Abstract

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are negative but preventable experiences within family and social environments. Originally focused on abuse and household dysfunction, ACE indicators now include many social factors, such as social determinants of health and racism. Disabled Children and Youth (DCY) are particularly vulnerable to ACEs, whereby different body/mind characteristics and lived realities influence ACE exposures and their impacts differently. Racism is recognized as an ACE and as a risk factor that increases ACE exposures and worsens outcomes. Ableism, the negative judgments of body/mind differences, and disablism, the systemic discrimination based on such judgments, are often experienced by DCY with the same three linkages to ACEs as racism. The objective of this scoping review was to analyze how the ACE academic literature covers DCY and their experiences of ableism and disablism using keyword frequency and thematic analysis approaches. Only 35 sources (0.11%) analyzed DCY as survivors of ACEs. We found limited to no engagement with ableism, disablism, intersectionality, the Global South, family members and other DCY allies experiencing ACEs, and ACEs caused by the social environment, as well as few linkages to social and policy discourses that aim to make the social environment better. More theoretical and empirical work is needed.

1. Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are encountered by 40% or more children (; ; ; ; ; ), with even higher rates reported for marginalized children (; ; ). The original ACE study looked at health risk behavior and disease in adulthood as consequences of being a survivor of ACEs () and focused with the original 10 ACEs on child abuse, neglect in the family and household dysfunction (). Since then, ACE frameworks have expanded to include social factors outside of the family (; ), including community stressors (), racism (; ; ; ), poverty (), climate change () and ACEs have been classified as a social determinant of health (; ; ; ). Social determinants of health are non-medical “conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live and age, and the wider forces that shape the conditions of daily life” ().

The original ACE study looked at the age, gender, race and education level of participants but did not ask whether participants were disabled children and youth (DCY)1 during childhood (). With other words the study did not look at DCY being survivors of ACEs. This is a problem. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) () is testament to disabled people of all ages experiencing many of the ACEs used in the literature. Furthermore, DCY can react to ACEs more severely and differently depending on their body/mind characteristics and their lived reality. We could not find any study that reviewed the academic engagement with ACEs experienced by DCY more broadly, though some studies explored certain aspects within individual disability groups such as autistic children (). The main aim of our study was therefore to ascertain the extent and how DCY are covered within the ACE-focused academic literature.

Racism has been linked to ACEs in three major ways: as an ACE itself, as a risk factor that increases the likelihood of other ACEs, and that it can deepen the negative consequences of an ACE ().

Ableism and disablism are isms often experienced by DCY. Ableism is a term used to highlight the sentiment that certain abilities are seen as essential. Individuals or groups who are labeled as lacking, or are lacking, these essential abilities are often seen as inferior (, , ; , , ). Ableism was coined by the disability rights movement in the 1970s () “to question normative body/mind ability expectations and the ability privileges (i.e., ability to work, to gain education, to be part of society, to have a positive identity, to be seen as a citizen) that come with them” (). Disablism is one consequence of this negative ability judgment and is defined in relation to disabled people as a “discriminatory, oppressive or abusive behaviour arising from the belief that disabled people are inferior to others” () or in more general terms “the ability expectations, and ableism oppression (the negative treatment) of the ones judged as impaired as ‘ability-wanted’ by applying irrelevant body ability expectations” ().

Ableism and disablism can exhibit the same three linkages to ACEs as racism. Given these parallels with racism’s role in ACEs, we investigated to what extent and how the ACE-focused literature engages with the concepts of ableism and disablism in conjunction with DCY.

The Center for Youth Wellness developed in 2015 the “Adverse Childhood Experience Questionnaire” Teen Self-Report measure that can be seen as covering ableism and disablism given their wording “child treated badly because of race, sexual orientation, place of birth, disability, or religion” () and in (). We therefore investigated whether that measure was present in the literature we covered.

One main part of the initial set of ACEs focused on the bad behavior of parents, (neglect and abuse) towards the child. Racism experienced by parents is seen to also influence in a negative way the caregiving ability of parents (; ).

Ableism and disablism experienced by siblings or parents of the DCY can also have negative consequences for all family members. We therefore investigated how family members are covered in the ACE focused literature engaging with DCY. It is argued that advocates for ACE prevention may benefit from connecting with researchers in other fields (). The actions proposed in many academic and non-academic discourses that aim to make the social environment better (e.g., equity, diversity and inclusion, science and technology governance, social determinants of health, environmental activism) are impacted by and impact the ACEs of DCY. Not considering how their discussions are impacted by and impact the ACEs of DCY especially the ACE of ableism and disablism risk proposing solutions that are not useful or detrimental for disabled people of all ages. Therefore, we investigated whether discussions in these fields take into account ACEs of DCY.

Given our focus, our study could be useful for many academic discussions, but also policy makers and educators covering, for example, ACEs of disabled people.

1.1. Evolution of the Definition of ACE

In a 2014 conceptual analysis based on the existing literature of ACE, it is noted that no clear definition of ACE existed and that terms, such as childhood maltreatment, and childhood trauma have been used interchangeably with ACE (). The authors proposed five characteristics of ACEs based on the literature (harmful, chronic, distressing, cumulative, and varying in severity) () and developed the following definition:

That the definition of ACE has to move beyond the family environment is also reflected in a 2019 study where authors argued,“childhood events, varying in severity and often chronic, occurring within a child’s family or social environment that cause harm or distress, thereby disrupting the child’s physical or psychological health or development”.()

and a 2022 study where authors cautioned that if“We also strongly encourage researchers not to limit their definition to adversities that occur solely or mostly within the child’s immediate family. Otherwise, consequential adversities that occur outside the household(e.g., bullying by peers), as well as the societal context of the adversities within the household, are in danger of being ignored, and potentially effective interventions might be missed”.()

“upstream structural factors that shape ACE exposures are ignored, it could lead one to wrongly attribute the root causes of health inequities to household ACEs, rather than the structures that create the risk of ACEs. The danger of such a misattribution that it results in blaming individual parents (or marginalized groups/cultures) for ACEs”.()

1.2. Evolution of What Counts as an ACE and the Instruments Used

The original ACE study used questions from the Conflicts Tactics Scale and (), the 1988 National Health Interview Survey, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveys and the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey run by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Diagnostic Interview Schedule of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to look at the initial 10 ACEs ().

Then other ACEs were added, such as “being sent away, parental unemployment, witnessing injury or murder, being threatened or held captive, parental death and community violence” () and marriage, parental death, peer violence or bullying, witnessing community violence, and exposure to war or collective violence () using the “Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire”. ACEs are also seen to be caused by the social environment (; ; ) and social factors such as income (; ; ; ; ; ; ), climate change (; ; ), political violence, forced migration, unsafe cultural practices (), conflict and population displacement are seen to exacerbate ACEs ().

Various studies demand that racism and ethnic discrimination be used as ACEs (; ; ; ; ; ; ), because “racial and ethnic minority children disproportionally experience ACEs due to the impacts of structural inequality and discrimination” () see also (; ; ) and that the existing ACEs do not reflect the lived experiences of marginalized populations (; ; ; ). The impact of intersectionality on ACEs has been investigated in various combinations (; ; ; ; ; ). A culturally informed Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) model (“C-ACE”) was developed to understand the impact of the ACE of racism on Black youth () and the Expanded Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) measures were designed to include racism, historical trauma, and systemic inequality to better capture the adversity experienced by marginalized groups (). The “ACE-I hypothesized a three-factor structure (experiences of violence/unrest in one’s home country, danger encountered on the migration journey, and instability of life as an immigrant)” () and a measure to generate data on ACEs experienced by members of the LGBTQ2S+ community has been developed ().

1.3. ACEs of Disabled Children and Youth Resulting from Ableist Judgments and Disablist Treatments

The original ACE study investigates the appearance of disabilities, impairments, health problems, and diseases as consequences of ACEs (). Although this study covered various demographics of the participants, it did not ask whether participants were DCY at the time they experienced the ACEs. So, they did not investigate DCY being survivors of ACEs. Given the vast differences (body/mind and lived reality) among DCY, different DCY may respond to, and be impacted by, ACEs in different ways, leading to different health and social consequences. The exclusion of DCY from the original ACE study is very problematic, given that DCY disproportionately experience not only the ten initial ACEs but also the other family and social environmental factors now recognized as ACEs, such as violence and abuse (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ), neglect (; ) and bullying () including cyberbullying (; ; ; ; ; ; ), poverty (; ), health inequity () and environmental issues, such as climate change and environmental disasters (; ; ; , , ; ; , ; ; ; ; ) compared to their non-disabled counterpart.

Then ACEs also intersect with DCY in a unique way. DCY often become direct targets of ableism and disablism.

Taking the cue from how racism is linked to ACEs as an ACE by itself, and a risk factor for experiencing ACEs and more negative consequences of ACEs (), ableism and disablism could be seen to be linked also in these three ways.

First, ableism and disablism are ACEs by themselves. Being constantly discriminated against (disablism) as a consequence of being negatively ability-judged (ableism) has been linked to the same impacts racism has, namely inflicting stress, causing decreased self-esteem due to internalizing ableism and disablism, and being harmful to one’s physical and mental health.

Carol Gill, the former director of the oldest disability studies program in the USA, describes the systemic and ever-present problem of disablism, as in disability burnout, as follows:

Autistic burnout has been described with a similar take on the problem of ableism and disablism:“After struggling with employment bias, poverty, blocked access to the community and its resources, unaccommodating and selective health services, lack of accessible and affordable housing, penalizing welfare policies, and lack of accessible transportation, some may experience what is known in the disability community as “disability burnout.” This term refers to emotional despair engendered by thwarted opportunities and blocked goals. It is aggravated and intensified by years of exposure to disability prejudice and devaluation. In fact, a frequently repeated theme in research interviews with persons with disabilities and illnesses is, “I can live with my physical condition but I’m tired of struggling against the way I’m treated””.(), cited in ()

Second, ableism and disablism are risk factors for increased ACE exposure. The wordings of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) (), reflect the reality that disabled people of all ages are constantly exposed to many negative social realities, of which many are identified as ACEs in the ACE literature. Furthermore, many studies, show that disabled people of all ages are disproportionately exposed to ACEs (without using the term ACE), such as violence and abuse (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ), neglect (; ) and bullying () including cyberbullying (; ; ; ; ; ; ), poverty (; ), health inequity () and environmental issues, such as climate change and environmental disasters (; ; ; ; ; ; ; , ; ; ; ; ) to list a few. This dynamic makes sense. If one is judged in a negative way, this increases the chance that one is treated in a negative way.“Autistic burnout is described as a debilitating condition that severely impacts functioning, is linked to suicidal ideation and is driven by the stress of masking and living in an unaccommodating neurotypical world”.(), cited in ()

Third, ableism and disablism are barriers to identifying, treating, or responding to ACEs. ACEs and their effects may be overlooked, misdiagnosed, or dismissed, and the body/mind difference might be identified as the cause of the problem and not ACE, due to ableism and disablism present in the healthcare system ().

Then ableism and disablism also intersect with other negative isms (e.g., sexism, racism, colonialism, casteism, and ageism) (), increasing the risk for ACE exposure and negative actions in response to the ACE.

In the original ACE study article, it was argued that societal changes are needed for primary prevention of adverse childhood experiences (). Such actions must include the elimination of ableist judgments and disablist treatments, and the ACE discussions should acknowledge the negative impacts of structural disablism and ableism on ACEs.

1.3.1. ACE of Family Members of DCY

One main part of the initial set of ACEs focused on the bad behavior of parents, (neglect and abuse) towards the child. However, similarly to the effect of racism on parenting so can ableism and disablism negatively impact family dynamics.

For example, there is the possibility that family members (parents and siblings) might exhibit ableist judgments and disablist treatments towards their disabled child or sibling if family members internalized the negative sentiments of the DCY exhibited by the social environment, as, for example, reflected in this quote from the 2001 book Dark Remedy: the impact of thalidomide and its revival as a vital medicine:

Then parents and siblings of DCY face being stigmatized because of the ableist judgment of their DCY (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ) and they face attitudinal and other societal barriers in being advocates for their DCY (). Given that stigma experienced by family members is increasingly recognized as an ACE, these aspects should also be covered within the ACE evaluations.“How did parents endure the shock of the birth of a thalidomide baby? The few who made it through without enormous collateral damage to their lives had to summon up the same enormous reserves of courage and devotion that are necessary to all parents of children with special needs and disabilities; then, perhaps, they needed still more courage, because of the special, peculiar horror that the sight of their children produced in even the most compassionate”.()

1.3.2. Linking the ACEs of DCY to Broader Social Problem-Solving Discourses

It is argued that advocates for ACE prevention may benefit from connection with researchers in other fields (). This also makes sense in relation to DCY.

The actions proposed in many academic and non-academic discourses that aim to make the social environment better (e.g., equity, diversity and inclusion, science and technology governance, social determinants of health, environmental activism, allyship) are impacted by and impact the ACEs of DCY. Not considering ACEs of DCY in these discourses may render the actions proposed in their discussions less useful or detrimental for disabled people of all ages.

ACEs are a societal problem, and science and technology advancements are linked to ACEs in many ways. Two areas can be highlighted: one being that they generate new ways to cause ACEs such as cyberbullying enabled by ICT advancement, and the second being that artificial intelligence is envisioned to predict (), identify and mitigate ACEs (). DCY and disabled people of all ages are impacted by both aspects. Science and technology governance discourses and discussions in many technology-focused ethics fields, such as AI-ethics, bioethics, computer science ethics, information technology ethics, nanoethics, neuroethics, and robo-ethics (), aim to decrease or prevent the appearance of societal problems linked to scientific and technological advancements. As such these discussions should cover the role of science and technology in the context of ACEs and general and the specific reality of DCY.

To conclude, ACEs are a negative lived reality experienced by 40% or more children and youth. While originally focused on abuse and household dysfunction, ACE indicators now include broader social factors like poverty, racism, ethnic discrimination, and climate change. Disabled people of all ages disproportionately experience problems with all the factors by now identified as ACEs. Ableism and disablism in sync with racism are an ACE, increase the risk for ACE exposure, and produce barriers to ACE response and recovery. We found only one ACE measure in our pre-search of non-academic sources that covered being treated badly because one is a DCY (). Furthermore, we did not find any review that looked at how DCY in general are covered in the ACE-focused academic literature. All the reviews we found focused on a specific disability and specific ACEs. Our study aimed to contribute to filling this gap.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Scoping studies are used to investigate the state of research on a given topic (; ). Our scoping study focuses on the academic research that has been conducted on the ACEs experienced by DCY. Our study followed a modified version of a scoping review outlined by (). We fulfilled all the requirements of the Prisma chart for scoping reviews () (Appendix B). To fulfill the research questions with the scoping review, we applied two approaches. We used manifest coding (hit count approach) (; ) to ascertain the presence but especially the absence of certain terms reflecting certain themes we think should be present in the ACE academic literature engaging with DCY. Many of the words we performed hit counts with are linked to specific discourses, which we think should engage with the ACEs of DCY because these discourses are impacted by or impacting the ACEs of DCY (see our justification of research question 5). And we used a thematic content analysis to describe the themes we found.

2.2. Theoretical Lens

We interpret our findings through the field (; ; ; ; ; ; ) and methodology () of critical/disability studies, which investigates the social, lived experience of disabled people, and disablism, the systemic discrimination based on not measuring up to irrelevant ability norms (). Covering the Global South, in one study it is stated:

And for one of her last musings about the field, see the views of the late Critical Disability Studies scholar from India Anita Ghai, a pioneer in disability studies/Critical disability studies and the role of disabled women ().“Critical disability studies (CDS), or critical disability theory (CDT), includes interdisciplinary approaches to analyze disability as a socio-political, historical, and cultural phenomenon that is shaped by symbolic and sociocultural structures, political ideas, literary representations, narratives and practices in various world settings”.()

Disability Justice added intersectionality to the mix (; ; ; ; ) and is a main lens in teaching critical disability studies (; ). Disability studies is linked to critical pedagogy (; ). The focus of critical disability studies fits with the views of disability rights groups, such as People with Disability Australia (PWDA) and the American Association of People with Disabilities (AAPD) (). The definition of disability we outline in Note 1 reflects the disability studies stand that every disabled person sees any given characteristic that makes them part of the disability community differently and that every disabled person should be able to self-identify their body/mind characteristics as they see fit.

We also make use of some of the over 35 ability-based concepts that have been coined within the disability rights movement and the fields of disability studies and the three strands of ability-based studies (ability expectation and ableism studies, short ability studies (, ), studies in ableism (, , ), and critical studies of ableism (; )), which focus on the investigation of ability-based expectations, judgments, norms, and conflicts, to analyze in more detail how the foundational ability judgment terms ableism and disablism manifest themselves and what to do about it. All these fields look into how to de-disablize (removal or undoing of disablism) (), how to implement anti-disablism (; ; ), (resistance to disablism) and how to achieve disability justice, which adds intersectionality of disabled people with other identities to the mix (; ; ; ). And in the end they engage with how to achieve ability justice/ability judgment justice, “a world, that eliminated irrelevant and/or arbitrary body/mind ability expectations, decreased ability privileges and disablism based on these expectations, and enabled the use of ability expectations and ableism to decrease ability judgment-based oppression, inequity, disablism and privilege” ().

We also were guided by the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (), which one could see as a list of ACEs DCY experience.

2.3. Identification of Research Questions

The objective of this scoping review was to analyze how the ACE academic literature covers DCY. To fulfill the objective, we asked first the overall question:

Research question 1: How and to what extent does the ACE focused academic literature cover ACEs experienced by DCY?

Then we asked the specific question:

Research question 2: How and to what extent does the ACE focused academic literature cover ACEs experienced by DCY due to being negatively judged as DCY?

Of the literature that described DCY experiencing ACEs because of being negatively judged as DCY we analyzed the content further.

There are by now many ACEs covered in the literature, so we asked:

Research question 3a: What ACEs are identified in relation to DCY?

Research question 3b: How and to what extent does the ACE focused academic literature cover ACEs beyond the original 10 ACEs, such as ACEs linked to the social environment (being poor, climate change…) in relation to disabled people?

Racism is by now classified as an ACE. Ableism and Disablism are the ability-judgment equivalents of racism and main influencers of the lived reality of disabled people of all ages, so we asked:

Research question 4: How and to what extent does the ACE-focused academic literature cover ableism and disablism as ACEs experienced by DCY and ableism and disablism influencing other ACEs and their consequences that disabled people are exposed to?

Parents’ problematic behavior is a main aspect of the initial 10 ACEs. We decided to focus on a different aspect. We see parents and siblings as allies of their DCY. And that means, they have to be activists for their DCY. Many studies highlight problems parents of disabled children face, such as being stigmatized because they have a disabled child (; ; ; ; ; ; ) and that they face attitudinal and other societal barriers in being advocates for their child. This negative reality could lead to a situation that generates ACEs for the parent, sibling and disabled child.

So, we asked:

Research Question 5: Does the ACE focused academic literature cover the negative societal treatment of parents and siblings of a disabled child as an ACE?

The actions proposed in many discourses that aim to make the social environment better (e.g., equity, diversity and inclusion, science and technology governance, environmental activism, allyship) are impacted by or impact the ACEs of DCY. Not considering the ACEs that DCY experience as part of their lived reality may render such actions less useful or detrimental for disabled people of all ages. So, we investigated:

Research Question 6: How and to what extent does the ACE focused academic literature link to academic and non-academic discussions that propose actions to make the social environment for marginalized groups including disabled people of all ages better?

2.4. Data Sources, Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria, and Data Collection (Content Analysis and Manifest Coding)

We searched on 20 January 2025, the abstracts of the academic databases EBSCO-HOST (an umbrella database that includes over 70 other databases itself), Scopus and Web of Science and the abstract/title of Pub Med with no time restrictions. We did the searches for strategies 2, 4–8, 11–13 on 29 September 2025 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search strategies used.

These databases were chosen because together they contain many journals that cover disabled people from a non-medical angle that could cover the social aspects of the cause of ACE of disabled children. The databases we used contain, for example, the following sources that have disability studies in the title: disability studies quarterly; Canadian journal of disability studies; Journal of Literary and Cultural Disability Studies; Review of Disability Studies an International Journal; Disability Studies Reader Fifth Edition; Journal of Disability Studies in Education; Indigenous Disability Studies; Routledge International Handbook of Critical Disability Studies; Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies; Routledge Handbook of Postcolonial Disability Studies; Culture Theory Disability Encounters Between Disability Studies and Cultural Studies; Disability Studies and the Environmental Humanities Toward an Eco Crip Theory.

It also has many journals that have “disability” in the title and that cover social aspects of disability, such as Disability & Society.

We also used Pub-Med, although the database focuses on medical issues, because it could have contained some articles that cover ACEs in the way we were investigating.

As to inclusion criteria, scholarly peer-reviewed journals were included in the EBSCO-HOST search and reviews, peer-reviewed articles, conference papers, and editorials in Scopus and the Web of Science search was set to all document types as was PubMed. As to exclusion criteria, data not fitting the search strategies, research questions, and data not being in English were excluded.

For the desktop hit count manifest coding analysis and the qualitative content analysis we downloaded the set of abstracts indicated using the citation export function of the databases and the import function of the Endnote 9 software. The Endnote 2025 software was also used to eliminate duplicates due to abstracts being present in more than one database. The final number of abstracts of a given used search strategy were exported as one WORD Office file from the Endnote 9 software and transformed into one PDF file using Adobe Acrobat, 2025. The PDF was used to identify relevant studies. The available full texts of the relevant studies identified from the abstracts obtained with strategy 3 were downloaded.

2.5. Data Analysis

To answer the research questions, we used two approaches. We used manifest hit count coding for the 733 abstracts containing the phrase ACE and the disability terms; the 35 relevant abstracts identified from the 733 abstracts; the 29 full texts articles available from the 35 abstracts; the 1633 abstracts containing the terms “adverse childhood experience” OR “childhood trauma” OR “childhood maltreatment” OR “childhood adversity” OR “traumatic childhood events” and the disability terms; and the 4237 abstracts containing the terms “ableism” OR “ableist” OR “disablism” OR “disableism” OR “disableist” obtained with strategy 13.

We used a thematic content analysis for the 35 relevant sources identified by reading the 733 abstracts and the 29 full texts available from the 35 abstracts (for 6 relevant abstracts the full texts were not available). The thematic and hit count analysis was carried out by both authors. No difference showed up for the hit counts between the two authors. For the analysis of relevance of the 733 abstracts and the thematic analysis of the 35 relevant abstracts and the 29 full texts, peer debriefing was performed and the few differences that showed up between the authors were discussed and resolved.

2.6. Trustworthiness Measures

Trustworthiness measures include confirmability, credibility, dependability, and transferability (; ; ). Peer debriefing was employed, as already outlined. As for transferability, we give all the details needed so others can decide whether to apply our search approaches to other data sources, whether to use other disability terms and other keywords.

2.7. Limitation

The search for relevant sources was limited to specific academic databases, English language literature and abstracts. As such, the findings are not to be generalized to the whole academic literature, non-academic literature, or non-English literature. We also did not use every possible disability characteristic as a term. However, many different disabilities are covered by using “disabilit*” and “impair*” as general terms. We did not use the term “patient*” because the focus very likely would be on the medical angle, not the social cause of ACEs. We did also not use the term “mental health”, as low mental health is covered often as a negative consequence of ACEs and therefore does not as such focus specifically on DCY with mental health issues experiencing ACEs. However, our findings allow conclusions to be made within the parameters of the searches and our research questions.

3. Results

3.1. Finding the Relevant Content for the Thematic Analysis

Using the four databases over 31,635 abstracts contained the phrase “adverse child experiences” (strategy 1). When we added our disability terms to the search the number went down to 2109 so 6.66% indicating that disabled people are not the main coverage (strategy 3). As the 2109 abstracts came from four databases (with one looking at 70 other databases) there would be duplicates. Using the endnote 9 software to eliminate duplicates the number of unique abstracts went down to 733 (strategy 3).

Our disability terms do not cover all types of disabled people. As disablism and ableism are such a foundational ACE for DCY we also searched within the 31,635 abstracts containing the phrase “adverse childhood experience*” for terms linked to ableism and disablism (strategy 9) as these are the equivalent for disabled people to racism, sexism and other negative isms that indicate systemic discrimination for other social groups. That search only generated one hit (), which was also part of the results from strategy 3. The number for racism was 366 abstracts (strategy 10) indicating that terms linked to the systemic discriminations of other groups are used to some extent but that the terms used for disabled people are not present.

Of the 733 unique abstracts obtained with search strategy 3 the majority covered ACE as being a cause of being a disabled person especially in relation to ADHD/autism. Numerous abstracts indicated that DCY experience other health issues due to ACEs but did not focus on who or what in the social environment caused the ACE and why, e.g., “since children with intellectual disabilities are much more likely to experience adverse childhood experiences that predict significant mental health problems in adults” or “Children with ADHD have a higher prevalence of ACEs” but then said that they examined “the association between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), child and household characteristics, and ADHD diagnosis and severity”. Some indicated that disabled children are at increased risk, such as “Children with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD) are at increased risk of ACEs” () but then state “We aimed to explore the association between ACEs in parents and children; if there is an association between parental ACEs and NDD traits, and if ACEs in parents or children are associated with the child’s emotional behavioral problems” (), which suggests that they focus on ACE leading to health problems of DCY, which is not our focus. Or they stated that “Rates of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are greatly increased in people with FASD (only 10% have 0 or 1 ACE, 35.7% have 2–6 ACES, and 54.1% have 7–10 ACEs” () but then focus on screening for FASD and not on what ACEs are experienced because one is badly treated as a person with FASD. Or it was stated “ACEs heighten the risk for developing ADHD symptoms” ().

Some stated that there is a higher risk for example, for deaf and hard of hearing (DHH), “those who are DHH were significantly more likely than their same-age hearing peers to report a high-risk number of ACEs”, but then do not say why (other examples of stating higher risk of ACEs see (). Or ACE was listed as a risk factor for suicidality of autistic youth but without saying where the ACE came from ().

Only 35 abstracts focused on DCY experiencing an ACE because of the negative treatment they received due to being DCY. Of these 35, 16 covered ACEs of people with ADHD/autism/attention deficit/neurodiversity/neurodivergence (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ) and 18 covered other disabled people (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; , ; ; ; ; ; ; ).

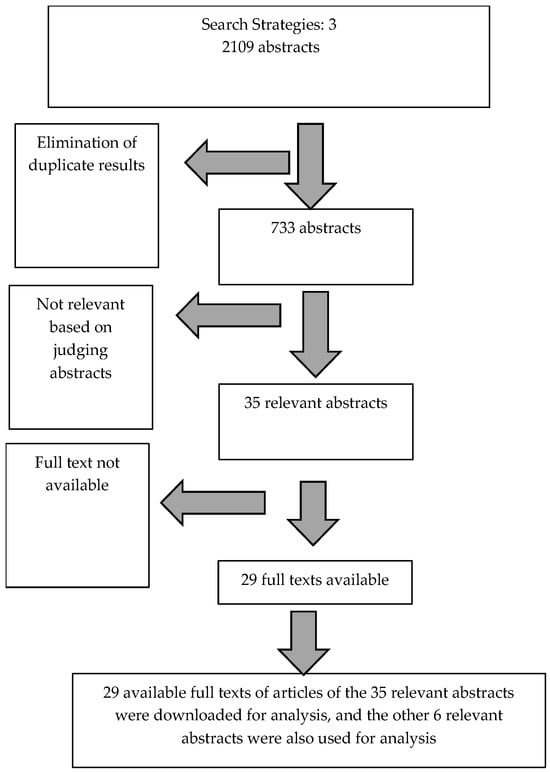

Of the 35 relevant abstracts we downloaded the 29 available full texts (see Figure 1), which were 15 of the 16 abstracts covering ADHD/autism and attention deficit (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ) and 14 of the 19 abstracts covering other ‘disabilities (; ; ; ; ; , , ; ; ; ; ; ; ).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the selection of academic abstracts and full texts for thematic analysis.

3.2. Quantitative Results of 733 Abstracts, the 35 Relevant Abstracts, the 29 Full Texts, the 1633 Abstracts with ACE Synonyms, and the 4237 Abstracts Containing Ableism/Disablism

To obtain our hit count results to see what is there and not there, we show in Table A1 (Appendix A) the results for the various sets of abstracts covering (a) terms linked to ACE, (b) different disability terms, (c) some medical terms, (d) intersectional phrases depicting disabled people who also belong to another marginalized group, (e) some disability rights-related terms, (f) some other terms linked to important discourses, (g) science and technology governance-related terms, (h) well-being measures, and (i) some indicators used in the well-being measures: OECD Better Life Index, the Canadian Index of Well-being, the Community-based Rehabilitation Matrix and the Social Determinants of Health ().

We performed some hit-count searches of the 1633 abstracts obtained from searching for the terms “childhood trauma”, “childhood adversity”, and “traumatic childhood”, which are seen as being used interchangeably with ACE (). And we searched the 4237 ableism-related terms containing abstracts for mental health and the ACE-related terms as another way to see whether ACE is mentioned in conjunction with ableism and disablism.

For some of the search terms, we only looked at the 35 abstracts and their full texts as they reflected the relevant literature.

The main findings were:

- As to the terms often used as synonyms with ACE (“childhood trauma”, “childhood adversity”, “childhood maltreatment” and “traumatic childhood”), all were present in the 733 abstracts and the 29 full texts. “Childhood trauma” and “childhood adversity” were present in the 35 abstracts.

- In the 4237 abstracts, “adverse childhood experience” was mentioned in one abstract we also found within the 733 abstracts, and one abstract mentioned “childhood trauma”, which was not part of the 733 abstracts. “Childhood maltreatment” and “traumatic childhood”) were not mentioned.

- There was a very uneven presence of disability terms.

- Although the term “patient” was not part of the search, it was the dominant term in the 733 abstracts containing the term ACE and the disability terms, which could be seen as an indicator of the focus of the abstracts and the result that most of the 733 abstracts were false positives.

- The term “patient” was also number one in the 1633 abstracts covering ACE-related terms and the disability terms.

- Ableism and disablism and disability rights-related terms were rarely mentioned, including the term “disability studies”.

- The term “intersectionality” and some example intersectionalities covering disabled people also belonging to another marginalized groups were also rarely or not at all mentioned.

- The well-being measures we looked at (list from ()) were not present, with the exception of the “social determinants of health” phrase being mentioned three times.

- The majority of the non-health indicators we used from the four composite well-being measures (“The social determinants of health (SDH)”, “The Canadian Index of Wellbeing (CIWB)”, the “OECD Better Life Index”, and the “Community-based rehabilitation (CBR) matrix”) () had no or few hits.

- Many terms linked to social and policy discourses that aim to make the social environment better and could influence the ACE situation of DCY in a positive way (e.g., equity, diversity and inclusion, social determinants of health, science and technology governance, environmental issues, health equity, and occupational rights terms) had few or no hits.

- Global South was not mentioned.

- We see parents and siblings being allies of DCY. But ally-related terms generated no hits.

- Climate change generated no hit.

The results for the 1633 abstracts were similar to the 733 abstract results, but with an even stronger presence of terms such as “patient” and “treatment” in the 1633 abstracts. Given that we already had mostly false positives with the 733 abstracts covering ACE and the disability terms, we decided not to analyze how many of the 1633 abstracts were relevant.

3.3. Thematic Analysis of the 35 Relevant Sources, Obtained from the 733 Abstracts

Table 2 gives an overview of the themes we found.

Table 2.

Qualitative results of the 29 full text and the 6 relevant abstracts where the full text was not available.

3.3.1. The Majority of Data Was About ACEs Causing ‘Disabilities’

Of the 733 abstracts the majority covered ACE being a cause of being a disabled person. Only 35 abstracts focused on DCY experiencing an ACE because of the negative treatment they received due to being DCY. Of these 35, 16 covered ACEs of people with ADHD/autism/attention deficit/neurodiversity/neurodivergence (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ) and 19 covered other disabilities (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; , , ; ; ; ; ; ; ). And this bias is noted. For example, in one of the 35 abstracts it is stated:

Within these, most see disability as a medical/health issue. One positioned disability as “(self-reported activity limitation and/or assistive device use)” (). However, the purpose was to expand the “ACE model by recognizing distinctions between health conditions and subsequent disabilities, which allows evaluation of the relationship between childhood adversity and later onset of disability” ().“Children with adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are more likely to develop Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). The reverse relationship—ADHD predicting subsequent ACEs—is vastly understudied, although it may be of great relevance to underserved populations highly exposed to ACEs”.()

They noted that

And they proposed“Because health conditions may be considered intermediaries on the pathway between ACE and disability, it is notable that ACEs affected disability strongly even after controlling for these conditions. This is particularly noteworthy for our subset analysis, because previous studies showed that serious psychological distress has a large effect on activity limitations in those with and without chronic health conditions [44]”.()

Only one source covered ACE within a disability studies framing of disability (Theoretical Frameworks on Disability ().“Studies that examined stress sensitization found that those with childhood adversity are more likely to develop psychiatric conditions when exposed to later-life stressors [31,48]. In addition, childhood maltreatment may increase the sensitivity to stressful social contexts, which can increase the incidence of health-risk behaviors [49]. An increase in these behaviors in response to stressors is yet another mechanism by which ACE exposure might increase disability, independent of chronic disease”.()

3.3.2. Prevalence

As to prevalence, within 9 of the 29 full texts it is noted that disabled people have higher rates of ACEs than non-disabled people (; ; , , ; ; ; ; ) (the same for four of the abstracts only (; ; ; ). In 13 of the 29 full texts it is noted that ADHD/autism/attention deficit/neurodiversity/neurodivergence people have higher rates of ACEs than non-disabled people (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ).

The following are some actual numbers:

- “higher percentage of persons with disabilities (36.5%) than those without disabilities (19.6%) reported high ACE exposure”();

- “81.7% of the children with ID experienced at least 1 ACE, as did 92.3% of the children with BIF” () (for numbers on intellectual disability see also ();

- “Overall, college students with disabilities (M = 8.00, SD = 9.07) were more likely than college students without disabilities (M = 4.77, SD = 7.03) to experience IPV victimization when we compared the extent of IPV victimization (p < 0.001)” ();

- “Autistic people are more than two times as likely than non-autistic people to experience an ACE” ();

- “ACEs are highly prevalent in working-age US adults with a disability, particularly young adults” ();

- “Children with neurodevelopmental disorders are victims of ACEs with frequency greater than the control group and the type of abuse that they suffer is mainly psychological and physical”();

- Children with ADHD were more likely to experience every type of ACE were more likely to have 1 to 3 or 4+ ACEs than children without ADHD ().

One study compared different disabilities: No disability (n = 273,463), Any disability (n = 125,023), High disability as in at least four types of disabilities (n = 10,493), Mobility (n = 68,978), Self-care (n = 16,654), Independent living, (n = 30,768), Hearing (n = 37,976), Vision (n = 21,228), Cognitive (n = 43,806) and covered Sexual abuse, Physical abuse, Emotional abuse, Domestic violence, Mental illness (household/family member), Substance Misuse (household/family member), Prison household/family member), Divorce/separation (household/family member). They concluded that all disability types exhibit higher numbers for all ACEs than non-disabled people. Cognitive being the one with the highest for all ACEs and high disability also increased ACEs ().

Higher rate of abuse of disabled people is flagged as the main reason for the higher rate of ACEs disabled people experience (; ; ; ; ; ).

For example “disabled children are 3.8 times more likely to be physically abused than non-disabled children” () and “compared to college students without disabilities, college students with disabilities experienced higher rates of IPV victimization and ACES” ().

Stigma, discrimination and ignorance about disability are factors which place people with disabilities at higher risk of violence and with that ACEs (; ; ). One study covering people with hearing loss reported the following factors: “corporal punishment by at least one of the parents (reported by 36%), being frequently bullied by peers (reported by 23%) and being seriously sexually abused by known or unknown people (reported by 30%)” ().

3.3.3. Cause of the ACE

All our relevant studies used the 10 ACEs. For example, one stated: “The results suggested that one in three children (35.0%) with disabilities would have at least one ACE. The prevalence rates of experiencing the nine specific ACEs were much higher for children with disabilities. Importantly, the five most prevalent ACEs for children with disabilities were hard to cover basic food and housing (40.9%), parental divorce (24.3%), alcohol/drug problems (11.1%), parent or guardian incarceration (10.6%), and adult abuse (6.8%), which were all related to family challenges” ().

Moving beyond the 10 ACEs bullying (; ; ; ; ), peer violence () and relational school bullying (e.g., trying to hurt a peer and/or that peer’s standing within a particular peer group)() were the main ACEs beyond the 10 ACEs used.

Other ACEs used were problematic caregiver-child relationship (), hospitalization (), technological violence, (), economic hardship (), extreme hardship due to family income () children with socioeconomic hardship (), income insufficiency (), death of a parent (; ; ) treated or judged unfairly due to race/ethnicity (no effect) (), treated unfairly due to race (no effect) for autism but higher odds for ADHD (), factors associated with childhood hearing loss and language experiences (), victim or witness of neighborhood violence (; ; ; ; ), living in an unsafe neighborhood (), food scarcity/insecurity (), food/housing insecurity (), antisocial personality (), being treated unfair due to health (), income insufficiency (; ), residential care center or foster care home (), not attending school before admission (), living in a non-nuclear family structure (), living in foster/care home (), less severe hearing loss of 16–55 dB, having a cochlear implant, and not attending at least one school with signing access (), cultural context and familial settings () and experiencing mistreatment due to their race or ethnicity ().

3.3.4. Comorbidity

Comorbidity is mentioned in nine full texts. One stated that there is a high comorbidity between ASD and trauma (), and another that “studies have shown similar impairment and comorbidity profiles in children diagnosed with ADHD before and past the age of 7” (). One argued that the “lack of attention to ACEs among disabled children is leading to their higher vulnerability and morbidity” (), another that the higher prevalence of ACEs within the neurodivergence community has implications for the morbidity issues of this group (). Another stated that individuals with ASD are “two to three times more likely to die from accidents (risky behavior) and complications from comorbid medical conditions than non disabled peers” (), see also (; ). One author argued that “the effects of poor physical and mental health are intertwined and comorbid mental health conditions are an important contributor to role impairment in those with physical health conditions” (). Depression and anxiety are reported as common comorbid disorders exhibited by children with autism because they experience negative life events or because they had mental health issues before the AC, which might have limit their ability to deal with the ACE, and they might have lacked the support needed to deal with the ACE ().

3.3.5. Ableism/Disablism Alone and with Intersectionality

Terms that highlight the systemic discrimination of disabled people such as disablism was not mentioned at all and ableism was mentioned only twice in linkage to ACE (; ), with Song asking for measures of ableism in relation to ACEs. One article engaged with ableism quite a bit but somehow outside of ACE ().

Intersectionality is mentioned only once in one of the articles that mentioned ableism ().

In () ableism is mentioned once arguing “ expanding ACEs measures to more fully illustrate the compounding impact of institutional racism and ableism on individuals marginalized by race, ethnicity, and ability is an important direction for future research” (). Given the wording this could also be classified under intersectionality.“The purpose of this study was to examine the lived experiences and multiple identities of disabled BIPOC trafficked women. The findings from this study help to identify a carousel of victimization experienced by disabled BIPOC trafficked women, starting with adverse childhood experiences, onto trafficking victimization that differed between Black and White women, and later while seeking services. These findings highlight the need for providers and researchers to think beyond monolithic identities and consider the intersecting ways in which various forms of oppression (ableism and racism) influence the experiences of disabled trafficked BIPOC women”.()

Ableism could have been covered much more. Various studies cover structural ACEs such as racism and ethnic discrimination but did not use ableism/disablism as a structural ACE to cover DCY.

For example:

This language indicates that the authors could have covered ableism and disablism as a risk factor (terms were not present in the full text either).Or“Childhood trauma [ACE] can include exposure to abuse, neglect, violence, racism, or medical procedures” (). Then it says that “Trauma is common and impacts all children; however, some populations, such as children with disabilities, have greater risk for experiencing adversity”.()

“Recent studies suggest that inclusion of community-level stressors, including neighborhood violence and racial discrimination, improves the validity of the ACEs scale and its ability to capture diverse types of ecological adversity impacting minority populations”()

and the same article stated

On the other hand, one engaged with the term ableism but did not directly label it as an ACE (). In this paper it is stated that the extended ACEs cover discrimination () but the same paper covers ableism as a different cause of stressor than ACEs one has to take into account during therapy, In its neurominority stressor model it lists ableism and ACEs as two different causes of distal stressors with family violence and ACEs categories under discrimination and abuse and ableism and stigmatized identity as another main category on the level of discrimination and abuse (). As to ableism the article makes the case that“families of children with developmental disabilities, generally, are more likely to reside in economically distressed neighborhoods with elevated rates of community violence”.()

It furthermore asked that the neurodiverse people voice has to be center stage to combat “the misinformation that perpetuates inaccurate stigmas and ableist rhetoric” and to contribute “to the development of positive group identities” (). It asks for the support of neurodiverse people to eliminate internalized ableism () and that “Broad systemic changes are essential to limit neuro minorities’ exposure to distal stressors in the form of discrimination, abuse, inequity, lack of accessibility, ableism, and stigmatised identities” ().“distal stressors are critical in shaping an individual’s self-perception and worldview. This often manifests as internalised ableism (Morgan, 2023), as well as anticipated discrimination and identity-related stressors such as shame and identity concealment”.()

3.3.6. ACEs and Well-Being

Various articles mention that ACEs decrease well-being in general (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ). However, very few linked a decrease in well-being to concrete ACEs.

In one article it is stated that “measures must consider the role of individual, family, household, community, and systemic factors, as all can have a negative impact on the health and well-being of this community” ().

One noted that the child opportunity index not used to investigate relationship between neighborhood disparities and child well-being in relation to children with ADHD ().

One noted that the psychological well-being of autistic or ADHD individuals largely reflect biopsychosocial processes related to the person-environment () and “Identifying processes that positively influence the developmental trajectories of neurominorities is a critical step for the proactive cultivation of mental well-being across the lifespan” ().

And“Embracing a shared social identity within supportive groups is associated with higher levels of self-esteem and reduced internalised stigma (Najeeb & Quadt, 2024; Taylor et al., 2023). This sense of belonging and community is crucial for fostering a positive social identity among neurominorities, ultimately contributing to the quality of their social connections, mental health and overall well-being (Najeeb & Quadt, 2024; Rivera & Bennetto, 2023). As healthy self identity is strongly associated with higher levels of wellbeing, providing support for people to authentically express themselves, celebrating unique strengths and qualities, and creating societal change regarding perceptions towards neurodiversity is critical”.()

One gave the following definition “The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental health as ‘a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community”().“Furthermore, adopting affirming, strengths-based approaches to neuro minority features is associated with better quality of life, subjective well-being, and lower levels of anxiety, depression, and stress”.()

3.3.7. The Issue of Parents and Siblings

Parents were mentioned in nearly every article, as the initial 10 ACEs cover various bad behavior of parents. Within our relevant sources, articles promoting the treatment of ADHD also portrayed parents in a negative way. One questioning the “negative parental attitudes toward ADHD medication” (), and another that “parents who either know their children have an ADHD diagnosis or can identify symptoms as a part of a medical disorder may be more protective or accommodating of the behaviors, possibly assuaging risk for future ACEs” (). Parents were also identified as a problem for not developing secure attachments with their child with ADHD due to not understanding or being receptive to the needs of their child ().

Our relevant sources also contained the themes of the disabled child causing stress in the parent (), that parents of children with ADHD have higher stress without saying why (; ) and that “the stress leads to bad actions by the parents such as substance abuse as a coping mechanism” ().

Ignoring the theme of parents or the child being blamed, only five of our relevant sources mentioned parents being impacted by societies actions (; ; ; ; ).

In one of our sources, it is stated:

And in another of our relevant sources it is noted that the “promotion of parent and patient advocacy skills” () is needed. Siblings were only mentioned in four relevant sources but only in one source the sibling was mentioned in a relevant way.“parents of Autistic and ADHD children reporting they feel socially isolated, stigmatised, and unable to access or receive the support they need to best care for their child”.()

3.3.8. Overlooked Topic/More Research Needed

Five articles specifically used the term overlooked (; ; ; ; ). Six indicated the need for more research and noted gaps in the existing data or made the specific case that the topic is missing (; ; ; ; ; ). The research suggestions most often mentioned were to involve disabled children in ACE research and to make ACE research accessible to disabled children (; ; ; ; ), to move beyond the original ACEs and their impact including to cover ACEs unique to different disabilities (; ; ; ; , ) and to fund research on the psycho-social aspects on the lives of disabled people and how they may be similar to, or differ from, their peers (). Factors not part of the original ACEs that are in need of research were the compounding effect of institutional racism and ableism on individuals marginalized by race, ethnicity, and ability (); ethnic factors (; ); home, community, and broader society (); community violence (); cultural factors (); global experiences of adversity, institutional experiences of adversity (); socioeconomic factors (; ); covering male and gender diverse/gender minorities; early adverse experiences of deaf service; barriers and challenges faced by BIPOC disabled trafficked women (); peer victimization and bullying (); and exploring the pathways that lead to heightened levels of poor health, well-being, and criminal justice outcomes in ND populations (). Research on the most effective educational interventions for those with disability and research that refines our understanding of risk and protective factors associated with the ability of adults with a disability to work is needed, as evaluating the effect of ACEs on outcomes, such as participation, are particularly important (). Research on how to prevent the ACEs (; ) and further research on the “differential pathways to IPV victimization across varying environments, such as children’s homes, schools, and communities” () were seen as needed as were to look at the relationship between ACE, resilience and children with autism (), to investigate more the impact of parents () and to learn from dialogue with parents, children and care providers (). One study asked for examining how neighborhood factors affect trauma informed care () and one to look at the interaction among the physical environment, ACE exposure, and disability (). Finally, one asked for research “to determine the best way to address ACEs to improve coping and functional recovery from stresses related to patients’ emerging or existing disabilities” whereby they reason that “although it is too late to prevent ACEs and/or prevent disease in these adults, it may still be possible to ameliorate the effects of impairments and help those affected by childhood adversity lead more functional lives” ().

3.3.9. Methods, Countries of Authors and Theories Used

Fitting with the theme of overlooked topic/more research needed mentioned in the sources, it is noteworthy that the research was mostly conducted in the USA, suggesting that research is needed in other countries. The country of origin of the authors of our sources was as follows: USA (n = 15); UK (n = 4); Australia and The Netherlands (n = 2), Canada, Norway and Turkey (n = 1); Multi country USA, Australia, UK, Switzerland (n = 1); and Multi country USA, China (n = 1). As for the methods used, there was only one conceptual paper (). There was one non-systematic review () and two systematic reviews/metanalysis (; ). Four studies did new interviews (; ; ; ).

To quote from the study that focused on ableism as a main lens:

There were cross-sectional online surveys, (; ), a general online survey (; ) the November 2023 to April 2024 a household survey (), a Delphi survey () and the Boricua Youth survey study ().“This study is led by survivors and was inspired by the vision of a disabled BIPOC sex-trafficked woman. She approached the first author about conducting research with the population in this study. The final survivor-led research team consisted of four disabled BIPOC sex-trafficked women, who cocreated the interview guide, and the Racism and Human Trafficking questionnaire used in the study. The complete interview guide and survey instruments were piloted with each survivor member to ensure clarity and effectiveness, resulting in edits of the tools at the conclusion of the four interviews. Each survivor also received two hours of training on research ethics before data collection began. One survivor member later identified other survivors for the study and provided a private space in an adult group home for some interviews. Findings were discussed with all co-researchers before writing the results. One survivor serves as a coauthor on this article”.()

All others made used of existing data, such as case files (n = 2), retrospective file review (n = 1) and other datasets such as the 2009 and 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) (n = 3), the 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey (n = 2), the North Carolina 2012 BRFSS (n = 1), the 2011–2012 National Survey of Children’s Health NSCH (n = 4), the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health NSCH, (n = 1), the 2018 to 2021 National Survey of Children’s Health NSCH (n = 1), the 2021 National Survey of Children’s Health NSCH (n = 2), the 2021 to 2022 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) (n = 1).

As to theories, few articles used theories. There was the lifestyle-routine activity theory (). Attachment theory () and schema theory a clinical theory () are used. Self-medication theory (), is used and seen to “suggests that individuals who have experienced ACEs may use substances as a coping mechanism or self-medication strategy to help with the various affective and mental health issues (e.g., depression, anxiety, anger, etc.) stemming from childhood maltreatment” ().

Only one article covered a theory in sync with disability studies using Dis/ability Critical Race Theory (DisCrit) describing it as

The authors argued that ‘Dis/ability Critical Race Theory (DisCrit) may be a useful framework for professionals who interact with trafficked disabled BIPOC women. It combines disability studies with critical race theory” (). And a whole section on Theoretical Frameworks on Disability ().“an emerging framework that critically examines the intersection of disability and race (Annamma et al., 2013), shedding light on the interconnected experiences of individuals who face both racial and disability-based discrimination. At its core, DisCrit challenges traditional notions of disability and racism, emphasizing how these two forms of oppression are deeply intertwined (Annamma et al., 2013). It recognizes that ableism and racism often intersect and interlock, compounding and deepening the marginalization experienced by disabled people of color (Gillborn et al., 2016)”.()

3.3.10. Policy Implications

Many policy implications are mentioned. To quote one source as it covers many action items:

Increase awareness of the danger of ACEs within DCY (; ), universal screening of trauma among autistic youth () and looking for ACEs in youth with ADHD () were other policy action items. Preventative measures for reducing ACEs (; ; ; ; ) were often mentioned, which unfortunately included treatment of ADHD (). Providing support for parents and carers (; ), providing support for single parent homes (), offering respite care (), and coping with adversity () and anti-bullying strategies () were mentioned. Other policy action items were to employ trauma and ACE informed culture and practice guidelines () to generate positive childhood experiences (; ), the need for mental health services for young children with disabilities (), and to address community-specific needs to improve trauma care delivery strategies (). One article highlighted the need to understand potential barriers to seeking support such as internalizing stigma stating:“Efforts must be made to improve screening and provision of resources and support for families of children with ASD and ADHD, including access to stable housing, adequate food, and protection from violence. Collaboration between healthcare professionals, social workers, and educators is crucial to identify and address the needs of these children and their families. Furthermore, it is important to raise awareness about the unfair treatment and experiences that children with ASD and ADHD may face due to their condition. Education and training should be provided to parents, teachers, and professionals to promote understanding, empathy, and inclusive environments for children with ASD and ADHD. Efforts to reduce stigma and discrimination against these children should be prioritized. In addition, community- based initiatives should be implemented to create safer neighborhoods for children with ASD and ADHD. This may involve improving infrastructure, and providing access to social interventions that promote safety and engagement”.()

“According to the IPV Stigmatization Model, three stigma components such as cultural stigma (i.e., societal beliefs that de-legitimize people experiencing abuse), stigma internalization (i.e., the extent to which people come to believe that the negative stereotypes about those who experience IPV may be true of themselves), and anticipated stigma (i.e., concern about what will happen once others know about the partner abuse) could hinder IPV help-seeking behaviors (Overstreet & Quinn, 2013). The stigma related to IPV victimization may be further compounded for those who have multiple stigmatized identities, such as having disability, low SES, or being a member of a racial or sexual minority, and therefore may play a key role as a barrier to help-seeking (Overstreet & Quinn, 2013)”.()

4. Discussion

Our scoping study suggests a neglect of DCY as survivors of ACEs, especially due to ableist judgments and disablist treatments and a lack of seeing ableism and disablism as an ACE by themselves, ableism and disablism as risk factors for increased ACE exposure, and ableism and disablism as barriers to identifying, treating, or responding to ACEs. Ableism was only mentioned in one abstract () and three full texts (; ; ), and disablism was mentioned not at all. Other missing topics included intersectionality, the experiences of discrimination faced by family allies as potential ACEs, and many ACEs covering the social environments. Academic discourses that aim to improve the social environment (e.g., equity, diversity and inclusion, science and technology governance, environmental issues) and that are impacted by or impacting ACEs of DCY were not linked to discussions around ACEs of DCY. Our data also showed a lack of diversity of countries of origin of authors, a lack of conceptual articles, and a lack of theories linked to disability studies. In the remainder of the discussion we follow the headers of the qualitative results, with the exception that as the last header we engage with some of the hit count results in Table A1 related to research question 5, which was about to what extent the ACE-focused academic literature links to academic and non-academic discussions that propose actions to make the social environment for marginalized groups, including disabled people of all ages, better.

4.1. Data About ACEs of DCY

The data we obtained covering ACE and disabled people (733 abstracts) exhibited a bias towards covering disabilities as a medical consequence of ACEs and a neglect of examining DCYs as survivors of ACEs and ACEs DCY experience because of ableist judgments of their body/minds and disablist treatments (35 of the 733 abstracts). The very concepts of ableism and disablism as an ACE by themselves were not engaged with either.

Our findings fit with the focus of the original ACE study (), which did not investigate the possibility that being a DCY can itself lead to ACEs in general, and that the ACEs could be due to ableist judgments and disablist treatments. Our results also might be a consequence of the limitation of one of the main measures of ACEs used (), as the following states:

However, our findings are problematic for disabled people. Most of the research gaps identified in our relevant sources reflect a similar conclusion. Our findings are also problematic given that many of our relevant sources indicated that DCY have a higher prevalence of ACEs than non-disabled youth and given that in the original study it was argued that societal changes are needed for primary prevention of adverse childhood experiences ().“BRFSS survey does not allow for those with disabilities to be categorized according to physical disabilities versus mental or emotional disabilities. In addition, we were unable to determine the timing of ACE exposure in relation to disability onset”.()

For effective ACE preventions it is essential to know why the numbers are higher, and for that the reality of ableist judgments and disablist treatments have to be part of the analysis because in the same way that racism is seen as a risk factor for increased ACE exposure () so are ableism and disablism. Furthermore, many disabled people live in social situations that make them more vulnerable to ACEs. For example, ACEs are more prevalent among people living in poverty (), and disabled people live disproportionately below the poverty line (). Ableist judgments and disablist treatments, which one can label as social attitudes, are at the root of most ACEs that are experienced by DCY to a greater extent (for abuse, including abuse by carers, see for example (; ; ).

Our findings are also problematic given that the existing literature sees it as important to examine the social determinants of ACEs () and that ACEs are classified as one social determinant of health (; ; ; ), because it is well known that disabled people have problems with obtaining a good level of various social determinants of health and ableism is seen as one structural problem to obtain the desired level (). As such, actions of elimination of ACEs of DCY due to ableist judgments and disablist treatments are warranted. Not only that, the very issue of experiencing ableist judgments and disablist treatments needs to be treated as an ACE.

But in order to move into action, the problem has to be made visible. One can do this by highlighting the negative impact of structural ableism and disablism on the health and well-being of disabled people (). And this should be carried out for the different characteristics exhibited by disabled people. Furthermore, this has to be performed in such a way so that it reflects all the ways disabled people see their body/mind with the options being (a) that they see it as an impairment/defect and (b) that they see it as a variation of being. The ACE academic literature we covered does not allow for a positive identity linked to being a DCY (option b), which, for example, is used by people adhering to Deaf culture. Indeed, even if disability is not used as a synonym for “health issue”, disability is positioned as a negative consequence when disability is defined as “(self-reported activity limitation and/or assistive device use)” (), which still does not allow for option b.

And the conceptualization of ACE has to reflect all the options disabled people of all ages can identify as the origin of the disablement, with the options being (a) their body/mind characteristic, (b) how they are treated by society, or (c) both. In our pre-research we found one measure, the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (ACE-Q), from the Center for Youth Wellness, whose wording, “You have often been treated badly because of race, sexual orientation, place of birth, disability or religion” (), suggests that it could be used to cover that DCY experience ACE because of being negatively judged and treated as DCY. However, not one of our sources mentioned the ACE-Q or the Center for Youth Wellness.

There are numerous instruments that cover ableist microaggressions (; ; , ; ; , ; ; ; ), which could be used to make visible the ACE of ableist judgment and disablist treatment, that ableism and disablism are risk factors for increased ACE exposure, and that they produce barriers to identifying, treating, or responding to ACEs.

If we look at the disciplinary origin of our results in, for example, Scopus, our findings are even more problematic. Of the 6320 abstracts covering ACE, 4359 were classified under medicine, which makes sense given the origin of the ACE discourse. However, 1268 were classified under social science and 143 under arts and humanities, reflecting that ACEs are not only a medical topic of interest. Furthermore, all major disability studies journals are present in the databases we used and would be classified under social science. As such, it is problematic that there were only 35 relevant sources and that none of the 35 relevant sources none were from journals with “disability studies” in the title. It is also problematic that disability studies and other disability rights terms (Table A1) have no hits or only one hit. Indeed, in our qualitative analysis, only one source engaged with disability studies concepts and theory (), whereby this is the Journal of Human Trafficking, not a disability studies journal. Furthermore, only one of our 35 sources came from a journal linked to disability studies (Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research) covering deaf adults ().

Mental Health

Although we did not use the term “mental health” in our search strategy due to the problem with false positives, we used strategy 13 as a source for ableism and disablism in general. Table A1 shows that the term “adverse childhood experience” was only mentioned once, in the same abstract we already covered within the 35 relevant sources (). At the same time there were 393 hits with mental health (Table A1). In the end there were 19 abstracts that mentioned ableism in relation to mental health (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ). None used the term disablism. However, within these sources it is noted that 86% of respondents noted that ableism experienced in schools is associated with “poor mental health outcomes in disabled students”; that ableism hinders the building of “protective disability identities” and “negatively impact school staff, including teachers who describe this as causing stress and frustration in their work” (), and that “isolation from peers, bullying, gaps in adjustments” were identified as forms of ableism (). Within this study, it was also noted that the ableist judgment and disablist treatment were not isolated but “chronic difficulties built up over time to create feelings, such as persistent stress, frustration, and exhaustion” ().

This characterization of ableist judgment and disablist treatment would allow us to see this as an ACE based on these proposed five characteristics of ACEs based on the literature (harmful, chronic, distressing, cumulative, and varying in severity) ().

Health themes included general stressors, bodily health, mental health, and social determinants of health (). Ableism was classified as an unacknowledged health risk (). Internalizing ableism was flagged to cause mental health problems (; ; ). For example, “disability microaggressions had direct effects on internalized ableism and mental health symptoms” and “internalized ableism had direct effects on mental health symptoms” (). Ableism in mental healthcare was also flagged (; ; ). The remainder of the abstracts only mentioned “mental health” and the ableism term in the same abstract, without more details and no wording on how they are linked. However, as many ACEs are linked to “mental health” issues and as ableism/disablism is recognized to cause mental health issues indicates that the ACE literature should engage with ableism/disablism conceptually, empirically and policy development-wise.

4.2. Prevalence: DCY Have Higher Prevalence of ACEs than Non-Disabled Youth

As to prevalence, within 8 of the 29 full texts it is noted that DCY have higher rates of ACEs than non-disabled youth (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ). In 13 of the 29 full texts, it is noted that ADHD/autism/attention deficit/neurodiversity/neurodivergence youth have higher rates of ACEs than non-disabled youth (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ). Higher rate of abuse of DCY is flagged as the main reason for the higher rate of ACEs DCY experience (; ; ; ; ; ). Stigma, discrimination, bullying and ignorance about disability were noted as factors which place DCY at higher risk of violence and with that ACEs (; ; ; ).

At the same time, it is well known that disabled people of all ages disproportionately experience most, if not all, of the ACEs linked to the social environment. As such, this asks for many studies to investigate to what extent DCY experience all ACEs due to ableist judgments and disablist treatment.

4.3. Cause of the ACE

As to which ACEs are mentioned, all our relevant sources covered the 10 initial ACEs. We found only nine sources that covered ACEs beyond the initial 10 ACEs mentioning 23 different ACEs with peer bullying being number one mentioned in seven of the nine sources.

Income, socioeconomic status, and poverty, which are seen as ACEs (; ; ; ; ; ; ), were mentioned in our nine sources under different wordings, such as economic hardship (), extreme hardship due to family income (), children with socioeconomic hardship (), income insufficiency (; ; ), and two could be linked to it under food scarcity/insecurity () and food/housing insecurity (). But these ACEs could be covered much more given that “the proportion of persons with disabilities living under the national or international poverty line is higher, and in some countries double, than that of persons without disabilities” (), see also ().

Then some of ACEs of the social environment mentioned in the ACE literature were not mentioned in our sources. To give some examples; it is argued that ACEs increase the chance to exhibit climate stress (), and ecoanxiety, climate change, and natural disasters are labeled as adverse childhood experiences (; ). However, the issue of climate change, eco-anxiety and environmental issues, such as emergencies and disasters were not mentioned in our relevant sources, although disabled people of all ages are disproportionately impacted by environmental issues such as climate change and disasters (; ; ; ; ; ; ; , ; ; ; ; ).