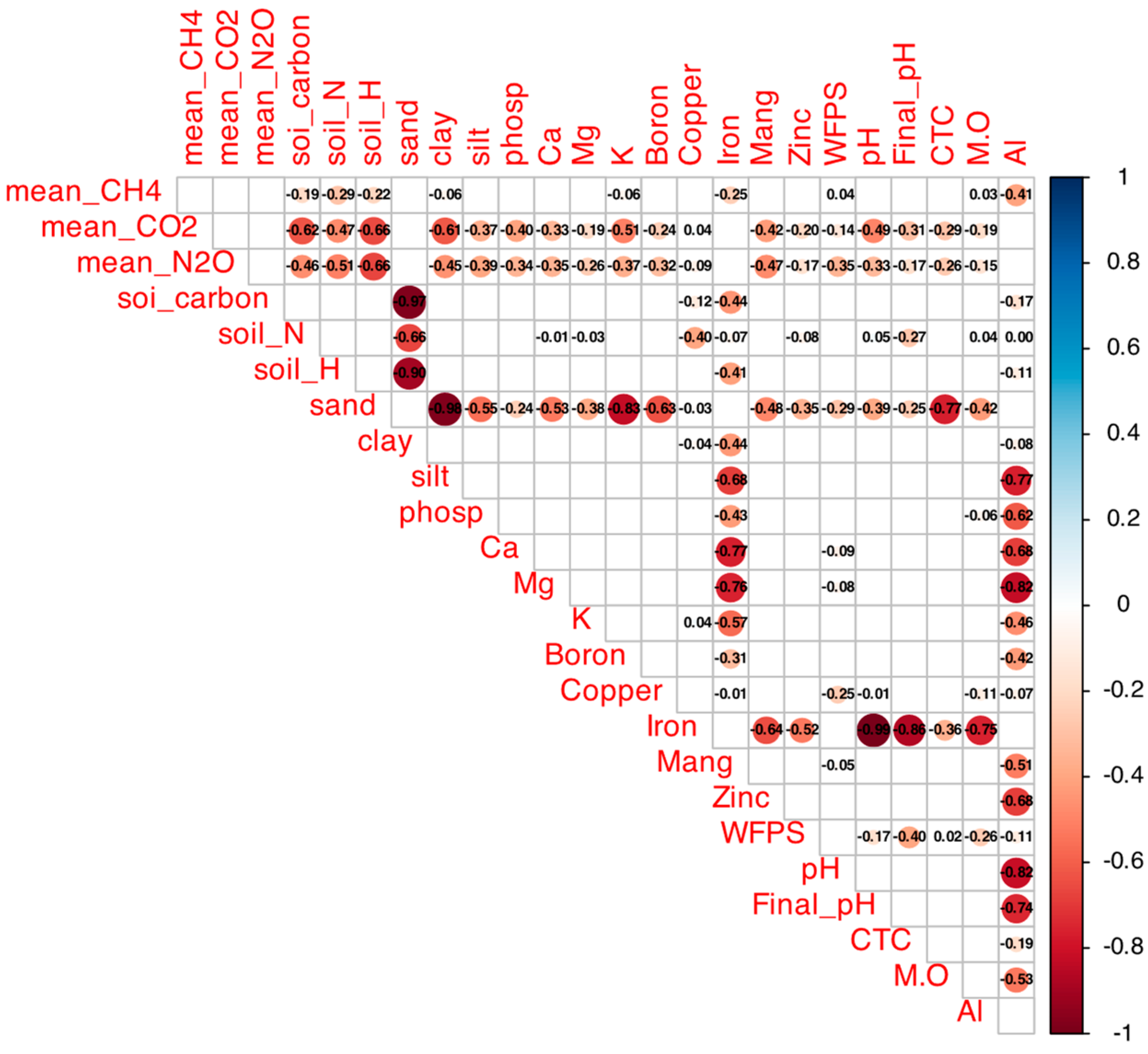

The correlation matrix (Figure A1) revealed negative correlations of CH4 fluxes with soil carbon content (r = −0.46, p < 0.05) and total nitrogen (r = −0.47, p < 0.05), a positive correlation with sand content (r = 0.55, p < 0.05), and a negative one with clay content (r = −0.55, p < 0.05). Baseline CH4 fluxes (Table 1) were −23.7 ± 0.5 µg kg soil−1 day−1 in native Araras, −24.0 ± 0.8 µg kg soil−1 day−1 in native Brasília, 0.2 ± 0.1 µg kg soil−1 day−1 in native Sorocaba, and −3.4 ± 0.6 µg kg soil−1 day−1 in native Itirapina.

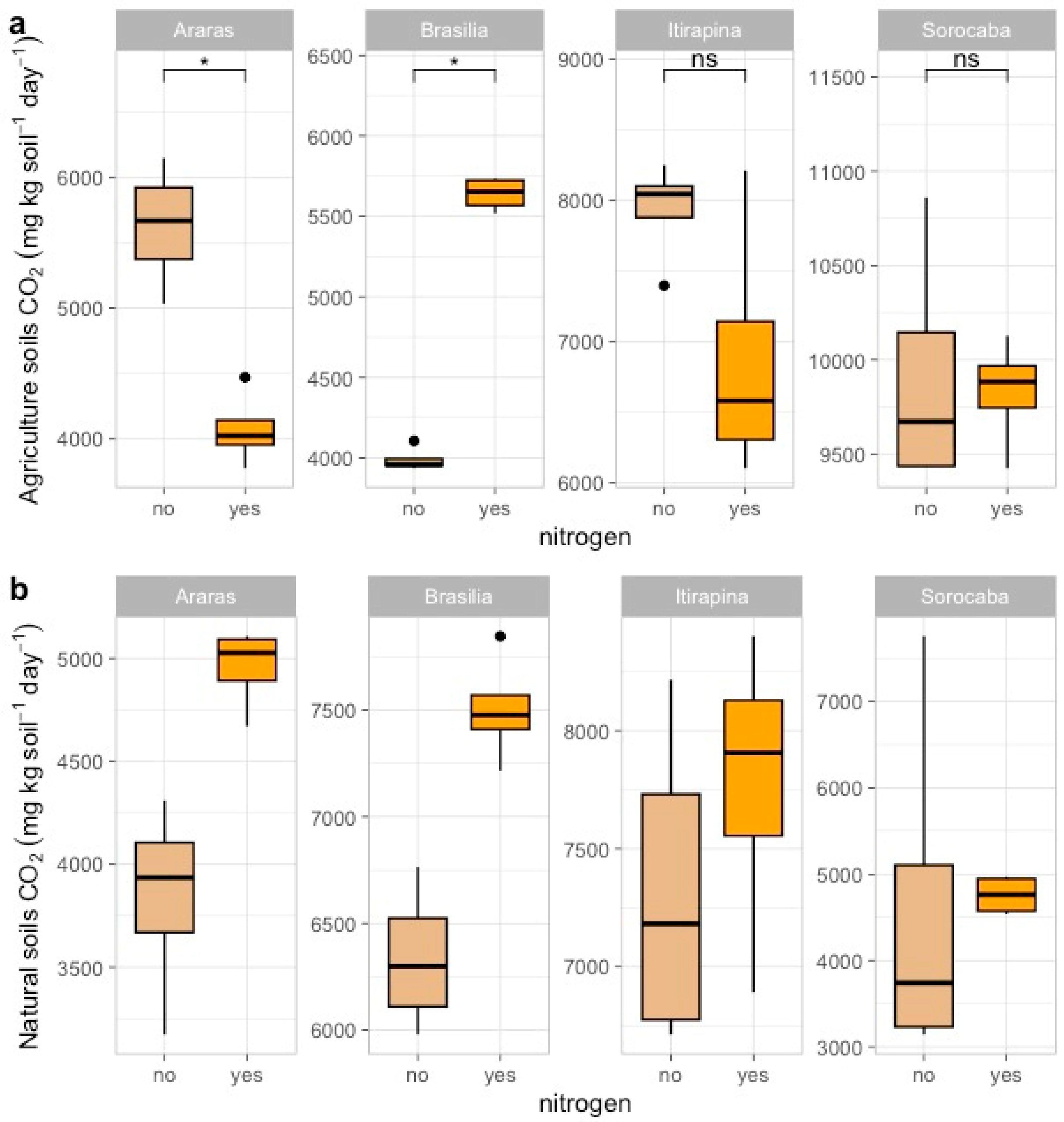

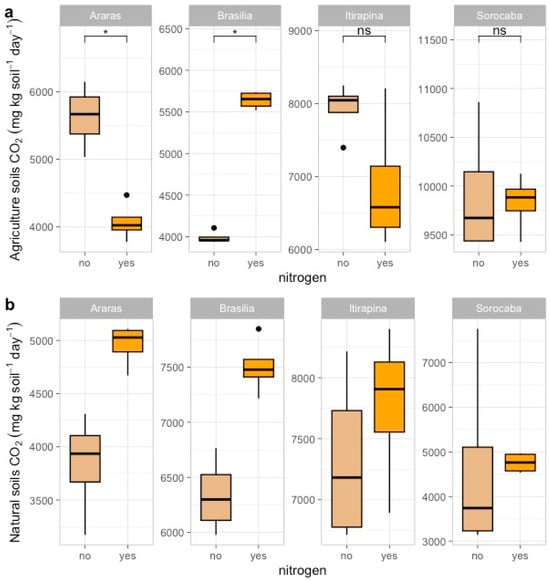

2.2. Effect of Ammonium Sulfate Addition on Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Fluxes

In agricultural soils, ammonium sulfate addition reduced CO2 emissions in Araras (from 7473.04 ± 4180.79 to 5200.50 ± 3000.12 mg kg soil−1 day−1), increased them in Brasília (from 4084.12 ± 1013.36 to 6000.75 ± 1200.45 mg kg soil−1 day−1), and caused no significant changes in Itirapina (8178.47 ± 3613.80 mg kg soil−1 day−1) or Sorocaba (11,010.61 ± 5245.86 mg kg soil−1 day−1) (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) fluxes in agricultural (a) and natural (b) soils from four Cerrado sites (Araras, Brasília, Itirapina, Sorocaba) in response to ammonium sulfate [(NH4)2SO4] addition. Boxplots represent mean values (box) and confidence intervals (lines), with points indicating outliers. “No” indicates the absence of nitrogen, and “yes” indicates nitrogen addition. Values are expressed in µg CO2 m−2 h−1, with scales adjusted for agricultural (a) and natural (b) soils. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments are indicated by asterisks (*), while “ns” denotes no significant difference.

In native soils, CO2 emissions increased in Araras (from 4287.08 ± 1951.41 to 6500.30 ± 2100.67 mg kg soil−1 day−1) and Brasília (from 6358.41 ± 1478.54 to 8200.90 ± 1600.33 mg kg soil−1 day−1), with no significant variation in Itirapina (7428.24 ± 2490.61 mg kg soil−1 day−1) or Sorocaba (4547.27 ± 2580.50 mg kg soil−1 day−1) (Figure 2b).

According to the correlation matrix (Figure A1), CO2 fluxes were positively correlated with total nitrogen (r = 0.66, p < 0.05) and clay content (r = 0.55, p < 0.05) and negatively correlated with sand content (r = −0.55, p < 0.05) and total carbon (r = −0.47, p < 0.05).

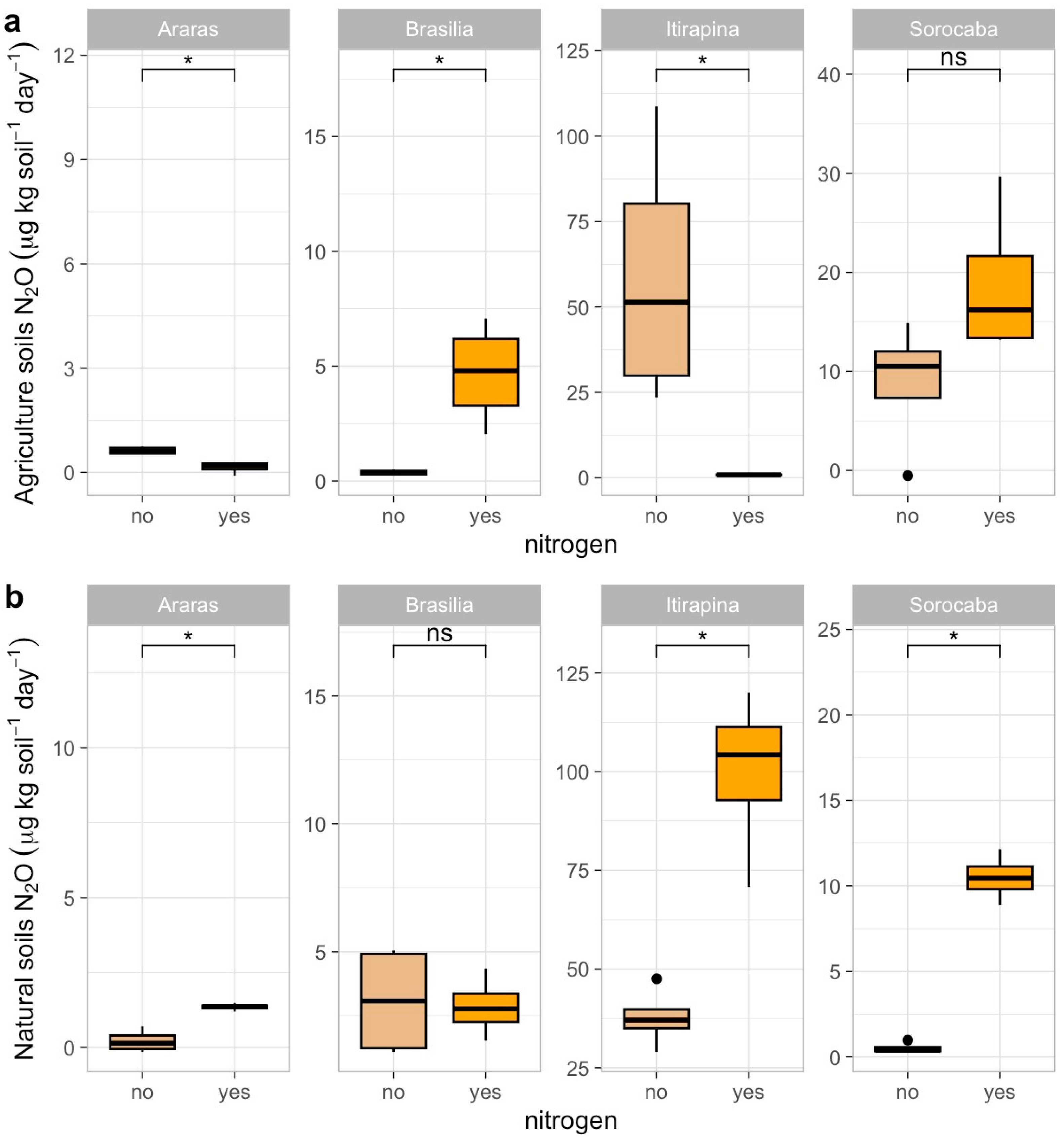

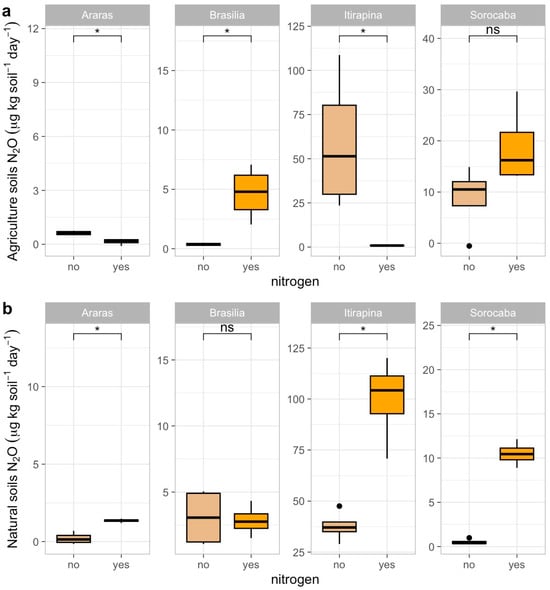

2.3. Effect of Ammonium Sulfate Addition on Nitrous Oxide (N2O) Fluxes

In agricultural soils, ammonium sulfate addition reduced N2O emissions in Araras (from 0.70 ± 1.79 to 0.10 ± 0.05 µg kg soil−1 day−1) and Itirapina (from 41.32 ± 80.62 to 10.50 ± 15.33 µg kg soil−1 day−1), increased them in Brasília (from 0.37 ± 0.38 to 1.20 ± 0.45 µg kg soil−1 day−1), and caused no significant changes in Sorocaba (12.92 ± 50.46 µg kg soil−1 day−1) (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Nitrous oxide (N2O) fluxes in agricultural (a) and natural (b) soils from four Cerrado sites (Araras, Brasília, Itirapina, Sorocaba) in response to ammonium sulfate [(NH4)2SO4] addition. Boxplots represent mean values (box) and confidence intervals (lines), with points indicating outliers. “No” indicates the absence of nitrogen, and “yes” indicates nitrogen addition. Values are expressed in µg N2O m−2 h−1, with scales adjusted for agricultural (a) and natural (b) soils. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments are indicated by asterisks (*), while “ns” denotes no significant difference.

In native soils, N2O emissions increased in Araras (from 0.42 ± 1.40 to 1.50 ± 0.60 µg kg soil−1 day−1), Itirapina (from 55.01 ± 51.27 to 75.20 ± 60.10 µg kg soil−1 day−1), and Sorocaba (from 2.68 ± 17.12 to 10.30 ± 20.05 µg kg soil−1 day−1), with no significant change in Brasília (2.18 ± 5.49 µg kg soil−1 day−1) (Figure 3b).

The correlation matrix (Figure A1) showed positive correlations of N2O fluxes with total nitrogen (r = 0.68, p < 0.05), total carbon (r = 0.62, p < 0.05), and clay content (r = 0.51, p < 0.05), and a negative correlation with sand content (r = −0.52, p < 0.05).

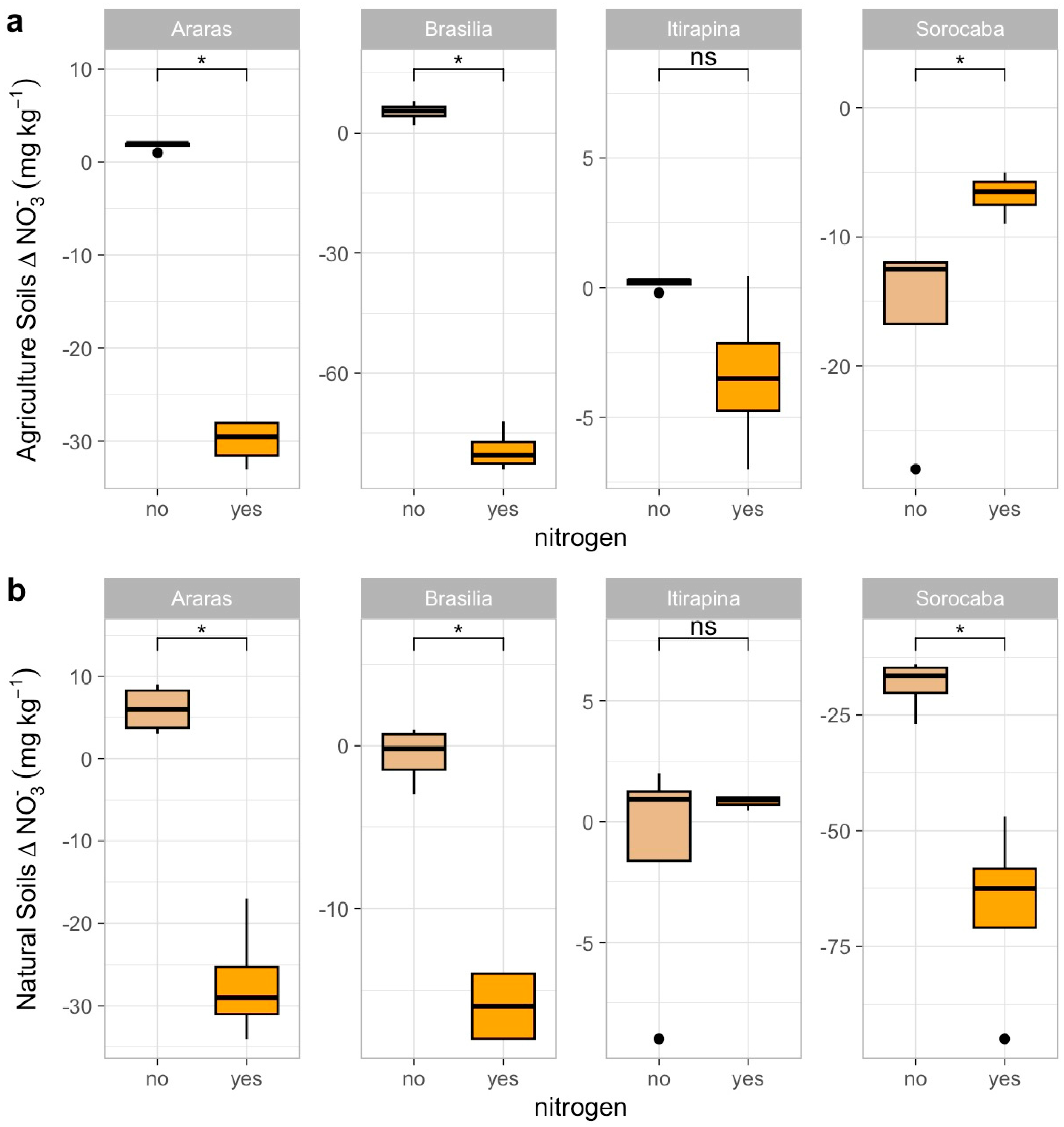

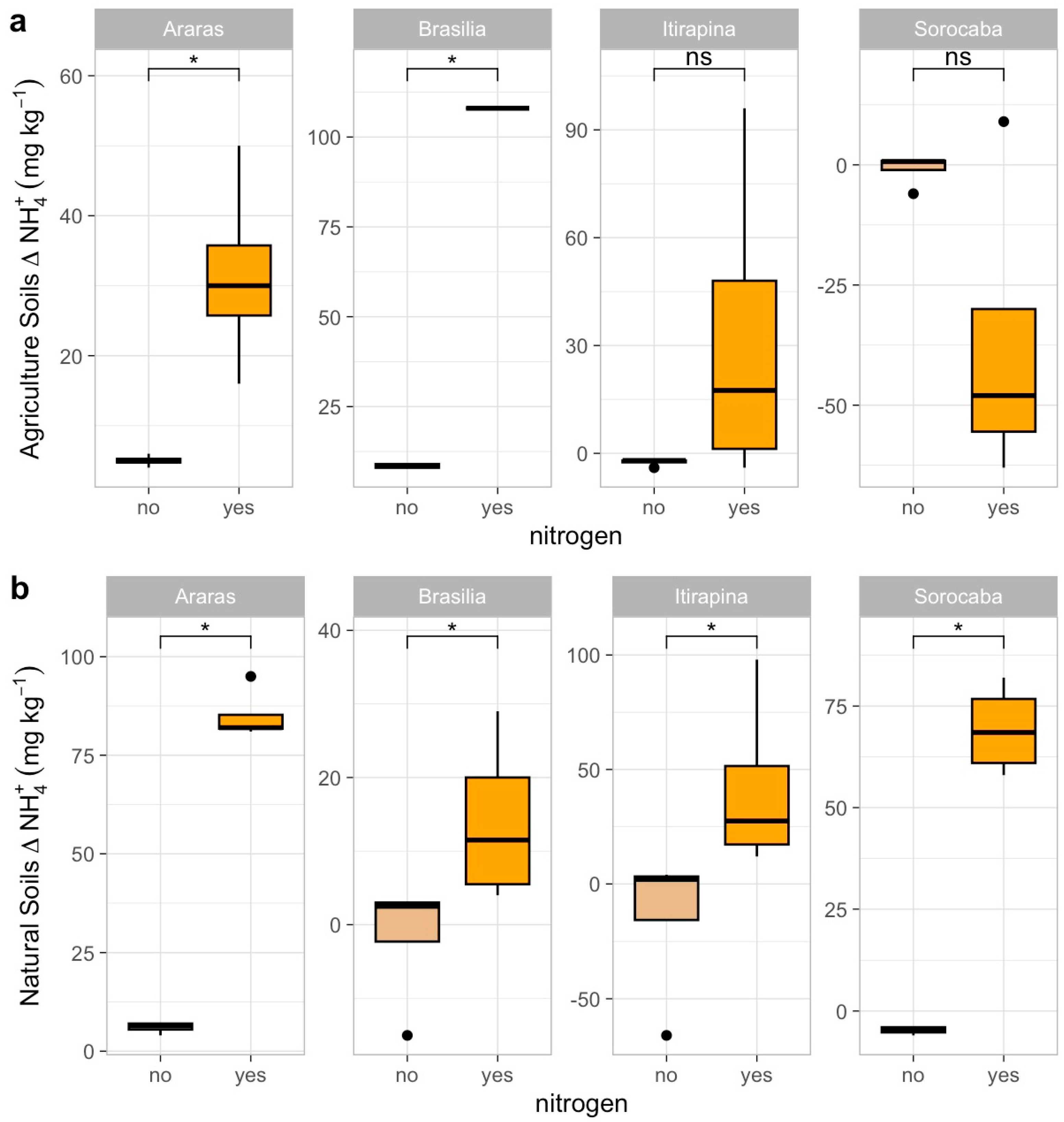

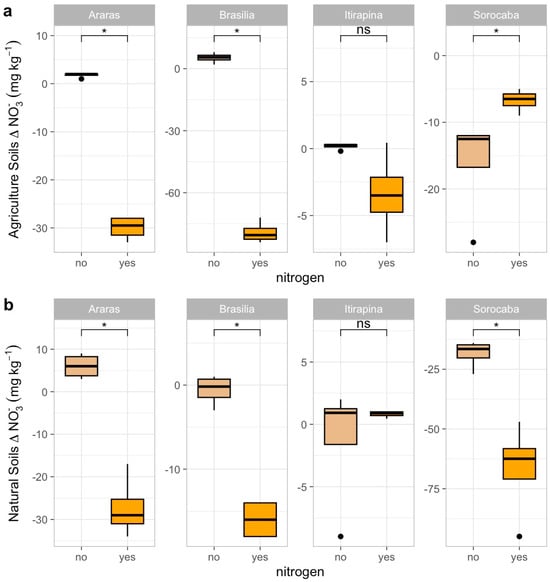

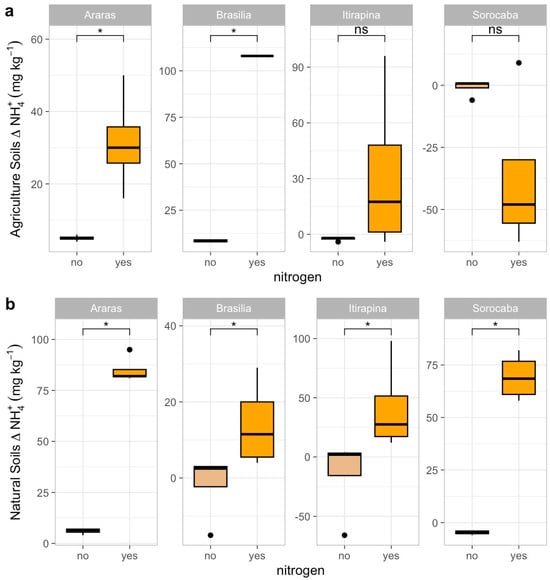

2.4. Effect of Ammonium Sulfate Addition on Nitrate and Ammonium Consumption

Ammonium sulfate addition influenced NO3− and NH4+ consumption patterns across sites and land uses (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Negative Δ values indicate net consumption (reduction in concentration), while near-zero or positive values indicate reduced consumption or accumulation.

Figure 4.

Variation in nitrate concentrations (Δ NO3−) in agricultural (a) and natural (b) soils from four Cerrado sites (Araras, Brasília, Itirapina, Sorocaba) in response to ammonium sulfate [(NH4)2SO4] addition. Boxplots represent mean values (box) and confidence intervals (lines), with points indicating outliers. “No” indicates the absence of nitrogen, and “yes” indicates nitrogen addition. Values are expressed in mg NO3− kg−1 soil, with scales adjusted for agricultural (a) and natural (b) soils. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments are indicated by asterisks (*), while “ns” denotes no significant difference.

Figure 5.

Variation in ammonium concentrations (Δ NH4+) in agricultural (a) and natural (b) soils from four Cerrado sites (Araras, Brasília, Itirapina, Sorocaba) in response to ammonium sulfate [(NH4)2SO4] addition. Boxplots represent mean values (box) and confidence intervals (lines), with points indicating outliers. “No” indicates the absence of nitrogen, and “yes” indicates nitrogen addition. Values are expressed in mg NH4+ kg−1 soil, with scales adjusted for agricultural (a) and natural (b) soils. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments are indicated by asterisks (*), while “ns” denotes no significant difference.

In agricultural soils, NO3− consumption decreased in Araras (Δ from −15.0 ± 3.2 to −2.5 ± 1.0 mg kg−1) and Brasília (Δ from −12.5 ± 2.8 to −1.8 ± 0.9 mg kg−1), increased in Sorocaba (Δ from −5.0 ± 1.5 to −20.0 ± 4.0 mg kg−1), and remained high in Itirapina (30.7 ± 5.2 mg kg−1) (Figure 4a). NH4+ consumption increased in Araras (Δ from −3.0 ± 0.8 to −10.5 ± 2.0 mg kg−1) and Brasília (Δ from −4.5 ± 1.0 to −12.0 ± 2.5 mg kg−1), was nearly complete in Itirapina (Δ from −1.0 ± 0.3 to −1.5 ± 0.4 mg kg−1), and showed no significant change in Sorocaba (Δ −1.2 ± 0.5 mg kg−1) (Figure 5a).

In native soils, NO3− consumption decreased in Araras (Δ from −10.0 ± 2.0 to −1.5 ± 0.7 mg kg−1) and Brasília (Δ from −8.0 ± 1.8 to −1.0 ± 0.5 mg kg−1), increased in Sorocaba (Δ from −15.0 ± 3.5 to −25.0 ± 5.0 mg kg−1), and showed no significant change in Itirapina (Δ −2.0 ± 0.6 mg kg−1) (Figure 4b). NH4+ consumption increased in Araras (Δ from −5.0 ± 1.2 to −15.0 ± 3.0 mg kg−1), Brasília (Δ from −6.0 ± 1.5 to −18.0 ± 3.5 mg kg−1), Itirapina (Δ from −3.5 ± 0.9 to −10.0 ± 2.0 mg kg−1), and Sorocaba (Δ from −4.0 ± 1.0 to −12.0 ± 2.5 mg kg−1) (Figure 5b).

The correlation matrix (Figure A1) showed that NO3− consumption was negatively correlated with total nitrogen (r = −0.55, p < 0.05), while NH4+ consumption was positively correlated with clay content (r = 0.48, p < 0.05) and negatively with sand content (r = −0.50, p < 0.05). Both nitrogen forms were positively correlated with total carbon (r = 0.45–0.50, p < 0.05).

3. Discussion

Ammonium sulfate addition increased N2O emissions mainly in native soils from Araras, Itirapina, and Sorocaba, indicating a strong stimulation of nitrification and denitrification under higher organic carbon availability. In contrast, agricultural soils showed a more heterogeneous response, suggesting that long-term management alters nitrogen transformation pathways. Similarly, the inhibition of CH4 oxidation, especially the reversal from sink to source in Itirapina, highlights the strong control exerted by soil texture and nitrogen availability on methanotrophic activity. This response suggests that sandy Cerrado soils may be particularly sensitive to nitrogen inputs, reinforcing the importance of considering local soil properties when interpreting greenhouse gas fluxes.

3.1. Effect of Ammonium Sulfate Addition on Methane (CH4) Fluxes

The reduction in CH4 consumption in agricultural and native soils of Araras, Brasília, and Itirapina, and the reversal of emissions in Itirapina’s agricultural soils, indicate that ammonium sulfate inhibits methanotrophic activity [11]. This aligns with Bodelier and Laanbroek’s findings that NH4+ competitively inhibits methane monooxygenase (MMO), reducing CH4 oxidation efficiency [11]. The pronounced effect in Itirapina suggests heightened sensitivity, possibly due to lower baseline methanotrophic populations or higher NH4+ availability [11]. In contrast, Sorocaba’s neutral CH4 balance, consistent with Nishisaka et al. [4], likely results from higher clay content limiting gas diffusivity, as clay-rich soils restrict O2 and CH4 access to methanotrophs [12,13].

The positive correlation with sand content (r = 0.55) and negative correlation with clay (r = −0.55) highlight the texture’s role in facilitating CH4 transport to oxidation zones [11,12,13]. Araras and Brasília, with sandy soils, exhibited high baseline consumption (−23.7 and −24.0 µg kg soil−1 day−1, respectively), comparable to Tate’s estimate of 8 kg C-CH4 ha−1 year−1 for high-oxidation soils [14,15]. The negative correlations with soil carbon (r = −0.46) and nitrogen (r = −0.47) suggest that fertile soils support robust methanotrophic communities, but nitrogen addition disrupts this balance [11]. Carmo et al. [16] reported similar seasonal reductions in CH4 consumption in Atlantic Forest soils with high NH4+ levels (~40 mg kg−1), reinforcing nitrogen’s inhibitory role [16].

An innovative perspective is the potential to use soil texture and microbial data to predict CH4 sink capacity in Cerrado soils. By mapping sand content and methanotrophic gene abundance (e.g., pmoA), precision agriculture could identify areas where reduced nitrogen inputs or organic amendments, like sugarcane straw [17], maintain CH4 sinks, enhancing the biome’s role in climate change mitigation.

3.2. Effect of Ammonium Sulfate Addition on Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Fluxes

The divergent CO2 responses—increased emissions in native Araras and Brasília soils, reduced emissions in agricultural Araras, and no significant changes in Itirapina and Sorocaba—reflect the complex interplay of nitrogen availability and carbon cycling [18]. Increased emissions in native soils align with Carmo et al.’s observations of enhanced microbial respiration in nitrogen-enriched tropical forests [16]. The reduction in agricultural Araras soils may result from nitrogen immobilization by high C:N ratio residues, as reported by Pitombo et al. in sugarcane fields [17]. Escanhoela et al. [19] noted similar suppression in organic orchards, suggesting management history influences carbon dynamics [19].

The positive correlation with total nitrogen (r = 0.66) indicates that nitrogen stimulates decomposer activity, intensifying organic matter mineralization [18]. The positive correlation with clay (r = 0.55) and negative correlation with sand (r = −0.55) suggest clay-rich soils, with greater water retention, favor respiration [13,18]. The negative correlation with total carbon (r = −0.47) implies that carbon-rich soils have stable stocks, reducing CO2 release, as seen in Escanhoela et al.’s low-carbon-dynamics orchards [19].

A novel insight is the opportunity to leverage soil carbon stability for carbon sequestration. By integrating texture and carbon stock data into predictive models, farmers could adjust nitrogen rates to minimize CO2 emissions in clay-rich soils while promoting residue incorporation in sandy soils to stabilize carbon, aligning with sustainable intensification goals [3,17].

3.3. Effect of Ammonium Sulfate Addition on Nitrous Oxide (N2O) Fluxes

The increased N2O emissions in native soils of Araras, Itirapina, and Sorocaba, and variable responses in agricultural soils (reductions in Araras and Itirapina, increases in Brasília), highlight the sensitivity of nitrification and denitrification to nitrogen inputs [4,16]. Native soils’ strong response, especially in Itirapina, suggests high nitrifying and denitrifying gene abundance, as noted by El-Hawwary et al. [18]. The reductions in agricultural Araras and Itirapina align with Pitombo et al. [16] findings that straw retention mitigates N2O emissions by immobilizing nitrogen. Brasília’s increased emissions may reflect favorable nitrification conditions, as seen in El-Hawwary et al.’s active agricultural soils [18]. Sorocaba’s moderate response in agricultural soils is consistent with Nishisaka et al.’s observations of low nitrogen dynamics due to moisture retention [4].

The positive correlations with total nitrogen (r = 0.68), carbon (r = 0.62), and clay (r = 0.51), and negative with sand (r = −0.52), indicate that fertile, clay-rich soils favor denitrification under anoxic conditions [16,17,18]. These patterns align with Carmo et al.’s reports of high emissions in moist tropical soils [16].

Innovatively, the variability in N2O responses suggests that real-time soil moisture and texture monitoring could optimize fertilizer timing. Precision tools, such as soil sensors, could reduce N2O emissions by applying nitrogen during drier periods in clay-rich soils, minimizing denitrification hotspots and supporting Cerrado sustainability [3].

3.4. Effect of Ammonium Sulfate Addition on Nitrate and Ammonium Consumption

The reduced NO3− consumption in Araras and Brasília (agricultural and native) and increased consumption in native Sorocaba reflect differences in nitrification saturation and microbial activity [17,20]. The high NO3− concentrations in agricultural Itirapina (30.7 mg/kg) indicate accelerated nitrification, consistent with O’Sullivan et al.’s findings in near-neutral soils [21]. Increased NH4+ consumption across most sites, particularly in Araras and Brasília, suggests enhanced oxidation by ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and archaea (AOA), as reported by Norton [22] and Leininger et al. [23]. Sorocaba’s lower NH4+ response in agricultural soils may stem from sandy textures limiting retention [21].

The negative correlation between NO3− consumption and total nitrogen (r = −0.55) and positive correlations between NH4+ consumption and clay (r = 0.48) and carbon (r ≈ 0.45–0.50) highlight the roles of fertility and texture in nitrogen cycling [4,17,18,20]. These align with Medeiros et al.’s observations of microbial immobilization in carbon-rich soils [20].

A novel contribution is the potential to use microbial community profiling (e.g., AOB/AOA abundance) alongside texture and pH data to predict nitrogen retention efficiency. This could inform variable-rate fertilization strategies, reducing nutrient losses and emissions while optimizing crop yields in the Cerrado [1,3].

3.5. Innovative Perspective: Precision Agriculture in the Cerrado

The results of this laboratory study indicate that Cerrado soils’ biogeochemical responses to nitrogen fertilization are highly site-specific, influenced by texture, carbon/nitrogen stocks, and microbial dynamics [1,11,17,18]. Although these findings come from microcosm experiments with soil collected in 2016, they suggest that soil heterogeneity could strongly affect nitrogen transformations and greenhouse gas fluxes. Future field research integrating soil texture mapping, microbial community analyses (e.g., methanotrophic, nitrifying, and denitrifying genes) [11,14,22,23], and nitrogen dynamics could inform site-specific strategies to optimize nutrient use and minimize CH4, CO2, and N2O emissions. For example, sandy soils such as Araras and Brasília may respond differently to nitrogen additions compared to clay-rich soils like Sorocaba, including potential differences in N2O emissions [4,16]. These insights highlight the potential importance of considering edaphic variability in the Cerrado when developing sustainable soil management approaches [1,3,17].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Design

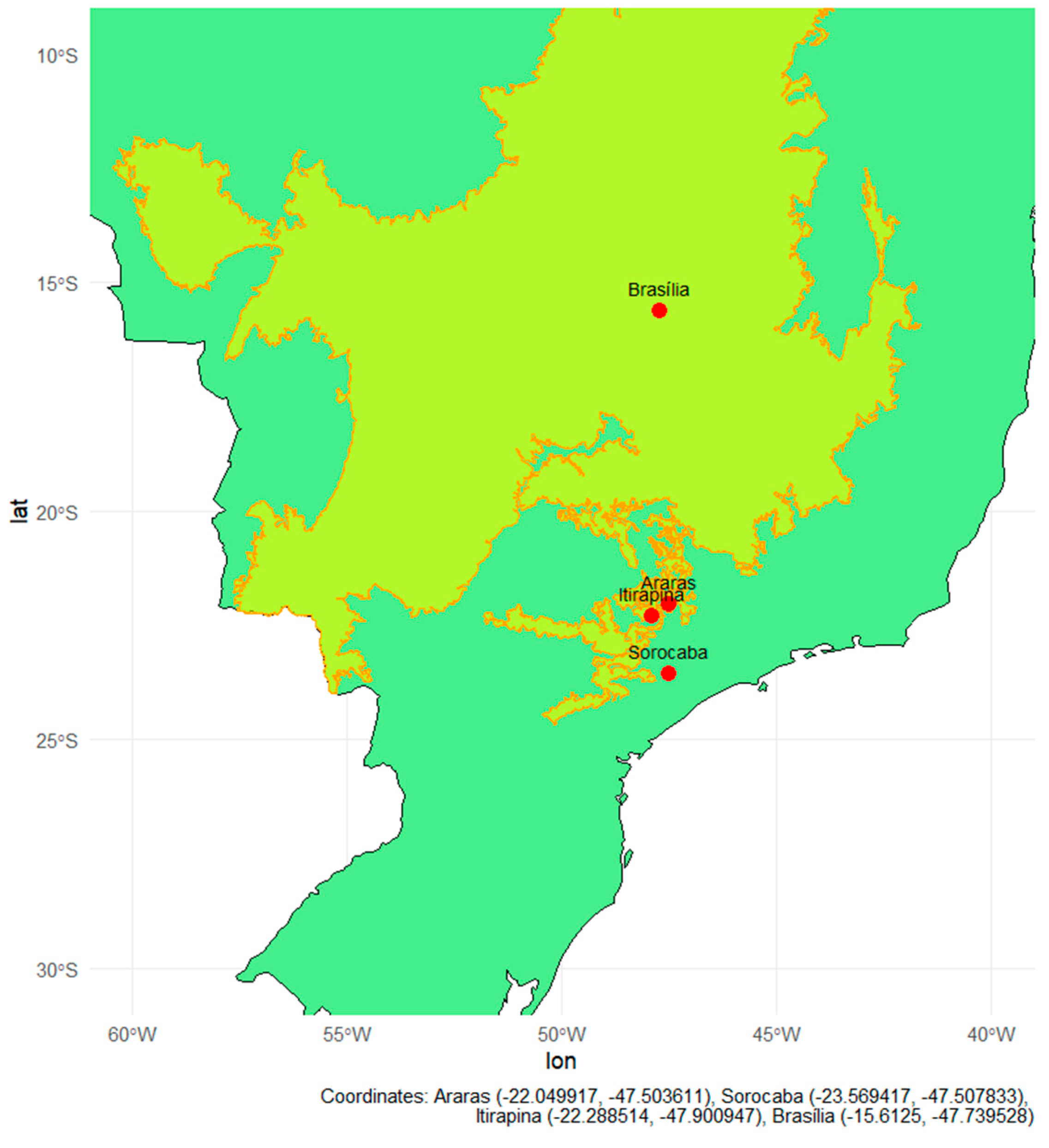

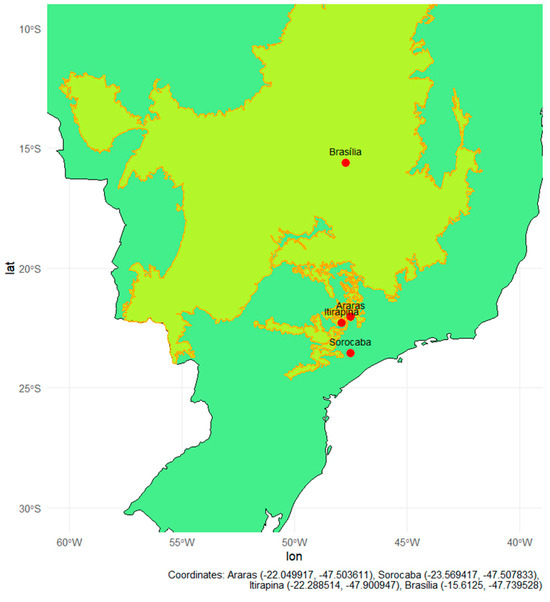

Soils were collected from four Brazilian regions, encompassing Cerrado areas and transition zones between Cerrado and Atlantic Forest, organized into pairs of adjacent natural and agricultural areas (Figure 6, Figure A1, Appendix A) [1]. The inclusion of both natural and cultivated soils was intentional to compare systems with and without a history of nitrogen fertilization and to evaluate how long-term nitrogen inputs alter soil microbial functions and ecosystem services, particularly methane oxidation and nitrogen transformation pathways. The criterion for inclusion in the experiment was that cultivated areas had a history of annual nitrogen fertilization, regardless of crop type. Four sites meeting this criterion were selected: Araras (SP), Sorocaba (SP), Itirapina (SP), and Brasília (DF), including two with perennial crops (citrus and sugarcane) and two with semi-perennial crops (sugarcane and maize/soybean rotation). thereby allowing the comparison between soils that differ in fertilization history and management intensity. These sites were selected to encompass contrasting pedoclimatic conditions, land-use histories, and soil textures, including sandy Cerrado soils (Itirapina) and transitional areas between the Cerrado and the Atlantic Forest (Araras and Sorocaba), with site information and soil characterization for these three areas provided by the local producers and the samples subsequently received and processed at the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), as well as clay-rich Oxisols from the Central Cerrado (Brasília), which were provided and chemically characterized by EMBRAPA Cerrados (Planaltina-DF).

Figure 6.

Map of Brazil highlighting the Cerrado biome (yellow area with Orange outline), based on IBGE shapefiles processed using R software, version 4.5.1. Red dots indicate collection sites in natural forest fragments located in the cities of Araras, Sorocaba, Itirapina, and Brasília. The geographic coordinates of the collection sites were overlaid on the country’s basemap using the ggplot2, sf, and rnaturalearth libraries.

This design allowed us to test whether nitrogen fertilization suppresses methane consumption and promotes a functional shift of soil microbial communities toward nitrate-oriented nitrogen transformations, evidencing a change in ecosystem services from methane mitigation to intensified nitrogen cycling.

The experimental design comprised four treatments: natural soil; natural soil with nitrogen addition; cultivated soil; and cultivated soil with nitrogen addition, each with eight replicates. This allowed for the evaluation of the effects of land use and nitrogen addition on CH4, CO2, and N2O gas fluxes, as well as nitrate and ammonium consumption.

4.2. Soil Sampling and Processing

Soils were collected from the 0–20 cm layer in the autumn of 2016, immediately after harvest, to avoid residual fertilizer effects [1]. Approximately 10 kg of soil was collected and air-dried. After drying, the soil was sieved through a 2 mm mesh, homogenized, and analyzed for chemical attributes according to the methods of van Raij et al. [24].

For the setup of eight microcosms (four replicates, with or without nitrogen addition), 3 to 5 kg of sieved soil was required, depending on the sample’s bulk density. Inorganic nitrogen, in the forms of NO3− and NH4+, was determined using colorimetric methods described by Norman et al. [25] and Krom [26]. Microcosms were set up according to Pitombo et al. [27], with pre-incubation at 40% moisture to stabilize microbial activity. Because soils differed in bulk density among sites (Table A1, Appendix A), the mass of soil varied accordingly, even though the same volume of soil was used in all microcosms. Soil amount was standardized by volume rather than by mass to optimize the experimental protocol and to ensure comparable physical conditions (e.g., aeration and pore space) within each site, allowing a consistent evaluation of nitrogen effects between control and nitrogen-amended treatments. In treatments with nitrogen addition, ammonium sulfate [(NH4)2SO4] was applied as an aqueous solution at a target concentration of 100 mg N kg−1 soil, corresponding to a nitrogen input equivalent to 50 kg N ha−1. Because soil bulk density differed among sites, the mass of soil contained in the fixed volume of 300 mL varied among microcosms, and the volume of solution added was adjusted according to the dry soil mass to ensure consistent nitrogen input across treatments. After pre-incubation, soil moisture was adjusted to 45%, and artificial root exudates were added, as described by van Zwieten et al. [28], to maintain the basal microbial respiration rate, which was used as a reference for CO2 fluxes. Measurements of N2O, CO2, and CH4 fluxes were performed using gas chromatography, with samples collected at different time intervals after microcosm closure, following the protocol described by Pitombo et al. [27]. Analyses were conducted on a Shimadzu GC 2014 chromatograph (Kyoto, Japan), calibrated daily with N2O, CO2, and CH4 standards at varying concentrations. The system was equipped with a packed HayeSep™ N column (1.5 m, 80–100 mesh) for N2O separation and a packed Shimalite™ Q column (0.5 m, 100–180 mesh) for CH4 separation, while CO2 was quantified by flame ionization detection. Helium and nitrogen were used as carrier gases.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

To evaluate the effects of nitrogen treatment on soil gas fluxes (CH4, CO2, and N2O) and variations in ammonium (NH4+) and nitrate (NO3−) concentrations, non-parametric Dunn tests with Bonferroni correction were applied for multiple comparisons. This choice was justified by the lack of normality and homoscedasticity assumptions in some variables. Comparisons were conducted separately for agricultural and natural areas, considering stratification by experimental site. Results were summarized in boxplots, with adjusted significance values (p.adj) graphically overlaid on the distributions, highlighting significant differences between nitrogen treatments. Additionally, a Spearman correlation analysis was performed between physicochemical variables and gas fluxes to identify association patterns. Correlation coefficients were presented in a visual matrix (heatmap) constructed with the corrplot package, displaying only significant correlations (p < 0.05). All statistical analyses were conducted in the R environment (R Core Team, version 4.5.1) [29], using the ggplot2, ggpubr, rstatix, and corrplot packages.

5. Conclusions

The addition of ammonium sulfate [(NH4)2SO4] consistently altered the dynamics of greenhouse gas emissions and inorganic nitrogen consumption in Cerrado soils, with responses modulated by land use type and local characteristics. Overall, fertilization stimulated respiratory and nitrifying processes, increasing CO2 and N2O emissions and reducing CH4 oxidation. These results confirm that the conversion of native areas and the use of nitrogen fertilizers intensify greenhouse gas emissions, highlighting the need for management practices that mitigate these impacts. Native soils showed greater sensitivity to added nitrogen, with increased consumption of NH4+ and NO3− and elevated N2O emissions, indicating that mineral nitrogen inputs can destabilize natural cycling processes. In agricultural soils, responses were more moderate, with partial inhibition of CH4 oxidation and increased CO2 emissions, suggesting microbial adaptation to intensive management. Differences among sites, such as the higher CH4 oxidation capacity in the sandy soils of Araras and Brasília and the neutral balance in Sorocaba, underscore the role of edaphic factors, including texture, carbon content, and moisture, in regulating biogeochemical processes. Collectively, the results indicate that nitrogen fertilization disrupts the balance between oxidative and reductive soil processes, causing Cerrado ecosystems to shift from acting as sinks to emitting CH4, contributing to increased net greenhouse gas emissions and intensifying the role of these soils as sources of N2O.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.D.Q. and J.B.d.C.; methodology, R.H.T.; software, R.H.T.; validation, H.D.Q., R.H.T. and J.B.d.C.; formal analysis, H.D.Q.; investigation, H.D.Q.; resources, J.B.d.C.; data curation, H.D.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, H.D.Q.; writing—review and editing, R.H.T. and J.B.d.C.; visualization, H.D.Q. and R.H.T.; supervision, J.B.d.C.; project administration, J.B.d.C.; funding acquisition, J.B.d.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by São Paulo Research Foundation—FAPESP, grant number 12/50694-6, Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel—CAPES (Master’s scholarship to H.D.Q.), and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development—CNPq, Postdoctoral fellowship to Leonardo Machado Pitombo (151572/2018-6) and Productivity Grant to R.H.T. (305987/2025-9).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to FAPESP (grant number 12/50694-6), CAPES for the Master’s scholarship granted to H.D.Q., and CNPq for the Postdoc scholarship granted to Leonardo Machado Pitombo (151572/2018-6) and for the Productivity Grant to R.H.T. (305987/2025-9). During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used OpenAI’s GPT-5.2 (ChatGPT) for the purposes of improving clarity, grammar, and flow of the English text in sections of the manuscript. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CH4 | Methane |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| N2O | Nitrous Oxide |

| NH4+ | Ammonium |

| NO3− | Nitrate |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| FAPESP | São Paulo Research Foundation |

| CAPES | Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel |

| CNPq | National Council for Scientific and Technological Development |

| AOB | Ammonia-Oxidizing Bacteria |

| AOA | Ammonia-Oxidizing Archaea |

| MMO | Methane Monooxygenase |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Bulk density (BD) and particle density (PD) of soils from native and agricultural areas in the Cerrado sites (Brasília, Araras, Itirapina, and Sorocaba).

Table A1.

Bulk density (BD) and particle density (PD) of soils from native and agricultural areas in the Cerrado sites (Brasília, Araras, Itirapina, and Sorocaba).

| Site Type | Location | BD (g cm−3) | PD (g cm−3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native | Brasília | 0.98 | 2.28 |

| Agricultural | Brasília | 1.18 | 2.59 |

| Native | Araras | 0.96 | 2.48 |

| Agricultural | Araras | 0.96 | 2.12 |

| Native | Itirapina | 1.53 | 2.37 |

| Agricultural | Itirapina | 1.40 | 2.39 |

| Native | Sorocaba | 1.54 | 2.61 |

| Agricultural | Sorocaba | 0.96 | 1.90 |

Figure A1.

Spearman correlation matrix between mean GHG fluxes (CH4, CO2, N2O) and soil attributes (total C, total N, sand, clay, silt, P, Ca, Mg, K, B, Cu, Fe, Mn, Zn, WFP, initial/final pH, CEC, TOC, OM, Al) in native and agricultural soils from Cerrado sites. Colors indicate r values (blue: positive, up to 1; red: negative, down to −1); filled cells indicate p < 0.05 (empty: not significant). Generated with corrplot (R v4.5.1), data aggregated across treatments.

Figure A1.

Spearman correlation matrix between mean GHG fluxes (CH4, CO2, N2O) and soil attributes (total C, total N, sand, clay, silt, P, Ca, Mg, K, B, Cu, Fe, Mn, Zn, WFP, initial/final pH, CEC, TOC, OM, Al) in native and agricultural soils from Cerrado sites. Colors indicate r values (blue: positive, up to 1; red: negative, down to −1); filled cells indicate p < 0.05 (empty: not significant). Generated with corrplot (R v4.5.1), data aggregated across treatments.

References

- Lopes, A.S.; Guimarães Guilherme, L.R. A career perspective on soil management in the Cerrado region of Brazil. Adv. Agron. 2016, 137, 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.F.D.; Rodrigues, R.D.A.R.; Silveira, J.G.D.; Silva, J.J.N.D.; Daniel, V.D.C.; Segatto, E.R. Nitrous oxide emissions from a tropical Oxisol under monocultures and an integrated system in the Southern Amazon–Brazil. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2020, 44, e0190123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.C.; Bianchi, F.J.J.A.; Cardoso, I.M.; Fernandes, R.B.A.; Filho, E.I.F.; Schulte, R.P.O. Agroforestry systems can mitigate greenhouse gas emissions in the Brazilian Cerrado. Agrofor. Syst. 2020, 294, 106858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishisaka, C.S.; Youngerman, C.; Meredith, L.K.; do Carmo, J.B.; Navarrete, A.A. Differences in N2O fluxes and denitrification gene abundance in the wet and dry seasons through soil and plant residue characteristics of tropical tree crops. Front. Environ. Sci. 2019, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. In Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira Neto, M.; Piccolo, M.D.C.; Costa Junior, C.; Cerri, C.C.; Bernoux, M. Emissão de gases do efeito estufa em diferentes usos da terra no bioma Cerrado. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2011, 35, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.; Simões, S.J.; Dalla Nora, E.L.; de Sousa-Neto, E.R.; Forti, M.C.; Ometto, J.P. Agricultural expansion in the Brazilian Cerrado: Increased soil and nutrient losses and decreased agricultural productivity. Land 2019, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, E.E.; Rodrigues, A.A.; Martins, E.S.; Bettiol, G.M.; Bustamante, M.M.C.; Bezerra, A.S.; Bolfe, E.L. Cerrado ecoregions: A spatial framework to assess and prioritize Brazilian savanna environmental diversity for conservation. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 232, 818–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação [MCTI]. Nota Metodológica: Desagregação das Estimativas de Emissões e Remoções do Inventário Nacional de Gases de Efeito Estufa por Unidade Federativa (1990 a 2022); Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação: Brasília, Brazil, 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mcti (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Bodelier, P.L.E.; Pérez, G.; Veraart, A.J.; Krause, S. Methanotroph ecology, environmental distribution and functioning. In Methanotrophs: Microbiology Fundamentals and Biotechnological Applications; Lee, E.Y., Ed.; Microbiology Monographs; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 32, pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodelier, P.L.E.; Laanbroek, H.J. Nitrogen as a regulatory factor of methane oxidation in soils and sediments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004, 47, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hütsch, B.W. Tillage and land use effects on methane oxidation rates and their vertical profiles in soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1998, 27, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, B.C.; Smith, K.A.; Klemedtsson, L.; Brumme, R.; Sitaula, B.K.; Hansen, S.; Priemé, A.; MacDonald, J.; Horgan, G.W. The influence of soil gas transport properties on methane oxidation in soil. J. Environ. Qual. 1997, 26, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, K.R. Soil methane oxidation and land-use change: From process to mitigation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 80, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, S.J.; Sherlock, R.R.; Kelliher, F.M.; McSeveny, T.M.; Tate, K.R.; Condron, L.M. Pristine New Zealand forest soil is a strong methane sink. Glob. Change Biol. 2004, 10, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Carmo, J.B.; Sousa Neto, E.R.; Duarte-Neto, P.J.; Ometto, J.P.H.B.; Martinelli, L.A. Conversion of the coastal Atlantic forest to pasture: Consequences for the nitrogen cycle and soil greenhouse gas emissions. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 148, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitombo, L.M.; Cantarella, H.; Packer, A.P.C.; Ramos, J.C.; Carmo, J.B. Straw preservation reduced total N2O emissions from a sugarcane field. Soil Use Manag. 2017, 33, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hawwary, A.; Brenzinger, K.; Lee, H.J.; Dannenmann, M.; Ho, A. Greenhouse gas (CO2, CH4, and N2O) emissions after abandonment of agriculture. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2022, 58, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escanhoela, A.S.B.; Pitombo, L.M.; Brandani, C.B.; Navarrete, A.A.; Bento, C.B.; Carmo, J.B.D. Organic management increases soil nitrogen but not carbon content in a tropical citrus orchard with pronounced N2O emissions. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 234, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, E.; Cerri, C.E.P.; Cherubin, M.R.; Maia, S.M.F. Greenhouse gas emissions and carbon stock in agricultural soils of the Cerrado biome under different management systems. Soil Use Manag. 2021, 37, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, C.A.; Wakelin, S.A.; Tillman, R.W. Nitrogen cycling in grazed pastures at elevated CO2: N2O emissions and soil N dynamics. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2022, 122, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, J.M. Nitrification in agricultural soils. In Nitrogen in Agricultural Systems; Schepers, J.S., Raun, W.R., Eds.; American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 2008; pp. 173–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leininger, S.; Urich, T.; Schloter, M.; Schwark, L.; Qi, J.; Nicol, G.W.; Prosser, J.I.; Schuster, S.C.; Schleper, C. Archaea predominate among ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes in soils. Nature 2006, 442, 806–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Raij, B.; Andrade, J.C.; Cantarella, H.; Quaggio, J.A. Análise Química Para Avaliação da Fertilidade de Solos Tropicais; Instituto Agronômico: Campinas, Brazil, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, R.J.; Edberg, J.C.; Stucki, J.W. Determination of nitrate in soil extracts by dual-wavelength ultraviolet spectrophotometry. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1985, 49, 1182–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krom, M.D. Spectrophotometric determination of ammonia: A study of a modified Berthelot reaction using salicylate and dichloroisocyanurate. Analyst 1980, 105, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitombo, L.M.; Ramos, J.C.; Quevedo, H.D.; do Carmo, K.P.; Paiva, J.M.F.; Pereira, E.A.; do Carmo, J.B. Methodology for soil respirometric assays: Step by step and guidelines to measure fluxes. MethodsX 2018, 5, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Zwieten, L.; Singh, B.; Kimber, S.; Murphy, D.; Macdonald, L.; Rust, J.; Morris, S. An incubation study investigating the mechanisms that impact N2O flux from soil following biochar application. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 191, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.