Glycemic Responses, Enzyme Activity, and Sub-Acute Toxicity Evaluation of Unripe Plantain Peel Extract in Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Equipment

2.3. Acquisition of Plant Material and Extract Preparation

2.4. Phytochemical Screening

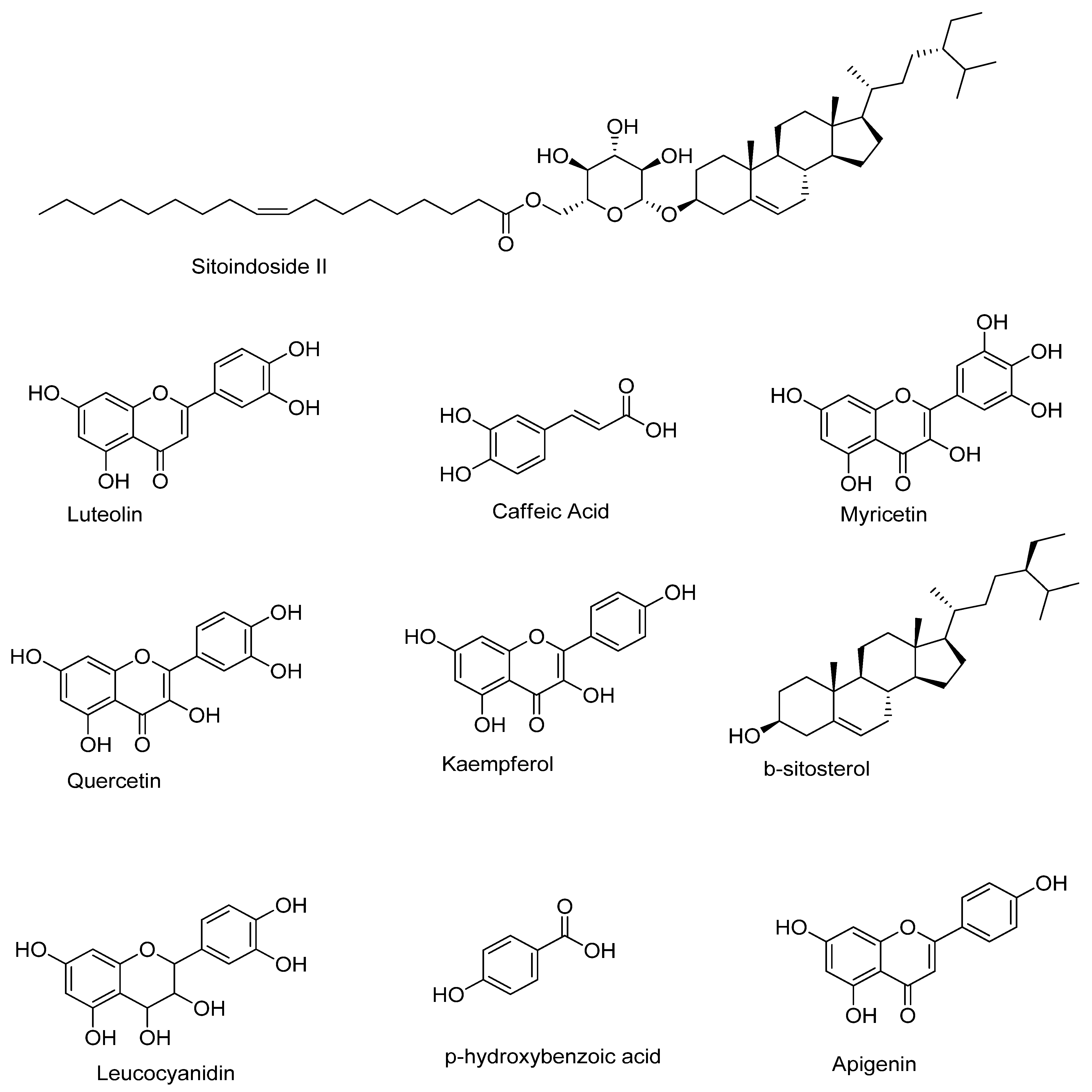

2.5. Quantification of Phytochemicals Using Gas Chromatography-Flame Ionization Detection (GC-FID)

2.6. Evaluation of In Vitro Antioxidant Contents and Potentials

2.6.1. Quantification of Total Phenol Content

2.6.2. Quantification of Total Flavonoid Content

2.6.3. Evaluation of Total Antioxidant Capacity

2.7. In Vitro Assessment of Carbohydrate-Digestive Enzyme Inhibition

2.7.1. Assay of α-Amylase Inhibition Potential

2.7.2. Assay of α-Glucosidase Inhibition Potential

2.8. Animals

2.9. Experimental Design

- Group I: Control; vehicle (distilled water, 1 mL/kg)

- Group II: 100 mg/kg Musa paradisiaca ethanol extract (MPE)

- Group III: 200 mg/kg MPE

- Group IV: 400 mg/kg MPE

2.10. Serum and Tissue Homogenates Preparation

2.11. Assessment of Serum Lipid Profile

2.12. Assessment of Tissue Function Indices

2.13. Assessment of Tissue Antioxidant Status

2.13.1. Quantification of Tissue Membrane Lipid Peroxidation

2.13.2. Assay of Reduced Glutathione (GSH)

2.13.3. Assay of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Activity

2.13.4. Assay of Glutathione Peroxidase Activity (GPx)

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Extract Yield, Phytochemicals and Antioxidant Potential of MPE

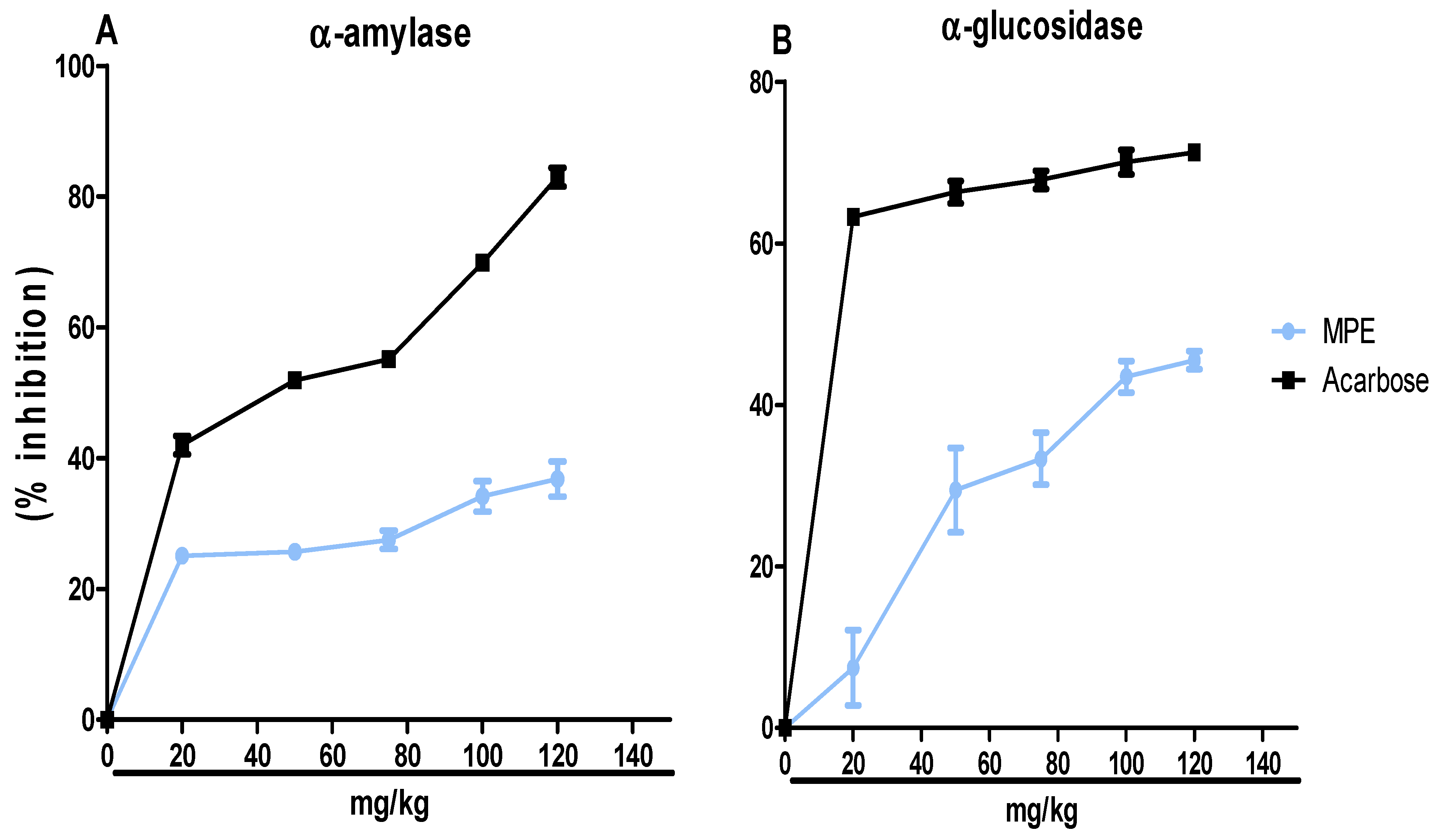

3.2. Inhibitory Effects of MPE on α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase

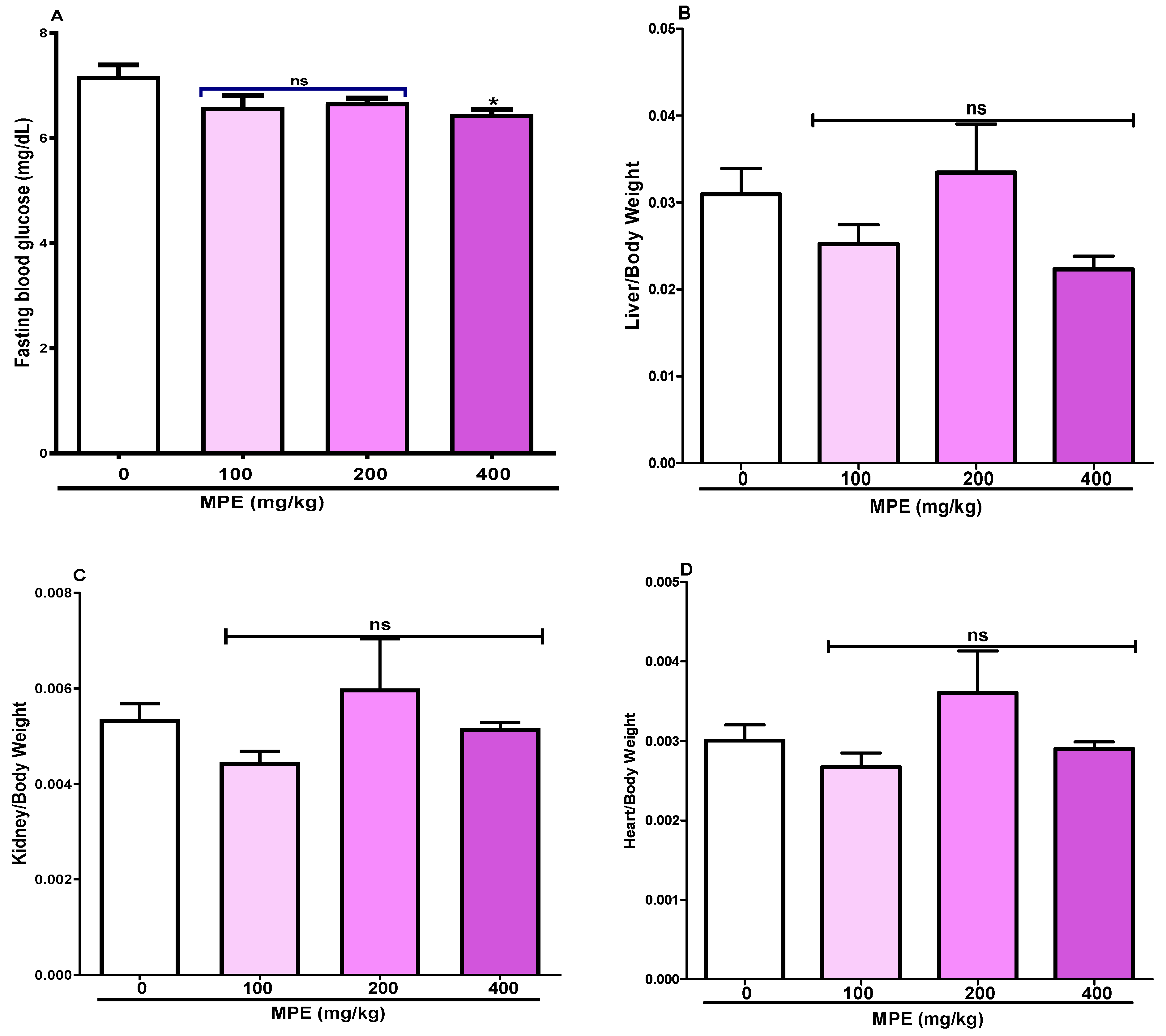

3.3. Fasting Blood Glucose Levels and Organ-to-Body-Weight Ratio

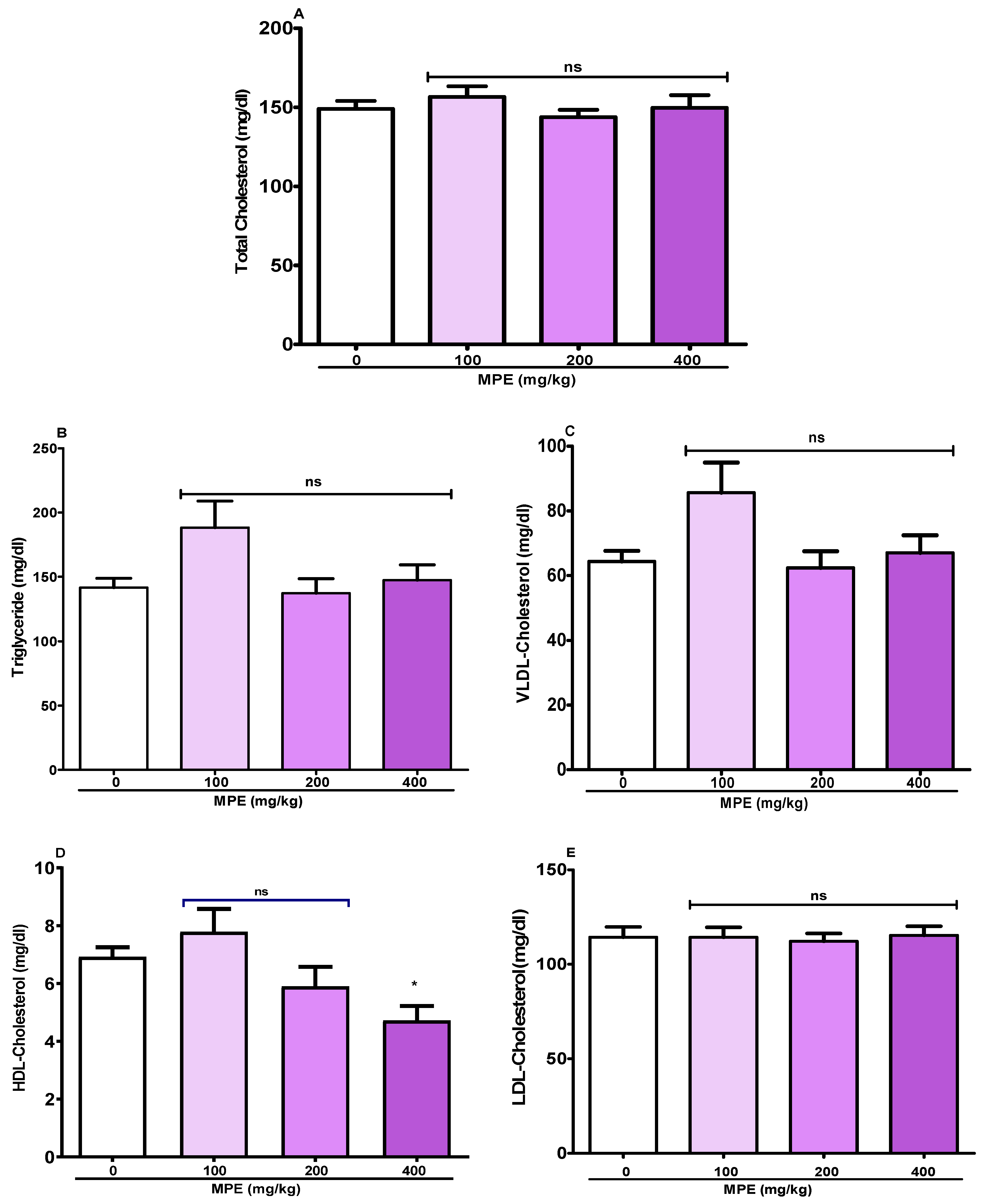

3.4. Serum Lipid Profile of Rats

3.5. Hepatic Function Indices

3.6. Renal and Cardiac Function Indices

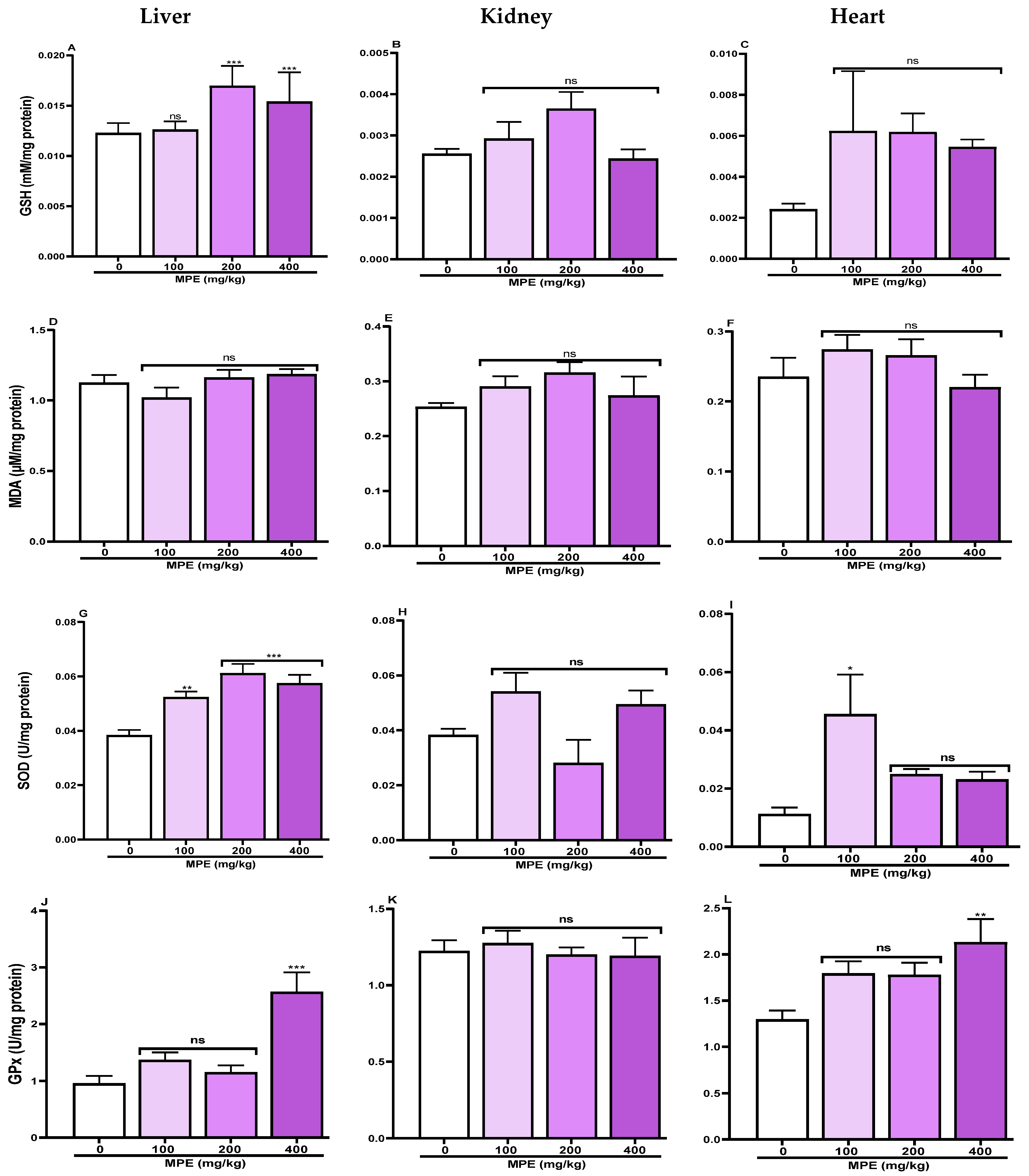

3.7. Tissues Oxidative Stress Profile

4. Discussion

4.1. Phytochemical Profile of Plantain Peel Extract

4.2. In Vitro Antioxidant and Glycemic Regulatory Activities

4.3. In Vivo Toxicological Evaluation

4.3.1. Effects on Body and Organ Weights

4.3.2. Impact on Lipid Profile and Cardiac Biomarkers

4.3.3. Hepatic and Renal Function Indices

4.3.4. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Status

4.3.5. Limitation and Translational Relevance

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olayeriju, O.S.; Olaleye, M.T.; Crown, O.O.; Komolafe, K.; Boligon, A.A.; Athayde, M.L.; Akindahunsi, A.A. Ethylacetate extract of red onion (Allium cepa L.) tunic affects hemodynamic parameters in rats. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2015, 4, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, M.; Ranić, M.; Gurinović, M. Underutilized plants increase biodiversity, improve food and nutrition security, reduce malnutrition, and enhance human health and well-being. Let’s put them back on the plate! Nutr. Rev. 2024, 82, 1111–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obidike, I.; Salawu, O. Screening of Herbal Medicines for Potential Toxicities, New Insights into Toxicity and Drug Testing. In New Insights into Toxicity and Drug Testing; Gowder, S., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Oyeyinka, B.O.; Afolayan, A.J. Comparative Evaluation of the Nutritive, Mineral, and Antinutritive Composition of Musa sinensis L. (Banana) and Musa paradisiaca L. (Plantain) Fruit Compartments. Plants 2019, 8, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmuga, S.C.; Subramanian, S. Musa Paradisiaca flower extract improves carbohydrate metabolism in hepatic tissues of streptozotocin-induced experimental diabetes in rats. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012, 2, S1498–S1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.; Maraschin, M. Banana (Musa spp.) from peel to pulp: Ethnopharmacology, source of bioactive compounds and its relevance for human health. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 160, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, M.W.; Gudimella, R.; Harikrishna, J.A.; Sin, L.W.; Khalid, N.; Keulemans, J. A draft Musa balbisiana genome sequence for molecular genetics in polyploid, inter- and intra-specific Musa hybrids. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsamo, C.V.P.; Herent, M.F.; Tomekpe, K.; Emaga, T.H.; Quetin-Leclercq, J.; Rogez, H.; Larondelle, Y.; Andre, C. Phenolic profiling in the pulp and peel of nine plantain cultivars (Musa sp.). Food Chem. 2015, 167, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Xiao, J.; Tu, S.; Sheng, Q.; Yi, G.; Wang, J.; Sheng, O. Plantain flour: A potential anti-obesity ingredient for intestinal flora regulation and improved hormone secretion. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 1027762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.Z.; Liu, I.M.; Cheng, J.T.; Lin, B.S.; Liu, F. Wound healing is promoted by Musa paradisiaca (banana) extract in diabetic rats. Arch. Med. Sci. AMS 2024, 20, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajijolakewu, K.A.; Ayoola, A.S.; Agbabiaka, T.O.; Zakariyah, F.R.; Ahmed, N.R.; Oyedele, O.J.; Sani, A. A review of the ethnomedicinal, antimicrobial, and phytochemical properties of Musa paradisiaca (plantain). Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2021, 45, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, H.S.; Kar, A. Medicinal values of fruit peels from Citrus sinensis, Punica granatum, and Musa paradisiaca with respect to alterations in tissue lipid peroxidation and serum concentration of glucose, insulin, and thyroid hormones. J. Med. Food 2008, 11, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, R.; Jan, S.U.; Faridullah, S.; Sherani, S.; Jahan, N. Preliminary Phytochemical Screening, Quantitative Analysis of Alkaloids, and Antioxidant Activity of Crude Plant Extracts from Ephedra intermedia Indigenous to Balochistan. Sci. World J. 2017, 2017, 5873648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, N.; Hussen, F.; Ali, A.A. Preliminary Phytochemical Screening, Quantitative Estimation of Total Flavonoids, Total Phenols and Antioxidant Activity of Ephedra alata Decne. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2015, 6, 1771–1778. [Google Scholar]

- Komolafe, K.; Akinmoladun, A.; Olaleye, M. Methanolic leaf extract of Parkia biglobosa protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats. Int. J. Appl. Res. Nat. Prod. 2013, 6, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Nwiloh, B.; Uwakwe, A.; Akaninwor, J. Phytochemical screening and GC-FID analysis of ethanolic extract of root bark of Salacianitida L. Benth. J. Med. Plant Stud. 2016, 4, 283–287. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; Volume 299, pp. 152–178. [Google Scholar]

- Dewanto, V.; Wu, X.; Adom, K.K.; Liu, R.H. Thermal Processing Enhances the Nutritional Value of Tomatoes by Increasing Total Antioxidant Activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3010–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. Ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay: Direct measure of total antioxidant activity of biological fluids and modified version for simultaneous measurement of total antioxidant power and ascorbic acid concentration. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; Volume 299, pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bernfeld, P. Enzymes of Starch Degradation and Synthesis. In Advances in Enzymology and Related Areas of Molecular Biology; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1951; pp. 379–428. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolidis, E.; Kwon, Y.I.; Shetty, K. Inhibitory potential of herb, fruit, and fungal-enriched cheese against key enzymes linked to type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2007, 8, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, K.Y.; Ajani, E.O.; Biobaku, K.T.; Okediran, B.S.; Azeez, M.O.; Jimoh, G.A.; Aremu, A.; Ahmed, A.O. Cardioprotective Effects of Aqueous Extract of Ripped Musa paradisiaca Peel in Isoproterenol Induced Myocardial Infarction Rat Model. Biomed. Res. Ther. 2021, 8, 4634–4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuwa, T.R.; Akinmoladun, A.C.; Crown, O.O.; Komolafe, K.; Olaleye, M.T. Toxicological Assessment and Ameliorative Effects of Parinari curatellifolia Alkaloids on Triton-Induced Hyperlipidemia and Atherogenicity in Rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 87, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azwanida, N. A Review on the Extraction Methods Use in Medicinal Plants, Principle, Strength and Limitation. Med. Aromat. Plants 2015, 4, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komolafe, K.; Akinmoladun, A.C.; Komolafe, T.R.; Olaleye, M.T.; Akindahunsi, A.A.; Rocha, J.B.T. African locust bean (Parkia biglobosa, Jacq Benth) leaf extract affects mitochondrial redox chemistry and inhibits angiotensin-converting enzyme in vitro. Clin. Phytoscience 2017, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boua, B.B.; Ouattara, D.; Traoré, L.; Mamyrbekova-Békro, J.A.; Békro, Y.-A. Effect of domestic cooking on the total phenolic, flavonoid and condensed tannin content from plantain of Côte d’Ivoire. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2020, 11, 396–403. [Google Scholar]

- Loganayaki, N.; Rajendrakumaran, D.; Manian, S. Antioxidant capacity and phenolic content of different solvent extracts from banana (Musa paradisiaca) and mustai (Rivea hypocrateriformis). Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2010, 19, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shodehinde, S.A.; Oboh, G. Antioxidant properties of aqueous extracts of unripe Musa paradisiaca on sodium nitroprusside induced lipid peroxidation in rat pancreas in vitro. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2013, 3, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anal, A.K.; Jaisanti, S.; Noomhorm, A. Enhanced yield of phenolic extracts from banana peels (Musa acuminata Colla AAA) and cinnamon barks (Cinnamomum varum) and their antioxidative potentials in fish oil. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 2632–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amri, F.S.A.; Hossain, M.A. Comparison of total phenols, flavonoids and antioxidant potential of local and imported ripe bananas. Egypt. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2018, 5, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sandhir, R.; Ojha, S. Evaluation of antioxidant activity and total phenol in different varieties of Lantana camara leaves. BMC Res. Notes 2014, 7, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, Z.; Shahid, S.; Hasnain, A.; Yaseen, E.; Rahimi, M. Functional Foods Enriched with Bioactive Compounds: Therapeutic Potential and Technological Innovations. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e71024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahloko, L.M.; Silungwe, H.; Mashau, M.E.; Kgatla, T.E. Bioactive compounds, antioxidant activity and physical characteristics of wheat-prickly pear and banana biscuits. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboh, G.; Ademosun, A.O.; Ademiluyi, A.O.; Omojokun, O.S.; Nwanna, E.E.; Longe, K.O. In Vitro Studies on the Antioxidant Property and Inhibition of α-Amylase, α-Glucosidase, and Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme by Polyphenol-Rich Extracts from Cocoa (Theobroma cacao) Bean. Pathol. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 549287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasaninezhad, F.; Tavaf, Z.; Panahi, F.; Nourisefat, M.; Khalafi-Nezhad, A.; Yousefi, R. The assessment of antidiabetic properties of novel synthetic curcumin analogues: α-amylase and α-glucosidase as the target enzymes. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2020, 19, 1505–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipiti, T.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Singh, M.; Islam, M.S. In vitro α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory effects and cytotoxic activity of Albizia antunesiana extracts. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2015, 11, S231–S236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechchate, H.; Es-Safi, I.; Louba, A.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Nasr, F.A.; Noman, O.M.; Farooq, M.; Alharbi, M.S.; Alqahtani, A.; Bari, A.; et al. In Vitro Alpha-Amylase and Alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity and In Vivo Antidiabetic Activity of Withania frutescens L. Foliar Extract. Molecules 2021, 26, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shodehinde, S.A.; Ademiluyi, A.O.; Oboh, G.; Akindahunsi, A.A. Contribution of Musa paradisiaca in the inhibition of α-amylase, α-glucosidase and Angiotensin-I converting enzyme in streptozotocin induced rats. Life Sci. 2015, 133, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Xiong, J.; Wang, F.; Grace, M.H.; Lila, M.A.; Xu, R. α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activities of Phenolic Extracts from Eucalyptus grandis × E. urophylla Bark. J. Chem. 2017, 2017, 8516964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yao, F.; Xue, Q.; Fan, H.; Yang, L.; Li, X.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y. Inhibitory effects against α-glucosidase and α-amylase of the flavonoids-rich extract from Scutellaria baicalensis shoots and interpretation of structure-activity relationship of its eight flavonoids by a refined assign-score method. Chem. Cent. J. 2018, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaleye, T.M.; Komolafe, K.; Akindahunsi, A. Effect of methanolic leaf extract of Parkia biglobosa on some biochemical indices and hemodynamic parameters in rats. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2013, 5, 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Vettorazzi, A.; López de Cerain, A.; Sanz-Serrano, J.; Gil, A.G.; Azqueta, A. European Regulatory Framework and Safety Assessment of Food-Related Bioactive Compounds. Nutrients 2020, 12, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamzadeh, S.; Zarenezhad, M.; Montazeri, M.; Zareikordshooli, M.; Sadeghi, G.; Malekpour, A.; Hoseni, S.; Bahrani, M.; Hajatmand, R. Statistical Analysis of Organ Morphometric Parameters and Weights in South Iranian Adult Autopsies. Medicine 2017, 96, e6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porwal, M.; Khan, N.A.; Maheshwari, K.K. Evaluation of Acute and Subacute Oral Toxicity Induced by Ethanolic Extract of Marsdenia tenacissima Leaves in Experimental Rats. Sci. Pharm. 2017, 85, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromwell, W.C.; Otvos, J.D. Low-density lipoprotein particle number and risk for cardiovascular disease. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2004, 6, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Banerjee, S.; Porter, T. Green and black tea extracts inhibit HMG-CoA reductase and activate AMP kinase to decrease cholesterol synthesis in hepatoma cells. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2008, 20, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xu, Y.; Guo, W.; Chen, F.; Zhang, C.; Tan, H.Y.; Wang, N.; Feng, Y. The Impacts of Herbal Medicines and Natural Products on Regulating the Hepatic Lipid Metabolism. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Baky, E.S.; Abdel-Rahman, O.N. Cardioprotective effects of the garlic (Allium sativum) in sodium fluoride-treated rats. J. Basic Appl. Zool 2020, 81, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, O.S.; Orekoya, B.T. Lipid Profile and Oxidative Stress Markers in Wistar Rats following Oral and Repeated Exposure to Fijk Herbal Mixture. J. Toxicol. 2014, 2014, 876035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomar, M.J. Factors affecting the development of adverse drug reactions (Review article). Saudi Pharm. J. SPJ Off. Publ. Saudi Pharm. Soc. 2014, 22, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter, A.I.; Naidu, E.C.; Akang, E.; Ogedengbe, O.O.; Offor, U.; Rambharose, S.; Kalhapure, R.; Chuturgoon, A.; Govender, T.; Azu, O.O. Investigating Organ Toxicity Profile of Tenofovir and Tenofovir Nanoparticle on the Liver and Kidney: Experimental Animal Study. Toxicol. Res. 2018, 34, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinmoladun, A.C.; Olaleye, M.T.; Komolafe, K.; Adetuyi, A.O.; Akindahunsi, A.A. Effect of homopterocarpin, an isoflavonoid from Pterocarpus erinaceus, on indices of liver injury and oxidative stress in acetaminophen-provoked hepatotoxicity. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 26, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Patel, S.; Kotadiya, A.; Patel, S.; Shrimali, B.; Joshi, N.; Patel, T.; Trivedi, H.; Patel, J.; Joharapurkar, A.; et al. Age-related changes in hematological and biochemical profiles of Wistar rats. Lab. Anim. Res. 2024, 40, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lala, V.; Zubair, M.; Minter, D.A. Liver Function Tests. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gowda, S.; Desai, P.B.; Kulkarni, S.S.; Hull, V.V.; Math, A.A.K.; Vernekar, S.N. Markers of renal function tests. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2010, 2, 170–173. [Google Scholar]

- Ogundipe, D.J.; Akomolafe, R.O.; Sanusi, A.A.; Imafidon, C.E.; Olukiran, O.S.; Oladele, A.A. Ocimum gratissimum Ameliorates Gentamicin-Induced Kidney Injury but Decreases Creatinine Clearance Following Sub-Chronic Administration in Rats. J. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 22, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Injac, R.; Radic, N.; Govedarica, B.; Perse, M.; Cerar, A.; Djordjevic, A.; Strukelj, B. Acute doxorubicin pulmotoxicity in rats with malignant neoplasm is effectively treated with fullerenol C60(OH)24 through inhibition of oxidative stress. Pharmacol. Rep. PR 2009, 61, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component | Retention | Area | Height | Concentration (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeic Acid | 2.8000 | 3585.21 | 176.139 | 2.6734 |

| Lanosterol | 3.7160 | 534.241 | 28.8810 | 0.3984 |

| Syringin | 4.4000 | 489.100 | 23.5380 | 0.3647 |

| Myricetin | 4.8830 | 865.163 | 40.0710 | 0.6451 |

| Sitoindoside I | 5.3330 | 443.163 | 34.5420 | 0.3305 |

| Sitoindoside II | 5.5830 | 893.413 | 68.1380 | 0.6661 |

| Cyclomusatenol | 6.7660 | 2267.58 | 105.220 | 1.6909 |

| Cyclomusatenone | 7.2500 | 1022.77 | 89.5790 | 0.7627 |

| Luteolin | 7.4830 | 1786.61 | 160.532 | 1.3322 |

| Quercetin | 7.9500 | 2346.70 | 76.5430 | 1.7499 |

| Kaempferol | 9.3000 | 2016.48 | 160.053 | 1.5036 |

| Capsaicin | 9.6000 | 651.599 | 49.9540 | 0.4859 |

| B-Sitosterol | 10.316 | 1283.35 | 51.6850 | 0.9570 |

| P-Hydroxybenzoic Acid | 11.016 | 2089.50 | 123.220 | 1.5581 |

| Leucocyanidin | 11.566 | 640.560 | 31.9610 | 0.4776 |

| Apigenin | 12.216 | 1266.82 | 49.1180 | 0.9446 |

| Albumin | ALT | AST | Total Bilirubin | Direct Bilirubin | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Serum | Liver | Serum | Liver | Serum | Liver | Serum | Liver | Serum | Liver |

| (g/dL) | (g/dL) | (U/L) | (U/mg Protein) | (U/L) | (U/mg Protein) | (mg/dL) | (mg/dL) | (mg/dL) | (mg/dL) | |

| Control | 3.23 ± 0.02 | 0.048 ± 0.002 | 30.36 ± 4.02 | 3.00 ± 0.28 | 65.63 ± 3.15 | 3.03 ± 0.30 | 3.60 ± 0.27 | 5.78 ± 0.29 | 2.23 ± 0.14 | 3.57 ± 0.28 |

| MPE 100 mg/kg | 3.38 ± 0.05 | 0.050 ± 0.003 | 16.16 ± 2.58 ** | 2.82 ± 0.29 | 71.02 ± 3.90 | 3.06 ± 0.25 | 4.07 ± 0.31 | 5.31 ± 0.26 | 3.21 ± 0.43 | 3.23 ± 0.20 |

| MPE 200 mg/kg | 3.35 ± 0.10 | 0.064 ± 0.004 ** | 14.54 ± 2.56 ** | 3.52 ± 0.15 | 46.05 ± 6.88 * | 3.71 ± 0.23 | 3.78 ± 0.20 | 5.29 ± 0.26 | 2.78 ± 0.21 | 2.85 ± 0.07 |

| MPE 400 mg/kg | 3.33 ± 0.13 | 0.050 ± 0.003 | 17.95 ± 1.57 ** | 3.51 ± 0.51 | 54.87 ± 1.88 | 3.47 ± 0.39 | 4.03 ± 0.17 | 5.24 ± 0.10 | 3.73 ± 0.65 | 2.88 ± 0.26 |

| Uric Acid | Urea | Creatinine | LDH | CK-MB | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Serum | Kidney | Serum | Kidney | Serum | Kidney | Serum | Heart | Serum | Heart |

| (mg/dL) | (mg/dL) | (mg/dL) | (mg/dL) | (µmol/L) | (µmol/L) | (U/L) | (U/mg Protein) | (U/L) | (U/mg Protein) | |

| Control | 6.53 ± 0.86 | 16.71 ± 0.69 | 46.30 ± 4.51 | 19.27 ± 1.54 | 109.0 ± 4.63 | 43.00 ± 3.19 | 126.9 ± 6.28 | 10.48 ± 1.22 | 309.2 ± 13.4 | 0.73 ± 0.12 |

| MPE 100 mg/kg | 6.33± 1.08 | 20.28± 0.40 * | 28.57 ± 4.25 ** | 18.43 ± 1.02 | 106.5 ± 10.0 | 50.78 ± 5.23 | 134.5± 7.60 | 16.98 ± 4.80 | 311.0 ± 13.28 | 1.39 ± 0.53 |

| MPE 200 mg/kg | 2.08 ± 0.24 ** | 18.02 ± 1.59 | 26.91 ± 1.14 ** | 19.00 ± 1.11 | 96.20 ± 5.88 | 60.94 ± 10.5 | 89.46 ± 5.32 ** | 15.20 ± 5.67 | 215.8 ± 13.28 *** | 0.80 ± 0.11 |

| MPE 400 mg/kg | 1.94 ± 0.43 ** | 15.63 ± 0.62 | 24.03 ± 2.49 *** | 17.99 ± 1.21 | 97.48 ± 5.13 | 29.92 ± 3.60 | 99.03 ± 7.32 ** | 13.96 ± 2.14 | 231.5 ± 8.80 *** | 1.96 ± 0.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Komolafe, T.R.; Olaleye, M.T.; Akinmoladun, A.C.; Komolafe, K.; Akindahunsi, A.A. Glycemic Responses, Enzyme Activity, and Sub-Acute Toxicity Evaluation of Unripe Plantain Peel Extract in Rats. Dietetics 2026, 5, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics5010003

Komolafe TR, Olaleye MT, Akinmoladun AC, Komolafe K, Akindahunsi AA. Glycemic Responses, Enzyme Activity, and Sub-Acute Toxicity Evaluation of Unripe Plantain Peel Extract in Rats. Dietetics. 2026; 5(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics5010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleKomolafe, Titilope R., Mary T. Olaleye, Afolabi C. Akinmoladun, Kayode Komolafe, and Akintunde A. Akindahunsi. 2026. "Glycemic Responses, Enzyme Activity, and Sub-Acute Toxicity Evaluation of Unripe Plantain Peel Extract in Rats" Dietetics 5, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics5010003

APA StyleKomolafe, T. R., Olaleye, M. T., Akinmoladun, A. C., Komolafe, K., & Akindahunsi, A. A. (2026). Glycemic Responses, Enzyme Activity, and Sub-Acute Toxicity Evaluation of Unripe Plantain Peel Extract in Rats. Dietetics, 5(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics5010003