Abstract

This letter aims to investigate thermodynamic processes in small systems in the Onsager region by showing that fundamental quantities such as total entropy production can be discretized on the mesoscopic scale. Even thermodynamic variables can conjugate to thermodynamic forces, and thus, Glansdorff–Prigogine’s dissipative variable may be discretized. The canonical commutation rules (CCRs) valid at the mesoscopic scale are postulated, and the measurement process consists of determining the eigenvalues of the operators associated with the thermodynamic quantities. The nature of the quantized quantity , entering the CCRs, is investigated by a heuristic model for nano-gas and analyzed through the tools of classical statistical physics. We conclude that according to our model, the constant does not appear to be a new fundamental constant but corresponds to the minimum value.

1. Introduction

Mesoscopic structures have emerged as a dynamic and rapidly advancing research frontier, captivating scientists across disciplines, including physics, chemistry, and mineralogy, as well as the life sciences. The relentless push towards miniaturization, with devices now spanning mere nanometers, is not only revolutionizing the creation of new materials but also deepening our grasp of the fundamental laws that dictate the behavior of systems at the mesoscopic scale (see, for instance, [1,2,3,4,5,6]). Based on recent experimental results and previous theoretical research, we investigate thermodynamic processes in small systems in Onsager’s region. To this end, we begin with a brief overview of the key aspects of Prigogine’s formulation of thermodynamic processes within Onsager’s regime. Let us consider a system characterized by n degrees of advancement [7,8,9,10,11]. The deviations of from the values , assumed by the degrees of advance when the system is in local equilibrium, are denoted by , that is, . Therefore, may represent the fluctuations of various thermodynamic quantities, such as temperature and pressure. According to the principles of thermodynamics, one can introduce for any macroscopic system a state function S, the entropy of the system, which has the following properties. The entropy variation due to the fluctuations reads [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]

where

where denotes the entropy supplied to the system by its surroundings, and is the entropy produced inside the system, respectively. The second law of thermodynamics states that must be zero for reversible (or equilibrium) transformations and positive for irreversible transformations of the system, i.e., . The entropy supplied , on the other hand, may be positive, zero, or negative, depending on the interaction of the system with its surroundings. We also have [19,20]

with denoting that the thermodynamic fluxes conjugate to the thermodynamic force , and denotes an infinitesimal spatial volume element occupied by the system. In Equation (3), we have adopted the Einstein convention of repeated indices. Unless stated otherwise, this convention will also be adopted in the sequel to this manuscript. To work with entropy production strength, which has the dimension [Energy]/([Temperature] × [time]), we adopt the following definition for the thermodynamic forces, the thermodynamic fluxes, and the thermodynamic variables, respectively:

with () denoting space–time. Equation (3) links the entropy production strength with the thermodynamic forces and the conjugate fluxes. To obtain the expression for the entropy production strength solely in terms of the thermodynamic forces, it is necessary to relate the dissipative fluxes to the thermodynamic forces that produce them. These closure relations are called transport flux–force relations. For thermodynamic systems in Onsager’s region, the most used transport relations are [19]

where ; is called Onsager’s matrix, where the entries are the transport coefficients, independent of the thermodynamic forces. Note that to perform calculations, the transport coefficients must be written in a dimensionless form. In terms of the transport coefficients, in Onsager’s region, the local entropy production strength can be brought into the form

So, as we wish, has the dimension [Energy]/([Temperature] × [time]) while has the dimension [Energy]/([Temperature] × [time] × [Volume]).

The Space of the Thermodynamic Forces

To continue with the formalism, it is necessary to define the space in which calculations can be performed. For this, we have to specify two quantities: the metric tensor and the affine connection [21,22,23,24,25,26]. The metric tensor and the affine connection are determined by physics. More specifically, the metric tensor is identified with the symmetric piece of the transport coefficients, and the expression of the affine connection is determined by imposing the validity of the Glansdorff-Prigogine Universal Criterion of Evolution [23,26]. For the second law of thermodynamics, the square distance between two infinitely close points in the space of the thermodynamic forces is always a non-negative quantity. Additionally, in the thermodynamic space, the total entropy production in Onsager’s region reads

with L denoting the determinant of Onsager’s matrix and V the volume occupied by the system, respectively.

2. Quantization of the Entropy Production Strength

2.1. A Heuristic Approach

One of the main objectives of the Brussels School of Thermodynamics, founded by Théphile De Donder and Ilya Prigogine, was to investigate systems on a mesoscopic scale to discover the fundamental laws governing them. We start our analysis with the following (heuristic) observation. A quasi-localized disturbance of entropy production can be obtained using a linear superposition of modes with close mode numbers. So, if the system is subject to n independent thermodynamic forces, a local disturbance of entropy production strength can be represented as a superposition of plane waves with the generic wave number compatible with periodicity conditions:

Notice that the modes are in the space of thermodynamic forces (and not in the ordinary space). It is also important to clarify that by local disturbance in entropy production strength, we are referring to a fluctuation or deviation from the average entropy production in a small region of space and time. To analyze or model such fluctuations, a common approach (also used in fluid dynamics, quantum mechanics, and statistical physics) is to decompose the disturbance into plane wave modes using a Fourier expansion. So, at the mesoscopic scale, both fluxes and forces can exhibit stochastic behavior and wave-like excitations. Consider a small disturbance in the entropy production density. This can be decomposed using a spatial Fourier series, or transform in the continuum limit (8), assuming periodic or suitable boundary conditions where is the wavevector (spatial frequency) and is the amplitude of the fluctuation mode at wavevector , respectively. Notice that this representation is analogous to decomposing vibrations on a string into harmonics—here, the entropy production field is decomposed into spatial fluctuation modes. In our formalism for the thermodynamics of irreversible processes, a rich geometric structure is introduced to describe nonequilibrium systems. At the heart of this formulation is the entropy production density, denoted by , which measures the local intensity of irreversibility in space–time. Below, I provide a geometric interpretation of , situating it within the framework of fiber bundles over the manifold of thermodynamic variables.

Let denote the thermodynamic configuration space, whose coordinates are the local thermodynamic variables such as temperature, chemical potentials, or densities. Each point corresponds to a specific thermodynamic state of the system. In the framework of irreversible thermodynamics, the entropy production density at a point in space-time is expressed as the bilinear contraction of thermodynamic fluxes and their conjugate thermodynamic forces :

This relation captures the idea that entropy is produced when irreversible processes occur, such as heat conduction or particle diffusion. The non-negativity of is guaranteed by the second law of thermodynamics. To give a geometric description, we consider the following structure: (i) The manifold serves as the base space. (ii) At each point , we associate a fiber that is a vector space of thermodynamic forces and fluxes; (iii) Thermodynamic forces belong to the cotangent space , while thermodynamic fluxes belong to the tangent space .

The entropy production is then the result of the natural pairing between elements of and :

Here, and are vector fields on the fiber, and the pairing represents the contraction of a covector with a vector, yielding a scalar. Since is a scalar arising from this pairing at each point , it defines a section of a scalar bundle over . This scalar bundle is associated with the vector bundle of thermodynamic forces and fluxes through their bilinear pairing. In mathematical terms, if we denote the vector bundle of fluxes as and the dual bundle of forces as , then is a section of the bundle:

and the scalar contraction at each point yields

where denotes the space of smooth scalar fields over . Physically, the scalar field represents the local rate of entropy production due to irreversible processes. Its geometric interpretation provides a natural framework for coupling thermodynamics with field theory and differential geometry. Furthermore, it provides a structure to encode nonequilibrium constraints, symmetries, and generalizations beyond linear irreversible thermodynamics (e.g., including nonlinear effects or generalized forces). In our framework, this structure becomes essential when introducing connections and curvature (e.g., gauge-like structures) to describe the system’s dynamics out of equilibrium. As is known, Fourier’s theorem requires

These uncertainty relations have a clear mathematical underpinning rooted in Fourier analysis, independent of operator-based quantization, and are valid for any quantity conjugate to time (or the wavevectors) through spectral decomposition. Based on recent experimental observations, a heuristic framework has been proposed, suggesting that, at the mesoscopic level and within the thermodynamic force space, the entropy production rate scales with frequency [27]. In [28], it is established that the thermodynamic variable , which is conjugate to the force , must correspondingly scale with the wavevector . Consequently, we arrive at

with denoting Boltzmann’s constant times a pure number, say , undetermined at this stage. On the mesoscopic scale, thermodynamic quantities like entropy production become stochastic and discrete due to fluctuations. Entropy production reflects irreversible energy dissipation, which arises from the activation of discrete modes, each characterized by a frequency. These modes resemble oscillators, and the total entropy production can be modeled similarly to a system of decoupled harmonic oscillators. This framework aligns with the fluctuation theorem, which imposes fundamental limits, similar to the quantum time-energy uncertainty principle, on the simultaneous determination of entropy production and observation time. A combination of Equation (13) with Equation (14) yields

Let us interpret inequalities (15) from the physical point of view. denotes the temporal resolution or measurement uncertainty in time, that is, the minimum time window over which the entropy production rate can be determined with uncertainty . Thus, the thermodynamic uncertainty relation (15) can be interpreted as follows: To determine the entropy production rate of a mesoscopic system with accuracy , one must observe the system over a time interval of at least . The more accurately one attempts to resolve , the longer the observational time window must be. This principle reflects a fundamental limit on the precision with which certain pairs of physical quantities, such as entropy production rate and time or thermodynamic force and its corresponding thermodynamic variable, can be predicted from initial conditions. In other words, we cannot precisely determine both the entropy production rate of a system and time simultaneously; the more accurately we know the system’s entropy production, the less accurately we know the time, and vice versa. Similarly, there is an uncertainty relationship between a thermodynamic force and its corresponding thermodynamic variable. The pairs of variables () and () may be called canonically conjugate (in analogy with the quantum mechanics terminology). We conclude this section by mentioning that the introduction of in Equation (15) is essential for dimensional consistency. The dimensionless factor must be introduced, as there is no guarantee that the entropy constant is precisely equal to Boltzmann’s constant. However, we do not stop at the heuristic level; in theoretical physics, a physically plausible intuition, even if initially heuristic, gains legitimacy when it can be grounded in formal mathematical structures. In the subsequent section of the work, the formalism of second quantization to thermodynamic observables is applied. In this framework, the postulation of entropy production quantization via the parameter becomes more than just a dimensional placeholder; it is introduced to explore deeper structural features of nonequilibrium thermodynamics. If the second quantization approach indeed validates the CCRs, then may be regarded as a fundamental quantity governing entropy fluctuations at mesoscopic scales.

2.2. The Formalism of Second Quantization and the Thermodynamic Commutation Rules

We are now faced with two issues: (i) A rigorous formalism must support the heuristic intuitions expressed in the previous subsection, and (ii) we are dealing with many entities with infinite degrees of freedom, as these entities are continually being produced and absorbed. The appropriate mathematical tool for treating these problems is provided by the formalism of second quantization (SQ), which is largely used in quantum field theory. The second quantization is a mathematical algorithm for dealing with a large assembly of identical entities [29,30]. This mathematical algorithm is based on introducing canonical commutation rules (CCRs) where the physical quantities are “promoted” to operators. Note that the introduction of the CCRs do not necessarily concern quantum mechanics. Still, they are an indispensable tool for treating a huge number of identical entities that can be produced and absorbed. Hence, by the SQ-formalism, we have to promote the single variables and t, and and to operators, which act on some state space of the system, separately, imposing a “bind” between them so that their products behave "as we wish” (see also [28]). At the mesoscopic scale, we have to write

with denoting the commutator between two operators: and the Kronecker delta, respectively. In ref. [27] we can find recent experiments where the entropy production in nonequilibrium systems has been measured. To the best of our knowledge, ref. [27] provides the most accurate value of the lowest limit of this constant that has appeared up to now in the literature. In ref. [27], we find several examples of experimental traces for the tip position of different mechano-sensory hair bundles as a function of time. The authors estimated the local irreversibility measure obtained from a single 30 s recordings of the oscillations shown in these examples. The sampling rate was kHz. From these experiments, we can estimate (albeit approximately) the numerical value of . We find , so, J/K. In the forthcoming section, we shall provide a (rough) estimation of the constant for a quasi-ideal gas. We shall see that, in this case, does not appear to be a new fundamental constant but corresponds to the minimum value.

3. Discretization of the Total Entropy Production Strength in Onsager’s Regime

The total entropy production strength reads

The local entropy production strength can be split into two contributions [31,32]:

Let us now perform the following linear coordinate transformation:

with denoting the Identity matrix. So, after transformation, . Notice that, since the matrix is a positive definite matrix, there always exists a matrix , which satisfies condition (19). After the transformation, we get

In the space of the thermodynamic forces, the Fourier expansion in a finite box of volume V of the thermodynamic fluxes reads

where

In mesoscopic nonequilibrium thermodynamics, we treat the thermodynamic flux as a fluctuating field defined over the abstract space of thermodynamic forces, . Assuming this space is bounded, akin to confining a field in a finite spatial box, we perform a Fourier expansion of in . Each mode labeled by corresponds to an independent dynamical degree of freedom. As we shall soon see, through linear response theory, each mode can be shown to behave like a harmonic oscillator, leading to the result that total entropy production strength is a sum over quantized oscillator contributions. Plugging Equation (21) and the expression for (in this case, ) into Equation (20) yields

where the orthogonality relation

has been taken into account. This expression is identical to the Hamiltonian of a harmonic oscillator if we set the value of the and identify the following terms: position → , momentum → , and frequency → (see, for example, [33]). So, we first define two new dimensionless operators, and , as follows:

In terms of these new variables, the expression for reads

As for the case of the harmonic oscillator, we have to assume the validity of the following canonical commutation rules (CCRs):

The two operators of creation “” and destruction “” can be introduced and defined as usual (see, for example, [34]):

We finally obtain the discretization of the total entropy production strength in Onsager’s region

where the number operator has been introduced. To sum up, in the space of the thermodynamic forces, the total entropy production strength behaves as the sum of “” (discretized) independent one-dimensional harmonic oscillators, each oscillating with frequency .

4. The Correspondence Principle with the Einstein-Prigogine Theory of Fluctuations

In principle, the constant contribution

diverges. This expression is the total entropy production for a macroscopic system generated by very small fluctuations around the thermodynamic equilibrium. To analyze this term, we consider the Einstein-Prigogine theory of equilibrium fluctuations. In this theory, the probability P of finding a state in which the values of lie between and is [35]

where ensures normalization to unity. Expression (31) is only valid for small spontaneous fluctuations around the thermodynamic equilibrium and not for systematic deviations from equilibrium. Prigogine showed the validity of the following important result: whatever the thermodynamic system (hydrodynamic, chemical, etc.), due to spontaneous equilibrium fluctuations, the average entropic production is [12]

with n denoting the number of the independent thermodynamic forces. Now we have to calculate the eigenvalues of the operator by using the canonical commutation rules. Detailed calculations for obtaining the expression for the operator can be found in [28]. We have

where is a definite positive matrix. Hence, there exists a linear coordinate transformation such that

With a suitable definition of a new set of dimensionless variables, we have

and introducing the operators of creation and destruction and , and the number operator , we get

where the canonical commutation rules have been taken into account. Equation (36) coincides with the ground state calculated by the Einstein-Prigogine fluctuation theory by setting (the Corresponding Principle) [28]:

This yields the following expression for the entropy production operator:

having discrete eigenvalues

5. A Heuristic Model for Determining for a Quasi-Ideal Gas

We aim to investigate the physical origin of the constant entering the CCRs. We start with the simplest assumption: By a statistical model for nano-gases, we can derive the expression for . To this end, we adopt a (very) simple heuristic model for nano-gas with the following assumptions:

- (1)

- The limit case is reached when the distance between the molecules of the nano-gas is (approximately) twice the Bohr radius ().

- (2)

- The spherical-molecule model is adopted. Beyond the Heisenberg principle, classical statistical physics applies.

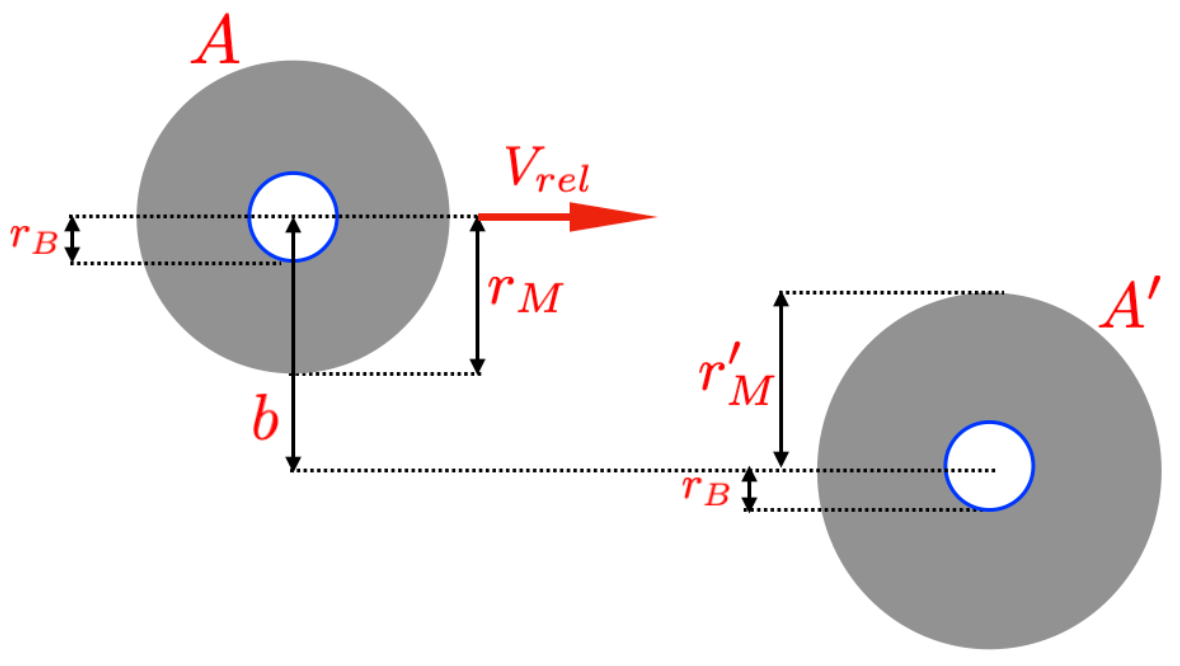

Note that these simplifications are frequently employed in classical scattering theory. Indeed, as a first approximation, choosing is reasonable for representing the effective interaction area of a molecule [36,37,38,39] (for a more detailed explanation, see [40]). Figure 1 shows the classical spherical model to represent molecules in nano-gases. In our heuristic model, the impact parameter b is twice that of Bohr’s radius, and all the molecules of the nano-gas are equal (so, , with denoting the molecular radius). The volume occupied by a molecule is .

Figure 1.

Collision between two molecules of a quasi-ideal nano-gas. The impact parameter b is the distance between the two centers of the molecules. In our heuristic model, the molecules are spherical and identical. The model assumes that if and the two molecules collide, they “feel” the Heisenberg principle. The limit case is reached when the distance between the two molecules is and the perfect packing is reached (i.e., ).

At thermal equilibrium, the (classical) uncertainty related to the measurement of the entropy production strength reads [40,41]

with denoting the collision time, T the temperature of the system, and the energy uncertainty of the classical system, respectively. In classical statistical mechanics, the equipartition theorem relates the temperature of a system to its average energies:

with and denoting the mean square speed and the molecule mass, respectively. The statistical theory of gases provides us with the expression of the collision time [42]:

where is the cross section. n and are the number of molecules for unit volume and the mean relative velocity, respectively. is linked to the root mean square speed by the relation [42]. If we do not make a distinction between the mean of the square and the square of the mean, we have [42]. (Reif’s approximation is often valid in kinetic theory due to symmetry and large particle numbers, but in mesoscopic thermodynamics, where fluctuations are significant, its validity must be carefully evaluated and cannot be assumed universally.) By combining all these expressions, we get

In Equation (43), we have taken into account the Heisenberg uncertainty principle:

with ℏ denoting the reduced Planck constant (). Here, and are the uncertainties related to time and energy measurements of the system, respectively. According to our (raw) model, molecules collide with each other with a minimal impact factor when

with denoting the packing fraction and the radius of the average molecule of the nanomaterial, respectively. A perfect packing corresponds to . The product decreases as the average distance between molecules becomes smaller. In the ideal case of perfect packing (), minimizing the average distance between molecules reduces the uncertainty in entropy production strength (), resulting in more predictable and consistent entropy production behavior due to the dense packing of molecules. Finally, we obtain a rough estimation of . Indeed,

with denoting the electron mass, c the speed of light, and the fine-structure constant, respectively. Note that although the mass of the electron appears in Equation (46), it plays no role since the product is independent of the mass of the electron. However, it is important from the physical point of view to put this quantity in evidence. From Equation (46), we get

where represents the relative size of the Bohr volume (volume of an atom based on the Bohr radius) to the volume occupied by a single molecule, and the ratio compares the mass of an electron to the mass of a molecule composing the material, respectively. Parameter denotes the Bohr/Molecular Ratio (BMR). A more accurate calculation that takes into account the imperfections in packing (e.g., due to thermal agitation or system size fluctuations) can be found in ref. [40]. The close packing fraction for spheres is known to be about for an idealized close-packed structure (like FCC (face-centered cubic) or HCP (hexagonal closest-packed) lattices). In this case, the expression for reads [40]

Notice that by defining a new operator , we get

where the constant appears as a universal number independent of the material.

Discussion

The Bohr radius is about meters. The diameter of molecules in nanomaterials can vary significantly. Our calculation assumed a perfect sphere for the molecule of nano-gas (which is not always the case). So, while the actual ratio might depend on the specific nano-gas, a molecular radius of the order meters and is a reasonable estimate for the order of magnitude [42,43]. So, is of the order of . As discussed before, the mass of molecules in nanomaterials can vary significantly. However, the mass is likely several thousand to millions of times heavier than an electron for many common molecules. Therefore, saying the ratio between the electron mass and an average molecule’s mass is about the electron-to-proton mass ratio captures the significant difference in scale between these two quantities. To determine the ratio between the mass of an electron and an average molecule in a system on a mesoscopic level, we need to consider the mass of the entire molecule, which includes the masses of all the atoms it contains, along with their constituent protons, neutrons, and electrons. The mass of an electron is approximately kilograms. A nanomaterial can be composed of a wide range of elements and have diverse molecular structures, so it is challenging to give a single specific ratio without knowing the exact composition of the nanomaterial. One example is graphene, a two-dimensional nanomaterial composed of a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice. For our purposes, it is reasonable to assume that –. Finally, the Bohr/Molecular Ratio is of the order of –. This suggests that the quantum effects described by the Bohr radius are not dominant on the mesoscopic scale and that classical physics can provide an adequate description of nano-gas behavior. Indeed, the following are true:

- (i)

- is proportional to the cube of the Bohr radius. At larger length scales, such as the mesoscopic level, the volume of interest () is significantly larger than the Bohr volume ().

- (ii)

- If the ratio is much smaller than unity, it suggests that the mass of the electron is negligible compared to the mass of the molecules. At the mesoscopic level, where we deal with large numbers of atoms and molecules, the mass of the molecules dominates, making the ratio very small.

- (iii)

- The BMR compares the scale of fundamental atomic properties (Bohr radius and electron mass) to the scale of molecular properties (molecular volume and mass). The smallness of indicates the disparity in scales between the atomic level and the molecular level. So, the result that the discretization constant is proportional to the ratio makes sense. This formulation effectively captures the disparity between atomic and molecular scales, providing a meaningful quantization of entropy production at the mesoscopic level. The use of fundamental constants and molecular properties supports the robustness of this result within the framework of mesoscopic thermodynamics.

By plugging the values , , and into Equation (47), we obtain , which aligns with the experimental value found in [27]: .

6. Conclusions

One of the main objectives of the Brussels School of Thermodynamics was to investigate systems on a mesoscopic scale to discover the fundamental laws governing them. In this work, inspired by this goal and encouraged by recent experimental results, we established the canonical commutation rules (CCRs) valid at the mesoscopic scale. The CCRs show that the closer we are to the mesoscopic level, the more indeterminate the simultaneous measurement of the canonically conjugate variables. For example, the uncertainties and in simultaneously existing values of the entropy production strength and time are related by the expression ; the greater the accuracy with which one of these quantities is measured, the less the accuracy with which the other can be measured at the same time. We have seen that fundamental quantities such as the total entropy production may be discretized at the mesoscopic scale. The ultraviolet divergence problem has been solved by applying the correspondence principle to Einstein–Prigogine’s fluctuations theory in the limit of macroscopic systems. Incidentally, we have also shown that the formalism based on the canonical commutation rules confirms the validity of the Onsager reciprocity relations over the entire linear region of thermodynamics. Successively, we address two crucial questions: (1) Is a universal constant? and (2) Does correspond to the lowest limit? To answer these questions, we investigated a very simple model for nano-gas that satisfies the laws of classical statistical physics. According to our heuristic model, the answer to the first question is “no”, and “yes” for the second one. Nonetheless, the value provided by the theoretical expression is very close to the experimental one found in ref. [27]. We conclude by mentioning that if multiple datasets or experimental trials for are available, a chi-squared test is useful to evaluate whether observed variations from predicted values fall within expected limits (for instance, refer to [44,45,46,47,48]).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data and numerical codes can be provided upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goldhaber-Gordon, D.; Göres, J.; Shtrikman, H.; Mahalu, D.; Meirav, U.; Kastner, M.A. The Kondo Effect in Single-Electron Transistors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 3, 156801. [Google Scholar]

- Beenakker, C.W.J.; van Houten, H. Quantum transport in semiconductor nanostructures. Solid State Phys. 1991, 44, 1–228. [Google Scholar]

- Baldo, M. Introduction to Nanoelectronics; MITOPENCOURSEWARE (MIT OCW), Lecture 5; MIT Education: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; Available online: https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/6-701-introduction-to-nanoelectronics-spring-2010/6a95133986a8698a55448d60c7834d15_MIT6_701S10_textbook.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2011).

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Jiang, D.; Katsnelson, M.I.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Dubonos, S.V.; Firsov, A.A. Two-dimensional gas of massless Dirac fermions in graphene. Nature 2005, 438, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balandin, A.A.; Ghosh, S.; Bao, W.; Calizo, I.; Teweldebrhan, D.; Miao, F.; Lau, C.N. Superior thermal conductivity of single-layer graphene. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 902–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collomb, D.; Li, P.; Bending, S.J. Nanoscale graphene Hall sensors for high-resolution ambient magnetic imaging. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Donder, T. Leçons de Thermodynamique et de Chimie-Physique; Gauthier-Villars: Paris, Italy, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- De Donder, T. L’ Affinité; Gauthier-Villars: Paris, Italy, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- De Donder, T. L’ Affinité (Volume 2); Gauthier-Villars: Paris, Italy, 1931. [Google Scholar]

- De Donder, T. L’ Affinité (Volume 3); Gauthier-Villars: Paris, Italy, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- De Donder, T.; Van Rysselberghe, P. Affinity; Stanford University Press: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, I. Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, I. Etude Thermodynamique des Phènomènes Irréversibles; Desoer: Liège, Belgium, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Glansdorff, P.; Prigogine, I. Sur les propriètès diffèrentielles de la production d’entropie. Physica 1954, 20, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigogine, I.; Hansen, R. Généralités sur l’introduction de grandeurs thermodynamiques dans l’expression des vitesses réactionnelles [Generalities on the introduction of thermodynamic quantities in the expression of reaction rates]. Bull. Cl. Sci. Acad. R. Belg. 1942, 28, 301. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, I. Remarque sur le principe de réciprocité d’Onsager et le couplage des réactions chimiques. Bull. Cl. Sci. Acad. R. Belg. 1976, 32, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Fitts, D. NonEquilibrium Thermodynamics. A Phenomenological Theory of Irreversible Processes in Fluid Systems; McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Gyarmati, I. Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, S.R.; Mazur, P. Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics; Dover Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Glansdorff, P.; Prigogine, I. Thermodynamic Theory of Structure, Stability and Fluctuations; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnino, G. Thermodynamic Field Theory (An Approach to Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes). In Instabilities and Nonequilibrium Structures IX. Nonlinear Phenomena and Complex Systems; Springer-Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001; Volume 9, pp. 291–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnino, G. A Field Theory Approach to Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes. HDR Habilitation Thesis, Institut Non Linèaire de Nice (I.N.L.N.), Nice, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnino, G. Nonlinear closure relations theory for transport processes in nonequilibrium systems. Phys. Rev. E 2009, 79, 051126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnino, G. Geometry and symmetry in non-equilibrium thermodynamic systems. Am. Inst. Phys. (AIP) Conf. Proc. 2019, 1853, 030002. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnino, G.; Evslin, J.; Sonnino, A.; Steinbrecher, G.; Tirapegui, E. Symmetry group and group representations associated with the thermodynamic covariance principle. Phys. Rev. E 2016, 94, 042103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnino, G. Thermodynamic Flux-Force Closure Relations for Systems out of the Onsager Region. In Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics and Fluctuation Kinetics. Modern Trends and Open Questions; Part of the book series: Fundamental Theories of Physics (FTPH); Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 208, p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Roldán, E.; Barral, J.; Martin, P.; Parrondo, J.M.R.; Jülicher, F. Quantifying entropy production in active fluctuations of the hair-cell bundle from time irreversibility and uncertainty relations. New J. Phys. 2021, 23, 083013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnino, G. Uncertainty relations in thermodynamics of irreversible processes on a mesoscopic scale. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostructures 2024, 164, 116058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchi, C.M. Second quantization. Scholarpedia 2010, 5, 7902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiani, L.; Benhar, O. Relativistic Quantum Mechanics: An Introduction to Relativistic Quantum Fields; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1498722308. [Google Scholar]

- Onsager, L. Reciprocal Relations in Irreversible Processes. I. Phys. Rev. 1931, 37, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsager, L. Reciprocal Relations in Irreversible Processes. II. Phys. Rev. 1931, 38, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.J. Introduction to Quantum Mechanics, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2004; ISBN 0-13-805326-X. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, S. Volume 1: Foundations. In The Quantum Theory of Fields, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A. Über die von der molekularkinetischen Theorie der Wärme geforderte Bewegung von in ruhenden Flüssigkeiten suspendierten Teilchen. Ann. Phys. 1905, 17, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, H.; Poole, C.P., Jr.; Safko, J.L. Classical Mechanics; Dorling Kindersley (India) Pvt. Ltd., Licensees of Pearson Education in South Asia: Noida, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai, J.J.; Napolitano, J. Modern Quantum Mechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hameka, H.F. Quantum Mechanics: A Conceptual Approach; Published Simultaneously in Canada; John Wiley & Son Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Tannoudji, C.; Diu, B.; Laloë, F. Vol. 2: Angular Momentum, Spin, and Approximation Methods. In Quantum Mechanics, 2nd ed.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnino, G. Exploring the Thermodynamic Uncertainty Constant: Insights from a Quasi-Ideal Nano-Gas Model. Entropy 2024, 26, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnino, G. An Attempt to Derive the Expression of the Constant in the Thermodynamic Uncertainty Relations by a Statistical Model for a Quasi-Ideal Nano-Gas. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.13435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reif, F. Fundamentals of Statistical and Thermal Physics; Waveland Press, Inc.: Long Grove, IL, USA, 1964; reissue 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kittel, C. Introduction to Solid State Physics, 8th ed.; John Wiley & Son, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bevington, P.R.; Robinson, D.K. Data Reduction and Error Analysis for the Physical Sciences; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Motulsky, H.J. Intuitive Biostatistics: A Nonmathematical Guide to Statistical Thinking; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, G. Statistical Data Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ruxton, G.D.; Neuhäuser, M. When should we use one-tailed and two-tailed tests? Methods Ecol. Evol. 2010, 1, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, L. Statistics for Nuclear and Particle Physicists; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).