Abstract

A study was conducted on the fruit storage (0, 2, 4, and 6 days) of bitter gourd (half-ripe stage) under ambient conditions (temperature: 28 ± 2 °C and relative humidity: 65 ± 5%). It was conducted to evaluate the impact of fruit storage on the enhancement of bitter gourd’s seedling vigor. Four days of fruit storage significantly improved the seedling vigor index (SVI), and beyond this period, did not contribute to a higher SVI. It produced better growth for shoot, root, and seedling lengths as compared to lower and higher periods, as well as unstored fruits. Moreover, a higher root count per seedling and seedling fresh weight were observed in 4-day fruit storage. Conversely, 6-day fruit storage exhibited a higher chlorophyll content (SPAD index) as compared to shorter storage periods and unstored fruits. A 4-day fruit-storage period may be recommended to the farmers to obtain vigorous bitter gourd seedlings.

1. Introduction

Momordica charantia, or locally known as ampalaya or bitter gourd, is an essential fruit vegetable from the Cucurbitaceae family. Bitter gourd offers numerous health benefits, such as anti-diabetic activity, anti-cancer and antioxidative properties, and anti-microbial activity [1,2]. It was reported that the charantin in bitter gourd is a potential antidiabetic substance [3,4]. Likewise, the fruits are naturally rich in β-carotene, zeaxanthin, and lycopene in the ripe stage, and lutein and α-carotene in the immature stage [5]. They have reported that bitter gourds are also rich in minerals (phosphorus, potassium, manganese, zinc, and iron) and vitamin C.

Central Luzon (26,654.08 MT) outperformed the other regions in the Philippines, and it is the top producer of bitter gourd. However, the production of bitter gourd in Region I in 2022 reached 10,831.42 metric tons (MT), an increase of 4.15% compared to 2021 (10,400.11 MT). It indicates that there may be an increase in demand due to its nutritional benefits and a higher nutritional value than the other cucurbit crops [1]. The percentage distribution of bitter gourd by province in Ilocos Region is as follows: Ilocos Norte: 32.04%, Ilocos Sur: 24.05%, Pangasinan: 23.98%, and La Union: 19.93% [6].

Therefore, to sustain the demand for bitter gourd, planting material is needed to sustain production. Quality seed or planting materials play a pivotal role in crop production as they interact with the environment. However, due to adverse conditions, seed quality is affected. Fruit storage can mitigate this issue to attain the physiological maturity of the seeds, but the period must be considered, as it may produce low or high vigor. Previously, fruit storage or postharvest ripening for 6 days exhibited taller seedlings, longer roots, wider stem diameter, and higher fresh and dry weights of seedlings [7]. In another study, 10 days of storage displayed a higher germination and seed weight [8]. Fruit storage may provide the seeds with the necessary conditions to develop and attain physiological maturity, resulting in maximum dry weight and germination [9]. This was not always the case, wherein it did not apply to other crops, such as soybean, tomato, and bell peppers [10,11,12]. Due to physiological maturity attained by fruit storage, a high germination with better seedling vigor where the seed-filling stage has ended [13]. It indicates that fruit storage plays a pivotal role in providing nutrition to the seed development. This scientific information, although it is not new in the locality, provides a scientific basis for how the fruit storage of bitter gourd affects the seedling vigor. Thus, this study was conducted to determine the influence of fruit storage on germination and seedling vigor of bitter gourd.

2. Materials and Methods

Half-ripe (50% green and 50% yellow-orange pulp colors) Ilocos Green fruits (20 fruits per treatment per replication) were purchased from the bitter gourd growers in the City of Batac, Ilocos Norte. The fruits were stored under ambient conditions for 2, 4, and 6 days. There was no decay yet on the 6th day, but beyond this fruit storage period, fruit rot has been observed. Hence, the study only used up to 6 days of fruit storage. The average temperature and relative humidity recorded were 28 ± 2 °C and 65 ± 5%, respectively. The seeds of the unstored fruits were immediately extracted. Likewise, after fruit storage, the seeds were also extracted. The seeds were air-dried until the moisture content became stable. Fruit storage period up to 6 days was performed because the fruits had already started splitting at 2 days. In a real scenario, if the split fruits are left in the field, infestation of pests will occur, and seeds will scatter in the soil.

Germination percentage, germination index, and mean germination time (MGT) were measured using the method of ISTA [14]. The germination index and MGT were counted for 14 days. At 4 and 14 days after sowing (DAS), shoot and root lengths, and root count per seedling were measured. The sum of shoot and root length was used for the seedling length. Chlorophyll content of the leaves was measured using a SPAD meter and measured at 14 DAS. Whereas for the seedling vigor index, it was measured using the formula (germination percentage x seedling length (cm).

3. Results

3.1. Germination Percentage and Germination Index

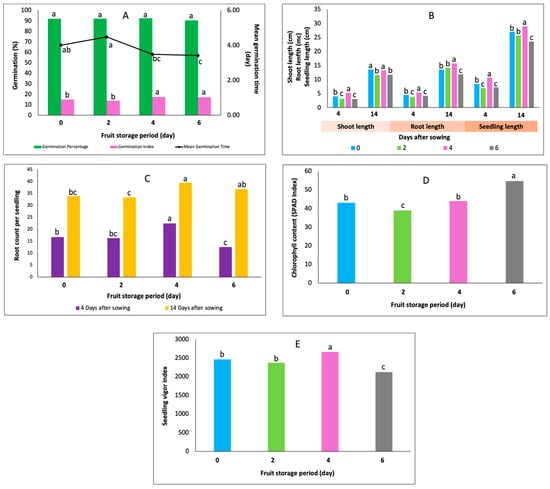

Fruit storage did not influence the germination percentage of bitter gourd (Figure 1A). However, the germination index was improved by fruit storage. Longer fruit storage periods of 4 and 6 days produced a higher germination index than a shorter storage period.

Figure 1.

(A) The germination, germination index, mean germination time, (B) shoot, root, and seedling lengths, (C) root count per seedling, (D) chlorophyll content, (E) seedling vigor index of bitter gourd after fruit storage. Blue, green, pink, and gray bars indicate 0, 2, 4, and 6 days of fruit storage, respectively. Bars with different lowercase letters indicate a significant difference among fruit storage periods.

3.2. Mean Germination Time (MGT)

A decreasing trend of the MGT as the fruit storage progressed was observed (Figure 1A). But the lowest MGT was evident in 4 days of fruit storage, and no further decrease in MGT occurred at 6 days.

3.3. Shoot, Root, and Seedling Lengths

At 4 DAS, longer shoots and roots were observed in 4 days of fruit storage. Beyond this storage period, the shoots and roots became shorter. At 14 DAS, long shoots were produced from unstored and 4 days of storage, which was higher than the other storage periods (Figure 1B). However, the root length showed a different pattern, with 4 days of fruit storage producing the longest roots. It was observed that root length increased from 0 to 4 days but declined at 6 days.

However, longer seedlings were produced from the fruits stored for 4 days at 4 and 14 DAS. A decline in seedling length was evident beyond this storage period.

3.4. Root Count per Seedling

It was observed that from 0 to 4 days of storage, an increasing pattern of root count was observed. Fruit storage of 4 days exhibited a higher root count per seedling, but longer than this storage period, it did not produce more root count (Figure 1C). Fruit storage may have played an essential role in the production of roots, as per the results of the study.

3.5. Chlorophyll Content

A longer fruit storage period, specifically 6 days, produced the highest chlorophyll content based on the SPAD index (Figure 1D). A visible increase in chlorophyll content from 2 to 6 days was observed.

3.6. Seedling Vigor Index

Vigorous seedlings were produced from fruits stored for 4 days, which were vigorous than a shorter or longer storage period (Figure 1E). A gradual increase in seedling vigor index was observed from 3 to 4 days, but it declined at 6 days of storage.

4. Discussion

Fruit storage offers a temporary seed storage for fruit vegetables, such as bitter gourd. This strategy provides the seed to develop, mature, and reach its physiological maturity (PM). The PM in seeds reaches its maximum dry weight and is considered fully developed [15]. PM is part of the seed development process of the seed maturation, and there are three stages: Stage 1 refers to the formation of embryonic tissues, Stage II is the increase in the seed dry weight due to the accumulation of storage reserves, and PM is attained at the latter of this stage, and Stage III is the decrease in seed dry matter as it reaches the mature form or this is the stage of maturation drying and maximum germination and vigor [16,17]. PM sometimes coincides with the maximum germination, but this is not always the case due to species-dependent [18]. If PM is applied to the study, the seed weight (0.0087–0.0092 g) of bitter gourd across storage periods (0 to 6 days) had no significant variation because neither an increase nor a decrease was observed. It indicates that at the half-ripe stage of bitter gourd fruits, even without storage, PM has been reached, and the germination percentage of unstored and stored fruits was similar. This observation did not apply to tomato [10], soybean [12], and bell pepper [11]. It indicates that PM will not be applicable to claim that it will produce maximum germination due to species variations.

However, vigorous seedlings were attained by fruit storage as compared to unstored fruits (Figure 1E). A fruit storage period of 4 days was enough to produce vigorous seedlings of bitter gourd because of its higher seedling vigor index than the unstored, 2, and 6 days of storage. Therefore, it can be recommended to bitter gourd growers with the practice of fruit storage using 4 days due to the vigorous seedlings, with a comparable germination percentage to the unstored and other storage periods. Moreover, vigorous characteristics were observed in this storage period, such as a higher germination index with faster germination of seeds, as aligned with its low mean germination time. The lower the MGT, the faster the germination of seeds in a short period. Nevertheless, 4 and 6 days of fruit storage showed no differences. This indicates that beyond 4 days of fruit storage did not significantly improve the germination index. Likewise, the suitable fruit storage period with a higher germination index was 4 days. Furthermore, this period produced longer seedlings at 4 and 14 DAS, owing to its long shoots and roots. Results signify that 4-day fruit storage enhanced the elongation of roots and shoots, resulting in longer seedlings. It was reported that shoot and root elongation are stimulated by gibberellins [19]. This means that the seeds in fruits stored for 4 days may have high amounts of gibberellins that produce longer seedlings. In another aspect, a previous report showed that a low concentration of abscisic acid (ABA) promotes shoot elongation but inhibits root elongation [20]. However, a further study on the concentration of gibberellin and ABA in bitter gourd is recommended. A previous study reported root elongation, resulting in longer roots, with fruit storage [7].

Additionally, a 4-day fruit storage exhibited seedlings with a higher root count (Figure 1C). There was an increase in the root count from 0 to 4 days, but it declined at 6 days. The increase in the root count from 0 to 4, and a maximum at 4 days of fruit storage, may be due to the effect of auxin that promotes root development, resulting in a higher root count. The amount of auxin in this fruit storage period may be higher as compared to the lower period. Sosnowski et al. [21] reported that auxin is synthesized in seeds, young leaves, and fruits, and auxin initiates the production of roots.

5. Conclusions

Fruit storage, specifically 4 days, provides a higher germination index and lower mean germination time. Moreover, this storage period produced vigorous seedlings owing to its comparable germination percentage and longer seedlings than the other storage period. Further studies on the plant hormones that affect the seed germination and seedling vigor are needed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D., M.B.G.-B. and R.J.R.; Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.D. and R.J.R.; Formal Analysis, Writing—Review and Editing, R.J.R., C.B.A.B., G.F.P. and M.B.G.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Mariano Marcos State University for supporting the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gayathry, K.; John, J. A comprehensive review on bitter gourd (Momordica charantia L.) as a gold mine of functional bioactive components for therapeutic foods. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2022, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, B.; Jini, D. Antidiabetic effects of Momordica charantia (bitter melon) and its medicinal potency. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2013, 3, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Patel, T.; Parmar, K.; Bhatt, Y.; Patel, Y.; Patel, N. Isolation, characterization and antimicrobial activity of charantin from Momordica charantia Linn. Int. J. Drug Discov. 2010, 2, 629–634. [Google Scholar]

- Krawinkel, M.; Keding, G. Bitter gourd (Momordica charantia): A dietary approach to hyperglycemia. Nutr. Rev. 2006, 64, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jat, G.; Behera, T.; Singh, A.; Bana, R.; Singh, D.; Godara, S.; Redyy, U.; Rao, P.; Ram, H.; Vinay, N.; et al. Antioxidant activities, dietary nutrients, and yield potential of bitter gourd (Momordica charantia L.) lines in diverse growing environments. Front. Nutr. 2025, 11, 1393476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippine Statistics Authority. 2022 Volume of Bitter Gourd Production. Available online: https://rsso01.psa.gov.ph/statistics/crps/node/1684057132 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Murrinie, E.; Yudono, P.; Purwantoro, A.; Sulistyanighsih, E. Effect of fruit age and post-harvest maturation storage on germination and seedling vigor of wood apple (Feronia limonia L. Swingle). Asian J. Agric. Biol. 2019, 7, 196–204. [Google Scholar]

- Takac, A.; Popovic, V.; Glogovac, S.; Dokic, V.; Kovac, D. Effects of fruit maturity stages and seed extraction time of the seed quality of eggplant Solanum melongena L.). Ratar. Povrt. 2015, 52, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tetteh, R.; Aboagye, L.; Boateng, S.; Darko, R. Seed quality of six eggplant cultivars as influenced by harvesting time. J. Appl. Hortic. 2021, 23, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, S.; Silva, P.; Araujo, F.; Souza, F.; Nascimento, W. Tomato seed image analysis during the maturation. J. Seed Sci. 2019, 41, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.; Parera, C. Effect of harvesting time on seed quality of two bell pepper cultivars (Capsicum annuum). Rev. Fac. Cienc. Agrar. 2017, 49, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zanakis, G.; Ellis, R.; Summerfield, R. Seed quality in relation to seed development and maturation in three development and maturation in three genotypes of soyabean (Glycine max). Exp. Agric. 1994, 30, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welbaum, G. Cucurbit seed development and production. Hort. Tech. 1999, 9, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Seed Testing Association. International Rules for Seed Testing Edition; The Iternational Seed Testing Association: Basserdorf, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sripathy, K.; Groot, S. Seed development and maturation. In Seed Science and Technology: Biology, Production, Quality; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bewley, J.; Nonogaki, H. Maturation and Germination; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bewley, J.; Bradford, K.; Hilhorst, H.; Nonogaki, H. Physiology, Development, Germination and Dormancy, 3rd ed.; Bewley, J., Bradford, K., Hilhorst, H., Nonogaki, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 133–181. [Google Scholar]

- Obura, M.; Lamo, J. Influence of seed development and maturation on the physiological and biochemical seed quality. In Seed Biology-New Advances; INTECHOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Novita, A. The effect of gibberellin (GA3) and Paclobutrazol on growth and production on tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum Mill.). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1025, 012037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yao, Y.; Han, L.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, Y. OsABA8ox2, an ABA catabolic gene, suppresses root elongation of rice seedlings and contributes to drought response. Crop J. 2020, 8, 480–491. [Google Scholar]

- Sosnowski, J.; Truba, M.; Vasileva, V. The impact of auxin and cytokinin on the growth and development of selected crops. Agriculture 2023, 13, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).