Abstract

Background: Identifying factors associated with cognitive impairment among older adults is critical. This study investigates both concurrent and longitudinal associations between sleep quality, sleep duration, and cognitive performance among older adults in China, with particular emphasis on the moderating role of fruit and/or vegetable intake (FVI), a factor rarely examined in previous research. Methods: We pooled five waves of a specially designed nationwide sample of adults aged 65 years or older (N = 64,690; mean age: 86.3 years; men: 43.5%) in 2005, 2008, 2011, 2014, and 2018 in China. Cognitive impairment was assessed by the Mini-Mental State Examination. Among the sample, 10.7% were cognitively impaired. FVI was dichotomized into frequent (almost daily) versus infrequent (other low frequencies). Sleep hours were grouped into short (≤6 h), normal (7–9 h), and long (≥10 h) durations. Both concurrent and cross-lagged analyses were performed after adjusting for a wide set of covariates (demographics, socioeconomic status, family/social connections, health practices, disability, self-rated health, and chronic conditions). Analyses were further stratified by gender, age group, and urban–rural residence. Results: When all covariates were present (the full model), good sleep quality was associated with 22% lower odds of the prevalence of cognitive impairment, whereas the long sleep duration was associated with 24% higher odds as compared with the normal sleep duration. Although the short sleep duration was not associated with the prevalence of cognitive impairment in the full model, it was associated with 8% higher odds of cognitive impairment when health condition was not controlled for. Interaction analyses revealed that frequent FVI buffered the adverse cognitive effects of poor sleep quality and both short and long sleep durations. Subgroup analyses further show similar patterns across subpopulations, with more pronounced protective associations in older women and the oldest-old. Conclusions: Good sleep quality, normal sleep durations, and frequent FVI jointly contribute to better cognitive functioning at older ages. While the observed relationships are largely concurrent rather than causal, promoting both healthy sleep and dietary habits may be important for cognitive health among older adults.

1. Background

With the rapid population aging, the number of older people with age-related disorders will likely grow, especially people with cognitive impairment, the most common cause of dementia [1,2]. Dementia is considered one of the significant causes of disability among older adults and brings enormous social and financial burdens to both the family and societal levels [3]. It is estimated that around 50 million people lived with dementia worldwide in 2015, and the number is projected to increase to 132 million by 2050 [4]. Meanwhile, the dementia cost was as much as USD 818 billion in 2015 (1.1% of the global gross domestic product [GDP]), and it is projected to rise to USD 2 trillion by 2030 [5,6]. Since there are no effective therapies available for curing dementia so far, early identification of modifiable risk factors and the implementation of preventive interventions have become public health priorities [7,8].

Sleep is a fundamental biobehavioral process that helps to restore functional capacity and maintain both physical and mental health [9,10]. Sleep disturbances increase with age. More than half of older adults aged 65 years or older reported poor sleep quality [11]. The impacts of sleep problems, such as poor sleep quality [12,13,14], short or long durations of nighttime sleep [15,16,17], and longer and more frequent daytime napping [18,19], on cognitive functioning among older adults have been receiving increasing attention. The findings are generally consistent, with the majority of cross-sectional studies suggesting that a short sleep duration (usually 6 h or less) [20,21,22], a long sleep duration (usually 9 h or more) [23,24], or both (i.e., a U-shaped relationship or a V-shaped relationship) [25,26,27,28] are linked to an increased risk of cognitive impairment. Some studies have also suggested that poor sleep quality may be linked to an increased risk of cognitive impairment. However, a small number of studies have observed no association between sleep hours/quality and cognitive decline [29], and results from some longitudinal studies are also mixed [30,31,32], highlighting the need for replication in large, nationally representative samples.

One limitation of the existing literature is the limited attention to fruit and/or vegetable intake (FVI) as a potential moderator. Frequent FVI has been shown to improve the overall health condition of older adults by moderating several physical or psychological behaviors, including sleeping patterns [33,34]. Bioactive compounds in fruits and vegetables, such as polyphenols, melatonin, and serotonin, may reduce oxidative stress and improve sleep quality [35,36]. Plant-based diets may also enhance energy metabolism and mitochondrial function, thereby lowering risks of sleep disorders [37,38,39,40].

However, although many studies have linked FVI to cognitive health [41,42,43,44] and others have explored the relationship between sleep and cognition [12,15,25], very few have examined how FVI might interact with sleep to influence cognitive outcomes. Prior research typically treats FVI and sleep as independent predictors, overlooking their potential synergistic effects [33,35]. Moreover, the mechanistic pathways through which FVI might buffer the detrimental impact of poor or irregular sleep on cognition remain largely unexplored, especially in large, nationally representative aging populations. Therefore, examining FVI as a moderator provides a novel contribution to the existing literature by integrating nutritional and behavioral perspectives in understanding cognitive aging.

In addition, numerous studies indicated that frequent FVI was inversely associated with cognitive impairment because fruits and vegetables are rich in nutrients and phytochemicals with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [41,42,43,44]. Together, these lines of evidence suggest that FVI could moderate the relationship between sleep and cognitive function, an area that remains underexplored. However, despite the well-established validity and statistical robustness of sleep quality/duration in predicting cognitive functioning and the known associations between sleep and cognitive impairment [42,45], it remains largely unknown whether the linkage between sleep and cognitive function varies across different frequencies of intaking fruits and vegetables [46], a gap this study seeks to address.

Another limitation of the existing literature is the scarcity of subgroup or interaction analyses on sleep, FVI, and cognition in older adults. Findings from limited studies are inconsistent [32,47,48,49,50]. For instance, gender differences have been reported in Canada and China, yet patterns vary across populations. Similarly, research on FVI and cognition shows mixed gender and urban–rural results [51,52,53]. Furthermore, the oldest-old (≥80 years) remain underrepresented, despite their rapid cognitive decline [54]. These knowledge gaps motivated the present research.

China has the largest population of older adults in the contemporary world, with an estimated prevalence of dementia of approximately 6.6% in 2015–2018 among individuals aged 65 years and older [55,56,57]. With the rapid population aging and socioeconomic transformation, growing prevalence of unhealthy diets [58,59,60] and sleep disturbance [61,62], examining how sleep patterns and FVI jointly affect cognition among older adults in China is both timely and necessary. Yet, many studies still lacked national representativeness and were from a population-based sample [15,17,28,49,58,63,64], despite a growing number of studies in the field [48,65,66,67].

Taken together, the current study aims to a nationally representative dataset from mainland China from 2005 to 2018 to answer the following research questions: (1) whether FVI and sleep quality/duration are associated with the prevalence of cognitive impairment; (2) whether FVI could modify the relationship between sleep quality/duration and cognitive impairment; and (3) whether the above associations vary by gender, age group, and urban–rural residence area.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

The data used in our study were drawn from the 2005, 2008, 2011, 2014, and 2018 five waves of the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS). The CLHLS is an ongoing project in mainland China (hereafter China) and is one of the largest nationally representative longitudinal surveys focused on older adults in the developing world. The first three waves in 1998, 2000, and 2002 did not collect data on sleep and thus were excluded. The ninth wave conducted in 2021 was not publicly available. The field work of the tenth wave was just launched in October 2025.

The first 8 waves of the CLHLS were conducted in randomly selected half of the countries and cities from 22 of 31 provinces in mainland China (plus one county in one of nine not-sampled provinces). According to the last two national population censuses in 2010 and 2020, the survey areas covered nearly 87–90% of the total population of China [59,68]. The CLHLS was specially designed to interview all centenarians in sampled counties/cities. For non-centenarians, the CLHLS aimed to recruit samples with comparable sizes for ages from 65 to 99 by sex. Thus, although the CLHLS is not a random sample, it is a specially designed survey with oversampled very old adults and men.

Information on respondents’ sociodemographics, health status, and lifestyles was obtained through in-home interviews with high reliability and validity [59,69]. The response rate for each wave was approximately 90%. Further details of sampling design and data quality are available in refs. [59,69].

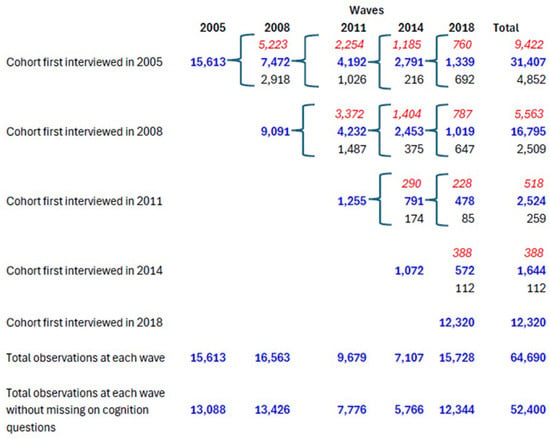

We pooled these five waves of data together to improve robustness, a common strategy in prior research [70,71]. The final sample included 39,351 respondents with 64,690 observations (see Figure A1 in the Appendix A for the structure of the sample; also see Table 1 for unweighted sample distribution and Appendix A Table A1 for weighted distribution).

Table 1.

Sample distributions of study variables, CLHLS 2005–2018.

2.2. Outcome Variables

Cognitive Impairment

Cognitive function was measured using the Chinese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [72], adapted from Folstein et al. [73] to suit the Chinese context. It contains six domains (orientation, registration, attention, calculation, recall, and language) with a total score of 30; lower scores indicate poor cognition. The Chinese version of MMSE has been widely validated and utilized in previous studies [72,74,75].

Cognition was dichotomized as impaired vs. unimpaired. Considering the low level of educational attainment among the oldest-old, particularly among rural women, we applied education-specific cut-offs following established studies [76,77,78,79]. Alternative criteria produced similar results. Cognitive impairment incidence was defined when a person unimpaired at Wave T became impaired at Wave T + 1 (≈3 years later).

All MMSE questions had to be answered by the respondents themselves; proxies were not permitted. About 19% of the respondents (≈8% weighted sample) across waves could not complete the MMSE due to mental or physical problems (coded as “not able to answer”). Following previous practices [70,80], we treated these as missing and imputed values using multiple imputation to reduce bias. The imputation assumed that respondents with similar demographic, behavioral, and health characteristics would provide comparable answers, which has been proven to be effective in dealing with missing data [81,82,83]. Some alternative approaches treating the “not able to answer” as “wrong” or dropping them from the analyses produced comparable results (see Appendix A Table A2).

2.3. Explanatory Variables

2.3.1. Sleep Quality and Duration

The CLHLS included one self-rated question about overall sleep quality: “How do you rate your overall sleep quality recently?” which is similar to Question 6 in the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [84]. The answer included five categories: very good, good, fair, poor, and very poor. We dichotomized response categories into good (very good/good) versus poor (fair/poor/very poor). Sleep duration was measured by the self-rated question: “How long do you sleep normally every day, including daytime naps?” Responses < 3 h or >20 h per day were considered implausible [85] and imputed as missing. To capture nonlinear relationships, sleep hours were grouped into short (≤6 h), normal (7–9 h), and long (≥10 h). For sensitivity analysis, a finer categorization used in prior studies [86,87,88,89] produced similar findings.

2.3.2. Fruit and/or Vegetable Intake

The CLHLS included self-rated frequency-based FVI by the following questions: “How often do you eat fresh fruits nowadays?” and “How often do you eat fresh vegetables nowadays?” The self-reported summary measure of FVI has been used in the literature [45,90]. Participants having fruits ‘every day or almost every day’ or ‘quite often’ or participants having vegetables ‘every day or almost every day’ were classified as frequent FVI or high frequency of FVI, and infrequent FVI otherwise.

2.4. Other Covariates

We controlled for multiple confounders established in prior studies [56,61,85]. These included four demographic variables (age, gender, ethnicity [Han vs. minority], and residence [urban vs. rural]), three socioeconomic status (SES) variables (education [1+ vs. 0 years], economic status [higher vs. lower], and adequate healthcare access [yes vs. no]), three variables reflecting family/social connections (marital status [currently married vs. not], number of living children, and co-residence [yes vs. no]), six dichotomous variables of health practices (smoking, alcohol drinking, regular exercise, tea drinking, meat intake, and fish intake [yes vs. no]), and three dichotomous variables of health conditions (self-rated poor health (SRH), ADL disabled, and having any chronic disease condition). ADL disability was defined as needing assistance in any of six basic activities (bathing/showering, dressing, indoor mobility, toileting, eating, and continence). Chronic disease covered 20 major illnesses (hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, cancer, etc.). When respondents could not answer factual questions, next-of-kin or caregivers provided verified proxy responses [83].

2.5. Analytical Strategy

Four nested random-intercept logistic regression models, accounting for intrapersonal correlation, were designed to fulfill our first research goal, which was to examine concurrent associations of sleep quality, sleep duration, and FVI with cognitive impairment using the pooled datasets. Model I included sleep quality, sleep duration, and FVI with covariates of demographic variables. Results that included each of sleep quality, sleep duration, and FVI with covariates of demographics were similar to those in Model I and thus not presented. Model II incorporated SES into Model I. Model III included family and social connections and health practices into Model II. Model IV further adjusted for SRH, ADL disability, and chronic disease conditions.

To test the role of FVI in moderating the relationship between sleep quality/duration and cognitive impairment (i.e., the second research goal), we included the interaction between frequent FVI and sleep (duration and quality) in Model IV. Furthermore, in order to test the robustness of these associations and the differences in subgroups (the third research goal), we also applied these designs to subgroups stratified by sex (men and women), age (young-old, aged 65–79 years; and oldest-old adults, aged 80 years or older), and rural–urban residence, thanks to the relatively large sample size of the CLHLS.

Following the common practice in the literature [17,48,57,87], sampling weight was not applied in the regression models because the variables used to construct the CLHLS sample weight were already controlled for in the model. Applying weights under these conditions can inflate standard errors and reduce precision [68,91]. An alternative approach of applying the sampling weight produced somewhat similar results. All analyses were performed using STATA v17.0, and the -xtlogit- command with a random intercept effect was used for all logistic regression models.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Table 1 presents the unweighted distribution of the sample characteristics of the 31,176 participants who took part in the four waves from 2005 to 2018, with 64,690 person-interviews or observations (see Table A1 for the weighted distribution). Among these samples, most were women, aged 80 or older, and rural residents. The majority of the participants reported often eating fruits and vegetables and having good sleep quality, and more participants reported having a normal sleep duration per day in comparison with the short and long sleep durations.

3.2. Sleep Quality/Duration, FVI, and the Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment

Table 2 shows that short sleep was associated with slightly higher odds (OR = 1.10, 95% CI: 1.02–1.19) of cognitive impairment, whereas a long sleep duration was associated with notably higher odds (OR = 1.46, 95% CI: 1.36–1.57). Frequent FVI was independently associated with 44% lower odds of cognitive impairment (OR = 0.60, 95% CI: 0.55–0.64).

Table 2.

Odds ratios of the prevalence of cognitive impairment for study variables, CLHLS, 2005–2018.

After sequentially adjusting for SES, family/social connections, and health practices (Models II–III), the protective association of good sleep quality persisted, though attenuated. In the full model (Model IV), good sleep quality remained associated with 22% lower odds (OR = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.73–0.84), and long sleep duration retained a 24% higher risk (OR = 1.24, 95% CI: 1.16–1.33). Frequent FVI remained consistently associated with reduced odds of cognitive impairment across all models, suggesting robust associations.

3.3. Interactions Between Sleep and FVI on the Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment

Table 3 shows the joint effects of sleep quality and FVI and of sleep duration and FVI. In Panel A, good sleep quality plus frequent FVI was associated with 45% lower odds of cognitive impairment (OR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.50–0.60) (see Column Total). Even among those with poor sleep, frequent FVI reduced the odds of cognitive impairment by 18% (OR = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.74–0.91). Good sleep quality but infrequent FVI was associated with 28% (OR = 0.72, 95% CI: 0.66–0.79) lower odds of cognitive impairment compared with fair/poor sleep quality but infrequent FVI. In Panel B, relative to normal-duration/infrequent FVI sleepers, those with short-duration/frequent FVI and long-duration/frequent FVI had 29% (OR = 0.71, 95% CI: 0.64–0.79) and 16% (OR = 0.84, 95% CI: 0.75–0.93) lower odds of cognitive impairment, respectively. These findings clearly demonstrate a moderating effect of frequent FVI, attenuating the detrimental influence of both insufficient and excessive sleep on cognitive health. Subgroup analyses further showed that the protective effects of frequent FVI were stronger among older women and the oldest-old (≥80 years), particularly for long sleep duration. Patterns were largely consistent among urban and rural residents.

Table 3.

Odds ratios of the prevalence of cognitive impairment for the interactions between sleep and FVI, CLHLS, 2005–2018.

3.4. FVI and Sleep Quality/Duration and Incidence of Cognitive Impairment

Table 4 shows odds ratios for incident cognitive impairment within three years. Good sleep quality was associated with 14–16% lower odds of incident impairment after adjusting for demographics, SES, and social support. However, the association became marginal when health conditions were additionally controlled. For sleep duration, only long sleep duration (≥10 h) was associated with a higher risk of incident impairment (≈14–16% higher odds), whereas short sleep was not significant in longitudinal models. FVI alone was not significantly associated with incidence after full adjustment.

Table 4.

Odds ratios of the incidence of cognitive impairment for study variables, CLHLS, 2005–2018.

Table 5 presents results for interaction terms. Most FVI–sleep interactions were nonsignificant in longitudinal models, suggesting that the moderating role of FVI operates more strongly at the concurrent level rather than over time.

Table 5.

Odds ratios of the incidence of cognitive impairment for the interactions between sleep and FVI, CLHLS, 2005–2018.

4. Discussion

This study, based on five waves of the CLHLS, examined associations between sleep quality, sleep duration, and cognitive impairment among Chinese adults aged 65 and older, and investigated whether FVI moderates these associations. The key findings are fourfold. First, good sleep quality and normal sleep duration (7–9 h) were associated with better cognitive functioning, whereas short (≤6) and long sleep duration (≥10 h) increased risk, revealing a U-shaped association between sleep duration and cognition among Chinese older adults. Second, frequent FVI was negative and independently associated with cognitive impairment. Third, frequent FVI buffered the adverse effects of poor sleep quality and abnormal sleep duration on cognitive impairment, particularly among women and the oldest-old. These findings advance previous research by demonstrating that FVI is not only beneficial on its own but also interacts synergistically with sleep to influence cognition. The moderating role of FVI had rarely been examined before, making this study a novel contribution in gerontological nutrition and sleep epidemiology. Fourth, longitudinal analyses revealed weak associations between sleep quality/duration, FVI, and cognitive impairment over three years, indicating likely concurrent rather than causal relationships.

Our findings on sleep quality/duration and cognitive impairment are supported by some neurological and pathological hypotheses. First, poor sleep quality is associated with higher rates of cortical atrophy in frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, which may have adverse effects on cognitive health, as shown in some prior studies [92]. Second, as sleep plays a vital role in the clearance of metabolic waste from the brain, insufficient sleep time may have negative effects on the brain [93]. Some experimental studies have demonstrated that sleep deprivation can not only result in neuronal losses in the locus coeruleus [94] but also induce pathology of Alzheimer’s disease, as well as an increased accumulation of amyloid β in the brain [85,95]. On the other hand, excessive sleep durations contribute to increases in systemic inflammation disorders [96], such as increases in activities in interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP) [92,97], which may have negative effects on brain structure and lead to age-related cognitive impairment [98]. Furthermore, both short sleep (≤6 h) and long sleep (≥10 h) durations may give rise to brain aging by increasing circadian dysfunction, degenerative disease [19,99], chronic inflammation [100], and risk of cardiometabolic disease [93,101].

Regarding FVI, our findings align with evidence that diets rich in antioxidants and polyphenols are linked to reduced cognitive decline [41,42,43,44,45,102]. Research has shown that fruits and vegetables contain rich antioxidant nutrients and bioactive substances, such as vitamins A\B\C\E, zinc, carotenoids, flavonoids, polyphenols [39,103], and phytoestrogens [104,105], which have been found to prevent the brain from oxidative stresses [102,106], and thus to help protect against damages of age-related neurologic dysfunction triggered by reactive oxygen species and other free radicals [41]. Additionally, frequent FVI also generates a high fiber intake that positively influences gut microbiota, which might also be linked to better cognitive health [41]. Finally, lignin and other phytochemicals such as catechins, L-theanine, and caffeine found in the Chinese diet might also explain the inverse association between FVI and cognitive impairment [45].

The significant moderating role of FVI in modifying the relationships between sleep quality/duration and cognitive impairment is noteworthy. Specifically, frequent FVI could offset higher odds of cognitive impairment for poor sleep quality and for short and long sleep durations. These are novel findings and a contribution to the existing literature, where no studies thus far have investigated the role of FVI in the sleep and cognitive relationship. There are several possible neurobiological explanations for these results. First, both proper sleep patterns and frequent FVI are positively associated with cognitive function through some biological mechanisms mentioned above. It is thus reasonable to postulate that interactions between proper sleep patterns (such as good sleep quality and normal sleep duration) and FVI could generate a mutually reinforcing effect on cognitive functioning.

Second, studies have shown that the accumulation of proteinaceous amyloid-β plaques [95,107] and tau (τ) oligomers [108] can begin several years before the onset of significant cognitive impairment [46]. Poor sleep quality or short sleep duration may negatively impact glymphatic system activity [109], thereby contributing to amyloid accumulation [110]. In this context, frequent FVI may play a protective role in supporting cognitive function by promoting healthier sleep patterns. Specifically, the polyphenols found in fruits and vegetables may influence sleep duration via the gut–brain axis, partly by enhancing mitochondrial function and energy metabolism involved in sleep regulation. Additionally, their antioxidant properties may help reduce oxidative stress or upregulate sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) protein expression, thereby improving sleep quality [35].

Third, short or long sleep duration often negatively affects the production of melatonin and other neurotransmitters, which leads to impaired cognitive functioning [111]. Given the fact that fruits and vegetables are important sources of these matters [112], it is logical to make inferences that frequent FVI might also help attenuate the reverse effects of both long and short sleep durations on cognitive function. Finally, cultural dietary patterns may also help interpret these results. In Chinese diets, vegetables are consumed in almost every meal, while fruits are often seasonal or viewed as supplementary rather than staple. Compared with Western diets, which may include larger servings of raw vegetables and fruit snacks, Chinese older adults’ intake patterns could produce smaller quantitative differences yet maintain substantial micronutrient diversity. This cultural distinction might partly explain the moderate but consistent protective associations found in our study. It is noteworthy that these interpretations are mostly our speculations based on findings from the existing literature. More research is clearly warranted to verify our speculations on the moderating role of FVI.

Unlike most previous studies, we have conducted subgroup analyses by age group, sex, and urban–rural residence, thanks to the large sample size of the analytical dataset used in the research. Our subgroup analyses suggest that the links of sleep quality/duration and FVI with cognitive impairment are mostly similar across different subpopulations, indicating that the above findings are robust in subpopulations. However, the role of frequent FVI in reducing higher odds of cognitive impairment seemed more pronounced in older women or oldest-old adults with a long sleep duration. On the one hand, older women, in general, have poorer cognitive functioning than older men [74], and older women of 10 h or more sleep duration have the lowest cognition compared to women and men in other sleep durations [80]. It is thus possible that more frequent FVI may help women with long sleep durations reduce the risk of cognitive decline. On the other hand, a sleep duration of greater than 8 h per day was associated with poorer memory function compared to the sleep duration of 7–8 h in older men, whereas there was no such relationship in older women [56]. One study shows that a sleep duration of 10 h or more was associated with elevated mortality in older men, but it was not the case in older women [87]. These findings may imply that the reduction in higher odds of cognitive impairment by frequent FVI could be smaller in older men than in older women if both of them have a long sleep duration.

As cognitive function declines sharply at the oldest-old ages [54,113,114], deteriorations in the homeostatic process, circadian amplitude, and thalamocortical and corticocortical rhythms with age (including delta waves, sleep spindles, and slow oscillations) may be associated with effects of sleep on brain regions of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) that deteriorate with age [22,115,116,117,118]. It is thus possible that the effect of frequent FVI against the negative consequences of long or excessive sleep durations on cognitive impairment could be more prominent in the oldest-old adults. Given the limited amount of empirical research on the impact of the interaction between FVI and sleep on cognition in the oldest-old population, we encourage further studies to verify our findings and elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Finally, associations between sleep quality/duration, FVI, and incidence of cognitive impairment were relatively weak, and the interactions between sleep quality/duration and FVI on cognitive impairment were mostly absent, which may imply that the influence of sleep and FVI on cognitive function is likely cumulative or concurrent. The underlying causes for the weak short-term longitudinal associations of sleep quality/duration and FVI with cognitive impairment may be difficult to detect and disentangle, but the following possibilities may provide some clues. Changes in sleep quality/duration and frequency of FVI over time are common [118,119,120]. These changes are closely linked with cognitive functioning, and only those who adhere to a normal sleep duration or a healthy diet (such as frequent FVI) have a lower risk of witnessing cognitive decline [118,119,120]. Thus, the sleep quality/duration and the frequency of FVI three years ago may not reflect the most recent status of sleep quality/duration and FVI, nor capture the information between survey intervals. Accordingly, the links between sleep quality/duration and FVI with cognitive impairment tend to be weak. Hence, the observed associations should be interpreted as concurrent correlations rather than causal links, especially given that cognitive deterioration can itself lead to altered sleep and dietary habits. We welcome more research to verify our findings.

4.1. Implications

Our findings have several important clinical, behavioral, and policy implications. First, this study provides novel evidence that fruit and/or vegetable intake (FVI) moderates the association between sleep and cognitive impairment among older adults, indicating that sleep-related cognitive decline can be mitigated through modifiable lifestyle factors such as diet. Public health practitioners should integrate sleep and nutrition screening when assessing cognitive risk, as poor sleep and insufficient FVI jointly heighten vulnerability to cognitive impairment [60,65]. Second, the buffering role of frequent FVI highlights opportunities for dual-behavioral interventions. Health promotion programs should encourage both regular sleep routines and frequent consumption of fruits and vegetables as complementary preventive strategies [121,122]. Such integrative approaches may be more feasible and sustainable than pharmacological treatments, especially in resource-limited settings. Third, subgroup analyses suggest targeted interventions. The stronger protective effects of frequent FVI among women and the oldest-old indicate that tailored dietary or lifestyle programs could be particularly effective in these groups, who are more vulnerable to sleep disturbances and nutritional deficits. Rural initiatives may also require attention to affordability and access to fresh produce. Fourth, cognitive health promotion should move beyond single-factor interventions toward integrated models combining sleep hygiene, dietary quality, and psychosocial support. Community-based programs linking primary care, nutrition education, and sleep management could help older adults maintain both healthy sleep and diet patterns. Finally, the moderating role of FVI provides mechanistic insights for future research. Studies on how bioactive nutrients interact with circadian and neuroinflammatory pathways could inform biologically grounded, culturally specific guidelines for promoting cognitive health and healthy aging in China.

4.2. Limitations

When interpreting our findings, the following shortcomings should be taken into account. First, similar to most epidemiological studies, information on the sleep duration in the CLHLS was obtained from a self-reported single-item measure that used hourly categories as a response for the sake of a lower cost and ease of administration. Thus, recall errors cannot be fully excluded [122]. Nevertheless, such biases should not be substantial, as several prior validation studies have found that the self-reported sleep duration is usually well compared with sleep durations based on polysomnography or actigraphy [123]. Second, the information on respondents’ sleep duration in the CLHLS did not explicitly ask participants to differentiate daytime napping from nighttime sleep hours. Studies have shown that sleep patterns of daytime napping may be different from those of sleep overnight and may have independent and different effects on cognitive functioning [27]. However, some empirical evidence has suggested that daytime napping and nocturnal sleep may share similar mechanisms underlying their associations with cognitive functioning [124]; it may not be a serious issue to apply the overall daytime and nighttime combined sleep duration in research. Third, FVI was frequency-based rather than quantitative-based, which may underestimate true intake variation [122]. Fourth, reverse causality remains a concern, since cognitive impairment may alter sleep and dietary patterns. Fifth, information about sleep quality and duration, and cognitive function could be distorted by the use of medication and caffeine [125,126,127] as well as by depression, physical activity intensity [128,129]. Due to the limited availability of these data, we are not able to detect their impacts. Fortunately, according to some other Chinese studies, the proportions of older adults on medication for sleep and cognitive impairment are very small (3–7%) [84,130]. Last but not least, due to the complexity and dynamics between sleep patterns and cognitive function, we are not able to disentangle whether sleep altered the risk of cognitive impairment or whether different cognitive performance resulted in the variation in sleep. We welcome more research to shed light on this issue. Despite these limitations, our sensitivity analyses yielded consistent findings, suggesting the robustness of the main results.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that good sleep quality, normal sleep duration, and frequent fruit and vegetable intake are independently associated with better cognitive function among older Chinese adults. Moreover, FVI moderates the negative association of poor or abnormal sleep with cognition. However, given the weak longitudinal associations, these findings should be interpreted as concurrent rather than causal. Promoting both healthy sleep and regular fruit and vegetable consumption may serve as practical, low-cost strategies to maintain cognitive health in later life. Future longitudinal and experimental studies are needed to verify causal pathways and to explore culturally specific dietary–sleep interventions in aging societies.

Author Contributions

C.B. and Y.X. contributed equally. C.B. drafted the manuscript, interpreted the results, and co-designed the research. Y.X. prepared data, performed the analyses, and drafted the methods and results. D.G. designed, drafted some parts of the manuscript, and revised the entire paper. D.G. also supervised the data analysis and is responsible for the accuracy of the results. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

C.B.’s work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72104240) and the Scientific Research Foundation of Renmin University of China (No. 21XNA013).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable as this research uses a publicly available dataset, the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS).

Data Availability Statement

The Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS) was jointly implemented by the Aging Center of Duke University and the Center for Healthy Aging and Family Studies (CHAFS), Peking University. The datasets and questionnaires are publicly available at https://opendata.pku.edu.cn/dataverse/CHADS (accessed on 22 December 2025), or at https://opendata.pku.edu.cn/dataverse/CHADS;jsessionid=25593b460dfee1fd7a1662a53260 (accessed on 22 December 2025). We obtained permission to use this dataset.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

FVI: Fruit and/or Vegetable Intake; CLHLS: Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; ORs: Odds Ratios; SD: Standard Deviation; CI: Confidence Interval.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sample distributions of study variables, CLHLS 2005–2018.

Table A1.

Sample distributions of study variables, CLHLS 2005–2018.

| Characteristics | Total | Characteristics | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sample (person-interviews) | 64,690 | Family/Social Connections | |

| % Currently married | 66.6 | ||

| Sleep | Average number of living children | 3.0 | |

| % Good sleep quality | 60.3 | % Co-resident with family member(s) | 86.3 |

| % ≤6 h of sleep | 34.0 | Health Practice | |

| % 7–9 h of sleep | 51.5 | % Frequent eat meats | 32.6 |

| % ≥10 h of sleep | 14.5 | % Frequent eat finish | 12.1 |

| Fruit and/or Vegetable Intake | % Frequent drink tea | 29.4 | |

| % Frequent FVI a | 78.3 | % Smoking at present | 23.2 |

| Outcome Variable | % Alcoholic drinking at present | 19.7 | |

| % Cognitively impaired | 2.5 | % Performing regular exercise | 43.2 |

| Demographic Variables | Health conditions | ||

| Mean age (years) | 73.1 (6.5) | % ADL disabled | 9.3 |

| % Aged 80 or older | 68.9 | % Self-rated poor health | 15.6 |

| % Men | 47.8 | % Reporting 1 + chronic conditions | 64.7 |

| % Han ethnicity | 96.2 | Waves | |

| % Urban | 46.5 | 2005 | 16.8 |

| Socioeconomic Status | 2008 | 18.0 | |

| % Having 1 + years of schooling | 70.7 | 2011 | 19.9 |

| % Good family income | 17.3 | 2014 | 20.6 |

| % Adequate medical access | 95.0 | 2018 | 24.8 |

Notes: (1) All variables are measured from all 64,690 person-interviews (observations) from 31,176 respondents who participated in five waves in 2005, 2008, 2011, 2014, and 2018. All percentages or means were weighted. (2) a, frequent fruit and vegetable intake (FVI) refers to eating fruits and vegetables almost every day. (3) “ADL disabled” refers to needing assistance in performing any of the six activities of daily living (bathing/showering, dressing, toileting, indoor moving, eating, and continence). (4) age and the number of children alive are measured in mean, whereas all other variables are measured in percentage.

Table A2.

Sensitivity analyses of odds ratios of the prevalence of cognitive impairment for sleep quality, sleep duration, and fruit and vegetable intake under different scenarios in terms of different sample sizes, whether applying the sampling weight, and different categorizations of sleep durations, CLHLS, 2005–2018.

Table A2.

Sensitivity analyses of odds ratios of the prevalence of cognitive impairment for sleep quality, sleep duration, and fruit and vegetable intake under different scenarios in terms of different sample sizes, whether applying the sampling weight, and different categorizations of sleep durations, CLHLS, 2005–2018.

| Model III | Model IV | |

|---|---|---|

| Currently Used (N = 64,690) | ||

| Sleep quality | ||

| Good (fair/poor) | 0.67 *** | 0.78 *** |

| Sleep duration | ||

| ≤6 h (7–9 h) | 1.08 * | 1.05 |

| ≥10 h (7–9 h) | 1.43 *** | 1.24 *** |

| Fruit and/or vegetable intake (FVI) | ||

| Frequent (no) | 0.67 *** | 0.69 *** |

| Missing Values in Cognition Excluded (N = 52,400) | ||

| Sleep quality | ||

| Good (fair/poor) | 0.73 *** | 0.83 *** |

| Sleep duration | ||

| ≤6 h (7–9 h) | 1.10 * | 1.05 |

| ≥10 h (7–9 h) | 1.36 *** | 1.21 *** |

| Fruit and/or vegetable intake (FVI) | ||

| Frequent (no) | 0.64 *** | 0.66 *** |

| Unable to Answer as “Wrong” (N = 64,690) | ||

| Sleep quality | ||

| Good (fair/poor) | 0.68 *** | 0.79 *** |

| Sleep duration | ||

| ≤6 h (7–9 h) | 1.00 | 0.96 |

| ≥10 h (7–9 h) | 1.80 *** | 1.56 *** |

| Fruit and/or vegetable intake (FVI) | ||

| Frequent (no) | 0.66 *** | 0.68 *** |

| Weighted (Population Average Model) (N = 64,690) | ||

| Sleep quality | ||

| Good (fair/poor) | 0.70 *** | 0.80 *** |

| Sleep duration | ||

| ≤6 h (7–9 h) | 0.88 + | 0.86 + |

| ≥10 h (7–9 h) | 1.59 *** | 1.34 *** |

| Fruit and/or vegetable intake (FVI) | ||

| Frequent (no) | 0.67 *** | 0.73 *** |

| A Different Sleep Duration Classification (N = 64,690) | ||

| Sleep quality | ||

| Good (fair/poor) | 0.68 *** | 0.79 *** |

| Sleep duration | ||

| ≤6 h (8 h) | 1.12 * | 1.09 + |

| 7 h | 1.07 | 1.10 + |

| 9 h | 1.06 | 1.07 |

| ≥10 h (8 h) | 1.48 *** | 1.29 *** |

| Fruit and/or vegetable intake (FVI) | ||

| Frequent (no) | 0.67 *** | 0.69 *** |

Notes: (1) Model results were obtained from -xtlogit- in Stata v17 by adjusting for intrapersonal correlation. rho refers to the intrapersonal correlation coefficient. Model III controlled demographics, socioeconomic status, family/social support, and health practice. Model IV added health conditions to Model III. The comparisons for Models I to II (not shown) are more or less the same as those presented in the table. Odds ratios for all covariates are not displayed. (2) Frequent fruit and/or vegetable intake (FVI) refers to eating fruits and/or vegetables almost every day. Disability in activities of daily living (ADLs) refers to needing assistance in performing any of the six activities of daily living (bathing/showering, dressing, toileting, indoor moving, eating, and continence). (3) Cognitive impairment is defined when an MMSE score is less than 18 for the respondents with 0–3 years of schooling, MMSE score < 21 for the respondents with 4–6 years of schooling, or MMSE score < 24 for the respondents with 7+ years of schooling. (4) The category in the parentheses of a variable is the reference group of that variable. (5) +, p < 0.1; *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001.

Figure A1.

Structure of CLHLS sample by wave and first interview year, 2005–2018. Notes: Blue bold font refers to alive respondents at a given wave; red italic font refers to those deceased who died between a given wave and its previous wave; and normal black font refers to those lost to follow-up.

References

- Prince, M.; Bryce, R.; Albanese, E.; Wimo, A.; Ribeiro, W.; Ferri, C.P. The global prevalence of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2013, 9, 63–75.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M.; Comas-Herrera, A.; Knapp, M.; Guerchet, M.; Karagiannidou, M. World Alzheimer Report 2016. Improving Healthcare for People with Dementia: Coverage Quality and Costs Now and in the Future. Alzheimer’ s Disease International. 2016. Available online: https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2016.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Rashmita, B. Dementia caregiving, care recipient health, and financial burdens. Innov. Aging 2020, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia 2017–2025. 2017. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259615 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Prince, M.; Wimo, A.; Guerchet, M.; Ali, G.C.; Prina, M. World Alzheimer Report 2015. The Global Impact of Dementia: An Analysis of Prevalence, Incidence, Cost and Trends. Alzheimer’s Disease International. 2015. Available online: https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- WHO. Risk Reduction of Cognitive Decline and Dementia-WHO Guidelines. 2019. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/312180/9789241550543-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Frankish, H.; Horton, R. Prevention and management of dementia: A priority for public health. Lancet 2017, 390, 2614–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Sommerlad, A.; Orgeta, V.; Costafreda, S.G.; Mukadam, N. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 2017, 390, 2673–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgin, E. Deprivation: A wake-up call. Nature 2013, 497, S6–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallit, S.; Hajj, A.; Sacre, H.; Karaki, G.A.; Malaeb, D.; Kheir, N.; Salameh, P.; Hallit, R. Impact of sleep disorders and other factors on the quality of life in general population: A cross-sectional study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2019, 207, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancoli-Israel, S.; Martin, J.L. Insomnia and daytime napping in older adults. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2006, 2, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.V.; Montazar, E.; Rezaei, S.; Hosseini, S.P. Sleep quality and cognitive function in the elderly population. J. Sleep Res. 2020, 5, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakakubo, S.; Makizako, H.; Doi, T.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Hotta, R.; Bae, S.; Suzuki, T.; Shimada, H. Impact of poor sleep quality and physical inactivity on cognitive function in community-dwelling older adults. Geriatr. Gerontol. Inter-Natl. 2017, 17, 1823–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, C.; Zöllig, J.; Allemand, M.; Martin, M. Sleep quality and cognitive function in healthy old age: The moderating role of subclinical depression. Neuropsychology 2012, 26, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Li, J.; Lian, Z. Both short and long sleep durations are associated with cognitive impairment among communi-ty-dwelling Chinese older adults. Medicine 2020, 99, e19667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazar, G.; María Leiva, A.; Troncoso, C.; Martínez, A.; Petermann-Rocha, F.; Villagrán, M.; Mardones, L.; Martorell, M.; María Labraña, A.; Ulloa, N.; et al. Association between sleep duration and cognitive impairment in older people. Rev. Med. Chile 2019, 147, 1398–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Fan, H.; Zhang, X.; Ji, C.; Xia, Y. Changes in sleep duration and 3-year risk of mild cognitive impairment in Chinese older adults. Aging 2020, 11, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, N.; Terpening, Z.; Rogers, N.L.; Duffy, S.L.; Hickie, I.B.; Lewis, S.J.G.; Naismith, S.L. Napping in older people ‘at risk’ of dementia: Relationships with depression, cognition, medical burden and sleep quality. J. Sleep Res. 2015, 24, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y.; Redline, S.; Stone, K.L.; Ancoli-Israel, S.; Yaffe, K. Objective napping, cognitive decline, and risk of cognitive impairment in older men. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2019, 15, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohayon, M.M.; Vecchierini, M.F. Daytime sleepiness and cognitive impairment in the elderly population. Arch. Intern. Med. 2002, 162, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohayon, M.M.; Vecchierini, M.F. Normative sleep data, cognitive function and daily living activities in older adults in the community. Sleep 2005, 28, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tworoger, S.S.; Lee, S.; Schernhammer, E.S.; Grodstein, F. The association of self-reported sleep duration, difficulty sleeping, and snoring with cognitive function in older women. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2006, 20, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronholm, E.; Sallinen, M.; Suutama, T.; Sulkava, R.; Era, P.; Partonen, T. Self-reported sleep duration and cognitive functioning in the general population. J. Sleep Res. 2010, 18, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmutte, T.; Harris, S.; Levin, R.; Zweig, R.; Katz, M.; Lipton, R. The relation between cognitive functioning and self-reported sleep complaints in nondemented older adults: Results from the Bronx Aging Study. Behav. Sleep Med. 2007, 5, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauble, R.; López-Gracía, E.; Guallar-Castillón, P.; Graciani, A.; Banegas, J.R.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. Usual sleep duration and cognitive function in older adults in Spain. J. Sleep Res. 2009, 18, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.R.; Dong, C.; Elkind, M.S.V.; Boden-Albala, B.; Sacco, R.L.; Rundek, T.; Wright, C.B. Association between sleep duration and the Mini-Mental Score: The Northern Manhattan Study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2013, 9, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Sun, D.; Tan, Y. A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of sleep duration and the occurrence of cognitive disorders. Sleep Breath. 2018, 22, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Jiang, C.; Hing, L.; Liu, B.; Jin, Y.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, K.; Thomas, G.N. Short or long sleep duration is associated with memory impairment in older Chinese: The Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. Sleep 2011, 34, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luik, A.I.; Zuurbier, L.A.; Hofman, A.; Someren, E.V.; Ikram, M.A.; Tiemeier, H. Associations of the 24-hour activity rhythm and sleep with cognition: A population-based study of middle-aged and elderly persons. Sleep Med. 2015, 16, 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devore, E.E.; Grodstein, F.; Duffy, J.F.; Stampfer, M.J.; Czeisler, C.A.; Schernhammer, E.S. Sleep duration in midlife and later life in relation to cognition. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keage, H.A.D.; Banks, S.; Yang, K.L.; Morgan, K.; Brayne, C.; Matthews, F.E. What sleep characteristics predict cognitive decline in the elderly? Sleep Med. 2012, 13, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin, O.; Lorrain, D.; Dubé, M.; Grenier, S.; Préville, M.; Hudon, C. Sleep quality and 1-year incident cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults. Sleep 2012, 35, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Lee, Y.H.; Chang, Y.; Shelley, M. Associations of dietary habits and sleep in older adults: A 9-year follow-up cohort study. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 12, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Chang, Y.; Lee, Y.T.; Shelley, M.; Liu, C. Dietary patterns with fresh fruits and vegetables consumption and quality of sleep among older adults in mainland China. Sleep Biol. Rhythm. 2018, 16, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorwali, E.; Hardie, L.; Cade, J. Bridging the reciprocal gap between sleep and fruit and vegetable consumption: A review of the evidence, potential mechanisms, implications, and directions for future work. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peuhkuri, K.; Sihvola, N.; Korpela, R. Diet promotes sleep duration and quality. Nutr. Res. 2012, 32, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, M.; Blomhoff, R.; Holme, I.; Tonstad, S. The effect of an increased intake of vegetables and fruit on weight loss, blood pressure and antioxidant defense in subjects with sleep related breathing disorders. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 61, 1301–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Shi, T.; Li, Q.; Chen, H.; Liu, M.; Lu, Y.; He, Q.; Chen, R. Associations of sleep duration and fruit and vegetable intake with the risk of metabolic syndrome in Chinese adults. Medicine 2021, 100, e24600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noorwali, E.; Hardie, L.; Cade, J. Fruit and vegetable consumption and their polyphenol content are inversely associated with sleep duration: Prospective associations from the UK women’s cohort study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltzer, K.; Pengpid, S. Self-reported sleep duration and its correlates with sociodemographics, health behaviours, poor mental health, and chronic conditions in rural persons 40 years and older in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottaghi, T.; Amirabdollahian, F.; Haghighatdoost, F. Fruit and vegetable intake and cognitive impairment: A systematic re-view and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicklett, E.J.; Kadell, A.R. Fruit and vegetable intake among older adults: A scoping review. Maturitas 2013, 75, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaynor, A.M.; Varangis, E.; Song, S.; Gazes, Y.; Noofoory, D.; Babukutty, R.S.; Habeck, C.; Stern, Y.; Gu, Y. Diet moderates the effect of resting state func-tional connectivity on cognitive function. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Cao, L.; Shi, M.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, Y. Fruit and vegetable consumption and cognitive disorders in older adults: A meta-Analysis of observational studies. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 871061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlich, K.H.; Beller, J.; Lange-Asschenfeldt, B.; Köcher, W.; Meinke, M.C.; Lademann, J. Consumption of fruits and vegetables: Improved physical health, mental health, physical functioning and cognitive health in older adults from 11 European countries. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistollato, F.; Cano, S.S.; Elio, I.; Vergara, M.M.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M.; Sumalla Cano, S.; Masias Vergara, M. Associations between sleep, cortisol regulation, and diet: Possible implications for the risk of Alzheimer disease. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSorley, V.E.; Bin, Y.S.; Lauderdale, D.S. Associations of sleep characteristics with cognitive function and decline among older adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 188, 1066–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Sun, N.; Kondracki, A.; Sun, W. Sex, sleep duration, and the association of cognition: Findings from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, J.; Yu, C.; Fang, W.; Xie, Y.; Wang, L.; Shen, S.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, L.; Wang, T.; et al. Sex modified the association between sleep duration and worse cognitive performance in Chinese hypertensive population: Insight from the China H-Type Hypertension Registry Study. Behav. Neurol. 2022, 22, 7566033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.C.; Moon, C.; Whitaker, K.M.; Zhang, D.; Carr, L.J.; Bao, W.; Xiao, Q. Cross-sectional and prospective associations between self-reported sleep characteristics and cognitive function in men and women: The Midlife in the United States Study. J. Sleep Res. 2022, 31, e13515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, S.S.Y.; Kowk, T.; Woo, J. Higher fruit and vegetable variety associated with lower risk of cognitive impairment in Chinese community-dwelling older men: A 4-year cohort study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 1791–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, V.F.; Barbosa, A.R.; D’Orsi, E. Cognition and indicators of dietary habits in older adults from southern Brazil. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goncalves, N.G.; Bertola, L.; Ferri, C.P.; Suemoto, C.K. Rural-urban disparities in the consumption of fruits and vegetables and cognitive performance in Brazil. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2023, 45, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murman, D.L. The impact of age on cognition. Semin. Hear. 2015, 36, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Quan, M.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Li, Y.; Wei, C.; Tang, Y.; Qin, Q.; Wang, F.; Qiao, Y.; et al. Dementia in China: Epidemiology, clinical management, and research advances. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maree, S.B.C.; Mario, S. Determining risk of dementia: A look at China and beyond. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 427–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Feng, Q.; Dupre, M.E.; Guo, A.; Qiu, L.; Hao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, D. Objective and subjective financial status and mortality among older adults in China. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 81, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Xiao, R.; Cai, C.; Xu, Z.; Wang, S.; Pan, L.; Yuan, L. Diet, lifestyle and cognitive function in old Chinese adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 63, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Feng, Q.; Chen, H.; Zeng, Y. Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Study. In Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging; Gu, D., Dupre, M.E., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 957–970. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, M.; Huang, Z.; Deng, Q.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L. Vegetable and fruit consumption among Chinese adults and associated factors: A nationally representative study of 170,847 adults. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2017, 30, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Yang, B.; Liao, Y.; Gao, G.; Richmond, C.J. Sleep disturbance in older adults with or without mild cognitive impairment and its associated factors residing in rural area, China. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2020, 34, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wei, S.; Liang, Y. Association between sleep–wake habits and use of health care services of middle-aged and elderly adults in China. Aging 2020, 12, 3926–3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Li, F.; Chen, X.; He, F.; Zhai, Y.; Pan, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Yu, M. Association of postlunch napping duration and night-time sleep duration with cognitive impairment in Chinese elderly: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e023188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Q.; Liu, X.; Hu, W.; Han, X.; Zhou, W.; Lu, A.; Wang, X.; Wu, S. Night sleep duration and risk of cognitive impairment in a Chinese population: A cross-sectional study. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2017, 30, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, R.; Liu, G.; Khan, N.; Yan, H.; Wang, Y. Dietary habits and cognitive impairment risk among oldest-old Chinese. J. Gerontol. Soc. Sci. 2019, 74, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, H.G. Lower intake of vegetables and legumes associated with cognitive decline among illiterate elderly Chinese: A 3-year cohort study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2012, 16, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.T.C.; Richards, M.; Chan, W.C.; Chiu, H.F.; Lee, R.S.; Lam, L.C. Lower risk of incident dementia among Chinese older adults having three servings of vegetables and two servings of fruits a day. Age Ageing 2017, 46, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Brown, B.L.; Qiu, L. Self-perceived uselessness is associated with lower likelihood of successful aging among older adults in China. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Gu, D. Reliability of age reporting among the Chinese oldest-old in the CLHLS datasets. In Healthy Longevity in China: Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Psychological Dimensions; Zeng, Y., Poston, D.L., Vlosky, D.A., Gu, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2008; pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, Z.; Hidajat, M.; Saito, Y. Changes in total and disability-free life ex-pectancy among older adults in China: Do they portend a compression of morbidity? Int. J. Popul. Stud. 2015, 1, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sautter, J.M.; Qiu, L.; Gu, D. Self-perceived uselessness and associated factors among older adults in China. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.; Liu, W.; Levy, P.; Zhang, M.; Katzman, R.; Lung, C.T.; Wong, S.; Wang, Z.; Qu, G. Cognitive impairment among elderly adults in Shanghai, China. J. Gerontol. 1989, 44, S97–S106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; Mchugh, P.R. “Mini-Mental State”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z. Gender differentials in cognitive impairment and decline of the oldest old in China. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2006, 61, S107–S115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Gu, D. Predictors of loneliness incidence in Chinese older adults from a life course perspective: A national longitu-dinal study. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jia, J.; Yang, Z. Mini-Mental State Examination in elderly Chinese: A population-based normative study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016, 53, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Yue, B.; Li, S.; Liu, Q.; Li, Q.; Li, L.; Sun, J. Association of changes in self-reported sleep duration with mild cognitive impairment in the elderly: A longitudinal study. Aging 2021, 13, 14816–14828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Chen, H.S.; Ni, T.; Ruan, R.P.; Feng, L.; Nie, C.; Cheng, L.G.; Li, Y.; Tao, W.; Gu, J. Gxe interactions between FOXO genotypes and tea drinking are significantly associated with cognitive disability at advanced ages in China. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2015, 70, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.C.; Gao, X.; Yu, Y.B.; Zhou, J.H.; Wei, Y.; Yin, Z.X.; Ma, J.X.; Mao, C.; Shi, X.M. Alcohol cessation in late life is associated with lower risk of cognitive impairment among the older adults in China. Biomed. Enviorn. Sci. 2021, 34, 500–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Sautter, J.; Pipkin, R.; Zeng, Y. Sociodemographic and health correlates of sleep quality and duration among very old Chinese. Sleep 2010, 33, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, P.D. Missing Data; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, D. General Data Quality Assessment of the CLHLS. In Healthy Longevity in China: Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Psychological Dimensions; Zeng, Y., Poston, D.L., Vlosky, D.A., Gu, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2008; pp. 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, M.; Simos, P.; Vgontzas, A.; Koutentaki, E.; Tziraki, S.; Zaganas, I.; Panagiotakis, S.; Kapetanaki, S.; Fountoulakis, N.; Lionis, C. Associations between sleep duration and cognitive impairment in mild cognitive impairment. J. Sleep Res. 2019, 28, e12864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallicchio, L.; Kalesan, B. Sleep duration and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sleep Res. 2009, 18, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Sautter, J.M.; Liu, Y.; Gu, D. Age and gender differentials in association between sleep and mortality among very old Chinese. Sleep Med. 2011, 12, 1008–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek-Ahmadi, M.; Kora, K.; O’Connor, K.; Schofield, S.; Coon, D.; Nieri, W. Longer self-reported sleep duration is associated with decreased performance on the Montreal cognitive assessment in older adults. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 28, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Liu, G.; Sun, Y.; Gu, D.; Zhang, H.; Yang, H.; Lu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, Y. Association between household fuel use and sleep quality in the oldest-old: Evidence from a propensity-score matched case-control study in Hainan, China. Environ. Res. 2020, 191, 110229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aihemaitijiang, S.; Zhang, L.; Ye, C.; Halimulati, M.; Huang, X.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Z. Long-term high dietary diversity maintains good physical function in Chinese elderly: A cohort study based on CLHLS from 2011 to 2018. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winship, C.; Radbill, L. Sampling weights and regression analysis. Sociol. Methods Res. 1994, 23, 230–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, J.C.; Groeger, J.A.; Cheng, G.; Dijk, D.J.; Chee, M.W.L. Self-reported sleep duration and cognitive performance in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2016, 17, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Cheng, H.; Sheng, L.; Feng, L.; Yuan, J.; Michael, C.; Pan, A.; Woon-Puay, K. Prospective associations between change in sleep duration and cognitive impairment: Findings from the Singapore Chinese Health Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 281, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhan, G.; Fenik, P.; Panossian, L.; Wang, M.; Reid, S.; Lai, D.; Davis, J.G.; Baur, J.A. Extended wakefulness: Com-promised metabolics in and degeneration of locus ceruleus neurons. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 4418–4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Qu, L.; Liu, H. Non-linear associations between sleep duration and the risks of mild cognitive impairment/dementia and cognitive decline: A dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 31, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, R.; Miyano, I.; Lee, S.; Shimada, H.; Kitaoka, H. Association between self-reported night sleep duration and cognitive function among older adults with intact global cognition. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 36, 766–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satizabal, C.L.; Zhu, Y.C.; Mazoyer, B.; Dufouil, C.; Tzourio, C. Circulating IL-6 and CRP are associated with MRI findings in the elderly: The 3C-Dijon Study. Neurology 2012, 78, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liang, L.; Zheng, F.; Shi, L.; Zhong, B.; Xie, W. Association between sleep duration and cognitive decline. J. Am. Med. Assoc. Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2013573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaffe, K.; Falvey, C.M.; Hoang, T. Connections between sleep and cognition in older adults. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.R.; Zhu, X.; Storfer-Isser, A.; Mehra, R.; Jenny, N.S.; Russell, T.; Redline, S. Sleep duration and biomarkers of inflammation. Sleep 2009, 32, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappuccio, F.P.; Cooper, D.; Delia, L.; Strazzullo, P.; Miller, M.A. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 1484–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Sun, D.; Tan, Y. Intake of fruit and vegetables and the incident risk of cognitive disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2017, 21, 1284–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Panicka, K.S. Dietary and plant polyphenols exert neuroprotective effects and improve cognitive function in Cerebral Ischemia. Recent Pat. Food Nutr. Agric. 2013, 5, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, M.; Rahardjo, T.B.W.; Soekardi, R.; Sulistyowati, Y.; Hogervorst, E. Phytoestrogens and cognitive function: A review. Maturitas 2014, 77, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaw, J.T.J.; Howe, P.R.C.; Wong, R.H.X. Does phytoestrogen supplementation improve cognition in humans? A systematic review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1403, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Fondell, E.; Bhushan, A.; Ascherio, A.; Willett, W.C. Long-term intake of vegetables and fruits and subjective cognitive function in US men. Neurology 2018, 92, e63–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.E.; Lim, M.M.; Bateman, R.J.; Lee, J.J.; Smyth, L.P.; Cirrito, J.R.; Fujiki, N.; Nishino, S.; Holtzman, D.M. Amyloid-beta dynamics are regulated by orexin and the sleep-wake cycle. Science 2009, 326, 1005–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroczko, B.; Groblewska, M.; Litman-Zawadzka, A. The role of protein misfolding and tau oligomers (TauOs) in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauglund, N.L.; Pavan, C.; Nedergaard, M. Cleaning the sleeping brain-the potential restorative function of the glymphatic system. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2020, 15, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C.R.; Ysbrand, D. The sleeping brain: Harnessing the power of the glymphatic system through lifestyle choices. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gildner, T.E.; Salinas-Rodríguez, A.; Manrique-Espinoza, B.; Moreno-Tamayo, K.; Kowal, P. Does poor sleep impair cognition during aging? Longitudinal associations between changes in sleep duration and cognitive performance among older Mex-ican adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 83, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, E.C.; She, R.; Rukstalis, M.; Alexander, G.L. Changes in fruit and vegetable consumption in relation to changes in sleep characteristics over a 3-month period among young adults. Sleep Health 2021, 7, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Woods, R.L.; Wolfe, R.; Storey, E.; Chong, T.T.J.; Shah, R.C.; Orchard, S.G.; McNeil, J.J.; Murray, A.M.; Ryan, J.; et al. Trajectories of cognitive function in community-dwelling older adults: A longitudinal study of population heterogeneity. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 13, e12180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Feng, Q.; Hesketh, T.; Christensen, K.; Vaupel, J. Improvements in survival and activities of daily living despite declines in physical and cognitive functioning among the oldest-old in China—Evidence from a cohort study. Lancet 2017, 389, 1619–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cajochen, C.; Munch, M.; Knoblauch, V.; Blatter, K.; Wirz-Justice, A. Age-related changes in the circadian and homeostatic regulation of human sleep. Chronobiol. Int. 2006, 23, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, L.; Born, J. The contribution of sleep to hippocampus-dependent memory consolidation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2007, 11, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mander, B.A.; Rao, V.; Lu, B.; Aletin, J.M.; Lindquist, J.R.; Ancoli-Israel, S.; Jagust, W.; Walker, M.P. Prefrontal atrophy, disrupted NREM slow waves and impaired hippocampal-dependent memory in aging. Nat. Neurosci. 2013, 16, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrie, J.E.; Shipley, M.J.; Akbaraly, T.N.; Marmot, M.G.; Kivimäki, M.; Singh-Manoux, A. Change in sleep duration and cognitive function: Findings from the Whitehall II Study. Sleep 2011, 34, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jia, C.-X. Sleep duration change and cognitive function. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2020, 208, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Guo, J.; Moshfegh, A. Race/ethnicity and gender modify the association between diet and cognition in U.S. older adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2014. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 7, e12128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlich, K.H.; Beller, J.; Lange-Asschenfeldt, B.; Köcher, W.; Meinke, M.C.; Lademann, J. Fruit and vegetable consumption is as-sociated with improved mental and cognitive health in older adults from non-Western developing countries. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, R.; Xiang, X.; Liu, J.; Guan, C. Diet and self-rated health among oldest-old Chinese. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 76, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.R.; Ayas, N.T.; Malhotra, M.R.; White, D.P.; Schernhammer, E.S.; Speizer, F.E.; Stampfer, M.J.; Hu, F. A prospective study of sleep duration and mortality risk in women. Sleep 2004, 27, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Yang, H.; He, M.; Pan, A.; Li, X.; Min, X.; Zhang, C.; Xu, C.; Zhu, X.; Yuan, J. Longer sleep duration and midday napping are associated with a higher risk of CHD incidence in middle-aged and older Chinese: The Dongfeng-Tongji Cohort Study. Sleep 2016, 39, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolkove, N.; Elkholy, O.; Baltzan, M.; Palayew, M. Sleeping and aging: 1. Sleep disorders commonly found in older people. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2007, 176, 1299–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkove, N.; Elkholy, O.; Baltzan, M.; Palayew, M. Sleeping and aging: 2. Management of sleep disorders in older people. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2007, 176, 1449–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lin, D.; Sun, Y.; Wu, A.; Wei, C. Effect of dexmedetomidine on postoperative sleep quality: A systematic review. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021, 15, 2161–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Hou, R.; Xie, L.; Chandrasekar, E.K.; Lu, H.; Wang, T.; Li, C.; Xu, H. Sleep, sedentary activity, physical activity, and cognitive function among older adults: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2014. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2021, 24, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Hwang, G.; Cho, Y.H.; Kim, E.J.; Woang, J.W.; Hong, C.H.; Son, S.J.; Roh, H.W. Relationships of Physical Activity, Depression, and Sleep with Cognitive Function in Community Dwelling Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, L. Sleep habits and insomnia in a sample of elderly persons in China. Sleep 2005, 28, 1579–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.