Abstract

This study evaluated the effects of different UV-C radiation doses combined with modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) on the conservation of minimally processed grated anco squash. The squash, obtained from producers in Santiago del Estero (Argentina), was washed, sanitized, cut, peeled, grated, and centrifuged. It was then subjected to UV-C treatments of 5 kJ/m2 (T5), 15 kJ/m2 (T15), 30 kJ/m2 (T30), and 50 kJ/m2 (T50). An immersion treatment with NaClO (100 ppm, 3 min) (TH) and an untreated control (TC) were also included. All samples were packaged in PVC trays and sealed with 35 μm polypropylene film, forming a passive MAP. Treatments T5 and T15 preserved acceptable sensory quality for up to 8 days, and no significant differences in color parameters were observed among treatments during storage. Overall, PC decreased by 12–20% and C by 15–37%, while AC increased by 15–40% after 8 days. Treatments T15, T30, and T50 effectively reduced psychrophilic microorganisms for up to 4 days, achieving reductions of 1–2 log compared to TH and TC (6 log CFU/g). By day 8, all treatments reached the microbial limit. In conclusion, the T15 treatment was the most suitable for preserving grated anco squash for up to 4 days at 5 °C, offering a potential alternative to sodium hypochlorite–based sanitization.

1. Introduction

Pumpkins (Curcubita moschata) are generally sold whole and fresh. Another alternative would be minimally processed pumpkins, also known as fresh-cut vegetables, which are classified as ready to eat or ready to cook [1].

Driven by the need to incorporate healthier and more nutritious foods and by changing consumer habits, demand for fresh-cut vegetables has increased significantly [2]. However, it is imperative to note that the processes involved in preparing the raw material, such as fragmentation and cutting, induce structural alterations in the tissues that promote rapid deterioration [3]. Consequently, these physical injuries can manifest as a decrease in nutritional compounds, tissue softening, the development of microbial flora, and enzymatic browning reactions, negatively impacting both their shelf life and commercial viability [4,5]. Therefore, extending the shelf life of fresh products through the implementation of various preservation technologies is a highly strategic alternative for corporate entities in the sector [6]. In order to preserve the organoleptic properties of fresh products and mitigate microbiological proliferation, it is feasible to resort to the application of emerging methodologies, which operate as viable substitutes for conventional procedures [7].

Evidence from technological advances indicates that the application of ultraviolet (UV) radiation can reduce the rate of deterioration in fruits and vegetables, thereby contributing to the extension of their marketing period [8,9]. In addition, several specialists argue that UV-C light is a viable substitute for chemical-based sterilization methods. This is due to its ability to inhibit microbial growth on the surface of minimally processed vegetables without adversely affecting their quality. Examples of its application include products such as tomatoes, peppers, apples, watermelons, and edible mushrooms [8,9,10]. Additionally, research has shown that exposure to low doses of UV-C radiation can stimulate the biosynthesis of phytoalexins as part of a defensive response in plants, resulting in increased production of phytochemicals with notable antioxidant capacity, such as phenolic compounds and vitamin C [8,11]. This phenomenon has been documented in various fruit species, including bananas, guavas, and pineapples [11], as well as mandarins [12].

To date, there are no documented reports on the impact of UV-C radiation on the overall quality of minimally processed grated pumpkin. Consequently, it was determined that it was important to evaluate different doses of UV-C radiation and characterize the responses induced in specific quality parameters. This evaluation focuses on the sensory, microbiological, and bioactive properties of grated anco squash, specifically that produced in the province of Santiago del Estero, Argentina.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation and Treatments

The pumpkins (Cucurbita moschata, cv. Anco) were sourced from growers in Santiago del Estero, Argentina, at commercial maturity. They were washed and sanitized using chlorinated water (150 ppm for 5 min). After draining, the pumpkins were manually peeled with a sharp knife, sliced, and cut into smaller portions of appropriate size to fit into the food processor feed opening (5 cm diameter), with seeds removed while maintaining proper good manufacturing practices. They were then grated using a food processor. Subsequently, UV-C radiation (254 nm) doses of 5 kJ/m2 (T5), 15 kJ/m2 (T15), 30 kJ/m2 (T30), and 50 kJ/m2 (T50) were applied. An immersion treatment in 100 ppm NaClO for 3 min (TH) and an untreated control (TC) were also included.

Finally, the samples were packaged in PVC trays and sealed with 35 μm thick polypropylene film containing a normal atmospheric gas composition (passive MAP). Samples were stored at a constant temperature of 5 °C for a total period of 8 days. Sensory, microbiological, and bioactive compound evaluations were performed at predefined storage times (days 1, 4, and 8) [13].

2.2. UV-C Radiation Equipment

Grated anco squash were exposed to UV irradiation in a stainless-steel chamber following the procedure described by Gutiérrez et al. [14]. The chamber contained 12 germicidal lamps (254.7 nm, TUV 36W/G36, Philips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) arranged evenly above and below the samples. Light intensity was maintained at a constant level (0.017 kW m−2), and the delivered dose was monitored using a portable digital radiometer (Cole-Parmer Instrument Company, Vernon Hill, IL, USA).

2.3. Sensory Analysis

Sensory evaluation was conducted on storage Days 1, 4 and 8 by a panel of 12 trained assessors aged between 23 and 61 years. The samples were identified with three-digit random codes and presented to the assessors, who carried out their evaluations independently. Each attribute was scored on a 1-to-9 scale, where 9 represented the best quality, 1 the poorest, and 5 the threshold for market acceptability [14,15]. Six attributes were assessed: overall visual appearance, color, aroma, exudate presence, tactile wetness and flavor, with overall visual appearance and flavor being the key factors influencing judges’ acceptance [13].

2.4. Color

The surface color of grated carrots was determined by measuring the color parameters L*, a*, and b* in CIE LAB space with a tri-stimulus colorimeter (Minolta CR 300, Ramsey, NJ, USA), with a viewing aperture of 8 mm diameter, D65 illuminant and observation angle of 0°, previously calibrated using the manufacturer’s standard white plate. Color parameters were expressed as lightness (L*), chroma (C*) and hue angle (h°). The hue angle [(h° = 180 + tan−1(b*/a*)] and the values of chroma [C* = (a*2 + b*2)1/2] were calculated from a* and b* values [16].

2.5. Methodology Used for Microbiology

All treatments were analyzed at 1, 4 and 8 days after storage. Microbiological analyses were conducted in a laminar flow chamber. Counts were performed for mesophilic aerobic bacteria (MA) and psychrophilic aerobic bacteria (Psy). MA and Psy were grown on PCA (plate count agar) at 37 °C for 48 h and 5 °C for 7 days, respectively [17]. Counts were obtained from three samples per treatment, in triplicate, across two independent experiments, expressed as log CFU/g.

2.6. Total Phenol Content

The extraction was performed according to the procedure described by Gutiérrez et al. [18] with minor modifications. These extracts were used for the determination of antioxidant capacity and total phenolic content. The total phenolic content in grated AS subjected to different essential oil treatments was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu method, based on a spectrophotometric measurement of a colorimetric redox reaction [19]. Absorbance was measured in triplicate at 750 nm using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (JASCO V-630, Tokyo, Japan). Total phenolic content was expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per g of fresh tissue (FT) using the corresponding calibration curve. The gallic acid standard solution used had a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL.

2.7. Antioxidant Capacity

Total antioxidant capacity was determined based on the evaluation of free radical scavenging capacity according to the methodology of Ozgen et al. [20], using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH) of absorbance ≈ 1.1. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 515 nm and the antioxidant capacity was expressed as percentage: %INH = (blank absorbance − absorbance Sample/blank absorbance) × 100.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data were evaluated through Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) using software InfoStat version [2011] (InfoStat Group, National University of Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina).All assays were conducted in triplicate, and mean values were compared using the least significant difference (LSD) test at a 0.05 significance level.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sensory Evaluation

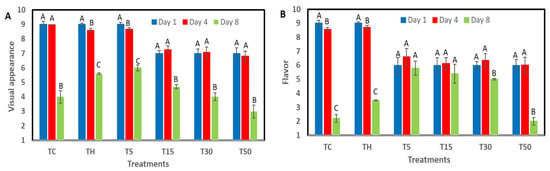

The results obtained in sensory evaluation are shown in Figure 1. The results shown in Figure 1A indicate that the scores progressively decreased during storage for all treatments. Up to day 4, the overall appearance of samples TC, TH, and T5 showed higher evaluations on the hedonic scale: 9 or close to 9 depending on the treatment, while samples T15, T30, and T50 showed evaluations close to 7. On the other hand, significant differences (p < 0.05) were found between the different treatments after 8 days of storage. Considering that a mean score of 5 on the scale is considered the limit of acceptability where the product is commercially acceptable, the samples that meet this criterion at the end of storage were TH and T5, with scores of 5.5 and 6, respectively.

Figure 1.

Overall visual appearance (A) and Flavor (B) attributes in grated pumpkin without treatment (TC), immersed in sodium hypochlorite (TH) and through the application of different UV-C methodologies at 1, 4 and 8 days of storage at 5 °C. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Different letters in each treatment represent significant differences at p < 0.05 according to the LSD test.

Flavor scores declined over storage across all treatments, although the extent of deterioration varied notably among them. As shown in Figure 1B, the control (TC) exhibited a rapid decline in sensory quality, falling below acceptable levels by day 8, as did the TH treatment. In contrast, treatments T5, T15 and T30 maintained acceptable values until day 8. The highest UV-C dose (T50) showed inconsistent performance, with notably low scores at the end of storage.

Overall, T5 was the most effective treatment for preserving both aroma and flavor during prolonged storage, while T15 maintained acceptable sensory levels until day 4.

3.2. Effect of UV-C on the Color Parameters (L*, C*, hue°)

Color is one of the most important quality attributes, and one that the consumer considers when making purchase [21]. L* parameter color and C* and hue° indices are shown in Table 1. Color results indicated that no significant differences were found between different treatments. No color results were found in works on UV-C-treated grated pumpkin by other authors. Previous studies applying similar UV-C doses to shredded carrots (Daucus carota) of the Chantenay variety also reported no significant differences among treatments. These findings support the notion that, under certain conditions, UV-C exposure may have limited impact on the measured quality parameters [22].

Table 1.

L* parameter color, C* and hue° indices of grated pumpkin of Curcubita moschata variety untreated (TC), sanitized (TH) treated with different doses of UV-C radiation and stored at 5 °C for 8 days after UV-C radiation.

3.3. Effect of UV-C on the Native Microflora of Grated Pumpkin

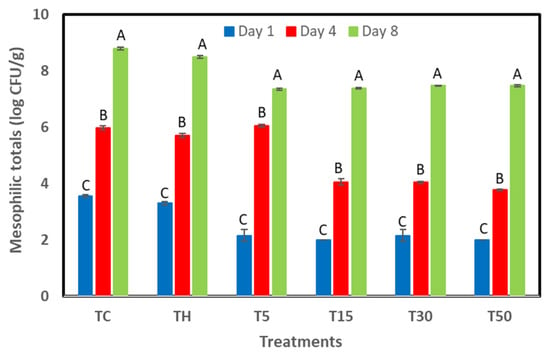

The microbial counts of MA are presented in Figure 2. MA counts increased progressively during storage for all treatments. By Day 8, the untreated control (TC) and TH reached the highest values (≈8.5–8.8 log CFU/g), showing the fastest microbial growth. Although all UV-C treatments also showed substantial increases over time, T5, T15, T30, and T50 exhibited only slightly lower counts than the controls on Day 8, indicating that the treatments slowed—but did not strongly inhibit—microbial proliferation. Overall, UV-C treatments delayed microbial growth to some extent, but none were able to prevent the significant increase in mesophilic bacteria by the end of storage.

Figure 2.

Microbial counts on mesophilic aerobic bacteria (MA) in grated pumpkin without treatment (TC), immersed in sodium hypochlorite (TH), and subjected to different doses of UV-C after 1, 4 and 8 days of storage at 5 °C. Data are presented as log CFU/g. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Different letters in each treatment represent significant differences at p < 0.05 according to the LSD test.

Previous research using irradiation periods of 20 min (≈11.2 kJ/m2) in fresh-cut apple slices documented reductions between 1 and 1.9 log cycles for inoculated microorganisms such as Listeria innocua, Escherichia coli, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In the same study, native microflora—including mesophilic aerobes, yeasts, and molds—showed approximately 1.8-log reductions at 11.2 kJ/m2, and UV-C treatment improved microbial safety and inhibited microbial growth during refrigerated storage up to Day 7 [23]. These discrepancies suggest that the UV-C doses applied to squash pumpkin, although capable of delaying microbial proliferation, were insufficient to induce sustained or substantial inactivation.

3.4. Effect of UV-C on the Bioactive Compounds of Grated Pumpkin

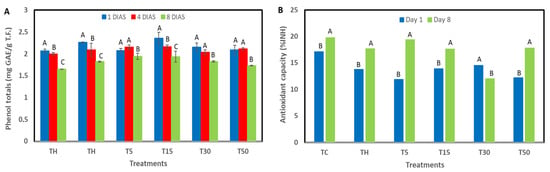

The PC content showed a decreasing trend across all treatments during the 8-day storage period (Figure 3). In the TC and TH, phenolic levels declined from 2.07–2.26 mg GAE g−1 to 1.65–1.82 mg GAE g−1 by day 8, corresponding to reductions of approximately 19–20%. Similar decreases were observed in treatments T15, T30 and T50, which exhibited phenolic losses of 17.95%, 15.23% and 17.26%, respectively. In contrast, treatment T5 demonstrated the highest stability of phenolic compounds throughout storage. Values increased slightly from day 1 (2.08 mg GAE g−1) to day 4 (2.15 mg GAE g−1), followed by a moderate decline to 1.94 mg GAE g−1 at day 8. This represented only a 6.58% reduction, the lowest among all treatments (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Phenolic compounds (A) and antioxidant capacity (B) of grated pumpkin without treatment (TC), immersed in sodium hypochlorite (TH), and subjected to different doses of UV-C after 1, 4 and 8 days of storage at 5 °C. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Different letters in each treatment represent significant differences at p < 0.05 according to the LSD test.

Similar responses have been reported in tomato fruit following UV-C exposure. Previous studies demonstrated that UV-C treatment can lead to a significant reduction in total phenolic compounds, particularly in tissues directly exposed to radiation, such as the peel. In tomatoes, higher UV-C doses resulted in marked decreases in total phenolics and in specific compounds such as chlorogenic acid, suggesting that excessive oxidative stress may accelerate phenolic degradation rather than stimulate their accumulation [24].

These findings support the hypothesis that UV-C radiation does not universally enhance phenolic content and that its effect depends on both dose and tissue sensitivity. In this context, the decrease observed in grated pumpkin phenolics may be attributed to UV-C-induced oxidative processes and the subsequent degradation of phenolic compounds during storage, a behavior consistent with that reported for tomato fruit.

Figure 3B presents the temporal evolution of %INH for each treatment, revealing a clear upward trend during refrigerated storage. During storage, %INH values showed a progressive increase across all treatments, including the control. Inhibition levels, which initially ranged between approximately 12–17%, later reached values close to 17–19% as storage progressed. Consistent with this trend, the relative increase in inhibitory activity varied among treatments, with rises of about 13% in TC, 22% in TH, 38% in T5, 21% in T15, and 31% in T50. Although UV-C exposure is generally associated with the induction of antioxidant-related metabolites, the comparable upward shifts observed across treatments suggest that storage-driven physiological responses played a predominant role in enhancing inhibitory capacity. Such responses may reflect the stress-induced accumulation of phenolic compounds or other antioxidant constituents during refrigerated storage.

In strawberries, previous studies show that UV-C enhances antioxidant capacity both at time zero and during refrigerated storage, with treated fruit maintaining higher ABTS+ and DPPH inhibition than controls despite the natural decline over time. This improvement is often associated with increased anthocyanin accumulation, even when total phenolics remain unchanged [25]. Overall, these results demonstrate that UV-C can stimulate antioxidant defenses, but the magnitude depends strongly on dose and fruit characteristics. Thus, optimizing UV-C exposure is essential to maximize postharvest benefits in each type of produce.

4. Conclusions

This study assessed the effect of UV-C radiation at different doses, combined with passive modified atmosphere packaging (MAP), on the quality and shelf-life of minimally processed grated pumpkin squash (Cucurbita moschata). Sensory evaluation showed that low UV-C doses (T5 and T15) maintained acceptable quality up to Day 8, with T15 being the most suitable for preserving aroma and flavor during the first 4 days of storage at 5 °C. Color parameters were not significantly affected by the treatments. Microbiologically, all treatments reached the acceptable microbial limit by Day 8. Bioactive compounds showed divergent behavior: antioxidant capacity increased by 15–40% and phenolic content decreased by 12–20% (with T5 showing the greatest stability). Overall, T15 combined with passive MAP and refrigeration emerged as the most effective strategy for maintaining quality and ensuring microbial safety for up to 4 days. These findings support UV-C radiation as a complementary tool to refrigeration and MAP for modestly extending the shelf-life of minimally processed vegetables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F.B., D.R.G., S.C.R. and S.d.C.R.; methodology, J.F.B., D.R.G., S.C.R. and S.d.C.R.; research and data analysis, J.F.B., S.C.R., D.R.G. and S.d.C.R.; writing: preparation of original draft, D.R.G., S.C.R. and J.F.B.;, J.F.B., D.R.G., S.C.R. and S.d.C.R.; supervision, S.d.C.R.; project management, S.d.C.R.; procurement of funds, S.d.C.R. and D.R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from project 23/A311-A-2024, awarded by the Scientific and Technological Research Council (CICyT) of the National University of Santiago del Estero, and from Project PUE0051 of the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research, Argentina.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out at the Faculty of Agronomy and Agroindustry of the National University of Santiago del Estero and the Research Center in Applied Biophysics and Food National Council for Scientific and Technical Research, Argentina.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lucera, A.; Costa, C.; Mastromatteo, M.; Conte, A.; Del Nobile, M.A. Influence of Different Packaging Systems on Fresh-Cut Zucchini (Cucurbita pepo). Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2010, 11, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hu, W.; He, Y.; Jiang, A.; Zhang, R. Effect of Citric Acid Combined with UV-C on the Quality of Fresh-Cut Apples. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 111, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Abadias, M.; Usall, J.; Torres, R.; Teixidó, N.; Viñas, I. Application of Modified Atmosphere Packaging as a Safety Approach to Fresh-Cut Fruits and Vegetables—A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 46, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, G.A.; Gallone, A.; Nychas, G.J.; Sofos, J.N.; Colelli, G.; Amodio, M.L.; Spano, G. Factors Affecting Quality and Safety of Fresh-Cut Produce. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 52, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Ge, Z.; Limwachiranon, J.; Li, L.; Li, W.; Luo, Z. UV-C Treatment Affects Browning and Starch Metabolism of Minimally Processed Lily Bulb. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2017, 128, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzocco, L.; Da Pieve, S.; Bertolini, A.; Bartolomeoli, I.; Maifreni, M.; Vianello, A.; Nicoli, M.C. Surface Decontamination of Fresh-Cut Apple by UV-C Light Exposure: Effects on Structure, Colour and Sensory Properties. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2011, 61, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lante, A.; Tinello, F.; Nicoletto, M. UV-A Light Treatment for Controlling Enzymatic Browning of Fresh-Cut Fruits. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 34, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetuyi, F.O.; Karigidi, K.O.; Akintimehin, E.S. Effect of Postharvest UV-C Treatments on the Bioactive Components, Antioxidant and Inhibitory Properties of Clerodendrum volubile Leaves. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2020, 19, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, C.; João, C.; Bartolommeo, A. Prospects of UV Radiation for Application in Postharvest Technology. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2012, 24, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.T.; Lasekan, O.; Adzahan, N.M.; Hashim, N. The Effect of Combinations of UV-C Exposure with Ascorbate and Calcium Chloride Dips on the Enzymatic Activities and Total Phenolic Content of Minimally Processed Yam Slices. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 120, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alothman, M.; Bhat, R.; Karim, A.A. UV Radiation-Induced Changes of Antioxidant Capacity of Fresh-Cut Tropical Fruits. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2009, 10, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Qiao, L.; Chen, J.; Liu, D.; Ye, X. Effect of UV-C Treatments on Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity of Minimally Processed Satsuma Mandarin during Refrigerated Storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 76, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benites, J.F.; Gutiérrez, D.R.; Ruiz, S.C.; Rodríguez, S.D.C. Influence of the Application of Rosemary Essential Oil (Salvia rosmarinus) on the Sensory Characteristics and Microbiological Quality of Minimally Processed Pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata). Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2024, 40, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, D.R.; Chaves, A.R.; Rodríguez, S.D.C. Use of UV-C and gaseous ozone as sanitizing agents for keeping the quality of fresh-cut rocket (Eruca sativa mill.). J. Food Proc. Preserv. 2016, 41, e12968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, S.C.; Gutiérrez, D.R.; Torales, A.C.; Qüesta, A.G. Vegetales IV Gama: Producción, Comercialización y Aspectos Sanitarios en la Región NOA y Argentina. In Aportes de la Faya Para el Desarrollo Agropecuario y Agroindustrial del NOA; Facultad de Agronomía y Agroindustrias, Universidad Nacional de Santiago del Estero (FAyA–UNSE): Santiago del Estero, Argentina, 2017; Volume 11, pp. 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Koukounaras, A.; Siomos, A.S.; Sfakiotakis, E. Postharvest CO2 and ethylene production and quality of rocket (Eruca sativa Mill.) leaves as affected by leaf age and storage temperature. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2007, 46, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICMSF (International Commission on Microbiological Specifications for Foods). Microbial Ecology of Foods, 2nd ed.; Food Products; Acribia: Zaragoza, Spain, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, D.R.; Char, C.; Escalona, V.H.; Chaves, A.R.; Rodríguez, S.D.C. Application of UV-C radiation in the conservation of minimally processed rocket (Eruca sativa Mill.). J. Food Process. Preserv. 2015, 39, 3117–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of total phenols oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin–Ciocalteau reagent. Method Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–153. [Google Scholar]

- Ozgen, M.; Reese, R.N.; Tulio, A.Z.; Scheerens, J.C.; Miller, A.R. Modified 2, 2-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) method to measure antioxidant capacity of selected small fruits and comparison to ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) and 2, 2 ‘-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) methods. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canacuan, H.G.C.; Valencia Murillo, B.L.; Ordóñez Santos, L.E. Efectos de los tratamientos térmicos en la concentración de vitamina C y color superficial en tres frutas tropicales. Rev. Lasallista Invest. 2016, 13, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, D.R.; Ruiz, S.C.; Benites, J.F.; Rodriguez, S.d.C. Innovative Technologies to Increase Bioactive Compounds in Carrots of the Chantenay Variety. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2024, 40, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, P.L. Minimal Processing of Apple: Effect of UV-C Radiation and High-Intensity Pulsed Light on Quality. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Buenos Aires, Faculty of Exact and Natural Sciences, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2010. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12110/tesis_n4603_Gomez (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Sanchez, R.D. Determinación de Compuestos Fenólicos en Tomates. Bachelor’s Thesis, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales y Agrimensura, Universidad Nacional del Nordeste, Corrientes, Argentina, 2022. Available online: https://repositorio.unne.edu.ar/bitstream/handle/123456789/56463/RIUNNE_FACENA_TFA_Sanchez_RD.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 2 January 2026).

- Li, M.; Li, X.; Han, C.; Ji, N.; Jin, P.; Zheng, Y. UV-C treatment maintains quality and enhances antioxidant capacity of fresh-cut strawberries. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 156, 110945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.