1. Introduction

Resilience refers to the capacity of a dynamic system to adapt successfully to disturbances that threaten its functioning or development (

Masten, 2014). In sports, athletes face stressors such as injuries, performance pressure, and competition outcomes. The ability to cope with such adversity is known as psychological resilience and contributes not only to performance but also to well-being (

Sarkar & Fletcher, 2016). Although resilience has traditionally been treated as an individual trait, recent research emphasizes that it also operates at a collective level, giving rise to the concept of team resilience, defined as the team’s collective capacity to respond to challenges and pursue shared goals (

Morgan et al., 2013). Team resilience is fostered by interpersonal communication, mutual support, and collaborative learning (

Szabadics et al., 2025). Among its determinants, leadership is critical (

Morgan et al., 2019).

In sport, leadership is defined as the process of influencing team members to achieve collective objectives (

Northouse, 2016). Among leadership styles, transformational leadership (TFL)—characterized by inspiring a shared vision, modeling ideal behavior, and encouraging intellectual growth—has been widely studied in sport contexts (

Bass & Riggio, 2006). TFL has consistently been associated with higher athlete motivation, performance, and well-being (

Hoption et al., 2014;

Lopez et al., 2021;

Stenling & Tafvelin, 2014). Traditionally, research has emphasized coaches as the primary leaders (

Cotterill, 2012). Research into leadership development and programs for coaches has naturally attracted attention (

Turnnidge & Côté, 2017;

Moen et al., 2025). However, recent studies highlight the importance of shared leadership, involving not only head coaches but also captains and athlete leaders (

Cotterill & Fransen, 2016). For example,

Andrews et al. (

2022) observed in cricket teams that captains relied on athlete leaders for tactical decision-making, while coaches expected athlete leaders to support communication and cohesion. The learning of youth sports is linked not only to coaches but also to players through interaction, who supported them in applying their learning and effort and strengthening teamwork (

Anderson-Butcher et al., 2025). These roles, although sometimes overlapping, may exert distinct influences on team functioning (

Price & Weiss, 2013;

Fransen et al., 2020).

Additionally, motivational climate is a key contextual factor shaping team dynamics. Defined as athletes’ perceptions of the team learning environment, it is typically distinguished as task-involving climate (focused on effort and personal growth) or an ego-involving climate (focused on outperforming others) (

Ntoumanis & Vazou, 2005). TFL has been shown to foster task-involving climate, which in turn supports team cohesion and sustained effort (

Kao & Watson, 2017;

Alvarez et al., 2019;

Erikstad et al., 2021). In high-performing teams, particularly in rugby, shared TFL has been linked to stronger task-involving climate and ultimately to greater team resilience (

Hodge et al., 2014;

Morgan et al., 2015). Considering the characteristics of rugby, coaches’ instructions to players during matches are limited, affording players greater opportunities for independent decision-making. Furthermore, with fifteen players per side—a larger squad than in many other sports—numerous distinct positions exist. Consequently, not only during matches but also in training sessions and team meetings, a shared understanding of team strategy, interpersonal relationships, and mutual support among players becomes crucial. In line with achievement goal theory (

Nicholls, 1984), we therefore focused on athletes’ shared perceptions of the team’s motivational climate (i.e., the extent to which effort, learning, and cooperation vs. social comparison are emphasized) as the primary mediating construct linking leadership to resilience. Motivational climate provides a proximal, theoretically grounded indicator of the psychosocial environment that can encompass other processes such as cohesion, efficacy, and trust, which we identify as important additional mediators for future research. More recently, studies have suggested that authentic leadership may also foster resilient team environments by enhancing psychological capital and interpersonal functioning (

Kavussanu et al., 2024;

Zhang & Fan, 2025).

Among American college athletes, the importance of promoting youth development through fair decision-making and relational trust has been emphasized (

Han & Ha, 2025). In Japan, high school sports are characterized by hierarchical structures and collectivist values, which may shape leadership processes differently from Western contexts. Prior work has reported a positive association between coaches’ TFL and youth athletes’ positive development, but the pattern appears to differ from that observed in American samples (

Nakayama & Izawa, 2025). Despite this growing body of research, few studies have examined these dynamics in non-Western or youth elite settings, and almost none have addressed how multiple leadership roles jointly influence team resilience through motivational climate.

The present study addresses this gap by focusing on Japanese elite high school male rugby teams and examining how TFL enacted by head coaches, captains, and athlete leaders relates to team resilience through differences in motivational climate. Prior research has often conceptualized athlete leaders as informal figures who influence peers without formal authority. We define them here as formally designated vice captains and positional leaders (excluding the captain) who provide tactical and social leadership within their units, fostering communication, cohesion, and on-field decision-making. Unlike much prior work, our approach treats these constructs as athletes’ self-reported, individual-level evaluations of team-level processes, enabling analysis despite the limited number of teams. This framing allows us to examine pathways through which leadership roles may shape motivational climate and team resilience. Based on this framework, we hypothesized that (a) head coaches’, captains’, and athlete leaders’ TFL would be positively associated with task-involving climate and negatively associated with ego-involving climate, (b) captains’ TFL would show both direct and indirect associations with team resilience via motivational climate, and (c) head coaches’ and athlete leaders’ TFL would be linked to team resilience primarily through higher task involvement and lower ego involvement.

This study makes three contributions:

- −

It extends leadership and team resilience research to a non-Western, youth elite context where cultural and structural factors may alter leadership effects.

- −

It differentiates the pathways associated with TFL across three distinct leadership roles, highlighting the unique contribution of athlete leaders.

- −

It provides a methodologically transparent model based on athlete self-reports, relevant for contexts where multilevel data are unavailable.

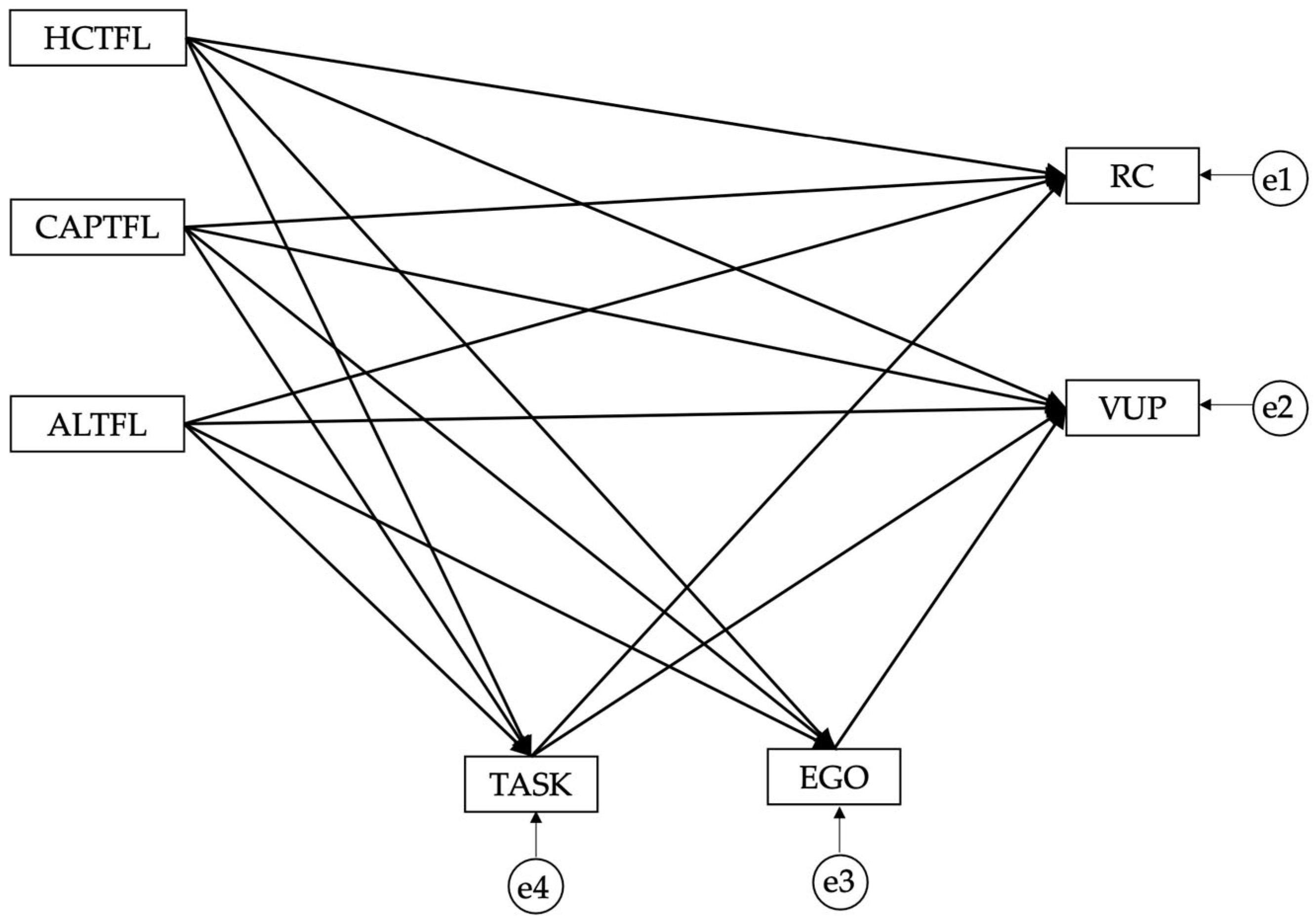

By elucidating these pathways, this study offers practical implications for leadership development in elite youth sports, particularly in culturally structured environments such as Japanese rugby. The hypothesized model is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study employed a cross-sectional survey design to examine the associations between transformational leadership, motivational climate, and team resilience in elite Japanese high school rugby teams. All variables were assessed through athletes’ self-reported perceptions using validated questionnaires, and the hypothesized pathways were tested using structural equation modeling (SEM). The methodological procedures—including participant recruitment, measurement instruments, and analytic strategy—are described in detail below.

2.2. Participants and Procedures

This study targeted elite-level male high school rugby teams (grades 10–12) in Japan that regularly participate in national tournaments or top regional leagues, representing a high-performing segment of school-based rugby. Within this target population, we used a purposive (non-probability) sampling strategy: the first author (T.H.) approached head coaches and staff of eligible teams through existing competitive and professional networks and invited them to participate in the study. Eight teams agreed to take part. The participating schools were located in five regions (Kanto, Kansai, Hokuriku, Shikoku, and Kyushu), providing geographical dispersion, and included three public and five private high schools. Data were collected in September 2024 from 382 invited athletes. After the study was explained to head coaches and team permission was obtained, written informed consent was secured from athletes and their parents via the coaches. Participants first viewed an explanatory video describing the study aims and procedures, followed by an online briefing. Surveys were then administered anonymously online to ensure confidentiality and minimize response bias. Twelve participants with missing data were excluded, resulting in 370 valid participants (valid response rate: 96.9%). Participants were 16–18 years old (M = 16.89, SD = 0.86), with an average playing history = 6.38 years (SD = 4.39) and team tenure = 1.38 years (SD = 0.86) (see

Table 1). The study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Graduate School of System Design and Management, Keio University (Approval Number: SDM-2024-E026), and all procedures adhered to ethical guidelines for research involving human participants.

2.3. Measures

This study utilized validated self-report questionnaires to assess TFL, motivational climate, and team resilience.

2.3.1. Transformational Leadership

TFL was assessed using the Japanese-adapted Differentiated Transformational Leadership Inventory (

Callow et al., 2009;

Araki & Kodani, 2018). The scale consists of 27 items across seven subscales, rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (all the time), with higher scores reflecting greater transformational leadership. Consistent with prior research, six subscales were employed because they emphasize transformational behaviors: individual consideration (4 items); inspirational motivation (4 items); intellectual stimulation (4 items); fostering acceptance of group goals and teamwork (3 items); high-performance expectations (4 items); and appropriate role model (4 items). The contingent reward subscale was excluded due to its focus on transactional leadership (

Podsakoff et al., 1990). A composite score of TFL was then created by combining the six subscales (

Batten et al., 2025). Participants evaluated the TFL behaviors of three leadership figures: the head coach, the captain, and athlete leaders (vice captains and positional leaders, excluding captains). In this study, head coaches were responsible for the overall management and coaching. Captains and athlete leaders were players formally designated by the coaching staff or team to support both tactical and psychological aspects of team functioning. The captain serves as the team’s symbolic leader, representing the players externally and embodying the team’s values. Captains deliver official speeches after matches, act as the final decision-maker during player meetings and matches, and bridge the gap between coaches and players (

Mosher, 1979;

Dupuis et al., 2006). Captains’ TFL behaviors have been linked to task cohesion, whereas athlete leaders’ TFL may preferentially foster social cohesion (

Callow et al., 2009;

Price & Weiss, 2013). In this study, athlete leaders were defined as formally identified players (e.g., vice-captains, unit or positional leaders) who complement the captain by providing role-based support, such as facilitating peer communication, offering tactical guidance, and promoting team cohesion during practices and matches. The psychological burden tends to be greater for captains (

Camiré, 2016;

Smith et al., 2017;

Fransen et al., 2014). Thus, while the roles of captains and athlete leaders partially overlap, they differ in formal authority, symbolic visibility, and the mechanisms through which they influence teammates, and were therefore treated as distinct leadership categories. The wording of each item was adapted to match the respective leadership role. For example, the item for the head coach was “The head coach leads by doing rather than simply telling.” The corresponding items were “The captain leads by doing rather than simply telling” and “The athlete leader leads by doing rather than simply telling.”

2.3.2. Motivational Climate

Motivational climate was assessed using a 15-item scale comprising two factors: task-involving climate (TASK: 11 items) and ego-involving climate (EGO: 4 items). Items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The scale was developed based on the Peer Motivational Climate in Youth Sports Questionnaire (PMCYSQ,

Ntoumanis & Vazou, 2005) and has been validated among Japanese high school athletes (

Hirose et al., 2025). In that validation study, the Japanese version demonstrated strong psychometric properties. In the present research, reliability coefficients and model fit indices for all measurement instruments are reported in the

Section 3 for consistency across scales.

2.3.3. Team Resilience

Team resilience was assessed using the Japanese version of the Characteristics of Resilience in Sports Teams Inventory (CREST), originally developed by

Decroos et al. (

2017) and adapted into Japanese by

Araki and Kodani (

2018). The CREST comprises two factors: Resilience Characteristics (RC, 12 items) and Vulnerabilities Under Pressure (VUP, 8 items). RC captures the extent to which a team demonstrates resilience-related attributes such as collective problem-solving, adaptability, and maintaining a positive mindset under adversity. VUP reflects the degree to which a team exhibits vulnerabilities when exposed to stressful conditions, such as performance pressure or setbacks. Items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) (

Decroos et al., 2017). Higher RC scores indicate stronger resilience characteristics, whereas lower VUP scores suggest reduced vulnerabilities to stress. In the current study, the CREST was used to capture team resilience as athletes’ self-reported, individual-level evaluations of team process, rather than aggregated team-level outcomes.

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, skewness, kurtosis, and correlations among observed variables) were calculated for all measures. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was then employed to examine the hypothesized relationships among TFL, motivational climate (TASK, EGO), and team resilience (RC, VUP). Although the dataset was nested within eight teams, all variables in this study—transformational leadership, motivational climate, and team resilience—were conceptualized and measured as individual athletes’ subjective perceptions of team processes. Accordingly, the individual athlete represented the most appropriate theoretical unit of analysis. Additionally, the number of teams was insufficient for conducting reliable multilevel modelling. Methodological guidelines indicate that multilevel SEM typically requires at least 20–30 clusters; given that only eight teams participated, multilevel analysis would likely produce biased or unstable estimates. For these reasons, and consistent with prior research utilizing perceptual measures under similar conditions, we analyzed the data at the individual level to preserve meaningful within-team variability in athletes’ perceptions and ensure methodological appropriateness. SEM was selected over simple regression to allow the simultaneous estimation of multiple direct and indirect pathways within a multivariate framework. Although the TFL scale was adapted for each leadership role by changing only the referent (head coach, captain, athlete leader), all versions retained the same items and factor structure, in line with prior research. Formal measurement invariance testing (e.g., configural, metric, scalar invariance) across roles was not conducted because our aim was not to compare latent means between roles, but to model each role-specific TFL perception as a separate predictor within the SEM. Model fit was evaluated using the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), with thresholds for acceptable fit set at GFI > 0.90, CFI > 0.90, and RMSEA < 0.10. Indirect effects were tested using bias-corrected bootstrapping with 5000 resamples to generate 95% confidence intervals. For all SEM analyses, unstandardized coefficients (B) and standardized coefficients (β) were estimated and reported. All analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics 29 and AMOS 29.

3. Results

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for TFL, motivational climate, and team resilience. For TFL ratings, the mean score was 4.19 (SD = 0.64) for head coaches, 4.12 (SD = 0.64) for captains, and 4.04 (SD = 0.62) for athlete leaders. For motivational climate, the mean score was 5.83 (SD = 0.71) for task-involving climate (TASK) and 3.15 (SD = 1.22) for ego-involving climate (EGO). Regarding team resilience, the mean score was 5.67 (SD = 0.76) for resilient characteristics (RC), and was 2.84 (SD = 1.04) for vulnerabilities under pressure (VUP).

The correlation analysis (

Table 3) showed that TFL was positively correlated across leadership roles and positively associated with both TASK and RC. Specifically, head coach TFL (HCTFL), captain TFL (CAPTFL), and athlete leader TFL (ALTFL) were all significantly positively correlated with TASK (r = 0.51–0.55,

p < 0.001) and RC (r = 0.29–0.35,

p < 0.001). In contrast, all three leadership figures were negatively correlated with both EGO (r = −0.32 to −0.36,

p < 0.001) and VUP (r = −0.14 to −0.16,

p < 0.01), indicating that a higher level of TFL was linked to less EGO and reduced VUP.

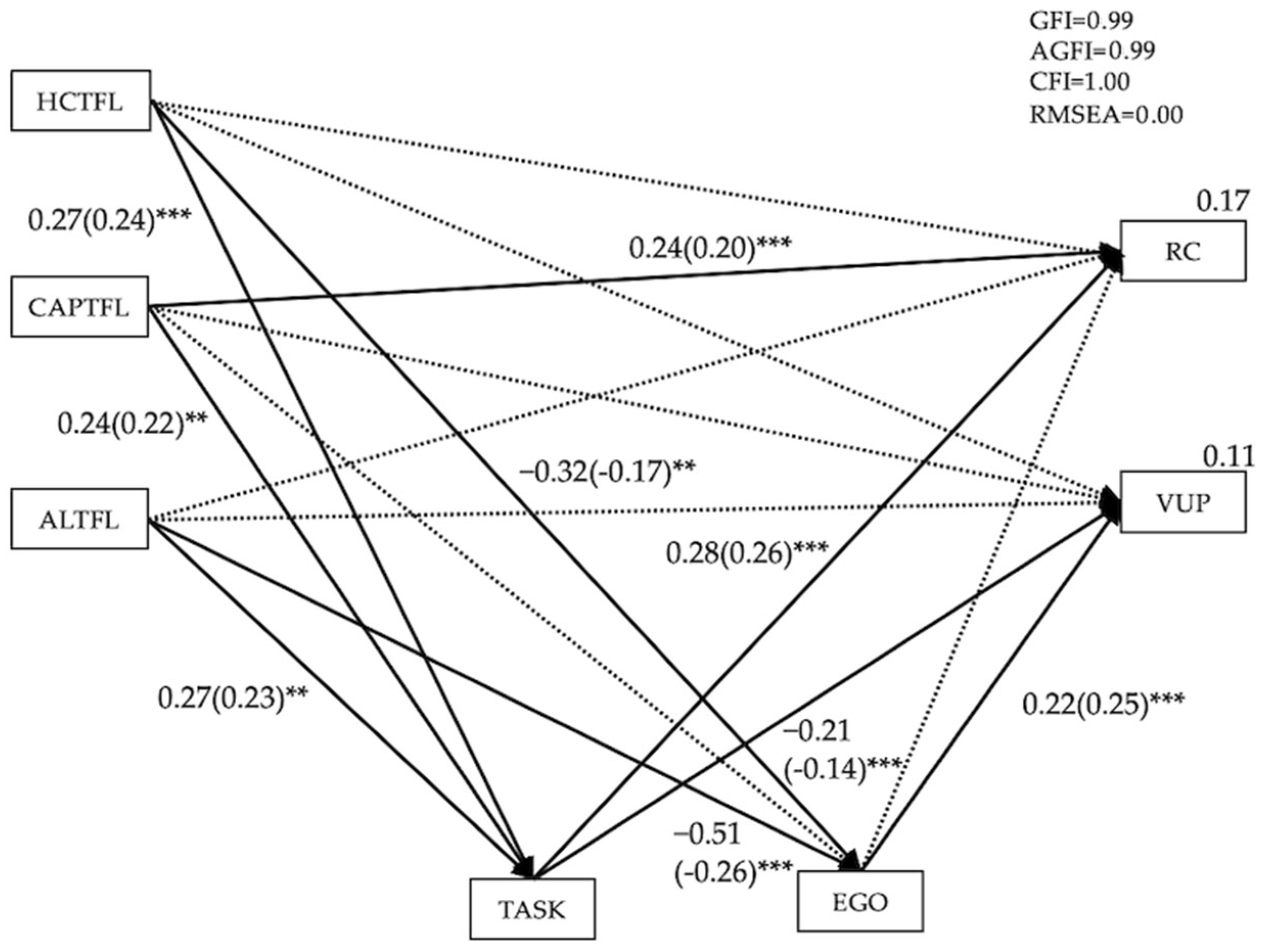

SEM was conducted to examine the hypothesized pathways among TFL, TASK, EGO, RC, and VUP (

Figure 2). The model demonstrated good fit, with GFI = 0.99, AGFI = 0.99, CFI = 1.00, and RMSEA = 0.00.

As shown in

Figure 3, HCTFL was significantly positively associated with TASK (B = 0.27, β = 0.24,

p < 0.001) and negatively associated with EGO (B = −0.32, β = −0.17,

p = 0.005), but not directly associated with RC or VUP. CAPTFL was positively associated with TASK (B = 0.24, β = 0.22,

p = 0.001) and directly associated with RC (B = 0.24, β = 0.20,

p < 0.001), but showed no significant associations with EGO or VUP. ALTFL was positively associated with TASK (B = 0.27, β = 0.23,

p = 0.002) and negatively associated with EGO (B = −0.51, β = −0.26,

p < 0.001), but did not show significant direct effects on RC or VUP. Regarding motivational climate, TASK was positively associated with RC (B = 0.28, β = 0.26,

p < 0.001) and negatively with VUP (B = −0.21, β = −0.14,

p = 0.009), whereas EGO was positively associated with VUP (B = 0.22, β = 0.25,

p < 0.001).

Indirect effects were examined using bias-corrected bootstrapping with 5000 resamples. HCTFL showed significant indirect effects on RC through TASK (B = 0.07, β = 0.06, p < 0.001) and on VUP through both TASK (B = −0.06, β = −0.03, p = 0.009) and EGO (B = −0.07, β = −0.04, p = 0.009). CAPTFL showed a significant indirect effect on RC through TASK (B = 0.07, β = 0.06, p < 0.001) and on VUP through TASK (B = −0.05, β = 0.03, p = 0.009). ALTFL demonstrated significant indirect effects on RC through TASK (B = 0.07, β = 0.06, p < 0.001) and on VUP through both TASK (B = −0.06, β = 0.03, p = 0.009) and EGO (B = −0.11, β = −0.07, p = 0.009).

4. Discussion

This study examined the pathways linking transformational leadership and shared leadership with motivational climate and team resilience among elite high school rugby players in Japan, using SEM at the individual level. This study can be interpreted within transformational leadership theory and achievement goal theory. The overall pattern of associations among TFL, motivational climate, and team resilience was broadly consistent with Western findings, but was observed within a Japanese school-based sport context characterized by collectivism, hierarchical relationships, and strong respect for authority. The findings indicate that athletes’ perceptions of motivational climate account for how leadership roles are associated with team resilience, rather than suggesting direct causal mediation. Specifically, captains’ transformational leadership was linked not only to more task-involving climate but also directly to resilient characteristics, highlighting their central role in fostering adaptive team processes. Athlete leaders’ transformational leadership, in contrast, primarily shaped resilience indirectly by promoting task-involving climate and reducing ego-involving climate. Head coaches’ transformational leadership was associated with both greater task-involving climate and lower ego-involving climate, suggesting an indirect contribution to team resilience through motivational climate rather than direct effects. The results were consistent with the hypotheses of this study. Although the effect sizes were generally small to moderate, in applied team-sport environments, even modest improvements in perceived motivational climate or leadership behaviors can accumulate over time and influence athletes’ collective functioning, communication, and adaptability under pressure. The observed effects—while not large statistically—carry practical relevance for daily coaching interactions and leadership development in high-performance youth rugby settings.

Therefore, these patterns highlight the differentiated contributions of transformational leadership roles in shaping athletes’ perceptions of their team environment. Given the close, day-to-day interactions that captains and athlete leaders share with teammates during training, competition, and daily school life, they appear especially positioned to influence motivational climate processes. This aligns with conceptualizations of shared leadership as a distributed influence process, whereby the complementary strengths of head coaches, captains, and athlete leaders jointly shape athletes’ psychological and motivational experiences.

4.1. The Impact of TFL on Task-Involving Climate and Ego-Involving Climate

The present findings are broadly consistent with previous research indicating that coaches’ and athlete leaders’ transformational leadership can enhance team cohesion and collective functioning (

Price & Weiss, 2013;

Fransen et al., 2020;

Bosselut et al., 2020;

Smith et al., 2017). For example,

Kao and Watson (

2017) reported that coaches’ TFL in Taiwanese basketball teams was positively associated with task-involving climate and negatively associated with ego-involving climate. Consistent with this line of evidence, our results showed that head coaches’ TFL in Japanese high school rugby teams was positively associated with task-involving climate and negatively associated with ego-involving climate. Captains’ and athlete leaders’ TFL were also positively linked to task-involving climate, while athlete leaders’ TFL exerted the strongest negative association with ego-involving climate. In this study, the impact of each leader’s TFL on motivational climate and team resilience was distributed across roles rather than concentrated in a single leader, which is consistent with perspectives on shared or distributed leadership. Youth sport systems also differ structurally across countries. While community-based clubs are common in many Western settings, Japanese youth sport is typically organized around school-based teams, where athletes train, study, and socialize within the same institutional hierarchy. Our findings suggest that, even in this more hierarchical context, transformational leadership from coaches, captains, and athlete leaders is associated with task-involving climate and higher team resilience, indicating that the core mechanisms may generalize across cultural and organizational settings. Unlike traditional Japanese sports such as judo or kendo, rugby requires coordination between forwards and backs, and coaches are restricted from directly communicating with players during matches, which may further increase the importance of peer leaders in shaping motivational processes. Such constraints may limit the immediacy of coaches’ influence, making peer leaders particularly important in shaping motivational processes. Captains and athlete leaders, embedded within play and maintaining continuous peer contact, are well positioned to provide tactical guidance and psychological support that strengthen task orientation while mitigating ego-focused dynamics (

Cotterill & Fransen, 2016;

Fransen et al., 2020). Moreover, captains must balance leadership responsibilities with their own performance demands (

Smith et al., 2017), making exclusive reliance on a single formal leader suboptimal (

Carson & Walsh, 2018). Athlete leaders help distribute this burden, facilitating communication and peer support through transformational leadership that fosters perceptions of task-involving climate and reduces ego-involving climate. These observations underscore the functional value of distributed leadership structures in contexts where formal leaders face situational communication constraints.

From a cross-cultural perspective, these findings suggest that core transformational leadership principles can be applied in non-Western, school-based sport systems, but that leadership development programs should be adapted to local norms regarding hierarchy, authority, and collectivism. In Japanese contexts, for example, working explicitly with hierarchical systems such as senpai–kohai (senior–junior) relationships and school-based routines may help embed shared leadership practices in culturally congruent ways.

4.2. TFL, Motivational Climate, and Team Resilience

In shared leadership systems, the influence of transformational leadership may vary depending on leaders’ proximity to players, role expectations, and available communication channels. Captains and athlete leaders, embedded in daily interactions with teammates, appear particularly positioned to shape psychological processes linked to resilience. This study examined how TFL from different leadership roles was associated with athletes’ perceptions of resilient characteristics (RC) and vulnerabilities under pressure (VUP). The results revealed that captains’ TFL showed a significant direct association with RC, underscoring their central role in reinforcing resilience-related attributes. To enhance team resilience, especially captains may need to display transformational leadership consistently, not only during meetings, training sessions, and matches, but also throughout daily school life. In contrast, athlete leaders’ TFL did not directly predict RC or VUP, but operated indirectly by promoting task-involving climate and reducing ego-involving climate. Head coaches’ TFL also contributed indirectly, primarily by reducing ego involvement and thereby lowering vulnerabilities under pressure. These findings refine prior work in elite Turkish soccer, where coaches’ high-performance expectations—a subdimension of TFL—were positively associated with resilience (

Karayel et al., 2024). Differences in age group, sport type, competition structure, and cultural context may partly explain this divergence. In the present sample of adolescent male rugby players in Japan, both captains and athlete leaders were associated with team resilience through their influence on motivational climate, which emphasized task involvement and reduced ego-focused dynamics. These processes appear to mediate the link between transformational leadership and team resilience. This aligns with

Morgan et al. (

2015), who emphasized that team resilience emerges not only from transformational leadership but also from processes such as team learning, social identity, and positive emotions (

Morgan et al., 2017). The limited direct influence of head coaches on resilience may be explained by contextual constraints in rugby, where restricted in-game communication shifts the responsibility for adaptive responses to peer leaders who are positioned to make real-time adjustments.

Sarkar and Fletcher (

2016) have highlighted the importance of informal interactions and social activities in strengthening team resilience pathways.

Within this context, it becomes essential for head coaches to delegate authority effectively to captains and athlete leaders, and to support their leadership development and autonomous motivation (

Mosqueda et al., 2019). Such delegation can empower peer leaders to play an active role in guiding adaptive responses. Rather than merely creating formal opportunities for athlete input, coaches should deliberately foster transformational leadership in captains, athlete leaders, and themselves through repeated reflection on their feedback, role clarification, and responses to errors. Furthermore, our findings suggest that principles of transformational and shared leadership, and of motivational climate, should be explicitly included in curricula for school-based sport. Coach licensing and in-service workshops could incorporate basic modules on identifying, developing athlete leaders, and designing training activities that promote a task-involving climate and reduce ego-involving cues. In line with the theoretical perspectives above, the goal is to strengthen task-involving climate and minimize ego-involving cues, thereby enhancing resilience in ways consistent with the structural and cultural realities of Japanese elite youth rugby.

4.3. Implications for Practice

This study provides empirical evidence supporting the intentional integration of transformational and shared (i.e., distributed) leadership practices in Japanese youth team sports. The results highlight the distinct but complementary roles of captains and athlete leaders: captains exert direct influence on team resilience, whereas athlete leaders contribute primarily by shaping motivational climate that fosters task involvement and reduces ego involvement. Accordingly, empowering both groups is crucial for cultivating a climate that sustains resilience. Practical implications for coaches and practitioners include systematically identifying and developing not only captains but also athlete leaders who hold social capital within the team (

Alvarez et al., 2019). This can be achieved by (a) using observational assessments and social network analysis (e.g., peer nominations) to identify captains and athlete leaders who already hold informal influence within the team, and (b) providing these athletes with structured transformational leadership development programs (e.g., mentorship modules, reflective journaling, structured feedback sessions), thereby ensuring that leadership influence is effectively distributed across multiple team members. Leadership development initiatives should also be aligned with the values of Generation Z athletes, including closeness, commitment, co-orientation, and strong coach–player relationships (

Landman et al., 2024), for example, by incorporating real-time feedback apps and interactive workshops with case-based simulations. By integrating these values, interventions are more likely to resonate with athletes’ interpersonal expectations and thus increase their effectiveness. Moreover, combining mental skills training with leadership workshops can strengthen key competencies in communication, peer support, and tactical decision-making. Such strategies are particularly salient in rugby, where structural communication constraints limit coaches’ in-game influence and place greater responsibility on peer leaders to guide adaptive responses.

4.4. Limitations

First, the cross-sectional design precludes conclusions about temporal dynamics or causal directionality in the observed associations. Although SEM revealed both direct and indirect pathways linking transformational leadership, motivational climate, and team resilience, these relationships should be interpreted as correlational. Longitudinal or experimental, mixed-method designs are needed to capture developmental trajectories of leadership behaviors and to evaluate the stability of their influence on motivational climate and team resilience processes over time (

Cotterill et al., 2022). Second, the reliance on athletes’ self-reported perceptions, while consistent with the study’s aims, may have introduced several forms of response bias. For example, halo effects (

Neely et al., 2025) or confirmation bias may have led athletes to evaluate transformational leadership and motivational climate in globally positive or negative ways, independent of specific behaviors. Additionally, recent team performance (

Gibson & O’Connor, 2022)—such as winning or losing streaks—may have shaped athletes’ perceptions of leadership behaviors regardless of leaders’ actual actions, thereby inflating or attenuating observed associations. Future research should incorporate multiple data sources—such as coach ratings, peer nominations, behavioral observations, or objective performance indicators—to enhance construct validity. Third, the sample was limited to elite high school male rugby teams in Japan, which constrains the generalizability of the findings. In Japanese contexts, for example, athletes may fulfill performance expectations even in the absence of strong relational trust with coaches (

Han & Ha, 2025). Leadership structures, communication patterns, goal motives, and cultural norms may differ among female athletes (

Martínez-González et al., 2025) or in other sports. Comparative studies across sport types and gender groups to examine the robustness of observed pathways. For example, particularly in sports such as cricket, where captains carry more continuous and visible in-game leadership responsibilities (

Smith et al., 2017;

Cotterill, 2014), would help universal leadership in interactive team sports–motivational climate–resilience pathways from culture- or sport-specific dynamics. Fourth, we did not formally test the measurement invariance of the TFL scale across head coach, captain, and athlete leader versions; future studies with larger samples could examine invariance more rigorously when comparing latent levels of leadership across roles. Fifth, future research should integrate additional contextual and psychological factors that may facilitate or constrain the effectiveness of leadership, including team norms, psychological safety, parental attributes, anxiety, emotional intelligence, self-efficacy, and leader communication techniques (

Karayel et al., 2024;

Castro-Sánchez et al., 2019;

Ntalachani et al., 2025;

Bandura, 1997;

Edmondson, 1999;

Thomas et al., 2013). Finally, future research should examine the efficacy of distributed leadership training on team resilience and how specific dimensions of transformational leadership shape motivational processes, and evaluate the effectiveness of targeted interventions. Addressing these variables could inform evidence-based guidelines for leadership training that are sensitive to both cultural and structural characteristics of team sports.

5. Conclusions

The present study suggests that athletes’ perceptions of motivational climate are central in explaining how different leadership roles are associated with team resilience. Captains’ transformational leadership (TFL) was directly linked to resilience characteristics and also fostered more task-involving climate, which further supported resilience and reduced vulnerabilities under pressure. Athlete leaders contributed primarily through indirect pathways, promoting task involvement and reducing ego involvement, which in turn enhanced resilience and mitigated vulnerabilities. Head coaches’ transformational leadership was associated with both greater task-involving and lower ego-involving climate, contributing indirectly to higher resilience and fewer vulnerabilities. Together, these findings highlight the differentiated but complementary roles of head coaches, captains, and athlete leaders in shaping athletes’ psychological and motivational experiences. By clarifying these pathways at the level of individual perceptions, the study underscores the value of distributed leadership structures for supporting psychological functioning and adaptability in team sports. Practically, the results provide a foundation for TFL and motivational climate-focused leadership development strategies, particularly in contexts where formal leaders face communication or structural constraints during competition. Finally, by focusing on elite Japanese youth rugby, this study extends leadership and resilience research into a non-Western context, emphasizing the importance of cultural and structural factors in shaping leadership processes.