Centering Student Voices in Restorative Practices Implementation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Restorative Practices in Schools: A Global View

2.2. Punishment Practices in Schools

2.3. Zero Tolerance Policies

2.4. Racially Disproportionate Punishment

2.5. School-to-Prison Pipeline

2.6. Restorative Discipline in Schools

2.6.1. Repairing Harm

2.6.2. Building Community

2.6.3. Relationships

2.6.4. Current Research

3. Purposes and Significance of Study

4. Conceptual Framework

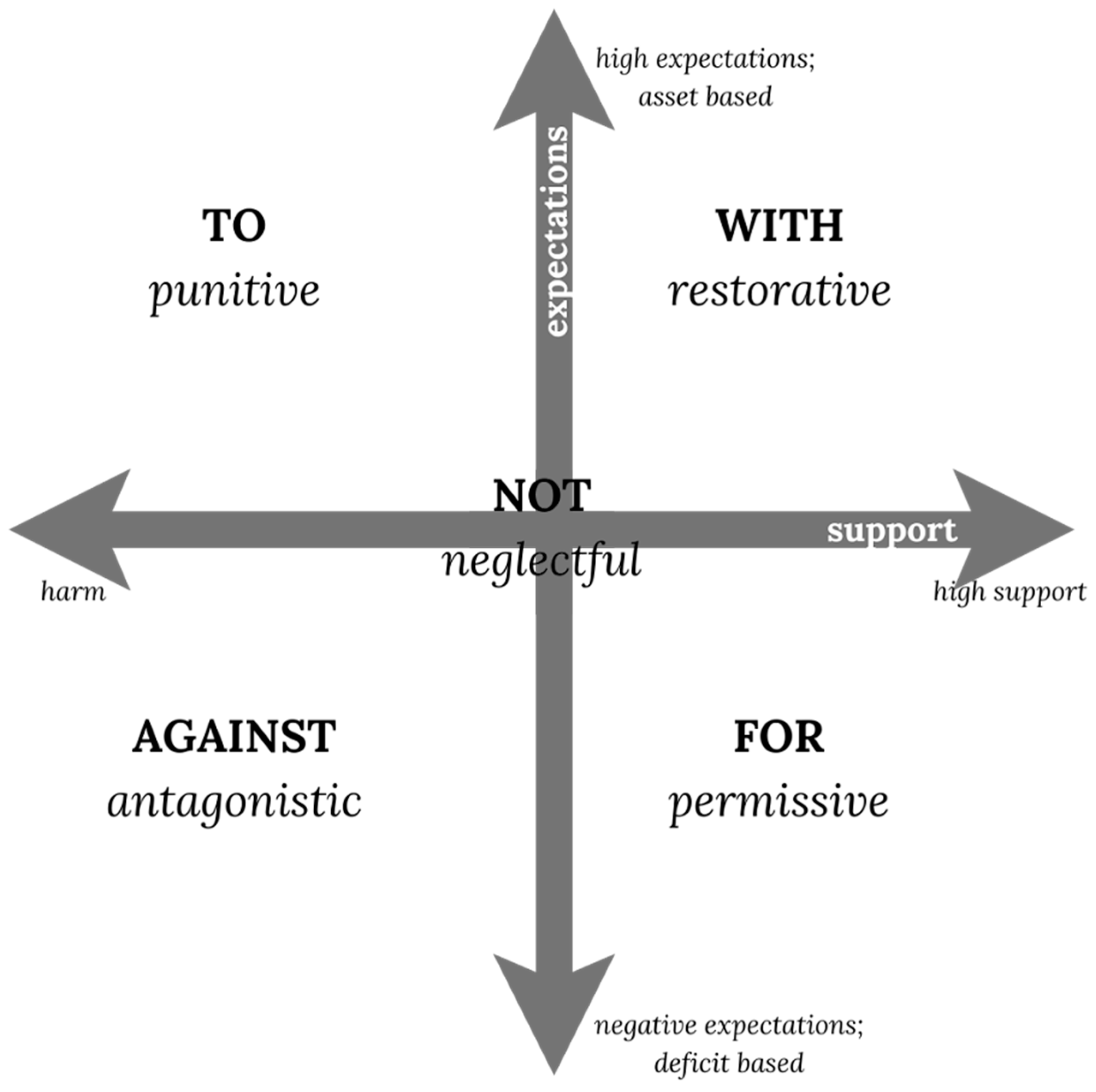

4.1. Emergence of the Social Discipline Window

4.2. Affordances and Limitations of the Social Discipline Window

5. Positionality

6. Methodology

6.1. Research Question

6.2. Research Experience

6.3. Participants

6.3.1. Sampling

6.3.2. Participant Demographics

6.4. Data Sources

6.5. Data Analysis

6.5.1. Phase One

6.5.2. Phase Two

7. Findings: Alumni Describe Relationships with Adults as RHS

7.1. “To” Experiences: Alumni Stories of Punitive Disciplinary Incidents at RHS

Oli: The principal got me. He said “yeah, I’m gonna suspend you for two days. This and that. You can’t be doing this.” Did they try to do the finger swab thing for the? No, they didn’t even… they didn’t even do that to me. They didn’t even do that to me. They did not do the finger swab did not check me, they did not do anything. Literally. They just sent me home. They didn’t even try to… like to figure out what was the cause. I just smelled like it and I had to go home. That was a… they didn’t try to take me and search me… they didn’t bring no dogs. I would be fine if they brought the dog because I didn’t have anything on me. I did not touch the blood at all. So my fingers were straight. My eyes were clear as day like I was perfectly fine. I just smelled like it: “no, go home for three days.” I went home for three days.

Oli: Okay, so whenever I say that they did something to the kids, it would be that, that weed scenario that I smell like shade dank, and, you know, he just, like, sent me off.

7.2. “Not” Experiences: Alumni Stories of Neglectful Disciplinary Responses at RHS

7.3. “For” Experiences: Alumni Stories of Relational Practices at RHS

Francisca: And, you know, being class president, I was trying to do all these things for my class and allow my class to have fun and let their voice be heard. But at the same time, you know, working with the principal at the time… well, he’s still the same one… I just felt like a lot of the time, I didn’t have the freedom to make decisions: I would come up with proposals and they just be like, “no,” or they’d be like, “Oh, we can look into it.” Yes, you know, it was a lot of the times when the admin had a lot of control and made decisions for students that I felt like, you should allow your students to make them and those are things you know, kind of like events that we were coordinating our pep rallies or you know, little things, fundraisers here and there that we wanted to do, or International Day, you know, like all these things that Riverdale is known for, I felt like a lot of the times, they were student-led, but a lot of the decisions that were made on the backside of it were from admin and teachers.

And, you know, I have such a great relationship with Mrs. Bud because she kind of inspired and allowed her students involved in SGA and International Day to be led by students and [she] gave us that feeling of this is yours, you handle it, you control it, you do it yourself.

And that’s why I think that International Day was such a big thing at Riverdale because students felt like that was their time to shine, as opposed to, you know, any other time where students kind of felt neglected or unheard or ignored. Because they didn’t feel like those things were happening for them, or they didn’t have authority over it.

7.4. “With” Experiences: Alumni Stories of Restorative Discipline and Restorative Relationships at RHS

Francisca: And then once we introduce the Restorative team, it kind of gave students the opportunity to where if they had some kind of disagreement with a teacher or an encounter with a student that, you know, they had, that would usually be taken care of by admin, that was kind of the moment where we were able to jump in and try the different restorative practice techniques. But I think that with my time at Riverdale there was a lot of, of change my senior year, but in the time, like, my ninth and 11th, grade year, there was still a lot of just, you didn’t feel like you were in control.

And, you know, hopefully, this has changed with the Restorative team being a part of it, and students kind of being becoming leaders and taking over their school. Because at the end of the day, it’s their school.

And with today’s world and so many things happening, there’s just you know, Black Lives Matter movement, you know, you want your LGBTQ community to feel safe and you want immigrants to feel safe and you know, with Riverdale being the diverse school that they are, I think that you want your community that you are serving to feel comfortable in your building. You want them to feel heard, and you want them to feel equally treated by every single person. And I think that, you know, like I said, I haven’t gone to one class, I don’t know if this has changed. But at the time that I was there, I think that we were on the road to making these changes to where students felt heard and felt like, they could be a part of a lot of the changes in school.

As a member of the inaugural Restorative Student Leaders team (which began the same year RHS began implementing RP with just Freshman teachers and students), Francisca described the change she felt at RHS as a result of RP implementation and her experience on the RSL team. She saw subtle shifts where the RSL team would try “different restorative practice techniques” to solve disagreements that “would usually be taken care of by admin[istration].” Francisca saw RHS as being “on the road to making these changes to where students felt heard and felt like, they could be a part of a lot of the changes in school.” Francisca saw the beginnings of “With” experiences at RHS and hoped future students would feel “comfortable,” “heard,” and a “part of changes in the school.”

Oli: But with the kids, Restorative team! Come on now. The Restorative team! Now that was crazy now that I felt like I was somebody. I felt like, bro, I felt like I was the queen of the world, the king of the world, like I really felt like I could really do anything. And that was cool. That was cool. I will forever hold on to that precious memory. Because you know that, that, to this day… it’s been like two years I’ve been out of there, and dude, that is still implemented in my brain so hard that I can talk to anybody, anybody! And not feel like I’m being a burden. You know… it just feels great. Now that’s with-what’s with the kids. Feels delicious. Talking to senators, talking to the Board of Education, you know having things really like dramatically change where you see it, you feel it, you know, that’s cool. With the kids is nice.

7.5. From “To” to “With”: A Relationship That Transformed from Punitive to Restorative

Irene: To me. I definitely feel like to me because it wasn’t with me: because she wasn’t trying to work with me to figure out the problem. It wasn’t for me, because she wasn’t like, “Hey, you know, you should change your shirt, because this is showing and you know, I want you to be safe” or whatever; it was to me because she was talking to me, not listening to me and just trying to get me to conform to everybody else. And that’s not me. Like I’m, I don’t conform, I’m different. […]

But the second incident with the circle, I definitely felt like I was being worked with because they were trying for their own views. And we were trying for our own views. But we were working together to figure out what we could do and how we could do it and why we could do it. And everything else, all the other Ws. And that wasn’t for me that definitely was a with moment because they were listening to us and we were listening to them and were trying our best to figure out the middle line.

7.6. Stories That Did Not Fit onto the Social Discipline Window

8. Discussion

8.1. Transitions from Punitive to Restorative Relationships

8.2. Unaddressed Gaps: Alumni Stories That the SDW Did Not Represent

9. Limitations, Implications, and Conclusions

9.1. Implications for School Policies

9.2. Implications for Teachers and Administrators

9.3. Implications for Researchers

9.4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDW | Social Discipline Window |

| RP | Restorative Practices |

| RHS | Riverdale High School |

| 1 | In this paper, I use “student” and “alumni student” interchangeably to acknowledge that participants reflected on their experiences as RHS students while also noting that, at the time of data collection, they were alumni of RHS for between one and six years. |

| 2 | Pseudonym. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | (School demographics have been rounded to the nearest multiple of 5 to prevent reverse lookup of experiences). |

References

- Acosta, J. D., Chinman, M., Ebener, P., Phillips, A., Xenakis, L., & Malone, P. S. (2016). A cluster-randomized trial of restorative practices: An illustration to spur high-quality research and evaluation. Journal of Educational & Psychological Consultation, 26(4), 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force. (2006). Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools? An evidentiary review and recommendations. American Psychological Association. Available online: https://www.apa.org/pubs/info/reports/zero-tolerance.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Anderson, K. P., & Ritter, G. W. (2017). Disparate use of exclusionary discipline: Evidence on inequities in school discipline from a U.S. state. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 25, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S., & Furey, D. (2020). Evaluating restorative justice programs in U.S. high schools: Outcomes and lessons learned. Journal of School Health, 90(7), 507–515. [Google Scholar]

- Arcia, E. (2006). Achievement and enrollment status of suspended students: Outcomes in a large, multicultural school district. Education and Urban Society, 38(3), 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, J. (1989). Crime, shame and re-integration. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn, S. (2020). “The child is not broken”: Leadership and restorative justice at an urban charter high school. Teachers College Record, 122(8), 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, T., Vigil, P., & Garcia, E. (2014). A story legitimating the voices of Latino/Hispanic students and their parents: Creating a restorative justice response to wrongdoing and conflict in schools. Equity & Excellence in Education, 47(4), 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, S., & Ho, E. (2024). No matter how you slice it, Black students are punished more: The persistence and pervasiveness of discipline disparities. AERA Open, 10(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, M., Penner, A. M., & Penner, E. K. (2021). Restorative for all? Racial disproportionality and school discipline under restorative justice. American Educational Research Journal, 59(4), 687–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eagle, H. (2001). Restorative justice in native cultures. State of Justice 3. A periodic publication of Friends Committee on Restorative Justice. Available online: https://restorativejustice.org/rj-archive/restorative-justice-in-native-cultures/ (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Erlandson, D., Harris, E., Skipper, B., & Allen, S. (1993). Doing naturalistic inquiry. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Fabelo, T., Thompson, M. D., Murrin, M., & Combs, M. (2011). Breaking schools’ rules: A statewide study of how school discipline relates to students’ success and juvenile justice involvement. Council of State Governments Justice Center. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, M., & Ruglis, J. (2009). Circuits and consequences of dispossession: The racialized realignment of the public sphere for U.S. youth. Transforming Anthropology, 17(1), 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, B. R., Kervick, C. T., Moore, M., & Turner, T. Á. (2022). School staff and youth perspectives of tier-1 restorative practices classroom circles. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 38(1), 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Given, L. (2008). The sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, D. (1964). The effectiveness of a prison and parole system. Bobbs-Merrill. [Google Scholar]

- Goldys, P. H. (2016). Restorative practices: From candy and punishment to celebrations and problem-solving circles. Journal of Character Education, 12(1), 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, A., & Evans, K. (2020). The starts and stumbles of restorative justice in education: Where do we go from here? National Education Policy Center. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, A., Huang, F. L., & Ward-Seidel, A. R. (2021). Evaluation of the whole school restorative practices project: One-year implementation and impact on discipline incidents. Technical report. Rutgers University. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED614590.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Gregory, A., & Kuan, L. (2015). Restorative justice in U.S. schools: An overview of research and policy. Journal of School Violence, 14(3), 281–301. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, A., Skiba, R. J., & Noguera, P. A. (2010). The achievement gap and the discipline gap: Two sides of the same coin? Educational Researcher, 39(1), 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G., Namey, E., & Mitchell, M. (2013). Collecting qualitative data: A manual for applied research. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Halman, L., Howell, C., Rossier, E., & Verley, J. (2022). Transforming school culture through restorative practices. Dispute Resolution Magazine, 28(3), 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hines-Datiri, D., & Carter Andrews, D. J. (2020). The effects of zero tolerance policies on Black girls: Using critical race feminism and figured worlds to examine school discipline. Urban Education, 55(10), 1419–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafka, J. (2011). The history of “zero tolerance” in American public schooling. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang-Brown, J., Trone, J., Fratello, J., & Daftary-Kapur, T. (2013). A generation later: What we’ve learned about zero tolerance in schools. United States of America, Vera Institute of Justice, Center on Youth Justice. Available online: https://www.vera.org/publications/a-generation-later-what-weve-learned-about-zero-tolerance-in-schools (accessed on 28 April 2016).

- Kim, C. Y., Losen, D. J., & Hewitt, D. T. (2010). The school-to-prison pipeline: Structuring legal reform. New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kupchik, A., & Henry, F. A. (2022). Generations of criminalization: Resistance to desegregation and school punishment. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 60(1), 43–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2015). InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, B. (2008). The power of community. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 17(3), 27–29. Available online: https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/scholarly-journals/power-community/docview/61807191/se-2?accountid=14816 (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Lash, W. L. (2019). Factors that influence the implementation of restorative practices in an urban district: The role of forgiveness and endorsement [Ph.D. dissertation, Cleveland State University]. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lodi, E., Perrella, L., Lepri, G. L., Scarpa, M. L., & Patrizi, P. (2021). Use of restorative justice and restorative practices at school: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losen, D. J., & Martinez, P. (2020). Lost opportunities: How disparate school discipline continues to drive differences in the opportunity to learn (Executive Summary). Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles, UCLA. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED608537.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Lustick, H. (2017). Restorative small schools in locked-down buildings: The impact of zero-tolerance district-wide discipline on small school culture AERA online paper repository, available from: American Educational Research Association. 1430 K Street NW Suite 1200, Washington, DC 20005. Available online: https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/speeches-presentations/restorative-small-schools-locked-down-buildings/docview/2459003748/se-2?accountid=14816 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Lustick, H. (2021). “Restorative justice” or restoring order? Restorative school discipline practices in urban public schools. Urban Education, 56(8), 1269–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluskey, G. (2010). Restoring the possibility of change? A restorative approach with troubled and troublesome young people. International Journal on School Disaffection, 7(1), 19–25. Available online: https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/scholarly-journals/restoring-possibility-change-restorative-approach/docview/1031155067/se-2?accountid=14816 (accessed on 3 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- McCluskey, G., Lloyd, G., Kane, J., Riddell, S., Stead, J., & Weedon, E. (2008). Can restorative practices in schools make a difference? Educational Review, 60(4), 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCold, P., & Wachtel, T. (2003). In pursuit of paradigm: A theory of restorative justice. International Institute of Restorative Practices. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, H. R. (2007). Race, culture, and researcher positionality: Working through dangers seen, unseen, and unforeseen. Educational Researcher, 36(7), 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, H. R. (2012). But what is urban education? Urban Education, 47(3), 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, H. R. (2020a). Fifteenth annual AERA brown lecture in education research: Disrupting punitive practices and policies: Rac(e)ing back to teaching, teacher preparation, and brown. Educational Researcher, 49(3), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, H. R. (2020b). Start where you are, but don’t stay there: Understanding diversity, opportunity gaps, and teaching in today’s classrooms (2nd ed.). Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, H. R., Cunningham, H. B., Delale-O’Connor, L., & Kestenberg, E. G. (2019). These kids are out of control: Why we must reimagine “classroom management” for equity. Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, H. R., Singer, J. N., Parks, L., Murray, I., & Lane-Bonds, D. (2024). Positionality as a data point in race research. Qualitative Inquiry, 31, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsky, L. (2007). SaferSanerSchools: Transforming school cultures with restorative practices. Reclaiming Children and Youth: The Journal of Strength-Based Interventions, 16(2), 5–12. Available online: https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/scholarly-journals/safersanerschools-transforming-school-cultures/docview/62063464/se-2?accountid=14816 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Mirsky, L. (2011). Restorative practices: Giving everyone a voice to create safer saner school communities. Prevention Researcher, 18(5), 3–6. Available online: https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/scholarly-journals/restorative-practices-giving-everyone-voice/docview/1011399685/se-2?accountid=14816 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Morrison, B., & Vaandering, D. (2012). Restorative justice: Pedagogy, praxis, and discipline. Journal of School Violence, 11(2), 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, B. E. (2007). Schools and restorative justice. In G. Johnstone, & D. W. Van Ness (Eds.), Handbook of restorative justice (pp. 325–350). Willan Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz, J. O. (2021). Exclusionary discipline policies, school-police partnerships, surveillance technologies and disproportionality: A review of the school-to-prison pipeline literature. The Urban Review, 53(5), 735–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2021). Racial/ethnic enrollment in public schools: 2017–18 (Indicator CGE-1). In The condition of education 2021. U.S. Department of Education. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/pdf/2021/cge_508c.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Noguera, P. (2003). Schools, prisons, and social implications of punishment: Rethinking disciplinary practices. Theory into Practice, 42, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osher, D., Plank, S., Hester, C., & Houghton, S. (2023). The contribution of school and classroom disciplinary practices to the school-to-prison pipeline. In D. L. Espelage, & E. J. Sabornie (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management (3rd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 288–318). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rainbolt, S., Fowler, E. S., & Mansfield, K. C. (2019). High school teachers’ perceptions of restorative discipline practices. NASSP Bulletin, 103(2), 158–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, K. E. (2019). Relationships of control and relationships of engagement: How educator intentions intersect with student experiences of restorative justice. Journal of Peace Education, 16(1), 49–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldo, R., & Guhin, J. (2022). How and why interviews work: Ethnographic interviews and meso-level public culture. Sociological Methods & Research, 51(1), 34–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, A. (2014). Talking circles for adolescent girls in an urban high school: A restorative practices program for building friendships and developing emotional literacy skills. SAGE Open, 4(4), 1–13. Available online: https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/scholarly-journals/talking-circles-adolescent-girls-urban-high/docview/2488229797/se-2?accountid=14816 (accessed on 3 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- Short, R., Case, G., & McKenzie, K. (2018). The long-term impact of a whole school approach of restorative practice: The views of secondary school teachers. Pastoral Care in Education, 36(4), 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiba, R. J., Horner, R. H., Chung, C.-G., Rausch, M. K., May, S. L., & Tobin, T. (2011). Race is not neutral: A national investigation of African American and Latino disproportionality in school discipline. School Psychology Review, 40(1), 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiba, R. J., & Knesting, K. (2014). Zero tolerance, zero evidence: An analysis of school disciplinary practice. New Directions for Youth Development, 2001(92), 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiba, R. J., & Losen, D. J. (2016). From reaction to prevention: Turning the page on school discipline. American Educator, 39(4), 4. [Google Scholar]

- Standing, V., Fearon, C., & Dee, T. (2012). Investigating the value of restorative practice: An action research study of one boy in a mixed secondary school. International Journal of Educational Management, 26(4), 354–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Stutzman, L., & Mullet, J. (2014). The little book of restorative discipline for schools. Good Books. [Google Scholar]

- Vaandering, D. D. (2013). Student, teacher, and administrator perspectives on harm: Implications for implementing safe and caring school initiatives. Review of Education, Pedagogy & Cultural Studies, 35(4), 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachtel, T. (2005, November 9–11). The next step: Developing restorative communities. Seventh International Conference on Conferencing, Circles and Other Restorative Practices, Manchester, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Wachtel, T. (2013a). Defining restorative. International Institute for Restorative Practices. [Google Scholar]

- Wachtel, T. (2013b). Dreaming of a new reality: How restorative practices reduce crime and violence, improve relationships and strengthen civil society. The Piper’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wald, J., & Losen, D. J. (2003). Defining and redirecting a school-to-prison pipeline. New Directions for Youth Development, 2003(99), 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, E., Bevilacqua, L., Opondo, C., Allen, E., Mathiot, A., West, G., & Bonell, C. (2019). Action groups as a participative strategy for leading whole-school health promotion: Results on implementation from the INCLUSIVE trial in English secondary schools. British Educational Research Journal, 45(5), 979–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, J. L., & Swank, J. M. (2020). A case study of the implementation of restorative justice in a middle school. RMLE Online: Research in Middle Level Education, 43(4), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilf, R. (2012, March 13). Disparities in school discipline move students of color toward prison: New data show youth of color disproportionately suspended and expelled from school (Issue brief). Center for American Progress. Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/news/2012/03/13/11350/disparities-in-school-discipline-move-students-of-color-toward-prison/ (accessed on 28 April 2016).

- Winn, M. T. (2011). Girl time: Literacy, justice, and the school-to-prison pipeline. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Winn, M. T. (2018). Justice on both sides: Transforming education through restorative justice. Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zehr, H. (2002). The little book of restorative justice. Good Books. [Google Scholar]

| Pseudonym (Student-Chosen) | Years Attended RHS | Racial Identity | Gender Identity | Other Identifiers | Participation in Restorative Student Leaders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alethea | 2014–2016 | Hispanic, Asian | Female | Yes | |

| Marley | 2016–2018 | Latina | Female | Yes | |

| Louie | 2013–2017 | Latino | Male | EL (English Language Learner) student First-generation college student | No |

| Oli | 2015–2018 | Hispanic | Female | Yes | |

| Consuelo | 2011–2015 | Black | Male | No | |

| Jake | 2014–2018 | Did not identify | Male | No | |

| Lilly | 2013–2017 | Cambodian | Female | Yes | |

| Francisca | 2013–2017 | Latina | Female | Yes | |

| Irene | 2013–2017 | Asian | Female | Green eyes | Yes |

| Veronica | 2014–2018 | Biracial | Female | No | |

| Kevin | 2013–2017 | Black | Male | Yes | |

| Eustace | 2014–2018 | Latino | Male | No | |

| Ase | 2016–2020 | Kurdish | Female | First-generation college student | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Parks, L.F. Centering Student Voices in Restorative Practices Implementation. Youth 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth6010003

Parks LF. Centering Student Voices in Restorative Practices Implementation. Youth. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleParks, Laura F. 2026. "Centering Student Voices in Restorative Practices Implementation" Youth 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth6010003

APA StyleParks, L. F. (2026). Centering Student Voices in Restorative Practices Implementation. Youth, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth6010003