Abstract

Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) are perceived as safer than conventional smoking, but there is limited knowledge about their risks. This quasi-experimental study aimed to evaluate the perceived usefulness and acceptability of an innovative information strategy concerning the potential harms of e-cigarettes among university students in oral health programs in Mexico and Colombia. The methodology involved implementing a three-phase strategy, utilizing an interactive, self-managed educational game (bowling game) developed on the Genially digital platform and anchored in scientific evidence. Of the 230 invited students, 213 consented to participate in the initial phase. High engagement was demonstrated in the second phase, with 94.8% (n = 203) of students using the game for an average of 5 min and 16 s, and 25.62% answering all embedded knowledge questions correctly on the first attempt. Results from the acceptability phase (n = 36) were highly positive, with 72.2% of IUVA students and 19.4% of BUAP students agreeing the strategy was both entertaining and useful for knowledge improvement. The findings suggest that gamified and interactive digital learning strategies are highly accepted and strengthen academic commitment and knowledge acquisition regarding the public health risks of e-cigarettes. Further longitudinal studies are necessary to evaluate the sustained impact of these digital educational tools.

1. Introduction

Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS), like e-cigarettes and vape pens, have rapidly increased in popularity since 2005 (Singh et al., 2020). They are often seen as a safer alternative to regular smoking (Wang et al., 2021). ENDS attract both traditional smokers and youth due to their flavors (Bandi et al., 2022). However, their safety is still debated.

ENDS contain components such as nicotine, flavorings, formaldehyde, and heavy metals (Jenssen et al., 2019). Evidence shows e-cigarettes carry risks. While they may have fewer carcinogens than traditional cigarettes, they can still damage DNA. Users often report dry mouth, irritation, and oral ulcer (Saad et al., 2023). Furthermore, in vitro studies have broadly demonstrated that ENDS can induce DNA damage, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and genotoxicity in various cell types (Khalil et al., 2021; Petrella et al., 2025). Although causal evidence is limited, harmful substances like formaldehyde raise concerns about cancer risks (Cameron et al., 2023). Vaping is now a public health issue, especially among university students. Many young adults believe vaping is safer than smoking. Studies reveal that only about 70% recognize at least one harmful effect of nicotine, and around 35% think vaping is safer than traditional cigarettes (Bandi et al., 2022).

Health literacy is now seen as one of the most important aspects that affects health. Health literacy is the skills that determine an individual’s ability to access, understand, and apply health information (Sørensen et al., 2021). Low health literacy can increase disease rate (Nutbeam & Lloyd, 2020), and is linked to higher smoking rates (Sun et al., 2023). Approaches need to be customized to enhance health understanding according to various backgrounds (Stormacq et al., 2020).

Changing health-related behaviours is vital for health promotion, as this can prevent disease and reduce mortality. The field of behavioural epidemiology focuses on health promotion interventions based on specific theories of behaviour change (Davis et al., 2015). Research also indicates that small individual behaviours can significantly improve well-being. Behaviour change is mainly down to motivation, and there are different theories about what motivates people (Teixeira et al., 2012). But not all motivation is equal. According to Self-Determination Theory (SDT), there are two types: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic motivation refers to activities that satisfy basic psychological needs, resulting in will, readiness and enjoyment. By contrast, extrinsic motivation refers to activities performed to obtain a result that is separable from the activity itself, such as rewards or punishments. Extrinsic motivation frustrates autonomy and leads to reluctance, tension and coercion (Soundy et al., 2025). Recent years have seen SDT become a key framework for interventions and studies on healthy behaviours, with a large number of studies demonstrating the advantages of intrinsic motivation over extrinsic motivation (Davis et al., 2015). Intrinsically motivated behavior change is more sustainable. It also contributes to well-being by meeting one’s psychological needs (Davis et al., 2015). In our modern world, health and well-being depend largely on the healthy behaviours of each individual. Motivation is key for healthy behavior change. Intrinsically motivated behavior is desirable because it is sustainable and contributes to well-being.

Games that promote good health help change behaviour. Most of these influence good habits. A recent review found that around 1 in 5 digital behaviour change interventions use gamification (Taj et al., 2019). Gamification uses game design principles, like point-based systems and rules, to address real-world problems (Krath et al., 2021). The basic idea is to motivate people to do things for themselves and others, like exercise and study, in a gameful way. Previous research has found that gamification can improve behaviour, achieve desired outcomes, and improve experiences (Alsaleh & Alnanih, 2020; Huang et al., 2019). Gamification is already widely used in digital behaviour change interventions (Timpel et al., 2018), with studies suggesting it can improve health behaviours (Cheng & Ebrahimi, 2023; Theng et al., 2015).

Game-based learning is educational games that provide immersive, engaging, and effective learning experiences to achieve specific goals. Game-based learning has been demonstrated to offer challenges that match the player’s ability (Nguyen et al., 2023). This process creates a sense of flow and engagement, which in turn motivates participants to make behavioral changes. This approach enables autonomy and reduces the effectiveness of traditional health education (Tolks et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2023).

Furthermore, games offer a secure setting for experimentation and the acquisition of knowledge from failure (Davis et al., 2015; Tolks et al., 2020). Games can motivate behavior change and are a potential health tool, especially for oral health (Lakshmikantha, 2024). A number of studies have demonstrated the efficacy of utilizing computers and online games in health education and intervention (Jaccard et al., 2021; Lamb et al., 2018; Ullah et al., 2022). It is evident that board games generally exhibit superior engagement benefits and greater adaptability in aligning with the requirements of users.

Health professionals in training lack knowledge about vaping. They rely on unreliable sources like peers and social media instead of educational programs (Alhajj et al., 2022b; Alzalabani & Eltaher, 2020; Canzan et al., 2019). Studies suggest that oral health professional students generally lack sufficient knowledge about the harmful effects of vaping (Alhajj et al., 2022a; Natto, 2020; Thanki et al., 2024). Oral health professionals must be prepared to assess vaping’s health effects and educate on quitting and avoidance. Individuals who visit their oral healthcare professional regularly are likely to quit vaping if advised to do so (Wiener, 2023). This justifies the critical need for a targeted information strategy for future dentist professionals.

Interactive health literacy strategies can help fill knowledge gaps. Studies show that informative frameworks and gamification are effective in preventing tobacco use (Tolks et al., 2020).

A review shows that virtual games give healthcare trainees, including future dentists, useful evidence-based information (Madi et al., 2024; Thompson et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2021). Young people face a higher risk of e-cigarette use and its effects (Gentry et al., 2019). However, information on health literacy tools and gamification for oral health students in Latin America is limited.

This study addresses a gap in literature on health education about e-cigarettes and oral health by integrating evidence-based content and digital tools to improve health literacy among students. The study examines a gamified educational method aimed at improving vaping risk awareness among dentistry students in two countries. We hypothesize that this strategy will significantly enhance the perceived usefulness and acceptability of an innovative information strategy regarding vaping-related health risks, fostering positive attitudes toward evidence-based learning compared to traditional methods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Approach

The study used a quantitative, quasi-experimental, post-measurement design. It evaluated the perceived usefulness of an informative strategy about e-cigarette harms. The strategy and instruments were designed using best practices from the scientific literature and an EBM approach (Halalau et al., 2021). A review of the evidence on potential harms of e-cigarettes for oral health and the most effective educational strategies for young university populations was performed.

2.2. Setting and Participants

The study population comprised university students enrolled in Stomatology/Dentistry health programs from two university institutions: the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Puebla, in Mexico, and the Institución Universitaria Visión de las Américas, Pereira, in Colombia.

A non-probabilistic convenience sample was used, consisting of students enrolled in the current academic period. Sampling was conducted through intentional sampling (by intent to participate). The invitation to participate, the link to the informed consent form, the link to the game, and subsequently the link to the strategy acceptability questionnaire were all electronically transmitted to students via institutional email. The goal was to achieve participation from at least 30% of the students enrolled in the participating health programs or a minimum of 100 participants from each institution.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria required active course enrollment, and voluntary participation. Students who gave their consent to participate, accessed the educational material of the strategy, and participated in the project within the established timeframe were included. Although there were no formal exclusion criteria because participation was free and voluntary, submissions that did not complete all items or corresponded to students in the universities’ health programs were eliminated from the database to achieve the study’s purpose.

2.4. Intervention Strategy

2.4.1. Implementation of the Three-Phase Strategy

The educational intervention was divided into three sequential phases, which were carried out between February and July 2025. This ensured systematic implementation and participant follow-up.

Phase 1 consisted of a visual campaign designed to generate interest and awareness among potential participants. Visual materials emphasizing the risks of vaping were displayed and shared via email on campus. These emails were sent several times to encourage student participation. Students motivated to participate by the initial visual campaign could access the provided QR code. This directed them to the online informed consent form for the intervention. Those who gave their informed consent via the online form received a link to access the intervention game.

Phase 2 entailed the implementation of a gamified educational strategy, which was made available through a QR code that redirected to the Genially platform. This phase included initial data collection via an online form, which recorded basic demographic and academic information. Then, students interacted with a digital bowling game that incorporated evidence-based questions about the health risks of e-cigarettes. The game provided immediate feedback and explanations based on evidence. If they answered incorrectly, the game directed them to an explanation of the correct answer before returning them to the question.

Phase 3 involved evaluating the acceptability of the strategy, which was conducted two months after the intervention via an electronic follow-up questionnaire. This stage assessed student satisfaction, motivation and perceived knowledge improvement using a validated instrument.

2.4.2. Synthesis of Scientific Evidence

The current e-cigarette literature shows this is a growing but new field. It is characterized by a wide range of research methods and the quality of the evidence varies. Many studies highlight potential risks associated with e-cigarette use. These include periodontal disease, oral microbiome alterations, and carcinogenic effects. However, there remains considerable heterogeneity in study designs, populations, and outcome measures. Because most studies are cross-sectional or in vitro, causal inference and long-term risk assessment are limited. Moreover, confounding factors such as dual use with traditional cigarettes and inconsistent product compositions complicate interpretation. Despite limitations, literature emphasizes that e-cigarettes are not harmless and require further investigation to clarify oral health implications. A broad synthesis was made to design the informative strategy, this is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Broad synthesis of evidence about risk of e-cigarettes.

2.5. Informative Strategy (Intervention)

The educational strategy was designed to be visually attractive, facilitate digital interaction, and avoid participant saturation. The design was a web-based “bowling game” developed on the Genially digital platform. The game followed a simple, 10-min linear path, with low difficulty to suit non-experts.

The information strategy involved asking students a series of questions to assess their knowledge of the impact of e-cigarettes on oral and general health. Students were given hypothetical situations where they could provide information to family members, friends, or patients. The questions were designed so that students would not feel interrogated directly, but would instead draw on their prior knowledge. If they gave an incorrect answer, they were directed to interactive images providing scientific evidence to expand their knowledge, after which they could return to the questions.

The topics covered by the questions were:

Do you think electronic cigarettes are an effective method for quitting smoking, or do they just replace one habit with another?

Would you say that electronic cigarettes are less harmful than tobacco cigarettes?

Is the vapor from e-cigarettes less harmful than tobacco smoke for those who inhale it involuntarily?

Do you think that the sweet flavors and eye-catching packaging of e-cigarettes mean that they have no side effects?

Is there any risk posed by e-cigarette batteries, or do they eliminate any danger?

Do you believe that e-cigarettes do not have the same effects on the oral cavity as conventional cigarettes?

Do you believe that e-cigarettes have less impact on cardiopulmonary health?

2.6. Instruments for Evaluation

The evaluation of the strategy’s perceived usefulness and acceptability was conducted using the Cooperative Learning Strategy Motivation Questionnaire (CMELAC), which had been previously validated. The CMELAC questionnaire was used to assess students’ motivation in learning. This questionnaire has 16 items with 1–7 Likert-type response options (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) in its Spanish-language version, which has been validated (Manzano-León et al., 2021). The questionnaire is structured into four dimensions: Motivation (analyses students’ drive and interest in tasks presented through gamified methods); Learning (analyses perceived improvements in knowledge and understanding resulting from playful strategies); Teamwork (analyses quality of collaborative efforts and interactions among peers during gamified activities); and Flow (analyses state of immersion and optimal engagement experienced during activities). Higher scores represent a greater approach to the constructs measured in these categories. The questionnaire underwent rigorous validation processes, including Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), which demonstrated its factorial structure, content validity and internal consistency. Cronbach’s α scores for each dimension exceeded 0.70, indicating strong reliability.

2.7. Pilot Testing

A pilot test was carried out with groups of up to 10 students from both participating institutions. The goal was to ensure the questions and the informative strategy were culturally friendly and comprehensible. The pilot assessed the comprehension of the information, visual appeal, and acceptability of the terms used. Adjustments were made iteratively until student satisfaction was achieved. Dentists and specialists were also invited to evaluate the questions, and their recommendations were incorporated.

2.8. Ethical and Data Management Considerations

Participants were informed that their data would be used solely for academic and research purposes. All participants received information about the study objectives and procedures and provided informed consent prior to participation. Participation was voluntary, and anonymity/confidentiality of responses was ensured. Participants received a copy of their responses via the registered email. Under Colombian statutory law (Ley Estatutaria 1581 of 2012 and Ley 1266 of 2008), the institutional email addresses collected were not considered sensitive data. The treatment of information was authorized by law for the historical, statistical, or scientific objectives of this research project.

2.9. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used in the data analysis, including measures of central tendency and dispersion for quantitative variables and percentages for qualitative variables. Continuous variables were compared based on various participant groups (e.g., age, sex, educational program, semester). Non-parametric tests were used because the data did not meet key parametric assumptions. Specially, group sizes were unequal. Under these conditions, non-parametric procedures such as the Kruskal–Wallis test provide a more robust and appropriate approach for comparing groups.

Concerning the construction of graphs and tables, data were entered into Microsoft Excel. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA (Version 17) analysis software.

3. Results

The results section presents the findings from the three-phase implementation of the digital information strategy. First, we describe participant recruitment and engagement across phases. Then, we present the performance patterns observed during interaction with the gamified tool. At last, we present an overview of how the intervention was received and used within both academic settings, as well as students’ perceptions and acceptability of the strategy.

3.1. Demographic Data from the Survey

The aim of this study was to analyze at least 100 responses from each university. A total of 230 students accessed the initial electronic survey distributed between 1 February and 31 July 2025. Of these, 213 (92.6%) agreed to participate. The overall student participation rate was approximately 20.9% (213 participants out of a total of 1017 full-time undergraduate and graduate students).

3.2. Student Demographics

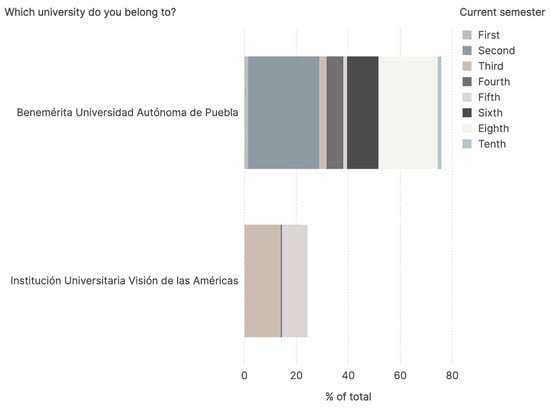

Of the 213 participants in the study, 163 (75%) were from Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, and 52 (25%) were from Institución Universitaria Visión de las Américas. Only students from the Stomatology or Dentistry programme participated in this study, according to the definition of each university. The average age of all participants was 21.5 years, with a median age of 20.3 years (±2.56 years). Of the 213 participating students, several semesters were represented (Figure 1). Between the two universities, 160 (74%) women participated.

Figure 1.

Semester and university of the participants.

Informative Strategy (Intervention)

The evaluation of the information strategy concerning the health risks of e-cigarettes for university students enrolled in oral health programs was conducted in three phases.

- Phase 1: Expectation Campaign and Participant Characterization

The initial invitation was sent via institutional emails to students, including a QR code for them to provide consent. Of the 230 students invited, 163 from Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla (BUAP) (70.9%) and 52 from Institución Universitaria Visión de las Américas (22.6%) consented to participate. A total of 15 students (12 from BUAP, 5.2%; 3 from Visión de las Américas, 1.3%) expressed that they did not want to participate, and their data were removed from the final list.

The characteristics of the participants who consented during this first phase are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the participants.

- Phase 2: Interactive Game (Informative Strategy Implementation)

A total of 203 students participated in the second phase, which involved accessing an informative strategy designed as an interactive Genially game. The average time spent using the game was 5 min and 16 s, with a range between 0 and 11 min. Table 3 presents the participants’ performance based on the number of correct responses to informational questions.

Table 3.

Performance of the participants according correct answers.

The results showed that the majority of students (50.74%) made at least one error in their responses. However, the number of students who answered all questions correctly on the first attempt (n = 52) was greater than those who made two or more errors (n = 47). Of the participants in this phase, 150 (73.9%) were female.

A Kruskal–Wallis test indicated a statistically significant difference among university groups for the variable Current university (χ2(2) = 7.20, p = 0.027), although the effect size was small (ε2 = 0.036). However, post hoc pairwise comparisons did not reveal significant differences between specific groups after correction for multiple testing. The contrasts between All answers were correct and At least one mistake (W = 3.01, p = 0.084), All answers were correct and Two or more mistakes (W = −0.05, p = 0.999), and At least one mistake and Two or more mistakes (W = −2.96, p = 0.092) were all non-significant. These results suggest that although overall differences were detected, no particular pair of groups differed significantly from each other.

- Phase 3: Evaluation of the Informative Strategy (Acceptability)

The acceptability of the strategy was evaluated using a Likert scale instrument with 7 response options, ranging from 1 (Totally disagree) to 7 (Totally agree). Of the 213 participants in the initial phase, 36 students responded to the evaluation. An electronic questionnaire was distributed via email two months after participation in the strategy.

The key results regarding the students’ satisfaction and perception of the strategy are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Description of CMELAC results.

Enjoyment of the Activity: 72.3% (n = 26) of participants from Institución Universitaria Visión de las Américas (IUVA) and 19.5% (n = 7) from BUAP expressed that they agreed or totally agreed that they had enjoyed this informative activity.

Intent to Repeat: 75.1% (n = 27) from IUVA and 19.5% (n = 7) from BUAP agreed or totally agreed that they would repeat this type of activity.

Motivation: 69.5% (n = 25) from IUVA and 19.4% (n = 7) from BUAP expressed that they felt motivated by the informative strategy.

Knowledge Improvement: 66.7% (n = 24) from IUVA and 19.5% (n = 7) from BUAP agreed or totally agreed that their knowledge about the topic improved.

Appropriateness of Format: 72.2% (n = 26) from IUVA n and 19.5% (n = 7) from BUAP agreed or totally agreed that this activity format was appropriate for testing their knowledge of the subject.

Identification of Weaknesses: 66.6% (n = 24) from IUVA and 19.5% (n = 7) from BUAP agreed or totally agreed that the strategy helped them identify their weaknesses in the topic.

Fun/Motivation: 75% (n = 27) from IUVA and 19.5% (n = 7) from BUAP agreed that the interactive elements were fun and motivated them to perform the activity.

Perceived Capability: 77.8% (n = 28) from IUVA and 19.5% (n = 7) from BUAP agreed or totally agreed that they felt capable of carrying out the proposed activities.

Valuable Activities: 72.2% (n = 26) from IUVA and 19.5% (n = 7) from BUAP agreed or totally agreed that the activities seemed enjoyable and valuable to them.

4. Discussion

The implementation of interactive and self-managed educational strategies, such as the one presented in this study, showed a high level of acceptance and participation among students at the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla (BUAP-Mexico) and Institución Universitaria Visión de las Américas (IUVA-Colombia). The participation of 213 students in the first phase indicated an interest in innovative learning methodologies, as evidenced by other studies (García-Viola et al., 2019; Gómez-Urquiza et al., 2019). Implementing interactive, self-managed educational strategies has emerged as a transformative approach to dental education. These strategies allowed us to integrate theory with practice, fostering meaningful and student-centred learning (Pereira et al., 2021).

The participant demographic profile revealed a mean age of 20 years and a gender distribution of 56.1% female and 43.9% male. These characteristics align closely with typical enrollment patterns in Latin American dental programs (Deniz et al., 2024; Rodríguez-Roca et al., 2023). This suggests adequate sample representativeness and supports the potential generalizability of the findings to similar educational contexts across the region.

4.1. Engagement and Ethical Framework

The expectation campaign and use of digital tools, such as QR codes and emails, made it easier to bring participants together and facilitate the informed consent process. This multi-channel approach aligns with best practices in contemporary educational research, integrating technology from the start.

The study successfully recruited 213 students across both institutions, demonstrating strong initial interest in innovative learning methodologies. This high participation rate supports research by Nguyen et al., who found dental students to be increasingly receptive to game-based learning (Nguyen et al., 2023). The exclusion of 15 students (6.5%) demonstrated respect for autonomy and voluntariness, essential in educational research (Solis Sánchez et al., 2023).

4.2. Interactive Strategy Performance and Student Engagement

In the second phase, almost all of the participants (94.8%) interacted with the Genially-based game, indicating a high level of engagement with the digital strategy. The average interaction time was 5′16″ min, suggesting that the activity was brief enough to maintain attention, as recommended in the design of gamified learning (Gini et al., 2025). The optimal interaction duration of about five minutes aligns with the principles of cognitive load theory and attention span research in gamified learning environments (Bassanelli et al., 2024). These findings highlight the feasibility of implementing short, focused interactive activities in oral health education settings.

The game provided immediate feedback and allowed students to reattempt questions, so the responses primarily capture short-term recall and in-game performance rather than stable knowledge acquisition. The distribution of correct and incorrect answers reflects students’ interaction with the content and the usability of the tool, rather than true learning outcomes; a limitation inherent to this type of embedded assessment. As previous studies have shown, interactive quizzes with real-time feedback can increase motivation and engagement, even though they may not accurately measure long-term learning (Aubeux et al., 2020; Choi et al., 2024; Madi et al., 2024).

Overall, the pattern of responses and the high participation rate suggest that the gamified environment was accessible, motivating, and appropriately calibrated in difficulty. These observations are consistent with research indicating that quiz-based interactive tools improve student enjoyment, interactivity, and perceived usefulness compared with traditional formats (Pereira et al., 2021). However, in accordance with the study design, these results should be interpreted strictly as indicators of engagement and acceptability, not as evidence of knowledge improvement.

4.3. Acceptability and Perceived Value

The third phase, which was focused on the evaluation of the strategy’s acceptability, yielded encouraging results. Although the sample size in this phase was small (n = 36), the results showed that 72.2% of IUVA students and 19.4% of BUAP students found the strategy entertaining and useful for expanding their knowledge. This positive perception coincided with the results reported by Schweder and Raufelder (2024), in which it was demonstrated that autonomy, intrinsic motivation, and deep learning are promoted by self-managed and playful environments. Also, this positive reception is in line with research by Teerawongpairoj et al. (2024), in which it was found that student engagement and learning satisfaction in dental education are significantly enhanced by gamified online role-play strategies. The variation in response rates among institutions suggests the presence of potential cultural or contextual factors that warrant further investigation. These factors may impact the interpretation of the results.

This blend of flexibility, interaction, and self-assessment was effective in higher education health settings, where students must develop critical and reflective skills (Mursalzade et al., 2025). The results obtained show that strategies based on gamification and digital learning can strengthen academic commitment. This type of tool is accessible and scalable and facilitates the personalization of learning, which is an essential aspect of new university educational models (du Plooy et al., 2024). This supports research showing that such environments promote critical thinking and reflective competencies, both vital for health science education (Mantzourani et al., 2019).

The findings of the current study corroborate the notion that gamification-based strategies can be advantageous in the context of dental education. It has been demonstrated that interactive platforms are more effective in maintaining student attention and motivation than traditional lecture-based approaches. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that these platforms can promote knowledge gain. The provision of immediate feedback and interactive elements has been demonstrated to facilitate superior information processing and retention. Additionally, the scalability and accessibility of these systems is noteworthy. Digital platforms have the capacity to facilitate consistent delivery across a variety of institutions and student cohorts. Personalized learning opportunities are a key benefit of these platforms. Self-paced interaction allows students to engage according to their schedules and learning preferences. This has been shown to enhance student engagement and effective learning strategies. These align with the evolving landscape of higher education, where personalized learning experiences using technology are recognized as essential to effective pedagogy (Zou et al., 2025).

Integrating theory with gamified practice addresses a key challenge in dental education. These strategies provide immediate feedback and interactive engagement, fostering meaningful student-centered learning that connects conceptual knowledge to clinical practice (To, 2022). However, without baseline measurements or a control group, it is not possible to determine whether observed responses are attributable to the intervention or to pre-existing knowledge or external factors. Consequently, even though non-parametric tests were applied to explore patterns in the post-intervention data, these analyses cannot assess change or establish causality. The results are therefore interpreted strictly in terms of engagement, usability, and acceptability rather than educational effectiveness.

Therefore, effective information strategies regarding the risks of e-cigarette use among dental health students are closely linked to positive behavioral changes and improved long-term knowledge retention. These strategies are most effective when integrated into curricula and personalized interventions (Sarkar et al., 2024; Shabani et al., 2025). Although oral health students lack comprehensive knowledge of the risks that e-cigarettes pose to oral health, they are willing to change their behavior (e.g., quit or reduce use) if the risks are clearly explained and communicated through targeted information strategies (Alhajj et al., 2022a, 2022b; Beard et al., 2025). The health belief model suggests that greater awareness of the risks leads to a lower likelihood of e-cigarette use and less defensiveness about their use among students (Sarkar et al., 2024). Incorporating education about the risks of e-cigarettes into dental and oral health curricula (e.g., seminars, interactive modules, case-based learning) improves both retention and the ability to counsel patients (Shabani et al., 2025). Targeted campaigns that address misconceptions (e.g., that e-cigarettes are ‘safe’ alternatives) are essential for achieving long-lasting change (Hussain et al., 2024).

The present study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the intervention consisted of a very brief gamified activity, and the overall exposure time was short. This limited duration restricts the extent to which meaningful learning, behavioral change, or attitudinal shifts can be inferred. Similar variability in intervention length has been reported in prior studies, where inconsistent adherence to evidence-based guidelines may influence students’ retention and perceived confidence (Alhajj et al., 2022a, 2022b). Second, the sample size in Phase 3 was considerably reduced (n = 36), which limits the generalizability of the perception and acceptability findings. Third, the use of self-administered questionnaires introduces the possibility of self-report bias, including social desirability and recall effects. Additionally, since participation was voluntary, the possibility of self-selection bias must be considered. Students with higher academic motivation or more favorable attitudes toward digital tools may have been overrepresented. Fourth, the study employed a post-measurement–only quasi-experimental design, with no control group and no pre-intervention assessment. This design has inherently lower internal validity and is more susceptible to selection and confounding biases. This avoids causal inference and precluding any conclusion regarding knowledge improvement attributable to the intervention. Finally, the absence of longitudinal follow-up does not allow for the evaluation of long-term retention, sustained engagement, or lasting behavioral effects. Future research should incorporate longitudinal and multicenter designs, include baseline and follow-up assessments, and recruit larger and more diverse samples to more rigorously evaluate the sustained educational impact of gamified strategies in oral health training.

Despite these limitations, the study presents several notable strengths. It offers one of the few documented applications of a gamified, evidence-based digital strategy specifically designed for oral health students in two Latin American contexts, providing cross-institutional insights into student engagement with emerging educational technologies. The use of an interactive platform allowed for high participation rates and real-time behavioral interaction data, which are less commonly captured in traditional educational research. Additionally, the multi-phase structure enabled the examination of both immediate user engagement and delayed perceptions of the strategy’s acceptability. The contribution of empirical data on the feasibility, usability, and perceived usefulness of a scalable, low-cost digital intervention is an important step toward informing curriculum innovation and guiding the integration of interactive tools in oral health education.

5. Conclusions

These findings offer important guidance for oral health education policy. Gamified digital strategies could be incorporated into curricula to improve student engagement and support the development of digital competencies in dental training. Their scalability makes them suitable for broader institutional and national modernization efforts. Future longitudinal and multicenter studies are needed to evaluate long-term learning outcomes and confirm the applicability of these approaches across diverse educational settings, providing stronger evidence for policy adoption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Y.H.S. and I.A.E.D.S.; methodology, B.Y.H.S.; software, B.Y.H.S.; validation, I.A.E.D.S. and J.A.M.; formal analysis, B.Y.H.S.; investigation, J.P.M.O.; writing—original draft preparation, B.Y.H.S. writing—review and editing, I.A.E.D.S.; visualization, J.P.M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the two participating universities. The Research Committee of the Faculty of Stomatology of Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla approved the study with code: 2024277, dated 6 December 2024. And the Research Ethics Committee of Institución Universitaria Visión de las Américas approved the study in accordance with Act 173 on 13 March 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BUAP | Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla |

| IUVA | Institución Universitaria Visión de las Américas |

| CMELAC | Cooperative Playful Learning Strategies |

References

- Alhajj, M. N., Al-Maweri, S. A., Folayan, M. O., Halboub, E., Khader, Y., Omar, R., Amran, A. G., Al-Batayneh, O. B., Celebić, A., Persic, S., Kocaelli, H., Suleyman, F., Alkheraif, A. A., Divakar, D. D., Mufadhal, A. A., Al-Wesabi, M. A., Alhajj, W. A., Aldumaini, M. A., Khan, S., … Ziyad, T. A. (2022a). Knowledge, beliefs, attitude, and practices of e-cigarette use among dental students: A multinational survey. PLoS ONE, 17, e0276191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhajj, M. N., Al-Maweri, S. A., Folayan, M. O., Halboub, E., Khader, Y., Omar, R., Amran, A. G., Al-Batayneh, O. B., Celebić, A., Persic, S., Kocaelli, H., Suleyman, F., Alkheraif, A. A., Divakar, D. D., Mufadhal, A. A., Al-Wesabi, M. A., Alhajj, W. A., Aldumaini, M. A., Khan, S., … Ziyad, T. A. (2022b). Oral health practices and self-reported adverse effects of e-cigarette use among dental students in 11 countries: An online survey. BMC Oral Health, 22(1), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaleh, N., & Alnanih, R. (2020). Gamification-based behavioral change in children with diabetes mellitus. Procedia Computer Science, 170, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzalabani, A. A., & Eltaher, S. M. (2020). Perceptions and reasons of e-cigarette use among medical students: An internet-based survey. Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association, 95(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubeux, D., Blanchflower, N., Bray, E., Clouet, R., Remaud, M., Badran, Z., Prud’homme, T., & Gaudin, A. (2020). Educational gaming for dental students: Design and assessment of a pilot endodontic-themed escape game. European Journal of Dental Education, 24(3), 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandi, P., Asare, S., Majmundar, A., Nargis, N., Jemal, A., & Fedewa, S. A. (2022). Relative harm perceptions of e-cigarettes versus cigarettes, U.S. adults, 2018–2020. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 63(2), 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassanelli, S., Gini, F., Bucchiarone, A., Bonetti, F., Roumelioti, E., & Marconi, A. (2024). Lost in gamification design: A scientometric analysis. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science, International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Washington, DC, USA, 29 June–4 July 2024 (Vol. 14730, pp. 3–21). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, C., Ragbir, A., Rice, T., Thomas, M., & Naidu, R. (2025). E-cigarette use and knowledge of its effect on oral health among health sciences students in Trinidad and Tobago. Frontiers in Oral Health, 6, 1547246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A., Meng Yip, H., & Garg, M. (2023). e-Cigarettes and oral cancer: What do we know so far? British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 61(5), 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canzan, F., Finocchio, E., Moretti, F., Vincenzi, S., Tchepnou-Kouaya, A., Marognolli, O., Poli, A., & Verlato, G. (2019). Knowledge and use of e-cigarettes among nursing students: Results from a cross-sectional survey in north-eastern Italy. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charde, P., Ali, K., & Hamdan, N. (2024). Effects of e-cigarette smoking on periodontal health: A scoping review. PLoS Global Public Health, 4(3), e0002311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C., & Ebrahimi, O. V. (2023). Gamification: A novel approach to mental health promotion. Current Psychiatry Reports, 25(11), 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y., Lee, M., Kim, J., & Park, W. (2024). Clinical observation using virtual reality for dental education on surgical tooth extraction: A comparative study. BMC Medical Education, 24(1), 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong-Silva, D. C., Sant’Anna, M. de F. B. P., Riedi, C. A., Sant’Anna, C. C., Ribeiro, J. D., Vieira, L. M. N., Pinto, L. A., Terse-Ramos, R., Morgan, M. A. P., Godinho, R. N., di Francesco, R. C., da Silva, C. A. M., Urrutia-Pereira, M., Lotufo, J. P. B., Silva, L. R., & Solé, D. (2025). Electronic cigarettes: “wolves in sheep’s clothing”. Jornal de Pediatria, 101(2), 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, R., Campbell, R., Hildon, Z., Hobbs, L., & Michie, S. (2015). Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: A scoping review. Health Psychology Review, 9(3), 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, H. A., Balkan, E. P., İncebeyaz, B., & Kamburoğlu, K. (2024). Effect of gamification applications on success of dentistry students. World Journal of Methodology, 15(1), 97374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plooy, E., Casteleijn, D., & Franzsen, D. (2024). Personalized adaptive learning in higher education: A scoping review of key characteristics and impact on academic performance and engagement. Heliyon, 10(21), e39630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteban-Lopez, M., Perry, M. D., Garbinski, L. D., Manevski, M., Andre, M., Ceyhan, Y., Caobi, A., Paul, P., Lau, L. S., Ramelow, J., Owens, F., Souchak, J., Ales, E., & El-Hage, N. (2022). Health effects and known pathology associated with the use of e-cigarettes. Toxicology Reports, 9, 1357–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadus, M. C., Smith, T. T., & Squeglia, L. M. (2019). The rise of e-cigarettes, pod mod devices, and JUUL among youth: Factors influencing use, health implications, and downstream effects. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 201, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, V., Jaganathan, R., Chinnaiyan, M., Chengizkhan, G., Sadhasivam, B., Manyanga, J., Ramachandran, I., & Queimado, L. (2025). E-Cigarette effects on oral health: A molecular perspective. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 196, 115216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Viola, A., Garrido-Molina, J. M., Márquez-Hernández, V. V., Granados-Gámez, G., Aguilera-Manrique, G., & Gutiérrez-Puertas, L. (2019). The influence of gamification on decision making in nursing students. Journal of Nursing Education, 58(12), 718–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, S. V., Gauthier, A., Ehrstrom, B. L. E., Wortley, D., Lilienthal, A., Car, L. T., Dauwels-Okutsu, S., Nikolaou, C. K., Zary, N., Campbell, J., & Car, J. (2019). Serious gaming and gamification education in health professions: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(3), e12994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gini, F., Bassanelli, S., Bonetti, F., Mogavi, R. H., Bucchiarione, A., & Marconi, A. (2025). The role and scope of gamification in education: A scientometric literature review. Acta Psychologica, 259, 105418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J. Y., Ghosh, M., & Hoet, P. H. (2023). Association between metal exposure from e-cigarette components and toxicity endpoints: A literature review. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 144, 105488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Urquiza, J. L., Gómez-Salgado, J., Albendín-García, L., Correa-Rodríguez, M., González-Jiménez, E., & Cañadas-De la Fuente, G. A. (2019). The impact on nursing students’ opinions and motivation of using a “nursing escape room” as a teaching game: A descriptive study. Nurse Education Today, 72, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halalau, A., Holmes, B., Rogers-Snyr, A., Donisan, T., Nielsen, E., Cerqueira, T. L., & Guyatt, G. (2021). Evidence-based medicine curricula and barriers for physicians in training: A scoping review. International Journal of Medical Education, 12, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R., Yang, J., Li, X., Wang, X., Du, W., Kang, W., Liu, J., Yang, T., Li, J., Wang, X., Liu, J., & Zhao, B. (2025). Decoding different oxidative stress pathways in periodontitis: A comparative review of mechanisms of traditional tobacco smoke and electronic smoke aerosol. Archives of Toxicology, 99(6), 2261–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B., Hew, K. F., & Lo, C. K. (2019). Investigating the effects of gamification-enhanced flipped learning on undergraduate students’ behavioral and cognitive engagement. Interactive Learning Environments, 27(8), 1106–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Q., Alshehri, W., Alyousef, S., Alkhudairy, R., Alotai, L., Alshaywi, A., Alotaibi, R., & Almasma, L. (2024). E-cigarette usage, awareness and harmful effects among dental students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. International Journal Of Community Medicine and Public Health, 12(1), 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, D., Suppan, L., Sanchez, E., Huguenin, A., & Laurent, M. (2021). The co.lab generic framework for collaborative design of serious games: Development study. JMIR Serious Games, 9(3), e28674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenssen, B. P., Walley, S. C., Groner, J. A., Rahmandar, M., Boykan, R., Mih, B., Marbin, J. N., & Caldwell, A. L. (2019). E-cigarettes and similar devices. Pediatrics, 143(2), e20183652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, C., Chahine, J. B., Haykal, T., Al Hageh, C., Rizk, S., & Khnayzer, R. S. (2021). E-cigarette aerosol induced cytotoxicity, DNA damages and late apoptosis in dynamically exposed A549 cells. Chemosphere, 263, 127874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, J., La Rosa, G. R. M., Di Stefano, A., Gangi, D., Sahni, V., Yilmaz, H. G., Fala, V., Górska, R., Ludovichetti, F. S., Amaliya, A., Alghalayini, D., Raganin, M., Chapple, I., Kim, B. I., & Polosa, R. (2025). Navigating the dual burden of dental and periodontal care in individuals who also smoke: An expert review. Journal of Dentistry, 157, 105744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krath, J., Schürmann, L., & von Korflesch, H. F. O. (2021). Revealing the theoretical basis of gamification: A systematic review and analysis of theory in research on gamification, serious games and game-based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 125, 106963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmikantha, H. T. (2024). Leveling up orthodontic education: Game-based learning as the new frontier in orthodontic curriculum. Research and Development in Medical Education, 13, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, R. L., Annetta, L., Firestone, J., & Etopio, E. (2018). A meta-analysis with examination of moderators of student cognition, affect, and learning outcomes while using serious educational games, serious games, and simulations. Computers in Human Behavior, 80, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, G. R. M., Del Giovane, C., Minozzi, S., Kowalski, J., Chapple, I., Amaliya, A., Farsalinos, K., & Polosa, R. (2025). Oral health effects of non-combustible nicotine products: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Dentistry, 160, 105910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M., & Gierer, S. (2022). Electronic cigarettes and vaping in allergic and asthmatic disease. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America, 42(4), 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madi, M., Gaffar, B., Farooqi, F. A., Zakaria, O., Sadaf, S., Alhareky, M., & AlHumaid, J. (2024). Virtual versus traditional learning: A comparison of dental students’ perception and satisfaction. Dentistry Journal, 12(12), 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantzourani, E., Desselle, S., Le, J., Lonie, J. M., & Lucas, C. (2019). The role of reflective practice in healthcare professions: Next steps for pharmacy education and practice. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 15(12), 1476–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzano-León, A., Camacho-Lazarraga, P., Guerrero-Puerta, M. A., Guerrero-Puerta, L., Alias, A., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., & Trigueros, R. (2021). Development and validation of a questionnaire on motivation for cooperative playful learning strategies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, M., He, X., Noël, A., Park, J. A., Crotty Alexander, L., Zelikoff, J., Christiani, D., Hess, J., Shannahan, J., & Wright, C. (2025). Beyond the puff: Health consequences of vaping. Inhalation Toxicology, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mursalzade, G., Escriche-Martínez, S., Valdivia-Salas, S., Jiménez, T., & López-Crespo, G. (2025). Factors associated with psychological flexibility in higher education students: A systematic review. Sustainability, 17, 5557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natto, Z. (2020). Dental students’ knowledge and attitudes about electronic cigarettes: A cross-sectional study at one Saudi university. Journal of Dental Education, 84, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L., Le, C., & Lee, V. D. (2023). Game-based learning in dental education. Journal of Dental Education, 87(4), 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D., & Lloyd, J. E. (2020). Understanding and responding to health literacy as a social determinant of health. Annual Review of Public Health, 42, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawade, D. B., & Aienobe-Asekharen, C. A. (2025). Artificial intelligence in tobacco control: A systematic scoping review of applications, challenges, and ethical implications. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 202, 105987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R. D. A., Matos, S. N., & Lopes, R. P. (2021). DentalGame: Um jogo sério para O ensino de saúde bucal. Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrella, F., Faverio, P., Cara, A., Cassina, E. M., Libretti, L., Torto, S. L., Pirondini, E., Raveglia, F., Spinelli, F., Tuoro, A., Perger, E., & Luppi, F. (2025). Clinical impact of vaping. Toxics, 13(6), 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riker, C. A., Lee, K., Darville, A., & Hahn, E. J. (2012). E-Cigarettes: Promise or peril? Nursing Clinics of North America, 47(1), 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Roca, B., Calatayud, E., Gomez-Soria, I., Marcén-Román, Y., Cuenca-Zaldivar, J. N., Andrade-Gómez, E., & Subirón-Valera, A. B. (2023). Assessing health science students’ gaming experience: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1258791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M. S., Hamad, A. S., Alasmari, M. A. N., Alamri, A. A., Alamri, H. M. S., Alhamoud, S. M., & Alqahtani, A. M. F. (2023). The impact of e-cigarettes on oral and dental health: Narrative review. Saudi Journal of Medical and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 9(12), 863–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A., Vinayachandran, D., C, G., M, S., Siluvai, S., Gurram, P., C, L., S, M., V, K., & K., R. (2024). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of university students regarding the impact of smokeless tobacco, areca nut, e-cigarette use on oral health. Cureus, 16, e66828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweder, S., & Raufelder, D. (2024). Why does a self-learning environment matter? Motivational support of teachers and peers, enjoyment and learning strategies. Learning and Motivation, 88, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, D., Dula, L., Dalipi, Z., Krasniqi, M., & Meto, A. (2025). Knowledge and perceptions of dentists regarding e-cigarettes: Implications for oral health and public awareness and education. Dentistry Journal, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugam, G. (2024). Understanding the oral health risks of vaping: Implications for oral cancer and periodontal disease. Oral Oncology Reports, 10, 100486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., Windle, S. B., Filion, K. B., Thombs, B. D., O’Loughlin, J. L., Grad, R., & Eisenberg, M. J. (2020). E-cigarettes and youth: Patterns of use, potential harms, and recommendations. Preventive Medicine, 133, 106009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis Sánchez, G., Alcalde Bezhold, G., & Alfonso Farnós, I. (2023). Research ethics: From principles to practical aspects. Anales de Pediatria, 99(3), 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundy, A., Koulouvari, C., Sakellari, A., Barbouni, E., Koulouvari, A.-D., Margariti, A., Sakellari, E., Barbouni, A., & Lagiou, A. (2025). Applications of behavioral change theories and models in health promotion interventions: A rapid review. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K., Levin-Zamir, D., Duong, T. V., Okan, O., Brasil, V. V., & Nutbeam, D. (2021). Building health literacy system capacity: A framework for health literate systems. Health Promotion International, 36, I13–I23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormacq, C., Wosinski, J., Boillat, E., & Den Broucke, S. V. (2020). Effects of health literacy interventions on health-related out-comes in socioeconomically disadvantaged adults living in the community: A systematic review. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(7), 1389–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S., Yu, H., Ling, J., Yao, D., Chen, H., & Liu, G. (2023). The influence of health literacy and knowledge about smoking hazards on the intention to quit smoking and its intensity: An empirical study based on the data of China’s health literacy investigation. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taj, F., Klein, M. C. A., & Van Halteren, A. (2019). Digital health behavior change technology: Bibliometric and scoping review of two decades of research. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 7(12), e13311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teerawongpairoj, C., Tantipoj, C., & Sipiyaruk, K. (2024). The design and evaluation of gamified online role-play as a telehealth training strategy in dental education: An explanatory sequential mixed-methods study. Scientific Reports, 14, 8425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P. J., Silva, M. N., Mata, J., Palmeira, A. L., & Markland, D. (2012). Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanki, G., Bansal, A., Shah, K., & Sheladia, V. (2024). Knowledge, attitude and practices of e-cigarettes and vaping among undergraduate dental students of Ahmedabad City, Gujarat: A cross sectional survey. International Journal of Scientific Research, 13(11), 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theng, Y. L., Lee, J. W. Y., Patinadan, P. V., & Foo, S. S. B. (2015). The use of videogames, gamification, and virtual environments in the self-management of diabetes: A systematic review of evidence. Games for Health Journal, 4(5), 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiem, D. G. E., Donkiewicz, P., Rejaey, R., Wiesmann-Imilowski, N., Deschner, J., Al-Nawas, B., & Kämmerer, P. W. (2023). The impact of electronic and conventional cigarettes on periodontal health—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Oral Investigations, 27(9), 4911–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D. S., Thompson, A. P., & McConnell, K. (2020). Nursing students’ engagement and experiences with virtual reality in an undergraduate bioscience course. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 17(1), 20190081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timpel, P., Cesena, F. H. Y., da Silva Costa, C., Soldatelli, M. D., Gois, E., Castrillon, E., Díaz, L. J. J., Repetto, G. M., Hagos, F., Castillo Yermenos, R. E., Pacheco-Barrios, K., Musallam, W., Braid, Z., Khidir, N., Romo Guardado, M., & Roepke, R. M. L. (2018). Efficacy of gamification-based smartphone application for weight loss in overweight and obese adolescents: Study protocol for a phase II randomized controlled trial. Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology and Metabolism, 9(6), 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, J. (2022). Using learner-centred feedback design to promote students’ engagement with feedback. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(4), 1309–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolks, D., Lampert, C., Dadaczynski, K., Maslon, E., Paulus, P., & Sailer, M. (2020). Game-based approaches to prevention and health promotion: Serious games and gamification. Bundesgesundheitsblatt—Gesundheitsforschung—Gesundheitsschutz, 63(6), 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, M., Amin, S. U., Munsif, M., Safaev, U., Khan, H., Khan, S., & Ullah, H. (2022). Serious games in science education. A Systematic Literature Review. Virtual Reality and Intelligent Hardware, 4(3), 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. J., Bhadriraju, S., & Glantz, S. A. (2021). E-cigarette use and adult cigarette smoking cessation: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 111(2), 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasfi, R. A., Bang, F., de Groh, M., Champagne, A., Han, A., Lang, J. J., McFaull, S. R., Melvin, A., Pipe, A. L., Saxena, S., Thompson, W., Warner, E., & Prince, S. A. (2022). Chronic health effects associated with electronic cigarette use: A systematic review. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 959622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiener, R. C. (2023). Cross sectional observational study of current e-cigarette use and oral health needs among adolescents, population assessment of tobacco and health study, wave 5. Hygiene, 3(4), 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-H., Du, J.-K., & Lee, C.-Y. (2021). Development and questionnaire-based evaluation of virtual dental clinic: A serious game for training dental students. Medical Education Online, 26(1), 1983927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M., Luo, Y., Zhang, Y., Xia, R., Qian, H., & Zou, X. (2023). Game-based learning in medical education. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1113682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., & Wen, C. (2023). The risk profile of electronic nicotine delivery systems, compared to traditional cigarettes, on oral disease: A review. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1146949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y., Kuek, F., Feng, W., & Cheng, X. (2025). Digital learning in the 21st century: Trends, challenges, and innovations in technology integration. Frontiers in Education, 10, 1562391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.