Abstract

Monitored neutrino beams are facilities where beam diagnostics enable the counting and identification of charged leptons in the decay tunnel of a narrow band beam. These facilities can monitor neutrino production at the single particle level (flux precision %) and provide information about the neutrino energy at the 10% level. The ENUBET Collaboration has demonstrated that lepton monitoring might be achieved not only by employing kaon decays but also by identifying muons from the decays and positrons from the decay-in-flight of muons before the hadron dump. As a consequence, beam monitoring can be performed using the ENUBET technique even when the kaon production yield is kinematically suppressed. This finding opens up a wealth of opportunities for measuring neutrino cross-sections below 1 GeV. In this paper, we investigate this opportunity at the European Spallation Source (ESS), which is an ideal facility to measure and cross-sections in the 0.2–1 GeV range. We also describe the planned activities for the design of this beam at the ESS within the framework of the ESSSB+ design study, which was approved by the EU in July 2022.

1. Introduction

Neutrino cross-sections at the GeV scale are currently known with limited precision in spite of their prominent role in the next generation of long-baseline neutrino oscillation experiments (DUNE, Hyperkamiokande, and, on a longer timescale, ESSSB) [1]. The precision is limited by poor knowledge of the neutrino flux at the source. Furthermore, precision cross-section measurements are plagued by large uncertainties in nuclear effects that bias the energy reconstruction of the initial state neutrino. Indeed, the neutrino energy measurement is currently based on the reconstruction of final state particles that are sensitive to reinteraction in the nuclear medium [2]. Monitored neutrino beams [3] are the ideal facilities to address these challenges and improve current cross-section measurements by one order of magnitude. These facilities are conventional neutrino beams where neutrinos are produced by the two-body decay of charged pions () and the two- and three-body decays of charged kaons. As depicted in Figure 1, pions and kaons produced after the target are transferred to the decay tunnel, which is located far from the target axis. The walls of the decay tunnel are instrumented with cost-effective charged particle detectors; in the ENUBET [4,5,6] implementation of monitored neutrino beams, they are a longitudinally segmented calorimeter with a photon veto located in the innermost part of the calorimeter (see Figure 2) [7,8]. The instrumentation is complemented by a hadron dump that stops undecayed particles at the end of the tunnel. Charged leptons produced in the tunnel are detected by the calorimeter and the devices positioned in the hadron dump. The hadron dump detectors can, thus, measure forward leptons produced at small angles. The rate, energy, and angular distribution of the leptons are employed to perform a precise determination of the neutrino flux. In 2022, ENUBET presented an end-to-end simulation of the CERN-based beamline and estimated the flux systematics using the same technique currently in use in T2K and DUNE [9]. This study demonstrated that the main flux systematics can be reduced to well below 1%.

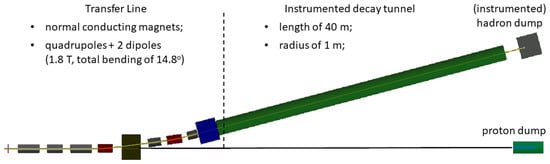

Figure 1.

Layout of the ENUBET monitored neutrino beam at CERN. Protons impinging on the target produce secondaries that are sign- and momentum-selected using a static (i.e., hornless) transfer line. They are steered to the decay tunnel. Particles impinging on the tunnel wall are detected by the instrumentation (segmented calorimeters) installed in the tunnel. Undecayed secondaries are stopped by the hadron dump, while protons that did not interact with the target are stopped by the proton dump.

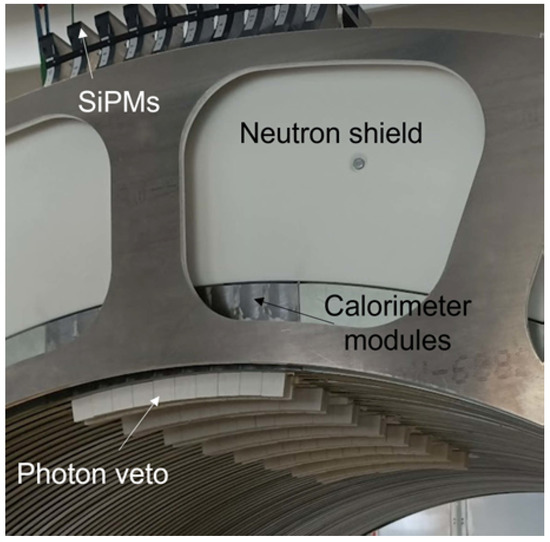

Figure 2.

View of the ENUBET demonstrator tested at CERN in 2022. The prototype corresponds to a fraction of the instrumented decay tunnel with a curvature radius of 1 m [9]. It comprises a scintillator-based photon veto and a modular calorimeter. The scintillation light produced in the calorimeter and in the veto is brought to the outer part of the detector by means of wavelength-shifting fibers and read out by SiPMs. SiPMs are protected from fast neutrons by a borated plastic shield.

In 2020–2022, the ENUBET Collaboration devised a hornless focusing system that momentum-selects particles using static components (dipole and quadrupoles) [9,10]. This system does not rely on a magnetic horn and, therefore, can employ slow proton extraction. This breakthrough is being used for a CERN-based implementation of ENUBET at the CERN SPS proton-synchrotron, where the kaon yield is quite large ( kaons per proton on target at the entrance of the decay tunnel), and the extraction is so slow (2–4 s) that pile up is negligible in the tunnel instrumentation. The reduced level of pile-up creates the possibility to track and monitor muons from pion decays too, using an instrumented hadron dump developed by the PIMENT (Picosecond Micromegas for ENUBET) project [11]. The ESSSB project [12,13] has designed a novel long-baseline beam fed by the outstanding power (4 MW) of the proton driver under construction at the European Spallation Source (ESS). Since the ESSSB beam is horn-based, a new accumulation ring is needed to compress the 3 ms proton pulses to 1.2 s. In the construction phase of this accumulator, the ESS proton driver can, thus, be employed thanks to an ENUBET-like monitored neutrino beam (MNB@ESS), which benefits from the slow (∼3 ms) extraction. MNB@ESS can, thus, measure the cross-section in an energy range that is unattainable at CERN (0.2–0.5 GeV), and play an important role both in HyperKamiokande [14] and ESSSB [13]. Further, the ENUBET beamline can be engineered to enhance the number of electron neutrinos produced by the decay-in-flight of muons: . NMB@ESS is then a powerful source of , whose cross-section may depart from the cross-section in spite of lepton universality because of nuclear effects. In 2023–2026, the ENUBET Collaboration will investigate this opportunity in the framework of Working Package 6 (WP6) of the ESSSB+ design study. We discuss below the early findings and planning of activities.

2. Neutrinos at the ESS

The European Spallation Source provides the most powerful proton driver in Europe. The duty cycle of its linac is 4% and an increase in duty cycle up to 8% is mandatory for a high-intensity neutrino beam aimed at studying neutrino oscillations and CP violation [15]. A facility for cross-section measurements does not require a large average power and MNB@ESS can either be implemented in shared mode with standard (material-science) users or benefit from the linac upgrade, which is mandatory for ESSSB. The current linac repetition rate is 14 Hz and will reach 28 Hz at the time of operation of ESSSB. Protons are accelerated to 2 GeV and the maximum linac current during the 2.86 ms spill is 62.5 mA. The beam power is, thus, 5 MW. This value will be doubled for the ESSSB experiment, which will leverage 5 MW, allocating half of the 28 Hz pulses for neutrino physics. ESSSB needs a 400 m accumulator ring to reduce the pulse duration down to 1.2 s. In the construction phase of ESSSB and its accumulator, a fraction of this duty cycle will be available for cross-section experiments. Current estimates indicate that an average power of kW is needed to achieve the goals of MNB@ESS. A detailed assessment of the requested power will be performed in the forthcoming years in the framework of ESSSB+. This power can be devoted to neutrino physics without perturbing the standard operation of the ESS, and leveraging a conventional graphite-based target similar to the target station of ENUBET at CERN. The ESSSB project requires the construction of a 1 kton water-based near detector located 250 m from the target. This detector will be employed for cross-section measurement too. The choice of water is driven by the needs of ESSSB but it is an optimal choice in the world experimental strategy for neutrino oscillation since the MNB@ESS cross-sections will be implemented for the systematics reduction programme of the (water-Cherenkov) HyperKamiokande experiment. Moderate (100 t) mass detectors with different targets can be built on the ESS premises to cover a broader range of targets. In particular, a low-Z deuteron or hydrogen-based detector would represent a major advance in electroweak nuclear physics because it would allow probing of neutrino scattering in nuclei at the single nucleon scale.

3. Layout of the Monitored Neutrino Beam

MNB@ESS will produce neutrinos from a dedicated transfer line steering 2 GeV protons from the ESS linac to the target station. Given the moderate power of the beam requested for MNB@ESS, a dedicated target station is an ideal choice since it obviates any interference risk with the construction of the 4-MW class ESSSB target station. The Working Package 6 of ESSSB+ will investigate this option together with a potential sharing of the ESSSB station for low-intensity physics. In the preparatory phase of ESSSB+, the ENUBET Collaboration performed a preliminary layout study to assess the main design constraints arising from the use of 2 GeV, 3 ms proton pulses. Unlike ENUBET, MNB@ESS is not based on kaons, which are suppressed by the large kinematic threshold for production. Protons of 2 GeV on a graphite target produce pions with large yields up to 1.5 GeV. The current central momentum of MNB@ESS is 1 GeV with a momentum bite of 10%. At these energies, we expect a pion yield of about per proton-on-target at the entrance of the decay tunnel. Inside the 30 m decay tunnel, muons are produced with an average angle of ∼30 mrad with respect to the tunnel axis. A total of 36% of the pions decay in the tunnel before reaching the hadron dump. Even if the amount of muon decay in flight is small (a few per mill of the incoming pions), the statistics at the ESSSB near detector are remarkable thanks to the large average power of the beam. In the ESSSB near detector, we expect CC events and CC events in one year of data collection, corresponding to protons-on-target from a 300 kW beam (proton momentum: 2 GeV). This statistic is, thus, comparable with ENUBET at CERN, but covers an energy range that cannot be addressed there. For the example above, the peak energy of CC events is 0.4 GeV with a momentum spread of about 10%. Since electron neutrinos are produced by the three-body decay of muons, their spectrum is much broader and extends from 0.1 to 0.9 GeV. There are large uncertainties in these estimates since a dedicated beamline for MNB@ESS has not yet been developed. Such a development is a key deliverable of ESSSB+ WP6. Unlike ENUBET at CERN,

- the length of the transfer line plays a minor role since the lifetime of pions at rest is much longer than kaons;

- the yield can be further enhanced by increasing the length of the decay tunnel. There is a trade-off, however, between yield and cost since the tunnel and the hadron dump are instrumented with calorimeters and trackers;

- the precision of the neutrino energy can be significantly improved by employing the “narrow-band off-axis” (NBOA) technique [6] used by ENUBET at CERN. This technique makes use of the strong correlation between the neutrino energy and its production angle in a two-body decay. NBOA has not been studied yet at ESS and will be implemented in MNB@ESS in the course of the ESSSB+ project.

4. Conclusions

The development of a static focusing system performed by the ENUBET Collaboration in 2020–22 opens up a wealth of application possibilities. In this paper, we discussed the most prominent of these: the construction of a monitored neutrino beam at the European Spallation Source to measure the neutrino cross-section with a precision of 1% in the energy range of interest for HyperKamiokande and ESSSB. The measurement will be performed in the construction phase of the ESSSB accumulator since the neutrino facility (MNB@ESS) employs the ESS in its present design, i.e., without additional accelerator developments. Preliminary calculations show that we can accumulate () () CC events per year with a 1 kton mass water Cherenkov detector while retaining the same precision in the flux of ENUBET at CERN. This opportunity will be addressed in the framework of ESSSB+ (WP6) from 2023 to 2026.

Author Contributions

The study presented in this paper is based on the end-to-end simulation and prototypes developed by the ENUBET collaboration listed above. The manuscript was prepared by F.T. and revised by all other authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation program under Grant Agreement No. 681647 and from the Italian Ministry of Education and Research (MIUR, Bando FARE, progetto NuTech). It is also supported by the Department of Physics “G. Occhialini”, University of Milano-Bicocca (project 2018-CONT-0128).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Katori, T.; Martini, M. Neutrino–nucleus cross sections for oscillation experiments. J. Phys. Nucl. Part. Phys. 2017, 45, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Ruso, L.; Athar, M.S.; Barbaro, M.B.; Cherdack, D.; Christy, M.E.; Coloma, P.; Donnelly, T.W.; Dytman, S.; de Gouvea, A.; Hill, R.J.; et al. NuSTEC White Paper: Status and challenges of neutrino–nucleus scattering. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2018, 100, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhin, A.; Ludovici, L.; Terranova, F. A novel technique for the measurement of the electron neutrino cross section. Eur. Phys. J. C 2015, 75, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acerbi, F.; Ballerini, G.; Bonesini, M.; Brizzolari, C.; Brunetti, G.; Calviani, M.; Carturan, S.; Catanesi, M.; Cecchini, S.; Cindolo, F.; et al. The ENUBET Project; Technical Report CERN-SPSC-2018-034; SPSC-I-248; CERN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Acerbi, F.; Bonesini, M.; Branca, A.; Brizzolari, C.; Brunetti, G.; Calviani, M.; Capelli, S.; Carturan, S.; Catanesi, M.; Charitonidis, N.; et al. NP06/ENUBET Annual Report for the CERN-SPSC; Technical Report CERN-SPSC-2020-009; SPSC-SR-2688; CERN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Acerbi, F.; Angelis, I.; Bonesini, M.; Branca, A.; Brizzolari, C.; Brunetti, G.; Calviani, M.; Capelli, S.; Carturan, S.; Catanesi, M.; et al. NP06/ENUBET Annual Report for the CERN-SPSC; Technical Report CERN-SPSC-2021-013; SPSC-SR-2908; CERN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Acerbi, F.; Ballerini, G.; Berra, A.; Brizzolari, C.; Brunetti, G.; Catanesi, M.G.; Cecchini, S.; Cindolo, F.; Coffani, A.; Collazuol, G.; et al. Irradiation and performance of RGB-HD Silicon Photomultipliers for calorimetric applications. J. Instrum. 2019, 14, P02029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acerbi, F.; Bonesini, M.; Bramati, F.; Branca, A.; Brizzolari, C.; Brunetti, G.; Capelli, S.; Carturan, S.; Catanesi, M.; Cecchini, S.; et al. The ENUBET positron tagger prototype: Construction and testbeam performance. J. Instrum. 2020, 15, P08001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branca, A. ENUBET: The first monitored neutrino beam. In Proceedings of the XLI International Conference of High Energy Physics (ICHEP2022) PoS(ICHEP2022), Bologna, Italy, 6–13 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Parozzi, E. The design of the ENUBET beamline. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Workshop on Neutrinos from Accelerators (NuFact2022), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 30 July–6 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Papaevangelou, T. Développement d’un Détecteur PICOSEC-Micromegas pour ENUBET—PIMENT. 2022. Available online: https://anr.fr/Projet-ANR-21-CE31-0027 (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- Alekou, A.; Baussan, A.E.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Kraljevic, N.B.; Blennow, M.; Bogomilov, M.; Bolling, B.; Bouquerel, E.; Buchan, O.; Burgman, A.; et al. The European Spallation Source neutrino Super Beam Conceptual Design Report. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.01208. [Google Scholar]

- Alekou, A.; Baussan, A.E.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Kraljevic, N.B.; Blennow, M.; Bogomilov, M.; Bolling, B.; Bouquerel, E.; Buchan, O.; Burgman, A.; et al. Updated physics performance of the ESSnuSB experiment: ESSnuSB collaboration. Eur. Phys. J. C 2021, 81, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, K.; Abe, K.; Aihara, H.; Aimi, A.; Akutsu, R.; Andreopoulos, C.; Anghel, I.; Anthony, L.; Antonova, M.; Ashida, Y.; et al. Hyper-Kamiokande Design Report. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.04163. [Google Scholar]

- Alekou, A.; Baussan, E.; Kraljevic, N.B.; Blennow, M.; Bogomilov, M.; Bouquerel, E.; Burgman, A.; Carlile, C.J.; Cederkall, J.; Christiansen, P.; et al. Updated physics performance of the ESSnuSB experiment. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.07585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).